Clement Attlee

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/27/20

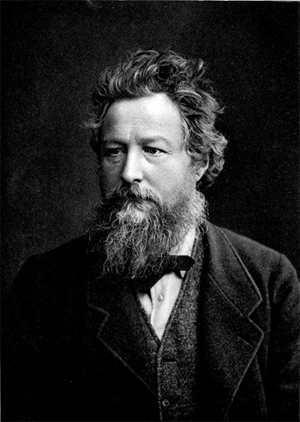

The Right Honourable The Earl Attlee KG OM CH PC FRS

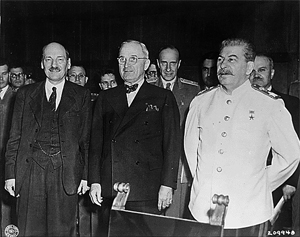

Attlee in 1945

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

In office: 26 July 1945 – 26 October 1951

Monarch: George VI

Deputy: Herbert Morrison

Preceded by: Winston Churchill

Succeeded by: Winston Churchill

Leader of the Opposition

In office: 26 October 1951 – 25 November 1955

Monarch: George VI; Elizabeth II

Prime Minister: Winston Churchill; Sir Anthony Eden

Preceded by: Winston Churchill

Succeeded by: Herbert Morrison

In office: 25 October 1935 – 11 May 1940

Monarch: George V; Edward VIII; George VI

Prime Minister: Stanley Baldwin; Neville Chamberlain

Preceded by: George Lansbury

Succeeded by: Hastings Lees-Smith

Leader of the Labour Party

In office: 25 October 1935 – 7 December 1955

Deputy: Arthur Greenwood; Herbert Morrison

Preceded by: George Lansbury

Succeeded by: Hugh Gaitskell

Deputy Leader of the Labour Party

In office: 25 October 1932 – 25 October 1935

Leader: George Lansbury

Preceded by: J. R. Clynes

Succeeded by: Arthur Greenwood

Wartime ministerial offices

Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

In office: 19 February 1942 – 23 May 1945

Prime Minister: Winston Churchill

Preceded by: Office created

Succeeded by: Herbert Morrison

Lord President of the Council

In office: 24 September 1943 – 23 May 1945

Prime Minister: Winston Churchill

Preceded by: Sir John Anderson

Succeeded by: The Lord Woolton

Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs

In office: 15 February 1942 – 24 September 1943

Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Preceded by: The Viscount Cranborne

Succeeded by: The Viscount Cranborne

Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

In office: 11 May 1940 – 15 February 1942

Prime Minister: Winston Churchill

Preceded by: Sir Kingsley Wood

Succeeded by: Sir Stafford Cripps

Interwar ministerial offices

Postmaster General

In office: 13 March 1931 – 25 August 1931

Prime Minister: Ramsay MacDonald

Preceded by: Hastings Lees-Smith

Succeeded by: William Ormsby-Gore

Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

In office: 23 May 1930 – 13 March 1931

Prime Minister: Ramsay MacDonald

Preceded by: Sir Oswald Mosley

Succeeded by: The Lord Ponsonby

Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for War

In office: 23 January 1924 – 4 November 1924

Prime Minister: Ramsay MacDonald

Preceded by: Wilfrid Ashley

Succeeded by: Richard Onslow

Parliamentary offices

Member of the House of Lords, Lord Temporal

In office: 16 December 1955 – 8 October 1967

Hereditary Peerage

Preceded by: Earldom created

Succeeded by: The 2nd Earl Attlee

Member of Parliament for Walthamstow West

In office: 23 February 1950 – 16 December 1955

Preceded by: Valentine McEntee

Succeeded by: Edward Redhead

Member of Parliament for Limehouse

In office: 15 November 1922 – 3 February 1950

Preceded by: Sir William Pearce

Succeeded by: Constituency abolished

Personal details

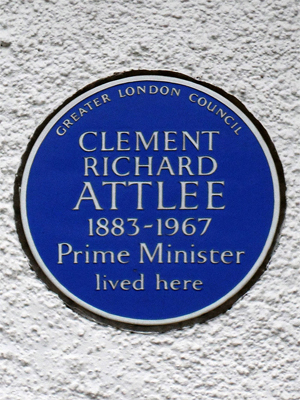

Born: Clement Richard Attlee, 3 January 1883, Putney, Surrey, England

Died: 8 October 1967 (aged 84), Westminster, London, England

Resting place: Westminster Abbey

Political party: Labour

Spouse(s): Violet Millar (m. 1922; died 1964)

