Fort St. George, India

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/13/21

Rao (1958: 1, 3) considers Shamasastry the discoverer of the Arthasastra: ‘With the discovery of Kautilya’s Artha Sastra by Dr. R. Shama Sastri in 1905, and its publication in 1914, much interest has been aroused in the history of ancient Indian political thought; [p. 1]. . . . The Artha Sastra ¯ . . . is a compendium and a commentary on all the sciences of Polity that were existing in the time of Kautilya. It is a guidance to kings. . . . Artha Sastra ¯ contains thirty-two paragraphical divisions [Books]. . . . with one hundred and fifty chapters, and the Sastra is an illustration of a scientific approach to problems of politics, satisfying all the requirements and criteria of an exact science’ [p. 3]. But going back to the preface of the standard work and translation by Shamasastry (1967: vi), it is revealed that the manuscript of Kautilya’s Arthasastra was actually discovered by a person described merely as ‘a Pandit of the Tanjore District’ who handed it over ‘to the Mysore Government Oriental Library’ of which Shamasastry was the librarian.

-- Review and Extension of Battacharyya's Modern Accounting Concepts in Kautilya's Arthasastra, by Richard Mattessich

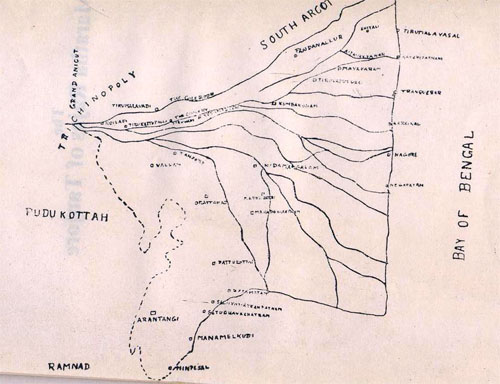

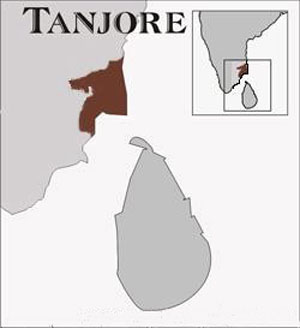

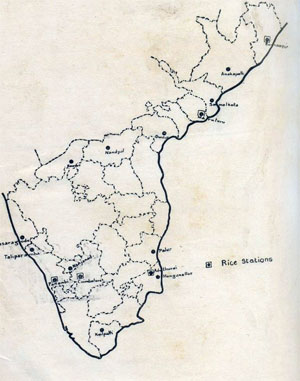

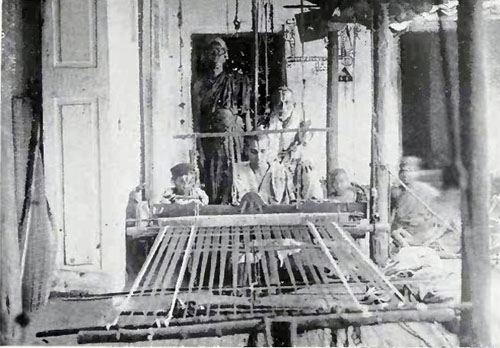

Tanjore District was one of the districts in the erstwhile Madras Presidency of British India. It covered the area of the present-day districts of Thanjavur, Tiruvarur, Nagapattinam, Mayiladuthurai and Aranthangi taluk, karambakudi taluk of Pudukkottai District in Tamil Nadu. Apart from being a bedrock of Hindu orthodoxy, Tanjore was a centre of Chola cultural heritage and one of the richest and most prosperous districts in Madras Presidency.

