Part 2 of 2

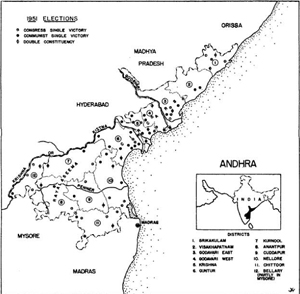

VII. THE RANGA-CONGRESS ALLIANCE IN 1955After the 1951 elections and the formation of the Andhra State in 1953, open Kamma-Reddi warfare increased with the two rivals now pitted directly against each other. No longer was there the intervening presence of non-Andhra elements in a multi-lingual legislature. Even Jawaharlal Nehru could not bring N. G. Ranga under the wing of Sanjiva Reddi's party leadership.67 The controversy over the choice of the new state's capital once again polarized Andhra politics on what was now widely conceded to be a regional-caste basis, the Reddi-dominated Congress winning the selection of Kurnool in Rayalaseema over the bitter protests of the Communists and Ranga's KLP as champions of the delta.68

Puchalapalli Sundarayya charged that the Congress:

... wanted to rouse regional feelings; it wanted to rouse communal feelings, and that is why it selected Kurnool as the capital.... The Congress raises the slogan of Reddi vs. Kamma. It says: If you want to change from Kurnool to any centralized place, then Kamma domination will come and Reddi domination will go. These are facts that cannot be controverted by anybody who knows anything about Andhra.69

A newspaper correspondent reported during this episode that:

In recent years the rivalry between the Reddys of Rayalaseema and rich Kammas of delta districts has grown to alarming proportions. Congressmen have tended to group themselves on communal lines, and the Sanjiva Reddy-Ranga tussle for leadership which finally resulted in Ranga's exit from the Congress is a major instance in this regard. And rightly or wrongly the choice of Kurnool is looked upon by the Kammas as another major triumph for the Reddys.70

Ostensibly, the Congress stand for Kurnool in the capital dispute honored a 1937 commitment by Congress leaders from the delta that the underdog Rayalaseema area could have first claim in the location of the capital or High Court of the future Andhra State, with the delta getting the one left over. But in the 1953 wrangle there was more at stake. Both the Communists and the KLP were voicing not only the local pride of the delta communities seeking the capital, but real estate and mercantile interests as well.71

By the time the first Andhra Congress ministry had collapsed in November, 1954, a scant year after its installation, Congress leaders in New Delhi had come to realize that firm intervention from outside would be necessary to forge a united front for the new elections in February, 1955. From Jawaharlal Nehru down, there was a determination that the history of the 1951 Kamma defection should not repeat itself. For N. G. Ranga this was an important political moment in which his whole future as a Kamma spokesman lay at stake.

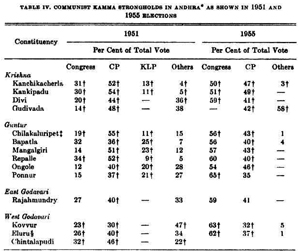

Nehru summoned the forces of Ranga, T. Prakasam, Sanjiva Reddi, and assorted other anti-Communist Andhra leaders to map a united election campaign. Working closely with such Kamma Congress powers as Kotta Raghuramaiah, India's delegate to the U.N. Trusteeship Council, Ranga emerged from the negotiations with control over nominations in 38 constituencies as part of a Congress United Front, enough to assure a single Kamma entry by Congress forces in all Kamma strongholds. The regular Congress organization received 136 constituencies and the People's party, a Prakasam rump group comprising Andhra remnants of the defunct KMP, won control of nominations in 20 constituencies.Although Sanjiva Reddi, leader of what by then was popularly called "The Rayalaseema Junta," sulked in protest against the very principle of alliance with Ranga,72 the pressure for a joint front against the Communists was too much for him. The Congress high command assigned Bombay Congress strong man S. K. Patil to enforce factional unity. With the Congress camp united, independents shunned battle. There were 78 straight contests between the Congress and the Communists, 65 more with only three contestants, and in only the remaining 53 was there the dispersion of 1951. The Communists, confidently dashing into the fray, had announced their candidate lists in the first week of December to place themselves squarely on the offensive. But this cut two ways: the Congress had time to match caste with caste in selecting candidates. The upshot was that in their delta stronghold the Communists won only 11 seats, two of these in reserved constituencies, as opposed to their 31 delta seats in 1951. A solitary Kamma was elected on the Communist ticket.73

