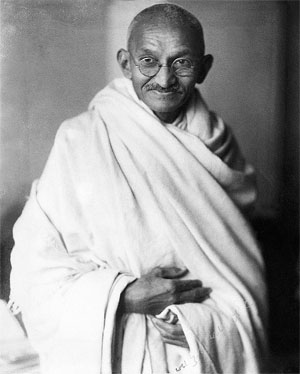

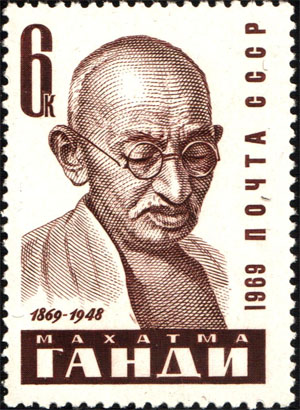

Mahatma Gandhi

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/1/21

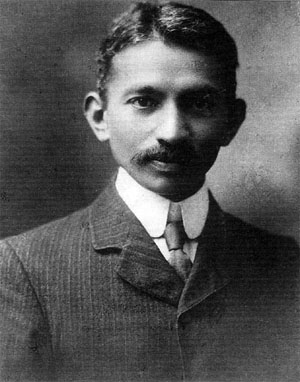

Meanwhile, in October 1906, there was an interesting encounter between two individuals in London. They were to be political rivals for several decades thereafter, and their respective ideologies were to divide Indian polity irrevocably. This was when Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi came calling to India House and met Vinayak Damodar Savarkar.

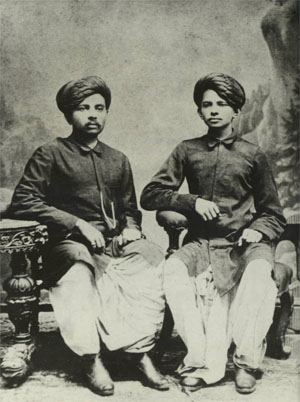

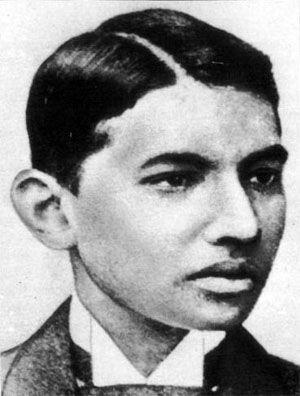

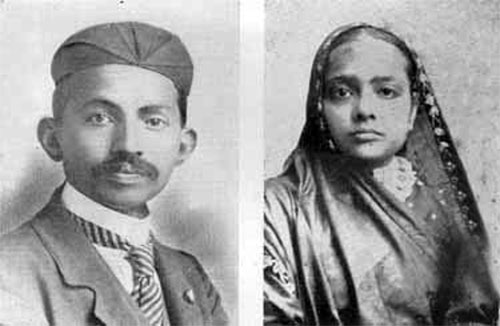

In 1893, Gandhi had gone to South Africa as a young twenty-four-year-old lawyer. He was there on a temporary assignment, to settle a commercial dispute for an Indian trader. A year after his arrival, the court ruled in favour of his client. Just when he was preparing to return to India, a group of Indian merchants requested him to stay on and fight a bill before the Natal Assembly, a British colony, seeking to remove Indians from the voters’ list. Within a month, more than 10,000 signatures had been gathered and presented to the colonial secretary, Lord Ripon. The bill was temporarily set aside, but eventually passed as law in 1896, disqualifying voters of non-European origin. These events serendipitously catapulted Gandhi into the role of an unofficial campaigner for the rights of the disenfranchised.

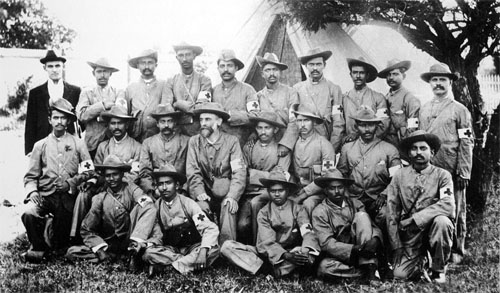

While Shyamji was aware and appreciative of Gandhi’s work, he was deeply critical of the latter’s role in the Anglo-Boer War. The war broke out in 1899 between the British Empire and the Boers of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. The Boers, or Afrikaners, were the descendants of original Dutch settlers of southern Africa. Following skirmishes with the British, they moved away to form their own independent republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. They lived peacefully with the British colonizers in their neighbourhood, till the discovery of diamonds and gold in the region aroused British avarice. The Boers offered a rigorous resistance to the British colonists in Natal and Cape Colony. Indians too were called upon to take sides. While Gandhi mentions that his ‘personal sympathies were all with the Boers’, his ‘loyalty to the British rule’ drove him ‘to participation with the British in that war’. His argument was:I felt that, if I demanded rights as a British citizen, it was also my duty as such, to participate in the defence of the British Empire. I held then that India could achieve her complete emancipation only within and through the British Empire.[/size] So I collected to gather as many comrades as possible, and with very great difficulty got their services accepted as an ambulance corps.49

