by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/29/21

Arachosia: [x] (Old Persian: Harauvatiš); Ἀραχωσία (Greek: Arachosia)

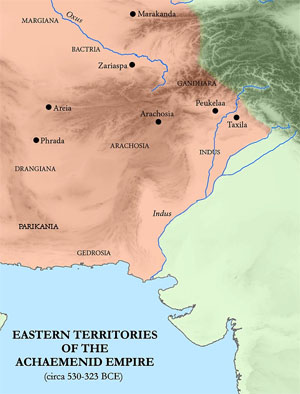

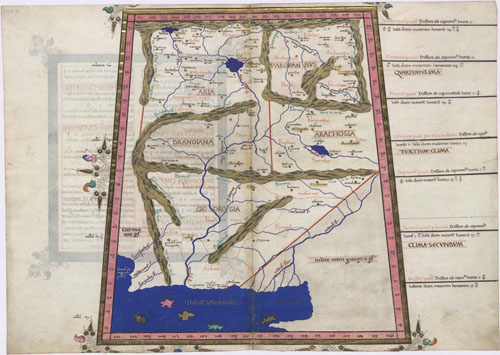

Eastern territories of the Achaemenid Empire, including Arachosia.

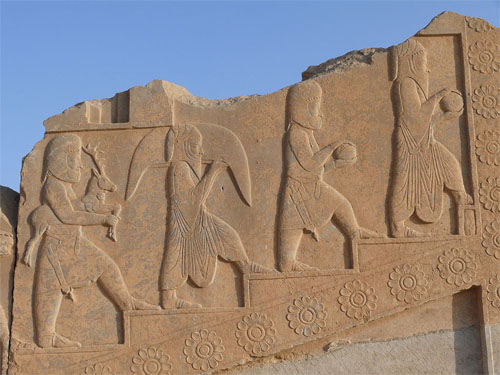

Arachosian soldier of the Achaemenid army, circa 470 BCE, Xerxes I tomb.

Arachosian priests of Zoroastrianism carrying various gifts and animals for a ritual of sacrifice at Persepolis

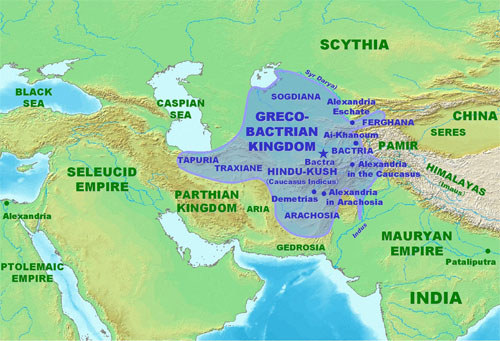

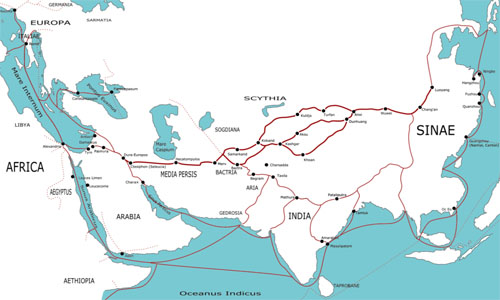

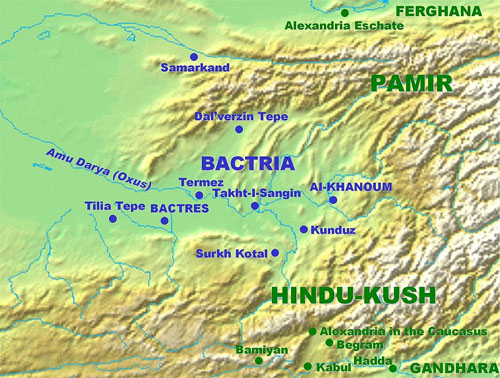

Arachosia /[x]/ is the Hellenized name of an ancient satrapy in the eastern part of the Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian, Greco-Bactrian, and Indo-Scythian empires. Arachosia was centred on the Arghandab valley in modern-day southern Afghanistan, although its influence extended east to as far as the Indus River. The main river of Arachosia was called Arachōtós, now known as the Arghandab River, a tributary of the Helmand River.[1] The Greek term "Arachosia" corresponds to the Aryan land of Harauti which was around modern-day Helmand. The Arachosian capital or metropolis was called Alexandria Arachosia or Alexandropolis and lay in what is today Kandahar in Afghanistan.[1] Arachosia was a part of the region of ancient Ariana.

Arghandab River Valley between Kandahar and Lashkargah

Helmand (Pashto/Dari: هلمند, Balochi:ہلمند, /ˈhɛlmənd/ HEL-mənd;), also known as Hillmand or Helman and, in ancient times, as Hermand and Hethumand, is one of the 34 provinces of Afghanistan, in the south of the country. It is the largest province by area, covering 58,584 square kilometres (20,000 sq mi) area. The province contains 13 districts, encompassing over 1,000 villages, and roughly 1,446,230 settled people. Lashkargah serves as the provincial capital.

Helmand was part of the Greater Kandahar region until made into a separate province by the Afghan government in the 20th century. The province has a domestic airport (Bost Airport), in the city of Lashkargah and heavily used by NATO-led forces. The former British Camp Bastion and U.S. Camp Leatherneck is a short distance southwest of Lashkargah.

The Helmand River flows through the mainly desert region of the province, providing water used for irrigation. The Kajaki Dam, which is one of Afghanistan's major reservoirs, is located in the Kajaki district. Helmand is believed to be one of the world's largest opium-producing regions, responsible for around 42% of the world's total production. This is believed to be more than the whole of Burma, which is the second largest producing nation after Afghanistan.

A U.S. Marine greeting local children working in an opium poppy field in 2011.

The region also produces tobacco, sugar beets, cotton, sesame, wheat, mung beans, maize, nuts, sunflowers, onions, potato, tomato, cauliflower, peanut, apricot, grape, and melon.

Since the 2001 War in Afghanistan, Helmand Province has been a hotbed of insurgent activities. It has been considered to be Afghanistan's "most dangerous" province.

-- Helmand Province, by Wikipedia

Name

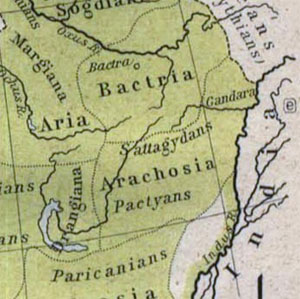

The ancient Arachosia and the Pactyan people during 500 BC.

"Arachosia" is the Latinized form of Greek Ἀραχωσία - Arachōsíā. "The same region appears in the Avestan Vidēvdāt (1.12) under the indigenous dialect form [x] Haraxvaitī- (whose -axva- is typical non-Avestan)."[1] In Old Persian inscriptions, the region is referred to as [x], written h(a)-r(a)-u-v(a)-t-i.[1] This form is the "etymological equivalent" of Vedic Sanskrit Sarasvatī-, the name of a river literally meaning "rich in waters/lakes" and derived from sáras- "lake, pond."[1] (cf. Aredvi Sura Anahita).

"Arachosia" was named after the name of a river that runs through it, in Greek Arachōtós, today known as the Arghandab, a left bank tributary of the Helmand.[1]

Geography

Arachosia bordered Drangiana to the west, Paropamisadae (i.e. Gandahara) to the north (a part of ancient India (present day Pakistan) to the east), and Gedrosia (or Dexendrusi) to the south. Isidore and Ptolemy (6.20.4-5) each provide a list of cities in Arachosia, among them (yet another) Alexandria, which lay on the river Arachotus. This city is frequently mis-identified with present-day Kandahar in Afghanistan, the name of which was thought to be derived (via "Iskanderiya") from "Alexandria",[2] reflecting a connection to Alexander the Great's visit to the city on his campaign towards India. But a recent discovery of an inscription on a clay tablet has provided proof that 'Kandahar' was already a city that traded actively with Persia well before Alexander's time. Isidore, Strabo (11.8.9) and Pliny (6.61) also refer to the city as "metropolis of Arachosia."

