by Dieter Koch

2014/2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

A very good example for a mixture of old and new astronomical concepts is given in chapter 2.8 of the Viṣṇupurāṇa. Experts agree that this work was compiled in post-Hellenistic times (3rd/4th cent. AD). In VP 2.8.28ff. (quoted on p. 41f.), it is stated that the solstices are at the initial points of Capricorn and Cancer and the equinoxes at the initial points of Aries and Libra. This statement clearly stems from post-Hellenistic times, from the first half of the 1st millennium CE. However, later in the same chapter, in VP 2.8.76-79 (quoted below on p. 27f.), it states that when the Sun is in the third quarter of Viśākhā and the full moon in the first quarter of Kṛttikā, then that is the autumnal equinox. This statement is only valid for the 2nd millennium BCE. Thus, there is obviously very old and very young material mixed together in this text....

The list of nakṣatras, as known today and as found in astronomical works of the post-Hellenistic period, begins with Aśvinī. However, in lists given in the Purāṇas, the Mahābhārata, and in Brāhmaṇa texts, Kṛttikā appears in the first place (e. g. MBh 13.63(64).5ff.) Kṛttikā is more frequently mentioned than any other lunar mansion. It seems that Kṛttikā, as well as Maghā, which is approximately in square to Kṛttikā, were of exceptional importance. The reason seems to be that in ancient times the vernal equinox was in Kṛttikā and the summer solstice in Maghā; or otherwise the fact that the full moon, when it occurred in Kṛttikā, roughly coincided with the autumn equinox, and the full moon in Maghā with the winter solstice. In principle, this explanation allows an astronomical dating of this calendrical system, although not necessarily a dating of the texts that refer to it. As has been said already, the doctrine could be a lot older that the written documents in which it first appears...

An interesting text that mentions the equinoxes, which even Venkatachelam quotes, although he fails to recognize its real significance, is found in Viṣṇupurāṇa 2.8., and with some variations also in Brahmāṇdapurāṇa 1.21 and Vāyupurāṇa 50:

When the Sun is in the first part of Kṛttikā, then the [full] moon

stands in the forth (read: third) part of Viśākhā without any doubt.

When the Sun enters the third part of Viśākhā,

then one should know that the [full] moon stands at the beginning of Kṛttikā.

Then this is the holy time which is called the “equinox”.

Then [people] of devoted nature give gifts to the gods (var. to the ancestors).

By means of the Sun the equinox must be known, the time must be indicated by means of the Moon.

Night and day are equal, when this equinox takes place.

For Brahmins and ancestors, this is the beginning (mouth) that generates gifts.

Whoever has given gifts on the equinox, becomes one who has done [everything] that ought to be done.

While the Viṣṇupurāṇa might have been composed in the Christian era, there can be no doubt that the astronomical observations underlying the above verses date to the first half until the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE. Besides, the work turns out to be a conglomerate of doctrines from very different epochs. For, right in the same chapter, VP 2.8.28ff., it is mentioned that the solstices are at the initial points of Capricorn and Cancer. These verses are post-Hellenistic and were obviously written in the first half of the 1st millennium CE. Astronomically speaking, there are 2000 years between this passage and the one quoted above.

What is interesting about the cited text is that the lunar mansions are divided into four parts and that a circle of 27 (not 28) equal lunar mansions seems to be used. For, in a circle of 27 lunar man-sions, the first quarter of Kṛttikā stands in opposition to the third quarter of Viśākhā. (The fact that verse 76 mentions the fourth part must be an error, as becomes obvious from verse 77.) When the full moon takes place on the equinox, then the Sun and the Moon were found on this axis. Now, if it were known exactly where the starting point of the nakṣatra circle was assumed, these verses could be dated with a precision of 240 years. Unfortunately, this is not known. However, as has been stated, if the sidereal zodiac according to Lahiri is assumed, where the star Citrā (= Spica) is in the middle of the lunar mansion Citrā, then it results in a fairly reasonable distri-bution of the principal stars in their respective lunar mansions. Thus if the Lahiri zodiac is used as an approximation, then this astro-nomical observation from the Viṣṇupurāṇa can be dated to about 1885 – 1645 BCE....

There is also the following verse, which is found in different ver-sions in several Purāṇas:

When the Sun is in Śravaṇa [reaching] northern culmination,

then he wanders rising in the northern regions of the sixth continent [called] Śakadvīpa.

When the Sun is in Śravaṇa and Uttarāṣāḍhā,

then he wanders in the northern regions of the sixth continent [called] Śakadvīpa.

When the Sun is [reaching] northern culmination in [the month of] Śrāvaṇa,

then he wanders in the most northern region on the continent of Gomeda.

The former two versions wrongly state that the Sun reaches his northern culmination in Śravaṇa. In reality, that would be his south-ern culmination. The third version is more correct in that it mentions the month of Śrāvaṇa rather than the lunar mansion Śravaṇa. But whatever may be the original wording of the text, it clearly points to an epoch where the winter solstice was in Śravaṇa or Śraviṣṭhā, the two lunar mansions whose full moons were assigned to the month of Śrāvaṇa. As has been stated already, the solstice was at the beginning of Śravaṇa around 440 BCE, and at the beginning of Śraviṣṭhā around 1400 BCE...

A good example for a post-Hellenistic definition of the zodiac, the equinoxes, and the solstices is found in Viṣṇupurāṇa 2.8.28ff.:

At the beginning of his northward course (uttarāyaṇam), the Sun enters Capricorn, then [he enters] Aquarius and Pisces, from one zodiac sign to the other, O twice-born one.

After enjoying these three [zodiac signs], the Sun arrives at the equinox and makes day and night equal.

Then the night goes to decrease and the day grows daily.

And then, at the end of Gemini, the Sun arrives at his highest culmination. When he has reached Cancer, he makes the southward course (dakṣiṇāyanam).

