by Matthew Clark

Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online

2018

-- Dashanami Sampradaya [Order of Swamis] [Naga Sadhus akharas], by Wikipedia

-- The Fighting Ascetics of India, by J.N. Farquhar, M.A., D. Litt. (Oxon.).

-- Akhāṛās: Warrior Ascetics, by Matthew Clark

-- Sankara-Dig-vijaya: The Traditional Life of Sri Sankaracharya, by Madhava-Vidyaranya, Translated by Swami Tapasyananda

The Hindi term akhāṛā means “wrestling arena,” from which akhāṛiyā derives, meaning “master fighter,” “skilled manoevrer,” or “strategist.” There is a network of akhāṛās throughout India, particularly in the north, where men train in wrestling and other methods of fighting. Akhāṛās specialize in various techniques of fitness and combat, which include the use of weights, clubs, and maces. The akhāṛās have a resident guru. The wrestlers’ patron deity is → Hanumān. This network of akhāṛās, which serves local men who typically train before or after work, is distinct from another network of akhāṛās pertaining to groups of (formerly) militant ascetics with particular religious and sectarian identities.

That religious ascetics would be inducted into fighting regiments is neither necessarily perverse – in the context of the history of traditional Hinduism – nor necessarily a radical break from a previous mode of life. There is an obvious similarity in the lifestyles of both soldiers and ascetics: both require rigorous self-discipline, enduring the hardships of lengthy travel and extended periods of camping; subsistence, sometimes, on meager rations; being subservient to a commander or guru; and enduring extended (or permanent) celibacy. In medieval India, asceticism, trade, and war were not incompatible.

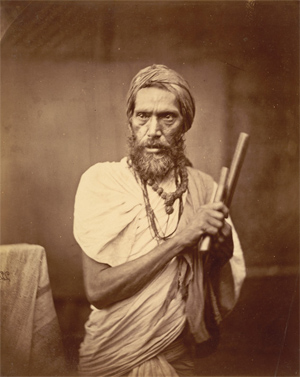

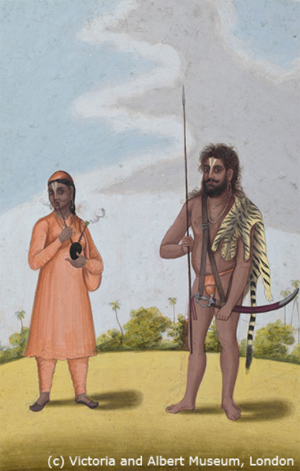

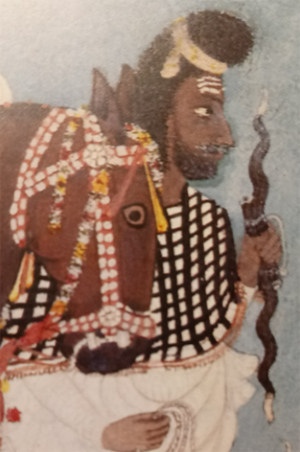

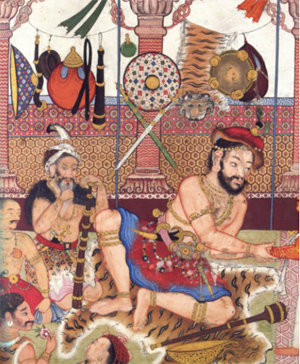

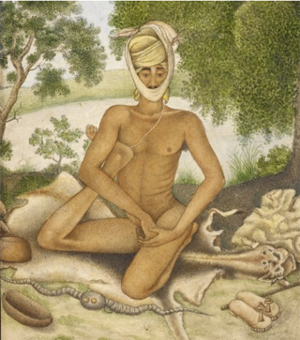

Fighting ascetics are usually referred to as nāgās (deriving from the Hindi term naṅgā, “naked”). Nāgās are usually almost naked, except for a loincloth (laṅgoṭī/kaupīn), and besmear their bodies with ash known as bhasm or vibhūti (“supernatural powers,” “dignity”), the most sacred (or pure) form of which is made from the product of burnt and filtered cow dung. They keep a sacred fire (dhūnī), and some have experience of training in fighting and the use of basic weaponry, particularly the sword, mace, and dagger. Some members (particularly nāgās) of some akhāṛās smoke a great quantity of gāñjā (the buds of female cannabis plants) and caras (cannabis resin), mostly in chillums (Hind. cilam, clay pipe), and may also regularly eat bhāṅg (prepared cannabis leaves; see also → intoxicants). While some nāgās keep their hair short, many wear jaṭā (dreadlocks). In terms of appearance and lifestyle, nāgās are in many respects indistinguishable from South Asian Sufi faqīrs (Arab.; Hind. fakīr). Some nāgās practice rigorous austerities, such as maintaining an arm aloft (ūrdhvabāhu) or remaining standing (khaṛeśvarī) for many years (see also → sādhus); some practice yoga exercises.

