Part 2 of 2

Ramlila and DussehraMain article: Vijayadashami

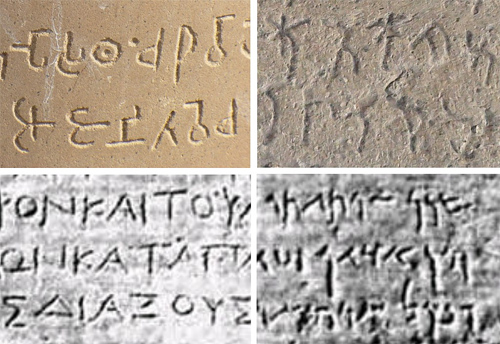

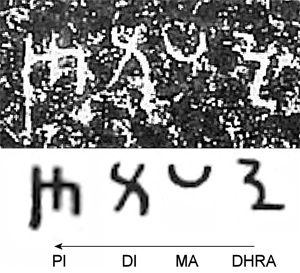

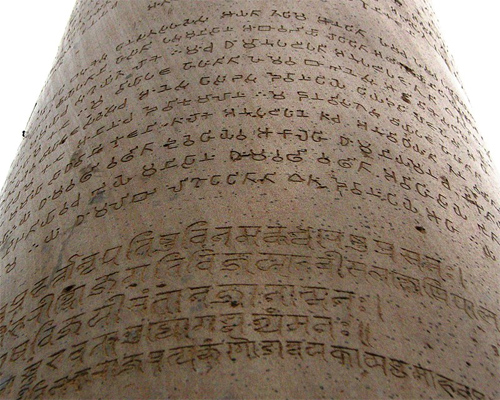

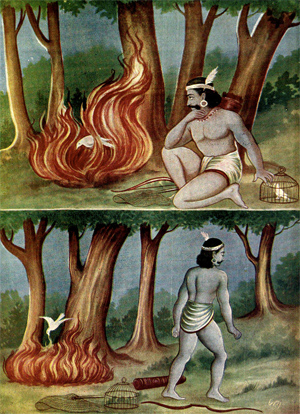

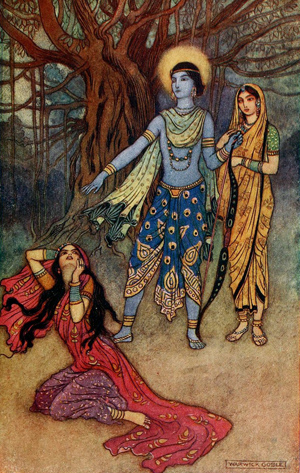

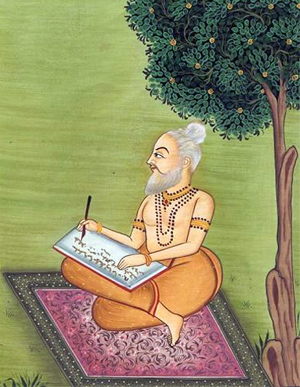

In Northern, Central and Western states of India, the Ramlila play is enacted during Navratri by rural artists (above).

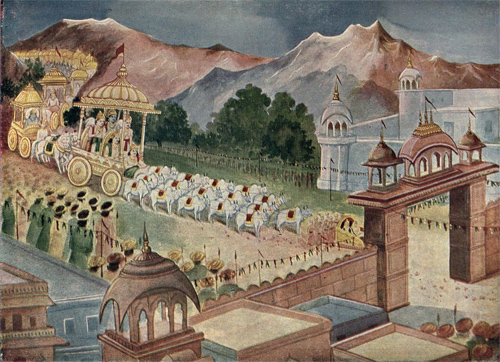

In Northern, Central and Western states of India, the Ramlila play is enacted during Navratri by rural artists (above).Rama's life is remembered and celebrated every year with dramatic plays and fireworks in autumn. This is called Ramlila, and the play follows Ramayana or more commonly the Ramcharitmanas.[130] It is observed through thousands[18] of Rama-related performance arts and dance events, that are staged during the festival of Navratri in India.[131] After the enactment of the legendary war between Good and Evil, the Ramlila celebrations climax in the Dussehra (Dasara, Vijayadashami) night festivities where the giant grotesque effigies of Evil such as of demon Ravana are burnt, typically with fireworks.[98][132]

The Ramlila festivities were declared by UNESCO as one of the "Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity" in 2008. Ramlila is particularly notable in historically important Hindu cities of Ayodhya, Varanasi, Vrindavan, Almora, Satna and Madhubani – cities in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh.[98][133] The epic and its dramatic play migrated into southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE, and Ramayana based Ramlila is a part of performance arts culture of Indonesia, particularly the Hindu society of Bali, Myanmar, Cambodia and Thailand.[134]

DiwaliMain article: Diwali

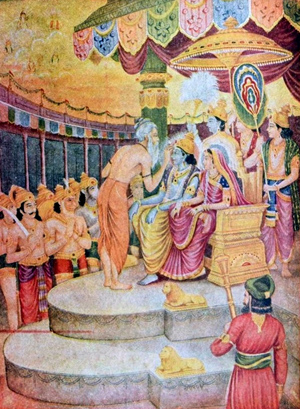

In some parts of India, Rama's return to Ayodhya and his coronation is the main reason for celebrating Diwali, also known as the Festival of Lights.[135]

In Guyana, Diwali is marked as a special occasion and celebrated with a lot of fanfare. It is observed as a national holiday in this part of the world and some ministers of the Government also take part in the celebrations publicly. Just like Vijayadashmi, Diwali is celebrated by different communities across India to commemorate different events in addition to Rama's return to Ayodhya. For example, many communities celebrate one day of Diwali to celebrate the Victory of Krishna over the demon Narakasur.[ε]

