by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/15/20

What is popularly called Transcendentalism among us, is Idealism; Idealism as it appears in 1842....mankind have ever divided into two sects, Materialists and Idealists; the first class founding on experience, the second on consciousness; the first class beginning to think from the data of the senses, the second class perceive that the senses are not final, and say, the senses give us representations of things, but what are the things themselves, they cannot tell. The materialist insists on facts, on history, on the force of circumstances, and the animal wants of man; the idealist on the power of Thought and of Will, on inspiration, on miracle, on individual culture....Every materialist will be an idealist; but an idealist can never go backward to be a materialist.

The idealist, in speaking of events, sees them as spirits....He does not deny the presence of this table, this chair, and the walls of this room, but he looks at these things as the reverse side of the tapestry, as the other end, each being a sequel or completion of a spiritual fact which nearly concerns him. This manner of looking at things, transfers every object in nature from an independent and anomalous position without there, into the consciousness....

The idealist takes his departure from his consciousness, and reckons the world an appearance...which is metaphysical....Mind is the only reality, of which men and all other natures are better or worse reflectors. Nature, literature, history, are only subjective phenomena.... His experience inclines him to behold the procession of facts you call the world, as flowing perpetually outward from an invisible, unsounded centre in himself, centre alike of him and of them, and necessitating him to regard all things as having a subjective or relative existence, relative to that aforesaid Unknown Centre of him.

From this transfer of the world into the consciousness, this beholding of all things in the mind, follow easily his whole ethics. It is simpler to be self-dependent. The height, the deity of man is, to be self-sustained, to need no gift, no foreign force. Society is good when it does not violate me; but best when it is likest to solitude. Everything real is self-existent. Everything divine shares the self-existence of Deity. All that you call the world is the shadow of that substance which you are, the perpetual creation of the powers of thought, of those that are dependent and of those that are independent of your will. Do not cumber yourself with fruitless pains to mend and remedy remote effects; let the soul be erect, and all things will go well. You think me the child of my circumstances: I make my circumstance. Let any thought or motive of mine be different from that they are, the difference will transform my condition and economy. I — this thought which is called I, — is the mould into which the world is poured like melted wax. The mould is invisible, but the world betrays the shape of the mould. You call it the power of circumstance, but it is the power of me....

The Transcendentalist adopts the whole connection of spiritual doctrine. He believes in miracle, in the perpetual openness of the human mind to new influx of light and power; he believes in inspiration, and in ecstasy. He wishes that the spiritual principle should be suffered to demonstrate itself to the end, in all possible applications to the state of man, without the admission of anything unspiritual... the spiritual measure of inspiration is the depth of the thought, and never, who said it?...

[H]e, who has the Lawgiver, may with safety not only neglect, but even contravene every written commandment....

Jacobi, refusing all measure of right and wrong except the determinations of the private spirit, remarks that there is no crime but has sometimes been a virtue. "I," he says, "am that atheist, that godless person who, in opposition to an imaginary doctrine of calculation, would lie as the dying Desdemona lied; would lie and deceive, as Pylades when he personated Orestes; would assassinate like Timoleon; would perjure myself like Epaminondas, and John de Witt; I would resolve on suicide like Cato; I would commit sacrilege with David; yea, and pluck ears of corn on the Sabbath, for no other reason than that I was fainting for lack of food. For, I have assurance in myself, that, in pardoning these faults according to the letter, man exerts the sovereign right which the majesty of his being confers on him; he sets the seal of his divine nature to the grace he accords."

In like manner, if there is anything grand and daring in human thought or virtue, any reliance on the vast, the unknown; any presentiment; any extravagance of faith, the spiritualist adopts it as most in nature. The oriental mind has always tended to this largeness. Buddhism is an expression of it....