Children: 4, including Martin Attlee, 2nd Earl Attlee

Alma mater: University College, Oxford; London School of Economics

Occupation: Lawyer politician soldier

Military service

Allegiance: United Kingdom

Branch/service: British Army

Years of service: 1914–1919

Rank: Major

Battles/wars: First World War; Gallipoli campaign; Mesopotamian campaign; Western Front

Awards: 1914–15 Star; British War Medal; Victory Medal

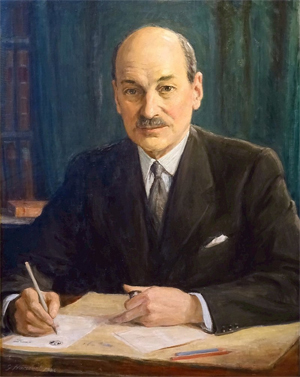

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS (3 January 1883 – 8 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was twice Leader of the Opposition (1935–1940, 1951–1955).

The son of a London solicitor, Attlee was born into a middle-class family. After attending private schools and the University of Oxford, he practised as a barrister. The volunteer work he carried out in London's East End exposed him to poverty and his political views shifted leftwards thereafter. He joined the Independent Labour Party, gave up his legal career, and began lecturing at the London School of Economics. His work was interrupted by service as an officer in the First World War. In 1919, he became mayor of Stepney and in 1922 was elected Member of Parliament for Limehouse. Attlee served in the first Labour minority government led by Ramsay MacDonald in 1924, and then joined the Cabinet during MacDonald's second minority (1929–1931). After retaining his seat in Labour's landslide defeat of 1931, he became the party's Deputy Leader. Elected Leader of the Labour Party in 1935, and at first advocating pacificism and opposing re-armament, he became a critic of Neville Chamberlain's appeasement of Hitler and Mussolini in the lead-up to the Second World War. Attlee took Labour into the wartime coalition government in 1940 and served under Winston Churchill, initially as Lord Privy Seal and then as Deputy Prime Minister from 1942.[note 1]

After the end of the war, the coalition was dissolved and Attlee led Labour to a landslide victory at the 1945 general election,[note 2] forming the first Labour majority government. His government's Keynesian approach to economic management aimed to maintain full employment, a mixed economy and a greatly enlarged system of social services provided by the state. To this end, it undertook the nationalisation of public utilities and major industries, and implemented wide-ranging social reforms, including the passing of the National Insurance Act 1946 and National Assistance Act, the foundation of the National Health Service (1948) and the enlargement of public subsidies for council house building. His government also reformed trade union legislation, working practices and children's services; it created the National Parks system, passed the New Towns Act 1946 and established the town and country planning system.

In foreign policy, Attlee delegated to Ernest Bevin, but oversaw the partition of India (1947), the independence of Burma and Ceylon, and the dissolution of the British mandates of Palestine and Transjordan. He and Bevin encouraged the United States to take a vigorous role in the Cold War; unable to afford military intervention in Greece, he called on Washington to counter Communists there, establishing the Truman Doctrine.[1] He supported the Marshall Plan to rebuild Western Europe with American money and, in 1949, promoted the NATO military alliance against the Soviet bloc. After leading Labour to a narrow victory at the 1950 general election, he sent British troops to fight in the Korean War.[note 3]

Attlee had inherited a country close to bankruptcy after the Second World War and beset by food, housing and resource shortages; despite his social reforms and economic programme, these problems persisted throughout his premiership, alongside recurrent currency crises and dependence on US aid. His party was narrowly defeated by the Conservatives in the 1951 general election, despite winning the most votes. He continued as Labour leader but retired after losing the 1955 election and was elevated to the House of Lords; after a long retirement, he died in 1967. In public, he was modest and unassuming, but behind the scenes his depth of knowledge, quiet demeanour, objectivity and pragmatism proved decisive. Often rated as one of the greatest British prime ministers, Attlee's reputation among scholars has grown, thanks to his creation of the modern welfare state and involvement in building the coalition against Stalin in the Cold War. He remains the longest-serving Labour leader in British history.

