by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/13/21

Rudrapatna Shamasastry FRAS (1868–1944) was a Sanskrit scholar and librarian at the Oriental Research Institute Mysore. He re-discovered and published the Arthashastra, an ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy.

Early life

Shamasastry was born in 1868 in Rudrapatna, a village on the banks of the Kaveri river in what is today the state of Karnataka. His early education started in Rudrapatna. He later went to the Mysore Samskruta Patasala and obtained his Sanskrit Vidwat degree with high honours. In 1889, Madras University awarded him a BA degree. Impressed by his ability in classical Sanskrit, Sir Sheshadri Iyer, the then Dewan of Mysore Province, nurtured and helped Shamasastry, making it possible for him to join the Government Oriental Library [Oriental Research Institute] in Mysore as librarian. He "had mastered Vedas, Vedanga, classical Sanskrit, Prakrit, English, Kannada, German, French and other languages."[1]

The discovery

The Oriental Research Institute was established as the Mysore Oriental Library in 1891. It housed thousands of Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts. As librarian, Shamasastry examined these fragile manuscripts daily to determine and catalogue their contents.[1]

In 1905, Shamasastry discovered the Arthashastra among a heap of manuscripts.

Formerly known as the Oriental Library, the Oriental Research Institute (ORI) at Mysore, India, is a research institute which collects, exhibits, edits, and publishes rare manuscripts written in various scripts like Devanagari (Sanskrit), Brahmic (Kannada), Nandinagari (Sanskrit), Grantha, Malayalam, Tigalari, etc.

The Oriental Library was started in 1891 under the patronage of Maharaja Chamarajendra Wadiyar X... It was a part of the Department of Education until 1916, in which year it became part of the newly established University of Mysore. The Oriental Library was renamed as the Oriental Research Institute in 1943.

From the year 1893 to date the ORI has published nearly two hundred titles. The library features rare collections such as the Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics by James Hastings, A Vedic Concordance by Maurice Bloomfield, and critical editions of the Ramayana and Mahabharata. It was the first public library in Mysore city for research and editing of manuscripts. The prime focus was on Indology. The institute publishes an annual journal called Mysore Orientalist. Its most famous publications include Kautilya's Arthashastra, written in the 4th century BC, edited by Dr. R. Shamashastri, which brought international fame to the institute when published in 1909.

One day a man from Tanjore handed over a manuscript of Arthashastra written on dried palm leaves to Dr Rudrapatnam Shamashastry, the librarian of Mysore Government Oriental Library now ORI. Shamashastry's job was to look after the library's ancient manuscripts. He had never seen anything like these palm leaves before. Here was a book that would revolutionise the knowledge of India's great past. This palm leaf manuscript is preserved in the library, now named Oriental Research Institute. The pages of the book are filled with 1500-year-old Grantha script. It looks like as if they have been printed but the words have been inscribed by hand. Other copies of Arthashastra were later discovered later in other parts of India.[1]

In this context, my mind remembering a day which was the His Excellency Krishnaraja Wodeyar went to Germany at the time of Dr. R. Shamashastry were working as a curator of Oriental Library, Mysore, The King sat in a meeting held in Germany and introduced himself as the King of Mysore State. Immediately a man stood up and asked, "Are you from our Dr. R. Shamashastry's Mysore?" Because the Arthashastra edited by him took a fame worldwide. The King wondered and came back to Mysore immediately to see Dr. R. Shamashastry, and also Dr. R. Shamashastry appointed as Asthana Vidwan. Sritattvanidhi, is a compilation of slokas by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III. Three edited manuscripts Navaratnamani-mahatmyam (a work on gemology), Tantrasara-sangraha (a work on sculptures and architecture), and Vaidashastra-dipika (an ayurvedic text), Rasa-kaumudi (on mercurial medicine) all of them with English and Kannada translation, are already in advanced stages of printing.

