Part 2 of 2

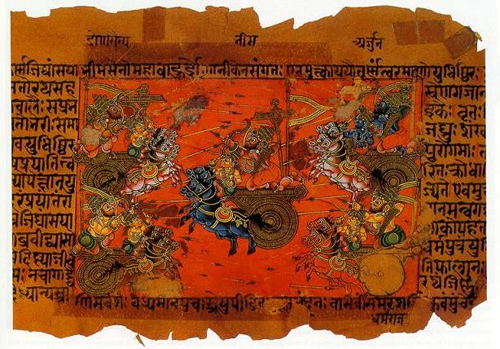

Early medieval recension from BengalChance discovery of a 6th century manuscript reveals insights into the evolution of the narrative. Importantly, the ‘Daśagrīvā Rākṣasa Charitrām Vadham’ (Slaying of the Ten-Headed Giant) manuscript contains only five kandas (chapters), and ends with the trio’s triumphant return to Ayodhya.[31][32]

Missing from this particular recension are the ‘Balakanda’ dealing with Rama’s childhood, and the ‘Uttarakanda’ – which narrates (a) Rama’s divinity as an avatar of Vishnu, (b) the events leading up to the exile of Sita, (c) the death of Rama’s devoted brother, Lakshmana. These are also the only two books where the Sage Valmiki appears as a character.[33]

The manuscript was discovered in 2015, from an archive compiled by the German Indologist Theodor Aufrecht.

Early references in Tamil literatureMain article: Ramayana in Tamil literature

Even before Kambar wrote the Ramavataram in Tamil in the 12th century AD, there are many ancient references to the story of Ramayana, implying that the story was familiar in the Tamil lands even before the Common Era. References to the story can be found in the Sangam literature of Akanaṉūṟu,(dated 1st century BCE)[34] and Purananuru (dated 300 BC),[35][36] the twin epics of Silappatikaram (dated 2nd Century CE)[37] and Manimekalai (cantos 5, 17 and 18),[38][39][40] and the Alvar literature of Kulasekhara Alvar, Thirumangai Alvar, Andal and Nammalvar (dated between 5th and 10th Centuries CE).[41] Even the songs of the Nayanmars have references to Ravana and his devotion to Lord Siva.

Buddhist versionMain article: Dasaratha Jataka

In the Buddhist variant of the Ramayana (Dasaratha Jataka), Dasharatha was king of Benares and not Ayodhya. Rama (called Rāmapaṇḍita in this version) was the son of Kaushalya, first wife of Dasharatha. Lakṣmaṇa (Lakkhaṇa) was a sibling of Rama and son of Sumitra, the second wife of Dasharatha. Sita was the wife of Rama. To protect his children from his wife Kaikeyi, who wished to promote her son Bharata, Dasharatha sent the three to a hermitage in the Himalayas for a twelve-year exile. After nine years, Dasharatha died and Lakkhaṇa and Sita returned; Rāmapaṇḍita, in deference to his father's wishes, remained in exile for a further two years. This version does not include the abduction of Sītā.There is no Ravan in this version i.e. no Ram-ravan war.

In the explanatory commentary on Jātaka, Rāmapaṇḍita is said to have been a previous birth of the Buddha, and Sita as previous birth of Yasodharā(Rahula-Mata).

But, Ravana appears in other Buddhist literature, the Lankavatara Sutra.

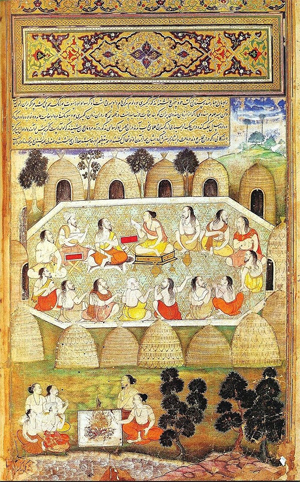

Jain versionsMain articles: Rama in Jainism and Salakapurusa

Jain versions of the Ramayana can be found in the various Jain agamas like Saṅghadāsagaṇī Vāchaka's Vasudevahiṇḍī (circa 4th century CE),[42] Ravisena's Padmapurana (story of Padmaja and Rama, Padmaja being the name of Sita), Hemacandra's Trisastisalakapurusa charitra (hagiography of 63 illustrious persons), Sanghadasa's Vasudevahindi and Uttarapurana by Gunabhadara. According to Jain cosmology, every half time cycle has nine sets of Balarama, Vasudeva and prativasudeva. Rama, Lakshmana and Ravana are the eighth Baldeva, Vasudeva and prativasudeva respectively. Padmanabh Jaini notes that, unlike in the Hindu Puranas, the names Baladeva and Vasudeva are not restricted to Balarama and Krishna in Jain Puranas. Instead they serve as names of two distinct classes of mighty brothers, who appear nine times in each half time cycle and jointly rule half the earth as half-chakravartins. Jaini traces the origin of this list of brothers to the jinacharitra (lives of jinas) by Acharya Bhadrabahu (3d–4th century BCE).

In the Jain epic of Ramayana, it is not Rama who kills Ravana as told in the Hindu version. Perhaps this is because Rama, a liberated Jain Soul in his last life, is unwilling to kill.[43] Instead, it is Lakshmana who kills Ravana (as Vasudeva killes Prativasudeva).[43] In the end, Rama, who led an upright life, renounces his kingdom, becomes a Jain monk and attains moksha. On the other hand, Lakshmana and Ravana go to Hell. However, it is predicted that ultimately they both will be reborn as upright persons and attain liberation in their future births. According to Jain texts, Ravana will be the future Tirthankara (omniscient teacher) of Jainism.

