Besides Besant and Bradlaugh, several other department heads for Our Corner became regular contributors, at least for a time. Propelled by the “Art Corner,” Aveling entered the lists with multi-part articles on literature and science, although his break with Bradlaugh over financial irregularities in the National Secular Society led to his complete departure from the journal’s pages by the end of its second year.22 For both Shaw and Reed, too, the “Art Corner” served as a launching pad to independent articles. The same can be said for Utley with respect to the “Science Corner” after he inherited it from Besant, and both J. Horner and W. Mawer moved back and forth between established scientific series and entries of their own devising. Robertson was a mainstay throughout the entirety of Our Corner. Besides filling in the gaps in the “Young Folks Corner,” particularly with respect to biographies of “Real Heroes,” he displayed his own range of expertise, whether supplying a quotidian entry like “On Diary Keeping” (July 1883) or developing substantial critical articles on the poetry of Browning and Tennyson. Politically aligned with both Besant and Bradlaugh when the journal was first established, he wrote articles like “Thoughts on Home Rule” (October–November 1883) during its first year, and even though Besant’s increasing involvement with Socialism began to distance him (like Bradlaugh) from the journal’s Socialist affiliation during its last two years, he still found opportunities to publish authentic pieces like “England Before and Since the French Revolution” (May–June 1888) and “Comptism from a Secularist Point of View” (November 1888) alongside Socialist polemics.23

Meanwhile, Besant’s involvement with the “Science Corner” had ceased by the end of 1886, with Utley assuming its responsibilities from 1887 through the first half of 1888; throughout 1885, her “Peeps through a Microscope” had given way to Horner’s “Work for the Microscope.” The timing of these turnovers corresponds to a combination of Besant’s growing concerns about the evictions of tenant farmers in Ireland and her introduction of “Socialist Notes” as a regular feature. By then, she had paved the way for the many physical and natural science articles by E.D. Fryer (domestic pets), Joseph Symes (the telescope), Horner (glaciers and household pests), Aveling (insects and flowers), Laurence Small (nebular theory), and Mawer (rocks, mountains, and shells). Hypatia Bradlaugh (now Bonner) figures as well into this accounting with her series, “Chats about Chemistry” (1885–86). After all, she had taken science classes with Besant at London University in the late 1870s, and they had both been denied access to the Botanical Gardens on the grounds that they might be bad influences on the daughters of the professors who frequented them. Even Huxley had contributed to this expulsion, choosing to interpret Fruits of Philosophy as recommending birth control methods that might be equally applied to extra-marital sexual relations.24 Either Besant never knew about his alliance with her persecutors or she rose above their petty politics, for she continued to endorse his every measure. At the end of her first year’s entries to the “Science Corner,” she writes, “Professor Huxley delivered a brilliant and characteristic address at the opening of the London Hospital Medical School, on the relations of the State to the medical profession. . . . It is pleasant to hear the voice of any eminent man speaking against the tendency to grandmotherly legislation which is now so common” (OC 2.5.297).

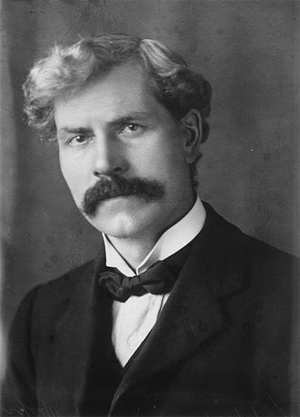

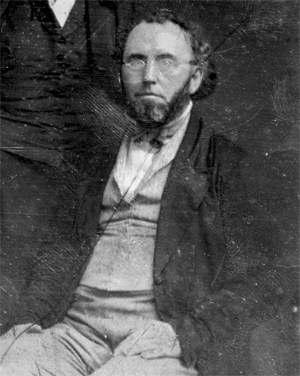

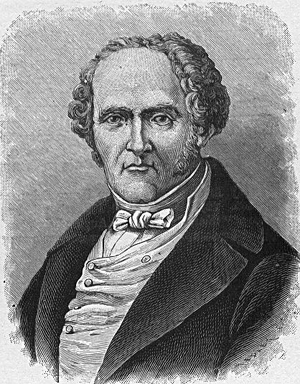

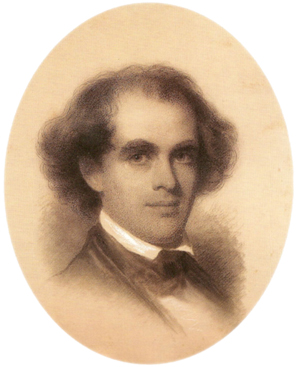

The “Young Folks Corner” retained its prominent role in each issue for the first three years but then disappeared for the remaining three. Besant’s contributions had pride of place during the first year, when she produced one legend (or its continuation) at the head of the department for each issue. She published her final legend, “The Story of Hypatia” (OC 3.1.55–59), at the outset of 1884, following it with a six-part serialization of the life of Giordano Bruno during the remainder of that year.25 Bruno’s biography appeared in tandem with those of the last three “Real Heroes” authored by Robertson; after Paine and Stephenson in the first volume, the next three volumes included multi-part biographies of Isaac Newton, John Milton, Benjamin Franklin, Galileo, Michael Faraday, and Martin Luther. Starting with the third volume, Hypatia Bradlaugh became a more frequent contributor to the journal as a whole, publishing not only biographies of Wendell Phillips and Alexander Kourbanoff but also articles like “Witches and Witchcraft” (September 1884) and short adult fiction. For the last three months of 1884, she provided the lead entry for the “Young Folks Corner” (“How the World Was Made,” stipulated as “translated from the Latin of P. Ovidius Naso”), and she held that lead position through the first nine months of 1885, producing a series of short stories and retelling some Russian fables. When the “Young Folks Corner” concluded its run at the end of 1885, its final entries included the four-part “Story of Garibaldi,” by Jessie Taylor. By then Besant had finished serializing her autobiography and was turning her attention to Ireland and Socialism, and both she and Hypatia had the satisfaction of collecting their legends and other stories for book publication by the Freethought Publishing Company.26

