The Rise and Fall of the Parliament of Religions at Greenacre

by Robert P. Richardson

The Open Court

A Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Science of Religion, the Religion of Science, and the Extension of the Religious Parliament Idea

Copyright by Open Court Publishing Company 1931

Volume XLVI (No. 3), Number 898

March, 1931

Joseph Jefferson, Sarah J. Farmer, Swami Abhedananda (The Camp at Green Acre)

ON THE THIRD day of July, 1894, there gathered in the little town of Eliot, Maine, a group of men and women resolved to form a center where might be continued each summer the work so auspiciously begun at [url=x]the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893,[/url] when thinkers of the most opposite schools had freely expressed their views on religion, ethics, philosophy and sociology, and had amicably listened to the other side of each question. In the call for the Chicago Congresses their purposes had been stated as to "review the progress already achieved in the world, state the living problems now awaiting solution, and suggest the means of farther progress." Quoting this and reaffirming it as the purpose of the summer meetings at Eliot, the program of the first season promised "a series of lectures and courses on topics which shall quicken and energize the spiritual, mental and moral natures, and give the surest and serenest physical rest." It had been determined "to form a center at the Greenacre Inn where thinking men and women, reaching out to help their fellows through means tried and untried, might find an audience recognizing not alone revealed truth, but truth in the process of revelation. It was believed that for those of different faiths, different nationalities, different training, the points of contact might be found, the great underlying principles — the oneness of truth, the brotherhood of man; that to the individual this spot might mean the opening door to freedom, the tearing down of walls of prejudice and superstition."

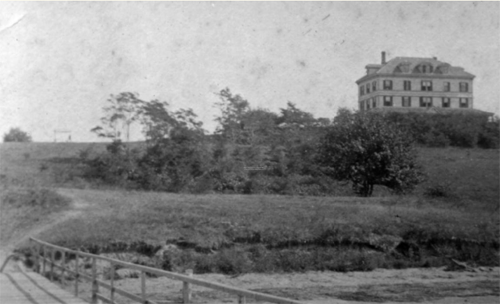

This view from the Piscataqua River shows the Sarah Farmer Inn atop the hill on the Green Acre property. At the time this photograph was taken, the Inn was called the Eliot Hotel and acted as a resort for summer guests. It was owned by Martin Tobey, George Hammond, Dr. John Willis, Francis Keefe and Sarah Farmer. John Greenleaf Whittier called the Hotel 'Green Acre' and Sarah Farmer, one of the Hotel owners, renamed the inn to be Green Acre Inn.

Eventually the Inn and surrounding properties became a center for spiritual thought, where speakers would come from all over the world to share religious and spiritual subjects with the guests and Eliot residents.

-- Green Acre Property, by Maine Memory Network

The place selected for this work had been well chosen. At a beautiful spot on a tidal estuary (the so-called Piscataqua "river") six miles from the sea, there had been built in 1890 the Greenacre Inn. Even in the beginning it was designed to accommodate people of the more cultured classes and persons with literary and artistic tastes. John Greenleaf Whittier had found there a pleasant refuge from the heats of the New England hinterland, declaring it to be ''the pleasantest place I was ever in." Whittier had brought with him the authoress "Grace Greenwood" (Mrs. Lippincott) and his cousin, Mrs. Gertrude Cartland who, clad in her simple but dignified garb of a Quakeress, had charmed all present by her impressive recitals from the mystical writings of Madame Guyon. Looking from the windows of the Inn the guests had sometimes seen Miss Olea Bull gracefully dancing the Norwegian "Spring Dance." Sometimes too she played, and one of the enthusiastic beholders wrote: "You will hear grand music from her. She is the only daughter of Ole Bull who played the violin as no other person ever did. I do not think you ever saw such willowy grace as there is in that child's every movement. She is wonderfully made."

The Greenacre Inn was thus well known to the intellectuals of New England who gave an enthusiastic reception to the announcement of the new Greenacre idea, and flocked to Eliot to take part in the meetings. Mrs. Ole Bull gave the opening address of the first season, and Miss Sarah J. Farmer acted as secretary of the conferences. Among the speakers of that summer are to be noted the names of Edward Everett Hale, [url=x]Swami Vivekananda[/url], Lewis G. Janes, Ralph Waldo Trine, B. O. Flower of The Arena, Neal Dow and a host of others, fifty or sixty speakers in all being listed. The subjects discussed included Universal Religion, Prophets and Prophecy, [url=x]The Theosophical Movement[/url], The Religion of India, Is Spiritualism Worth While if True? The Relation of Religion to Art, Evolution and Life, The Possibilities of Woman, Motherhood, Mental Freedom, The Education of the Future, [url=x]Immanuel Kant[/url], Individualism and Socialism, and Economic Natural Law.

