UNESCO

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/17/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

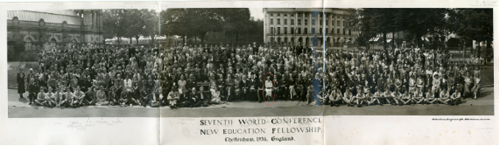

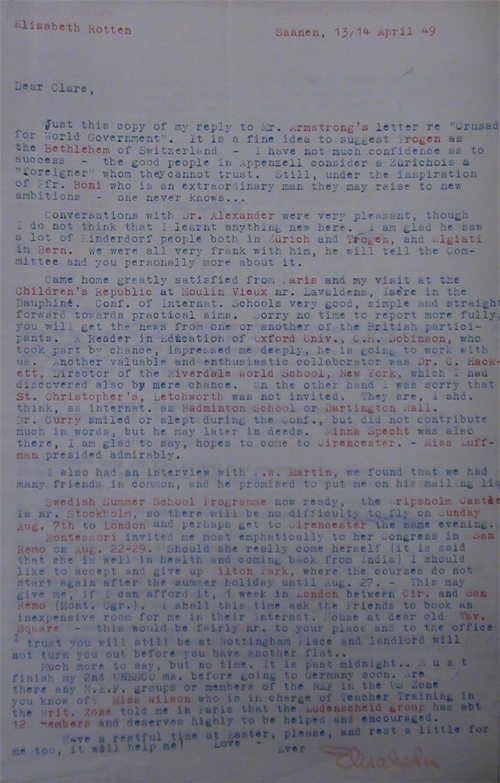

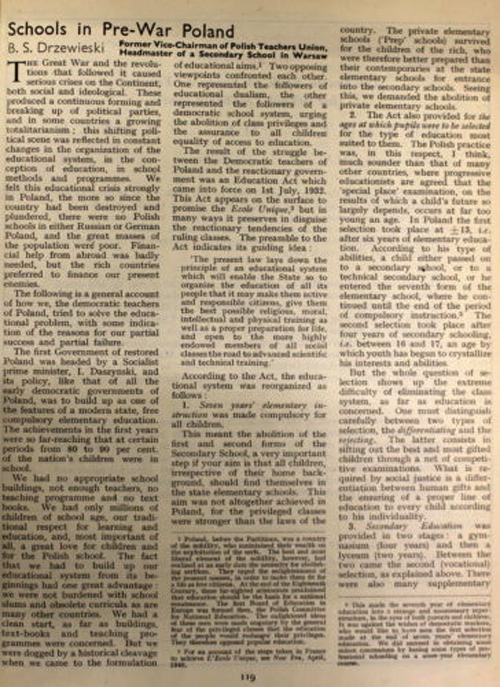

The N.E.F. [New Education Fellowship] and Unesco

Just as theosophy had a profound influence on the N.E.F. so the N.E.F. had a profound influence on the creation of UNESCO. It was described as "the midwife at the birth of UNESCO" (Kobayashi) and has been an NGO of UNESCO since 1966 (Hiroshi Iwama). It changed its name to W.E.F. [World Education Fellowship] that year.

-- Beatrice Ensor, by Wikipedia

UNESCO COLLECTION OF REPRESENTATIVE WORKS —INDIAN SERIES

This book [Vinaya Texts, Part III: The Kullavagga, IV-XII, Translated From the Pali by T.W. Rhys Davids and Hermann Oldenberg, 1885] has been accepted in the Indian Translation Series of the UNESCO collection of Representative Works, jointly sponsored by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), and the Government of India.

First published by the Oxford University Press, 1885

Reprinted by Motlal Banarsidass, 1965Rashtrapati Bhavan,

New Delhi-4

June 10, 1962

I am very glad to know that the Sacred Books of the East, published years ago by the Clarendon Press, Oxford, which have been out-of-print for a number of years, now be available to all students of religion and philosophy. The enterprise of the publishers is commendable and I hope the books will be widely read.

-- S. Radhakrishnan

PREFATORY NOTE TO THE NEW EDITION

Since 1948 the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ), upon the recommendation of the General Assembly of the United Nations, has been concerned with facilitating the translation of the works most representative of the culture of certain of its Member States, and, in particular, those of Asia.

One of the major difficulties confronting this programme is the lack of translators having both the qualifications and the time to undertake translations of the many outstanding books meriting publication. To help overcome this difficulty in part, UNESCO’s advisers in this field (a panel of experts convened every other year by the International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies), have recommended that many worthwhile translations published during the 19th century, and now impossible to find except in a limited number of libraries, should be brought back into print in low-priced editions, for the use of students and of the general public.The International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies (French: Conseil international de la philosophie et des sciences humaines; ICPHS/CIPSH) is a non-governmental organization within UNESCO. It embraces hundreds of learned societies in the field of philosophy, human sciences and related subjects.

CIPSH was founded at a first General Assembly held in January 1949 upon suggestion by Sir Julian Huxley, the first Director-General of UNESCO. The first president was Jacques Rueff. [The first general assembly of the International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies met in January 1949. A supporting organ for a multi-disciplinary and international vocation, CIPSH was conceived as the intermediary between UNESCO on one hand, and learned societies and national academies on the other. Its aim was to extend UNESCO's action in the domain of humanistic studies. Among its initial activities, in 1949, a first analysis of national-socialism was prefaced by CIPSH's first president, Jaques Rueff. This collective study had been prescribed in 1948 by the UNESCO General Conference, but had met with reticences about its publication.]

-- International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies, by Wikipedia

The experts also pointed out that in certain cases, even though there might be in existence more recent and more accurate translations endowed with a more modern apparatus of scholarship, a number of pioneer works of the greatest value and interest to students of Eastern religions also merited republication.

This point of view was warmly endorsed by the Indian National Academy of Letters (Sahitya Akademi), and the Indian National Commission for Unesco.

It is in the spirit of these recommendations that this work from the famous series "Sacred Books of the East”, is now once again being made available to the general public as part of the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works.

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

First, the man distinguished between eternal and perishable. Later he discovered within himself the germ of the Eternal. This discovery was an epoch in the history of the human mind and the East was the first to discover it.

