Problems of Violence, States of Terror

by Anupama Rao

Economic and Political Weekly

Vol. 36, No. 43, pp. 4125-4133 (9 pages)

Oct. 27 - Nov. 2, 2001

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The impact of colonialism also evidenced itself in the attempts to establish a codified system of criminal law that differentiated and separated itself from the 'native' law that preceded it. Despite such attempts, native practices had their own uses in enforcing discipline as seen in the incidents that unfold in the 'Nassick Torture Case' and elaborated further in this paper. The paper also probes issues related to fear and suffering while also enunciating the social scientists' dilemma of needing to represent and reproduce violence without fetishising or merely re-enacting it.

The task of a critique of violence can be summarised as that of expounding its relation to law and justice [Benjamin 1978:276].

This essay considers the ambivalent and uncertain relationship between law and violence, law's violence, in fact. Through a symptomatic (and at present suggestive) reading of a case of torture that took place near the town of Hashik in 1854, I explore the larger issue of the ethics of punishment and bodily violation, the historical emergence of discourses of bodily pain and suffering, and the relationship between the homogenisation of criminal law and the stigmatisation of 'native' practices of punishment. I suggest that colonial law was undergirded by a set of racialised assumptions about native susceptibility to corporal punishment; assumptions that produced their own paradoxical results in attempts to reform native practice, while simultaneously overdetermining them as both backward and barbaric. While this paper engages with the impossible attempts to distinguish law from violence in the history of colonial law, I am equally interested in the possibility of reconstructing the experience of 'dying in custody'. Exploring the representational limit of archival sources in describing emotive states such as fear or suffering, as well as the historian's desires to reproduce them in the interest of either imagination or critique, this paper asks how we might represent violence without fetishising or re-enacting it.

The 'Nassick Torture Case'

In a file labelled 'Nassick Torture Case' in the Maharashtra State Archives, one can find a petition dated October 17, 1855 to governor-general M. Elphinstone signed by 1,989 inhabitants of the town of Nashik.1 The petition seeks the reinstatement of one Mohammed Sheikh, joint police officer, or 'foujdar':

We at present learn from the newspaper that the government has dismissed him (the foujdar) from his situation, and on inquiry found that last year a Coonbee had murdered his niece for her ornaments, and was apprehended by the police peons, who put a stick up his anus for extorting confession, and that the government has decided that the foujdar had ordered to do this to the above Coonbee who died while in custody -- but we feel certain that the foujdar could not have ordered to the above effect because in the deceased prisoner's deposition which was taken down before the government authorities, no mention is made about the foujdar's orders, nor did the police peons who were tried and punished say anything in their depositions concerning the foujdar's orders for putting a stick up the prisoner's anus or for doing such other evil action...

In the absence of any positive proof of the foujdar's innocence, the petitioners are ironically forced to rely on his alleged victim's dying declaration. Reading this petition today, one is tempted to accuse the petitioners of distorting the significance of the victim's last words: they take an omission as a positive indicator, and thus fabricate a version of events that seems to suppress the truth of torture. But the story at stake here cannot be so easily judged. For as I will discuss here, the truth of torture lies not simply in its opposition to the torturer's version of events, but rather, in a more complex matrix that situates the foujdar and his defenders themselves within a regime of violence. To unravel the relationship between the tortured body and the silence surrounding the practice of torture, it is necessary to real the relationship between torture and colonial law. My study aims to acknowledge the ways in which colonial law not only participated in a regime of torture but also sought to erase its own complicity in this regime.

The complexity of the relationship between colonial rule, native police, and violence emerges in the facts and documents that surround the death of the Coonbee. A young man of about 19 years, named Gunnoo, is mentioned in this petition only by his caste label, Coonbee, or 'kunbi,' a broad and inclusive category of agriculturalists.2 The significance of caste and class relations alluded to here is drawn out by the surrounding facts of the case. The chain of events began when Gunnoo was accused of taking the ornaments of his niece Syee, a young girl of five years, and then drowning her in a well. One witness's deposition testified that Gunnoo denied knowing the girl's wherabouts. However, when police peons 'gave him a slap on the turban, a silver suklee (chain) fell out -- on searching him other ornaments were found.' According to the witness, when asked about the girl again, Gunnoo pleaded that the ornaments must have been planted on him, and repeated that he did not know Syee's whereabouts. At this point in the public interrogation, the foujdar is said to have suggested that 'he (Gunnoo) is frightened in this crowd take him to one side and 'sumjao' him (make him understand.'3 Gunnoo was then taken into the cowshed of a prostitute, Lateeb, and tortured. Afterwards, he was led to the well outside the town in which the girl's body was found. There, Gunnoo confessed to the crime. He died in custody two days later, on August 13, 1854.

It is in the legal aftermath of Gunnoo's death that the particular relationship of torture to colonial rule was at stake. For although a significant body of literature maintains that cultures of terror were essential to the task of colonial governance, British rule in India also sought to oppose, at least on one level, police violence.4 Thus Gunnoo's death in custody prompted a judicial inquiry that set colonial administrators against the native police. These efforts on the part of colonial law to distance itself from, and even to condemn, excessive violence participated in a larger attempt to fashion colonial rule as a liberal 'rule of law.'

