Part 4 of 4

Animal welfareAshoka's rock edicts declare that injuring living things is not good, and no animal should be slaughtered for sacrifice.[181] However, he did not prohibit common cattle slaughter or beef eating.[182]

He imposed a ban on killing of "all four-footed creatures that are neither useful nor edible", and of specific animal species including several birds, certain types of fish and bulls among others. He also banned killing of female goats, sheep and pigs that were nursing their young; as well as their young up to the age of six months. He also banned killing of all fish and castration of animals during certain periods such as Chaturmasa and Uposatha.[183][184]

Ashoka also abolished the royal hunting of animals and restricted the slaying of animals for food in the royal residence.[185]

Because he banned hunting, created many veterinary clinics and eliminated meat eating on many holidays, the Mauryan Empire under Ashoka has been described as "one of the very few instances in world history of a government treating its animals as citizens who are as deserving of its protection as the human residents".[186]

Pasteurism is insidiously working its way in India, the Central Committee, according to the Indian, having in hand at Lahore Rs. 31,000, at Bombay Rs. 5,000, and in Bengal Rs. 30,000.

Up to the present time the worst crime of modern science, vivisection, has not penetrated into India, but it is hoped that Pasteur Institutes will lead to the complete vivisector’s laboratory. The culture of poison germs and their experimental injection into animals is a form of “research” which, identical in principle with vivisection, does not at first sight shock people to the same extent as the deliberate carving up, burning and tearing of living animals. The injecting syringe filled with venom causes no more pain, it is argued, than the prick of a needle, and the subsequent slow torture of the poisoned animals is left out of account.

But Pasteurism is vivisection in a modified form, and though the sufferings caused by it are small compared with the horrors of the torture-trough, they are wrought under the sway of that evil principle that we may rightly seek to escape the penalty of our own misdoings by inflicting pain on others weaker than ourselves. The bond between man and his animal cousins has always been clearly recognized in India, and the presence of the One Life in the hearts of all beings— not of man only— has been a fundamental doctrine in Indian philosophy. Mineral, vegetable, animal, man, all pulsate by the same Life, and those to whom this truth is a reality can never carelessly destroy anything or deliberately torture a being that can feel pain. Hence the axiom, “Harmlessness is the highest law,” and the ideal held up of being “the friend of every creature.” Repeated conquests by rougher and harsher races have hardened the old tenderness, and the alienation of sympathy between men and the brutes which is so marked a feature in city life has led to street cruelties to horses and cattle such as disgrace the cities of Europe.

But even yet the animals wander freely in friendly fashion in many of the towns and in the country districts, pushing enquiring noses into shops, no man making them afraid. Worn-out creatures pass their last days peacefully, and if a European suggests the idea of slaying a beast because it can no longer labour, he is regarded with shocked surprise. Yet in this land an attempt is being made, and threatens to be successful, to introduce vivisection under the shield of western science, and it has actually been found necessary to form an Anti-vivisection Society in Calcutta. I had the pleasure of lecturing for this Society in the Calcutta Town Hall last January, but the very necessity for its existence shows how India has fallen from her old ideals. Rationalizing Societies like the Brahmo Samaj, with its flesh-eating and alcohol-drinking, have paved the way, by their disregard of the ancient rules of pure living, for the worse abuses that are now threatening to invade the laud. The International Society for the Protection of Animals from Vivisection has given useful help to the Indian movement by its literature. It is an interesting and significant fact that in Paris, one of the chief centres of the vivisectionists, we see also the most dangerous forms of magic and the lowest depths of “Satanism.” The selfishness which finds one of its most extreme expressions in vivisection, in the attempt to wrench open nature’s secrets by reckless torture of others, is the essential characteristic of the black magician, and vivisection is but one kind of sorcery. Its practice is a graduation in the black art, and carries a man far along the terrible road whose end is death— not of the body alone. -- Lucifer, On the Watch-Tower, May 15, 1896

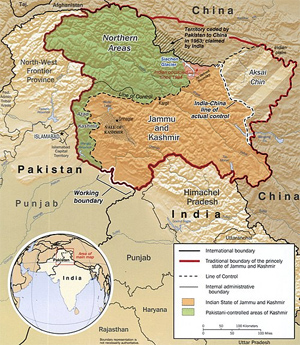

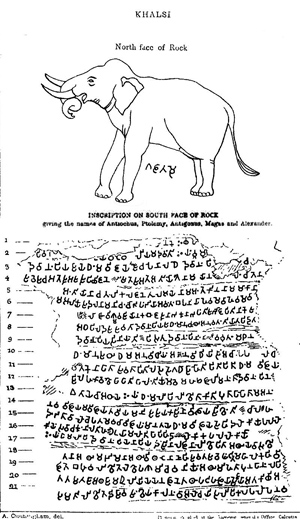

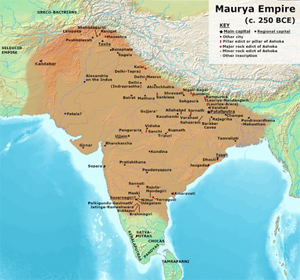

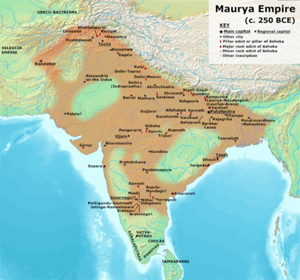

Foreign relations  Territories "conquered by the Dhamma" according to Major Rock Edict No.13 of Ashoka (260–218 BCE).[187][188]It is well known that

Territories "conquered by the Dhamma" according to Major Rock Edict No.13 of Ashoka (260–218 BCE).[187][188]It is well known that Ashoka sent dütas or emissaries to convey messages or letters, written or oral (rather both), to various people. The VIth Rock Edict about "oral orders" reveals this. It was later confirmed that it was not unusual to add oral messages to written ones, and the content of Ashoka's messages can be inferred likewise from the XIIIth Rock Edict: They were meant to spread his dhammavijaya, which he considered the highest victory and which he wished to propagate everywhere (including far beyond India).

the idea of installing inscriptions might have travelled with this script. There is obvious and undeniable trace of cultural contact through the adoption of the Kharosthi script, and, as Achaemenid influence is seen in some of the formulations used by Ashoka in his inscriptions. This indicates to us that Ashoka was indeed in contact with other cultures, and was an active part in mingling and spreading new cultural ideas beyond his own immediate walls.[189]

Hellenistic worldIn his rock edicts, Ashoka states that he had encouraged the transmission of Buddhism to the Hellenistic kingdoms to the west and that the Greeks in his dominion were converts to Buddhism and recipients of his envoys:

Now it is conquest by Dhamma that Beloved-of-the-Gods considers to be the best conquest. And it (conquest by Dhamma) has been won here, on the borders, even six hundred yojanas away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni. Here in the king's domain among the Greeks, the Kambojas, the Nabhakas, the Nabhapamktis, the Bhojas, the Pitinikas, the Andhras and the Palidas, everywhere people are following Beloved-of-the-Gods' instructions in Dhamma. Even where Beloved-of-the-Gods' envoys have not been, these people too, having heard of the practice of Dhamma and the ordinances and instructions in Dhamma given by Beloved-of-the-Gods, are following it and will continue to do so.

— Edicts of Ashoka, Rock Edict (S. Dhammika)[190]

It is possible, but not certain, that Ashoka received letters from Greek rulers and was acquainted with the Hellenistic royal orders in the same way as he perhaps knew of the inscriptions of the Achaemenid kings, given the presence of ambassadors of Hellenistic kings in India (as well as the dütas sent by Ashoka himself).[189] Dionysius is reported to have been such a Greek ambassador at the court of Ashoka, sent by Ptolemy II Philadelphus,[191] who himself is mentioned in the Edicts of Ashoka as a recipient of the Buddhist proselytism of Ashoka. Some Hellenistic philosophers, such as Hegesias of Cyrene, who probably lived under the rule of King Magas, one of the supposed recipients of Buddhist emissaries from Asoka, are sometimes thought to have been influenced by Buddhist teachings.[192]

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek (Yona) Buddhist monks, active in spreading Buddhism (the Mahavamsa, XII).[193]

Some Greeks (Yavana) may have played an administrative role in the territories ruled by Ashoka. The Girnar inscription of Rudradaman records that during the rule of Ashoka, a Yavana Governor was in charge in the area of Girnar, Gujarat, mentioning his role in the construction of a water reservoir.[194] [The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology by Upinder Singh p.18]

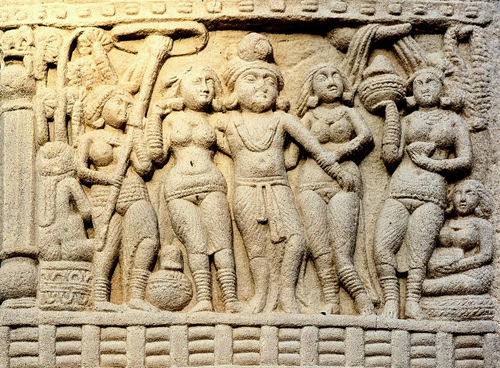

The Three Yavana Donors, Excerpt from "The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeologyby Upinder Singh

2016

P. 18

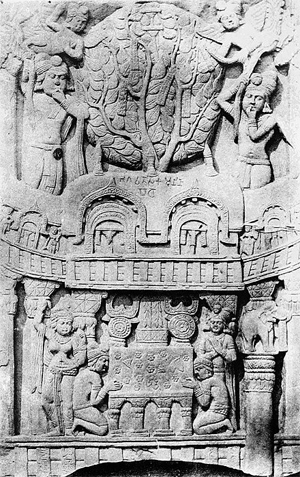

Yavanas occur as donors in three Sanchi inscriptions: The reading of inscription no. 89 is not absolutely certain. It seems to read: '[Sv]etapathasa (Yona?)sa danam' ('The gift of Yona? of Svetapatha'). Inscription no. 433 {engraved on two adjacent pavement slabs), reads: 'Cudayo[vana]kasa bo silayo' ('Two slabs of Cuda, the Yovanaka'). Inscription no. 475 reads: 'Setapathiyasa Yonasa danam' ('The gift of Yona of Setapatha').