To watch in the Sacred Books of the East the dawn of this religious consciousness of man, must always remain one of the most inspiring and hallowing sights in the whole history of the world. In order to have a solid foundation for a comparative study of the Religions of the East, we must have before all things, complete and thoroughly faithful translation of their Sacred Books in which some of the ancient sayings were preserved because they were so true and so striking that they could not be forgotten. They contained eternal truths, expressed for the first time in human language.

With profoundest reverence for Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, President of India, who inspired us for the task; our deep sense of gratitude for Dr. C. D. Deshmukh & Dr. D. S. Kothari, for encouraging assistance; esteemed appreciation of UNESCO for the warm endorsement of the cause; and finally with indebtedness to Dr. H. Rau, Director, Max Muller Bhawan, New Delhi, in procuring us the texts of the Series for reprint, we humbly conclude.

-- Vinaya Texts, Part III: The Kullavagga, IV-XII, Translated From the Pali by T.W. Rhys Davids and Hermann Oldenberg, 1885

German Economic Tradition

Hayek’s Critique of a Planned Economy

The most far-ranging critic of the German or Central European model of etatism [Total control of the state over individual citizens.] was Friedrich Hayek, an Austrian who mostly worked in the United Kingdom but toward the end of his life settled in Freiburg, in Southwestern Germany. He was largely without political influence until the 1970s. Hayek accurately identified that the interventionist approach of the Weimar Republic (which had its origins in wartime planning) created a sort of path dependency, in which the answer to failure was not an abandonment of the approach but rather a more radical version. In The Road to Serfdom, Friedrich Hayek asserted that Walter Rathenau, the intellectual who devised Germany’s innovative planning regime of World War I, “would have shuddered had he realised the consequences of his totalitarian economics” but nevertheless “deserves a considerable place in any fuller history of the growth of Nazi ideas. Through his writings he has probably, more than any other man, determined the economic views of the generation which grew up in Germany during and immediately after the last war; and some of his closest collaborators were later to form the backbone of the staff of Goering’s Five Year Plan [sic] administration.”6 Partial controls looked ineffective, so the Nazis wanted more extensive and radically enforced control. Rathenau’s major collaborator, Wichard von Moellendorff, formulated his view of a new communal economy, or Gemeinwirtschaft, provocatively and concisely: “Up to now in Germany the principle reined: free in economic matters, constrained in intellectual and spiritual affairs. The purpose of Gemeinwirtschaft is to turn that upside down.”7 In practice, however, the experience of interwar Germany showed that economic constraints also contributed to the erosion of intellectual, spiritual, and political freedoms.

A widespread response to the great financial crisis of 1931 was the imposition of capital controls, which brought the state further into the micromanagement of economic activity. Economic planning, as Hayek recognized, was inherently discriminatory: “It cannot tie itself down in advance to general and formal rules which prevent arbitrariness. . . . It must constantly decide questions which cannot be answered by formal principles only, and in making these decisions it must set up distinctions of merit between the needs of different people.”8 The issue of arbitrariness applies in a particular way to the actual implementation of capital controls. They were implemented in both Austria and Germany from 1931, that is, before the onset of the political dictatorship (Hitler came to power in January 1933, and Austrian conservatives created the reactionary corporate state, or Ständestaat, in 1934). But the dictatorship provided more means of enforcing controls. Hayek cites the German liberal thinker Wilhelm Röpke, to the effect that “while the last resort of a competitive economy is the bailiff, the ultimate sanction of the planned economy is the hangman.”9 Hayek might actually, if he had at the time known Hitler’s table talk, have cited the musings of the dictator himself: “Inflation does not arise when money enters circulation, but only when the individual demands more money for the same service. Here we must intervene. That is what I had to explain to Schacht [the president of the Nazi central bank], that the first cause of the stability of our currency is the concentration camp.”10

The decision on who should benefit from the allocation of foreign exchange became political and arbitrary. The institution invited a political process of rent-seeking, and it was those who could develop the closest contacts with the regime who benefited most. The allocation of scarce raw materials was in fact the basis of Nazi economic planning and also an initial instrument in the application of anti-Semitism: Jews were discriminated against as far as access to imports of raw materials, and their businesses suffered as a result.

Ordoliberalism

A softer version of the Hayekian critique of the old German tradition was deeply influential in Germany and had a major political impact. Known as Ordo-Liberalismus (or sometimes as the Freiburg School), and chiefly expounded by Röpke and Walter Eucken, it developed the emphasis on the state that was characteristic of the old German historical school, but altered the emphasis. According to the new doctrine, rules needed to be formulated in general terms and the state’s actions should be confined to the enforcement of such general laws, for instance, the laws on competition and against cartels, which had been an important part of the older German tradition of business management. Unlike Hayek, who more and more insisted on the spontaneous creation of order and rules, the Ordoliberals emphasized the need for an initial elaboration of an appropriate framework.

Their vision of order includes both a system of general rules and a mechanism by which those rules define the liability (or responsibility) of individuals, and of economic agents. The system fundamentally depends on the accountability of market participants. Any measure that limits accountability or responsibility by promising some sort of contingent rescue would create destructive incentives that would lead to the accumulation of unfulfillable expectations on behalf of the economic actors and unfulfillable liabilities on the part of the government as the ultimate insurer. As a consequence, Ordoliberals worried greatly about moral hazard, a term taken from insurance (a well-insured person may not take sufficient care that his house does not burn down). On these grounds, the Freiburg School and its modern successors even worry about the limited liability principle for corporations. “Unlimited liability is part of a competitive system,” Walter Eucken wrote. In his eyes, the problem was that the development of the legal system and the increased complexity of laws tend to subvert the liability principle: “Its destruction by legal policy endangers the functioning of this system.”11 So too many, and too complicated, laws would breed moral hazard, and the economic agents are given incentives to game the system.