Ironically, in 1955 their caste may in certain cases have been a liability to Kamma Communists. The defection of C.V.K. Rao, a Communist leader of the Devadasi caste, was openly trumpeted in anti-Kamma terms by Rao's election-rump "Communist Unity Centre." Handbills ridiculing Communist leaders as "Red landlords" sufficiently nettled them to elicit a special campaign appearance by Rajeshwar Rao. Announcing that he and his brother had donated the equivalent of $40,000 over the years to Communist coffers, Rajeshwar Rao added: "I do not say that all our property is exhausted; there is still something left. We shall spend it, along with our lives, in the service of the people."74The Communists made every bit as intensive an effort in 1955 as in 1951 to capitalize on the Kamma "social base"76 in the delta, running Kamma candidates in 29 delta constituencies. Underscoring the Kamma orientation of Communist tactics is the fact that in nine of these 29 constituencies, the Communist candidate was the only Kamma in the field.

With anti-Communist Kamma forces consolidated in the Congress, however, the Communists could not make their Kamma support a decisive factor in 1955. Confronted with a single Kamma opponent (see Table IV), the Communist Kamma candidate was in a defensive position. N.G. Ranga had recaptured the initiative in the contest for Kamma support by showing he could drive a hard bargain for the caste within Congress councils. The 28 Kamma Communist losers still won substantial support in their caste strongholds -- an average 38.7 per cent of the votes. But this was a drop from an average 44.6 per cent polled by the 14 Kamma Communist winners in 1951.

Despite this six per cent decline in their Kamma strength, the Communists increased their popular vote in most of the delta just as in the rest of Andhra.76 This is explained by the even distribution of their 1955 vote over a wide range of constituencies, in contrast to spotty 1951 voting concentrations in constituencies where they then enjoyed strong Kamma support. Unlike 1951, when the Communist Kammas fared better than other Communist candidates, the Communist Kammas in 1955 were on a par with the 34 other defeated Communist candidates in the delta. Defeated non-Kamma Communist candidates in the delta in 1955 averaged 38.3 per cent, while in 1951 non-Kamma Communist losers had polled only 22 per cent, and even defeated Kammas had polled only 33.1 per cent.

The Communist share of Kamma support went a long distance with the Congress Kamma camp divided in 1951, but the Ranga-Congress alliance made Communist inroads on Kamma backing less significant in 1955. Nor did the issues fall on the Communist side in 1955 as they had in 1951. The Kammas responded to the general strength of the Congress cause, coupled with a successful appeal to the caste's economic stake in keeping the Communist party out of power. The Congress election platform stressed agricultural price support. The Communist press bitterly complained that propertied interests had ganged up against them. In a reference to Divi, the home constituency of the Kamma Rajeshwar Rao, the Communist weekly New Age declared that "all quarrels of caste or community have been forgotten. They [the landlords] have united to face the common people. They are all in the Congress now".77

While Congress leaders such as S. K Patil deluged all Andhra with effective anti-Communist propaganda, the body blow to the delta Communists came from the fact that the veteran anti-Communist ideologian, N.G, Ranga, now had the prestige to make an effective appeal in the Kamma constituencies, the central arena of the contest. G. S. Bhargava reported from Andhra that credit for delivering the telling punch in the delta "must go to the KLP leader, Mr. N.G. Ranga, who for the first time carried the fight against communism into villages hitherto regarded as impregnable Communist fortresses."78 A. Kaleswara Rao, a Grand Old Man of the Andhra Congress, wrote the author at the time polling was about to take place: "The Congress United Front formed by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, roping in Sri Ranga ... is very successful in the Communist-infested districts, e.g. in central Andhra. The Kamma community, which is predominant in this area, have joined the Congress United Front with patriotism."79