[O]f a purely spiritual life, history has afforded no example. I mean, we have yet no man who has leaned entirely on his character, and eaten angels' food; who, trusting to his sentiments, found life made of miracles; who, working for universal aims, found himself fed, he knew not how; clothed, sheltered, and weaponed, he knew not how, and yet it was done by his own hands. Only in the instinct of the lower animals, we find the suggestion of the methods of it, and something higher than our understanding. The squirrel hoards nuts, and the bee gathers honey, without knowing what they do, and they are thus provided for without selfishness or disgrace....

Nature is transcendental, exists primarily, necessarily, ever works and advances, yet takes no thought for the morrow....

It is well known to most of my audience, that the Idealism of the present day acquired the name of Transcendental, from the use of that term by Immanuel Kant, of Konigsberg, who replied to the skeptical philosophy of Locke, which insisted that there was nothing in the intellect which was not previously in the experience of the senses, by showing that there was a very important class of ideas, or imperative forms, which did not come by experience, but through which experience was acquired; that these were intuitions of the mind itself; and he denominated them Transcendental forms....whatever belongs to the class of intuitive thought, is popularly called at the present day Transcendental....

[T]hese seething brains, these admirable radicals, these unsocial worshippers, these talkers who talk the sun and moon away....

They are lonely; the spirit of their writing and conversation is lonely; they repel influences; they shun general society; they incline to shut themselves in their chamber in the house, to live in the country rather than in the town, and to find their tasks and amusements in solitude....they are not stockish or brute, — but joyous; susceptible, affectionate; they have even more than others a great wish to be loved. Like the young Mozart, they are rather ready to cry ten times a day, "But are you sure you love me?"...

[A]nd what if they eat clouds, and drink wind, they have not been without service to the race of man.

With this passion for what is great and extraordinary, it cannot be wondered at, that they are repelled by vulgarity and frivolity in people. They say to themselves, It is better to be alone than in bad company. And it is really a wish to be met, — the wish to find society for their hope and religion, — which prompts them to shun what is called society. They feel that they are never so fit for friendship, as when they have quitted mankind, and taken themselves to friend. A picture, a book, a favorite spot in the hills or the woods, which they can people with the fair and worthy creation of the fancy, can give them often forms so vivid, that these for the time shall seem real, and society the illusion....

[U]nwillingly they bear their part of the public and private burdens; they do not willingly share in the public charities, in the public religious rites, in the enterprises of education, of missions foreign or domestic, in the abolition of the slave-trade, or in the temperance society. They do not even like to vote....

On the part of these children, it is replied, that life and their faculty seem to them gifts too rich to be squandered on such trifles as you propose to them. What you call your fundamental institutions, your great and holy causes, seem to them great abuses, and, when nearly seen, paltry matters. Each 'Cause,' as it is called, — say Abolition, Temperance, say Calvinism, or Unitarianism, — becomes speedily a little shop, where the article, let it have been at first never so subtle and ethereal, is now made up into portable and convenient cakes, and retailed in small quantities to suit purchasers. You make very free use of these words 'great' and 'holy,' but few things appear to them such. Few persons have any magnificence of nature to inspire enthusiasm, and the philanthropies and charities have a certain air of quackery. As to the general course of living, and the daily employments of men, they cannot see much virtue in these, since they are parts of this vicious circle; and, as no great ends are answered by the men, there is nothing noble in the arts by which they are maintained. Nay, they have made the experiment, and found that, from the liberal professions to the coarsest manual labor, and from the courtesies of the academy and the college to the conventions of the cotillon-room and the morning call, there is a spirit of cowardly compromise and seeming, which intimates a frightful skepticism, a life without love, and an activity without an aim....

It is the quality of the moment, not the number of days, of events, or of actors, that imports....

I can sit in a corner and perish, (as you call it,) but I will not move until I have the highest command....

[M]ine is a certain brief experience, which surprised me in the highway or in the market, in some place, at some time...and made me aware that I had played the fool with fools all this time, but that law existed for me and for all; that to me belonged trust, a child's trust and obedience, and the worship of ideas, and I should never be fool more....My life is superficial, takes no root in the deep world; I ask, When shall I die, and be relieved of the responsibility of seeing an Universe which I do not use? I wish to exchange this flash-of-lightning faith for continuous daylight, this fever-glow for a benign climate....

