Megasthenes and the Indian Chronology As Based on the Puranas

by K.D. Sethna

Purana VIII

Bulletin of the Purana Department

Ministry of Education

Government of India

1966

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A., 1877

-- Purana VIII, Bulletin of the Purana Department, Ministry of Education, Government of India, 1966

-- Historical Dates From Puranic Sources, by Prof. Narayan Rao

-- Who was Sandrocottus: Samudragupta or Chandragupta Maurya?, The Chronology of Ancient India, Victim of Concoctions and Distortions, by Vedveer Arya

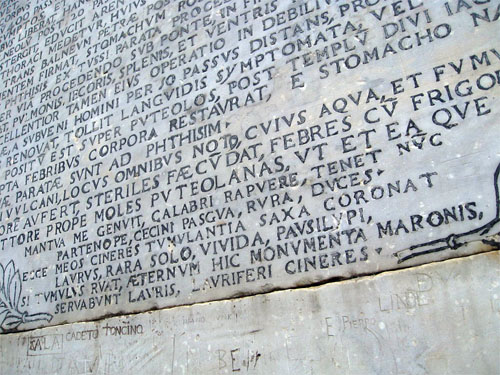

One last point in connection with the puranic king lists ought to be mentioned here. Arrian's Indike (9.9), quoting Megasthenes, states that "from Dionysus to Sandracottus the Indians counted a hundred and fifty-three kings, over six thousand and forty-three years."41 [41 Loeb, tr., E. Iliff Robson, p. 333.] Similarly, in Pliny's Natural History (6.59): "From the time of Father Liber to Alexander the Great 153 kings are counted in a period of 6451 years and three months."42 [42 Loeb, tr. H. Rackem, p. 383.] Classical scholars have wondered about these figures, not to mention the intriguing discrepancy.43 [43 E.g., Pierre CHANTRAINE: Arrien. L'Inde, Paris: Belles Lettres, 21952, p. 35. For a different type of speculation, identifying Sandracottus with Candragupta I Gupta -- rather than Maurya -- who would have been enthroned in 325 or 324 B.C., and on the Indian identity of Father Bacchus, the kind of chronology handed Megasthenes; etc., see K.D. SETHNA: Megasthenes and the Indian Chronology as Based on the puranas, Pur 8, 1966, 9-37, 276-294; 9, 1967, 121-129; 10, 1968, 35-53, 124-147.] More important is the fact that, at least from Megasthenes' time onward, Indians had puranic lists of kings, some of which came to the notice of the foreign visitor.44 [44 Cf. L. ROCHER: The Greek and Latin Data about India. Some Fundamental Considerations, Zakir Husain vol. (1968), 34. Also KANE 1962: 849.]

