by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/6/21

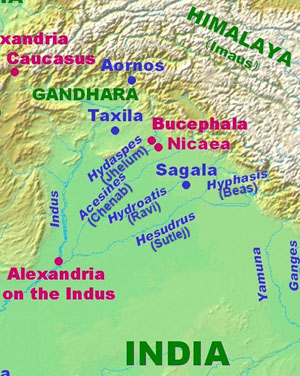

47. The country inland from Barygaza is inhabited by numerous tribes, such as the Arattii, the Arachosii, the Gandaraei and the people of Poclais, in which is Bucephalus Alexandria. Above these is the very warlike nation of the Bactrians, who are under their own king. And Alexander, setting out from these parts, penetrated to the Ganges, leaving aside Damirica and the southern part of India; and to the present day ancient drachmae are current in Barygaza, coming from this country, bearing inscriptions in Greek letters, and the devices of those who reigned after Alexander, Apollodorus and Menander. [Librarian's Comment: A significant and presumably knowing omission from the Wikipedia article on the Periplus is paragraph 47, missing along with everything from 42-48, this extraordinary piece of testimony that cuts against the general trend of Indian pseudo-history that contends Alexander never reached the Ganges. Indeed, never crossed the Indus, spooked by Sandrocottus' herd of war elephants.]

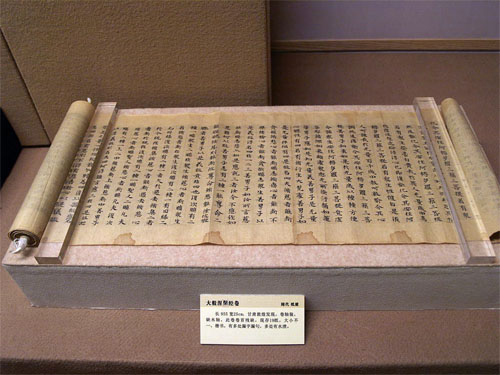

-- The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century, Translated & edited by W.H. Schoff (London, Bombay & Calcutta 1912).

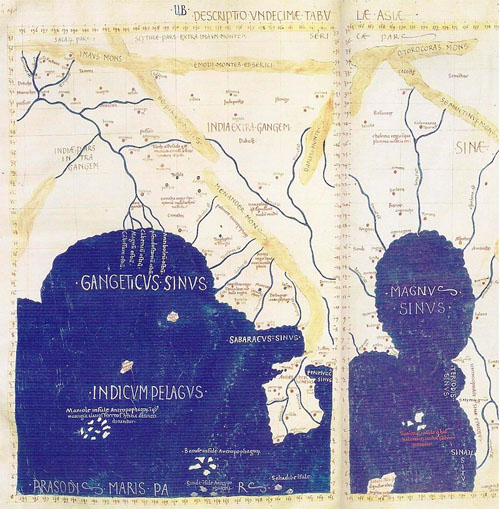

Gangaridai in Ptolemy's Map

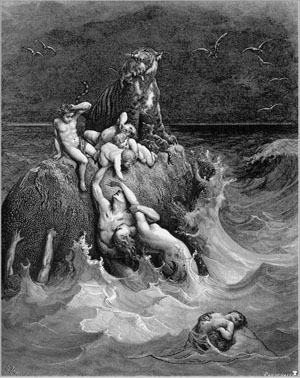

Gangaridai (Greek: Γανγαρίδαι; Latin: Gangaridae) is a term used by the ancient Greco-Roman writers to describe a people or a geographical region of the ancient Indian subcontinent. Some of these writers state that Alexander the Great withdrew from the Indian subcontinent because of the strong war elephant force of the Gangaridai. The writers variously mention the Gangaridai as a distinct tribe, or a nation within a larger kingdom (presumably the Nanda Empire).

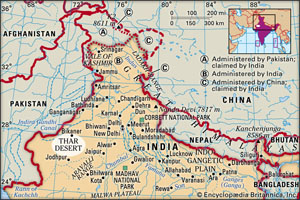

A number of modern scholars locate Gangaridai in the Ganges Delta of the Bengal region, although alternative theories also exist. Gange or Ganges, the capital of the Gangaridai (according to Ptolemy), has been identified with several sites in the region, including Chandraketugarh and Wari-Bateshwar.

Names

The Greek writers use the names "Gandaridae" (Diodorus), "Gandaritae", and "Gandridae" (Plutarch) to describe these people. The ancient Latin writers use the name "Gangaridae", a term that seems to have been coined by the 1st century poet Virgil.[1]

Some modern etymologies of the word Gangaridai split it as "Gaṅgā-rāṣṭra", "Gaṅgā-rāḍha" or "Gaṅgā-hṛdaya". However, D. C. Sircar believes that the word is simply the plural form of "Gangarid" (derived from the base "Ganga"), and means "Ganga (Ganges) people".[2]

Greek accounts

Several ancient Greek writers mention Gangaridai [rather, "Gandaridae; Gandaritae and Gandridae"???], but their accounts are largely based on hearsay.[3]

Diodorus

The earliest surviving description of Gangaridai ["Gandaridae"????] appears in Bibliotheca historica of the 1st century BCE writer Diodorus Siculus. This account is based on a now-lost work, probably the writings of either Megasthenes or Hieronymus of Cardia.[4]

In Book 2 of Bibliotheca historica, Diodorus states that "Gandaridae" (i.e. Gangaridai[???]) territory was located to the east of the Ganges river, which was 30 stades wide. He mentions that no foreign enemy had ever conquered Gandaridae, because of its strong elephant force.[5] He further states that Alexander the Great advanced up to Ganges after subjugating other Indians, but decided to retreat when he heard that the Gandaridae had 4,000 elephants.[6]

This river [Ganges], which is thirty stades in width, flows from north to south and empties into the ocean, forming the boundary towards the east of the tribe of the Gandaridae, which possesses the greatest number of elephants and the largest in size. Consequently no foreign king has ever subdued this country, all alien nations being fearful of both the multitude and the strength of the beasts. In fact even Alexander of Macedon, although he had subdued all Asia, refrained from making war upon the Gandaridae alone of all peoples; for when he had arrived at the Ganges river with his entire army, after his conquest of the rest of the Indians, upon learning that the Gandaridae had four thousand elephants equipped for war he gave up his campaign against them.

-- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 2.37.2-3. Translated by Charles Henry Oldfather.[7]

37. The land of the Indians has also many large navigable rivers which have their sources in the mountains lying to the north and then flow through the level country; and not a few of these unite and empty into the river known as the Ganges. This river, which is thirty stades in width, flows from north to south and empties into the ocean, forming the boundary towards the east of the tribe of the Gandaridae, which possesses the greatest number of elephants and the largest in size. Consequently no foreign king has ever subdued this country, all alien nations being fearful of both the multitude and the strength of the beasts. In fact even Alexander of Macedon, although he had subdued all Asia, refrained from making war upon the Gandaridae alone of all peoples; for when he had arrived at the Ganges river with his entire army, after his conquest of the rest of the Indians, upon learning that the Gandaridae had four thousand elephants equipped for war he gave up his campaign against them.1 [A fuller account of this incident is given in Book 17. 93. But Alexander did not reach the river system of the Ganges, the error being due to a confusion of the Ganges with the Sutlej, a tributary of the Indus; cp. W. W. Tarn, “Alexander and the Ganges,” Journal of Hellenic Studies, 43 (1923), 93 ff.]

The river which is nearly the equal of the Ganges and is called the Indus rises like the Ganges in the north, but as it empties into the ocean forms a boundary of India; and in its course through an expanse of level plain it receives not a few navigable rivers, the most notable being the Hypanis,2 [In Book 17. 93. 1 and Arrian, 6. 24. 8, this river is called the Hyphasis, which is the name preferred by most modern writers. Strabo (15. 1. 27, 32), however, calls it the Hypanis, and Quintus Curtius (9. 1. 35), Hypasis.] Hydaspes, and Acesinus. And in addition to these three rivers a vast number of others of every description traverse the country and bring it about that the land is planted in many gardens and crops of every description. Now for the multitude of rivers and the exceptional supply of water the philosophers and students of nature among them advance the following cause: The countries which surround India, they say, such as Scythia, Bactria, and Ariana, are higher than India, and so it is reasonable to assume that the waters which come together from every side into the country lying below them, gradually cause the regions to become soaked and to generate a multitude of rivers. And a peculiar thing happens in the case of one of the rivers of India, known as the Silla, which flows from a spring of the same name; for it is the only river in the world possessing the characteristic that nothing cast into it floats, but that everything, strange to say, sinks to the bottom.

-- Diodorus of Siciliy in Twelve Volumes, Volume I, Books II (continued) 35-IV, 58, with an English translation by C.H. Oldfather, Professor of Ancient History and Languages, The University of Nebraska, 1935 (p. 9-13)

In Book 17 of Bibliotheca historica, Diodorus once again describes the "Gandaridae", and states that Alexander had to retreat after his soldiers refused to take an expedition against the Gandaridae. The book (17.91.1) also mentions that a nephew of Porus fled to the land of the Gandaridae,[6] although C. Bradford Welles translates the name of this land as "Gandara".[8]

Beyond the Hydaspes was the powerful kingdom of Porus, who held sway as far as the Acesines, which we know as the Chenab, the next of the "Five Rivers." East of the Chenab, in the lands of the Ravee and the Beas, were other small principalities, and also free "kingless" peoples, who owned no master.

-- Chapter XVIII: The Conquest of the Far East, Excerpt from "History of Greece for Beginners", by J. B. Bury, M.A.

He [Alexander] questioned Phegeus about the country beyond the Indus River, and learned that there was a desert to traverse for twelve days, and then the river called Ganges, which was thirty-two furlongs in width and the deepest of all the Indian rivers. Beyond this in turn dwelt the peoples of the Tabraesians [misreading of Prasii[1]] and the Gandaridae, whose king was Xandrames. He had twenty thousand cavalry, two hundred thousand infantry, two thousand chariots, and four thousand elephants equipped for war. Alexander doubted this information and sent for Porus, and asked him what was the truth of these reports. Porus assured the king that all the rest of the account was quite correct, but that the king of the Gandaridae was an utterly common and undistinguished character, and was supposed to be the son of a barber. His father had been handsome and was greatly loved by the queen; when she had murdered her husband, the kingdom fell to him.

-- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 17.93. Translated by C. Bradford Welles.[8]

In Book 18 of Bibliotheca historica, Diodorus describes India as a large kingdom comprising several nations, the largest of which was "Tyndaridae" (which seems to be a scribal error for "Gandaridae"). He further states that a river separated this nation from their neighbouring territory; this 30-stadia wide river was the greatest river in this region of India (Diodorus does not mention the name of the river in this book). He goes on to mention that Alexander did not campaign against this nation, because they had a large number of elephants.[6] The Book 18 description is as follows:

…the first one along the Caucasus is India, a great and populous kingdom, inhabited by many Indian nations, of which the greatest is that of the Gandaridae, against whom Alexander did not make a campaign because of the multitude of their elephants. The river Ganges, which is the deepest of the region and has a width of thirty stades, separates this land from the neighbouring part of India. Adjacent to this is the rest of India, which Alexander conquered, irrigated by water from the rivers and most conspicuous for its prosperity. Here were the dominions of Porus and Taxiles, together with many other kingdoms, and through it flows the Indus River, from which the country received its name.

-- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 18.6.1-2. Translated by Russel M. Geer.[9]

Diodorus' account of India in the Book 2 is based on Indica, a book written by the 4th century BCE writer Megasthenes, who actually visited India. Megasthenes' Indica is now lost, although it has been reconstructed from the writings of Diodorus and other later writers.[6] J. W. McCrindle (1877) attributed Diodorus' Book 2 passage about the Gangaridai to Megasthenes in his reconstruction of Indica.[10] However, according to A. B. Bosworth (1996), Diodorus' source for the information about the Gangaridai was Hieronymus of Cardia (354–250 BCE), who was a contemporary of Alexander and the main source of information for Diodorus' Book 18. Bosworth points out that Diodorus describes Ganges as 30 stadia wide; but it is well-attested by other sources that Megasthenes described the median (or minimum) width of Ganges as 100 stadia.[4] This suggests that Diodorus obtained the information about the Gandaridae from another source, and appended it to Megasthenes' description of India in Book 2.[6]

Plutarch

Plutarch (46-120 CE) mentions the Gangaridai as "'Gandaritae" (in Parallel Lives - Life of Alexander 62.3) and as "Gandridae" (in Moralia 327b.).[1]

The Battle with Porus depressed the spirits of the Macedonians, and made them very unwilling to advance farther into India... This river [the Ganges], they heard, had a breadth of two and thirty stadia, and a depth of 1000 fathoms, while its farther banks were covered all over with armed men, horses and elephants. For the kings of the Gandaritai and the Prasiai were reported to be waiting for him (Alexander) with an army of 80,000 horse, 200,000 foot, 8,000 war-chariots, and 6,000 fighting elephants.

-- Plutarch[11]

Other writers

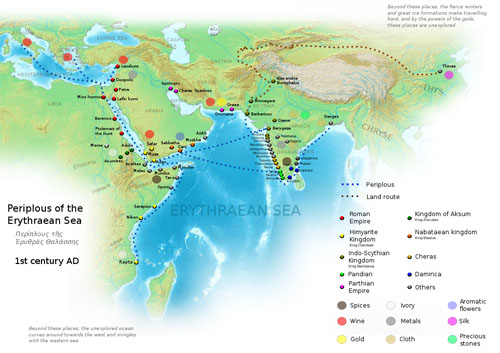

A modern map identifying the places depicted in the Periplous of the Erythraean Sea

Ptolemy (2nd century CE), in his Geography, states that the Gangaridae occupied "all the region about the mouths of the Ganges".[12] He names a city called Gange as their capital.[13] This suggests that Gange was the name of a city, derived from the name of the river. Based on the city's name, the Greek writers used the word "Gangaridai" to describe the local people.[12]

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea does not mention the Gangaridai, but attests the existence of a city that the Greco-Romans described as "Ganges":

There is a river near it called the Ganges, and it rises and falls in the same way as the Nile. On its bank is a market-town which has the same name as the river, Ganges. Through this place are brought malabathrum and Gangetic spikenard and pearls, and muslin of the finest sorts, which are called Gangetic. It is said that there are gold-mines near these places, and there is a gold coin which is called caltis.

-- Anonymous, Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Translated by Wilfred Harvey Schoff.[14]

Dionysius Periegetes (2nd-3rd century CE) mentions "Gargaridae" located near the "gold-bearing Hypanis" (Beas) river. "Gargaridae" is sometimes believed to be a variant of "Gangaridae", but another theory identifies it with Gandhari people. A. B. Bosworth dismisses Dionysius' account as "a farrago of nonsense", noting that he inaccurately describes the Hypanis river as flowing down into the Gangetic plain.[15]

Gangaridai also finds a mention in Greek mythology. In Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica (3rd century BCE), Datis, a chieftain, leader of the Gangaridae who was in the army of Perses III, fought against Aeetes during the Colchian civil war.[16] Colchis was situated in modern-day Georgia, on the east of the Black Sea. Aeetes was the famous king of Colchia against whom Jason and the Argonauts undertook their expedition in search of the "Golden Fleece". Perses III was the brother of Aeetes and king of the Taurian tribe.

I took notice that the Oreitae and Oxydracae pretended to be descended from Dionusus. The like was said of the Gargaridae, who lived upon the Hypanis [Beas River], near Mount Hemodus, and are mentioned by the poet Dionysius.82 [Dionys. Perieg. v. 1143. Pompon. Mela speaks of the city Nusa in these parts. Urbium, quas incolunt, Nysa est clarissima et maxima: montium, Meros, Jovi sacer. Famam hic prjecipuam habent in illa genitum, in hujus specu Liberum arbitrantur esse nutritum: unde Graecis auctoribus, ut semori Jovis insitum dicerent, aut materia ingessit, aut error. L. 3. c. 7. p. 276. The most knowing of the Indi maintained that Dionusos came from the west. (Google translate: Nysa is the most famous and the largest of the cities which they inhabit: mountains, Meros, sacred to Jupiter. They have a special reputation here, begotten in it, they think in this cave that they had been brought up; whence, according to Greek authors, to say that it was implanted in the seed of Jupiter, it either caused the matter, or an error.)] [x]

He styles them from their worship and extraction "the servants of Dionusos." As there was a Caucasus in these parts, so was there also a region named 83 [Colchis mentioned by AEthicus, and styled Colche: also by Ptolemy.] Colchis; which appears to have been a very flourishing and powerful province. It was situated at the bottom of that large isthmus, which lies between the Indus and Ganges: and seems to have comprehended the kingdoms, which are styled Madura, Tranquebar, and Cochin. The Gargaridae, who lived above upon the Hypanis, used to bring down to the Colchians the gold of their country, which they bartered for other commodities. The place, where they principally traded, was the city Comar, or Comarin, at the extremity of the isthmus to the south. The Colchians had here the advantage of a pearl fishery, by which they must have been greatly enriched. A learned commentator upon the ancient geographers gives this account of their country. 84 [Geographi Minores. Prolegom.] Post Barim amnem in Aiorum regione est Elancon emporium, et Cottiara metropolis, ac Comaria promontorium; et oppidum in Periplo Erythrari [c] et [c], nunc servato nomine Comarin. Ab hoc promontorio sinus Colchicus incipit, cui Colchi, [x], emporium adjacens, nomen dederunt [Google translate: Next to the river Bari, in the region of the Aii, is Elancon, the commercial port. and Cottiara the metropolis, and Comaria the promontory; and a town in the Periplo of Erythrarus, now being maintained by the name of Comarin. From this promontory the bay of Colchicus begins to whom the Colchis, adjoining the bazaar, gave their name.]. The Periplus Maris Erythraei, here spoken of, is a most valuable and curious treatise, whoever may have been the author: and the passage chiefly referred to is that which follows: 85 [Arriani Peripl. Maris Erythraei, apud Geograph. Graecos Minores. v. i. P. 33. Dionysius calls this region [x] instead of [x]. [x]. Perieg. v. 1148. And others have supposed it was named Colis from Venus Colias. But what has any title of a Grecian Goddess to do with the geography of India? The region was styled both Colica, and Colchica. It is remarkable, that as there was a Caucasus and Regio Colica, as well as Colchica, in India: so the same names occur among the Cutheans upon the Pontus Euxinus. Here was Regio Colica, as well as Cholcica at the foot of Mount Caucasus. Pliny L. 6. c. 5. p. 305. They are the same name differently expressed.] [x]. "From Elabacara extends a mountain called Purrhos, and the coast styled Paralia" (or the pearl coast), "reaching down to the most southern point, where is the great fishery for pearl, which people dive for. It is under a king named Pandion; and the chief city is Colchi. There are two places; where they fish for this 86 [Paralia seems at first a Greek word; but is in reality a proper name in the language of the country. I make no doubt, but what we call Pearl was the Paral of the Amonians and Cuthites. Paralia is "the Land of Pearls." All the names of gems, as now in use, and of old, were from the Amonians: Adamant, Amethyst, Opal, Achates or Agate, Pyropus, Onyx, Sardonyx, AEtites, Alabaster, Beril, Coral, Cornelian. As this was the shore, where these gems were really found, we may conclude, that Paralia signified the Pearl Coast. There was pearl fishery in the Red Sea, and it continues to this day near the island Delaqua. Purchass. v. 5. p. 778. In these parts, the author of the Periplus mentions islands, which he styles [x], or Pearl Islands. See Geogr. Gr. Minores. Periplus. v. i. p. 9.] commodity: of which the first is Balita: here is a fort, and an harbour. In this place, many persons who have a mind to live an holy life, and to separate themselves from the world, come and bathe, and then enter into a state of celibacy. There are women, who do the same. For it is said that the place at particular seasons every month is frequented by the Deity of the country, a Goddess who comes and bathes in the waters. The coast, near which they fish for pearl, lies all along from Comari to Colchi. It is performed by persons, who have been guilty of some crime, and are compelled to this service. All this coast to the southward is under the aforementioned king Pandion. After this there proceeds another tract of coast, which forms a gulf."

The author then proceeds to describe the great trade, which was carried on by this people, and by those above, upon the Hypanis and Ganges: and mentions the fine linen, which was brought down from Scythia Limyrica, and from Comara, and other places. And if we compare the history, which he gives, with the modern accounts of this country, we shall find that the same rites and customs still prevail; the same manufactures are carried on: nor is the pearl fishery yet exhausted. And if any the least credit may be afforded to etymological elucidation, the names of places among the Cuthite nations are so similar in themselves, and in their purport, that we may prove the people to have been of the same family; and perceive among them the same religion and customs, however widely they were scattered. The mountains Caucasus and 87 [The mountain Pyrrhus, [x], was an eminence sacred to Ur, or Orus; who was also called Cham-Ur, and his priests Chamurin. The city Ur in Chaldea is called Chamurin by Eupolemus, who expresses it [x]. Euseb. Praep. Evang. L. 9. p. 418. Hence this promontory in Colchis Indica is rendered Comar by the author of the Periplus; and at this day it is called Comorin. The river Indus is said to run into a bay called Sinus Saronicus. Plutarch. de Flumin. Sar-On, Dominus Sol.] Pyrrhus, the rivers Hypanis, Baris, Chobar, Soana, Cophis, Phasis, Indus, of this country, are to be found among the Cuthite nations in the west. One of the chief cities in this country was Cottiara. This is no other than Aracotta reversed; and probably the same that is called Arcot at this day. The city Comara, and the promontory Comarine are of the same etymology as the city Ur in Chaldea; which was called Camar and Camarina from the priests and worship there established. The region termed Aia above Colchis was a name peculiarly given by the Amonians to the places, where they resided. Among the Greeks the word grew general; and Aia was made to signify any land: but among the Egyptians, at least among the Cuthites of that country, as well as among those of Colchis Pontica, it was used for a proper name of their country:

-- A New System, Or, An Analysis of Ancient Mythology: Wherein an Attempt is Made to Divest Tradition of Fable; and to Reduce the Truth to its Original Purity, by Jacob Bryant, 1775

Latin accounts

The Roman poet Virgil speaks of the valour of the Gangaridae in his Georgics (c. 29 BCE).

On the doors will I represent in gold and ivory the battle of the Gangaridae and the arms of our victorious Quirinius.

-- Virgil, "Georgics" (III, 27)

Quintus Curtius Rufus (possibly 1st century CE) noted the two nations Gangaridae and Prasii:

Next came the Ganges, the largest river in all India, the farther bank of which was inhabited by two nations, the Gangaridae and the Prasii, whose king Agrammes kept in field for guarding the approaches to his country 20,000 cavalry and 200,000 infantry, besides 2,000 four-horsed chariots, and, what was the most formidable of all, a troop of elephants which he said ran up to the number of 3,000.

-- Quintus Curtius Rufus[17]

Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) states:

... the last race situated on its [Ganges'] banks being that of the Gangarid Calingae: the city where their king lives is called Pertalis. This monarch has 60,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry and 700 elephants always equipped ready for active service. [...] But almost the whole of the peoples of India and not only those in this district are surpassed in power and glory by the Prasi, with their very large and wealthy city of Palibothra [Patna], from which some people give the name of Palibothri to the race itself, and indeed to the whole tract of country from the Ganges.

-- Pliny the Elder, Natural History 6.65-66. Translated by H. Rackham.[18][19]

Identification

The ancient Greek writers provide vague information about the centre of the Gangaridai power.[3] As a result, the later historians have put forward various theories about its location.

[T]he Gargaridae, who lived upon the Hypanis [Beas River], near Mount Hemodus, and are mentioned by the poet Dionysius.

He styles them from their worship and extraction "the servants of Dionusos." As there was a Caucasus in these parts, so was there also a region named Colchis; 83 [Colchis mentioned by AEthicus, and styled Colche: also by Ptolemy.] which appears to have been a very flourishing and powerful province. It was situated at the bottom of that large isthmus, which lies between the Indus and Ganges: and seems to have comprehended the kingdoms, which are styled Madura, Tranquebar, and Cochin. The Gargaridae, who lived above upon the Hypanis, used to bring down to the Colchians the gold of their country, which they bartered for other commodities. The place, where they principally traded, was the city Comar, or Comarin, at the extremity of the isthmus to the south. The Colchians had here the advantage of a pearl fishery, by which they must have been greatly enriched.

-- A New System, Or, An Analysis of Ancient Mythology: Wherein an Attempt is Made to Divest Tradition of Fable; and to Reduce the Truth to its Original Purity, by Jacob Bryant, 1775

Gangetic plains

Pliny (1st century CE) in his NH, terms the Gangaridai as the novisima gens (nearest people) of the Ganges river. It cannot be determined from his writings whether he means "nearest to the mouth" or "nearest to the headwaters". But the later writer Ptolemy (2nd century CE), in his Geography, explicitly locates the Gangaridai near the mouths of the Ganges.[15]

A. B. Bosworth notes that the ancient Latin writers almost always use the word "Gangaridae" to define the people, and associate them with the Prasii people. According to Megasthenes, who actually lived in India, the Prasii people lived near the Ganges. Besides, Pliny explicitly mentions that the Gangaridae lived beside the Ganges, naming their capital as Pertalis.[/b] All these evidences suggest that the Gangaridae lived in the Gangetic plains.[15]

37. The land of the Indians has also many large navigable rivers which have their sources in the mountains lying to the north and then flow through the level country; and not a few of these unite and empty into the river known as the Ganges. This river, which is thirty stades in width, flows from north to south and empties into the ocean, forming the boundary towards the east of the tribe of the Gandaridae, which possesses the greatest number of elephants and the largest in size. Consequently no foreign king has ever subdued this country, all alien nations being fearful of both the multitude and the strength of the beasts. In fact even Alexander of Macedon, although he had subdued all Asia, refrained from making war upon the Gandaridae alone of all peoples; for when he had arrived at the Ganges river with his entire army, after his conquest of the rest of the Indians, upon learning that the Gandaridae had four thousand elephants equipped for war he gave up his campaign against them.1 [A fuller account of this incident is given in Book 17. 93. But Alexander did not reach the river system of the Ganges, the error being due to a confusion of the Ganges with the Sutlej, a tributary of the Indus; cp. W. W. Tarn, “Alexander and the Ganges,” Journal of Hellenic Studies, 43 (1923), 93 ff.]

-- Diodorus of Siciliy in Twelve Volumes, Volume I, Books II (continued) 35-IV, 58, with an English translation by C.H. Oldfather, Professor of Ancient History and Languages, The University of Nebraska, 1935 (p. 9-13)

Rarh region

Diodorus (1st century BCE) states that the Ganges river formed the eastern boundary of the Gangaridai. Based on Diodorus's writings and the identification of Ganges with Bhāgirathi-Hooghly (a western distributary of Ganges), Gangaridai can be identified with the Rarh region in West Bengal.[3]

Larger part of Bengal

The Rarh is located to the west of the Bhāgirathi-Hooghly (Ganges) river. However, Plutarch (1st century CE), Curtius (possibly 1st century CE) and Solinus (3rd century CE), suggest that Gangaridai was located on the eastern banks of the Gangaridai river.[3] Historian R. C. Majumdar theorized that the earlier historians like Diodorus used the word Ganga for the Padma River (an eastern distributary of Ganges).[3]

Pliny names five mouths of the Ganges river, and states that the Gangaridai occupied the entire region about these mouths. He names five mouths of Ganges as Kambyson, Mega, Kamberikon, Pseudostomon and Antebole. These exact present-day locations of these mouths cannot be determined with certainty because of the changing river courses. According to D. C. Sircar, the region encompassing these mouths appears to be the region lying between the Bhāgirathi-Hooghly River in the west and the Padma River in the east.[12] This suggests that the Gangaridai territory included the coastal region of present-day West Bengal and Bangladesh, up to the Padma river in the east.[20] Gaurishankar De and Subhradip De believe that the five mouths may refer to the Bidyadhari, Jamuna and other branches of Bhāgirathi-Hooghly at the entrance of Bay of Bengal.[21]

According to the archaeologist Dilip Kumar Chakrabarti, the centre of the Gangaridai power was located in vicinity of Adi Ganga (a now dried-up flow of the Hooghly river). Chakrabarti considers Chandraketugarh as the strongest candidate for the centre, followed by Mandirtala.[22] James Wise believed that Kotalipara in present-day Bangladesh was the capital of Gangaridai.[23] Archaeologist Habibullah Pathan identified the Wari-Bateshwar ruins as the Gangaridai territory.[24]

North-western India

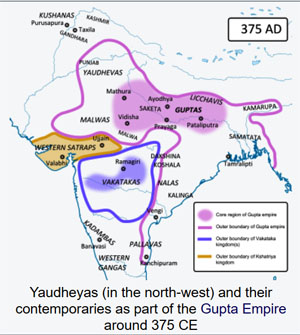

William Woodthorpe Tarn (1948) identifies the "Gandaridae" mentioned by Diodorus with the people of Gandhara.[25] Historian T. R. Robinson (1993) locates the Gangaridai to the immediately east of the Beas River, in the Punjab region. According to him, the unnamed river described in Diodorus' Book 18 is Beas (Hyphasis); Diodorus misinterpreted his source, and incompetently combined it with other material from Megasthenes, erroneously naming the river as Ganges in Book 2.[26] Robinson identified the Gandaridae with the ancient Yaudheyas.[27]

Yaudheyas (in the north-west) and their contemporaries as part of the Gupta Empire around 375 CE

Yaudheya or Yoddheya Gana (Yoddheya Republic) was an ancient militant confederation. The word Yaudheya is a derivative of the word from yodha meaning warriors. They were principally kshatriya renowned for their skills in warfare, as inscribed in the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman by the Indo-Scythian ruler Rudradaman of the Western Satraps. The Yaudheyas emerged in the 5th century BCE and governed independently until being incorporated into the Maurya Empire....The Yaudheya Republic reformed and flourished up to the middle to the 4th century when it was ultimately conquered by Samudragupta and incorporated into the Gupta Empire until being disestablished.

-- Yaudheya, by Wikipedia

A. B. Bosworth (1996) rejects this theory, pointing out that Diodorus describes the unnamed river in Book 18 as the greatest river in the region. But Beas is not the largest river in its region. Even if one excludes the territory captured by Alexander in "the region" (thus excluding the Indus River), the largest river in the region is Chenab (Acesines). Robison argues that Diodorus describes the unnamed river as "the greatest river in its own immediate area", but Bosworth believes that this interpretation is not supported by Diodorus's wording.[28] Bosworth also notes that Yaudheyas were an autonomous confederation, and do not match the ancient descriptions that describe Gandaridae as part of a strong kingdom.[27]

Other

According to Nitish K. Sengupta, it is possible that the term "Gangaridai" refers to the whole of northern India from the Beas River to the western part of Bengal.[3]

Pliny mentions the Gangaridae and the Calingae (Kalinga) together. One interpretation based on this reading suggests that Gangaridae and the Calingae were part of the Kalinga tribe, which spread into the Ganges delta.[29] N. K. Sahu of Utkal University identifies Gangaridae as the northern part of Kalinga.[30]

Political status

Diodorus mentions Gangaridai and Prasii as one nation, naming Xandramas as the king of this nation. Diodorus calls them "two nations under one king."[31] Historian A. B. Bosworth believes that this is a reference to the Nanda dynasty,[32] and the Nanda territory matches the ancient descriptions of kingdom in which the Gangaridae were located.[27]

According to Nitish K. Sengupta, it is possible that Gangaridai and Prasii are actually two different names of the same people, or closely allied people. However, this cannot be said with certainty.[31]

Historian Hemchandra Ray Chowdhury writes: "It may reasonably be inferred from the statements of the Greek and Latin writers that about the time of Alexander's invasion, the Gangaridai were a very powerful nation, and either formed a dual monarchy with the Pasioi [Prasii], or were closely associated with them on equal terms in a common cause against the foreign invader.[33]

References

Citations

1. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 75.

2. Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 171, 215.

3. Nitish K. Sengupta 2011, p. 28.

4. A. B. Bosworth 1996, pp. 188-189.

5. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 188.

6. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 189.

7. Diodorus Siculus (1940). The Library of History of Diodorus Siculus. Loeb Classical Library. II. Translated by Charles Henry Oldfather. Harvard University Press. OCLC 875854910.

8. Diodorus Siculus (1963). The Library of History of Diodorus Siculus. Loeb Classical Library. VIII. Translated by C. Bradford Welles. Harvard University Press. OCLC 473654910.

9. Diodorus Siculus (1947). The Library of History of Diodorus Siculus. Loeb Classical Library. IX. Translated by Russel M. Geer. Harvard University Press. OCLC 781220155.

10. J. W. McCrindle 1877, pp. 33-34.

11. R. C. Majumdar 1982, p. 198.

12. Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 172.

13. Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 171.

14. Wilfred H. Schoff (1912). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea; Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean. Longmans, Green and Co. ISBN 978-1-296-00355-5.

15. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 192.

16. Carlos Parada (1993). Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology. Åström. p. 60. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

17. R. C. Majumdar 1982, pp. 103-128.

18. Pliny (1967). Natural History. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by H. Rackham. Harvard University Press. OCLC 613102012.

19. R. C. Majumdar 1982, p. 341-343.

20. Ranabir Chakravarti 2001, p. 212.

21. Gourishankar De; Shubhradip De (2013). Prasaṅga, pratna-prāntara Candraketugaṛa. Scalāra. ISBN 978-93-82435-00-6.

22. Dilip K. Chakrabarti 2001, p. 154.

23. Jesmin Sultana 2003, p. 125.

24. Enamul Haque 2001, p. 13.

25. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 191.

26. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 190.

27. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 194.

28. A. B. Bosworth 1996, p. 193.

29. Biplab Dasgupta 2005, p. 339.

30. N. K. Sahu 1964, pp. 230-231.

31. Nitish K. Sengupta 2011, pp. 28-29.

32. A. B. Bosworth 1993, p. 132.

33. Chowdhury, The History of Bengal Volume I, p. 44.

Sources

• A. B. Bosworth (1993). Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-1-107-71725-1.

• A. B. Bosworth (1996). Alexander and the East. Clarendon. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-19-158945-4.

• Biplab Dasgupta (2005). European Trade and Colonial Conquest. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-029-7.

• Dilip K. Chakrabarti (2001). Archaeological Geography of the Ganga Plain: The Lower and the Middle Ganga. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-7824-016-9.

• Dineschandra Sircar (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0690-0.

• Enamul Haque (2001). Excavation at Wari-Bateshwar: A Preliminary Study. International Center for Study of Bengal Art. ISBN 978-984-8140-02-4.

• J. W. McCrindle (1877). Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian. London: Trübner & Co.

• Jesmin Sultana (2003). Sirajul Islam; Ahmed A. Jamal (eds.). Banglapedia: Kotalipara. 6. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-32-0581-0.

• N. K. Sahu (1964). History of Orissa from the Earliest Time Up to 500 A.D. Utkal University.

• Nitish K. Sengupta (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

• Carlos Parada (1993). Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology. Åström. p. 60. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

• Ranabir Chakravarti (2001). Trade in Early India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564795-2.

• R. C. Majumdar (1982). The Classical Accounts of India, Greek and Roman. South Asia Books. ISBN 978-0-8364-0858-4.

• Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson PLC, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9