The antitrust thinking of the new German economists also meshed well with the thinking of the US military administration. General Lucius Clay, the military governor, liked to sum up American goals for the postwar German order as the four Ds: denazification, demilitarization, democratization, and decartelization. The critical document for the initial postwar occupation policy, JCS 1067 of April 26, 1945, required the prohibition of “all cartels or other private business arrangements and cartel like organizations.”12 One of the German Ordoliberals, Franz Böhm, wrote that there was “no influential and socially strong group” supporting competition “excepting the American occupation authorities.”13

Competition law thus became a crucial part of the new German philosophy and, as advanced by Walter Hallstein, the German economist and civil servant who became the first president of the European Commission, also of European law. Ludwig Erhard, the economics minister who pushed Germany’s liberalization program, made the link between competition policy and European priorities explicit. In 1952, at the launching of the European Coal and Steel Community, he stated, “We plan to create a common European market. The aim is incompatible with a system of national or international cartels. If we want to create a higher standard of living through technical progress, rationalization, and an increase in production, we have to be against cartels.”14

The resulting vision did not completely remove the state. The Freiburg economists and also Erhard saw their ideal as a middle path between the extremes of an unregulated free market and unlimited state command, and some other economists, notably Alfred Müller-Armack, spoke of a social market economy (soziale Marktwirtschaft). Walter Eucken formulated the philosophy of the Freiburg School as follows: “A genuine, equitable, and smoothly functioning competitive system cannot in fact survive without a judicious moral and legal framework and without regular supervision of the conditions under which competition can take place pursuant to real efficiency principles. This presupposes mature economic discernment on the part of all responsible bodies and individuals and a strong impartial state.”15

The German position always remained somewhat ambivalent, and the middle way could oscillate. The rejection of the past was not as extreme as it appeared in some of the Ordoliberal manifestos. Indeed, the economic historian Albrecht Ritschl has argued (controversially) that a large part of the distinctively German and rather corporatist approach to the state-business relationship was inherited from the Nazi era.16

Ordoliberalism in Today’s Germany

In the 1960s, the German model incorporated a good deal of Keynesianism, reaching a high point in 1967 with the Law on Stability and Growth. But even the way that German Keynesianism was formulated in terms of a foundation of stability—or a rule-based order—was very characteristic of the German tradition. In addition, in academic economics, Ordoliberalism ceased to be the prevalent tradition and was largely replaced by a US-style neoclassical synthesis. There is virtually no serious academic economist who would today describe himself as an Ordoliberal (and indeed no female academic Ordoliberal); most modern Ordoliberal academics are lawyers rather than economists. Hans-Werner Sinn, one of Germany’s most publicly prominent economists, is often portrayed by outsiders as an extreme case of the German obsession with moral hazard issues, and at his retirement, the conservative Bavarian minister president Horst Seehofer celebrated him as a “Great Ordo-liberal” (which he distinguished from “narrow neo-liberals” and Milton Friedman’s “Chicago boys”); but Sinn himself instead tries to present himself as simply a classical economist.

Some Ordoliberalism survived in think tanks and in the economic research institutes that are a feature of the German intellectual landscape and constitute a bridge between academia and politics. In particular, the Hamburg Weltwirtschaftsinstitut and the Cologne Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft have been quite consistently Ordoliberal in outlook, while the Berlin German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) has long been Keynesian. The German Council of Economic Experts (Sachverständigenrat), which was set up by Ludwig Erhard in 1963, and which is intended to inform and educate the public rather than specifically to advise the government, often thinks of itself as emphasizing microeconomic foundations rather than macroeconomic interventionism and sees itself as embodying the legacy of Ordoliberalism.17 But in general, Ordoliberalism has a bad reputation, especially outside Germany, with the Financial Times journalist Wolfgang Münchau excoriating “the wacky economics of Germany’s parallel universe”: “German economists,” as he put it, “roughly fall into two groups: those that have not read Keynes, and those that have not understood Keynes.”18 It would indeed be peculiar if a whole country fell prey to a collective ideological imbecilism.

The traditions of the postwar era certainly exercise a substantial, almost subconscious, appeal to many Germans, and especially to German policy makers in the Bundesbank and perhaps also the Finance Ministry. It is also conspicuously represented in the economics pages of the major German newspaper the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ) and powerfully reinforced by the fundamentally even more liberal Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung. The FAZ is generally considered to be moderately right of center, but even the moderately left Süddeutsche Zeitung devotes space to the German economic tradition. In particular, since 2009, both these large German newspapers have worried about the moral hazard implications of euro rescue measures. Those traditions represent what Keynes famously called “the gradual encroachment of ideas” that rendered politicians and practical men as “slaves of some defunct economist.” As the Bundesbank had a major input in the design of the European monetary union, some commentators speak of the “Ordoliberalization of Europe.”19

But there is also something of a political pushback against the residues of Ordoliberalism. German officials in some Berlin ministries like to voice their dissent from alleged “fundamentalists” in the Bundesbank.20 The government also started to distance itself from the Council of Economic Advisers, complaining that the economists there were too dogmatic and inflexible and were looking “too much through German spectacles” and to taking into account the weakness of demand in peripheral Europe. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) economics minister Sigmar Gabriel pointedly delayed supporting the renomination of the chairman of the economic advisers, Christoph Schmidt. The council had provoked the government by criticizing many of the policies of the coalition government and demanding a return to more Erhard-style market-friendly policies. The SPD’s general secretary complained that the council was proceeding in an unscientific way.21

In the course of the euro debt crisis, German critics of the euro and the various rescue packages and measures liked to present themselves as the voice of the economics profession. “Economics professors” in Germany came to have a sort of ideological definition. They were the five professors who conducted a complaint against the Greek rescue package in 2009 (Wilhelm Hankel, Wilhelm Nölling, Karl Albrecht Schachtschneider, Dieter Spethmann, and Joachim Starbatty—only one of these was really an academic professor of economics, and he was retired).22 They were the 172 professors who in July 2012 signed a letter to the FAZ attacking the banking union plan.23 Or another group of five who together with other groups and with over 37,000 individual complainants organized by the Left Party in 2012 launched a constitutional complaint against ECB bond purchases.24 The phenomenon of economics professors even eventually appeared as a new political party: Bernd Lucke (an economics professor from Hamburg) and Konrad Adam (a retired FAZ journalist) formed an anti-euro protest party, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which polled surprisingly strongly in the European Parliament elections of 2014. These organized mobilizations of economics professors were not truly representative of the economics profession in Germany, but they wanted to give the impression that they were. Later, the economic professors were forced out of the AfD, which turned in a radical right direction.