-- Frederick Eden Pargiter: Excerpt from The Puranas, by Ludo Rocher

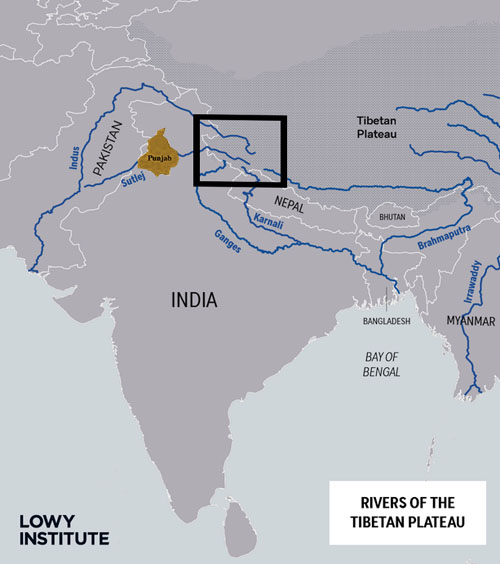

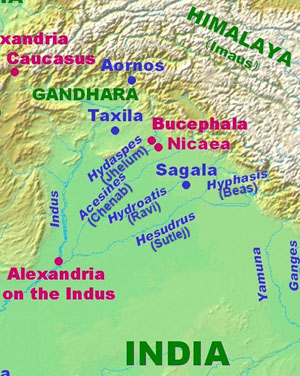

Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador sent by Seleucus Nicator in c. 302 B.C. to the court of the Indian king whom the Greeks called Sandrocottus and whose capital they designated as Palibothra in the country of the Prasii. Scholars have identified the Prasii as the Prachya (Easterners) and Palibothra as Pataliputra and seen the eastern kingdom of Magadha, whose capital was Pataliputra, in the Greek references to the Prasii. The name "Sandrocottus" has been equated with "Chandragupta" and the king who received Megasthenes is said to have been Chandragupta Maurya who, like Sandrocottus, was the founder of a dynasty in Magadha.

The Question of the Two Chandraguptas

The founder of the Mauryas, however, is not the only Chandragupta known to history as a Magadhan emperor and the founder of a dynasty. There is also the first of the Imperial Guptas, Chandragupta I. Modern historians date him to 320 A.D. and set forth many reasons for the identification of Sandrocottns with Chandragupta Maurya. These are claimed to be supported most convincingly by several lines of evidence converging to date Chandragupta Maurya's grandson Asoka to the middle of the 3rd century B.C. But the ancient chronology of India herself, based on the dynastic sections of the Puranas and other indigenous testimonies and traditions, runs counter to this historical vision.

The Puranic account starts with the date 3102 B.C. which it calls the beginning of the Kaliyuga and goes back by 36 years to 3138 B.C. for the Bharata War between the Kuru and the Pandavas as well as for the birth of Parikshit, the grand-nephew of Yudhishthira -- Yudhishthira who ruled at Hastinapura after the Pandava victory in that year down to the Kaliyuga year which was marked by the death of Krishna and the installation by Yadhishthira of Parikshit in his own place so that he and his family might be free to go on a world-pilgrimage. The ancient Indian chronology takes also into account 3177 B.C. This date is connected with what is termed the cycle of Sapta Rishi, the Seven Rishis, the stars of the constellation Great Bear. The Seven Rishis are supposed to make a cycle of 2700 years by a stay of 100 years in each of the 27 Nakshatras or lunar asterisms of the ecliptic. 3177 B.C. marks their entry for a century's stay in the asterism Magha.

The Puranas offer two sets of general calculation. One is concerned with the Sapta Rishi cycle. The Vayu-Purana (99. 423, as well as the Brahmanda Purana,1 [F. I. Pargiter, Purana Texts of the Dynasties of the Kali Age (London, 1913, p. 61, n. 92.] says that the Seven Rishis who were in Magha in the time of Parikshit complete their 24th century in a part of the Andhra (Satavahana) dynasty. This means: when 2400 years had passed after 3177 B.C. the Andhra dynasty had already started. The Brahmanda (III. 74.230) again says that during the same dynasty there is the 27th century and that the asterism Magha, whose guardians are the Pitris (Ancestors), follows once more. A verse of the Matsya Parana1 [ Ibid., p. 59. ] speaks also of the cycle repeating itself after the 27th century and connects the repetition with the same dynasty using an expression which can be translated either as "at the end of the Andhras" or as "in the end..." The second rendering would be consistent with the substance of the Brahmanda verse. And both the verses, putting the completion of the 27th century in the terminal portion of the Andhras, balance those which put the completion of the 24th in the initial portion.

The Andhra line consisted, according to most Puranas, of 30 kings. So the closing part should mean at least one-fourth of the number, the last 7 or 8 kings. We may hold that 2700 passed from 3177 B.C. up to some point in the reign of one of the last 7 Andhras. The total of these reigns in the Puranas is (28 + 7 + 3 + 29 + 6 + 10 + 7 = ) 90 years. Hence the end of the dynasty might be anywhere between (3177-2700 =) 477 B.C. and (477- 90 = ) 387 B.C.

