Part 2 of 2

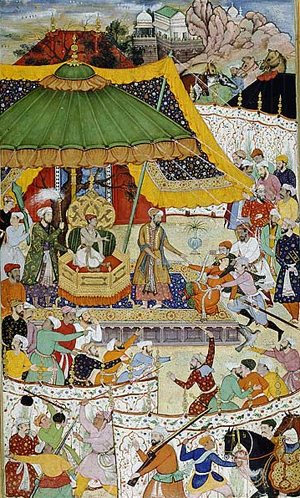

SikhismIn Sikhism, the Hindu god Rama has been referred to as Sri Ram Chandar, and the story of Hanuman as a siddha has been influential. After the birth of the martial Sikh Khalsa movement in 1699, during the 18th and 19th centuries, Hanuman was an inspiration and object of reverence by the Khalsa. Some Khalsa regiments brought along the Hanuman image to the battleground. The Sikh texts such as Hanuman Natak composed by Hirda Ram Bhalla, and Das Gur Katha by Kavi Kankan describe the heroic deeds of Hanuman.[85] According to Louis Fenech, the Sikh tradition states that Guru Gobind Singh was a fond reader of the Hanuman Natak text.

During the colonial era, in Sikh seminaries in what is now Pakistan, Sikh teachers were called bhai, and they were required to study the Hanuman Natak, the Hanuman story containing Ramcharitmanas and other texts, all of which were available in Gurmukhi script.[86]

Bhagat Kabir, a prominent writer of the scripture explicitly states that the being like Hanuman does not know the full glory of the divine. This statement is in the context of the Divine as being unlimited and ever expanding. Ananta is therefore a name of the divine. In sanskrit language anta means end. The prefix An is added to create the word Ananta (without end or unlimited).

ਹਨੂਮਾਨ ਸਰਿ ਗਰੁੜ ਸਮਾਨਾਂ

Hanūmān sar garuṛ samānāʼn.

Beings like Hanumaan, Garura,

ਸੁਰਪਤਿ ਨਰਪਤਿ ਨਹੀ ਗੁਨ ਜਾਨਾਂ Surpaṯ narpaṯ nahī gun jānāʼn.

Indra the King of the gods and the rulers of humans – none of them know Your Glories, Lord.

— Sri Guru Granth Sahib page 691 Full Shabad

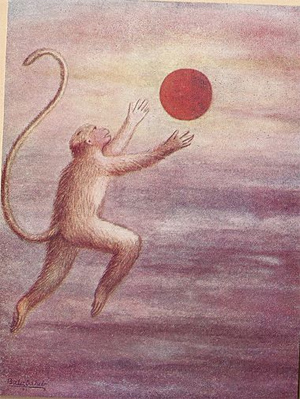

Southeast Asian textsThere exist non-Indian versions of the Ramayana, such as the Thai Ramakien. According to these versions of the Ramayana, Macchanu is the son of Hanuman borne by Suvannamaccha, when "Hanuman fly over Lanka after firing Ravana palace, his body with extreme heat & a drop of his sweat fall into sea it eaten by a mighty fish when he bathing and she birth to macchanu" daughter of Ravana.

Another legend says that a demigod named Matsyaraja (also known as Makardhwaja or Matsyagarbha) claimed to be his son. Matsyaraja's birth is explained as follows: a fish (matsya) was impregnated by the drops of Hanuman's sweat, while he was bathing in the ocean.[29]

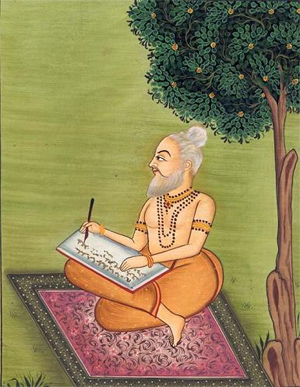

Hanuman in southeast Asian texts differs from the north Indian Hindu version in various ways in the Burmese Ramayana, such as Rama Yagan, Alaung Rama Thagyin (in the Arakanese dialect), Rama Vatthu and Rama Thagyin, the Malay Ramayana, such as Hikayat Sri Rama and Hikayat Maharaja Ravana, and the Thai Ramayana, such as Ramakien. However, in some cases, the aspects of the story are similar to Hindu versions and Buddhist versions of Ramayana found elsewhere on the Indian subcontinent. Valmiki Ramayana is the original holy text; others are edited versions by the poets for performing Arts like folk dances, the true story of Ramayana is Valmikis, Sage Valmiki known as the Adikavi "the first poet".

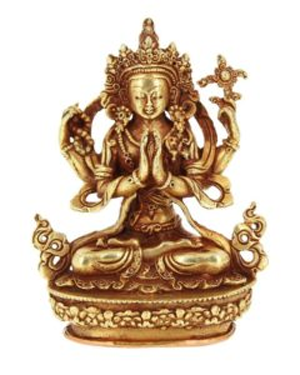

Significance and influence Hanuman murti seated in meditation in lotus asana

Hanuman murti seated in meditation in lotus asanaHanuman became more important in the medieval period and came to be portrayed as the ideal devotee (bhakta) of Rama.[29] Hanuman's life, devotion, and strength inspired wrestlers in India.[87]

According to Philip Lutgendorf, devotionalism to Hanuman and his theological significance emerged long after the composition of the Ramayana, in the 2nd millennium CE. His prominence grew after the arrival of Islamic rule in the Indian subcontinent.[8] He is viewed as the ideal combination of shakti ("strength, heroic initiative and assertive excellence") and bhakti ("loving, emotional devotion to his personal god Rama").[13] Beyond wrestlers, he has been the patron god of other martial arts. He is stated to be a gifted grammarian, meditating yogi and diligent scholar. He exemplifies the human excellences of temperance, faith and service to a cause.[12][14][15]

"Greater than Ram is Ram's servant."

