The Fruits of Philosophy (1832), by Charles Knowlton

by Caroline Meek, Claudia Nunez-Eddy

The Embryo Project Encyclopedia

Published: 2017-10-05

In 1832, Charles Knowlton published The Fruits of Philosophy, a pamphlet advocating for controlling reproduction and detailing methods for preventing pregnancy. Originally published anonymously in Massachusetts, The Fruits of Philosophy was an illegal book because United States law prohibited the publishing of immoral and obscene material, which included information about contraception. In The Fruits of Philosophy, Knowlton detailed recipes for contraceptives and advocated for controlling reproduction. In 1877 in Europe, social activists Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant republished the pamphlet in London, England. At that time, many governments, including the United Kingdom, still considered the book illegal material due to its discussion of contraception. The Fruits of Philosophy was one of the first publications detailing contraceptive methods for controlling reproduction and activists used it in some of the first attempts at repealing obscenity laws in the United States and Great Britain. Through their efforts, Knowlton and those who later republished the pamphlet increased knowledge of reproduction and awareness of methods of contraception. By challenging anti-obscenity laws, the author and activists also helped with the eventual weakening and dissolution of such law.

Knowlton, a physician practicing in the United States, originally wrote The Fruits of Philosophy, also titled The Private Companion of Young Married People and A Treatise on the Population Question. Knowlton studied medicine at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire in the 1820s. Following completion of his medical degree Knowlton moved to Ashfield, Massachusetts, where he practiced medicine and wrote the pamphlet. According to his autobiography, Knowlton wrote the short pamphlet-style guide to inform his patients about contraception and sex education. In 1932, Knowlton anonymously printed several copies of The Fruits of Philosophy and circulated them among his patients. That same year, Abner Kneeland, a theologian and social radical, republished The Fruits of Philosophy in Boston, Massachusetts with Knowlton’s name as the author on the cover, largely increasing circulation of the pamphlet. The government then charged Knowlton under the United States obscenity laws, which classified discussion of contraception as obscene. Knowlton was fined and imprisoned for three months in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Following his release, The Fruits of Philosophy was published again and Mason Grosvenor, a minister in Ashfield, found the pamphlet and took legal action to prevent the circulation of the material. Knowlton was tried again on obscenity charges, but the charges were later dropped. The trials increased the book’s publicity and more than one million copies were sold in America.

Following Knowlton’s death in 1850, circulation of The Fruits of Philosophy continued worldwide. In the 1850s, freethought activist James Watson published The Fruits of Philosophy in London, England. For many years, the pamphlet was published and sold throughout London unchallenged. In the 1870s, following the arrest of several publishers associated with publishing obscene materials, social activists Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant republished The Fruits of Philosophy, to test the validity of the pamphlet under England’s obscenity laws. Knowlton’s original work, The Fruits of Philosophy, has been republished many times throughout the world, however, the most commonly available edition is that published by Bradlaugh and Besant. In their “Publishers’ Preface,” Bradlaugh and Besant state that there are very few changes made to Knowlton’s original pamphlet and that all changes are clearly marked as deviations from the original. In the “Publisher’s Preface,” Bradlaugh and Besant also detail the history of the publication and the need for controlling reproduction in the wake of fears surrounding overpopulation and poverty.

Knowlton’s pamphlet, The Fruits of Philosophy, begins with a section titled “Philosophical Proem,” in which Knowlton discusses the basis and links between consciousness, sensations, passions, and human nature. He argues that humans have the power to prevent any evils that may arise from gratifying sexual desires, such as unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. He argues that it is unreasonable to solely advocate for abstinence to prevent pregnancy because humans are not likely to easily limit sexual gratification. Knowlton states that it is the duty of physicians to inform their patients of these prevention methods. Following that brief introduction, the pamphlet is organized into four chapters. In chapter one, Knowlton argues that controlling reproduction, the idea of conceiving children intentionally instead of accidentally, can be done without challenging any reproductive instincts. He defines reproductive instincts as the urge people have to have sex and reproduce. In chapter two, Knowlton asserts that every person has the right to information on reproduction and pregnancy prevention. He argues that the average person knows too little about the physiology of conception and reproduction. To educate his patients, Knowlton includes detailed descriptions of the reproductive organs and the physiological method of conception. In chapter three, he discusses several methods of contraception including recipes for chemical vaginal washes. Finally, in chapter four, Knowlton discusses why people have sex and argues that reproductive health includes sexual education, which was not common at the time.

In chapter one, Knowlton first discusses the political aspects of reproduction. He starts by referencing Thomas Malthus’ theory on overpopulation and poverty. Malthus, an economist, observed that population growth was exponential, and that as populations increased the lower class suffered in poverty, famine, and disease. Malthus argued that the only way a society could escape this increasing poverty was to restrict population growth. Knowlton explains the Malthusian idea, and states that war, disease, and famine keep populations in check and prevent overpopulation. He questions whether there can be other means to prevent overpopulation. Malthus argued in his work that the only way to combat population growth was through late marriage and celibacy. However, Knowlton explains that the belief that men and women will remain celibate is foolish. Knowlton argues that promoting celibacy and late marriage would actually increase prostitution, and be destructive to physical and mental health.

Knowlton then addresses the social aspects of reproduction, categorizing individuals as either married or not. He asserts that married couples often have many more children than they desire. Knowlton specifically addresses the health and wellbeing of the woman, stating that often a woman’s health, comfort, happiness, and life are endangered by multiple pregnancies. He also argues that married couples who should not become parents reproduce, specifically citing those with hereditary diseases. Knowlton then addresses the social aspect of population control among unmarried youth. He asserts that young men often oppose early marriage, desiring first to make enough money to support a family. However, he argues that young men are unlikely to resist the temptation of sexual gratification and will instead resort to prostitution. To prevent sexual temptation outside of marriage, Knowlton states individuals should marry young and be provided with the knowledge and means to prevent having children early in marriage. Knowlton uses the first chapter to comment on the importance of having the knowledge and means to prevent pregnancy to live the happiest life.

In chapter two, Knowlton states his belief that all individuals have a human right to receive the knowledge of the facts and discoveries made by science, including those of reproduction. He argues that knowledge about reproduction is important because reproduction is very connected to the happiness of humankind, yet he acknowledges that public discussion and investigation of topics like sex are considered improper. He goes on to discuss how the average person’s understanding of conception is lacking, and he states that that lack motivated him to write The Fruits of Philosophy.

As chapter two continues, Knowlton provides detailed descriptions of the external and internal reproductive organs in both males and females. He uses both layman’s terms and medical terminology in his explanations of anatomy, as he designed the pamphlet to give practical information about reproduction to his patients. Following a discussion of reproductive anatomy, Knowlton addresses the mechanics of the conception, including information on the stages of a woman’s menstrual cycle, ovulation, properties of semen and sperm, fertilization, and pregnancy. He mentions some signs of pregnancy, including a decrease in appetite, vomiting and nausea in the morning, heartburn, and difficulty sleeping. Knowlton notes that pregnancy cannot be confirmed until about six weeks after conception and is done via a pelvic examination that reveals the woman’s uterus has descended lower in her body than it normally sits. He states that pregnancy is typically nine months, during which the fetus grows and develops in the uterus.

In the last part of chapter two, Knowlton states that at the time physicians still did not fully understand how the sperm reached the eggs in the ovaries leading to fertilization. He cites three hypotheses for the mechanism that leads to fertilization and states that he agrees most with physician William Potts Dewees from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Dewees suggested that a set of vessels connected the surface of the vagina to the ovaries. During intercourse, a man’s semen was absorbed by those vessels on the surface of a woman’s vagina and allowed the sperm to flow into the fallopian tube to fertilize the woman’s egg. In a footnote from the publishers, Bradlaugh and Besant state that that view of fertilization is no longer accepted by the scientific community. Rather, they state that it has now been discovered that eggs or ova are discharged from the ovaries into the uterus during the menstrual cycle and independent of intercourse. Bradlaugh and Besant state that if intercourse and ejaculation of semen occurs when the ova is in the uterus, conception can take place.

In the third chapter of The Fruits of Philosophy, Knowlton highlights some methods of controlling and preventing conception. First, Knowlton asserts that conception will be difficult for women who do not menstruate regularly. He states that for a woman to conceive, a physician must first regulate the woman’s menstrual cycle. He then mentions that sterility can occur naturally, which he attributes to physiological inactivity and a weakness of the reproductive system. Knowlton then provides a remedy for that type of sterility: exercising in open air, eating nourishing food, wearing flannel clothing, and drinking a concoction of steel metal shavings and cider. He states that those activities heal the uterine system over the course of a few months. He includes other medical recipes for sterility such as Dewees’ Volatile Tincture of Guaiac, Gum Guaicaum, Spirits of Ammonia, and tincture of Spanish Flies, among others. Knowlton also discusses infertility and impotence among men, and often attributes it to alcohol or tobacco use, and general anxiety. Common treatments for male infertility include cold baths, cheerful company, change of scenery, regular exercise, and medical remedies such as cayenne and tincture of flies.