-- Tanjore District (Madras Presidency), by Wikipedia

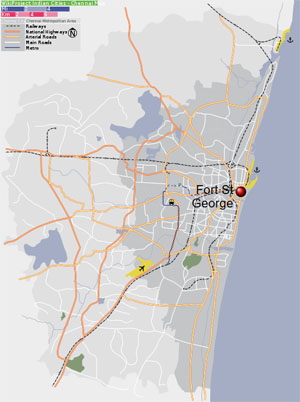

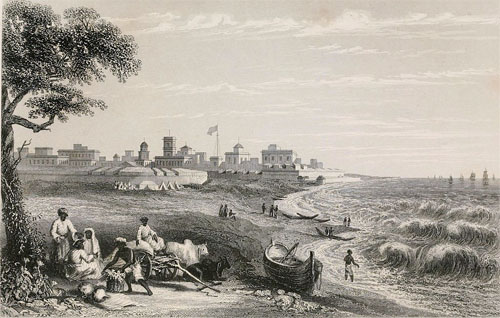

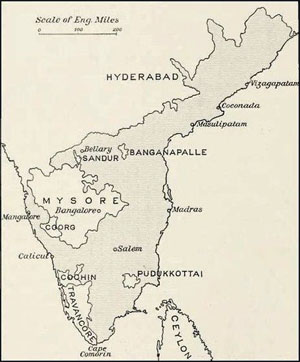

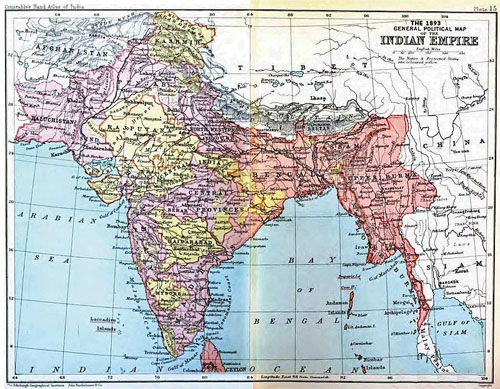

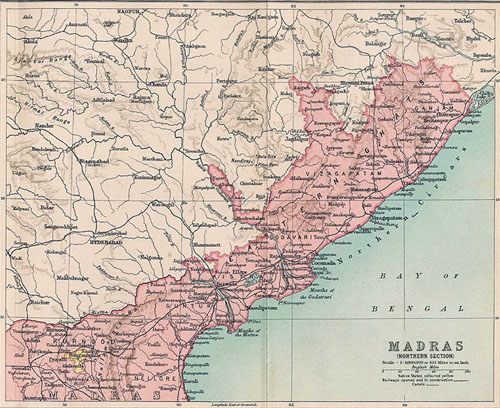

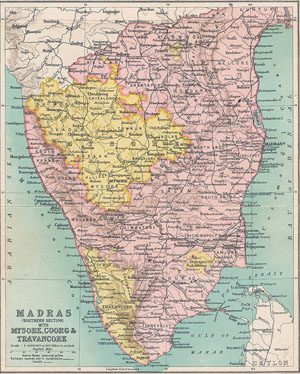

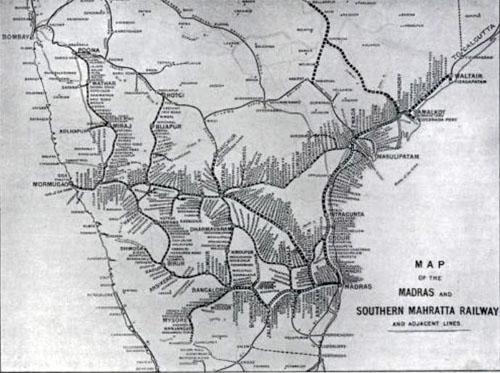

The Madras Presidency, or the Presidency of Fort St. George, and also known as Madras Province, was an administrative subdivision (presidency) of British India. At its greatest extent, the presidency included most of southern India, including the whole of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, and parts of Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Karnataka, Telangana, Odisha and the union territory of Lakshadweep. The city of Madras was the winter capital of the Presidency and Ootacamund or Ooty, the summer capital. The Island of Ceylon was a part of Madras Presidency from 1793 to 1798 when it was created a Crown colony. Madras Presidency was neighboured by the Kingdom of Mysore on the northwest, Kingdom of Cochin on the southwest, and the Kingdom of Hyderabad on the north. Some parts of the presidency were also flanked by Bombay Presidency (Konkan) and Central Provinces and Berar (Madhya Pradesh).

-- Madras Presidency, by Wikipedia

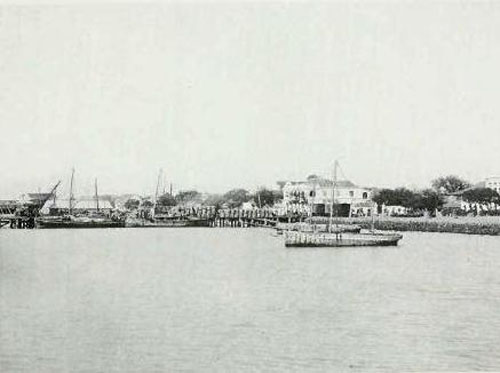

PONDICHERRY

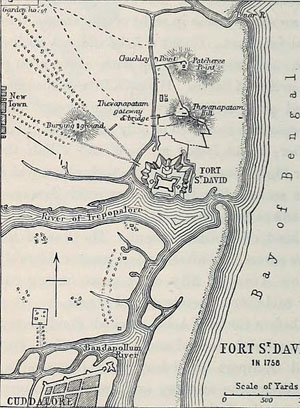

Quite near Fort St. David, in an arid plain without a port, the French bought, like the others, from the Soubeidar of the Deccan province, a small piece of land where they built a station, which they later made into a town of considerable importance, — the Pondicherry of which we have already spoken. At first, it was merely a trading centre surrounded by a thick hedge of acacias, palms, cocoanut trees, and aloes, and it was called “the boundary hedge."...

LALLI BEGINS BY BESIEGING THREE PLACES AND TAKING THEM.

As soon as he arrived, he besieged three places: one was Kudalur, [Old name for Cuddalore. Voltaire says Goudalour.] a little fort three miles from Pondicherry; the second was Saint David, a much bigger fortress; the third Devikota, [Voltaire says Divicotey.] which surrendered as he approached. It was flattering for him to have under his orders, in these first expeditions, a Count d’Estaing, descendant of that d’Estaing who saved the life of Philip Augustus at the battle of Bovine, and who transferred to his family the arms of the kings of France; a Constans, whose family was so old and famed, a La Fare, and many other officers of the first rank. It was not customary to send out young men of big families to take service in India. It would certainly have been necessary to have more troops and money with them. However, the Count d' Estaing had taken Kudalur in a day; and the day after, the General, followed by this flower of manhood, had gone to lay siege to the important station of St. David.

A NAVAL BATTLE BETWEEN ADMIRAL POCOCK AND ADMIRAL D'ACHE: 29th APRIL 1758

Not a minute was lost between the two rival nations. While Count d’Estaing was taking Kudalur, the English Fleet, commanded by Admiral Pocock, was attacking that of Comte d'Ache on the coast of Pondicherry. Men wounded or killed, broken masts, torn sails, tattered rigging, were the sole results of this indecisive battle. The two damaged fleets remained in those parts, equally unable to injure one another. The French was the worst treated — it had only forty dead, but five hundred men had been wounded, including Comte d’Ache and his captain, and after the battle, by bad luck, a ship of seventy-four cannons was lost on the coast. But a palpable proof that the French Admiral [We give the name of admiral to the chief of a squadron because it is the title of the English chiefs of squadrons. The "Grand Admiral” is in England what the admiral is in France. (V.)] shared with the English Admiral the honour of the day, is that the Englishmen did not attempt to send help to the besieged Fort St. David.

Everything was opposed in Pondicherry to the enterprise of the General. Nothing was ready to second him. He demanded bombs, mortars, and utensils of all kinds, and they had not got any. The siege dragged along; people began to fear the disgrace of abandoning it; even money was lacking. The two millions brought by the fleet and given to the treasury of the Company were already spent. The Merchants’ Council of Pondicherry had thought it necessary to pay their immediate debts in order to revive their credit, and had issued orders to Paris that, if help of ten millions was not forthcoming, everything would be lost. The Governor of Pondicherry, the successor of Godeheu, on behalf of the Merchants’ administration, wrote to the General on the 24th May this letter, which was received in the trenches:“My resources are exhausted and we have no longer any hope left unless we are successful. Where shall I find resources in a country ruined by fifteen years of war, enough to pay the expenses of your army and of a squadron from which we were hoping for a great deal of help. On the contrary, there is nothing.”

This single letter explains the cause of all the disasters which had been experienced and of all those that followed. The more the want of necessary things was felt in the town, the more the General was blamed for having undertaken the siege of Fort St. David.

In spite of so many defeats and obstacles, the General forced the English commander to yield. In St. David were found one hundred and eighty cannons, all kinds of provisions which were lacking in Pondicherry, and money of which there was a still greater lack. There was three hundred thousand pounds in coin, which was all forwarded to the treasury of the Company. We are only noting here facts on which all parties agree.

THE 2ND JULY 1758. LALLI PUTS THIS COMBAT ON THE 3RD OF AUGUST IN HIS MEMOIRS. IT IS A MISTAKE.

Count Lalli demolished this fortress and all the surrounding small farms. It was an order of the Minister: an ill-fated order which soon brought sad reprisals. As soon as Fort St. David had been taken, the General left to conquer Madras. He wrote to M. de Bussi who was then in the heart of the Deccan: “As soon as I become the master of Madras, I am going to the Ganges, either by land or sea. My policy can be summarized in these five words: 'No more English in the Peninsula.'” His great zeal was unquenchable, and the fleet was not in a fit condition to back him up. It had just attempted a second naval battle in sight of Pondicherry, which was even more disastrous than the first. Comte d'Ache received two wounds, and, in this bloodthirsty fight, he had resisted the attacks of a naval army, twice as strong as his own, with five dilapidated ships. After this conflict, he demanded masts, provisions, rigging and crew from the Town Council. He got nothing. The General on the sea was no more helped by this exhausted Company than the General on the land. He went to the Ile de France near the coast of Africa to find what he had not been able to discover in India.

