by Wikipedia

Accessed: 10/12/22

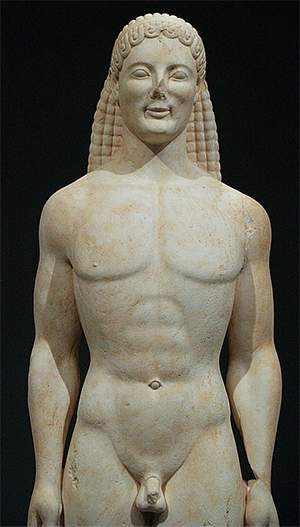

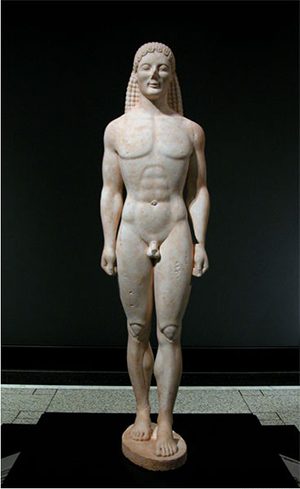

The Getty Kouros

The Getty kouros is an over-life-sized statue in the form of a late archaic Greek kouros.[1] The dolomitic marble sculpture was bought by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, in 1985 for ten million dollars and first exhibited there in October 1986.[2][3][4]

Despite initial favourable scientific analysis of the patina and aging of the marble, the question of its authenticity has persisted from the beginning. Subsequent demonstration of an artificial means of creating the de-dolomitization observed on the stone has prompted a number of art historians to revise their opinions of the work. If genuine, it is one of only twelve extant complete kouroi. If fake, it exhibits a high degree of technical and artistic sophistication by an as-yet unidentified forger. Its status has remained undetermined: latterly the museum's label read "Greek, about 530 B.C., or modern forgery".[5] Although the statue was removed from public display after the 2018 renovations, Dr. Timothy Potts, the current director of the Getty, reinforces that the kouros has still not been confirmed of its authenticity. Dr. Potts states that the sculpture was taken off of display due to the dubious nature around the work.[6]

Provenance

The kouros first appeared on the art market in 1983 when the Basel dealer Gianfranco Becchina offered the work to the Getty's curator of antiquities, Jiří Frel.

In the early 1980s, the antiquities department at the J. Paul Getty Museum was a hotbed of whispered political intrigue. Rumors swirled that the department’s Czech curator, Jiri Frel, was a Communist spy. And many believed the deputy curator, former State Department official Arthur Houghton, was a CIA plant tasked with keeping an eye on Frel’s activities....

As for Houghton and his ties to the CIA, the rumors were not far off. Before coming to the Getty in 1982, he had spent a decade working for the State Department, including time in its bureau of intelligence and research as a Mid East analyst. Houghton was fond of cultivating his image as a man of mystery. In truth, he had burned out on the diplomatic bureaucracy and chose a career that brought him closer to his long time passion — ancient coins. Houghton remains active in the field to this day.

-- Jiri Frel: Scholar, Refugee, Curator…Spy?, by Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino

Frel deposited the sculpture (then in seven pieces) at Pacific Palisades along with a number of documents purporting to attest to the statue's authenticity. These documents traced the provenance of the piece to a collection in Geneva of Dr. Jean Lauffenberger who, it was claimed, had bought it in 1930 from a Greek dealer. No find site or archaeological data was recorded. Amongst the papers was a suspect 1952 letter allegedly from Ernst Langlotz, then the preeminent scholar of Greek sculpture, remarking on the similarity of the kouros to the Anavyssos youth in Athens (NAMA 3851). Later inquiries by the Getty revealed that the postcode on the Langlotz letter did not exist until 1972, and that a bank account mentioned in a 1955 letter to an A.E. Bigenwald regarding repairs on the statue was not opened until 1963.[7]

The documentary history of the sculpture was evidently an elaborate fake and therefore there are no reliable facts about its recent history before 1983. At the time of acquisition, the Getty Villa's board of trustees split over the authenticity of the work. Federico Zeri, founding member of board of trustees and appointed by Getty himself, left the board in 1984 after his argument that the Getty kouros was a forgery and should not be bought was rejected.[8][9]

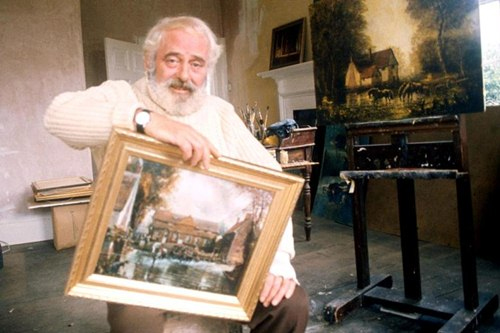

[Narrator] But Peter Nahum wasn't the only person who was suspicious. The cracks in Myatt and Drewe's con were beginning to show.