This definition, which is actually equivalent to the tropical zodiac, as found in Ptolemy’s works, was valid for several centuries in India. It is found in Purāṇas and in all works of astronomy and astrology of the post-Hellenistic period, including the works of Sphujidhvaja, Varāhamihira, Āryabhaṭa and in Sūryasiddhānta.42 “Vedic” astro-logers do not like to hear all this, because they want to believe that Indian astrology as we know it today was revealed more than 5000 years ago by the holy sages of Vedic times and that their doctrines from the beginning were not tropical, but sidereal....

There are also other texts in Purāṇas that explain the daily rotation of the stars about the pole star (or the celestial pole) by the fact that they are tied to it by “wind strings” and that their circular motion is caused by the rotation of the pole star. Some scholars believe that these texts also prove a scientific understanding of the precession of the equinox in Vedic times. However, if the texts are studied more closely, this turns out to be wishful thinking. In reality these texts only deal with the daily rotation of the sky, not with precession. Other than the above-cited text from Maitryupaniṣad, they are not aware of precession...

Also, Dhruva is called a star in the tail of Śiśumāra in several places in Purāṇas, e.g. in the following verse:

After Dhruva, the son of Uttānapāda, had propitiated that lord of the world, he was placed into the tail of the constellation Śiśumāra....

Finally, Jha refers to the mysterious doctrine of the vīthīs in Vāyupurāṇa 50, which in his view alludes to the trepidation theory. His argument is as follows:

Verse-130 states that Sun's path during the Uttarāyana is called Nāgaveethee, and Sun's path during the Dakshināyana is called Ajaveethee. When Sun rises in three nakṣatras from moola to (poorva and uttara) āshādha, it is ajaveethee, and when the Sun rises in three nakshatras from Abhijit (i.e., Abhijit or Shravana or Dhanishthā), then it is Nāgaveethee.

What does it mean? Uttarāyana and Dakshināyana are here defined not in terms of human Sunrise or Sunset, but divine Sunrise and Sunset. Divine Sunrise occurs when sāyana Sun has longitudes from -27 deg to +27 deg with respect to the mean reference point 270 deg for Mean Divine Sunrise

or Uttrāyana-onset, i.e., from 243 deg (Moola) to 297 deg (Uttarāshādha) which is an evidence of both pendulum like motion of Dhruva as well as of trepidating ayanāmsha known as Dolāyana in contrast to circular motion of modern concept of ayanāmsha known as chakrāyana. Although exact degrees are not mentioned in these verses, no other explanation is possible excepting that based on trepidating Dolāyana, which puts nir-ayana Makara Samkrānti or Divine Sunrise always at 270 degrees and sāyana Makara Samkrānti from 243 deg to 297 deg...

Thus Jha believes that ajavīthī (the “path of the goats”) and nāgavīthī (the “path of the snakes”) represent the two sections of the ecliptic that lie on either side of the initial point of sidereal Capricorn and have the size of 27° each. According to the trepidation theory, which is a precursor of the theory of precession, the winter solstice oscillates within this range in a period of 7200 years. Since Jha defines uttarāyaṇa and dakṣiṇāyana sidereally, the two vīthīs always fall in opposite half-years or ayanas. And since the two vīthīs comprise 27° each, the solstitial point necessarily falls into some lunar mansion between Mūla and Dhaniṣṭhā. Jha therefore assigns the area of Mūla, Pūrvāṣāḍhā, and Uttarāṣāḍhā to ajavīthī, and the area of Abhijit, Śravaṇa and Dhaniṣṭhā to nāgavīthī. The text thus alludes to the trepidation theory, in Jha’s opinion.

In reality, however, the text does not support this. The wording is as follows:

The nāgavīthī is northerly and the ajavīthī southerly.

Mūla and the two Āṣāḍhās are the three risings of/in the ajavīthī.

Abhijit ... before ... Svāti are the three risings of/in the nāgavīthī.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to make sense out of the last line. The text is obviously corrupt. However, it is obvious that there is no mention of the triple Abhijit, Śravaṇa und Dhaniṣṭhā, and one would have to adjust the text considerably in order to make it accord with this idea. Jha’s translation shows that he does “correct” the text somehow, but he does so silently without mentioning the problem:

Northern veethee or path is Nāgaveethee and southern veethee is Ajaveethee. Sunrise (occurs) in any of three nakshatras from moola to both āshādhas which make up Ajaveethee. (And) sunrise (occurs) in any of three nakshatras likewise from Abhijit (to shravana and dhanishthā) which make up Nāgaveethee.

It must be noted that Jha suppresses the mention of Svāti, which obviously contradicts his interpretation...

In Harivaṃśa, the following verses are found:

The creatures will go into destruction together with the Kali age.

When this Kali age has been destroyed, then a new Kṛta age

will emerge, according to the rule, by nature, not otherwise.

The context of this verse treats the incarnations of Viṣṇu on the earth at the end of each yuga. And in Viṣṇupurāṇa it says:

Kṛtam, Tretā, Dvāparaḥ und Kaliḥ [form] a [period] of four ages.

One thousand of them is called a day of Brahmā, O sage.

In one day of Brahmā, O Brahmin, 14 Manus

appear. Listen [to learn] their change that is caused by time (Kāla).

The Seven Ṛṣis, the gods, Śiva, Manu, his sons, and the kings

are created and destroyed at the same time, as they were formerly.

The four ages Kṛta, Tretā, Dvāpara, and Kali, constitute a “great age” (mahāyugam, caturyugam). One thousand of them form a “Day of Brahmā”, the “Creator God”. A day of Brahmā also contains 14 Manu periods (manvantaram), each of which contains 71 “great ages”. Manu is the name of the ruler of one of these 14 periods. At the end of a Manu period, the Manu dies, and a new one takes office. The verse quoted above actually seems to indicate that the divine beings are destroyed and recreated at the beginning of each Manu period.

However all that may be in detail, it is obvious that the super-conjunction of all planets has something to do with this reabsorption of everything into God and its re-emanation from him at the end of each age. Everything, including the planets, are absorbed into God and re-emerge from him.