The reference to patriotism is important, for undoubtedly the fact that a procession of respected national Congress leaders came to Andhra to denounce the Communists in unequivocal terms of nationalism played an important election role, not only in rousing Kamma support, but throughout Andhra. Jawaharlal Nehru attacked the Communists as "professional maligners of the Indian people."80 Congress president U. N. Dhebar warned Andhra voters that "if one Communist state in India is established, our international strength will be lost."81 S. K. Patil's posters and pamphlets blasted the Communists as outright traitors, painting gruesome pictures of horror in China and the Soviet Union.82 The fall of Malenkov on February 8, just as polling was getting underway, was a convenient reminder of past purges. Moreover, the Congress had dulled the ideological edge of the Communist appeal at its national session at Avadi in January by announcing a "socialistic pattern of society" as its goal. What hurt even more, the Communists were denied the support of Russian policy and its propaganda machine. Pravda published an historic editorial on the eve of India's Republic Day, January 26, marking the end of seven years of attacks on the Nehru government and confounding the Communists' election strategy. How could the Communists parade the banner of an international big brother who praised "the outstanding statesman, Mr. Jawaharlal Nehru,"83 at the same time they were waging an election campaign against his party?

VIII. WILL THE KAMMAS AND REDDIS WORK TOGETHER?By successfully making Indian nationalism a live issue in a state election, the Congress, still for all its sins a symbol of independence, was calling forth its trump card. The resultant election-time atmosphere was a complete reversal of 1951, when the Communists had been able to wrap themselves in the banner of the Andhra provincial autonomy movement and make Telugu patriotism a live ballot issue.

But Andhra's formation as the first frankly linguistic state in India, while relaxing the tension between the Telugus and the central government, only heightened the political struggle among Telugu castes. The newly intimate confrontation of Kammas and Reddis in Andhra typifies one of the less obvious consequences of linguistic provinces in India. By and large, the endogamous group or subcaste in India is bounded on a linguistic basis.84 Thus, the power relationship of castes to each other in a multi-lingual political unit with its many caste groups differs radically from the reality of their relationship in the smaller linguistic unit. The Kammas and Reddis were part of the welter of castes in the old Madras State, but in Andhra they face each other as titans.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Nehru's former Law Minister, sees this through the eyes of an outcaste when he warns that the formation of linguistic provinces "means the handing over of Swaraj to a communal majority."85 Switzerland, Ambedkar said in a Parliament debate, "has no difficulties as a multi-lingual state because linguism there is not loaded with communalism. But in our country linguism is only another name for communalism ."86 "Take Andhra," he wrote, "there are two major communities spread over the linguistic area. They are either the Reddis or the Kammas. They hold all the land, all the offices, all the business. The untouchables live in subordinate dependence on them. Take Maharashtra; the Marathas are a huge majority in every village in Maharashtra ... In a linguistic stale what would remain for the smaller communities to look to?"87

The broad implications of the conjunction between caste and language region and, more specifically, of the change in the vantage of castes which is likely to result from the formation of new linguistic provinces, deserve searching study. In the case of Andhra, it is already clear that political stability will depend to a great extent on the ability of Reddi and Kamma leaders to work together in a united government.

Developments since the 1955 elections suggest strongly that the future Kamma-Reddi relationship remains to be decided. At first, N. G. Ranga announced that the KLP, which had kept its party identity intact as a member of the election front, would return unconditionally to the Congress.88 It was generally understood that Ranga had been promised the presidency of the Andhra Congress, with B. Gopala Reddi to be named Chief Minister. Reddi did become Chief Minister, but in the election of the party president, the forces of Deputy Chief Minister N. Sanjiva Reddi successfully fought N. G. Ranga with a Kshatriya candidate, Alluri Satyanarayana Raju. Ranga's defeat was a setback not only to Kamma-Reddi amity but also to the personal prestige of Gopala Reddi, and a signal for Sanjiva Reddi to assail him as a Kamma stooge.

