by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/26/21

Tapa Shotor

(Hadda)

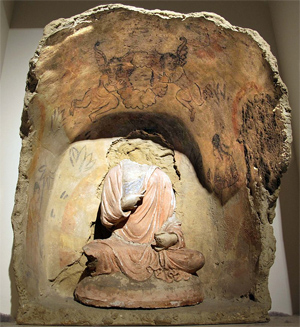

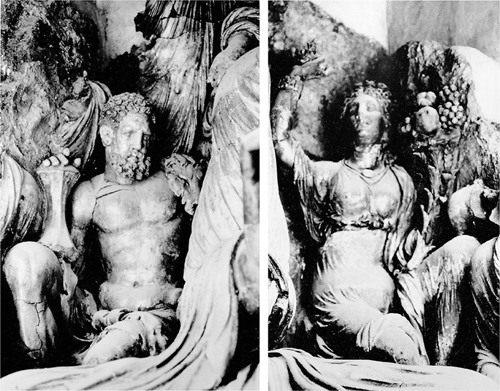

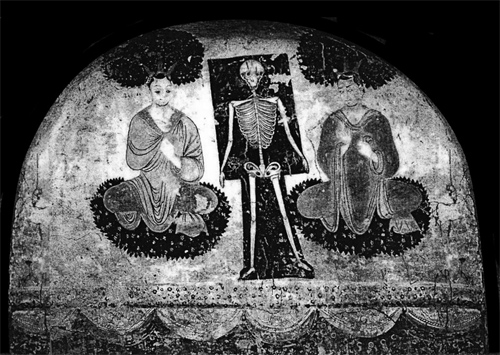

Tapa Shotor seated Buddha, with Classical figures of Herakles (left, as Vajrapani) and Tyche (right, as Hariti), in Niche V2, 2nd century CE. Photographed in 1981 by Louis Dupree, before its destructions by the Talibans in 1992.[1][2]

Tapa Shotor is located in Afghanistan

Type: Buddhist monastery

History

Founded: 1st century BCE

Abandoned: 9th century CE

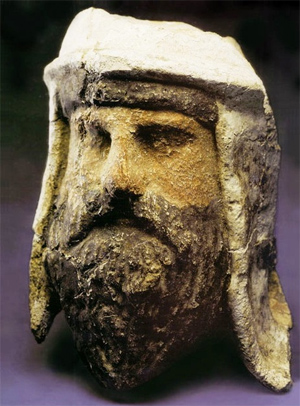

Head of a Buddha or Bodhisattva, facing (4th-5th century), probably Hadda, Tapa Shotor.[3][4]

Seated Buddha, Tapa Shotor (Niche V1).

Tapa Shotor, also Tape Shotor or Tapa-e-shotor ("Camel Hill"),[5] was a large Sarvastivadin Buddhist monastery near Hadda, Afghanistan, and is now an archaeological site.[6]

The Sarvāstivāda was one of the early Buddhist schools established around the reign of Asoka (third century BCE). It was particularly known as an Abhidharma tradition, with a unique set of seven Abhidharma works.

The Sarvāstivādins were one of the most influential Buddhist monastic groups, flourishing throughout North India (especially Kashmir) and Central Asia until the 7th century. The orthodox Kashmiri branch of the school composed the large and encyclopedic Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra around the time of the reign of Kanishka (c. 127–150 CE).The Abhidharma Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra is an ancient Buddhist text. It is thought to have been authored around 150 CE. It is an encyclopedic work on Abhidharma, scholastic Buddhist philosophy. Its composition led to the founding of a new school of thought, called Vaibhāṣika ('those [upholders] of the Vibhāṣa'), which was very influential in the history of Buddhist thought and practice.

-- Abhidharma Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra, by Wikipedia

Because of this, orthodox Sarvāstivādins who upheld the doctrines in the Mahāvibhāṣa were called Vaibhāṣikas.

The Sarvāstivādins are believed to have given rise to the Mūlasarvāstivāda sect as well as the Sautrāntika tradition, although the relationship between these groups has not yet been fully determined.

Sarvāstivāda is a Sanskrit term that can be glossed as: "the theory of all exists". The Sarvāstivāda argued that all dharmas exist in the past, present and future, the "three times". Vasubandhu's Abhidharmakośakārikā states, "He who affirms the existence of the dharmas of the three time periods [past, present and future] is held to be a Sarvāstivādin."

-- Sarvastivada, by Wikipedia

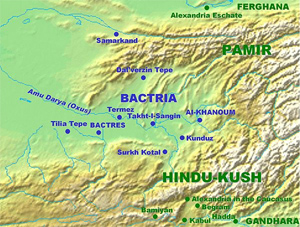

According to archaeologist Raymond Allchin, the site of Tapa Shotor suggests that the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara descended directly from the art of Hellenistic Bactria, as seen in Ai-Khanoum.[7]

Bactria, or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia. Bactria proper was north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and south of the Oxus river, covering the flat region that straddles modern-day Afghanistan. More broadly Bactria was the area north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Tian Shan, covering modern-day Tajikistan and Uzbekistan as well, with the Amu Darya flowing west through the centre.