The Viṣṇupurāṇa has the following verses:

The yogis who contemplate Brahma, having one goal only,

to them [belongs] that highest abode that is seen by the sages.

The Moon, the Sun, and the other planets go there again and again and return [at the end of each yuga].

Even today, those who meditate on the 12 syllables, do not return.

The last line refers to the spiritual liberation that ends the cycle of birth and death.

It seems, however, that the planets unite in a super-conjunction at the end of each yuga, not only at the end of a day of Brahmā and not only at the end of a Manu period or a great age (mahāyuga)...

Thus at the time the world reaches destruction, the planets are swallowed up by Nṛsiṃha, who represents the Sun, and shortly thereafter proceed to their combined heliacal rising. They go forth from a conjunction, then separate and wander separately “as they please”...

As has been illustrated, The Mahābhārata epic contains clear evidence that a super-conjunction of all planets took place at the time of the great war. However, the traditional belief amongst Hindu astrologers is that a super-conjunction did not occur in the year of the war, but 36 years later, in the year when Kṛṣṇa died and the kali-yuga began. The date given for this event is 17th/18th February 3102 BCE. The astronomical configuration for this traditionally accepted kaliyuga date will be examined shortly. However, it should first be considered whether a super-conjunction 36 years after the war could be derived from textual evidence within the Mahābhārata itself.

To begin with, the Mahābhārata itself states that the super-conjunction and the transition from dvāparayuga to kaliyuga took place during the year of the war. This is evident from the following verse:

When the transition of Kali and Dvāpara arrived,

the battle between the two armies of the Kurus and Pāṇḍavas took place in Kurukṣetra (Samantapañcaka).

Another passage reads as follows:

When you see [Arjuna] in battle with white horses, with Kṛṣṇa as his charioteer,

wielding the weapons of Indra, Agni, and the Maruts,

and the thunder-like roaring sound of [his bow] Gaṇḍīva,

then tretā-, kṛta-, and dvāparayuga will be over.

When you see Kuntī’s son Yudhiṣṭhira in battle,

devoted to Japa and Homa and supervising his own large army,

who, like the Sun, is invincible [and] burns the army of the enemies,

then tretā-, kṛta-, and dvāparayuga will be over.

When you see Bhīmasena empowered in battle ... (10)

And another verse:

The two armies resemble two oceans that flow together at the end of the age,

that are churned up by wild sea monsters, and abound with huge crocodiles.

And on the 18th day of the battle, Kṛṣṇa says to Balarāma:

... know that the Kali age has arrived.

The “contradiction” between the astronomical tradition and the Mahābhārata can perhaps be explained by the fact that the transition between the yugas is considered to extend over a longer period of time, the so-called “dawn” (saṃdhiḥ) of the ages. However, it is impossible that a gathering of planets lasts over a period of 36 years. Nor do celestial mechanics permit another such super-conjunction to occur 36 years after a super-conjunction, where all planets disappear in the light of the Sun. An interval of at least 38 years is necessary. This is because Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions, which are always included in a super-conjunction, happen only once every 20 years, and also because Mars and the other planets must accidentally accompany them.

The question arises whether the Mahābhārata narrative also provides evidence of a second super-conjunction that would have occurred almost four decades after the war around the day of Kṛṣṇas demise.

It is interesting that in the 16th book of the Mahābhārata, shortly before the death of Kṛṣṇa, similar omens occurred as have been described for the year leading up to the great war:

When the 36th year arrived, O joy of the Kurus,

Yudhiṣṭhira saw inauspicious omens.

The winds blew in tempests, dry and raining gravel.

The birds circumambulated to the right.

The great rivers flowed backwards. The [four] directions were shrouded in mist.

Meteors descended bringing rain of coal from the sky onto the earth.

The Sun disk was shrouded in haze, O king.

He was constantly without rays at sunrise and was seen vesseled in clouds.

Terrifying halos were seen around both the Moon and Sun,

in three colours with black and harsh edges, with devouring reddish light.

These and many other incidences that indicated danger/fear,

are seen day after day, O king, that cause agitation to the heart.

There is no mention of planets in this passage. It is interesting, how-ever, that the omens described are very similar to those that occur shortly before the great battle. The only thing that is missing is the mention of the super-conjunction. However, it can be found in a related text. In Bhāgavatapurāṇa 1.14.17 it says:

See, the glare of the Sun is destroyed, the planets gather together in the sky.

Sky and earth are set on fire, as it were, by the host of living beings that are [entangled] in battle.

The burning of the sky and the earth might allude to the reddish evening or morning sky, above which the gathering of planets could be seen. However, it seems that in reality this text is referring to the super-conjunction which occurred during the war. It is likely that the super-conjunctions during the war and the one at the time of Kṛṣṇa’s death were one and the same.

In MBh 16.5(4), the death of Kṛṣṇa in the forest is described as follows:

After he had withdrawn his senses, speech, and mind,

had laid himself down and gone into mahāyoga,

Jara came to this place

at the same time, greedy, desirous of a deer, impetuous.

Lying there in yoga, Kṛṣṇa

was taken as a deer by the greedy Jara.

He pierced the sole of his foot with an arrow

and swiftly went to him, wanting to catch the [deer].

Thinking he had sinned,

he touched (Kṛṣṇa’s) feet with his head, his appearance full of pain.

Then the Great Self consoled him,

rising up and pervading heaven and earth with beauty.

When he reached the sky, the Vasus, the Aśvins,

the Rudras, Ādityas, Vasus and Viśvedevas,

rose towards him, and the sages and siddhas

and the foremost of the Gandharvas with the Apsaras.

Then O king, the holy one, with terrible glare,

Nārāyaṇa (Kṛṣṇa), the origin and the imperishable one,

the teacher of yoga, pervaded heaven and earth with beauty;

the Great Self arrived at his own immeasurable abode.