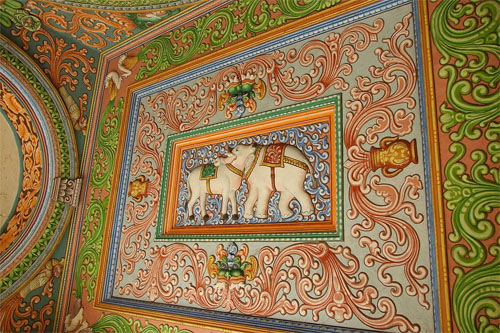

At the beginning of the Coromandel coast is quite a beautiful province called Tanjore. The Raja of this land, whom the French and the English called “King”, was a very rich prince. The Company claimed that this prince owed them about thirteen millions in French money.

THE ACTIONS AND LETTERS OF THE JESUIT LAVOUR

The Governor of Pondicherry, on behalf of the Company, ordered the General to demand this money again with his sword in his hand. A French Jesuit, named Lavour, the head of the Indian Mission, told him and wrote to him that Providence blessed this project in an unmistakable manner. We shall be forced to speak again of this Jesuit who played an important and tragic part in all these happenings. All we need say at present is that the General, on his journey, passed over the territory of another small prince, whose nephews had a short time before offered four lakhs of rupees to the Company in order to obtain their uncle's small state and expel him from the country. This Jesuit eagerly persuaded Count Lalli to do this good work. This is one of his letters, word for word:”The law of succession in those countries is the law of the strongest. You must not regard the expulsion of a prince here as on the same level as in Europe.”

He told him in another letter:You must not work simply for the glory of the King’s arms. A word to the wise ...”

This act reveals the spirit of the country and of the Jesuit.

The Prince of Tanjore sought the help of the English in Madras. They got ready to create a diversion, and he had time to admit other auxiliary troops into his capital which was threatened by a siege. The little French army did not receive from Pondicherry either provisions or the necessary ammunition, and they were forced to abandon the attempt. Providence did not bless them as much as the Jesuit had foretold. The Company received money neither from the Prince nor from the nephews who wished to dispossess their uncle.

GENERAL LALLI IN A PECULIAR KIND OF DANGER

As they were preparing to retreat, a negro of those parts, the commander of a group of negro cavalry men in Tanjore, came and presented himself to the advance guard of the French Camp followed by fifty horsemen. He said that they wanted to speak to the General and enter his service. The Count was in bed, and came out of his tent practically naked with a stick in his hand. Immediately the negro captain aimed a sword blow at him, which he just managed to parry, and the other negroes fell on him. The General's guard ran up instantly and nearly all the assassins were killed. That was the sole result of the Tanjore expedition.

CHAPTER XIV: COUNT LALLI BESIEGES MADRAS. HIS MISFORTUNES BEGIN.

At last, after useless expeditions and attempts in this part of India, and in spite of the departure of the French fleet, which was believed to be threatened by the English, the General recommenced his favourite project of besieging Madras.

“You have too little money and too few provisions”, people said to him: he replied “We shall take them from the town”. A few members of the Pondicherry Council lent him thirty-four thousand rupees. The farmers of the village or aldees [Aldee is an Arab word, preserved in Spain. The Arabs who went to India introduced there many terms from their language. Well-proved etimology often serves as a proof of the emigration of peoples.] of the Company advanced some money. The General also put his own into the fund. Forced marches were made, and they arrived in front of the town which did not expect them.

MADRAS TAKEN ON THE 13TH DECEMBER 1758.

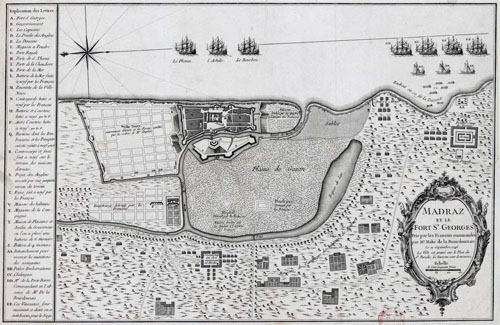

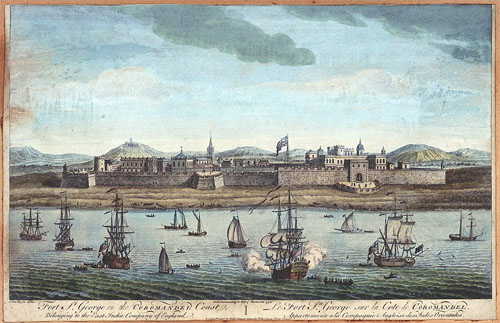

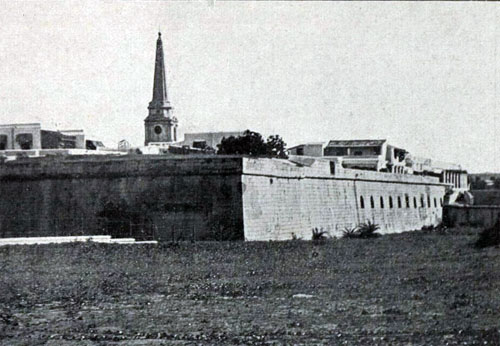

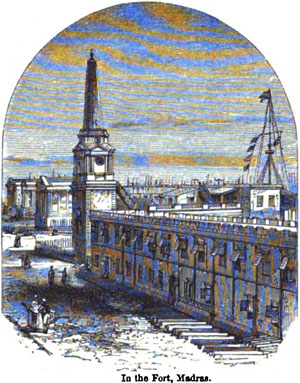

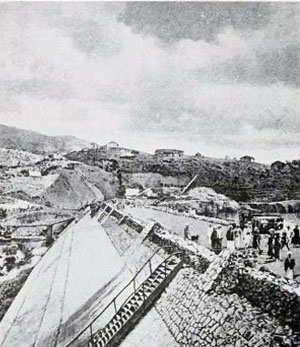

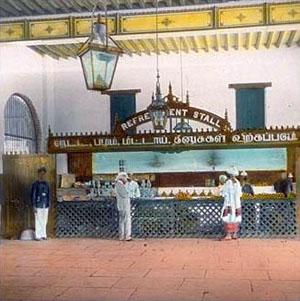

Madras, as is well known, is divided into two parts, very different from one another. The first, where Fort St. George is, is well fortified, and has been so since Bourdonnaye’s expedition. The second is much bigger and is inhabited by merchants of all nations. It is called the “Black City”, because the “Blacks” are most numerous there. It occupies such a large space that it could not be fortified; a wall and a ditch formed its defense. This huge, rich town, was pillaged.

