by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/6/20

Cora's first tiny health camp was run in 1931 which should see it and those which followed reflecting the ideas described by McDonald for the period 1900-1944, which were a focus on the child as 'social capital' rather than 'psychological being' or as independent citizen. What we do find in Cora's camps was the belief in children as social capital which saw the psychological component of the child as being an important part of that potential social capital, as well as an emphasis on the rights of the individual child to his or her own psychological well-being, where the citizenship rights of the child as child, were placed to the fore....

Feminism, specifically what Marilyn Lake has described in terms of the 'exemplary citizen' -- an idea wrapped up in theosophical beliefs, among others -- saw citizenship as a constructed ideal for men and women rather than as being just a democratic right....'citizenship' was a hugely important idea for both Cora and the Sunlight League....

Although Cora was not actively involved with work done by other women's/feminist organisations, and while she was not so much concerned with working actively towards legal equality nor economic equality for women, nor with the concerns of the working class woman as such, Cora was representative of the type of post-suffrage feminist identified by Marilyn Lake as being the exemplary citizen.38 [Organisations such as the National Council of Women, the Women's Division of Federated Farmers or the Women's Institute -- although these organisations were in contact with the Sunlight League throughout the years it was in operation, and delegates from the other organisations and the Sunlight League attended each other's meetings and co-operated in organising the Sunlight League Health Camps (providing food and labour); the 'exemplary citizen' was an ideal wrapped up in theosophical beliefs, among others. Lake, p. 7, p. 51.] Melanie Nolan's Breadwinning: New Zealand Women and the State, has discussed post-suffrage feminist activity in New Zealand in terms of economic independence and citizenship for women, but rather than portraying Cora as a woman concerned with 'economic' or 'political' citizenship, during the period under discussion I would describe her as a woman concerned with 'social' or what may even be best described as 'cultural' citizenship for women....Within this discourse of femininity and citizenship, women were going to play an important role in the future development of the nation, not only as mothers, but as agents in their own right, who were free to contribute to the social and cultural wealth of New Zealand as they were best fitted.

This ideal of female citizenship centred on the concerns of the white, middle-class women of New Zealand, but it was no less feminist because of its elitist motivations.39 [The Enlightenment ideal of the citizen was racist and ethnographic, but ostensibly 'universal, free, and equal'. A. Cuthoys, 'Citizenship, Race, and Gender: Changing Debates over the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Rights of Women' in Daley and Nolan eds. Suffrage and Beyond, pp.89-106, p. 90.] The focus lay on this segment of society because it was they who were reading the liberal and progressive books, and they who had the time to spend at, and access to, the facilities required for the building of the 'good citizen'. Cora and women like her, dealt with the ideal of the good citizen in a way which saw it as an open category as far as race and class were concerned ideologically, but in reality these were the groups set outside of the work being done in the cause of 'betterment for society' by way of raising 'good citizens'. The 'good citizen' was a culturally constructed category which failed to take cultural differences into consideration, just as ideas at this time regarding the assimilation of the Maori into the Pakeha way of life failed to recognize that the 'modern' society was not a signifier of natural evolution, but in fact a signifier of European culture. Similarly while 'class' was not explicitly a barrier in the way to achieving 'good citizenship', because 'class' became in many ways conflated with 'health' -- both being socially constructed categories -- the health camps run by the Sunlight League failed to accept children from 'bad' homes which were considered indicative of bad genes and poor health when these were more than likely the signs of the home-life of the working class. This means that Cora was in a way, out of touch with the concerns of a large portion of the community, but in saying this, it is important to point out that the ideal of the good (white middle-class) woman citizen was an ideal of a person who worked towards the greater good for all -- which meant also championing the rights of the worker and the racialised other. The important thing for Cora at this early stage in her engagement with feminist activities in the form of the running of health camps for girls which centred on 'encouraging good citizenship', was to teach the leaders of tomorrow how to be good and fair people, and as such, society would benefit in due course -- girl children weren't just going to pass on their knowledge of health to their off-spring, they were also going to pass on their ideals of citizenship which were learnt at Cora's health camps -- ideals which would have been passed on to Cora by her own mother.

An aspect of the Sunlight League camps that saw them stand alone, was their intention to replicate the familial environment -- or in the case of children from poorly developed families, to supersede it. Many other health camps, focused as they were on increasing the physicality of human stock, preferred to take on as many children as could be accommodated. The Southern Canterbury Health Camp Committee's Summer Health Camp for 1936 had 50 children at camp, while the camps run by Ada Paterson averaged 80 children per camp.40 [Cora Wilding Papers [1.9] [report] Summer Health Camp 1936. Macmillan Brown Library; Tennant, p. 81.] Cora specifically intended to run small camps with her first consisting of a mere 4 children (due to financial considerations) and the others staying far below the norm for other camps at the time, usually accommodating between 15-30 children.41 [The children on Cora's camps were aged between 9-12 yrs. Tennant,Children's Health the Nation's Wealth, p.104, p. 107.] Small camps, following the American model, meant that each child could have more attention from the camp attendants and experience a sense of belonging and stability unavailable in the larger camps.42 [The Scouts Movement promoted the ideal of smaller camps. Wilding Family: ARC1989.124 Box 39 Folder 184 'Scouts' Item 175, 'Scouts - notebook 1930'. Canterbury Museum. Larger camps also meant that bullying and homesickness could remain unnoticed, an aspect of camp life which Cora is likely to have wished to avoid.] According to Bronwyn Dalley, child welfare in New Zealand has centred around the idea that children are best catered for by a familial environment, where what constituted the best familial environment changed through time.43 [See B. Dalley, Family Matters: Child Welfare in Twentieth Century New Zealand, Auckland, 1998, p. 365.] In light of this, Cora's preference for family-units (or hapu) in camp reflected the ideal construction which located the child within the malleable construction of the 'best family'.

