Papers of Sylvia Scaffardi c.1910- 2001 (nee Crowther-Smith)by Hull History Centre

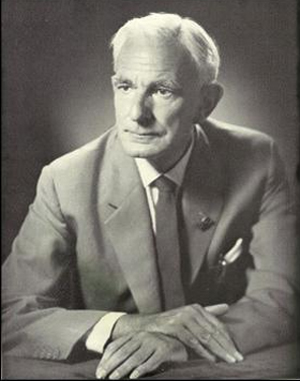

Biographical background:Sylvia Crowther-Smith was born on 20 January 1902 in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Her father, Sydney James Crowther-Smith, emigrated from England to Brazil around 1888, where he met and married the daughter of wealthy Brazilian landowners in the late 1890s. By 1914, the family had moved to England, and settled in Eastbourne, in order for Sylvia and her sister Lydia to be educated in an English boarding school. After the First World War, Sylvia won a scholarship to Royal Holloway College, where she read English and became involved in the college dramatic society. Through the dramatic society, she met Lena Ashwell, a former West End star, and joined the Lena Ashwell Players. She then travelled the country working for touring companies and provincial repertory theatres. Sylvia first met Ronald Kidd, the founder of the National Council for Civil Liberties, when she joined a theatre company in Hertfordshire for a production of Ashley Duke's The man with a load of mischief (1926). Kidd had been engaged as stage manager and also played the part of the nobleman.Ronald Hubert Kidd was born in 1889 into a medical family and grew up in Hampstead. He read science at University College London, but did not obtain a degree. He then lectured for

the Workers' Educational Association and became involved in the campaign for women's suffrage. He was conscripted during the First World War, but never saw active service, being discharged for health reasons.

He worked for a year as secretary to the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum, before entering the civil service, firstly in the Ministry of Labour and then the Ministry of Pensions. However his career ended when he resigned in protest at the cuts in pensions for shell-shocked war veterans. Thereafter he found work as a freelance journalist, publicist, actor and stage director. By the time he met Sylvia, he was estranged from his wife Isadora and daughter Anne in Bristol, and living in lodgings in London.

Sylvia moved to London and began living with Kidd in the late 1920s, and entered his Bohemian and radical circles. She began to work as a freelance editor around this time, whilst Kidd opened the Punch and Judy bookshop at 43 Villiers Street. The origins of the National Council for Civil Liberties lie in the work which Kidd began in 1932 of observing the Hunger Marches as they arrived in London and reporting on the policing of the events. Sylvia joined him in this work (including at an anti-Nazi demonstration on 17 December 1933), and when the committee which formed the nucleus of the National Council for Civil Liberties first met on 22 February 1934, she was elected Honorary Treasurer.

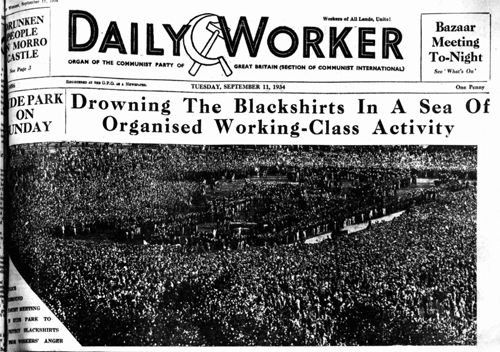

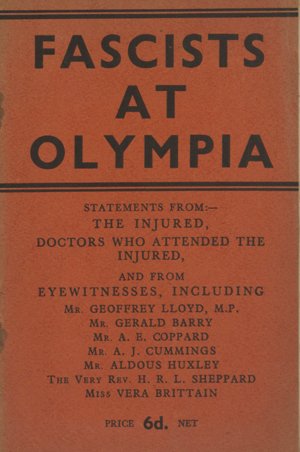

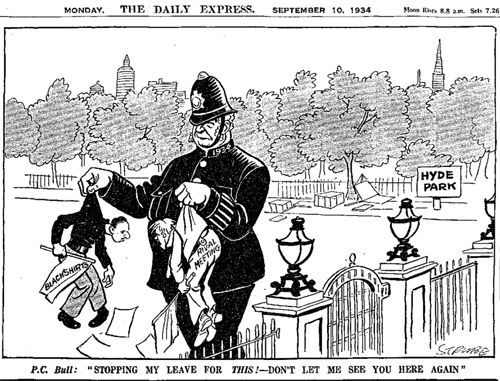

In July 1934, she began to receive a salary for her work and the title of Assistant Secretary. Effectively, the organisation's first office was the room at no.3 Dansey Yard, off Shaftesbury Avenue, where Kidd and Crowther-Smith lodged. They ran the NCCL together in its early years, with Kidd as General Secretary, supported by an Executive Committee which included Vera Brittain, Claud Cockburn, Rev. Dick Shepherd, Harold Laski and Kingsley Martin, and by the lawyers DN Pritt and WH Thompson on the General Purposes Committee. However the volume of work put pressure on Kidd's health and from 1938 onwards, the number of office staff employed by the organisation had to be gradually increased. The issues dealt with by the NCCL during the 1930s and early 1940s included the Incitement to Disaffection Bill of 1934, the banning of 'nonflam' films, the operation of the Special Powers Acts in Northern Ireland, the rise of fascism and anti-semitism (especially the British Union of Fascists meeting at Olympia on 7 June 1934), the Public Order Act of 1936, political bias in the letting of public halls and by the police, the Harworth Colliery dispute of 1937, the case of Major Wilfred Foulston Vernon, the freedom of the press and the BBC, and the impact on civil liberties of the outbreak of war.