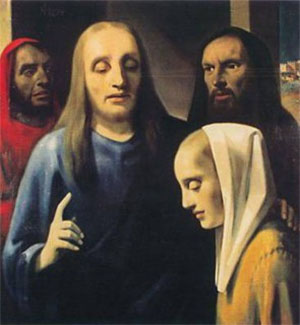

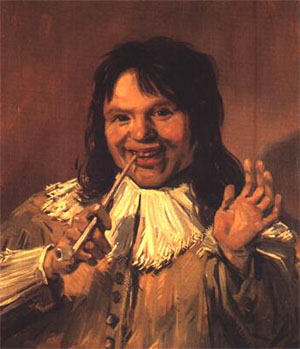

[Narrator] Giacometti was a Swiss Italian artist who moved to Paris, France in 1922. The Giacometti Institute in Paris is responsible, among other things, for cataloguing the artist's work, as well as uncovering and stopping would-be forgers. Mary Lisa Palmer, the director of the Giacometti Association, had been sent a catalogue by Sotheby's in the UK, featuring a Giacometti standing nude. She instantly questioned its authenticity.

[Mary Lisa Palmer, Director, Giacometti Association] The painting that I saw was inconsistent. Like, the head looked like a man's head on a woman's body; the background was poor; the strokes were wishy-washy. When an artist paints, there's a lot of energy that goes into the painting. When a person copies, he's copying the work of somebody else. It's not at all the same energy in the painting itself. Then it was signed, also; and the signature resembled other fake signatures, and not the real signature. When Albert Giacometti used to sign, he would sign quickly, you know. Get rid of it! He didn't like to sign paintings or drawings, so he did it quickly. The signature is very applied, you know, so copied. So I went to London to look at the work. I looked at the front of the canvas, the back of the canvas. I asked for an X-ray. Then I told the people at Sotheby's that I thought it was a fake. And then they told me, "But, ah -- there are experts that think that it's okay, and you will find documents at the Tate gallery proving the provenance as being correct." So I went to the Tate Gallery to look at these documents. I did see a photograph of this painting slipped into the Tate Gallery archives. And from that moment on, I felt that they were being tampered with. Basically, if the painting was fake, then the provenance had to be fake. Well, I sort of had to play the detective part, because people would not believe that the provenance was fake, because they were "very well done," quote unquote. I had to try to prove that the paper was not from the 50s. So I had to look at the watermarks, and contact the paper companies. I had to check with the libraries whether this catalogue was in their archives. I had to write to the printers, to see if they printed the catalogue. I had to check with another foundation whether they had received the same provenance material. And I found out that they had a different date for the same catalogue. I also wrote to the post office in England to see if the stamps were used in the 50s. I went on and on and on in this sort of detail.

[Narrator] That sort of detail resulted in Mary Lisa Palmer's success. Experts confirmed that the paper used in the suspected fake catalogues was not from the 1950s, as they stated. She now had evidence that the provenance was corrupt.

-- Inside Criminal Minds ... Con Men, [The Cunning Genius Who Fooled The Art World: John Myatt], Narration by Anthony Wilson

Stylistic analysis

The Getty kouros is highly eclectic in style. The development of kouroi as delineated by Gisela Richter[10] suggests the date of the Getty youth diminishes from head to feet: At its top, the hair is braided into a wig-like mass of 14 strands, each of which ends in a triangular point. The closest parallel here is to the Sounion kouros (NAMA 2720) of the late 7th century/early 6th century, which also displays 14 braids, as does the New York kouros (NY Met. 32.11.1). However, the Getty kouros's hair exhibits a rigidity, very unlike the Sounion Group. Descending to the hands, the last joints of the fingers turn in at right angles to the thighs, recalling the Tenea kouros (Munich 168) of the 2nd quarter of the 6th century. Further down, a late archaic naturalism becomes more pronounced in the rendering of the feet similar to kouros No. 12 from the Ptoon sanctuary (Thebes 3), as is the broad oval plinth which in turn is comparable to a base found on the Acropolis. Both Ptoon 12 and the Acropolis base are assigned to the Group of Anavyssos-Ptoon 12 and dated to the third quarter of the 6th century. Anachronizing elements are not unknown in authentic kouroi, but the disparity of up to a century is a strikingly unusual feature of the Getty sculpture.