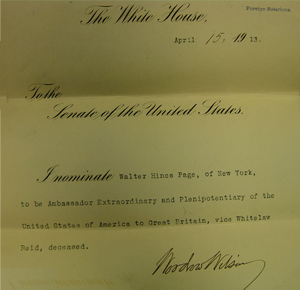

Among the celebrities visiting Greenacre in the next few years and contributing to the programs were William Lloyd Garrison, Walter H. Page, Clarence Darrow, Lilian Whiting, Alice B. Stockham. B. Fay Mills, Orison Swett Marden, Elbert Hubbard, George D. Herron, Bolton Hall, Percival Chubb, W. M. Salter, Alfred W. Martin, Judge W. C. Robinson (Dean of the Catholic University of America), Prof. Joseph Le Conte, J. H. Hyslop, Lester A. Ward, John Fiske, C. H. A. Bjerregaard of the New York Astor Library, W. T. Harris (U. S. Commissioner of Education), Carroll D. Wright (U. S. Commissioner of Labor) and [url=x]Annie Besant[/url]. Theodore T. Wright, Secretary of the Palestine Exploration Fund, lectured on Recent Explorations confirming and interpreting the Bible. John Burroughs gave a Talk on Nature. J. T. Trowbridge, Edwin Markham and Sam E. Foss gave readings from their works, W. D. Howells came and read his Traveller from Altruria, and the famous actor Joseph Jefferson (who became a charter member of the Green Acre Fellowship when this was formed in 1902) regaled the Greenacreites every summer under the pines with informal talks on the drama. Some practical talks on art were given by painters and sculptors not unknown to fame (e.g. Arthur W. Dow of Ipswich and F. Edwin Elwell of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art) and musical instruction was available for those who cared to take it. A number of musicians and singers of the first rank likewise found their way to Eliot and freely gave their aid in enlivening the Greenacre proceedings with song and music. Geraldine Farrar was at Greenacre as a girl, and even then a great future was predicted for the youthful singer. The story is told that on one occasion, when she consented to entertain Greenacre with her singing, she uttered a very long drawn out note, and just as she was about to terminate it the whistle of a distant locomotive prolonged the sound for some live minutes. Whereupon the waggish Joseph Jefferson said in a loud aside that brought down the house: "My! What a voice that girl has!"[1]

Noteworthy was the Evolution Conference of 1895 organized by Lewis G. Janes. The proceedings were opened with an address by Dr. E. D. Cope of the University of Pennsylvania on Present Problems of Organic Evolution, and in the second meeting there was read a paper on Social Evolution and Social Duty contributed by Herbert Spencer to this Greenacre conference, though originally prepared in view of being read at the Chicago Congress of Religions of 1893. Two sessions of the conference were held daily. Papers were read on such subjects as Social Ideals tested by Evolutionary Principles, Natural Selection and Crime, and The Evolution of the God-Idea, the conference being finally closed with two addresses by John Fiske.

The first week of the Summer Congress at Greenacre, on the Piscataqua, was devoted to the Conference of Evolutionists which held its first meeting on July 6th, under the direction of Dr. Lewis G. Janes, President of the Brooklyn Ethical Association. The program was as follows:Saturday, July 6th - Evolution Conference under the direction of Dr. Lewis G. Janes, President of the Ethical Association; S.P.M., Professor Edward D. Cope, Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania, 'The President Problems of Organic Evolution'; S.P.M., paper from Herbert Spencer, of London, Eng., 'Social Evolution and Social Duty,' to be followed by a symposium and brief addresses.

Monday, July 8 - 3 P.M., Mr. Henry Wood, of Boston, Mass., 'Industrial Evolution'; S.P.M., Mr. Benjamin F. Underwood, Editor Philosophical Journal, Chicago, Ill., 'How Evolution Reconciles Opposing Views of Ethics and Philosophy'; letters and brief addresses.

Tuesday, July 9 - 3 P.M., Professor Edward S. Morse, of the Peabody Institute, Salem, Mass., 'Natural Section and Crime'; S.P.M., Dr. Martin L. Holbrook, editor Journal of Hygiene, New York, 'Evolution's Hopeful Promise for Human Health.'

Wednesday, July 10 - 3 P.M., Rev. Edward P. Powell, of Clinton, N.Y., 'Evolution of Individuality'; S.P.M., Miss Mary Proctor, of New York, 'Other Worlds Than Ours,' with stereopticon Illustrations.

Thursday, July 11 - 3 P.M., Rev. James T. Bixby, Ph.D. of Yonkers, N.Y., 'Evolution of the God-Idea'; S.P.M., Dr. Lewis G. Janes, President Brooklyn Ethical Association, 'Evolution of Morals.'

The Congress will be continued during the months of July and August, a lecture being delivered on each afternoon and occasionally one also in the evening. The last lecture will be delivered on August 31st, by Hon. Carroll D. Wright.