Called "beautiful Bactria, crowned with flags" by the Avesta, the region is one of the sixteen perfect Iranian lands that the supreme deity Ahura Mazda had created. One of the early centres of Zoroastrianism and capital of the legendary Kayanian kings of Iran, Bactria is mentioned in the Behistun Inscription of Darius the Great as one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire; it was a special satrapy and was ruled by a crown prince or an intended heir. Bactria was the centre of Iranian resistance against the Macedonian invaders after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire in the 4th century BC, but eventually fell to Alexander the Great. After the death of the Macedonian conqueror, Bactria was annexed by his general, Seleucus I.

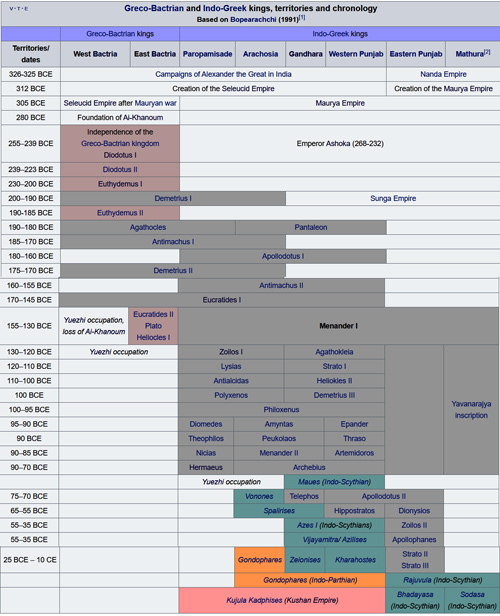

Nevertheless, the Seleucids lost the region after declaration of independence by the satrap of Bactria, Diodotus I; thus started history of the Greco-Bactrian and the later Indo-Greek Kingdoms. By the 2nd century BC, Bactria was conquered by the Iranian Parthian Empire, and in the early 1st century, the Kushan Empire was formed by the Yuezhi in the Bactrian territories. Shapur I, the second Sasanian King of Kings of Iran, conquered western parts of the Kushan Empire in the 3rd century, and the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom was formed. The Sasanians lost Bactria in the 4th century, however, it was reconquered in the 6th century. With the Muslim conquest of Iran in the 7th century, Islamization of Bactria began.

Bactria was centre of an Iranian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries, and New Persian as an independent literary language first emerged in this region. The Samanid Empire was formed in Eastern Iran by the descendants of Saman Khuda, a Persian from Bactria; thus started spread of Persian language in the region and decline of Bactrian language.

Bactrian, an Eastern Iranian language, was the common language of Bactria and surroundings areas in ancient and early medieval times.

-- Bactria, by Wikipedia

Ai-Khanoum (Aï Khānum, also Ay Khanum, lit. “Lady Moon” in Uzbek), possibly the historical Alexandria on the Oxus, possibly later named Eucratidia, Εὐκρατίδεια) was one of the primary cities of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom from circa 280 BCE, and of the Indo-Greek kings when they ruled both in Bactria and northwestern India, from the time of Demetrius I (200-190 BCE) to the time of Eucratides (170–145 BCE). Previous scholars have argued that Ai Khanoum was founded in the late 4th century BC, following the conquests of Alexander the Great. Recent analysis now strongly suggests that the city was founded c. 280 BC by the Seleucid emperor Antiochus I Soter. The city is located in Takhar Province, northern Afghanistan, at the confluence of the Panj River and the Kokcha River, both tributaries of the Amu Darya, historically known as the Oxus. It is on the lower of two major sets of routes (lowland and highland) which connect Western Asia to the Khyber Pass which gives road access to South Asia.

Ai-Khanoum was one of the focal points of Hellenism in the East for nearly two centuries until its annihilation by nomadic invaders around 145 BCE about the time of the death of Eucratides I.Eucratides I (reigned c. 171–145 BC), sometimes called Eucratides the Great, was one of the most important Greco-Bactrian kings, descendants of dignitaries of Alexander the Great. He uprooted the Euthydemid dynasty of Greco-Bactrian kings and replaced it with his own lineage. He fought against the Indo-Greek kings, the easternmost Hellenistic rulers in northwestern India, temporarily holding territory as far as the Indus, until he was finally defeated and pushed back to Bactria. Eucratides had a vast and prestigious coinage, suggesting a rule of considerable importance.

-- Eucratides I, by Wikipedia

On a hunting trip in the 1960s, the Afghan Khan Gholam Serwar Nasher discovered ancient artifacts of Ai Khanom and invited Princeton archaeologist Daniel Schlumberger with his team to examine Ai-Khanoum. It was soon found to be the historical Alexandria on the Oxus, also possibly later named Arukratiya or Eucratidia), one of the primary cities of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. Some of those artefects were displayed in Europe and USA museums in 2004. The site was subsequently excavated through archaeological work by a French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA) mission under Paul Bernard [fr] between 1964 and 1978, as well as Soviet scientists. The work had to be abandoned with the onset of the Soviet–Afghan War, during which the site was looted and used as a battleground, leaving very little of the original material. In 2013, the film-maker David Adams produced a six-part documentary mini-series about the ancient city entitled Alexander's Lost World.

Gold coin of Eucratides I (171–145 BC), one of the Hellenistic rulers of ancient Ai-Khanoum. This is the largest known gold coin minted in Antiquity (169,20 g; 58 mm).

Corinthian capital, found at Ai-Khanoum in the citadel by the troops of Commander Massoud, 2nd century BC.

Architectural antefixae with Hellenistic "Flame palmette" design, Ai-Khanoum.

Sun dial within two sculpted lion feet.

Winged antefix, a type only known from Ai-Khanoum.

Ai-Khanoum mosaic.