– Tulsidas, Ramcharitmanas 7.120.14[88]

In 17th-century north and western regions of India, Hanuman emerged as an expression of resistance and dedication against Islamic persecution. For example, the bhakti poet-saint Ramdas presented Hanuman as a symbol of Marathi nationalism and resistance to Mughal Empire.[10]

Hanuman in the colonial and post-colonial era has been a cultural icon, as a symbolic ideal combination of shakti and bhakti, as a right of Hindu people to express and pursue their forms of spirituality and religious beliefs (dharma).[13][89] Political and religious organizations have named themselves after him or his synonyms such as Bajrang.[90][40][41] Political parades or religious processions have featured men dressed up as Hanuman, along with women dressed up as gopis (milkmaids) of god Krishna, as an expression of their pride and right to their heritage, culture and religious beliefs.[91][92] According to some scholars, the Hanuman-linked youth organizations have tended to have a paramilitary wing and have opposed other religions, with a mission of resisting the "evil eyes of Islam, Christianity and Communism", or as a symbol of Hindu nationalism.[93][94]In Hindu astrology, Saturn or Shani is a dreaded planet whose transit in the constellation before the natal moon, over the natal moon and in the constellation subsequent to the natal moon is considered to be a very tough period for a person, referred to as Sadesati. It is believed that Hanuman and Ganesha are the two deities whose worship leads to a reduction in the malefic influence of planets. People worship Hanuman as an astrological remedy to pacify the disastrous effects of a badly placed Saturn. This is done by preparing offerings made of urad dal, peppered with sugar, called jalebi or peppered with salt and pepper, called vadai, stringing it and offering this as an edible garland of sorts to Hanuman on Saturdays (South India) or Tuesdays (North India). Offerings of sesame oil are also made to Hanuman. The same goes for offerings of butter. The origins of offering butter to Hanuman are found in the Ramayana where, it is said that Rama applied butter as a balm on Hanuman's wounds to help heal from the wounds of the war with Ravana.

The offering of sesame oil has its origins from the Saturnian quality of extreme hard work with no expectations of any results for foreseeable time, such as the tenacity exhibited by a mountain goat and which tenacity is also needed to extract oil from sesame seeds. In the old days, this oil extraction was done by hand and was considered akin to the kind of effort one needs to put in one's tasks and day to day life, to get through the malefic phases of Saturn.

Iconography A five-headed panchamukha Hanuman icon. It is found in esoteric tantric traditions that weave Vaishvana and Shaiva ideas, and is relatively uncommon.[95][96]

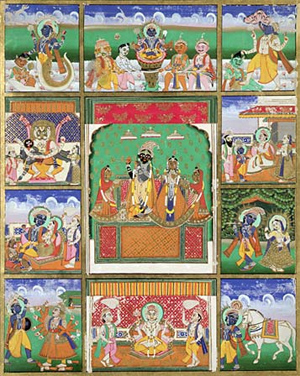

A five-headed panchamukha Hanuman icon. It is found in esoteric tantric traditions that weave Vaishvana and Shaiva ideas, and is relatively uncommon.[95][96]Hanuman's iconography shows him either with other central characters of the Ramayana or by himself. If with Rama and Sita, he is shown to the right of Rama, as a devotee bowing or kneeling before them with a Namaste (Anjali Hasta) posture. If alone, he carries weapons such as a big Gada (mace) and thunderbolt (vajra), sometimes in a scene reminiscent of his life.[2][97]

His iconography and temples are common today. He is typically shown with Rama, Sita and Lakshmana, near or in Vaishnavism temples, as well as by himself usually opening his chest to symbolically show images of Rama and Sita near his heart. He is also popular among the followers of Shaivism.[12]

In north India, aniconic representation of Hanuman such as a round stone has been in use by yogi, as a means to help focus on the abstract aspects of him.[98]

He is also shown carrying a saffron flag in service of the Goddess Durga along with Bhairav

Temples and shrines 41 meters (135 ft) high Hanuman monument at Paritala, Andhra Pradesh

41 meters (135 ft) high Hanuman monument at Paritala, Andhra Pradesh Panchmukhi Hanuman Temple in Karachi, Pakistan is the only temple in the world which has a natural statue of Hanuman

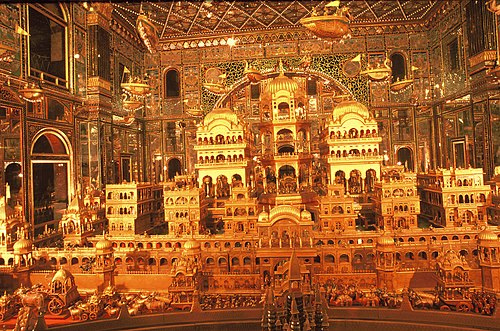

Panchmukhi Hanuman Temple in Karachi, Pakistan is the only temple in the world which has a natural statue of HanumanHanuman is often worshipped along with Rama and Sita of Vaishnavism, and sometimes independently of them.[21] There are numerous statues to celebrate or temples to worship Hanuman all over India. Author Vanamali says, "Vaishnavites or followers of Vishnu, believe that the wind god Vayu underwent three incarnations to help Lord Vishnu. As Hanuman he helped Rama, as Bhima, he assisted Krishna, and as Madhvacharya (1238 - 1317) he founded the Vaishnava sect called Dvaita".[99] Shivites claim him as an avatar of Shiva.[21] Indologist Philip Lutgendorf writes, "The later identification of Hanuman as one of the eleven rudras may reflect a Shaiva sectarian claim on an increasing popular god, it also suggests his kinship with, and hence potential control over, a class of awesome and ambivalent deities". Lutgendorf also writes, "Other skills in Hanuman's resume also seem to derive in part from his windy patrimony, reflecting Vayu's role in both body and cosmos".[11] According to a review by Lutgendorf,

some scholars state that the earliest Hanuman murtis appeared in the 8th century, but verifiable evidence of Hanuman images and inscriptions appear in the 10th century in Indian monasteries in central and north India.[100]

Wall carvings depicting the worship of Hanuman at Undavalli Caves in Guntur District.