Origins of the Akhāṛās

One of the earliest available (semihistorical) references to militant (or armed) ascetics (or yogīs) in the Indic world is in Bāṇabhatṭạ’s 7th-century romance Harṣacarita based on the life of King Harsạ, who ruled (606–648 CE) North India from Kanauj and Thanesar (Sthāṇvīśvara), near Kurukshetra (150 km northwest of Delhi). In the Harṣacarita appear two ascetics (Pātālasvāmin and Karṇatāla) who eventually become employed as personal guards to King Pusp̣abhūti, “elevated to a fortune beyond their wildest dreams . . . occupying the front rank in battle” (HCar. 3.130). In the Bṛhatkathāślokasaṃgraha (8th–10th cents.), there is a reference (18.202–207) to “mendicant mercenaries with strange weapons” who are described as shaven-headed → Pāśupatas who are protecting trade. There are a couple of references (see Sanderson, 2009, 261–262n616) in the Mayasaṃgraha (5.182) and the Piṅgalāmata (10.28–31), from the 9th to 12th centuries, to Śaiva maṭhas (monasteries) containing armories for the storage of weapons of war. In a frequently cited reference to fighting ascetics in the mid-16th-century Bījak of → Kabīr (Ramainī 69), scorn is poured on yogīs, siddhas (another name for yogīs), mahants (chiefs/superiors), and ascetics who resort to arms, keep women, and collect property and taxes. An entourage of (perhaps) three thousand, which included armed yogīs in service to a yogī king in conflict with a ruler in Gujarat, is described by Ludovico di Varthema of Bologna the early 16th century (see Winter Jones, 1863, 111–112) in what may be the first account by a European of a contingent of armed ascetics.

Another incident often referred to in accounts of the early history of akhāṛās is of a conflict reported at Thanesar. In 1567 the Mughal emperor Akbar (1542–1605) watched a battle between two groups of ascetics who had become disputatious concerning the right to collect alms from pilgrims who had gathered at an annual pilgrimage to Thanesar. The two groups, who numbered around three hundred and five hundred, are referred to, respectively, as “Purī” and “Kur” (or Gur) saṃnyāsīs by Abu al-Fazl, one of the court biographers of Akbar. The “Gurs” were in all probability “Giris” (Purī and Giri are two of the ten names of saṃnyāsīs: see below). The fighting ascetics were armed with stones, swords, and cakras (metal wheels that may be hurled at opponents). Akbar instructed his troops to assist the Purīs, who were the faction weaker in number, resulting in their victory. About a score of the combatants died.

The Sang-joe is also a great occasion of alms and charity, and the priests, especially the acolytes and disciples, go round at dawn to collect alms in the temple when the service is concluded. The people being more generously disposed at this season than at other times give quite liberally. I am sorry to say that this pious inclination on the part of the people is often abused by mischievous priests, who do not scruple to go, in violation of the rules, on a second or even third or fourth round of begging at one time. I was astonished to hear that the priests who are on duty to prevent such irregular practices are in many cases the very instigators, abetting the younger disciples in committing them. The ill-gotten proceeds go into the pockets of those unscrupulous ‘inspectors’ who, urged on by greed, even go to the extreme of thrashing the young disciples when they refuse to go on fraudulent errands of this particular description. Now and then the erratic doings of these lads come to the ears of the higher authorities, who summon them and inflict upon them a severe reprimand, together with the more smarting punishment of a flogging. The incorrigible disciples are not disconcerted in the least, being conscious that they have their protectors in the official inspectors, and of course they are immune from expulsion from the monastery.

These mischievous young people are in most cases warrior-priests. These warrior-priests, of whom an account has already been given, are easily distinguished from the rest by their peculiar appearance and especially by their way of dressing the hair. Sometimes their heads are shaved bald, but more often they leave ringlets at each temple, and consider that these locks of four or five inches long give them a smart appearance. This manner of hair-dressing is not approved by the Lama authorities, and when they take notice of the locks they ruthlessly pull them off, leaving the temples swollen and bloody. Painful as this treatment is, the warriors rather glory in it, and swagger about the streets to display the marks of their courage. They are, however, cautious to conceal their ‘smart’ hair-dressing from the notice of the authorities, so that when they present themselves in the monastery they either tuck their ringlets behind the ears or besmear their faces with lamp-black compounded with butter. When at first I saw such blackened faces I wondered what the blackening meant, but afterwards I was informed of the reason of the strange phenomenon and my wonder disappeared as I became accustomed to the sight.

I am sorry to say that the warrior-priests are not merely offensive in appearance; they are generally also guilty of far more grave offences, and the nights of the holy service are abused as occasions for indulging in fearful malpractices. They really seem to be the descendants of the men of Sodom and Gomorrah mentioned in the bible.

They are often quite particular in small affairs. They are afraid of killing tiny insects, are strict in not stepping over broken tiles of a monastery when they find them on the road, but walk round them to the right, and never to the left. And yet they, and even their superiors, commit grave sin without much remorse. Really they are straining at gnats and swallowing camels.