Gunnoo's death in custody and allegations of police torture, however, put the Bombay government in a difficult position. The simultaneous discovery of and efforts to contain the practice of torture produced a political contradiction. Even as they publicly investigated the charge of torture by the police, colonial administrators were animated by an anxiety about the prevalence of torture (what if it facilitated all policing?), and by a consequent reluctance to draw public attention to its practice. Although meant to exhibit the fair and efficient functioning of colonial institutions, the inquiry, therefore sought to characterise Gunnoo's death as an extraordinary event. Only a discursive separation of torture from legitimate forms of punishment would allow colonial administrators to punish the policemen guilty of torture while maintaining a commitment to the beneficent face of the colonial regime.

Gunnoo's death can serve, then, as a point of entry into a larger set of debates about the reform of penal practices during the mid-19th century. When the critical historian reads the developmental narrative of colonial law against the grain, it becomes possible to resituate the category of torture within the development of the colonial judicial-penal complex and, consequently, the narrative of colonial modernity. I show how the containment of torture by colonial authorities worked through its own self-contradiction by fashioning itself as an instrument of 'modern' legal and forensic knowledge. This liberal modernity, however, was fashioned only by positing colonial subjects as unaware of the distinction between punishment and retribution.

In what follows, I focus on this process as it becomes visible in two areas: (i) in the indictment of 'native' practices of policing as perpetuating the practice of torture. Colonial administrators distanced themselves from such practices, arguing that they illustrated the persistence of precolonial disciplinary practices. The public exposure of torture, which should have implicated the colonial state and its excesses, was in fact converted to a moral victory over a penal regime now characterised as traditional, and barbaric and (ii) in the significance of new methods of detection such as forensic medicine in overturning native practices of torture. During the latter half of the 19th century, colonial officials in Bombay and London increasingly came to focus on the perceived benefits of the nascent field of medical jurisprudence in detecting not only crime, but also the excessive use of force by the police in extracting confessions.5 Torture's crude violation of the body gave way to more rational and objective forms of discovering the truth of violence. New discourses of detection and physical examination became critical for the elaboration of a colonial judicial-penal complex that objectified the body in terms of its pain and suffering.

Colonial Governance and Native Police

In the investigation into Gunnoo's death, the structural relationship between colonial governance, police practices, and violence to native bodies is exhibited by the colonial state's attempts to brand as scapegoats the actual perpetrators of police torture; the native police. The Bombay government faced the dilemma of balancing the validity of the evidence gathered at the well regarding Gunnoo's murder of his niece, against the possibility that the confession had been extracted through torture, rendering it invalid or highly compromised at best. On one hand, the police were seen as belonging to the generic category of state servants and functionaries of the law, while on the other, the 'native' police were viewed as a special category of colonial subjects who were outside the law.

This tension is revealed in the legal documents that circulated after the sessions court sentenced the six police peons who were accused of committing the torture and murder of Gunnoo to four years hard labour, four months in solitary confinement, and the first seven and last seven days of the month on a 'conjee' diet (rice water or gruel).6 The court described the acts of these six men as 'atrocious' and truly outside the bounds of law. These crimes were therefore treated as renegade acts committed without the authority of a superior. For this reason, the foujdar himself was not named as a defendant in the case. Indeed, in arguments later made in defence of the foujdar, it was maintained that such an act, committed 'in great haste,' a 'desperate measure' of 'cruelty' done in a 'clumsy manner,' could not have been premeditated and could not therefore have taken place under the orders of a government official.7 This was buttressed by the eyewitness testimony of Alexander Bell, assistant superintendent of police, who had testified that Gunnoo had appeared in perfect health when he had seen him at the well immediately after the alleged torture.

However, further inquiry by the high court called the foujdar's innocence into doubt. A resolution from the governor in council to the registrar of the Sudder Adalut on August 30, 1855 argued that the native police had been let off too lightly; that 'the punishment is far too light to operate as a warning to the police subordinates in Nassick and throughout the presidency.' Furthermore, the letter noted that, while ignoring the foujdar's participation in extorting a confession, the sessions court marked its knowledge of the use of torture in this case by noting that '... when the Foujdar ordered the unfortunate prisoner to be taken aside he intended that a confession should be retracted from him by threats and ill-usages.' The judiciary 'knew' the settings of torture, its performance in secret, much as it attempted to ignore the initiation of the event at the behest of the foujdar. In the name of the just rule of law, the Sudder Foujdari Adalat (Supreme Criminal Court) thus initiated a case against the foujdar, arguing that 'It is not fitting the subject and active agents in this crime should be punished while their superior is held blameless because he took care to keep out of sight himself of the outrage perpetrated.'8

The possibility that the murder of Gunnoo was not simply the act of renegade police peons but perhaps a deliberately ordered, official act, moved this case onto a larger stage. For if Gunnoo's death was now not an aberration but a more general police practice, it would be necessary to conduct an inquiry into this practice on the highest levels. Thus in response to a letter dated July 20, 1855 from Elphinstone, the governor-general of Bombay presidency, the Sudder Foujdari Adalat replied that they thought the law to be sufficient in handling cases of police abuse as well as extraction in the pursuit of revenue collection.9 Reforming individual practices gave way to an inquiry into the hierarchies of command within the police, and attempts to discipline superiors who might have ordered the torture while not having actually performed it. At this point, the reform of the police as an institution confronted their relationship to the law.

It has been argued that the British imposed a rule of law in colonial India by maintaining that precolonial regimes lacked a properly autonomous domain of law, relying instead on law-like structures and modalities of caste and community-based adjudication [Gune 1953; Singha 1998]. An autonomous domain of law was also to be a homogenising one, buttressed by a large-scale ideological shift in native mentalities. Natives had to be taught to do away with categories of difference such as caste, gender, and religion that assumed that different categories of persons were inherently unequal, entitled to different forms and severity of punishment. In fact, however, the colonial state both relied on and worked through such distinctions.10

The imposition of a homogenous system of criminal law also demanded a cadre of police who would involve themselves in the pursuit of criminals, extract confessions and produce testimony, and work closely with the judiciary in punishing criminal offenders while protecting the populace.11 Because colonial officers mistrusted the native police, and considered their reliance on them a necessary evil, the native police force had to be drastically reformed and modernised if it was to implement the legal reforms contemplated by the British government.