Knowlton goes on to discuss methods of preventing conception. First, he mentions withdrawal, or a man withdrawing his penis from a woman’s vagina before releasing any sperm. He also discusses the baudruche, also known as a condom, which covers the man’s penis and prevents both conception and venereal diseases. Knowlton argues the baudruche will likely not become popular. Then Knowlton discusses the use of a sponge moistened with water in the vagina to prevent sperm from traveling far enough to fertilize a woman’s egg. However, he argues that the ridges in the vagina could allow sperm to be dislodged when the sponge is removed, thus he does not recommend this method unless paired with some chemical liquid to destroy the sperm. He also adds that using a vaginal wash after sexual intercourse could chemically alter the sperm and prevent fertilization. For a vaginal wash, Knowlton recommends a solution of zinc, aluminum, pearl-ash, and a salt. Knowlton concludes the chapter by stating that it is important to have a safe, effective, and attainable method of contraception.

In the last chapter of the pamphlet, Knowlton discusses the reproductive instinct, which he states is the desire for sexual intercourse. He asserts that no other instinct has a greater impact on human happiness and satisfaction. However, he argues that too often the instinct is not controlled by reason and individuals act on the instinct in an improper manner. He argues that it is the duty of the physician to provide instruction in regards to the reproductive instinct, just as a physician would in regards to desires for eating, drinking, exercise, and more. He states that humans are likely to act on the instinct too early and at the wrong time, resulting in dissatisfaction within the family. He suggests that the proper age to have children is approximately seventeen years old for women and a few years older for men. He provides instances in which individuals should not gratify their sexual desires, including during menstruation because it can produce symptoms similar to syphilis and when a woman is far along in her pregnancy because it might impair the future offspring’s mental capacity. Knowlton also states that the effects of sex are much greater on men than women; he states that the male system is quickly exhausted by intercourse. He suggests that a protein rich diet will help men recover from intercourse, and a cold vegetable and milk diet will calm further sexual desires.

Knowlton concludes with a discussion of possible objections in the last section titled “Appendix.” He states that people may object to the knowledge of contraception as it may increase illegal sexual encounters such as prostitution, adultery, or intercourse outside of marriage. However, Knowlton counters by saying that prostitution occurs because there are so many young unmarried men and women. He continues by saying that young men and women don’t marry not because they don’t wish to marry young, but because they believe that when they marry they will have children and start a family. Knowlton argues that the spread of information on pregnancy prevention will lead to an increase in happy families and fewer poverty-stricken, overpopulated families.

After Besant and Bradlaugh republished Knowlton’s pamphlet, they were arrested for violating the Obscene Publications Act of 1857, which made the sale of obscene literature illegal in England. Bradlaugh and Besant were convicted and sentenced to jail. However, on appeal, their convictions were overturned. The trial of Bradlaugh and Besant was heavily publicized in the media and the number of copies of the pamphlet in circulation increased from 700 to 125,000 in the span of one year.

Sources

Chandrasekhar, Sripati. A Dirty Filthy Book. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Dewees, William Potts. A Treatise on the Physical and Medical Treatment of Children. Blanchard and Lea, 1858.

Knowlton, Charles. The Fruits of Philosophy: The Private Companion for Young Married People. London: James Watson, 1832.

Knowlton, Charles. “The Late Charles Knowlton, M.D.” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 45 (1851): 109–20.

Knowlton, Charles. Fruits of Philosophy: A Treatise on the Population Question. Eds. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant. San Francisco: The Reader’s Library, 1891. https://archive.org/details/fruitsphilosoph00knogoog (Accessed August 17, 2017).

Malthus, Thomas. An Essay on the Principle of Population: Or A View of Its Past and Present Effects on Human Happiness with an Inquiry into our Prospects Respecting the Future Removal or Mitigation of the Evils which it Occasions. London: John Murray. Volume One. Sixth Edition, 1826.

Manvell, Roger. The Trial of Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh. New York: Horizon Press, 1976.

Sappol, Michael. “The Odd Case of Charles Knowlton: Anatomical Performance, Medical Narrative, and Identity in Antebellum America.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 83 (2009): 460–98.

How to cite

Meek, Caroline,, Nunez-Eddy, Claudia, "The Fruits of Philosophy (1832), by Charles Knowlton". Embryo Project Encyclopedia (2017-10-05). ISSN: 1940-5030 http://embryo.asu.edu/handle/10776/12993.

Show full item record

Publisher

Arizona State University. School of Life Sciences. Center for Biology and Society. Embryo Project Encyclopedia.

Rights

Copyright Arizona Board of Regents Licensed as Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Freethought

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/26/20

Not to be confused with freedom of thought or free will.

Freethought (or free thought)[1] is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that positions regarding truth should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism, rather than authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a freethinker is "a person who forms their own ideas and opinions rather than accepting those of other people, especially in religious teaching." In some contemporary thought in particular, freethought is strongly tied with rejection of traditional social or religious belief systems.[1][2] The cognitive application of freethought is known as "freethinking", and practitioners of freethought are known as "freethinkers".[1] Modern freethinkers consider freethought as a natural freedom from all negative and illusive thoughts acquired from the society.[3]

The term first came into use in the 17th century in order to indicate people who inquired into the basis of traditional religious beliefs. In practice, freethinking is most closely linked with secularism, atheism, agnosticism, anti-clericalism, and religious critique. The Oxford English Dictionary defines freethinking as, "The free exercise of reason in matters of religious belief, unrestrained by deference to authority; the adoption of the principles of a free-thinker." Freethinkers hold that knowledge should be grounded in facts, scientific inquiry, and logic. The skeptical application of science implies freedom from the intellectually limiting effects of confirmation bias, cognitive bias, conventional wisdom, popular culture, prejudice, or sectarianism.[4]

Definition

Atheist author Adam Lee defines freethought as thinking which is independent of revelation, tradition, established belief, and authority,[5] and considers it as a "broader umbrella" than atheism "that embraces a rainbow of unorthodoxy, religious dissent, skepticism, and unconventional thinking."[6]

The basic summarizing statement of the essay The Ethics of Belief by the 19th-century British mathematician and philosopher William Kingdon Clifford is: "It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence."[7] The essay became a rallying cry for freethinkers when published in the 1870s, and has been described as a point when freethinkers grabbed the moral high ground.[8] Clifford was himself an organizer of freethought gatherings, the driving force behind the Congress of Liberal Thinkers held in 1878.

Regarding religion, freethinkers typically hold that there is insufficient evidence to support the existence of supernatural phenomena.[9] According to the Freedom from Religion Foundation, "No one can be a freethinker who demands conformity to a bible, creed, or messiah. To the freethinker, revelation and faith are invalid, and orthodoxy is no guarantee of truth." and "Freethinkers are convinced that religious claims have not withstood the tests of reason. Not only is there nothing to be gained by believing an untruth, but there is everything to lose when we sacrifice the indispensable tool of reason on the altar of superstition. Most freethinkers consider religion to be not only untrue, but harmful."[10]

However, philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote the following in his 1944 essay "The Value of Free Thought:"

The whole first paragraph of the essay makes it clear that a freethinker is not necessarily an atheist or an agnostic, as long as he or she satisfies this definition:

Fred Edwords, former executive of the American Humanist Association, suggests that by Russell's definition, liberal religionists who have challenged established orthodoxies can be considered freethinkers.[11]

On the other hand, according to Bertrand Russell, atheists and/or agnostics are not necessarily freethinkers. As an example, he mentions Stalin, whom he compares to a "pope":

In the 18th and 19th century, many thinkers regarded as freethinkers were deists, arguing that the nature of God can only be known from a study of nature rather than from religious revelation. In the 18th century, "deism" was as much of a 'dirty word' as "atheism", and deists were often stigmatized as either atheists or at least as freethinkers by their Christian opponents.[12][13] Deists today regard themselves as freethinkers, but are now arguably less prominent in the freethought movement than atheists.

Characteristics

Among freethinkers, for a notion to be considered true it must be testable, verifiable, and logical. Many freethinkers tend to be humanists, who base morality on human needs and would find meaning in human compassion, social progress, art, personal happiness, love, and the furtherance of knowledge. Generally, freethinkers like to think for themselves, tend to be skeptical, respect critical thinking and reason, remain open to new concepts, and are sometimes proud of their own individuality. They would determine truth for themselves – based upon knowledge they gain, answers they receive, experiences they have and the balance they thus acquire. Freethinkers reject conformity for the sake of conformity, whereby they create their own beliefs by considering the way the world around them works and would possess the intellectual integrity and courage to think outside of accepted norms, which may or may not lead them to believe in some higher power.[14]

Symbol

The pansy, a symbol of freethought.