Given that Cora's camps were for girls only, the prioritising of a familial structure within camp also represented the gendered notion of girls and women as belonging to the domestic sphere. The helpers at the camps run by Cora were taken from respectable Christchurch Girls' Schools (St Margarets' and Rangi Ruru) in an effort to encourage the relaxed, domestic-style settings of the camps, as well as to encourage the nurturing tendencies of the teenaged girls.44 [Tennant, Children's Health the Nation's Wealth, p. 106.] While this would have resulted in a sense of sisterly solidarity in its ideal form, it also reflected the financial restrictions of running health camps. Even when the running of camps was to fall into other hands in later years and permanent facilities were needed, Cora was still keen to retain a sense of the small familial groupings of earlier camps, promoting an idea for a dormitory style building that allowed for the division of children into smaller groups within the whole.45 [Cora's design included' ... a large central administration block with large open-air dining or community hall to seat 100 children, and with a kitchen attached. The children's sleeping accommodation was in family or 'hapu' units of 24 children.' Cora Wilding Papers [1.1] '22nd April 1936' . Macmillan Brown Library.] She also considered that while larger boys' camps could be run, it was important that girls' camps were still of a relatively intimate nature.46 [In 1936 it was decided that Cora was to run 4 smaller girls camps while Mr F. Davis was to organise and run a camp for 100, or possibly 400 boys, apparently to be financed by the T.O.C.H. Ibid., '22nd May 1936'.] For Cora, it was important that the domestic situation was a comfortable and well learned one for girl-children, seeing them as she did, in terms of the future mothers who would be at fault should they fail in their parental role and in turn adversely affect the psychological well-being of their offspring. Mothers-in-the-making especially, needed not only to know how to cook, clean and keep the family healthy, but they also had to be of sound mind, which clearly meant for Cora, an ability to work within an intimate and nurturing setting.

The explicit focus on girls within the Sunlight League Health Camps -- and within the League itself -- was another relatively unique component of their organisation. Segregated camps were the norm, but when camps were held solely for a single sex, it was more likely that boys were provided for as they were the natural sex to fit into the camping lifestyle, according to current opinions on gender. For Cora, it was important that girls be taken on camp because for one thing, girls were going to be the future mothers of the race -- it was they who were likely to be the links in the chain of health-knowledge from generation to generation and thus responsible for the health of the nation. Similarly, they were the re-producers of the nation themselves and thus should they fail to monitor their own health, they would be unfit mothers, either emotionally or physically.47 [On 'maternal feminism' see Woods.] As has been said, the small style camps of the Sunlight League worked to acclimatise the girls to the domestic environment, as well as promoting a sense of sisterhood and common understanding. Cora however, it must be pointed out, was not a mother herself and this was reflected in her belief that girls at camp and at the schools she spoke at were faced with the option of raising a family or of contributing in a meaningful way to society -- these being the qualifiers of worthy citizenship for a woman.48 [And this it will be remembered, had been the problem for Cora as an artist, in that she did not have children and was not (she believed) contributing to society as a whole through her painting, and thus decided to turn to a more visible role within the community.] Specifically, the importance of teaching health to girls who were facing a potentially childless future lay in the fact that could these women look after their own health, they would not be a burden to their families. Independence was clearly a requirement for the childless woman and ironically, an unfulfilled requirement in much of Cora's own life. However, the focus on the child-bearing potential of girls was indicative of the wider understanding of the gendered role of women at this time, especially with regards to eugenics. Healthy women, resulted in healthy children, where the specific health of the man appeared beyond the scope of the equation, unless he was found under the label 'child'.49 [The father was required to be genetically sound, but as such his bodily health was not centred in discussions of reproduction in the same way that women's were. Philippa Mein Smith has noted that within the discourses surrounding child health in the first half of the twentieth century, specifically that surrounding the Plunket Movement, 'baby' was always male. Mein Smith, p. 1.]