What am I? What but a thought of serenity and independence, an abode in the deep blue sky?...

But this class are not sufficiently characterized, if we omit to add that they are lovers and worshippers of Beauty. In the eternal trinity of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty, each in its perfection including the three, they prefer to make Beauty the sign and head....We call the Beautiful the highest, because it appears to us the golden mean, escaping the dowdiness of the good, and the heartlessness of the true. — They are lovers of nature also, and find an indemnity in the inviolable order of the world for the violated order and grace of man....

Their heart is the ark in which the fire is concealed, which shall burn in a broader and universal flame. Let them obey the Genius then most when his impulse is wildest; then most when he seems to lead to uninhabitable deserts of thought and life; for the path which the hero travels alone is the highway of health and benefit to mankind....

[T]here must be a few persons of purer fire kept specially as gauges and meters of character; persons of a fine, detecting instinct, who betray the smallest accumulations of wit and feeling in the bystander. Perhaps too there might be room for the exciters and monitors; collectors of the heavenly spark with power to convey the electricity to others....

But the thoughts which these few hermits strove to proclaim by silence, as well as by speech, not only by what they did, but by what they forbore to do, shall abide in beauty and strength, to reorganize themselves in nature, to invest themselves anew in other, perhaps higher endowed and happier mixed clay than ours, in fuller union with the surrounding system.

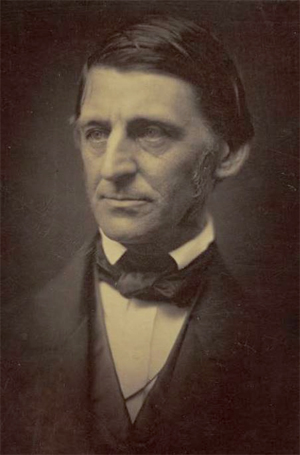

-- A Lecture Read at the Masonic Temple, Boston: The Transcendentalist, from Lectures, published as part of Nature; Addresses and Lectures, by Ralph Waldo Emerson

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in the eastern United States.[1][2][3] A core belief is in the inherent goodness of people and nature.[1] and while society and its institutions have corrupted the purity of the individual, people are at their best when truly "self-reliant" and independent.

Transcendentalism emphasizes subjective intuition over objective empiricism. Adherents believe that individuals are capable of generating completely original insights with little attention and deference to past masters. It arose as a reaction, to protest against the general state of intellectualism and spirituality at the time.[4] The doctrine of the Unitarian church as taught at Harvard Divinity School was closely related.

Transcendentalism emerged from "English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Johann Gottfried Herder and Friedrich Schleiermacher, the skepticism of David Hume",[1] and the transcendental philosophy of Immanuel Kant and German Idealism. Miller and Versluis regard Emanuel Swedenborg as a pervasive influence on transcendentalism.[5][6] It was also strongly influenced by Hindu texts on philosophy of the mind and spirituality, especially the Upanishads.

Origin

Transcendentalism is closely related to Unitarianism, the dominant religious movement in Boston in the early nineteenth century. It started to develop after Unitarianism took hold at Harvard University, following the elections of Henry Ware as the Hollis Professor of Divinity in 1805 and of John Thornton Kirkland as President in 1810. Transcendentalism was not a rejection of Unitarianism; rather, it developed as an organic consequence of the Unitarian emphasis on free conscience and the value of intellectual reason. The transcendentalists were not content with the sobriety, mildness, and calm rationalism of Unitarianism. Instead, they longed for a more intense spiritual experience. Thus, transcendentalism was not born as a counter-movement to Unitarianism, but as a parallel movement to the very ideas introduced by the Unitarians.[7]

Transcendental Club

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Transcendentalism became a coherent movement and a sacred organization with the founding of the Transcendental Club in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on September 8, 1836, by prominent New England intellectuals, including George Putnam (1807–1878), the Unitarian minister in Roxbury,[8] Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Frederic Henry Hedge. Other members of the club included Amos Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson, Theodore Parker,[2] Henry David Thoreau, William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke, Christopher Pearse Cranch, Convers Francis, Sylvester Judd, and Jones Very.[3] Female members included Sophia Ripley, Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Peabody,[4] Ellen Sturgis Hooper, and Caroline Sturgis Tappan.[5]From 1840, the group frequently published in their journal The Dial, along with other venues.