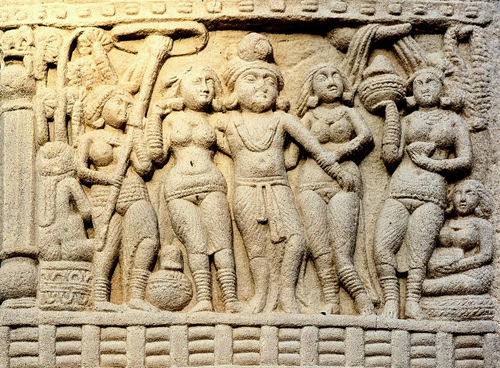

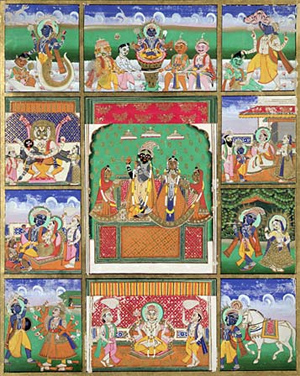

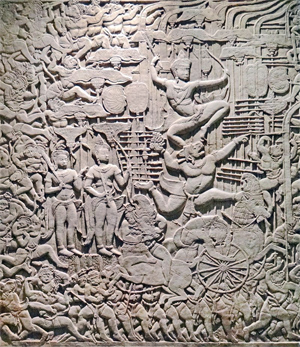

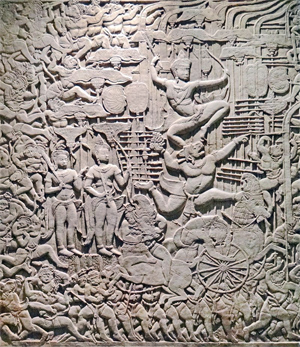

Hindu arts in Southeast Asia Rama's story is a major part of the artistic reliefs found at Angkor Wat, Cambodia. Large sequences of Ramayana reliefs are also found in Java, Indonesia.[137]

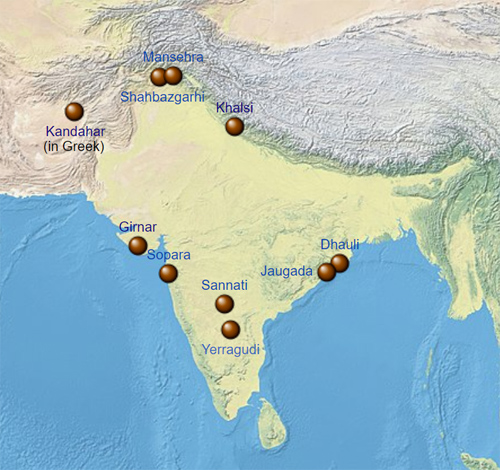

Rama's story is a major part of the artistic reliefs found at Angkor Wat, Cambodia. Large sequences of Ramayana reliefs are also found in Java, Indonesia.[137]Rama's life story, both in the written form of Sanskrit Ramayana and the oral tradition arrived in southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE.[138] Rama was one of many ideas and cultural themes adopted, others being the Buddha, the Shiva and host of other Brahmanic and Buddhist ideas and stories.[139] In particular, the influence of Rama and other cultural ideas grew in Java, Bali, Malaya, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos.[139]

The Ramayana was translated from Sanskrit into old Javanese around 860 CE, while the performance arts culture most likely developed from the oral tradition inspired by the Tamil and Bengali versions of Rama-based dance and plays.[138] The earliest evidence of these performance arts are from 243 CE according to Chinese records. Other than the celebration of Rama's life with dance and music, Hindu temples built in southeast Asia such as the Prambanan near Yogyakarta (Java), and at the Panataran near Blitar (East Java), show extensive reliefs depicting Rama's life.[138][140] The story of Rama's life has been popular in Southeast Asia.[141]

In the 14th century, the Ayutthaya Kingdom and its capital Ayuttaya was named after the Hindu holy city of Ayodhya, with the official religion of the state being Theravada Buddhism.[142][143] Thai kings, continuing into the contemporary era, have been called Rama, a name inspired by Rama of Ramakien – the local version of Sanskrit Ramayana, according to Constance Jones and James Ryan. For example, King Chulalongkorn (1853-1910) is also known as Rama V, while King Vajiralongkorn who succeeded to the throne in 2016 is called Rama X.[144]

JainismSee also: Rama in Jainism and Salakapurusa

In Jainism, the earliest known version of Rama story is variously dated from the 1st to 5th century CE. This Jaina text credited to Vimalasuri shows no signs of distinction between Digambara-Svetambara (sects of Jainism), and is in a combination of Marathi and Sauraseni languages. These features suggest that this text has ancient roots.[145]

In Jain cosmology, characters continue to be reborn as they evolve in their spiritual qualities, until they reach the Jina state and complete enlightenment. This idea is explained as cyclically reborn triads in its Puranas, called the Baladeva, Vasudeva and evil Prati-vasudeva.[146][147] Rama, Lakshmana and evil Ravana are the eighth triad, with Rama being the reborn Baladeva, and Lakshmana as the reborn Vasudeva.[61] Rama is described to have lived long before the 22nd Jain Tirthankara called Neminatha. In the Jain tradition, Neminatha is believed to have been born 84,000 years before the 9th-century BCE Parshvanatha.[148]