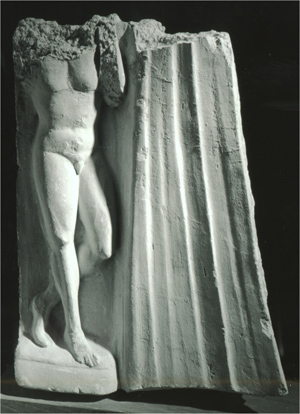

High-relief of a naked man in contrapposto, wearing a chlamys. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

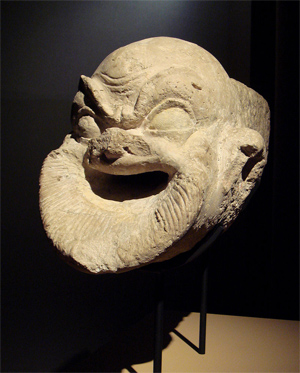

Stucco face found in the administrative palace. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC

Sculpture of an old man. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Close-up of the same statue.

Hellenistic gargoyle. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

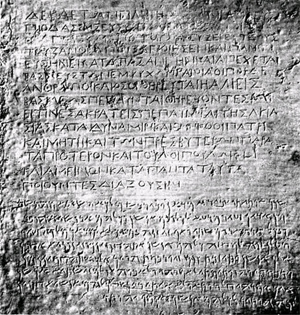

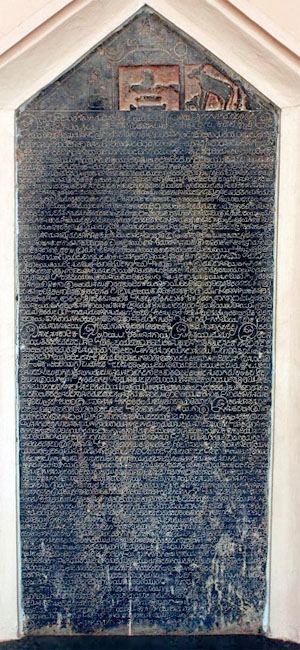

Stone block with the inscriptions of Kineas. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Inscription on one of the vases from the Ai-Khanoum treasury.

Plate depicting Cybele pulled by lions, a votive sacrifice and the Sun God. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Bronze Herakles statuette. Ai-Khanoum. 2nd century BC.

Bracelet with horned female busts. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Imprint from a mold found in Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

Ai-Khanoum ivory statuette. Temple of Indented Niches.

The Indian plate found in Ai-Khanoum, thought to represent the myth of Kunala (with reconstitution).

Coin of Greco-Bactrian king Agathocles with Hindu deities.

One of the Hellenistic-inspired "flame palmettes" and lotus designs, which may have been transmitted through Ai-Khanoum. Rampurva bull capital, India, circa 250 BCE.

Gold stater of the Seleucid king Antiochus I Soter minted at Ai-Khanoum, c. 275 BCE. Obverse: Diademed head of Antiochus. Reverse: Nude Apollo seated on omphalos, leaning on bow and holding two arrows. Greek legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΥ (of King Antiochos). Δ monogram of Ai-Khanoum in left field.

Indian Emperor Ashoka addressed the Greeks of the region circa 258 BC in the Kandahar Edict of Ashoka, a bilingual inscription in Greek and Aramaic. Kabul Museum.

-- Ai-Khanoum, by Wikipedia

The site of Tapa Shotor was destroyed by arson and looted in 1992.[1]

Stylistic analysis

In view of the style of the objects found at Tapa Shotor, particularly the clay figures, Allchin suggests that either Bactrian artists came and worked for Buddhist monasteries, or that local artists had become "fully conversant" in Hellenistic art.[7] This opinion was confirmed by the archaeologist who excavated the site Tarzi: "in the light of the latest discoveries there is no longer any doubt about the prolongation of the Graeco-Bactrian artistic past".[8] According to Tarzi, Tapa Shotor, with clay sculptures dated to the 2nd century CE, represents the "missing link" between the Hellenistic art of Bactria, and the later stucco sculptures found at Hadda, usually dated to the 3rd-4th century CE.[1] The sculptures of Tapa Shortor are also contemporary with many of the early Buddhist sculptures found in Gandhara.[1]

Traditionally, the influx of artists conversant in Hellenistic art has been attributed to the migration of the Greek populations from the Greco-Bactrian cities of Ai-Khanoum and Takht-i Sangin.[9]

The ancient town of Takht-i Sangin is located near the confluence of the Vakhsh and Panj rivers, the source of the Amu Darya [Oxus], in southern Tajikistan.

The Greco-Bactrian temple site of Takht-i Sangin is believed by many to be the source of the Oxus Treasure that now resides in the Victoria and Albert Museum and British Museum. Part of greater Transoxiana and built in the 3rd Century BC, the site consists of a well-fortified citadel containing the so-called "Temple of Oxus".

Painted clay and alabaster head, Takht-i Sangin, Tajikistan, 3rd-2nd century BCE. Possibly a Zoroastrian priest.

Hellenistic satyr Marsyas from Takhti Sangin, with dedication in Greek to the god of the Oxus, by "Atrosokes", a Bactrian name. 200-150 BCE. Tajikistan National Museum.

Hellenistic statuette from Takhti Sangin, 2nd century BCE, Tajikistan National Museum.

Hellenistic statuette from Takht-i Sangin, 2nd-3rd century BCE, Tajikistan National Museum.