Then Kṛṣṇa joined the gods and the Ṛṣis

and the Cāraṇas, O king,

worshipped by the foremost of the Gandharvas, the best Apsarās,

the Siddhas, Sādhyas and Cānatas.

These gods welcomed him, O king.

The best of the sages praised him as the lord with their words.

(B6: after he had united with the kings of the world, Śiva, Brahmā etc.,

praised by the hosts of the gods and siddhas.)

The Gandharvas awaited him with praises,

and Indra welcomed him lovingly.

Although a conjunction of the planets is not mentioned, the text gives the impression that there are some astronomical occurrences. Kṛṣṇa rose to the sky and filled heaven and earth with beauty. After that a considerable number of superhuman beings are mentioned that “rose towards him” (pratyudyayur). Could this have a deeper meaning? Could it be a mythological representation of a super-conjunction and a synchronous heliacal rising of all planets?

If so, what then would Kṛṣṇa represent? The Moon? The verses from Harivaṃśa quoted further above describe how the planets gathered around the Moon. Perhaps Kṛṣṇa represents the last crescent of the Moon that rose in the morning, and the planets made their heliacal rising “towards him”. When holy or powerful beings gather about their leader, then this is often compared to a clustering of the planets around the Moon. The same theme can be found in the following verse from the Bhāgavatapurāṇa. Śuka, the son of Vyāsa, gives a lesson to King Parīkṣit while being surrounded by many Ṛṣis:

Surrounded by the hosts of the Brahmarṣis, Rājarṣis and Devarṣis, himself being the greatest amongst the greatest,

the Holy One (Śuka) shone like the Moon, when multitudes of planets and the stars of the lunar mansions engulf him.

This verse might indeed allude to the configuration that took place at the beginning of kaliyuga. Parīkṣit is the first king after Yudhiṣṭhira, thus the first king of the kaliyuga.

A similar description is given at the return of Rāma to Kosala. All people gather about him, and then it can be read that:

Sitting in his celestial chariot, praised by women and lauded by bards,

the Holy One shone, O king, like the rising Moon [is praised] by the planets.

And the Bhāgavatapurāṇa says:

Balarāma appeased those Vṛṣṇi men, who were prepared [for battle];

He, who destroys the impurity of the [yuga of] quarrel (kaliḥ), did not want the quarrel (kaliḥ) between the Kurus and the Vṛṣṇis.

He went to Hastināpura with a chariot that shone like the Sun,

surrounded by Brahmins and elders of the family, like the Moon [is surrounded] by the planets.

And:

Wherever he went, O king, the inhabitants of the cities and the country

gathered around him with gifts in their hands, like the Sun risen together with the planets.

Also interesting is the following verse from Brahmapurāṇa:

No doubt this earth might be without moon, sun and planets [at the end of the yuga],

however the earth will never be without the sons of Puru.

When all the planets and the Moon are in conjunction with the Sun, it is impossible that the Moon and planets could be visible in the sky. But, why is the Sun surrounded by the planets in both these verses, whereas in the verse before that the Moon is surrounded by them? Astronomically, it does not necessarily make a big difference. It is only shortly before sunrise or shortly after sunset that the planets and the Moon can all be visible clustered together. The Sun is always very close to them. Besides, this kind of conjunction often follows or precedes a conjunction of all planets with the Sun, where they actually disappear in the light of the Sun and become invisible. This is in reference to earlier explanations of the various stages and types of super-conjunctions. Thus when in some places the planets gather around the Sun and in others around the Moon, then this is in relation to the different phases of one and the same super-conjunction.

Reverting to the demise of Kṛṣṇa, another description of his ascension is found in Bhāgavatapurāṇa 11.30 and 31. After Kṛṣṇa was hit by the hunter Jara’s arrow, his charioteer Dāruka finds him below a fig tree:

Dāruka looked for the way to Kṛṣṇa and found it:

he could smell the fragrance of Tulasī in the wind and followed it,

to his lord, who, surrounded by sharp shiny weapons, had set down there at the root of the Aśvattha tree.

Overwhelmed by a flood of love, he fell down to his feet, after he had jumped down from the chariot, his eyes filled with tears.

“O Lord, when I do not see your lotus feet, then my sight disappears and enters into darkness.

I cannot see the [four] directions and can find no peace, like a night when the Moon has disappeared.”

Whilst the charioteer was speaking these words, the chariot with the Garuḍa sign

flew up to the sky, O king of kings, in front of Dāruka who was looking upwards.

Behind the [chariot] followed the celestial weapons of Viṣṇu.

To the charioteer, who was in a state of great astonishment at this [occurrence], spoke Kṛṣṇa:

Again, this passage seems to talk of astronomical events. After all our considerations, their interpretation is obvious. The Moon has not been visible in the sky the whole night long. When Dāruka complained to his lord about the darkness, the chariot of Kṛṣṇa rises up to the sky. Could the chariot represent the last crescent of the Moon that rose in the eastern morning sky? And could the “sharp shiny weapons” that ascended to the sky behind him be the planets? Before rising, these weapons surrounded Kṛṣṇa. Does this picture symbolise the conjunction of all planets with the Moon and the Sun?

Immediately thereafter, there is talk of an assembly of gods and all kinds of supernatural beings, among which were Brahmā, Śiva and his wife Parvatī:

Then Brahmā and Śiva arrived with Parvatī,

the gods, lead by the great Indra, the sages together with the lord of the creatures,

the ancestors, Siddhas and Gandharvas, the Vidyādharas and great Nāgas,

Cāraṇas, Yakṣas and Rakṣās, Kinnaras, Apsaras and twice-born ones,

in their desire to see the ascent of the holy one, and in their longing for the Supreme [Lord],

praising and lauding the deeds and the birth of Kṛṣṇa.

They released a rain of flowers, while densely filling the sky with the rows of their celestial chariots, O king, filled with the highest devotion.