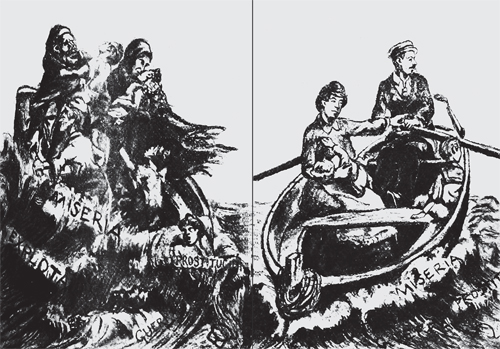

The discourse of eugenics specifically worked to embed women within the socially constructed role of breeder, where eugenics itself became a language of mothering and enforced heterosexuality for women. The gap through which women could escape was in the role of health activist -- in a sense becoming the 'mother' to the children and sick of the nation as a whole, as Cora did. Furthermore, within the imperialist discourse of eugenics the enforcement of the rightness of a lack of child-bearing by these women manifested in the explicit oppression of the poor and the racialised and medicalised other. These women placed themselves at the top of the hierarchy of motherhood by determining who could and could not breed in an ideology which they were themselves above. The mental defective and the physically inferior were burdened with the role of 'other' to justify the superiority of white middle-class women within the wider patriarchy. Such women claimed, in the name of eugenics, that certain individuals were not to breed as such breeding would pollute the nation and the race.50 [For a discussion of white women's involvement in the eugenics movement in New Zealand, see Wanhalla.] In a sense these women broke free of their gendered role, but retained their femininity by oppressing other women. While Cora was on the periphery of such manifestations of imperialist eugenics, she did focus on women as potential saviours of the race as mothers, which saw her in line with the prevailing attitudes of the time. So in a sense, Cora's camps were enforcing the dominant discourse.

From a different point of view to that given above, it can in fact be seen that Cora's camps were to a degree emancipatory and subversive with respect to the established role of women -- or at least more complex in regards to norms, than it might at first appear. Cora was attacked for her continued preference for girls at camps in the newspaper, to which she replied that should funds permit, boys camps would be run too, and that moreover, boys were already provided for by the Y.M.C.A. and Heritage camps.51 [In 1936 Dr McIntyre had written to the Press complaining that the public was unhappy with Health Stamp funds going towards a camp for girls only, Cora defended her position and attempted to make it clear that this was not representative of an anti-boys feeling on the Sunlight League's part. Cora Wilding Papers [1.9] [draft correspondence]From Cora to Editor, 27th Oct. 1936. Macmillan Brown Library.] Cora believed that boys had more ready access to the outdoors, whereas their sisters were required to learn domestic roles in a domestic setting which for Cora was bad simply because it stopped girls from benefiting from the outdoors -- from nature and beauty, for physical and mental well-being. I suspect that for Cora an emphasis on the girl-child reflected her ideas regarding both the holistic nature of health, and the idea that women were left with little to keep them occupied when involved in a somewhat stifling 'society life'. At the very least she would have hoped to be able to give the girls an understanding of the benefits of self-expression, and some tools with which to counter the repressive role for women within the social order. These girls, should they have failed to understand the importance of self in their respective lives, would have been looking at potential mental ill-health and emotional instability. This would have reflected badly in their parenting skills but would also have limited their citizenship potential, as not all women were to be mothers in Cora's understanding of the future (and as we have already seen, democracy itself was considered a healthy form of self-expression). Either way, girls needed to know how to express themselves in a socially-acceptable/healthy way -- not through psycho-somatic disorders. Society at large, was content to locate women in the home, raising children and having little engagement with the 'public sphere', and this is where the Sunlight League as a whole can be seen to reflect the pro-women stance of many of its members (a stance which was mixed with eugenics, but also overrode that ideology) in that the ideal of female-citizenship as understood by the League, necessitated that women existed beyond the ideological confines of the home for the well-being of the democratic state. Cora's taking of girl children on camp then, was in line with the ideologies surrounding girls as mothers-to-be, but was also at odds with those ideologies in that girls were treated as potential citizens first and foremost, who needed to know about the League of Nations, and who needed to be able to express themselves and recognize their role as contributors to society in a way which reflected the democratic state as Cora understood it. Women were clearly seen as the nobler of the race for Cora, but they were viewed as having a potential beyond the role of mother, which clearly reflected the ideals of womanhood held by the 'first wave feminists', that had in turn won women the vote.52 [Within the Sunlight League, Cora had been careful to stipulate in the constitutions as they were drawn up, that at least one member on the board must be a mother, and that there must be at least a specified number of women in positions of authority. This illustrates Cora's feminist belief that women had important contributions to make to the running of society as women. Regarding the Sunlight League Executive committee, the constitution was drawn up to read ' ... and one mother of a family. (At least two members of this increased Executive Committee shall be women).' Cora Wilding Papers [MB 183] [1.7] 'Annual Reports' [misc.] 'Sunlight League Rules and Regulations'. Macmillan Brown Library. A similar consideration was made for the Ford Milton Home. See Cora Wilding Papers [1.22] [misc.] 'suggested alterations to Sunlight League Constitution'. Macmillan Brown Library.]

The situating of the figure within the landscape, as a body located within a discourse of place, had implications for constructions of identity. Health camps worked within the discourses of nationalism and imperialism in two ways. The most obvious of these ways lay in the focus health camps placed on the growing of youth with the intention of creating strong defenders of the nation and empire, which placed girls in the position of mothers-in-the-making and boys in the role of defenders-of-the-nation. This was the simplest of the two ways in which camps engaged with the wider discourses, the other, while being related to the first involved the ideologies of place and bodies as has already been touched upon. Health camps worked to take the children out of the cities and into the country, emancipating them from the industrial and urban landscape in the name of health and well-being (which is also an important aspect of the camps), but they also worked to take children back to a setting that allowed them to develop national characteristics.53 [The establishment of the Youth Hostels Movement itself, led by Schirrman and brought to New Zealand by Cora, reflected this reaction against the ills present in urban living. Crookes, p. 7.] In pre-eugenic thinking, man was determined by his environment and it was simply that environment, or land, which led to racial types.A new man has emerged from the depth of the people. He has forged new theses and set forth new Tables and he has created a new people, and raised it up from the same depths out of which the great poems rise -- from the mothers, from blood and soil.