Wall carvings depicting the worship of Hanuman at Undavalli Caves in Guntur District.Tuesday and Saturday of every week are particularly popular days at Hanuman temples. Some people keep a partial or full fast on either of those two days and remember Hanuman and the theology he represents to them.[101]

Major temples and shrines of Hanuman include:

• The oldest known independent Hanuman temple and statue is at Khajuraho, dated to about 922 CE from the Khajuraho Hanuman inscription.[102][103]

• Mahavir Mandir is one of the holiest Hindu temples dedicated to Hanuman, located in Patna, Bihar, India.

• Bajrang bali Hanuman temple - Lakdikapool, Hyderabad.

• Hanumangarhi, Ayodhya, is a 10th century temple dedicated to Hanuman.[104]

• Shri Panchmukhi Hanuman Mandir is a 1,500-year-old temple in Pakistan. It is located in Soldier Bazaar in Karachi, Pakistan.The temple is highly venerated by Pakistani Hindus as it is the only temple in the world which has a natural statue of Hanuman that is not man-made(Swayambhu).[105][106]

• Jakhu temple in Shimla, the capital of Himachal Pradesh. A monumental 108-foot (33-metre) statue of Hanuman marks his temple and is the highest point in Shimla.[107]

• The tallest Hanuman statue is the Veera Abhaya Anjaneya Swami, standing 135 feet tall at Paritala, 32 km from Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh, installed in 2003.[108]

• Chitrakoot in Madhya Pradesh features the Hanuman Dhara temple, which features a panchmukhi statue of Hanuman. It is located inside a forest, and it along with Ramghat that is a few kilometers away, are significant Hindu pilgrimage sites.[109]

• The Peshwa era rulers in 18th century city of Pune provided endowments to more Maruti temples than to temples of other deities such as Shiva, Ganesh or Vitthal.Even in present time there are more Maruti temples in the city and the district than of other deities.[110]

• Other monumental statues of Hanuman are found all over India, such as at the Sholinghur Sri Yoga Narasimha swami temple and Sri Yoga Anjaneyar temple, located in Vellore District. In Maharashtra, a monumental statue is at Nerul, Navi Mumbai. In Bangalore, a major Hanuman statue is at the Ragigudda Anjaneya temple. Similarly, a 32 feet (10 m) idol with a temple exists at Nanganallur in Chennai. At the Hanuman Vatika in Rourkela, Odisha there is 75-foot (23 m) statue of Hanuman.[111]

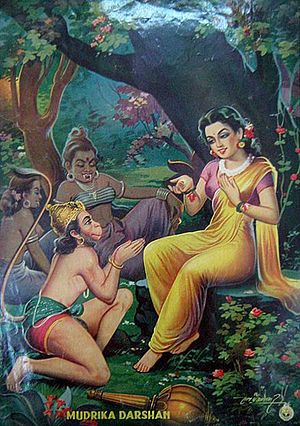

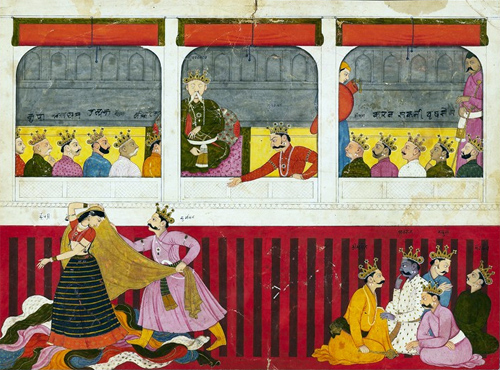

In India, the annual autumn season Ramlila play features Hanuman, enacted during Navratri by rural artists (above).

In India, the annual autumn season Ramlila play features Hanuman, enacted during Navratri by rural artists (above).• Outside India, a major Hanuman statue has been built by Tamil Hindus near the Batu caves in Malaysia, and an 85-foot (26 m) Karya Siddhi Hanuman statue by colonial era Hindu indentured workers' descendants at Carapichaima in Trinidad and Tobago. Another Karya Siddhi Hanuman Temple has been built in Frisco, Texas in the United States.[112]

• Panchamukhi is a very famous place near Mantralayam in Andhrapradesh where famous Dvaita saint Sri Raghavendra swamy spent for many years. Here Hanuman statue will be depicted with five faces primarily face of hanuman himself, Garuda, Varaha, Narasimha, Hayagreeva

• 732 Hanuman deities were installed by Sri Vyasa raya Teertha 15th century philosopher and Dvaita saint, Guru of Sri Purandra dasa, Sri Kanaka Dasa and Sri krishna Devaraya.