Besides featuring mythology, biography, fiction, and puzzles, the “Young Folks Corner” also sponsored a regular section during its first year entitled “Domestic Pets.” Usually written by E.D. Fryer, these entries conveyed both a scientific and humane attitude toward animals: the full roster included the guinea pig, the rat, the rabbit, the squirrel, the Scotch Terrier, dormice, and the St. Bernard (all but the latter two illustrated with a woodcut). Going back to Bradlaugh’s entry on bullfighting in the first issue, the journal had endorsed respect for the animal kingdom and an abhorrence of violence, but outside the realm of the “Young Folks Corner,” the second year witnessed a series with a different tenor. Entitled “Our Household Pests,” this series was entirely scientific and provided practical information about avoidance and extermination; this listing included the flea, the bug, the clothes’ moth, the housefly, the cricket, the spider, and the cockroach (again all but the latter two illustrated with a woodcut). After she became a Theosophist, Besant joined the ranks of the anti-vivisectionists, but during the secularist years that encompassed her tenure as editor of Our Corner, she is likely to have concurred with the opinions expressed by Robertson in his article, “The Ethics of Vivisection” (OC 6.2.84–94). After refuting Frances Cobbe’s viewpoints as expressed in “The Moral Aspects of Vivisection,” he asserts, “Those of us who have no fixed prejudice against legislation as such can see there is a good deal to be said for the present arrangement of licenses, which puts a check on mere experiments in torture and leaves a possibility of conscientious research” (90). Presumably, such legislation was not of the “grandmotherly” type.

By now it should be clear that the “Young Folks Corner” in particular had lent itself to being illustrated, and Besant began publication of Our Corner with generous instances of engravings, photograveures, and woodcuts throughout the journal. Portraits of biographical subjects that first year seemed to establish a standard, as did the various woodcuts for the legends, domestic pets, picture puzzles, and chess positions, but as the year wore on fewer and fewer illustrations appeared, and the last issue of 1883 did not have a single illustration. During the first half of the following year, the sole depictions were those accompanying scientific articles; never more than three or four figures per article, these illustrations were simple line drawings that could not have been expensive to reproduce. After that, only one more article—”A Southern Shell” (January 1885), with its pair of line drawings—merited pictorial accompaniment for the remainder of the journal’s publication. No longer including illustrations must have affected Besant’s original conception of the “Young Folks Corner,” and undoubtedly it also influenced her decision to bring her “Peeps though a Microscope” to a close. Moreover, the Socialistic program of the second half of her editorship called more for argument than vignette.

IV. Winding Down and Winding Up

In retrospect, it is not hard to recognize that Besant’s commitment to Our Corner was winding down in 1888. All “corners” (except for two installments of the “Art Corner”) disappeared from the journal’s final volume (its subtitle had been shortened to “A Monthly Magazine” at the beginning of the year), and Besant turned over a disproportionate number of its pages to the last six installments of Shaw’s novel Love Among the Artists. This shift in ratio suggests that she had recognized at least six months before the journal’s last issue that it might cease publication, and she would surely have wanted to see the novel through to completion (the June 1888 number barely acknowledges the “Art Corner” and “Publisher’s Corner” by burying them in the background of its cover design). As for the demise of the two “corners” associated with Bradlaugh and Besant, the first half of 1888 saw installments of Bradlaugh’s “Political Corner” only three times, while the “Publishers Corner” appeared in only four of six monthly numbers. By then the increasing role of Robertson as a reviewer would suggest that he was primarily in charge of the final entries about recent publications.