Technical analysis

Side view of the kouros

Despite being of Thasian marble, the kouros cannot be securely ascribed to an individual workshop of northern Greece nor indeed to any ancient regional school of sculpture. Archaic kouroi conform to a canon of measurement and proportion (albeit with strong local accents) to which the Getty example also adheres; a comparison of like elements in other kouroi is both a test of authenticity and additional clue to the origin of the sculpture. There is little in the tool marks, carving methods and detailing to contradict an ancient origin of the piece. Although there is a small sample with which to compare (some 200 fragments and only twelve complete statues of the same type) there are atypical aspects of the Getty work that may be observed. The oval plinth is an unusual shape and larger than in other examples, suggesting the figure was free-standing rather than fixed with lead in a separate base. Also, the ears are not symmetrical: they are at different heights with the left oblong and the right rounder, implying the sculptor was using two distinct schema or none at all.[11] Furthermore, there are a number of flaws in the marble, most prominently on the forehead, which the sculptor has worked around by parting the hair curls at the centre; ancient examples survive of projects being abandoned by sculptors when such flaws in the stone were revealed.[12]

Frontal view

Perhaps the most striking evidence suggestive of the kouros's antiquity is a subtlety regarding the direction of motion of the figure. Even though the youth presents square to the viewer, all kouroi have understated indicators of a turn either to the left or the right depending on where they were originally placed in the temple sanctuary; i.e., they would seem to turn towards the naos. In the case of the Getty youth the left foot is parallel with the step axis of the right foot rather than turning outwards as would occur if the figure were moving directly forwards. Therefore, the statue is making motion toward his right, which Ilse Kleemann asserts is "one of the strongest pieces of evidence of its authenticity".[13] Other features that suggest a similarity with known originals include the helicoid curls of the hair, closest in form to the west Cyclidian Kea kouros (NAMA 3686), the Corinthian form of the hands and the sloping shoulders akin to the Tenea kouros and the broad plinth and feet comparable to the Attic or Cyclidian Ptoon 12. That the Getty kouros cannot be identified with any one local atelier does not disqualify it as a genuine, but if real it admits a lectio difficilior into the corpus of archaic sculpture.

Lectio difficilior potior (Latin for "the more difficult reading is the stronger") is a main principle of textual criticism. Where different manuscripts conflict on a particular reading, the principle suggests that the more unusual one is more likely the original. The presupposition is that scribes would more often replace odd words and hard sayings with more familiar and less controversial ones, than vice versa.

-- Lectio difficilior potior, by Wikipedia

Some indication of tool marks remain on the work. Though the surface is weathered (or artificially abraded) and it is not clear if emery was used, there are heavy claw marks on the plinth and the use of a point in some of the finer detailing. For example, there are point marks in the outline of the curls, between the fingers and in the cleft of the buttocks, also traces of the point in the arches of the feet and at random over the plinth. Though the tools evident here (fine point, slope chisel, claw chisel) are not inappropriate for a late 6th century sculpture their application might be problematic. Stelios Triantis remarks, "no sculptor of kouroi would hollow out with a fine point, nor incise outlines with this tool".[14]

In 1990, Dr. Jeffrey Spier published the discovery of a kouros torso,[15] a certain forgery that exhibited notable technical similarities to the Getty kouros. After samples were taken that determined the fake torso was of the same dolomitic marble as the Getty piece, the torso was purchased by the museum for study purposes. The fake's sloping shoulders and upper arms, volume of chest, rendering of the hands and genitals all suggest the same hand as the Getty's example, although the aging had been crudely done with an acid bath and the application of iron oxide. Further investigation has shown the torso and the kouros are not from the same block and the sculpting techniques are dramatically different (down to the use of power tools on the torso).[16] Their relationship if any is still to be determined.