Early life and education

Attlee was born on 3 January 1883 in Putney, Surrey (now part of London), into a middle-class family, the seventh of eight children. His father was Henry Attlee (1841–1908), a solicitor, and his mother was Ellen Bravery Watson (1847–1920), daughter of Thomas Simons Watson, secretary for the Art Union of London.[2] He was educated at Northaw School, a boys' preparatory school near Pluckley in Kent; Haileybury College; and University College, Oxford, where in 1904 he graduated as a Bachelor of Arts with second-class honours in modern history.

Attlee then trained as a barrister at the Inner Temple and was called to the bar in March 1906. He worked for a time at his father's law firm Druces and Attlee but did not enjoy the work, and had no particular ambition to succeed in the legal profession.[3] He also played football for non-League club Fleet.[4]

Early career

In 1906, he became a volunteer at Haileybury House, a charitable club for working-class boys in Stepney in the East End of London run by his old school, and from 1907 to 1909 he served as the club's manager. Until then, his political views had been more conservative. However, after his shock at the poverty and deprivation he saw while working with the slum children, he came to the view that private charity would never be sufficient to alleviate poverty and that only direct action and income redistribution by the state would have any serious effect. This sparked a process that caused him to convert to socialism. He subsequently joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1908 and became active in local politics. In 1909, he stood unsuccessfully at his first election, as an ILP candidate for Stepney Borough Council.[5]

He also worked briefly as a secretary for Beatrice Webb in 1909, before becoming a secretary for Toynbee Hall. In 1911, he was employed by the UK Government as an "official explainer"—touring the country to explain Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George's National Insurance Act. He spent the summer of that year touring Essex and Somerset on a bicycle, explaining the act at public meetings. A year later, he became a lecturer at the London School of Economics.[6]

Military service during the First World War

Following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Attlee applied to join the British Army. Initially his application was turned down, as at the age of 31 he was seen as being too old; however, he was finally allowed to join in September, and was commissioned[7] in the rank of Captain with the 6th (Service) Battalion, South Lancashire Regiment, part of the 38th Brigade of the 13th (Western) Division, and was sent to fight in the Gallipoli Campaign in Turkey. His decision to fight caused a rift between him and his older brother Tom, who, as a conscientious objector, spent much of the war in prison.[8]

After a period fighting in Gallipoli, he collapsed after falling ill with dysentery and was put on a ship bound for England to recover. When he woke up he wanted to get back to action as soon as possible, and asked to be let off the ship in Malta where he stayed in hospital to recover. His hospitalisation coincided with the Battle of Sari Bair, which saw a large number of his comrades killed. Upon returning to action, he was informed that his company had been chosen to hold the final lines during the evacuation of Suvla. As such, he was the penultimate man to be evacuated from Suvla Bay, the last being General Stanley Maude.[9]

Attlee (seen in the centre) in 1916, aged 33, whilst serving in Mesopotamia.

The Gallipoli Campaign had been engineered by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. Although it was unsuccessful, Attlee believed that it was a bold strategy, which could have been a success if it had been better implemented on the ground. This gave him an admiration for Churchill as a military strategist, which would make their working relationship in later years productive.[10]

He later served in the Mesopotamian Campaign in what is now Iraq, where in April 1916 he was badly wounded, being hit in the leg by shrapnel while storming an enemy trench during the Battle of Hanna. He was sent firstly to India, and then back to the UK to recover. In February 1917, he was promoted to the rank of Major,[11] leading him to be known as "Major Attlee" for much of the inter-war period. He would spend most of 1917 training soldiers at various locations in England.[12] From 2 to 9 July 1917, he was the temporary commanding officer (CO) of the newly formed L (later 10th) Battalion, the Tank Corps at Bovington Camp, Dorset. From 9 July, he assumed command of 30th Company of the same battalion; however, he did not deploy to France with it in December 1917.[13]