The term Yavana may originally have referred to Greeks, but very soon was being used in a more general way to refer to foreigners from various parts of West Asia or the eastern Mediterranean region.69 Svetapatha and Setapatha sound like the same place. The Puranas refer to the Sveta mountain range lying to the north of Meru mountain.70 They also mention Svetadvipa as a place associated with Visnu and visited by Narada.71 This place appears in the Santi Parva of the Mahabharata as well, as an island lying to the north of Meru mountain, at the northern border of the ocean of milk, where Mahavisnu performed austerities in order to obtain brahma-vidya. The text adds that the people of Svetadvipa are worshippers of Siva and are rich in knowledge. They have certain peculiar physical traits -- they do not have sense-organs, do not have to eat food in order to live; their bodies and bones are very hard, their heads very broad and flat; they have four arms and sixty teeth, and have very loud voices.72  "The term Yavana may originally have referred to Greeks, but very soon was being used in a more general way to refer to foreigners from various parts of ..." -- How to Get Your Foot in the Door of Indian History ("Myths R Us")

"The term Yavana may originally have referred to Greeks, but very soon was being used in a more general way to refer to foreigners from various parts of ..." -- How to Get Your Foot in the Door of Indian History ("Myths R Us")

This Svetadvipa of the great epic and the Puranas seems to be a mythological place, and is of little help in identifying the place where our Sanchi Yavanas came from. One is tempted to suggest an identification of Svetapatha with the Svetapada of the Kalyan plates of Yasovarman;73 a place which corresponds with the area around Nasik, and where one could visualise Yavanas visiting or residing in this period for trade purposes. But the inscription in question is very late (11th century), and the time-gap between the Sanchi references and this inscription is too great for the identification to be pressed.

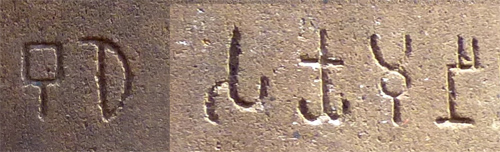

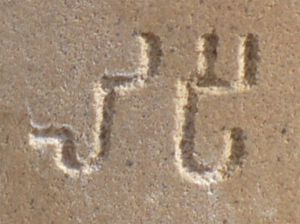

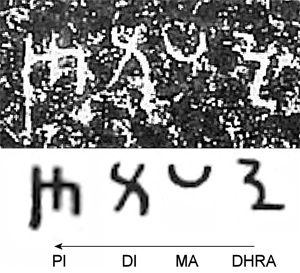

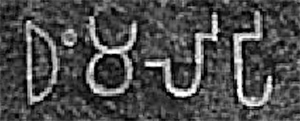

The Yavanarajya inscription is in Brahmi script and describes a dedication for a well and a tank in Mathura on "The last day of year 116 of Yavana dominion (Brahmi script: [x] Yavanarajya)". Although the term "Yavanas" can sometimes mean "westerners" in general, inscriptions made at this early period generally use the term Yavana to refer to the Indo-Greeks, and known inscriptions referring to the Indo-Parthians or Indo-Scythians in Mathura never use the term Yavana.

-- Yavanarajya inscription, by Wikipedia

It is thought that Ashoka's palace at Patna was modelled after the Achaemenid palace of Persepolis.[195] [De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 428]

Buddhist Dominance: Early Architecture and Sculpture, Excerpt from “Gardner's art through the ages”by Helen Gardner, d. 1946; Horst De la Croix; Richard G. Tansey, Diane Kirkpatrick

1991

BUDDHIST DOMINANCE

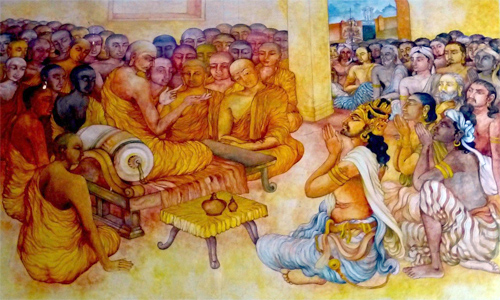

Early Architecture and SculptureThe earliest known examples of art in the service of Buddhism (from the middle of the third century B.C.) are both monumental and sophisticated. Emperor Asoka (272-232 B.C.), the grandson of Chandragupta, converted to Buddhism after witnessing the horrors of the brutal military campaigns by which he himself forcibly had unified most of northern India.

His palace at Patna in Bihar (ancient Pataliputra) was designed after the Achaemenid palace at Persepolis (Fig. 2-38).

11-3i. Lion capital of column erected by Emperor Asoka (272-232 B.C.) from Patna (ancient Pataliputra), India. Polished sandstone, 7’ high. Archeological Museum, Sarnath

11-3i. Lion capital of column erected by Emperor Asoka (272-232 B.C.) from Patna (ancient Pataliputra), India. Polished sandstone, 7’ high. Archeological Museum, SarnathMegasthenes, a Greek ambassador at the court of Asoka, has left a glowing report of Pataliputra. Only parts of columns, the foundations of buildings, and remnants of a wooden palisade now remain, but we may draw some idea of the architectural details from a series of commemorative and sacred columns that Soka raised throughout much of northern India. These monolithic pillars were of polished sandstone, some as high as 60 or 70 feet. The capital of one (Fig. 11-3), now in the Sarnath Museum near Benares, typifies the style of the period. It consists of a lotiform capital (a capital in the form of a lotus petal), on which rests a horizontal disk sculptured with a frieze of four animals alternating with four wheels. Seated on the disk are four addorsed (back-to-back) lions that originally were surmounted by another huge wheel. All of the forms are symbolic. The lotus, traditional symbol of divinity, also connoted humanity’s salvation in Buddhism. The wheel represented the cycle of life, death, and rebirth. This “wheel of life” often had other levels of meaning. In this instance, it was the teaching of Buddha – the “turning of the wheel of the law.”

The wheel itself (probably developed from ancient sun symbols) and the four animals (the four quarters of the compass) with which it is associated here imply a cosmological meaning in which the pillar as a whole symbolizes the world axis. The lions also had manifold meanings, but here they were specifically equated with Sakyamuni Buddha, who was known as the lion of the Sakya clan.The pillars are noteworthy not only for their symbolism, but also because they exemplify continuity of style. Although

the stiff, heraldic lions are typical of Persepolis, the low-relief animals around the disk are treated in the much earlier, fluid style of Mohenjo Daro. So, too, are the colossal figures of yakshas and yakshis, sculptured during Asoka’s time or somewhat later. These male and female divinities, originally worshiped as local nature spirits, gods of trees and rocks, now were incorporated into the Buddhist and Hindu pantheons.

Hellenistic Influence On Mauryan ArtThe Indo-Greek identity of Asoka throws a flood of light on the history of Mauryan art. Here one must pay tribute to scholars like Sir John Marshall, Alfred Foucher and Niharranjan Ray who were not aware that Asoka was Diodotus-I yet made no mistake in recognising the Hellenistic content of Mauryan art. Marshall realised that the lion capitals of Asoka represent a new era in Indian art that has no precursors. Their fixed expression, authentic spirit, canon-based form and stylisation all betray a strong Hellenistic inspiration. Niharranjan Ray echoes a similar sentiment[xli]. Ray doubted that the impetus could be from Achaemenid Persia and traced it to Hellenistic art. The history of the Topra pillar leaves no doubt about how this stimulus was transmitted. The failure to recognize that Chandragupta was in fact Sasigupta who was once a satrap of Alexander has been at the root of many problems in the interpretation of Gandhara art and Mauryan art. However, though Marshall and Ray came very close to the truth, they failed to see Alexander's hand behind the lions of Asoka.-- An Altar of Alexander Now Standing at Delhi [REDUCED VERSION], by Ranajit Pal

Legends about past livesBuddhist legends mention stories about Ashoka's past lives. According to a Mahavamsa story, Ashoka, Nigrodha and Devnampiya Tissa were brothers in a previous life. In that life, a pratyekabuddha was looking for honey to cure another, sick pratyekabuddha. A woman directed him to a honey shop owned by the three brothers. Ashoka generously donated honey to the pratyekabuddha, and wished to become the sovereign ruler of Jambudvipa for this act of merit.[196]

The woman wished to become his queen, and was reborn as Ashoka's wife Asandhamitta.[149] Later Pali texts credit her with an additional act of merit: she gifted the pratyekabuddha a piece of cloth made by her. These texts include the Dasavatthuppakarana, the so-called Cambodian or Extended Mahavamsa (possibly from 9th–10th centuries), and the Trai Bhumi Katha (15th century).[150]

According to an Ashokavadana story, Ashoka was born as Jaya in a prominent family of Rajagriha. When he was a little boy, he

gave the Gautama Buddha dirt imagining it to be food. The Buddha approved of the donation, and Jaya declared that he would become a king by this act of merit. The text also state that

Jaya's companion Vijaya was reborn as Ashoka's prime-minister Radhagupta.[197] In the later life, the Buddhist monk Upagupta tells Ashoka that his rough skin was caused by the impure gift of dirt in the previous life.[133] Some later texts repeat this story, without mentioning the negative implications of gifting dirt; these texts include Kumaralata's Kalpana-manditika, Aryashura's Jataka-mala, and the Maha-karma-vibhaga.

