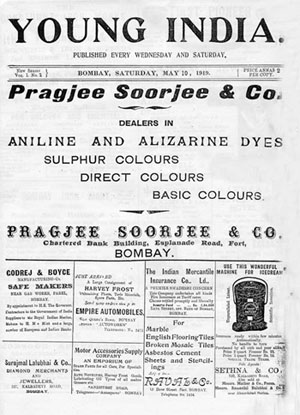

by India International Centre Quarterly Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 55-57 (3 pages)

Notes & News

January 1976

-- Lumbini On Trial: The Untold Story, Lumbini Is An Astonishing Fraud Begun in 1896, by T. A. Phelps

-- The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars, by John Irwin

-- The Asoka Pillars: A Challenging Interpretation, by India International Centre Quarterly

-- The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer: An Archaeological Scandal, by Charles Allen]-- The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer: An Archaeological Scandal, by Charles Allen

Highlights:

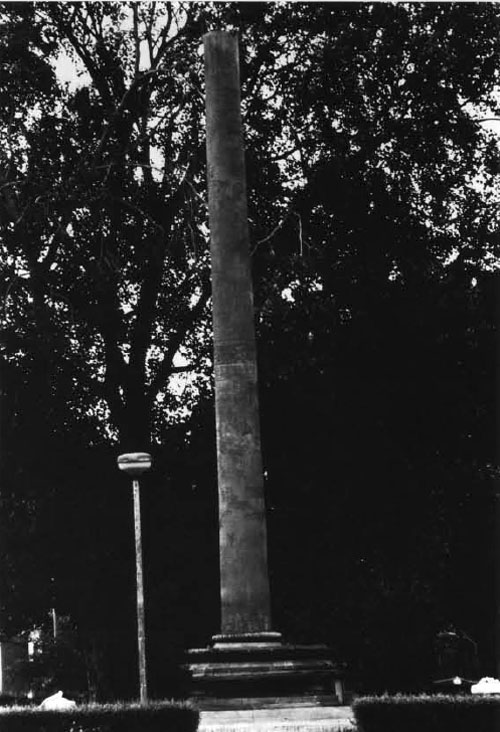

Mr. Irwin rejected the long-standing claim that all these pillars had been commissioned at the personal behest of Asoka in order to bear edicts propagating his Dharma Of 'Law'....According to Mr. Irwin there was evidence to show that a number of the pillars were pre-Asokan, and that they represented not the beginnings of monumental art in India, but the culmination of a much more ancient tradition evolved on Indian soil. "The key to their history" he said, "is a cult of pillar as axis of the universe. The cult was more or less universal in the ancient world, and it was central to the early religious experience of man -- So much so that its influences are imprinted upon all later religions. The pillars traditionally called Asokan represent a significant survival of those influences".