The Jain versions have some variations from Valmiki's Ramayana. Dasharatha, the king of Ayodhya had four queens: Aparajita, Sumitra, Suprabha and Kaikeyi. These four queens had four sons. Aparajita's son was Padma and he became known by the name of Rama. Sumitra's son was Narayana: he came to be known by another name, Lakshmana. Kaikeyi's son was Bharata and Suprabha's son was Shatrughna. Furthermore, not much was thought of Rama's fidelity to Sita. According to the Jain version, Rama had four chief queens: Maithili, Prabhavati, Ratinibha, and Sridama. Furthermore, Sita takes renunciation as a Jain ascetic after Rama abandons her and is reborn in heaven as Indra. Rama, after Lakshman's death, also renounces his kingdom and becomes a Jain monk. Ultimately, he attains Kevala Jnana omniscience and finally liberation. Rama predicts that Ravana and Lakshmana, who were in the fourth hell, will attain liberation in their future births. Accordingly, Ravana is the future Tirthankara of the next half ascending time cycle and Sita will be his Ganadhara.

Sikh versionIn Guru Granth Sahib, there is a description of two types of Ramayana. One is a spiritual Ramayana which is the actual subject of Guru Granth Sahib, in which Ravana is ego, Sita is budhi (intellect), Rama is inner soul and Laxman is mann (attention, mind). Guru Granth Sahib also believes in the existence of Dashavatara who were kings of their times which tried their best to restore order to the world. King Rama (Ramchandra) was one of those who is not covered in Guru Granth Sahib. Guru Granth Sahib states:

ਹੁਕਮਿ ਉਪਾਏ ਦਸ ਅਉਤਾਰਾ॥

हुकमि उपाए दस अउतारा॥

By hukam (supreme command), he created his ten incarnations

Rather there is no Ramayana written by any Guru. Guru Gobind Singh however is known to have written Ram Avatar in a text which is highly debated on its authenticity. Guru Gobind Singh clearly states that though all the 24 avatars incarnated for the betterment of the world, but fell prey to ego and therefore were destroyed by the supreme creator.

He also said that the almighty, invisible, all prevailing God created great numbers of Indras, Moons and Suns, Deities, Demons and sages, and also numerous saints and Brahmanas (enlightened people). But they too were caught in the noose of death (Kaal) (transmigration of the soul).

NepalBesides being the site of discovery of the oldest surviving manuscript of the Ramayana, Nepal gave rise to two regional variants in mid 19th – early 20th century. One, written by Bhanubhakta Acharya, is considered the first epic of Nepali language, while the other, written by Siddhidas Mahaju in Nepal Bhasa was a foundational influence in the Nepal Bhasa renaissance.

Ramayana written by Bhanubhakta Acharya is one of the most popular verses in Nepal. The popularization of the Ramayana and its tale, originally written in Sanskrit Language was greatly enhanced by the work of Bhanubhakta. Mainly because of his writing of Nepali Ramayana, Bhanubhakta is also called Aadi Kavi or The Pioneering Poet.

Southeast Asian

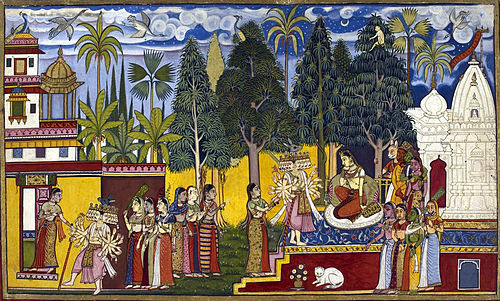

Cambodia Cambodian classical dancers as Sita and Ravana, the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh (c. 1920s)

Cambodian classical dancers as Sita and Ravana, the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh (c. 1920s)The Cambodian version of the Ramayana, Reamker (Khmer: រាមកេរ្ដិ៍ - Glory of Rama), is the most famous story of Khmer literature since the Kingdom of Funan era. It adapts the Hindu concepts to Buddhist themes and shows the balance of good and evil in the world. The Reamker has several differences from the original Ramayana, including scenes not included in the original and emphasis on Hanuman and Sovanna Maccha, a retelling which influences the Thai and Lao versions. Reamker in Cambodia is not confined to the realm of literature but extends to all Cambodian art forms, such as sculpture, Khmer classical dance, theatre known as lakhorn luang (the foundation of the royal ballet), poetry and the mural and bas-reliefs seen at the Silver Pagoda and Angkor Wat.

Indonesia Lakshmana, Rama and Sita during their exile in Dandaka Forest depicted in Javanese dance

Lakshmana, Rama and Sita during their exile in Dandaka Forest depicted in Javanese danceThere are several Indonesian adaptations of Ramayana, including the Javanese Kakawin Ramayana[44][45] and Balinese Ramakavaca.[46] The first half of Kakawin Ramayana is similar to the original Sanskrit version, while the latter half is very different. One of the recognizable modifications is the inclusion of the indigenous Javanese guardian demigod, Semar, and his sons, Gareng, Petruk, and Bagong who make up the numerically significant four Punokawan or "clown servants". Kakawin Ramayana is believed to have been written in Central Java circa 870 AD during the reign of Mpu Sindok in the Medang Kingdom.[47] The Javanese Kakawin Ramayana is not based on Valmiki's epic, which was then the most famous version of Rama's story, but based on Ravanavadha or the "Ravana massacre", which is the sixth or seventh century poem by Indian poet Bhattikavya.[48]