[T]o these four considerations one might add one final point, that of seriality. Seriality and repetitiveness can often be identified as markers of forgery. Forgers often fabricated more than one sample of their counterfeit products, which may now be inadvertently considered to be genuine artifacts in different parts of the world. For instance, in archaeological museums. So, of course, there are inscriptions which were produced in more than one copy in ancient times, but generally speaking, one should always be cautious when identical, or even slightly different texts, can be found on different physical objects. And this final aspect was already remarked in the 1990s when a similar tablet was detected by a colleague, Antonio Sartori, who saw it on sale in a shop in Paris. This second tablet was sold on the antiquarian market, so we don't know where it is today. And we only have a cast of it on kitchen foil, which was made for my colleague by the art dealer. Actually, a long investigation carried out both in libraries and in museums across Europe, has led me to discover that the copies of this inscribed tablet are not only two, but several. Some of them are still existing, while others are known only through manuscript tradition. So far, aside from the Tortello Tablet, and the lost Paris Tablet, I was able to locate three more copies of the same inscription. One in Arezzo, one in Madrid, and one more in Basel. To these three objects, one may add some others, which were published in different parts of the CIL of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, where they were unanimously judged as forged. In particular, the Eleventh volume of the Corpus, published by Eugen Bormann, and devoted two inscriptions from Aemilius ... and Etruria -- so from central and northern Italy -- is very rich with information. Bormann had spotted a group of nine small bronze tablets inscribed with different texts in Bologna. That's the entry that you're looking at now. And he defined them -- and I'm translating from the Latin -- several bronze tablets inscribed with false copies of genuine inscriptions: the tabellae aereae inscriptae exemplis falsis titulorum genuinorum. Well, he mentioned that he had personally seen them in the archaeological museum in Bologna, while formerly they belonged to the university collection of the same city. And you can see among these inscriptions -- in the fifth position -- a copy of the dedication to Druso. Unfortunately, despite numerous attempts, it has been impossible to locate this group of tablets.

-- Epigraphic Criticism and the Study of Forgeries: A Historical Perspective, by Lorenzo Calvelli

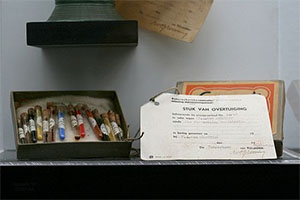

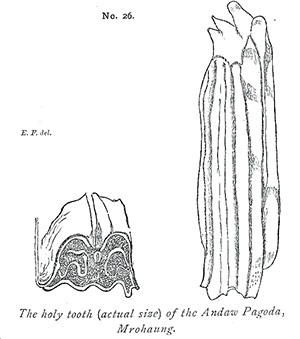

Archaeometry

The Getty commissioned two scientific studies on which it based its decision to buy the statue. The first was by Norman Herz, a professor of geology at the University of Georgia, who measured the carbon and oxygen isotope ratios, and traced the stone to the island of Thasos. The marble was found to have a composition of 88% dolomite and 12% calcite, by x-ray diffraction. His isotopic analysis revealed that δ18O = -2.37 and δ13C = +2.88, which from database comparison admitted one of five possible sources: Denizli, Doliana, Marmara, Mylasa, or Thasos-Acropolis. Further, trace element analysis of the kouros eliminated Denizli. With the high dolomite content Thasos was determined to be the likeliest source with a 90% probability.[17] The second test was by Stanley Margolis, a geology professor at the University of California at Davis. He showed that the dolomite surface of the sculpture had undergone a process called de-dolomitization, in which the magnesium content had been leached out, leaving a crust of calcite, along with other minerals. Margolis determined that this process could occur only over the course of many centuries and under natural conditions, and therefore could not be duplicated by a forger.

In the early 1990s, the marine chemist Miriam Kastner produced an experimental result which cast doubt on Margolis's thesis by artificially inducing de-dolomitization in the laboratory, a result since confirmed by Margolis. Although this does admit the possibility that the kouros was synthetically aged by a forger, the procedure is a complicated and time-consuming one. The unlikeliness of a forger using such experimental methods in what is still an uncertain science has prompted the Getty's antiquities conservator to remark "when you consider a forger actually repeating the procedure you begin to leave the realm of practicality".[18]

[Narrator] The Museum of ancient art in Basel is the only Museum in Switzerland to exhibit exclusively classical antiques. The two sculptures Stephan Lehmann believes to be highly suspicious, stood here, considered stars of the exhibition. Museum Director Andrea Bignasca has sent one of them to the workshop to have it examined once again by conservators.

[Music] The museum received the sculptures as part of a private legacy gift from the Ludwig Collection in Aachen. Stephan Lehmann thinks the sculpture is the work of the Spanish master.

[Andrea Bignasca, Basel Museum of Ancient Art] I have to say, this all surprised me. We didn't know that Lehmann was conducting such investigations, and that he had included our two bronze sculptures from the Ludwig Collection.