It is easy to imagine all the excesses, all the barbarities into which rushes the soldier who has no rein on him, and who looks upon it as his incontestible right to murder, violate, burn, rape. The officers controlled them as long as they could, but the thing that stopped them the most was the fact that as soon as they entered the town, they had to defend themselves there. The Madras garrison fell on them; a street battle ensued; houses, gardens, Hindu, Muslim and Christian temples became battlefields where the attackers, loaded with booty, fought in disorder those who came to snatch away their spoils. Count d’Estaing was the first to attack English troops who were marching on the main road. The Lorraine batallion, which he was commanding, had not yet fully reassembled, and so he fought practically alone and was made a prisoner. This misfortune brought more in its wake, because, after being sent by sea to England, he was thrown at Portsmouth into a frightful prison: treatment which was unworthy of his name, his courage, our customs and English generosity.

The capture of Count d’Estaing, at the beginning of the fight, was likely to cause the loss of the little army, which, after having taken the “Black City” by surprise, was taken by surprise itself in return. The General, accompanied by all the French nobility of which we have spoken, restored order. The English were forced back right to the bridge built between Fort St. George and the "Black City”, The Chevalier of Crillon rushed up to this bridge, and killed fifty English there. Thirty-three prisoners were made and they remained masters of the town.

The hope of taking Fort St. George soon, as La Bourdonnaye had done, inspired all the officers, but the most strange thing of all was that five or six million inhabitants of Pondicherry rushed up to the expedition out of curiosity, as if they were going to a fair. The force of the besiegers numbered only two thousand seven hundred European infantry, and three hundred cavalry men. They had only ten mortars and twenty cannons. The town was defended by sixteen thousand Europeans in the infantry and two thousand five hundred sepoys. Thus the besieged were stronger by eleven thousand men. In military tactics, it is agreed that ordinarily five besiegers are required for one besieged. Examples of the taking of a town by a number equal to the number defending it are rare: to succeed without provisions is rarer still.

What is most sad is the fact that two hundred French deserters went into Fort St. George. There is no other army where desertion is more frequent than the French army, from a natural uneasiness in the nation or from hope of being better treated elsewhere. These deserters appeared at times on the ramparts, holding a bottle of wine in one hand and a purse in the other. They exhorted their compatriots to imitate their example. For the first time, people saw a tenth of the besieging army taking refuge in the besieged town.

The siege of Madras, light-heartedly undertaken, was soon looked upon as impracticable by everybody. Mr. Pigot, the representative of the English Government and Governor of the town, promised fifty thousand rupees to the garrison if it defended itself well and he kept to his word. The man who pays in this way is better served than the man who has no money. Count Lalli had no other option but to try an attack. But, at the very time when this daring act was being prepared, in the port of Madras appeared six warships, part of the English fleet which was then near Bombay. These ships were bringing reinforcements of men and munitions. On seeing them, the officer commanding the trench deserted it. They had to raise the siege in great haste and go to defend Pondicherry, which was even more vulnerable to the English than Madras....

***

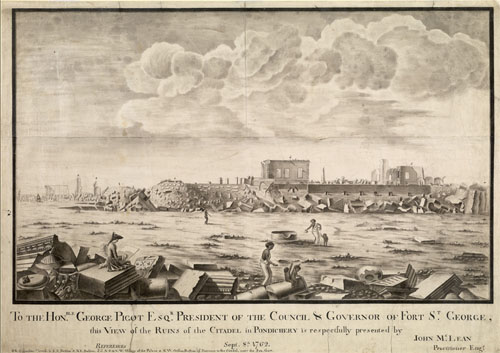

CHAPTER XVII: THE CAPTURE AND DESTRUCTION OF PONDICHERRY

While the English army was advancing towards the West and a new fleet was threatening the town in the East, Count Lalli had very few soldiers. He made use of a trick, quite usual in war and in civil life: he tried to appear to have more than he really had. He ordered a parade on the walls of the town on the seaward side. He issued instructions that all the employees of the Company should appear in uniform as soldiers, in order to overawe the enemy fleet which was alongside.

A THIRD REVOLT

The Council of Pondicherry and all its employees came to him to say that they could not obey this order. The employees said that they recognized as their Commander only the Governor established by the Company. All ordinary bourgeois think it degrading to be a soldier, although in reality it is the soldiers who give us empires. But the real reason is that they wished to cross in everything the man who had incurred the hatred of the people.

It was the third revolt which he had patched up in a few days. He only punished the heads of the faction by making them leave the town; but he insulted them with crushing words which are never forgotten, and which are bitterly remembered when one has the opportunity of revenge.

Further, the General forbade the Council to meet without his permission. The enmity of this Company was as great as that of the French Parliament’s was against the Commanders who brought the strict orders of the Court to them — often contradictory ones. He had therefore to fight citizens and enemies.

The place lacked provisions. He had houses searched for the few superfluous goods to be found there, in order to provide the troops with food necessary for their subsistence. Those who were entrusted with this sad task did not carry it out with enough discretion with regard to most of the important officers, whose name and position deserved the greatest tact. Feelings, already irritated, were wounded beyond the limit: people cried out against the tyranny. M. Dubois, Commissary of Stores, who carried out this task, became the object of public condemnation. When conquering enemies order such a search, nobody dare even whisper, but when the General ordered it to save the town, everyone rose against him.

The officers were reduced to a half-pound of rice per day; the soldiers to four ounces. The town had no more than three hundred black soldiers and seven hundred French, pressed by hunger, to defend itself against four thousand European soldiers and ten thousand black ones. They would have to surrender. Lalli, in despair, shaken by convulsions, his spirit lost and overcome, wished to give up the command in favour of the Brigadier of Landivisiau, who took good care not to accept such a delicate and tragic post. Lalli was forced to order the misfortune and shame of the colony. In the midst of all these crises, he was daily receiving anonymous notes threatening him with the sword and poison. He actually believed himself to be poisoned: he fell into an epileptic fit, and the Missionary Lavour went to the townspeople to tell them that they must pray to God for the poor Irishman who had gone mad.

However, the danger was increasing; English troops had broken down the unhappy line of troops who were surrounding the town. The General wished to assemble a mixed Civil and Military Council which should try to obtain a surrender acceptable to the town and the colony. The Council of Pondicherry replied only by refusing, "You have broken us,” they said, “and we are no longer worth anything.” “I have not broken you,” replied the General, ”I have forbidden you to meet without my permission, and I command you, in the name of the King, to assemble and form a mixed Council to calm down the strong feelings in the whole colony as well as your own.” The Council replied with this summons which they intimated to him:“We summon you, in the name of the religious orders, of all the inhabitants and of ourselves to order Mr. Coote (the English commander) to suspend arms immediately, and we hold you responsible to the King for all the misfortunes to which ill-timed delay may give rise.”

The General thereupon called a Council of War, composed of all the principal officers still in service. They decided to surrender, but disagreed as to the conditions. Count Lalli, angered against the English who had, he said, violated on more than one occasion the cartel established between the two nations, made a separate declaration, in which he blamed them for breaking treaties. It was neither tactful nor wise to talk to the conquerors about their faults, and embitter those to whom he wished to surrender. Such, however, was his character.