A breakdown of Congress legislators elected in 1955 shows 85 out of the 146 deputies divided between the three major peasant proprietor subcastes, with Reddis the largest group (45), Kammas next (24), and the Telagas a newly-active political force (16) to be reckoned with. The Gopala Reddi cabinet reflected the Kamma and Reddi strength in the party's legialative ranks with two Reddi ministers (Gopala Reddi and Sanjiva Reddi), two Kammas (K. Chandramouli and G. Latchanna),89 and two Brahmans (Kala Venkata Rao and Nageswara Rao). The Telagas, not yet able to make their weight felt, received no representation in the ministry; here may be the makings of a new "out" group. Further, subcaste divisions within both Kamma and Reddi ranks could harden into a still more complex array of political battle lines.

The Indian Government's announced intention to merge Andhra and Telengana in a "United Andhra" poses the prospect of a basic realignment in the power balance between Telugu castes. If this merger takes effect, the delta Kammas in the new larger unit would confront not only the Reddis of Rayalaseema, but also the politically distinct Telengana Reddis -- whose rivals on their home ground have been the Telengana Brahmans. Already the Reddi-Brahman rivals in Telengana and the Kamma-Reddi antagonists in Andhra can be seen each jockeying to establish ties across the border. To complicate matters still more, the Telengana Communist leadership lacks caste homogeneity. Ravi Narayan Reddi and a Brahmin, D. V. Rao, lead rival factions. How will these rivals adjust to their new common relationship to the delta Communist leaders?

Whether or not the solidarity of their leadership suffers in a United Andhra, certainly the Communists, in their efforts to make a comeback, will exploit caste disaffection wherever they can. In 1955 their campaign manifesto showed a new interest in such politically strategic Andhra artisan castes as the Kammari (blacksmith), Kummari (potter), Vadrangi (carpenter), Rajaka (washermen), Mangali (barber), and Ganda (toddy tappers).90 As an opposition playing its main role outside the legislature, the party will be in a free-wheeling tactical position, able to step in wherever there is an opening in the Congress flank.91

The failure of the Andhra Communists to win strong legislative representation in 1955 is by no means a final political verdict. In doubling their popular vote, not only did their strength remain concentrated in their demonstrated stronghold, but also in two of the delta district, West Godavari and Guntur, they increased their poll by as much as 16 per cent and 10 per cent respectively.92 Furthermore, as The Hindu has pointed out,93 "in a large number of constituencies they missed success by very small majorities."94 These facts spell a clear warning against "underrating the threat to peace and progress that the Andhra Communist Party is still potentially capable of offering."

_______________

Notes:* The field research for this study was conducted during the author's three years in India as Associated Press correspondent, 1951-54. Research was completed as a consultant to the Modern India Project, University of California (Berkeley). Statistical data were compiled with the assistance of the Littauer Statistical Laboratory, Harvard University, where the author was Nieman Fellow in 1954-55.

1 A forthcoming full-length study by the author to be published by the Modern India Project, University of California (Berkeley), seeks to analyze the challenge presented by regional particularisms throughout India to the development of Indian nationalism.

2 All-India Rural Credit Survey, Vol. 2: General Report (Bombay, 1954), p. 54

3 Bhargava, G. S. discusses this in A Study of the Communist Movement in Andhra (Delhi, Siddhartha Publications, 1955), pp. 2, 14, 22–34 Google Scholar; see also Choudary, K. B., A Brief History of the Kammas (Sangamjagarlamudi, Andhra: published by the author, 1955), pp. 98, 123

4 Choudary, A Brief History of Kammas, p. 124 Google Scholar, notes that “the Second World War and the years that have followed have once again seen rocketing of the prices of paddy, pulses, turmeric, tobacco, and fruits. These have been very prosperous years for agricultural communities like Kammas.”