Takht-i Sangin ivory sculpture.

Takht-i Sangin portrait of an old man, 3rd century BCE.

Fragment of the head of an elephant, 3rd-4th century BCE.

-- Takht-i Sangin, by Wikipedia

Tarzi further suggested that Greek populations were established in the plains of Jalalabad, which included Hadda, around the Hellenistic city of Dionysopolis, and that they were responsible for the Buddhist creations of Tapa Shotor in the 2nd century CE.[9]

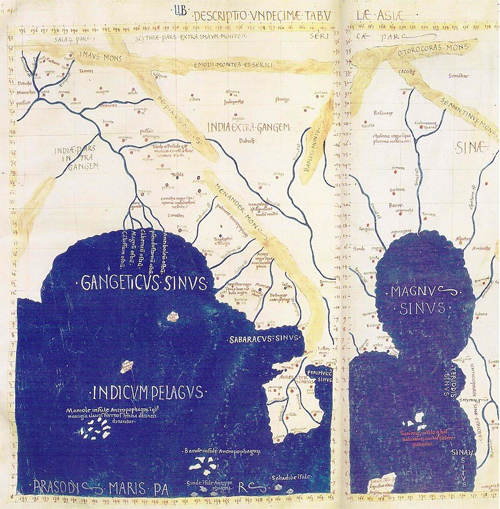

Nagara (Ancient Greek: Νάγαρα), also known as Dionysopolis (Διονυσόπολις), was an ancient city in the northwest part of India intra Gangem (India within the Ganges), distinguished in Ptolemy by the title ἡ καὶ Διονυσόπολις 'also Dionysopolis'. It also appears in sources as Nagarahara, and was situated between the Kabul River and the Indus, in present-day Afghanistan.

From the second name which Ptolemy has preserved, we are led to believe that this is the same place as Nysa (Νύσα) or Nyssa (Νύσσα), which was spared from plunder and destruction by Alexander the Great because the inhabitants asserted that it had been founded by Dionysus, when he conquered the area and he named the city Nysa and the land Nysaea (Νυσαία) after his nurse and also he named the mountain near the city, Meron (Μηρὸν) (i.e. thigh), because he grew in the thigh of Zeus.

When Alexander arrived at the city, together with his Companion cavalry went to the mountain and they made ivy garlands and crowned themselves with them, as they were, singing hymns in honor of Dionysus. Alexander also offered sacrifices to Dionysus, and feasted in company with his companions. On the other hand, according to Philostratus although Alexander wanted to go up the mountain he decided not to do it because he was afraid that when his men will see the vines which were on the mountain they would feel home sick or they will recover their taste for wine after they had become accustomed to water only, so he decided to make his vow and sacrifice to Dionysus at the foot of the mountain.

The site of Nagara is usually associated with a site now called Nagara Ghundi, about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) west of Jalalabad, south of the junction of the Surkhäb and Kabul rivers, where ancient ruins have been found.

Archaeologist Zemaryalai Tarzi has suggested that, following the fall of the Greco-Bactrian cities of Ai-Khanoum and Takht-i Sangin, Greek populations were established in the plains of Jalalabad, which included Hadda, around the Hellenistic city of Dionysopolis, and that they were responsible for the Buddhist creations of Tapa Shotor in the 2nd century CE.

-- Nagara (ancient city), by Wikipedia

Haḍḍa is a Greco-Buddhist archeological site located in the ancient region of Gandhara, ten kilometers south of the city of Jalalabad, in the Nangarhar Province of eastern Afghanistan.

Hadda is said to have been almost entirely destroyed in the fighting during the civil war in Afghanistan.

Some 23,000 Greco-Buddhist sculptures, both clay and plaster, were excavated in Hadda during the 1930s and the 1970s. The findings combine elements of Buddhism and Hellenism in an almost perfect Hellenistic style.

Although the style of the artifacts is typical of the late Hellenistic 2nd or 1st century BCE, the Hadda sculptures are usually dated (although with some uncertainty), to the 1st century CE or later (i.e. one or two centuries afterward). This discrepancy might be explained by a preservation of late Hellenistic styles for a few centuries in this part of the world. However it is possible that the artifacts actually were produced in the late Hellenistic period.

Given the antiquity of these sculptures and a technical refinement indicative of artists fully conversant with all the aspects of Greek sculpture, it has been suggested that Greek communities were directly involved in these realizations, and that "the area might be the cradle of incipient Buddhist sculpture in Indo-Greek style".

The style of many of the works at Hadda is highly Hellenistic, and can be compared to sculptures found at the Temple of Apollo in Bassae, Greece.

The toponym Hadda has its origins in Sanskrit haḍḍa n. m., "a bone", or, an unrecorded *haḍḍaka, adj., "(place) of bones". The former - if not a fossilized form - would have given rise to a Haḍḍ in the subsequent vernaculars of northern India (and in the Old Indic loans in modern Pashto). The latter would have given rise to the form Haḍḍa naturally and would well reflect the belief that Hadda housed a bone-relic of Buddha. The term haḍḍa is found as a loan in Pashto haḍḍ, n., id. and may reflect the linguistic influence of the original pre-Islamic population of the area.