Having told them his complaints, he asked them to grant protection to the mother and sisters of a Rajah, who had taken refuge in Pondicherry, when the Rajah had been assassinated in the very camp of the English. He reproached them bitterly, as was his wont, for having allowed such barbarism. Colonel Coote did not reply to this insolent statement.

THE JESUIT LAVOUR PROPOSES CAPITULATION

The Council of Pondicherry, on its side, sent terms of capitulation, drawn up by the Jesuit Lavour, to the English Commander. The missionary carried them himself. This conduct might have been good enough in Paraguay, but it was not good enough for the English. If Lalli offended them by accusing them of injustice and cruelty, they were even more offended at a Jesuit of intriguing character being deputed to negotiate with victorious warriors. The Colonel did not even deign to read the terms of the Jesuit: he gave him his own. Here they are:“Colonel Coote desires the French to offer themselves as prisoners of war, to be treated according to interests of his master the King. He will show them every indulgence that humanity demands.

He will send tomorrow morning, between eight and nine o'clock, the grenadiers of his regiment, who will take possession of the Vilnour door.

The day after tomorrow, at the same time, he will take possession of the St. Louis door.

The mother and the sisters of the Rajah will be escorted to Madras. Every care will be taken of them, and they will not be given up to their enemies.

Written in our General Headquarters, near Pondicherry, on the 15th January 1761.”

They had to obey the orders of General Coote. He entered the town. The small garrison laid aside their arms. The Colonel did not dine with the General, with whom he was annoyed, but with the Governor of the Company, M. Duval de Leirit, and a few members of the Council.

THE ENGLISH ENTER PONDICHERRY

Mr. Pigot, the Governor of Madras for the English Company, laid claim to his right on Pondicherry: they could not deny it, because it was he who was paying the troops. It was he who ruled everything after the conquest.Pigot entered the service of the East India Company in 1736, at the age of 17; after nineteen years he became governor and commander-in-chief of Madras in 1755. Having defended the city against the French in 1758-1759 and occupied Pondichéry on behalf of the company, he resigned his office in November 1763 and returned to the Kingdom of Great Britain, being made a baronet in 1764. After selling the family seat of Peplow Hall, Shropshire, he purchased Patshull Hall, Staffordshire, in 1765 for £100,000.

That year he obtained the seat of Wallingford in the Parliament of Great Britain, which he retained until 1768. In 1766 he was created an Irish peer as Baron Pigot, of Patshull in the County of Dublin. From 1768 until his death he sat in the British House of Commons for Bridgnorth. Pigot was created an LL.D. of the university of Cambridge on 3 July 1769.

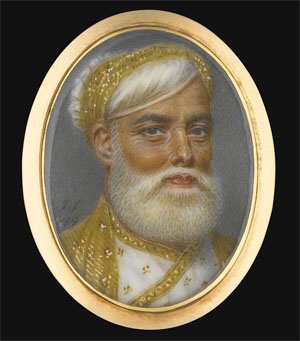

Returning to India in 1775 to reoccupy his former position at Madras, Pigot was at once involved in a fierce quarrel with the majority of his council which arose out of the proposed restoration of Thuljaji, the rajah of Tanjore.

Controversy and restoration

In April 1775, Pigot was appointed governor and commander-in-chief of Madras in the place of Alexander Wynch. He resumed office at Fort St. George on 11 December 1775, and soon found himself at variance with some of his council. In accordance with the instructions of the directors he proceeded to Tanjore, where he issued a proclamation on 11 April 1776 announcing the restoration of the Raja, whose territory had been seized and transferred to Muhammed Ali Khan Wallajah, Nawab of the Carnatic in spite of the treaty which had been made during Pigot's previous tenure of office. Upon Pigot's return from Tanjore the differences in the council became more accentuated. Paul Benfield had already asserted that he held assignments on the revenues of Tanjore for sums of vast amount lent by him to the Nawab, as well as assignments on the growing crops in Tanjore for large sums lent by him to other persons. He now pleaded that his interests ought not to be affected by the reinstatement of the raja, and demanded the assistance of the council in recovering his property. Pigot refused to admit the validity of these claims, but his opinion was disregarded by the majority of the council, and his customary right to precedence in the conduct of business was denied. The final struggle between the governor and his council was on a comparatively small point—whether his nominee, Mr. Russell, or Colonel Stuart, the nominee of the majority, should have the opportunity of placing the administration of Tanjore in the hands of the Raja. In spite of Pigot's refusal to allow the question of Colonel Stuart's instructions to be discussed by the council, the majority gave their approval to them, and agreed to a draft letter addressed to the officer at Tanjore, directing him to deliver over the command to Colonel Stuart. Pigot thereupon declined to sign either the instructions or the letter, and declared that without his signature the documents could have no legal effect. At a meeting of the council on 22 August 1776, a resolution was carried by the majority denying that the concurrence of the governor was necessary to constitute an act of government. It was also determined that, as Pigot would not sign either of the documents, a letter should be written to the secretary authorizing him to sign them in the name of the council. When this letter had been signed by George Stratton[4] and Henry Brooke, Pigot snatched it away and formally charged them with an act subversive of the authority of the government. By the standing orders of the company, no member against whom a charge was preferred was allowed to deliberate or vote on any question relating to the charge. Through this ingenious manœuvre, Pigot obtained a majority in the council by his own casting vote, and the two offending members were subsequently suspended. On 23 August, the refractory members, instead of attending the council meeting, sent a notary public with a protest in which they denounced Pigot's action on the previous day, and declared themselves to be the "only legal representatives of the Honourable Company under this presidency". This protest was also sent by them to the commanders of the king's troops, and to all persons holding any authority in Madras. Enraged at this insult, Pigot summoned a second council meeting on the same day, at which Messrs. Floyer, Palmer, Jerdan, and Mackay, who had joined Messrs. Stratton and Brooke and the commanding officer, Sir Robert Fletcher, in signing the protest, were suspended, and orders were at the same time given for the arrest of Sir Robert Fletcher. On the following day Pigot was arrested by Colonel Stuart and conveyed to St. Thomas's Mount, some nine miles from Madras, where he was left in an officer's house under the charge of a battery of artillery. The refractory members, under whose orders Pigot's arrest had been made, immediately assumed the powers of the executive government, and suspended all their colleagues who had voted with the governor. Though the government of Bengal possessed a controlling authority over the other presidencies, it declined to interfere.