Jain texts tell a very different version of the Rama legend than the Hindu texts such as by Valmiki. According to the Jain version, Lakshmana (Vasudeva) is the one who kills Ravana (Prativasudeva).[61] Rama, after all his participation in the rescue of Sita and preparation for war, he actually does not kill, thus remains a non-violent person. The Rama of Jainism has numerous wives as does Lakshmana, unlike the virtue of monogamy given to Rama in the Hindu texts. Towards the end of his life, Rama becomes a Jaina monk then successfully attains siddha followed by moksha.[61] His first wife Sita becomes a Jaina nun at the end of the story. In the Jain version, Lakshmana and Ravana both go to the hell of Jain cosmology, because Ravana killed many, while Lakshmana killed Ravana to stop Ravana's violence.[61] Padmapurana mentions Rama as a contemporary of Munisuvrata, 20th tirthankara of Jainism.[149]

BuddhismThe Dasaratha-Jataka (Tale no. 461) provides a version of the Rama story. It calls Rama as Rama-pandita.[111][112]

At the end of this Dasaratha-Jataka discourse, the Buddhist text declares that the Buddha in his prior rebirth was Rama:

The Master having ended this discourse, declared the Truths, and identified the Birth (...): 'At that time, the king Suddhodana was king Dasaratha, Mahamaya was the mother, Rahula's mother was Sita, Ananda was Bharata, and I myself was Rama-Pandita.

— Jataka Tale No. 461, Translator: W.H.D. Rouse[112]

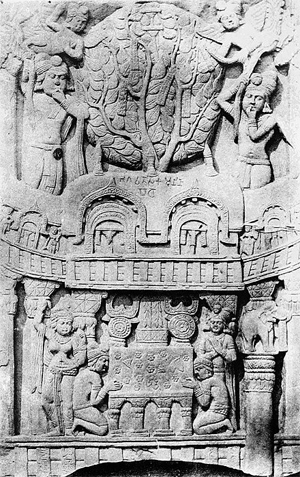

While the Buddhist Jataka texts co-opt Rama and make him an incarnation of Buddha in a previous life,[112] the Hindu texts co-opt the Buddha and make him an avatar of Vishnu.[150][151] The Jataka literature of Buddhism is generally dated to be from the second half of the 1st millennium BCE, based on the carvings in caves and Buddhist monuments such as the Bharhut stupa.[152][ζ] The 2nd-century BCE stone relief carvings on Bharhut stupa, as told in the Dasaratha-Jataka, is the earliest known non-textual evidence of Rama story being prevalent in ancient India.[154]

SikhismMain article: Rama in Sikhism

Rama is mentioned as one of twenty four divine incarnations of Vishnu in the Chaubis Avtar, a composition in Dasam Granth traditionally and historically attributed to Guru Gobind Singh.[10][η] The discussion of Rama and Krishna avatars is the most extensive in this section of the secondary Sikh scripture.[10][156] The name of Rama is mentioned more than 2,500 times in the Guru Granth Sahib[157] and is considered as avatar along with the Krishna.[η]

Among peopleIn Assam, Boro people call themselves Ramsa, which means Children of Ram.[158]

In Chhattisgarh, Ramnami people tattooed their whole body with name of Ram.[159]

Worship and temples

Worship The UNESCO World Heritage Site of Hampi monuments in Karnataka, built by the Vijayanagara Empire, includes a major Rama temple. Its numerous wall reliefs tell the life story of Rama.[160]

The UNESCO World Heritage Site of Hampi monuments in Karnataka, built by the Vijayanagara Empire, includes a major Rama temple. Its numerous wall reliefs tell the life story of Rama.[160] Rama Temple at Ramtek (10th century, restored). A medieval inscription here calls Rama as Advaitavadaprabhu or "Lord of the Advaita doctrine".[161]

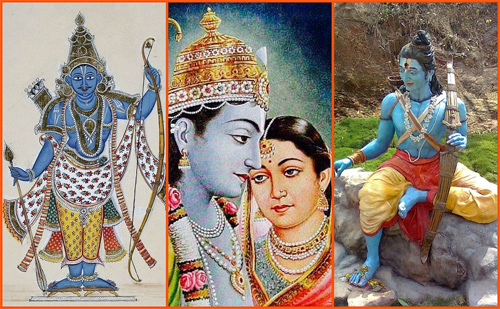

Rama Temple at Ramtek (10th century, restored). A medieval inscription here calls Rama as Advaitavadaprabhu or "Lord of the Advaita doctrine".[161]Rama is a revered Vaishanava deity, one who is worshipped privately at home or in temples. He was a part of the Bhakti movement focus, particularly because of efforts of 14th century North Indian poet-saint Ramananda who created the Ramanandi Sampradaya, a sannyasi community. This community has grown to become the largest Hindu monastic community in modern times.[162][163] This Rama-inspired movement has championed social reforms, accepting members without discriminating anyone by gender, class, caste or religion since the time of Ramananda who accepted Muslims wishing to leave Islam.[164][165] Traditional scholarship holds that his disciples included later Bhakti movement poet-saints such as Kabir, Ravidas, Bhagat Pipa and others.[165][166]

TemplesMain page: List of Rama temples

Temples dedicated to Rama are found all over India and in places where Indian migrant communities have resided. In most temples, the iconography of Rama is accompanied by that of his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana.[167] In some instances, Hanuman is also included either near them or in the temple premises.[168]

Hindu temples dedicated to Rama were built by early 5th century, according to copper plate inscription evidence, but these have not survived. The oldest surviving Rama temple is near Raipur (Chhattisgarh), called the Rajiva-locana temple at Rajim near the Mahanadi river. It is in a temple complex dedicated to Vishnu and dates back to the 7th-century with some restoration work done around 1145 CE based on epigraphical evidence.[169][170] The temple remains important to Rama devotees in the contemporary times, with devotees and monks gathering there on dates such as Rama Navami.[171]

Important Rama temples include:

• Rama temple, Ram Janmabhoomi, Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh.