As early as 1832, the Select Committee on East India Affairs (judicial) had discussed the prevalence of torture, and suggested that the police force had to be reformed and modernised in order to curtail the use of corporal violence.12 In response to a query from the committee -- 'Are you aware whether the practice of torture by the native officers, for the purpose of extorting confessions or obtaining evidence, has been frequently resorted to?' -- Alexander Campbell, ex-registrar of the Sudder Diwani and Faujdari Adalt (Supreme Civil and Criminal Court, respectively) in Madras replied:

Under the native governments which preceded us at Madras, the universal object of every police officer was to obtain a confession from the prisoner with a view to his conviction of any offence; and notwithstanding every endeavour of our European tribunals to put an end to this system, frequent instances have come before all our criminal tribunals of its use.13

Campbell went on to note that policemen above the rank of common peon often functioned as witnesses to crimes, which literally allowed the police to take the law into their own hands. In 1857, a member of the house of commons noted the popular conviction that 'dacoity is bad enough, but that the subsequent police inquiry is worse.'14 This had much to do with the fact that confessions in the presence of the police were seen as adequate for judicial indictment. Magistrates with a poor command over native languages were often unfamiliar with the customary and/or religious codes that regulated persons and communities. They found themselves relying on confessions taken by the police rather than conducting their own inquiries. This suggests that the police often acted in a de facto judicial capacity, taking confessions, deciding guilt, and punishing wrongdoers. This exposed the uncertain position of the police in the implementation of law: were they merely law's functionaries, or were they in fact producing the evidence that law courts relied upon in the dispensation of justice?15

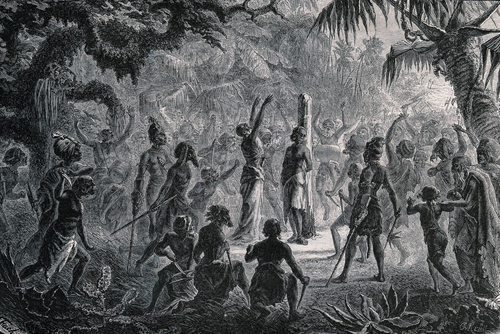

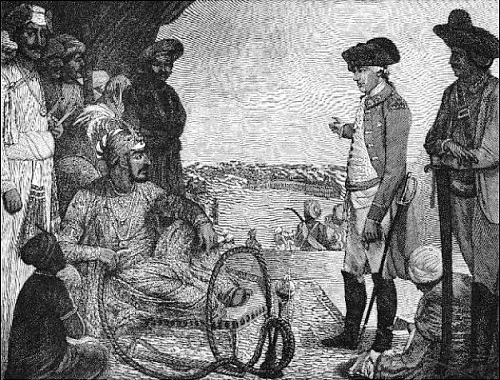

The continuity between the supposed prevalence of torture in traditional repertoires of policing and their use under a colonial regime also suggested the colonial state's pedagogical failure in marking a clear separation between the rule of law and corporal punishment. In 1857 officials were still arguing that '... there was a deficiency in the police and in the administration of justice in India.'16 Interestingly, police reform and attempts to discontinue the use of excessive corporal violence were situated on a continuum with the abolition of other 'horrible practices' such as hookswinging, infanticide, and Meriah (human) sacrifice, all 'cruelties which disgraced society in India.'17

Human sacrifice among the Khonds in India: a victim (meriah) about to be dismembered. Wood engraving by C. Krull after Fuchs, 18--. [between 1800 and 1899]

Among the Lhota Naga, one of the many savage tribes who inhabit the deep rugged labyrinthine glens which wind into the mountains from the rich valley of Brahmapootra, it used to be a common custom to chop off the heads, hands, and feet of people they met with, and then to stick up the severed extremities in their fields to ensure a good crop of grain. They bore no ill-will whatever to the persons upon whom they operated in this unceremonious fashion. Once they flayed a boy alive, carved him in pieces, and distributed the flesh among all the villagers, who put it into their corn-bins to avert bad luck and ensure plentiful crops of grain. The Gonds of India, a Dravidian race, kidnapped Brahman boys, and kept them as victims to be sacrificed on various occasions. At sowing and reaping, after a triumphal procession, one of the lads was slain by being punctured with a poisoned arrow. His blood was then sprinkled over the ploughed field or the ripe crop, and his flesh was devoured. The Oraons or Uraons of Chota Nagpur worship a goddess called Anna Kuari, who can give good crops and make a man rich, but to induce her to do so it is necessary to offer human sacrifices. In spite of the vigilance of the British Government these sacrifices are said to be still secretly perpetrated. The victims are poor waifs and strays whose disappearance attracts no notice. April and May are the months when the catchpoles are out on the prowl. At that time strangers will not go about the country alone, and parents will not let their children enter the jungle or herd the cattle. When a catchpole has found a victim, he cuts his throat and carries away the upper part of the ring finger and the nose. The goddess takes up her abode in the house of any man who has offered her a sacrifice, and from that time his fields yield a double harvest. The form she assumes in the house is that of a small child. When the householder brings in his unhusked rice, he takes the goddess and rolls her over the heap to double its size. But she soon grows restless and can only be pacified with the blood of fresh human victims.