All sorts of celestial beings gathered around Kṛṣṇa and formed a kind of “conjunction” in the sky. It may also be mentioned, in an analogy to the verses quoted above: “... like the planets and stars gather around the Moon”. The host is headed by Brahmā and Śiva. This awakens memories of RV X.141.3 (brahmāṇaṃ ca bṛhaspatim), and Brahmā can perhaps be identified with Jupiter (Bṛhaspati) and Śiva with Venus (Śukra).

The holy one looked at the grandfather [Brahmā]; the all-pervading one united the all-pervading powers of his Self,

[uniting] his Self within his Self, and closed his lotus eyes.

His own person, that had given pleasure to the world and had been [full of] happiness [based on] concentration and meditation:

he burnt it with fire-like yoga concentration and entered his own [true] abode.

Kṛṣṇa causes his own cremation through the “fire” of his spiritual concentration. Could this mean – on an astronomical level – that the old Moon enters the glare of the Sun and thereby the invisible world? The text continues:

Drums resounded in the sky, and flowers (or: good thoughts) rained from the heights.

Truth, duty, firmness, fame, and glory followed him and left the earth

The gods and the other [beings], lead by Brahmā, could not see how Kṛṣṇa, whose path was unknown, entered his own abode, and they were very astonished.

As a lightning bolt runs through the sky, leaving behind a circle of clouds,

Kṛṣṇa’s departure could not be witnessed by mortal deities.

When Brahmā, Śiva, and the other [gods], saw Kṛṣṇa’s yogic departure,

they were amazed and praised it, and each of them went into his own world.

The gods broke up their assembly, separated, and each of them went his own way, like the planets use to do after a super-conjunction. The disappearance of Kṛṣṇa could allude to the disappearance of the old moon’s crescent in the light of day.

Other Purāṇas give a different description of the cremation of Kṛṣṇa, but even there some evidence of an astronomical configuration can be seen, e. g. in Viṣṇupurāṇa 5.38 and Brahmapurāṇa 212.8:

And Arjuna searched for the dead bodies of Rāma and Kṛṣṇa

and performed their funeral rites, also for the other [heroes] one by one.

The eight that are said to be his queens, headed by Rukmiṇī,

embraced the body of Kṛṣṇa and entered into the fire.

And the best Revatī also embraced the body of Rāma

and entered into the blazing fire, refreshed and cooled by the contact with him (or: it?).

And when Ugrasena and Vasudeva heard it

and Devakī and Rohiṇī, they also entered into the fire.

After Arjuna had done the funeral rites for them according to rule,

he departed and took everyone including Vajra with him.

The thousands of wives of Kṛṣṇa that departed from Dvārakā,

and Vajra and the people – Arjuna took them under his protection and went quietly away.

After Kṛṣṇa had abandoned the world of the mortals, the splendid assembly and the assembly hall

and the Pārijāta tree went up to the sky, O Maitreya.

On the day Kṛṣṇa (Hari) went to the sky and departed from earth,

on that very day the powerful era of Kali commenced.

And the ocean flooded the empty [city] of Dvārakā;

only the house of Kṛṣṇa was not flooded by the sea.

Together with Kṛṣṇa, the “bright assembly” (sabhā)81 and the “assembly hall of the gods” (sudharmā) rose to the sky. From our above considerations it is very likely that, again, this description alludes to the super-conjunction of all planets with the Sun and their synchronous heliacal rising. The super-conjunction could also be represented by the fact that some of his close relatives entered into the funeral pyre of the “Kṛṣṇa sun”. Thus perhaps that barbaric custom that requires widows to burn themselves together with their deceased husbands has an astronomical-astrological motif.

Thus it can be deduced, as the sources seem to indicate, that there were two super-conjunctions: one during the great battle, and another one almost four decades later when Kṛṣṇa died. However, the evidence supporting the second super-conjunction is rather cryptic, whereas the first one is described very clearly.

In fact, it is more likely that there was only one super-conjunction that was associated with both events, with the war and the death of Kṛṣṇa. It must be remembered that the super-conjunction occurs at the end of an age and constitutes part of the general pralayaḥ, or the “dissolution” of all things back to their origin. It is followed by a new emanation (sṛṣṭiḥ) of the cosmic order and a new age, which is accompanied by a synchronous re-emergence of the planets from the Sun. The transition from one age to the other is indicated by only one super-conjunction, not by two...

Hindus firmly believe that the Kaliyuga began on 18th February, 3102 BCE and that this date, or actually rather the counting of days and years that starts on that date, has been passed down to us through an unbroken tradition. However this must be questioned. The date of the start of the kaliyuga is not attested in any older sources, neither the Purāṇas, the Mahābhārata, or in any other Vedic text. In fact, as will be shown, it is even incompatible with these sources, although traditionalists will assume all kinds of mental handstands and somersaults in order to make those incompatibilities seemingly disappear. There are no archaeological or historical data providing any such clues that the date 3102 BCE has any significance whatsoever.

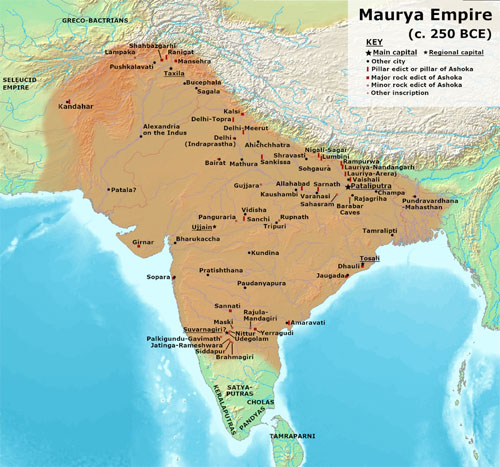

The kaliyuga era was first attested to by the ancient astronomer Āryabhaṭa, who assumed the beginning of kaliyuga to be 3600 years before the 23rd year of his life, which corresponds to the year 499 CE. Traditionalists love referring to the inscription of King Pulakeśin II in Aihole, Karṇāṭaka, which allegedly supports this dating. However, this inscription dates from the year 634 CE and is therefore even younger than Āryabhaṭa. Moreover, some authors refer to a number of title deeds written on copper plates that allegedly go back to King Janamejaya, who is said to have lived near 3000 BCE. However, these “copper grants” are obvious forgeries that served the purpose to support claims of ownership. Hence the statement found in Āryabhaṭa’s work is in fact the oldest testimony for the kaliyuga era, and over a whole period of 3600 years, the alleged tradition did not leave any trace in literary or archaeological sources. It must therefore be considered speculation. While the Mahābhārata and the Purāṇas do provide evidence that planetary clusterings were observed and considered important in ancient times, there is no available evidence that could support the kaliyuga era commencing in either 3102 or 3104 BCE.