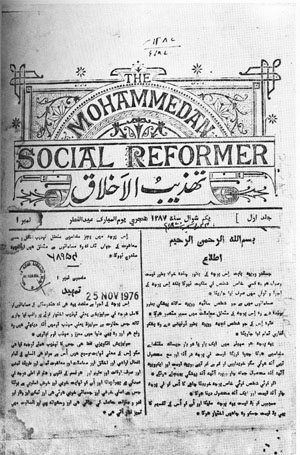

More than 500 Indians had signed up for the Indian Ambulance Corps and attended the wounded British soldiers at Spioenkop in Natal. Gandhi and others received war medals for their chivalry and loyalty to the Queen. In June 1903, Gandhi began a weekly called Indian Opinion —originating in four languages (English, Hindi, Gujarati and Tamil)—as a mouthpiece for the Indian community.

Despite his own non-confrontationist attitude with the British, Shyamji was critical of the support that Gandhi and the Indians gave to the British against the native Boers. Some of Gandhi’s critical and racist comments against the ‘blacks’ of Africa too drew the ire of the Indian Sociologist. Addressing the native Africans by a derogatory term ‘Kaffir’, Gandhi had demanded separate entrances for whites and blacks at the Durban post office and had objected to Indians being classed with the South African black natives. In Gandhi’s own words:Ours is one continual struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.50. . . Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilized . . . they are troublesome, very dirty, and live almost like animals.51

Just before Gandhi’s visit to India House in 1906, the Bambatha Rebellion was spearheaded by the Zulus protesting against unjust British taxes after the Boer War. Thousands of Zulus were ruthlessly massacred and several injured. Here too Gandhi supported the British and requested them to recruit Indians in the British army fighting against the Zulus. In the July 1906 issue of the Indian Sociologist, Gandhi was bitterly criticized for his role in aiding the suppression and massacre of the Zulu rebels.

It was against this strained background with Shyamji on political ideology that Gandhi visited India House on 20 October 1906. Writing about Shyamji, Gandhi says:He has founded India House at his own cost. Any Indian student is allowed to stay there against a very small weekly payment. All Indians, whether Hindus, Muslims or others can and do stay there. There is full freedom for everyone in the matter of food and drink. Being situated in fine surroundings, the place has a very good atmosphere. On the first day of our arrival, both Mr Ally and I went to stay at India House, and we were very well looked after. But as our work requires our getting in touch with important people and as India House is rather remote, we have been obliged to come and live at his Hotel at great expense.52

While no record is extant of an exclusive meeting or the experiences that Vinayak and Gandhi had at the latter’s short stay at India House, Harindra Srivastava quotes an anecdote narrated to him by an eyewitness, Pandit Parmanandaji of Jhansi, a veteran freedom fighter. Vinayak was busy cooking his meal when Gandhi joined him to engage in a political discussion. Cutting him short, Vinayak asked him to first eat a meal with them. Gandhi was horrified to see the Chitpawan Brahmin cooking prawns, and being a staunch vegetarian refused to partake. Vinayak had apparently mocked him and retorted: ‘Well, if you cannot eat with us, how on earth are you going to work with us? Moreover . . . this is just boiled fish . . . while we want people who are ready to eat the British alive.’53 This was obviously not a great first meeting and their differences only widened with time....

The Dhingra episode echoed across different parts of the world for a long time. The newspaper, Vande Mataram, that Aurobindo Ghose and others were bringing out in Calcutta, was suppressed after the Alipore Bomb case. This was revived as The Bande Mataram—a Monthly Organ of Indian Independence by Madame Bhikaji Cama and Lala Har Dayal. The Indian revolutionaries in Paris had also started the ‘Paris India Society’. The very first issue of The Bande Mataram that was published in Geneva on 10 September 1909 was dedicated to Dhingra and his memory. In a tribute titled ‘Dhingra—the Immortal’, it said:Young India has produced another hero, whose words and deeds shall be cherished by the whole world for centuries to come. Dhingra’s declaration will be treasured in the archives of national and universal history as a precious heirloom for future generations. Dhingra has behaved at each stage of his trial like a hero of ancient times. He has reminded us of the history of Medieval Rajputs and Sikhs, who loved death like a bride. England thinks she has killed Dhingra: in reality, he lives forever and has given the death-blow to British sovereignty in India. Life immortal is his; who can take it away from him. All nations have watched Dhingra’s trial with bated breath, and have felt that New India is unconquerable because she can give birth to such heroic sons.

The Indian patriotic party, which has declared War of the Knife with England has issued a manifesto, in the course of which it says: ‘Dhingra has found out the secret of Life; he has discovered the path of Immortality. He has realized the highest destiny of Man . . . he has lifted himself above the common run of men and joined the company of the saints and heroes.’ These words sum up the attitude of India towards our patriot-martyr.