The Chinese writer Pao Ch'eng's Shih chia ju lai ying hua lu asserts that an insignificant act like gifting dirt could not have been meritorious enough to cause Ashoka's future greatness. Instead, the text claims that in another past life, Ashoka commissioned a large number of Buddha statues as a king, and this act of merit caused him to become a great emperor in the next life.[198]

The 14th century Pali-language fairy tale Dasavatthuppakarana (possibly from c. 14th century) combines the stories about the merchant's gift of honey, and the boy's gift of dirt. It narrates a slightly different version of the Mahavamsa story, stating that it took place before the birth of the Gautama Buddha. It then states that the merchant was reborn as the boy who gifted dirt to the Buddha; however, in this case, the Buddha [gave it to] his attendant Ānanda to create plaster from the dirt, which is used repair cracks in the monastery walls.[199]

Legacy

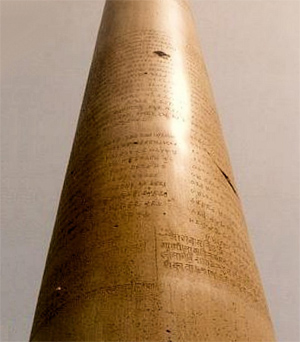

ArchitectureBesides the various stupas attributed to Ashoka, the pillars erected by him survive at various places in the Indian subcontinent.

Ashoka is often credited with the beginning of stone architecture in India, possibly following the introduction of stone-building techniques by the Greeks after Alexander the Great.[200] Before Ashoka's time, buildings

were probably built in non-permanent material, such as wood, bamboo or thatch.[200][201]

Ashoka may have rebuilt his palace in Pataliputra by replacing wooden material by stone,[202]

and may also have used the help of foreign craftmen.[203] Ashoka also innovated by using the permanent qualities of stone for his written edicts, as well as his pillars with Buddhist symbolism.

The Ashokan pillar at Lumbini, Nepal, Buddha's birthplace

The Ashokan pillar at Lumbini, Nepal, Buddha's birthplace  The Diamond throne at the Mahabodhi Temple, attributed to Ashoka

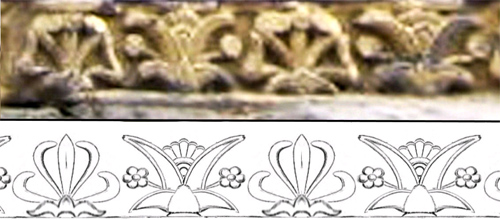

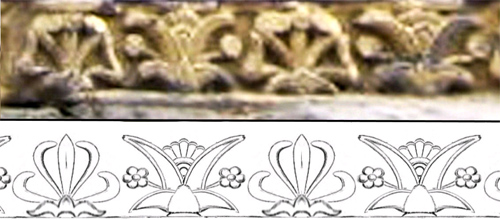

The Diamond throne at the Mahabodhi Temple, attributed to Ashoka Front frieze of the Diamond throne

Front frieze of the Diamond throne Mauryan ringstone, with standing goddess. Northwest Pakistan. 3rd century BCE. British Museum

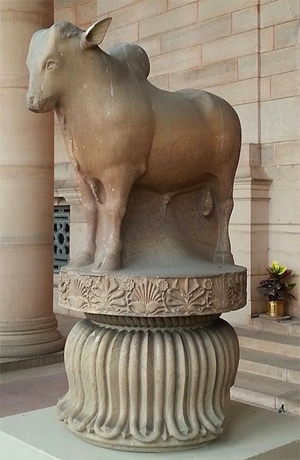

Mauryan ringstone, with standing goddess. Northwest Pakistan. 3rd century BCE. British Museum Rampurva bull capital, detail of the abacus, with two "flame palmettes" framing a lotus surrounded by small rosette flowers.Symbols

Rampurva bull capital, detail of the abacus, with two "flame palmettes" framing a lotus surrounded by small rosette flowers.SymbolsSymbols of Ashoka  Ashoka's pillar capital of Sarnath. This sculpture has been adopted as the National Emblem of India.

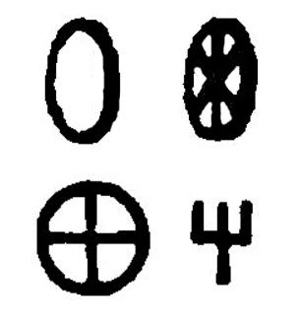

Ashoka's pillar capital of Sarnath. This sculpture has been adopted as the National Emblem of India.  Ashoka Chakra, "the wheel of Righteousness" (Dharma in Sanskrit or Dhamma in Pali)"

Ashoka Chakra, "the wheel of Righteousness" (Dharma in Sanskrit or Dhamma in Pali)"

Ashokan capitals were highly realistic and used a characteristic polished finish, Mauryan polish, giving a shiny appearance to the stone surface. Lion Capital of Ashoka, the capital of one of the pillars erected by Ashoka features a carving of a spoked wheel, known as the Ashoka Chakra. This wheel represents the wheel of Dhamma set in motion by the Gautama Buddha, and appears on the flag of modern India. This capital also features sculptures of lions, which appear on the seal of India.[160]

Both the Rampurva Bull and the Sankisa Elephant are, in my opinion, masterpieces of underestimated antiquity and importance. Both sculptures are unquestionably of pre-Asokan and even pre-Buddhist origin, as I suggested a decade ago in my Burlington Magazine series (see fn. 3, above). Since then, these conclusions have met with opposition in the West as well as in India; from Buddhists as well as non-Buddhists (although none has stated a case for his opposition). It is only now that public opinion is ready to listen. A decisive moment of change coincided with the publication in Berlin of my 1979 address to the Fifth Conference of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, where I read a paper offering firm proof that the Allahabad/Prayaga (formerly, 'Allahabad-Kosam') Pillar -- shown here in its present-day form at fig. 3) had been another pre-Asokan Bull-pillar like the one found at Rampurva (fig. 1).-- The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars, by John Irwin