-- Intellectuals Must Belong to the People, by Hermann Burte, from Nazi Culture: Intellectual, Cultural and Social Life in the Third Reich, by George L. Mosse

Just as ideas regarding a national style within the arts had relied on the landscape for expression, so too did ideas regarding a national type of woman. Thus while health camps were taking place western-world wide, specifically to heighten the racial/national assets of the human stock that had been lost by a lack of engagement with the land in favour of industrialisation and progressively white-collar labour, in New Zealand as well as in other colonial lands, health camps represented the chance to assert a national type of one's own -- to prove one's right to land in the face of wars which threatened occupation as well as in the face of a native, 'indigenous' population. Paradoxically, while I see health camps as representative of attempts to create inalienable ownership rights to the landscape, which can be interpreted as an attempt at gaining a national identity for future New Zealanders, the prevailing ideologies present in New Zealand saw the landscape considered in terms of an antipodean British landscape which in turn meant that the unification of children with land was at one and the same time also an act of imperialism.

Throughout the wider discourse regarding health, Cora explicitly considered the Maori as a race to be in its traditional state a superior form of the human species, which placed it on an even footing with the Ancient Greeks with their love of out-door exercise. The Maori were considered to be an advanced type of 'native' from the time of early New Zealand settlement, and as such Cora was merely latching hold of an already established construction of the Maori when she compared them to the Ancient Greeks for their robust physique. This idealised construction of the 'Ancient' Maori however, was appropriated by Cora for use in the discourses surrounding Pakeha identity.54 [One of the characteristics of American culture in the late nineteenth century was a nostalgia for ideals of past societies. This preference for the Greek and Maori ideal for living exhibited by Cora and the Sunlight League is likely to be a part of this. Green, p. 17.] As Sara Ahmed explained, the 'tanned' body has the privilege of signifying a morally clean white body, but the black body, as racial signifier, indicates the 'infectability' of being black.55 [Ahmed, p. 58.] Cora's understanding of skin-colour on the other hand, saw the 'brown' body of the Maori used by the League as the token symbol of bodily health rather than disease. The reason for the construction of the 'brown' Maori as the ideal of physical health lay in the perceived out-door lifestyle which led to the race of undefeated warriors: 'brown' skin read as a people who lived outdoors under the sun and the sun was as we have seen, health-giving. Furthermore, the Maori were far from being the 'ebony black' of other racialised groups and thus their skin was not seen as being such an indicator of physiological difference. Moreover, this preference for distinguishing the Maori in terms of a tanned race rather than a black one, represented the construction of New Zealand as a (geographical) replica of Britain and thus according to the rules of pre-eugenic evolution, similar national types should have emerged in both lands.56 [This type of understanding of New Zealand comes through in Macmillan Brown's Utopias, see pp.111-3 of this thesis.] The Maori thus had to be a tanned European to enforce the imperialist understanding of New Zealand, and in turn, the Maori could be appropriated into narratives supporting the ideal of a national type and used to encourage a healthy lifestyle led out of doors. All of this focus on the skin saw the tanning of the nation's children not to just represent the health of a recently exposed and thus strengthened skin, but also understood tanning in terms of ingesting the land, where nationalism was constructed in terms of a specific quality of light within New Zealand at this time, which was also reflected in the ideologies surrounding nationalist and regionalist landscape painting. A New Zealand tan represented the specific absorption of New Zealand light, and was written in the body of the nation's children through their attendance at health camps.57 [As well as through their involvement in outdoor sport and open-air classrooms; In this way children were intended to embody the natural abundance of the land. Similar ideas about land and identity are discussed in relation to Canada in the 1920s in Katie Pickles' article on the touring of English Schoolgirls. K. Pickles, 'Exhibiting Canada: Empire, Migration and the 1928 English Schoolgirl Tour' Gender, Place, Culture, Vol. 7 No.1, 2000, pp. 81-96, esp. pp. 89-90.]Blood is a central concept in National Socialist racial doctrine. For good or bad, everything is to be decided by the state of blood. If the blood remains pure, the folk can flourish in good health for eternity and give the most advanced cultural expressions to its inner character. The folk's activities are then regarded as truly representative of its soul. But if the blood becomes mixed, then the racial level of the folk no longer remains high. This lowering of the racial worth corresponds to a decline in health and raises a question mark concerning the survivability of the particular race. If the blood is too mixed, then sickness and mortality become inevitable for the group as a whole. Beyond a certain point, any further drop in the racial level of a people cannot be reversed. Should that happen, then the racially lowered stock of people loses its claim to eternity. Another way of putting it would be to say that if the drop in racial merit passes a certain critical point, then the fateful line that delineates Jewish victory and Aryan defeat has been crossed.

But the threat of a collective sickness and death is only half of the equation. The other half is the prospect of regaining the utopian, i.e., pre-disaster, purity level of blood, which holds a magical promise. This impending magic is, after all, the psychological function of ancient and lost utopias. As the status of the myths of past utopias is converted from legend to "history," the myths now affirm that what proved attainable in the remote past is also feasible in the imminent future. And it is through this utopian affirmation that magic seems to become once again an option in history. How else could it be? So magnificent, perfect, and ideal is the utopian state of being that its inclusion as a viable option perforce crosses over into the realm of magic. The dash toward utopia is a magical leap. And this is what the Nazi blood cult was. Stripped of its biological trappings and folkish mysticism, the blood cult remains in its bare essence a grab at magical, i.e., ultramanipulative, abilities.