After fully recovering from his injuries, he was sent to France in June 1918 to serve on the Western Front for the final months of the war. After being discharged from the Army in January 1919, he returned to Stepney, and returned to his old job lecturing part-time at the London School of Economics.[14]

Marriage and children

Attlee met Violet Millar while on a long trip with friends to Italy in 1921. They fell in love[15] and were soon engaged, marrying at Christ Church, Hampstead, on 10 January 1922. It would come to be a devoted marriage, with Attlee providing protection and Violet providing a home that was an escape for Attlee from political turmoil. She died in 1964.[16] They had four children:

• Lady Janet Helen (1923–2019),[17] she married the scientist Harold Shipton (1920–2007)[18] at Ellesborough Parish Church in 1947.[19]

• Lady Felicity Ann (1925–2007), married the business executive John Keith Harwood (d. 1989) at Little Hampden in 1955[20][21]

• Martin Richard, Viscount Prestwood, later 2nd Earl Attlee (1927–1991)

• Lady Alison Elizabeth (1930–2016),[22] married Richard Davis at Great Missenden in 1952.[23]

Early political career

Local politics

Attlee returned to local politics in the immediate post-war period, becoming mayor of the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney, one of London's most deprived inner-city boroughs, in 1919. During his time as mayor, the council undertook action to tackle slum landlords who charged high rents but refused to spend money on keeping their property in habitable condition. The council served and enforced legal orders on homeowners to repair their property. It also appointed health visitors and sanitary inspectors, reducing the infant mortality rate, and took action to find work for returning unemployed ex-servicemen.[24]

In 1920, while mayor, he wrote his first book, The Social Worker, which set out many of the principles that informed his political philosophy and that were to underpin the actions of his government in later years. The book attacked the idea that looking after the poor could be left to voluntary action. He wrote on page 30:

In a civilised community, although it may be composed of self-reliant individuals, there will be some persons who will be unable at some period of their lives to look after themselves, and the question of what is to happen to them may be solved in three ways – they may be neglected, they may be cared for by the organised community as of right, or they may be left to the goodwill of individuals in the community.[25]

and went on to say at page 75:

Charity is only possible without loss of dignity between equals. A right established by law, such as that to an old age pension, is less galling than an allowance made by a rich man to a poor one, dependent on his view of the recipient's character, and terminable at his caprice.[26]

In 1921, George Lansbury, the Labour mayor of the neighbouring borough of Poplar, and future Labour Party leader, launched the Poplar Rates Rebellion; a campaign of disobedience seeking to equalise the poor relief burden across all the London boroughs. Attlee, who was a personal friend of Lansbury, strongly supported this. However, Herbert Morrison, the Labour mayor of nearby Hackney, and one of the main figures in the London Labour Party, strongly denounced Lansbury and the rebellion. During this period, Attlee developed a lifelong dislike of Morrison.[27][28][29]

Member of Parliament

At the 1922 general election, Attlee became the Member of Parliament (MP) for the constituency of Limehouse in Stepney. At the time, he admired Ramsay MacDonald and helped him get elected as Labour Party leader at the 1922 leadership election. He served as MacDonald's Parliamentary Private Secretary for the brief 1922 parliament. His first taste of ministerial office came in 1924, when he served as Under-Secretary of State for War in the short-lived first Labour government, led by MacDonald.[30]

Attlee opposed the 1926 General Strike, believing that strike action should not be used as a political weapon. However, when it happened, he did not attempt to undermine it. At the time of the strike, he was chairman of the Stepney Borough Electricity Committee. He negotiated a deal with the Electrical Trade Union so that they would continue to supply power to hospitals, but would end supplies to factories. One firm, Scammell and Nephew Ltd, took a civil action against Attlee and the other Labour members of the committee (although not against the Conservative members who had also supported this). The court found against Attlee and his fellow councillors and they were ordered to pay £300 damages. The decision was later reversed on appeal, but the financial problems caused by the episode almost forced Attlee out of politics.[31]