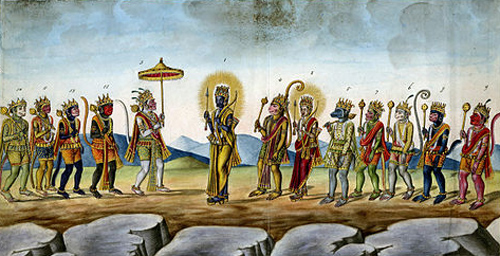

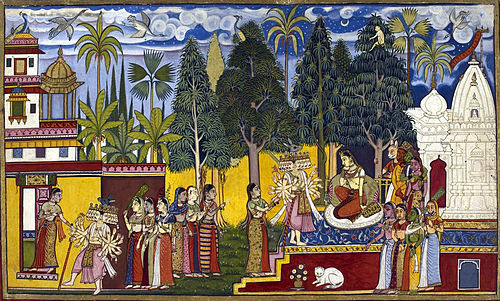

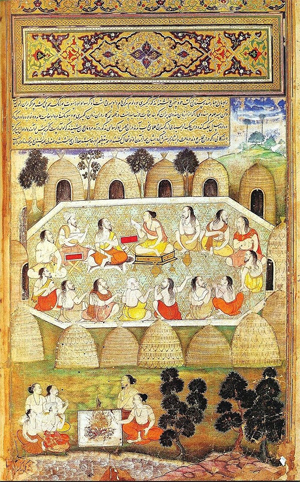

Festivals and celebrationsHanuman is a central character in the annual Ramlila celebrations in India, and seasonal dramatic arts in southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand; and Bali and Java, Indonesia. Ramlila is a dramatic folk re-enactment of the life of Rama according to the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana or secondary literature based on it such as the Ramcharitmanas.[113] It particularly refers to the thousands[114] of dramatic plays and dance events that are staged during the annual autumn festival of Navratri in India.[115] Hanuman is featured in many parts of the folk-enacted play of the legendary war between Good and Evil, with the celebrations climaxing in the Dussehra (Dasara, Vijayadashami) night festivities where the giant grotesque effigies of Evil such as of demon Ravana are burnt, typically with fireworks.[116][117]

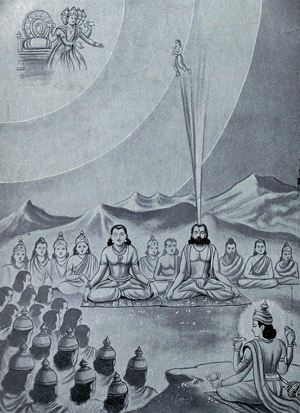

The Ramlila festivities were declared by UNESCO as one of the "Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity" in 2008. Ramlila is particularly notable in the historically important Hindu cities of Ayodhya, Varanasi, Vrindavan, Almora, Satna and Madhubani – cities in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh.[116]

Hanuman's birthday is observed by some Hindus as Hanuman Jayanti. It falls in much of India in the traditional month of Chaitra in the lunisolar Hindu calendar, which overlaps with March and April. However, in parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, Hanuman Jayanthi is observed in the regional Hindu month of Margazhi, which overlaps with December and January. The festive day is observed with devotees gathering at Hanuman temples before sunrise, and day long spiritual recitations and story reading about the victory of good over evil.[7]

Hanuman in Southeast Asia

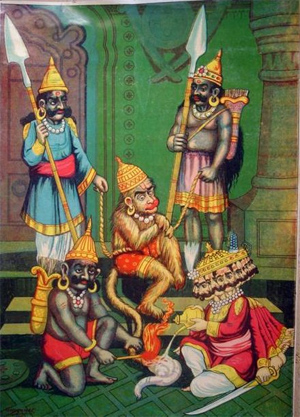

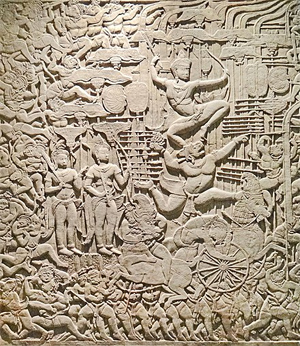

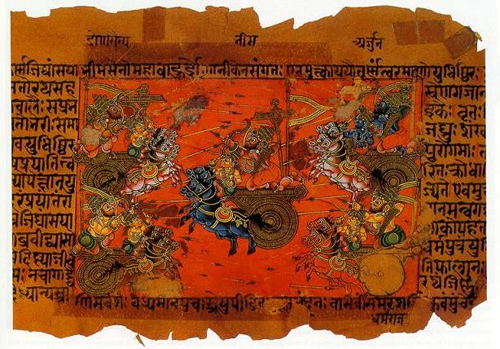

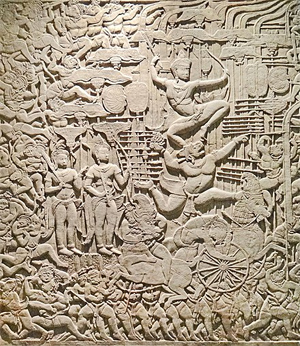

Cambodia Cambodian depiction of Hanuman at Angkor Wat. Rama is standing on top of Hanuman in the middle of the mural.

Cambodian depiction of Hanuman at Angkor Wat. Rama is standing on top of Hanuman in the middle of the mural.Hanuman is a revered heroic figure in Khmer history in southeast Asia. He features predominantly in the Reamker, a Cambodian epic poem, based on the Sanskrit Itihasa Ramayana epic.[118] Intricate carvings on the walls of Angkor Wat depict scenes from the Ramayana including those of Hanuman.[119]

Hanuman statue at Bali, Indonesia

Hanuman statue at Bali, IndonesiaIn Cambodia and many other parts of southeast Asia, mask dance and shadow theatre arts celebrate Hanuman with Ream (same as Rama of India). Hanuman is represented by a white mask.[120][121] Particularly popular in southeast Asian theatre are Hanuman's accomplishments as a martial artist Ramayana.[122]

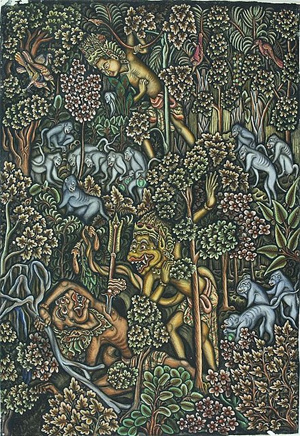

IndonesiaHanuman is the central character in many of the historic dance and drama art works such as Wayang Wong found in Javanese culture, Indonesia. These performance arts can be traced to at least the 10th century.[123] He has been popular, along with the local versions of Ramayana in other islands of Indonesia such as Java.[124][125]

In major medieval era Hindu temples, archeological sites and manuscripts discovered in Indonesian and Malay islands, Hanuman features prominently along with Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Vishvamitra and Sugriva.[126][127] The most studied and detailed relief artworks are found in the Candis Panataran and Prambanan.[128][129]

Hanuman, along with other characters of the Ramayana, are an important source of plays and dance theatre repertoire at Odalan celebrations and other festivals in Bali.[130]