Although Hitler had given the blood cult a certain bent, he was mostly using well-known and prevalent ideas that preceded him. The notion that blood is the stuff of life and stands for immortality or eternity is not new in western civilization. When the prophet Isaiah (63: 1-6) wrote his poetic portrayal of the God of vengeance he used phrases such as "their lifeblood splattered on my garments" or "and I brought down their lifeblood to the earth." But it was well known by Christian biblical scholars and translators that the original term for lifeblood in the Hebrew text was "eternity" and that this term acquired the secondary meaning of blood. Thus, when the Lord splatters eternity on his garments or spills people's eternity to the ground, the reference is clearly to blood as the essence of both immortality and mortality. The English term "lifeblood" is therefore a fairly good translation. This biblical choice of the term "eternity" to designate blood alludes to hopes for immortality that were attached to the concept of blood. This particular naming of blood betrays human hopes that life, at least collective life, is eternal. But the eternity of the group serves also as a reminder of the mortality of individuals both by natural causes and by means of fatal bloodshed. Eternity may flow in blood vessels, but when it spills out of wounds it spells mortality. Thus, there is a duality even in the old biblical conception of blood that views it as the essence of life, i.e., as that precious substance that sustains life and grants eternity but also takes life away and enforces mortality.

The focus on the magical qualities of blood was later accentuated in Christianity. The Christian doctrine of the transubstantiation of the wine and wafer into the blood and body of Jesus betrays the residues of a pagan ritual in which the magical properties of the precious substance are acquired by means of an oral incorporation. The Jews were made to pay for this Christian fascination with blood through accusations of Host desecration as well as related accusations of ritual murder for the sake of the Passover ceremony. Presumably the Jews stole the Host and pierced it to make it bleed in a reenactment of the Crucifixion. And presumably the Jews also murdered Christian children in order to smear their blood over the Passover matzos. These accusations reflect a strong belief in the special powers of blood and an unshakable conviction that the wizardly Jews were somehow able to derive benefit from the blood of others. At any rate, Germany proved to be the most fertile soil for such accusations, as attested to by Max I. Dimont: "The Germans, perhaps because they were still closest to the barbaric strain which had nursed them, were the most barbaric in their persecutions. Most of the anti- Jewish measures one popularly attributes to the entire Middle Ages were of German-Austrian origin, and grew only on German soil. Here the ritual-murder charges, the Host-desecration libels, the Black Death accusations were used to whip the population into a frenzy by sadists and fetishists" (Dimont 1962, 243). What is of great interest in the above quotation is not the pathology of one group of fetishists but the fertile ground that Germany provided for blood accusations. The ground continued to remain fertile and to provide another string of blood notions that culminated in Richard Wagner, who was greatly admired by Hitler.

In composing the libretto for his opera Parsifal, Wagner resorted to older tales about the quest for the Holy Grail, which arose out of Celtic, Christian, and even Jewish origins (Anderson 1987, 13-33). In the Middle Ages there emerged from the old sources, especially Christian myths, Arthurian legends, and Celtic tales and fertility rites, a dominant theme that represented a blend of Christian and pagan notions. The theme was of the Holy Grail, which was the original chalice of the Last Supper, into which the blood of Jesus was dropped from the very lance that was used to pierce his side. This Holy Grail was a talisman with miraculous powers that made it very sought after. It could produce an inexhaustible supply of meat and, even more important, its potion could cure mortal wounds and illnesses. This set of dominant themes veered far off from the secret and ancient source of it all, which, according to Anderson (1987), was the creation of fire out of focused sunlight. These themes had captured the European popular imagination ever since the Middle Ages. The Grail Quest became an object of fantasy, but it represented an almost impossible task because the Grail could be visible only to a knight who is completely pure of heart. For generations European Christians continued to be inspired by this dominant theme of a heroic and arduous search for a bloody talisman. It should come as no surprise that eventually the notion of a quest for a container of sacred blood with healing powers lent itself to virulent racist interpretations. Richard Wagner was one of those who resorted to this kind of interpretation, and his case is important because of his great appeal to Hitler. Summing up Wagner's racist theorizing as explained in his article The Wibelungs, his essay "Heldentum," and finally his opera Parsifal, Robert Gutman stated:

The Wibelungs singled out the ancient line from which the Frankish-German and Hohenstaufen kaisers had sprung as that "one chosen race" rightfully claiming universal rule. Indeed, Wagner said, such a tradition had persisted among the Folk even during its periods of degeneracy .... Picking up the thread of the Wibelungs in "Heldentum" and pursuing a piquant bit of Wagnerian ethnological-mythological anthropology, the composer described the Aryans, the great Teutonic world leaders, as sprung from the very gods, in contrast to the colored man, to whom he conceded the rather lowly Darwinian descent from the monkey. This was Wagner the scientist, evolutionary theory having arisen during the years between the two essays. As a devout anti- Semite he found unacceptable the Biblical explanation of mankind's origin in an act of the Jewish God. Sweepingly, he declared Aryan and human history to be one, for, without fortifying themselves with an admixture of godly white blood, the colored races could achieve nothing. In this way, Wagner believed, inferior peoples had through the ages drained Aryans of an indigenous purity, their distinguishing godly features being sucked out. It was his purpose in "Heldentum" and its artistic counterpart, Parsifal, to confront Germany with the seriousness of its racial crisis -- to outline the perfection, decline, and hopes for regeneration of the debased Aryan. (Gutman 1968, 421-22)