• Nalambalam, Kerala.

• Bhadrachalam Temple, Telangana.

• Kodandarama Temple, Vontimitta, Andhra Pradesh.

• Ramateertham Temple, Andhra Pradesh.

• Ramaswamy Temple, Kumbakonam

• Mudikondan Kothandaramar Temple, Tamil Nadu.

• Vijayaraghava Perumal temple, Tamil Nadu.

• Sri Yoga Ramar Temple Nedungunam, Tamil Nadu.

• Shree Rama Temple, Triprayar, Kerala.

• Kalaram Temple, Nashik, Maharashtra.

• Raghunath Temple, Jammu.

• Ram Mandir, Bhubaneswar, Odisha.

• Kodandarama Temple, Chikmagalur, Karnataka.

• Kothandarama Temple, Thillaivilagam, Tamilnadu.

• Kothandaramaswamy Temple, Rameswaram, Tamil Nadu.

• Odogaon Raghunath Temple, Odisha.

• Ramchaura Mandir, Bihar.

• Sri Rama Temple, Ramapuram

• Vilwadrinatha Temple, Thiruvilwamala, Kerala.

Popular cultureSee also: Television series based on the Ramayana

Rama has been considered as a source of inspiration and has been described as Maryāda Puruṣottama Rāma (transl. The Ideal Man).[θ] He has been depicted in many films, television shows and plays.[172] The notable includes:-

• Ramayan in 1987, where the role was played by Arun Govil.[173]

• Ramayan (TV series) in 2002, where the role was played by Nitish Bharadwaj.[174]

• Ramayan NDTV series in 2008, where the role was played by Gurmeet Choudhary.

• Sankat Mochan Mahabali Hanumaan in 2015, where the role was played by Gagan Malik.[175]

• Ram Siya Ke Luv Kush in 2019, where the role was played by Himanshu Soni.[176]

See also• Ayodhya dispute

• Culture of India

• Genealogy of Rama

• Hindu philosophy

• Natyashastra

• Ram Nam

• Ram Statue

• Jai Shri Ram

• Ramayan (1987 TV series)

• Rama in Jainism

• Rama in Sikhism

• Ramayana

• Dashavatara

• Vaishnavism

References

Notes1. In English the Devanagari words are written after putting 'a' after them as per Schwa deletion in Indo-Aryan languages.[5]

2. The legends found about Rama, state Mallory and Adams, have "many of the elements found in the later Welsh tales such as Branwen Daughter of Llyr and Manawydan Son of Lyr. This may be because the concept and legends have deeper ancient roots.[32]

3. Kosala is mentioned in many Buddhist texts and travel memoirs. The Buddha idol of Kosala is important in the Theravada Buddhism tradition, and one that is described by the 7th-century Chinese pilgrim Xuanzhang. He states in his memoir that the statue stands in the capital of Kosala then called Shravasti, midst ruins of a large monastery. He also states that he brought back to China two replicas of the Buddha, one of the Kosala icon of Udayana and another the Prasenajit icon of Prasenajit.[41]

4. For example, like other Hindu poet-saints of the Bhakti movement before the 16th century, Tulsidas in Ramcharitmanas recommends the simplest path to devotion is Nam-simran (absorb oneself in remembering the divine name "Rama"). He suggests either vocally repeating the name (jap) or silent repetition in mind (ajapajap). This concept of Rama moves beyond the divinised hero and connotes an "all-pervading Being" and equivalent to atmarama within. The term atmarama is a compound of "Atma" and "Rama", it literally means "he who finds joy in his own self", according to the French Indologist Charlotte Vaudeville known for her studies on Ramayana and Bhakti movement.[95]

5. As per another popular tradition, in the Dvapara Yuga period, Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu, killed the demon Narakasura, who was the evil king of Pragjyotishapura, near present-day Assam and released 16000 girls held captive by Narakasura. Diwali was celebrated as a sign of the triumph of good over evil after Krishna's Victory over Narakasura. The day before Diwali is remembered as Naraka Chaturdasi, the day on which Narakasura was killed by Krishna.[136]

6. Richard Gombrich suggests that the Jataka tales were composed by the 3rd century BCE.[153]

7. Ath Beesvan Ram Avtar Kathan or Ram Avtar is a Composition in the second sacred Granth of Sikhs i.e Dasam Granth, which was written by Guru Gobind Singh, at Anandpur Sahib. Guru Gobind Singh was not a worshiper of Ramchandra, as after describing the whole Avtar he cleared this fact that ਰਾਮ ਰਹੀਮ ਪਰਾਨ ਕਰਾਨ ਅਨੇਕ ਕਹੈਂ ਮਤਿ ਝਕ ਨ ਮਾਨਿਯੋ ॥. Ram Avtar is based on Ramayana, but a Sikh studies the spiritual aspects of this whole composition.[155]

8.

o Blank 2000, p. 190

o Dodiya 2001, pp. 109–110

o Tripathy 2015, p. 1

Citations1. SATTAR, ARSHIA (20 October 2020). Maryada: Searching for Dharma in the Ramayana. HarperCollins Publishers, India. ISBN 978-93-5357-713-1.

2. "Dharma Personified". Retrieved 16 January 2021.

3. ames G. Lochtefeld 2002, p. 555.

4. "Rama". Webster's Dictionary. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

5. "Why we put 'a' after each Hindu name". Hinduism.Stackexchange. 16 October 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

6. Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

7. King, Anna S. (2005). The intimate other: love divine in Indic religions. Orient Blackswan. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-81-250-2801-7.