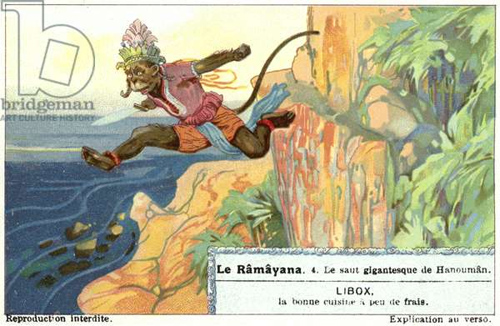

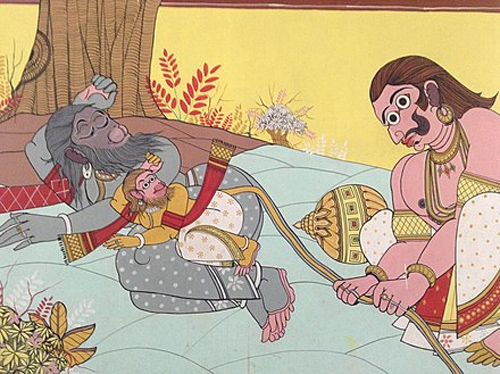

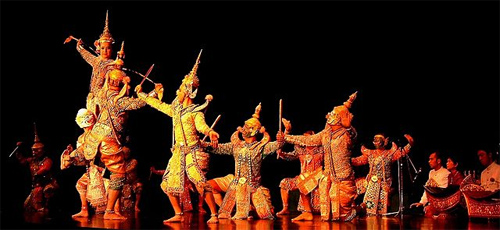

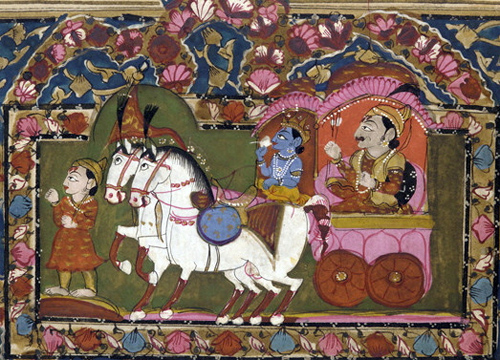

Thailand Thai iconography of Hanuman. He is one of the most popular characters in the Ramakien.[131]

Thai iconography of Hanuman. He is one of the most popular characters in the Ramakien.[131]Hanuman plays a significantly more prominent role in the Ramakien.[132] In contrast to the strict devoted lifestyle to Lord Rama of his Indian counterpart, Hanuman is known in Thailand as a promiscuous and flirtatious character.[133] One famous episode of the Ramakien has him fall in love with the mermaid Suvannamaccha and fathering Macchanu with her. In another, Hanuman takes on the form of Ravana and sleeps with Mandodari, Ravana's consort, thus destroying her chastity, which was the last protection for Ravana's life.[134]

As in the Indian tradition, Hanuman is the patron of martial arts and an example of courage, fortitude and excellence in Thailand.[135] He is depicted as wearing a crown on his head and armor. He is depicted as an albino white, strong character with open mouth in action, sometimes shown carrying a trident.

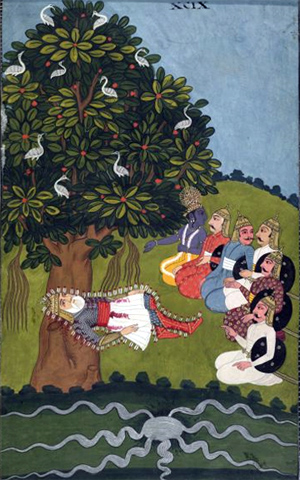

LineageThough Hanuman is described to be celibate in the Ramayana and most of the Puranas, according to some regional sources, Hanuman married Suvarchala, the daughter of Surya (Sun-God).[136]

However, once Hanuman was flying above the seas to go to Lanka, a drop of his sweat fell in the mouth of a crocodile, which eventually turned into a baby. The monkey baby was delivered by the crocodile, who was soon retrieved by Ahiravana, and raised by him, named Makardhwaja, and made the guard of the gates of Patala, the former's kingdom. One day, Hanuman, when going to save Rama and Lakshmana from Ahiravana, faced Makardhwaja and defeated him combat. Later, after knowing the reality and after saving both, he made his son, the king of Patala.The Jethwa clan claims to be a descendant of Makardhwaja, and, according to them, he had a son named Modh-dhwaja, who in turn had a son named Jeth-dhwaja, hence the name of the clan.

In pop cultureWhile Hanuman is a quintessential character of any movie on Ramayana, Hanuman centric movies have also been produced with Hanuman as the central character. In 1976 the first biopic movie on Hanuman was released with legendary wrestler Dara Singh playing the role of Hanuman. He again reprised the character in Ramanand Sagar's television series Ramayan and B. R. Chopra's Mahabharat.[137]

In 2005 an animated movie of the same name was released and was extremely popular among children. Actor Mukesh Khanna voiced the character of Hanuman in the film.[138] Following this several series of movies featuring the legendary God were produced though all of them were animated, prominent ones being the Bal Hanuman series 2006–2012. Another movie Maruti Mera dost (2009) was a contemporary adaptation of Hanuman in modern times.[139]

The 2015 Bollywood movie Bajrangi Bhaijaan had Salman Khan playing the role of Pawan Kumar Chaturvedi who is an ardent Hanuman devotee and regularly invokes him for his protection, courage, and strength.[140]

US president Barack Obama had a habit of carrying with him a few small items given to him by people he had met. The items included a small figurine of Hanuman.[141][142]

Hanuman was referenced in the 2018 Marvel Cinematic Universe film, Black Panther, which is set in the fictional African nation of Wakanda; the "Hanuman" reference was removed from the film in screenings in India.[143][144]

The Mexican acoustic-metal duo, Rodrigo Y Gabriela released a hit single named "Hanuman" from their album 11:11. Each song on the album was made to pay tribute to a different musician that inspired the band, and the song Hanuman is dedicated to Carlos Santana. Why the band used the name Hanuman is unclear, but the artists have stated that Santana "was a role model for musicians back in Mexico that it was possible to do great music and be an international musician."[145]

See also• Hanuman temples

• Vayu Stuti

• Hanuman Chalisa

• Hanuman Jayanti

• Hanumanasana, an asana named after Hanuman

• Sun Wukong, a Chinese literary character in Wu Cheng'en's masterpiece Journey to the West

• The 6 Ultra Brothers vs. the Monster Army

• Hanuman and the Five Riders

• Gray langur, also known as the Hanuman langur

References1. "Hanuman: A Symbol of Unity". 21 January 2021.