In his list, Ptolemy also refers to a city named Arachotus (English: Arachote /ˈærəkoʊt/; Greek: Ἀραχωτός) or Arachoti (acc. to Strabo), which was the earlier capital of the land. Pliny the Elder and Stephen of Byzantium mention that its original name was Cophen (Κωφήν). Hsuan Tsang refers to the name as Kaofu.[3] This city is identified today with Arghandab which lies northwest of present-day Kandahar.

Peoples

Further information: Pashtun people

A 15th century reconstruction (by Nicolaus Germanus) of a 2nd-century map (by Ptolemy)

The inhabitants of Arachosia were Iranian peoples, referred to as Arachosians or Arachoti.[1] They were called Pactyans by ethnicity, and that name may have been in reference to the present-day ethnic Paṣtun (Pashtun) tribes.[4]

Isidorus of Charax in his 1st century CE "Parthian stations" itinerary described an "Alexandropolis, the metropolis of Arachosia", which he said was still Greek even at such a late time:

"Beyond is Arachosia. And the Parthians call this White India; there are the city of Biyt and the city of Pharsana and the city of Chorochoad and the city of Demetrias; then Alexandropolis, the metropolis of Arachosia; it is Greek, and by it flows the river Arachotus. As far as this place the land is under the rule of the Parthians."

— "Parthians stations", 1st century CE. Original text in paragraph 19 of Parthian stations

History

Further information: History of Afghanistan

According to Arrian, Megasthenes lived in Arachosia and travelled to Pataliputra, to the court of Chandragupta Maurya.

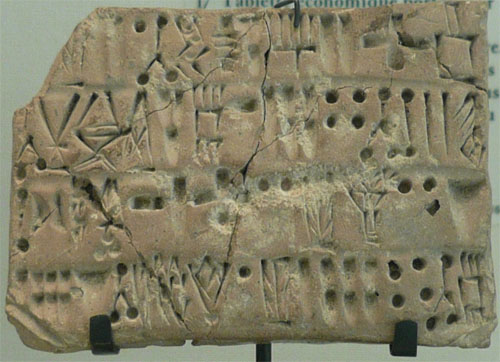

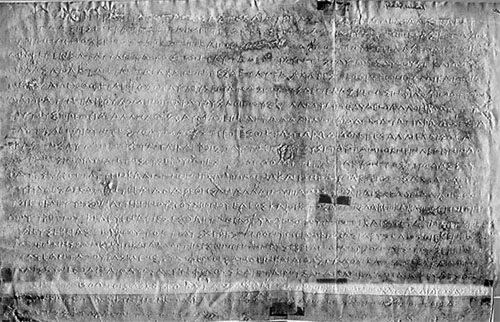

The region is first referred to in the Achaemenid-era Elamite Persepolis fortification tablets.

Oriental Institute Publications

Persepolis Fortification Tablets

R. T. Hallock

The University of Chicago Press, 1969

-- Persepolis Fortification Tablets, by Richard T. Hallock

With over 2100 texts published, the Persepolis Fortification Texts in Elamite, transcribed, interpreted, and edited by the late Richard Hallock, already form the largest coherent body of material on Persian administration available to us; a comparable, but less legible, body of material remains unpublished, as does the smaller group of Aramaic texts from the same archive. Essentially, they deal with the movement and expenditure of food commodities in the region of Persepolis in the fifteen years down to 493. Firstly, they make it absolutely clear that everyone in the state sphere of the Persian economy was on a fixed ration-scale, or rather, since some of the rations are on a scale impossible for an individual to consume, a fixed salary expressed in terms of commodities. The payment of rations is very highly organized. Travelers along the road carried sealed documents issued by the king or officials of satrapal level stating the scale on which they were entitled to be fed. Tablets sealed by supplier and recipient went back to Persepolis as a record of the transaction. Apart from a few places in Babylonia for short periods, Persepolis is now the best-documented area in the Achaemenid empire. What generalizations or other insights this provides for other areas is perhaps likely to remain one of the main methodological problems for Achaemenid scholarship. [From an article by D. M. Lewis, "The Persepolis Fortification Texts," in Achaemenid History IV: Centre and Periphery, Proceedings of the Groningen 1986 Achaemenid History Workshop, edited by Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amélie Kuhrt (Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 1990), pp. 2-6].

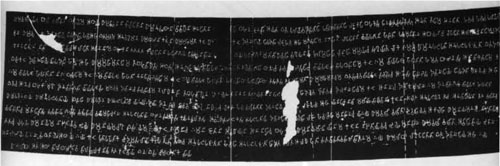

Tablet of Elamite script

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was used in present-day southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC. Elamite works disappear from the archeological record after Alexander the Great entered Iran. Elamite is generally thought to have no demonstrable relatives and is usually considered a language isolate. The lack of established relatives makes its interpretation difficult.Language isolates are languages that cannot be classified into larger language families with any other languages. Korean and Basque are two of the most commonly cited language isolates, though there are many others.

A language isolate is a language that is unrelated to any others, which makes it the only language in its own language family. It is a natural language with no demonstrable genealogical (or "genetic") relationships—one that has not been demonstrated to descend from an ancestor common with any other language.

One explanation for the existence of language isolates is that they might be the last remaining branch of a larger language family. The language possibly had relatives in the past but they have since disappeared without being documented. Another explanation for language isolates is that they developed in isolation from other languages. This explanation mostly applies to sign languages that have arisen independently of other spoken or signed languages.

-- Language isolate, by Wikipedia

A sizeable number of Elamite lexemes are known from the trilingual Behistun inscription and numerous other bilingual or trilingual inscriptions of the Achaemenid Empire, in which Elamite was written using Elamite cuneiform (circa 400 BCE), which is fully deciphered. An important dictionary of the Elamite language, the Elamisches Wörterbuch was published in 1987 by W. Hinz and H. Koch. The Linear Elamite script however, one of the scripts used to write the Elamite language circa 2000 BC, has remained elusive until recently.

Writing system

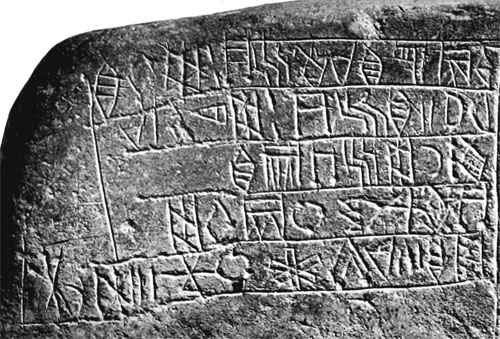

Linear Elamite inscription of king Puzur-Inshushinak

in the "Table du Lion", Louvre Museum Sb 17.

Two early scripts of the area remain undeciphered but plausibly have encoded Elamite:

• Proto-Elamite is the oldest known writing system from Iran. It was used during a brief period of time (c. 3100–2900 BC); clay tablets with Proto-Elamite writing have been found at different sites across Iran. It is thought to have developed from early cuneiform (proto-cuneiform) and consists of more than 1,000 signs. It is thought to be largely logographic.

• Linear Elamite is attested in a few monumental inscriptions. It is often claimed that Linear Elamite is a syllabic writing system derived from Proto-Elamite, but it cannot be proven. Linear Elamite was used for a very brief period of time during the last quarter of the third millennium BC.