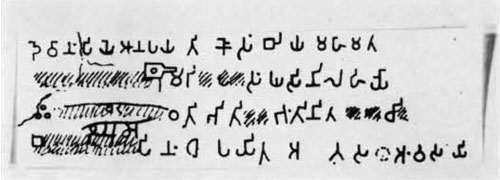

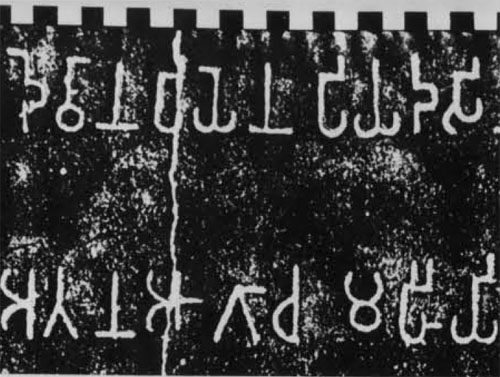

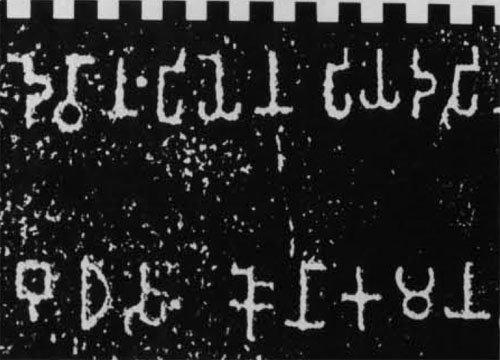

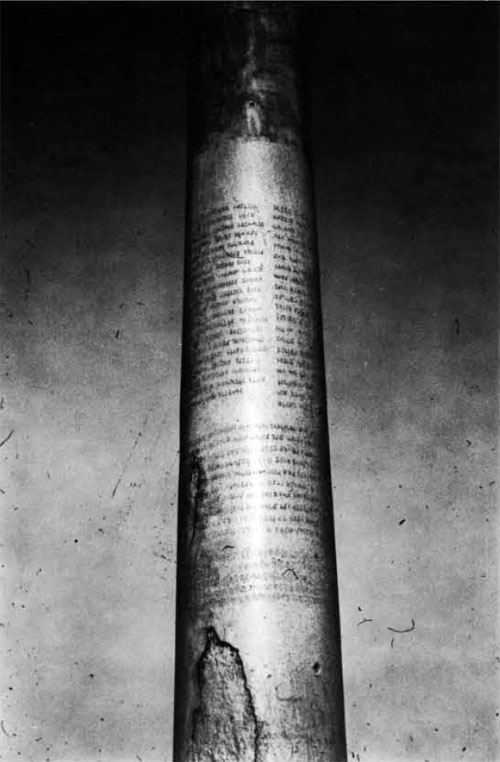

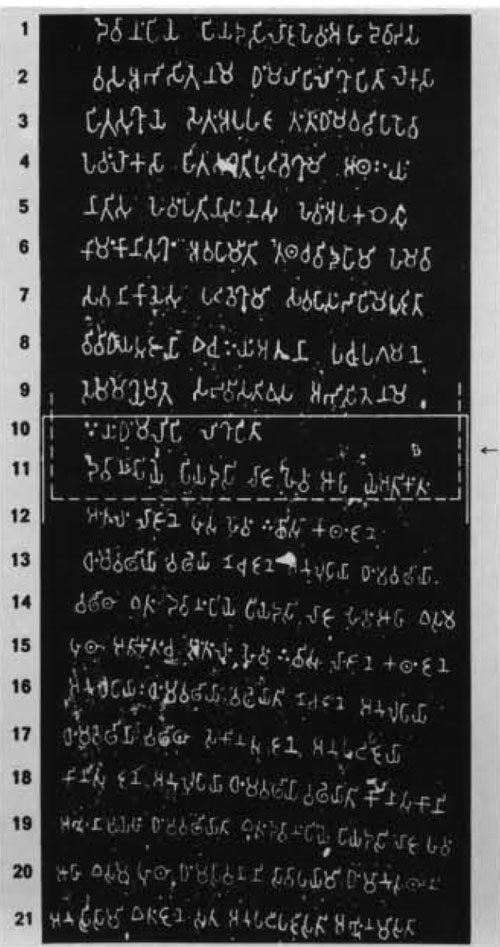

He traced how the pillars had come to be called 'Asokan' in the first place. The story, he said, began in 1834 when James Prinsep unlocked the mystery of the Asokan script, forgotten for 2,000 years. The first inscription deciphered by him happened to be found on the shaft of a pillar then lying topless on the ground al Allahabad, and with the identification of its signatory as Asoka, the concept of an 'Asokan pillar' was born.

"At that time, nobody stopped to consider the implications of Asoka's 7th Edict, which instructed that his message should be engraved on stone pillars already standing. They were also unaware that, in spite of Asoka's order, a number of the pillars subsequently discovered would turn out to have no inscriptions at all. The fact that an Asokan inscription appeared at all on a pillar led to the uncritical assumption that all pillars of this artistic genre had been erected by Asoka....