In time to come, when the British Empire in India shall have been reduced to ashes, Dhingra’s monument will adorn the squares of our chief towns, recalling to the memory of our children the noble life and the nobler death of him who laid down his life in a far-off land for the cause he loved so well. 142

The inaugural issue of Talwar, started by Virendranath Chattopadhyay from Paris in November 1909, also paid rich tributes to Dhingra.

But even though there was overwhelming support and appreciation for Dhingra in the months following his execution, there was an equal amount of condemnation of his act by several elements of the political spectrum. Leaders of the moderate wing of the Indian National Congress, quite like the eminent members of the Indian community of London, were deeply critical of Dhingra’s act. They believed that it decelerated the pace and tenor of the negotiations they had been having with the British for greater autonomy. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was stinging in his criticism of Dhingra. He wrote:It is being said in defence of Sir Curzon Wyllie’s assassination that it is the British who are responsible for India’s ruin, and that, just as the British would kill every German if Germany invaded Britain, so too it is the right of any Indian to kill any Englishman. Every Indian should reflect thoughtfully on this murder. It has done India much harm; the deputation’s efforts have also received a setback. But that need not be taken into consideration. It is the ultimate result that we must think of. Mr Dhingra’s defence is inadmissible. In my view, he has acted like a coward. All the same, one can only pity the man. He was egged on to do this act by ill-digested reading of worthless writings. His defence of himself, too, appears to have been learnt by rote. It is those who incited him to this that deserve to be punished. In my view, Mr. Dhingra himself is innocent. The murder was committed in a state of intoxication. It is not merely wine or bhang that makes one drunk; a mad idea also can do so. That was the case with Mr. Dhingra. The analogy of Germans and Englishmen is fallacious. If the Germans were to invade [Britain], the British would kill only the invaders. They would not kill every German whom they met. Moreover, they would not kill an unsuspecting German, or Germans who are guests. If I kill someone in my own house without a warning—someone who has done me no harm—I cannot but be called a coward. There is an ancient custom among the Arabs that they would not kill anyone in their own house, even if the person be their enemy. They would kill him after he had left the house and after he had been given time to arm himself. Those who believe in violence would be brave men if they observe these rules when killing anyone. Otherwise, they must be looked upon as cowards. It may be said that what Mr. Dhingra did, publicly and knowing full well that he himself would have to die, argues courage of no mean order on his part. But as I have said above, men can do these things in a state of intoxication, and can also banish the fear of death. Whatever courage there is in this is the result of intoxication, not a quality of the man himself. A man’s own courage consists in suffering deeply and over a long period. That alone is a brave act, which is preceded by careful reflection. I must say that those who believe and argue that such murders may do good to India are ignorant men indeed. No act of treachery can ever profit a nation. Even should the British leave in consequence of such murderous acts, who will rule in their place? The only answer is: the murderers. Who will then be happy? Is the Englishman bad because he is an Englishmen? Is it that everyone with an Indian skin is good?143

Despite the criticism of the revolutionary methods, it was no mere coincidence that on 15 November 1909 the government introduced the Indian Councils Act, popularly known as the Morley–Minto Reforms. It was way back in 1906 that Viceroy Lord Minto had prepared a minute arguing for a greater say of Indians in governance, given their rising education levels and awareness. Yet till the revolutionary movement caught steam and a spate of bombings and political assassinations shook both India and Britain, there was little progress on the reforms. Finally, the Act legitimized the election of Indians to various legislative councils across India for the first time. The reforms also granted the request of Muslim groups that had come together under the umbrella of the Muslim League, formed in 1906, demanding separate electorates for their community. This remained a bone of contention for a long time, till it spelt its ultimate disaster on the subcontinent.

In fact, Gandhi too acknowledged the reason for the rapid implementation of these administrative reforms. When asked in an interview, if the Secretary of State Lord Morley’s reforms were driven by the fear of the revolutionaries, Gandhi candidly admitted that: ‘The English are both a timid and a brave nation. England is, I believe, easily influenced by the use of gunpowder. It is possible that Lord Morley has granted the reforms through fear, but what is granted under fear can be retained only so long as the fear lasts.’144

The questioner was confused with the self-contradiction in the reply and pointed that out:Will you not admit that you are arguing against yourself? You know that what the English obtained in their own country they obtained by using brute force. I know you have argued that what they have obtained is useless, but that does not affect my argument. They wanted useless things and they got them. My point is that their desire was fulfilled. What does it matter what means they adopted? Why should we not obtain our goal, which is good, by any means whatsoever, even by using violence? Shall I think of the means when I have to deal with a thief in the house? My duty is to drive him out anyhow. You seem to admit that we have received nothing, and that we shall receive nothing, by petitioning. Why, then, may we not do so by using brute force? And, to retain what we may receive, we shall keep up the fear by using the same force to the extent that it may be necessary. You will not find fault with a continuance of force to prevent a child from thrusting its foot into fire? Somehow or other we have to gain our end.145

In response, he was given an extremely long-winding series of justifications, theological and philosophical constructs that largely contradicted each other, forcing him to move on to another question.