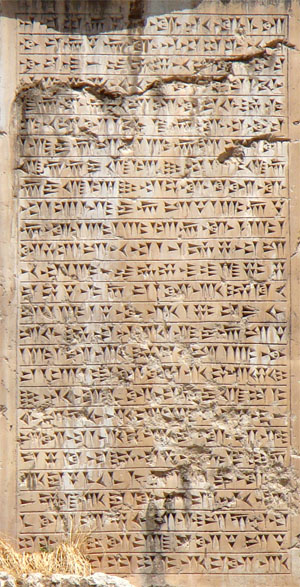

Later, Elamite cuneiform, adapted from Akkadian cuneiform, was used from c. 2500 to 331 BC. Elamite cuneiform was largely a syllabary of some 130 glyphs at any one time and retained only a few logograms from Akkadian but, over time, the number of logograms increased. The complete corpus of Elamite cuneiform consists of about 20,000 tablets and fragments. The majority belong to the Achaemenid era, and contain primarily economic records....

History

Inscription of Shutruk-Nahhunte in Elamite cuneiform, circa 1150 BC, on the Victory Stele of Naram-Sin.

The history of Elamite is periodised as follows:

• Old Elamite (c. 2600–1500 BC)

• Middle Elamite (c. 1500–1000 BC)

• Neo-Elamite (1000–550 BC)

• Achaemenid Elamite (550–330 BC)

Middle Elamite is considered the “classical” period of Elamite, but the best attested variety is Achaemenid Elamite, which was widely used by the Achaemenid Persian state for official inscriptions as well as administrative records and displays significant Old Persian influence. Documents from the Old Elamite and early Neo-Elamite stages are rather scarce.

Neo-Elamite can be regarded as a transition between Middle and Achaemenid Elamite, with respect to language structure.

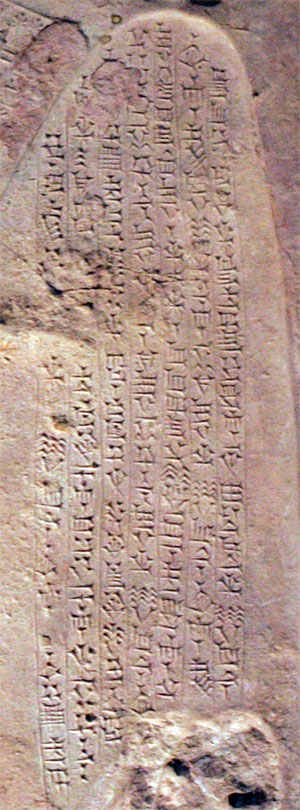

Inscription in Elamite, in the Xerxes I inscription at Van, 5th century BCE

The Elamite language may have remained in widespread use after the Achaemenid period. Several rulers of Elymais bore the Elamite name Kamnaskires in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC. The Acts of the Apostles (c. 80–90 AD) mentions the language as if it was still current. There are no later direct references, but Elamite may be the local language in which, according to the Talmud, the Book of Esther was recited annually to the Jews of Susa in the Sasanian period (224–642 AD). Between the 9th and 13th centuries AD, various Arabic authors refer to a language called Khuzi spoken in Khuzistan, which was not any other language known to those writers. It is possible that it was "a late variant of Elamite".

-- Elamite language, by Wikipedia

It appears again in the Old Persian, Akkadian and Aramaic inscriptions of Darius I [550 B.C.–486 B.C.] and Xerxes I [518 B.C.–August 465 BC] among lists of subject peoples and countries.

Aramaic (Classical Syriac: [x] Arāmāyā; Old Aramaic: [x]; Imperial Aramaic: [x]; square script [x]) is a Semitic language that originated among the Arameans in the ancient region of Syria. During its three thousand year long history, Aramaic went through several stages of development. It has served as a language of public life and administration of ancient kingdoms and empires, and also as a language of divine worship and religious study. It subsequently branched into several Neo-Aramaic languages that are still spoken in modern times.

The Aramaic language belongs to the Northwest group of the Semitic language family, which also includes the Canaanite languages, such as Hebrew, Edomite, Moabite, and Phoenician, as well as Amorite and Ugaritic. Aramaic languages are written in the Aramaic alphabet, which was derived from the Phoenician alphabet. One of the most prominent variants of the Aramaic alphabet, still used in modern times, is the Syriac alphabet. The Aramaic alphabet also became a base for the creation and adaptation of specific writing systems in some other Semitic languages, thus becoming the precursor of the Hebrew alphabet and the Arabic alphabet.

Historically and originally, Aramaic was the language of the Arameans, a Semitic-speaking people of the region between the northern Levant and the northern Tigris valley. By around 1000 BC, the Arameans had a string of kingdoms in what is now part of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and the fringes of southern Mesopotamia and Anatolia. Aramaic rose to prominence under the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), under whose influence Aramaic became a prestige language after being adopted as a lingua franca of the empire, and its use spread throughout Mesopotamia, the Levant and parts of Asia Minor. At its height, Aramaic, having gradually replaced earlier Semitic languages, was spoken in several variants all over what is today Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Eastern Arabia, Bahrain, Sinai, parts of southeast and south central Turkey, and parts of northwest Iran.

Aramaic was the language of Jesus, who spoke the Galilean dialect during his public ministry, as well as the language of several sections of the Hebrew Bible, including books of Daniel and Ezra, and also the language of the Targum, Aramaic translation of the Hebrew Bible.

The scribes of the Neo-Assyrian bureaucracy had also used Aramaic, and this practice was subsequently inherited by the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (605–539 BC), and later by the Achaemenid Empire (539–330 BC). Mediated by scribes that had been trained in the language, highly standardized written Aramaic (named by scholars as Imperial Aramaic) progressively also become the lingua franca of public life, trade and commerce throughout the Achaemenid territories. Wide use of written Aramaic subsequently led to the adoption of the Aramaic alphabet and (as logograms) some Aramaic vocabulary in the Pahlavi scripts, which were used by several Middle Iranian languages (including Parthian, Middle Persian, Sogdian, and Khwarazmian).