5 This is the private consensus of members of different Andhra castes. No official figures exist showing caste land ownership in Madras.

6 Katragadda Rajagopal Rao's role is noted in “The Future of Andhra,” Thought (New Delhi), Oct. 3, 1953, p. 4

7 The holdings of the six Katragadda brothers are described in Joshi, P. C., Among Kisan Patriots (Bombay, People's Publishing House, 1946), p. 4 This pamphlet reviews the Vijayawada, Andhra, session of The All-India Kisan Sabha.

8 Kamma status in the delta is so described in “How Red is Andhra?,” The People (pro-Congress weekly, New Delhi), March 4, 1952, p. 8

9 For an excellent description of the manner in which a dominant caste can mold village behavior, see All-India Rural Credit Survey, pp. 56–58.

10 In an interview with an editor of the New Age, Feb. 13, 1955, p. 7

11 These three have remained members of the secretariat of the Andhra Communist Committee in all reshuffles announced in the Communist press. The most recently declared (1954) membership of the Secretariat also included in its eight names four other Kammas: M. Hanumantha Rao, a member of the Indian Communist Central Committee; G. Satyanarayana; K. Gopal Rao, a member of the lower house of the Indian Parliament; and Krishna Rao.

This caste breakdown and the tables in this study showing castes of Congress and Communist candidates and legislators have been compiled through the cooperation of members of major Telugu castes. The compilation has included a cross-check test of the designations made by each cooperating informant by other persons of different castes.

12 Kulak pettamdar recurs throughout Rao, C.V.K., Rashtra Communist. Navakalhwapu Bandaram [Bluff of the Andhra Communist Leadership] (Masulipatnam, Andhra, 1954) Rao is a member of the Devadasi caste. Partially translated from Telugu for the author.

13 Reddi power in the Congress figures in Rao, D. V. Raja, “Election Lessons,” Swatantra, Feb. 15, 1952, p. 13 Google Scholar; Choudary, A Brief History of the Kammas (cited in note 3), p. 97 Google Scholar; and an earlier article by the author, “How Nehru Did It in Andhra,” New Republic, March 21, 1955, p. 7

14 See Choudary, A Brief History of the Kammas (cited in note 3), p. 55 Google Scholar, and his earlier three-volume history, Kammacharitra Sangraham (Sangamjagarlamudi, Andhra: published by the author, 1939), Vol. 1, p. 20 Partially translated from Telugu for the author.

15 Bhargava, A Study of the Communist Movement in Andhra (cited in note 3), p. 14 Google Scholar, traces the present degree of Kamma-Reddi enmity to the turn of the century.

16 Sat-(Good) Sudra status is accorded to Kammas, Reddis, Velamas, and other Telugu peasant proprietor subcastes to distinguish them from less prosperous Sudra subcastes, according to Francis, W., Census of India, 1901, Vol. 15: Madras, Part I (Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1903), p. 136

17 See Thurston, Edgar, Castes and Tribes of Southern India, 14 vols. (Madras: Government Press, 1909), Vol. 3, p. 94 Google Scholar; MacKenzie, G., Manual of Kistna District (Madras, 1883), p. 53 Google Scholar; Census of India, 1901, Vol. 15, p. 159 Google Scholar; Hutton, J. H., Caste in India (London: Oxford University Press, 1946), p. 11

18 The last in which district caste tables for Madras are available.

19 Census of India, 1921, Vol. 13: Madras, Part IT, by Boag, G. T. (Madras: Superintendent of Government Press, 1922), Table XIII, p. 119

20 Reddis are also referred to by anthropologists as Kapus. However, this terminology is confusing in contemporary Andhra; Kapu is loosely applied to other non-Brahman peasant castes.