But the best known case of human sacrifices, systematically offered to ensure good crops, is supplied by the Khonds or Kandhs, another Dravidian race in Bengal. Our knowledge of them is derived from the accounts written by British officers who, about the middle of the nineteenth century, were engaged in putting them down. The sacrifices were offered to the Earth Goddess. Tari Pennu or Bera Pennu, and were believed to ensure good crops and immunity from all disease and accidents. In particular, they were considered necessary in the cultivation of turmeric, the Khonds arguing that the turmeric could not have a deep red colour without the shedding of blood. The victim or Meriah, as he was called, was acceptable to the goddess only if he had been purchased, or had been born a victim—that is, the son of a victim father, or had been devoted as a child by his father or guardian. Khonds in distress often sold their children for victims, “considering the beatification of their souls certain, and their death, for the benefit of mankind, the most honourable possible.” A man of the Panua tribe was once seen to load a Khond with curses, and finally to spit in his face, because the Khond had sold for a victim his own child, whom the Panua had wished to marry. A party of Khonds, who saw this, immediately pressed forward to comfort the seller of his child, saying, “Your child has died that all the world may live, and the Earth Goddess herself will wipe that spittle from your face.” The victims were often kept for years before they were sacrificed. Being regarded as consecrated beings, they were treated with extreme affection, mingled with deference, and were welcomed wherever they went. A Meriah youth, on attaining maturity, was generally given a wife, who was herself usually a Meriah or victim; and with her he received a portion of land and farm-stock. Their offspring were also victims. Human sacrifices were offered to the Earth Goddess by tribes, branches of tribes, or villages, both at periodical festivals and on extraordinary occasions. The periodical sacrifices were generally so arranged by tribes and divisions of tribes that each head of a family was enabled, at least once a year, to procure a shred of flesh for his fields, generally about the time when his chief crop was laid down.

The mode of performing these tribal sacrifices was as follows. Ten or twelve days before the sacrifice, the victim was devoted by cutting off his hair, which, until then, had been kept unshorn. Crowds of men and women assembled to witness the sacrifice; none might be excluded, since the sacrifice was declared to be for all mankind. It was preceded by several days of wild revelry and gross debauchery. On the day before the sacrifice the victim, dressed in a new garment, was led forth from the village in solemn procession, with music and dancing, to the Meriah grove, a clump of high forest trees standing a little way from the village and untouched by the axe. There they tied him to a post, which was sometimes placed between two plants of the sankissar shrub. He was then anointed with oil, ghee, and turmeric, and adorned with flowers; and “a species of reverence, which it is not easy to distinguish from adoration,” was paid to him throughout the day. A great struggle now arose to obtain the smallest relic from his person; a particle of the turmeric paste with which he was smeared, or a drop of his spittle, was esteemed of sovereign virtue, especially by the women. The crowd danced round the post to music, and addressing the earth, said, “O God, we offer this sacrifice to you; give us good crops, seasons, and health”; then speaking to the victim they said, “We bought you with a price, and did not seize you; now we sacrifice you according to custom, and no sin rests with us.”

On the last morning the orgies, which had been scarcely interrupted during the night, were resumed, and continued till noon, when they ceased, and the assembly proceeded to consummate the sacrifice. The victim was again anointed with oil, and each person touched the anointed part, and wiped the oil on his own head. In some places they took the victim in procession round the village, from door to door, where some plucked hair from his head, and others begged for a drop of his spittle, with which they anointed their heads. As the victim might not be bound nor make any show of resistance, the bones of his arms and, if necessary, his legs were broken; but often this precaution was rendered unnecessary by stupefying him with opium. The mode of putting him to death varied in different places. One of the commonest modes seems to have been strangulation, or squeezing to death. The branch of a green tree was cleft several feet down the middle; the victim’s neck (in other places, his chest) was inserted in the cleft, which the priest, aided by his assistants, strove with all his force to close. Then he wounded the victim slightly with his axe, whereupon the crowd rushed at the wretch and hewed the flesh from the bones, leaving the head and bowels untouched. Sometimes he was cut up alive. In Chinna Kimedy he was dragged along the fields, surrounded by the crowd, who, avoiding his head and intestines, hacked the flesh from his body with their knives till he died. Another very common mode of sacrifice in the same district was to fasten the victim to the proboscis of a wooden elephant, which revolved on a stout post, and, as it whirled round, the crowd cut the flesh from the victim while life remained. In some villages Major Campbell found as many as fourteen of these wooden elephants, which had been used at sacrifices. In one district the victim was put to death slowly by fire. A low stage was formed, sloping on either side like a roof; upon it they laid the victim, his limbs wound round with cords to confine his struggles. Fires were then lighted and hot brands applied, to make him roll up and down the slopes of the stage as long as possible; for the more tears he shed the more abundant would be the supply of rain. Next day the body was cut to pieces.