In 1927, he was appointed a member of the multi-party Simon Commission, a royal commission set up to examine the possibility of granting self-rule to India. Due to the time he needed to devote to the commission, and contrary to a promise MacDonald made to Attlee to induce him to serve on the commission, he was not initially offered a ministerial post in the Second Labour Government, which entered office after the 1929 general election.[32] Attlee's service on the Commission equipped him with a thorough exposure to India and many of its political leaders. By 1933 he argued that British rule was alien to India and was unable to make the social and economic reforms necessary for India's progress. He became the British leader most sympathetic to Indian independence (as a dominion), preparing him for his role in deciding on independence in 1947.[33]

In May 1930, Labour MP Oswald Mosley left the party after its rejection of his proposals for solving the unemployment problem, and Attlee was given Mosley's post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. In March 1931, he became Postmaster General, a post he held for five months until August, when the Labour government fell, after failing to agree on how to tackle the financial crisis of the Great Depression.[34] That month MacDonald and a few of his allies formed a National Government with the Conservatives and Liberals, leading them to be expelled from Labour. MacDonald offered Attlee a job in the National Government, but he turned down the offer and opted to stay loyal to the main Labour party.[35]

After Ramsay MacDonald formed the National Government, Labour was deeply divided. Attlee had long been close to MacDonald and now felt betrayed—as did most Labour politicians. During the course of the second Labour government, Attlee had become increasingly disillusioned with MacDonald, whom he came to regard as vain and incompetent, and of whom he later wrote scathingly in his autobiography. He would write:[36]

In the old days I had looked up to MacDonald as a great leader. He had a fine presence and great oratorical power. The unpopular line which he took during the First World War seemed to mark him as a man of character. Despite his mishandling of the Red Letter episode, I had not appreciated his defects until he took office a second time. I then realised his reluctance to take positive action and noted with dismay his increasing vanity and snobbery, while his habit of telling me, a junior Minister, the poor opinion he had of all his Cabinet colleagues made an unpleasant impression. I had not, however, expected that he would perpetrate the greatest betrayal in the political history of this country... The shock to the Party was very great, especially to the loyal workers of the rank-and-file who had made great sacrifices for these men.

1930s opposition

Deputy Leader

The 1931 general election held later that year was a disaster for the Labour Party, which lost over 200 seats, returning only 52 MPs to Parliament. The vast majority of the party's senior figures, including the Leader Arthur Henderson, lost their seats. Attlee, however, narrowly retained his Limehouse seat, with his majority being slashed from 7,288 to just 551. He was one of only three Labour MPs who had experience of government to retain their seats, along with George Lansbury and Stafford Cripps. Accordingly Lansbury was elected Leader unopposed with Attlee as his deputy.[37]

Most of the remaining Labour MPs after 1931 were elderly trade union officials who could not contribute much to debates, Lansbury was in his 70s, and Stafford Cripps another main figure of the Labour front bench who had entered Parliament in 1931, was inexperienced. As one of the most capable and experienced of the remaining Labour MPs, Attlee therefore shouldered a lot of the burden of providing an opposition to the National Government in the years 1931–35, during this time he had to extend his knowledge of subjects which he had not studied in any depth before, such as finance and foreign affairs in order to provide an effective opposition to the government.[38]

Attlee effectively served as acting leader for nine months from December 1933, after Lansbury fractured his thigh in an accident, which raised Attlee's public profile considerably. It was during this period, however, that personal financial problems almost forced Attlee to quit politics altogether. His wife had become ill, and at that time there was no separate salary for the Leader of the Opposition. On the verge of resigning from Parliament, he was persuaded to stay by Stafford Cripps, a wealthy socialist, who agreed to make a donation to party funds to pay him an additional salary until Lansbury could take over again.[39]

