Persons of Indian Studies

by Prof. Dr. Klaus Karttunen

Fuhrer was later found to have fraudulently laid claim to the discovery of about twenty relic-caskets at sites close to Lumbini, which allegedly bore Asokan, and even pre-Asokan inscriptions. One of these items supposedly contained a tooth-relic of the Buddha, which Fuhrer illicitly exchanged for gifts with a Burmese monk, U Ma (the correspondence between these two makes for lamentable reading, with Fuhrer exploiting U Ma’s gullibility quite unmercifully). Following an official enquiry into the matter, this tooth-relic was found to be ‘apparently that of a horse’: Fuhrer had explained its large size to an indignant U Ma by pointing out that according to ‘your sacred writings’ the Buddha was nearly thirty feet in height!

According to Fuhrer, this ‘Buddhadanta’ had been found by a villager inside a ruined brick stupa near Tilaurakot, and was ‘enshrined in a bronze casket, bearing the following inscription in Maurya characters: “This sacred tooth-relic of Lord Buddha (is) the gift of Upagupta” (the mentor of Asoka). Having obligingly parted with the relic, the villager had refused to part with the inscribed casket itself ‘which is still in his possession’. Fuhrer reported finding this bogus Asokan inscription during the selfsame visit which saw the discovery of the Asokan inscription at Lumbini. Moreover, according to Fuhrer, the Lumbini inscription included words which were supposedly spoken by Upagupta whilst showing Asoka the Buddha’s birth-spot: ‘It would almost appear as if Asoka had engraved on this pillar the identical words which Upagupta uttered at this place’, he tells us, all wide-eyed. However, what with a bogus Upagupta quote on the casket, an Upagupta quote on the pillar, and Fuhrer’s keen taste for forging Brahmi inscriptions, we may here recall that he had fraudulently incised Brahmi inscriptions on to stone four years earlier (see ‘Fuhrer's Early Years’). And indeed, this pillar inscription ‘appeared almost as if freshly cut’ when Rhys Davids examined it in 1900, a view echoed by Professors N. Dutt and K. D. Bajpai, who noted that ‘it appears as if the inscription has been very recently incised’ when they examined it fifty years later. W. C. Peppe observed that ‘the rain falling on this pillar must have trickled over these letters and it is marvellous how well they are preserved; they stand out boldly as if they had been cut today and show no signs of the effects of climate; not a portion of the inscription is even stained’.

Inscriptions on other Asokan pillars located at sites associated with the Buddha’s life and ministry -- Sarnath and Kosambi, for example -- contain no references to their Buddhist associations, as this pillar so conspicuously -- and twice -- does; and no other inscription makes reference to any erection of a particular pillar by Asoka (as this one does) either. And with the exceptions of Sarnath and Sanchi, where only broken bases of pillars have been found, the surfaces of all other inscribed Asokan pillars are almost covered with inscriptions, whereas this pillar, and the nearby Nigliva pillar, display only single meagre inscriptions of 4 -5 lines each, and as J. F. Fleet has pointed out, they are not really edicts at all....

The Piprahwa Discoveries

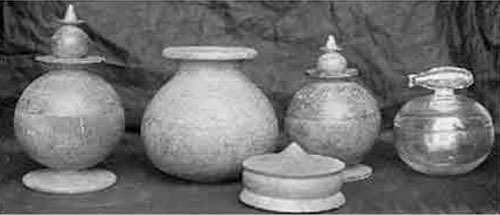

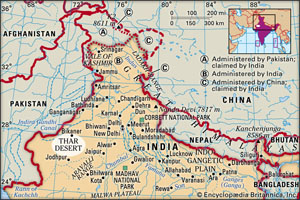

In January 1898, W. C. Peppe, manager of the Birdpur Estate in north-eastern Basti District, U. P., announced the discovery of soapstone caskets and jewellery inside a stupa near Piprahwa (see map) a small village on this estate. An inscription on one of these caskets appeared to indicate that bone relics, supposedly found with these items, were those of the Buddha. Since this inscription also referred to the Buddha’s Sakyan kinsmen, these relics were thus generally considered to be those which were accorded to the Sakyas of Kapilavastu, following the Buddha’s cremation. The following year, these bone relics were ceremonially presented by the (British) Government of India to the King of Siam, who in turn accorded portions to the Sanghas of Burma and Ceylon. Concerning this discovery, however, the following points should be noted:

• Peppe had been in contact with Fuhrer just before announcing the Piprahwa discovery (Fuhrer was then excavating nearby, at the Nepalese site of Sagarwa: see map). Immediately following Peppe's announcement, it was discovered that Fuhrer had been conducting a steady trade in bogus relics of the Buddha with a Burmese monk, U Ma. Among these items -– and a year before the alleged Piprahwa finds -- Fuhrer had sent U Ma a soapstone relic-casket containing fraudulent Buddha-relics of the Sakyas of Kapilavastu, together with a bogus Asokan inscription, these deceptions thus duplicating, at an earlier date, Peppe’s supposedly unique finds. Fuhrer was also found to have falsely laid claim to the discovery of seventeen inscribed, pre-Asokan Sakyan caskets at Sagarwa, his report even listing the names of seventeen ‘Sakya heroes’ which were allegedly inscribed upon these caskets. The inscribed Piprahwa casket was also considered to be both Sakyan and pre-Asokan at this time -- though its characters have since been shown to be typically Asokan -- and no other Sakyan caskets have been discovered either before or since this date.