The pansy serves as the long-established and enduring symbol of freethought; literature of the American Secular Union inaugurated its usage in the late 1800s. The reasoning behind the pansy as the symbol of freethought lies both in the flower's name and in its appearance. The pansy derives its name from the French word pensée, which means "thought". It allegedly received this name because the flower is perceived by some to bear resemblance to a human face, and in mid-to-late summer it nods forward as if deep in thought.[15] Challenging Religious Dogma: A History of Free Thought, a pamphlet dating from the 1880s had this statement under the title "The Pansy Badge":[16]

History

Pre-modern movement

Critical thought has flourished in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, in the repositories of knowledge and wisdom in Ireland and in the Iranian civilizations (for example in the era of Khayyam (1048–1131) and his unorthodox Sufi Rubaiyat poems), and in other civilizations, such as the Chinese (note for example the seafaring renaissance of the Southern Song dynasty of 420–479),[17] and on through heretical thinkers on esoteric alchemy or astrology, to the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation.

French physician and writer Rabelais celebrated "rabelaisian" freedom as well as good feasting and drinking (an expression and a symbol of freedom of the mind) in defiance of the hypocrisies of conformist orthodoxy in his utopian Thelema Abbey (from θέλημα: free "will"), the device of which was Do What Thou Wilt:

When Rabelais's hero Pantagruel journeys to the "Oracle of The Div(in)e Bottle", he learns the lesson of life in one simple word: "Trinch!", Drink! Enjoy the simple life, learn wisdom and knowledge, as a free human. Beyond puns, irony, and satire, Gargantua's prologue-metaphor instructs the reader to "break the bone and suck out the substance-full marrow" ("la substantifique moëlle"), the core of wisdom.

Modern movements

Freethought logo

The year 1600 is considered a landmark in the era of modern freethought. It was the year of the execution in Italy of Giordano Bruno, a former Dominican friar, by the Inquisition.[18][19][20]

England

The term free-thinker emerged towards the end of the 17th century in England to describe those who stood in opposition to the institution of the Church, and the literal belief in the Bible. The beliefs of these individuals were centered on the concept that people could understand the world through consideration of nature. Such positions were formally documented for the first time in 1697 by William Molyneux in a widely publicized letter to John Locke, and more extensively in 1713, when Anthony Collins wrote his Discourse of Free-thinking, which gained substantial popularity. This essay attacks the clergy of all churches and it is a plea for deism.

The Freethinker magazine was first published in Britain in 1881.

France

In France, the concept first appeared in publication in 1765 when Denis Diderot, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and Voltaire included an article on Liberté de penser in their Encyclopédie.[21] The European freethought concepts spread so widely that even places as remote as the Jotunheimen, in Norway, had well-known freethinkers such as Jo Gjende by the 19th century.[22]

François-Jean Lefebvre de la Barre (1745–1766) was a young French nobleman, famous for having been tortured and beheaded before his body was burnt on a pyre along with Voltaire's Philosophical Dictionary. La Barre is often said to have been executed for not saluting a Roman Catholic religious procession, but the elements of the case were far more complex.[23]

In France, Lefebvre de la Barre is widely regarded a symbol of the victims of Christian religious intolerance; La Barre along with Jean Calas and Pierre-Paul Sirven, was championed by Voltaire. A second replacement statue to de la Barre stands nearby the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Jesus of Paris at the summit of the butte Montmartre (itself named from the Temple of Mars), the highest point in Paris and an 18th arrondissement street nearby the Sacré-Cœur is also named after Lefebvre de la Barre.

Germany

In Germany, during the period 1815–1848 and before the March Revolution, the resistance of citizens against the dogma of the church increased. In 1844, under the influence of Johannes Ronge and Robert Blum, belief in the rights of man, tolerance among men, and humanism grew, and by 1859 they had established the Bund Freireligiöser Gemeinden Deutschlands (literally Union of Free Religious Communities of Germany), an association of persons who consider themselves to be religious without adhering to any established and institutionalized church or sacerdotal cult. This union still exists today, and is included as a member in the umbrella organization of free humanists. In 1881 in Frankfurt am Main, Ludwig Büchner established the Deutscher Freidenkerbund (German Freethinkers League) as the first German organization for atheists and agnostics. In 1892 the Freidenker-Gesellschaft and in 1906 the Deutscher Monistenbund were formed.[24]

Freethought organizations developed the "Jugendweihe" (literally Youth consecration), a secular "confirmation" ceremony, and atheist funeral rites.[24][25] The Union of Freethinkers for Cremation was founded in 1905, and the Central Union of German Proletariat Freethinker in 1908. The two groups merged in 1927, becoming the German Freethinking Association in 1930.[26]

More "bourgeois" organizations declined after World War I, and "proletarian" Freethought groups proliferated, becoming an organization of socialist parties.[24][27] European socialist freethought groups formed the International of Proletarian Freethinkers (IPF) in 1925.[28] Activists agitated for Germans to disaffiliate from their respective Church and for seculari-zation of elementary schools; between 1919–21 and 1930–32 more than 2.5 million Germans, for the most part supporters of the Social Democratic and Communist parties, gave up church membership.[29] Conflict developed between radical forces including the Soviet League of the Militant Godless and Social Democratic forces in Western Europe led by Theodor Hartwig and Max Sievers.[28] In 1930 the Soviet and allied delegations, following a walk-out, took over the IPF and excluded the former leaders.[28] Following Hitler's rise to power in 1933, most freethought organizations were banned, though some right-wing groups that worked with so-called Völkische Bünde (literally "ethnic" associations with nationalist, xenophobic and very often racist ideology) were tolerated by the Nazis until the mid-1930s.[24][27]

Belgium

Main article: Organized secularism

The Université Libre de Bruxelles and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, along with the two Circles of Free Inquiry (Dutch and French speaking), defend the freedom of critical thought, lay philosophy and ethics, while rejecting the argument of authority.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, freethought has existed in organized form since the establishment of De Dageraad (now known as De Vrije Gedachte) in 1856. Among its most notable subscribing 19th century individuals were Johannes van Vloten, Multatuli, Adriaan Gerhard and Domela Nieuwenhuis.

In 2009, Frans van Dongen established the Atheist-Secular Party, which takes a considerably restrictive view of religion and public religious expressions.

Since the 19th century, Freethought in the Netherlands has become more well known as a political phenomenon through at least three currents: liberal freethinking, conservative freethinking, and classical freethinking. In other words, parties which identify as freethinking tend to favor non-doctrinal, rational approaches to their preferred ideologies, and arose as secular alternatives to both clerically aligned parties as well as labor-aligned parties. Common themes among freethinking political parties are "freedom", "liberty", and "individualism".

Switzerland

Main article: Freethinkers Association of Switzerland

With the introduction of cantonal church taxes in the 1870s, anti-clericals began to organise themselves. Around 1870, a "freethinkers club" was founded in Zürich. During the debate on the Zürich church law in 1883, professor Friedrich Salomon Vögelin and city council member Kunz proposed to separate church and state.[30]

Turkey

In the last years of the Ottoman Empire, freethought made its voice heard by the works of distinguished people such as Ahmet Rıza, Tevfik Fikret, Abdullah Cevdet, Kılıçzade Hakkı, and Celal Nuri İleri. These intellectuals affected the early period of the Turkish Republic. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk –field marshal, revolutionary statesman, author, and founder of the secular Turkish nation state, serving as its first President from 1923 until his death in 1938– was the practitioner of their ideas. He made many reforms that modernized the country. Sources point out that Atatürk was a religious skeptic and a freethinker. He was a non-doctrinaire deist[31][32] or an atheist,[33][34][35] who was antireligious and anti-Islamic in general.[36][37] According to Atatürk, the Turkish people do not know what Islam really is and do not read the Quran. People are influenced by Arabic sentences that they do not understand, and because of their customs they go to mosques. When the Turks read the Quran and think about it, they will leave Islam.[38] Atatürk described Islam as the religion of the Arabs in his own work titled Vatandaş için Medeni Bilgiler by his own critical and nationalist views.[39]

Association of Atheism (Ateizm Derneği), the first official atheist organisation in Middle East and Caucasus, was founded in 2014.[40] It serves to support irreligious people and freethinkers in Turkey who are discriminated against based on their views. In 2018 it was reported in some media outlets that the Ateizm Derneği would close down because of the pressure on its members and attacks by pro-government media, but the association itself issued a clarification that this was not the case and that it was still active.[41]