As a complement to the Sapta Rishi computation we get from the Puranas a number of periods termed "intervals", which bring a greater exactness. From the birth of Parikshit to the Coronation of Mahapadma Nanda, founder of the dynasty just preceding the Mauryas, there was an interval which is variously given as 1015, 1050, and 1500 years. From this coronation to the beginning of the Andhras there was an interval of 836 years. Since 1500 years -- as Anand Swarup Gupta2 ["The Problem of Interpretation of the Puranas", Purana, Vol. VI, No. I. January, 1964, pp. 67-68. ] has recently reminded us tally with the total of the reign-lengths which most Puranas ascribe to the dynasties of Magadha from the Bharata War to Mahapadma's coronation,3 [Ibid., p. 68: Barhadrathas, 1000 years; Pradyotas, 138; Sisunagas, 362.] we may use it to reach the date of the rise of the Nandas. We get (3138-1500 = ) 1638 B.C. Then we reach the start of the Andhras in (1638-836 =) 802 B.C. The Puranas, as D.C. Sircar1 [The Satavahanas and the Chedis, The Age of Imperial Unity, edited by R. C. Majumdar and A.D. Pusalker (Bombay, 1951), p. 196, fn. 1 continued from p. 195. ] notes, record for the full run of the Andhras several numbers: 300, 411, 412, 456, 460 years. Out of these, 411 and 412 bring us from 802 B.C. to 391 and 390 B.C. respectively -- both the dates falling within the range 477- 387 B.C. obtained from the Sapta Rishi computation.

The next great dynasty after the Andhras is the Imperial Guptas. The Puranas mention the Guptas in general and connect a group of territories with them, which by being referred to no one particular Gupta would seem to be the persistent core, the stable heartland, of the expanding or contracting Gupta empire. But the Puranas supply no chronological matter about the Guptas, except that some lapse of time between them and the Andhras is suggested. Hence the Imperial Guptas, according to the Puranas, must come somewhere in the rest of the 4th century B.C. With a Chandragupta of Pataliputra at their head and a Sandrocottus becoming king of Palibothra in c. 325 or 324 B.C. by modern calculations, it is evident that Puranically Sandrocottus must be Chandragupta I of the Imperial Guptas and not Chandragupta Maurya.

Whatever we may say, by way of criticism, about the Kaliyuga's commencement in 3102 B.C. or the Bharata War's occurrence in 3138 B.C. or the coronation of Mahapadma Nanda in 1638 B.C. or even the start of the Andhras in 802 B.C., we cannot help being struck with the precision with which this chronology s ynchronises Chandragupta I with Sandrocottus.

Such a situation raises the question: "Which of the Chandraguptas was Sandrocottus at whose court Megasthenes lived?" And it is indeed very pertinent to ask: "Does Megasthenes offer any chronological clue to solve it?"

The Chronological Clue from Megasthenes

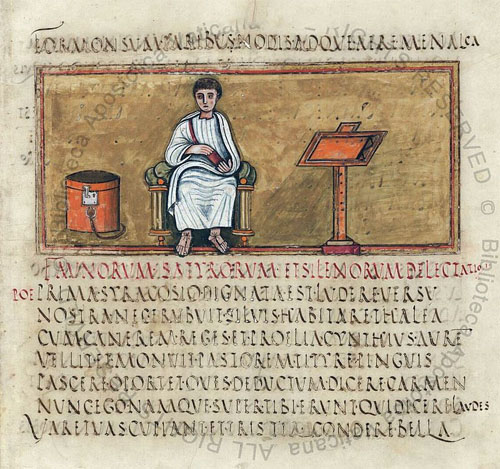

We have three versions of a statement by Megasthenes, which can bear upon our problem. J. McCrindle has translated all of them.1 [The Classical Accounts of India, edited with an Introduction, Notes and Comments by R. C. Majumdar (Calcutta, 1960),- pp. 840, 457, 223. ]

Pliny (VI. xxl. 4-5) reports about the Indians: "From the days of Father Bacchus to Alexander the Great, their kings are reckoned at 154, whose reigns extend over 6451 years and 3 months."

Solinus (52.5) says: "Father Bacchus was the first who invaded India, and was the first of all who triumphed, over the vanquished Indians. From him to Alexander the Great 6451 years are reckoned with 3 months additional, the calculation being made by counting the kings, who reigned in the intermediate period, to the number of 153."