-- The Festival of Lights, Excerpt from Three Years in Tibet, by Ekai Kawaguchi

Some commentators follow J.N. Farquhar (1925), who reported, based on anecdotes, that Madhusūdanasarasvatī (1540–1647), the well-known → Vedānta philosopher, approached Akbar to seek advice on the protection of an order (to which he belonged) from harassment by armed Muslim faqīrs (notwithstanding the unreliability of this account, Madhusūdanasarasvatī did have a connection to Akbar’s court). According to J.N. Farquhar, Madhusūdanasarasvatī was advised by Rājā Birbal to initiate a large number of non-Brahmans into a militant order. Thus were many Ksạtriyas, Vaiśyas, and, says J.N. Farquhar, “multitudes of Śūdras at a later date” admitted into the order. It is said that half of the Bhāratīs (see below) refused to accept this and went to Sringeri to remain “pure.” The recruitment of nāgās into organized fighting units appears to have occurred around the time of Akbar’s reign, although it is unlikely to have been in response to attacks by Sufis. Nearly all of the recorded conflicts between bands of ascetics have been between factions of Hindus, in most instances between Vaisṇạva → Rāmānandī vairāgīs/bairāgī and Śaiva → Daśanāmī saṃnyāsīs (also known as gosāīṃs) at melās (festivals) over bathing priorities for particular akhāṛās. The Rāmānandīs and the Daśanāmīs are the largest of the 60 or so extant sādhu sects in India and Nepal, and also those with the greatest number of nāgās.

The evidence indicates that organized nāgā military activity originally flourished under state patronage. During the latter half of the 16th century and the early part of the 17th century, a number of bands of fighting ascetics formed into akhāṛās with sectarian names and identities. These armies were of mercenaries who often largely disbanded during cessations of conflict and during harvest times, when many of the men would return home to attend to agricultural duties. The formation of mercenary nāgā armies occurred largely in parallel with the constitution of a formal and distinct identity for many of the currently recognizable sects of sādhus, including the Rāmānandīs and Daśanāmīs. Several commentators (e.g. Orr, 1940) have maintained that members of the Nāth sect (→ Nāth Sampradāya) have at times constituted elements of nāgā armies, but there seems to be no substantial evidence to support this assertion. It is most likely that observers mistakenly identified either Rāmānandīs or Daśanāmīs as Nāths.

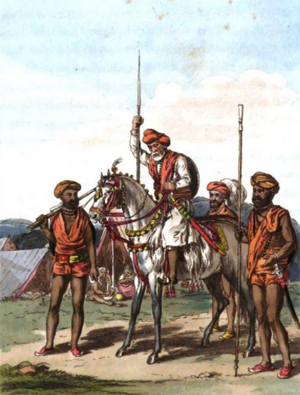

Conflicts Involving Armies of Nāgās

From the late 16th century until the early decades of the 19th century, many prominent regional regents recruited bands of nāgās to fight in interregional struggles for power. The Mughal emperor Aurangzīb authorized in 1692/1693 five Rāmānandī commanders and their armies to move without hindrance. The British officer lieutenant-colonel Valentine Blacker included “gossyes” (i.e. gosāīṃs) in his account of the rise of infantry forces in India in the 1700s, comparing them in proficiency to Afghan and Jāt ̣Sikh khālsā troops (the Sikh order, or brotherhood, known as the khālsā, was, according to tradition, founded by Gurū Gobind Singh, and its troops were drawn almost entirely from the Jāt ̣ caste of northwestern cultivators). They were particularly renowned for their nocturnal guerilla operations: naked, sometimes slippery with oil, and dangerous with the dagger. The disposition of regents to employ nāgā armies may have also been partly due to their reputation for “supernatural” yogic abilities, and the consequent potential apprehension of adversaries, and to several historical legal statutes that either restricted or annulled the ability of states to prosecute them, being of religious orders, for crimes committed.

In 1763, Pṛthvī Nārāyaṇ Śāh, king of Gorkha and the founder of modern Nepal, was engaged in a campaign to extend his empire into the Kathmandu Valley. His chief advisor and strategist was a Nāth siddha named Bhagavantnāth, who used his influence to negotiate various matrimonial and military alliances between Gorkha and some of the other 45 kingdoms of western Nepal. During Pṛthvī Nārāyaṇ’s attack on the village of Saga, his Gorkhalese troops were confronted by five hundred nāgās – under the leadership of Gulābrām – who were fighting on behalf of one of his opponents, Jāyāprakāś Malla, king of Kathmandu. All the nāgās were slaughtered by the Ghorkalese army, though Gulābrām escaped.

During the 1780s, some seven hundred nāgās died in battle in another Himalayan province, Kumaon. A total of 1,400 nāgās had been enlisted, with the promise of substantial financial rewards, by King Mohan Cand in his unsuccessful attempt to recapture his seat in Almora, from which he had been deposed by his rival, Harsḍev Josị̄, king of the neighboring Himalayan province, Garhwal.