Kakawin Ramayana was further developed on the neighboring island of Bali becoming the Balinese Ramakavaca. The bas-reliefs of Ramayana and Krishnayana scenes are carved on balustrades of the 9th century Prambanan temple in Yogyakarta,[49] as well as in the 14th century Penataran temple in East Java.[50] In Indonesia, the Ramayana is a deeply ingrained aspect of the culture, especially among Javanese, Balinese and Sundanese people, and has become the source of moral and spiritual guidance as well as aesthetic expression and entertainment, for example in wayang and traditional dances.[51] The Balinese kecak dance for example, retells the story of the Ramayana, with dancers playing the roles of Rama, Sita, Lakhsmana, Jatayu, Hanuman, Ravana, Kumbhakarna and Indrajit surrounded by a troupe of over 50 bare-chested men who serve as the chorus chanting "cak". The performance also includes a fire show to describe the burning of Lanka by Hanuman.[52] In Yogyakarta, the Wayang Wong Javanese dance also retells the Ramayana. One example of a dance production of the Ramayana in Java is the Ramayana Ballet performed on the Trimurti Prambanan open air stage, with the three main prasad spires of the Prambanan Hindu temple as a backdrop.[53]

LaosPhra Lak Phra Lam is a Lao language version, whose title comes from Lakshmana and Rama. The story of Lakshmana and Rama is told as the previous life of Gautama buddha.

MalaysiaThe Hikayat Seri Rama of Malaysia incorporated element of both Hindu and Islamic mythology.[54][55][56]

Myanmar Rama (Yama) and Sita (Me Thida) in Yama Zatdaw, the Burmese version of Ramyana

Rama (Yama) and Sita (Me Thida) in Yama Zatdaw, the Burmese version of RamyanaYama Zatdaw is the Burmese version of Ramayana. It is also considered the unofficial national epic of Myanmar. There are nine known pieces of the Yama Zatdaw in Myanmar. The Burmese name for the story itself is Yamayana, while zatdaw refers to the acted play or being part of the jataka tales of Theravada Buddhism. This Burmese version is also heavily influenced by Ramakien (Thai version of Ramayana) which resulted from various invasions by Konbaung Dynasty kings toward the Ayutthaya Kingdom.

PhilippinesMain article: Maharadia Lawana

The Maharadia Lawana, an epic poem of the Maranao people of the Philippines, has been regarded as an indigenized version of the Ramayana since it was documented and translated into English by Professor Juan R. Francisco and Nagasura Madale in 1968.[57](p"264")[58] The poem, which had not been written down before Francisco and Madale's translation,[57](p"264") narrates the adventures of the monkey-king, Maharadia Lawana, whom the Gods have gifted with immortality.[57]

Francisco, an indologist from the University of the Philippines Manila, believed that the Ramayana narrative arrived in the Philippines some time between the 17th to 19th centuries, via interactions with Javanese and Malaysian cultures which traded extensively with India.[59](p101)

By the time it was documented in the 1960s, the character names, place names, and the precise episodes and events in Maharadia Lawana's narrative already had some notable differences from those of the Ramayana. Francisco believed that this was a sign of "indigenization", and suggested that some changes had already been introduced in Malaysia and Java even before the story was heard by the Maranao, and that upon reaching the Maranao homeland, the story was "further indigenized to suit Philippine cultural perspectives and orientations."[59](p"103")

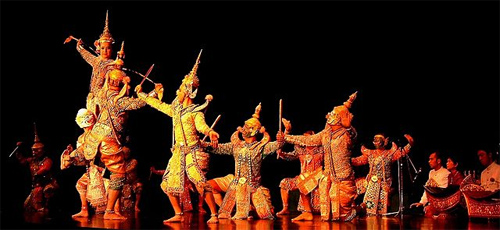

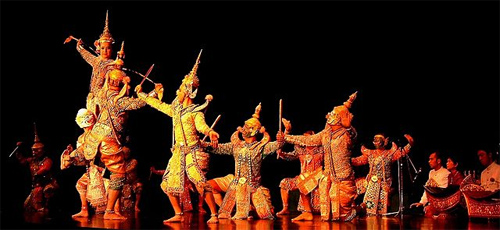

Thailand The Thai retelling of the tale—Ramakien—is popularly expressed in traditional regional dance theatre

The Thai retelling of the tale—Ramakien—is popularly expressed in traditional regional dance theatreThailand's popular national epic Ramakien (Thai:รามเกียรติ์, from Sanskrit rāmakīrti, glory of Ram) is derived from the Hindu epic. In Ramakien, Sita is the daughter of Ravana and Mandodari (thotsakan and montho). Vibhishana (phiphek), the astrologer brother of Ravana, predicts the death of Ravana from the horoscope of Sita. Ravana has thrown her into the water, but she is later rescued by Janaka (chanok).[43]:149 While the main story is identical to that of Ramayana, many other aspects were transposed into a Thai context, such as the clothes, weapons, topography and elements of nature, which are described as being Thai in style. It has an expanded role for Hanuman and he is portrayed as a lascivious character. Ramakien can be seen in an elaborate illustration at Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok.

Critical editionA critical edition of the text was compiled in India in the 1960s and 1970s, by the Oriental Institute at Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, India, utilizing dozens of manuscripts collected from across India and the surrounding region.[60] An English language translation of the critical edition was completed in November 2016 by Sanskrit scholar Robert P. Goldman of the University of California, Berkeley.[61]Critical editionsAny edition that attempts to construct a text of a work using all the available evidence is "critical," whatever its methodology. Critical editions require collation of the different manuscript witnesses, and the construction of a reading text out of the results of that collation. Most critical editions use a base manuscript, whose readings they accept except where there is reason not to do so, but some are more eclectic than others. Critical editions encourage readers to think about the work, more than about its specific manuscript presentation, and may well be more informative on such topics as the work's sources, historical context, form, style, and other literary matters.