His own starting-point, he said, was the opposite of all previous investigators, "Whereas they had begun by assuming that an Asokan inscription on a pillar was prima facie evidence of Asokan origin, mine is to say: Don't let's assume any pillar was erected by Asoka unless there is positive proof to that effect." On this basis, Mr. Irwin said there were only two. Both happen to be topless shafts found near the Indo-Nepal border, in the region where the Buddha-to-be was born. We know that Asoka erected them because their inscriptions say so. However, as mere stumps they are of no help to the art historian. "As to the remaining fourteen 'Asokan pillars' which have survived in whole or in part, nobody had so far even tried to prove that any of them were actually erected by Asoka. Nor has anyone explained why, in spite of Asoka's orders, a number of them were not inscribed at all. The latter question becomes more pertinent when it is realized that Asoka's instructions were issued twice (once near the beginning and once near the end of his reign), and also that one of the uninscribed pillars still stands today within a short distance of his capital city, Pataliputra (modern Patna).

"Are we to assume that the orders of this autocratic monarch were deliberately flouted for a quarter of a century by subjects living within a a day's walk of his place? and, if so, why?...

The truth will gradually transpire as we go along, and by the end we shall have a new insight into what so-called 'Asokan pillars' are all about.

"In the course of our enquiries we shall have a lot to learn about the cult of the cosmic axis or axis mundi...

"That such a cult flourished in the Ganges basin long before Asoka -- and before even Buddhism and the Indo-Aryans -- can be proved beyond doubt, I believe."...

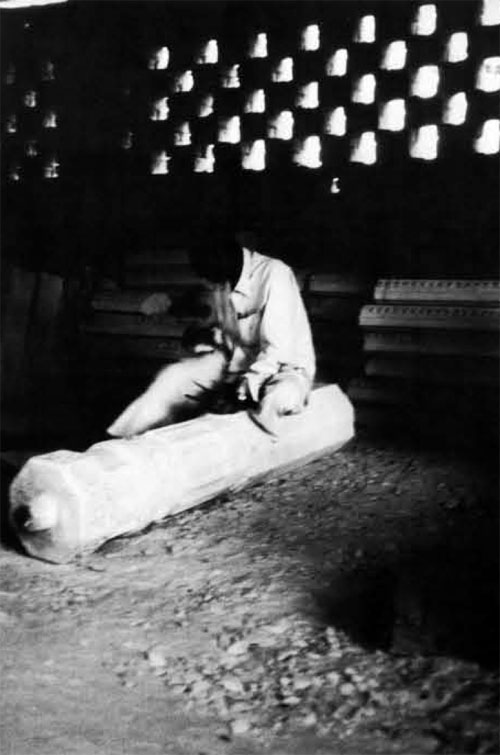

The manner of erecting free standing pillars varied greatly and Mr. Irwin argued that such pillars belonged to a much earlier date.

Pillars such as those at Sankhisa and Rampurva which possessed elephant and bull capitals were, he asserted, of pre-Buddhist origin. And both these animals were fertility symbols of an earlier cult. Pillars which were fitted into stone shafts were of a later date since they bore Asokan inscriptions...

Moreover, he argued that the pillars ascribed to Asoka differed from each other and therefore failed to present a homogenous activity which should have existed had they been erected around the same period...

The idea of a cosmic pillar was used by Indian monarchs, he said, to identify their power with the maintenance of cosmic order.

-- The Asoka Pillars: A Challenging Interpretation, by India International Centre Quarterly, 1976

Mr. John Irwin, Head of the Oriental Department, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, visited India on a British Academy travel fellowship and gave a series of lectures at the National Museum, entitled 'Foundations of Indian Art '. He also delivered two of these lectures at the India International Centre on January 20 and 21, 1976.

THE CENTRAL theme of John Irwin's lectures was to propound a new and challenging interpretation of the famous pillars traditionally called 'Asokan'. Briefly Mr. Irwin rejected the long-standing claim that all these pillars had been commissioned at the personal behest of Asoka in order to bear edicts propagating his Dharma Of 'Law'. He also disassociated himself from the theory of leading European scholars of the last hundred years, from Vincent Smith to Sir Mortimer Wheeler, that these pillars were modelled on Perso-Hellenistic prototypes. Instead he saw the pillars as "religious in function and Indian in form and style". According to Mr. Irwin there was evidence to show that a number of the pillars were pre-Asokan, and that they represented not the beginnings of monumental art in India, but the culmination of a much more ancient tradition evolved on Indian soil. "The key to their history" he said, "is a cult of pillar as axis of the universe. The cult was more or less universal in the ancient world, and it was central to the early religious experience of man -- So much so that its influences are imprinted upon all later religions. The pillars traditionally called Asokan represent a significant survival of those influences".