Sylvia resigned as Assistant Secretary of the NCCL in August 1941, at a time when her mother was dying of cancer and Kidd was suffering from a recurrence of heart problems. In November, Kidd had to give up the post of General Secretary and was made Director of NCCL instead, in an effort to reduce his workload. However he did not recover his health and died at the age of 53 on 12 May 1942.

A few months before Kidd's death, Sylvia entered the civil service, working in the Planning Division of the Ministry of Works on the White Paper on rural land utilisation in wartime. The Division was then formed into an independent Ministry of Town and Country Planning, where she remained until 1944 and her move into the wartime propaganda work of the Publications Division of the Ministry of Information. She was employed in the post-war Central Office of Information until 1952, when she was made redundant in a wave of cuts to temporary civil servant posts by the Conservative government. Using her redundancy money as security, she began to work as a freelance journalist. She also trained as a teacher and worked for a period in a secondary modern school in south London.

In 1958, at the age of 56, Sylvia married John Scaffardi and they lived together in Carshalton in Buckinghamshire. She was widowed in 1971. She wrote two autobiographical books, the first, an account of her work with Ronald Kidd during the 1930s, Fire under the carpet (Lawrence & Wishart, 1986) and the second, about her Brazilian childhood, Finding my way (Quartet Books, 1988). Sylvia died on 27 January 2001. She continued her association with and her support for the NCCL until her death.

Custodial History:Donated by the Estate of Sylvia Scaffardi, via Liberty, 18 September 2001

Description:This collection contains material gathered together by Scaffardi from several sources in the process of writing her autobiography, Fire Under the Carpet (Lawrence & Wishart, 1986); it includes papers of Ronald Kidd, research papers of Brian Cox and records of the National Council for Civil Liberties, as well as a range of publications. An artificial arrangement has been imposed on the collection, and there is a large amount of overlap between the sections.

National Council for Civil LibertiesThis material complements, and in some instances duplicates, the main Liberty archive [U DCL]. There is a bound volume of early annual reports, dating from 1934 to 1957 [U DSF/1/1]; this is significant because there do not appear to be any annual reports before 1938 in the main archive [U DCL/73A]. The early minutes of the NCCL have been lost [a microfilm of minutes dating from 1944 onwards is the earliest survival at U DCL/102] and hence the few bundles in this collection which contain Executive Committee minutes from the 1930s and early 1940s, and some correspondence of Ronald Kidd as General Secretary, are valuable in piecing together the work of Kidd and other founder members [U DSF/1/7-9]. There are also examples of draft articles and speeches by Kidd and Crowther-Smith in these bundles, as well as material about Kidd having to give up the role of General Secretary and the question of who was to replace Henry Nevinson as President [related papers on these last two topics can also be found at U DSF/2/6]. The NCCL pamphlets in the collection span 1935 to 1995, but are concentrated in the 1930s and 1940s [U DSF/1/17-62]. A large proportion can also be found in the main Liberty archive, but this set has been kept together to illustrate the interests of Kidd and Crowther-Smith.

Ronald KiddThere is very little surviving material on Ronald Kidd in the main Liberty archive and therefore, although these papers are far from extensive, they still comprise a useful source. There are two files relating to Kidd's tour of Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Austria in 1938 [U DSF/2/2-3] and these contain a variety of material, ranging from letters of introduction and correspondence with those involved in the movement in defence of human rights and against anti-semitism in Czechoslovakia, to Kidd's itinerary and notes made during his journey. There is also a set of photographs of Jasina and other places in Sub Carpathian Russia and Slovakia, sent by Dr Maximilián Ryšánek in Brno, photographs of anti-semitic graffiti [possibly in London] and contemporary travel brochures and maps of the region. The only surviving example of a personal letter from Kidd to Crowther-Smith dates from this tour and was sent from Bratislava [see file U DSF/2/6]. After his return to England, Kidd travelled the country holding public meetings on Czechoslovakia and this is documented by correspondence, publicity leaflets and cuttings of reports in the press [U DSF/2/3].

Kidd's work for the NCCL in the early 1940s focussed on areas such as editing and writing articles for the journal Civil Liberty, and writing pamphlets. Examples of this can be found at U DSF/2/4-5, including drafts of his pamphlet on The fight for a free press (1942) [there is a printed copy at DSF/1/34]. There are four surviving pocket diaries, detailing the meetings and appointments which Kidd attended in 1934, 1935, 1936 and 1938 [U DSF/2/9], along with his passport, issued in 1936, and a number of undated photographs of Kidd [U DSF/2/10-11]. Unusual items include some photographs of political posters on display in wartime France, a publicity leaflet for the Soho Literary Group, organised by Kidd, and the annotated script of a play by Lennox Robinson, 'The lost leader', which Kidd must either have directed or played a part in [U DSF/2/14, 13, 12].