In England, the news of these proceedings excited much discussion. At a general court of the proprietors, a resolution that the directors should take effectual measures for restoring Lord Pigot, and for inquiring into the conduct of those who had imprisoned him, was carried on 31 March 1777, by 382 votes to 140. The feeling in Pigot's favour was much less strong in the court of directors, where, on 11 April following, a series of resolutions in favour of Pigot's restoration, but declaring that his conduct in several instances appeared to be reprehensible, was carried by the decision of the lot, the numbers on each side being equal. At a subsequent meeting of the directors, after the annual change in the court had taken place, it was resolved that the powers assumed by Lord Pigot were "neither known in the constitution of the Company nor authorised by charter, nor warranted by any orders or instructions of the Court of Directors". Pigot's friends, however, successfully resisted the passing of a resolution declaring the exclusion of Messrs. Stratton and Brooke from the council unconstitutional, and carried two other resolutions condemning Pigot's imprisonment and the suspension of those members of the council who had supported him. On the other hand, a resolution condemning the conduct of Lord Pigot in receiving small presents from the Nawab of Arcot, the receipt of which had been openly avowed in a letter to the court of directors, was carried. At a meeting of the general court held on 7 and 9 May a long series of resolutions was carried by a majority of ninety-seven votes, which censured the invasion of Pigot's rights as governor, and acquiesced in his restoration, but at the same time recommended that Pigot and all the members of the council should be recalled in order that their conduct might be more effectually inquired into. Owing to Lord North's opposition, Governor Johnstone failed to carry his resolutions in favour of Lord Pigot in the House of Commons on 21 May. The resolutions of the proprietors having been confirmed by the court of directors, Pigot was restored to his office by a commission under the company's seal of 10 June 1777, and was directed within one week to give up the government to his successor and forthwith to return to England.

Death

Meantime Pigot died on 11 May 1777, while under confinement at the Company's Garden House, near Fort St. George, whither he had been allowed to return for change of air in the previous month. At the inquest held after his death, the jury recorded a verdict of willful murder against all those who had been concerned in Pigot's arrest. The real contest throughout had been between the Nawab of Arcot and the Raja of Tanjore. Members of the council took sides, and Pigot exceeded his powers while endeavouring to carry out the instructions of the directors. The proceedings before the coroner were held to be irregular by the supreme court of judicature in Bengal, and nothing came of the inquiry instituted by the company. On 16 April 1779, Admiral Hugh Pigot brought the subject of his brother's deposition before the House of Commons. A series of resolutions affirming the principal facts of the case was agreed to, and an address to the king, recommending the prosecution of Messrs. Stratton, Brooke, Floyer, and Mackay, who were at that time residing in England, was adopted. They were tried in the King's Bench before Lord Mansfield and a special jury in December 1779, and were found guilty of a misdemeanour in arresting, imprisoning, and deposing Lord Pigot. On being brought up for judgment on 10 February 1780, they were each sentenced to pay a fine of £1,000, on payment of which they were discharged.

-- George Pigot, 1st Baron Pigot, by Wikipedia

General Lalli was all the time very ill; he asked the English Governor for permission to stay four more days in Pondicherry. He was refused. They indicated to him that he must leave in two days for Madras.

We might add, since it is rather a strange thing, that Pigot was of French origin, just as Lalli was of Irish origin: both were fighting against their old fatherland.

LALLI ILL-TREATED BY HIS FOLLOWERS

This harshness was the least that he suffered. The employees of the Company, the officers of his troops, whom he had mortified without consideration, united against him. The employees, above all, insulted him right up to the time of his departure, putting up posters against him, throwing stones at his windows, calling out loudly that he was a traitor and a scoundrel. The band of people grew bigger as idlers joined it, and they, in turn, soon became inflamed by the mad anger of the others. They waited for him in the place through which he was to be carried, lying on a palanquin, followed at a distance by fifteen English hussars who had been chosen to escort him during his journey to Madras. Colonel Coote had allowed him to be accompanied by four of his guards as far as the gate of the city. The rebels surrounded his bed, loading insults upon him, and threatening to kill him. They might have been slaves who wanted to kill with their swords one of their companions. He continued his march in their midst holding two pistols in his weakened hands. His guards and the English hussars saved his life.

THE COMMISSARY OF STORES OF THE ARMY ASSASSINATED

The rebels attacked M. Dubois, an old and brave officer, seventy years old and Commissary of Stores for the Army, who passed by a moment later. This officer, the King’s man, was assassinated: he was robbed, stripped bare of clothes, buried in a garden, and his papers immediately seized and taken away from his house, since when they have never been seen.

While General Lalli was being taken to Madras, the employees of the Company obtained permission in Pondicherry to open his boxes, thinking that they would find there his treasure in gold, diamonds and bills of exchange. All they found was a little plate, clothes, useless papers, and it maddened them even more.

5TH MARCH 1761

Bowed down with sorrow and illness, Lalli, a prisoner in Madras, asked in vain for his transport to England to be delayed: he could not obtain this favour. They carried him by force on board a trading ship, whose captain treated him cruelly during the voyage. The only solace given him was pork broth. This English patriot thought it his duty to treat in this way an Irishman in the service of France. Soon the officers, the Council of Pondicherry and the chief employees were forced to follow him but, before being transferred, they had the sorrow of seeing the demolition begun of all the fortifications that they had made for their town, and the destruction of their huge shops, their markets, all that was used for trade and defence, even to their own houses.

Mr. Dupre, chosen as Governor of Pondicherry by the Council of Madras, hurried on this destruction. He was (according to our information) the grandson of one of those Frenchmen whom the strictness of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes forced to become an exile from their fatherland and fight against it. Louis XIV did not expect that in about eighty years the capital of his India Company would be destroyed by a Frenchman.

The Jesuit Lavour wrote to him in vain: Are you equally anxious, Sir, to destroy the house in which we have a domestic altar where we can practice our religion secretly?”

Dupre was little concerned with the fact that Lavaor was saying the Mass in secret: he replied that General Lalli had razed St. David to the ground and had only given three days to the inhabitants in which to take away their possessions, that the Governor of Madras had granted three months to the inhabitants or Pondicherry and that the English were at least equal to the French in generosity, but that he must go and say the Mass elsewhere. Thereupon the town was razed to the ground pitilessly, without the French having the right to complain.

CHAPTER XVIII: LALLI AND THE OTHER PRISONERS ARE CONDUCTED TO ENGLAND AND RELEASED ON PAROLE. CRIMINAL SUIT AGAINST LALLI.

The prisoners, on the journey and in England, continued their mutual reproaches which despair made even more bitter. The General had his partisans, above all among the officers in the regiment bearing his name. Almost all the others were his enemies: one man would write to the French Ministers; another would accuse the opposite party of being the cause of the disaster. But the real cause was the same as in other parts of the world: the superiority of the English fleet, the carefulness and perseverance of the nation, its credit, its ready money, and that spirit of patriotism, which is stronger in the long run than the trading spirit and greed for riches.

General Lalli obtained permission from the Admiralty in England to enter France on parole. The majority of his enemies obtained the same favour: they arrived preceded by all the complaints and the accusations of both sides. Paris was flooded with a thousand writings. The partisans of Lalli were very few and his enemies innumerable.

A whole Council, two hundred employees without resources, the Directors of the India Company seeing their huge establishment reduced to nothing, the shareholders trembling for their fortune, irritated officers; everybody flew at Lalli with all the more fury because they believed that in their losing he had acquired millions. Women always less restrained than men in their fears and their complaints, cried out against the traitor, the embezzler, the criminal guilty of high treason against the king.