2. George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

3. Brian A. Hatcher (2015). Hinduism in the Modern World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-04630-9.

4. "Mahabharata's Bhima is related to Lord Hanuman – Here's how". Zee News. 25 May 2016.

5. Bibek Debroy (2012). The Mahabharata: Volume 3. Penguin Books. pp. 184 with footnote 686. ISBN 978-0-14-310015-7.

6. "Hanuman", Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

7. J. Gordon Melton; Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1310–1311. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

8. Paula Richman (2010), Review: Lutgendorf, Philip's Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey, The Journal of Asian Studies; Vol 69, Issue 4 (Nov 2010), pages 1287–1288

9. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 44.

10. Jayant Lele (1981). Tradition and Modernity in Bhakti Movements. Brill Academic. pp. 114–116. ISBN 978-90-04-06370-9.

11. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 67.

12. Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

13. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 26–32, 116, 257–259, 388–391.

14. Lutgendorf, Philip (1997). "Monkey in the Middle: The Status of Hanuman in Popular Hinduism". Religion. 27 (4): 311–332. doi:10.1006/reli.1997.0095.

15. Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–9. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

16. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 223, 309, 320.

17. Wendy Doniger, Hanuman: Hindu mythology, Encyclopaedia Britannica; For a summary of the Chinese text, see Xiyouji: NOVEL BY WU CHENG’EN

18. H. S. Walker (1998), Indigenous or Foreign? A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong[permanent dead link], Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 81. September 1998, Editor: Victor H. Mair, University of Pennsylvania

19. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 31–32.

20. Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 68.

21. Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

22. ऋग्वेद:_सूक्तं_१०.८६, Rigveda, Wikisource

23. Philip Lutgendorf (1999), Like Mother, Like Son, Sita and Hanuman, Manushi, No. 114, pages 23–25

24. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 39–40.

25. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 40.

26. Legend of Ram–Retold. PublishAmerica. 28 December 2012. pp. 56–. ISBN 978-1-4512-2350-7.

27. Philip Lutgendorf (1999), Like Mother, Like Son, Sita and Hanuman, Manushi, No. 114, pages 22–23

28. Nanditha Krishna (1 January 2010). Sacred Animals of India. Penguin Books India. pp. 178–. ISBN 978-0-14-306619-4.

29. Camille Bulcke; Dineśvara Prasāda (2010). Rāmakathā and Other Essays. Vani Prakashan. pp. 117–126. ISBN 978-93-5000-107-3. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

30. Swami Parmeshwaranand (2001). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas, Volume 1. Sarup & Sons. pp. 411–. ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

31. Diana L. Eck (1991). Devotion divine, Bhakti traditions from the regions of India: studies in honour of Charlotte Vaudeville. Egbert Forsten. pp. 69, 62–67. ISBN 978-90-6980-045-5., Quote: "Giving up his Rudra form, Lord Shiva as Hanuman adopted a monkey figure, only in view of his affection for Rama."

32. The Rigveda, with Dayananda Saraswati's Commentary, Volume 1. Sarvadeshik Arya Pratinidhi Sabha. 1974. p. 717. The third meaning of Rudra is Vayu or air that causes pain to the wicked on the account of their evil actions...... Vayu or air is called Rudra as it makes a person weep causing pain as a result of bad deeds .

33. Shanti Lal Nagar (1999). Genesis and evolution of the Rāma kathā in Indian art, thought, literature, and culture: from the earliest period to the modern times. B.R. Pub. Co. ISBN 978-81-7646-082-8. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

34. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 64–71.

35. Catherine Ludvik (1987). F.S. Growse (ed.). The Rāmāyaṇa of Tulasīdāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 723–725. ISBN 978-81-208-0205-6.

36. Patrick Peebles (2015). Voices of South Asia: Essential Readings from Antiquity to the Present. Routledge. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-317-45248-5.

37. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 85.

38. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 57–64.

39. Thomas A. Green (2001). Martial Arts of the World: En Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 467–468. ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2.

40. William R. Pinch (1996). Peasants and Monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 27–28, 64, 158–159. ISBN 978-0-520-91630-2.

41. Sarvepalli Gopal (1993). Anatomy of a Confrontation: Ayodhya and the Rise of Communal Politics in India. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 41–46, 135–137. ISBN 978-1-85649-050-4.

42. Philip Lutgendorf (2002), Evolving a monkey: Hanuman, poster art and postcolonial anxiety, Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol 36, Issue 1–2, pages 71–112

43. Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas Vol 2.(D-H) pp=628–631, Swami Parmeshwaranand, Sarup & Sons, 2001, ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3

44. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 249.

45. Deshpande, Chaitanya (22 April 2016). "Hanuman devotees to visit Anjaneri today - Times of India". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 16 April2021.

46. Bose, Mrityunjay (7 November 2020). "Maharashtra govt to develop Hanuman's birthplace Anjaneri". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 16 April2021.

47. Malagi, Shivakumar G. (20 December 2018). "At Hampi, fervour peaks at Hanuman's birthplace". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

48. "Anjaneya Hill". Retrieved 4 December 2020.

49. "Anjeyanadri Hill | Sightseeing Hampi | Hampi". Karnataka.com. 22 October 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

50. Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

51. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 188–189.