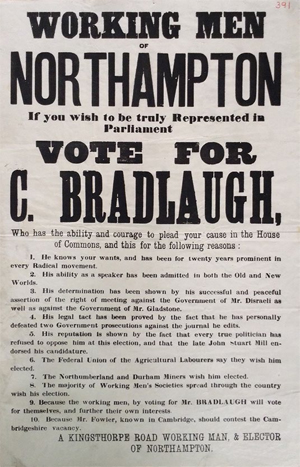

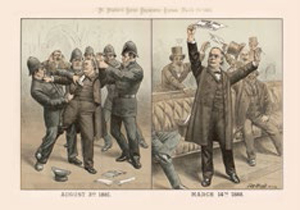

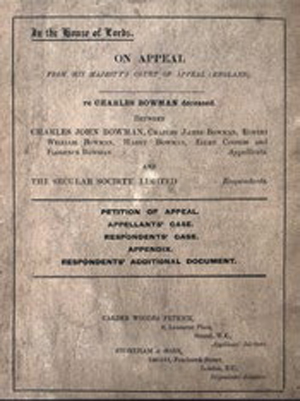

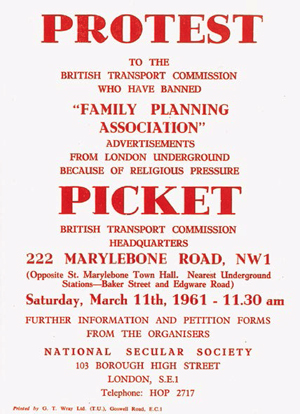

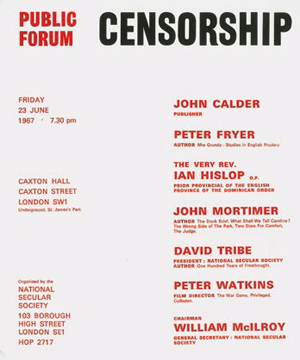

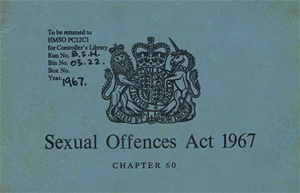

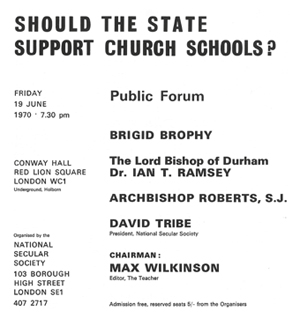

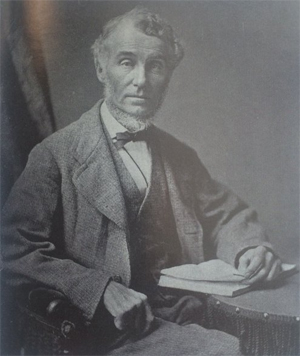

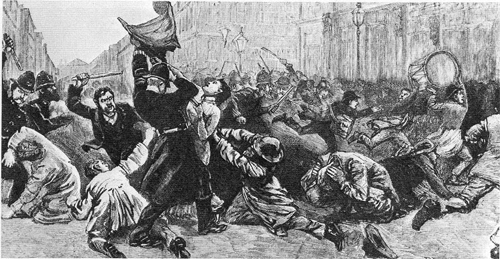

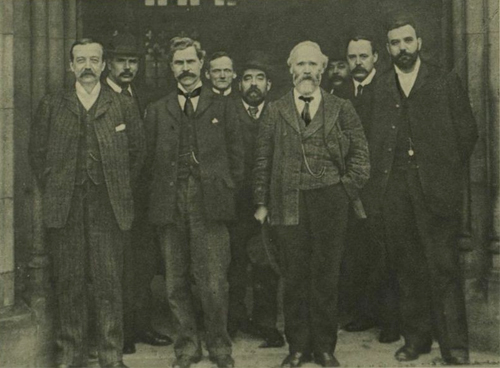

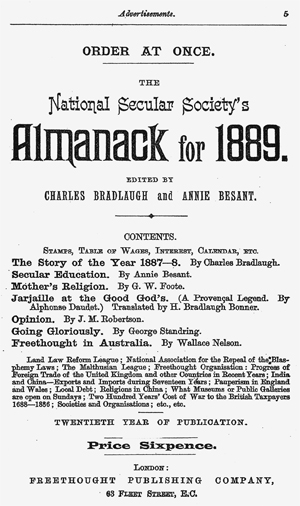

Bradlaugh’s withdrawal is hardly surprising, given his break with Besant over Socialism in general and her participation in the events leading to Bloody Sunday in particular. As head of the National Secular Society he had urged its membership to withdraw, while Besant’s leadership in the Social Democratic Foundation put her at the forefront of the demonstrations. (Nonetheless, they were still on public record in support of the National Secular Society at the end of 1888; for the advertisement for the NSS’s Almanack for 1889 in the final issue of Our Corner, see figure 8.) Prior to their printed exchange about Socialism in 1887, Bradlaugh had willingly argued his opposing position on the subject in a five-part article in 1884, and he continued to average eight or nine contributions to Our Corner per year in addition to his “Political Corner” up until 1888, when he submitted only two articles, one on “The Real High Tory Programme” and the other entitled “My Parliamentary Work This Session.” Throughout the run of Our Corner, Bradlaugh served as a watchdog on Parliament, and when he concluded his summary article, he could honestly attest, “I have taken part in most of the important debates, during the Session, my chief speeches having been made on Ireland and India, but several of importance have been made on questions affecting labor” (OC 12.4.196). Often called the “Member for India,” Bradlaugh wrote two articles on India for Our Corner, “India and the Ibert Bill” (February 1884) and “Our Empire in India” (August–September 1885). He shared Besant’s views on the deplorable conditions in Ireland, making their division over Bloody Sunday all the more painful—given that it had escalated from a demonstration against coercion in Ireland.27

Fig. 8: Advertisement for The National Secular Society’s Almanack for 1889 (Advertiser for vol. 12, December 1888)

ORDER AT ONCE.

The National Secular Society's

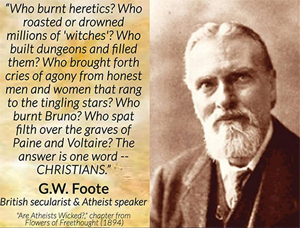

Almanack for 1889.

EDITED BY

CHARLES BRADLAUGH and ANNIE BESANT.

CONTENTS:

STAMPS, TABLE OF WAGES, INTEREST, CALENDAR, ETC.

The Story of the Year 1887-8. By Charles Bradlaugh.

Secular Education. By Annie Besant.

Mother's Religion. By G.W. Foote.

Jarjaille at the Good God's. (A Provencal Legend. By Alphonse Daudet.) Translated by H. Bradlaugh Bonner.

Opinion. By J.M. Robertson

Going Gloriously. By George Standring.

Freethought in Australia. By Wallace Nelson.

Land Law Reform League; National Association for the Repeal of the Blasphemy Laws; The Malthusian League; Freethought Organisation: Progress of Foreign Trade of the United Kingdom and other Countries in Recent Years; India and China -- exports and Imports during Seventeen Years; Pauperism in England and Wales; Local Debt; Religions in China; What Museums or Public Galleries are open on Sundays; Two Hundred Years' Cost of War to the British Taxpayers 1688-1886; Societies and Organisations; etc., etc.

TWENTIETH YEAR OF PUBLICATION.

Price Sixpence.