21 Census of India, 1921, Vol. 13, Table IX, p. 77

22 Choudary, A Brief History of the Kammas (cited in note 3), p. 122

23 A coalition of aggrieved non-Brahman castes throughout South India.

24 Choudary, A Brief History of the Kammas (cited in note 3), pp. 97–98

25 A brilliant orator in Telugu, Sundarayya is the party's most popular mass leader in Andhra.

26 “Delimitation of Madras Constituencies,” Government of India (Provincial Legislative Assemblies) Order, 1936, cited in Narain, Jagat, Law of Elections in India and Burma (Calcutta: Eastern Law House, 1937), pp. 250–58

27 Return Showing the Results of Elections to the Central Legislative Assembly and Provincial Legislatures, 1945–46 (New Delhi: Government of India, 1946)

28 The legislature was increased from 160 to 196 members before the 1955 elections in a new delimitation of constituencies.

29 For example, The Hindu, March 10, 1955, p. 4 This issue also contains detailed election statistics.

30 Shea, Thomas, “Agrarian Unrest and Reform in South India,” Far Eastern Survey, Vol. 23, pp. 81–88, at pp. 84–85 (June, 1954). See also District Census (1951) Handbooks (Madras: Government Press, 1953)Google Scholar, Tables D-III: Krishna, p. 183; West Godavari, p. 168: East Godavari, p. 292; Guntur, p. 206.

31 For the history of the Andhra Communist party, see Sundarayya, P., Vishalandralu Prajarajvan [People's Rule in Vishalandhra] (Vijayawada: Vishalandhra Publishing House, 1946)Google Scholar, Ch. 6. Translated from Telugu for the author.

32 “The Struggle for People's Democracy and Socialism, Some Questions of Strategy and Tactics,” The Communist, Vol. 2, pp. 21–90, at p. 35 (June–July, 1949) This was formerly the monthly organ of the Communist party of India.

For additional references to Communist organization of agricultural labor in Andhra, see Rao, N. Prasada, “Agricultural Laborers Association,” News Bulletin of the All-India Kisan Sabha, Oct.–Nov., 1952, p. 22 Google Scholar, which terms agricultural labor “the rock-like base of the [Communist] movement in Andhra”; and “Second Andhra Agricultural Labor Conference,” Aug., 1953, p. 6 Google Scholar, setting organized strength in the region then at 94,890.

33 Imperial Gazeteer of India, Provincial Series, Madras I (Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1908), p. 309 See canal locations in frontispiece maps in District Census (1951) Handbooks; note also Cushing, S. W., “The Geography of Godavari,” Bulletin of Geographic Society of Philadelphia, Vol. 9, pp. 2–3 (Oct., 1911)Google Scholar, reprinted.

34 The Hindu, March 3, 1952, p. 1

35 Ghosh, Ajoy, “The Andhra Elections and the Communist Party,” New Age, March 4, 1955, p. 1 New Age is the weekly organ of the Communist party in India.

36 For example, see “Andhra Victory,” editorial in Times of India, March 10, 1955, p. 4

37 Public General Acts and Measures, Vol. 1. Sixth Schedule, Part II: Madras (London, 1935–1936), pp. 256–57 H.M.S.O.

38 For example, Ranga, N. G., Outlines of National Revolutionary Path (Bombay, Hind Kitabs, 1945), pp. 109–10

39 The Communist role during the war is summarized in The Communist Party of India, Publication No. 2681, Research and Analysis Branch, Office of Strategic Services, August, 1945, p. 21 Google Scholar; note also P. Sundarayya, op. cit., Ch. 6, where it is estimated that Andhra Communist membership rose from 1,000 in 1942 to 8,000 in 1945.

40 Narayan, Jayaprakash, Towards Struggle (Bombay, Padma Publications, 1946), pp. 171, 174

41 P. Venkateswarulu in West Godavari-cum Kistna-cum Guntur (Non-union) Factory Labor constituency.

42 Ellore, 19.3; Bhimavaram, 19.4; Narsapur, 21.4; Bandar, 28.4; Bezwada, 31.9, Guntur, 26.9; Narasaropet, 17; Tenali, 16.6; Ongole, 14.4; Rajahmundry, 11.5; and Amalapuram, 18.4.