Oriental Research Institute

The ORI houses over 45,000 Palm leaf manuscript bundles and the 75,000 works on those leaves. The manuscripts are palm leaves cut to a standard size of 150 by 35 mm (5.9 by 1.4 in). Brittle palm leaves are sometimes softened by scrubbing a paste made of ragi and then used by the ancients for writing, similar to the use of papyrus in ancient Egypt. Manuscripts are organic materials that run the risk of decay and are prone to be destroyed by silverfish. To preserve them the ORI applies lemon grass oil on the manuscripts which acts like a pesticide. The lemon grass oil also injects natural fluidity into the brittle palm leaves and the hydrophobic nature of the oil keeps the manuscripts dry so that the text is not lost to decay due to humidity.

The conventional method followed at the ORI was to preserve manuscripts by capturing them in microfilm, which then necessitated the use of a microfilm reader for viewing or studying. Once the ORI has digitized the manuscripts, the text can be viewed and manipulated by a computer. Software is then used to put together disjointed pieces of manuscripts and to correct or fill in any missing text. In this manner, the manuscripts are restored and enhanced. The original palm leaf manuscripts are also on reference at the ORI for those interested.

-- Oriental Research Institute Mysore, by Wikipedia

He transcribed, edited and published the Sanskrit edition in 1909. He proceeded to translate it into English, publishing it in 1915.[2]

The manuscript was in the Early Grantha script. Other copies of the Arthashastra were discovered later in other parts of India.

It was one of the manuscripts in the library that had been handed over by 'a pandit of the Tanjore district' to the Oriental Library.[3]

4 Rao (1958: 1, 3) considers Shamasastry the discoverer of the Arthasastra: ‘With the discovery of Kautilya’s Artha Sastra by Dr. R. Shama Sastri in 1905, and its publication in 1914, much interest has been aroused in the history of ancient Indian political thought; [p. 1]. . . . The Artha Sastra ¯ . . . is a compendium and a commentary on all the sciences of Polity that were existing in the time of Kautilya. It is a guidance to kings. . . . Artha Sastra ¯ contains thirty-two paragraphical divisions [Books]. . . . with one hundred and fifty chapters, and the Sastra is an illustration of a scientific approach to problems of politics, satisfying all the requirements and criteria of an exact science’ [p. 3]. But going back to the preface of the standard work and translation by Shamasastry (1967: vi), it is revealed that the manuscript of Kautilya’s Arthasastra ¯ was actually discovered by a person described merely as ‘a Pandit of the Tanjore District’ who handed it over ‘to the Mysore Government Oriental Library’ of which Shamasastry was the librarian.

-- Review and Extension of Battacharyya's Modern Accounting Concepts in Kautilya's Arthasastra, by Richard Mattessich

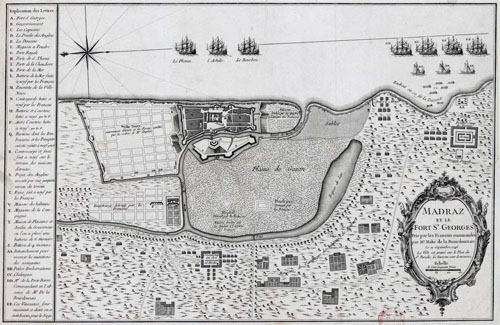

Saraswathi Mahal Library, also called Thanjavur Maharaja Serfoji's Saraswathi Mahal Library is a library located in Thanjavur (Tanjore), Tamil Nadu, India. It is one of the oldest libraries in Asia established during 16th century by Nayakas of Thanjavur and has on display a rare collection of Palm leaf manuscripts and paper written in Tamil and Sanskrit and a few other languages indigenous to India...

The Saraswathi Mahal library was started by Nayak Kings of Tanjavur as a Royal Library for the private intellectual enrichment of Kings and their family of Thanjavur (see Nayaks of Tanjore) who ruled from 1535 CE till 1676 CE. The Maratha rulers who captured Thanjavur in 1675 promoted local culture and further developed the Royal Palace Library until 1855. Most notable among the Maratha Kings was Serfoji II (1798–1832), who was an eminent scholar in many branches of learning and the arts.Serfoji II