LONDON:

FREETHOUGHT PUBLISHING COMPANY,

63 FLEET STREET, E.C.

Bradlaugh’s last monthly contribution to Our Corner in October 1888 coincided as well with the timetable of Besant’s last entry. Entitled “Reaction and Education,” hers was a review of the report issued by the Commissioners appointed to inquire into the Elementary Education Acts for England and Wales, a fitting subject for the woman who was elected that year to a three-year term on the London School Board. Women had been permitted to stand for the London School Board since 1870, while 1888 marked the first year that they could vote in local elections. Appealing to the working class, Besant’s last article concluded on a fiery note: “The ‘middle class’ has the money, but the ‘lower class’ has the voting power, and it will indeed be shortsighted and foolish if, pending the great change which will make the workers and the nation synonyms, it does not use its voting strength to recover the use of some of the wealth which is ever being made by it and ever slipping from its hands” (OC 12.4.204). Educational reform, especially for women and girls, would remain at the forefront of Besant’s goals as she went on to address the problems faced by India in the twentieth century.28

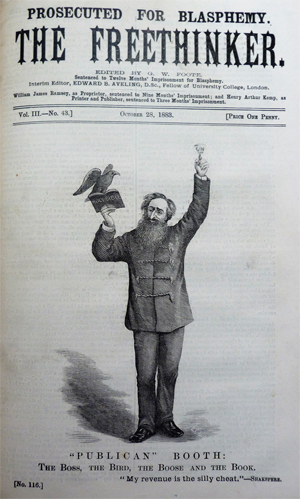

While the first four months of 1888 had witnessed publication of four articles authored by Besant, this review article was her sole contribution to the journal’s final volume. Five years later, in her post-Theosophical-conversion reassessment of her lifestory, An Autobiography, she wrote that Our Corner merely “served as a useful mouthpiece in my Socialist and Labour propagandist work” (286). This dismissive accounting of the value of Our Corner misrepresents its overall goals and accomplishments, but it does indicate the degree to which the journal had become an outlet for her political views and her frustration that her social initiatives were not resulting in immediate action. Like a number of other social visionaries of her day (Foote with both the Freethinker and Progress [1883–87] and William Morris with the Commonweal [1885–94] especially come to mind), Besant had needed the voice of her own periodical. And when neither it nor the Link fully sufficed for her aspirations, she was primed for the transformation that would occur when she acceded to the 1889 request of her coeditor, William Stead, that she review the two volumes of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine for his Pall Mall Gazette. Not only did Besant review Blavatsky’s tome for the Pall Mall Gazette (under the title “Among the Adepts” [23 April 1889]), but she also reviewed it for the National Reformer (this time as “The Evolution of the Universe” [23 June 1889]). In the interim, she wrote a two-part article for editor H.W. Massingham’s the Star entitled “Sic Itur ad Astr [thus do we reach the stars]; or, Why I Became a Theosophist” (May 1889), which acknowledged her membership in the Theosophical Society earlier that month. Seeing the proofs for this article reportedly caused Shaw to declare her “quite mad.”29

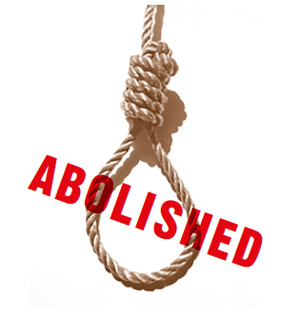

Annie Besant’s desire to foster intellectual growth and knowledge in others prompted her to seek out ingenious ways to break down boundaries between the liberal arts and sciences, to promote rationalism, and to champion Freethought. Her journal constituted an international platform as she utilized science, literature, comparative religion, and the tenets of Socialism to expose colonialism, imperialism, and fascism. From the outset, she evinced concern about conditions in Ireland. Proudly claiming her Irish heritage on the opening page of Autobiographical Sketches—”full three quarters of my blood are Irish” (OC 3.1.1)—she made it clear to her readership that exposure to anti-Irish sentiment via the mentorship of William P. Roberts, solicitor and trades-union advocate, was significant in first raising her political consciousness. As a young woman of twenty in the autumn of 1867, just a few months short of her marriage, she had stayed with Roberts and his family in Manchester immediately prior to his participation in the defense of the Fenian Five, which resulted in three public executions (OC 3.5.257–67). Our Corner became a forum where she could speak out against the land laws in Ireland that favored absentee English landlords, and in October of 1886 she initiated a column entitled “Evictions in Ireland”: “Outrages may come, and I am anxious that any whom I can influence may clearly understand the connextion between evictions and outrages, and may see how landlord oppression leads to peasant revenge” (OC 8.4.245). The following year she retitled the column “The War in Ireland,” regularly including editorial commentary and argument in addition to providing key statistics; these columns ran concurrent with the first six months of “Fabian and Socialist Notes.”30 Besant continued to be critical of the British Empire for the rest of her life, although her brand of independence for India favored its inclusion in the federation of former British colonies that constituted the Commonwealth.

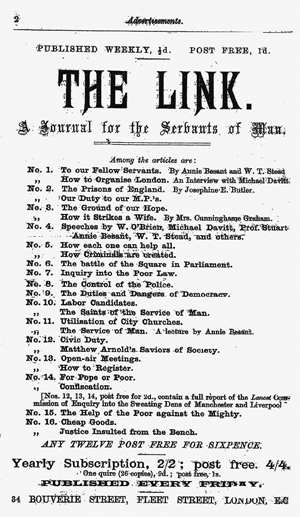

Fig. 9: Advertisement for The Link, co-edited by Annie Besant and W. T. Stead (Advertiser for vol. 11, June 1888)

PUBLISHED WEEKLY, 1/2d. POST FREE, 1d.

THE LINK.

A Journal for the Servants of Man.

Among the articles are:

No. 1. To our Fellow Servants. By Annie Besant and W.T. Stead.

No. 1. How to Organise London. An Interview with Michael Davitt.

No. 2. The Prisons of England. By Josephine E. Butler.

No. 2. Our Duty to our M.P.'s.

No. 3. The Ground of our Hope.

No. 3. How it Strikes a Wife. By Mrs. Cunninghame Graham.

No. 4. Speeches by W. O'Brien, Michael Davitt, Prof. Stuart, Annie Besant, W.T. Stead, and others.

No. 5. How each one can help all.

No. 5. How Criminals are created.

No. 6. The battle of the Square in Parliament.

No. 7. Inquiry into the Poor Law.

No. 8. The Control of the Police.

No. 9. The Duties and Dangers of Democracy.

No. 10. Labor Candidates.

No. 10. The Saints of the Service of Man.