Ordoliberalism in a European Context

The lineage from the Ordoliberals of the immediate postwar era to the modern politics of the euro does not only run in a solely German, or national, direction. Some of the background to the reversal of the German stance from etatism to an assertion of the liberal principles of economics occurred on a European level. One of the most interesting attempts to promote new economic thinking on a European level took place in Paris in August 1938. Twenty-six economists and other intellectuals, from all over Europe, had been summoned by the French philosopher Louis Rougier to discuss Walter Lippmann’s 1937 book The Good Society. In that book, Lippmann had defended political and economic liberalism in the face of a rising worldwide tide of illiberal antiparliamentary movements based on centralized economic planning: communism, fascism, National Socialism. The meeting included two figures who would be prominent in developing the German approach to Ordoliberalism, Wilhelm Röpke and Alexander Rüstow, although interestingly (and characteristically in the light of the historical moment) none of the participants were described as German: Rüstow was described as coming from Turkey, where he lived in exile, and Röpke as “école autrichienne, Austrian school,” along with Ludwig von Mises. Some of the most influential postwar French economic figures participated, Jacques Rueff, Raymond Aron, and Robert Marjolin.25

After 1945, the development of the European Union lends itself to the kind of analysis that the Ordoliberal school undertook immediately after World War II of the problem of the proliferation of rules and the tendency to augment or even replace general laws with particular decrees. Designed on Ordoliberal principles, as Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann recently pointed out, because of the need to observe rules in a federal setting, the European Union is vulnerable as a result of the ever more complex rules that after the financial crisis seem necessary to ensure its functioning.26 As Eucken warned, the elaboration of such detailed rules opens the way to the assertion of particular interests and the undermining of the collective project.

The elements of the German economic intellectual tradition can be summed up as follows:

1. A focus on the legal, moral, and political foundation of free markets in agreed rules, which may be treaties or laws or also common or shared understandings.27

2. A strong emphasis on responsibility and accountability. Participants in the market and those in the political process both have a responsibility. For market participants, the responsibility is a financial one—they need to pay the price of failure; politicians are accountable to voters. In short, as a Bundesbank official recently put it, those who have control and take risks also need to face the consequences of their actions.28

3. A concern with the potential for moral hazard arising out of lender of last resort activities. The IMF package for Mexico in 1994–5 was heavily criticized by German officials as encouraging reckless behavior on financial markets by increasing the likelihood of future rescue operations.

4. A concern that lender of last resort (LLR) action may corrupt or pollute monetary policy, because a central bank that has an LLR obligation might be force to give financial sector stability priority over price stability.

5. A belief that firm or binding rules are needed to shield monetary policy from fiscal dominance, namely, the view that government, by raising the permanent level of expenditures without at the same time raising taxes, can affect the current and future flows of the monetary base and, hence, of the money stock and of the inflation rate.29

6. A strict approach to government debt and to debt ceilings. Germany pioneered an approach that it now proposes to Europeanize, with a 2009 law mandating a deficit limit at the federal level of 0.35 percent of GDP by 2016 and an elimination of deficits for states by 2020. German think tanks like the idea of a Europeanization of fiscal rules enforced by some sort of fiscal or debt council.30

7. Growth is not achieved by the provision of additional money or resources but by structural reforms.31 Additional money is a sort of trickery, doomed to failure, and analogous to trying to pull yourself out of a swamp by pulling on your bootstraps.

8. A belief that present virtue—or austerity—is rewarded by future benefits.

French Economic Tradition

France too began the postwar era by rejecting the economic orthodoxies of its past and by seeking to Europeanize its new priorities. The economist and economic historian Alfred Sauvy characterized the old economics, which emphasized the limitations on government action, as contributing to “Malthusianism,” low growth and stagnation. Low growth and stagnation had weakened France politically, socially, and also militarily. The obsession with balanced budgets had led to a cutting of defense expenditures that made France more vulnerable. The architect of the “super-deflation” of the 1930s, Pierre Laval, was also the man who after 1940 went furthest in the political compromise with Hitler. Malthusianism thus was held to bear the ultimate responsibility for the military collapse of 1940 and the end of the French Republic.

Part of the Malthusian picture had been French unwillingness to take John Maynard Keynes seriously. Keynes was not a popular figure in France, doubtless because of his well-known criticism of the 1919 Versailles Treaty, and in pre-1940 French debates, the role of the state was not seen primarily in terms of macroeconomic stimulus. The new postwar French alternative to Malthusianism particularly emphasized the need for the state to coordinate and plan investment. An unplanned or spontaneous market order was likely to lead to underinvestment and low growth. There was thus a need for planisme.

The new concern always sat uneasily with many of the views of the most prominent French economists. Jacques Rueff had gone to London with General de Gaulle but remained an advocate of an enlightened liberalism as well as of monetary orthodoxy: he pleaded continually for a version of the gold standard. The later Nobel Prize laureate Maurice Allais made his reputation with a 1943 book, A la Recherche d’une Discipline Economique. L’Economie Pure, in which he sought to find a solution to “the fundamental problem of any economy”: how to promote the greatest feasible economic efficiency while ensuring a distribution of income that would be generally acceptable. Though it is sometimes claimed that Allais’s approach to capital and time preference laid the foundations for subsequent planning, he always considered himself an economic liberal. He attended the first meeting of the Mont Pélerin Society in 1947, and though he refused to sign the Statement of Aims, he wrote to Hayek that he wished to express his “profound agreement with economic and political liberty.” His dissent was based on the view that land should be held as national property: in every other respect, he was a classical liberal.32

-- Chapter 3: Historical Roots of German-French Differences, from The Euro and the Battle of Ideas, by Markus K. Brunnermeier, Harold James & Jean-Pierre Landau, 2016

UNESCO

Abbreviation UNESCO

Formation 4 November 1946; 72 years ago

Type United Nations specialised agency

Legal status Active

Headquarters Paris, France

Head

Director-General

Audrey Azoulay

Parent organization

United Nations Economic and Social Council

Website http://www.unesco.org

UN emblem blue.svg United Nations portal

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO[1]; French: Organisation des Nations unies pour l'éducation, la science et la culture) is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) based in Paris. Its declared purpose is to contribute to promoting international collaboration in education, sciences, and culture in order to increase universal respect for justice, the rule of law, and human rights along with fundamental freedom proclaimed in the United Nations Charter.[2] It is the successor of the League of Nations' International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation.[3]

UNESCO has 193 member states and 11 associate members.[4] Most of its field offices are "cluster" offices covering three or more countries; national and regional offices also exist.