Arrian (Indica, I. ix) observes: "From the time of Dionysus to Sandrocottus the Indians counted 153 kings and a period of 6042 years, but among these a republic was thrice established... and another to 300 years, and another to 120 years. The Indians also tell us, that Dionysus was earlier than Heracles by fifteen generations, and that except him no one made a hostile invasion of India.... but that Alexander indeed came and overthrew in war all whom he attacked..."

It would be worth while discussing the three versions in every detail and arriving at what must have been the full original pronouncement of Megasthenes which has thus got transmitted with some confusions and inconsistencies and one lacuna. But for our immediate purpose it will suffice to make a few clarifying observations and then inquire: "What historical or legendary figure mentioned by the Indians became identified with Dionysus (Bacchus) in the Greek mind to serve as the starting-point of Indian chronology and of the line of Indian kings?

First, we may note from the more expansive versions of Solinus and Arrian that Dionysus and Alexander are terms of comparison in respect of the invaders of India -- especially the Greek ones. Dionysus is declared to be the first who invaded India, Alexander the only other person to do so. The most appropriate way to connect them is by calculating the time that elapsed between them. Solinus gives us just this time-connection, To connect the two invaders by a number of kings, as does Pliny is controversial; for, it brings up at once the issue: "Does the number refer to the whole of ancient India?" 153 or 154 kings are far too few for the whole, in which there were a host of practically independent kingdoms, each with its own genealogy of rulers. The number must be in reference to merely one particular kingdom which was associated with Alexander and with which Dionysus may have been associated either directly or through some scion of his. But can we associate any such kingdom with Alexander? He subjugated several states, but he was not specifically a king of this or that state. So his name at one end of a king-series is an anomaly.

Quite the reverse is the case with Sandrocottus whose name in Arrians' king-series replaces Pliny's "Alexander". Sandrocottus, though emperor of many peoples, is specifically known as the King of the Prasii -- the Prasii whom Pliny elsewhere (VI.22) describes as the greatest nation in India. We can easily conceive him as the tail-end of a line which goes back through various dynasties of kings of Palibothra to a hoary past along one branch among many leading to a common ancestor.

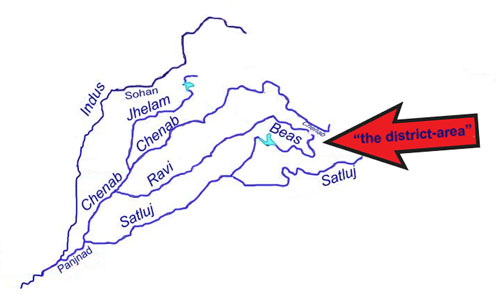

This conception seems natural when we realise that the small king-number was mentioned to Megasthenes at Palibothra itself, where he was stationed as ambassador. And what endows this conception with inevitability is the importance which Indian chronologists and historians have given to Magadha whose capital was Palibothra: the kings of Magadha after the Bharata War are the principal theme of the Puranic lists of dynasties, Sandrocottus and not Alexander was certainly the terminus intended by Megasthenes to the king-series the Indians mentioned to him.

But this series, although not related to Alexander, can well serve to describe from the Magadhan point of view the time-span from Dionysus to Alexander. And that is exactly how Solinus uses it, even if without the implication of Magadha such as Arrian has. Arrian too is justified in using it to describe the time-span from Dionysus to Sandrocottus. For, the two time-spans could not be much different. Alexander and Sandrocottus were contemporaries, and the gap of over 409 years which is there between the number in Arrian and that in Pliny or Solinus is a gross mistake. Arrian's time-span should really be not so much less nor even the same but a little more. Plutarch1 [Life of Alexander, LXIII. ] as well as Justin2 [Historiarum Philippicarum, XV. 1 v.] record that when Alexander, some time after his invasion, met Sandrocottus, the latter was not yet a king. According to Plutarch, the meeting took place round about the time the Macedonians "most resolutely opposed Alexander when he insisted that they should cross the Ganges". Alexander's progress came to a halt at approximately the end of July 326 B.C.3 [ "Foreign Invasions" by R. K. Mookerji, The Age of Imperial Unity p. 50. ] Thus we are sure that Sandrocottus mounted the throne of Palibothra later than this date. If we accept the more detailed time-span -- 6451 years and 3 months -- conveyed by Pliny and Solinus as our basis and if we try to guess the one in Arrian by introducing the least possible changes in the figures which he supplies, Sandrocottus's coronation must have been not 6042 but 6452 years after what Arrian calls "the time of Dionysus" and Pliny "the days of Father Bacchus".