Exactly three years after their first meeting in October 1906, Gandhi met Vinayak again on 24 October 1909. The Indian community gathered to celebrate the festival of Vijayadashami, the tenth day following the nine-day festivities and fasting of Navaratri. To avoid British surveillance, Englishmen were also invited. Nearly seventy Indians participated. Gandhi was invited to preside over the meeting. He agreed on the condition that ‘no controversial politics were to be touched upon’146 and that he would rather speak on the greatness of the Ramayana. He was dressed in a swallow-tailed coat and stiff front shirt. In his address, Gandhi mentioned that the occasion of Vijayadashami that marked the victory of Lord Shri Ramachandra was a momentous one and that He needed to be honoured by every Indian as a historical personage. Gandhi went on:Everyone, whether Hindu, Muslim or Parsi, should be proud of belonging to a country, which produced a man like Shri Ramachandra. To the extent that he was a great Indian, he should be honoured by every Indian. For the Hindus, he is a god. If India again produced a Ramachandra, a Sita, a Lakshmana and a Bharata, she would attain prosperity in no time. It should be remembered, of course, that before Ramachandra qualified for public service, he suffered exile in the forest for 12 years. Sita went through extreme suffering and Lakshmana lived without sleep all those years and observed celibacy. When Indians learn to live in that manner, they can, from that instant count themselves as free men. India has no other way of achieving happiness for herself.147

It was then Vinayak’s turn to speak. Indirectly puncturing holes in Gandhi’s arguments, he said that it would be worthwhile to remember that Vijayadashami is preceded by a nine-day fast to propitiate Goddess Durga, who is a symbol of war and annihilation of evil. He concurred with Gandhi that Ramachandra was the life and soul of India but urged the audience to remember that even he could not establish Rama Rajya (his kingdom) without slaying Ravana who symbolized tyranny, aggression and injustice. If Ramachandra had merely sat on a fast, it was unlikely that his kingdom could have been established. He went on:Hindus are the heart of Hindustan. Nevertheless, just as the beauty of the rainbow is not impaired but enhanced by its varied hues, so also Hindustan will look all the more beautiful across the sky of future by assimilating all the best from the Muslim, Parsee, Jewish and other civilizations.148

Vinayak’s stirring speech won him many accolades from the audience. Barrister Asaf Ali who was present at the event described Vinayak as being as ‘fragile as an anemic girl, restless as a mountain torrent, and keen as the edge of a torpedo blade’. He later wrote that it was not an exaggeration to say that Vinayak was ‘one of the few really effective speakers I have known and heard, and there is hardly an orator of the first rank either here or in England whom I have not had the privilege of hearing’.149

The clash between the ideologies of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar had only just begun....

Meanwhile, by mid-1914, unrest was brewing in Europe. What began as a conflict between Austria–Hungary and Serbia, leading to the assassination of the Austrian archduke, Franz Ferdinand, at Sarajevo, soon mushroomed into a conflict that gripped all Europe and the world in four years of strategic stalemate and unprecedented butchery. The conflagration pitted the Central Powers (Germany, Austria–Hungary and Turkey) against the Allies (France, Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan and later the United States of America in 1917) into one of the greatest watersheds of twentieth-century geopolitical history. It led to the fall of four imperial dynasties (Germany, Russia, Austria–Hungary and Turkey) and brought in its wake the Russian Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, destabilizing all Europe. It also sowed the seeds for a larger and more catastrophic conflict on the world stage.

With Britain’s entry into the First World War, all her colonies, including India, had no option but to be dragged into this conflict. Around 5 August 1914, the British War Council ratified the involvement of the British Indian Army and Indian soldiers into this conflict. The Indian Army had already been employed in several wars in China, Egypt, Sudan, Perak (in Malaysia) and Abyssinia (present-day Ethiopia). However, Indians were not employed in conflicts involving ‘white enemies’, such as the Boer Wars,14 largely due to a racial strategy. It was rather unthinkable that the ‘black Indian’ should be seen hacking a ‘white European’ of any nationality, as that would embolden him to do similar things with his colonial masters back home. The horrors of 1857 had simply not left the British Indian government it seemed. Yet, as the conflict increased with every passing day, the dire necessity for soldiers made Britain disregard this policy of racial hierarchy in the army.