Sylvia ScaffardiThere is a small amount of material relating personally to Sylvia Scaffardi and her work, namely evidence submitted to Lord Justice Scott's Committee on Land Utilisation for Rural Areas in the early 1940s, which she gathered in her role as a civil servant in the Planning Division of the Ministry of Works [U DSF/3/1], and papers about her childhood in Brazil and her Brazilian grandparents [U DSF/3/3].

Barry CoxBarry Cox was commissioned by the NCCL in the late 1960s to write a history of the organisation and this was published in 1975 as Civil liberties in Britain (Penguin). In the course of his research, he undertook a large number of interviews with founder members and contemporary figures in the NCCL, and the interviews were transcribed from tape by Sylvia Scaffardi. The annotated transcripts are included in this collection and include interviews with people such as Elizabeth Acland Allen, DN Pritt, Kingsley Martin, Claud Cockburn, Sylvia Scaffardi herself, Martin Ennals and Tony Smythe [U DSF/4/2-4].

PublicationsThis set of pamphlets and periodicals has been kept together within the collection (rather than being transferred to library stock), again as an illustration of the interests of Kidd and Scaffardi. There are a number of significant items in the fields of politics and literature, such as the August 1914 edition of the journal English Review containing part 5 of a serialised story by HG Wells, 'The world set free: a story of mankind' [U DSF/5/2]; a typescript on civil liberties in 1918 by Monica Ewer of the first National Council for Civil Liberties (founded in 1915 as the National Council Against Conscription) [U DSF/5/3]; two anti-semitic publications in German dating from 1937 and 1938, the second published by the National Socialist German Workers [Nazi] Party [U DSF/5/33 & 44]; two photographic compilations about the Spanish Civil War, issued by the Spanish Embassy in London in 1937 and 1938 [U DSF/5/34-35]; and the classic 1949 pamphlet, The time of the toad, by Dalton Trumbo, about the anti-Communist blacklist of Hollywood writers [U DSF/5/72]. The vast majority of these publications date from the 1930s and 1940s.

Arrangement:

U DSF/1 National Council for Civil Liberties, 1934 - 2001

U DSF/2 Ronald Kidd, 1916 - 1985

U DSF/3 Sylva Scaffard, 1930s - 1975

U DSF/4 Barry Cox, 1965 - 1971

U DSF/5 Publications, circa 1910 - 1978

Extent: 1.5 linear metres

Related Material:Records of Liberty (National Council for Civil Liberties) [U DCL]

Access Conditions:Access will be granted to any accredited reader.

U DSF/1 National Council for Civil Liberties U DSF/1/1-6 Annual reports U DSF/1/7-12 Files U DSF/1/13-16 Periodicals U DSF/1/17-62 Pamphlets and memoranda 1934 - 2001

U DSF/1/1 Bound vol. of published annual reports and reports of AGMs From 1939, these are mainly printed in Civil Liberty 1 volume 1934 – 1957

U DSF/1/2 Cc. ts. draft of ‘The first year’s work’ by Elizabeth Acland Allen 1 item [1935]

U DSF/1/3 Ts. annual report 1 item 1940

U DSF/1/4 Secretary’s report for the year 1 item 1944

U DSF/1/5 Ts. drafts of two annual reports 2 items post 1945

U DSF/1/6 Published annual reports 11 items 1957 - 1994

U DSF/1/7 Artificial file of miscellaneous papers Including constitution and rules (1946); speech on civil rights for colonial peoples; draft submission about the BBC; annotated typescript by IO Evans, ‘For boys and girls who think freedom worth having’ (May Day 1935); speech on press freedom by Sylvia Crowther-Smith (1953); Executive Committee minutes; circular letters from Ronald Kidd as NCCL General Secretary; editorial for Civil Liberty (1941); letters from Stefan Zweig (1), JBS Haldane (1) (with Kidd’s reply), WR Hooper and others; ms. notes by Kidd about the management of the NCCL office; leaflets about NCCL’s 21st anniversary; ms. transcripts of anti-Semitic letters received by Lilian Felt and Rose Silverman (1939); decisions of AGM (1953) 1 file 1935 - 1953

U DSF/1/8 Artificial file of miscellaneous papers Including NCCL briefings and leaflets; Executive Committee minutes; circulars; correspondence; papers for conferences on war (1934) and freedom of the press (1941); note by Ronald Kidd about observing a strikers’ march in the East End (26.1.1936); postcard of Kidd; postcard to Kidd from Friedrich R[?] in Moscow; ms. notes on AP Herbert and free speech; leaflets and letters to Sylvia Scaffardi about the Civil Liberties Development Fund (1980); press release about a British report on the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; ms. notes and drafts on the history of the NCCL 1 file 1936 - 1998