Critical editions you may be familiar with include The Riverside Chaucer, edited by Larry Benson, and The Vision of Piers Plowman by William Langland, edited by A.V.C. Schmidt. In general, a critical edition will contain a single (edited) version of the text, along with substantial introductory matter, explanatory, and textual notes.

-- Types of Editions, Harvard's Geoffrey Chaucer Website

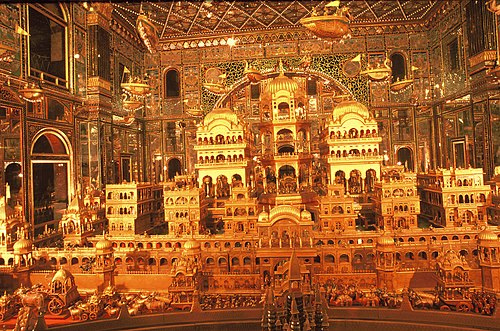

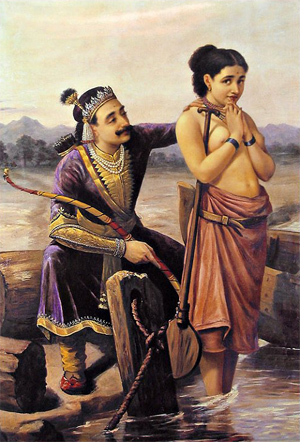

Influence on culture and artSee also: Ramayana Ballet

A Ramlila actor wears the traditional attire of Ravana.

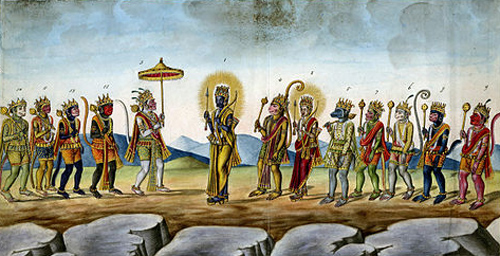

A Ramlila actor wears the traditional attire of Ravana.One of the most important literary works of ancient India, the Ramayana has had a profound impact on art and culture in the Indian subcontinent and southeast Asia with the lone exception of Vietnam. The story ushered in the tradition of the next thousand years of massive-scale works in the rich diction of regal courts and Hindu temples. It has also inspired much secondary literature in various languages, notably Kambaramayanam by Tamil poet Kambar of the 12th century, Telugu language Molla Ramayanam by poet Molla and Ranganatha Ramayanam by poet Gona Budda Reddy, 14th century Kannada poet Narahari's Torave Ramayana and 15th century Bengali poet Krittibas Ojha's Krittivasi Ramayan, as well as the 16th century Awadhi version, Ramacharitamanas, written by Tulsidas.

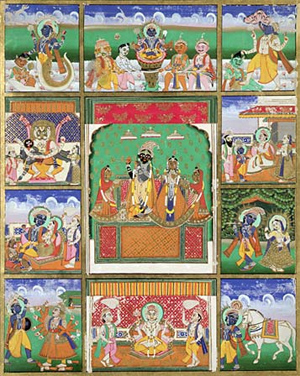

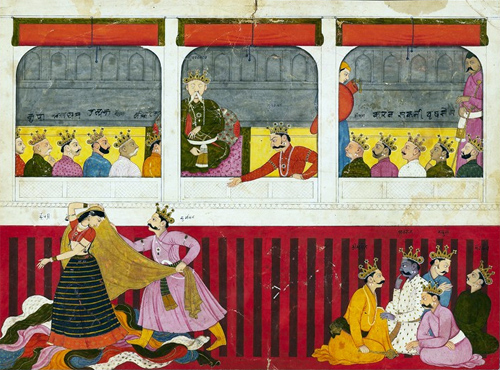

Ramayanic scenes have also been depicted through terracottas, stone sculptures, bronzes and paintings.[62] These include the stone panel at Nagarjunakonda in Andhra Pradesh depicting Bharata's meeting with Rama at Chitrakuta (3rd century CE).[62]

The Ramayana became popular in Southeast Asia during 8th century and was represented in literature, temple architecture, dance and theatre. Today, dramatic enactments of the story of the Ramayana, known as Ramlila, take place all across India and in many places across the globe within the Indian diaspora.

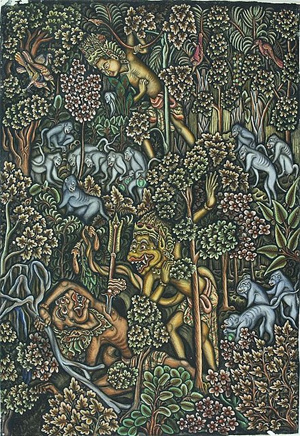

Hanuman discovers Sita in her captivity in Lanka, as depicted in Balinese kecak dance.

Hanuman discovers Sita in her captivity in Lanka, as depicted in Balinese kecak dance.In Indonesia, especially Java and Bali, Ramayana has become a popular source of artistic expression for dance drama and shadow puppet performance in the region. Sendratari Ramayana is Javanese traditional ballet of wayang orang genre, routinely performed in Prambanan Trimurti temple and in cultural center of Yogyakarta.[63] Balinese dance drama of Ramayana is also performed routinely in Balinese Hindu temples, especially in temples such as Ubud and Uluwatu, where scenes from Ramayana is integrap part of kecak dance performance. Javanese Wayang (Wayang Kulit of purwa and Wayang Wong) also draws its episodes from Ramayana or Mahabharata.