• The bone relics themselves, purportedly 2500 years old, ‘might have been picked up a few days ago’ according to Peppe, whilst a molar tooth found among these items (and retained by Peppe) has recently been found to be that of a pig. The eminent archaeologist, Theodor Bloch, declared of the Piprahwa stupa that ‘one may be permitted to maintain some doubts in regard to the theory that the latter monument contained the relic share of the Buddha received by the Sakyas. The bones found at that place, which have been presented to the King of Siam, and which I saw in Calcutta, according to my opinion were not human bones at all’. Bloch was then Superintendent both of the ASI [Archaeological Survey of India] Bengal Circle and the Archaeological Section of the Indian Museum, and would presumably have drawn not only upon his own expertise in making this assertion, but also that of the zoologists in the Indian Museum itself. This museum -– formerly the Imperial Museum -- was then considered to be the greatest in Asia.

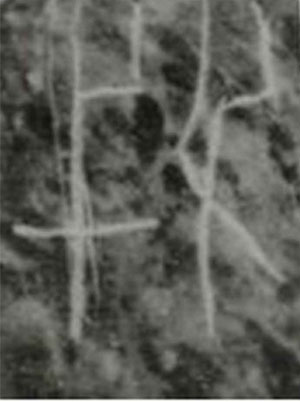

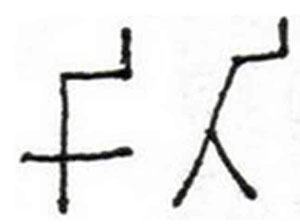

• The caskets appear to be identical to caskets found in Cunningham’s book ‘Bhilsa Topes’ (see Figs. 7-12) a source also used by Fuhrer for his Nigliva deceptions. A photograph of the ‘rear’ of the inscribed Piprahwa casket, taken in situ at Piprahwa in 1898 (and never published thereafter) discloses that a large sherd was missing from the base of the vessel at this time (see Fig. 8). Having closely examined this casket in 1994, I noted that a piece had since been inserted into this broken base, and that this had been ‘nibbled’ in a clumsy attempt to get this piece to fit. The photograph also reveals a curious feature on the upper aspect of the casket; this, I discovered, was a piece of sealing-wax (since transferred to the inside) which had been applied to prevent a large crack from running further. From all this, it is evident that this casket had been badly damaged from the start, a fact not mentioned in any published report. But is it likely, one is prompted to ask, that this damaged casket, supposedly containing the Buddha’s relics, would have been deposited inside the stupa anyway? Or is this the broken casket, ‘similar in shape to those found below’, which was reportedly found near the summit of the stupa, and which had vanished without trace thereafter? This casket -– also damaged -- was the first of the alleged Piprahwa finds; so did Peppe take it to Fuhrer, and did Fuhrer then forge the inscription on it? Is the Piprahwa inscription simply another Fuhrer forgery? As Assistant Editor on the Epigraphia Indica, Fuhrer would certainly have had the necessary expertise to do this, quite apart from his close association with the great epigraphist, Georg Buhler (who may have unwittingly provided Fuhrer with the necessary details, according to the existing accounts).

• On his return to the U.K., Peppe was contacted by the London Buddhist Society, and agreed to answer readers’ questions on his finds. Shortly afterwards however, the Society was notified that Peppe had suddenly been taken seriously ill, and was therefore unable to answer any questions as proposed. The Society declared the matter to be ‘in abeyance’ in consequence; but Peppe died six years later, leaving all such questions still unanswered.

• The declassified ‘Secret’ political files of the period reveal the disquiet felt by the Government of India over French and Russian influence at the Siamese royal court at this time. Hence, no doubt, this bequest!

In 1972 an Indian archaeologist, K. M. Srivastava, made the startling claim to have discovered yet further relics of the Buddha in a ‘primary mud stupa’ below the Peppe one. According to him, the ‘indiscriminate destruction’ caused by Peppe meant that the 1898 bone relics could not be safely determined to be those of the Buddha, and the inscribed casket somehow ‘pointed’ to those relics allegedly found (by him) lower down, which were thus the real relics of the Buddha as mentioned by the casket’s inscription. Since this bizarre proposal thus rests upon the notion that the 1898 inscription is genuine –- hardly likely, as we have seen -– then this claim becomes equally improbable in consequence. I also note that Srivastava makes no mention, in any of his publications on his alleged finds, of the earlier bequest of the Peppe relics to Siam. Naturally, one wonders why.

-- Lumbini On Trial: The Untold Story. Lumbini Is An Astonishing Fraud Begun in 1896, by T. A. Phelps

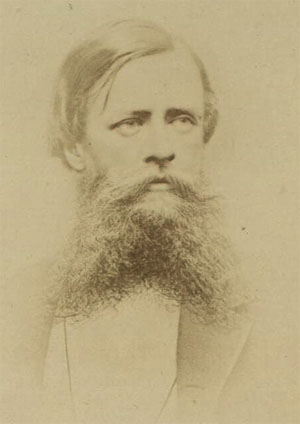

PEPPE, William Claxton. Birdpur, Gorakhpur dt. 1.2.1852 — Welshpool, Montgomeryshire 1937. British Engineer in India, interested in Archaeology. Son of William P. [Claxton]. Educated in Aberdeen, then studied there engineering. He inherited the indigo estate of Birdwood in Piprahwa (in U.P. close to Nepalese border), where he conducted excavations and in January 1898 found the famous stūpa and the vase with the Peppe inscription.