No. 11. Utilisation of City Churches.

No. 11. The Service of Man. A lecutre by Annie Besant.

No. 12. Civic Duty.

No. 12. Matthew Arnold's Saviors of Society.

No. 13. Open-air Meetings.

No. 13. How to Register.

No. 14. For Pope or Poor.

No. 14. Confiscation.

[Nos. 12, 13, 14, post free for 2d., contain a full report of the Lancet Commission of Enquiry into the Sweating Dens of Manchester and Liverpool]

No. 15. The Help of the Poor against the Mighty.

No. 16. Cheap Goods.

No. 16. Justice Insulted from the Bench.

ANY TWELVE POST FREE FOR SIXPENCE.

Yearly Subscription, 2/2; post free. 4/4.

One quire (26 copies), 9d.; post free, 1s.

PUBLISHED EVERY FRIDAY.

34 BOUVERIE STREET, FLEET STREET, LONDON, E.C.

Introducing a recurring “Socialist Notes” section to Our Corner had made Besant’s radical Socialism more conspicuous, and she became much less in demand as a lecturer for the National Secular Society. Without the remuneration from her lectures, and because she eschewed the revenue she might have gleaned from external advertising, neither Our Corner nor the Link was solvent (for an example of how Besant advertised the Link in Our Corner, see figure 9). All along, Besant was unusual in paying her contributors up front, but now she was out of funds. Fellow Socialist Edward Carpenter reported that when he had submitted an article to Our Corner in July 1888, she replied, “[ b]efore accepting I must say that my poor Corner is on its last legs and is not able to pay contributors. I am out of pocket every month and have spent on it all I could spare.”31 When both Our Corner and the Link stopped publishing at the end of 1888, Besant found herself not working in an editorial capacity for any periodical publication for the first time in almost fifteen years. Invigorated by the experience of being at the helm of such a stalwart vehicle as Our Corner for six years, Annie Besant was nonetheless disheartened not to win over more adherents to the Socialist causes she espoused. Yet once she began to explore the promise of comparative religion—a topic unleashed during her editorship of Our Corner—she was poised to make the quantum leap to Theosophy the following year.

The University of Texas at Austin

_______________

Notes

1. Before the end of 1885, Autobiographical Sketches was republished in book form by the Freethought Publishing Company (London). This volume has long been out of print, but that omission has been rectified by the critical edition edited by Carol Hanbery MacKay (Petersborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2009); this edition also reproduces the cabinet photograph of Besant that appeared as frontispiece to the book edition. In 1893, four years after converting to Theosophy, Besant rewrote her lifestory as An Autobiography (London: T. Fisher Unwin), and the Theosophical Society has kept that volume in reprint ever since. In the interim, Besant penned one other selfaccounting, “1875 to 1891: An Autobiographical Fragment” (Theosophical Publishing Society), in an effort to reestablish a dialogue with her by then alienated Secularist constituency. Our Corner was issued in twelve volumes, with six numbers for each half of the calendar year; parenthetical citations within the body of the text refer to volume and issue number, followed by the designated pagination.

2. Journalist William Thomas Stead (1849–1912) had founded and edited the Northern Echo in 1871, and he assisted John Morley in editing the Pall Mall Gazette for three years before assuming its sole editorship (1883–90). Three years after co-founding the Link with Besant (see their co-authored article, “To Our Fellow Servants,” Link [4 Feb. 1888]), he published “A Character Sketch” of her in his own journal, in which he predicted that she would one day take her seat in the House of Commons alongside Mrs. Fawcett; see Review of Reviews 3 (Oct. 1891): 349–67; rpt. Adyar, Madras: The Theosophical Publishing House, 1946, 100 pp.

3. See Onslow, Women of the Press in Nineteenth-Century Britain (London: Macmillan, 2000), 216, and Coolsen’s History dissertation, “The Evolution of Selected Major English Socialist Periodicals, 1883–1889” (American University, 1973). In this respect, Deborah Mutch is correct not to include Our Corner in her recent book, English Socialist Periodicals, 1880–1900: A Reference Source (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005); she does, however, provide listings of Besant’s articles on Socialism in other journals, as well as citations to her various letters to the editor on the subject.

4. We can track this increased availability by way of the British Library Catalogue of Microfilm of Newspapers and Journals Sale for 1983–1984. For the two microform resources, see University Microfilms, Early British Periodicals Series (Ann Arbor: Xerox Company, 1979), reels 225–26; and Rare Radical and Labour Periodicals of Great Britain, Part II: Marxism and the Machine Age, 1867–1914 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Company, 1983), 2 reels. The entries for each volume are indexed according to title or department (the index is always found at the head of each volume, thus serving as a table of contents), but digital search mode would, of course, be ideal. Working toward this end, Google Books have recently digitalized several volumes from the originals at the New York Public Library and Princeton University Library. See standard descriptive listing no. 17,080 in John S. North (ed.), Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers and Periodicals, 1800–1900, phase 2, vol. 5 (University of Waterloo: North Waterloo Academic Press, 1997), 3661–63. For further information that is regularly updated, see The Nineteenth Century Index, online at <C19index.chadwyck. com/marketing/index.jsp>.

5. See Thompson, Socialists, Liberals, and Labour: The Struggle for London, 1885–1914 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967), 32. It is still possible, however, that some of the publication records for Our Corner exist among the Besant Papers, Theosophical Society, Adyar, India, and I am hopeful that further archival study will bring them to light.

6. This lecture first appeared in print as an article in the National Reformer in 1874; later that year, it was published as a freestanding pamphlet (12 pp.) by the National Secular Society; Watts republished it in 1877; and then in 1885, Besant and Bradlaugh reprinted it under the auspices of their Freethought Publishing Company. It is republished in its entirety in Appendix D of the Broadview edition of Autobiographical Sketches (330–40). Bradlaugh’s younger daughter Hypatia recalls his saying that it was the best speech he ever heard; see “Personal Reminiscences,” Bradlaugh Family Papers, Bishopsgate Institute, London.