8. Matchett, Freda (2001). Krishna, Lord or Avatara?: the relationship between Krishna and Vishnu. 9780700712816. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

9. James G. Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 72-73.

10. Robin Rinehart 2011, pp. 14, 28–30.

11. Tulasīdāsa (1999). Sri Ramacaritamanasa. Translated by Prasad, RC. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 871–872. ISBN 978-81-208-0762-4.

12. William H. Brackney (2013). Human Rights and the World's Major Religions, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-1-4408-2812-6.

13. Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 95–124. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

14. Vālmīki (1990). The Ramayana of Valmiki: Balakanda. Translated by Goldman, Robert P. Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4008-8455-1.

15. Dimock Jr, E.C. (1963). "Doctrine and Practice among the Vaisnavas of Bengal". History of Religions. 3 (1): 106–127. doi:10.1086/462474. JSTOR 1062079. S2CID 162027021.

16. Marijke J. Klokke (2000). Narrative Sculpture and Literary Traditions in South and Southeast Asia. BRILL. pp. 51–57. ISBN 90-04-11865-9.

17. Ramdas Lamb 2012, p. 28.

18. Schechner, Richard; Hess, Linda (1977). "The Ramlila of Ramnagar [India]". The Drama Review: TDR. The MIT Press. 21 (3): 51–82. doi:10.2307/1145152. JSTOR 1145152.

19. James G. Lochtefeld 2002, p. 389.

20. Jennifer Lindsay (2006). Between Tongues: Translation And/of/in Performance in Asia. National University of Singapore Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-9971-69-339-8.

21. Roshen Dalal 2010, pp. 337-338. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRoshen_Dalal2010 (help)

22. Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 508. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

23. "Monier-Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary --र". sanskrit.inria.fr. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

24. Asko Parpola (1998). Studia Orientalia, Volume 84. Finnish Oriental Society. p. 264. ISBN 978-951-9380-38-4.

25. Thomas William Rhys Davids; William Stede (1921). Pali-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 521. ISBN 978-81-208-1144-7.

26. Wagenaar, Hank W.; Parikh, S. S. (1993). Allied Chambers transliterated Hindi-Hindi-English dictionary. Allied Publishers. p. 528. ISBN 978-81-86062-10-4.

27. "Ayodhya Case Verdict: Who is Ram Lalla Virajman, the 'Divine Infant' Given the Possession of Disputed Ayodhya Land". News18. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

28. Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2001). Sītāpaharaṇam: Changing thematic Idioms in Sanskrit and Tamil. In Dirk W. Lonne ed. Tofha-e-Dil: Festschrift Helmut Nespital, Reinbeck, 2 vols., pp. 783-97. pp. 783–797. ISBN 3-88587-033-9.

29. Ramdas Lamb 2012, p. 31.

30. Adams; Douglas Q. Adams (2013). A Dictionary of Tocharian B: Revised and Greatly Enlarged. Rodopi. p. 587. ISBN 978-90-420-3671-0.

31. Maloory and en 1997, p. 160.

32. Maloory and en 1997, p. 165.

33. Vālmīki; Sheldon I. Pollock (2007). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Araṇyakāṇḍa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 41 with footnote 83. ISBN 978-81-208-3164-3.

34. Rinehart, Robin (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. pp. 139, 388. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

35. A. W. P. Guruge (1991). The Society of the Ramayana. Abhinav Publications. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-81-7017-265-9.

36. Valmiki Ramayana, Bala Kanda

37. Cort, John (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 313 note 9. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8.

38. Winternitz, Moriz (1981). A History of Indian Literature, Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. pp. 491–492. ISBN 81-208-0264-0.

39. John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–162, 196, 314 note 14, 318 notes 57–58. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8., Quote (p. 314): "(...) Kosala was the kingdom centered on Ayodhya, in what is now east-central Uttar Pradesh."

40. Peter van der Veer (1994). Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India. University of California Press. pp. 157–162. ISBN 978-0-520-08256-4.

41. John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 194–200, 318 notes 57–58. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8.

42. Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

43. Roshen Dalal 2010, pp. 326–327harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRoshen_Dalal2010 (help)

44. Roshen Dalal 2010, pp. 99, 326–327harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRoshen_Dalal2010 (help)

45. Hindery 1978, pp. 98–99

46. B. A van Nooten William (2000). Ramayana. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22703-3.

47. Goldman 1996, p. 406:

16. ... Ravana is represented as merely requesting that Sita stop thinking of him as an enemy and that she abandon her mistaken notion that he wants her to be his wife. By mentioning his chief queen, he is really saying that he wants Sita to be the chosen goddess of both him and his chief queen, Mandodari.

48. Goldman 1996, p. 90.

49. Ramashraya Sharma (1986). A Socio-political Study of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-81-208-0078-6.

50. Gregory Claeys (2010). The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-1-139-82842-0.

51. Self-realization Magazine. Self-Realization Fellowship. 1971. pp. 50.

52. Hindery 1978, p. 100.

53. Hess, L. (2001). "Rejecting Sita: Indian Responses to the Ideal Man's Cruel Treatment of His Ideal Wife". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 67 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1093/jaarel/67.1.1. PMID 21994992.

54. Frye, Northrope (2015). Northrop Frye's Uncollected Prose. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-4426-4972-9.

55. Rooney, Dawn F. (2017). The Thiri Rama: Finding Ramayana in Myanmar. Taylor & Francis. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-315-31395-5.

56. Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 7–9 (by Richman), pp. 22–46 (Ramanujan). ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

57. A. N. Jani (2005). Kodaganallur R.S. Iyengar (ed.). Asian Variations in Ramayana: Papers Presented at the International Seminar on 'Variations in Ramayana in Asia. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 29–55. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

58. Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 10–12, 67–85. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

59. Monika Horstmann (1991). Rāmāyaṇa and Rāmāyaṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 9–21. ISBN 978-3-447-03116-5.

60. Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 11–12, 89–108. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

61. Padmanabh S Jaini (1993). Wendy Doniger (ed.). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. State University of New York Press. pp. 216–219. ISBN 978-0-7914-1381-4.

62. Umakant P. Shah (2005). Kodaganallur R.S. Iyengar (ed.). Asian Variations in Ramayana: Papers Presented at the International Seminar on 'Variations in Ramayana in Asia. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 57–76. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

63. Kapila Vatsyayan (2004). Mandakranta Bose (ed.). The Ramayana Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 335–339. ISBN 978-0-19-516832-7.

64. Menon 2008, pp. 10-11.

65. Pattanaik, Devdutt (8 August 2020). "Was Ram born in Ayodhya". mumbaimirror.

66. Dhirajlal Sankalia, Hasmukhlal (1982). The Ramayana in historical perspective. India(branch): Macmillan Publishers. pp. 4–5, 51. ISBN 9-780-333-90390-2.

67. Parmeshwaranand, Swami (2001a). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas. Swarup & Sons. ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3.

68. Simanjuntak, Truman (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. p. 361.

69. John Brockington; Mary Brockington (2016). The Other Ramayana Women: Regional Rejection and Response. Routledge. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-1-317-39063-3.

70. Valmiki Ramayan, p. kishkindha kanda.

71. Valmiki Ramayan, p. 1235 (Volume 2 of Śrīmad Vālmīki-Rāmāyaṇa: With Sanskrit Text and English Translation)

72. T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 189–193. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

73. Vālmīki; Pollock, Sheldon I. (2007). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Araṇyakāṇḍa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-81-208-3164-3.

74. Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 103–106. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

75. Gavin Flood (17 April 2008). THE BLACKWELL COMPANION TO HINDUISM. ISBN 978-81-265-1629-2.

76. Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

77. Valmiki Ramayan.

78. Timm, Jeffrey R. (1 January 1992). Texts in Context: Traditional Hermeneutics in South Asia. SUNY Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-7914-0796-7.

79. Griffith.

80. Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

81. Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

82. "The Oral Tradition and the many 'Ramayanas'", Moynihan @Maxwell, Maxwell School of Syracuse University's South Asian Center

83. John Nicol Farquhar (1920). An Outline of the Religious Literature of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 324–325.

84. Rocher 1986, pp. 158-159 with footnotes.

85. RC Prasad (1989). Tulasīdāsa's Sriramacharitmanasa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. xiv–xv, 875–876. ISBN 978-81-208-0443-2.

86. R. Barz (1991). Monika Horstmann (ed.). Rāmāyaṇa and Rāmāyaṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-3-447-03116-5.

87. James 2002, p. 72.

88. Ramcharitmanas, Encyclopaedia Britannica (2012)

89. Lutgendorf 1991.

90. Miller 2008, p. 217

91. Varma 2010, p. 1565

92. Poddar 2001, pp. 26–29

93. Das 2010, p. 63

94. Schomer & McLeod 1987, p. 75.

95. Schomer & McLeod 1987, pp. 31-32 with footnotes 13 and 16 (by C. Vaudeville)..

96. Schomer & McLeod 1987, pp. 31, 74-75 with footnotes, Quote: "What is striking about the dohas in the Ramcharitmanas however is that they frequently have a sant-like ring to them, breaking into the very midst of the saguna narrative with a statement of nirguna reality"..

97. A Kapoor (1995). Gilbert Pollet (ed.). Indian Epic Values: Rāmāyaṇa and Its Impact. Peeters Publishers. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-90-6831-701-5.

98. "Ramlila-The traditional performance of Ramayana". UNESCO. Retrieved 8 March2021.

99. Chapple 1984, pp. x-xi with footnote 4

100. Chapple 1984, pp. ix-xi

101. Leslie 2003, pp. 105

102. Chapple 1984, p. x

103. Chapple 1984, pp. xi-xii

104. Surendranath Dasgupta, A History of Indian Philosophy, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-04779-1, pages 252-253

105. Venkatesananda, S (Translator) (1984). The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-955-8.

106. Tigunait, Rajmani (2002). The Himalayan Masters: A Living Tradition. Itanagar: Himalayan Institute Press. pp. 33. ISBN 978-0-89389-227-2.

107. White, David Gordon (2014). The "Yoga Sutra of Patanjali": A Biography. Princeton University Press. pp. xvi–xvii, 51. ISBN 978-0-691-14377-4.

108. Edmour J. Babineau (1979). Love of God and Social Duty in the Rāmcaritmānas. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-89684-050-8.

109. Bhaṭṭi (600) [2009]. Bhaṭṭikāvya. Translated by Olliver, Fallon. New York, United States: Clay Sanskrit Library. p. 22.35. ISBN 978-0-8147-2778-2.

110. Roshen Dalal 2010, p. 323 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFRoshen_Dalal2010 (help).

111. H. T. Francis; E. J. Thomas (1916). Jataka Tales. Cambridge University Press (Reprinted: 2014). pp. 325–330. ISBN 978-1-107-41851-6.

112. Cowell, E. B.; Rouse, WHD (1901). The Jātaka: Or, Stories of the Buddha's Former Births. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–82.

113. Jaiswal, Suvira (1993). "Historical Evolution of Ram Legend". Social Scientist. 21 (3 / 4 March April 1993): 89–96. doi:10.2307/3517633. JSTOR 3517633.

114. Rocher 1986, p. 84 with footnote 26.

115. Buitenen, J. A. B. van (1973). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 207–214. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

116. Richman, Paula (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 17 note 11. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

117. Goldman, Robert (2013). The Valmiki Ramayana (PDF). University of California, Berkeley, California: Center for South Asia Studies.