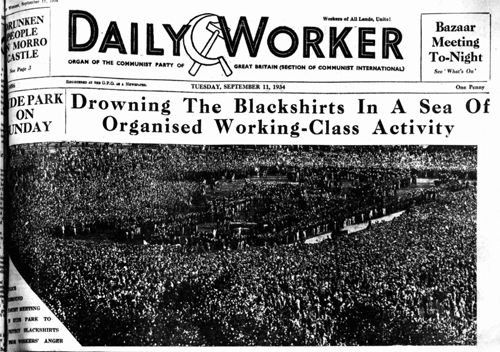

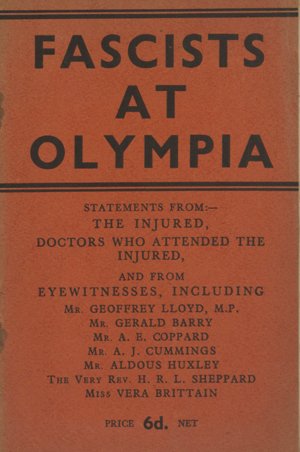

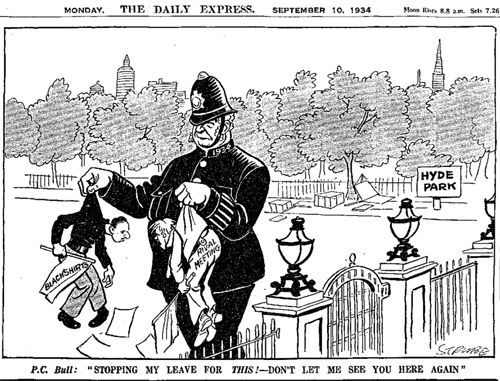

During 1932–33 Attlee flirted with, and then drew back from radicalism, influenced by Stafford Cripps who was then on the radical wing of the party, he was briefly a member of the Socialist League, which had been formed by former Independent Labour Party (ILP) members, who opposed the ILP's disaffiliation from the main Labour Party in 1932. At one point he agreed with the proposition put forward by Cripps that gradual reform was inadequate and that a socialist government would have to pass an emergency powers act, allowing it to rule by decree to overcome any opposition by vested interests until it was safe to restore democracy. He admired Oliver Cromwell's strong-armed rule and use of major generals to control England. After looking more closely at Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin, and even his former colleague Oswald Mosley, leader of the new blackshirt fascist movement in Britain, Attlee retreated from his radicalism, and distanced himself from the League, and argued instead that the Labour Party must adhere to constitutional methods and stand forthright for democracy and against totalitarianism of either the left or right. He always supported the crown, and as Prime Minister was close to King George VI.[40][41]

Leader of the Opposition

George Lansbury, a committed pacifist, resigned as the Leader of the Labour Party at the 1935 Party Conference on 8 October, after delegates voted in favour of sanctions against Italy for its aggression against Abyssinia. Lansbury had strongly opposed the policy, and felt unable to continue leading the party. Taking advantage of the disarray in the Labour Party, the Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin announced on 19 October that a general election would be held on 14 November. With no time for a leadership contest, the party agreed that Attlee should serve as interim leader, on the understanding that a leadership election would be held after the general election.[42] Attlee therefore led Labour through the 1935 election, which saw the party stage a partial comeback from its disastrous 1931 performance, winning 38 per cent of the vote, the highest share Labour had won up to that point, and gaining over one hundred seats.[43]

Attlee stood in the subsequent leadership election, held soon after, where he was opposed by Herbert Morrison, who had just re-entered parliament in the recent election, and Arthur Greenwood: Morrison was seen as the favourite, but was distrusted by many sections of the party, especially the left-wing. Arthur Greenwood meanwhile was a popular figure in the party; however, his leadership bid was severely hampered by his alcohol problem. Attlee was able to come across as a competent and unifying figure, particularly having already led the party through a general election. He went on to come first in both the first and second ballots, formally being elected Leader of the Labour Party on 3 December 1935.[44]