Retired 1904 and returned to the U.K. In 1911 living in Montgomeryshire, Wales.

Married 1884 Sophia Rosalie Hill (d. 1887), then 1890 Caroline Ella Hill, three sons and one daughter.

Publications: “The Piprahwa Stupa, containing relics of Buddha”, JRAS 1898, 573-588.

Sources: http://honeymooney.com/genealogy/getper ... tkaerheron, http://www.myheritage and other stray notes in Internet

**********************

William Peppe

by The RAI Organization, UK

Accessed: 7/3/21

Peppe, William

Died: 1890

Residence: Grantee, Birdpore Grant, Goruckpore, Bustee, N.W. Province, Birdpore Goruckpore, via Bella Harriya, India [1881]

Society Membership

membership: ASL, AI ordinary fellow

left: 1888.06 last listed

elected_AI: 1869

elected_ASL: 1869.11.02

Notes

Office Notes

House Notes

proposed 1869.10.12

Peppe [last e acute] in List 1879 [so have changed from Pepper which I had originally]

death noted in report of Council for 1890 (may have occurred in 1889)

Notes From Elsewhere

William George or William Claxton??

In 1842, my great-grandfather, William [Claxton] Peppé, and his brother, George (both civil engineers from Aberdeen University), received a commission from a London firm to set up and run a sugar mill. After arriving they duly built the sugar mill and started production. Unfortunately George’s health broke down shortly after arriving and had to return home.

With George gone, William had expected to be made manager, but this failed to happen. It was then that William heard of a local widow who needed a manager to run an estate called Birdpur in Northern India on the border with Nepal. He applied and got the job.

The widow’s estate was on land acquired from the kingdom of Oude by the Honourable East Indian Company who offered grants of land called "Jungle Grants" with a 50 year lease. Part of the land deal for anyone obtaining the grant was that after 50 years the land would be theirs to own. Very few people succeeded.

This land lay between the foothills of the Himalayas and the Ganges plain.

And while it was fertile land with many rivers and was known as the "Gorakpur Tarai" it was covered with jungle and swamps, and was notorious for malaria. Few people could work the land other than the "Tharus" who were native to the jungle and hunter/gatherers. However, my great-grandfather, despite the difficulties of the terrain and threat of malaria was able to put a certain amount of land under cultivation each year.

William set about clearing the land and building reservoirs, dams, and canals to enable him to cultivate it -- which he did successfully. Indeed, he was so successful at experimenting with different strains of rice that he eventually developed a Patna Rice, now known as American Long Grain Rice.

Furthermore, at the time of the Indian mutiny William fought with a band of his own loyal tenants against the mutineers.

For these services to the British government they gave him another estate and not content with this, he then went about buying two other estates adjoining Birdpur. Eventually the estate he managed was nearly fifty square miles.

William subsequently had a son -- William Claxton -– my grandfather, who became an assistant on the estate and when his father died he took over its’ management. He too had a son -– my father, Humphrey Peppé.

After the 1st World War, in which my father fought, he studied civil engineering at Cambridge and then went out to India to become my grandfather’s assistant. Eventually he took over the running of the estate when my grandfather retired.

However, on Indian independence, the estate was nationalised and my father spent another thirteen years in India trying to broker a deal with the government so as not to lose everything he, his father, and my great-grandfather had worked so hard to create.

The story brought forward by Bones of the Buddha is a fascinating one: one of the British Raj in India, when the amateur archaeologist W.C. Peppe plowed a trench through an enormous stupa and found the 4th century BC burial remains.

The Bones of the Buddha is an historical entry in the PBS series Secrets of the Dead, published in 2013.

William Claxton Peppè wasn’t interested in the objects’ religious value. His grandson says: “He was a strict but well-loved man, a Victorian Christian who had married a vicar’s daughter.

Name: William C Peppe Birth: year Death: dd mm 1937 - city, Montgomeryshire, Wales

In January 1898, Mr W. C. Peppe, manager of the Birdpur Estate in north-eastern Basti District, U. P., announced the discovery of soapstone relic-caskets and jewellery inside a stupa near Piprahwa, a small village on this estate. An inscription on one of these caskets appeared to indicate that bone relics, supposedly found with these items, were those of the Buddha. Since this inscription also referred to the Buddha’s Sakyan kinsmen, these relics were thus generally considered to be those which were accorded to the Sakyas of Kapilavastu, following the Buddha’s cremation. The following year (1899) these bone relics were presented by the (British) Government of India to the King of Siam, who in turn accorded portions to the Sanghas of Burma and Ceylon.

William George Peppe, brutal murderer of 1857 in the eye of Hindustan (INDIA).

How William George Peppe became Hero For East India Company?