In the political history of North India, the most influential armies of nāgās were those commanded by three Daśanāmī gosāīṃs, Rājendragiri (d. 1753), and his two celās (disciples), the adopted brothers Umrāvgiri (b. 1734) and Anūpgiri (Himmat Bahādur; 1730–1804). These gosāīṃs had complex relationships with several wives, courtesans, and offspring, leading to lengthy legal disputes over inheritance and property. At the height of their careers, the gosāīṃs commanded armies of up to 20 thousand horse and foot soldiers. The movement and recruitment of troops were greatly facilitated by a network of weapon stocks and grain stores in the countryside. When on campaigns, most of which were in the Gangetic region, they carried equipment – including materials for mounting fortified buildings – on elephants and other pack animals and had camel-mounted guns. The army was equipped with excellent horses and state-of-the-art weapons, including musketry and artillery.

The gosāīṃs Rājendragiri, Umrāvgiri, and Anūpgiri, and their nāgā saṃnyāsī armies, fought on behalf of several North Indian regents who were the most important political actors in the region during the lifetimes of these gosāīṃs. Their mercenary approach to war resulted on several occasions in their changing sides to fight on behalf of former adversaries. The gosāīṃs’ patrons in the 18th century included Safdar Jang –- who was vazīr (chancellor) to the Mughal emperor Ahmad Shāh and ruler of the province of Awadh (the gosāīṃs began service with Safdar Jang in 1731) -– and his successor Shuja-ud-Daulah. (The Mughals also supported Rāmānandī nāgās at Ayodhya: Safdar Jang granted seven bīghās [approx. five-eights of an acre] of land at Hanumān Hill in Ayodhya to Abhay Rām Dās, the mahant of the Nirvāṇī anī [see below].) Other patrons of the gosāīṃs included the Maratha rulers Mahādjī Śiṃde and Alī Bahādur, the Mughal emperor Shāh Alam, the Jāt ̣ ruler Javāhir Singh, and the Persian Nāzaf Khān, who Anūpgiri joined in his campaign in 1776 in northern Rajasthan.

In league with the Afghans, the gosāīṃ nāgās also fought the Marathas. In the lead up to the Anglo-Maratha war, Anūpgiri and his forces also supported the East India Company, under Richard Wellesley. Campaigns were launched by the gosāīṃs against encroaching Afghans, and an unsuccessful attempt to capture Delhi was pursued in 1753, resulting in the death of Rājendragiri. In 1775 the gosāīṃs captured most of Bundelkhand from the Marathas. However, by 1803 the gosāīṃs were supporting the British in their (successful) campaign to conquer Bundelkhand. The gosāīṃs, in particular the Ānanda and Jūnā akhāṛās (see below), remained in service to the British for 17 months.

Beginning in 1743, numerous minor rebellions (which were eventually suppressed, by 1800) took place, in a period of famine, against the rule, trade monopolies, and taxation imposed by the East India Company in Bengal, which for most of that time was under the governorship of Warren Hastings. Peasants and marauding Sufi faqīrs and Daśanāmī gosāīṃs fought company troops in the Bengal region, with many casualties on all sides, in a series of military encounters. However, it was with the assistance of an army of gosāīṃs under Anūpgiri that the British were eventually able to capture Delhi and thereby extend their control over large parts of North India. However, after 1857 the company had no further use for the gosāīṃs and suppressed their military and banking activities. By this time, the saṃnyāsis, owing to their mercenary activities, had become the wealthiest bankers and largest landowners in North India. (Many of the akhāṛās still derive revenue from landholdings today.)

Since the effective curtailment of their military power by the British, the main public arenas for the display of the military organization of the akhāṛās is at melās, particularly at kumbh melās.

Becoming a Nāgā in an Akhāṛā

To become a sādhu not only entails renouncing one’s family name and former caste identity in a rite of renunciation (saṃnyāsa; see → āśrama and saṃnyāsa) but also results in acquiring a new identity and a new name as a member of a recognizable renunciate sect. The saṃnyāsa rite to become a Daśanāmī saṃnyāsī is performed in two stages: the first is the pañc guru saṃskār, when the initiate acquires five gurus, and the second initiation is the virajā homa (the rite of purification), which is usually performed at a kumbh melā, when the initiate performs his own funeral rites, thereby relieving any family member of future responsibility in that regard. Once initiated as a sādhu, the initiate may then perform a subsequent rite to become a nāgā in an akhāṛā (which in some akhāṛās entails the tendon in the penis being broken, to ensure celibacy). The processes of becoming a nāgā are similar for Rāmānandīs, the first initiation being the pañc saṃskār dīkṣā, which is almost identical to that performed by → Śrīvaisṇạvas (with whom the Rāmānandīs have a complex historical connection). A second ritual is required to become a tyāgī (see below), and a third ritual is traditionally required to become a nāgā, but in recent decades nāgās have been initiated without their first becoming tyāgī.