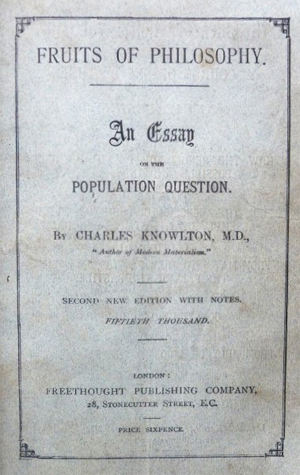

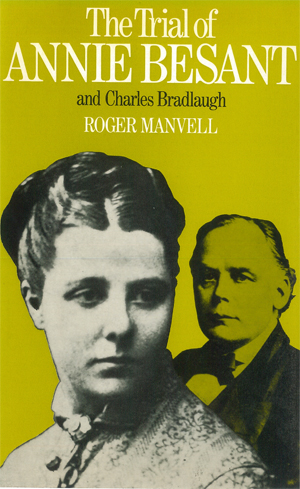

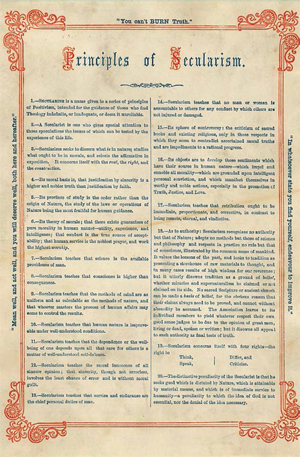

7. Bradlaugh and Besant republished American physician Charles Knowlton’s Fruits of Philosophy: The Private Companion of Young Married People (1832) as a test case of the English obscenity laws. Through their edition, now subtitled An Essay on the Population Question, they sought to establish the right to publish contraceptive information. For the circumstances surrounding the Knowlton Trial, as well as for the pertinent documentation authored by Besant, see S. Chandrasekhar, A Dirty, Filthy Book: The Writings of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant on Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control and an Account of the Bradlaugh-Besant Trial (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981). For the full transcript of the trial, see The Queen v. Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant (Specially Reported by the Queen’s Bench Division, June 18th, 1877), published by the Freethought Publishing Company immediately after its resolution.

8. The Married Woman’s Property Act of 1870 came too late to assist Besant in her effort to retain payment for her first publication. Her husband, the Reverend Frank Besant, immediately laid claim to the thirty shillings she earned from the short story entitled “Sunshine and Shade—A Tale Founded on Fact,” published under the initials of her maiden name (“A.W.”) in The Family Herald: A Domestic Magazine 26.300 (2 May 1868): 6–8.

9. Besides co-founding the Central Hindu College in Benares in 1898, Besant actively engaged in Indian politics and was elected the first female President of India’s National Congress in 1917. In 1914 she founded two newspapers in India, the weekly Commonweal and the daily New India. In general, Besant’s Indian biographers have been much less judgmental than Westerners in recounting her life; see, for example, C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar, Annie Besant (Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, 1963), as well as In Honour of Dr. Annie Besant: Lectures by Eminent Persons, 1952–1988 (Kamachha: Indian Section of the Theosophical Society, 1990).

10. The Freethought Publishing Company had previously printed Büchner’s freestanding pamphlet, The Influence of Heredity on Free Will, in 1880, and Besant published another article by him in 1886, “The Origin and Progress of Religion” (OC 7.1.14–21). See also Besant’s review of his Force and Matter (1855; trans. 1887; OC 10.1.39–44). Büchner’s last appearance in the pages of Our Corner occurred in 1887 with the publication of “Freethought and Philosophic Doctrines: Considerations on Spiritualism, Materialism, and Positivism.” Read for him at the London International Freethought Conference in a French translation by Dr. De Paepe, it concludes with the following question: “For to what purpose are the most subtly thought-out philosophical systems, if they do not put us in a position to add to the well-being and happiness of mankind?” (OC 10.4.218).

11. Although Besant had already begun to make G.W. Foote jealous because of her close association with Bradlaugh and her rapid rise within the ranks of the National Secular Society, her comments about his “barbed” Arrows of Freethought (London: H.A. Kemp) in this issue undoubtedly contributed to his animosity; she writes, “It always seems to me a sorry amusement to burlesque other people’s deities” (OC 1.1.51). The Freethought Publishing Company catalogue for 1904 lists 52 titles by Foote, including “Mrs. Besant’s Theosophy,” “The New Cagliostro” (an open letter to Blavatsky), and “Is Socialism Sound?” (his four-night debate with Besant). The Freethinker, founded in 1881 and edited by Foote, is still in print today; it is the longest running Freethought publication.

12. Named after the American abolitionist and liberal clergyman Moncure Conway (1832–1907), Conway Hall Humanist Centre in Red Lion Square (founded in 1929) is the present home of the Ethical Society, originally headquartered at South Place Chapel, Finsbury, London, where Conway served as minister before his conversion to humanistic Freethought. Its library houses the records of the National Secular Society, including a complete run of Our Corner; see also the ongoing publications of the Ethical Record and the National Secular Society Bulletin for occasional references to and articles about Besant. Other holdings of the NSS, most notably the Bradlaugh Papers, are on deposit at the Workingman’s Library, Bishopsgate. Conway Hall is currently the site of monthly meetings of The Shaw Society.

13. Joynes’s use of the masculine pronoun would continue to be reflected in the rhetoric of the Theosophical Society about “brotherhood” and the longterm future of “mankind.” Despite her feminism and her genuine support of women’s suffrage, Besant participated in this same rhetoric, although Joy Dixson makes an excellent case for Besant transcending gender considerations; see “Sexology and the Occult: Sexuality and Subjectivity in Theosophy’s New Age,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 7.3 (1997): 409–33. See also Robert Ellwood and Catherine Wessinger, “The Feminism of ‘Universal Brotherhood’: Women in the Theosophical Movement,” Women’s Leadership in Marginal Religions: Explorations Outside the Mainstream, ed. Wessinger (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 68–87, for elaboration of this topic.