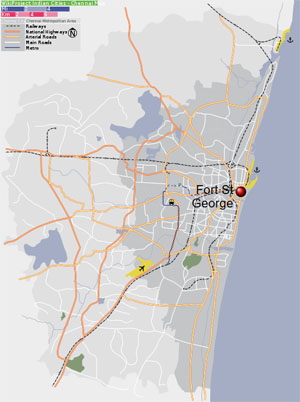

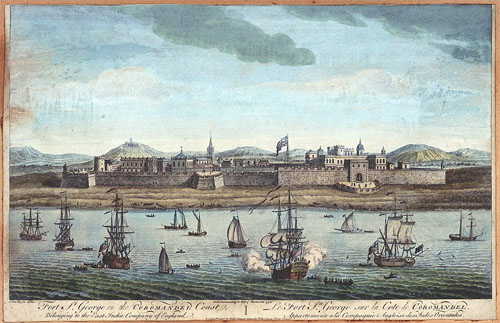

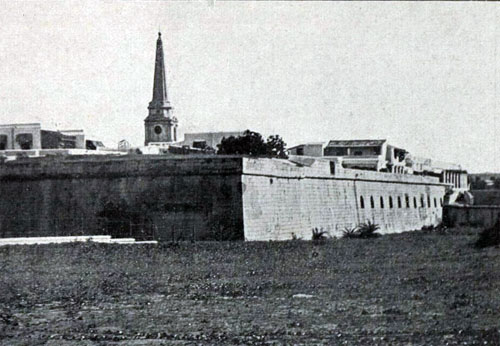

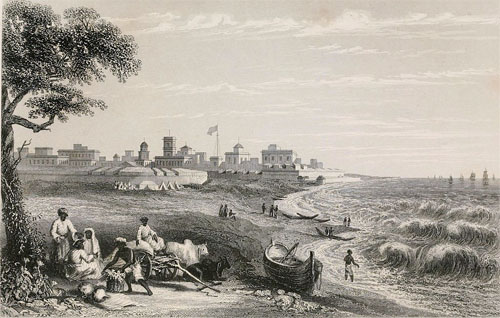

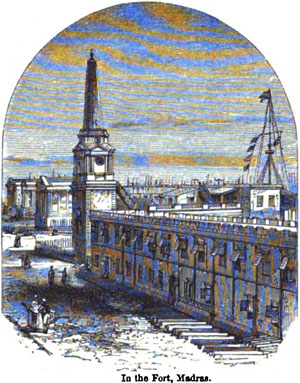

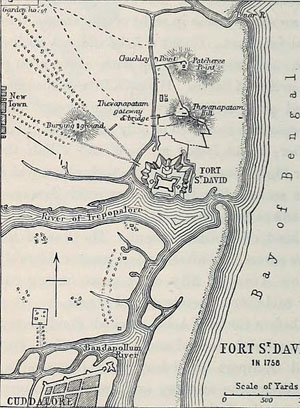

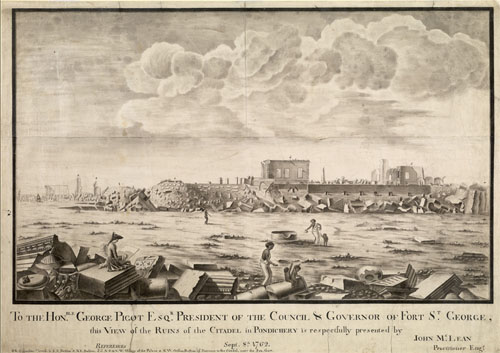

Thuljaji was succeeded by his teenage son Serfoji II in 1787. Soon afterwards, he was deposed by his uncle and regent Amarsingh who seized the throne for himself. With the help of the British, Serfoji II recovered the throne in 1798. A subsequent treaty forced him to hand over the reins of the kingdom to the British East India Company, becoming part of the Tanjore District (Madras Presidency) [Presidency of Fort St. George]. The district collectorate system was installed thereafter to manage the public revenues. Serfoji II was however left in control of the Fort and the surrounding areas. He reigned till 1832. His reign is noted for the literary, scientific and technological accomplishments of the Tanjore country.

-- Thanjavur Maratha kingdom [Tanjore], by Wikipedia

In his early age Sarfoji studied under the influence of the German Reverent Schwartz [Christian Friedrich Schwarz], and learned many languages including English, French, Italian and Latin. He enthusiastically took special interest in the enrichment of the Library, employing many Pandits to collect, buy and copy a vast number of works from all renowned Centres of Sanskrit learning in Northern India and other far-flung areas.