At kumbh melās one may see the camps of the 13 akhāṛās extant in South Asia. The Śaiva Nāths also have institutions in several places in India and Nepal but camp separately from the 13 akhāṛās and are not within the organization of akhārạ̄s pertaining to the other Śaiva and Vaisṇạva sects. Seven of the 13 akhāṛās are Śaiva Daśanāmī saṃnyāsī akhāṛās. Three akhāṛās of the 13 are of the Vaisṇava Rāmānandī Sampradāy, which are referred to as anīs (army corps) in Vaisṇava terminology, akhāṛā being a subdivision of an anī. The Dādūpanth (see → Dādū Dayāl) also has an akhāṛā, which has an affiliation with the Rāmānandīs.

The other three of the 13 akhāṛās are affiliated with the Sikh tradition. Two are Udāsī (“detached”; see also → sādhus), namely, the Baṛā (large) Pañcāyatī Udāsī Akhāṛā, and the Chotạ̄ (small) or Nayā (new) Pañcāyatī Udāsī Akhāṛā; the third of the Sikh-affiliated akhāṛās is the Nirmal Pañcāyatī Akhāṛā. Although historically involved in the Sikh movement, these three akhāṛās function as independent organizations. All 13 akhāṛās have administrative offices, particularly in the cities of Banaras, Prayag (Allahabad) and Haridwar (for the Daśanāmīs), Ayodhya (for the Rāmānandīs), and Punjab state (for the Udāsīs).

Overseeing the activities of all 13 akhāṛās is an organization, the Akhil Bharatiya Akhara Parishad, which is based in Haridwar and meets to decide on practical and policy issues.

The Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsī Akhāṛās

Daśanāmī means “he who has [one of] ten names,” those initiate names being Giri (hill), Purī (town), Bhāratī (learning), Vana (or Ban: forest), Parvata (mountain), Araṇya (wilderness), Sāgara (ocean), Tīrtha (pilgrimage place), Āśrama (hermitage), and Sarasvatī (knowledge). The most common names are Giri, Purī, and Bhāratī.

The seven Daśanāmī akhāṛās are the Nirañjanī, Jūnā, Mahānirvāṇī, Ānanda, Āvāhan, Atạl, and Agni akhāṛās. The leading akhāṛās, in terms of members and property, are the Nirañjanī and Jūnā. The Jūnā has the largest number of nāgās and is believed to be the oldest of the akhāṛās. Members of the akhāṛās are also affiliated to one or another of 52 (or 51) maṛhīs, which are subdivisions of the akhāṛās. The system of maṛhī organization is further organized in a system of eight dāvās (section, claim). Within each akhāṛā, there is a hierarchy of authority – mahant, śrī mahant, and mahāmaṇḍaleśvara – and (nominally) at the apex there are the śaṅkarācāryas (see below). The mahāmaṇḍaleśvaras usually live in their own maṭhs or āśrams and generally have little practical involvement in the daily operation of the akhāṛā, except when they preside over initiation rituals and become involved in administrative issues. In all akhāṛās (including those of the Rāmānandīs, Udāsīs, and Nirmals), each of which has an administrative body (pañc or pañcāyat), there is usually a sabhāpati (president), and beneath mahants there is a hierarchy of other elected functionaries: kārbārīs (assistants), thānāpatis (property managers), sacivs (secretaries), pujārīs (who perform ritual worship), koṭvāls (guards), and koṭhārīs/bhaṇḍārīs (who manage daily supplies). The main venue for initiations, elections to positions within the akhāṛā, and administrative discussions is kumbh melās. The Daśanāmī akhāṛās administer up to a hundred institutions, including temples, maṭhs, and āśrams.

Each of the Daśanāmī akhāṛās has a tutelary deity, namely, Kārttikeya (Nirañjanī), Dattātreya (Jūnā), Kapil Muni (Mahānirvāṇī), Sūrya (Ānanda), Siddh Gaṇeś (Āvāhan), Ādi Gaṇeś (Atạl), and Gāyatrī (Agni). The nāgās of each Daśanāmī akhāṛā revere the bhālā, which is a five to seven-meter-long javelin engraved with the sign of the respective deity of the akhāṛā. It is carried at the front of the arrival (peśvāī) and “royal” bathing processions (śāhī snān) at melās by the chief mahant or by nāgās. The bhālā is usually kept at the headquarters of the akhāṛā that it represents, but during melās, it is planted in the ground near the temporary shrine of the tutelary deity, at the center of the akhāṛā’s camping area.

The members of six of the seven Daśanāmī akhāṛās, apart from the Agni akhāṛā, take one of the “ten names,” but members of the Agni akhāṛā take one of the four following names: Svarūpa, Prakāśa, Ānanda, or Caitanya. These are what are known as brahmacārī (orthodox Brahman undergoing religious studentship and chastity) names, which are the same four names given to members of the other main wing of the saṃnyāsīs, the daṇḍīs.