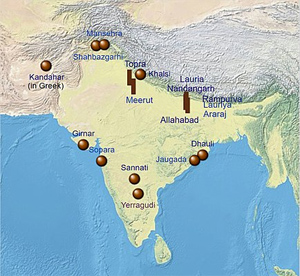

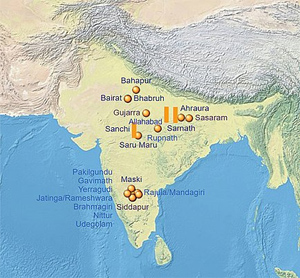

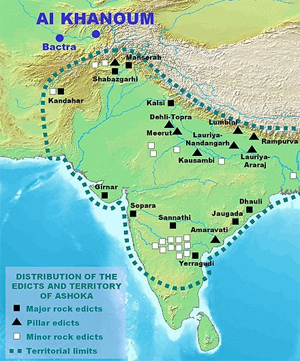

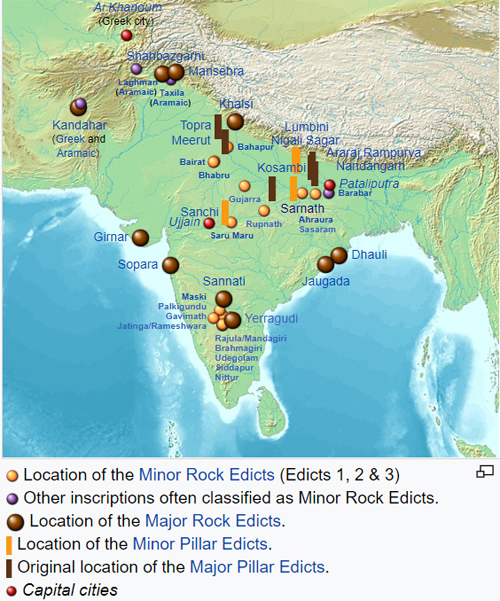

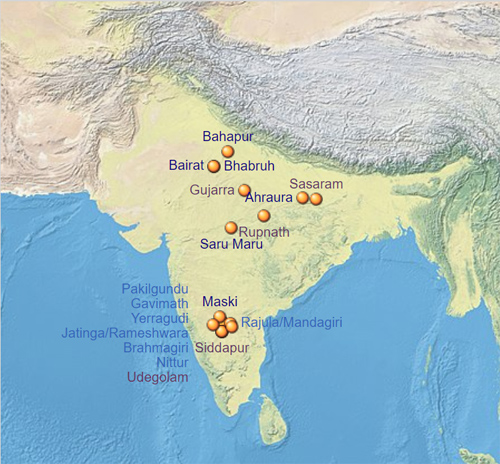

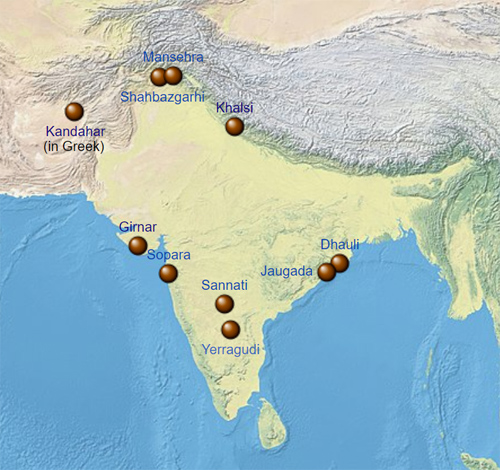

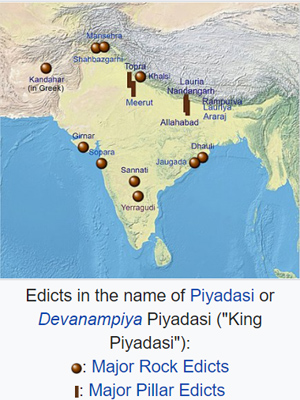

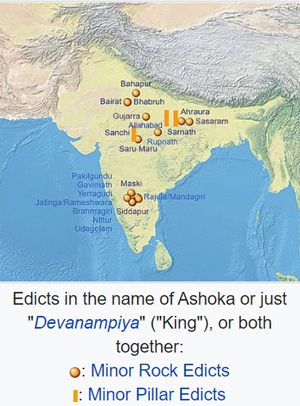

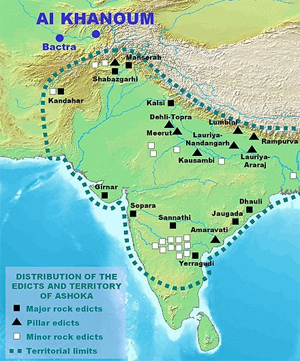

Inscriptions  Distribution of the Edicts of Ashoka, and location of the contemporary Greek city of Ai-Khanoum.[204]

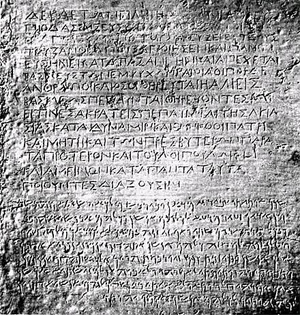

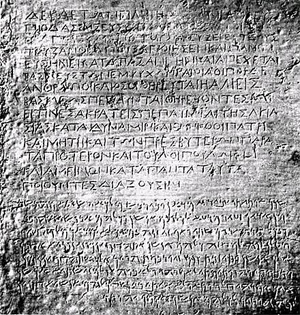

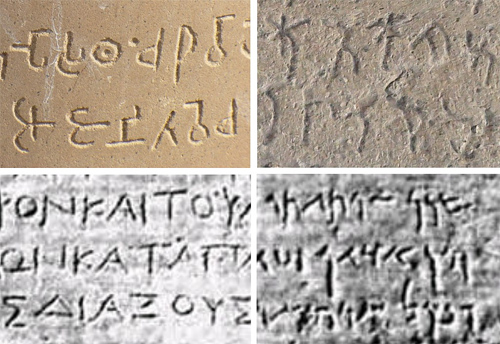

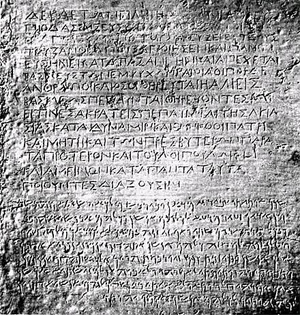

Distribution of the Edicts of Ashoka, and location of the contemporary Greek city of Ai-Khanoum.[204]  The Kandahar Edict of Ashoka, a bilingual inscription (in Greek and Aramaic) by King Ashoka, discovered at Kandahar (National Museum of Afghanistan).

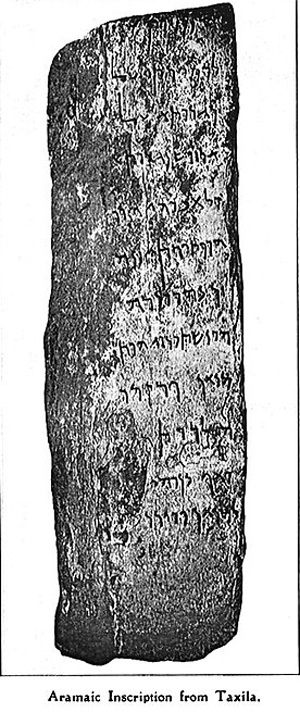

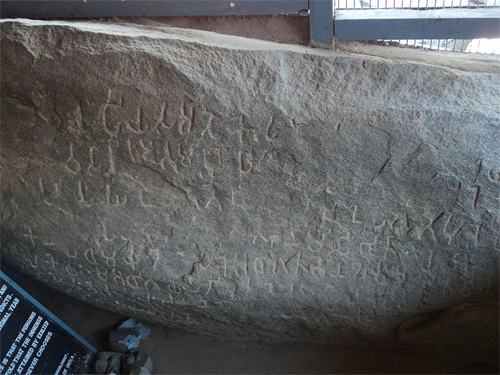

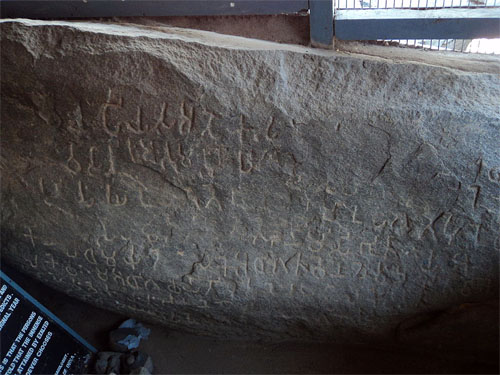

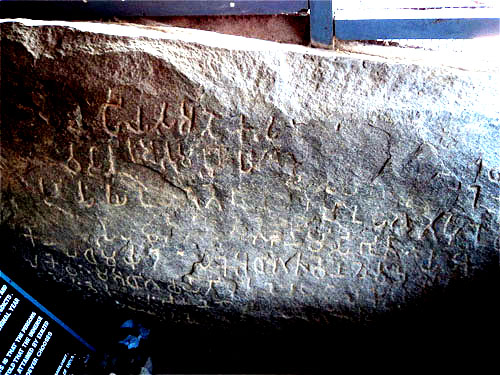

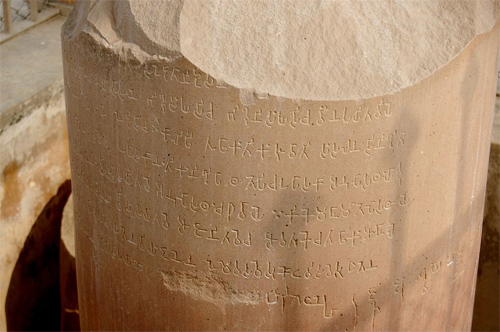

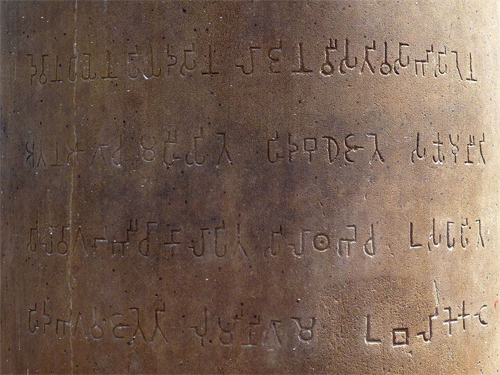

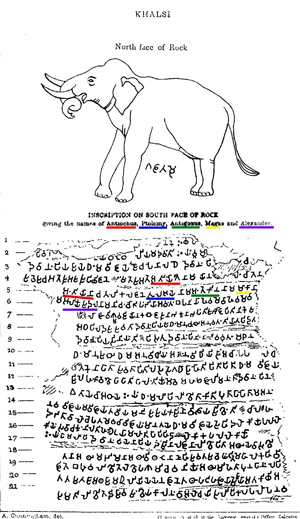

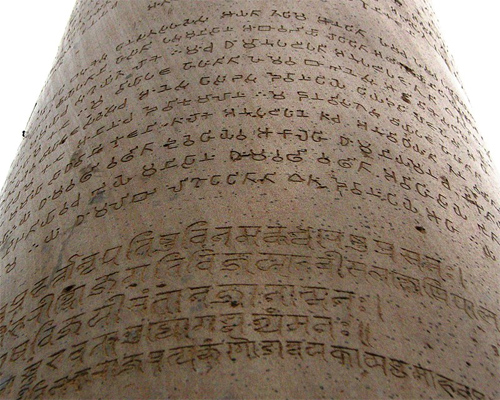

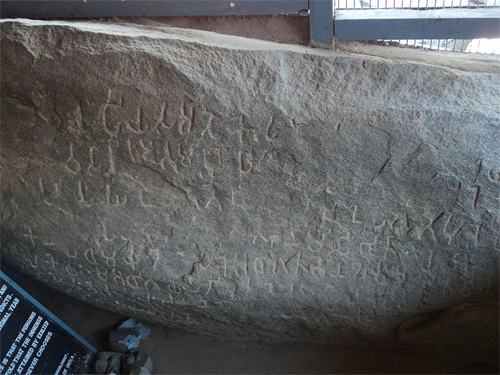

The Kandahar Edict of Ashoka, a bilingual inscription (in Greek and Aramaic) by King Ashoka, discovered at Kandahar (National Museum of Afghanistan).The edicts of Ashoka are a collection of 33 inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, issued during his reign.[failed verification] These inscriptions are dispersed throughout modern-day Pakistan and India, and represent the first tangible evidence of Buddhism. The edicts describe in detail the first wide expansion of Buddhism through the sponsorship of one of the most powerful kings of Indian history, offering more information about Ashoka's proselytism, moral precepts, religious precepts, and his notions of social and animal welfare.[205]