118. Sundaram, P S (2002). Kamba Ramayana. Penguin Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-93-5118-100-2.

119. James G. Lochtefeld 2002, p. 562.

120. "City News, Indian City Headlines, Latest City News, Metro City News". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

121. Ramnavami

122. "BBC - Religions - Hinduism: Rama Navami". BBC News. Retrieved 7 March2021.

123. "President and PM greet people as India observes Ram Navami today". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

124. "National Portal of India". Govt. of India. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

125. John, Josephine (8 April 2014). "Hindus around the world celebrate Ram Navami today". DNA India. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

126. "Sitamarhi | India". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 March 2021. A large Ramanavami fair, celebrating the birth of Lord Rama, is held in spring with considerable trade in pottery, spices, brass ware, and cotton cloth. A cattle fair held in Sitamarhi is the largest in Bihar state. The town is sacred as the birthplace of the goddess Sita (also called Janaki), the wife of Rama.

127. "Latest News, India News, Breaking News, Today's News Headlines Online". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

128. "City News, Indian City Headlines, Latest City News, Metro City News". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 April 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

129. Satpathy, Kriti Saraswat (14 April 2016). "Did you know these rituals of Ram Navami celebration in Karnataka?". India News, Breaking News | India.com. Retrieved 6 March2021.

130. James G. Lochtefeld 2002, p. 389.

131. Encyclopedia Britannica 2015.

132. Kasbekar, Asha (2006). Pop Culture India!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-636-7.

133. James G. Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 561-562.

134. Bose, Mandakranta (2004). The Ramayana Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 342–350. ISBN 978-0-19-516832-7.

135. Gupta 1991, p. fontcover.

136. Paula Richman 1991, p. 107. sfn error: multiple targets (3×): CITEREFPaula_Richman1991 (help)

137. Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. pp. 109–160. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

138. James R. Brandon (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 22–27. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

139. Brandon, James R. (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 15–21. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

140. Jan Fontein (1973), The Abduction of Sitā: Notes on a Stone Relief from Eastern Java, Boston Museum Bulletin, Vol. 71, No. 363 (1973), pp. 21-35

141. Kats, J. (1927). "The Ramayana in Indonesia". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. Cambridge University Press. 4 (3): 579. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00102976.

142. Francis D. K. Ching; Mark M. Jarzombek; Vikramaditya Prakash (2010). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-470-40257-3., Quote: "The name of the capital city [Ayuttaya] derives from the Hindu holy city Ayodhya in northern India, which is said to be the birthplace of the Hindu god Rama."

143. Michael C. Howard (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

144. Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

145. John E Cort (1993). Wendy Doniger (ed.). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. State University of New York Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7914-1381-4.

146. Jacobi, Herman (2005). Vimalsuri's Paumachariyam (2nd ed.). Ahemdabad: Prakrit Text Society.

147. Iyengar, Kodaganallur Ramaswami Srinivasa (2005). Asian Variations in Ramayana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

148. Zimmer 1953, p. 226.

149. Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 21-23.

150. Bassuk, Daniel E (1987). Incarnation in Hinduism and Christianity: The Myth of the God-Man. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-349-08642-9.

151. Edward Geoffrey Parrinder (1997). Avatar and Incarnation: The Divine in Human Form in the World's Religions. Oxford: Oneworld. pp. 19–24, 35–38, 75–78, 130–133. ISBN 978-1-85168-130-3.

152. Claus, Peter J.; Diamond, Sarah; Mills, Margarat (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 306–307. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

153. Naomi Appleton (2010). Jātaka Stories in Theravāda Buddhism: Narrating the Bodhisatta Path. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-1-4094-1092-8.

154. Mandakranta Bose (2004). The Ramayana Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 337–338. ISBN 978-0-19-803763-7.

155. Singh, Govind (2005). Dasamgranth. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. ISBN 978-81-215-1044-8.

156. Doris R. Jakobsh (2010). Sikhism and Women: History, Texts, and Experience. Oxford University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-19-806002-4.

157. Judge, Paramjit S.; Kaur, Manjit (2010). "The Politics of Sikh Identity: Understanding Religious Exclusion". Sociological Bulletin. 59 (3): 219. doi:10.1177/0038022920100303. ISSN 0038-0229. JSTOR 23620888. S2CID 152062554 – via Book.

158. Dodiya 2001, p. 139.

159. Ramdas Lamb 2012, pp. 31-32.

160. Monika Horstmann (1991). Rāmāyaṇa and Rāmāyaṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 72–73 with footnotes. ISBN 978-3-447-03116-5.

161. Hans Bakker (1990). The History of Sacred Places in India As Reflected in Traditional Literature: Papers on Pilgrimage in South Asia. BRILL. pp. 70–73. ISBN 90-04-09318-4.

162. Raj, Selva J.; Harman, William P. (1 January 2006). Dealing with Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6708-4.

163. James G. Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 98-108.

164. Larson, Gerald James (16 February 1995). India's Agony Over Religion: Confronting Diversity in Teacher Education. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2412-4.

165. James G. Lochtefeld 2002, p. 1.

166. Lorenzen, David N. (1999). "Who Invented Hinduism?". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 41 (4): 630–659. doi:10.1017/S0010417599003084. ISBN 9788190227261. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179424 – via Book.

167. Gupta 1991, p. 36.

168. Bhat, Rama (2006i). The Divine Anjaneya: Story of Hanuman. iUniverse. pp. 79. ISBN 978-0-595-41262-4.

169. J. L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL. pp. 471–472. ISBN 90-04-10260-4.

170. Meister, Michael W. (1988). "Prasada as Palace: Kutina Origins of the Nagara Temple". Artibus Asiae. 49 (3/4): 254–280 (Figure 21). doi:10.2307/3250039. JSTOR 3250039.