Second wave of transcendentalists

By the late 1840s, Emerson believed that the movement was dying out, and even more so after the death of Margaret Fuller in 1850. "All that can be said," Emerson wrote, "is that she represents an interesting hour and group in American cultivation."[9] There was, however, a second wave of transcendentalists, including Moncure Conway, Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Samuel Longfellow and Franklin Benjamin Sanborn.[10] Notably, the transcendence of the spirit, most often evoked by the poet's prosaic voice, is said to endow in the reader a sense of purposefulness. This is the underlying theme in the majority of transcendentalist essays and papers—all of which are centered on subjects which assert a love for individual expression.[11] Though the group was mostly made up of struggling aesthetes, the wealthiest among them was Samuel Gray Ward, who, after a few contributions to The Dial, focused on his banking career.[12]

Beliefs

Transcendentalists are strong believers in the power of the individual. It is primarily concerned with personal freedom. Their beliefs are closely linked with those of the Romantics, but differ by an attempt to embrace or, at least, to not oppose the empiricism of science.

Transcendental knowledge

Transcendentalists desire to ground their religion and philosophy in principles based upon the German Romanticism of Johann Gottfried Herder and Friedrich Schleiermacher. Transcendentalism merged "English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, the skepticism of Hume",[1] and the transcendental philosophy of Immanuel Kant (and of German Idealism more generally), interpreting Kant's a priori categories as a priori knowledge. Early transcendentalists were largely unacquainted with German philosophy in the original and relied primarily on the writings of Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Victor Cousin, Germaine de Staël, and other English and French commentators for their knowledge of it. The transcendental movement can be described as an American outgrowth of English Romanticism.[citation needed]

Individualism

Transcendentalists believe that society and its institutions—particularly organized religion and political parties—corrupt the purity of the individual.[13] They have faith that people are at their best when truly "self-reliant" and independent. It is only from such real individuals that true community can form. Even with this necessary individuality, transcendentalists also believe that all people are outlets for the "Over-soul." Because the Over-soul is one, this unites all people as one being.[14][need quotation to verify] Emerson alludes to this concept in the introduction of the American Scholar address, "that there is One Man, - present to all particular men only partially, or through one faculty; and that you must take the whole society to find the whole man."[15] Such an ideal is in harmony with Transcendentalist individualism, as each person is empowered to behold within him or herself a piece of the divine Over-soul.

Indian religions

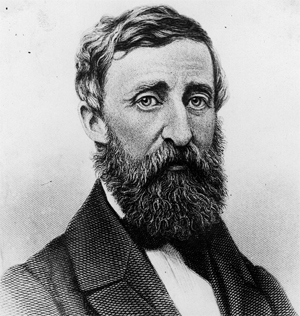

Transcendentalism has been directly influenced by Indian religions.[16][17][note 1] Thoreau in Walden spoke of the Transcendentalists' debt to Indian religions directly:

Henry David Thoreau

In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma, and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water-jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.[18]

In 1844, the first English translation of the Lotus Sutra was included in The Dial, a publication of the New England Transcendentalists, translated from French by Elizabeth Palmer Peabody.[19][20]

Idealism

Transcendentalists differ in their interpretations of the practical aims of will. Some adherents link it with utopian social change; Brownson, for example, connected it with early socialism, but others consider it an exclusively individualist and idealist project. Emerson believed the latter; in his 1842 lecture "The Transcendentalist", he suggested that the goal of a purely transcendental outlook on life was impossible to attain in practice:

You will see by this sketch that there is no such thing as a transcendental party; that there is no pure transcendentalist; that we know of no one but prophets and heralds of such a philosophy; that all who by strong bias of nature have leaned to the spiritual side in doctrine, have stopped short of their goal. We have had many harbingers and forerunners; but of a purely spiritual life, history has afforded no example. I mean, we have yet no man who has leaned entirely on his character, and eaten angels' food; who, trusting to his sentiments, found life made of miracles; who, working for universal aims, found himself fed, he knew not how; clothed, sheltered, and weaponed, he knew not how, and yet it was done by his own hands. ...Shall we say, then, that transcendentalism is the Saturnalia or excess of Faith; the presentiment of a faith proper to man in his integrity, excessive only when his imperfect obedience hinders the satisfaction of his wish.

Importance of nature

Transcendentalists have a deep gratitude and appreciation for nature, not only for aesthetic purposes, but also as a tool to observe and understand the structured inner workings of the natural world.[4] Emerson emphasizes the Transcendental beliefs in the holistic power of the natural landscape in Nature:

In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life, — no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.[21]

The conservation of an undisturbed natural world is also extremely important to the Transcendentalists. The idealism that is a core belief of Transcendentalism results in an inherent skepticism of capitalism, westward expansion, and industrialization.[22] As early as 1843, in Summer on the Lakes, Margaret Fuller noted that "the noble trees are gone already from this island to feed this caldron,"[23] and in 1854, in Walden, Thoreau regards the trains which are beginning to spread across America's landscape as a "winged horse or fiery dragon" that "sprinkle[s] all the restless men and floating merchandise in the country for seed."[24]

Influence on other movements

Part of a series of articles on New Thought

Further information: History of New Thought

Transcendentalism is, in many aspects, the first notable American intellectual movement. It has inspired succeeding generations of American intellectuals, as well as some literary movements.[25]

Transcendentalism influenced the growing movement of "Mental Sciences" of the mid-19th century, which would later become known as the New Thought movement. New Thought considers Emerson its intellectual father.[26] Emma Curtis Hopkins "the teacher of teachers", Ernest Holmes, founder of Religious Science, Charles and Myrtle Fillmore, founders of Unity, and Malinda Cramer and Nona L. Brooks, the founders of Divine Science, were all greatly influenced by Transcendentalism.[27]

Transcendentalism also influenced Hinduism. Ram Mohan Roy (1772–1833), the founder of the Brahmo Samaj, rejected Hindu mythology, but also the Christian trinity.[28] He found that Unitarianism came closest to true Christianity,[28] and had a strong sympathy for the Unitarians,[29] who were closely connected to the Transcendentalists.[16] Ram Mohan Roy founded a missionary committee in Calcutta, and in 1828 asked for support for missionary activities from the American Unitarians.[30] By 1829, Roy had abandoned the Unitarian Committee,[31] but after Roy's death, the Brahmo Samaj kept close ties to the Unitarian Church,[32] who strived towards a rational faith, social reform, and the joining of these two in a renewed religion.[29] Its theology was called "neo-Vedanta" by Christian commentators,[33][34] and has been highly influential in the modern popular understanding of Hinduism,[35] but also of modern western spirituality, which re-imported the Unitarian influences in the disguise of the seemingly age-old Neo-Vedanta.[35][36][37]

Major figures

Margaret Fuller

Major figures in the transcendentalist movement were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and Amos Bronson Alcott. Some other prominent transcendentalists included Louisa May Alcott, Charles Timothy Brooks, Orestes Brownson, William Ellery Channing, William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke, Christopher Pearse Cranch, John Sullivan Dwight, Convers Francis, William Henry Furness, Frederic Henry Hedge, Sylvester Judd, Theodore Parker, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, George Ripley, Thomas Treadwell Stone, Jones Very, and Walt Whitman.[38]