United States

The Free Thought movement first organized itself in the United States as the "Free Press Association" in 1827 in defense of George Houston, publisher of The Correspondent, an early journal of Biblical criticism in an era when blasphemy convictions were still possible. Houston had helped found an Owenite community at Haverstraw, New York in 1826–27. The short-lived Correspondent was superseded by the Free Enquirer, the official organ of Robert Owen's New Harmony community in Indiana, edited by Robert Dale Owen and by Fanny Wright between 1828 and 1832 in New York. During this time Robert Dale Owen sought to introduce the philosophic skepticism of the Free Thought movement into the Workingmen's Party in New York City. The Free Enquirer's annual civic celebrations of Paine's birthday after 1825 finally coalesced in 1836 in the first national Free Thinkers organization, the "United States Moral and Philosophical Society for the General Diffusion of Useful Knowledge". It was founded on August 1, 1836, at a national convention at the Lyceum in Saratoga Springs with Isaac S. Smith of Buffalo, New York, as president. Smith was also the 1836 Equal Rights Party's candidate for Governor of New York and had also been the Workingmen's Party candidate for Lt. Governor of New York in 1830. The Moral and Philosophical Society published The Beacon, edited by Gilbert Vale.[42]

Robert G. Ingersoll[43]

Driven by the revolutions of 1848 in the German states, the 19th century saw an immigration of German freethinkers and anti-clericalists to the United States (see Forty-Eighters). In the United States, they hoped to be able to live by their principles, without interference from government and church authorities.[44]

Many Freethinkers settled in German immigrant strongholds, including St. Louis, Indianapolis, Wisconsin, and Texas, where they founded the town of Comfort, Texas, as well as others.[44]

These groups of German Freethinkers referred to their organizations as Freie Gemeinden, or "free congregations".[44] The first Freie Gemeinde was established in St. Louis in 1850.[45] Others followed in Pennsylvania, California, Washington, D.C., New York, Illinois, Wisconsin, Texas, and other states.[44][45]

Freethinkers tended to be liberal, espousing ideals such as racial, social, and sexual equality, and the abolition of slavery.[44]

The "Golden Age of Freethought" in the US came in the late 1800s. The dominant organization was the National Liberal League which formed in 1876 in Philadelphia. This group re-formed itself in 1885 as the American Secular Union under the leadership of the eminent agnostic orator Robert G. Ingersoll. Following Ingersoll's death in 1899 the organization declined, in part due to lack of effective leadership.[46]

Freethought in the United States declined in the early twentieth century. By the early twentieth century, most Freethought congregations had disbanded or joined other mainstream churches. The longest continuously operating Freethought congregation in America is the Free Congregation of Sauk County, Wisconsin, which was founded in 1852 and is still active as of 2020. It affiliated with the American Unitarian Association (now the Unitarian Universalist Association) in 1955.[47] D. M. Bennett was the founder and publisher of The Truth Seeker in 1873, a radical freethought and reform American periodical.

German Freethinker settlements were located in:

• Burlington, Racine County, Wisconsin[44]

• Belleville, St. Clair County, Illinois

• Castell, Llano County, Texas

• Comfort, Kendall County, Texas

• Davenport, Scott County, Iowa[48]

• Fond du Lac, Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin[44]

• Frelsburg, Colorado County, Texas

• Hermann, Gasconade County, Missouri

• Jefferson, Jefferson County, Wisconsin[44]

• Indianapolis, Indiana[49]

• Latium, Washington County, Texas

• Manitowoc, Manitowoc County, Wisconsin[44]

• Meyersville, DeWitt County, Texas

• Milwaukee, Wisconsin[44]

• Millheim, Austin County, Texas

• Oshkosh, Winnebago County, Wisconsin[44]

• Ratcliffe, DeWitt County, Texas

• Sauk City, Sauk County, Wisconsin[44][47]

• Shelby, Austin County, Texas

• Sisterdale, Kendall County, Texas

• St. Louis, Missouri

• Tusculum, Kendall County, Texas

• Two Rivers, Manitowoc County, Wisconsin[44]

• Watertown, Dodge County, Wisconsin[44]

Canada

In 1873 a handful of secularists founded the earliest known secular organization in English Canada, the Toronto Freethought Association. Reorganized in 1877 and again in 1881, when it was renamed the Toronto Secular Society, the group formed the nucleus of the Canadian Secular Union, established in 1884 to bring together freethinkers from across the country.[50]

A significant number of the early members appear to have come from the educated labour "aristocracy", including Alfred F. Jury, J. Ick Evans and J. I. Livingstone, all of whom were leading labour activists and secularists. The second president of the Toronto association, T. Phillips Thompson, became a central figure in the city's labour and social-reform movements during the 1880s and 1890s and arguably Canada's foremost late nineteenth-century labour intellectual. By the early 1880s scattered freethought organizations operated throughout southern Ontario and parts of Quebec, eliciting both urban and rural support.

The principal organ of the freethought movement in Canada was Secular Thought (Toronto, 1887–1911). Founded and edited during its first several years by English freethinker Charles Watts (1835–1906), it came under the editorship of Toronto printer and publisher James Spencer Ellis in 1891 when Watts returned to England. In 1968 the Humanist Association of Canada (HAC) formed to serve as an umbrella group for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers, and to champion social justice issues and oppose religious influence on public policy—most notably in the fight to make access to abortion free and legal in Canada.

Anarchism

In the United States of America,

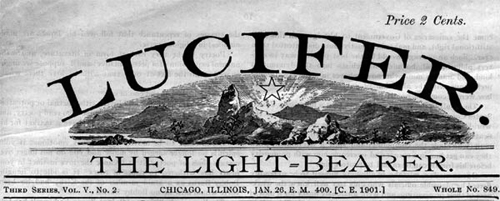

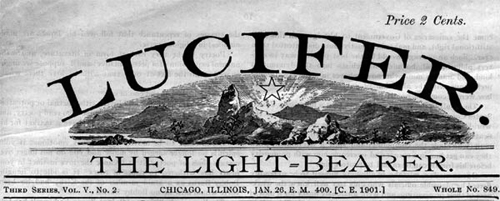

"Many of the anarchists were ardent freethinkers; reprints from freethought papers such as Lucifer, the Light-Bearer, Freethought and The Truth Seeker appeared in Liberty...The church was viewed as a common ally of the state and as a repressive force in and of itself."[51]

In Europe, a similar development occurred in French and Spanish individualist anarchist circles:

These tendencies would continue in French individualist anarchism in the work and activism of Charles-Auguste Bontemps (1893-1981) and others. In the Spanish individualist anarchist magazines Ética and Iniciales

In 1901 the Catalan anarchist and freethinker Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia established "modern" or progressive schools in Barcelona in defiance of an educational system controlled by the Catholic Church.[54] The schools had the stated goal to "educate the working class in a rational, secular and non-coercive setting". Fiercely anti-clerical, Ferrer believed in "freedom in education", education free from the authority of church and state.[55][failed verification] Ferrer's ideas, generally, formed the inspiration for a series of Modern Schools in the United States,[54] Cuba, South America and London. The first of these started in New York City in 1911. Ferrer also inspired the Italian newspaper Università popolare, founded in 1901.[54]

See also

• Brights movement

• Critical rationalism

• Ethical movement

• Secular humanism

• Freedom of thought

• Freethought Association of Canada

• Freethought Day

• Golden Age of Freethought

• Individualism

• Objectivism

• Rationalism

• Religious skepticism

• Scientism

• Secular Thought

• Spiritual but not religious

• The Freethinker (journal)

Notes and references

1. "Freethinker – Definition of freethinker by Merriam-Webster". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

2. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-01-17. Retrieved 2012-02-03.

3. "Nontracts". Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

4. "who are the Freethinkers?". Freethinkers.com. 2018-02-13. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

5. "What Is Freethought?". Daylight Atheism. 2010-02-26. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

6. Adam Lee (October 2012). "9 Great Freethinkers and Religious Dissenters in History". Big Think. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

7. William Kingdon Clifford, The Ethics of Belief (1879 [1877]).

8. Becker, Lawrence and Charlotte (2013). Encyclopedia of Ethics (article on "agnosticism"). Routledge. p. 44. ISBN 9781135350963.

9. Hastings, James (2003-01-01). Encyclopedia of Religion. ISBN 9780766136830.

10. "What is a Freethinker? - Freedom From Religion Foundation". Retrieved 12 June 2015.

11. "Saga Of Freethought And Its Pioneers". American Humanist Association. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

12. James E. Force, Introduction (1990) to An Account of the Growth of Deism in England (1696) by William Stephens

13. Aveling, Francis, ed. (1908). "Deism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2012-10-10. The deists were what nowadays would be called freethinkers, a name, indeed, by which they were not infrequently known; and they can only be classed together wholly in the main attitude that they adopted, viz. in agreeing to cast off the trammels of authoritative religious teaching in favour of a free and purely rationalistic speculation.... Deism, in its every manifestation was opposed to the current and traditional teaching of revealed religion.