The saṃnyāsī akhāṛās, to which nāgās belong, function independently from other saṃnyāsī organizations, those pertaining to the other branches of the Daśanāmī order, comprising daṇḍīs and paramahaṃsas. Daṇḍīs are orthodox Brahmans and carry a stick (daṇḍa). They frequent their own maṭhs and āśrams and have no organizational connection to the akhāṛās. Their link to the akhāṛās is only in respect to their common belief in the foundation of their order by Śaṅkarācārya (→ Śaṅkara). Paramahaṃsas are affiliated with one or another of the akhāṛās but usually live independently in their own maṭhs.

The Daśanāmī saṃnyāsī order claims descent from the philosopher Śaṅkarācārya (fl. c. 700 CE), through four disciples who, according to tradition, were established in four monasteries ( pīṭhas) at four places in India (in the north, south, east, and west); the five incumbent śaṅkarācāryas – two in the south – claim descent from these disciples. However, the tradition of the founding of four monasteries most probably dates from no earlier than the late 16th century.

The founding of the Daśanāmī akhāṛās is difficult to discern. According to traditions among the Daśanāmīs – one of which is recorded in an influential account by J. Sarkar (1958), which has been reiterated with anomalies in several subsequent publications – the first akhāṛā to be founded was Āvāhan in 547 CE, followed by Atạl (646 CE), Mahānirvāṇī (749 CE), Ānanda (856 CE), Nirañjanī (904 CE), Agni (1136), and Jūnā (1156). (In other sources the founding year of the Agni akhāṛā is given as 1370.) However, J. Sarkar adds one thousand years to some of the founding dates, which produces many inconsistencies. Notwithstanding accounts stating a greater antiquity, it seems probable that it was during the latter decades of the 16th century and the early decades of the 17th century that the Daśanāmī saṃnyāsī akhāṛās first formed, a time when diverse lineages of both monastic and militant renunciates coalesced into a sect with a distinct identity, sectarian history, and founding guru, namely Śaṅkarācārya.

The Rāmānandī Akhāṛās

The Rāmānandī Sampradāy has both lay and sādhu communities, the latter comprising rasiks, tyāgīs, and nāgās, and is one of the four Vaisṇava Sampradāyas (catuḥ sampradāyas), the constitution of which has changed twice during the last four centuries. The catuḥ sampradāyas, which meet at kumbh melās, have an administrative body, the Akhil Bharatiya Khalsa, which oversees 412 sub-branches (known as khālsās).

The traditional dates (based on the Agastyasaṃhitā) of → Rāmānanda are 1299–1410, but it seems more probable that Rāmānanda flourished in the 15th century. While some sources maintain that Rāmānanda came to northern India from the south (where he had been a disciple of Rāghavānanda), Rāmānandīs claim that Prayag was his place of birth. The language of the texts attributed to Rāmānanda indicates a North Indian provenance. “Rāmānandī” as a term of self-designation was first used around 1730.

The Rāmānandīs, whose main deities are → Rām, Sītā (see → Draupadī and Sītā), and Hanumān, appear to have organized their military branches between 1650 and 1720. There is a reference from 1734 at Galta (near Jaipur) to seven branches of the Rāmānandī Sampradāy, which seems to indicate the extant organization of seven Rāmānandī akhāṛās. It is most probable that the catuḥ sampradāyas were organized into systems of dvārs, anīs, and akhāṛās in two stages during four successive conferences, at Vrindavan (c. 1713), Brahmapuri (near Jaipur; c. 1726), Jaipur (1734), and Galta (1756). It was Bālānand who in the mid-18th century organized the army of nāgās (the rāmḍāl) for service to Mādhav Siṃh, regent of Jaipur. Among the Rāmānandīs, 52 dvārs (doors/gates) – which are essentially lineages – are assigned to places throughout India and mirror the 52 maṛhīs of the Daśanāmī saṃnyāsīs.

Rāmānandī tyāgīs (renunciates), who are the largest subsection of the Rāmānandīs, have a lifestyle and appearance that are almost identical to those of Daśanāmī nāgās. Rāmānandī tyāgīs are also referred to as vairāgīs (or bairāgis; without passion). While the tyāgīs are Rāmānandī ascetics, it is the Rāmānandī nāgās who are soldiers, who carry weapons, and who are given money by tyāgī mahants at melās to protect the order. Technically, only the nāgās are said to be in the akhāṛā. Unlike the tyāgīs, Rāmānandī nāgās wear stitched cloth and do not wear jaṭā. A Rāmānandī disciple (who usually receives the surname “Dās” during initiation) wishing to enter an akhāṛā has to pass through seven stages before he becomes a Vaisṇava nāgā (also known as nāgā atīt):

(1) yātrī (collects nīm [neem, bot. Azadirachta indica] sticks for his superiors and wanders alone or with the jamāt [fighting unit]);

(2) chorā (serves, draws water, and makes leaf-plates);

(3) bandagīdar (looks after food stores, serves food, and cleans nāgā atīt’s utensils);

(4) huṛdaṅg (cooks, offers food to the deity, calls “Harihar” [i.e Visṇụ-Śiva], carries the insignia and flag of the akhāṛā, and learns weaponry);

(5) mureṭhiya (worships the deities, supervises sevaks [servants], calls “jay” [“victory”], and has mastered weapons):

(6) nāgā (administers the akhāṛā, worships the deity, protects the order’s property, leads the jamāt, and prepares for the kumbh melā); and

(7) atīt (decides important issues and guides nāgās).