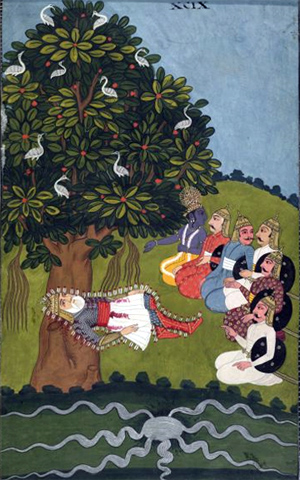

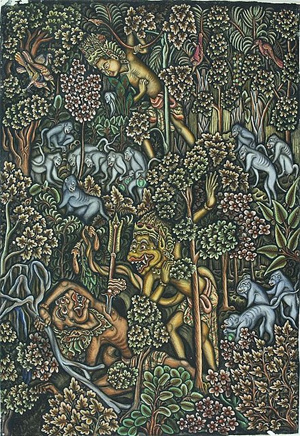

The painting by the Indonesian (Balinese) artist, Ida Bagus Made Togog depicts the episode from the Ramayana about the Monkey Kings of Sugriva and Vali; The Killing of Vali. Rama depicted as a crowned figure with a bow and arrow.

The painting by the Indonesian (Balinese) artist, Ida Bagus Made Togog depicts the episode from the Ramayana about the Monkey Kings of Sugriva and Vali; The Killing of Vali. Rama depicted as a crowned figure with a bow and arrow.Ramayana has also been depicted in many paintings, notably by the Indonesian (Balinese) artists such as I Gusti Dohkar (before 1938), I Dewa Poetoe Soegih, I Dewa Gedé Raka Poedja, Ida Bagus Made Togog before 1948 period. Their paintings is currently in the National Museum of World Cultures collections of Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, Netherland. Also Malaysian artist Syed Thajudeen in 1972. The painting is currently in the permanent collection of the Malaysian National Visual Arts Gallery.

Religious significance Deities Sita (right), Rama (center), Lakshmana (left) and Hanuman (below, seated) at Bhaktivedanta Manor, Watford, England

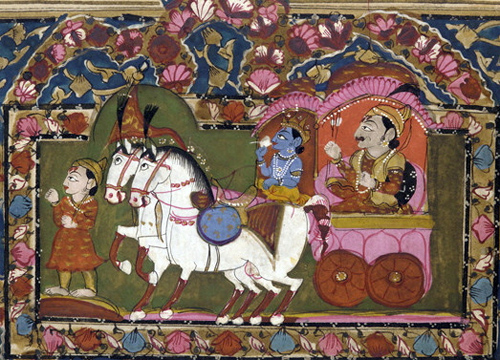

Deities Sita (right), Rama (center), Lakshmana (left) and Hanuman (below, seated) at Bhaktivedanta Manor, Watford, EnglandRama, the hero of the Ramayana, is one of the most popular deities worshipped in the Hindu religion. Each year, many devout pilgrims trace their journey through India and Nepal, halting at each of the holy sites along the way. The poem is not seen as just a literary monument, but serves as an integral part of Hinduism and is held in such reverence that the mere reading or hearing of it or certain passages of it, is believed by Hindus to free them from sin and bless the reader or listener.

According to Hindu tradition, Rama is an incarnation (Avatar) of god Vishnu. The main purpose of this incarnation is to demonstrate the righteous path (dharma) for all living creatures on earth.

In popular cultureMultiple modern, English-language adaptations of the epic exist, namely Rama Chandra Series by Amish Tripathi, Ramayana Series by Ashok Banker and a mythopoetic novel, Asura: Tale of the Vanquished by Anand Neelakantan. Another Indian author, Devdutt Pattanaik, has published three different retellings and commentaries of Ramayana titled Sita, The Book Of Ram and Hanuman's Ramayan. A number of plays, movies and television serials have also been produced based upon the Ramayana.[64]

Stage Hanoman At Kecak Fire Dance, Bali 2018

Hanoman At Kecak Fire Dance, Bali 2018One of the best known Ramayana plays is Gopal Sharman's The Ramayana, a contemporary interpretation in English, of the great epic based on the Valmiki Ramayana. The play has had more than 3000 plus performances all over the world, mostly as a one-woman performance by actress Jalabala Vaidya, wife of the playwright Gopal Sharman. The Ramayana has been performed on Broadway, London's West End, United Nations Headquarters, the Smithsonian Institution among other international venue and in more than 35 cities and towns in India.

Starting in 1978 and under the supervision of Baba Hari Dass, Ramayana has been performed every year by Mount Madonna School in Watsonville, California.[citation needed] Currently,[when?] it is the largest yearly, Western version of the epic being performed.[citation needed] It takes the form of a colorful musical with custom costumes, sung and spoken dialog, jazz-rock orchestration and dance. This performance takes place in a large audience theater setting usually in June, in San Jose, CA. Dass has taught acting arts, costume-attire design, mask making and choreography to bring alive characters of Rama, Sita, Hanuman, Lakshmana, Shiva, Parvati, Vibhishan, Jatayu, Sugriva, Surpanakha, Ravana and his rakshasa court, Meghnadha, Kumbhakarna and the army of monkeys and demons.[citation needed]

In the Philippines, a jazz ballet production was produced in the 1970's entitled "Rama at Sita" (Rama and Sita).