The flesh cut from the victim was instantly taken home by the persons who had been deputed by each village to bring it. To secure its rapid arrival, it was sometimes forwarded by relays of men, and conveyed with postal fleetness fifty or sixty miles. In each village all who stayed at home fasted rigidly until the flesh arrived. The bearer deposited it in the place of public assembly, where it was received by the priest and the heads of families. The priest divided it into two portions, one of which he offered to the Earth Goddess by burying it in a hole in the ground with his back turned, and without looking. Then each man added a little earth to bury it, and the priest poured water on the spot from a hill gourd. The other portion of flesh he divided into as many shares as there were heads of houses present. Each head of a house rolled his shred of flesh in leaves, and buried it in his favourite field, placing it in the earth behind his back without looking. In some places each man carried his portion of flesh to the stream which watered his fields, and there hung it on a pole. For three days thereafter no house was swept; and, in one district, strict silence was observed, no fire might be given out, no wood cut, and no strangers received. The remains of the human victim (namely, the head, bowels, and bones) were watched by strong parties the night after the sacrifice; and next morning they were burned, along with a whole sheep, on a funeral pile. The ashes were scattered over the fields, laid as paste over the houses and granaries, or mixed with the new corn to preserve it from insects. Sometimes, however, the head and bones were buried, not burnt. After the suppression of the human sacrifices, inferior victims were substituted in some places; for instance, in the capital of Chinna Kimedy a goat took the place of the human victim. Others sacrifice a buffalo. They tie it to a wooden post in a sacred grove, dance wildly round it with brandished knives, then, falling on the living animal, hack it to shreds and tatters in a few minutes, fighting and struggling with each other for every particle of flesh. As soon as a man has secured a piece he makes off with it at full speed to bury it in his fields, according to ancient custom, before the sun has set, and as some of them have far to go they must run very fast. All the women throw clods of earth at the rapidly retreating figures of the men, some of them taking very good aim. Soon the sacred grove, so lately a scene of tumult, is silent and deserted except for a few people who remain to guard all that is left of the buffalo, to wit, the head, the bones, and the stomach, which are burned with ceremony at the foot of the stake.

In these Khond sacrifices the Meriahs are represented by our authorities as victims offered to propitiate the Earth Goddess. But from the treatment of the victims both before and after death it appears that the custom cannot be explained as merely a propitiatory sacrifice. A part of the flesh certainly was offered to the Earth Goddess, but the rest was buried by each householder in his fields, and the ashes of the other parts of the body were scattered over the fields, laid as paste on the granaries, or mixed with the new corn. These latter customs imply that to the body of the Meriah there was ascribed a direct or intrinsic power of making the crops to grow, quite independent of the indirect efficacy which it might have as an offering to secure the good-will of the deity. In other words, the flesh and ashes of the victim were believed to be endowed with a magical or physical power of fertilising the land. The same intrinsic power was ascribed to the blood and tears of the Meriah, his blood causing the redness of the turmeric and his tears producing rain; for it can hardly be doubted that, originally at least, the tears were supposed to bring down the rain, not merely to prognosticate it. Similarly the custom of pouring water on the buried flesh of the Meriah was no doubt a rain-charm. Again, magical power as an attribute of the Meriah appears in the sovereign virtue believed to reside in anything that came from his person, as his hair or spittle. The ascription of such power to the Meriah indicates that he was much more than a mere man sacrificed to propitiate a deity. Once more, the extreme reverence paid him points to the same conclusion. Major Campbell speaks of the Meriah as “being regarded as something more than mortal,” and Major Macpherson says, “A species of reverence, which it is not easy to distinguish from adoration, is paid to him.” In short, the Meriah seems to have been regarded as divine. As such, he may originally have represented the Earth Goddess or, perhaps, a deity of vegetation; though in later times he came to be regarded rather as a victim offered to a deity than as himself an incarnate god. This later view of the Meriah as a victim rather than a divinity may perhaps have received undue emphasis from the European writers who have described the Khond religion. Habituated to the later idea of sacrifice as an offering made to a god for the purpose of conciliating his favour, European observers are apt to interpret all religious slaughter in this sense, and to suppose that wherever such slaughter takes place, there must necessarily be a deity to whom the carnage is believed by the slayers to be acceptable. Thus their preconceived ideas may unconsciously colour and warp their descriptions of savage rites.

-- The Golden Bough: A study of magic and religion, by Sir James George Frazer

The problems of judicial administration could therefore be linked to native intransigence rather than the failures of colonial governance. Once again, it was the presence of native policemen, rather than the role of the police in a colonial regime, that came to be problematised. By placing police torture alongside a stream of indistinguishable acts of barbarity and violence of varying motivations, British officials confirmed to themselves that the native police were inured to the use of corporal violence in extracting confessions. The police were understood as a cultural institution compromised by the fact of being 'native', and hence fundamentally irrational and prone to excess.

The publication of the two-volume Report of the Commissioners for the Investigation of the Alleged Cases of Torture in the Madras Presidency in 1855, (henceforth the Report) drew attention to torture as a structural problem of policing, rather than an aberrant and extraordinary instance.18 The Report was initially meant to explore complaints about torture in the extraction of revenue in Madras presidency. The government of India extended the scope of the report to include the relationship between torture and policing.19 This itself is instructive of the dissonant relationship between attempts to extract revenue at all cost, (revenue demands rose at least threefold during the first few years of settlement in Madras) and the attempt to impose an equitable judicial system on native subjects.

The Company tried to eliminate the existing traders and brokers connected with the cloth trade, and establish more direct control over the weaver. For this purpose they appointed paid servants called gomasthas, who would obtain goods from local weavers and fix their prices. The prices fixed were 15 per cent lower than market price and in extreme cases, even 40 per cent lower than the market price. They would also supervise weavers, collect supplies, and examine the quality of cloth. They also prevented Company weavers from dealing with other buyers.

The Company’s agents who had the right to enforce contracts could well use the same coercive power to extort rents from the weavers. Such opportunism seems to have been common even late into the textile venture. In case weavers refused signing contracts they were subjected to torture and even awarded imprisonment. In this way the gomastas were useful in obtaining goods at a low price for the Company which made huge profits from their exports.