This process of becoming a nāgā takes 12 years, after which he may vote in the akhāṛā, as a member of the pañc (the organizational body). Vaisṇạva nāgās are organized in four divisions (selīs), according to where they were initiated: Haridvārī (at Haridwar), Ujjainīya (at Ujjain), Sāgarīya (at Ganga Sagar, near Calcutta), and Basantīya (at other places). The most important center for Rāmānandī nāgās is the Hanumāngaṛhi Temple in Ayodhya.

The three Rāmānandī anīs collectively have eight akhāṛās among them: two for the Digambar anī (Rām Digambar, Śyām Digambar), three for the Nirvāṇī anī (Nirvāṇī, Khākī, Nirālambī), and three for the Nirmohī anī (Nirmohī, Mahānirvāṇī, Santosị̄). The akhāṛās’ banners all display the sun (sūrya), an emblem of Visṇu.

The Dādūpanth Akhāṛā

The Dādūpanth also has an akhāṛā, which joins the (Rāmānandī) Nirmohī anī for bathing at kumbh melās. Toward the end of Akbar’s reign, Dādū (1544–1604), a cotton cleaner from Ahmadabad who was a nirguṇī bhakt (see → nirguṇa and saguṇa), organized a new sect of Rām devotees, the Dādūpanth, which comprises virakts (ascetics), vastradhārīs (householders), and nāgās (khākī [ash-clad] virakts). Dādūpanthī nāgās had a prominent role in the armies of various regents, particularly of Jodhpur and Jaipur, in the 18th and 19th centuries. They were employed as mercenaries from 1799 to 1938.

Dādūpanthī nāgās claim that they are descended from Sundardās, an early disciple of Dādū, and thus from the late 16th or early 17th century. Although the genealogy of the Dādūpanthī nāgās may have begun in the mid-17th century, at the earliest, firm records are only available from the second half of the 18th century. The nāgās were officially constituted in akhāṛās in 1756, but may have previously fought alongside Rāmānandīs. The organization of the nāgās into 11 akhāṛās, which are subsumed within seven jamāts, is attributed to Kevalrām and Hṛdayrām. Nearly all of the nāgās were of Rājpūt descent. By the late 18th century, the armed jamāts were numerically and politically dominant in the Dādūpanth.

Sikh-Affiliated Akhāṛās

The Sikh-affiliated akhāṛās, the Baṛā Udāsī, Chotạ̄ Udāsī, and Nirmal, revere and recite daily the Gurū Granth Sāhib, the Sikh text that occupies a central place in all Sikh gurdvārās. Also of importance to the Udāsīs are the Udāsī Bodh, composed in Braj in 1858 (but written in Gurmukhi), and the Mātrā (measure/discipline; attributed to Srī Cand), besides which they have their own version of the Gurbilās (early biography/hagiography of Gurū Gobind Singh) and Janamsākhīs (biographies/hagiographies of Gurū Nānak). Like the practice among Daśanāmīs and Rāmānandīs, five mahants preside over the first initiation, whereby the initiate gains a new surname, usually “Dās” or “Brahm.” The initiate should be detached, shunning women, gold, tobacco, and spirits – though, as among other renunciate sects, occasionally Udāsīs marry and live as householders. Unlike Khālsā Sikhs, Udāsīs may shave their beards and cut their hair.

The Udāsīs are closer to mainstream Sikh tradition than some of the other breakaway Sikh sects of the 17th century, such as Mīnā (founded by Pṛthi Cand, 1558–1618), Dhir Maliā (followers of Dhir Mal, 1627–1677), and Rām Rāiyā (followers of Har Rāi, 1630–1661, the seventh Sikh guru). Distinctive traits of the Udāsīs are their Advaita Vedānta (advait brahm) philosophy (through which they interpret Sikhism), keeping a dhūnī, and practicing Hatḥa Yoga (see → Yoga).