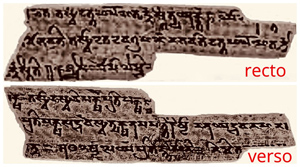

It is believed the oldest surviving Buddhist manuscripts-indeed the oldest surviving Indian manuscripts of any kind -- were recovered around Hadda. Probably dating from around the 1st century CE, they were written on bark in Gandhari using the Kharoṣṭhī script, and were unearthed in a clay pot bearing an inscription in the same language and script. They are part of the long-lost canon of the Sarvastivadin Sect that dominated Gandhara and was instrumental in Buddhism's spread into central and east Asia via the Silk Road. The manuscripts are now in the possession of the British Library.

-- Hadda, Afghanistan, by Wikipedia

Chronology

According to archaeologist Zemaryalai Tarzi, the first, pre-monastic, period of Tapa Shotor, corresponds to the reign of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (35-12 BCE).[10]

Azes II ([x]; both from Saka *Aza, meaning "leader".), may have been the last Indo-Scythian king, speculated to have reigned circa 35–12 BCE, in the northern Indian subcontinent (modern day Pakistan). His existence has been questioned; if he did not exist, artefacts attributed to his reign, such as coins, are likely to be those of Azes I.[3]

After the death of Azes II, the rule of the Indo-Scythians in northwestern India and Pakistan finally crumbled with the conquest of the Kushans, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi who had lived in Bactria for more than a century, and who were then expanding into India to create a Kushan Empire.The Yuezhi were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat by the Xiongnu in 176 BC, the Yuezhi split into two groups migrating in different directions: the Greater Yuezhi and Lesser Yuezhi.

The Greater Yuezhi initially migrated northwest into the Ili Valley (on the modern borders of China and Kazakhstan), where they reportedly displaced elements of the Sakas. They were driven from the Ili Valley by the Wusun and migrated southward to Sogdia and later settled in Bactria. The Greater Yuezhi have consequently often been identified with peoples mentioned in classical European sources as having overrun the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, like the Tókharioi (Greek Τοχάριοι; Sanskrit Tukhāra) and Asii (or Asioi). During the 1st century BC, one of the five major Greater Yuezhi tribes in Bactria, the Kushanas, began to subsume the other tribes and neighbouring peoples. The subsequent Kushan Empire, at its peak in the 3rd century AD, stretched from Turfan in the Tarim Basin in the north to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain of India in the south. The Kushanas played an important role in the development of trade on the Silk Road and the introduction of Buddhism to China.

The Lesser Yuezhi migrated southward to the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Some are reported to have settled among the Qiang people in Qinghai, and to have been involved in the Liangzhou Rebellion (184–221 AD) against the Chinese Han dynasty. Another group of Yuezhi is said to have founded the city state of Cumuḍa (now known as Kumul and Hami) in the eastern Tarim. A fourth group of Lesser Yuezhi may have become part of the Jie people of Shanxi, who established the Later Zhao state of the 4th century AD (although this remains controversial).

Yuezhi, by Wikipedia

Soon after, the Parthians invaded from the west. Their leader Gondophares temporarily displaced the Kushans and founded the Indo-Parthian Kingdom that was to last until the middle of the 1st century CE.Parthia is a historical region located in north-eastern Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC, and formed part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire following the 4th-century-BC conquests of Alexander the Great. The region later served as the political and cultural base of the Eastern-Iranian Parni people and Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire (247 BC – 224 AD). The Sasanian Empire, the last state of pre-Islamic Iran, also held the region and maintained the Seven Parthian clans as part of their feudal aristocracy.

-- Parthia, by Wikipedia

The Kushans ultimately regained northwestern India circa 75 CE, where they were to prosper for several centuries.

Azes II in armour, riding a horse, on one of his silver tetradrachms, minted in Gandhara

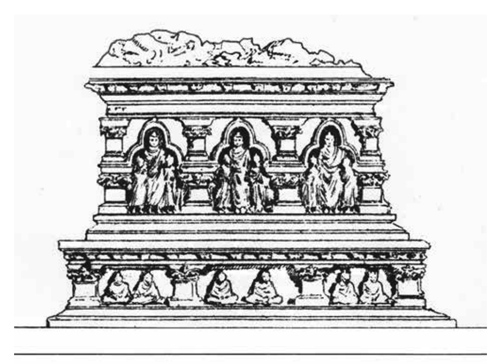

The Bimaran casket, representing the Buddha surrounded by Brahman (left) and Indra (right) was found inside a stupa with coins of Azes II inside. British Museum.

Coin of Azes II with Buddhist triratna symbol.

Coin of Azes II, with a clear depiction of his military outfit, with coat of mail and reflex bow in the saddle.

Azes II in armour, riding a horse, on one of his silver tetradrachms, minted in Gandhara. British Museum. Personal photograph.

-- Azes II, by Wikipedia

The first Buddhist period dates to the reign of Kushan king Huvishka (155-187 CE). This period correspond to the creation of vihara, and niches 1, 2 and 3 in particular.[10] The period after Vasudeva I to the last Kushans (225-350 CE) saw the creation of niche XIII. After the Kushans, a period of the site corresponds to the Kidarites (4th-5th century CE).[10] The site remained inactive for about 250 years, from around 500 to 750 CE. A last period of activity followed, only marked by restorations, before the destruction of the site by fire in the 9th century CE. The period have been structured as follows:[10]

• Tapa Shotor I: Indo-Scythian king Azes II (35-12 BCE)

• Tapa Shotor II: Kushan king Huvishka (155-187 CE). Vihara, and niches V1, V2 and V3

• Tapa Shotor III: (187-191 CE)

• Tapa Shotor IV: Vasudeva I (191-225 CE)

• Tapa Shotor V: Last Kushans (225-350 CE)

• Tapa Shotor VI: Kidarites (350-450 CE)

• Tapa Shotor VII: 5th century

• Tapa Shotor VIII: 6th century. Corresponds to the 1st period of Tape Tope Kalan.