The Company's Board of Trade records from 1793, 1815, and 1818, state that "as a rule the Company’s gomastas and other inferior servants extracted perquisites from the weavers, and not infrequently they were whipped or beaten with rattans [canes]." There were various kinds of "perquisites." One such was an extra charge: this might be a commission (dasturi), tribute (salami), or simply "expenses" (kharcha). Another was a deduction of a portion of the capital advance. Yet another was using debased currency to pay the weaver. The gomastha and his appraisers, sometimes in collusion with Company officials, would falsely appraise cloth quality. They would charge the Company for High Quality, but pay the weaver for low quality. The gomastas' profound knowledge about a particular area and their negotiating ability with local smaller merchants would be indispensable to firms.

-- Gomastha, by Wikipedia

Though there was no comparable investigation in the Bombay presidency, the Report (which was after all a response to massive complaints about torture by natives) sensitised the bureaucracy to the power of a category such as torture that could potentially indict colonial penal practices.20 Hence the anxiety about containing torture travelled across presidencies. This is reflected, for instance, in the production of three separate judicial files on 'Torture' that can be found in the Maharashtra State Archive (MSA) in Bombay confined to the period 1855-1857, coeval with the period when the Report was released, and a general discussion of reforming the police force was also underway. The Report was as much an attempt to bureaucratise the police force and to press for the reform of criminal law, as it was an attempt to publicise the complaints about torture. In this, perhaps, it reflected the colonial conditions of its production, since discourses of improvement masked the attempts to impose more coercive forms of rule over citizen-subjects [Guha 1988].

The reliance on the native police coupled with the constant suspicion that they were ignorant or even abusive of legal norms produced the paradoxical need to 'police the police' [Arnold 1986]. In a colonial situation, natives were seen as possibly needing protection from the police, rather than being protected by them. The construction of the native police as fundamentally unreliable (because racially inferior) thus produced a problem of surveillance and control within the police force. While legal reform was pursued in tandem with the reconceptualisation of personhood and property under colonial rule, the problems with police reform suggested a split between the rhetoric of colonial improvement and its personification in the native police who were meant to enact the ideologies of rule by law. The discovery of torture represented this split in spectacular fashion, by displacing the question of colonial culpability for perpetuating the practice onto precolonial or traditional practices of policing.

The problematic discovery of torture for the extraction of confessions is symptomatic of the contradictions of a colonial rule that acknowledged customary practices (due to the political necessity of relying on natives), yet stigmatised them through the rhetorics of modernisation and improvement. While torture implicated police excess, it also produced 'false' truths, false because contaminated by their connection with corporal violence. Confessions produced under torture were understood to be worthless, since they were produced by the threat of force or even death. In this Gunnoo's case this would raise the dilemma of how far the administration could believe the admission of his guilt in drowning Syee. This raised the spectre of colonial power as merely theatrical and self-confirming, despotic rather than reasonable.

Racial assumptions about native inferiority produced a severe and intractable problem: was it impossible to maintain legitimate practices of punishment that did not run the risk of transmogrifying into the exercise of excessive force and violence in a colonial situation? The colonial state often understood itself as struggling to institute a neutral and rational 'rule of law' in a situation where ruling over the racially inferior and culturally backward often demanded the imposition of forms of physical and symbolic violence. Hence assumptions of native incompetence and barbarity were self-fulfilling prophecies that necessarily depended on colonial authorities' discovery of scandals such as the prevalence of torture practised by native police. The repeated attempts to distinguish between moderate and excessive violence become doubly significant in this context.

Colonial rule was represented as inaugurating a new relationship between the subjects and subjectifying practices. Colonial governmentality had much to do with instituting a new practice of power that could be clearly distinguished from its precolonial predecessors [Fukazawa 1991; Guha 1995; Kadam 1988]. Yet the repeated 'discovery' of torture hinted at the fundamental instability of the rule of law, and suggested that excessive force supplemented the consolidation of the legal sphere as an autonomous domain. As with Gunnoo's torture, the eagerness to produce a confession and punish him for the brutal murder of a young girl took the form of his extra-legal torture by the police. This contradiction exposed the colonial state's fundamental misrecognition of its own role in both producing and disavowing scandalous practices; in recognising the extent to which a 'new' relationship between the state and its subjects as well as among subjects had itself reorganised the relationship between law and society, between adjudication and excess. The violence at the very heart of colonial governance raises for us the possibility of understanding law as constantly haunted by its other face: naked force and violence [Benjamin 1978; Fanon 1986].

The Secret Life of Torture

Along with attempts to reform the native police, a language of bodily integrity and vulnerability became central to judicial discourses that sought to address torture's disregard for the body. If torture assumed the body as a biological fact or datum to be dismembered in order to produce a confession, the colonial judicial regime seems to have operated with another notion of the body, as one eminently available to certain forms of expert knowledge such as forensic medicine. This produced a shift in techniques for the production of truth that integrated scientific discourses of the body with changed conceptions of legal proof and criminal culpability. The affective discourse of pain and suffering animated the discussion of torture as a barbaric and uncivilised practice. I now turn to these issues that appear in the Nashik torture case under the broad rubric of medical testimony.