Before Ashoka, the royal communications appear to have been written on perishable materials such as palm leaves, birch barks, cotton cloth, and possibly wooden boards. While Ashoka's administration would have continued to use these materials, Ashoka also had his messages inscribed on rock edicts.[206]

Ashoka probably got the idea of putting up these inscriptions from the neighbouring Achaemenid empire.[165] It is likely that Ashoka's messages were also inscribed on more perishable materials, such as wood, and sent to various parts of the empire. None of these records survive now.[18]

Scholars are still attempting to analyse both the expressed and implied political ideas of the Edicts (particularly in regard to imperial vision), and make inferences pertaining to how that vision was grappling with problems and political realities of a "virtually subcontinental, and culturally and economically highly variegated, 3rd century BCE Indian empire.[13] Nonetheless, it remains clear that Ashoka's Inscriptions represent the earliest corpus of royal inscriptions in the Indian subcontinent, and therefore prove to be a very important innovation in royal practices."[205]

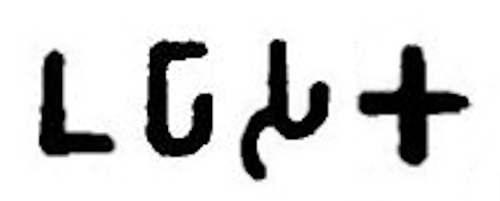

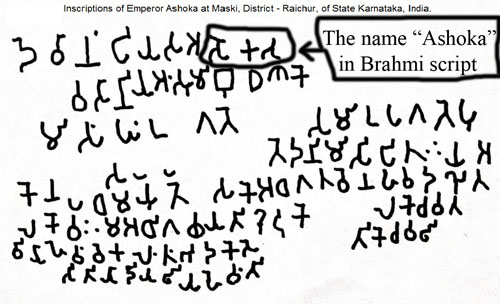

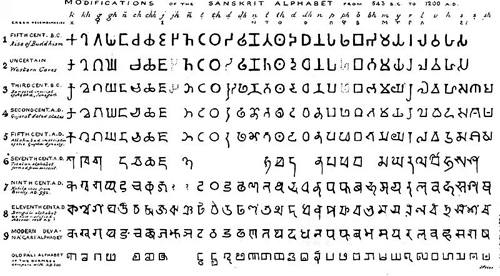

Most of Ashoka's inscriptions are written in a mixture of various Prakrit dialects, in the Brahmi script.[207]

Several of Ashoka's inscriptions appear to have been set up near towns, on important routes, and at places of religious significance.[208] Many of the inscriptions have been discovered in hills, rock shelters, and places of local significance.[209] Various theories have been put forward about why Ashoka or his officials chose such places, including that they were centres of megalithic cultures,[210] were regarded as sacred spots in Ashoka's time, or that their physical grandeur may be symbolic of spiritual dominance.[211]

Ashoka's inscriptions have not been found at major cities of the Maurya empire, such as Pataliputra, Vidisha, Ujjayini, and Taxila. [209] It is possible that many of these inscriptions are lost;

the 7th century Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang refers to some of Ashoka's pillar edicts, which have not been discovered by modern researchers.[208]

It appears that Ashoka dispatched every message to his provincial governors, who in turn, relayed it to various officials in their territory.[212] For example, the Minor Rock Edict 1 appears in several versions at multiple places: all the versions state that Ashoka issued the proclamation while on a tour, having spent 256 days on tour. The number 256 indicates that the message was dispatched simultaneously to various places.[213] Three versions of a message, found at edicts in the neighbouring places in Karnataka (Brahmagiri, Siddapura, and Jatinga-Rameshwara), were sent from the southern province's capital Suvarnagiri to various places. All three versions contain the same message, preceded by an initial greeting from the arya-putra (presumably Ashoka's son and the provincial governor) and the mahamatras (officials) in Suvarnagiri.[212]

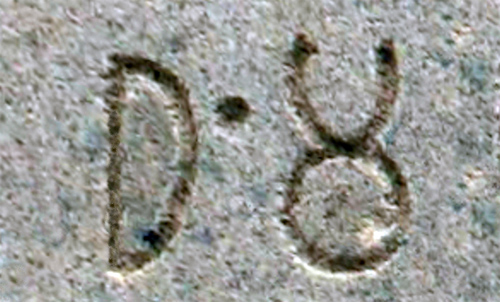

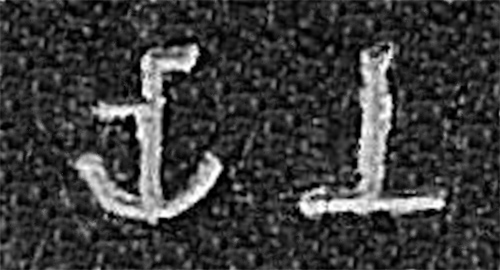

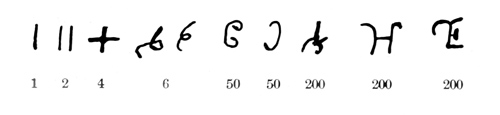

CoinageThe caduceus appears as a symbol of the punch-marked coins of the Maurya Empire in India, in the 3rd–2nd century BCE. Numismatic research suggests that this symbol was the symbol of king Ashoka, his personal "Mudra".[214] This symbol was not used on the pre-Mauryan punch-marked coins, but only on coins of the Maurya period, together with the three arched-hill symbol, the "peacock on the hill", the triskelis and the Taxila mark.[215]

Caduceus symbol on a Maurya-era punch-marked coin

Caduceus symbol on a Maurya-era punch-marked coin  A punch-marked coin attributed to Ashoka[216]

A punch-marked coin attributed to Ashoka[216]  A Maurya-era silver coin of 1 karshapana, possibly from Ashoka's period, workshop of Mathura. Obverse: Symbols including a sun and an animal Reverse: Symbol Dimensions: 13.92 x 11.75 mm Weight: 3.4 g.Modern scholarship

A Maurya-era silver coin of 1 karshapana, possibly from Ashoka's period, workshop of Mathura. Obverse: Symbols including a sun and an animal Reverse: Symbol Dimensions: 13.92 x 11.75 mm Weight: 3.4 g.Modern scholarship

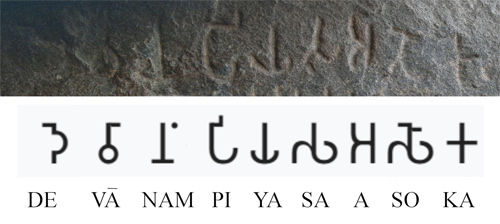

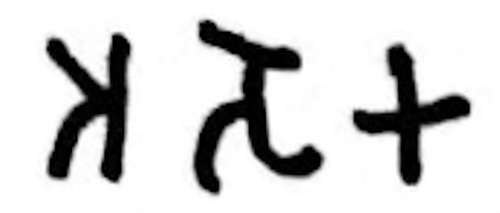

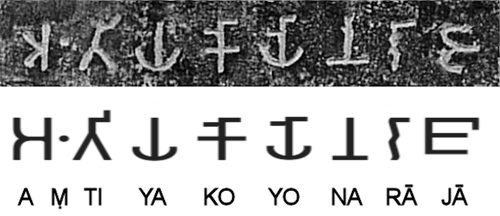

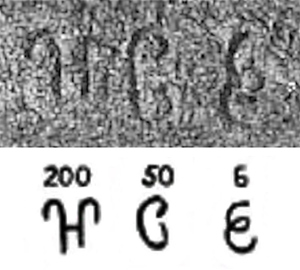

RediscoveryAshoka had almost been forgotten, but in the 19th century

James Prinsep contributed in the revelation of historical sources. After deciphering the Brahmi script,

Prinsep had originally identified the "Priyadasi" of the inscriptions he found with the King of Ceylon Devanampiya Tissa. However, in 1837, George Turnour discovered an important Sri Lankan manuscript (Dipavamsa, or "Island Chronicle") associating Piyadasi with Ashoka:"Two hundred and eighteen years after the beatitude of the Buddha, was the inauguration of Piyadassi, .... who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and the son of Bindusara, was at the time Governor of Ujjayani."