-- Saraswathi Mahal Library, by Wikipedia

Until this discovery, the Arthashastra was known only through references to it in works, including those by Dandin, Bana, Vishnusarma, Mallinathasuri, Megasthenes, as well as others.

The prelude section of the Panchatantra identifies an octogenarian Brahmin named Vishnusharma (IAST: Viṣṇuśarman) as its author. He is stated to be teaching the principles of good government to three princes of Amarasakti. It is unclear, states Patrick Olivelle, a professor of Sanskrit and Indian religions, if Vishnusharma was a real person or himself a literary invention. Some South Indian recensions of the text, as well as Southeast Asian versions of Panchatantra attribute the text to Vasubhaga, states Olivelle. Based on the content and mention of the same name in other texts dated to ancient and medieval era centuries, most scholars agree that Vishnusharma is a fictitious name.

-- Panchatantra, by Wikipedia

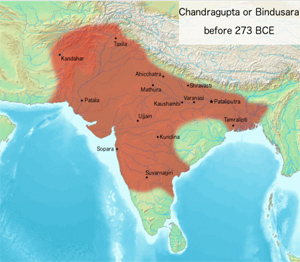

Megasthenes (/mɪˈɡæsθɪniːz/ mi-GAS-thi-neez; Ancient Greek: Μεγασθένης, c. 350BCE– c. 290 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian, diplomat and Indian ethnographer and explorer in the Hellenistic period. He described India in his book Indika, which is now lost, but has been partially reconstructed from literary fragments found in later authors. Megasthenes was the first person to describe ancient India, and for that reason he has been called "the father of Indian history".

Biography

While Megasthenes's account of India has survived in the later works, little is known about him as a person, except that he spent time at the court of Sibyrtius, who was a satrap of Arachosia under Antigonus I and then Seleucus I. and was an ambassador for Seleucid king Seleucus I Nicator and to the court of the Mauryan King Chandragupta Maurya in Pataliputra (modern Patna). Dating for his journey to the Mauryan court is uncertain.

-- Megasthenes, by Wikipedia

This discovery was "an epoch-making event in the history of the study of ancient Indian polity".[4] It altered the perception of ancient India and changed the course of history studies, notably the false belief of European scholars at the time that Indians learnt the art of administration from the Greeks.[1]

The book was translated into French, German and many other languages.[1]

Other work

He started his career as Librarian, Government Mysore Oriental Library. From 1912–1918, he worked as Principal at the Sri Chamarajendra Samskrita Maha Patashala in Bengaluru. In the year 1918, he returned to the Government Mysore Oriental library and joined as Curator and later Director of Archeological Researches in Mysore, where he would continue to work until his retirement in 1929. Apart from discovering Kautilya's Arthashastra, he pursued his research in the Vedic era and Vedic astronomy, making valuable contributions to Vedic studies. The following are among Shamasastry's works:

1. Vedangajyautishya – A Vedic Manual of Astronomy, 8th Century B.C.

2. Drapsa: The Vedic Cycle of Eclipses – a key to unlock the treasures of the Vedas.[5]

3. Eclipse-Cult in the Vedas, Bible, and Koran – A supplement to the Drapsa. It is this Cult that has given rise to epic and puranic tales in India. The mathematical aspect of eclipse-cycles is treated at great length and eclipse-tables have been appended. Dr. E. Abegg, Professor, University of Zurich, Switzerland, stated- 'I see with admiration that R Shamasatry, a thorough scholar in the difficult problems of Vedic Astronomy and Calendar, things of which European Indianists have very rarely a true Knowledge' [6]

4. Gavam Ayana- The Vedic Era- is an exposition of a forgotten sacrificial calendar of the Vedic poets and includes an account of the origin of the Yugas.[7]

5. Evolution of Indian Polity. This book is a compilation of Ten lectures delivered in Calcutta University. Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, Vice-chancellor of Calcutta University, personally invited Sastry to deliver these discourses. In this work, the ancient Indian administrative systems and various levels of administrative set-up are critically examined, on the basis of Vedas, legends, Arthashastra, Mahabharata, Jainagama works etc.[8]

6. The Origin of Devanagari Alphabets.[9]

All his works received great attention from many great Scholars around the world, particularly European Indianists.