Obviously Hitler did not need to reinvent racism, an old and well-established European tradition, one that reached explosive new heights in the nineteenth century under the impact of social Darwinism. It was during this century that the older Christian and pagan myths were given new life by the tendentious and distorted slant of evolutionary theory that applied the criterion of survival of the fittest to the social and political behaviors of various groups of human beings. By necessity this new application involved a shift of accent from the interspecies to the intraspecies arena and resulted in drawing wide distinctions between human groups as if they belonged to separate species. The unfortunate psychological need to create pseudospecies for the sake of projection and for the sake of feeling chosen, was an old, established trend, which has been described by Erikson (1968, 41, 240-41, 298-99). Now this trend was augmented by the new rush to separate the fit from the unfit. This is why social Darwinism is inherently racist and accentuates the primitive "us" versus "them" distinction. Hitler, the ideological sponger, soaked it all in from the zeitgeist, and then spewed it all out in a modified version as a new National Socialist revelation.

In a certain sense, Hitler had completed the Grail Quest and challenged the German collective with his findings. Searching for it far away was no longer necessary since it finally became visible to a modern "brave knight" of "pure heart" who has found its location. The precious blood, the divine stuff with a dual magic ability to grant immortality as well as to inflict mortality, was right here on earth and within the veins of the folk. As Vermeil (1956, 195) pointed out, "the Kingdom of the Grail was Germany, of course." Thus one possible interpretation is that the people as a whole became the long-sought-after container of magic. But in spite of the immediacy of the magic stuff, the old hurdle of its invisibility persisted for the plain people. For without proper racial awareness, people still remain oblivious to its existence and significance. Therefore, the old quest continues to take place in an ongoing struggle to make the invisible visible to the masses by means of a constant war against the Jews. Only by opening people's eyes to Jewish duping about race could the people really be made to see their own precious blood.

The central fact that the folk as a whole comprises the container of the magic stuff leads to tricky and dialectical implications. By itself the magical substance that is contained in the veins of the people does not guarantee omnipotence to the folk. Nature decrees that the precious substance is vulnerable to contamination and is itself therefore subject to the dual fate that it can dish out, i.e., immortality versus mortality. However, if the blood has proper guardians who protect its purity, then the decree of fate takes a decided turn for the better. If the magic substance of life-giving blood is protected by a race of people who know its value, then the intact blood invigorates the protectors. This is how the earthly guardians of the magical substance have a chance at exercising godly powers. This opportunity does occur whenever the correct relationship exists between folk and blood. This linked fate of the folk and its blood is both the Achilles heel and the magic wand of a race. And what activates the one or the other is the particular state of the folk's racial consciousness. A deficient awareness reduces the vigilance of protection from contamination and results in enfeeblement, while a high level of racial awareness preserves the purity and health of the all-empowering magic that flows in the folk's veins. One could say that the fate of the folk and its blood is linked because Providence willed it so. Either both decline toward an ignoble end or surge together toward a glorious omnipotence for all eternity, which in Nazi parlance received the operational definition of "a thousand years."

The dual godly aspects of blood -- something like blood giveth and blood taketh away -- were seized by Nazism as a mental adaptation to the modern shift of power from heaven to earth. Man could play God now by taking control over the manipulation of the magical substance of life and death. And since it goes without saying that men were not created equal, the most meritorious leader of the "chosen" people who were slated by fate to be the master race becomes a human god on earth. Another implication of the blood cult was that protection of the blood from Jews, Bolsheviks, and all other enemies within and without necessitates permanent war. It actually seemed proper that a grab for more power, which is what the safeguarding of the purity of blood represented, was to be accomplished by violence and war. After all, war and violence were spiritually ennobling. This basic sentiment, which penetrated many European radical movements, was given its most forceful early expression by the Frenchman Georges Sorel, who saw violence as beautiful and heroic and who regarded war as the source of morality par excellence (Sternhell 1994, 66-67). It was the increasing public fascination with Sorel's conviction of the absolute indispensability of war that reinforced Hitler's opinion that the world is not for cowardly people. Permanent war for the sake of safeguarding the blood was regarded by him and many others as a spiritual experience that befits a race of heroes. The quest for pure blood represented a quest for a spiritual substance and was therefore expected to evoke the kind of spiritual soul-searching that Hitler himself reportedly underwent during the inner battle between his sentiments and his reason. Such soul struggles over the protection of the blood were bound to be viewed as spiritual. Let us not forget that while the physical existence of the folk was perceived as a container of a divine essence, it was the blood itself that was seen as the true mystical reality within. Blood still remained a biological concept that represented the notion of the inheritance of both physical and mental characteristics. But since this inheritance included not only visible physical characteristics but also mental dispositions and capacities, the concept of blood transcended biology and evolved into a mystical notion. Holding within it the physical as well as mental inheritance of future generations, it came to symbolize the mystical essence of the folk, its cultural potential and its soul.