-- Aramaic, by Wikipedia

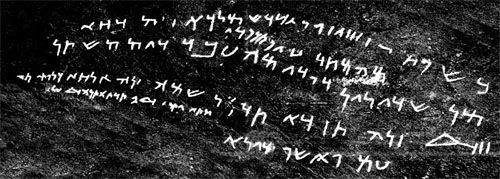

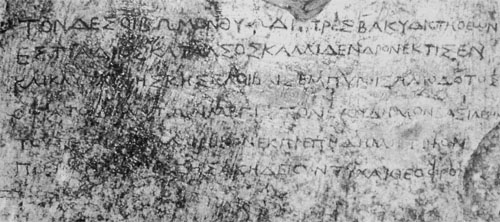

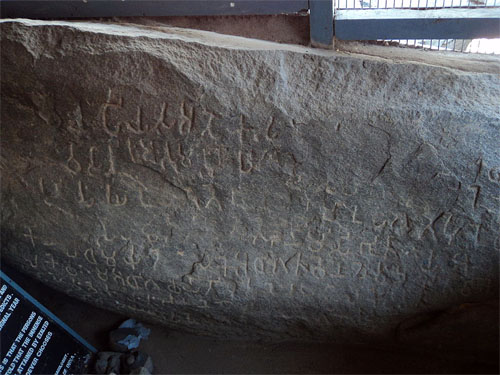

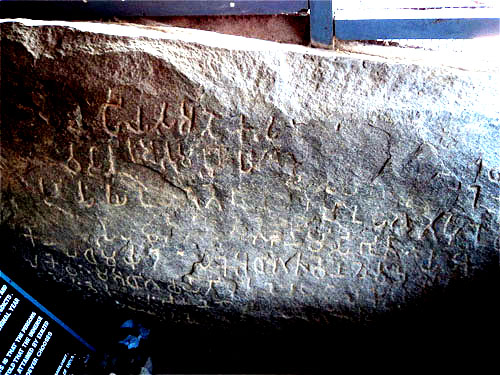

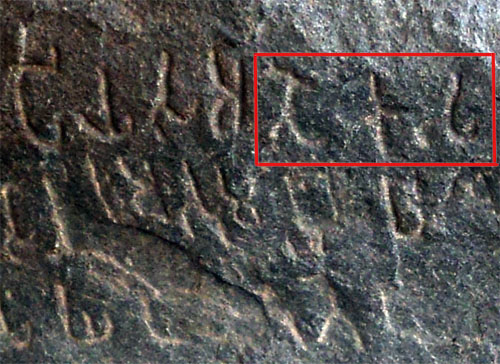

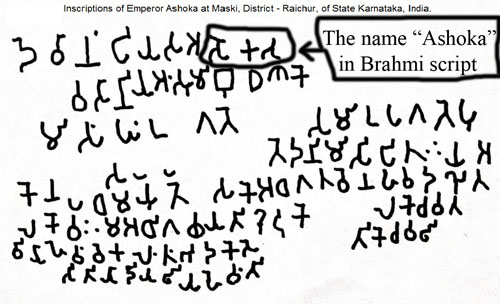

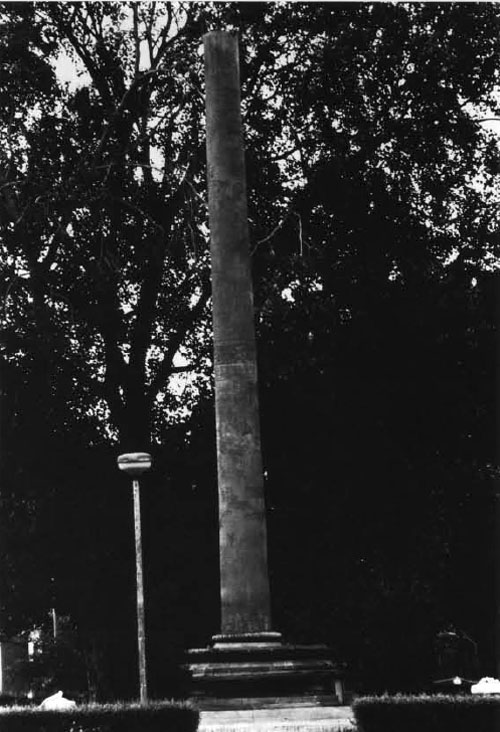

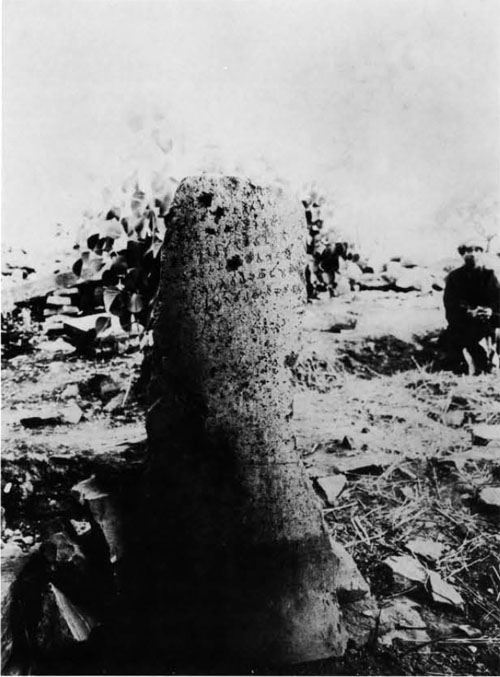

The Aramaic inscription of Laghman, also called the Laghman I inscription to differentiate from the Laghman II inscription discovered later, is an inscription on a slab of natural rock in the area of Laghmân, Afghanistan, written in Aramaic by the Indian emperor Ashoka about 260 BCE, and often categorized as one of Minor Rock Edicts of Ashoka. This inscription was published in 1970 by André Dupont-Sommer. Since Aramaic was an official language of the Achaemenid Empire, and reverted to being just its vernacular tongue in 320 BCE with the conquests of Alexander the Great, it seems that this inscription was addressed directly to the populations of this ancient empire still present in this area, or to border populations for whom Aramaic remained the language used in everyday life.

Epigraphical context

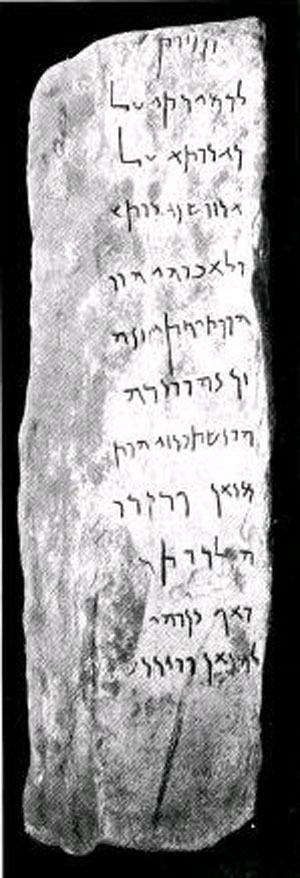

The chance discovery by two Belgian anthropologists of this inscription in 1969 is one of a set of similar inscriptions in Aramaic or Greek (or both together), written by Asoka. In 1915, Sir John Marshall had discovered the Aramaic Inscription of Taxila,

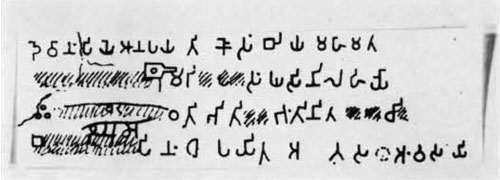

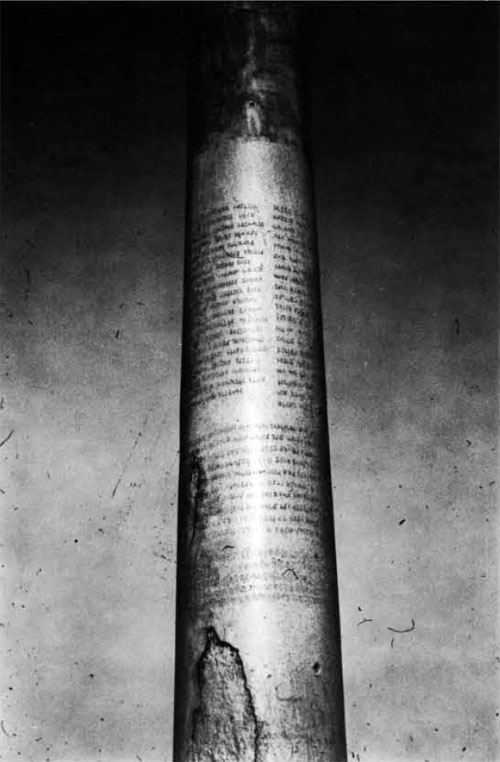

Aramaic inscription of Taxila.

The Aramaic Inscription of Taxila 'is an inscription on a piece of marble, originally belonging to an octagonal column, discovered by Sir John Marshall in 1915 at Taxila, British India. The inscription is written in Aramaic, probably by the Indian emperor Ashoka around 260 BCE, and often categorized as one of the Minor Rock Edicts. Since Aramaic was the official language of the Achaemenid empire, which disappeared in 330 BCE with the conquests of Alexander the Great, it seems that this inscription was addressed directly to the populations of this ancient empire still present in northwestern India, or to border populations for which Aramaic remained the normal communication language. The inscription is known as KAI 273...

Text of the inscription

The text of the inscription is very fragmentary, but it has been established that it contains twice, lines 9 and 12, the mention of MR'N PRYDRŠ ("our lord Priyadasi"), the characteristic title used by Ashoka.

-- Aramaic Inscription of Taxila, by Wikipedia

followed in 1932 by the Pul-i-Darunteh Aramaic inscription.