— Dipavamsa.[34]

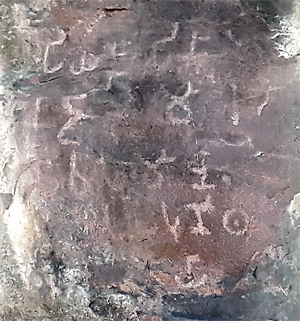

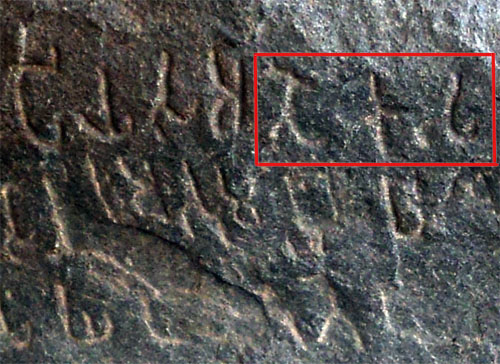

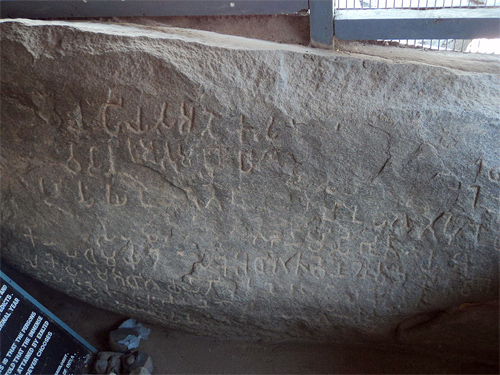

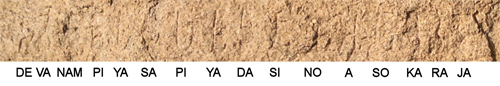

The Minor Rock Edict of Maski mentions the author as "Devanampriya Asoka", definitively linking both names, and confirming Ashoka as the author of the famous Edicts.Since then, the association of "Devanampriya Priyadarsin" with Ashoka was confirmed through various inscriptions, and especially confirmed in the Minor Rock Edict inscription discovered in Maski, directly associating Ashoka with his regnal title Devanampriya ("Beloved-of-the-Gods"

The Minor Rock Edict of Maski mentions the author as "Devanampriya Asoka", definitively linking both names, and confirming Ashoka as the author of the famous Edicts.Since then, the association of "Devanampriya Priyadarsin" with Ashoka was confirmed through various inscriptions, and especially confirmed in the Minor Rock Edict inscription discovered in Maski, directly associating Ashoka with his regnal title Devanampriya ("Beloved-of-the-Gods"):[217] [The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 42.] [218] [

Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). Ashoka. Penguin UK. p. 13.]

Asoka, the Sungas and the Andhras

After a reign of some twenty-five years, Bindusara was succeeded about 274 B.C. by his son, Asokavardhana, usually known as Asoka, whose importance in the eyes of Buddhists has given him a place in Indian history to which, from a political point of view, his grandfather is much more entitled. He is called Asokavardhana in the Puranas, and in Buddhist literature Asoka; in the only one of his inscriptions in which he refers to himself by name he is Asoka. In all his other inscriptions he is called Devanampriya, usually with the epithet Priyadarsin. The term Devanampriya, "dear to the gods" may be translated as "His Majesty"; from one of the rock edicts we learn that it was also used by his predecessors, and we find it in an inscription of his grandson, Dasaratha; in the Mudrarakshasa it is applied to his grandfather, Chandragupta. One other reference to Asoka is found, that in the Girnar inscription of the satrap Rudradaman, which calls him Asoka Maurya. It hardly required the recently discovered Maski inscription to confirm the identity of the Asoka of Buddhist tradition with the Priyadarsin or Piyadasi of the inscription. It is to these inscriptions, engraved on rock in various parts of his vast empire, that we owe the fact chat we have a picture of Asoka such as we possess of no other character in early Indian history. But although they throw some valuable light on the history of his reign, these inscriptions were not intended as historical documents.

For the events attending Asoka's accession our only source of information is Buddhist tradition.

-- The Cambridge Shorter History of India, p. 42.

The more he read, the more questions bedevilled Prinsep. Who was this King Piyadasi? At times he referred to himself as 'raja magadhe', so he must have ruled the kingdom of Magadha. None of the ancient Sanskrit lists of kings carried such a name. Then he got a lucky break. A scholar named George Turnour, working in Sri Lanka, was translating an ancient text called Mahavamsa and he discovered that there was a Lankan king named Piyadasi. But it was hard to believe that this king, ruling a tiny island south of the Indian subcontinent, could get inscriptions placed as far north as Bihar! The final link was again found in a Lankan text that explained that Piyadasi was a popular royal title and that the Lankan king shared it with another king who ruled at the same time in India. The two kings were allies and the text gave the real name of this Indian king. [NO CITATION!] A few decades later another inscription was discovered at Maski in Karnataka that confirmed it.Raja Devanam Piyadasi's name was Ashoka.

-- Chapter 1. Discovering Ashoka, Excerpt from "Ashoka: The Great and Compassionate King", by Subhadra Sen Gupta

[A proclamation] of Devanampriya Asoka.

Two and a half years [and somewhat more] (have passed) since I am a Buddha-Sakya.

[A year and] somewhat more (has passed) [since] I have visited the Samgha and have shown zeal.

Those gods who formerly had been unmingled (with men) in Jambudvipa, have how become mingled (with them).

This object can be reached even by a lowly (person) who is devoted to morality.

One must not think thus, – (viz.) that only an exalted (person) may reach this.

Both the lowly and the exalted must be told : "If you act thus, this matter (will be) prosperous and of long duration, and will thus progress to one and a half.

— Maski Minor Rock Edict of Ashoka.[219]

Another important historian was British archaeologist John Hubert Marshall, who was director-General of the

Archaeological Survey of India. His main interests were Sanchi and Sarnath, in addition to Harappa and Mohenjodaro.

Sir Alexander Cunningham, a British archaeologist and army engineer, and often known as the father of the Archaeological Survey of India, unveiled heritage sites like the Bharhut Stupa, Sarnath, Sanchi, and the Mahabodhi Temple. Mortimer Wheeler, a British archaeologist, also exposed Ashokan historical sources, especially the Taxila.

Perceptions and historiographyThe use of Buddhist sources in reconstructing the life of Ashoka has had a strong influence on perceptions of Ashoka, as well as the interpretations of his Edicts. Building on traditional accounts, early scholars regarded Ashoka as a primarily Buddhist monarch who underwent a conversion to Buddhism and was actively engaged in sponsoring and supporting the Buddhist monastic institution. Some scholars have tended to question this assessment. Romila Thappar writes about Ashoka that "We need to see him both as a statesman in the context of inheriting and sustaining an empire in a particular historical period, and as a person with a strong commitment to changing society through what might be called the propagation of social ethics."[220]

The only source of information not attributable to Buddhist sources are the Ashokan Edicts, and these do not explicitly state that Ashoka was a Buddhist. In his edicts, Ashoka expresses support for all the major religions of his time: Buddhism, Brahmanism, Jainism, and Ajivikaism, and his edicts addressed to the population at large (there are some addressed specifically to Buddhists; this is not the case for the other religions) generally focus on moral themes members of all the religions would accept. For example, Amartya Sen writes, "The Indian Emperor Ashoka in the third century BCE presented many political inscriptions in favor of tolerance and individual freedom, both as a part of state policy and in the relation of different people to each other".[221]

However,

the edicts alone strongly indicate that he was a Buddhist. In one edict he belittles rituals, and he banned Vedic animal sacrifices;

these strongly suggest that he at least did not look to the Vedic tradition for guidance. Furthermore, many edicts are expressed to Buddhists alone; in one, Ashoka declares himself to be an "upasaka", and in another he demonstrates a close familiarity with Buddhist texts. He erected rock pillars at Buddhist holy sites, but did not do so for the sites of other religions.

He also used the word "dhamma" to refer to qualities of the heart that underlie moral action; this was an exclusively Buddhist use of the word. However, he used the word more in the spirit than as a strict code of conduct. Romila Thappar writes, "His dhamma did not derive from divine inspiration, even if its observance promised heaven. It was more in keeping with the ethic conditioned by the logic of given situations. His logic of Dhamma was intended to influence the conduct of categories of people, in relation to each other. Especially where they involved unequal relationships."[220] Finally, he promotes ideals that correspond to the first three steps of the Buddha's graduated discourse.[222]

Much of the knowledge about Ashoka comes from the several inscriptions that he had carved on pillars and rocks throughout the empire. All his inscriptions present him as compassionate and loving. In the Kalinga rock edits, he addresses his people as his "children" and mentions that as a father he desires their good.[223]

Impact of pacifismAfter Ashoka's death, the Maurya empire declined rapidly. The various Puranas provide different details about Ashoka's successors, but all agree that they had relatively short reigns. The empire seems to have weakened, fragmented, and suffered an invasion from the Bactrian Greeks.[147]

Some historians, such as H. C. Raychaudhuri, have argued that Ashoka's pacifism undermined the "military backbone" of the Maurya empire. Others, such as

Romila Thapar, have suggested that the extent and impact of his pacifism have been "grossly exaggerated".[224]

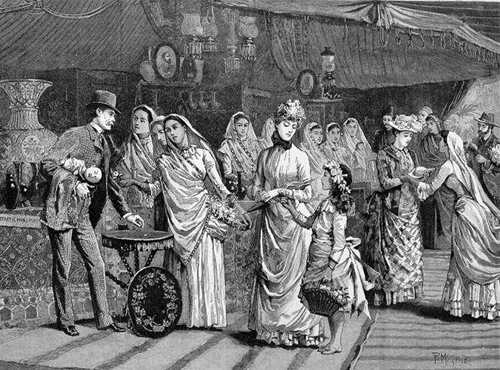

In art, film and literature  A c. 1910 painting by Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951) depicting Ashoka's queen standing in front of the railings of the Buddhist monument at Sanchi (Raisen district, Madhya Pradesh).