14. A COMMON PLACE by Ruth Kelly and Liam Byrne

15. A Pansy For Your Thoughts, by Annie Laurie Gaylor, Freethought Today, June/July 1997

16. The Pansy of Freethought - Rediscovering A Forgotten Symbol Of Freethought by Annie Laurie Gaylor

17. Chinese History – Song Dynasty 宋 (http://www.chinaknowledge.de)

18. Gatti, Hilary (2002). Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science: Broken Lives and Organizational Power. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0801487859. Retrieved 21 March 2014. For Bruno was claiming for the philosopher a principle of free thought and inquiry which implied an entirely new concept of authority: that of the individual intellect in its serious and continuing pursuit of an autonomous inquiry… It is impossible to understand the issue involved and to evaluate justly the stand made by Bruno with his life without appreciating the question of free thought and liberty of expression. His insistence on placing this issue at the center of both his work and of his defense is why Bruno remains so much a figure of the modern world. If there is, as many have argued, an intrinsic link between science and liberty of inquiry, then Bruno was among those who guaranteed the future of the newly emerging sciences, as well as claiming in wider terms a general principle of free thought and expression.

19. Montano, Aniello (24 November 2007). Antonio Gargano (ed.). Le deposizioni davanti al tribunale dell'Inquisizione. Napoli: La Città del Sole. p. 71. In Rome, Bruno was imprisoned for seven years and subjected to a difficult trial that analyzed, minutely, all his philosophical ideas. Bruno, who in Venice had been willing to recant some theses, become increasingly resolute and declared on 21 December 1599 that he 'did not wish to repent of having too little to repent, and in fact did not know what to repent.' Declared an unrepentant heretic and excommunicated, he was burned alive in the Campo dei Fiori in Rome on 17 February 1600. On the stake, along with Bruno, burned the hopes of many, including philosophers and scientists of good faith like Galileo, who thought they could reconcile religious faith and scientific research, while belonging to an ecclesiastical organization declaring itself to be the custodian of absolute truth and maintaining a cultural militancy requiring continual commitment and suspicion.

20. Birx, James (11 November 1997). "Giordano Bruno". Mobile Alabama Harbinger. Retrieved 28 April 2014. To me, Bruno is the supreme martyr for both free thought and critical inquiry… Bruno's critical writings, which pointed out the hypocrisy and bigotry within the Church, along with his tempestuous personality and undisciplined behavior, easily made him a victim of the religious and philosophical intolerance of the 16th century. Bruno was excommunicated by the Catholic, Lutheran and Calvinist Churches for his heretical beliefs. The Catholic hierarchy found him guilty of infidelity and many errors, as well as serious crimes of heresy… Bruno was burned to death at the stake for his pantheistic stance and cosmic perspective.

21. "ARTFL Encyclopédie Search Results". 1751–1772. p. 472. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

22. "Gjendesheim". MEMIM. 2016. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

23. Gregory, Mary Efrosini (2008). Evolutionism in Eighteenth-century French Thought. Peter Lang. p. 192. ISBN 9781433103735. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

24. Bock, Heike (2006). "Secularization of the modern conduct of life? Reflections on the religiousness of early modern Europe". In Hanne May (ed.). Religiosität in der säkularisierten Welt. VS Verlag fnr Sozialw. p. 157. ISBN 978-3-8100-4039-8.

25. Reese, Dagmar (2006). Growing up female in Nazi Germany. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-472-06938-5.

26. Reinhalter, Helmut (1999). "Freethinkers". In Bromiley, Geoffrey William; Fahlbusch, Erwin (eds.). The encyclopedia of Christianity. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

27. Kaiser, Jochen-Christoph (2003). Christel Gärtner (ed.). Atheismus und religiöse Indifferenz. Organisierter Atheismus. VS Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8100-3639-1.

28. Peris, Daniel (1998). Storming the heavens: the Soviet League of the Militant Godless. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. pp. 110–11. ISBN 978-0-8014-3485-3.

29. Lamberti, Marjorie (2004). Politics Of Education: Teachers and School Reform in Weimar Germany (Monographs in German History). Providence: Berghahn Books. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-57181-299-5.

30. "Geschichte der Freidenker". FAS website (in German). Retrieved 10 May 2016.

31. Reşat Kasaba, "Atatürk", The Cambridge history of Turkey: Volume 4: Turkey in the Modern World, Cambridge University Press, 2008; ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3 p. 163; accessed 27 March 2015.

32. Political Islam in Turkey by Gareth Jenkins, Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, p. 84; ISBN 0230612458

33. Atheism, Brief Insights Series by Julian Baggini, Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2009; ISBN 1402768826, p. 106.

34. Islamism: A Documentary and Reference Guide, John Calvert John, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008; ISBN 0313338566, p. 19.

35. Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of the secular Turkish Republic said: "I have no religion, and at times I wish all religions at the bottom of the sea..." The Antipodean Philosopher: Interviews on Philosophy in Australia and New Zealand, Graham Oppy, Lexington Books, 2011, ISBN 0739167936, p. 146.

36. Phil Zuckerman, John R. Shook, The Oxford Handbook of Secularism, Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 0199988455, p. 167.

37. Tariq Ramadan, Islam and the Arab Awakening, Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0199933731, p. 76.

38. Atatürk İslam için ne düşünüyordu?

39.

“ Even before accepting the religion of the Arabs, the Turks were a great nation. After accepting the religion of the Arabs, this religion, didn't effect to combine the Arabs, the Persians and Egyptians with the Turks to constitute a nation. (This religion) rather, loosened the national nexus of Turkish nation, got national excitement numb. This was very natural. Because the purpose of the religion founded by Muhammad, over all nations, was to drag to an including Arab national politics. (Afet İnan, Medenî Bilgiler ve M. Kemal Atatürk'ün El Yazıları, Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1998, p. 364.) ”

40. "The first Atheist Association in Turkey is founded". http://turkishatheist.net. Retrieved 2 April 2017. External link in |website= (help)

41. "Turkey's Atheism Association threatened by hostility and lack of interest | Ahval". Ahval. Retrieved 2018-10-21.

42. Hugins, Walter (1960). Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class: A Study of the New York Workingmen's Movement 1829–1837. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 36–48.

43. Brandt, Eric T., and Timothy Larsen (2011). "The Old Atheism Revisited: Robert G. Ingersoll and the Bible". Journal of the Historical Society. 11 (2): 211–38. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5923.2011.00330.x.

44. "Freethinkers in Wisconsin". Dictionary of Wisconsin History. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

45. Demerath, N. J. III and Victor Thiessen, "On Spitting Against the Wind: Organizational Precariousness and American Irreligion," The American Journal of Sociology, 71: 6 (May, 1966), 674–87.

46. "National Liberal League". The Freethought Trail. freethought-trail.org. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

47. "History of the Free Congregation of Sauk County: The "Freethinkers" Story". Free Congregation of Sauk County. April 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2012-02-05.

48. William Roba; Fredrick I. Anderson (ed.) (1982). Joined by a River: Quad Cities. Davenport: Lee Enterprises. p. 73.

49. "The Turners, Forty-eighters and Freethinkers". Freedom from Religion Foundation. July 2002. Archived from the originalon 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

50. *Ramsay Cook, The Regenerators: Social Criticism in Late Victorian English Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985), pp. 46–64.

51. "The Journal of Libertarian Studies" (PDF). Mises Institute. 2014-07-30. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

52. Xavier Diez. El anarquismo individualista en España (1923–1939) Virus Editorial. 2007. p. 143

53. Xavier Diez. El anarquismo individualista en España (1923–1939) Virus Editorial. 2007. p. 152

54. Geoffrey C. Fidler (Spring–Summer 1985). "The Escuela Moderna Movement of Francisco Ferrer: "Por la Verdad y la Justicia"". History of Education Quarterly. 25 (1/2): 103–32. doi:10.2307/368893. JSTOR 368893.

55. * "Francisco Ferrer's Modern School". Flag.blackened.net. Archived from the original on 2010-08-07. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

Further reading

• Alexander, Nathan G. (2019). Race in a Godless World: Atheism, Race, and Civilization, 1850-1914. New York/Manchester: New York University Press/Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1526142375

• Alexander Nathan G. "Unclasping the Eagle's Talons: Mark Twain, American Freethought, and the Responses to Imperialism." The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17, no. 3 (2018): 524–545.

• Bury, John Bagnell. (1913). A History of Freedom of Thought. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

• Jacoby, Susan. (2004). Freethinkers: A History of American Secularism. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-7442-2

• Putnam, Samuel Porter. (1894). Four Hundred Years of Freethought. New York: Truth Seeker Company.