Here we must consider the import of these two phrases, for they determine how we should count the 153 or 154 kings. Do they direct us to the beginning of Dionysus's kingship in India or to the end of it? In other words, is Dionysus included in the 153 or 154 kings? The phrase "From... to" employed by all the writers is ambiguous, whether we apply it to the "time" and "days" or to the king-number. Luckily we have an unequivocal phrase in Solinus to guide us: "the calculation being made by counting the kings who reigned in the intermediate period..." The reference is to the number of years and months from Dionysus to Alexander and these years and months are brought into relation with the number of kings. About both the time-period and the king-series we get the clear term: "intermediate". The number of kings applies to those who reigned between the days of Dionysus and the days of Alexander: the total of their reigns -- 6451 years and 3 months -- applies also to the period between the reigns of Dionysus and Alexander. After Dionysus ceased reigning and before Alexander started doing so we have the intermediate period. Similarly, the kings who are counted are the ones succeeding Dionysus and preceding Alexander. Indeed, Dionysus, who "was the first of all who triumphed over the vanquished Indians", must be counted as the first king over the Indians. But he is not a part of the 153 or 154 kings. Neither is Sandrocottus. If we count both of them, the king-number will be 155 or 156.

The final point to glance at is: "Which of the two king-numbers is to be accepted?" Since two authors out of three give 153 and since Arrian who correctly refers the king-series to Sandrocottus is one of them, 153 would appear to have more weight. But, when the difference of 154 from it is exceedingly small, perhaps the two serial numbers are there because of a disagreement among computers whether a certain name was to be included or not in the full tally.

In view of all our observations our job is to link Sandrocottus with an intervening chain of 153 or 154 kings to the ancient monarch of India whom the Greeks named Dionysus. By doing it we should be able to decide between Chandragupta Maurya and Chandragupta I for Sandrocottus and between the rise of the Mauryas and the rise of the Imperial Guptas for 325 or 324 B.C. The whole of ancient Indian chronology hinges on our decision apropos of the clue from Megasthenes.

Dionysus in India

Obviously, to come to a decision we must consult the Indian sources on which Megasthenes based himself. Where time-periods or king-lists are concerned, the informants of Megasthenes are very likely to have been Puranic pundits. "In fact," says D. R. Manked1 [Puranic Chronology (Anand, 1951), p. 2. ] rightly, "apart from the Puranas, there is no other source for such information." No doubt, the early Puraras were not quite in the form which we have today of this kind of literature, but there must have been many things in common and we are justified in tracing the extant Puranic documents to versions in fairly ancient times. "The early versions of the Puranas", A.D. Pusalker2 [Studies in the Epics and Puranas (Bhavan's Book University, Bombay, 1955), p. lxvi.] sums up, "existed at the period of the Bharata War and that of Megasthenes." And, like the original work of Megasthenes himself, these versions must have had a consistent tale of historico-chronological indications, which at present we can partly rebuild only by critical collation of the various reports.

Along with the Puranas there were some other traditional accounts -- the Vedas, the Brahmanas and the Epics. These too we must draw upon wherever necessary in our search for Dionysus in India.

Strictly speaking, the religious Indian analogue of Dionysus, god of wine, is Soma. Soma is apostrophised in the Rigveda as lord of the wine of delight (ananda) and immortality (amrita), pouring himself into gods and men, the deity who is also deep-hidden in the growths of the earth, waiting to be released us a rapture-flow for men and gods. In the times after the Rigveda, Soma emerges more specifically as a lunar god no less than as a king of the vegetable world with his being of nectar passing between heaven and earth through ritual and sacrifice. During those times, Soma is also regarded, in the earliest reference to the origin of kingship (Aitareya Brahmana, 1.14), as the god whom the other gods, seeking to fight the Titans (Asuras) effectively, elected as their king after having lived without a king so far. In the Satapatha Brahmana (V. 3. 3. 12; 4. 2. 3; XIII. 6. 2. 18; 7. 1. 13) the Brahmins speak of Soma as their king while common folk acknowledge an earthly monarch. The same book (XI, 4.3.9) applies to Soma the epithet (Raja-pati), "lord of kings." All this goes to suggest that Soma in ancient Indian tradition was the primeval as well as the supreme king from the religious stand-point.

But the true religious analogue of Dionysus need not be exclusively what the Greeks had in view, and we are concerned with the Indian figure whom they in the days of Alexander and Megasthenes identified with their Dionysus for various reasons, among which a strong touch of Soma, even if inevitable, might yet be only one stimulus. Besides, although Megasthenes connects wine with some religious ceremonies in India, there seems to have been in the country then no marked cult of the wine-god. The god mentioned as "Soroadeios" and interpreted to Alexander as "maker of wine" is now recognised to have been "Suryadeva", the sun-god. "Some illiterate interpreter" , E. Bevan1 [ The Cambridge History of India (1923), Vol. I, p . 422. ] explains, "must have been misled by the resemblance of Surya, 'sun', to Sura, 'wine'."

In the absence of a marked cult of Soma, the wide-spread Indian worship, which the Greeks reported, of Dionysus must indicate some other deity tinged with Soma-characteristics. The unanimous vote of scholars, bearing on Strabo's statement (XV, I) from Magasthenes that the Indians who lived on the mountains worshipped Dionysus, whereas the philosophers of the plains worshipped Heracles, is for Shiva, who was worshipped with revelry by certain hill-tribes. The pillar symbol, linga, associated popularly with Shiva as a phallus, making him a fertility god, and the bull which goes with him as his vahana, vehicle -- these two characteristics must have affirmed him still further with Dionysus who "is believed to have been originally a Thracian fertility god worshipped in the form of a bull with orgiastic rites".2 [Smaller Classical Dictionary (Everyman), p. 110, col. 2. ] and whose exoteric symbol, the phallus, was carried about in the rural festivals as well as in the mysteries.3 [The Encyclopaedia Britannica (13th Ed.), Vol. VIII, p. 287, col. 2.]

But surely when the Greeks spoke of royal history running in India from the time of Dionysus to that of Alexander and Sandrocottus, their Dionysus was a fusion of this Shiva with some legendary hero who, unlike Shiva, was celebrated as a primal king and who carried even more than Shiva a Soma-colour in some way affirming him to the wine-aspect of the Hellenic god.

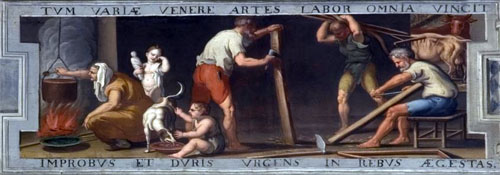

The fusion is to be expected, since he was to the Greeks as much an empire-builder as a god. In the imagination of the Macedonian soldiers he was the subject of Euripides's fable -- a conqueror of the East whom they endowed with a constructive role in the remote past of India. This role bulked large in the thought of Megasthenes and it is well spotlighted by Arrian, (Indian, I, vii) drawing upon the Greek ambassador's book: "Dionysus,... when he came and conquered the people, founded cities and gave laws to these cities and introduced the use of wine among the Indians, as he had done among the Greeks, and taught them to sow the land, himself supplying seeds for the purpose... It is also said that Dionysus first yoked oxen to the plough and made many of the Indians husbandmen instead of nomads, and furnished them with the implements of agriculture; and that the Indians worship the other gods, and Dionysus himself in particular, with cymbals and drums, because he so taught them; and that he also taught them the Satyric dance, or, as the Greeks call it, the Kordax; and that he instructed the Indians to let their hair grow long in honour of the god, and to wear the turban; and that he taught them to anoint themselves with unguents, so that even up to the time of Alexander the Indians marshalled for battle to the sound of cymbals and drums." Then Arrian refers to Dionysus's departure from India after having established the new order of things and having appointed as king of the country one of his companions who was the most conversant with Bacchic matters and who subsequently reigned for 52 years. Among the cities founded by Dionysus, Arrian (Anabasis, V.I; Indica, I. 1) in company with all his fellow-annalists names only Nysa (in the Hindu Rush), so called after either Dionysus's nurse or his native mountain.