The production was a result of a collaboration of four National Artists, Bienvenido Lumbera’s libretto (National Artist for Literature), production design by Salvador Bernal (National Artist for Stage Design), music by Ryan Cayabyab (National Artist for Music) and choreography by Alice Reyes (National Artist for Dance).[65]

Plays• Kanchana Sita, Saketham and Lankalakshmi – award-winning trilogy by Malayalam playwright C. N. Sreekantan Nair

• Lankeswaran – a play by the award-winning Tamil cinema actor R. S. Manohar

• Kecak - a Balinese traditional folk dance which plays and tells the story of Ramayana

Exhibitions• Gallery Nucleus:Ramayana Exhibition -Part of the art of the book Ramayana: Divine Loophole by Sanjay Patel.

• The Rama epic: Hero. Heroine, Ally, Foe by The Asian Art Museum.

Books La bufanda roja by Fitra Ismu Kusumo, a promoter of Indonesian art and culture in Mexico

La bufanda roja by Fitra Ismu Kusumo, a promoter of Indonesian art and culture in Mexico• Ramayana by C. Rajagopalachari

• The Ramayana by R. K. Narayan

• The Song of Rama by Vanamali

• Ramayana by William Buck and S Triest

• Ramayana: Divine Loophole by Sanjay Patel

• Sita: An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana By Devdutt Pattanaik

• Hanuman's Ramayan By Devdutt Pattanaik

• Rama Chandra Series by Amish Tripathi, a fictional retelling of the Ramayana. It has 3 books till now — Ram: Scion of Ikshvaku, Sita: Warrior of Mithila, and Raavan: Enemy of Aryavarta.

• Asura, Tale of the Vanquished by Anand Neelakantan, a novel.

• The Forest of Enchantments by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni.

Movies• Lanka Dahan (1917)

• Ramayana (1942)

• Ram Rajya (1943)

• Rambaan (1948)

• Ramayan (1954)

• Sampoorna Ramayanam (1958)

• Sampoorna Ramayana (1961)

• Lava Kusha (1963)

• Sampoorna Ramayanamu (1971)

• Sita Kalyanam (1976)

• Kanchana Sita (1977)

• Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama (1992)

• Ramayanam (1996)

• Lav Kush (1997)

• Opera Jawa (2008)

• Sita Sings the Blues (2008)

• Ramayana: The Epic (2010)

• Lava Kusa: The Warrior Twins (2010)

• Ramayana: The Epic (2010)

• Sri Rama Rajyam (2011)

• Yak: The Giant King (2012)

• Adipurush (2022), upcoming film

TV series• Ramayan – originally broadcast on Doordarshan, produced by Ramanand Sagar in 1987

• Luv Kush – originally broadcast on Doordarshan, produced by Ramanand Sagar in 1988

• Jai Hanuman – originally broadcast on Doordarshan, produced and directed by Sanjay Khan

• Ramayan (2002) – originally broadcast on Zee TV, produced by B.R. Chopra

• Ramayan (2008) – originally broadcast on Imagine TV, produced by Sagar Enterprise

• Ramayan (2012) – a remake of the 1987 series and aired on Zee TV

• Antariksh (2004) – a sci-fi version of Ramayan. Originally broadcast on Star Plus

• Raavan – series on life of Ravana based on Ramayana. Originally broadcast on Zee TV

• Sankatmochan Mahabali Hanuman – 2015 series based on the life of Hanuman presently broadcasting on Sony TV

• Siya Ke Ram – a series on Star Plus, originally broadcast from 16 November 2015 to 4 November 2016

• Rama Siya Ke Luv Kush – 2019 series based on Uttar Ramayan, showing the life of children of Rama Sita, Kush and Luv broadcasting on Colors TV

References1. "Ramayana". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

2. "Ramayana | Meaning of Ramayana by Lexico". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

3. The Rámáyan of Válmíki.

4. "Ramayana | Summary, Characters, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

5. "Valmiki Ramayana". valmikiramayan.net. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

6. Goldman 1984, p. 20–22.

7. Pattanaik, Devdutt (8 August 2020). "Was Ram born in Ayodhya". mumbaimirror.

8. J. L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL. pp. 379–. ISBN 90-04-10260-4.

9. Mukherjee, P. (1981). The History of Medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa. Asian Educational Services. p. 74. ISBN 9788120602298. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

10. Living Thoughts of the Ramayana. Jaico Publishing House. 2002. ISBN 9788179920022. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

11. Krishnamoorthy, K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sahitya Akademi (1991). A Critical Inventory of Rāmāyaṇa Studies in the World: Foreign languages. Sahitya Akademi in collaboration with Union Academique Internationale, Bruxelles. ISBN 9788172015077. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

12. Bulcke, C.; Prasāda, D. (2010). Rāmakathā and Other Essays. Vani Prakashan. p. 116. ISBN 9789350001073. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

13. Monier Monier Williams, राम, Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology

14. Monier Monier Williams, रात्रि, Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology

15. Monier Monier Williams, अयन, Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology

16. Debroy, Bibek (25 October 2017). The Valmiki Ramayana Volume 1. Penguin Random House India. p. xiv. ISBN 9789387326262 – via Google Books.

17. Arshia Sattar (2016), Why the Uttara Kanda changes the way the Ramayana should be read, Scroll.in

18. Buck, William (19 May 1981). Ramayana. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520227033. Retrieved 19 May2020 – via Google Books.

19. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4:1:1; trans. Swami Prabhavananda, commentary by Abbot George Burke (Swami Nirmalananda Giri), online at

https://ocoy.org/dharma-for-christians/ ... avalkya-1/20. Ajay K. Rao, Re-figuring the Ramayana as Theology: A History of Reception in Premodern India (London: Routledge, 2014), 2. ISBN 9781134077359; and Robert P. Goldman, The Ramayana Of Valmiki, Vol. 1: Balakanda, An Epic Of Ancient India (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2007), 14-18. ISBN 9788120831629

21. Mukherjee Pandey, Jhimli (18 December 2015). "6th-century Ramayana found in Kolkata, stuns scholars". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. TNN. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

22. Gita Jnana Brahmacharini Sharanya Chaitanya (1 July 2018). "Rama Brings Ahalya Back to Her Living Form". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

23. "Subahu - Asura Slain by Rama". Indian Mythology. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

24. Encyclopedia for Epics of Ancient India Quote: VISWASRAVAS. [Source: Dowson's Classical Dictionary of Hindu Mythology] Son of Prajapati Pulastya, or, according to a statement of the Mahabharata, a reproduction of half Pulastya himself. By a Brahmani wife, daughter of the sage Bharadwaja, named Idavida or Ilavida, he had a son, Kuvera, the god of wealth.

25. The Mahabharata 3.259.1-12; translated by J. A. B. van Buitenen, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1975, pp. 728-9.

26. CANTO LXVII.: THE BREAKING OF THE BOW. sacredtexts.com. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

27. Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2001) Sītāpaharaṇam: Changing thematic Idioms in Sanskrit and Tamil. In Dirk W. Lonne ed. Tofha-e-Dil: Festschrift Helmut Nespital, Reinbeck, 2 vols., pp. 783-97. ISBN 3-88587-033-9.

https://www.academia.edu/2514821/S%C4%A ... _and_Tamil28. Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2014) Reflections on "Rāma-Setu" in South Asian Tradition. The Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society, Vol. 105.3: 1–14, ISSN 0047-8555.

https://www.academia.edu/8779702/Reflec ... _Tradition29.

https://valmikiramayan.net/utf8/yuddha/ ... _frame.htm30. Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (1 January 2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816075645.

31. P, Jhimli Mukherjee; Dec 18, ey / TNN / Updated. "6th-century Ramayana found in Kolkata, stuns scholars | Kolkata News - Times of India". The Times of India.

32. "6th century Ramayana manuscript Found in Kolkata | Stuns Scholars".

33. Sattar, Arshia. "Why the Uttara Kanda changes the way the Ramayana should be read". Scroll.in.

34. Dakshinamurthy, A (July 2015). "Akananuru: Neytal – Poem 70". Akananuru. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

35. Hart, George L; Heifetz, Hank (1999). The four hundred songs of war and wisdom : an anthology of poems from classical Tamil : the Puṟanāṉūṟu. Columbia University Press.

36. Kalakam, Turaicămip Pillai, ed. (1950). Purananuru. Madras.

37. Dikshitar, V R Ramachandra (1939). The Silappadikaram. Madras, British India: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

38. Pandian, Pichai Pillai (1931). Cattanar's Manimekalai. Madras: Saiva Siddhanta Works. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

39. Aiyangar, Rao Bahadur Krishnaswami (1927). Manimekhalai In Its Historical Setting. London: Luzac & Co. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

40. Shattan, Merchant-Prince (1989). Daniélou, Alain (ed.). Manimekhalai: The Dancer With the Magic Bowl. New York: New Directions.

41. Hooper, John Stirling Morley (1929). Hymns of the Alvars. Calcutta: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 July2019.

42. Jain, Jagdishchandra (1979). "Some Old Tales and Episodes in the Vasudevahiṇḍi" (PDF). Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 60 (1/4): 167–173. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41692302.

43. Ramanujan, A.K (2004). The Collected Essays of A.K. Ramanujan (PDF) (4. impr. ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 145.

44. "Ramayana Kakawin Vol. 1". archive.org.

45. "The Kakawin Ramayana -- an old Javanese rendering of the …".

http://www.nas.gov.sg. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

46. Bhalla, Prem P. (22 August 2017). ABC of Hinduism. Educreation Publishing. p. 277.

47. Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

48. Ardianty, Dini (8 June 2015). "Perbedaan Ramayana - Mahabarata dalam Kesusastraan Jawa Kuna dan India" (in Indonesian).

49. "Prambanan - Taman Wisata Candi". borobudurpark.com. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

50. Indonesia, Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia / National Library of. "Panataran Temple (East Java) - Temples of Indonesia". candi.pnri.go.id. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

51. Joefe B. Santarita (2013), Revisiting Swarnabhumi/dvipa: Indian Influences in Ancient Southeast Asia

52. Planet, Lonely. "Bali Kecak Dance, Fire Dance and Sanghyang Dance Evening Tour in Indonesia". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

53. "THE KEEPERS: CNN Introduces Guardians of Indonesia's Rich Cultural Traditions".

http://www.indonesia.travel. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

54. Fang, Liaw Yock (2013). A History of Classical Malay Literature. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. p. 142. ISBN 9789794618103.

55. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1898. pp. 107–.

56. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 1898. pp. 143–.

57. Guillermo, Artemio R. (16 December 2011). Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810875111.

58. Francisco, Juan R. "Maharadia Lawana" (PDF).

59. FRANCISCO, JUAN R. (1989). "The Indigenization of the Rama Story in the Philippines". Philippine Studies. 37(1): 101–111. JSTOR 42633135.

60. "Ramayana Translation Project turns its last page, after four decades of research | Berkeley News". news.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

61. "UC Berkeley researchers complete decades-long translation project | The Daily Californian". dailycal.org. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

62. B. B. Lal (2008). Rāma, His Historicity, Mandir, and Setu: Evidence of Literature, Archaeology, and Other Sciences. Aryan Books. ISBN 978-81-7305-345-0.