• Royle, Edward. (1974). Victorian Infidels: The Origins of the British Secularist Movement, 1791–1866. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0557-4

• Royle, Edward. (1980). Radicals, Secularists and Republicans: popular freethought in Britain, 1866–1915. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-0783-6

• Tribe, David. (1967). 100 Years of Freethought. London: Elek Books.

External links

• Freethinker Indonesia

• A History of Freethought

• Young Freethought

• "Freethinker" . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

• Philosophy portal

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/26/20

Not to be confused with freedom of thought or free will.

Freethought (or free thought)[1] is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that positions regarding truth should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism, rather than authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a freethinker is "a person who forms their own ideas and opinions rather than accepting those of other people, especially in religious teaching." In some contemporary thought in particular, freethought is strongly tied with rejection of traditional social or religious belief systems.[1][2] The cognitive application of freethought is known as "freethinking", and practitioners of freethought are known as "freethinkers".[1] Modern freethinkers consider freethought as a natural freedom from all negative and illusive thoughts acquired from the society.[3]

The term first came into use in the 17th century in order to indicate people who inquired into the basis of traditional religious beliefs. In practice, freethinking is most closely linked with secularism, atheism, agnosticism, anti-clericalism, and religious critique. The Oxford English Dictionary defines freethinking as, "The free exercise of reason in matters of religious belief, unrestrained by deference to authority; the adoption of the principles of a free-thinker." Freethinkers hold that knowledge should be grounded in facts, scientific inquiry, and logic. The skeptical application of science implies freedom from the intellectually limiting effects of confirmation bias, cognitive bias, conventional wisdom, popular culture, prejudice, or sectarianism.[4]

Definition

Atheist author Adam Lee defines freethought as thinking which is independent of revelation, tradition, established belief, and authority,[5] and considers it as a "broader umbrella" than atheism "that embraces a rainbow of unorthodoxy, religious dissent, skepticism, and unconventional thinking."[6]

The basic summarizing statement of the essay The Ethics of Belief by the 19th-century British mathematician and philosopher William Kingdon Clifford is: "It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence."[7] The essay became a rallying cry for freethinkers when published in the 1870s, and has been described as a point when freethinkers grabbed the moral high ground.[8] Clifford was himself an organizer of freethought gatherings, the driving force behind the Congress of Liberal Thinkers held in 1878.

Regarding religion, freethinkers typically hold that there is insufficient evidence to support the existence of supernatural phenomena.[9] According to the Freedom from Religion Foundation, "No one can be a freethinker who demands conformity to a bible, creed, or messiah. To the freethinker, revelation and faith are invalid, and orthodoxy is no guarantee of truth." and "Freethinkers are convinced that religious claims have not withstood the tests of reason. Not only is there nothing to be gained by believing an untruth, but there is everything to lose when we sacrifice the indispensable tool of reason on the altar of superstition. Most freethinkers consider religion to be not only untrue, but harmful."[10]

However, philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote the following in his 1944 essay "The Value of Free Thought:"

What makes a freethinker is not his beliefs but the way in which he holds them. If he holds them because his elders told him they were true when he was young, or if he holds them because if he did not he would be unhappy, his thought is not free; but if he holds them because, after careful thought he finds a balance of evidence in their favour, then his thought is free, however odd his conclusions may seem.

— Bertrand Russell, The Value of Free Thought. How to Become a Truth-Seeker and Break the Chains of Mental Slavery, from the first paragraph

The whole first paragraph of the essay makes it clear that a freethinker is not necessarily an atheist or an agnostic, as long as he or she satisfies this definition:

The person who is free in any respect is free from something; what is the free thinker free from? To be worthy of the name, he must be free of two things: the force of tradition, and the tyranny of his own passions. No one is completely free from either, but in the measure of a man's emancipation he deserves to be called a free thinker.

— Bertrand Russell, The Value of Free Thought. How to Become a Truth-Seeker and Break the Chains of Mental Slavery, from the first paragraph

Fred Edwords, former executive of the American Humanist Association, suggests that by Russell's definition, liberal religionists who have challenged established orthodoxies can be considered freethinkers.[11]

On the other hand, according to Bertrand Russell, atheists and/or agnostics are not necessarily freethinkers. As an example, he mentions Stalin, whom he compares to a "pope":

what I am concerned with is the doctrine of the modern Communistic Party, and of the Russian Government to which it owes allegiance. According to this doctrine, the world develops on the lines of a Plan called Dialectical Materialism, first discovered by Karl Marx, embodied in the practice of a great state by Lenin, and now expounded from day to day by a Church of which Stalin is the Pope. […] Free discussion is to be prevented wherever the power to do so exists; […] If this doctrine and this organization prevail, free inquiry will become as impossible as it was in the middle ages, and the world will relapse into bigotry and obscurantism.

— Bertrand Russell, The Value of Free Thought. How to Become a Truth-Seeker and Break the Chains of Mental Slavery

In the 18th and 19th century, many thinkers regarded as freethinkers were deists, arguing that the nature of God can only be known from a study of nature rather than from religious revelation. In the 18th century, "deism" was as much of a 'dirty word' as "atheism", and deists were often stigmatized as either atheists or at least as freethinkers by their Christian opponents.[12][13] Deists today regard themselves as freethinkers, but are now arguably less prominent in the freethought movement than atheists.

Characteristics

Among freethinkers, for a notion to be considered true it must be testable, verifiable, and logical. Many freethinkers tend to be humanists, who base morality on human needs and would find meaning in human compassion, social progress, art, personal happiness, love, and the furtherance of knowledge. Generally, freethinkers like to think for themselves, tend to be skeptical, respect critical thinking and reason, remain open to new concepts, and are sometimes proud of their own individuality. They would determine truth for themselves – based upon knowledge they gain, answers they receive, experiences they have and the balance they thus acquire. Freethinkers reject conformity for the sake of conformity, whereby they create their own beliefs by considering the way the world around them works and would possess the intellectual integrity and courage to think outside of accepted norms, which may or may not lead them to believe in some higher power.[14]

Symbol

The pansy, a symbol of freethought.

The pansy serves as the long-established and enduring symbol of freethought; literature of the American Secular Union inaugurated its usage in the late 1800s. The reasoning behind the pansy as the symbol of freethought lies both in the flower's name and in its appearance. The pansy derives its name from the French word pensée, which means "thought". It allegedly received this name because the flower is perceived by some to bear resemblance to a human face, and in mid-to-late summer it nods forward as if deep in thought.[15] Challenging Religious Dogma: A History of Free Thought, a pamphlet dating from the 1880s had this statement under the title "The Pansy Badge":[16]

There is . . . need of a badge which shall express at first glance, without complexity of detail, that basic principle of freedom of thought for which Liberals of all isms are contending. This need seems to have been met by the Freethinkers of France, Belgium, Spain and Sweden, who have adopted the pansy as their badge. We join with them in recommending this flower as a simple and inexpensive badge of Freethought...Let every patriot who is a Freethinker in this sense, adopt the pansy as his badge, to be worn at all times, as a silent and unobtrusive testimony of his principles. In this way we shall recognize our brethren in the cause, and the enthusiasm will spread; until, before long, the uplifted standard of the pansy, beneath the sheltering folds of the United States flag, shall everywhere thrill men's hearts as the symbol of religious liberty and freedom of conscience."

History

Pre-modern movement

Critical thought has flourished in the Hellenistic Mediterranean, in the repositories of knowledge and wisdom in Ireland and in the Iranian civilizations (for example in the era of Khayyam (1048–1131) and his unorthodox Sufi Rubaiyat poems), and in other civilizations, such as the Chinese (note for example the seafaring renaissance of the Southern Song dynasty of 420–479),[17] and on through heretical thinkers on esoteric alchemy or astrology, to the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation.

French physician and writer Rabelais celebrated "rabelaisian" freedom as well as good feasting and drinking (an expression and a symbol of freedom of the mind) in defiance of the hypocrisies of conformist orthodoxy in his utopian Thelema Abbey (from θέλημα: free "will"), the device of which was Do What Thou Wilt:

So had Gargantua established it. In all their rule and strictest tie of their order there was but this one clause to be observed, Do What Thou Wilt; because free people ... act virtuously and avoid vice. They call this honor.

When Rabelais's hero Pantagruel journeys to the "Oracle of The Div(in)e Bottle", he learns the lesson of life in one simple word: "Trinch!", Drink! Enjoy the simple life, learn wisdom and knowledge, as a free human. Beyond puns, irony, and satire, Gargantua's prologue-metaphor instructs the reader to "break the bone and suck out the substance-full marrow" ("la substantifique moëlle"), the core of wisdom.