Criticism

Early in the movement's history, the term "Transcendentalists" was used as a pejorative term by critics, who were suggesting their position was beyond sanity and reason.[39] Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a novel, The Blithedale Romance (1852), satirizing the movement, and based it on his experiences at Brook Farm, a short-lived utopian community founded on transcendental principles.[40]

Edgar Allan Poe wrote a story, "Never Bet the Devil Your Head" (1841), in which he embedded elements of deep dislike for transcendentalism, calling its followers "Frogpondians" after the pond on Boston Common.[41] The narrator ridiculed their writings by calling them "metaphor-run" lapsing into "mysticism for mysticism's sake",[42] and called it a "disease." The story specifically mentions the movement and its flagship journal The Dial, though Poe denied that he had any specific targets.[43] In Poe's essay "The Philosophy of Composition" (1846), he offers criticism denouncing "the excess of the suggested meaning... which turns into prose (and that of the very flattest kind) the so-called poetry of the so-called transcendentalists."[44]

See also

• Dark romanticism

• Immanentism

• Self-transcendence

• Transcendence (religion)

• Fruitlands

• The Machine in the Garden

Notes

1. Versluis: "In American Transcendentalism and Asian religions, I detailed the immense impact that the Euro-American discovery of Asian religions had not only on European Romanticism, but above all, on American Transcendentalism. There I argued that the Transcendentalists' discovery of the Bhagavad-Gita, the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other world scriptures was critical in the entire movement, pivotal not only for the well-known figures like Emerson and Thoreau, but also for lesser known figures like Samuel Johnson and William Rounsville Alger. That Transcendentalism emerged out of this new knowledge of the world's religious traditions I have no doubt."[17]

References

1. Goodman, Russell (2015). "Transcendentalism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Waldo Emerson."

2. Wayne, Tiffany K., ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism. Facts On File's Literary Movements. ISBN 9781438109169.

3. "Transcendentalism". Merriam Webster. 2016."a philosophy which says that thought and spiritual things are more real than ordinary human experience and material things"

4. Finseth, Ian. "American Transcendentalism". Excerpted from "Liquid Fire Within Me": Language, Self and Society in Transcendentalism and Early Evangelicalism, 1820-1860, - M.A. Thesis, 1995. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

5. Miller 1950, p. 49.

6. Versluis 2001, p. 17.

7. Finseth, Ian Frederick. "The Emergence of Transcendentalism". American Studies @ The University of Virginia. The University of Virginia. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

8. "George Putnam", Heralds, Harvard Square Library, archived from the original on March 5, 2013

9. Rose, Anne C (1981), Transcendentalism as a Social Movement, 1830–1850, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 208, ISBN 0-300-02587-4.

10. Gura, Philip F (2007), American Transcendentalism: A History, New York: Hill and Wang, p. 8, ISBN 978-0-8090-3477-2.

11. Stevenson, Martin K. "Empirical Analysis of the American Transcendental movement". New York, NY: Penguin, 2012:303.

12. Wayne, Tiffany. Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism: The Essential Guide to the Lives and Works of Transcendentalist Writers. New York: Facts on File, 2006: 308. ISBN 0-8160-5626-9

13. Sacks, Kenneth S.; Sacks, Professor Kenneth S. (2003-03-30). Understanding Emerson: "The American Scholar" and His Struggle for Self-reliance. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691099828. institutions.

14. Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "The Over-Soul". American Transcendentalism Web. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

15. "EMERSON--"THE AMERICAN SCHOLAR"". transcendentalism-legacy.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-14.

16. Versluis 1993.

17. Versluis 2001, p. 3.

18. Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. Boston: Ticknor&Fields, 1854.p.279. Print.

19. Lopez Jr., Donald S. (2016). "The Life of the Lotus Sutra". Tricycle Magazine (Winter).

20. Emerson, Ralph Waldo; Fuller, Margaret; Ripley, George (1844). "The Preaching of Buddha". The Dial. 4: 391.

21. Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Nature". American Transcendentalism Web. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

22. Miller, Perry, 1905-1963. (1967). Nature's nation. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674605500. OCLC 6571892.