Throughout the 1920s and most of the 1930s, the Labour Party's official policy had been to oppose rearmament, instead supporting internationalism and collective security under the League of Nations.[45] At the 1934 Labour Party Conference, Attlee declared that, "We have absolutely abandoned any idea of nationalist loyalty. We are deliberately putting a world order before our loyalty to our own country. We say we want to see put on the statute book something which will make our people citizens of the world before they are citizens of this country".[46] During a debate on defence in Commons a year later, Attlee said "We are told (in the White Paper) that there is danger against which we have to guard ourselves. We do not think you can do it by national defence. We think you can only do it by moving forward to a new world. A world of law, the abolition of national armaments with a world force and a world economic system. I shall be told that that is quite impossible".[47] Shortly after those comments, Adolf Hitler proclaimed that German rearmament offered no threat to world peace. Attlee responded the next day noting that Hitler's speech, although containing unfavourable references to the Soviet Union, created "A chance to call a halt in the armaments race...We do not think that our answer to Herr Hitler should be just rearmament. We are in an age of rearmaments, but we on this side cannot accept that position".[48]

In April 1936, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Neville Chamberlain, introduced a Budget which increased the amount spent on the armed forces. Attlee made a radio broadcast in opposition to it, saying:

[The budget] was the natural expression of the character of the present Government. There was hardly any increase allowed for the services which went to build up the life of the people, education and health. Everything was devoted to piling up the instruments of death. The Chancellor expressed great regret that he should have to spend so much on armaments, but said that it was absolutely necessary and was due only to the actions of other nations. One would think to listen to him that the Government had no responsibility for the state of world affairs. [...] The Government has now resolved to enter upon an arms race, and the people will have to pay for their mistake in believing that it could be trusted to carry out a policy of peace. [...] This is a War Budget. We can look in the future for no advance in Social Legislation. All available resources are to be devoted to armaments.[49]

In June 1936, the Conservative MP Duff Cooper called for an Anglo-French alliance against possible German aggression and called for all parties to support one. Attlee condemned this: "We say that any suggestion of an alliance of this kind—an alliance in which one country is bound to another, right or wrong, by some overwhelming necessity—is contrary to the spirit of the League of Nations, is contrary to the Covenant, is contrary to Locarno is contrary to the obligations which this country has undertaken, and is contrary to the professed policy of this Government".[50] At the Labour Party conference at Edinburgh in October Attlee reiterated that "There can be no question of our supporting the Government in its rearmament policy".[51]

However, with the rising threat from Nazi Germany, and the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations, this policy eventually lost credibility. By 1937, Labour had jettisoned its pacifist position and came to support rearmament and oppose Neville Chamberlain's policy of appeasement.[52]

In 1938, Attlee opposed the Munich Agreement, in which Chamberlain negotiated with Hitler to give Germany the German-speaking parts of Czechoslovakia, the Sudetenland:

We all feel relief that war has not come this time. Every one of us has been passing through days of anxiety; we cannot, however, feel that peace has been established, but that we have nothing but an armistice in a state of war. We have been unable to go in for care-free rejoicing. We have felt that we are in the midst of a tragedy. We have felt humiliation. This has not been a victory for reason and humanity. It has been a victory for brute force. At every stage of the proceedings there have been time limits laid down by the owner and ruler of armed force. The terms have not been terms negotiated; they have been terms laid down as ultimata. We have seen to-day a gallant, civilised and democratic people betrayed and handed over to a ruthless despotism. We have seen something more. We have seen the cause of democracy, which is, in our view, the cause of civilisation and humanity, receive a terrible defeat. ... The events of these last few days constitute one of the greatest diplomatic defeats that this country and France have ever sustained. There can be no doubt that it is a tremendous victory for Herr Hitler. Without firing a shot, by the mere display of military force, he has achieved a dominating position in Europe which Germany failed to win after four years of war. He has overturned the balance of power in Europe. He has destroyed the last fortress of democracy in Eastern Europe which stood in the way of his ambition. He has opened his way to the food, the oil and the resources which he requires in order to consolidate his military power, and he has successfully defeated and reduced to impotence the forces that might have stood against the rule of violence.[53]