-- Science, A Weekly Journal Devoted to the Advancement of Science, Volume II - July to December, 1895, edited by John Michels (Journalist)

This conference led in the following season to the organization of the School of Comparative Religion which, under the supervision of Dr. Janes, functioned each summer at Greenacre from 1893 on, the meetings being usually held in the open air under the pines. Thoroughly in sympathy with the Religious Parliament idea, Dr. Janes was exceptionally well fitted to put on a scientific and systematic basis the work in this line which had hitherto been carried on at Greenacre in a somewhat desultory way. One of the early contributors to The Open Court, he was prominent in the Ethical Culture movement and in the Free Religious Association, and had been President of the Brooklyn Ethical Association for eleven years. Remarkable for the breadth of his intellectual and religious sympathies, he knew how to insure a cordial welcome to the representative of every shade of opinion, and to make each speaker feel that the atmosphere of his audience was receptive and sympathetic. Dr. Janes brought to Greenacre, among others, the Vedantist Swamis Saradananda and Abhedananda, the Buddhist [url=x]Anagarika H. Dharmapala[/url], the Jain Virchand R. Gandhi, Rabbi Joseph Krauskopf, and, above all, Prof. Nathaniel Schmidt of Cornell University, who for many years was the chief standby of the scholarly and scientific element of the Greenacreites. [url=x]Dr. Carus[/url] came to Greenacre for a short time in August 1897 and lectured on Religion in Science and Philosophy. The report of the conferences notes that he "was greeted with great cordiality and found here many friends who read and appreciate his writings." He also "had a few conferences informally in which he discussed the problem of the Ego and the philosophy of Lao-tze." Dr. Carus was hailed at Greenacre as "the representative of sober criticism and exact science" and although "he did not countenance the various aberrations of occultism" in vogue among the more erratic and emotional of the Greenacreites, it is recorded that his "criticism is not offensive; he confines himself to a sober exposition of his own views, and when he is requested to speak his word on the various mystic tendencies he makes an occasional fling at others, but he does it with humor and is never sarcastic."

The Greenacre movement grew apace, and soon the Inn proved inadequate to lodge the attendants at the meetings who overflowed into the near-by farm houses. An array of sixty or seventy tents — Sunrise Camp— grew up on the banks of the Piscataqua, and people of prominence did not disdain their primitive accommodations. "The soil is very porous" wrote E. P. Powell in The Christian Register, "and absorbs water very speedily. You will lie in the tents, laughing at storms and never catching cold. One reason, I imagine, is that we have something else to think of, for colds have a certain dependence on spiritual and intellectual conditions. In the Inn you will see the Whittier Table; and if you are a lecturer, you will be permitted to sit in his chair." Near the Inn was erected a modest auditorium tent, holding three hundred people, but this proved too small, and it was soon necessary to provide another with double the capacity. Usually the program for the day began at 9 A. M. with unsectarian devotional exercises in the large tent, following which, in fair weather, the Greenacreites trooped off to the beautiful Lysekloster Pines (so named from the Norwegian home of Ole Bull) where they seated themselves on the soft carpet of pine needles and, drinking in the fragrance of the piney forest, listened to the morning lectures. Only on rainy days was a tent used for these morning meetings, but in the afternoon lectures were commonly given in the large tent, its sides being left wide open so that one could gaze across the river at the New Hampshire countryside and see in the distance the foothills of the White [Mountains. The tent served in the evenings, sometimes for lectures, sometimes for musical or dramatic entertainments. The latter purposes how-ever were better served by the "Eirenion" (Abode of Peace), a large wooden structure erected not far from the Inn in 1897. In 1896 the gratuitous services of an enthusiastic printer were enlisted, and there was published at Eliot, in the interests of the conferences, a weekly newspaper. The Greenacre Voice, this effort persevering for several seasons.

Side by side with the conferences on religion other activities went on. It is narrated that on one record-breaking day sixteen different meetings were held, the first being a Vedantist devotional exercise at 6 A. M. which was an addition to, not a substitute for the usual service at 9, and that a certain lady, trying to take in all that Greenacre had to offer on that occasion, lamented because she had been able to attend only nine! There were educational conferences, more evolution conferences, nature conferences and sociological conferences. Classes for teaching the New Thought practices were held by Horatio Dresser and his assistant. Miss Ellen M. Dyer, when weather permitted in the open air, these and the classes of Miss Mary H. Burnham's School of Music being the only functions at which payment of a fee was required of those taking part. "We all wander around as fancy leads us" said a lady "and if we see a group of people anywhere, just drop in. And the freedom and informality is a large part of the charm of Greenacre life." Each year a Peace Conference was held under the Greenacre flag which floated on a tall pole near the river, a white silken banner on which was inscribed in green letters the single word "Peace." In later years when factional quarrels were rife among the Greenacreites, some cynic suggested that this be described as "The flag we fight under," and there is told the story that once, when two ladies at a meeting in the Eirenion were so angry with each other as to all but come to blows, the custodian of the standard, Mr. Douglass, hastened to lower the Peace Flag as a sign that peace no longer reigned at Greenacre.