It was year 1857, The British were amazed and stunned. They could understand it well that the sepoy "Mutiny" has developed into a People's War and they realized it fully that the people's uprising is like a flood which sweeps away everything that comes in its way and spares nothing.

During this same period people of Mahua Dabar had killed Six British Army Officer in bits and pieces this was in revenge that British army had given to their fathers and to their village. In the early 19th century, the East India Company, eager to promote British textiles, had cut off the hands of hundreds of weavers in Bengal. Twenty weavers’ families from Murshidabad and Nadia had then fled to Awadh, whose nawab resettled them in Mahua Dabar and allowed them to carry on with their livelihood. Many of the first-generation weavers had already lost their hands, but they taught the craft to their sons and the small town of 5,000 people soon became a bustling handloom centre. It was around March-April 1857 when Zaffar Ali, a young man whose grandfather had migrated from Bengal, spotted a boat coming down the Manorama (a tributary of the Ghagra) on whose banks the town was located. The historians’ report names the six soldiers beheaded: Lt T.E. Lindsay, Lt W.H. Thomas, Lt G.L. Caulty, Sgt Edwards and privates A.F. English and T.J. Richie.

It was in consequence of this understanding that the Gorakhpur Judge W. Wynard and Collector W. Peterson appointed the Zamindar of Birdepur Willam Peppe as Deputy Magistrate of Basti and gave him half the troops of the 12th Irregular Horse Cavalry for his backing. Peppe was ordered to crush the people's uprising immediately by whatever means it may be possible.

So, on 20 June 1857, Peppe deployed the 12th Irregular Horse cavalry and surrounded Mahua Dabar from all sides and burned the township murdered thousands of people and burned them to ashes. Razed the entire town of Mahua Dabar. After this event he also mentioned on the colonial revenue records, that the area was marked as gair chiragi (non-revenue land). Soon this message reached like fire in every home and town of Hindustan that if any one revolt against British Empire he or they will be crushed to the ground, and very soon British Army gained its power again in India for this great work Willam Peppe was rewarded by East India Company he was granted land is in Basti district, round Birdpur. He was first manager and then owner of a large European estate there, which is still held by his successors, his sons Messrs. W. C. and G. T. Peppe and Mrs. Larpent, his daughter. Annie Jane Peppe married Lieut. Col. L. H. P. [Lionel Henry Planta de] Larpent, H. C. S. (References : Gazetteer; Foster B., M. N page# 822).

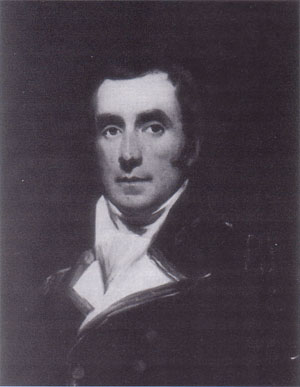

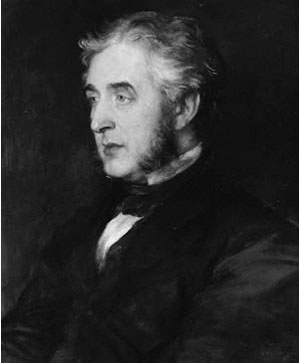

Francis Seymour Larpent; Charlotte Rosamund Larpent (née Arnold)

by Unknown artist

oil on canvas, circa 1830

29 1/2 in. x 24 1/2 in. (749 mm x 622 mm)

Sitters: Charlotte Rosamund Larpent (née Arnold) (died 1879), Second wife of Francis Seymour Larpent. Sitter in 1 portrait. Identify

Francis Seymour Larpent (1776-1845), Civil Servant. Sitter in 1 portrait. Identify

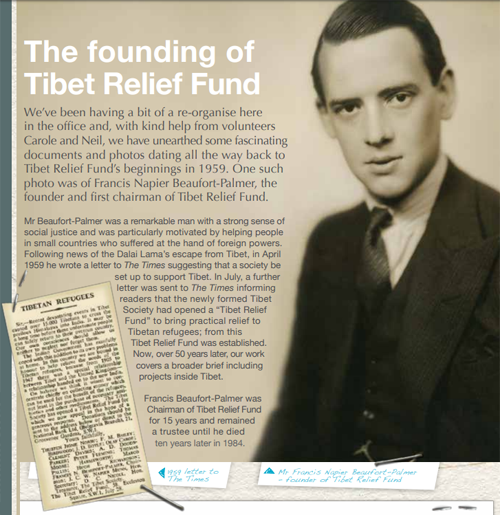

Given by Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer, 1951

-- Francis Seymour Larpent; Charlotte Rosamund Larpent (née Arnold), by National Portrait Gallery

PALMER, Francis Beaufort was born on July 7, 1845. Son of Reverend William Palmer (one of the originators of the Oxford Movement) and Sophia, daughter of Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort, Knight Commander of the Bath, Fellow of the Royal Society...

Spouse 1898, Georgiana Elizabeth, daughter of 8th Baron [Arthur John] de Hochepied Larpent [Father: John James de Hochepied Larpent [1783-1860]].