The Pul-i-Darunteh Aramaic inscription, also called Aramaic inscription of Lampaka, is an inscription on a rock in the valley of Laghman ("Lampaka" being the transcription in Sanskrit of "Laghman"), Afghanistan, written in Aramaic by the Indian emperor Ashoka around 260 BCE. It was discovered in 1932 at a place called Pul-i-Darunteh. Since Aramaic was the official language of the Achaemenid Empire, which disappeared in 320 BCE with the conquests of Alexander the Great, it seems that this inscription was addressed directly to the populations of this ancient empire still present in northwestern India, or to border populations for whom Aramaic remained the language of use....

Content of the inscription

The inscription is incomplete. However, the place of discovery, the style of the writing, the vocabulary used, makes it possible to link the inscription to the other Ashoka inscriptions known in the region. In the light of other inscriptions, it has been found that the Pul-i-Darunteh inscription consists of a juxtaposition of Indian and Aramaic languages, all in Aramaic script, and the latter representing translations of the first. This inscription is generally interpreted as a translation of a passage of the Major Pillar Edicts n°5 or n°7, although others have proposed to categorize it among the Minor Rock Edicts of Ashoka.

-- Pul-i-Darunteh Aramaic inscription, by Wikipedia

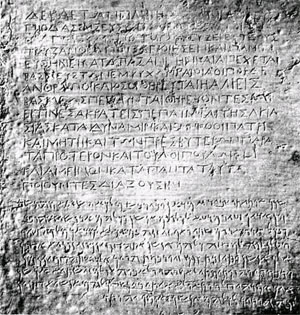

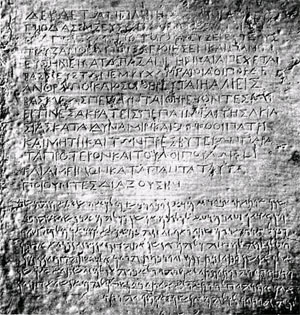

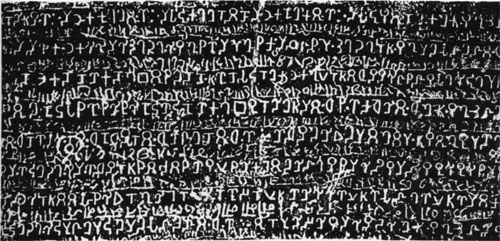

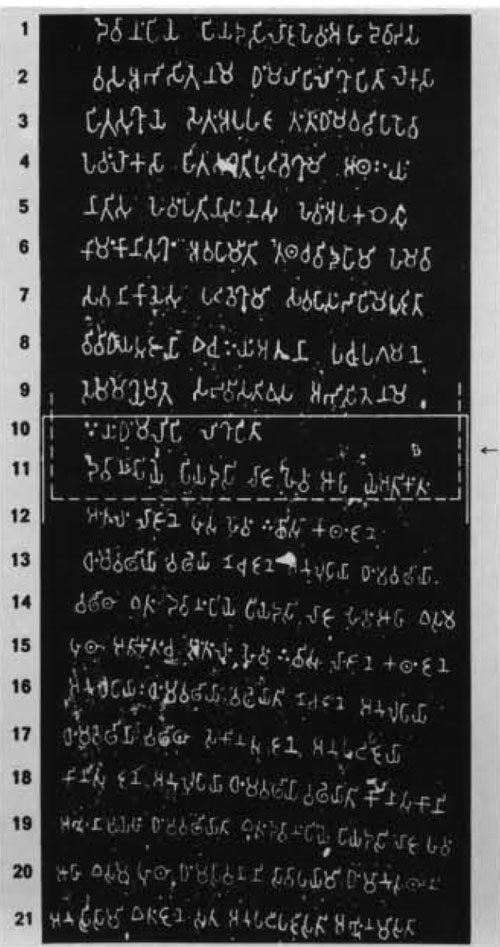

In 1958 the famous Bilingual Kandahar Inscription, written in Greek and Aramaic was discovered,

Bilingual inscription (Greek and Aramaic) by king Ashoka, discovered in Kandahar.

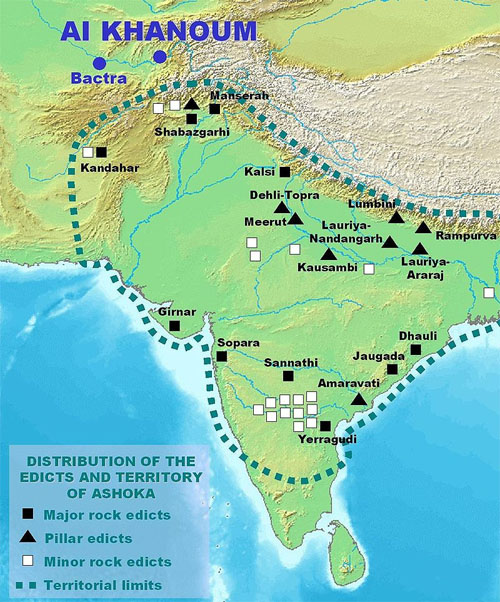

The Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription, (also Kandahar Edict of Ashoka, sometimes "Chehel Zina Edict"), is a famous bilingual edict in Greek and Aramaic, proclaimed and carved in stone by the Indian Maurya Empire ruler Ashoka (r.269-233 BCE) around 260 BCE. It is the very first known inscription of Ashoka, written in year 10 of his reign (260 BCE), preceding all other inscriptions, including his early Minor Rock Edicts, his Barabar caves inscriptions or his Major Rock Edicts. This first inscription was written in Classical Greek and Aramaic exclusively. It was discovered in 1958, during some excavation works below a 1m high layer of rubble, and is known as KAI 279.

It is sometimes considered as one of the several "Minor Rock Edicts" of Ashoka (and then called "Minor Rock Edict No.4), in contrast to his "Major Rock Edicts" which contain portions or the totality of his Edicts from 1 to 14. Two edicts in Afghanistan have been found with Greek inscriptions, one of these being this bilingual edict in Greek language and Aramaic, the other being the Kandahar Greek Inscription in Greek only. This bilingual edict was found on a rock on the mountainside of Chehel Zina (also Chilzina, or Chil Zena, "Forty Steps"), which forms the western natural bastion of ancient Alexandria Arachosia and present Kandahar's Old City.

The Edict is still in place on the mountainside. According to Scerrato, "the block lies at the eastern base of the little saddle between the two craggy hills below the peak on which the celebrated Cehel Zina of Babur are cut". A cast is visible in Kabul Museum. In the Edict, Ashoka advocates the adoption of "Piety" (using the Greek term Eusebeia for "Dharma") to the Greek community.

Background

Greek communities lived in the northwest of the Mauryan empire, currently in Pakistan, notably ancient Gandhara near the current Pakistani capital of Islamabad, and in the region of Arachosia, nowadays in Southern Afghanistan, following the conquest and the colonization efforts of Alexander the Great around 323 BCE. These communities therefore seem to have been still significant in the area of Afghanistan during the reign of Ashoka, about 70 years after Alexander.

Content

Ashoka proclaims his faith, 10 years after the violent beginning of his reign, and affirms that living beings, human or animal, cannot be killed in his realm. In the Hellenistic part of the Edict, he translates the Dharma he advocates by "Piety" εὐσέβεια, Eusebeia, in Greek. The usage of Aramaic reflect the fact that Aramaic (the so-called Official Aramaic) had been the official language of the Achaemenid Empire which had ruled in those parts until the conquests of Alexander the Great. The Aramaic is not purely Aramaic, but seems to incorporate some elements of Iranian. According to D.D. Kosambi, the Aramaic is not an exact translation of the Greek, and it seems rather that both were translated separately from an original text in Magadhi, the common official language of India at the time, used on all the other Edicts of Ashoka in Indian language, even in such linguistically distinct areas as Kalinga. It is written in Aramaic alphabet.

This inscription is actually rather short and general in content, compared to most Major Rock Edicts of Ashoka, including the other inscription in Greek of Ashoka in Kandahar, the Kandahar Greek Edict of Ashoka, which contains long portions of the 12th and 13th edicts, and probably contained much more since it was cut off at the beginning and at the end.