UNESCO pursues its objectives through five major programs: education, natural sciences, social/human sciences, culture and communication/information. Projects sponsored by UNESCO include literacy, technical, and teacher-training programs, international science programs, the promotion of independent media and freedom of the press, regional and cultural history projects, the promotion of cultural diversity, translations of world literature, international cooperation agreements to secure the world's cultural and natural heritage (World Heritage Sites) and to preserve human rights, and attempts to bridge the worldwide digital divide. It is also a member of the United Nations Development Group.[5]

UNESCO's aim is "to contribute to the building of peace, the eradication of poverty, sustainable development and intercultural dialogue through education, the sciences, culture, communication and information".[6] Other priorities of the organization include attaining quality Education For All and lifelong learning, addressing emerging social and ethical challenges, fostering cultural diversity, a culture of peace and building inclusive knowledge societies through information and communication.[7]

The broad goals and objectives of the international community—as set out in the internationally agreed development goals, including the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)—underpin all UNESCO strategies and activities.

History

Flag of UNESCO

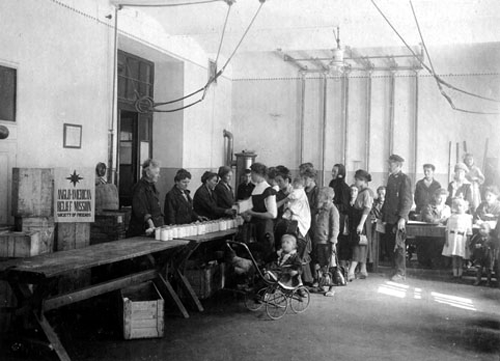

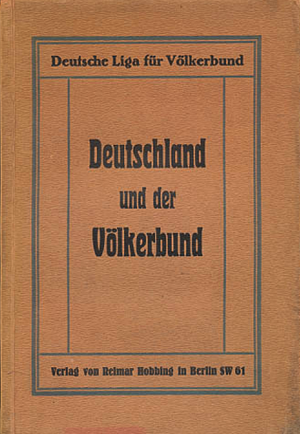

UNESCO and its mandate for international cooperation can be traced back to a League of Nations resolution on 21 September 1921, to elect a Commission to study feasibility.[8][9] This new body, the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (ICIC) was indeed created in 1922. On 18 December 1925, the International Bureau of Education (IBE) began work as a non-governmental organization in the service of international educational development.[10] However, the onset of World War II largely interrupted the work of these predecessor organizations.

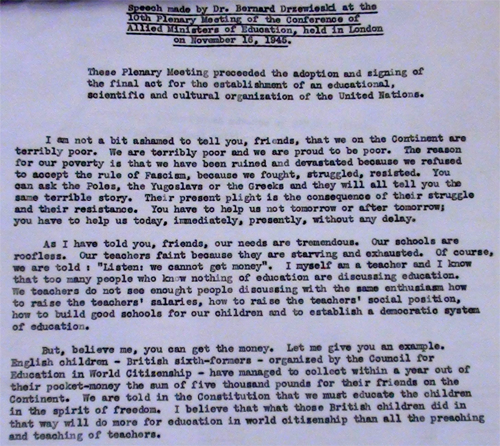

After the signing of the Atlantic Charter and the Declaration of the United Nations, the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME) began meetings in London which continued from 16 November 1942 to 5 December 1945. On 30 October 1943, the necessity for an international organization was expressed in the Moscow Declaration, agreed upon by China, the United Kingdom, the United States and the USSR. This was followed by the Dumbarton Oaks Conference proposals of 9 October 1944. Upon the proposal of CAME and in accordance with the recommendations of the United Nations Conference on International Organization (UNCIO), held in San Francisco in April–June 1945, a United Nations Conference for the establishment of an educational and cultural organization (ECO/CONF) was convened in London 1–16 November 1945 with 44 governments represented. The idea of UNESCO was largely developed by Rab Butler, the Minister of Education for the United Kingdom, who had a great deal of influence in its development.[11] At the ECO/CONF, the Constitution of UNESCO was introduced and signed by 37 countries, and a Preparatory Commission was established.[12] The Preparatory Commission operated between 16 November 1945, and 4 November 1946—the date when UNESCO's Constitution came into force with the deposit of the twentieth ratification by a member state.[13]

The first General Conference took place from 19 November to 10 December 1946, and elected Dr. Julian Huxley to Director-General.[14] The Constitution was amended in November 1954 when the General Conference resolved that members of the Executive Board would be representatives of the governments of the States of which they are nationals and would not, as before, act in their personal capacity.[15] This change in governance distinguished UNESCO from its predecessor, the ICIC, in how member states would work together in the organization's fields of competence. As member states worked together over time to realize UNESCO's mandate, political and historical factors have shaped the organization's operations in particular during the Cold War, the decolonization process, and the dissolution of the USSR.

Among the major achievements of the organization is its work against racism, for example through influential statements on race starting with a declaration of anthropologists (among them was Claude Lévi-Strauss) and other scientists in 1950[16] and concluding with the 1978 Declaration on Race and Racial Prejudice.[17] In 1956, the Republic of South Africa withdrew from UNESCO saying that some of the organization's publications amounted to "interference" in the country's "racial problems."[18] South Africa rejoined the organization in 1994 under the leadership of Nelson Mandela.

UNESCO's early work in the field of education included the pilot project on fundamental education in the Marbial Valley, Haiti, started in 1947.[19] This project was followed by expert missions to other countries, including, for example, a mission to Afghanistan in 1949.[20] In 1948, UNESCO recommended that Member States should make free primary education compulsory and universal.[21] In 1990, the World Conference on Education for All, in Jomtien, Thailand, launched a global movement to provide basic education for all children, youths and adults.[22] Ten years later, the 2000 World Education Forum held in Dakar, Senegal, led member governments to commit to achieving basic education for all by 2015.[23]

UNESCO's early activities in culture included, for example, the Nubia Campaign, launched in 1960.[24] The purpose of the campaign was to move the Great Temple of Abu Simbel to keep it from being swamped by the Nile after construction of the Aswan Dam. During the 20-year campaign, 22 monuments and architectural complexes were relocated. This was the first and largest in a series of campaigns including Mohenjo-daro (Pakistan), Fes (Morocco), Kathmandu (Nepal), Borobudur (Indonesia) and the Acropolis (Greece). The organization's work on heritage led to the adoption, in 1972, of the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage.[25] The World Heritage Committee was established in 1976 and the first sites inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1978.[26] Since then important legal instruments on cultural heritage and diversity have been adopted by UNESCO member states in 2003 (Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage[27]) and 2005 (Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions[28]).