Modern movements

Freethought logo

The year 1600 is considered a landmark in the era of modern freethought. It was the year of the execution in Italy of Giordano Bruno, a former Dominican friar, by the Inquisition.[18][19][20]

England

The term free-thinker emerged towards the end of the 17th century in England to describe those who stood in opposition to the institution of the Church, and the literal belief in the Bible. The beliefs of these individuals were centered on the concept that people could understand the world through consideration of nature. Such positions were formally documented for the first time in 1697 by William Molyneux in a widely publicized letter to John Locke, and more extensively in 1713, when Anthony Collins wrote his Discourse of Free-thinking, which gained substantial popularity. This essay attacks the clergy of all churches and it is a plea for deism.

The Freethinker magazine was first published in Britain in 1881.

France

In France, the concept first appeared in publication in 1765 when Denis Diderot, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and Voltaire included an article on Liberté de penser in their Encyclopédie.[21] The European freethought concepts spread so widely that even places as remote as the Jotunheimen, in Norway, had well-known freethinkers such as Jo Gjende by the 19th century.[22]

François-Jean Lefebvre de la Barre (1745–1766) was a young French nobleman, famous for having been tortured and beheaded before his body was burnt on a pyre along with Voltaire's Philosophical Dictionary. La Barre is often said to have been executed for not saluting a Roman Catholic religious procession, but the elements of the case were far more complex.[23]

In France, Lefebvre de la Barre is widely regarded a symbol of the victims of Christian religious intolerance; La Barre along with Jean Calas and Pierre-Paul Sirven, was championed by Voltaire. A second replacement statue to de la Barre stands nearby the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Jesus of Paris at the summit of the butte Montmartre (itself named from the Temple of Mars), the highest point in Paris and an 18th arrondissement street nearby the Sacré-Cœur is also named after Lefebvre de la Barre.

Germany

In Germany, during the period 1815–1848 and before the March Revolution, the resistance of citizens against the dogma of the church increased. In 1844, under the influence of Johannes Ronge and Robert Blum, belief in the rights of man, tolerance among men, and humanism grew, and by 1859 they had established the Bund Freireligiöser Gemeinden Deutschlands (literally Union of Free Religious Communities of Germany), an association of persons who consider themselves to be religious without adhering to any established and institutionalized church or sacerdotal cult. This union still exists today, and is included as a member in the umbrella organization of free humanists. In 1881 in Frankfurt am Main, Ludwig Büchner established the Deutscher Freidenkerbund (German Freethinkers League) as the first German organization for atheists and agnostics. In 1892 the Freidenker-Gesellschaft and in 1906 the Deutscher Monistenbund were formed.[24]

Freethought organizations developed the "Jugendweihe" (literally Youth consecration), a secular "confirmation" ceremony, and atheist funeral rites.[24][25] The Union of Freethinkers for Cremation was founded in 1905, and the Central Union of German Proletariat Freethinker in 1908. The two groups merged in 1927, becoming the German Freethinking Association in 1930.[26]

More "bourgeois" organizations declined after World War I, and "proletarian" Freethought groups proliferated, becoming an organization of socialist parties.[24][27] European socialist freethought groups formed the International of Proletarian Freethinkers (IPF) in 1925.[28] Activists agitated for Germans to disaffiliate from their respective Church and for seculari-zation of elementary schools; between 1919–21 and 1930–32 more than 2.5 million Germans, for the most part supporters of the Social Democratic and Communist parties, gave up church membership.[29] Conflict developed between radical forces including the Soviet League of the Militant Godless and Social Democratic forces in Western Europe led by Theodor Hartwig and Max Sievers.[28] In 1930 the Soviet and allied delegations, following a walk-out, took over the IPF and excluded the former leaders.[28] Following Hitler's rise to power in 1933, most freethought organizations were banned, though some right-wing groups that worked with so-called Völkische Bünde (literally "ethnic" associations with nationalist, xenophobic and very often racist ideology) were tolerated by the Nazis until the mid-1930s.[24][27]

Belgium

Main article: Organized secularism

The Université Libre de Bruxelles and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, along with the two Circles of Free Inquiry (Dutch and French speaking), defend the freedom of critical thought, lay philosophy and ethics, while rejecting the argument of authority.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, freethought has existed in organized form since the establishment of De Dageraad (now known as De Vrije Gedachte) in 1856. Among its most notable subscribing 19th century individuals were Johannes van Vloten, Multatuli, Adriaan Gerhard and Domela Nieuwenhuis.

In 2009, Frans van Dongen established the Atheist-Secular Party, which takes a considerably restrictive view of religion and public religious expressions.

Since the 19th century, Freethought in the Netherlands has become more well known as a political phenomenon through at least three currents: liberal freethinking, conservative freethinking, and classical freethinking. In other words, parties which identify as freethinking tend to favor non-doctrinal, rational approaches to their preferred ideologies, and arose as secular alternatives to both clerically aligned parties as well as labor-aligned parties. Common themes among freethinking political parties are "freedom", "liberty", and "individualism".

Switzerland

Main article: Freethinkers Association of Switzerland

With the introduction of cantonal church taxes in the 1870s, anti-clericals began to organise themselves. Around 1870, a "freethinkers club" was founded in Zürich. During the debate on the Zürich church law in 1883, professor Friedrich Salomon Vögelin and city council member Kunz proposed to separate church and state.[30]

Turkey

In the last years of the Ottoman Empire, freethought made its voice heard by the works of distinguished people such as Ahmet Rıza, Tevfik Fikret, Abdullah Cevdet, Kılıçzade Hakkı, and Celal Nuri İleri. These intellectuals affected the early period of the Turkish Republic. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk –field marshal, revolutionary statesman, author, and founder of the secular Turkish nation state, serving as its first President from 1923 until his death in 1938– was the practitioner of their ideas. He made many reforms that modernized the country. Sources point out that Atatürk was a religious skeptic and a freethinker. He was a non-doctrinaire deist[31][32] or an atheist,[33][34][35] who was antireligious and anti-Islamic in general.[36][37] According to Atatürk, the Turkish people do not know what Islam really is and do not read the Quran. People are influenced by Arabic sentences that they do not understand, and because of their customs they go to mosques. When the Turks read the Quran and think about it, they will leave Islam.[38] Atatürk described Islam as the religion of the Arabs in his own work titled Vatandaş için Medeni Bilgiler by his own critical and nationalist views.[39]

Association of Atheism (Ateizm Derneği), the first official atheist organisation in Middle East and Caucasus, was founded in 2014.[40] It serves to support irreligious people and freethinkers in Turkey who are discriminated against based on their views. In 2018 it was reported in some media outlets that the Ateizm Derneği would close down because of the pressure on its members and attacks by pro-government media, but the association itself issued a clarification that this was not the case and that it was still active.[41]

United States

The Free Thought movement first organized itself in the United States as the "Free Press Association" in 1827 in defense of George Houston, publisher of The Correspondent, an early journal of Biblical criticism in an era when blasphemy convictions were still possible. Houston had helped found an Owenite community at Haverstraw, New York in 1826–27. The short-lived Correspondent was superseded by the Free Enquirer, the official organ of Robert Owen's New Harmony community in Indiana, edited by Robert Dale Owen and by Fanny Wright between 1828 and 1832 in New York. During this time Robert Dale Owen sought to introduce the philosophic skepticism of the Free Thought movement into the Workingmen's Party in New York City. The Free Enquirer's annual civic celebrations of Paine's birthday after 1825 finally coalesced in 1836 in the first national Free Thinkers organization, the "United States Moral and Philosophical Society for the General Diffusion of Useful Knowledge". It was founded on August 1, 1836, at a national convention at the Lyceum in Saratoga Springs with Isaac S. Smith of Buffalo, New York, as president. Smith was also the 1836 Equal Rights Party's candidate for Governor of New York and had also been the Workingmen's Party candidate for Lt. Governor of New York in 1830. The Moral and Philosophical Society published The Beacon, edited by Gilbert Vale.[42]

Robert G. Ingersoll[43]

Driven by the revolutions of 1848 in the German states, the 19th century saw an immigration of German freethinkers and anti-clericalists to the United States (see Forty-Eighters). In the United States, they hoped to be able to live by their principles, without interference from government and church authorities.[44]

Many Freethinkers settled in German immigrant strongholds, including St. Louis, Indianapolis, Wisconsin, and Texas, where they founded the town of Comfort, Texas, as well as others.[44]

These groups of German Freethinkers referred to their organizations as Freie Gemeinden, or "free congregations".[44] The first Freie Gemeinde was established in St. Louis in 1850.[45] Others followed in Pennsylvania, California, Washington, D.C., New York, Illinois, Wisconsin, Texas, and other states.[44][45]

Freethinkers tended to be liberal, espousing ideals such as racial, social, and sexual equality, and the abolition of slavery.[44]

The "Golden Age of Freethought" in the US came in the late 1800s. The dominant organization was the National Liberal League which formed in 1876 in Philadelphia. This group re-formed itself in 1885 as the American Secular Union under the leadership of the eminent agnostic orator Robert G. Ingersoll. Following Ingersoll's death in 1899 the organization declined, in part due to lack of effective leadership.[46]

Freethought in the United States declined in the early twentieth century. By the early twentieth century, most Freethought congregations had disbanded or joined other mainstream churches. The longest continuously operating Freethought congregation in America is the Free Congregation of Sauk County, Wisconsin, which was founded in 1852 and is still active as of 2020. It affiliated with the American Unitarian Association (now the Unitarian Universalist Association) in 1955.[47] D. M. Bennett was the founder and publisher of The Truth Seeker in 1873, a radical freethought and reform American periodical.