14. Part of the rationale for the Broadview edition of Autobiographical Sketches has been to make available ready comparison of these two instances of self-writing; it is especially instructive to examine Besant’s first autobiographical undertaking in terms of selectivity and emphasis. Besant did not think that being a Theosophist and a Secularist (or, for that matter, a Socialist) were incompatible. The Freethought Publishing Company continued to list her “Why I Became a Theosophist” (1890), along with her cabinet photograph, while Bradlaugh was still alive, and after his death in 1891 many of their co-authored publications stayed on the roster. For an archive specific to Freethought, see the collection acquired in 1976 from Pickering & Chatto (London) by the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington IN (BL 2747; 11 boxes of circa 400 pamphlets, broadsheets, and other ephemera).

15. This “Notes” section is fronted by a full-page Fabian Society logo and motto, first introduced in the March 1886 issue of Our Corner (187–92); besides the cover designs, it is the sole interior pictorial representation— with the single exception noted in the upcoming discussion on illustrations— after June 1884. The section’s regular subdivisions are headed as follows: Basis (of Socialism), Aim, Methods, Branches (in London), England, Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, Spain, and America. Interestingly, the last four numbers of the journal no longer include any Socialist section.

16. Another popular debate—“Will Socialism Benefit the English People?”— had been conducted between Bradlaugh and Henry Mayers Hyndman, editor of Justice, on 17 April 1884 at St. James’s Hall; the verbatim record was printed two days later in Justice and then reprinted as a freestanding booklet by Arthur Bonner.

17. Strangely enough, the issue for April 1885 in which Besant launched Shaw’s career as a novelist is also the only one not to include an installment of her own Autobiographical Sketches during its year-and-a-half run. A brief entry in the National Reformer, undoubtedly written by Bradlaugh, announced that she was ill that month, thereby also explaining the hiatus of her regular NR column, “Day-break.”

18. The last of Shaw’s novels to be published, Immaturity (Constable, 1931), was actually the first written (in 1879). None of the publication dates of his novels followed the order of their writing, and in general they have been adjudged as failures. Most bibliographies do not acknowledge the first appearance of The Irrational Knot and Love Among the Artists in Our Corner, citing instead their first book publications, both occurring after the turn of the century.

19. Bradlaugh’s daughter was a prolific contributor to Our Corner, as will be noted in subsequent mention of her scientific and biographical articles as well as her tales for the “Young Folks Corner.” Her relations with Besant would always be delicate, however, as both she and her sister Alice resented the long hours Bradlaugh spent working with Besant. Hypatia married Freethought printer Arthur Bonner in mid-1885; later that autumn she published another article noteworthy for its feminist argument, “Anti-Slavery Women” (OC 6.3.167–70).

20. As Shaw’s successor, Mary Reed would remake the “Art Corner” into a forum for reviewing art gallery openings and discussing the reputation of painting worldwide. She also wrote an extended review of the play Ariane, about the still-controversial subject of divorce (OC 11.4.261–62). During the last six months of Our Corner, she came increasingly to the fore in her own right as a critic of the realistic school of painting; see especially her two independent articles, “Some Minor Variations in Realism” (OC 12.5.291– 95) and “Realism Once More” (OC 12.6.376–83). For more information featuring Reed’s and Cracknell’s contributions, see Virginia Clark, “The Freethought Lens: The Arts Commentaries in Annie Besant’s Our Corner, Her Freethought/Fabian Socialist Monthly, 1883–1886,” Journal of Freethought History 1.2 (2004): 1–4.

21. See also Besant’s review essay of August Bebel’s Women in the Past, Present, and Future (OC 6.2.94–98), as well as her article “The Economic Position of Women” (OC 10.2.95–99).

22. Aveling’s personal and financial affairs came under increased critical scrutiny by his former colleagues. While separated from his wife (whom he had deserted), he lived for over a decade with Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl Marx, and while Our Corner was still in publication, he co-authored two books with Eleanor, The Factory Hell (1885) and The Woman Question (1886). Upon his wife’s death in 1897, however, he married someone else, and shortly thereafter Eleanor committed suicide.

23. Already a frequent contributor to both the National Reformer and Our Corner, Robertson was persuaded by Besant to move from Edinburgh to London in 1884. Like Besant, he did not find Secularism and Socialism incompatible, although by the time he succeeded Bradlaugh to the editorship of NR, his Socialism had tempered. After Bradlaugh’s death, he assisted Hypatia Bonner with her publication of Charles Bradlaugh: A Record of His Life and Work by His Daughter, With an Account of His Parliamentary Struggle, Politics, and Teachings by John M. Robertson, 2 vols. (London: T.F. Unwin, 1895). His open mind made him less dismissive of Besant than many of his compatriots when she converted to Theosophy. He was elected to Parliament 1906–18.

24. Besant would have been dismayed to learn of Huxley’s participation in the debate about denying her right to pursue botany studies at the Benthamite Foundation. Although he acknowledged to Aveling that she “was once a student—and a very hard-working student of my class at South Kensington” (30 May 1883; Bradlaugh Papers), he later wrote to solicitor Henry Crompton, “I have no objection to her exclusion” (16 July 1883; private possession of Gustavo Duran); see citation to the latter quotation in David Tribe, President Charles Bradlaugh, M.P. (London: Elek Books, 1971), 359.

25. By telling the story of Hypatia, the Neo-Platonist scholar and martyr, Besant seemingly draws unsettling attention to Bradlaugh’s daughter of the same name. The conclusion of Besant’s biography of Bruno quotes his epitaph: “To know how to die in one’s century is to live for all centuries to come” (OC 4.3.185).

26. These two collections are Besant’s Legends and Tales (1885) and Hypatia’s Princess Vera and Other Stories (1886), both published as part of the Young Folks Library; if they had plans for extending the series, they did not come to fruition.