An intergovernmental meeting of UNESCO in Paris in December 1951 led to the creation of the European Council for Nuclear Research, which was responsible for establishing the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)[29] later on, in 1954.

Arid Zone programming, 1948–1966, is another example of an early major UNESCO project in the field of natural sciences.[30] In 1968, UNESCO organized the first intergovernmental conference aimed at reconciling the environment and development, a problem which continues to be addressed in the field of sustainable development. The main outcome of the 1968 conference was the creation of UNESCO's Man and the Biosphere Programme.[31]

In the field of communication, the "free flow of ideas by word and image" has been in UNESCO's constitution from its beginnings, following the experience of the Second World War when control of information was a factor in indoctrinating populations for aggression.[32] In the years immediately following World War II, efforts were concentrated on reconstruction and on the identification of needs for means of mass communication around the world. UNESCO started organizing training and education for journalists in the 1950s.[33] In response to calls for a "New World Information and Communication Order" in the late 1970s, UNESCO established the International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems,[34] which produced the 1980 MacBride report (named after the Chair of the Commission, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate Seán MacBride).[35] The same year, UNESCO created the International Programme for the Development of Communication (IPDC), a multilateral forum designed to promote media development in developing countries.[36][37] In 1991, UNESCO's General Conference endorsed the Windhoek Declaration on media independence and pluralism, which led the UN General Assembly to declare the date of its adoption, 3 May, as World Press Freedom Day.[38] Since 1997, UNESCO has awarded the UNESCO / Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize every 3 May. In the lead up to the World Summit on the Information Society in 2003 (Geneva) and 2005 (Tunis), UNESCO introduced the Information for All Programme.

UNESCO admitted Palestine as a member in 2011.[39][40] Laws passed in the United States in 1990 and 1994 mean that it cannot contribute financially to any UN organisation that accepts Palestine as a full member.[41] As a result, it withdrew its funding which accounted for about 22% of UNESCO's budget.[42] Israel also reacted to Palestine's admittance to UNESCO by freezing Israeli payments to the UNESCO and imposing sanctions to the Palestinian Authority,[43] stating that Palestine's admittance would be detrimental "to potential peace talks".[44] Two years after they stopped paying their dues to UNESCO, US and Israel lost UNESCO voting rights in 2013 without losing the right to be elected; thus, the US was elected as a member of the Executive Board for the period 2016–19.[45]

Activities

UNESCO offices in Brasília

UNESCO implements its activities through the five programme areas: education, natural sciences, social and human sciences, culture, and communication and information.

• Education: UNESCO supports research in comparative education; and provide expertise and fosters partnerships to strengthen national educational leadership and the capacity of countries to offer quality education for all. This includes the

o UNESCO Chairs, an international network of 644 UNESCO Chairs, involving over 770 institutions in 126 countries

o Environmental Conservation Organisation

o Convention against Discrimination in Education adopted in 1960

o Organization of the International Conference on Adult Education (CONFINTEA) in an interval of 12 years

o Publication of the Education for All Global Monitoring Report

o Publication of the Four Pillars of Learning seminal document

o UNESCO ASPNet, an international network of 8,000 schools in 170 countries

UNESCO does not accredit institutions of higher learning.[46]

• UNESCO also issues public statements to educate the public:

o Seville Statement on Violence: A statement adopted by UNESCO in 1989 to refute the notion that humans are biologically predisposed to organised violence.

• Designating projects and places of cultural and scientific significance, such as:

o Global Geoparks Network

o Biosphere reserves, through the Programme on Man and the Biosphere (MAB), since 1971

o City of Literature; in 2007, the first city to be given this title was Edinburgh, the site of Scotland's first circulating library.[47] In 2008, Iowa City, Iowa became the City of Literature.

o Endangered languages and linguistic diversity projects

o Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity

o Memory of the World International Register, since 1997

o Water resources management, through the International Hydrological Programme (IHP), since 1965

o World Heritage Sites

o World Digital Library

• Encouraging the "free flow of ideas by images and words" by:

o Promoting freedom of expression, including freedom of the press and freedom of information legislation, through the Division of Freedom of Expression and Media Development,[48] including the International Programme for the Development of Communication[49]

o Promoting the safety of journalists and combatting impunity for those who attack them,[50] through coordination of the UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity[51]

o Promoting universal access to and preservation of information and open solutions for sustainable development through the Knowledge Societies Division,[52]including the Memory of the World Programme[53] and Information for All Programme[54]

o Promoting pluralism, gender equality and cultural diversity in the media

o Promoting Internet Universality and its principles, that the Internet should be (I) human Rights-based, (ii) Open, (iii) Accessible to all, and (iv) nurtured by Multi-stakeholder participation (summarized as the acronym R.O.A.M.)[55]

o Generating knowledge through publications such as World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development,[56] the UNESCO Series on Internet Freedom,[57] and the Media Development Indicators,[58] as well as other indicator-based studies.

• Promoting events, such as:

o International Decade for the Promotion of a Culture of Peace and Non-Violence for the Children of the World: 2001–2010, proclaimed by the UN in 1998

o World Press Freedom Day, 3 May each year, to promote freedom of expression and freedom of the press as a basic human right and as crucial components of any healthy, democratic and free society.

o Criança Esperança in Brazil, in partnership with Rede Globo, to raise funds for community-based projects that foster social integration and violence prevention.

o International Literacy Day

o International Year for the Culture of Peace

o Health Education for Behavior Change program in partnership with the Ministry of Education of Kenya which was financially supported by the Government of Azerbaijan to promote health education among 10-19-year-old young people who live in informal camp in Kibera, Nairobi. The project was carried out between September 2014 - December 2016.[59]

• Founding and funding projects, such as:

o Migration Museums Initiative: Promoting the establishment of museums for cultural dialogue with migrant populations.[60]

o UNESCO-CEPES, the European Centre for Higher Education: established in 1972 in Bucharest, Romania, as a de-centralized office to promote international co-operation in higher education in Europe as well as Canada, USA and Israel. Higher Education in Europe is its official journal.

o Free Software Directory: since 1998 UNESCO and the Free Software Foundation have jointly funded this project cataloguing free software.

o FRESH Focussing Resources on Effective School Health.[61]

o OANA, Organization of Asia-Pacific News Agencies

o International Council of Science

o UNESCO Goodwill Ambassadors

o ASOMPS, Asian Symposium on Medicinal Plants and Spices, a series of scientific conferences held in Asia

o Botany 2000, a programme supporting taxonomy, and biological and cultural diversity of medicinal and ornamental plants, and their protection against environmental pollution

o The UNESCO Collection of Representative Works, translating works of world literature both to and from multiple languages, from 1948 to 2005

o GoUNESCO, an umbrella of initiatives to make heritage fun supported by UNESCO, New Delhi Office[62]

The UNESCO transparency portal has been designed to enable public access to information regarding Organization's activities, such as its aggregate budget for a biennium, as well as links to relevant programmatic and financial documents. These two distinct sets of information are published on the IATI registry, respectively based on the IATI Activity Standard and the IATI Organization Standard.