The Council of Pondicherry, in a body, presented against him in front of the Controller-General. In this petition, they said: “It is not a desire to avenge the insults and our ruin which is our motive -- it is the force of truth, it is the pure feeling of our consciences, it is the popular complaint against him."

It seemed however that “the pure feelings of conscience” had been somewhat corrupted by the grief of having lost everything, by a personal hatred, perhaps excusable, and by a thirst for vengeance which cannot be excused.

A very brave officer of the ancient nobility, badly insulted without cause, whose honour, even, was involved, wrote in a manner even more violent than the Council of Pondicherry: “This is," he said, “what a stranger without a name, with no deeds to his credit, without family, without a title, but none the less loaded with the honours of his master, prepares for the whole colony. Nothing was sacred in his sacrilegious hands: as a leader he even laid his hands on the altar appropriating six silver candlesticks, which the English General made him give back in response to the request of the head of the Capucines,” etc.

The General had brought on himself, by his indiscretion, his impetuosity, and his unjust reproaches, this cruel accusation: it is true that he had the candlesticks and the crucifix carried to his own house, but so publicly that it was not possible that he should wish to take possession of such a small thing, in the midst of so many big things. Therefore the sentence which condemned him does not speak of sacrilege.

The reproach of his low birth was very unjust: we have got his titles together with the seal of King John. His family was very old. People therefore were overstepping the limit with him just as he had done with so many others. If anything ought to inspire men with a desire for moderation, it is this tragic event.

The Finance Minister ought naturally to protect a trading company whose ruin was liable to do so much harm to the country: a secret order was given to shut Lalli in the Bastille. He himself offered to give himself up: he wrote to the Duke of Choiseul: “I am bringing here my head and my innocence. I am awaiting your orders."

The Duke of Choiseul, Minister of War and Foreign Affairs, was generous to a fault, genial and just: the highness of his ideals equalled the breadth of his opinions, but, in an affair so important and complicated, he could not go against the clamorous demands of all Paris, nor neglect the host of imputations against the accused. Lalli was shut up in the Bastille in the same room where La Bourdonnaye had been and, like him, did not emerge from it.

It remained to be seen what judges they would give him. A Council of War seemed to be the most suitable tribunal, but he was also accused of misappropriation of funds, embezzlement, and crimes of peculation of which the Marshals of France are not the judges. Count Lalli at first only brought accusations against his enemies, who therefore tried to reply to them in some way. The case was so complicated, it was necessary to call so many witnesses, that the prisoner remained fifteen months in the Bastille without being examined, and without knowing the tribunal before which he was to plead. “That,” several legal experts used to say, “is the tragic destiny of the citizens of a kingdom, famous for its arms and its arts but lacking in good laws, or rather a kingdom where the wise old laws have been sometimes forgotten.”

THE JESUIT LAVOUR DIES. 1,250,000 POUNDS FOUND IN HIS CASH BOX.

The Jesuit Lavour was then in Paris: he was asking the Government for a modest pension of four hundred francs so that he might go and pray to God for the rest of his days in the heart of Perigord where he was born. He died, and twelve hundred and fifty thousand pounds were found in his cash box, and more in diamonds and bills of exchange. This deed of a Mission Superior from the East, and the case of the Superior of the Western Missions, La Valette, who went into bankruptcy at the same time, with three millions in debts, excited over the whole of France an indignation equal to that which was excited against Lalli. This was one of the causes which finally got the Jesuits abolished, but, at the same time, the cash box of Lavour settled the fate of Lalli. In this trunk were found two books of memoirs, one in favour of Lalli, the other charging him with all kinds of crimes. The Jesuit was to make use of one or the other of these writings, according to the turn which affairs took. These documents were a double-edged sword, and the one that harmed Lalli was delivered to the Attorney-General. This supporter of the King complained to Parliament against the Count on account of his oppression, embezzlement, treachery, and high treason. Parliament referred the suit in the first instance to the Chatelet. Soon afterwards, letters patent of the King sent to the High Tribunal and to the "Tournelle" information of all the malpractices in India so that steps may be taken against the perpetrators in accordance with the severity of the ordinances. It might have been better to stress the word justice rather than the word severity.

As the Attorney-General had accused him of the crimes of high treason and treachery against the Crown, he was denied a counsel. For his defence, he had no other help except his own. They allowed him to write, and he took advantage of this permission -- to his own undoing. His writings annoyed his enemies all the more and made new foes. He reproached Count d'Ache with being the cause of his loss in India, because he did not remain before Pondicherry. But as chief of a squadron, d’Ache had definite orders to defend the Isles of Bourbon and France against a threatened invasion. He was accusing a man who had himself fought three times against the English fleet, and had been wounded during these three battles. He blamed the Chevalier of Soupire violently, and he was answered with a moderation as praiseworthy as it is rare.

Finally, testifying that he had always rigidly done his duty, he gave vent to the same excesses with his pen as formerly he used to do with his tongue. If he had been granted a counsel, his defence would have been more circumspect, but he all the time thought that it was enough to believe oneself innocent. Above all, he forced M. de Bussi to give a reply that was as mortifying as it was well written. All impartial men saw with sorrow two brave officers like Lalli and de Bussi, both of tried valour, who had risked their lives a hundred times, pretend to suspect one another of lack of courage. Lalli took too much upon himself by insulting all his enemies in his memoirs. It was like fighting alone against an army, and it was impossible for him not to be overwhelmed. The talk of a whole town makes an impression on the judges even when they believe they are on their guard against such an influence.

-- Voltaire Fragments on India. Translated by Freda Bedi, B.A. Hons. (Oxon.)

Francis Ellis’ research

The text was difficult to assess because it was neither Hindu nor Christian, and indeed neither exclusively Indian nor exclusively European. The distinctive Europeanness of some of its ideas would not be apparent to believers in natural religion, and it was hard to test its claim to be a Veda, when before Colebrooke’s survey of 1802 there was little knowledge of what a Veda or the Veda was. The person who did the most to settle the matter was Francis Whyte Ellis (1777 1819), who like Colebrooke was an official of the East India Company doing research in his spare time. The Ezour-Védam, like India itself, passed from the French-speaking to the English-speaking world.In 1781–82 Antoine-Louis-Henri Polier, a [French] Swiss Protestant who served in the English East India Company’s army until 1775, had had copies of the Vedas made for him at the court of Pratap Singh at Jaipur. Polier’s intermediary was a Portuguese physician, Don Pedro da Silva Leitão… Jai Singh had assembled a substantial collection of manuscripts from religious sites across India, and in the time of his successor Pratap Singh the library had contained the samhitas of all four Vedas in manuscripts dating from the last quarter of the seventeenth century…

Polier records that he had sought copies of the Veda without success in Bengal, Awadh, and on the Coromandel coast, as well as in Agra, Delhi, and Lucknow and had found that even at Banaras “nothing could be obtained but various Shasters, [which] are only Commentaries of the Baids”…