He traced how the pillars had come to be called 'Asokan' in the first place. The story, he said, began in 1834 when James Prinsep unlocked the mystery of the Asokan script, forgotten for 2,000 years. The first inscription deciphered by him happened to be found on the shaft of a pillar then lying topless on the ground al Allahabad, and with the identification of its signatory as Asoka, the concept of an 'Asokan pillar' was born.

Until about a hundred years ago in India, Ashoka was merely one of the many kings mentioned in the Mauryan dynastic list included in the Puranas. Elsewhere in the Buddhist tradition he was referred to as a chakravartin/ cakkavatti, a universal monarch, but this tradition had become extinct in India after the decline of Buddhism. However, in 1837, James Prinsep deciphered an inscription written in the earliest Indian script since the Harappan, brahmi. There were many inscriptions in which the King referred to himself as Devanampiya Piyadassi (the beloved of the gods, Piyadassi). The name did not tally with any mentioned in the dynastic lists, although it was mentioned in the Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka. Slowly the clues were put together but the final confirmation came in 1915, with the discovery of yet another version of the edicts in which the King calls himself Devanampiya Ashoka.

-- The Penguin History of Early India: From the Origins to A.D. 1300, by Romila Thapar

In a study of the Mauryan period a sudden flood of source material becomes available. Whereas with earlier periods of Indian history there is a frantic search to glean evidence from sources often far removed and scattered, with the Mauryan period there is a comparative abundance of information, from sources either contemporary or written at a later date.

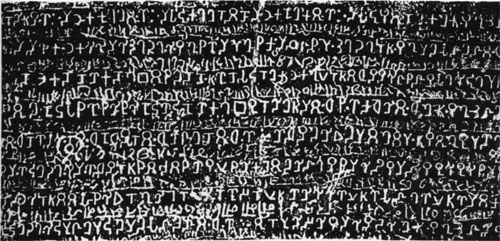

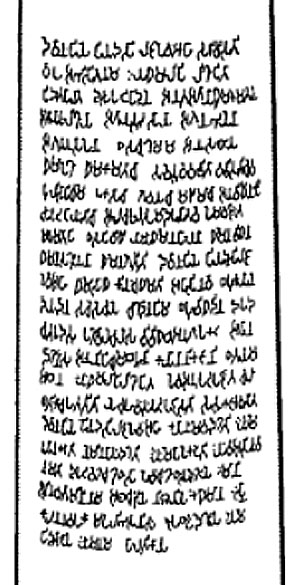

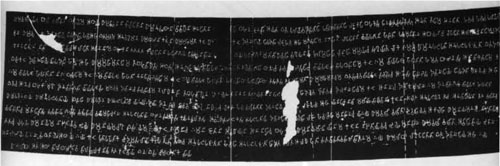

This is particularly the case with the reign of Aśoka Maurya, since, apart from the unintentional evidence of sources such as religious literature, coins, etc., the edicts of the king himself, inscribed on rocks and pillars throughout the country, are available. These consist of fourteen major rock edicts located at Kālsi, Mānsehrā, Shahbāzgarhi, Girnār, Sopārā, Yeṟṟaguḍi, Dhauli, and Jaugaḍa; and a number of minor rock edicts and inscriptions at Bairāṭ, Rūpanāth, Sahasrām, Brahmagiri, Gāvimath, Jaṭiṅga-Rāmeshwar, Maski, Pālkīguṇḍu, Rajūla-Maṇḍagiri, Siddāpura, Yeṟṟaguḍi, Gujarra and Jhansi. Seven pillar edicts exist at Allahabad, Delhi-Toprā, Delhi-Meerut, Lauriyā-Ararāja, Lauriyā-Nandangarh, and Rāmpūrvā. Other inscriptions have been found at the Barābar Caves (three inscriptions), Rummindei, Nigali-Sāgar, Allahabad, Sanchi, Sārnāth, and Bairāṭ. Recently a minor inscription in Greek and Aramaic was found at Kandahar.