By the winter of 1914, Indian troops were at the western front and fought at the first Battle of Ypres. They were deployed as reinforcements in the battlefields of Europe and fought in most theatres of the war, including Gallipoli and North and East Africa and Mesopotamia. An estimated total of 1,215,318 soldiers were sent abroad to all the war zones —Mesopotamia, Egypt, France, East Africa, Gallipoli, Salonica, Aden and the Persian Gulf. Nearly 1.5 million volunteered to fight. About 47,746 were classed as killed or missing, with about 65,000 wounded. More than 101,439 casualties of Indian soldiers were reported. In addition, £3.5 million was paid by India as ‘war gratuities’ of British officers and men of the normal garrisons of India. A further sum of £13.1 million was paid from Indian revenues for the war. In cash and kind an estimate of £146.2 million was India’s gigantic contribution to Britain in this effort— something that is valuated at £50 billion, or even higher, today!15

The princely states and the Indian political bourgeoisie lapped this up as an opportunity driven by different motives. For the Indian princes who were virtually under British thraldom, it was yet another opportunity to ingratiate themselves to their colonial masters. Apart from ‘The Imperial Service Troops’ organized by the princely states and put in the service of Viceroy Lord Hardinge, assistance in kind also came in large quantities as did generous grants of money from the maharajas of Mysore, Jodhpur, Gwalior and the Nizam of Hyderabad. Food, clothes, ambulances, horses, labourers and motorcars were donated. The outpouring of Indian support overwhelmed even the British. It was largely believed by many that the moment Britain got into trouble, the whole of India would burst into a blaze of rebellion, more so given the efforts of the Germans to stir and support the anti-British unrest in India.

However, an irksome communal issue got intertwined with the war efforts with the Ottoman Empire of Turkey joining its forces with Germany against the British by end October 1914. The sultans of the Ottoman Empire claimed the highest position in Islam, that of the caliphate—an Islamic kingdom under the caliph, or Khalifah, the politico-religious successor of Prophet Muhammad himself and a leader of the entire ummah, or global Muslim community. Caliphates such as the Rashidun, the Umayyad and the Abbasid had existed in medieval times. The Ottoman Empire claimed its stake as the fourth caliphate in 1517 and took control over the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Such an exalted religious and political figure was naturally held in great reverence by Muslims of South Asia too. The British feared that the large contingent of Muslim soldiers in the army would not support them in this war against their Khalifah. The fear of desertion by the troops, or even jihad, if forced to fight against their Turkish ‘brethren’ constantly plagued the British. To assuage these fears, several Muslim leaders and princes had to publicly seek complete loyalty from the Muslim subjects and soldiers towards the British war efforts.

Along with the princely states, the nationalists of the time too pledged their support for Britain’s war efforts. These were driven by their calculation that unstinted support during a time of crisis might motivate Britain to speedily grant more concessions to their demands after the War. Annie Besant and Tilak, who dominated the national political scene, threw their might behind this popular sentiment. The Indian National Congress openly supported Britain during this crucial period. When war broke out, Gandhi was in England, where he began organizing a medical corps similar to the force he had led in aid of the British during the Boer War. In a circular dated 22 September 1914, he called for recruitment to his Field Ambulance Training Corps.16 Several Indians served in hospitals in Southampton and Brighton, and Gandhi himself, aided by his wife Kasturba, took nursing classes. But he soon fell ill with pleurisy and returned to India by January 1915.

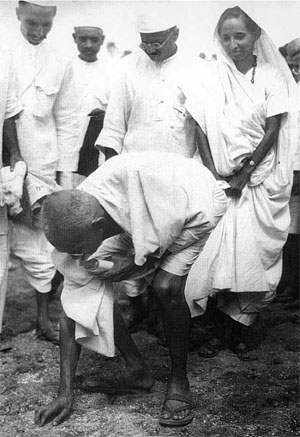

Gandhi offered unconditional support to the British efforts right from the beginning. He strongly believed that it was not a good time to embarrass Britain or take advantage of her troubled situation to further the Indian liberation cause. ‘England’s need,’ he had said, ‘should not be turned into our opportunity and that it was more becoming and far-sighted not to press our demands while the war lasted.’17 On his return to India, he helped expand the recruitment bases for the British Indian Army from places like Gujarat that did not have the so-called traditional martial races. The apostle of non-violence was marching from village to village in 1918 in the most interior of villages of his home province, addressing mass gatherings in recruitment centres, enlisting people for the War....

But the reforms suggested by Montagu gathered steam. After all the deliberations, he drew up a report with Bhupendra Nath Bose, Lord Richard Hely-Hutchinson, sixth Earl of Donoughmore, William Duke and Charles Roberts. 61 The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms, as they were called, eventually culminated in the Government of India Act, 1919.