43 The designation of Munagala as headquarters during this period is part of a colorful description of the Telengana movement as seen by delta Congress leaders in Charges against the Madras Ministry (by Certain M LAs), published by Rao, A. Kaleswara, (Madras, Renaissance Printers Ltd., 1948), p. 28

44 An example of this characterization is in The Communist, Vol. 2, p. 71 (June–July, 1949)

45 Ibid., p. 34.

46 The 1948 report appears in part in Self-Critical Report of the Andhra Communist Committee, January 1948–February 1952, Part Two, March 1949–March 1950, a party document not intended for publication.

47 The Communist, June–July, 1949, p. 72

48 Ibid., p. 60.

49 Kautsky, John H., Moscow and the Communist Party of India (Cambridge, Mass., Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1954), pp. 124, 128

50 Editorial in For a Lasting Peace, for a People's Democracy, Jan. 27, 1950.

51 “Statement of Editorial Board on Anti-Leninist Criticism of Comrade Mao-Tsetung,” The Communist, Vol. 3, pp. 6–35, at pp. 6–7 (July–Aug., 1950)

52 Masani, M. R., The Communist Party of India (New York, 1954), p. 110

53 “For Settlement in Telengana,” editorial in the then national weekly of the Communist Party of India, Crossroads, Aug. 3, 1951, p. 1

54 “Reds' Threat,” Congress Sandesh, Nov. 19, 1951, p. 4

55 The decision to release the Communist detenus is generally attributed to Prime Minister Nehru. A high Indian official with responsibilities in this matter told the author at the time that Nehru felt the Communists would prosper more if permitted to increase their martyrdom behind bars than if out in the open where, given enough rope, they might eventually be their own undoing.

56 Charges against the Madras Ministry (cited in note 43), pp. 6–7, 30–31.

57 Choudary, A Brief History of the Kammas (cited in note 3), p. 98

58 C. V. K. Rao, op. cit. (in note 12), says that Dharma Rao, a brother-in-law of Basava Punniah, has enrolled hundreds of Kammas as actual party members on the promise that the caste group would benefit when the CP came to power. As an example of specific allusions to Communist Kamma support, see also “CPI May Win More Seats in Madras,” The Statesman, Jan. 8, 1952, p. 1

59 The figure of 25 excludes six reserved constituencies in which Communists won in the delta.

60 Census of India, 1921, Vol. 13, Table XIII, p. 119 Google Scholar, showa 109,969 Kammas and 208,018 Reddis in Nellore.

61 Venkatagiri, Gudur, and Rapur.

62 Kanigiri and Darsi.

63 Kovur.

64 Nandikotkur in Kurnool; Kamalapuram and Rajampet in Cuddapah; and Anantapur in Anantapur District were the sites of other Communist Reddi successes.

65 Quoted by D. V. Raja Rao, op. cit. (in note 13), p. 13.

66 “Congress Reverses in Madras,” Hindustan Standard, Jan. 14, 1952, p. 8

67 “Ranga Keeps Out,” Times of India, Oct. 2, 1953, p. 1

68 For example, see “Andhra Election Scene,” Times of India, Jan. 10, 1955, p. 6

69 “We Demand Free and Fair Elections,” Parliament speech by Sundarayya, P., cited in For Victory in Andhra, CPI publication (Delhi, 1955), p. 13

70 Times of India (Bombay), June 16, 1953, p. 7

71 In “The Future of Andhra,” Thought, Oct. 3, 1953 Google Scholar | PubMed, G. S. Bhargava reports that Kamma property owners in Vijayawada had confidently based land investments on the expectation that the capital would be there, and suffered heavy losses.