The importance of these inscriptions could not be appreciated until it was ascertained to whom the title ‘Piyadassi’ referred, since the edicts generally do not mention the name of any king; an exception to this being the Maski edict, which was not discovered until very much later in 1915. The earliest publication on this subject was by Prinsep, who was responsible for deciphering the edicts. At first Prinsep identified Devanampiya Piyadassi with a king of Ceylon, owing to the references to Buddhism. There were of course certain weaknesses in this identification, as for instance the question of how a king of Ceylon could order the digging of wells and the construction of roads in India, which the author of the edicts claims to have done. Later in the same year, 1837, the Dīpavaṃsa and the Mahāvaṃsa, two of the early chronicles of the history of Ceylon, composed by Buddhist monks, were studied in Ceylon, and Prinsep was informed of the title of Piyadassi given to Aśoka in those works. This provided the link for the new and correct identification of Aśoka as the author of the edicts.

-- Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, by Romila Thapar

Legends about past lives

Buddhist legends mention stories about Ashoka's past lives. According to a Mahavamsa story, Ashoka, Nigrodha and Devnampiya Tissa were brothers in a previous life. In that life, a pratyekabuddha was looking for honey to cure another, sick pratyekabuddha. A woman directed him to a honey shop owned by the three brothers. Ashoka generously donated honey to the pratyekabuddha, and wished to become the sovereign ruler of Jambudvipa for this act of merit. The woman wished to become his queen, and was reborn as Ashoka's wife Asandhamitta. Later Pali texts credit her with an additional act of merit: she gifted the pratyekabuddha a piece of cloth made by her. These texts include the Dasavatthuppakarana, the so-called Cambodian or Extended Mahavamsa (possibly from 9th–10th centuries), and the Trai Bhumi Katha (15th century).

According to an Ashokavadana story, Ashoka was born as Jaya in a prominent family of Rajagriha. When he was a little boy, he gave the Gautama Buddha dirt imagining it to be food. The Buddha approved of the donation, and Jaya declared that he would become a king by this act of merit. The text also state that Jaya's companion Vijaya was reborn as Ashoka's prime-minister Radhagupta. In the later life, the Buddhist monk Upagupta tells Ashoka that his rough skin was caused by the impure gift of dirt in the previous life. Some later texts repeat this story, without mentioning the negative implications of gifting dirt; these texts include Kumaralata's Kalpana-manditika, Aryashura's Jataka-mala, and the Maha-karma-vibhaga. The Chinese writer Pao Ch'eng's Shih chia ju lai ying hua lu asserts that an insignificant act like gifting dirt could not have been meritorious enough to cause Ashoka's future greatness. Instead, the text claims that in another past life, Ashoka commissioned a large number of Buddha statues as a king, and this act of merit caused him to become a great emperor in the next life.

The 14th century Pali-language fairy tale Dasavatthuppakarana (possibly from c. 14th century) combines the stories about the merchant's gift of honey, and the boy's gift of dirt. It narrates a slightly different version of the Mahavamsa story, stating that it took place before the birth of the Gautama Buddha. It then states that the merchant was reborn as the boy who gifted dirt to the Buddha; however, in this case, the Buddha his attendant to Ānanda to create plaster from the dirt, which is used repair cracks in the monastery walls....

Rediscovery

Ashoka had almost been forgotten, but in the 19th century James Prinsep contributed in the revelation of historical sources. After deciphering the Brahmi script, Prinsep had originally identified the "Priyadasi" of the inscriptions he found with the King of Ceylon Devanampiya Tissa. However, in 1837, George Turnour discovered an important Sri Lankan manuscript (Dipavamsa, or "Island Chronicle") associating Piyadasi with Ashoka:"Two hundred and eighteen years after the beatitude of the Buddha, was the inauguration of Piyadassi, .... who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and the son of Bindusara, was at the time Governor of Ujjayani."