-- Francis Beaufort Palmer, by prabook.com

John James De Hochepied Larpent family tree

Children

2. Lionel Henry Planta [L.H.P.] De Hochepied Larpent 1834-1907

-- John James De Hochepied Larpent (1783-1860), by ancestra.ca

William George Peppe died in 1889 Inscription—In memory of William Peppe, son of George Peppe, died 1 9th July 1889. He rendered valuable services during the troubled times of the Indian Mutiny, which Government rewarded by a grant of land in this district. [Deputy Collector during the Mutmy. The Mutiny narrative only mentions him as burning a Muhammadan village (Mahua Dabar) whose inhabitants had murdered six officers, refugees from Fyzabad. He also rescued some other refugees. He was in fact the sole representative of Government, and had great difficulty in preserving his own life. His grant of land is in Basti district, round Birdpur. He was first manager and then owner of a large European estate there, which is still held by his successors, h:s sons Messrs. W. C. and G. T. Peppe and Mrs. Larpent, his daughter. Annie Jane Peppe married Lieut.*Col. L. H. P. Larpent, H. C. S.]

Willam G. Peppe death date is Abstract from book CHRISTIAN TOMBS AND MONUMENTS IN THE UNITED PROVINCES…BY E.A.B BLUNT I.C.S.

**********************

Piprahwa

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/3/21

Piprahava

village

Stupa at Piprahwa

Location in Uttar Pradesh, India

Coordinates: 27.443000°N 83.127800°ECoordinates: 27.443000°N 83.127800°E

Country: India

State: Uttar Pradesh

District: Siddharthnagar

Languages: Official Hindi

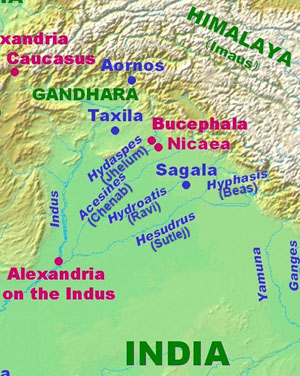

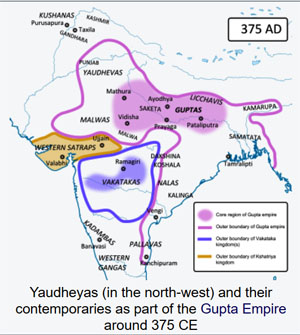

Piprahwa (Hindi: पिपरहवा) is a village near Birdpur in Siddharthnagar district of the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Kalanamak rice, a scented and spicy variety of rice is grown in this area.[1] It lies in the heart of the historical Buddha's homeland and is 12 miles from the world heritage site of Lumbini that is believed to be the place of Gautama Buddha's birth.

Piprahwa is best known for its archaeological site and excavations that suggest that it may have been the burial place of the portion of the Buddha's ashes that were given to his own Shakya clan. A large stupa and the ruins of several monasteries as well as a museum are located within the site. Ancient residential complexes and shrines were uncovered at the adjacent mound of Ganwaria.

Excavation by William Claxton Peppe

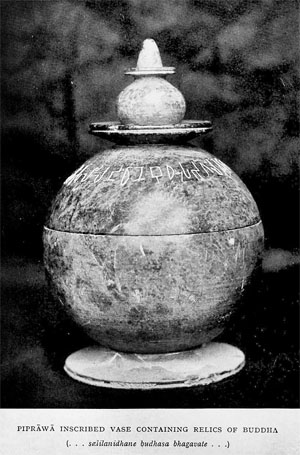

A buried stupa was discovered by William Claxton Peppe, a British colonial engineer and landowner of an estate at Piprahwa in January 1898. Following the severe famine that decimated Northern India in 1897, Peppe led a team in excavating a large earthen mound on his land. Having cleared away scrub and jungle, they set to work building a deep trench through the mound. After digging through 18 feet of solid brickwork, they came to a large stone coffer which contained five small vases containing bone fragments, ashes, and jewels.[2] On one of the vases was a Brahmi script which was translated by Georg Bühler, a leading European epigraphist of the time, to mean:

Piprahwa vase with relics of the Buddha. The inscription reads ...salilanidhane Budhasa Bhagavate... "Relics of the Buddha Lord"

Sukiti-bhatinaṃ sabhaginikanam sa-puta-dalanam iyaṃ salila-nidhane Budhasa bhagavate sakiyanam[3]

"This relic-shrine of divine Buddha (is the donation) of the Sakya-Sukiti brothers, associated with their sisters, sons, and wives,[4]

This inscription implied that the bone fragments were part of the remains of Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism.[5] Throughout the following decade or so, epigraphists debated the precise meaning of the inscription. Vincent Smith, William Hoey, Thomas Rhys Davids, and Emile Senart all translated the inscription to confirm that these were relics of the Buddha.[6][7]

In 1905, John Fleet, a former epigraphist of the Government of India, published a translation that agreed with this interpretation.[8] However, on assuming the role of Secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society from Thomas Rhys Davids, Fleet proposed a different reading:[9][10]

"This is a deposit of relics of the brethen of Sukiti, kinsmen of Buddha the Blessed One, with their sisters, their children and wives."[3]