A c. 1910 painting by Abanindranath Tagore (1871–1951) depicting Ashoka's queen standing in front of the railings of the Buddhist monument at Sanchi (Raisen district, Madhya Pradesh).• Jaishankar Prasad composed Ashoka ki Chinta (Ashoka's Anxiety), a poem that portrays Ashoka's feelings during the war on Kalinga.

• Ashoka, a 1922 Indian silent historical film about the emperor produced by Madan Theatres.[225]

• The Nine Unknown, a 1923 novel by Talbot Mundy about the "Nine Unknown Men", a fictional secret society founded by Ashoka.

• Samrat Ashok, a 1928 Indian silent film by Bhagwati Prasad Mishra.[225]

• Ashok Kumar is a 1941 Indian Tamil-language film directed by Raja Chandrasekhar. The film stars Chittor V. Nagaiah as Ashoka.

• Samrat Ashok is a 1947 Indian Hindi-language film by K.B. Lall.[226]

• Uttar-Priyadarshi (The Final Beatitude), a verse-play written by poet Agyeya depicting his redemption, was adapted to stage in 1996 by theatre director, Ratan Thiyam and has since been performed in many parts of the world.[227][228]

• In 1973, Amar Chitra Katha released a graphic novel based on the life of Ashoka.

• In Piers Anthony's series of space opera novels, the main character mentions Ashoka as a model for administrators to strive for.

• Samrat Ashok is a 1992 Indian Telugu-language film about the emperor by N. T. Rama Rao with Rao also playing the titular role.[226]

• Aśoka is a 2001 epic Indian historical drama film directed and co-written by Santosh Sivan. The film stars Shah Rukh Khan as Ashoka.

• In 2002, Mason Jennings released the song "Emperor Ashoka" on his Living in the Moment EP. It is based on the life of Ashoka.

• In 2013, Christopher C. Doyle released his debut novel, The Mahabharata Secret, in which he wrote about Ashoka hiding a dangerous secret for the well-being of India.

• 2014's The Emperor's Riddles, a fiction mystery thriller novel by Satyarth Nayak, traces the evolution of Ashoka and his esoteric legend of the Nine Unknown Men.

• In 2015, Chakravartin Ashoka Samrat, a television serial by Ashok Banker, based on the life of Ashoka, began airing on Colors TV.

• Bharatvarsh is an Indian television historical documentary series, hosted by actor-director Anupam Kher on Hindi news channel ABP News. The series stars Aham Sharma as Ashoka.[229]

Notes1. The North Indian sources indicate Subhadrangi as the name of Ashoka's mother, while the Sri Lankan sources mention her as Dharma

References1. Lahiri 2015, pp. 295–296.

2. Singh 2017, p. 162.

3. Singh 2008, p. 331.

4. In his contemporary Maski Minor Rock Edict his name is written in the Brahmi script as Devanampriya Asoka. Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. pp. 174–175.

5. Chandra, Amulya (14 May 2015). "Ashoka | biography – emperor of India". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

6. Thapar 1980, p. 51.

7. Bentley 1993, p. 44.

8. Kalinga had been conquered by the preceding Nanda Dynasty but subsequently broke free until it was reconquered by Ashoka c. 260 BCE. (Raychaudhuri, H. C.; Mukherjee, B. N. 1996. Political History of Ancient India: From the Accession of Parikshit to the Extinction of the Gupta Dynasty. Oxford University Press, pp. 204–9, pp. 270–71)

9. Bentley 1993, p. 45.

10. Bentley 1993, p. 46.

11. Nayanjot Lahiri (5 August 2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-674-91525-1.

12. Thapar 1961, pp. 5–8.

13. Singh 2012, p. 132.

14. Kenneth Zysk. Ascetism And Healing in Ancient India Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery. Oxford University Press, 1991, 44. Link to book.

15. Singh 2012, p. 131.

16. Strong 1995, p. 141.

17. Thapar 1961, p. 8.

18. Thapar 1961, p. 7.

19. Thapar 1961, pp. 7–8.

20. Singh 2008, pp. 331–332.

21. Thapar 1961, pp. 8–9.

22. Strong 1989, p. 12.

23. Strong 1995, p. 143.

24. Strong 1995, p. 144.

25. Strong 1995, pp. 152–154.

26. Strong 1995, p. 155.

27. Strong 1995, pp. 154–157.

28. Thapar 1961, p. 11.

29. Thapar 1995, p. 15.

30. Thapar 1961, p. 9.

31. Guruge, Review 1995, pp. 185-188.

32. Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 226–250. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

33. Strong 1989, p. 205.

34. Allen 2012, p. 79.

35. The Dîpavaṃsa: An Ancient Buddhist Historical Record. Williams and Norgate. 1879. pp. 147–148.

36. Thapar 1961, pp. 226–227.

37. Strong 1989, p. 11.

38. Lahiri 2015, p. 129.

39. Thapar 1961, p. 226.

40. Lahiri 2015, p. 27.

41. Singh 2008, p. 332.

42. Lahiri 2015, p. 25.

43. Lahiri 2015, p. 24.

44. Lahiri 2015, p. 26.

45. Thapar 1961, p. 13.

46. Strong 1989, p. 204.

47. Thapar 1961, pp. 25–26.

48. Strong 1989, pp. 204–205.

49. Lahiri 2015, p. 323:"In the Ashokavadana, Ashoka's mother is not named."

50. Lahiri 2015, p. 31.

51. Guruge 1993, p. 19.

52. Mookerji 1962, p. 2.

53. Thapar 1961, p. 20.

54. Strong 1989, p. 206.

55. Strong 1989, p. 207.

56. Thapar 1961, p. 21.

57. Lahiri 2015, p. 65.

58. Strong 1989, p. 208.

59. Lahiri 2015, p. 66.

60. Lahiri 2015, p. 70.

61. Lahiri 2015, p. 66-67.

62. Lahiri 2015, p. 68.

63. Lahiri 2015, p. 67.

64. Lahiri 2015, pp. 89–90.

65. Allen 2012, p. 154.

66. Guruge 1993, p. 28.

67. Lahiri 2015, p. 98.

68. Lahiri 2015, pp. 94–95.

69. Thapar 1961, pp. 22–23.

70. Lahiri 2015, p. 101.

71. Lahiri 2015, p. 97.

72. Thapar 1961, pp. 24–25.

73. Thapar 1961, p. 25.

74. Lahiri 2015, p. 102.

75. Strong 1989, p. 209.

76. Strong 1989, p. 210.

77. Thapar 1961, p. 26.

78. Thapar 1961, p. 27.

79. Thapar 1961, pp. 13–14.

80. Thapar 1961, p. 14.

81. Thapar 1961, p. 30.

82. Strong 1989, pp. 12–13.

83. Strong 1989, p. 13.

84. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 46.

85. Thapar 1961, p. 29.

86. Lahiri 2015, p. 105.

87. Lahiri 2015, p. 106.

88. Lahiri 2015, pp. 106–107.

89. Lahiri 2015, p. 107.

90. Charles Drekmeier (1962). Kingship and Community in Early India. Stanford University Press. pp. 173. ISBN 978-0-8047-0114-3. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

91. Indian Archaeology 1997–98 (PDF). ASI. p. Plate 72.

92. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, pp. 49–50.

93. Smith, Vincent (1920). Asoka: The Buddhist Emperor of India . Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 185 – via Wikisource.

94. Thapar 1995, p. 18.

95. Thapar 1961, p. 36.

96. Thapar 1961, p. 33.

97. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 38.

98. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 37.

99. Thapar 1995, pp. 30–31.

100. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 56.

101. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 42.

102. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 43.

103. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 47.

104. Lahiri 2015, p. 109.

105. Gombrich 1995, p. 7.

106. Thapar 1961, p. 34.

107. Lahiri 2015, p. 110.

108. Lahiri 2015, p. 108.

109. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 49.

110. Thapar 1961, p. 35.

111. Lahiri 2015, p. 135.

112. Strong 1995, pp. 154–155.

113. Mahâbodhi, Cunningham p.4ff

114. Allen 2012.

115. "Ashoka did build the Diamond Throne at Bodh Gaya to stand in for the Buddha and to mark the place of his enlightenment" in Ching, Francis D. K.; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (23 March 2017). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 570. ISBN 978-1-118-98160-3.

116. Strong 1995, p. 158.

117. Strong 1995, p. 159.

118. Gombrich 1995, pp. 6–7.

119. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 50.

120. Gombrich 1995, p. 8.

121. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 51.

122. Gombrich 1995, pp. 8–9.

123. Gombrich 1995, p. 5.

124. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 45.

125. Gombrich 1995, p. 10.

126. Gombrich 1995, p. 6.

127. Gombrich 1995, pp. 10–11.

128. Gombrich 1995, p. 11.

129. Gombrich 1995, pp. 11–12.

130. Gombrich 1995, p. 12.

131. Thapar 1995, p. 32.

132. Thapar 1995, p. 36.

133. Strong 1995, p. 149.

134. Thapar 1961, p. 28.

135. Strong 1989, p. 232.

136. Beni Madhab Barua (5 May 2010). The Ajivikas. General Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-152-74433-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

137. Steven L. Danver (22 December 2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. ABC-CLIO. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

138. Le Phuoc (March 2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

139. Strong 1995, p. 152.

140. Strong 1995, pp. 152–153.

141. Strong 1995, p. 153.

142. Strong 1995, p. 151.

143. Strong 1995, p. 165.

144. Kosmin 2014, p. 36.

145. Strong 1989, p. 18.

146. Strong, John (2007). Relics of the Buddha. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 149. ISBN 978-81-208-3139-1.