At the end of 1937, Attlee and a party of three Labour MPs visited Spain and visited the British Battalion of the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War. One of the companies was named the "Major Attlee Company" in his honour.[54]

In 1937, Attlee wrote a book entitled The Labour Party in Perspective that sold fairly well in which he set out some of his views. He argued that there was no point in Labour compromising on its socialist principles in the belief that this would achieve electoral success. He wrote: "I find that the proposition often reduces itself to this – that if the Labour Party would drop its socialism and adopt a Liberal platform, many Liberals would be pleased to support it. I have heard it said more than once that if Labour would only drop its policy of nationalisation everyone would be pleased, and it would soon obtain a majority. I am convinced it would be fatal for the Labour Party." He also wrote that there was no point in "watering down Labour's socialist creed in order to attract new adherents who cannot accept the full socialist faith. On the contrary, I believe that it is only a clear and bold policy that will attract this support".[55]

In the late 1930s, Attlee sponsored a Jewish mother and her two children, enabling them to leave Germany in 1939 and move to the UK. On arriving in Britain, Attlee invited one of the children into his home in Stanmore, north-west London, where he stayed for several months.[56]

Deputy Prime Minister

Attlee as Lord Privy Seal, visiting a munitions factory in 1941

Attlee remained as Leader of the Opposition when the Second World War broke out in September 1939. The ensuing disastrous Norwegian Campaign would result in a motion of no confidence in Neville Chamberlain.[57] Although Chamberlain survived this, the reputation of his administration was so badly and publicly damaged that it became clear a coalition government would be necessary. Even if Attlee had personally been prepared to serve under Chamberlain in an emergency coalition government, he would never have been able to carry Labour with him. Consequently, Chamberlain tendered his resignation, and Labour and the Conservatives entered a coalition government led by Winston Churchill on 10 May 1940.[28]

Attlee and Churchill quickly agreed that the War Cabinet would consist of three Conservatives (initially Churchill, Chamberlain and Lord Halifax) and two Labour members (initially himself and Arthur Greenwood) and that Labour should have slightly more than one third of the posts in the coalition government.[58] Attlee and Greenwood played a vital role in supporting Churchill during a series of War Cabinet debates over whether or not to negotiate peace terms with Hitler following the Fall of France in May 1940; both supported Churchill and gave him the majority he needed in the War Cabinet to continue Britain's resistance.[59][60]

Only Attlee and Churchill remained in the War Cabinet from the formation of the Government of National Unity in May 1940 through to the election in May 1945. Attlee was initially the Lord Privy Seal, before becoming Britain's first ever Deputy Prime Minister in 1942, as well as becoming the Dominions Secretary and the Lord President of the Council.[28][60]

Attlee himself played a generally low key but vital role in the wartime government, working behind the scenes and in committees to ensure the smooth operation of government. In the coalition government, three inter-connected committees effectively ran the country. Churchill chaired the first two, the War Cabinet and the Defence Committee, with Attlee deputising for him in these, and answering for the government in Parliament when Churchill was absent. Attlee himself instituted, and later chaired the third body, the Lord President's Committee, which was responsible for overseeing domestic affairs. As Churchill was most concerned with overseeing the war effort, this arrangement suited both men. Attlee himself had largely been responsible for creating these arrangements with Churchill's backing, streamlining the machinery of government and abolishing many committees. He also acted as a concilliator in the government, smoothing over tensions which frequently arose between Labour and Conservative Ministers.[61][28][62]

Many Labour activists were baffled by the top leadership role for a man they regarded as having little charisma; Beatrice Webb wrote in her diary in early 1940:

He looked and spoke like an insignificant elderly clerk, without distinction in the voice, manner or substance of his discourse. To realise that this little nonentity is the Parliamentary Leader of the Labour Party... and presumably the future P.M. [Prime Minister] is pitiable".[63]

Prime Minister

Further information: Attlee ministry

See also: History of the United Kingdom (1945–present)

Attlee meeting King George VI after Labour's 1945 election victory