27. Throughout publication of Our Corner, Bradlaugh was clearly much appreciated and honored. For an unusual example of this recognition, see the (unacknowledged) acrostic poem that spells out his name in rather affectionate terms (OC 4.2.87). See also the article on Bradlaugh by S. Van Houten, Member of the Dutch Parliament, written for an entry in the series entitled “Contemporary Men of Note”: “A clear and firm foreign policy I have during the last few years only noticed in the Radical prints [press]” (OC 5.6.368). Even after Besant converted to Theosophy, they managed to retain a guarded friendship. For Besant, Bradlaugh would always hold a special place; of their first meeting, she later wrote, “As friends, not as strangers, we met—swift recognition, as it were, leaping from eye to eye” (Autobiography 137).

28. Besant was instrumental in leading the fight to create free public education, as well as to introduce the concept of free lunches for those who needed them. For a detailed discussion of her role on the London School Board, see Patricia Hollis, Ladies Elect: Women in English Local Government, 1865– 1914 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 110–22 especially. See also Besant, Education as a National Duty (1903) and The Education of Indian Girls (1904), both published by the Theosophical Publishing Company (London, Benares, and Adyar).

29. Long after the fact, Shaw recalls confronting Besant about the astonishing news that she had converted to Theosophy and being even more astounded by her jocular response: “She said she supposed that since she had, as a Theosophist, become a vegetarian, her mind may have been affected”; see “Annie Besant and the ‘Secret Doctrine,’” The Freethinker 67 (14 Dec. 1947): 450. They had become estranged over his failure to participate in the Trafalgar Square demonstrations, although she still contributed a chapter on “Industry under Socialism” for his edited collection, Fabian Essays in Socialism (London: Walter Scott, 1889), 150–69.

30. For an early example of how Besant recognized that the farmers in England constituted natural allies of the working class, see her article entitled “Landlords, Tenant Farmers, and Laborers” (National Reformer 1877; rpt. Freethought Publishing Company); see Appendix D of the 2009 edition of Autobiographical Sketches (344–52).

31. The article in question is Carpenter’s “Democracy” (OC 12.3.208–10). Besant’s letter to Carpenter is dated 7 July 1889; see the Carpenter Papers, City of Sheffield Central Library, MSS 386. I am indebted to Anne Taylor for drawing my attention to this correspondence; see Annie Besant: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), 220. Taylor also highlights Carpenter’s ‘more detached and generous assessment of [Besant’s] contribution” (183): “She helped to batter down the ruins of the stupefied old Anglican Church; she gave the general mind a wholesome shock on the Malthusian question; she dotted out clearly the main lines of the socialist movement” (Carpenter, My Days and Dreams [London: Allen & Unwin, 1916], 221). But neither Taylor nor Besant’s other substantive biographer, Arthur H. Nethercot, provides an impartial account of her life; note the mocking titles of his two-volume biography, The First Five Lives of Annie Besant and The Last Four Lives of Annie Besant (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960 and 1963).

Works Consulted

Beetham, Margaret. A Magazine of Her Own?: Domesticity and Desire in the Woman’s Magazine, 1800–1914. London: Routledge, 1996.

Brake, Laurel, and Julie F. Codell, eds. Encounters in the Victorian Press: Editors, Authors, Readers. London: Palgrave, 2005.

Brake, Laurel, Aled Jones, and Lionel Madden, eds. Investigating Victorian Journalism. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1990.

Brake, Laurel, Bill Bell and David Finkelstein, eds. Nineteenth-Century Media and the Construction of Identities. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2000.

Brown, Lucy. Victorian News and Newspapers. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985.

Cantor, Geoffrey, Gowan Dawson, Graeme Gooday, Richard Noakes, Sally Shuttlesworth, and Jonathan R. Topham. Science in the Nineteenth-Century Periodical: Reading the Magazine of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Fraser, Hilary, Stephanie Green, and Judith Johnston. Gender and the Victorian Periodical. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Harris, Janice. “Not Suffering and Not Still: Women Writers at the Cornhill Magazine, 1860–1900.” Modern Language Quarterly 47.4 (1986): 382–92.

Harris, Michael, and Alan Lee, eds. The Press in English Society from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries. London: Associated University Presses, 1986.

Hughes, Linda. “Turbulence in the ‘Golden Stream’: Chaos Theory and the Study of Periodicals.” Victorian Periodicals Review 22.3 (1989): 117–25.

King, Andrew, and John Plunkett, eds. Victorian Print Media: A Reader. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Lacey, Colin, and David Longman. The Press as Public Educator: Cultures of Understanding, Cultures of Ignorance. Luton: University of Luton Press, 1997.

MacKenzie, Norman and Jeanne. The First Fabians. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1977.

Madden, Lionel, and Diana Dixon. The Nineteenth-Century Periodical Press in Great Britain: A Bibliography of Modern Studies, 1901–1971. New York: Garland, 1975.

Palmegiano, E.M. “Mid-Victorian Periodicals and Careers for Women.” Journal of Newspaper and Periodical History 6.2 (1990): 15–19 .

Shattock, Joanne, and Michael Wolff, eds. The Victorian Periodical Press: Samplings and Soundings. Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1982.

Turner, Mark W. “Toward a Cultural Critique of Victorian Periodicals.” Studies in Newspaper and Periodical History. 1995 Annual. Ed. Michael Harris and Tom O’Malley. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995. 111–25.

Vann, J. Don, and Rosemary T. VanArsdel, eds. Victorian Periodicals: A Guide to Research. 2 vols. New York: Modern Language Association, 1978 and 1989.

Wiener, Joel H., ed. Innovators and Preachers: The Role of the Editor in Victorian England. Contributions to the Study of Mass Media and Communication, no. 5. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Wolff, Michael. “Charting the Golden Stream: Thoughts on a Directory of Victorian Periodicals.” Victorian Periodicals Newsletter no. 13 (1971): 23–38.