• hiatus (6th-8th century)

• Tapa Shotor IX: mid 8th century-9th century. Destruction by fire

Excavation

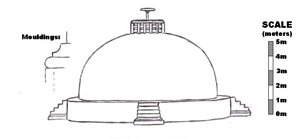

The monastery was excavated by an all-Afghan archaeological team. It yieded numerous sculptures in an archaeologically intact environment, providing great insights on the art of the region. A stupa was excavated in the main courtyard.[11]

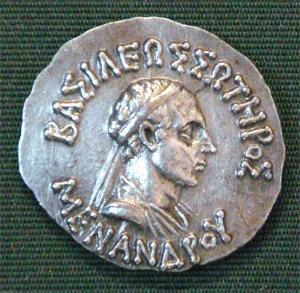

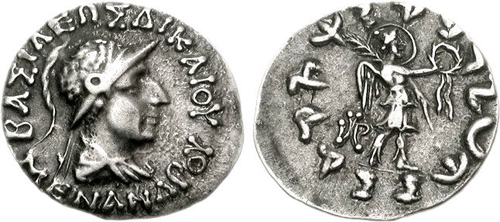

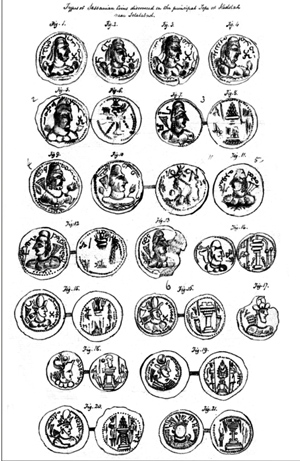

A coin of the Indo-Greek king Menander was found in the ruins, but the abundance of finds of Kushan coinage suggest a main 4th century CE date for the site.[11]

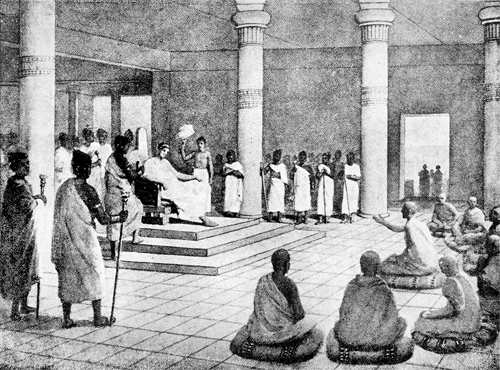

Menander I Soter ("Menander I the Saviour"; known in Indian Pali sources as Milinda) was an Indo-Greek King of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (165/155 –130 BC) who administered a large empire in the Northwestern regions of the Indian Subcontinent from his capital at Sagala. Menander is noted for having become a patron of Buddhism.

Menander was initially a king of Bactria. After conquering the Punjab he established an empire in the Indian Subcontinent stretching from the Kabul River valley in the west to the Ravi River in the east, and from the Swat River valley in the north to Arachosia (the Helmand Province). Ancient Indian writers indicate that he launched expeditions southward into Rajasthan and as far east down the Ganges River Valley as Pataliputra (Patna), and the Greek geographer Strabo wrote that he "conquered more tribes than Alexander the Great."

Large numbers of Menander’s coins have been unearthed, attesting to both the flourishing commerce and longevity of his realm. Menander was also a patron of Buddhism, and his conversations with the Buddhist sage Nagasena are recorded in the important Buddhist work, the Milinda Panha ("The Questions of King Milinda"; panha meaning "question" in Pali). After his death in 130 BC, he was succeeded by his wife Agathokleia, the possible daughter of Agatokles, who ruled as regent for his son Strato I. Buddhist tradition relates that he handed over his kingdom to his son and retired from the world, but Plutarch relates that he died in camp while on a military campaign, and that his remains were divided equally between the cities to be enshrined in monuments, probably stupas, across his realm...

According to an ancient Sri Lankan source, the Mahavamsa, Greek monks seem to have been active proselytizers of Buddhism during the time of Menander: the Yona (Greek) Mahadhammarakkhita (Sanskrit: Mahadharmaraksita) is said to have come from "Alasandra" (thought to be Alexandria of the Caucasus, the city founded by Alexander the Great, near today’s Kabul) with 30,000 monks for the foundation ceremony of the Maha Thupa ("Great stupa") at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, during the 2nd century BC:From Alasanda the city of the Yonas came the thera ("elder") Yona Mahadhammarakkhita with thirty thousand bhikkhus.

— Mahavamsa, XXIX

A coin of Menander I was found in the second oldest stratum (GSt 2) of the Butkara stupa suggesting a period of additional constructions during the reign of Menander. It is thought that Menander was the builder of the second oldest layer of the Butkara stupa, following its initial construction during the Maurya empire.

These elements tend to indicate the importance of Buddhism within Greek communities in northwestern India, and the prominent role Greek Buddhist monks played in them, probably under the sponsorship of Menander...

Plutarch reports that Menander died in camp while on campaign, thereby differing with the version of the Milindapanha. Plutarch gives Menander as an example of benevolent rule, contrasting him with disliked tyrants such as Dionysius, and goes on to explain that his subject towns fought over the honour of his burial, ultimately sharing his ashes among them and placing them in "monuments" (possibly stupas), in a manner reminiscent of the funerals of the Buddha....