There have been proposals to establish two new UNESCO lists. The first proposed list will focus on movable cultural heritage such as artifacts, paintings, and biofacts. The list may include cultural objects, such as the Jōmon Venus of Japan, the Mona Lisa of France, the Gebel el-Arak Knife of Egypt, The Ninth Wave of Russia, the Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük of Turkey, the David (Michelangelo) of Italy, the Mathura Herakles of India, the Manunggul Jar of the Philippines, the Crown of Baekje of South Korea, The Hay Wain of the United Kingdom and the Benin Bronzes of Nigeria. The second proposed list will focus on the world's living species, such as the Komodo Dragon of Indonesia, the Panda of China, the Bald eagle of North American countries, the Aye-aye of Madagascar, the Asiatic Lion of India, the Kakapo of New Zealand, and the Mountain tapir of Colombia, Ecuador and Peru.[63][64]

Media

UNESCO and its specialized institutions issue a number of magazines.

The UNESCO Courier magazine states its mission to "promote UNESCO's ideals, maintain a platform for the dialogue between cultures and provide a forum for international debate." Since March 2006 it is available online, with limited printed issues. Its articles express the opinions of the authors which are not necessarily the opinions of UNESCO. There was a hiatus in publishing between 2012 and 2017.[65]

In 1950, UNESCO initiated the quarterly review Impact of Science on Society (also known as Impact) to discuss the influence of science on society. The journal ceased publication in 1992.[66] UNESCO also published Museum International Quarterly from the year 1948.

Official UNESCO NGOs

UNESCO has official relations with 322 international non-governmental organizations (NGOs).[67] Most of these are what UNESCO calls "operational"; a select few are "formal".[68] The highest form of affiliation to UNESCO is "formal associate", and the 22 NGOs[69] with formal associate (ASC) relations occupying offices at UNESCO are:

Abbr / Organization

IB International Baccalaureate

CCIVS Co-ordinating Committee for International Voluntary Service

EI Education International

IAU International Association of Universities

IFTC International Council for Film, Television and Audiovisual Communication

ICPHS International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies which publishes Diogenes

ICSU International Council for Science

ICOM International Council of Museums

ICSSPE International Council of Sport Science and Physical Education

ICA International Council on Archives

ICOMOS International Council on Monuments and Sites

IFJ International Federation of Journalists

IFLA International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

IFPA International Federation of Poetry Associations

IMC International Music Council

IPA International Police Association

INSULA International Scientific Council for Island Development

ISSC International Social Science Council

ITI International Theatre Institute

IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources

IUTAO International Union of Technical Associations and Organizations

UIA Union of International Associations

WAN World Association of Newspapers

WFEO World Federation of Engineering Organizations

WFUCA World Federation of UNESCO Clubs, Centres and Associations

UNESCO Institute for Water Education in Delft

Institutes and centres

The institutes are specialized departments of the organization that support UNESCO's programme, providing specialized support for cluster and national offices.

Abbr / Name / Location

IBE International Bureau of Education Geneva[70]

UIL UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning Hamburg[71]

IIEP UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning Paris (headquarters) and Buenos Aires and Dakar (regional offices)[72]

IITE UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education Moscow[73]

IICBA UNESCO International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa Addis Ababa[74]

IESALC UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean Caracas[75]

UNESCO-UNEVOC UNESCO-UNEVOC International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training Bonn[76]

UNESCO-IHE UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education Delft[77]

ICTP International Centre for Theoretical Physics Trieste[78]

UIS UNESCO Institute for Statistics Montreal[79]

Prizes

UNESCO awards 22 prizes[80] in education, science, culture and peace:

• Félix Houphouët-Boigny Peace Prize

• L'Oréal-UNESCO Awards for Women in Science

• UNESCO/King Sejong Literacy Prize

• UNESCO/Confucius Prize for Literacy

• UNESCO/Emir Jaber al-Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah Prize to promote Quality Education for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities

• UNESCO King Hamad Bin Isa Al-Khalifa Prize for the Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Education

• UNESCO/Hamdan Bin Rashid Al-Maktoum Prize for Outstanding Practice and Performance in Enhancing the Effectiveness of Teachers

• UNESCO/Kalinga Prize for the Popularization of Science

• UNESCO/Institut Pasteur Medal for an outstanding contribution to the development of scientific knowledge that has a beneficial impact on human health

• UNESCO/Sultan Qaboos Prize for Environmental Preservation

• Great Man-Made River International Water Prize for Water Resources in Arid Zones presented by UNESCO (title to be reconsidered)

• Michel Batisse Award for Biosphere Reserve Management

• UNESCO/Bilbao Prize for the Promotion of a Culture of Human Rights

• UNESCO Prize for Peace Education

• UNESCO-Madanjeet Singh Prize for the Promotion of Tolerance and Non-Violence

• UNESCO/International José Martí Prize

• UNESCO/Avicenna Prize for Ethics in Science

• UNESCO/Juan Bosch Prize for the Promotion of Social Science Research in Latin America and the Caribbean

• Sharjah Prize for Arab Culture

• Melina Mercouri International Prize for the Safeguarding and Management of Cultural Landscapes (UNESCO-Greece)

• IPDC-UNESCO Prize for Rural Communication

• UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize

• UNESCO/Jikji Memory of the World Prize

• UNESCO-Equatorial Guinea International Prize for Research in the Life Sciences

• Carlos J. Finlay Prize for Microbiology

Inactive prizes

• International Simón Bolívar Prize (inactive since 2004)