Once a year was celebrated Emerson Day in honor of the great Transcendentalist. The meetings were held in the Pines and presided over by Frank B. Sanborn, the last resident member of the Concord School of Philosophy and the friend and companion of Emerson and Thoreau. A favorite spot for this celebration was in front of a gigantic boulder known as The Mystic Rock (also called the Druid Stone) which sometimes served as a platform for the speakers of the day. One who was accustomed to be present described the occasion as follows: "We sit under the trees and listen to the tender intimate touches from Emerson's life and experiences. Then Charles Malloy gives a series of Emerson readings, with lines and interlines of interpretation, the wealth of a lifetime of study." There were group walks through the woods, made more profitable by talks on the birds and other forms of wild life which could be seen at times, for Eliot, though legally a town, only two short hours' ride from Boston and but three miles from the city of Portsmouth, is really a slice of the country, there being no large aggregation of houses but rather a scattering of homesteads, some quite small but others covering many acres, interspersed with tracts of woodland several miles deep. In these woods could be found the camps of one or two Greenacreites who preferred the seclusion they afforded, notably Dharmapala, the Buddhist monk, and Ralph Waldo Trine, familiarly known at as "Judge Trine" on account of the judicial serenity of his countenance. It was in a willow-woven hut by the side of the Mystic Rock that Mr. Trine wrote his famous work: In Tune with the Infinite, and it is said that more than once when engaged in its composition he was interrupted by a curious cow who poked her head in the open doorway. Sometimes the early morning "Kneippers" would wind up their exercises with a call on Mr. Trine who, when not preoccupied with literary work, always gave them a hearty welcome and served them coffee, reputed to be the best in Greenacre.

It would be a great mistake to suppose that the majority of Greenacreites had any intention of keeping their noses to the grindstone and acquiring new knowledge by a severe course of mental discipline. The magnet that drew summer visitors to Eliot was the life that could be led there, the possibility seen, by people with tastes above that of the common herd, of mingling with their own kind. One could go to a lecture and, if not inclined to listen too attentively, gaze dreamily at the blue sky just showing through the green branches or look out on the broad expanse of the Piscataqua and become oblivious to everything else. After a lecture the Greenacreites would stroll through the woods and along the country lanes, and no introduction was necessary for the commencement of a conversation. This conversation might not go very deeply into the questions discussed at the conferences, but would be very much above the level of the conversation of the card party or the talk at the conventional dinner table. Social distinctions and the possession of a fortune or the lack of one played no part in the fellowship of the Greenacreites; the only thing that mattered was behaving decently and being interesting to talk with. Men and women of wealth were by no means unknown in the colony, but coming, as they almost invariably did, from a long line of more or less wealthy forbears, they never thought of flaunting their prosperity in the eyes of the less fortunate Greenacreites, but donned their old clothes and enjoyed the simple life like the rest. The nouveau riche were conspicuous by their absence, and women who at home had their full staffs of servants could here be seen clad in calico, picking blackberries along the country lanes to take back to their landladies as part of the evening repast. Greenacre was thus as different from the ordinary summer resort as day is from night, and even people who were not inclined to do much high thinking found to their taste the simple living, coupled with refinement and culture that was in vogue in Eliot.

We must not exaggerate the influence of the lecturers and conferences on the Greenacreites, and there is no doubt that the intellectual atmosphere of the place was far more potent than any formal course of instruction could be in spreading the spirit of the Parliament of Religions. No religious or philosophical or sociological sect was dominant, and a Greenacreite had necessarily to throw oft' the sectarian attitude and listen with respectful attention to doctrines which he could not possibly bring himself to accept. The customs and scruples of the religionists from foreign lands were courteously respected even when they seemed very far fetched to Occidental minds. To do this was sometimes far from easy. It is recorded that one lady invited the Jain, Gandhi, to a dinner which she had taken care to make vegetarian, hoping thus to suit his tastes. But "he would eat nothing save ice cream, and if he had known there were eggs in it he would not have eaten that. He taboos all vegetables grown under ground."