A bicameral legislature was set up with two houses—the Legislative Assembly and the Council of State. The Legislative Assembly was to have 145 members of whom 103 were elected and the rest were nominated. Of these 103, fifty-one were elected from general constituencies, thirty-two by communal/separate constituencies (thirty by Muslims, two by Sikhs), and twenty by special constituencies such as landholders, Anglo-Indians, etc. The Council of State had sixty members—thirty-three elected and twenty-seven nominated by the Governor General. The life of the Central Legislative Assembly was for three years and the Council of State for five years. The franchise was extended, central and provincial legislative councils were given more authority, but the viceroy still remained accountable only to London.62

At the provincial level, significant changes were made whereby a Provincial Legislative Council was created with a majority of elected members. All the major provinces such as Bengal, Madras, Bombay, United Provinces, Punjab, Bihar, Central Provinces and Assam were to be ruled by a governor. Under a system called dyarchy, the rights of central and provincial governments were strictly demarcated. The central or reserved list had rights over defence, foreign affairs, telegraphs, railways, postal, foreign trade and so on, while the provincial or transferred list dealt with issues of health, education, sanitation, irrigation, jail, police, justice, public works, excise, religious and charitable endowments, etc.63

The reaction to the Government of India Act from Indians was on expected lines. The moderates, though not fully satisfied, advocated ungrudging cooperation within the contours of the new reforms to help them succeed. A strong section was inclined to reject it altogether. Tilak, who by then dominated the Congress after the death of Gokhale in 1915, stuck to a middle path of ‘Responsive Cooperation’ that would depend on how the government acted on each of its promises.

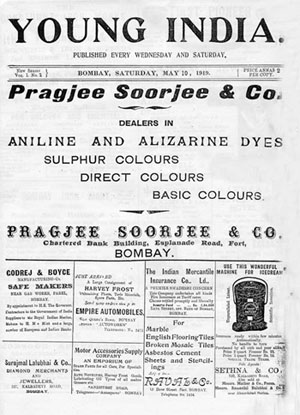

In its thirty-fourth session held at Amritsar in end December 1919, the INC, under President Chittaranjan Das, moved a resolution that stated that the ‘Reform Act is inadequate, unsatisfactory, and disappointing’. It urged parliament to take early steps towards establishing a fully responsible government in accordance with the principle of self-government. Das favoured a rejection of the reforms. It was in this session that Gandhi managed to make a significant impact on the Congress. Gandhi’s stand was explained in his article for Young India: ‘The Reforms Act . . . is an earnest of the intention of the British people to do justice to India and it ought to remove suspicion on that score . . . Our duty therefore is not to subject the Reforms to carping criticism but to settle down quietly to work so as to make them a success.’64

The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms thus divided many Congress leaders and amid apprehensions of yet another ideological split, Chittaranjan Das arrived at a compromise. The resolution was reworded to state that: ‘The Congress trusts, that so far as may be possible they will work the reforms so as to secure an early establishment of full Responsible Government.’65 It also stated that the Congress was ‘not opposed to obstruction, plain, downright obstruction, when that helps to obtain our political goal’. The stand was akin to what Tilak advocated—one of ‘Responsive Cooperation’. Gandhi too added: ‘. . . that does not mean that we may sit with folded hands and may still expect to get what we want. Under the British Constitution no one gets anything without a hard fight for it . . . We must lay to heart the advice of the President of the Congress that we shall gain nothing without agitation.’66 ...

The Government of India continued with its policy of reforms along with repression. A committee was appointed in December 1917 to investigate the nature and extent of the revolutionary movement in India. It was also mandated to examine the difficulties that arose in the handling of such conspiracy cases. Justice S.A.T. Rowlatt, of the King’s Bench Division of His Majesty’s High Court of Justice, served as the chairman of this committee. The committee had full access to information in the government’s possession. This was termed the Rowlatt Sedition Committee.

The committee made an exhaustive report on the history and evolution of revolutionary activities in different parts of India and outside. Vinayak’s role in this was also detailed. It recommended a new legislation to replace the Defence of India Act, 1915. It sought to bring about strict laws to curtail the liberty of people in a drastic manner. Two bills were prepared on the basis of these recommendations—the Indian Criminal Law (Amendment) Bill No. I of 1919 and the Criminal Law (Emergency Powers) Bill No. II of 1919. The latter was passed into law, and named the Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act, 1919. It called for a speedy trial of offences by a special court consisting of three high court judges. The right to appeal was also stripped off the accused. Provincial governments were empowered to search at will anyone’s house that came under their radar of suspicion and round up the individual indefinitely without even an arrest warrant. The act intended to quell the publication, distribution and sale of prohibited works. 74