Implications

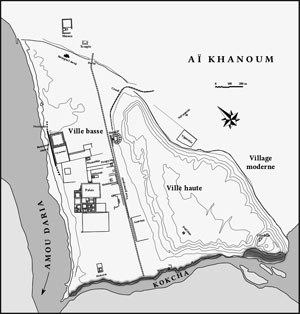

The proclamation of this Edict in Kandahar is usually taken as proof that Ashoka had control over that part of Afghanistan, presumably after Seleucos had ceded this territory to Chandragupta Maurya in their 305 BCE peace agreement. The Edict also shows the presence of a sizable Greek population in the area, but it also shows the lingering importance of Aramaic, several decades after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire. At the same epoch, the Greeks were firmly established in the newly created Greco-Bactrian kingdom under the reign of Diodotus I, and particularly in the border city of Ai-Khanoum, not far away in the northern part of Afghanistan.

According to Sircar, the usage of Greek in the Edict indeed means that the message was intended for the Greeks living in Kandahar, while the usage of Aramaic was intended for the Iranian populations of the Kambojas.

Transcription

The Greek and Aramaic versions vary somewhat, and seem to be rather free interpretations of an original text in Prakrit. The Aramaic text clearly recognizes the authority of Ashoka with expressions such as "our Lord, king Priyadasin", "our lord, the king", suggesting that the readers were indeed the subjects of Ashoka, whereas the Greek version remains more neutral with the simple expression "King Ashoka"...

English (translation of the Greek)Ten years (of reign) having been completed, King

Piodasses made known (the doctrine of)

Piety (εὐσέβεια, Eusebeia) to men; and from this moment he has made

men more pious, and everything thrives throughout

the whole world. And the king abstains from (killing)

living beings, and other men and those who (are)

huntsmen and fishermen of the king have desisted

from hunting. And if some (were) intemperate, they

have ceased from their intemperance as was in their

power; and obedient to their father and mother and to

the elders, in opposition to the past also in the future,

by so acting on every occasion, they will live better

and more happily."

English (translation of the Aramaic)Ten years having passed (?). It so happened (?) that our lord, king Priyadasin, became the institutor of Truth,

Since then, evil diminished among all men and all misfortunes (?) lie caused to disappear; and [there is] peace as well as joy in the whole earth.

And, moreover, [there is] this in regard to food: for our lord, the king, [only] a few

[animals] are killed; having seen this, all men have given up [the slaughter of animals]; even (?) those men who catch fish (i.e. the fishermen) are subject to prohibition.

Similarly, those who were without restraint have ceased to be without restraint.

And obedience to mother and to father and to old men [reigns] in conformity with the obligations imposed by fate on each [person].

And there is no Judgement for all the pious men,

This [i.e. the practice of Law] has been profitable to all men and will be more profitable [in future].

-- Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription, by Wikipedia

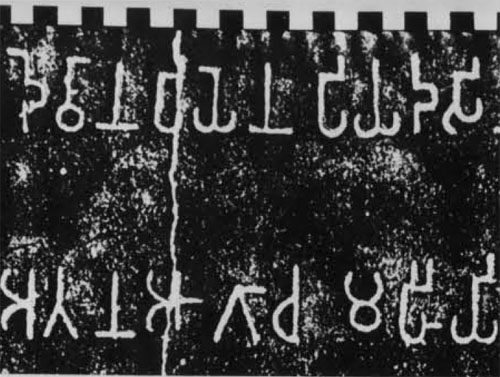

and in 1963 the Greek Edicts of Ashoka, again in Kandahar.

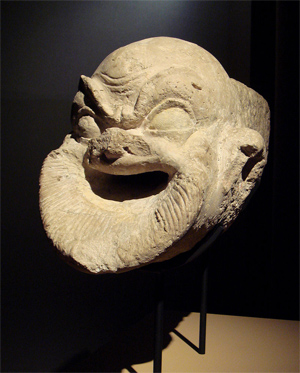

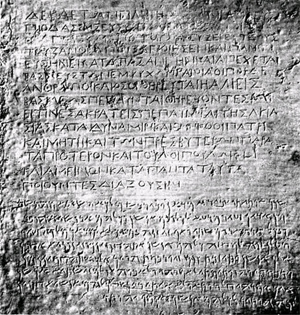

Greek inscription by king Ashoka, discovered in Kandahar

The Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka are among the Major Rock Edicts of the Indian Emperor Ashoka (reigned 269-233 BCE), which were written in the Greek language. They were found in the ancient area of Old Kandahar (known as Zor Shar in Pashto, or Shahr-i-Kona in Farsi) in Kandahar in 1963. It is thought that Old Kandahar was founded in the 4th century BCE by Alexander the Great, who gave it the Ancient Greek name Αλεξάνδρεια Aραχωσίας (Alexandria of Arachosia).

The extant edicts are found in a plaque of limestone, which probably had belonged to a building, and its size is 45x69.5 cm and it is about 12 cm thick. These are the only Ashoka inscriptions thought to have belonged to a stone building. The beginning and the end of the fragment are lacking, which suggests the inscription was original significantly longer, and may have included all 14 of Ashoka's Edicts in Greek, as in several other locations in India. The plaque with the inscription was bought in the Kandahar market by the German doctor Seyring, and French archaeologists found that it had been excavated in Old Kandahar. The plaque was then offered to the Kabul Museum, but its current location is unknown following the looting of the museum in 1992–1994...

Content

The Edict is a Greek version of the end of the 12th Edicts (which describes moral precepts) and the beginning of the 13th Edict (which describes the King's remorse and conversion after the war in Kalinga), which makes it a portion of a Major Rock Edict. This inscription does not use another language in parallel, contrary to the famous Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription in Greek language and Aramaic, discovered in the same general area.

The Greek language used in the inscription is of a very high level and displays philosophical refinement. It also displays an in-depth understanding of the political language of the Hellenic world in the 3rd century BCE. This suggests the presence of a highly cultured Greek presence in Kandahar at that time.

Implications

The proclamation of this edict in Kandahar is usually taken as proof that Ashoka had control over that part of Afghanistan, presumably after Seleucus I had ceded this territory to Chandragupta Maurya in their 305 BCE peace agreement. The Edict also shows the presence of a sizable Greek population in the area where great efforts were made to convert them to Buddhism. At the same epoch, the Greeks were established in the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, and particularly in the border city of Ai-Khanoum, in the northern part of Afghanistan.

Translation

English translation(End of Edict Nb12)

"...piety and self-mastery in all the schools of thought; and he who is master of his tongue is most master of himself. And let them neither praise themselves or disparage their neighbors in any matter whatsoever, for that is vain. In acting in accordance with this principle, they exalt themselves and win their neighbors; in transgressing in these things they misdemean themselves and antagonize their neighbors. Those who praise themselves and denigrate their neighbors are self-seekers, wishing to shine in comparison with the others but in fact hurting themselves. It behoves to respect one another and to accept one another's lessons. In all actions it behoves to be understanding, sharing with one another all that which one comprehends. And to those who strive thus let there be no hesitation to say these things in order that they may persist in piety in everything.

(Beginning of Edict Nb13)

In the eighth of the reign of Piodasses, he conquered Kalinga. A hundred and fifty thousand persons were captured and deported, and a hundred thousand others were killed, and almost as many died otherwise. Thereafter, piety and compassion seized him and he suffered grievously. In the same manner wherewith he ordered abstention from living thing, he has displayed zeal and effort to promote piety. And at the same time the king has viewed this with displeasure: of Brahmins and Sramins and others practicing piety who live there [in Kalinga]- and these must be mindful of the interests of the king and must revere and respect their teacher, their father and their mother, and love and faithfully cherish their friends and companions and must use their slaves and dependents as gently as possible - if, of those thus engaged there, any has died or been deported and the rest have regarded this lightly, the king has taken it with exceeding bad grace. And that amongst other people there are..."