Serious scholars therefore, do not accept the idea that the kaliyuga beginning on 18th February 3102 BCE is based on a true, unbroken tradition. Rather they assume that this date was back-calculated by Indian astronomers of late antiquity. It served as a mooring point for a theory of planetary cycles, as given in the Sūryasiddhānta, the most important work on ancient Indian astronomy....

There is a text found in several of the Purāṇas that links the beginning of the Kaliyuga with the death of Kṛṣṇa. However, instead of a conjunction of all planets, it mentions a conjunction of the Seven Ṛṣis in the lunar mansion Maghā. This text can be found in several different variations in VP 4.24.102ff., BhP 12.2.24ff., BrAP 2.74.225ff., MatsyaP 271.38ff. The text begins as follows:

From the birth of Parīkṣit until the inauguration of Nanda,

one must know, there are 1015 (var. 1050, 1115, 1500) years.

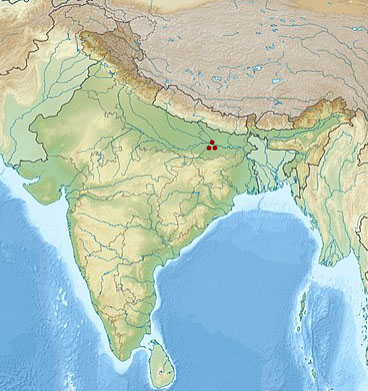

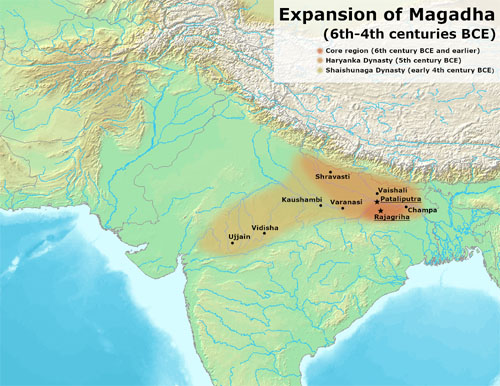

Parīkṣit is the first king of Hastināpura after Yudhiṣṭhira. His inauguration took place after Kṛṣṇa’s funeral, when Yudhiṣṭhira and his brothers renounced the kingdom and abdicated. Nanda is also called Mahāpadma in some versions of the text. He was the first king of the Nanda dynasty of Magadha. According to the Viṣṇupurāṇa, the Nandas ruled for about 100 years and were followed by Chandragupta Maurya, who seized power over Maghada in 321 BCE. The great number of variations of this text, e.g. the numbers of years mentioned, illustrates the text’s poor transmission. It is difficult to have confidence in any data given in it. Since the time between Parīkṣit’s seizure of power and Mahāpadma is between 1000 and 1500 years, Parīkṣit’s lifetime and the Mahābhārata battle would have fallen between the 20th and the 15th century BCE. This is in stark contrast to the traditional kaliyuga era, said to begin in 3102 BC. [However, traditionalists shun no effort in order to defend the Kaliyuga Era 3102 BCE. For that purpose, they are even ready to rewrite not only the whole history of India, but even the whole world history. The flowers of these absurd efforts: Buddha was allegedly born in 1887 BCE, Candragupta Maurya crowned in 1534 BCE, Aśoka in 1472 BCE, Śaṅkara was born in 509 BCE, etc. etc. (see K. Venkatachelam, The Plot in Indian Chronology, Appendix III). I shall not dwell on this, but refer to T. S. Kuppanna Sastry, Collected Papers on Jyotisha, p. 255-317, where the thinking errors in such approaches are exposed.]

The Saka Era of Varahamihira (Salivahana Saka) [Rep. from Journal of Indian History (Trivandrum), 36 (1958) 343-67.]