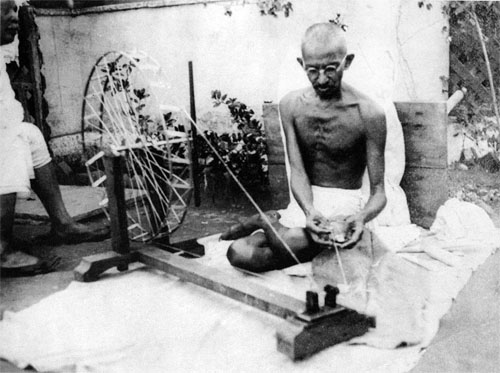

These sweeping emergency powers, through the Rowlatt Act, bestowed on the government were strenuously opposed by Indians of all shades of political thought. But the bill was passed and entered the statute books on 21 March 1919. This brought unprecedented limelight on Gandhi who had till then remained in the background with movements in Champaran advocating the plight of indigo cultivators and the mill workers of Ahmedabad. A small group was formed, consisting of Gandhi, Vallabhbhai Patel and Sarojini Naidu, to offer satyagraha, or peaceful resistance, to these new acts. This came to be known also as the Rowlatt Satyagraha. On 24 February 1919, they pledged that ‘in the event of these Bills becoming law and until they are withdrawn, we shall refuse civilly to obey these laws and such other laws as a Committee to be hereafter appointed, may think fit . . . we will follow truth and refrain from violence to life, person or property’.75 A Satyagraha Sabha with Gandhi as president called for a strike on 6 April 1919. Gandhi’s leadership was put to intense test during this first major pan-India campaign that he was embarking upon.

Disturbances had broken out all over the country, with riots and arson causing loss of lives and property. Disturbed by this, Gandhi called off the satyagraha on 18 April even before it could gather full steam. But large=scale ferment continued in the Punjab. This forced the government to bar Gandhi from entering the province. The government also imposed martial law with Brigadier General Reginald Dyer in command by 11 April 1919, though it was not formally declared before 15 April. Unaware of the law being imposed, approximately 6,000–10,000 unarmed people had gathered on 13 April 1919 for a public meeting at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar. Soon after the meeting began, Dyer reached the spot without any warning to the attendees. He passed, with his infantry, through a narrow lane into Jallianwalla Bagh and at once deployed them to the right and left of the entrance in the Bagh’s square. The armoured cars remained outside the square and never came into action as the lane was too narrow for them to enter. The gates of the Bagh were shut and his troops stationed themselves on a raised ground. Without any warning, Dyer ordered indiscriminate firing on the mass of humanity that had gathered there. More than 1500 rounds were shot. Men, women, children and old people were caught in this firing and martyred. As per government records, nearly 379 were killed and more than 1200 wounded (the actual numbers were much more).

Dyer was anything but remorseful of this savagery and in fact boasted of his achievements and what he termed as a merciful act. He admitted that he could have dispersed them without firing but that would have been derogatory to his dignity as a defender of law and order. It was to maintain his self-respect, he claimed, that he decided to fire, leaving behind a trail of corpses. This brutality sent shock waves across India, more so at a time when the government was discussing administrative reforms and limited self-government. Ironically, Dyer was feted as a hero by the British. A fund created in his support by the Morning Post in London and another in Mussoorie in India collected a purse of £20,000.76

Viceroy Lord Chelmsford’s response to this genocide was indicative of the government’s attitude:I have heard that Dyer administered Martial Law in Amritsar very reasonably and in no sense tyrannously. In these circumstances you will understand why it is that both the Commander-in-Chief and I feel very strongly that an error of judgment, transitory in its consequences, should not bring down upon him a penalty which would be out of all proportion to the offence and which must be balanced against the very notable services which he rendered at an extremely critical time.77

The massacre shook the nation and for the first time Gandhi’s trust in the British was eroded. He demanded a thorough inquiry into the carnage. The Hunter Commission was set up to investigate the matter. However, Gandhi did not wish to derail the process of reforms and cooperation with the government. On 21 July 1919, he issued a statement in which he said that on account of indications of goodwill on the part of the government and advice from many friends, he would not resume non-cooperation, as it was not his purpose to embarrass the government. Instead, he urged the satyagrahis to work for constructive programmes such as the use of indigenous goods and Hindu–Muslim unity.78...

From his clinic in Girgaum, Bombay, Narayanrao decided to do the unthinkable. He picked up his pen and wrote a letter to a man who was ideologically opposed to his brother, but nonetheless was fast emerging as a major political voice in the country—Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. In the first of six letters, dated 18 January 1920, he wrote to Gandhi, Narayanrao sought the latter’s help and advice in securing the release of his elder brothers in the wake of the royal proclamation.Yesterday [17 January] I was informed by the Government of India that the Savarkar brothers were not included in those that are to be released . . . It is now clear that the Indian Government have decided not to release them. Please let me hear from you as to how to proceed in such circumstances. They have already undergone a rigorous sentence for more than ten years in the Andamans and their health is utterly shattered. Their weight has come down from 118 lbs. to 95–100. Though they are given a hospital diet at present, their health does not show any sign of improvement. At least a change to some Indian jail of better climate is the most essential for them. I have received a letter from one of them very recently (one month back) in which all this is mentioned. I hope that you will let me know what you mean to do in this matter.1

One week later, on 25 January 1920, Gandhi replied and quite expectedly told him that he could do very little by way of assistance.Dear Dr Savarkar, I have your letter. It is difficult to advise you. I suggest, however, your framing a brief petition setting forth facts of the case bringing out in clear relief the fact that the offence committed by your brother was purely political. I suggest this in order that it would be possible to concentrate public attention on the case. Meanwhile as I have said to you in an earlier letter I am moving in the matter in my own way.2