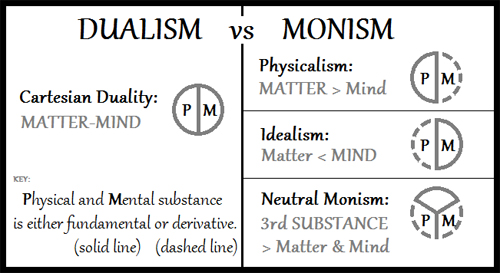

With all this in mind, it now becomes easier to understand why for Hitler the Jewish danger constituted a threat to psychophysical integrity. The dual mystical and biological aspects of blood as such already suggest an underlying notion of psychophysical integrity. In addition to that, however, as the folk becomes body while its blood evolves into spirit, notions of sickness and health are bound to revolve around psychophysical integrity. The Jewish menace threatens both body and soul or both material and spiritual reality. As indicated before, the monistic approach to the psychophysical issue links the fate of both aspects of reality. Consequently, blood became a mystical biological concept that has psychophysical integrity as its core promise and psychophysical contamination as its core threat. A proper linking of the national body and soul gives the collective the kind of magical gifts that only the gods could grant: eternal youth in good health. This is why in the folkish state, which secures this proper linkage, the folk comrades will have power and feel rooted and connected by virtue of the shared racial consciousness of being blood brothers. By the way, this included Germans everywhere from the Volga to the Atlantic and the North Sea to the Adriatic. Unlike other states, the folkish state will be a living organism, which would leave no member disconnected. This is the magic of an organic national body in whose veins flows pure blood. It is the divine magic of a complete psychophysical integrity, which is granted only by pure blood.

This sounds almost like a simple stipulation, but its ramifications were horrendous indeed. To secure pure blood, one needs to wage a permanent war against the Jews, which means thoroughly regimenting the folkish state. Regimentation is necessary not only to maintain war vigilance but also in order to meet the enormous psychophysical threat with the kind of total psychophysical state control that would be equal to the task. Pure blood cannot be secured by one battle. It is a permanent war that serves as a continuous and relentless test of the national character. Its demands are so grueling as well as intricate that the people are likely to fail the test for lack of proper guidance unless the folkish state adopts the hierarchical leadership principle.

And finally there is also one more catch in the treacherous road to acquire the magic of pure blood. It turns out that what needs to be secured is not just blood but "blood and soil." Hitler picked up this slogan from the folkish (volkisch) movement in Germany after World War I. This seemingly harmless slogan referring to the attachment of the farmer to the land was broadened to include the mystical link between members of a highly developed folk and the specific landscapes of their country. It was one more mystical notion referring to the powerful impact of the magical unity of a people and their land. As such it was still another variant of the magical expectations with regard to psychophysical integrity. Territorial expectations were also imbedded in the slogan. David Schoenbaum (1966, 50) viewed the "blood and soil" concept as a new folklore-type expression of antiurban tendencies: "The new folklore was a kind of ideology of the 'Wild East,' with the small homesteader as the cowboy and the Pole as the Indian." Sometimes concepts that float together in the zeitgeist acquire certain overlapping meanings: German attachment to soil in the "Wild East" denotes healthy farming life but also connotes an expanding lebensraum. Moreover, the deadly combination of "blood" with "soil" opened the door even further for the unleashing of an unprecedented racial mania and chauvinistic madness. Under the influence of Nazi ideology, the obsession with these twin concepts escalated into a new dual venture. One was the implementation of a final solution to the Jewish question by exterminating the blood polluters; the second was the safeguarding of the attachment of German colonists to their local soil outside Germany by expanding the German lebensraum through the great drive toward the east. This dual venture retained the underlying mystical link of a totalistic unity and integrity. The enchantment with the magic of blood was about to be converted into the kind of cataclysmic actions through which the messianic drive to secure utopia nets disaster.