52. Pai, Anant (1978). Valmiki's Ramayana. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–96.

53. Pai, Anant (1971). Hanuman. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–32.

54. Chandrakant, Kamala (1980). Bheema and Hanuman. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–32.

55. Joginder Narula (1991). Hanuman, God and Epic Hero: The Origin and Growth of Hanuman in Indian Literary and Folk Tradition. Manohar Publications. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-81-85054-84-1.

56. Nityananda Misra. Mahaviri: Hanuman Chalisa Demystified. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

57. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 45–47, 287.

58. Goldman, Robert P. (Introduction, translation and annotation) (1996). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume V: Sundarakanda. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. 0691066620. pp. 45–47.

59. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 6, 44–45, 205–210.

60. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 61.

61. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 140–141, 201.

62. Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

63. A Kapoor (1995). Gilbert Pollet (ed.). Indian Epic Values: Rāmāyaṇa and Its Impact. Peeters Publishers. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-90-6831-701-5.

64. Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 100–107. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

65. Catherine Ludvik (1987). F.S. Growse (ed.). The Rāmāyaṇa of Tulasīdāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 723–728. ISBN 978-81-208-0205-6.

66. Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

67. Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 509–511. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

68. Dallapiccola, A.L.; Verghese, Anila (2002). "Narrative Reliefs of Bhima and Purushamriga at Vijayanagara". South Asian Studies. 18 (1): 73–76. doi:10.1080/02666030.2002.9628609. S2CID 191646631.

69. J. A. B. van Buitenen (1973). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 180, 371, 501–505. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

70. Diana L. Eck (1991). Devotion divine: Bhakti traditions from the regions of India : studies in honour of Charlotte Vaudeville. Egbert Forsten. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-6980-045-5. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

71. Catherine Ludvík (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarasidas publ. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

72. Mystery of Hanuman - Inspiring Tales from Art and Mythology The Story of Ahiravan Vadh - Hanuman Saves Lord

73. Susan Whitfield; Ursula Sims-Williams (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

74. J. L. Brockington (1985). Righteous Rāma: The Evolution of an Epic. Oxford University Press. pp. 264–267, 283–284, 300–303, 312 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-19-815463-1.

75. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 353–354.

76. Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney (1989). The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual. Princeton University Press. pp. 42–54. ISBN 978-0-691-02846-0.

77. John C. Holt (2005). The Buddhist Visnu: Religious Transformation, Politics, and Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-231-50814-8.

78. Hera S. Walker (1998). Indigenous Or Foreign?: A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong, Sino-Platonic Papers, Issues 81–87. University of Pennsylvania. p. 45.

79. Arthur Cotterall (2012). The Pimlico Dictionary of Classical Mythologies. Random House. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4481-2996-6.

80. Rosalind Lefeber (1994). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India-Kiskindhakanda. Princeton University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-691-06661-5.

81. Richard Karl Payne (1998). Re-Visioning "Kamakura" Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-8248-2078-7.

82. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 38–41.

83. Peter D. Hershock (2006). Buddhism in the Public Sphere: Reorienting Global Interdependence. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-135-98674-2.

84. Reiko Ohnuma (2017). Unfortunate Destiny: Animals in the Indian Buddhist Imagination. Oxford University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-19-063755-2.

85. Louis E. Fenech (2013). The Sikh Zafar-namah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–150 with note 28. ISBN 978-0-19-993145-3.

86. John Stratton Hawley; Gurinder Singh Mann (1993). Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. State University of New York Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-7914-1426-2.

87. Devdutt Pattanaik (1 September 2000). The Goddess in India: The Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine. Inner Traditions * Bear & Company. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-89281-807-5. Retrieved 18 July2012.

88. Lutgendorf, Philip (1997). "Monkey in the Middle: The Status of Hanuman in Popular Hinduism". Religion. 27 (4): 311. doi:10.1006/reli.1997.0095.

89. Philip Lutgendorf (2002), Evolving a monkey: Hanuman, poster art and postcolonial anxiety, Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol 36, Issue 1–2, pages 71–110

90. Christophe Jaffrelot (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. p. 183 note 4. ISBN 978-93-80607-04-7.

91. Christophe Jaffrelot (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. pp. 332, 389–391. ISBN 978-93-80607-04-7.

92. Daromir Rudnyckyj; Filippo Osella (2017). Religion and the Morality of the Market. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–82. ISBN 978-1-107-18605-7.

93. Pathik Pathak (2008). Future of Multicultural Britain: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma. Edinburgh University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7486-3546-7.

94. Chetan Bhatt (2001). Hindu nationalism: origins, ideologies and modern myths. Berg. pp. 180–192. ISBN 978-1-85973-343-1.

95. Lutgendorf, Philip (2001). "Five heads and no tale: Hanumān and the popularization of Tantra". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 5 (3): 269–296. doi:10.1007/s11407-001-0003-3. S2CID 144825928.

96. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 319, 380–388.

97. T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 58, 190–194. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

98. David N. Lorenzen (1995). Bhakti Religion in North India: Community Identity and Political Action. State University of New York Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-7914-2025-6.

99. Vanamali 2010, p. 14.

100. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 60.

101. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 11–12, 101.

102. Reports of a Tour in Bundelkhand and Rewa in 1883–84, and of a Tour in Rewa, Bundelkhand, Malwa, and Gwalior, in 1884–85, Alexander Cunningham, 1885

103. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 59–60.

104. "Hanuman Garhi".

http://www.uptourism.gov.in. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

105. "Five historical Hindu temples of Pakistan". WION. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

106. Academy, Himalayan. "Hinduism Today Magazine".

http://www.hinduismtoday.com. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

107. The Indian Express, Chandigarh, Tuesday, 2 November 2010, p. 5.

108. Lutgendorf 2007.

109. Swati Mitra (2012). Temples of Madhya Pradesh. Eicher Goodearth and Government of Madhya Pradesh. p. 41. ISBN 978-93-80262-49-9.

110. Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 239, 24.

111. Raymond Brady Williams (2001). An introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-521-65422-7. Retrieved 14 May 2009. hanuman sarangpur.Page 128

112. New Hindu temple serves Frisco's growing Asian Indian population, Dallas Morning News, 6 August 2015

113. James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-8239-2287-1.

114. Schechner, Richard; Hess, Linda (1977). "The Ramlila of Ramnagar [India]". The Drama Review: TDR. 21 (3): 51–82. doi:10.2307/1145152. JSTOR 1145152.

115. Encyclopedia Britannica (2015). "Navratri – Hindu festival".

116. Ramlila, the traditional performance of the Ramayana, UNESCO

117. Ramlila Pop Culture India!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle, by Asha Kasbekar. Published by ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 1-85109-636-1. Page 42.

118. Toni Shapiro-Phim, Reamker, The Cambodian Version of Ramayana, Asia Society

119. Marrison, G. E (1989). "Reamker (Rāmakerti), the Cambodian Version of the Rāmāyaṇa. A Review Article". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 121 (1): 122–129. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00167917. JSTOR 25212421.

120. Jukka O. Miettinen (1992). Classical Dance and Theatre in South-East Asia. Oxford University Press. pp. 120–122. ISBN 978-0-19-588595-8.

121. Leakthina Chau-Pech Ollier; Tim Winter (2006). Expressions of Cambodia: The Politics of Tradition, Identity and Change. Routledge. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-1-134-17196-5.

122. James R. Brandon; Martin Banham (1997). The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-521-58822-5.

123. Margarete Merkle (2012). Bali: Magical Dances. epubli. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-3-8442-3298-1.

124. J. Kats (1927), The Rāmāyana in Indonesia, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 4, No. 3 (1927), pp. 579–585

125. Malini Saran (2005), The Ramayana in Indonesia: alternate tellings, India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 4 (SPRING 2005), pp. 66–82

126. Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. pp. xvii, 5–16 (Indonesia), 17–21 (Malaysia), 34–37. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

127. Marijke Klokke (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. pp. 391–399. ISBN 978-979-26-2499-1.

128. Andrea Acri; H.M. Creese; A. Griffiths (2010). From Lanka Eastwards: The Ramayana in the Literature and Visual Arts of Indonesia. BRILL Academic. pp. 197–203, 209–213. ISBN 978-90-04-25376-6.

129. Moertjipto (1991). The Ramayana Reliefs of Prambanan. Penerbit Kanisius. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-979-413-720-8.

130. Hildred Geertz (2004). The Life of a Balinese Temple: Artistry, Imagination, and History in a Peasant Village. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 154–165. ISBN 978-0-8248-2533-1.

131. Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

132. Amolwan Kiriwat (1997), KHON: MASKED DANCE DRAMA OF THE THAI EPIC RAMAKIENArchived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, University of Maine, Advisor: Sandra Hardy, pages 3–4, 7

133. Planet, Lonely; Isalska, Anita; Bewer, Tim; Brash, Celeste; Bush, Austin; Eimer, David; Harper, Damian; Symington, Andy (2018). Lonely Planet Thailand. Lonely Planet. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-78701-926-3. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

134. Lutgendorf 2007, p. 211.

135. Tony Moore; Tim Mousel (2008). Muay Thai. New Holland. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-84773-151-7.

136. "Wives Of Hanuman".

137. "Did you know how Dara Singh was chosen for the role of Hanuman in Ramayan?". mid-day. 30 May 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

138. "Hanuman: the journey of a mythical superhero". News18. 21 October 2005. Retrieved 14 June2020.

139. "5 Bollywood Movies About Hanuman". BookMyShow. 2 June 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

140. Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), retrieved 19 March 2019

141. "Revealed: Obama always carries Hanuman statuette in pocket". The Hindu. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

142. "Obama Reveals Lucky Charms During Interview". Associated Press. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

143. Amish Tripathi (12 March 2018). "What India can learn from 'Black Panther'". washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

144. Nicole Drum (20 February 2018). "'Black Panther' Movie Had a Word Censored in India". comicbook.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

145. "Rodrigo y Gabriela: Fusing Flamenco And Metal". NPR.org. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

Bibliography• Claus, Peter J.; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). "Hanuman". South Asian folklore. Taylor & Francis. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

• Lutgendorf, Philip (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

• Vanamali, V (2010). Hanuman: The Devotion and Power of the Monkey God. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-59477-914-5.

• Sri Ramakrishna Math (1985): Hanuman Chalisa. Chennai (India): Sri Ramakrishna Math. ISBN 81-7120-086-9.

• Mahabharata (1992). Gorakhpur (India): Gitapress.

• Anand Ramayan (1999). Bareily (India): Rashtriya Sanskriti Sansthan.

• Swami Satyananda Sarawati: Hanuman Puja. India: Devi Mandir. ISBN 1-887472-91-6.

• The Ramayana Smt. Kamala Subramaniam. Published by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan (1995). ISBN 81-7276-406-5

• Hanuman – In Art, Culture, Thought and Literature by Shanti Lal Nagar (1995). ISBN 81-7076-075-5

Further reading

• Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

• Helen M. Johnson (1931). Hanumat's birth and Varuṇa's subjection (Chapter III of the Jain Ramayana by Hemachandra). Baroda Oriental Institute.

• Lutgendorf, Philip (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8.

• Robert Goldman; Sally Goldman (2006). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Volume V: Sundarakāṇḍa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3166-7.

• Vanamali, Mataji Devi (2010). Hanuman: The Devotion and Power of the Monkey God Inner Traditions, USA. ISBN 1-59477-337-8.

External links• Hanuman at Encyclopædia Britannica

• Popular Temples Of Lord Hanuman In India

• Hanuman Aarti in Hindi and English. BhaktiSansar.in(in Hindi). Viewed on 2020-07-22 .