Despite his many successes, Menander's last years may have been fraught with another civil war, this time against Zoilos I who reigned in Gandhara. This is indicated by the fact that Menander probably overstruck a coin of Zoilos....

After the reign of Menander I, Strato I and several subsequent Indo-Greek rulers, such as Amyntas, Nicias, Peukolaos, Hermaeus, and Hippostratos, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a symbolic gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of the Buddha's teaching. At the same time, right after the death of Menander, several Indo-Greek rulers also started to adopt on their coins the Pali title of "Dharmikasa", meaning "follower of the Dharma" (the title of the great Indian Buddhist king Ashoka was Dharmaraja "King of the Dharma"). This usage was adopted by Strato I, Zoilos I, Heliokles II, Theophilos, Peukolaos and Archebios.

Altogether, the conversion of Menander to Buddhism suggested by the Milinda Panha seems to have triggered the use of Buddhist symbolism in one form or another on the coinage of close to half of the kings who succeeded him. Especially, all the kings after Menander who are recorded to have ruled in Gandhara (apart from the little-known Demetrius III) display Buddhist symbolism in one form or another.

Both because of his conversion and because of his unequaled territorial expansion, Menander may have contributed to the expansion of Buddhism in Central Asia. Although the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and Northern Asia is usually associated with the Kushans, a century or two later, there is a possibility that it may have been introduced in those areas from Gandhara "even earlier, during the time of Demetrius and Menander" (Puri, "Buddhism in Central Asia").

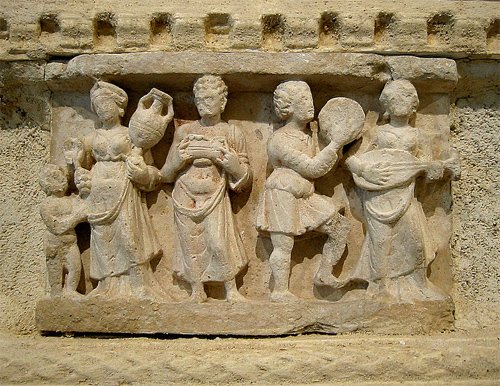

A frieze in Sanchi executed during or soon after the reign of Menander depicts Buddhist devotees in Greek attire. The men are depicted with short curly hair, often held together with a headband of the type commonly seen on Greek coins. The clothing too is Greek, complete with tunics, capes and sandals. The musical instruments are also quite characteristic, such as the double flute called aulos. Also visible are Carnyx-like horns. They are all celebrating at the entrance of the stupa. These men would probably be nearby Indo-Greeks from northwest India visiting the Stupa.

Vitarka Mudra gestures on Indo-Greek coinage. Top: Divinities Tyche and Zeus. Bottom: Depiction of Indo-Greek kings Nicias and Menander II.

-- Menander I, by Wikipedia

Tapa Shortor had some beautiful statuary in Hellenistic style, particularly one seated Buddha attended by Herakles-Vajrapani and a Tyche-like woman holding a cornucopia, now destroyed (Niche V2).[12][13] Another has an attendant reminding the portrait of Alexander the Great.[14][15] Boardman suggested that the sculpture in the area might be an "incipient Buddhist sculpture in Indo-Greek style".[16]

Figures of Herakles-Vajrapani with thunderbolt, and Tyche-Hariti with cornucopia, flanking a Buddha at Tapa Shotor, Hadda, 2nd century CE. This is unique photograph as the sculpture was destroyed in 1992 by the Talibans.

Many of the statues are three-dimensional representations in-the-round, a rare instance in the area of Hadda, which related the style of Tapa Shotor to the Hellenistic art of Bactria, and to the Buddhist caves of Xinjiang such as the Mogao Caves, probably directly inspired by these.[17]

Various niches display scenes of the Buddha surrounded by attendants (especially niches V1, V2, V3). Niche XIII, or "Aquatic niche", also demonstrates sculpture in the round, and depicts Naga Kalika predicting the success of the Bodhisattva towards attaining enlightenment. The niche is dated to the period 250-350 CE, and is probably synchronous with the clay sculptures of Temple II in Penjikent.[18][19] These sculptures are made of clay, while later sculptures molded in stucco can also be seen at the site.[20]