[Narrator] Their former owners Peter and Irene Ludwig, collected art and acquired this bronze sculpture on the art market. But the Museum has no information about exactly where it comes from. The idea of classical works with no known origin, or provenance, making their way into public museums via the art market, is something Stefan Lehmann deplores.

[Andrea Bignasca, Basel Museum of Ancient Art] Herr Lehmann is a classical archeologist. He's a professor at a university. He's a curator at the Archaeological Museum. But he's no specialist in bronze statues, although he seems to think so. What I don't like in this case is this broadside on me personally, on the Museum, on my colleagues. So far, there's absolutely no proof. So, I'm sticking to the version that these objects are original, classical, works of art.

[Stefan Lehmann, Archaeologist] Yes, of course, the museums are never amused -- obviously -- when important artifacts that are shown in their main chamber are cast into doubt. It always leads immediately to personal differences. That's normal. You can't avoid that entirely. But I think the question of whether they are original sculptures, or modern forgeries, is so important, that we have to be above these trifles.

[Narrator] Back at the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft Institute, preparations are underway for a second scan of the Swiss collector's Augustus. After the failure of the first attempt to get a CT scan, Material Scientist Harold Miller is now getting the bronze head x-rayed again in Europe's most powerful linear accelerator. Until now, no Museum collector was prepared to hand over a suspected forgery for such an examination. So no work ascribed to the Master has yet been proved fake by these scientific methods.

The scientists have to leave the hall, because of the extremely high radiation from the linear accelerator. The examination is focused on the metal alloy in the bronze sculpture. Is it really from antiquity? Does it have the same characteristics as a bronze statue made 2,000 years ago? one suspicion is that the forgers melt down ancient coins to cast new heads -- a clever approach.

[Man] What is this device?

[Harold Muller, Materials Scientist] It's a Perkin Elmer Detector, with 200 micrometer pixel pitch. We believe, because of a range of material characteristics that correspond with antiquity, that this sculpture is made of genuine ancient material. There is ancient material available for things like this, and it would not be an entirely new idea to use, or to have used, old material for forgeries.

[Narrator] This time, the process works. Muller looks at the cross-sectional images of the head, and he notices that the patina on the head is only on the outside surface. That's strange.

[Harold Muller, Materials Scientist] You can see that that this material has a different density from the material around it, which has a different alloy composition. We've carried out metallographic tests, meaning on a cross-section of the material, and the outer crust, and determined, for one thing, that the corrosion, which looks very bad to the naked eye, is only on the surface. That leads us to the conclusion that this artefact was created in modern times, and designed to look very old.

-- The Mystery Conman: The Murky Business of Counterfeit Antiques, directed by Sonje Storm

See also

• List of artworks with contested provenance

References

1. Getty Villa, Malibu, inv. no. 85.AA.40.

2. Thomas Hoving. False Impression, The Hunt for Big-Time Art Fakes, 1997, p. 298.

3. Sorensen, Lee. Frel, Jiří K. In The Dictionary of Art Historians. Accessed 28/8/2008.

4. MICHAEL KIMMELMAN. [1] In "ART; Absolutely Real? Absolutely Fake?". Accessed 26/1/2014

5. J. Paul Getty Museum. Statue of a kouros. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

6. L.A. Times Review: Something’s missing from the newly reinstalled antiquities collection at the Getty Villa retrieved 03/05/2020.

7. Marion True. The Getty Kouros: Background on the Problem, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993, p. 13.

8. Hanley, Anne (1998-10-07). "Obituary: Federico Zeri". The Independent. Retrieved 2014-01-09.

9. "Zeri, Federico". Dictionary of Art Historians. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

10. G.M.A. Richter. Kouroi: Archaic Greek Youths. A Study of the Development of the Kouros Type in Greek Sculpture. 1970.

11. I. Trianti. Four Kouroi in One?, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993.

12. In the quarries of Naxos at Apollonas, Melanes and Flerio.

13. Ilse Kleemann, On the Authenticity of the Getty Kouros, in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, 1993, p. 46

14. Stelios Triantis. Technical and Artistic Deficiencies of the Getty Kouros in The Getty Kouros Colloquium, p. 52.

15. J. Spier. "Blinded by Science", The Burlington Magazine, September 1990, pp. 623–631.

16. Marion True, op. cit, pp. 13–14.

17. Norman Herz and Marc Waelkens. Classical Marble, 1988, p. 311.

18. Michael Kimmelman Absolutely Real? Absolutely Fake?, NYT, August 4th, 1991. Accessed 29/8/2008

Sources

• Bianchi, Robert Steven (1994). "Saga of the Getty Kouros". Archaeology. 47 (3): 22–23. JSTOR 41766561.