U DSF/1/9 Artificial file of miscellaneous papers Including leaflets; notices of meetings; circulars and memoranda; papers about the presidency sub committee (1942); minutes of Executive Committee, General Purposes Committee and Finance and Appeals Sub Committee; papers for International Conference on Human Rights (1947); reports; information sheets and policy statements; letters, including from A Francis James (RAF Ternhill) (1), Elaine Martin (Ronald Kidd’s sister) (1), A Koehler (International Federation of Leagues against Racism and Anti-Semitism) (2), Hertha Christie-Curwen (1), and Arthur Clegg (Colonial Information Bureau) (1), and from Ronald Kidd (2) 1 file 1938 - 1959

U DSF/1/10 Artificial file of miscellaneous papers Including motions for AGM (1964); black and white photograph of a man addressing a meeting [? mass meeting on press freedom, April 1942]; report of conference on the state of civil liberties in Britain (1952); letters and circulars; annotated typescript by Ronald Kidd/Sylvia Crowther-Smith on freedom of opinion and the BBC; examples of headed paper used by Kidd, with testimonials and curriculum vitae; ts. drafts of history of the origins of the NCCL 1 file 1930s - 1964

U DSF/1/11 Artificial file of miscellaneous papers Including press releases (1972); report to 1968 AGM by General Secretary Tony Smythe; ts. ‘The pattern of repression’, issued by Action for People’s Justice; typescripts about Jersey and the Harworth Colliery strike; notes about Ronald Kidd’s health; ms. and ts. notes about the history of the NCCL; transcripts of letters (2) from Sylvia Crowther-Smith to EM Forster (1955); typescript article for Civil Liberty on ‘The democratic retreat in France’ (1940); speech by Ronald Kidd on ‘The question of legislation against racial incitement’ (1937) 1 file 1930s - 1972

U DSF/1/12 File. Correspondence between Fionnuala Ni Aolain, Liberty and various publishers about her research and the publication of her book, The politics of force. Including a fax copy of the agreement to undertake the research for Liberty and her curriculum vitae 1 file 1994 - 1999

U DSF/1/13 Issues of Civil Liberty (journal) 97 items 1937 - 1951

U DSF/1/14 Issues of Civil Liberty (monthly bulletin) 78 items 1965 - 1976

U DSF/1/15 Issues of Rights (journal) 32 items 1976 - 1984

U DSF/1/16 Issues of Civil Liberty Agenda (later Liberty) (newsletter) 11 items 1991 - 2001

U DSF/1/17 Ts. ‘Speakers’ notes on fascism and anti-Semitism’ 1 item 1930s

U DSF/1/18 Pamphlet. Non-flam films 1 item 1935

U DSF/1/19 Pamphlet. Police methods 1 item c 1935

U DSF/1/20 Report of a Commission of Inquiry into certain disturbances at Thurloe Square, South Kensington on March 22, 1936 1 item 1936

U DSF/1/21 Report of a Commission of Inquiry appointed to examine the purpose and effect of the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Acts (Northern Ireland) 1922 and 1923 1 item 1936

U DSF/1/22 The Harworth Colliery strike. A report to the Executive Committee of the National Council for Civil Liberties 1 item 1937

U DSF/1/23 Pamphlet. The strange case of Major Vernon 1 item c. 1937

U DSF/1/24 Pamphlet. Freedom of the press and the challenge of the Official Secrets Act 1 item 1938

U DSF/1/25 Pamphlet. Your freedom in danger 1 item 1940s

U DSF/1/26 Pamphlet. Civil liberties offended 1 item 1940s

U DSF/1/27 Pamphlet. This freedom (Civil Service branch) 1 item 1940s

U DSF/1/28 Conference report. Civil liberty in the colonial Empire 1 item 1941

U DSF/1/29 Pamphlet. The press and the war (Press Freedom Committee) 1 item 1941

U DSF/1/30 Pamphlet. The internment and treatment of aliens 1 item May 1941

U DSF/1/31 Pamphlet. Civil liberties defended 1 item Aug1941

U DSF/1/32 Pamphlet. Harold Laski, Freedom of the press in wartime 1 item c. 1941

U DSF/1/33 Pamphlet. Press freedom 1 item 1942

U DSF/1/34 Pamphlet. Ronald Kidd, The fight for a free press (two different editions) 2 items 1942

U DSF/1/35 Pamphlet. Angela Tuckett, Civil liberty and the industrial worker 1 item c. 1942

U DSF/1/36 Pamphlet. Elizabeth Acland Allen, It shall not happen here 1 item 1943

U DSF/1/37 Pamphlet. Tom Driberg, Absentees for freedom 1 item 1944

U DSF/1/38 Pamphlet. DN Pritt, Defence regulation 1AA 1 item 1944

U DSF/1/39 Pamphlet. RJ Spector, Freedom for the forces 1 item 1940s

U DSF/1/40 Pamphlet. The War Office and the Official Secrets Act: attack on trade union freedom 1 item 1940s

U DSF/1/41 Pamphlet. Elizabeth Acland Allen, Local government and civil liberty 1 item 1945

U DSF/1/42 Pamphlet. The National Council for Civil Liberties. The record of a decade of work 1934 – 1945 for democracy and liberty 1 item 1945

U DSF/1/43 Pamphlet. Civil liberties and the colonies 1 item 1945

U DSF/1/44 Pamphlet. It isn’t colour bar, but… 1 item post 1945

U DSF/1/45 Pamphlet. Geoff Parsons, Black chattels: the story of the Australian aborigines 1 item c. 1946