— Dipavamsa.[34]

-- Ashoka, by Wikipedia

[I would like at this point to pay belated acknowledgement to my respected friend and colleague, Karl Khandalawala, which whom I have sometimes expressed differences of interpretation, in this case in opposing his view (which on hindsight appears to be entirely correct) that the Sarnath pillar reveals the influences of foreign (Achaemenid) influence. I hope this eminent art historian will now accept my personal apology and withdrawal. On this particular issue I am ready to admit that he was right, though I reserve my differences on other issues involving Asokan pillars. A further issue reflecting his correctness is embodied in the self-styled title Asoka used as the opening words of many of his inscriptions (Devanampiya Piyadassi), often translated as 'Beloved of the Gods." A century ago, this term was rightly recognised by the brilliant French Indologist Emile Senart, as borrowed from earlier Achaemenid inscriptions in Persia, yet since then ignored by all authorities writing on Asoka in English.]

-- The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars, by John Irwin

"At that time, nobody stopped to consider the implications of Asoka's 7th Edict, which instructed that his message should be engraved on stone pillars already standing. They were also unaware that, in spite of Asoka's order, a number of the pillars subsequently discovered would turn out to have no inscriptions at all. The fact that an Asokan inscription appeared at all on a pillar led to the uncritical assumption that all pillars of this artistic genre had been erected by Asoka. And since the ornament of the capitals included floral motifs reminiscent of the Greek anthemion or 'honey suckle-pattern', it was too readily assumed that the pillars embodied Greek influence. Nobody paused to consider whether the 'honeysuckle-pattern' was really Greek in the first place, or whether the Greeks might not themselves have been borrowers."

After summarizing the whole course of thinking on 'Asokan pillars' over the last 150 years, Mr. Irwin then threw down his gauntlet, inviting the audience "to forget everything said and thought hitherto and to follow me on an entirely different track."

His own starting-point, he said, was the opposite of all previous investigators, "Whereas they had begun by assuming that an Asokan inscription on a pillar was prima facie evidence of Asokan origin, mine is to say: Don't let's assume any pillar was erected by Asoka unless there is positive proof to that effect." On this basis, Mr. Irwin said there were only two. Both happen to be topless shafts found near the Indo-Nepal border, in the region where the Buddha-to-be was born. We know that Asoka erected them because their inscriptions say so. However, as mere stumps they are of no help to the art historian. "As to the remaining fourteen 'Asokan pillars' which have survived in whole or in part, nobody had so far even tried to prove that any of them were actually erected by Asoka. Nor has anyone explained why, in spite of Asoka's orders, a number of them were not inscribed at all. The latter question becomes more pertinent when it is realized that Asoka's instructions were issued twice (once near the beginning and once near the end of his reign), and also that one of the uninscribed pillars still stands today within a short distance of his capital city, Pataliputra (modern Patna).

"Are we to assume that the orders of this autocratic monarch were deliberately flouted for a quarter of a century by subjects living within a a day's walk of his place? and, if so, why?

"When I began researching in this field, I thought up a hypothetical answer. Perhaps (I argued with myself) the pillars were left uninscribed because they were under worship in a non-Buddhist context -- in which case it might have been unseemly for Asoka, the great advocate of religious tolerance, to impose edicts propagating his own personal interpretation of religious 'Law'.

"At this stage, I am not going to say whether this hypothesis was ultimately sustained in light of the research which followed. The value of a hypothesis is in the line of enquiry it opens up. In this case it turned out to be an exciting one ........ The truth will gradually transpire as we go along, and by the end we shall have a new insight into what so-called 'Asokan pillars' are all about.

"In the course of our enquiries we shall have a lot to learn about the cult of the cosmic axis or axis mundi, which specialists in the history of religion are now enabling us to recognize as central to the pre-history of religion, more or less throughout the world. This is a relatively new branch of study of profound importance to the understanding of the origins of art -- and much else besides.

"That such a cult flourished in the Ganges basin long before Asoka -- and before even Buddhism and the Indo-Aryans -- can be proved beyond doubt, I believe."

In the cult of tile axis mundi, the pillar served as a link between the terrestrial and the celestial areas, emerging from the primordial waters and pointing heavenwards. The pillar, he said, was not conceived to stand alone but was usually accompanied by a sacred tree -- peepul, neem avasttha -- and the sacred mound or stupa, representing the cosmic triad. Such pillars were originally wooden and were probably identical to the Indradhwaja or portable standard, and the Vedic yupa. The manner of erecting free standing pillars varied greatly and Mr. Irwin argued that such pillars belonged to a much earlier date.