• Podney, J. (1992). A Sixth Century B.C. Kouros in the J. Paul Getty Museum. J. Paul Getty Museum.

• Kokkou, A, ed. (1993). The Getty Kouros Colloquium: Athens, 25-27 May 1992. J. Paul Getty Museum.

• Herz, N.; Waelkens, M. (1988). Herz, Norman; Waelkens, Marc (eds.). Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-015-7795-3. ISBN 978-90-481-8313-5.

• Spier, Jeffrey (1990). "Blinded by Science: The Abuse of Science in the Detection of False Antiquities". The Burlington Magazine. 132: 623–631. JSTOR 884431.

• True, Marion (1987). "A Kouros at the Getty Museum". The Burlington Magazine. 129 (1006): 3–11. JSTOR 882884.

***********************

The “Getty Kouros” was removed from view at the museum after it was officially deemed to be a forgery.

by Isaac Kaplan

via The New York Times

Apr 16, 2018 9:38AM

The authenticity of the kouros (a freestanding Greek sculpture of a naked youth) has been debated since the Getty acquired the object in the mid-1980s for around $9 million. Despite the controversy, the work remained on view at the Los Angeles museum, next to a plaque reading “Greek, about 530 B.C. or modern forgery,” the New York Times reported. But it will no longer be up to viewers to weigh whether the object is authentic or not. Following a renovation of the Getty Villa, the sculpture was moved to storage where it will be on view by appointment only. “It’s fake, so it’s not helpful to show it along with authentic material,” said Getty director Timothy Potts. The removal is the final chapter in a decades-long saga that began when the Getty museum performed a battery of scientific tests on the piece to confirm its authenticity prior to purchase, only to buy the work and watch the faith in its authenticity slowly erode over time, the Times reported in 1991. A chemical process that occurred on the exterior of the sculpture led scientists to believe the work must have been centuries old, but such a reaction was actually shown to be replicable in a lab.The additional investigation came after an indisputably fake torso similar to that of the Getty Kouros was discovered, causing some experts to reverse their position on the authenticity of the piece.

[T]o these four considerations one might add one final point, that of seriality. Seriality and repetitiveness can often be identified as markers of forgery. Forgers often fabricated more than one sample of their counterfeit products, which may now be inadvertently considered to be genuine artifacts in different parts of the world. For instance, in archaeological museums. So, of course, there are inscriptions which were produced in more than one copy in ancient times, but generally speaking, one should always be cautious when identical, or even slightly different texts, can be found on different physical objects. And this final aspect was already remarked in the 1990s when a similar tablet was detected by a colleague, Antonio Sartori, who saw it on sale in a shop in Paris. This second tablet was sold on the antiquarian market, so we don't know where it is today. And we only have a cast of it on kitchen foil, which was made for my colleague by the art dealer. Actually, a long investigation carried out both in libraries and in museums across Europe, has led me to discover that the copies of this inscribed tablet are not only two, but several. Some of them are still existing, while others are known only through manuscript tradition. So far, aside from the Tortello Tablet, and the lost Paris Tablet, I was able to locate three more copies of the same inscription. One in Arezzo, one in Madrid, and one more in Basel. To these three objects, one may add some others, which were published in different parts of the CIL of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, where they were unanimously judged as forged. In particular, the Eleventh volume of the Corpus, published by Eugen Bormann, and devoted two inscriptions from Aemilius ... and Etruria -- so from central and northern Italy -- is very rich with information. Bormann had spotted a group of nine small bronze tablets inscribed with different texts in Bologna. That's the entry that you're looking at now. And he defined them -- and I'm translating from the Latin -- several bronze tablets inscribed with false copies of genuine inscriptions: the tabellae aereae inscriptae exemplis falsis titulorum genuinorum. Well, he mentioned that he had personally seen them in the archaeological museum in Bologna, while formerly they belonged to the university collection of the same city. And you can see among these inscriptions -- in the fifth position -- a copy of the dedication to Druso. Unfortunately, despite numerous attempts, it has been impossible to locate this group of tablets.

-- Epigraphic Criticism and the Study of Forgeries: A Historical Perspective, by Lorenzo Calvelli

Further investigation revealed that the curator who presented the kouros to the Getty for purchase forged the accompanying provenance documents.