A Good Greenacreite would not even hesitate to take part in the ceremonies of alien faiths. One night the Buddhist monk, Dharmapala, who had astonished the natives of Eliot by going about clad in bright orange colored robes and equally gaudy yellow shoes, organized a pilgrimage to the Pines in which all Greenacre took part, to celebrate the festival of the Full ^loon. The Greenacreites gathered at nightfall, arrayed in white, each person carrying a bunch of flowers and a lighted candle-lantern. Headed by Dharmapala, who chanted in sing-song tones as he walked, the picturesque procession wended its way to the Pines where the posies were used to build an altar of flowers under a magnificent tree which had been named The Bodhi Pine in memory of the Tree of Wisdom under which tradition says the Gautama Buddha sat. By its side Dharmapala seated himself on the ground, cross-legged, in Buddha posture, while the Greenacreites, kept en rapport by a circlet of yellow cord which each held by one hand, grouped themselves around him endeavoring to adjust themselves to the same uncomfortable position. For several hours each gazed at his own candle on which he concentrated all his thoughts, and some of the pilgrims who had taken the matter so seriously as to follow Dharmapala's injunction to prepare for the occasion by a fast beginning at daybreak, and had let nothing but a few drops of water pass their lips all that day, were rewarded by imagining they saw the ghostly forms which they had been told might be made manifest to them. With a fine Catholicism the same men and women who participated in this Buddhist ceremony would lend their aid to the worship of the setting sun by the Parsee, Jehangier D. Cola, and stand by his side in respectful silence as he made obeisance to the glowing orb. Equal zest was shown in going through the ceremonies of the Midsummer Nature Worship, inaugurated by Mr. Bjerregaard. Such proceedings, though they made Greenacre more interesting to people of broad mentality, were quite incomprehensible to the good Congregationalists of Eliot, who began to show some aversion to the "pagan" summer visitors. The feelings of the towns' folk were also aroused by the practices of some Greenacreites who took mud baths, and walked about on the shores of the Piscataqua in garbs that at the beaches of to-day would be deemed ultra-modest bathing costumes. "Kneipping"' was another trial to the natives. Those were the days in which Father Kneipp gained a brief celebrity by advocating running barefooted in the dewy grass as the royal road to health, and the Eliot people often saw the summer visitors engaging in these unseemly antics as they were deemed. A contemporary account of Greenacre throws a vivid light on the attitude of Eliot people in 1897. "'This world is an amazin' queer place,' was confided to me by one of the farmers' wives" wrote Laura S. "McAdoo," 'and Greenacre is the queerest part of it. Why have you seen those droves of people that run through the fields in a kind of dogtrot early in the morning, They call that Kneipping. and they go to see the sun rise too" I'm sure I don't think that sunrise is such a sight, and I've seen it almost every day of my life. And they actually go worshipping the sun, and say heathen prayers when it goes down. I don't know what the world's coming to. when we have these foreigners over here dressed up in outlandish clothes preaching all sorts of strange doctrines, after we've been trying to convert them for hundreds of years. It's ridiculous" Why my little girl saw this new eastern man that wears purple and orange and I almost had to laugh at the young one. She said: Oh mamma" Here comes another devil" It must be Mr. Dharmapala's brother. Just look at that now' she continued, going to the window as the expounder of Parseeism passed by attired in the national costume of his race. 'What's he after now? I believe they dress so just to look queer.'" Doubtless the little Eliot girl who called the foreigners in queer costumes "devils" had shuddered at the tales she heard in church' of the heathen Chinese who call Americans and Europeans "foreign devils," but we may be quite sure that neither she nor her mother had any inkling of how near culturally they were to the ignorant Chinese they so despised.

In the boom year of 1897 everything seemed rosy at Greenacre. Visitors flocked from all parts of the country to attend the conferences and take part in the life they had heard was so enjoyable. The lectures at times drew audiences of over eight hundred people, who, not finding seats inside the tent where the meetings were being held, stood around outside listening to the proceedings. Funds flowed in freely and were used (rather recklessly, as it turned out) in putting up the Eirenion, erecting three cottages to shelter the more distinguished summer visitors (the Whittier, Hildegard and Duon cottages) and enlarging and improving the kitchen and dining room of the Inn — in lieu of paying the long over-due rent on the latter. Thinking that a prosperous future was assured to Greenacre, several of the town's people built annexes to their homesteads to house future flocks of summer visitors, and during the next two years had no difficulty in filling them. To the superficial view all was well with Greenacre. But the institution was booked for a decline, as it had no satisfactory financial basis. Admission to all the lectures and conferences was absolutely free, and although it was suggested that those who attended should make voluntary contributions according to their means, the response was never sufficient for the needs of Greenacre. The only other resource was the money received at the Inn and at Sunrise Camp, that paid by the summer visitors for board in other places in no way benefitting Greenacre. And as the capacity of the Inn was so limited — it having only thirty-five rooms — and as the prices charged at it and in the tents were exceedingly moderate, the profits in any event could not be large. Moreover the possible profits were reduced by the fact that the lecturers at Greenacre received as compensation, besides their traveling expenses, free board at the Inn for a more or less lengthy stay, and the excessive number of lecturers and other non-paying guests made the situation very difficult. Notwithstanding various substantial gifts that were made to Greenacre the financial situation became so bad that in 1900 the work was all but dropped. The School of Comparative Religion was suspended, and the only lecturers made use of that season were persons who had come to Eliot at their own expense and were paying the full charge for board at the Inn or elsewhere. The facts however were kept in the shade by calling this a "Sabbatical Year," the leading spirit in the Greenacre work, ]Miss Sarah Farmer, passing the summer abroad as the guest of a friend, Miss Alaria Wilson, a fervent devotee of the Bahai religion: the first Greenacreites to succumb to the fascinations of that offshoot of Mohammedanism.