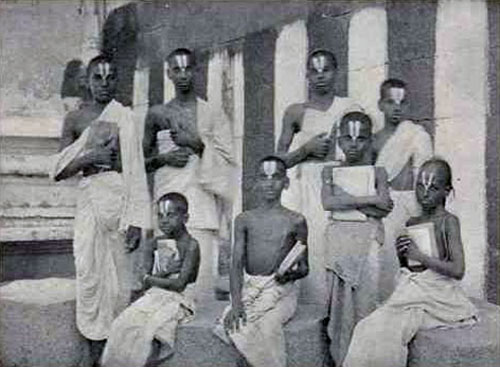

It is perhaps significant that it was in a royal library, rather than in a Brahmin pathasala, that Polier found manuscripts of the Vedas. But the same is not true of the manuscripts acquired in Banaras only fifteen years later by Henry Thomas Colebrooke, during the period (1795–97) when he was appointed as judge and magistrate at nearby Mirzapur…I cannot conceive how it came to be ever asserted that the Brahmins were ever averse to instruct strangers; several gentlemen who have studied the language find, as I do, the greatest readiness in them to give us access to all their sciences. They do not even conceal from us the most sacred texts of their Vedas.

The several gentlemen would likely have included General Claude Martin, Sir William Jones, and Sir Robert Chambers. These were all East India Company employees who obtained Vedic manuscripts (Jones from Polier) in the last decades of the eighteenth century.

Why was it so much easier for Polier, Colebrooke, and others to obtain what it had been so difficult for the Jesuits and impossible for the Pietists?...

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will SweetmanThe two greatest empires were the British and the French; allies and partners in some things, in others they were hostile rivals. In the Orient, from the eastern shores of the Mediterranean to Indochina and Malaya, their colonial possessions and imperial spheres of influence were adjacent, frequently overlapped, often were fought over. But it was in the Near Orient, the lands of the Arab Near East, where Islam was supposed to define teal and racial characteristics, that the British and the French countered each other and “the Orient” with the greatest intensity, familiarity, and complexity. For much of the nineteenth century, as Lord Salisbury put it in 1881, their common view of the Orient was intricately problematic: “When you have got a ...faithful ally who is bent on meddling in a country in which you are deeply interested -- you have three courses open to you. You may renounce -- or monopolize -- or share. Renouncing would have been to place the French across our road to India. Monopolizing would have been very near the risk of war. So we resolved to share.”

And share they did, in ways that we shall investigate presently. What they shared, however, was not only land or profit or rule; it the kind of intellectual power I have been calling Orientalism. In a sense Orientalism was a library or archive of information commonly and, in some of its aspects, unanimously held. What bound the archive together was a family of ideas and a unifying set of values proven in various ways to be effective. These ideas explained the behavior of Orientals; they supplied Orientals with a mentality, a genealogy, an atmosphere; most important, they allowed Europeans to deal with and even to see Orientals as a phenomenon possessing regular characteristics.

-- Orientalism, by Edward W. Said

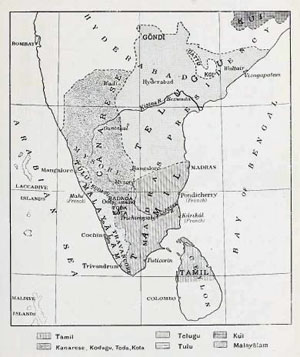

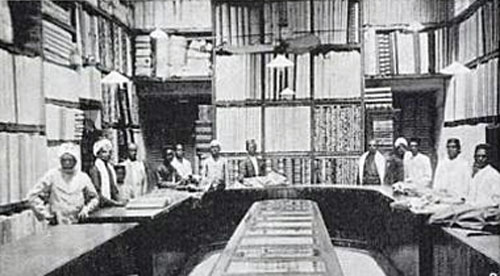

Ellis was employed in the East India Company’s base at Fort St. George (Madras / Chennai). His greatest scholarly achievement was to show the existence of a Dravidian family of languages, distinct from the Indo-Aryan family -– an idea that is taken for granted now, but which was not widely accepted until it was developed further by Robert Caldwell some forty years later. Ellis presented it in an introduction to someone else’s book, a grammar of Telugu written by A. D. Campbell for the company’s trainees in the College of Fort St. George, the South Indian counterpart to the College of Fort William in Calcutta.

In 1816, Ellis visited the former Jesuit mission in Pondicherry, and examined a collection of eight books of manuscript, in romanized Sanskrit reflecting Bengali pronunciation and French spelling, with a French version on the facing page. Some of the books contained more than one text, some contained part of one and part of another, and one contained a fair copy of the contents of some of the others. Some of the paper had a watermark with the date 1742. Some passages lacked the translation, while one, which is the Ezour-Védam, had the French but no Sanskrit. From the samples given by Ellis, we find that the Sanskrit is in ślokas, often irregular, and the French version is abridged -– or else, if the French was the original, the Sanskrit was expanded. The titles all contain the word Veda, e.g. Zozochi kormo bédo (apparently yajuṣ-karma veda), Zosur Beder Chakha27 (yajur-vedasya śākhā), La chaka du Rik et de28 Ezour védam (ṛg-veda śākhā, yajur-veda śākhā) Chama Védan (sāma-veda), Odorbo Bedo Chakha (atharva-veda-śākhā). One text, Rik Opo Bédo (perhaps ṛg-upaveda) has the title also in Tamil script reflecting Tamil pronunciation, irukku-vedam (ṛg-veda). He describes them as ‘an instance of literary forgery, or rather, as the object of the author or authors, was certainly not literary distinction, of religious imposition without parallel’ (Ellis 1822: 1).

Ellis’ description was read in a paper to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1817, and published in 1822. It is all the more important because, as mentioned already, the manuscripts are now lost (Rocher 1984: 74); Ellis’ article is the source of Rocher’s description as well as mine. They were last described at first hand by J. Castets, S.J., in a monograph published in Pondicherry in 1935; he says they have deteriorated since Ellis’ time, and even his description is mainly based on Ellis.

There are still many uncertainties about these texts:Who wrote the Sanskrit ślokas, and why?

Why were the ślokas transcribed in an inconsistent and ambiguous romanization, instead of being preserved in an Indic script?

Who wrote the French version, and why?

Why are they called Vedas?

The first and second of the above questions do not apply to the Ezour-Védam, which has no Sanskrit version, but only to the other texts in the collection, which are now lost except for the samples published by Ellis. In the case of the Ezour-Védam, Rocher argues that there was no Sanskrit original; the text was written in French, by any one of a number of Jesuit missionaries, in order to be translated into Sanskrit.29 The author must have been someone familiar with European ideas, and with a knowledge of Purānic tradition, but probably a faulty knowledge, since there are so many oddities in Vyāsa’s accounts.30

-- Ezour-Védam: Europe’s illusory first glimpse of the Veda, by Dermot Killingley