R. Shamasastry also edited many Kannada Texts. Some of the important works he published are:

• Rudrabhaṭṭa's Jagannāthavijaya (1923)

• Nayasena's Dharmāmṛta (part I in 1924 & part II 1926)

• Lingannakavi's Keḷadinṛpavijaya (1921)

• Govindavaidya's Kaṇṭhīravanarasarajavijaya (1926)

• The Virāṭa Parvan of Kumāravyāsa's Karnataka Mahābhārata (1920)

• The Udyoga Parvan of Kumārayvāsa's Karnataka Mahābhārata (1922)

Awards

Shamasastry's work was acclaimed by Ashutosh Mukherjee, Rabindranath Tagore, and others. Shamasastry also met Mahatma Gandhi in 1927 at Nandi Hills.[2] The discovery brought international fame to the institute.[10]

Outside India, Shamasastry's discovery was hailed by Indologists and Orientalists such as Julius Jolly, Moriz Winternitz, F. W. Thomas, Paul Pelliot, Arthur Berriedale Keith, Sten Konow and others.[1] J. F. Fleet wrote of Shamasastry: "We are, and shall always remain, under a great obligation to him for a most important addition to our means of studying the general history of ancient India."[2]

Shamasastry was awarded a doctorate in 1919 from the Oriental University in Washington D.C. and in 1921 from Calcutta University.[11] He was made a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society and won the Campbell Memorial gold medal.

Several titles were also conferred on him, including Arthashastra Visharada by the Maharaja of Mysore, Mahamahopadhyaya by the Government of India and Vidyalankara and Panditaraja by the Varanasi Sanskrit Mandali.[12]

Recognition in Germany

An often-told anecdote involves the visit of the then-king of Mysore, Krishna Raja Wadiyar IV, to Germany. When introduced as the king of Mysore, he was asked by the vice-chancellor of a German university whether he was from the Mysore of Shamasastry. On his return, the king honoured Shamasastry and said "In Mysore we are the Maharaja and you are our subject, but in Germany, you are the master and people recognise us by your name and fame."[1][2]

Later life

Shamasastry continued his research work on Indological problems.[1] He later became the curator of the institute.[2] As Director of Archaeology of Mysore State, he discovered many inscriptions on stone and copper plates.[1]

His house Asutosh, in the Chamundipuram locality of Mysore, was named after Sir Asutosh Mookerjee.[2]

Notes

1. Prof. AV Narasimha Murthy (21 June 2009), "R Shamasastry: Discoverer of Kautilya's Arthasastra", The Organiser

2. Sugata Srinivasaraju (27 July 2009), "Year of the Guru", Outlook India

3. Richard Mattessich (2000), The beginnings of accounting and accounting thought: accounting practice in the Middle East (8000 B.C. to 2000 B.C.) and accounting thought in India (300 B.C. and the Middle Ages), Taylor & Francis, p. 146, ISBN 978-0-8153-3445-3

4. Ram Sharan Sharma (2009), Aspects of political ideas and institutions in ancient India (4 ed.), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., p. 4, ISBN 978-81-208-0827-0

5. R. Shamasastry (1938), Drapsa: The Vedic Cycle of Eclipses : a Key to Unlock the Treasures of the Vedas, Sri Panchacharya Electric Press

6. R. Shamasastry (1940), Eclipse-cult in the Vedas, Bible and Koran: A Supplement to the "Drapsa", Sri Panchacharya Electric Press

7. R. Shamasastry (1908), Gavam Ayana the Vedic Era, R. Shamasastry, 1908

8. R. (Rudrapatna) Shama Sastri (2009), Evolution of Indian Polity, HardPress, 2012, ISBN 9781290797320

9. R. (Rudrapatna) Shama Sastri (2009), The Origin of the Devanagari Alphabets, Bharati-Prakashan, 1973, ISBN 9781290797320

10. A monumental heritage, The Hindu, 27 October 2001.

11. "Annual Convocation". University of Calcutta. Archived from the original on 28 May 2012.

12. "Annual Convocation". Karnataka Samskruta University.

External links

• Texts from Wikisource

• Data from Wikidata

• Text of 1915 Shamasastry translation