In the spring of 1901 Miss Farmer gave no inkling of any intention of continuing the Greenacre work, and at the solicitation of those desirous of seeing it go on, including the lessee of the Greenacre Inn and the various persons in Eliot who eked out their budget by taking in summer boarders. Dr. Janes decided to take up anew the work of the School of Comparative Religion and conduct it on a sounder financial basis, charging a small fee to those who should attend the lectures. In previous years voluntary contributions had been made by those taking the course and others, amounting in 1899, the peak year of the school when 214 persons enrolled, to $375. It had been customary to divide the sum remaining, after paying incidental expenses, among the workers of the school, but in 1899, after defraying the travelling expenses of the workers, the balance was turned over to Greenacre, the lecturers at the school willingly foregoing that year even the meagre cash compensation that had been usual. Dr. Janes, under the new plan, set a fixed registration fee of two dollars, with an additional charge, if lecturers were attended for more than one week, of five dollars for the course, or fifty cents for each single lecture. On account of the summer visitors that it was known the reopened school would bring to Eliot, the Innkeeper and the boarding house proprietors expressed their willingness to be responsible for the board of Dr. Janes' modest staff of lecturers.

On hearing of the new departure Miss Farmer rose up in arms and resuming her activity managed to gather together enough money to carry on a Greenacre program during the season of 1901. She sponsored a course of lectures similar to those of Dr. Janes, conflicting with these as to time, and there were thus two rival Schools of Comparative Religion at Eliot that season. The only ostensible reasons Miss Farmer had for opposing Dr. Janes instead of co-operating with him were his "abandonment of the voluntary principle" (i. e. his requiring a minimum fee to be paid by all attendants at his course) and his "attempting to cut one of the branches of Greenacre from its parent stem" (in other words his daring to continue the work of the School of Comparative Religion without asking her permission and refusing to submit to her authority as paramount). Sarah Farmer, in fact, claimed proprietary rights in the Greenacre movement, and assumed that if she chose to abandon it no one else had any right to carry it forward. Now it is true that to her had first come the idea of using the Greenacre Inn as a center for lectures and conferences, and to her persuasive powers were due the consent of the proprietors of the Inn to try this experiment: an experiment conducted on so grandiose a scale as to spell disaster to the owners of the Inn who had not received a single cent in rental during the five years (1894-1898) in which Miss Farmer had control of the property. To her initiative also were due most of the arrangements for the lectures and conferences, and besides contributing money of her own to the work, she had induced a number of well-wishers to the cause to contribute liberally towards its support. She ought however have recognized that her fellow laborers had likewise given time and money freely, and that they could not be expected to stand idle and see the movement fall to the ground merely because Aliss Farmer seemed unwilling or unable to go on with it. Many of the original Greenacreites, heavy contributors to the movement, took the part of Dr. Janes, notably Mrs. Bull, whose contribution of one thousand dollars had made possible the purchase of the Lysekloster Pines.[2] Mrs. Ole Bull, nee Sara Chapman Thorp, had been prominent in the movement from the very beginning. She was accustomed to move in the literary and artistic world, as w'as her family, her brother, Air. Joseph G. Thorp, Jr., having married a daughter of Longfellow. She had undoubtedly rendered great service in getting Greenacre in touch with people of prominence besides aiding with her counsels the erratic and culturally somewhat undeveloped Miss Farmer. It was Mrs. Bull who, in the winter season at Boston, had sponsored and largely financed a work very similar to that of the Greenacre summer school: the "Cambridge Conferences" directed by Dr. Janes and held in the house of Mrs. Bull who intended these conferences to be "in some degree a memorial to her mother, Mrs. Thorp, a woman of unusual benevolence and energy." Mrs. Bull strove in vain to heal the breach between Miss Farmer and Dr. Janes. The latter carried his plans for a summer school at Eliot in 1901 to successful fruition, but died in September of the same year, and Miss Farmer, perhaps somewhat chastened by this temporary rivalry, continued to reign at Greenacre.

In the years subsequent to 1900 Miss Farmer managed to secure enough "free will offerings" to keep up the work, though Greenacre always lived from hand to mouth, the close of each season showing a deficit which had to be made up by fresh solicitation for funds. Andrew Carnegie, at one time, offered a yearly subvention of $250 with the stipulation that $750 more must be guaranteed, and a reasonably business-like accounting be given of subscriptions received and money paid out, but these conditions were never satisfactorily met. Mrs. Bull however continued to contribute liberally to Greenacre, and other heavy contributors were Edwin Ginn, the Boston publisher, Mr. and Mrs. George D. Ayers of "Ayers' Cherry Pectoral" fame, Frank Jones, the wealthy Portsmouth brewer, and Mrs. Phoebe Hearst, the mother of the originator of yellow journalism. It was the last who provided the funds, for purchase of the Inn property in 1902, title to which was put in the name of James C. Hooe of Washington, a life interest in the property being assured to Miss Farmer who henceforth had free use of the Inn subject to payment of taxes and insurance. Mrs. Hearst had shown some interest in the Bahai movement, but in arranging to have the Inn subserve the work at Greenacre, made no effort to change the latter into a sectarian institution. The like holds of Helen E. Cole who, on her death in 1906 left a substantial bequest to the Green Acre Fellowship. As to the other contributors mentioned above, none of them showed any particular sympathy for the Bahai cause.

During her trip abroad Miss Farmer had visited Acre, where she met Abdul Baha, the leader of the religious body known as Bahais, and on her return she announced herself a convert to this Persian cult. Whether or not her new-found faith had any influence in making Miss Farmer oppose the work of Dr. Janes is a moot question. But there can hardly be any doubt that she had found him too liberal, or, perhaps it would be better to say, too scientific and scholarly. Her own naive idea of the study of comparative religions is shown by the statement that appeared in her program of 1903: "The Monsalvat School for the Comparative Study of Religion will be held in Lysekloster Pines at 10:30 A. M. except Saturday. Fillmore Moore, M. D., the Director will lecture on dietetics (!!!!) and will be assisted by ....." — the subjects discussed by the lecturers whose names followed including psychology, education, literature and biography" It is doubtful whether the Religious Parliament idea, in its full implication, ever had any real appeal for Miss Farmer, who is on record as having declared that the Chicago Congresses had played no part in making her conceive the project of summer courses and conferences at Greenacre. She, in fact, sometimes spoke of the purpose of Greenacre as the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth. And thus is not precisely the same as the promotion of the Religious Parliament movement, for every religious bigot will avow his adhesion to the former while refusing to accept the latter as a step in that direction. It is probable indeed that the reference to the Chicago Congresses in the original Greenacre program was by no means due to Sarah Farmer but was the thought of some more liberal promoter of the project — very possibly Mrs. Bull. It is worthy of note that the memory of this gifted lady is still kept green in Eliot, the cottage she once owned and occupied adjacent to the Inn being invariably called The Ole Bull Cottage, though since her day it has had many other occupants.

Though we deprive Sarah Jane Farmer of the halo with which the imagination of her more ardent admirers invested her, there can be no doubt that taken all in all she was a very remarkable woman. Through her father, Moses Farmer, an electrical inventor of some note, she was descended from Lord William Russell executed in London for treason under Charles II, being thus a distant relative of the present-day Bertrand Russell. The greater part of her life drifted by uneventfully, and it was only after the death of her father in 1893 who bequeathed her a modest inheritance of a few thousand dollars and the homestead of "Bittersweet" that she blossomed forth as the founder of Greenacre. She founded this at an age, forty-seven, when most women are contented to He placidly on the shelf, and it became famous almost over-night, being soon renowned among the intellectuals, from coast to coast, from Canada to California.[3] Her personality was most charming, and the smile with which she silenced her critics and bent the will of others to her own is still talked of. She "smiled as the angels must smile" wrote Miss Churchill. Those who called upon her were regaled with the smile — "a cup of tea and a welcome" being her motto as hostess — and none went away feeling dissatisfied. She had a marvellous faculty for obtaining gratuitous labor for the cause of Greenacre, her smile and words of praise being adjudged sufficient recompense. She was equally proficient in persuading people to open their purses to contribute to a worth}- cause, and boasted that she had "once raised $2,000 for a struggling little French church in twenty minutes time, and the audience was not a wealthy one."

Sarah Farmer, while not precisely beautiful, was a tall woman of graceful presence and slender proportions. "Her face with its habitual expression of introspective interest was the face of a dreamer." An enthusiastic admirer, Kate Pitkin, writing in 1899 in The New Orleans Times-Democrat, tells us that "her light slender hair is drawn back from her fine brow into an unobtrusive knot on her neck. Her complexion is suggestive of exquisite cleanliness and her eyes of inward purity and upward devotion." In the morning she usually appeared in a soft gray woolen gown which followed the curves of her body in unbroken lines. About her throat she wore a white lace scarf crossed on the bosom with an Egyptian pin. "Her afternoon gowns are of crepe, of dull silks or satiny cashmere, gray always, of the pale silver shade, and whenever she appears with a bonnet, which is rare at Greenacre, it is small and close, and covered with a silvery nun's veiling which hangs to her waist behind."

Dr. Carus wrote:[4] "I knew Miss Farmer personally and stayed at Greenacre once. It was an interesting atmosphere, and it was her spirit that gave all the attractions to it. It was really a home of many cranks, and I will not deny that her judgment was not very well grounded or sufficient to keeping cranks out, but it was interesting to outsiders even to listen to a crank. As you say, everybody was welcome and a brotherly spirit obtained everywhere . . . Her sympathetic character . . . was friendly to all kinds of thought and welcomed every sincere faith." "I met Miss Farmer for the first time at the house of Judge Waterman in Chicago. Mrs. Waterman had died recently and Miss Farmer met on her visit to Chicago Mr. Bonney as well as myself and she expressed to Mr. Bonney her desire to produce a continued institution which should serve the spirit of the Religions Parliament, and it was in this sense that she invited me to deliver some lectures out in Greenacre. I have the impression that Miss Farmer was a lovely spirit of deep religious convictions, but not very definite or clear in her aims. She was willing to accept from Mr. Bonney what he proposed to her, and while I was in Greenacre she tried her best to serve the spirit of the Religious Parliament in universal brotherhood as well as in service in spreading light and scientific insight on religious questions."

A certain proportion of the Greenacreites followed Miss Farmer into the Bahai fold (some of them developing a fanaticism which she never exhibited) but this was very far from being the case with all even of those who willingly accepted her as leader in the work at Eliot. Nor did Miss Farmer ever make any attempt to have this Persian religion preached at Greenacre to the exclusion of other religious doctrines. In the beginning she contented herself with giving the Bahai teachings a prominent place on her program and writing Greenacre in two words "Green Acre" that it might be reminiscent of the Acre in Syria. She announced in her program of 1903 that "the Green Acre Conferences were established in 1894 on the banks of the Piscataqua in Maine, with the express purpose of bringing together all who were looking earnestly towards the new Day which seemed to be breaking over the entire world and were ready to serve and be served. The motive was to find the Truth, the Reality, underlying all religious forms in order to promote the unity necessary for the ushering in of the coming Day of God. Believing that the Revelation of the Baha Ullah of Persia is the announcement of this great Day — the beginning of the Golden Age foretold by all seers, sung by poets — and finding that it provides a platform on which the Jew, the Christian (both Catholic and Protestant), the Mohammedan, as well as the members of all other great religious bodies can stand together in love and harmony, each holding to the form which best nourishes his individual life, an opportunity will be given to all who desire to study its Message." Evidently what is here alleged to have been the original purpose of the Greenacre Conferences is very different from that set forth in the program of 1894 cited above. Miss Farmer however took care to add: "As in previous years there will be no sectarianism at Green Acre. The effort will be to inspire and strengthen each to follow his highest light in order that by degrees he may know Truth for himself from the invisible guiding of the Eternal Spirit." In the 1904 program it was stated that "For ten years Green Acre has stood with open doors calling to the people of all nations to come together in peace and unity to prepare for the approaching glad New Day. Now that it has been shown that what was held in vision through faith has become fact through the great Revelation of the Baha Ullah, the time seems to be at hand to lay special emphasis upon the command: Be ye doers of the word and not hearers only, and upon the joys and blessings of servitude."' And in that year Myron H. Phelps, accepted from his ultra-eulogistic Life and Teachings of Abbas Effendi as a staunch Bahai, replaced Dr. Moore (who was not of that category) as Director of the School of Comparative Religion. In 1905 the program stated that "For four years Green Acre has proclaimed from the printed page of its program that, at least in the mind of its founder, what is known to the world as Bahaism is not a new 'ism' to stand side by side with and rival former religious systems, but that it is the completion and fulfillment of all that has preceded it. Whatever of truth is found in the great religious systems of the world, is found in Bahaism, elucidated and explained so fully in detail that the 'abundant life' revealed centuries ago now becomes a joyful reality. Each year, however, this message seems less and less understood by those into whose life the realization of this fullness had previously come, and it seems that placing this system on the same forum with the other in the Monsalvat School is in danger of bringing confusion to the mind instead of the desired peace. For this reason she who has carried in her heart for twelve years or more the thought of unity and concord among the sons of God, has decided to return to the original forum under the Persian Pine, that this great Revelation may be studied and interpreted in a place apart by itself, thus relieving other Green Acre workers from embarrassment and the necessity of explanation."

It is clear that what this amounted to was that the proponents of the new cult had in the beginning supposed that when set forth side by side with the teachings of other faiths everyone who gave ear would at once recognize the superiority of the Bahai revelation to all others.' But they had now come to realize their mistake and to perceive that with a fair field and no favor the Persian cult would not be accepted as all-sufficient by more than a small percentage of those who heard it advocated. The prevalent attitude, in fact, was that of listening sympathetically to the preachings of all faiths and taking from each whatever the individual listener thought valuable: it was the tolerant pagan attitude of the old Greenacre and not the intolerant bigotry of Mohammedanism. Although the favored position of Bahaism was further accentuated by having the Bahai advocates continue to preach at the School of Comparative Religion (in addition to carrying on sectarian meetings under the Persian Pine) this measure failed of its purpose: the Greenacreites did not abandon the School of Comparative Religion held under the Prophets' Pine and flock to the Persian Pine to hear the one true and genuine revelation. And to-day while the stately Bodhi Pine and Swami Pine and Prophets' Pine still proudly lift their branches towards heaven and continue to flourish in their original healthy vigor, the Persian Pine, which the sacred array of nine encircling stones has failed to protect, is dying, rotting away at the very heart: an interesting bit of symbolism for those who believe in portents.