-- The Roots of Nazi Psychology, by Jay Y. Gonen

Although it was common for both summer and health camps alike to re-name the members of a camp with reference to a theme, Cora's camps were a little different from other New Zealand camps in that they made recourse to Maori culture. The use of Maori imagery was reflective of Cora's understanding of a national identity, in that the Maori were an integral part of New Zealand, and specifically the part of New Zealand culture which made it unique.58 [Of colonial women in New Zealand, Philippa Wilson has written that the appropriation of indigenous culture by Pakeha was a way of acquiring authenticity as New Zealanders with a separate identity to that of the British. P. J. Wilson, pp. 184-188.] Cora wrote in a draft for a radio talk, 'There is no need for us New Zealanders to borrow greatly from Red Indian lore and names, nor from those wonderfully told jungle tales from India, we have great wealth to draw upon from our own Maori Legends.'59 [Cora Wilding Papers [1.23] [misc.]. Macmillan Brown Library.] Furthermore, Cora believed that 'the culture of every nation must arise out of its background' which was an idea taken from Cowan and Pomare, and thus the stories of other nations were irrelevant to New Zealanders and their developing sense of nationhood -- the jungle tales being the stories used at the Scout camps, and the Red Indian names and stories being used at American camps.60 [Ibid.] New Zealand then, needed its own identity through stories and names, different to those used at the other camps and rather than embracing a British identity, explicitly at least, Cora turned to the indigenous culture of the Maori. The Sunlight League emblem involved the appropriation of the legend of Maui, who snared the sun so that it would travel slower across the sky to allow womankind the benefit of its (for the Sunlight League version) health-giving rays. Cora herself designed the Maori carvings to be used at Te Wai Pounamu Girls' College, and as has been noted, believed that the Maori were at once paintable and promising of a worthy contribution to New Zealand art as artists in their own right.61 [Cora designed the school chapel alter cross, the vases and candlesticks using Maori motifs. Cora Wilding Papers [4.5] [box 1] [misc.]. Macmillan Brown Library.] Cora frequently wrote to Johannes Andersen asking advice regarding the authenticity of images and the appropriateness of Maori names for camps and plays.62 [Cora also wrote to a Mr McDonald with concern over the meaning of the figure she was going to use in a design for Te Waipounamu as the Rev. McWilliams was worried that it may have been a representation of an evil Maori spirit. Cora Wilding Papers [4.1] [correspondence] From McDonald to Cora, '2416/27'. Macmillan Brown Library.] Maori songs were performed by Sunlight League Camp children at the fund-raising Garden Parties, and those Maori children who attended Sunlight League Camps performed Maori dances for the other girls around camp fires.63 ['We had our first campfire last night, and the children loved it, and recited and sang and danced in neat formation and the two dear little Maori girls ended it with quite an exciting haka which was the item of the evening.' Cora Wilding Papers [4.2] [correspondence] From Cora to Mrs Wilding, Jan 10th. Macmillan Brown Library.] All of which would seem to point to the Pakeha appropriation of Maori culture for their own ends in an act of linguistic colonisation. It seems however, that while other New Zealand camps were mainly for Pakeha children, Cora willingly took Maori children on camp -- photographs show Maori within the groups, and obviously they were attending camp if Maori songs were performed by the children. This then, adds another dimension to Cora's use of Maori naming within the context of the camps. She was looking to unite the races in the land which they both were to inhabit but also to make Christchurch children, most of whom would have never seen a Maori, aware of the other -- 'awareness' for Cora, and the consequent 'understanding', being the path to peace and inter-racial harmony. This type of belief in harmonious inter-relation is a matrixial understanding of a world which is fulfilled in democratic peace. In her own way, Cora was working towards a sense of bi-cultural nationalism for the children of New Zealand.

-- Beauty of Health: Cora Wilding and the Sunlight League. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History in the University of Canterbury, by Nadia Gush, University of Canterbury, 2003

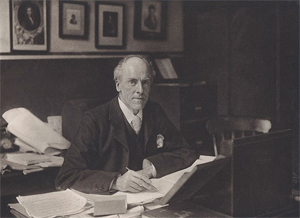

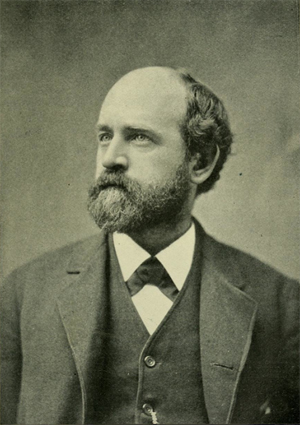

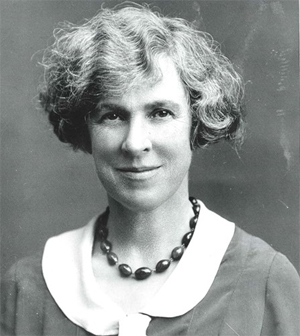

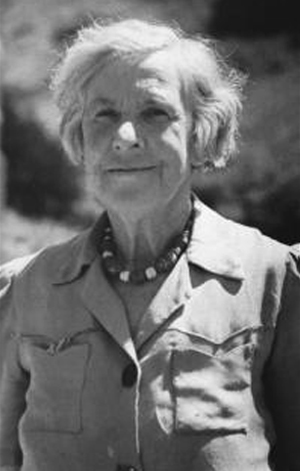

Cora Hilda Blanche Wilding MBE (15 November 1888 – 8 October 1982) was a New Zealand physiotherapist and artist, best remembered for her advocacy of outdoor activities and children’s health camps in the 1930s. She was instrumental in the founding of The Sunlight League in 1930, for which she held fundraising garden parties at "Fownhope", the Wilding family home in St Martins, Christchurch, and also the Youth Hostel Association of New Zealand in 1932. She had trained as a physiotherapist in Dunedin during World War I, and been introduced to youth hostels during her extensive European travels in the 1920s when she painted and studied outdoor activities.

Wilding was born in Christchurch, the son of Frederick and Julia Wilding, and a sister of tennis player Tony Wilding.[1] Her indulgent father was a lawyer, and an athlete and cricket and tennis player. She was educated at Nelson College for Girls, where she was captain of the hockey team and school tennis champion.

She retired as a physiotherapist in 1948, and moved from Christchurch to Kaikoura, where she painted for many years. She was made a patron of the Youth Hostel Association of New Zealand in 1938 and a life member in 1968. In the 1952 New Year Honours, she was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire for services to the community.[2] The first Christchurch youth hostel (1965–1997), formerly Avebury House the Flesher home, was called the "Cora Wilding Youth Hostel" in her honour. [3]

References

1. Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. "Wilding, Cora Hilda Blanche". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

2. "No. 39423". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 December 1951. pp. 41–43.

3. "James Flesher, Avebury House". Christchurch City Library. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

• Cora and Co: The first half-century of New Zealand youth hostelling by Dion Crooks (1982, Youth Hostel Association of New Zealand)

External links

• Cora Wilding in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography