Renaissance monuments to favourite sons

by Sarah Blake McHam

Renaissance Studies Vol. 19 No. 4, pp. 458-486

September, 2005

© 2005 The Society for Renaissance Studies, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The critical role played by patron saints in the spiritual and CIVlC life of Italian cities during the Medieval and Renaissance periods is well known. A city's saints not only intervened on its behalf in heaven and protected it on earth, but they informed friend or foe of the city's privileged position. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the power vacuum in the peninsula occasioned by the defeat of the Hohenstaufen and the Papacy's transfer to Avignon led to many newly autonomous Italian cities. Some of these new communes began to look beyond Christianity by claiming links to notable pagan figures that they could celebrate as forbears. These cities strove to create illustrious local histories that would define a unifying cultural heritage, nurture a sense of collective identity, and conjure up an aura of legitimacy to validate their fledgling existence. The most popular tactic involved claiming the oldest possible date for the city's origins and enlisting the most venerable founders, in a one-upmanship where antiquity was trump. The city of Rome, unsurprisingly, cultivated the tale of Romulus and Remus and proudly displayed an ancient bronze of the she-wolf suckling them as proof of its august origins. Most cities lacked artefacts that substantiated their claims, but their historians invented prestigious pedigrees. Sienese writers propagated a story that paralleled the foundation myth of Rome, about Remus' sons, twins also mothered by a wolf. Venice enlisted Hercules, Genoa, Janus, and Padua, the Trojan Antenor.1 A less common strategy was to recruit renowned literary figures of the Roman era to play a role in these campaigns to foster a sense of group identity and patriotism.

This essay will focus on a previously unnoticed large group of public monuments that was erected at civic expense to honour Roman literary notables in fifteenth-century Italy. All the memorials to Roman authors were civic commissions, prominently located in the public spaces of Italian Renaissance cities, either as freestanding statues in the main square, or installed on the exterior of the town hall, or even on the cathedral.

Almost all discussion of these projects is isolated in regional publications that consider an individual monument apart from its broader cultural context. As a result they are largely unknown to literary historians interested in the reputation of Roman authors in later periods. Most of the sculptures were not of high artistic quality, or by famous sculptors, or in major centres of artistic production like Florence or Venice. Some never made it past the design stage. For all these reasons, they have not been integrated into the study of Renaissance art history. Consequently, art historians have not realised that some of these parochial monuments introduce important features associated with the Renaissance revival of ancient art that are usually ascribed to later, more famous sculptures. Accordingly, the history of public sculptures commemorating cultural heroes has been interpreted as a nineteenth-century revival of Greek and Roman precedents, skipping over this phase in late medieval and Renaissance Italy.2

The allure of the Roman writers derived from their status in the long-gone ancient world. In the late medieval period, that civilization gained an increasing hold on the imagination of Italians, who were excited by the learning of contemporary intellectuals. Attention turned to the authors of the primary texts of antiquity in an effort to give a face to that culture. Determined efforts to find the gravesites and authentic likenesses of respected ancient writers proved largely futile. Energy refocused on a different sort of physical expression for the enthusiasm for ancient texts - the creation of suitable, durable public memorials to their authors. Scholars recognised that the Roman writers could be made immediately recognizable by identifying inscriptions and conventional symbols -- books, professorial robes, writing desks, or gestures of composing or of contemplation - and that the repertory of visual cues had already become familiar to readers of the manuscripts and early printed editions of the Roman authors' writings. The texts often began with miniature painted author portraits that could be appropriated and converted into monumental public images of local pride.

The long gap between the Roman era and the twelfth or thirteenth century when the writers were first commemorated as civic patrons presented a major stumbling block to this type of campaign for prestige. Often no indisputable information survived about the writers' place of birth or death. In other cases, the authors died far from home, or even outside Italy. These variables opened the possibility of rival cities manoeuvring to gain the sponsorship of literary notables, and even to vociferous disputes, and the commissioning of monuments to the same native son by two different cities.

Most memorials to Roman authors were erected in the fifteenth century, although sometimes they replaced earlier destroyed monuments. The humanists instrumental in recovering and editing the manuscripts of ancient authors were key advisers, motivated by their own zeal for the texts and the goal of defending the value of classical literature in a Christian culture. The introduction of printing, and consequent wider readership of Roman texts, further enhanced the prestige of identification with their authors. The enthusiasm for Roman writers spilled over into other sorts of commissions, and some were included in the painted cycles of famous men that decorated town halls and palaces. However, as they were part of larger series celebrating other types of notables such as political leaders and military heroes, and local son status was not usually a criterion, such cycles are omitted here.3

In creating sculpted memorials to ancient authors, Italian cities self-consciously emulated the precedent of ancient Greece and Rome. Well-known authors like Cicero and Pliny the Elder provided numerous allusions to the practice of erecting public monuments in commemoration of notable citizens.4 Pliny the Elder (23/24-79 A.D.), whose Natural History, an encyclopaedia of science, was highly regarded throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, offered specific information about sculptures of notable intellectuals like Gorgias (c. 483-376 BC), the sophist and rhetorician honoured by the first gilded statue ever dedicated to a human.5

The decision to erect public monuments to literary figures from antiquity had a prelude in the late Middle Ages. Not surprisingly, it was connected to Virgil and Ovid. Virgil's writings were greatly admired throughout the Roman and medieval periods. The interpretation of his Fourth Eclogue as a prophecy of Christ further ensured his reputation. Ovid was held in low esteem until his Metamorphoses came to be read as moralizing Christian allegories. Legends abounded about these authors as prophets, saints, magicians, or Christian converts.6 As neither Virgil nor Ovid died in the city of his birth, and their burial sites were uncertain, the claim to both was open to dispute. An authoritative biography recorded Virgil's death in Brindisi and his dying wish that his remains be carried to Naples, not to his native Mantua.7 By the thirteenth century, legends embellished this tale by locating his tomb on a mountain overlooking the Bay of Naples.8 Late antique and medieval sources asserted that Ovid was buried in the place to which he was exiled, on the shores of the Black Sea, very far from his place of birth in Sulmona in southern Italy. Ovid's death in such a distant and foreign location led to many fanciful legends about his supposed gravesite.9

Both Mantua and Sulmona early on tried to compensate for the lack of physical evidence of the authors' bodies and graves. They asserted their claim to their most famous native sons by placing images of them on city seals, coins and buildings. In the 1220s Mantuan authorities had a relief of Virgil seated at his writing desk, an open book before him, carved onto the facade of the Palazzo Comunale (also called the Palazzo del Podesta). Although the lower edge is inscribed, 'Virgilius Mantuanus Poetarum Clarissimus,' the figure of Virgil wears a professor's cap, and is positioned within an aedicule, facing the spectator. This formula, which suggests a teacher before an unseen class of students, was often adopted on professors' tombs in Bologna and Padua, and confirms that Virgil has been anachronistically and inappropriately made into a thirteenthcentury Italian professor (Fig. 1).10 By mid-century a version of the figure replaced Christ on Mantuan coins. At about the same time (1230-40) a second version of a figure in cattedra, usually identified as Virgil, was commissioned for the Palazzo della Ragione. It was later installed on the Palazzo Ducale's exterior, and is now preserved in the museum at the Palazzo San Sebastiano (Fig, 2). In its transplanted location, the relief lacks any architectural frame but it probably had one originally. In this characterization the figure traditionally called Virgil is carved in red Veronese marble and dressed in black painted robes. Although he faces frontally, Virgil is identified as an author. The representation follows late antique and medieval renditions of author portraits in depicting Virgil looking down at the book in which he is writing and holding an inkpot. 11

Fig. 1. Virgil, r. 1220, Mantua, facade of the Palazzo del Podesta (Comune di Mantova)

Fig.2 Virgil, r. 1230-40, Mantua, Museo della Citta, Palazzo San Sebastiano (Comune di Mantova)

Local histories of Sulmona refer to what may be late medieval sculptures -- a bust of Ovid on a city gate and one or more statues of the poet in prominent public places, but none of the sculptures survives and their dates are unspecified.12 An official city seal including Ovid and the inscription SMPE, the initials of his famous lament in exile for his birthplace, 'Sulmo mihi patria est,' was sanctioned in 1410 by King Ladislao of Anjou-Durazzo. It is said to have copied a city .emblem in use for at least a century, and probably much longer.13

In the 1220s, Padua first secured a major new Christian patron saint by commandeering the body of the Portuguese Franciscan Anthony (1195- 1231), who by happenstance died nearby. Anthony was a close associate of St Francis, and a brilliant, persuasive preacher. He had already compiled an impressive record of miracles, and his relics quickly became one of Padua's major attractions. Next, Paduan civic officials moved to establish Padua's title to secular heroes. They launched a different strategy to consolidate the city's illustrious pre-Roman and Roman past into its coalescing identity as a flourishing independent commune. Untroubled by the problems of Mantua and Sulmona, whose heroes were known to have died elsewhere, Paduans turned to excavation to uncover theirs.

In the late thirteenth century, there were two timely discoveries. The remains of Antenor, the Trojan elder who had supposedly escaped when the Greeks burned his native city and fled to north Italy, were unearthed. Legend held that Antenor arrived in Italy around 1183 B.C., even earlier than his compatriot Aeneas. This precedence incited several north Italian cities to claim him as their founder in order to gain for their site the prestige of the first settlement in the peninsula.14 For the commune in Padua, proof of its origins in the ancient past substantiated its legitimacy.

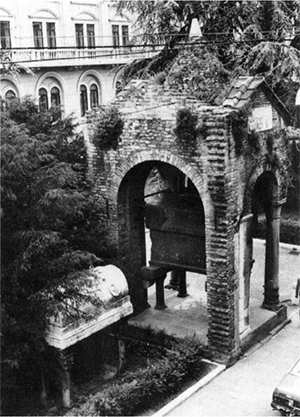

At about the same time that Antenor's bones were uncovered, an inscription thought to be from the tomb of Livy (64 or 59 BC-17 AD), the renowned Paduan-born historian of ancient Rome, was fortuitously unearthed. Lovato Lovati (1241-1309), the Paduan founder of Italian humanism, was involved in both discoveries. He orchestrated the celebrations that accompanied the finds and arranged for a prominent tomb to be erected to Antenor in the centre of Padua. It stands there today alongside a smaller sarcophagus that holds the remains of Lovati, who requested burial alongside Antenor (Fig. 3).15 By this strategy, the scholar created a physical monument that attested in permanent and public form that Antenor had died in Padua, the city he founded, and that he, Lovati, had validated the identity of the Trojan's remains. This double assertion was intended to quash rival claims to Antenor made by the chroniclers of other cities like Venice who called Antenor their own.16

Fig. 3 Tombs of Antenor and Lovato Lovati, late thirteenth century, Padua (with permission of the Comune di Padova - Assessorato ai Musei, Politiche Culturali e Spettacolo - Musei Civici)

Just as the bones of Antenor attested to the primacy of Padua's foundation, the inscription from Livy's tomb validated the status the city held during the Roman period, when it was the major city in north-eastern Italy and the birthplace of famous Romans like the great historian Livy.17 To advertise Livy's connections to Padua, the inscription tablet was set into the wall of the cloister of Padua's major early Christian church, Santa Giustina, near where it was found. It became a notable Paduan landmark and was accepted as authentic by Boccaccio and Petrarch. The latter may well have supervised the restoration and installation of the inscription. As part of this process, the inscription was gilded in an attempt to recreate its appearance in antiquity.18 Petrarch's series of letters addressed to favourite ancient figures includes a letter to Livy that closes with Petrarch's testimony that he wrote it standing before Livy's gravestone in the vestibule of Santa Giustina on 22 February 1351 (Fam. XXIV.8).19

Petrarch depended largely on the surviving sections of Livy's history of Rome for his De viris illustribus. When Francesco I da Carrara, whose family had taken over rule of Padua in 1318, commissioned him to devise a fresco cycle of famous Romans for his family palace, Petrarch drew on Livy's exemplary biographical material, and so the connection to its native son became indirectly still more part of the civic identity of Padua.20

During the fifteenth century, the practice of erecting civic monuments to famous local Roman authors accelerated. In 1413, less than a decade after Venice conquered Padua, human bones were uncovered near the site where the inscription had come to light and definitively identified as Livy's by eager Paduans predisposed to no other conclusion. The timing of the discovery leads one to suspect it was motivated to fan local campanilismo in the recently conquered city. Sicco Polentone (1376-1447), a notary in the city's chancery who later became chancellor, rushed to the site and validated the discovery. Sicco rescued Livy's remains from the monks at Santa Giustina, who began to crush them, fearing that the crowds of Paduans who congregated at the church would return to paganism. Sicco then arranged for the bones to be carried in a ceremonial procession through the streets of Padua to the town hall, the Palazzo della Ragione, and to be stored there safely until the city could build a suitable mausoleum to Livy. Sicco's letters to other scholars like the Florentines Niccolo Niccoli (c. 1364-1437) and Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370-1444) publicised the sensational news and made his reputation throughout Italy.21

A committee of six Paduan aristocrats and common citizens was appointed to decide the details of the monument on behalf of the city. The capitano of Padua, the Venetian patrician Zaccaria Trevisan, proposed that it be erected in the public space outside the Palazzo della Ragione, once the seat of government of the independent city of Padua, but as of 1405, the seat of the Venetian administrators of the city. A dispute quickly emerged when two prominent families associated with the recently deposed Carrara rulers of Padua offered to pay all costs of the monument to Livy as long as it was located in front of their palaces. The brothers Enrico and Pietro Scrovegni and Ludovico Buzzacarini made the competing bids. The locally prominent Scrovegni family, who in the fourteenth century had been Giotto's patron, had usually supported the Carrara dynasty, and the aristocratic Buzzacarini clan had married into it.22 Trevisan recognised the potential dangers to the unstable Venetian rule over the city if the remains of Livy, which were already a flashpoint of Paduan patriotism, became closely identified with the Carrara (and thus, Padua's independent past). In a deft move, he adjudicated the argument in a way that delayed the plans for a monument to Livy. When local attention refocused on other issues, he arranged for Livy's remains to be preserved inside the Palazzo della Ragione, and commemorated by a bust of Livy and an inscription.23

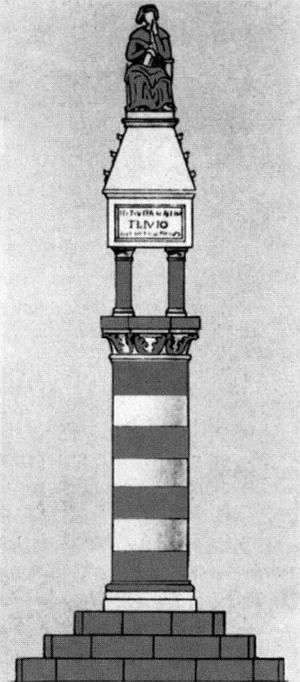

Although the committee never succeeded in erecting the monument to Livy, Polentone carefully recorded its plans in his letter to Niccoli (Fig. 4). Polentone's description indicates that the mausoleum was to be a column monument composed of alternating zones of red and white marble, reflecting Padua's colours. Even the sculpture of the historian was comprised in this patriotic colour scheme: his head, hands, and book were in white marble and his scholar's hood and robes in red marble.24 The column, installed on a stepped base, led to a platform that supported the sarcophagus holding Livy's remains, which was elevated on four smaller columns. The format of the raised sarcophagus and the red and white colour scheme were intended to recall the monuments to the other Paduan secular heroes, Antenor and Lovato Lovati. An inscription on the sarcophagus was to be in Roman lettering. 25 Above the sarcophagus, the vertical shaft narrowed into a pyramidal shape, which was surmounted by a figure of the contemplative seated Livy. The statue betrayed its Renaissance origins. Livy was dressed anachronistically in a fifteenth-century scholar's hood. Several other features of the monument, such as its several stages, the elevation of the sarcophagus on multiple columns, and the presence of a live effigy of the deceased surmounting the ensemble, reflected nearby fourteenth-century models, the Scaliger tombs in Verona.26

Fig.4 Reconstruction (after Frey), 1410s, Padua, planned monument to Livy

But Paduan officials made a concerted attempt to make the memorial suitably antique. Unlike the depictions of Virgil that portrayed him as a seated thirteenth-century university professor looking straight out over his book as though confronting a group of students or writing in the formula long established for author portraits, the statue of Livy was more archaeologically correct. His pose of holding a book on his lap with one hand, while his other rested against his cheek, was employed in ancient Greece and Rome to indicate intellectuals deep in thought. Understanding of the gesture's meaning was transmitted into later periods, as demonstrated by the example of intensely listening students stroking their chins or cheeks and leaning their heads on their hands in the classroom scenes on fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Bolognese and Paduan professors' tombs. It aptly characterised the historian Livy.27 Although spurred by somewhat garish patriotic tastes, the use of polychrome marbles, like Livy's gesture, the column monument type, and the prescribed lettering style are all self-consciously derived from Roman precedents and pay archeologically suitable homage to Livy.28

Had Livy's memorial been built, it would have initiated the Renaissance revival of Roman lettering style for an inscription. More important, it would have been the first example of the Renaissance revival of an ancient type of monument in which Roman format was accurately matched to Roman subject matter. In the medieval period, the column monument had continued in use, but always harnessed to Christian meaning, as for example, in the column of the Lion of St Mark, which towers over what was the official entrance into Venice. Because the Livy monument was never executed and remains little known, historians usually name Donatello's Dovizia in Florence as the first example in which antique format is matched to an antique subject. The figure atop the Florentine column, which is now destroyed, represented a pagan personification of abundance.29 The plans for the Livy monument in Padua precede Donatello's sculpture by about a decade; given Sicco's elaborate description of the Paduan project in his correspondence with the Florentine humanist Niccolo Niccoli, the Livy monument's design may well have influenced the Dovizia's construction and appearance.30

The ambitious Paduan project came to naught, but two more modest reliefs of Livy were installed on the exterior of the Palazzo della Ragione by the mid-fifteenth century. Their dates are not securely documented. Livy's bones were moved and enshrined behind the first relief, which depicts a half-length image of Livy, posed with his forefinger resting against his cheek and dressed in professorial garb in deliberate reflection of the unexecuted statue (Fig. 5).31 Like that project it continued the combination of anachronistic dress and archaeologically correct thoughtful pose, here refined so that Livy's forefinger is isolated against his cheek. Wolfgang Wolters convincingly associated the relief with the style of Andriolo de Sanctis, who was active in Padua in the mid-fourteenth century, but as there is no record of the sculpture before the mid-fifteenth century, it is likely to have been done then in conscious imitation of the earlier style.32 A disastrous fire at the palace in 1420 complicates understanding of the chronology of the sculpture.

Fig. 5. Relief of Livy, mid-fifteenth century, Padua, Porta delle Debite, Palazzo della Ragione (with permission of the Comune di Padova - Assessorato ai Musei, Politiche Culturali e Spettacolo - Musei Civici)

By 1435-6, a second relief of Livy (Fig. 6) was commissioned for the Palazzo della Ragione's exterior as part of a series of four Paduan notables installed at the exterior corners of the upper floor of the palace. Inscriptions identify the members of the group. They include Julius Paulus, a prominent local jurist from the second century, and two highly regarded local intellectuals, Pietro d'Abano (1250-1316), the professor and author who is credited with devising the pictorial program of the Palazzo della Ragione, and Alberto Eremitano, a thirteenth-century theologian from the Augustinian convent in Padua (whose birth and death dates are unknown).33 Like the other members of the group, Livy was situated in a scholar's study, just as professors were portrayed on their tomb monuments in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, or writers were in the author portraits that prefaced manuscripts of their texts.34 Once again, Livy's telltale gesture in the earlier portraits is recalled, although somewhat modified: he strokes his chin pensively.35

Fig.6 Relief of Livy, 1435-6, Palazzo della Ragione, exterior corner (with permission of the Comune di Padova - Assessorato ai Musei, Politiche Culturali e Spettacolo - Musei Civici)

Prompted by the excitement surrounding the discovery of Livy's bones and their transfer to the Palazzo, the Sicilian poet and humanist Antonio Beccadelli, called Panormita (1394-1471), the ambassador of Alfonso V of Aragon (also known as Alfonso I of Naples) to the Venetian government, seized the occasion to ask for the gift of a bone to bring to his ruler.36 Apparently Panormita, aware that Alfonso had earlier hired Niccolo Niccoli to report to him about Livy's bones, hoped that the present would win the king's favour.37 Alfonso's court had been a centre of efforts to reconstruct Livy's text of the history of Rome, and Panormita realised the cachet of such a trophy.38 When the king died in 1458, he bequeathed the relic to Giovanni Pontano (1429-1503), another humanist who had served as the chancellor of Naples, and subsequently as the king's secretary.39

The Piprahwa Discoveries

In January 1898, W. C. Peppe, manager of the Birdpur Estate in north-eastern Basti District, U. P., announced the discovery of soapstone caskets and jewellery inside a stupa near Piprahwa (see map) a small village on this estate. An inscription on one of these caskets appeared to indicate that bone relics, supposedly found with these items, were those of the Buddha. Since this inscription also referred to the Buddha’s Sakyan kinsmen, these relics were thus generally considered to be those which were accorded to the Sakyas of Kapilavastu, following the Buddha’s cremation. The following year, these bone relics were ceremonially presented by the (British) Government of India to the King of Siam, who in turn accorded portions to the Sanghas of Burma and Ceylon. Concerning this discovery, however, the following points should be noted:

• Peppe had been in contact with Fuhrer just before announcing the Piprahwa discovery (Fuhrer was then excavating nearby, at the Nepalese site of Sagarwa: see map). Immediately following Peppe's announcement, it was discovered that Fuhrer had been conducting a steady trade in bogus relics of the Buddha with a Burmese monk, U Ma. Among these items -– and a year before the alleged Piprahwa finds -- Fuhrer had sent U Ma a soapstone relic-casket containing fraudulent Buddha-relics of the Sakyas of Kapilavastu, together with a bogus Asokan inscription, these deceptions thus duplicating, at an earlier date, Peppe’s supposedly unique finds. Fuhrer was also found to have falsely laid claim to the discovery of seventeen inscribed, pre-Asokan Sakyan caskets at Sagarwa, his report even listing the names of seventeen ‘Sakya heroes’ which were allegedly inscribed upon these caskets. The inscribed Piprahwa casket was also considered to be both Sakyan and pre-Asokan at this time -- though its characters have since been shown to be typically Asokan -- and no other Sakyan caskets have been discovered either before or since this date.

• The bone relics themselves, purportedly 2500 years old, ‘might have been picked up a few days ago’ according to Peppe, whilst a molar tooth found among these items (and retained by Peppe) has recently been found to be that of a pig. The eminent archaeologist, Theodor Bloch, declared of the Piprahwa stupa that ‘one may be permitted to maintain some doubts in regard to the theory that the latter monument contained the relic share of the Buddha received by the Sakyas. The bones found at that place, which have been presented to the King of Siam, and which I saw in Calcutta, according to my opinion were not human bones at all’. Bloch was then Superintendent both of the ASI [Archaeological Survey of India] Bengal Circle and the Archaeological Section of the Indian Museum, and would presumably have drawn not only upon his own expertise in making this assertion, but also that of the zoologists in the Indian Museum itself. This museum -– formerly the Imperial Museum -- was then considered to be the greatest in Asia.

• The caskets appear to be identical to caskets found in Cunningham’s book ‘Bhilsa Topes’ (see Figs. 7-12) a source also used by Fuhrer for his Nigliva deceptions. A photograph of the ‘rear’ of the inscribed Piprahwa casket, taken in situ at Piprahwa in 1898 (and never published thereafter) discloses that a large sherd was missing from the base of the vessel at this time (see Fig. 8). Having closely examined this casket in 1994, I noted that a piece had since been inserted into this broken base, and that this had been ‘nibbled’ in a clumsy attempt to get this piece to fit. The photograph also reveals a curious feature on the upper aspect of the casket; this, I discovered, was a piece of sealing-wax (since transferred to the inside) which had been applied to prevent a large crack from running further. From all this, it is evident that this casket had been badly damaged from the start, a fact not mentioned in any published report. But is it likely, one is prompted to ask, that this damaged casket, supposedly containing the Buddha’s relics, would have been deposited inside the stupa anyway? Or is this the broken casket, ‘similar in shape to those found below’, which was reportedly found near the summit of the stupa, and which had vanished without trace thereafter? This casket -– also damaged -- was the first of the alleged Piprahwa finds; so did Peppe take it to Fuhrer, and did Fuhrer then forge the inscription on it? Is the Piprahwa inscription simply another Fuhrer forgery? As Assistant Editor on the Epigraphia Indica, Fuhrer would certainly have had the necessary expertise to do this, quite apart from his close association with the great epigraphist, Georg Buhler (who may have unwittingly provided Fuhrer with the necessary details, according to the existing accounts).

• On his return to the U.K., Peppe was contacted by the London Buddhist Society, and agreed to answer readers’ questions on his finds. Shortly afterwards however, the Society was notified that Peppe had suddenly been taken seriously ill, and was therefore unable to answer any questions as proposed. The Society declared the matter to be ‘in abeyance’ in consequence; but Peppe died six years later, leaving all such questions still unanswered.

• The declassified ‘Secret’ political files of the period reveal the disquiet felt by the Government of India over French and Russian influence at the Siamese royal court at this time. Hence, no doubt, this bequest!

-- Lumbini On Trial: The Untold Story. Lumbini Is An Astonishing Fraud Begun in 1896, by T. A. Phelps

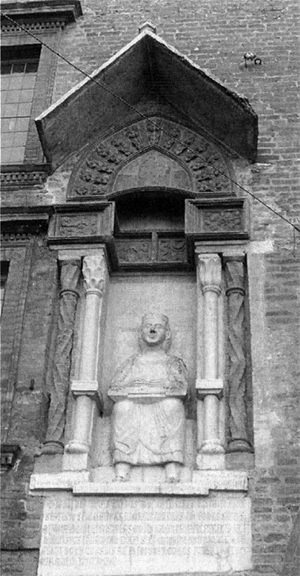

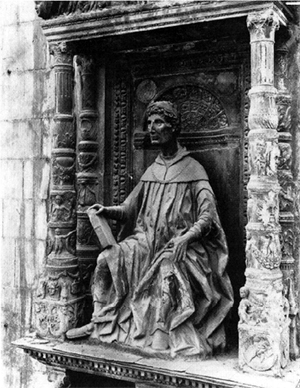

If Alfonso's interest in Livy's remains was solely an expression of the literary enthusiasm deemed appropriate for an enlightened ruler, his subsequent participation in another ancient author's cult was not. The king, Panormita, and Pontano provided the impetus to a monument to Ovid, which was eventually erected on the Palazzo Pretorio in Sulmona, in 1474 (Fig. 7).40 Sulmona had attested her loyalty to the Kingdom of Naples by surrendering to Alfonso I during his struggle with the Angevins for control of southern Italy. The king's entourage included Panormita and other humanists, who provided eyewitness accounts of Alfonso's excitement at entering the city of Ovid and his daily visits to Ovid's house.41 Their words were later summarised in Pontano's history of the reign of Alfonso I of Naples.42 The commissioner of the statue of Ovid was an official sent by Alfonso's grandson to Sulmona to strengthen its ties to the Kingdom of Naples through a programme of public works, such as reinforcing city walls, repaving streets, restoring city gates, and building a new public fountain. As the capstone of these goodwill projects, this magistrate commissioned a new statue of Ovid for the civic palace, which was by then no longer the administrative centre of an independent commune, but of a city ruled by Naples.43 The statue repeats the conventions of the earlier image of Ovid on the city's seals, specifically the figure holds a book with the letters SMPE, referring to Ovid's lament for his birthplace. The rendition of Ovid as a standing figure crowned with laurel and holding a book recalls a Roman mode of commemorating poets.44 By celebrating Sulmona's favourite son and reiterating the city's cherished emblem, the Neapolitan overlords paid their respect to the noted author. At the same time, they subsumed into the visual repertory of the Kingdom of Naples the imagery of Ovid, the erstwhile privileged symbol of Sulmona.45

Fig. 7 Statue of Ovid, 1474, Sulmona, Palazzo Pretorio (Alinari/Art Resource, New York)

Pontano, the humanist involved with the monuments to Livy and to Ovid, was the primary consultant on the late fifteenth-century memorial to Virgil that Isabella d'Este planned to erect in Mantua. Pontano's intellectual credentials and previous association with monuments to other Roman authors commended him. So did his specific knowledge of Virgil's supposed gravesite outside of Naples, which he had visited numerous times.46

The new memorial was to be far grander than the two thirteenth-century reliefs of Virgil on Mantuan public buildings. It was intended to replace a statue of Virgil supposedly toppled and thrown into a river near Mantua in 1397 by Carlo Malatesta. According to a contemporary source, Malatesta denounced Virgil as a pagan and expressed outrage that a statue had been erected to anyone other than a saint.47 The event may be apocryphal, but it launched a controversy that reached far beyond local circles. Many intellectuals, including the prominent Florentine humanist Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406), interpreted Malatesta's words as an attack on the classical poets and on the study of ancient literature in general. In response Salutati wrote a defence of poetry that for centuries shaped contemporary views on the nature of humanist learning and education.48 Pius II visited Virgil's birthplace in Mantua, decried Malatesta's infamy, and endorsed Virgil's valued role in Christian culture.49 Bartolomeo Sacchi, known as Platina (1421-81), the papal librarian who began his career as a tutor for Ludovico Gonzaga's sons, recommended to the marchese that he commission a new monument to Virgil.50 In the 1490s, Isabella d'Este, Lodovico's daughter-in-law, took up Platina's suggestion, and sought Pontano's advice on the design of the memorial.

Pontano's plans are described in an exchange of letters between Isabella and another adviser, and are also reflected in a drawing in the Louvre (Fig. 8).51 The drawing is sometimes attributed to Mantegna, who was to be the artistic consultant, but is more likely a record of Mantegna's project by an anonymous associate. Pontano advised that the sculpture should be in marble so that it could not be melted down. He recognised bronze as the more noble material but was wary of its use, given the history of the deliberate destruction of the earlier monument to Virgil. He stipulated that Virgil's portrait be based on a bust, considered an authentic likeness of the poet, then in the hands of Battista Fiera, a Mantuan doctor and poet who was Mantegna's close friend.52 Pontano further specified that Virgil should be depicted in a simple but archeologically correct manner with antique sandals, toga, mantle, and laurel wreath. He recommended that the monument's base have a suitable brief inscription, 'Po Virgilius Mantuanus Isabella Marchionissa Mantuae restituit,' and follow ancient models.53 The inscription accurately imitates the lettering style of ancient Roman monuments and reflects Mantegna's important role in reviving the Roman Imperial majuscule.54 It has been argued that the base of the monument derives from that supporting Trajan's Column. This would have made it the first accurate reconstruction of an ancient pedestal in the Renaissance, although the winsome relaxing putti alongside the garland that replace their more mature, energetically flying ancient counterparts are typical inventions of Mantegna.55 More significantly, had the Virgil memorial been built, it would have been the first freestanding full-length sculpture of a specific historical individual in the Renaissance, antedating by decades Baccio Bandinelli's design for a portrait statue in Carrara commemorating Andrea Doria, the Genoese admiral of the fleets of Francis I, and then Charles V.56

Fig. 8 (attrib.) Mantegna, Monument to Virgil, Co 1500, drawing (Reunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, New York)

The next two monuments date from the last twenty years of the fifteenth century and result from a case of contested identity. They physically proclaim the rival claims of Verona and Como to be the birthplace of Pliny the Elder. The popularity of Pliny's Natural History throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance is attested by the number of surviving manuscripts of the encyclopaedia, by the various Renaissance commentaries on it and by the early date of its first printing (1469).57 There is some question about which monument came first, but no doubt that their commissions were spurred by the competition for prestigious favourite sons.

Como's claim to be Pliny's birthplace originated in the fragmentary biography of the encyclopaedist written by the historian Suetonius, the only surviving near-contemporary source. Suetonius' friendship with Pliny's nephew, Pliny the Younger (c. 61-112 A. D.) lent credibility to his information.58 Manuscript copies of Pliny the Younger's letters were known throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance in several different versions, and so scholars were well aware of his connections with Suetonius.59 The trustworthiness of Suetonius' biography was further strengthened in the minds of Renaissance intellectuals by its inclusion in many manuscripts of the Natural History. When this practice was repeated in the first edition of that encyclopaedia printed by Johannes de Spira in Venice in 1469, Suetonius' text became identified with Pliny in the minds of its readers. But the Roman historian's biography of Pliny was fragmentary and very short, so it offered no details to corroborate his assertion that Pliny the Elder had been born in Como.60

Verona countered with evidence that apparently trumped Suetonius: Pliny's own words. In his encyclopaedia, Pliny seemed to refer to the poet Catullus, who was definitely from Verona, as his compatriot.61 The question of Pliny the Elder's origins became further confused during the Middle Ages by the gradual merging of his identity with that of Pliny the Younger, his nephew and adopted son. Finally, in the early fourteenth century, the Veronese priest and scholar Giovanni de Matociis (d. 1337) distinguished the two and paired this scholarly rediscovery with an assertion that was music to his compatriots' ears: both Plinys were born in Verona.62 Petrarch reiterated that conclusion, and persuaded many other fourteenth- and fifteenth-century intellectuals that Verona spawned both Plinys.63

In 1480, Como's civic officials mounted a counter-attack by commissioning statues of Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger for their cathedral's facade (Figs. 9 and 10).64 They were motivated by pride in their city's Roman heritage and in its later history as an independent commune from the eleventh to early fourteenth century. Como had defended itself successfully against Milanese domination for centuries, but in the 1330s, Azzo Visconti conquered it. In 1447, when the last Visconti ruler of Milan died, Como declared herself an independent republic. The Sforza soon seized control, and quickly subjugated Como again. The murder of Galeazzo Maria Sforza in 1476, and the tumult over the succession between his brother Ludovico and his young son, Gian Galeazzo, seems to have spurred aspirations in Como to create at least a symbolic visual language that alluded to the city's illustrious prior periods of independent history. Its civic officials recognised the power of that past history in rallying a sense of local identity.

In addition to a roster of religious themes appropriate to the Virgin Mary, dedicatee of the cathedral, they commissioned for its exterior small mythological scenes interpreted in Christian terms, a statue on the cathedral's side of Cecilius Statius, a little known Roman poet from Como, and statues of the two Plinys.65 Just to the left of Pliny the Elder is a small portrait of Cicco Simonetta (1410-80), the longtime close adviser of Francesco Sforza, and of his successor, Galeazzo Maria Sforza. After Galeazzo Maria's assassination, Simonetta advised the former ruler's wife Bona, regent of her son Gian Galeazzo, and for several years was the virtual ruler of Milan. In 1479, Ludovico seized power, imprisoned Simonetta, and shortly thereafter had him killed. By putting Simonetta's portrait on the facade, the overseers of Como cathedral boldly asserted their loyalty to their losing side in the dynastic struggle.66

Fig. 9 Pliny the Elder, 1480s, Como, Cathedral (Alinari/Art. Resource, New York)

Fig. 10 Pliny the Younger, 1480s, Como, Cathedral (Alinari/Art Resource, New York)

The statues of Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger dominate the Cathedral's facade. They are over-life-size and flank the main portal. Scale and pride of place make the Roman authors by far the most dominant elements of the facade's iconography. Both are seated within niches elaborately ornamented with classicising decoration like small genii, garlands, mythological creatures, and masks appropriate to the era of the authors. They hold books and wear scholars' robes and laurel wreaths, indicative of their status as acclaimed writers. Small reliefs below each figure depict narratives from their lives: Pliny the Elder's death while recording Vesuvius' emption, and both authors writing and conversing with fellow Roman officials and intellectuals.

Honouring Romans without any Christian connection whatsoever on a cathedral facade is unprecedented. The city authorities' decision to commission large, isolated sculptures in the most prominent possible position is even more radical. The elaboration of the images of Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger with small narrative reliefs of events from their lives in a predella arrangement below the figures follows a convention usually associated with altarpieces or with sculptures of saints. Several well-known examples of such sculptures of the patron saints of guilds by Donatello and Nanni di Banco are found at Orsanmichele in Florence. Anyone familiar with the conventions of church decoration immediately recognises that the two Plinys are treated as though they were Christian patron saints of Como. In 1587, at the height of the Catholic Reformation, the bishop of Vercelli made just that point. While conducting an official visitation, he demanded the removal of these heretical sculptures from the facade. The civic officials of Como dug in their heels and refused.67 The bishop's decree was never enforced, for reasons unspecified by contemporary sources.

In 1498, Benedetto Giovio devised new inscriptions for the sculptures. Benedetto was a logical choice for the privilege as he was famous for his erudition on Pliny the Elder, Vitruvius, inscriptions, and the history of Como. The local sculptors Tommaso and Giacomo Rodari signed the niche of Pliny the Younger.68 Historians debate whether this means that the brothers carved the statues of the two Plinys, or that they executed, or reworked, the elaborate classicising niches that surround them when the new inscriptions were added. Most scholars argue that the statues are closer to the style of their father, Giovanni Rodari, who probably carved them in the 1480s.69 If the current scholarly consensus is accurate, the statues of Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger were carved before the statue of Pliny the Elder in Verona. Nevertheless, the new inscriptions added in 1498 postdate the Veronese commission and respond to it vehemently. It is worded so that Pliny the Elder seems to say: 'Such a great honour pleases me, but even more it pleases me that my fellow citizens [italics added] have installed this memorial to me.'70

Fig. 11 The Loggia del Consiglio, r. 14805, Piazza dei Signori, Verona (Soprintendenza per i beni architettonici e per it paesaggio di Verona)

There is no question that Pliny's words identifying the people of Como as compatriots were meant to answer the unwarranted decision of the Veronese to include him among the statues of notable native sons on the roofline of a newly constructed civic building.

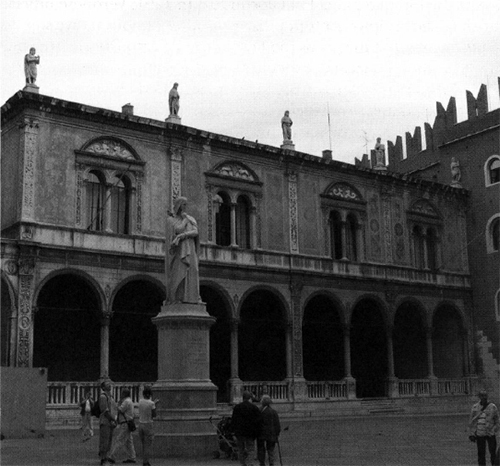

The Loggia del Consiglio (Fig. 11) stands in the Piazza dei Signori, one of Verona's most important public spaces. Local officials had first requested approval of its construction from their Venetian overlords in the mid-fifteenth century, but permission was not granted until 1476, when the Veronese agreed to pay for it themselves. Erected over the next ten to fifteen years, the Loggia is considered the first Renaissance building in Verona and sometimes attributed to the local architect Fra Giocondo.71 In 1491, Veronese officials tried to commission the sculptor Antonio Rizzo, another famous native son, to carve the roofline statues, but Rizzo was too busy at the Palazzo Ducale in Venice. The following year they entrusted execution of the sculptures to a little-known carver called Alberto da Milano and his unidentified collaborators.72

The series of statues is witness to Verona's illustrious Roman past and intended as a rallying point for local pride. At the time the design was conceived, Verona had been ruled by Venice for almost eight decades. The line-up of famous Romans born in Verona gave durable public expression to a theme dear to Veronese humanists.73 Like the histories they wrote, the statues conveyed the patriotic message of pride in the distinguished pedigree of the city, which, unlike its overlord, Venice, had been a flourishing centre in Roman times. Pliny (Fig. 12a) stands amid other famous Romans from Verona, Catullus (Fig. 12b), the architect Vitruvius (Fig. 12c), the Augustan poet Aemilius Macer, who was an older contemporary of Ovid, and the biographer Cornelius Nepos (c. 99-c. 23 B.C.).74 They are all dressed in long flowing robes and, except for Vitruvius, carry a book. Inscriptions on the plinths below each statue identify the figure by name. They resemble each other and seem a unified cohort, a similarity that serves to underscore the message of their common Veronese origins.

Fig. 12 Alberto da Milano, roofline statues of (a) Pliny, (b) Catullus, (c) Vitruvius, 1492, The Loggia del Consiglio, (Soprintendenza per i beni archtettonici e per il

In 1493 the statues were prominently installed on the Loggia to offset not only Como's earlier sculpture commission, but the most serious intellectual challenge to Verona's claim to Pliny the Elder up until that point. Poliziano (1454-94) and Ermolao Barbaro (c. 1410-93), the Venetian patriarch and humanist, were both highly recognised experts on the Natural History who had just published studies that included their conclusion that Pliny had been born in Como.75 Their erudition and objectivity -- neither Poliziano nor Barbaro was from Como or Verona -- made their results difficult to attack. Nevertheless Veronese civic officials erected the statue of Pliny and hired a local historian to draft still another round of Verona's claims in a verbal warfare that continued for centuries.76

The public commissions to commemorate favourite sons trail off at the end of the fifteenth century. The vogue for these monuments is mainly a late fifteenth-century phenomenon. They were the product of the zeal to impart a tangible reality to the greatly admired ancient Roman culture -- and a highly visible means to assert a connection to it. Prominent sculpted memorials to city founders or native sons became an effective way of demonstrating this prized pedigree. Only the city of Rome had an indisputably genuine extant symbol of its foundation, the She-Wolf. In 1471 the Etruscan bronze was displayed on the Campidoglio, along with newly cast bronzes of Romulus and Remus, as a public emblem of Christian Rome rebuilt by the popes after their return from Avignon.77 By contrast, Padua's tomb commemorating its founder must have seemed a poor substitute. Although Lovati tried to make it look antique by reusing pieces of old sarcophagi, the shrine betrayed its medieval origins, and could be identified as Antenor's only by the inscription. Furthermore Antenor, like other desirable mythological and legendary founders, was claimed by several Italian cities.

Civic authorities recognised that they had a better chance to make an exclusive stake to the prestige and legitimacy that antique origins provided through their famous native sons. Attention turned to the authors whose writings transmitted knowledge of ancient Rome in an effort to give that culture a tangible public presence in Renaissance Italy. The humanists instrumental in recovering and editing the manuscripts of ancient authors were key advisers, motivated by the goal of defending the value of classical literature in a Christian society. They recognised that public monuments honouring these writers could be created by adapting to large-scale and durable format the standard props already popularised through their illuminated portraits in manuscripts. Additional, immediately recognizable signs of academic authenticity to enhance the Roman authors' images could be appropriated from the scenes of late medieval classrooms depicted on the tombs commemorating professors at the universities of Bologna and Padua. Although some authors who were very popular in the fifteenth century like Cicero, Horace, or Sallust, were not memorialised, most of the authors commemorated in public monuments -- Virgil, Ovid, Livy, Pliny the Elder, Pliny the Younger, Vitruvius, and Catullus -- correlate with those whose writings were most influential, well known in manuscript form, and the earliest printed in Italy. The little known writers, like Caecilius Statius, commemorated on the facade of the Cathedral in Como, or Aemilus Macer and Cornelius Nepos, whose statues join the roster of authors claimed by Verona on the roofline of its Loggia del Consiglio, must be counted as expressions of exuberant local pride.

Cities competed for the honour of claiming prominent Roman authors as their own and of making public monuments commemorating them part of their civic identities. Regimes in power employed the status of these associations strategically to redound to their credit. Subject cities evoked the identification to kindle citizens' pride by conveying in symbolic terms the illustrious Roman past of their cities in the face of current loss of autonomy. For Verona and Padua, subjugated by Venice, a city with no Roman history, allusions to their own ancient pedigrees carried a special patriotic resonance.

Although many of the monuments were never executed or were sculpted by minor artists, integrating these overlooked commissions into the history of Italian Renaissance art modifies our conception of the period. The self-conscious goal of their Italian commissioners to honour prestigious ancient heroes in an archaeologically correct style that conveyed understanding of and connection to the revered Roman past, means that these idiosyncratic local monuments present a number of innovations that pioneer the integration of the visual language of antiquity into Italian Renaissance art.

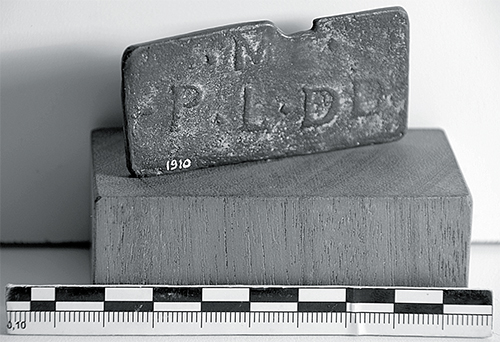

Rutgers University