U DSF/1/46 Conference report, International Conference on Human Rights 1 item Jun 1947

U DSF/1/47 Leaflet on fascism and anti-Semitism 1 item Sep 1948

U DSF/1/48 Pamphlet. Civil servants and politics (Civil Service branch) 1 item c. 1950

U DSF/1/49 Ts. ‘Evidence to the Royal Commission on the Press’ 1 item 1950s

U DSF/1/50 The journey to Berlin. Report of a Commission of Inquiry 1 item 1951

U DSF/1/51 Ts. ‘Memorandum on repressive legislation in the Dominions’ 1 item 1952

U DSF/1/52 Ts. ‘Civil liberties in Kenya’ 1 item 1953

U DSF/1/53 Ts. ‘Civil liberties and the scheme for federation in Central Africa’ 1 item 1953

U DSF/1/54 Ts. Memorandum and supplement, being the NCCL submission to the Royal Commission on the Law relating to Mental Illness and Mental Deficiency 1 item Jan 1955

U DSF/1/55 Pamphlet. 50,000 outside the law 1 item c. 1955

U DSF/1/56 Ts. ‘Anti-Semitism and colour bar. A warning’ 1 item c. 1959

U DSF/1/57 Pamphlet. Civil liberty 1961 1 item 1961

U DSF/1/58 Pamphlet. Public order and the police 1 item 1961

U DSF/1/59 Ts. ‘Report on the demonstration in Grosvenor Square, London, on Mar 17, 1968’ 1 item 1968

U DSF/1/60 Pamphlet. The use of the police for political purposes 1 item mid 20th cent

U DSF/1/61 Pamphlet. 1992 and you 1 item pre 1992

U DSF/1/62 Pamphlet. Northern Ireland: human rights and the peace dividend 1 item 1995

U DSF/2 Ronald Kidd 1916 - 1985

U DSF/2/1 Photocopies of papers from Ronald Kidd’s file as employee of the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum, with correspondence from John Symons of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine 1 bundle 1916 – 1985

U DSF/2/2 File. Tour of Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Austria by Ronald Kidd Travel and tourist brochures for Czechoslovakia and Hungary, maps of Central Europe, black and white negatives of [? Prague] (8) and black and white photographs of anti-Semitic graffiti in [? London] (10) 1 file 1937 – 1938

U DSF/2/3 File. Tour of Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Austria by Ronald Kidd Correspondence (including about travel arrangements); letters of introduction; names and addresses of contacts; ts. itinerary; ms. notes made during the visit; pamphlets; black and white photographs (30) of Jasina and other places in Sub Carpathian Russia and Slovakia; ts. lecture notes on Czechoslovakia; letters arranging public meetings in Britain, with related leaflets and cuttings.

Includes letters from Dr O Frey (Czech Legation, London) (3), Sylvia Eltz (German Social Democratic Workers’ Party, Prague) (1), Victor Gollancz (1), Kingsley Martin (2), Dr Maxmilián Ryšánek (Brno) (2), Secretary General of Ligue Française pour la Défense des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen (1), Willy Werner (Hradec Králové) (1), Czech League against Anti-Semitism, Area Committee for Mähren and Schliesen (1), A Koehler (International Federation of Leagues against Racism and Anti-Semitism) (1) 1 file 1938

U DSF/2/4 File. Articles by Ronald Kidd and editorial work on Civil Liberty Including ms. drafts, cc. typescripts, cuttings and correspondence, with letters from Kingsley Martin (1), Ladipo Solanke (West African Students Union), DN Pritt (2) and Harold Laski (1) 1 file 1940 – 1942

U DSF/2/5 File. ‘Historical pamphlets no.1. The struggle for a free press’ Ms. notes; ms. and ts. drafts of pamphlet by Ronald Kidd; letter from Elizabeth Acland Allen; published pamphlet, The press and the war (NCCL Press Freedom Committee, circa 1942) 1 file circa 1942

U DSF/2/6 File. Miscellaneous papers Bundle of cards left at Ronald Kidd’s graveside; letter from Kidd to Sylvia Crowther-Smith from Bratislava (16 August 1938); correspondence, reports and recommendations about Ronald Kidd’s retirement as General Secretary and appointment as Director of NCCL, and about the question of a new president. Includes letters from DN Pritt (2), Elizabeth Acland Allen (4), Henry Miller (Secretary, Cambuslang Branch of National Unemployed Workers Movement) (1), Kingsley Martin (1) and Mary Kidd (1) 1 file 1938 - 1942

U DSF/2/7 Letters and statement about Ronald Kidd’s health 3 items 1941

U DSF/2/8 Ts. copies of press notices and obituaries of Ronald Kidd after his death on 12/05/1942 1 bundle 1942

U DSF/2/9 Pocket diaries (with details of meetings and appointments) 4 volumes 1934 - 1938

U DSF/2/10 Passport of Ronald Kidd, with one spare photograph 2 items 11 Mar 1936

U DSF/2/11 Black and white photographs of Ronald Kidd, including one signed 7 items mid 20th cent

U DSF/2/12 Bound ts. script of play, ‘The lost leader’, by Lennox Robinson 1 item 1930s

U DSF/2/13 Publicity leaflet for the Soho Literary Group, organised by Ronald Kidd mid 20th cent

U DSF/2/14 Black and white photographs of political posters on display in wartime France 3 items 1940s

U DSF/2/15 Postcards a) Map of the Mediterranean, showing Italian plans for regional domination, with text on reverse about Spanish Civil War, no date b) ‘Forces de paix et forces de guerre’ [comparative chart], no date c) Display on agriculture at the Spanish pavilion, 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, Paris, 1937 d) ‘No pasaran!’, issued by the Propaganda Commissariat, Autonomous Government of Catalonia, 1937 4 items 1930s

U DSF/3 Sylvia Scaffardi (nee Crowther-Smith) 1930s - 1975

U DSF/3/1 Bundle. Committee on Land Utilisation for Rural Areas, Ministry of Works and Buildings (Lord Justice Scott’s Committee) Evidence submitted by Association of British Chambers of Commerce, County Councils Association, Pennine Way Association, Mr SW Smedley, Bolton Chamber of Commerce, Garden Cities and Town Planning Association, Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree and the Ramblers Association; related pamphlets; minutes of Executive Committee of County Councils Association (28.1.1942); report of Committee (Cmd. 6378) 1 bundle 1939 – 1942

U DSF/3/2 File of photocopied press cuttings about fascism in the 1930s Collected for Fire under the carpet (1986) 1 file 1930s

U DSF/3/3 Ts. annotated talk, ‘Childhood in Brazil’ With letters (2) from Olivia Chalmers about the Brazilian origins of Sylvia Scaffardi’s grandparents 3 items 1973

U DSF/3/4 Ms. and ts. notes about Robert Skidelsky’s 'Oswald Mosley' (Macmillan) 1 item 1975

U DSF/4 Barry Cox 1965 - 1971

U DSF/4/1 File. Correspondence of Barry Cox setting up interviews with key figures in the NCCL Including letters from DN Pritt (2), Tony Smythe (1), AP Herbert (1), Julian Huxley (1), PMS Blackett (1), Kingsley Martin (1), JB Priestley (1), EM Forster (2), Sylvia Scaffardi (2), Ritchie Calder (1) and John Platts-Mills (1). With cc. ts. agreement between Cox and the NCCL to produce a manuscript history of the organisation, and ms. notes 1 file 1968 – 1971

U DSF/4/2 File. Ts. transcripts of interviews undertaken by Barry Cox of key figures in the NCCL Including Neil Lawson, Elizabeth Acland Allen, DN Pritt, Geoffrey Bing, Kingsley Martin, Claud Cockburn, Sylvia Scaffardi, George Catlin, Malcolm Purdie and [?] Adams 1 file late 1960s

U DSF/4/3 File. Ts. transcripts of interviews undertaken by Barry Cox of key figures in the NCCL Including Dingle Foot, DN Pritt, Geoffrey Bing, Kingsley Martin (with comments by Sylvia Scaffardi), Claud Cockburn, Sylvia Scaffardi and Martin Ennals. Also ts. ‘Ronald Kidd’s politics. Political standing of NCCL up to 1941. Red smear’ and transcripts of letters from Kingsley Martin and EM Forster 1 file late 1960s

U DSF/4/4 Bundle of ts. transcripts and ms. notes of interviews undertaken by Barry Cox of key figures in the NCCL Including Tony Smythe, Martin Ennals, Kingsley Martin, Harry Street and David Williams. Also ms. notes on miscellaneous topics and annotated ts. paper by Tony Smythe on ‘The role of the NCCL’, at a symposium on direct action and democratic representation 1 bundle late 1960s

U DSF/4/5 File. Race relations/racial equality NCCL bulletins, circulars and letters; photocopies, cuttings and offprints of journal articles; quarterly bulletin of Race Relations Board; details of legal cases under section 6: incitement to racial hatred, of Race Relations Act 1965 (compiled by Anthony Dickey); ms. notes 1 file 1965 – 1971

U DSF/5 Pamphlets and periodicals by other organisations c1910 - 1978

U DSF/5/1 Pamphlet. Ronald Kidd, For freedom’s cause: an appeal to working men (Women’s Social and Political Union) 1 item c 1910

U DSF/5/2 The English Review, edited by Austin Harrison Includes part 5 of ‘The world set free: a story of mankind’, by HG Wells 1 item Apr 1914

U DSF/5/3 Monica Ewer, ts. ‘Civil liberties 1918’ (Record Office, National Council for Civil Liberties), with photocopy 2 items Jan 1918

U DSF/5/4 The immortal hour: music-drama by Rutland Broughton…from the play and poems of Fiona Macleod 1 item c 1923

U DSF/5/5 Pamphlet. GDH Cole, William Cobbett (Fabian Tract no.215) 1 item 1925

U DSF/5/6 Ashley Dukes, The acting edition of The Man with a Load of Mischief: a comedy in three acts 1 item 1926

U DSF/5/7 Germinal (literary magazine), no.2, edited by Sylvia Pankhurst 1 item 1924