The tutelary deity of Udāsī akhāṛās is Candra Bhagvān (believed to be an incarnation of → Śiva), who was Śrī Cand (b. 1494), the eldest of the two sons of Gurū Nānak (1469–1539). After the death of Nānak, the leadership of the Sikhs passed to Gurū Aṅgad (a householder), and not to Gurū Nānak’s son Śrī Cand (a bachelor), who, according to Sikh tradition, founded the Udāsī order. Although Śrī Cand is not recognized within the Sikh gurū paramparā (succession of teachers), neither is he rejected. However, there is some historical evidence that Śrī Cand and his followers may have been rejected from the Sikh order. According to tradition, Śrī Cand lived past the age of one hundred, into the time of the sixth gurū of the Sikhs, Gurū Hargobind (1595–1644), which would mean that the Udāsī order was probably founded sometime between the end of the 16th century and the early 17th century. The gaddi (royal seat/sectarian leadership) of the Udāsīs passed from Śrī Cand to the soldier and householder Bābā Gurditā (1613–1638), who had four preaching disciples (masands), each of whom, according to tradition, founded in 1636 a dhūān (dhūnī), which are the four main divisions of the Udāsīs, namely, Bābā Hasan (1564–1660), Phūl Sāhib (or Mīān/Mīhān Sāhib), Almast (1553–1643), and Gondā/Goindā (or Bhagat Bhagvān); these four leaders are known as the ādi (original) udāsīs.

According to another account, however, Mīān Sāhib and Bhagvat Bhagvān (i.e. Bhagat Gir, who was a Daśanāmī) founded not dhūāns but missionary centers (bhakṣīṣes). According to tradition, six bhakṣīṣes were gifted by the Sikh gurūs, Hargobind, Har Rāi, Tegh Bahādur, and Gobind Singh (1666–1708), between around 1640 and 1700. The two most important bhakṣīṣes are those of Bhāī Pherū and Mīān Sāhib. Udāsī institutions, which have a tradition of education, generally function independently and are mostly in the Punjab region, though some are in eastern India; they comprise akhāṛās (which are larger institutions), devās (smaller institutions), and dharmśālās (rest houses for travelers and pilgrims). The head of an institution is referred to as śrī mahant.

The Baṛā Udāsī Akhāṛā was founded at Prayag in 1779 by Mahant Pṛtham Dās (1752–1831), with whose akhāṛā all four dhūāns are associated (some Udāsī institutions are not directly affiliated with the dhūāns). Some followers of Pṛtham Dās are naṅgā (i.e. nāgā); two subsects of naṅgā Udāsīs (the Nirbāṇ and the Nirañjanī) claim origins in the akhāṛā of Pṛtham Dās. They wear laṅgoṭī and besmear themselves with ashes.

The Chotạ̄ (or Nayā) Udāsī Akhārạ̄ was founded in 1840 by Mahant Santokh Dās and some followers of Bhāī Pherū (i.e. Saṅgat Sāhib), a disciple of Har Rāi. Gurū Gobind Singh is credited in some sources with the institution of the Nirmal order, of which the akhāṛā (whose headquarters is in Kankhal, near Haridwar) was officially founded in 1862 under the leadership of Mahitab Singh (1811–1871).

Between the 1790s and 1840s, the Udāsī and Nirmal orders received extensive state patronage, and by the end of the 19th century, their establishments had increased fivefold, to around 250. In the early 1920s, during the Gurdwara Reform Movement, conflict arose between Udāsīs and Akālī Sikhs (Akālī – or Nihaṅg – Sikhs are a military sub-branch of the Sikh khālsā), resulting in a significant loss of influence for Udāsīs; though in recent decades, the Udāsīs have experienced a revival.

Bibliography

Alter, J.S., The Wrestler’s Body: Identity and Ideology in North India, Oxford, 1992.

Burghart, R., “Wandering Ascetics of the Ramanandi Sect,” HR 22/4, 1983, 361–390.

Clark, M., The Daśanāmī Saṃnyāsīs: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order, Leiden, 2006.

Farquhar, J.N., “The Organisation of the Sannyasis of the Vedanta,” JRASGBI, 1925, 479–486.

Ghosh, J.M., Sannyasi and Fakir Raiders in Bengal, Calcutta, 1930.

Ghurye, G.S., Indian Sadhus, Bombay, 1953, 21964.

Gross, R.L., The Sadhus of India: A Study of Hindu Asceticism, Jaipur, 1992.

Hausner, S.L., Wandering with Sadhus: Ascetics in the Hindu Himalayas, Bloomington, 2007.

Lorenzen, D.N., “Warrior Ascetics in Indian History,” JAOS 98/1, 1978, 61–75.

Orr, W.G., Armed Religious Ascetics in North India, Manchester, 1940.

Pinch, W.R., Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires, Cambridge UK, 2006.

Sanderson, A., “The Śaiva Age: An Explanation of the Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period,” in: S. Einoo, ed., Genesis and Development of Tantrism, Tokyo, 2009, 41–349.

Sarkar, J., A History of the Dasnami Naga Sanyasis, Allahabad, 1958(?).

Singh, S., Heterodoxy in the Sikh Tradition, Jalandhar, 1999.

Sinha, S., & B. Sarasvati, Ascetics of Kashi: An Anthropological Exploration, Varanasi, 1978.

Thiel-Horstmann, M., “On the Dual Identity of Nāgās,” in: D.L. Eck & F. Mallison, eds., Devotion Divine: Bhakti Traditions from the Regions of India (Studies in Honour of Charlotte Vaudeville), Groningen, 1991, 255–272.

Winter Jones, J., ed., The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema (1503–1508), London, 1863.