German Freethinker settlements were located in:

• Burlington, Racine County, Wisconsin[44]

• Belleville, St. Clair County, Illinois

• Castell, Llano County, Texas

• Comfort, Kendall County, Texas

• Davenport, Scott County, Iowa[48]

• Fond du Lac, Fond du Lac County, Wisconsin[44]

• Frelsburg, Colorado County, Texas

• Hermann, Gasconade County, Missouri

• Jefferson, Jefferson County, Wisconsin[44]

• Indianapolis, Indiana[49]

• Latium, Washington County, Texas

• Manitowoc, Manitowoc County, Wisconsin[44]

• Meyersville, DeWitt County, Texas

• Milwaukee, Wisconsin[44]

• Millheim, Austin County, Texas

• Oshkosh, Winnebago County, Wisconsin[44]

• Ratcliffe, DeWitt County, Texas

• Sauk City, Sauk County, Wisconsin[44][47]

• Shelby, Austin County, Texas

• Sisterdale, Kendall County, Texas

• St. Louis, Missouri

• Tusculum, Kendall County, Texas

• Two Rivers, Manitowoc County, Wisconsin[44]

• Watertown, Dodge County, Wisconsin[44]

Canada

In 1873 a handful of secularists founded the earliest known secular organization in English Canada, the Toronto Freethought Association. Reorganized in 1877 and again in 1881, when it was renamed the Toronto Secular Society, the group formed the nucleus of the Canadian Secular Union, established in 1884 to bring together freethinkers from across the country.[50]

A significant number of the early members appear to have come from the educated labour "aristocracy", including Alfred F. Jury, J. Ick Evans and J. I. Livingstone, all of whom were leading labour activists and secularists. The second president of the Toronto association, T. Phillips Thompson, became a central figure in the city's labour and social-reform movements during the 1880s and 1890s and arguably Canada's foremost late nineteenth-century labour intellectual. By the early 1880s scattered freethought organizations operated throughout southern Ontario and parts of Quebec, eliciting both urban and rural support.

The principal organ of the freethought movement in Canada was Secular Thought (Toronto, 1887–1911). Founded and edited during its first several years by English freethinker Charles Watts (1835–1906), it came under the editorship of Toronto printer and publisher James Spencer Ellis in 1891 when Watts returned to England. In 1968 the Humanist Association of Canada (HAC) formed to serve as an umbrella group for humanists, atheists, and freethinkers, and to champion social justice issues and oppose religious influence on public policy—most notably in the fight to make access to abortion free and legal in Canada.

Anarchism

In the United States of America,

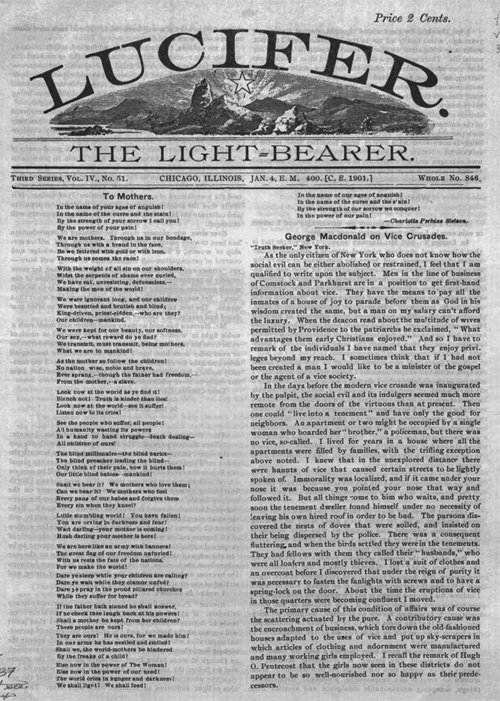

"freethought was a basically anti-Christian, anti-clerical movement, whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide for himself on religious matters. A number of contributors to Liberty were prominent figures in both freethought and anarchism. The individualist anarchist George MacDonald was a co-editor of Freethought and, for a time, The Truth Seeker. E.C. Walker was co-editor of the freethought/free love journal Lucifer, the Light-Bearer."[51]

"Many of the anarchists were ardent freethinkers; reprints from freethought papers such as Lucifer, the Light-Bearer, Freethought and The Truth Seeker appeared in Liberty...The church was viewed as a common ally of the state and as a repressive force in and of itself."[51]

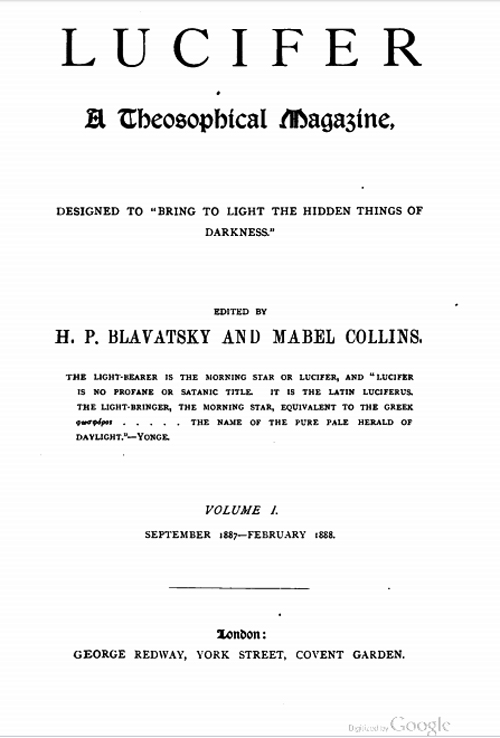

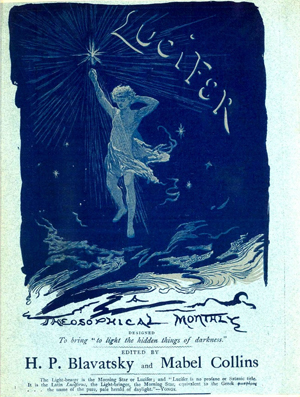

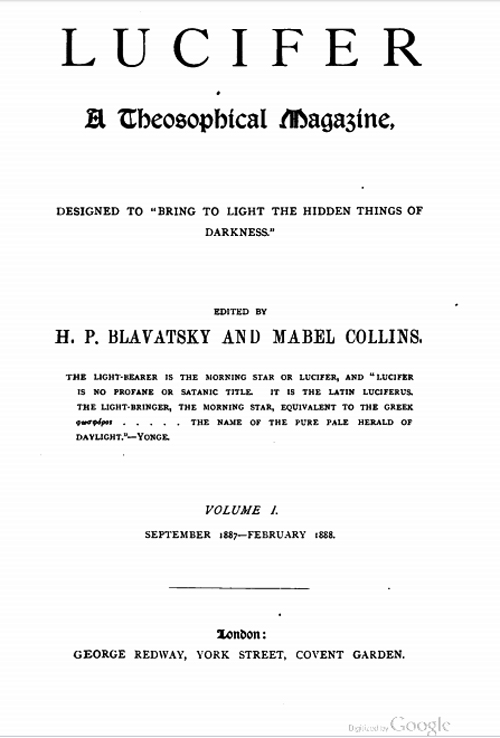

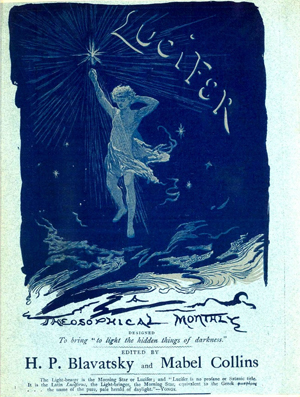

Lucifer was the title of a Theosophist journal published by Helena Blavatsky; the first issue appeared in London in September 1887.The Light-Bearer is the Morning Star or Lucifer, and "Lucifer is no profane or Satanic title. It is the Latin Luciferus, the Light-Bringer, the Morning Star, Equivalent to the Greek [x] ... The Name of the Pure Pale Herald of Daylight." -- Yonge

-- Lucifer: A Theosophical Magazine Designed to "Bring to Light the Hidden Things of Darkness"