— Translation by R.E.M. Wheeler.

-- Kandahar Greek Edicts of Ashoka, by Wikipedia

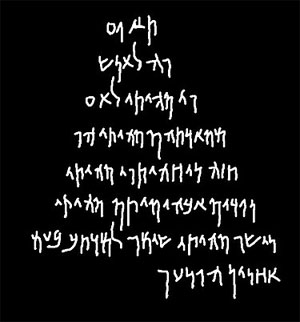

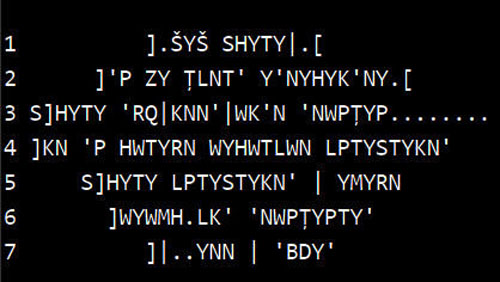

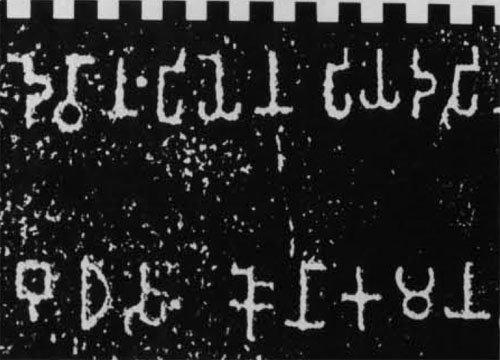

In the same year 1963 and again in Kandahar, an inscription in "Indo-Aramaic" known as the Kandahar Aramaic inscription or Kandahar II was found, in which the Indian Prakrit language and the Aramaic language alternate, but using only the Aramaic script.

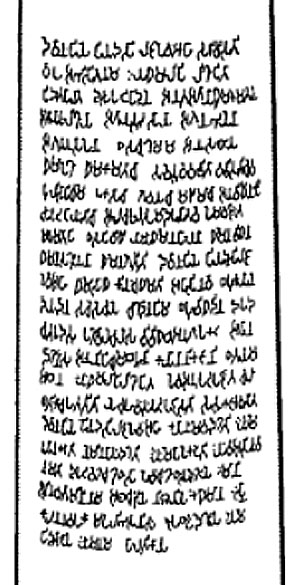

Transliteration in Roman alphabet of the Aramaic inscription of Kandahar.

The Aramaic inscription of Kandahar is an inscription on a fragment of a block of limestone (24x18 cm) discovered in the ruins of Old Kandahar, Afghanistan in 1963, and published in 1966 by André Dupont-Sommer. It was discovered practically at the same time as the Greek Edicts of Ashoka, which suggests that the two inscriptions were more or less conjoined. The inscription was written in Aramaic, probably by the Indian emperor Ashoka about 260 BCE. Since Aramaic was the official language of the Achaemenid Empire, which disappeared in 320 BCE with the conquests of Alexander the Great, it seems that this inscription was addressed directly to the populations of this ancient empire still present in northwestern India, or to border populations for whom Aramaic remained the language of use...

Content of the inscription

This inscription is usually interpreted as a version of a passage from Major Pillar Edict n°7.

The word SHYTY which appears several times corresponds to the Middle Indian word Sahite (Sanskrit Sahitam), meaning "in agreement with", "according to ...", and which allows to introduce a quote, in this case here Indian words found in the Ashoka Edits. Many of these Indian words, transcribed here phonetically in Aramaic, are indeed identifiable, and otherwise exist only in Major Pillar Edict n°7 of Ashoka, in the same order of use : 'NWPTYPTY' corresponds to the Indian word anuppatipatiya (without order, in disorder), and 'NWPTYP ...' to anuppatipamme. Y'NYHYK'NY .... corresponds to yani hi kanici and is the first word of this edict.

There are also several words in the Aramaic language, the role of which would be to explain the meaning of the Indian words and phrases mentioned: the word WK'N "and now", WYHWTRYWN "they have grown, and they will grow", PTYSTY "obedience" ....

This inscription, in spite of its partial and often obscure character, seems to be a translation or a line-by-line commentary of elements of Major Pillar Edict n°7. A more extensive analysis with photographs was published in the Asian Journal.

-- Kandahar Aramaic inscription, by Wikipedia

The Aramaic parts translate the Indian parts transcribed in the Aramaic alphabet. A few years after this description was discovered, in 1973, the Lahmann II inscription followed.

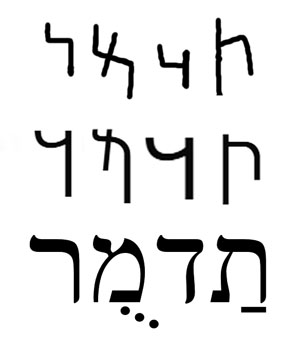

The word "Tadmor" in the Laghman inscription (top, right to left), compared to "Tadmor" in the Imperial Aramaic script (middle), and in the modern Hebrew script (bottom).

Another Aramaic inscription, the Laghman II inscription, almost identical [to Laghman I inscription], was discovered nearby in the Laghman Valley, and published in 1974.

-- Aramaic Inscription of Laghman, by Wikiwand

The translation is slightly incomplete but brings some valuable indications. It first mentions the propagation of moral rules, which Ashoka will call "Dharma" in his Edicts of Ashoka, consisting of the abandonment of vanity and respect for the life of the people and animals (here, urging people to give up fishing).

Then, according to semitologist André Dupont-Sommer, who made a detailed analysis of the script observed in multiple rock inscriptions in the Laghman valley as well as in other Aramaic inscriptions of Ashoka,[5] the inscription mentions the city of Tadmor (Tdmr in the Aramaic script in the inscription, ie Palmyra), destination of the great commercial road leading from India to the Mediterranean basin, located at a distance of 3800 km. According to the reading of Dupont-Sommer, Palmyra is separated by two hundreds "bows" from Laghman.

-- Aramaic Inscription of Laghman, by Wikipedia

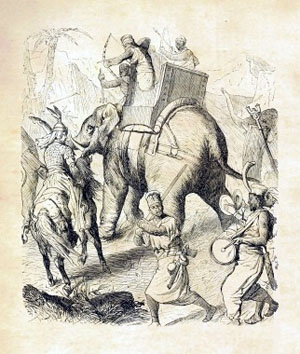

It is subsequently also identified as the source of the ivory used in Darius' palace at Susa.

Only a few sources mention his activities in India. Chandragupta (known in Greek sources as Sandrokottos), founder of the Mauryan empire, had conquered the Indus valley and several other parts of the easternmost regions of Alexander's empire. Seleucus began a campaign against Chandragupta and crossed the Indus. Most western historians note that it appears to have fared poorly as he did not achieve his goals, even though what exactly happened is unknown. The two leaders ultimately reached an agreement, and through a treaty sealed in 305 BC, Seleucus abandoned the territories he could never securely hold in exchange for stabilizing the East and obtaining elephants, with which he could turn his attention against his great western rival, Antigonus Monophthalmus. The 500 war elephants Seleucus obtained from Chandragupta were to play a key role in the forthcoming battles, particularly at Ipsus against Antigonus and Demetrius.

-- Seleucus I Nicator, by Wikipedia

In the Behistun inscription (DB 3.54-76), the King recounts that a Persian was thrice defeated by the Achaemenid governor of Arachosia, Vivana, who so ensured that the province remained under Darius' control. It has been suggested that this "strategically unintelligible engagement" was ventured by the rebel because "there were close relations between Persia and Arachosia concerning the Zoroastrian faith."[1]

Alexander the Great in Arachosia, 329 BCE.