147. Singh 2008, p. 333.

148. Mookerji 1962, p. 9.

149. Strong 1995, pp. 146–147.

150. Strong 1995, p. 166.

151. Strong 1995, p. 167.

152. Strong 1995, pp. 167–168.

153. Thapar 1961, p. 23.

154. Lahiri 2015, p. 97-98.

155. Thapar 1961, p. 22.

156. Thapar 1961, p. 24.

157. Thapar 1961, pp. 23–24.

158. Thapar 1961, pp. 27–28.

159. Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

160. Gombrich 1995, p. 1.

161. Strong 1989, p. 15.

162. Strong 1995, p. 142.

163. Lahiri 2015, p. 134.

164. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, pp. 43–44.

165. Gombrich 1995, p. 3.

166. Thapar 1995, pp. 19–20.

167. Guruge, Unresolved 1995, p. 44.

168. Lahiri 2015, p. 157.

169. Thapar 1995, p. 29.

170. Strong 1989, p. 4.

171. Thapar 1961, p. 37.

172. Thapar 1995, p. 19.

173. Thapar 1995, pp. 20–21.

174. Thapar 1995, p. 20.

175. Thapar 1995, p. 31.

176. Thapar 1995, pp. 21–22.

177. Strong 1989, pp. 3–4.

178. Strong 1989, p. 5.

179. Strong 1989, pp. 6–9.

180. Strong 1989, pp. 9–10.

181. Fitzgerald 2004, p. 120.

182. Simoons, Frederick J. (1994). Eat Not This Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present(2nd ed.). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-299-14254-4.

183. "The Edicts of King Asoka". Translated by Dhammika, Ven. S. Buddhist Publication Society. 1994. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

184. D.R. Bhandarkar, R. G. Bhandarkar (2000). Asoka. Asian Educational Services. pp. 314–315. ISBN 9788120613331.

185. Gerald Irving A. Dare Draper; Michael A. Meyer; H. McCoubrey (1998). Reflections on Law and Armed Conflicts: The Selected Works on the Laws of War by the Late Professor Colonel G.I.A.D. Draper, Obe. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 44. ISBN 978-90-411-0557-8. Retrieved 30 October2012.

186. Phelps, Norm (2007). The Longest Struggle: Animal Advocacy from Pythagoras to Peta. Lantern Books. ISBN 978-1590561065.

187. Kosmin 2014, p. 57.

188. Thomas Mc Evilly "The shape of ancient thought", Allworth Press, New York, 2002, p.368

189. Oskar von Hinüber (2010). "Did Hellenistic Kings Send Letters to Aśoka?". Journal of the American Oriental Society. Freiburg. 130 (2): 262–265.

190. The Edicts of King Ashoka: an English rendering by Ven. S. Dhammika Archived 10 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Access to Insight: Readings in Theravāda Buddhism. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

191. Pliny the Elder, "The Natural History", 6, 21

192. Preus, Anthony (2015). Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Philosophy. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-4422-4639-3.

193. Full text of the Mahavamsa Click chapter XII Archived 5 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

194. The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology by Upinder Singh p.18

195. De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages(9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 428. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

196. Strong 1995, p. 146.

197. Strong 1995, p. 147.

198. Strong 1995, p. 163.

199. Strong 1995, p. 163-165.

200. Introduction to Indian Architecture Bindia Thapar, Tuttle Publishing, 2012, p.21 "Ashoka used the knowledge of stone craft to begin the tradition of stone architecture in India, dedicated to Buddhism."

201. Gardner's Art through the Ages: Non-Western Perspectives, Fred S. Kleiner, Cengage Learning, 2009, p14

202. Mookerji 1962, p. 96.

203. "Ashoka was known to be a great builder who may have even imported craftsmen from abroad to build royal monuments." Monuments, Power and Poverty in India: From Ashoka to the Raj, A. S. Bhalla, I.B.Tauris, 2015 p.18 [1]

204. Reference: "India: The Ancient Past" p.113, Burjor Avari, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-35615-6

205. Singh 2012.

206. Lahiri 2015, pp. 120–121.

207. Lahiri 2015, p. 126.

208. Thapar 1961, p. 6.

209. Lahiri 2015, p. 143.

210. Thapar 1995, p. 23.

211. Lahiri 2015, pp. 143–157.

212. Lahiri 2015, p. 127.

213. Lahiri 2015, p. 133.

214. Indian Numismatics, Damodar Dharmanand Kosambi, Orient Blackswan, 1981, p.73 [2]

215. Malwa Through the Ages, from the Earliest Times to 1305 A.D, Kailash Chand Jain, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1972, p.134 [3]

216. Mitchiner, Michael (1978). Oriental Coins & Their Values: The Ancient and Classical World 600 B.C. - A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-9041731-6-1.

217. The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 42.

218. Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). Ashoka. Penguin UK. p. 13. ISBN 9788184758078.

219. Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. pp. 174–175.

220. Thappar, Romila (13 November 2009). "Ashoka – A Retrospective". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (45): 31–37.

221. Sen, Amartya (Summer 1998). "Universal Truths and the Westernizing Illusion". Harvard International Review. 20 (3): 40–43.

222. Richard Robinson, Willard Johnson, and Thanissaro Bhikkhu, Buddhist Religions, fifth ed., Wadsworth 2005, page 59.

223. The Edicts of King Ashoka Archived 28 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, English translation (1993) by Ven. S. Dhammika. ISBN 955-24-0104-6. Retrieved 21 February 2009

224. Singh 2012, p. 131, 143.

225. R. K. Verma (2000). Filmography: Silent Cinema, 1913-1934. M. Verma. p. 150. ISBN 978-81-7525-224-0.

226. Ashish Rajadhyaksha; Paul Willemen (10 July 2014). Encyclopedia of Indian Cinema. Taylor & Francis. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-135-94325-7.

227. Jefferson, Margo (27 October 2000). "Next Wave Festival Review; In Stirring Ritual Steps, Past and Present Unfold". The New York Times.

228. Renouf, Renee (December 2000). "Review: Uttarpriyadarshi". Balletco. Archived from the originalon 5 February 2012.

229. "'Bharatvarsh' – ABP News brings a captivating saga of legendary Indians with Anupam Kher". 19 August 2016. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016.

Bibliography• Allen, Charles (2012). Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor. Hachette. ISBN 978-1-408-70388-5.

• Bentley, Jerry (1993). Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195076400.

• Fitzgerald, James L., ed. (2004). The Mahabharata. 7. The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-25250-7.

• Gombrich, Richard (1995). "Aśoka – The Great Upāsaka". In Anuradha Seneviratna (ed.). King Aśoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.

• Guruge, Ananda W. P. (1993). Aśoka, the Righteous: A Definitive Biography. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN 978-955-9226-00-0.

• Guruge, Ananda W. P. (1995). "Emperor Aśoka and Buddhism: Unresolved Discrepancies between Buddhist Tradition & Aśokan Inscriptions". In Anuradha Seneviratna (ed.). King Aśoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.

• Guruge, Ananda W. P. (1995). "Emperor Aśoka's Place in History: A Review of Prevalent Opinions". In Anuradha Seneviratna (ed.). King Aśoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.

• Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0

• Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674057777.

• Mookerji, Radhakumud (1962). Aśoka (3rd revised ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0582-8.

• Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97527-9.

• Singh, Upinder (2008). A history of ancient and early medieval India : from the Stone Age to the 12th century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

• Singh, Upinder (2012). "Governing the State and the Self: Political Philosophy and Practice in the Edicts of Aśoka". South Asian Studies. University of Delhi. 28 (2): 131–145. doi:10.1080/02666030.2012.725581. S2CID 143362618.

• Strong, John S. (1995). "Images of Aśoka: Some Indian and Sri Lankan Legends and their Development". In Anuradha Seneviratna (ed.). King Aśoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.

• Strong, John S. (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0.

• Thapar, Romila (1995). "Aśoka and Buddhism as Reflected in the Aśokan Edicts". In Anuradha Seneviratna (ed.). King Aśoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.

• Thapar, Romila (1961). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. Oxford University Press. OCLC 736554.

• Thapar, Romila (1980) [First published 1961]. Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. OCLC 736554. SBN 19-660379 6.

Further reading• India portal

• Religion portal

• History portal

• Biography portal

• Harry Falk (2006). Aśokan Sites and Artefacts: A Source-book with Bibliography. Von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-3712-0.

• Patrick Olivelle; Janice Leoshko; Himanshu Prabha Ray (2012). Reimagining Asoka: Memory and History. Oxford University Press India. ISBN 978-0-19-807800-5.

• E. Hultzsch (1925). Inscriptions of Asoka: New Edition. Government of India.

• Rongxi, Li (1993). The Biographical Scripture of King Aśoka: Translated from the Chinese of Saṃghapāla (PDF). Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. ISBN 978-0-9625618-4-9.

• Nikam, N. A.; McKeon, Richard (1959). The Edicts of Aśoka. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

• James Merry MacPhail (1918). Asoka. London: Oxford University Press.

External links• Media related to Ashoka at Wikimedia Commons

• Quotations related to Ashoka at Wikiquote

• Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Asoka" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

• Ashoka at the Encyclopædia Britannica

• Ashoka at Curlie

• BBC Radio 4: Sunil Khilnani, Incarnations: Ashoka.

• BBC Radio 4: Melvyn Bragg with Richard Gombrich et al., In Our Time, Ashoka the Great.