171. James C. Harle (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. pp. 148–149, 207–208. ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

172. Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul (1994). Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema. British Film Institute. ISBN 978-0-85170-455-5.

173. "People don't call me Arun Govil, they call me Ram, says 'Ramayan' star". The Financial Express. 29 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

174. February 4, Methil Renuka; February 4, 2002 ISSUE DATE; September 6, 2002UPDATED; Ist, 2012 11:25. "Now, B.R. Chopra to present silicon graphics-driven Ramayan on Zee TV". India Today. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

175. "These actors played the roles of Lord Ram on screen". News Track. 18 May 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

176. Singh, Shalu (1 August 2019). "Ram Siya Ke Luv Kush's grand launch in Ayodhya will leave you amazed. Watch video".

http://www.indiatvnews.com. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

Sources• Chapple, Christopher (1984). "Introduction". The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Translated by Venkatesananda, Swami. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-955-8. OCLC 11044869.

• Das, Krishna (15 February 2010), Chants of a Lifetime: Searching for a Heart of Gold, Hay House, Inc, ISBN 978-1-4019-2771-4

• "Navratri – Hindu festival". Encyclopedia Britannica. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

• Flood, Gavin (17 April 2008). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Wiley India Pvt. Limited. ISBN 978-81-265-1629-2.

• Hertel, Bradley R.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (1993). Living Banaras: Hindu Religion in Cultural Context. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1331-9.

• Miller, Kevin Christopher (2008). A Community of Sentiment: Indo-Fijian Music and Identity Discourse in Fiji and Its Diaspora. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-549-72404-9.

• Leslie, Julia (2003). Authority and meaning in Indian religions: Hinduism and the case of Vālmīki. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-3431-0.

• Morārībāpu (1987). Mangal Ramayan. Prachin Sanskriti Mandir.

• Poddar, Hanuman Prasad (2001). Balkand. 94 (in Awadhi and Hindi). Gorakhpur, India: Gita Press. ISBN 81-293-0406-6.

• Lutgendorf, Philip (1991). The Life of a Text: Performing the Rāmcaritmānas of Tulsidas. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06690-8.

• Naidu, S. Shankar Raju (1971). A Comparative Study of Kamba Ramayanam and Tulasi Ramayan. University of Madras.

• Platvoet, Jan. G.; Toorn, Karel Van Der (1995). Pluralism and Identity: Studies in Ritual Behaviour. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10373-2.

• Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-02522-5.

• Schomer, Karine; McLeod, W. H. (1 January 1987), The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0277-3

• Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1938-1

• Stasik, Danuta; Trynkowska, Anna (1 January 2006). Indie w Warszawie: tom upamiętniający 50-lecie powojennej historii indologii na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim (2003/2004). Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa. ISBN 978-83-7151-721-1.

• Varma, Ram (1 April 2010). Ramayana : Before He Was God. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-1616-1.

• Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph (ed.), Philosophies Of India, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

• Dodiya, Jaydipsinh (2001), Critical Perspectives on the Rāmāyaṇa, Sarup & Sons, p. 139, ISBN 978-81-7625-244-7

• Bassuk, Daniel E (1987). Incarnation in Hinduism and Christianity: The Myth of the God-Man. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-08642-9.

• Parrinder, Edward Geoffrey (1997). Avatar and Incarnation: The Divine in Human Form in the World's Religions. Oxford: Oneworld. ISBN 978-1-85168-130-3.

• Tripathy, Amish (2015). Scion of Ikshvaku. New Delhi, India: Westland Publications. ISBN 9-789-385-15214-6.

• Rinehart, Robin (2011). Debating the Dasam Granth. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-984247-6.

• Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

• Lamb, Ramdas (2012). Rapt in the Name: The Ramnamis, Ramnam, and Untouchable Religion in Central India. State University of New York Press. pp. 28–32. ISBN 978-0-7914-8856-0.

• Gupta, Shakti M. (1991). Festivals, Fairs, and Fasts of India. University of Indiana, United States: Clarion Books. ISBN 9-788-185-12023-2. OCLC 1108734495.

• Dalal, Roshan (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

• Hindery, Roderick (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

• Goldman, Robert P. (1996). The Ramayan of Valmiki. New Jersey, United States: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06662-2.

• Van Der Molen, Willem (2003). "Rama and Sita in Wonoboyo". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 159 (2/3): 389–403. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003748. ISSN 0006-2294. JSTOR 27868037.

Further reading• Jain Rāmāyaṇa of Hemchandra (English translation), book 7 of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra, 1931

• Griffith, Ramayana, Project Gutenberg

• Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

• Vyas, R.T. (ed.) (1992). Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. Vadodara: Oriental Institute. Text as Constituted in its Critical Edition,

• Valmiki. Ramayana. Gorakhpur, India: Gita Press.

• J. P. Mallory; Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

• Menon, Ramesh (2008) [2004]. The Ramayana: A Modern Retelling of the Great Indian Epic. ISBN 978-0-86547-660-8.

• Growse, F.S. (2017). The Ramayana of Tulsidas. Trieste Publishing Pty Limited. ISBN 9-780-649-46180-6.

• Blank, Jonah (2000). Arrow of the Blue-Skinned God: Retracing the Ramayana Through India. ISBN 0-8021-3733-4.

• Kambar. Kamba Ramayanam.

External links• Rama, World History Encyclopedia

• Rama at the Encyclopædia Britannica

• Media related to Rama (category) at Wikimedia Commons