Introduction

With reference to chronology the word Saka is used in two senses: (1) As a common noun meaning any era (as for e.g., in the terms Yudhisthira Saka, Vikrama Saka, Malava Saka, Salivahana Saka etc.) and, (2) As a proper noun to mean a particular era called the Saka-kala or Saka Era. Most Indologists believe that the Saka Era is the same as what later is generally referred to as the Salivahana Saka which commenced with the month of Caitra occurring in 78 A.D., i.e., at the end of 3179 years of the Kali Era, for it can be shown that all astronomical works and commentaries thereon, wherever they mention a Saka Era, mean only the Salivahana Era, starting, as mentioned above, from 3179 Kali elapsed. But some like the late T.S. Narayana Sastri,1 [Cf. his Age of Sankara, (Madras, 1918), Pt. I, pp. 224ff.] Gulshan Rai,2 [Cf. his article, 'The Persian Emperor Cyrus, the Great, and the Saka Era,' Journal of the Panjab University Historical Society, (JPUHS), 1 (1932) 61-73, 122-36.] Kota Venkatachelam,3 [Cf. his Plot in Indian Chronology, (Vijayawada, 1953), 49-51; Indian Eras', Journal of the Andhra Historical Research Society, (JAHRS), 20 (1949-50), 43ff; 21 (1950-52), 61-73, 122-36.] and V. Thiruvenkatacharya4 [Cf. his 'Ayanamsa and Indian chronology: The Age of Varahamihira, Kalidasa etc.' Journal of Indian History (JIH) 28 (1950) 103ff. and 'The Andra Saka' JAHRS, 22 (1952-54) 161-8.] (VT) take the word to mean a certain Cyrus Era or Andhra Era which they say, started from 550 B.C.5 [ ] Kane mentions two others of the group: Janannatha Rao, Age of Mahabara war (1931), C.V. Vaidya starting the Sakakala from Buddha's nirvana. We now find that T.S.N is the source for all these people, and almost every argument used by them is his. In his Age of Sankara he has used a Yudhisthira Era of 3140-39 B.C., and a Saka Era of 576 B.C., which he later shifted to 550 B.C. Still another view is expressed by K. Rangarajan, who takes it to mean an era which commenced from 523/22 B.C. with the first Viceroy of India appointed by the Persian Emperor.6 [ ] They also try to show that it never means the Salivahana Saka.7 [ ] What astounds us is that even where there is clear evidence that Salivahana Saka is to be taken, (in the shape of statements that 3179 is to be added to the years gone in the Saka Era to get the years gone in Kali)8 [ ] these scholars ignore it implicitly as in the case of the Saka-kala mentioned by Brahmagupta and Bhaskara II.9 [ ] When this is the fate of such clear evidence, we need not be surprised if they identify with their alleged Cyrus or Andhra Era, the Saka Era mentioned in giving the epochs of karanas (astronomical manuals) as in the case of the Pancasiddhantika (PS), the Khandakhadyaka or the Laghumanasa, or in giving the date of a work given by the author, as for instance by Bhattotpala at the end of his commentary on the Brhajjataka or in inscriptions like the Aihole Inscription, or in sundry other places as in the Brhatsamhita 1.13, in all of which cases the identification has got to be made by examining the months and tithis and ksepas mentioned therewith.

The reason why they want to identify the Sakakala with the so-called Cyrus or Andhra Era is this: They believe that there was a “plot hatched by European Indologists” to post-date by several centuries the ancient events of Indian history, and that most Indian Indologists have become unconscious victims of that plot. They try to show that the Yudhisthira and Saptarsi Eras are everywhere identical, and were actually started 25 years after the beginning of the Kali Era. Using this they try to show that it is Samudra Gupta of the Gupta dynasty that is to be identified with the Sandracottus of the Greeks, and not Candragupta Maurya, which latter identification has been taken by the European Indologists as the sheet-anchor of Indian chronology, and the chronology of the dynasties before and after that time is established therefrom. Now, the identification of Sakakala with Salivahana Saka stands in their way. Hence their attempt to identify it with the so-called Cyrus or Andhra Era whose very existence is a matter of dispute, there being no evidence for it.

Most historians have not taken these people seriously, thinking that the very extravagance of their claims would be a deterrent to the acceptance of their views. But attempts have been made by Professors Gulshan Rai and VT to give astronomical and mathematical proofs to show that Varahamihira (VM) belongs to 123 B.C. and not to 505 A.D., (as he is generally believed to be), and thereby that the Sakakala mentioned by VM is the Cyrus or Andhra Era.10 [JPUHS I (1932) 124-27; and JIH 28 (1950) 103ff. and JAHRS 22 (1952-54) 172. Following his change to 551 B.C. as the Saka Epoch, in his Popular Astronomy, VT has changed VM to 124 B.C. from 123 B. C. But the arguments for the refutation of 123 B.C. are applicable in toto for the refutation of 124 B.C. also. ] They also attempt to show that the Sakakala mentioned by Bhattotpala as stated above is the Cyrus or Andhra Era, and therefore the Saka year 888 given by him corresponds to 338 or 339 A.D.;11 [JPUHS I (1932) 73 (date given 338 A D.), and JIH 28 (1950) 123 (date given 339 A D.) In his Popular Astronomy VT, has shifted this to 338 A.D. But in his ‘Andhra Saka’ VT gives this date as 340 A.D. ( ib„ p, 173).] which would mean that Brahmagupta, Aryabhata Bhaskara I etc. must precede this date. The present article is intended to expose the hollowness of the above theory and to show that the astronomical arguments adduced in support of it (which to the lay reader may look formidable) are erroneous, and thus knock the bottom out of the claims of this set of writers.

-- Collected Papers on Jyotisha, by T.S. Kuppanna Sastry (Former Hony. Professor, Sanskrit College, Madras), 1989

The text continues:

Of the first two of the Seven Ṛṣis who are seen rising in the sky,

exactly in their middle is seen the junction star at night.

The Seven Ṛṣis stand in conjunction with this [junction star] for 100 years according to human [calculation].

And in the time of Parīkṣit they were in the [lunar mansion] Maghā, O best one of the twice-born.

The Seven Ṛṣis – whoever they might be – gather and form a conjunction in the lunar mansion Maghā. At first only two leading ones gather about the junction star Maghā (Regulus), later all the seven join them. The conjunction lasts for 100 years, during the reign of King Parīkṣit.

Then the Kali [age] began, which by nature lasts for 1200 years [of gods].

When the holy one, the part of Viṣṇu (i. e. Kṛṣṇa), went to the sky, O twice-born one,

who was born from the family of Vasudeva, then the Kali [age] had arrived.

As long as he touched this earth with his lotus feet,

so long the Kali [age] was not able, to twine around the earth.

However, when that part of the everlasting Viṣṇu had ascended from the earth to the sky,

Yudhiṣṭhira, the son of dharma, together with his brothers gave up the kingdom.

For, when Yudhiṣṭhira (Pāṇḍava) saw inauspicious omens,

after Kṛṣṇa had passed away, he arranged the inauguration of Parīkṣit.

When these [seven] great Ṛṣis enter the [lunar mansion] Pūrvāṣāḍhā,

(var. When the [seven] great Ṛṣis go from the Maghās to Pūrvāṣāḍhā,)

then, starting from Nanda, that [Kali age] will increasingly take its course.