U DSF/5/8 Pamphlet. Harold Laski, Socialism and freedom (Fabian Tract no.216) 1 item 1930

U DSF/5/9 Pamphlet. Lord Hewart of Bury, Law, ethics and legislation (BBC) 1 item 1930

U DSF/5/10 Pamphlet. A national policy: an account of the emergency policy advanced by Sir Oswald Mosley MP (Macmillan) 1 item 1931

U DSF/5/11 Pamphlet. To fascism or communism? (Communist Party of Great Britain) 1 item 1931

U DSF/5/12 Pamphlet. Douglas Goldring, Liberty and licensing (Hobby-Horse series no.1) 1 item 1932

U DSF/5/13 Pamphlet. The secret international. Armament firms at work (Union of Democratic Control) 1 item 1932 U DSF/5/14 The Golden Bowl (an occasional magazine devoted to the restoration of human values), no.7 1 item 1932 - 1933

U DSF/5/15 Pamphlet. CLR James, The case for West- Indian self government (Day to Day Pamphlets no.16 - Leonard and Virginia Woolf) 1 item 1933

U DSF/5/16 Pamphlet. TA Innes & Ivor Castle, Covenants with death (Daily Express) 1 item 1934

U DSF/5/17 Pamphlet. A souvenir of the Great Empire Air Day of 1934 (Union of Democratic Control) 1 item 1934

U DSF/5/18 Pamphlet. The Prudential and its money (Labour Research Department) 1 item 1934

U DSF/5/19 Pamphlet. Ivor Montagu, Blackshirt brutality: the story of Olympia 1 item 1934

U DSF/5/20 Pamphlet. ‘Vindicator’, Fascists at Olympia. A record of eye-witnesses and victims (Victor Gollancz Ltd.) 1 item 1934

U DSF/5/21 Life and letters. The Florin magazine 1 item May 1934

U DSF/5/22 Pamphlet. P Glading, How Bedaux works (Labour Research Department) 1 item Nov 1934

U DSF/5/23 Pamphlet. G Bernard Shaw, HG Wells, JM Keynes & Ernst Toller, Stalin-Wells talk The verbatim record and a discussion (New Statesman and Nation) 1 item Dec 1934

U DSF/5/24 Pamphlet. Ten points against fascism (Young Communist League) 1 item c 1934

U DSF/5/25 Pamphlet. W Fox, Taximen and taxi-owners (Labour Research Department) 1 item Feb 1935

U DSF/5/26 Left Review (5 issues) 5 items Mar 1935 - Feb 1937

U DSF/5/27 Artists International Association, Bulletin, no. 10 With circular about attempt to form a new association affiliated to the International of Revolutionary Writers 2 items Nov 1935

U DSF/5/28 Pamphlet. DN Pritt, The Zinoviev trial (Victor Gollancz Ltd.) 1 item 1936

U DSF/5/29 Pamphlet. Sean Murray, The Irish revolt: 1916 and after (Communist Party of Great Britain) 1 item 1936

U DSF/5/30 Pamphlet. Herbert Read, Essential Communism (Pamphlets on the New Economics series no.12) Social Credit publication 1 item Apr 1936

U DSF/5/31 Pamphlet. The trial of Luiz Carlos Prestes (Association Juridique Internationale) 1 item c 1936

U DSF/5/32 Pamphlet. The case for Cyprus (Committee for the Autonomy of Cyprus) 1 item c 1937

U DSF/5/33 Book. Elvira Bauer, Trau keinen Fuchs auf grüner Heid und keinen Jud bei seinem Eid: ein Bilderbuch für gross und klein (Stürmer Publishing House, Nuremberg, 1936) Anti-Semitic publication, with ts. English translation, stamped ‘National Council for Civil Liberties’, January 1937 2 items 1936 - Jan 1937

U DSF/5/34 Book. A Ramos Oliveira, La lucha del pueblo Espanol por su libertad (Spanish Embassy, London) 1 volume 1937

U DSF/5/35 Book. A Ramos Oliveira, Work and War in Spain (Spanish Embassy, London) 1 volume 1938

U DSF/5/36 Pamphlet. Czechoslovakia – a deserted nation. A woman writes ‘Goodbye’ (News Chronicle Czech Relief Fund) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/37 Pamphlet. The facts. Czechoslovakia’s martyrdom (European Association and League of Nations Union, 1938) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/38 Miscellaneous no.7 (1938). Correspondence respecting Czechoslovakia September 1938 (Cmd. 5847) (HMSO) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/39 Miscellaneous no.8 (1938). Further documents respecting Czechoslovakia including the agreement concluded at Munich on September 29, 1938 (Cmd. 5848) (HMSO) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/40 Pamphlet. Writers declare against fascism (Association of Writers for Intellectual Liberty) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/41 Pamphlet. How the rich live: sidelights on the Cunningham Reid case (Communist Party of Great Britain) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/42 Pamphlet. Eternal vigilance. The story of civil liberty 1937-1938 (American Civil Liberties Union) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/43 Pamphlet. RST Chorley, The threat to civil liberty (Haldane Society) 1 item 1938