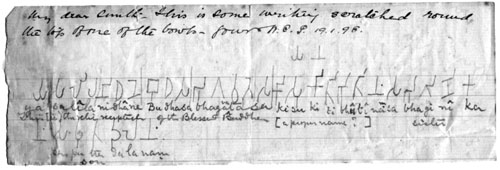

Handwritten note by discoverer W.C. Péppe to Vincent Arthur Smith about the inscription, 1898

This interpretation was firmly rejected by his contemporaries. Following such criticism Fleet wrote: "I now abandon my opinion".[11] Epigraphists of the time subscribed instead to the translation by Auguste Barth:

"This receptacle of relics of the blessed Buddha of the Śākyas (is the pious gift) of the brothers of Sukīrti, jointly with their sisters, with their sons and their wives."[12]

Over a hundred years later, in the 2013 documentary, Bones of the Buddha, epigraphist Harry Falk of Freie Universität Berlin confirmed the original interpretation that the depositors believed these to be the remains of the Buddha himself. Falk translated the inscription as "these are the relics of the Buddha, the Lord" and concluded that the reliquary found at Piprahwa did contain a portion of the ashes of the Buddha and that the inscription is authentic.[13]

In 1997, epigraphist and archaeologist Ahmad Hasan Dani noted the challenges that isolated finds present to paleographical study and to dating materials. He concluded that "the inscription may be confidently dated to the earlier half of the second century B.C." but noted that "the Piprahwa vase, found in the Basti District, U.P. (Uttar Pradesh), has an inscription scratched on the steatite stone in a careless manner. As the inscription refers to the remains of the Buddha, it was originally dated to the pre-Mauryan period, but it has been brought down to the third century B.C. on a comparison with Asokan Brahmi. The style of writing is very poor, and there is nothing in it that speaks of the hand of the Asokan scribes". [14] Dani's dating of the inscription puts it around 250 years after the generally agreed 480 BCE death of the historical Buddha which suggests that the stupa itself was built after the Buddha's lifetime. The time difference is most likely explained by the Emperor Ashoka’s sudden conversion to Buddhism. After slaughtering tens of thousands to secure his kingdom, Ashoka issued a decree to build stupas and redistribute the Buddha’s remains across his kingdom.[15]

Although there was some initial uncertainty about the translation, there is no record of any challenge to the authenticity of the find at the time.[16] However, in introducing the discovery to the members of the Royal Asiatic Society in April 1900, its secretary, Thomas Rhys Davids, stressed that 'the hypothesis of forgery in this case is simply unthinkable'.[17] Over a century later some have assumed that such doubts must have therefore existed most likely because government archaeologist, A.A. Führer, had been working in the region and had recently been exposed for plagiarism and forgery. The possibility of forgery was explored by writer and historian Charles Allen in his book The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer and in his documentary Bones of the Buddha. He researches the unfolding of events at Piprahwa based on the letters of W.C. Péppe, Vincent Smith, and A.A. Führer, and concludes that Führer was unable to interfere with the discovery of the inscription made by W.C. Péppe.[18] Harry Falk, professor of Indology at the Freie Universität in Berlin, stated in the documentary that Führer could not have forged the Piprahwa reliquary inscription. Richard Salomon of the University of Washington notes that 'Forgeries tend to be either blatant imitations of genuine inscriptions, or totally aberrant texts, and if the Piprahwa inscription were a forgery - which I am certain is not the case - it would belong to the latter category.' He goes on 'the Piprahwa inscription rings true in all regards'.[19]

The main stupa at Piprahwa, one of the earliest so far discovered in India, was built in three phases. In the 6th-5th century BCE, around the time of the death of the Buddha, it was raised by piling up natural earth from the surrounding area. This was in accordance with a request of the Buddha who had asked that he be buried under the earth "heaped up as rice is heaped in an alms bowl."[20] Phase II occurred during Ashoka’s rule (and was likely completed after his death around 235 BCE) as part of the Emperor’s mission to "distribute the relics of the exalted one."[21] Ashoka opened up the original stupas containing the relics of the Buddha, then restored the stupa and interred a portion of what he had taken. The remaining relics were distributed to other new stupas. At Piprahwa, the restoration consisted of filling thick clay over the structure and of building two tiers to reach a height of 4.55m. In phase III, during the Kushan period, the stupa was extensively enlarged and reached a height of 6.35 metres (20.8 ft). The largest structure after the stupa is the Eastern Monastery that measures 45.11m x 41.14m with a courtyard and more than thirty cells around it. The complex includes an additional Southern Monastery, Western Monastery, and Northern Monastery.[22]

Distribution of the relics

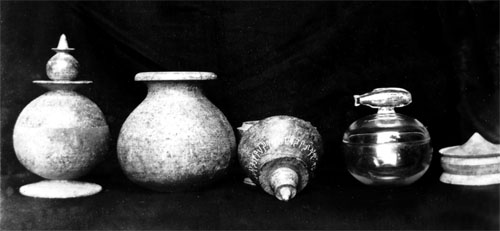

The five reliquaries discovered in Piprahwa.

Portion of the Piprahwa vase inscription. The inscription reads [x] salilanidhane Budhasa Bhagavate... "Relics of the Buddha Lord" (Brahmi script).