On the day that Kṛṣṇa went to the sky, precisely on that [day]

began the Kali age. Hear its calculation from me:

Verse 112 mentions another conjunction of the Seven Ṛṣis that took place in the lunar mansion Pūrvāṣāḍhā, about 1000 years later at the inauguration of King Nanda. Hence, taking into account the verse further above concerning the years elapsed between Parīkṣit and Nanda, it follows that the correct number of years must be either 1015 or 1050 years. Hence, Parīkṣit’s life time would fall into the 15th century BCE.

The longer text version of Brahmāṇdapurāṇa (BrAP 2.74.228-233b) includes some additional verses that say that it takes the Seven Ṛṣis 2700 years to complete the whole circle of the nakṣatras and that they spend 100 years in each nakṣatra. This information is in agreement with the above-mentioned statements that the Seven Ṛṣis once formed a conjunction in the lunar mansion Maghā and 1000 years later another conjunction in Pūrvāṣāḍhā.

But who are the Seven Ṛṣis, and what kind of astronomical phenomenon is hidden behind this “theory”? Tradition identifies them with the constellation Ursa Major, and the astrologer Varāhamihira in his Bṛhatsaṃhitā (chap. 13) is in agreement:

The Seven Sages, who cause the north to shine with a bead necklace, as it were, [through whom the north] laughs with a crown of white lotus flowers, as it were, whom [the north] has as its lords, as it were,

who, commanded by the leadership of the pole star (dhruva) revolve and cause [the north] to dance [in circles], – I shall explain the motion of these [Seven Sages] according to the teaching of Vṛddhagarga.

In any case, there can be no doubt that in Varāhamihira’s opinion, the Seven Ṛṣis are a constellation near the celestial north pole.

The subsequent verses talk of exactly the same theory that also appears in the Purāṇas:

The Seven Sages were in Maghā when King Yudhiṣṭhira ruled the earth,

and the Śaka Era and [the era] of this king are 2526 [years] apart.

One lunar mansion by one they move 100 years in each.

[The lunar mansion] that from the rising in the east leads them in direct line, – that is where they are in conjunction.

King Yudhiṣṭira was inaugurated after the end of the Mahābhārata battle. According to the above verses, this happened 2526 years before the Śaka Era, which is counted from the year 78 CE. From this, it can be calculated that the year of the battle was 2449 BCE. (-2448). I shall not dwell on the absurd mental gymnastics by which traditionalists try to reconcile Varāhamihira’s statement with the kaliyuga commencement being the year 3102 BCE. More interesting are the astronomical clues given by the text....

Unfortunately, the clustering of 781 BCE does not fit King Nanda’s reign either, which must be dated to the 4th century BCE. It must be conceded that a perfect solution for these problems cannot be found. However, it must be understood that the Purāṇa text, which was written at the earliest, in the 4th century CE is not based on historical observations but rather on astrological historical speculations...

A correlation of planets and gods is not found before Brahmāṇḍapurāṇa 1.2.24.47ff. There, Saturn corresponds to Yama, Jupiter to Bṛhaspati, Mars to Skanda, Venus to Śukra, and Mercury to Nārāyaṇa. Out of these names, the epic only uses Bṛhaspati for Jupiter and Śukra for Venus. Saturn is called Śanaiścara, Mars Aṅgāraka, and Mercury Budha. Thus Yama-Saturn is the only god that can be immediately identified as the father of one of the Pāṇḍavas, viz. of Yudhiṣṭhira. Saturn is associated with death, time, and dharma in the epic (MBh 12.192 (199).32). Yudhiṣṭhira also has the title dharmarājā, “King of Dharma”, which seems to accord well with the planet Saturn.

Could the divine fathers of the remaining Pāṇḍavas also be assigned to planets? Indra, the king of the gods, who plays the part of Jupiter Pluvius in the Vedic religion, could be identified with the planet Jupiter. The Aśvins could represent the “twin planets” Venus and Mercury, which are similar to each other in behaviour as they are inner planets. Hence Vayu remains for Mars. Making Arjuna then represent Jupiter, Bhīma, Mars, and Nakula and Sahadeva for Mercury and Venus.

However, while these specific assignments are uncertain, the basic assumption that the five Pāṇḍavas could originally have represented the five planets remains quite plausible. The heroes of the epic are often described as “bright” and “brilliant” and compared to celestial bodies, including planets, the Moon, and the Sun (see quotations on p. 337 and 339ff.). Even where heroes are compared to the Sun, there could actually be a planet behind it, because the planets are themselves often allegorised to suns. As in the following verse from the Harivaṃśa, which refers to the configuration at the end of an age and obviously describes a conjunction of all planets with the crescent of the old moon:...

In summary, it can be stated that the Western tradition of astronomical cycles is attested only since about 400 BCE (Plato, Berossus). Since Babylonian precursors of this doctrine are not known, it is likely that it was developed after 500 BCE as a side product of Babylonian planetary theories, in which planetary cycles played an important role.

If the Indian and Chinese testimonies of the super-conjunctions in the years 1198 and 1059 BCE are authentic, then of course the question arises whether the western cyclic models of history were not inspired by an Indian precursor. The idea of an eternal recurrence of the same seems to be rather Indian than Western in nature.

Still, the following points should be borne in mind:

1. The yuga theory of the Purāṇas, according to which a “great yuga” covers 43,20,000 years, is not found in the older Vedic literature and is even unknown to early works of Hellenistic Indian astrology (Yavanajātaka, Romakasiddhānta). It is thus obviously younger than the above-cited Western sources.

2. The planetary theories of the Siddhāntas are all younger than the above-cited Western sources. In pre-Hellenistic works of Indian astronomy and astrology (Vedāṅgajyotiṣa, Parāśaratantra), they do not appear.

On the other hand, the idea that all the planets come together and form a super-conjunction at the end of a cosmic age obviously first appeared in India and China. This idea is not found, e.g. in Homer’s epics.