The chronologically next reference to Arachosia comes from the Greeks and Romans, who record that under Darius III the Arachosians and Drangians were under the command of a governor who, together with the army of the Bactrian governor, contrived a plot of the Arachosians against Alexander (Curtius Rufus 8.13.3). Following Alexander's conquest of the Achaemenids, the Macedonian appointed his generals as governors (Arrian 3.28.1, 5.6.2; Curtius Rufus 7.3.5; Plutarch, Eumenes 19.3; Polyaenus 4.6.15; Diodorus 18.3.3; Orosius 3.23.1 3; Justin 13.4.22).

Following the Partition of Babylon, the region became part of the Seleucid Empire, which traded it to the Mauryan Empire in 305 BCE as part of an alliance. The Shunga dynasty overthrew the Mauryans in 185 BC, but shortly afterwards lost Arachosia to the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. It then became part of the break-away Indo-Greek Kingdom in the mid 2nd century BCE. Indo-Scythians expelled the Indo-Greeks by the mid 1st century BCE, but lost the region to the Arsacids and Indo-Parthians. At what time (and in what form) Parthian rule over Arachosia was reestablished cannot be determined with any authenticity. From Isidore 19 it is certain that a part (perhaps only a little) of the region was under Arsacid rule in the 1st century CE, and that the Parthians called it Indikē Leukē, "White India."[5]

The Kushans captured Arachosia from the Indo-Parthians and ruled the region until around 230 CE, when they were defeated by the Sassanids, the second Persian Empire, after which the Kushans were replaced by Sassanid vassals known as the Kushanshas or Indo-Sassanids. In 420 CE the Kushanshas were driven out of present Afghanistan by the Chionites, who established the Kidarite Kingdom. The Kidarites were replaced in the 460s CE by the Hephthalites, who were defeated in 565 CE by a coalition of Persian and Turkish armies. Arachosia became part of the surviving Kushano-Hephthalite Kingdoms of Kapisa, then Kabul, before coming under attack from the Moslem Arabs. These kingdoms were at first vassals of Sassanids. Around 870 CE the Kushano-Hephthalites (aka Turkshahi Dynasty) was replaced by the Saffarids, then the Samanid Empire and Muslim Turkish Ghaznavids in the early 11th century CE.

Arab geographers referred to the region (or parts of it) as 'Arokhaj', 'Rokhaj', 'Rohkaj' or simply 'Roh'.

Theory of Croatian Iranian origin

The theory of Croatian origin traces the origin of the Croats to the area of Arachosia. This connection was at first drawn due to the similarity of Croatian (Croatia - Croatian: Hrvatska, Croats - Croatian: Hrvati / Čakavian dialect: Harvati / Kajkavian dialect: Horvati) and Arachosian name,[6][7] but other researches indicate that there are also linguistic, cultural, agrobiological and genetic ties.[8][9] Since Croatia became an independent state in 1991, the Iranian theory gained more popularity, and many scientific papers and books have been published.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

See also

• Old Kandahar

Ancient city of Old Kandahar (red) on the western side of Kandahar

Old Kandahar (locally known as Zorr Shaar; Pashto: زوړ ښار, meaning "Old City") is a historical section of the city of Kandahar in southern Afghanistan. It is thought its foundation was laid out by Alexander the Great in 330 BC under the name Alexandria Arachosia. and served as the local seat of power for many rulers in the last 2,000 years. It became part of many empires, including the Mauryans (322 BC–185 BC), Indo-Scythians (200 BC–400 AD), Sassanids, Arabs, Zunbils, Saffarids, Ghaznavids, Ghorids, Timurids, Mughals, Safavids, and others. It was one of the main cities of Arachosia, a historical region sitting in Greater Iran's southeastern lands and was also in contact with the Indus Valley Civilization. The city has been a frequent target for conquest because of its strategic location in Southern Asia and Central Asia, controlling the main trade route linking the Indian subcontinent with the Middle East, the rest of Central Asia and the Persian Gulf.

-- Old Kandahar, by Wikipedia

Notes

1. Schmitt, Rüdiger (August 10, 2011). "Arachosia". Encyclopædia Iranica. United States.

2. Lendering, Jona. "Alexandria in Arachosia". Amsterdam: livius.org..

3. Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4 ed.). Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 173. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

4. Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936. 2. BRILL. p. 150. ISBN 90-04-08265-4. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

5. The Greeks in Bactria and India. Cambridge University Press. 2010-06-24. ISBN 978-1-108-00941-6. Retrieved 2007-12-31.

6. "Identity of Croatians in Ancient Afghanistan". iranchamber.com..

7. Kalyanaraman, Srinivasan. "Sarasvati Civilization Volume 1". Bangalore: Babasaheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti. .

8. Budimir/Rac, Stipan/Mladen. "Anthropogenic and agrobiological arguments of the scientific origin of Croats". Zagreb: Staroiransko podrijetlo Hrvata : zbornik simpozija / Lovrić, Andrija-Željko (ed). - Teheran : Iranian Cultural Center. .

9. Abbas, Samar. "Common Origin of Croats, Serbs and Jats". Bhubaneshwar: iranchamber.com..

10. Beshevliev 1967: "Iranian elements in the Proto-Bulgarians" by V. Beshevliev (in Bulgarian)(Antichnoe Obschestvo, Trudy Konferencii po izucheniyu problem antichnosti, str. 237-247, Izdatel'stvo "Nauka", Moskva 1967, AN SSSR, Otdelenie Istorii) http://members.tripod.com/~Groznijat/fadlan/besh.html

11. Dvornik 1956: "The Slavs. Their Early History and Civilization." by F. Dvornik, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Boston, USA., 1956.

12. Hina 2000: "Scholars assert Croats are Descendants of Iranian Tribes", Hina News Agency, Zagreb, Oct 15, 2000 (http://www.hina.hr)

13. Sakac 1949: "Iranisehe Herkunft des kroatischen Volksnamens", ("Iranian origin of the Croatian Ethnonym") S. Sakac, Orientalia Christiana Periodica. XV (1949), 813-340.

14. Sakac 1955: "The Iranian origin of the Croatians according to Constantine Porphyrogenitus", by S. Sakac, in "The Croatian nation in its struggle for freedom and independence" (Chicago, 1955); for other works by Sakac, cf. "Prof. Dr. Stjepan Krizin Sakac - In memoriam" by Milan Blazekovic, http://www.studiacroatica.com/revistas/ ... tmArchived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

15. Schmitt 1985: "Iranica Proto-Bulgarica" (in German), Academie Bulgare des Sciences, Linguistique Balkanique, XXVIII (1985), l, p.13-38; http://members.tripod.com/~Groznijat/bu ... hmitt.html

16. Tomicic 1998: "The old-Iranian origin of Croats", Symposium proceedings, Zagreb 24.6.1998, ed. Prof. Zlatko Tomicic & Andrija-Zeljko Lovric, Cultural center of I.R. of Iran in Croatia, Zagreb, 1999, ISBN 953-6301-07-5, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-12. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

17. Vernadsky 1952: "Der sarmatische Hintergrund der germanischen Voelkerwanderung," (Sarmatian background of the Germanic Migrations), G. Vernadsky, Saeculum, II (1952), 340-347.

References

• Frye, Richard N. (1963). The Heritage of Persia. World Publishing company, Cleveland, Ohio. Mentor Book edition, 1966.

• Hill, John E. 2004. The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Draft annotated English translation.

• Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation.

• Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

• Toynbee, Arnold J. (1961). Between Oxus and Jumna. London. Oxford University Press.

• Vogelsang, W. (1985). "Early historical Arachosia in South-east Afghanistan; Meeting-place between East and West." Iranica antiqua, 20 (1985), pp. 55–99.

External links

• Arachosia

• Alexandria in Arachosia

• ARACHOSIA, province (satrapy)

• King, Rhyne (2019). "Taxing Achaemenid Arachosia: Evidence from Persepolis". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 78 (2): 185–199. doi:10.1086/705163. S2CID 211659841.