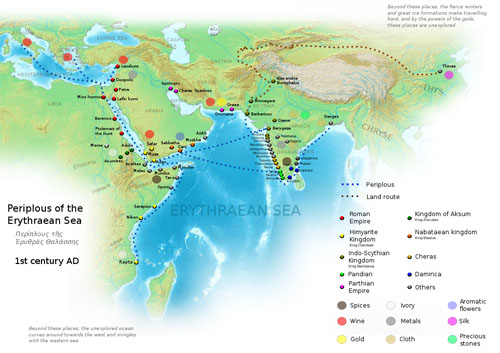

Prince Prisdang (aka Jinavaravansa), a former ambassador to Siam and cousin to the King Rama V, had been ordained as a Buddhist monk in Sri Lanka and arrived at Piprahwa shortly after the discovery. He soon learned that W.C. Peppe had placed his finds at the disposal of the government.[23][24] His eloquent arguments to persuade British government officials to donate the bone relics to the King of Siam to share with Buddhist communities in other countries received some support from lower level British officials and worked their way up to the Viceroy. It was an obvious solution that might appease Buddhists who were upset that the recently discovered Bodh Gaya, believed to be the place of the Buddha's enlightenment, had remained under Hindu control. It was also a gesture of goodwill to a country that was being courted by the French, Russian, and Dutch superpowers of the time.[25] In 1899, a ceremony was held and the bone relics were handed off to an emissary of King Rama V and traveled to Bangkok. Prisdang’s request to be involved was not realized.[26][27]

The bone relics were immediately distributed across several locations, including Golden Mount Temple in Bangkok, Thailand,[27] Shwedagon pagoda in Rangoon, Myanmar, Arakan pagoda in Mandalay, Myanmar, Dipaduttamarama Temple in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Waskaduwe Vihara in Kalutara, Sri Lanka,[28] and the Marichiwatta stupa in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka.[11]

The majority of the gold and jewelry relic offerings were donated by the Indian government to the Indian Museum, Kolkata. Today, a replica urn is on display.[29] Photographs of the items are on display at the Kapilavastu Museum at Piprahwa that is visited by Buddhist pilgrims.

W. C. Peppe was allowed to retain a number of duplicates which are exhibited in museums today.[30][31] He also gave some pieces to Prince Prisdang and Prisdang's Buddhist master, Sri Subuthi.[32][28] A box of 12 flowers was most likely given to Thomas Rhys Davids and the Royal Archaeological Society and discovered as part of a clean up at the Buddhist Society headquarters in London in 2004.[33]

On 16th December 2554 ( 2011), a portion of these Kapilvatthu Buddha Relics was offered to the Sangha of Ratanawan Monastery. In January, 2012, some of these relics were enshrined in the Buddha Homage Reliquary Hall, Ratanawan Monastery, Thailand.

Many senior monks participated in this auspicious ceremony including Ajahn Sumedho and Ajahn Viradhammo.

Excavations by the Archaeological Survey of India

Southern monastery

From 1971-1973, a team of the Archaeological Survey of India led by K.M. Srivastava resumed excavations at the Piprahwa stupa site. The team discovered a casket containing fragments of charred bone, at a location several feet deeper than the coffer that W.C. Peppe had previously excavated. As the relic containers were found in the deposits from the period of Northern Black Polished Ware, Srivastava dated the find to the fifth-fourth centuries BCE, which would be consistent with the period in which the Buddha is believed to have lived.[34] He also discovered 13 sealings which bore the same legend in Kushan script: 'Of the community of the monks of great Kapilavastu'. Today, the ancient sites of Piprahwa and Ganwaria host the Kapilavastu Museum, controlled by the Archaeological Survey of India.[22]

The bone fragments recovered by Srivastava's team are currently located at the National Museum, New Delhi.[35] In 1978, the Indian government allowed their share of the discovery to be exhibited in Sri Lanka and more than 10 million people paid homage. They were also exhibited in Mongolia in 1993, Singapore in 1994, South Korea in 1995, Thailand in 1996, and again in Sri Lanka in 2012.[36]

Location of ancient Kapilavastu

Srivastava's discovery of the terracotta sealings bearing the name Kapilavastu has led some scholars to believe that modern-day Piprahwa was the site of the ancient city of Kapilavastu, the capital of the Shakya kingdom, where Siddhartha Gautama spent the first 29 years of his life.[2][4][34][37] Others suggest that the original site of Kapilavastu is located 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) to the northwest, at Tilaurakot, in what is currently Kapilvastu District in Nepal.[38][39][40] This question is especially important to scholars of Buddhist history, as Kapilavastu was the capital of the Shakya kingdom. King Śuddhodana and Queen Māyādevī lived at Kapilavastu, as did their son Prince Siddhartha Gautama until he left the palace at 29 years of age.[41]

See also

• Bhattiprolu

• Bimaran casket

• Relics associated with Buddha

• Sanchi

Notes

References

1. Mishra 2005.

2. Peppe 1898, pp. 573–88.

3. Fleet 1907, pp. 129-130.

4. Bühler 1898, p. 388.

5. Peppe 1898, pp. 584–85.

6. Senart, Emile (1906). "Note sur l'inscription de Piprahwa". Journal Asiatique (Jan–Feb): 132–136.

7. Hoey, William (24 February 1898). "Piprahwa inscription". The Pioneer.

8. Fleet, John (October 1905). "Notes on three Buddhist Inscriptions". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 37 (4): 679–691. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00033748.