Some further points may be cited from Diodorus. Like others he (II. 38) mentions the Indian mountain "Meros" (Meru), at whose foot lay the city of Nysa, as a place where Dionysus bad been, and he links with its name the Greek legend that Dionysus was bred in his father Zeus's thigh (meros in Greek). In a few things Diodorus differs from what most authors have quoted from Megasthenes. After repeating the story of the invasion of India by Dionysus, he (ibid.) mentions Dionysus as not leaving the country after his achievements but as reigning over the whole of India for 52 years and then dying of old age while his sons succeeded to the government and transmitted the sceptre in unbroken succession to their posterity. What is more, Diodorus (III. 63) shows us that the Greeks knew of a counter-legend to the one about the entry of Dionysus into India from the west. And from this counter-legend the starter of the king-series to whom the Indians referred emerges in a clearer shape:

"Now some,... supposing that there were three individuals of this name, who lived in different ages, assign to each appropriate achievements. They say, then, the most ancient of them was Indos, and that as the country, with its genial temperature, produced spontaneously the vine-tree in great abundance, he was the first who crushed grapes and discovered the use of the properties of wine... Diouysus, then, at the head of an army, marched to every part of the world, and taught mankind the planting of the vine, and how to crush grapes in the winepress, whence he was called Lenaios. Having in like manner imparted to all a knowledge of his other inventions, he obtained after his departure from among men immortal honour from those who had benefited by his labours. It is further said that the place is pointed out in India even to this day where the god had been, and that cities are called by his name in the vernacular dialects, and that many other important evidences still exist of his having been born in India..."

There are some more details to the Dionysus-story, but all about him is not of equal importance; and those points in particular which have too clearly a Greek colour cannot be of much help to us. A few points which strike us as rather fanciful may also be passed over.

What we have mainly to match from Indian sources is an ancient human-divine personage who is a great progressive and constructive leader, no less than a conqueror -- one who is organically knit together with the country's traditional history and geography and stands deified in legend at the head of all royal successions in India.

The Three Candidates

Indian tradition shows us three human-divine personages, each of whom in an important sense is a king in the past and acted as a fundamental force of progress.

Legendary India starts with Manu Svayambhuva.1 [The Vedic Age, edited by R. G. Majumdar and A.D. Pusalker (London, 1952), pp. 270-71. ] He is reputed to have subdued all enemies, become the first king of the earth and revived the institutions of the four castes and of marriage, which had been established by his predecessor and progenitor, the deity Brahma.

With a status similar in another epoch is Manu Vaivasvata.2 [Ibid., pp. 271-72. ] He is said to be the originator of the human race and all the dynasties mentioned in the Puranas spring from him. He framed rules and laws of government, and collected a sixth of the produce of the land as a tax to meet administrative expenses. He is also famous for having saved humanity from the deluge which occurred at this time.

As a conqueror, Dionysus may be seen as resembling Svayambhuva. As a law-giver, he may be traced in Vaivasvata. As a primal king, he is more like Vaivasvata than Svayambhuva, for, though both are royal genealogy-starters in their own ways, the latter is such simply by being the first Indian -- and Dionysus, even as "Indos", was not the Adam of India. But in all his other capacities Dionysus is not at all like either Vaivasvata or Svayambhuva.

The third human-divine figure who is a primal king in Indian eyes stands in time intermediate between Svayambhuva and Vaivasvata: he is Prithu Vainya -- Prithu, the son of Vena. When we examine him, we discover that in all important respects he is the candidate par excellence for the Indian Dionysus.