• UNESCO Prize for Human Rights Education

• UNESCO/Obiang Nguema Mbasogo International Prize for Research in the Life Sciences (inactive since 2010)

• UNESCO Prize for the Promotion of the Arts

International Days observed at UNESCO

International Days observed at UNESCO is provided in the table given below[81]

Date / Name

27 January International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust

13 February World Radio Day

21 February International Mother Language Day

8 March International Women's Day

20 March International Francophonie Day

21 March International Day of Nowruz

21 March World Poetry Day

21 March International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

22 March World Day for Water

23 April World Book and Copyright Day

30 April International Jazz Day

3 May World Press Freedom Day

21 May World Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development

22 May International Day for Biological Diversity

25 May Africa Day / Africa Week

5 June World Environment Day

8 June World Oceans Day

17 June World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought

9 August International Day of the World's Indigenous People

12 August International Youth Day

23 August International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition

8 September International Literacy Day

15 September International Day of Democracy

21 September International Day of Peace

28 September International Day for the Universal Access to Information

2 October International Day of Non-Violence

5 October World Teachers' Day

2nd Wednesday in October International Day for Disaster Reduction

17 October International Day for the Eradication of Poverty

20 October World Statistics Day

27 October World Day for Audiovisual Heritage

2 November International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists[82]

10 November World Science Day for Peace and Development

3rd Thursday in November World Philosophy Day

16 November International Day for Tolerance

19 November International Men's Day

25 November International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women

29 November International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

1 December World AIDS Day

10 December Human Rights Day

18 December International Migrants Day

Member states

Main article: Member states of UNESCO

As of January 2019, UNESCO has 193 member states and 11 associate members.[83] Some members are not independent states and some members have additional National Organizing Committees from some of their dependent territories.[84] UNESCO state parties are the United Nations member states (except Liechtenstein, United States[85] and Israel[86]), as well as Cook Islands, Niue and Palestine.[87][88] The United States and Israel left UNESCO on 31 December 2018.[89]

Governing bodies

Director-General

There has been no elected UNESCO Director-General from Southeast Asia, South Asia, Central and North Asia, Middle East, North Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, South Africa, Australia-Oceania, and South America since inception.

The Directors-General of UNESCO came from West Europe (5), Central America (1), North America (2), West Africa (1), East Asia (1), and East Europe (1). Out of the 11 Directors-General since inception, women have held the position only twice. Qatar, the Philippines, and Iran are proposing for a Director-General bid by 2021 or 2025. There have never been a Middle Eastern or Southeast Asian UNESCO Director-General since inception. The ASEAN bloc and some Pacific and Latin American nations support the possible bid of the Philippines, which is culturally Asian, Oceanic, and Latin. Qatar and Iran, on the other hand, have fragmented support in the Middle East. Egypt, Israel, and Madagascar are also vying for the position but have yet to express a direct or indirect proposal. Both Qatar and Egypt lost in the 2017 bid against France.

The list of the Directors-General of UNESCO since its establishment in 1946 is as follows:[90]

Name / Country / Term

Audrey Azoulay France 2017–present

Irina Bokova Bulgaria 2009–2017

Koïchiro Matsuura Japan 1999–2009

Federico Mayor Zaragoza Spain 1987–99

Amadou-Mahtar M'Bow Senegal 1974–87

René Maheu France 1961–74; acting 1961

Vittorino Veronese Italy 1958–61

Luther Evans United States 1953–58

John Wilkinson Taylor United States acting 1952–53

Jaime Torres Bodet Mexico 1948–52

Julian Huxley United Kingdom 1946–48

General Conference

This is the list of the sessions of the UNESCO General Conference held since 1946:[91]

Session / Location / Year / Chaired by / from

39th Paris 2017 Zohour Alaoui[92] Morocco

38th Paris 2015 Stanley Mutumba Simataa[93] Namibia

37th[94] Paris 2013 Hao Ping China

36th Paris 2011 Katalin Bogyay Hungary

35th Paris 2009 Davidson Hepburn Bahamas

34th Paris 2007 George N. Anastassopoulos Greece

33rd Paris 2005 Musa Bin Jaafar Bin Hassan Oman

32nd Paris 2003 Michael Omolewa Nigeria

31st Paris 2001 Ahmad Jalali Iran

30th Paris 1999 Jaroslava Moserová Czech Republic

29th Paris 1997 Eduardo Portella Brazil

28th Paris 1995 Torben Krogh Denmark

27th Paris 1993 Ahmed Saleh Sayyad Yemen

26th Paris 1991 Bethwell Allan Ogot Kenya

25th Paris 1989 Anwar Ibrahim Malaysia

24th Paris 1987 Guillermo Putzeys Alvarez Guatemala

23rd Sofia 1985 Nikolai Todorov Bulgaria

22nd Paris 1983 Saïd Tell Jordan

4th extraordinary Paris 1982

21st Belgrade 1980 Ivo Margan Yugoslavia

20th Paris 1978 Napoléon LeBlanc Canada

19th Nairobi 1976 Taaita Toweett Kenya

18th Paris 1974 Magda Jóború Hungary

3rd extraordinary Paris 1973

17th Paris 1972 Toru Haguiwara Japan

16th Paris 1970 Atilio Dell'Oro Maini Argentina

15th Paris 1968 William Eteki Mboumoua Cameroon

14th Paris 1966 Bedrettin Tuncel Turkey

13th Paris 1964 Norair Sisakian Soviet Union

12th Paris 1962 Paulo de Berrêdo Carneiro Brazil

11th Paris 1960 Akale-Work Abte-Wold Ethiopia

10th Paris 1958 Jean Berthoin France

9th New Delhi 1956 Abul Kalam Azad India

8th Montevideo 1954 Justino Zavala Muñiz Uruguay

2nd extraordinary Paris 1953

7th Paris 1952 Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan India

6th Paris 1951 Howland H. Sargeant United States

5th Florence 1950 Stefano Jacini Italy

4th Paris 1949 Edward Ronald Walker Australia

1st extraordinary Paris 1948

3rd Beirut 1948 Hamid Bey Frangie Lebanon

2nd Mexico City 1947 Manuel Gual Vidal Mexico

1st Paris 1946 Léon Blum France