9. Fleet, John (1906). The inscription on the Priprawa vase. Journal Of The Royal Asiatic Society Of Great Britain And Ireland For-1906. pp. 149-.

10. "Inscribed Relic Casket from Piprahwa". Museums of India. National Portal and Digital Repository. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015.

11. Allen 2008, p. 212.

12. Barth, Auguste (October 1906). "The inscription on the Piprahwa vase". Journal des Savants. 36: 124.

13. Secrets of the Dead: Bones of the Buddha - Transcript, PBS, retrieved 16 April 2015

14. Dani 1997, Chapter 3.

15. Strong, John (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

16. Falk, Harry (2018). "The ashes of the Buddha". Bulletin of the Asia Institute: 45.

17. Rhys Davids, Thomas (1901). "Asoka and the Buddha relics". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. XIV: 398.

18. Allen 2008, p. [page needed].

19. Allen 2008, p. 261.

20. Allen 2008, p. 9.

21. Strong, John. Ashokavadana.

22. "The Stupa". Kapilavastu Museum. Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016.

23. Smith, Vincent (1898). "Government Correspondence" (741).

24. "The relics of Buddha". The Standard. Reuters. 19 December 1898. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

25. Rey, Himanshu Prabha (2014). The Return of the Buddha. Routledge. pp. 106–110.

26. Loos, Tamara (2016). Bones around my neck. Cornell University. p. 120.

27. Jinavaravansa & Jumsai 2003, p. 214.

28. Nanayakkara, Rasika (25 January 2013). "Exposition of Sacred relics". The Island.

29. Falk, Harry (2017). "The Ashes of the Buddha". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 27: 53.

30. Smith, Vincent (1898). "Government Correspondence". British Library (740 /III-2790-2).

31. "Next stop Nirvana". Rietberg Museum Newsletter. November 2018.

32. Allen 2008, pp. 209–210.

33. Mackenzie, Vicki (21 March 2004). "Buried with the Buddha". The Sunday Times.

34. Srivastava 1980, pp. 103–10.

35. Srivathsan 2012.

36. "Kapilavastu relics arrive in Sri Lanka". Daily Mirror. 19 August 2012.

37. Srivastava 1979, pp. 61-74.

38. Allen 2008, p. 262.

39. Tuladhar 2002, pp. 1-7.

40. Sharda 2015.

41. Trainor, K (2010). "Kapilavastu". In Keown, D; Prebish, CS (eds.). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Milton Park, UK: Routledge. pp. 436–7. ISBN 978-0-415-55624-8.

Sources

• Allen, Charles (2008). The Buddha and Dr Führer: an archaeological scandal (1st ed.). London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905791-93-4.

• Allen, Charles (2012), "What happened at Piprahwa: A chronology of events relating to the excavation in January 1898 of the Piprahwa Stupa in Basti District, North-Western Provinces and Oude (Uttar Pradesh), India, and the associated 'Piprahwa Inscription', based on newly available correspondence", Zeitschrift für Indologie und Südasienstudien, 29: 1–19, OCLC 64218646

• Bühler, Georg (April 1898). "Preliminary note on a recently discovered Sakya inscription". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Correspondence: Note 14): 387–389. JSTOR 25207982.

• Dani, AH (1997), Indian Palaeography (3rd ed.), New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, p. 56, ISBN 978-8121500289

• Fleet, J. F. (1907). "The Inscription on the Piprahwa Vase". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 39: 105–130. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00035541. JSTOR 25210369.

• Jinavaravansa, P. C.; Jumsai, Sumet (2003). "The Ratna Chetiya Dipaduttamarama, Colombo". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Sri Lanka. New. 48: 213–236. JSTOR 23731479.

• Mishra, S (15 September 2005), "Kalanamak: the future of Indian scented rice?", Down To Earth magazine, New Delhi: Society for Environmental Communications, retrieved 29 November 2014

• Peppe, WC (July 1898), "The Piprahwa Stupa, containing relics of Buddha", With a Note by V.A. Smith. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Article XXIII): 573–88, JSTOR 25208010 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

• Sharda, Shailvee (4 May 2015), "UP's Piprahwa is Buddha's Kapilvastu?", Times of India

• Smith, V. A. (Oct., 1898), The Piprāhwā Stūpa, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, p. 868 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

• Srivastava, KM (1979), "Kapilavastu and Its Precise Location", East and West, 29 (1/4): 61–74, JSTOR 29756506 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

• Srivastava, KM (1980), "Archaeological Excavations at Piprāhwā and Ganwaria and the Identification of Kapilavastu", The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 13 (1): 103–10

• Srivastava, KM (1996). Excavations at Piprahwa and Ganwaria (Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India No 94) (PDF). New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India.

• Srivathsan, A (20 August 2012), "Gautama Buddha, four bones and three countries", Colombo Telegraph, Colombo, Sri Lanka, retrieved 29 November 2014

• Tuladhar, Swoyambhu D. (November 2002), "The Ancient City of Kapilvastu - Revisited" (PDF), Ancient Nepal (151): 1–7

External links

• Piprahwa Museum

• ASI