63. Donald Frazier (11 February 2016). "On Java, a Creative Explosion in an Ancient City". The New York Times.

64. Mankekar, Purnima (1999). Screening Culture, Viewing Politics: An Ethnography of Television, Womanhood, and Nation in Postcolonial India. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2390-7.

65. Philippines, Cultural Center of the. "BALLET PHILIPPINES' RAMA, HARI | Cultural Center of the Philippines". BALLET PHILIPPINES' RAMA, HARI. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

Sources• Arya, Ravi Prakash (ed.).Ramayana of Valmiki: Sanskrit Text and English Translation. (English translation according to M. N. Dutt, introduction by Dr. Ramashraya Sharma, 4-volume set) Parimal Publications: Delhi, 1998, ISBN 81-7110-156-9

• Bhattacharji, Sukumari (1998). Legends of Devi. Orient Blackswan. p. 111. ISBN 978-81-250-1438-6.

• Brockington, John (2003). "The Sanskrit Epics". In Flood, Gavin (ed.). Blackwell companion to Hinduism. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 116–128. ISBN 0-631-21535-2.

• Buck, William; van Nooten, B. A. (2000). Ramayana. University of California Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-520-22703-3.

• Dutt, Romesh C. (2004). Ramayana. Kessinger Publishing. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4191-4387-8.

• Dutt, Romesh Chunder (2002). The Ramayana and Mahabharata condensed into English verse. Courier Dover Publications. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-486-42506-1.

• Fallon, Oliver (2009). Bhatti's Poem: The Death of Rávana (Bhaṭṭikāvya). New York: New York University Press, Clay Sanskrit Library. ISBN 978-0-8147-2778-2.

• Goldman, Robert P (1984). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 81-208-3162--4.

• Keshavadas, Sadguru Sant (1988). Ramayana at a Glance. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 211. ISBN 978-81-208-0545-3.

• Goldman, Robert P. (1990). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India: Balakanda. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01485-2.

• Goldman, Robert P. (1994). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India: Kiskindhakanda. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06661-5.

• Goldman, Robert P. (1996). The Ramayana of Valmiki: Sundarakanda. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06662-2.

• B. B. Lal (2008). Rāma, His Historicity, Mandir, and Setu: Evidence of Literature, Archaeology, and Other Sciences. Aryan Books. ISBN 978-81-7305-345-0.

• Mahulikar, Dr. Gauri. Effect Of Ramayana On Various Cultures And Civilisations, Ramayan Institute

• Rabb, Kate Milner, National Epics, 1896 – see eText in Project Gutenberg

• Murthy, S. S. N. (November 2003). "A note on the Ramayana" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. New Delhi. 10(6): 1–18. ISSN 1084-7561. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 August 2012.

• Prabhavananda, Swami (1979). The Spiritual Heritage of India. Vedanta Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-87481-035-6. (see also Wikipedia article on book)

• Raghunathan, N. (transl.), Srimad Valmiki Ramayanam, Vighneswara Publishing House, Madras (1981)

• Rohman, Todd (2009). "The Classical Period". In Watling, Gabrielle; Quay, Sara (eds.). Cultural History of Reading: World literature. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-33744-4.

• Sattar, Arshia (transl.) (1996). The Rāmāyaṇa by Vālmīki. Viking. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-14-029866-6.

• Sachithanantham, Singaravelu (2004). The Ramayana Tradition in Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. ISBN 9789831002346.

• Sundararajan, K.R. (1989). "The Ideal of Perfect Life : The Ramayana". In Krishna Sivaraman; Bithika Mukerji (eds.). Hindu spirituality: Vedas through Vedanta. The Crossroad Publishing Co. pp. 106–126. ISBN 978-0-8245-0755-8.

• A different Song – Article from "The Hindu" 12 August 2005 – "The Hindu : Entertainment Thiruvananthapuram / Music : A different song". Hinduonnet.com. 12 August 2005. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

• Valmiki's Ramayana illustrated with Indian miniatures from the 16th to the 19th century, 2012, Editions Diane de Selliers, ISBN 9782903656768

Further reading

Sanskrit text• Electronic version of the Sanskrit text, input by Muneo Tokunaga

• Sanskrit text on GRETIL

Translations• Valmiki Ramayana verse translation by Desiraju Hanumanta Rao, K. M. K. Murthy et al.

• [1] translation of valmiki ramayana including Uttara Khanda

• Valmiki Ramayana translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith (1870–1874) (Project Gutenberg)

• Prose translation of the complete Ramayana by M. N. Dutt (1891–1894): Balakandam, Ayodhya kandam, Aranya kandam, Kishkindha kandam, Sundara Kandam, Yuddha Kandam, Uttara Kandam

• Jain Ramayana of Hemchandra English translation; seventh book of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra; 1931

• Summary of The Ramayana Summary of Maurice Winternitz, A History of Indian Literature, trans. by S. Ketkar.

• The Ramayana condensed into English verse by R. C. Dutt (1899) at archive.org

• Rāma the Steadfast: an early form of the Rāmāyaṇa translated by J. L. Brockington and Mary Brockington. Penguin, 2006. ISBN 0-14-044744-X.

Secondary sources• Jain, Meenakshi. (2013). Rama and Ayodhya. Aryan Books International, 2013.

External links• Ramayana at the Encyclopædia Britannica|

• Ramayana at Project Gutenberg

•

The Ramayana of Valmiki English translation by Hari Prasad Shastri, 1952 (revised edition with interwoven glossary)• A condensed verse translation by Romesh Chunder Dutt sponsored by the Liberty Fund

• The Ramayana as a Monomyth from UC Berkeley (archived)

• Collection: Art of the Ramayana from the University of Michigan Museum of Art