U DSF/5/44 Book. Dr Hans Diebow ed., Der ewige Jude (Zentralverlag der NSDAP) Anti-Semitic publication issued by the Nazi Party 1 volume 1938

U DSF/5/45 Pamphlet. Hands off the Protectorates (International African Service Bureau) 1 item c 1938 Hull History Centre: Papers of Sylvia Scaffardi page 19 of 21

U DSF/5/46 Pamphlet. Kingsley Martin, Fascism, democracy and the press (New Statesman) 1 item c 1939

U DSF/5/47 Pamphlet. Eric Gill, All that England stands for (Peace Pledge Union) 1 item post 1939

U DSF/5/48 The British Subject, vol.I, no.5 1 item Feb 1940

U DSF/5/49 Pamphlet. Native races, the war and peace aims (Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society) With covering letter 2 items Mar 1940

U DSF/5/50 Pamphlet. Barbed wire in France. They fought for freedom. Their reward – concentration camps (International Brigade Association) 1 item early 1940

U DSF/5/51 Pamphlet. Where are you going? An open letter to Communists by Victor Gollancz 1 item 9 May 1940

U DSF/5/52 Pamphlet. U DMWP [?], France faces fascism (Fabian Society Research Series no.52) 1 item Oct 1940

U DSF/5/53 Pamphlet. Why France fell: the lessons for us (Union of Democratic Control) 1 item c1940

U DSF/5/54 Pamphlet. Morrison’s prisoners. The story of the Czechoslovakian anti-fascist fighters interned in Britain (National Council for Democratic Aid) 1 item 1941

U DSF/5/55 Pamphlet. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The strength of our ally (Lawrence and Wishart) 1 item c1941

U DSF/5/56 Pamphlet. The Anglo-Soviet Treaty 26 May 1942 (Society for Cultural Relations with the Soviet Union) 1 item 1942

U DSF/5/57 Pamphlet. Who’s who in Nazi Germany (British government publication) [copy no.14] 1 item 15 Dec 1942

U DSF/5/58 Pamphlet. A pocket guide to India (United States War and Navy Departments) 1 item c 1942

U DSF/5/59 Art and Industry (2 issues) 2 items Jul - Aug 1943

U DSF/5/60 Pamphlet. André Marty, L’heure de la France a sonné (Communist Party of Great Britain) 1 item c 1943

U DSF/5/61 Pamphlet. For Liberty Exhibition. Exhibition of paintings by members of the AIA 1 item c 1943

U DSF/5/62 Pamphlet. Robert E Cushman, Our constitutional freedoms. Civil liberties: an American heritage (National Foundation for Education in American Citizenship) 1 item Jan 1944

U DSF/5/63 Central Board for Conscientious Objectors, Bulletin, no.55 1 item Sep 1944

U DSF/5/64 Britânia, vol.I, nos. III, V & VII 3 items Sep 1944 - Jan 1945

U DSF/5/65 Pamphlet. John Price, British trade unions and the war (Ministry of Information) 1 item 1945

U DSF/5/66 Pamphlet. Town planning and housing. What can I do? (Town and Country Planning Association) 1 item 1945

U DSF/5/67 Choix: les écrits du mois à travers le monde, no.11 1 item Dec 1945

U DSF/5/68 Greek News, vol.1, no.7 (League for Democracy in Greece) 1 item Sep 1946

U DSF/5/69 Civil Rights, vol.1, nos. 1 & 2 (Emergency Committee for Civil Liberty, Canada) 2 items 15 Aug - 15 Sep 1946

U DSF/5/70 Pamphlet. Ashwin Choudree & PR Pather, A commentary on the Asiatic land tenure and Indian Representation Act (South African Congress) 1 item 1 May 1946

U DSF/5/71 Écho Revue Internationale: écrits, faits et idées de tous pays 1 item Jun 1947

U DSF/5/72 Pamphlet. Dalton Trumbo, The time of the toad: a study of the inquisition in America (The Hollywood Ten) 1 item 1949

U DSF/5/73 Pamphlet. Discrimination: a study in injustice to a minority (All Party Anti-Partition Conference, Dublin) 1 item c. 1950

U DSF/5/74 Pamphlet. Bertrand Russell, How near is war? (Derricke Ridway) 1 item 1952

U DSF/5/75 Pamphlet. Seretse Khama and the Bamangwato people (Seretse Khama Campaign Committee) 1 item c 1952

U DSF/5/76 Pamphlet. Kenneth Kaunda, Dominion status for Central Africa? (Union of Democratic Control/Movement for Colonial Freedom) 1 item c 1959

U DSF/5/77 Pamphlet. The Black Paper. Report to the nation: H bomb war (Peace News) 1 item 1960s

U DSF/5/78 Pamphlet. This is apartheid (International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa) 1 item 1978

U DSF/5/79 Bundle of photocopies of extracts from pamphlets and books relating to fascism, antifascism and the 1930s in Britain Including from Phil Piratin’s Our flag stays red, They did not pass: A souvenir of the East London workers’ victory over fascism (Independent Labour Party), The BUF by the BUF (Communist Party of Great Britain) and Tom Driberg’s Mosley? No! 1 bundle late 20th cent.