However, several months later, on 26 May 1920, Gandhi wrote an article in Young India titled ‘Savarkar Brothers’ and built a case for their release by the government.Thanks to the action of the Government of India and the Provincial Governments, many of those who were undergoing imprisonment at the time have received the benefit of the Royal clemency. But there are some notable ‘political offenders’ who have not yet been discharged. Among these I count Savarkar brothers. They are political offenders in the same sense as men, for instance, who have been discharged in the Punjab. And yet these two brothers have not received their liberty although five months have gone by after the publication of the Proclamation . . . It is clear . . . that all the offences charged against Mr Savarkar (senior) were of a public nature. He had done no violence. He was married, had two daughters who died, and his wife died about eighteen months ago . . . the other brother . . . is better known for his career in London . . . He was charged also in 1911 with abetment of murder. No act of violence was proved against him either.

Both these brothers have declared their political opinions and both have stated that they do not entertain any revolutionary ideas and that if they were set free they would like to work under the Reforms Act, for they consider that the reforms enable one to work thereunder so as to achieve political responsibility for India. They both state unequivocally that they do not desire independence from the British connection. On the contrary, they feel that India’s destiny can be best worked out in association with the British. Nobody has questioned their honour or their honesty, and in my opinion the published expression of their views ought to be taken at its face value . . .

Now the only reason for still further restricting the liberty of the two brothers can only be ‘danger to public safety,’ for, the viceroy has been charged by His Majesty to exercise Royal clemency to political offenders in the fullest manner which in his judgment is compatible with public safety. I hold therefore that unless there is absolute proof that the discharge of the two brothers who have already suffered long enough terms of imprisonment, who have lost considerably in body-weight and who have declared their political opinions, can be proved to be a danger to the State, the Viceroy is bound to give them their liberty. The obligation to discharge them, on the one condition of public safety being fulfilled, is in Viceroy’s political capacity just as imperative as it was for the Judges in their judicial capacity to impose on the two brothers the minimum penalty allowed by law. If they are to be kept under detention any longer, a full statement justifying it is due to the public . . .

This case is no better and no worse than that of Bhai Parmanand who, thanks to the Punjab Government, has after a long term of imprisonment received his discharge. Nor need his case be distinguished from that of Savarkar brothers in the sense that Bhai Parmanand pleaded absolute innocence . . . The public are entitled to know the precise grounds upon which the liberty of the brothers is being restrained in spite of the Royal Proclamation which to them is as good as a royal charter having the force of law....3

Far removed from the hectic parleys that were going on regarding his release, on 4 November 1920, Vinayak was promoted to the position of a foreman in charge of manufacturing oil. After a brief probation he was confirmed as a permanent foreman. He drew a handsome monthly salary of Re 1 for this work! The coconut gardens and the oil from them were the main source of revenue in the Andamans. Cellular Jail had three big reservoirs full of oil ground out of the mills by prisoners. Big casks were filled with oil and exported to Calcutta and Rangoon and in return several thousand rupees accrued to the government treasury.

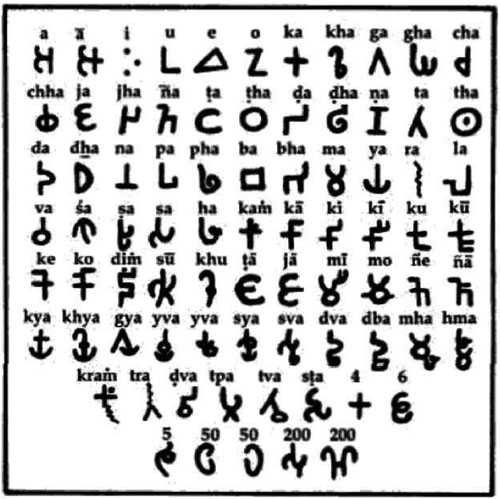

In addition to the shuddhi, sangathan and literacy movements that he spearheaded in jail, another issue close to Vinayak’s heart was the propagation of Hindi. Right from 1906, while in England, he had begun work to make Hindi the national language of India. In a linguistically diverse country such as India the exalting of a single language was bound to create tensions and differences. But it was also an important tool for national unity, Vinayak argued. Making Hindi the national language of the independent republic of India and Devanagari the script in which it was to be written, was something that all members of Abhinav Bharat pledged. It was long after 1906, and an initial rejection of the idea, that several other national leaders like Tilak and Gandhi espoused the cause of Hindi as the national language. Their acceptance followed agitations on the matter by the Nagar Pracharini Sabha of Benares and the Arya Samaj. In fact, the propaganda in favour of Hindi as India’s national language and encouraging patriotic writings in it was pioneered by Swami Dayanand Saraswati....

(Cont'd below)