72 “Rift in Andhra Congress,” Times of India, Jan. 1, 1955, p. 10

73 V. Visweswara Rao in Mylavaram constituency, Krishna District.

74 New Age, Dec. 26, 1954, p. 16

75 This phrase is attributed to the Communists in “Caste Factor,” Times of India, Feb. 1, 1955. p. 6

76 While the popular vote increased in Krishna, for the Communists their increase did not keep pace with the overall increase; the Communist percentage of the total in the district dropped from 48 per cent in 1951 to 44 in 1955.

77 New Age, Jan. 17, 1955, p. 3

78 Bhargava, G. S., “Verdict on Communism,” Ambala Tribune, March 15, 1955, p. 4

79 Analysis prepared for the author, dated Feb. 19, 1955, Vijayawada. Rao has served on the All-India Congress Committee for over 30 years. He was elected a member of the Andhra legislature from the Vijayawada constituency in the 1955 election.

80 Times of India, Jan. 16, 1955, p. 4

81 The Hindu, Feb. 8, 1955, p. 4

82 See “Nehru's Congress Filth,” New Age, Feb. 6, 1955

83 Cited in Times of India, Feb. 1, 1955, p. 3 The editorial also stated that the Indian Republic was “a peace-loving state upholding its national independence,” which has “set itself to the grim task of gradually eliminating colonialism.”

84 Karve, Irawati, in Kinship Organization in India, Deccan College Monograph Series (Poona, 1953)Google Scholar, discusses the conjunction of caste and language region at length (esp. pp. 1–24); Ghurye, G. S., Caste and Class in India (Bombay: Popular Book Depot, 1950), p. 23 Google Scholar, says that “in the beginning of the 19th century, the linguistic boundaries fixed the caste limits.” See also pp. 19 and 32; and Hutton, J. H., Caste in India (cited in note 17), p. 10

85 Ambedkar, B. R., “Linguistic States—Need for Checks and Balances,” Times of India, April 23, 1953, p. 4

86 “Ambedkar's Plea for Amendment of Constitution,” Hindustan Times, Sept. 3. 1953, p. 3

87 B. R. Ambedkar, “Linguistic States—Need for Checks and Balances” (cited in note 85).

88 “KLP to Join the Congress,” The Hindu, March 1, 1955, p. 4

89 Latchanna is a member of the Sree-Sainaa, a Srikakulam subcaste group kindred to the delta Kammas and organized politically by Ranga's KLP.

90 A Communist-backed toddy-tappers' agitation in the summer of 1954 is noted in Windmiller, Marshall, “The Andhra Election,” Far Eastern Survey, Vol. 24, pp. 27–28 (April, 1955)

91 The Congress government in Andhra appears to be assured its tenure until 1960 under Article 172 of the Indian Constitution, providing for five-year duration of state legislative assemblies. Under this provision Andhra need not elect a new legislature when the next general elections are held throughout India, probably in 1957. The formation of a united Andhra, incorporating Telugu districts now in Hyderabad state, could necessitate earlier elections.

92 West Godavari, 195,024 in 1951 to 265,193 in 1955; Guntur, 289,932 to 392,268.

93 “Andhra Verdict,” The Hindu, March 9, 1955, p. 4

94 While the Congress margin of victory averaged 13 per cent in Krishna and West Godavari district constituencies, 16 per cent in Guntur, and 21 per cent in East Godavari, these margins do not represent crushing defeat when it is kept in mind that these were straight fights pitting a three-party Congress coalition on one side against the Communists on the other.

Moreover, the per cent of voting in delta constituencies for Communist candidates shows an average decline in Krishna only, from an average 48 per cent of the constituency vote in 1951 to an average 43 in 1955. In Guntur, it increased from 40 to 41; in East Godavari, from 38 to 39; in West Godavari, from 32 to 41.

Outside the delta, where the Communists made virtually no effort in 1951, they emerged in 1955 with an average 22 per cent of the votes in 18 Vizagapatnam constituencies where they contested; 23 per cent in 12 constituencies, Srikakulam; 35 in 13, Anantapur; 26 in 8, Cuddapah; 30 in 11, Kurnool; 37 in 19, Nellore; and 34 in 11, Chittoor.