In Gunnoo's case, the credibility of torture came to rest on the bodily signs that could provide evidence capable of convicting the policemen of wrongdoing. Gunnoo's case was decided on December 26, 1854 by the sessions judge J.W. Woodstock, in Ahmednuggary (Ahmednagar) who acquitted the six accused policemen.21 But this decision was appealed on the grounds that the medical evidence provided before the court was faulty -- that the judge had relied on the questionable claim that Gunnoo had died due to the exacerbation of a prior condition, i.e. piles.22

Colonial officials and upper-level officers of the judiciary in Bombay suggested that part of the problem with this case was the insufficient medical knowledge available to the medical officer when he had first met Gunnoo in prison, as well as the failure of the post-mortem to reveal torture or the excessive use of force with any certainty. The medical evidence was adduced to be of a 'defective character' according to a letter submitted to the Medical Board by the Governor in Council on August 30, 1855, after the Sudder Foujdari Adalat decision.23 Debates about medical evidence had become critical to the indictment of the police. But they also indexed a new relationship between the body as the primary source of knowledge about police misdemeanour, and the problematic speech of the tortured victim who refused to reveal his experiences due to the fear of further violence. Ironically, this stood in opposition to the assumptions by the police that violence to the body produced a more trustworthy confession than verbal interrogation.

Gunnoo's dying declaration before Turquand, joint acting magistrate, and the civil surgeon Pelly, indicted the police for having shoved a stick up his anus in a cowshed.24 But this indictment occurred when it was too late to be of any use, after Gunnoo had been seen by a native doctor as well as a British doctor, who were aware of the pain he was in, but not its origin. This was in large part because Gunnoo had been unwilling to recount his experience in the cowshed, from either shame and humiliation, or fear of further violence in police custody. On the other hand, the common knowledge of beatings by the police and of threats of torture in extracting confessions emerges at various points in the file on this case, indicating that the practice of torture was thus situated between the testimony of witnesses, and the hesitation of expert medical testimony in pronouncing that torture was the 'real' cause of Gunnoo's death. While the doctors resisted from pronouncing on torture, performing violence upon Gunnoo's truth, eyewitnesses were both necessary yet insufficient in testifying to the existence of torture as a medically quantifiable fact.

Bala Bhow, the first hospital assistant, said that when the deceased had complained of pain in his stomach he 'asked him if he had been beaten -- replied he had not -- each day deceased complained of greater pain in his stomach,' and that he (Gunnoo) had finally admitted to having been tortured by the six policemen. Bala Bhow noted that 'deceased had in one of his stools passed two ounces of pure blood unmixed with feces-blood dark and thickened.'

The Civil Surgeon Pelly deposed that:

the deceased was brought to the hospital on the 12th of August and was when we saw him suffering from great pain in the abdomen which increased by the touch of the hand and from other symptoms of acute enteritis that Gunnoo complained to him of having been kicked and beaten by the police but mentioned no names -- Had no recollection of Gunnoo's saying anything that day about a stick having been thrust up his anus. But on the Sunday morning being much worse he made a deposition to Turquand the acting joint magistrate in his (unreadable) presence accusing the police of having done so -- Gunnoo died at two o'clock the same afternoon (my emphasis).

In the prison where Gunnoo had been kept before being taken to hospital on August 12, Imam Wallud Gottee, a sweeper, deposed to having washed the dhotur (the long cloth used to wrap the lower half of the body) which had stains of dried blood upon it. Ahmed Wallud Dawood remembered '... having cleaned a pan of a prisoner confined in the Foujdar's Cutcherry (courthouse) on a charge of murder. (He said he) saw about a handful of blood in it. There was no excrement.'

Gunnoo's own dying declaration is available to us in its paraphrased version, rather than given verbatim.

(Gunnoo) said that on the day of his apprehension the first six prisoners [the police] had taken him to a cowshed belonging to a prostitute by the name of Lateeb -- shut the door forced him down with his face to the ground which prevented him from being heard and then thrust the handle of a paper or China umbrella 11/2 span up his anus twice or thrice but that he could not see who did it -- That he found his Anus bloody and that the cloth he had on was also stained with blood -- and was washed the following day by a Bhungy (an untouchable who 'traditionally' removes nightsoil) -- That on his way from the cowshed to the foujdar's Cutcherry he was beaten by the police as well as by the villagers who had assembled none of whom however could he recognise (my emphasis).

Gunnoo's dying declaration exposes the torture but he is unable to name his aggressors since he could not seem them lying face down in the cowshed.

The testimony of eyewitnesses also indicated that when the policemen had taken Gunnoo aside, the 'knew' or could imagine why Gunnoo was taken away from the crowd, without actually having witnessed the violence. The medical practitioners, for their part, focused only on visible, external symptoms that indicated the internal damage Gunnoo had suffered, further corroborated by the testimony of the prison sweeper who spoke about the presence of blood in Gunnoo's stools. This testimony was also tallied with the physical evidence of torture immediately after Gunnoo's apprehension, where eyewitnesses and senior police officials offered their testimony.25

The deposition of witnesses and Gunnoo's dying declaration that he hadn't seen the faces of his aggressors affirmed secrecy as the precondition of torture's efficacy, while revealing the quality of the 'truth' it was capable of producing. Torture's status shuttled between its secret performance, and the means whereby it became visible and public. The above depositions mark such a movement through the reliance on Gunnoo's various injuries as evidence. Between the truth produced by Gunnoo's body (pain and suffering), the veracity of eyewitness accounts, and medical testimony lies the paradoxical logic of torture as simultaneously secret and public.

The sessions court confronted two positions on the torture: that it had occurred, and everyone knew about it, or that Gunnoo had lied. Much of the evidence required measuring the intensity of Gunnoo's wounds, and when they had been inflicted. Witnesses mentioned the pain and suffering on Gunnoo's face. Additionally, as the sessions court argued, the post-mortem should have revealed death due to unnatural causes. Instead, the medical report showed a contradiction in the medical testimony: the medical officer, Pelly, had deposed that Gunnoo's rectum was found unlacerated during the post-mortem while Bala Bhow had given evidence that the anus was 'not usual but extended'.26 This meant that the medical evidence was unclear about whether Gunnoo had suffered from a prior condition such as piles, that might have manifest the same symptoms as his torture. This was offered as the reason why the prisoner had been taken to hospital and treated without any suspicion about his wounds, until he testified to his torture.

Pelly said that Gunnoo had first been brought to him between 7 and 8 a.m. on August 12, when Gunnoo had told him that he had been kicked and beaten by the police. Pelly had ordered him leached and fomented, and the faujdar is said to have recorded his deposition.27 The next morning, Gunnoo was worse, and Pelly, suspecting that his patient might not live long, had gone to get the magistrate Turquand and the assistant superintendent of police, Alexander Bell, who were in the presence of the prisoner when he gave his dying declaration.

Prior to this, on the morning of August 11, the native doctor, Bala Bhow had gone to the cutcherry, having been called on the night of August 10 to inspect the prisoner. The morning of the 11th, Bhow administered a purgative, and the earthen pan containing Gunnoo's bloody stools had been cleaned by the sweeper. Bhow applied leaches to Gunnoo's stomach that night at 7 p.m. when Gunnoo confessed to Bhow that the police had mishandled him. The foujdar had been informed of this, and Bhow claimed that the foujdar went to see Gunnoo that night. Gunnoo had been taken to hospital, were he met civil surgeon Pelly only on the 12th.28

Gunnoo's death on August 13 prompted an inquest. One Gangaram Bhoojaree, a member of the inquest who had seen the body at about 5 p.m. on August 13, and then again at 7 p.m. stated that he hadn't seen any marks of violence on the body, but that Gunnoo's anus was enlarged and his abdomen swollen. He had also seen '3 pieces of intestines which the doctor said were those of the deceased. These were black and in a decomposed state having marks of coagulated blood on them.' Bhoojaree thought that a stick thrust up the anus might have penetrated Gunnoo's abdomen.

When the Puisne judges of the Sudder Foujdari Adalat reconsidered the evidence gathered by the sessions court, they argued that the lower court had been unclear about whether Gunnoo's injuries were 'new' or manifestations of an older complaint of piles. Though Puisne judge M. Larken differed with A. Remington in his views on police culpability, he too argued that the medical evidence had fudged the question of where the injuries were located (rectum, intestine, peritoneum), and how old the injuries might be. W.H. Harrison, The acting Puisne judge, however, seemed to have accepted that Gunnoo was tortured, commenting that '[T]his case should be laid before government with the object of drawing their attention to the conduct of the Nassick Native Police of all grades who are concerned with this inquiry.' The medical testimony drew on ineffable qualities such as pain and suffering, and attempted to quantify them through a discussion of wounds and their severity. As with the investigation into police misconduct however, attempts to get at the truth only revealed the extent to which colonial assumptions about native bodies and mentalities compromised that quest.

Talal Asad (1998) argues that the quantification of pain -- the ability to measure incommensurable acts of suffering by making physical pain a measurable quantity -- effected a significant shift in discourses of both suffering and punishment. Understanding pain as a quantity ('more' or 'less') of undifferentiated physical suffering made it possible to under the experience of violence as something antithetical to the stature of being fully human.29 This helps explain the British focus on police torture as a native practice that disregarded the relationship between crime and its commensurable punishment. An instrumental conception of pain and the imposition of excessive suffering seemed to lie at the root of such 'native' practices of barbarism, and so confirmed the absence of 'law' as such in precolonial Maharashtra. Any infliction of unjustified force was viewed by the British as torture, regardless of its place in a 'larger moral economy' [Asad 1998: 288].

Asad argues that distinctions between ritual forms of inflicting pain on oneself or others and forms of state-sanctioned violence could be collapsed in this model, since pain was assumed to be a transcultural category, singular in its meaning. In British India early campaigns for the abolition 'Thuggee' or dacoity, which was thought to be ritually sanctioned by certain communities, or attempts to prevent hookswinging, self-flagellation and other forms of 'cruelty' that practitioners inflicted on themselves during religious events, were seen to pose the same problem for colonial governance as did the practice of 'sati' or infanticide. This meant that different idioms for legitimating the performance of certain violent or cruel acts were glossed, all in the interest of controlling the victim/patient's pain [Dirks 1997; Mani 1998; Nigam 1990; Singha 1998; Sunder Rajan 1993; Yang 1987]. The inhumanity of excessive violence and attempts to portray it as a culturally sanctioned form of punishment, meant that it increasingly stood in opposition to the rational and rehabilitative project of penal incarceration.30 However, the distinction between 'bad' and 'good' pain, between the kind of pain that was an affront to notions of humanity, on the one hand, and that which was necessarily entailed in the movement out of barbarism or primitivism into modern subjecthood on the other, was understood in a highly interested and motivated fashion in colonial settings.

As with the development of any modern technique for producing or confirming truth, medical jurisprudence was contradictory in its effects.31 On the one hand it was lauded as capable of producing a truth of the body and its interior (wounds, lacerations, injuries) more reliable than verbal testimony in cases involving physical injury. On the other hand, it carried the potential to indict the excesses of policing. The double-edged quality to the development of these technologies must be noted since they both extended and compromised the colonial state's representations of good governance.32