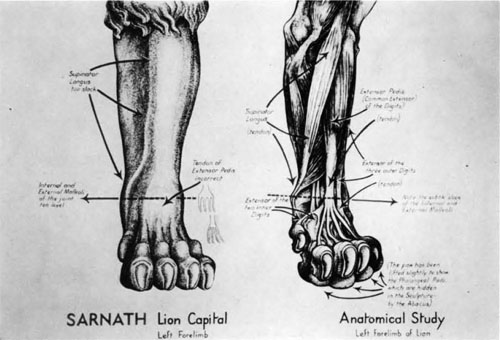

Pillars such as those at Sankhisa and Rampurva which possessed elephant and bull capitals were, he asserted, of pre-Buddhist origin. And both these animals were fertility symbols of an earlier cult. Pillars which were fitted into stone shafts were of a later date since they bore Asokan inscriptions and were crowned by the heraldic lion capital for example, those at Sanchi, Lauriya Nandangarh, Rampurva, Gothihawa and Topra. The lion denoting temporal authority, was, he said, of West Asian origin. It reached India around fourth century BC and could have been adopted by Asoka or by the preceding Nanda dynasty. Moreover, he argued that the pillars ascribed to Asoka differed from each other and therefore failed to present a homogenous activity which should have existed had they been erected around the same period.

The other focal points of Mr. Irwin's lectures concerned the 'inverted lotus' and the reliefs depicted on the abacus on top of the pillar. He maintained that the capitals of the early wooden pillar had been fashioned from gilded copper and were then attached to the top of the wooden pillar. In order to prevent the shaft from splitting under the weight of the capital, fabric and rope were bound around it. When translated into stone this came to resemble the inverted lotus. Mr. Irwin disagreed with the view that the floral relief carved on the abacus had been derived from the Greek 'honeysuckle' pattern. According to his interpretation, the floral relief represented the Egyptian 'blue lotus' -- a water symbol which reached India in the centuries preceding Asoka. The common goose also depicted on the abacus symbolized the hamsa which was the traditional symbol of the union between the individual and the cosmic. Along with the chakra, symbolizing the sun, the lotus, depicting unfolding life, the goose, he said, is part of the primeval myth of creation.

The idea of a cosmic pillar was used by Indian monarchs, he said, to identify their power with the maintenance of cosmic order. Mr. Irwin claimed that although India shared the cult of axis mundi with other ancient civilizations, she had evolved her own meaning and form for it, and foreign craftsman had in no way contributed to its construction as has hitherto been believed.

The style of the Sarnath inscription (fig. 13) recalls even more forcibly Princep's query about the Prayaga/Allahabad engraving: 'Why such carelessly cut letters on a shaft so regularly tapered and polished?' We now know that the Sarnath Pillar, in common with other 'Schism Pillars' already discussed, is among the first pillars inscribed by Asoka. Far from marking the culmination a a truly Asokan tradition (as I once supposed), it marked the beginning. Moreover, as now seems to be clear, it was inaugurated under the tutelage of craftsmen formerly employed in the Perso-Hellenistic tradition of the Achaemenid dynasty, who had apparently been brought to India by Asoka especially for that purpose.12 [I would like at this point to pay belated acknowledgement to my respected friend and colleague, Karl Khandalawala, which whom I have sometimes expressed differences of interpretation, in this case in opposing his view (which on hindsight appears to be entirely correct) that the Sarnath pillar reveals the influences of foreign (Achaemenid) influence. I hope this eminent art historian will now accept my personal apology and withdrawal. On this particular issue I am ready to admit that he was right, though I reserve my differences on other issues involving Asokan pillars. A further issue reflecting his correctness is embodied in the self-styled title Asoka used as the opening words of many of his inscriptions (Devanampiya Piyadassi), often translated as 'Beloved of the Gods." A century ago, this term was rightly recognised by the brilliant French Indologist Emile Senart, as borrowed from earlier Achaemenid inscriptions in Persia, yet since then ignored by all authorities writing on Asoka in English.]

-- The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars, by John Irwin