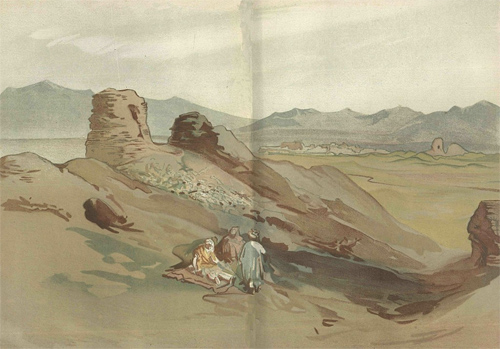

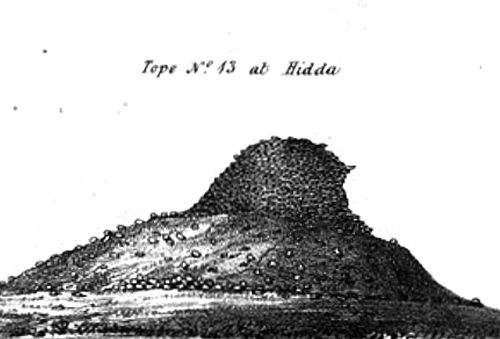

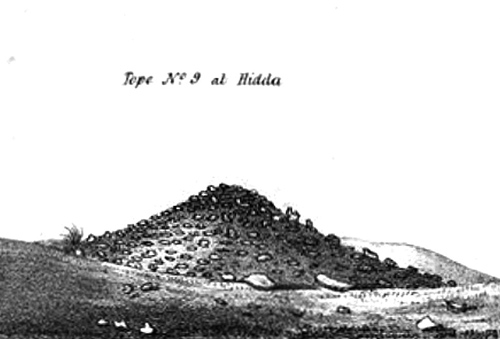

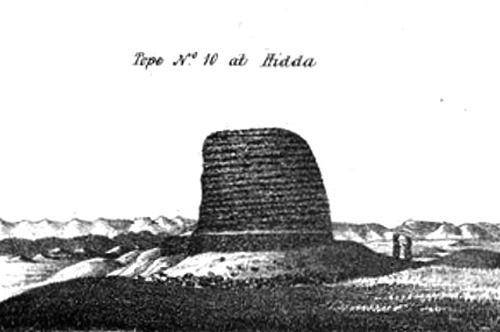

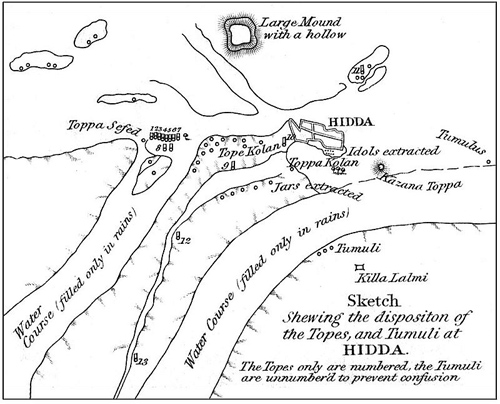

Map of Hadda, by Charles Masson in 1841. Tapa Shotor was the "Large Mound with a hollow".[21]

Painting of the lunette of an underground meditation chamber.[22] Tapa Shotor, period VI (350-450 CE).[23]

Attendants to the Buddha, Tapa Shotor (Niche V1)

Buddha attendants, Tapa Shotor (Niche V1)

Seated Buddha with "Vajrapani-Alexander" attendant. Tapa Shotor (Niche V3).[24]

Head of "Vajrapani-Alexander", Tapa (Niche V3).[25]

Buddha attendants, Tapa Shotor

Small decorated stupas in Tapa Shotor.[26]

Site of Tapa Shotor, with a protective roof.[26]

External links

• Description and plan of Tapa Shotor (French)

• The famous Buddha with Herakles-Vajrapani and Tyche can be seen in Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 150.

References

1. Tarzi, Zémaryalai. "Le site ruiné de Hadda": 62 ff.

2. "Tepe Shotor Tableau. Hadda, Nangarhar Province. ACKU Images System". ackuimages.photoshelter.com.

3. Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007). The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-224-4.

4. Boardman, George. The Greeks in Asia. pp. Greeks and their arts in India.

5. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 143.

6. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 158.

7. "Following discoveries at Ai-Khanum, excavations at Tapa Shotor, Hadda, produced evidence to indicate that Gandharan art descended directly from Hellenised Bactrian art. It is quite clear from the clay figure finds in particular , that either Bactrian artist from the north were placed at the service of Buddhism, or local artists, fully conversant with the style and traditions of Hellenistic art , were the creators of these art objects" in Allchin, Frank Raymond (1997). Gandharan Art in Context: East-west Exchanges at the Crossroads of Asia. Published for the Ancient India and Iran Trust, Cambridge by Regency Publications. p. 19. ISBN 9788186030486.

8. Tarzi, Zemaryalai (2005). "Sculpture in the Round and Very High Relief in the Clay Statuary of Hadda: The Case of the So-called Fish Porch (Niche XIII)" (PDF). East and West. 55 (1/4): 392. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29757655.

9. Tarzi, Zémaryalai. "Le site ruiné de Hadda": 63.

10. Vanleene, Alexandra. "Tapa-e Shotor". Hadda Archeo Data Base. ArcheoDB, 2021.

11. Kuwayama, Shoshin (1988). "Tapa Shotor and Lalma: Aspects of stupa courts at Hadda" (PDF). Annali dell'Università degli studi di Napoli "L'Orientale".

12. Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007). The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-58839-224-4.

13. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 148-149.

14. Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-691-03680-9.

15. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 150.

16. Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-691-03680-9.

17. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 152-153.

18. Tarzi, Zemaryalai (2005). "Sculpture in the Round and Very High Relief in the Clay Statuary of Hadda: The Case of the So-called Fish Porch (Niche XIII)". East and West. 55 (1/4): 383–394. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29757655.

19. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 152-153.

20. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 152-153.

21. Errington, Elizabeth. "Masson archive Vol. 2 (1).pdf": 36.

22. GREENE, ERIC M. (2013). "Death in a Cave: Meditation, Deathbed Ritual, and Skeletal Imagery at Tape Shotor". Artibus Asiae. 73 (2): 265–294. ISSN 0004-3648. JSTOR 24240815.

23. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 154.

24. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 150.

25. Vanleene, Alexandra. "The Geography of Gandhara Art" (PDF): 150.

26. Tarzi, Zémaryalai. "Le site ruiné de Hadda".