23. "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Summer on the Lakes, by S. M. Fuller". http://www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

24. "Walden, by Henry David Thoreau". http://www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

25. Coviello, Peter. "Transcendentalism" The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 23 Oct. 2011

26. "New Thought", MSN Encarta, Microsoft, archived from the original on 2009-11-02, retrieved Nov 16, 2007.

27. INTA New Thought History Chart, Websyte, archived from the original on 2000-08-24.

28. Harris 2009, p. 268.

29. Kipf 1979, p. 3.

30. Kipf 1979, p. 7-8.

31. Kipf 1979, p. 15.

32. Harris 2009, p. 268-269.

33. Halbfass 1995, p. 9.

34. Rinehart 2004, p. 192.

35. King 2002.

36. Sharf 1995.

37. Sharf 2000.

38. Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007: 7–8. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8

39. Loving, Jerome (1999), Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself, University of California Press, p. 185, ISBN 0-520-22687-9.

40. McFarland, Philip (2004), Hawthorne in Concord, New York: Grove Press, p. 149, ISBN 0-8021-1776-7.

41. Royot, Daniel (2002), "Poe's humor", in Hayes, Kevin J (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, Cambridge University Press, pp. 61–2, ISBN 0-521-79727-6.

42. Ljunquist, Kent (2002), "The poet as critic", in Hayes, Kevin J (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, Cambridge University Press, p. 15, ISBN 0-521-79727-6

43. Sova, Dawn B (2001), Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z, New York: Checkmark Books, p. 170, ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

44. Baym, Nina; et al., eds. (2007), The Norton Anthology of American Literature, B (6th ed.), New York: Norton.

Sources

• Harris, Mark W. (2009), The A to Z of Unitarian Universalism, Scarecrow Press

• King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

• Kipf, David (1979), The Brahmo Samaj and the shaping of the modern Indian mind, Atlantic Publishers & Distri

• Miller, Perry, ed. (1950). The Transcendentalists: An Anthology. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674903333.

• Rinehart, Robin (2004), Contemporary Hinduism: ritual, culture, and practice, ABC-CLIO

• Sharf, Robert H. (1995), "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience" (PDF), Numen, 42 (3): 228–283, doi:10.1163/1568527952598549, hdl:2027.42/43810, archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-12, retrieved 2013-11-01

• Sharf, Robert H. (2000), "The Rhetoric of Experience and the Study of Religion" (PDF), Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7 (11–12): 267–87, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-13, retrieved 2013-11-01

• Versluis, Arthur (1993), American Transcendentalism and Asian Religions, Oxford University Press

• Versluis, Arthur (2001), The Esoteric Origins of the American Renaissance, Oxford University Press

Further reading[edit]

• Dillard, Daniel, “The American Transcendentalists: A Religious Historiography,” 49th Parallel (Birmingham, England), 28 (Spring 2012), online

• Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History (2007)

• Harrison, C. G. The Transcendental Universe, six lectures delivered before the Berean Society (London, 1894) 1993 edition ISBN 0 940262 58 4 (US), 0 904693 44 9 (UK)

• Rose, Anne C. Social Movement, 1830–1850 (Yale University Press, 1981)

• Versluis, Arthur (2001), The Esoteric Origins of the American Renaissance, Oxford University Press

External links

Topic sites

• The web of American transcendentalism, VCU

• The Transcendentalists

• "What Is Transcendentalism?", Women's History, About

• The American Renaissance and Transcendentalism

Encyclopediae

• "American Transcendentalism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

• "Transcendentalism", Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford}

Other

• Ian Frederick Finseth (1995), Liquid Fire Within Me: Language, Self and Society in Transcendentalism and early Evangelicalism, 1820-1860, M.A. Thesis in English, University of Virginia