Appendix: Alexander and the Ganges: A Question of Probability

Excerpt from Alexander and the East: The Tragedy of Triumph

by A.B. Bosworth

© A.B. Bosworth 1996

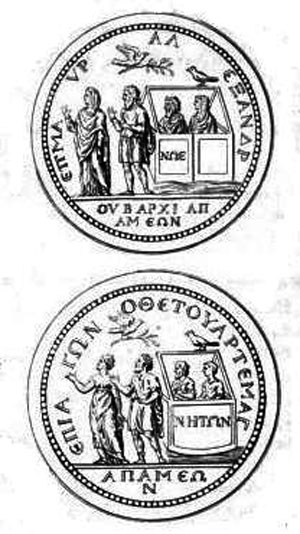

47. The country inland from Barygaza is inhabited by numerous tribes, such as the Arattii, the Arachosii, the Gandaraei and the people of Poclais, in which is Bucephalus Alexandria. Above these is the very warlike nation of the Bactrians, who are under their own king. And Alexander, setting out from these parts, penetrated to the Ganges, leaving aside Damirica and the southern part of India; and to the present day ancient drachmae are current in Barygaza, coming from this country, bearing inscriptions in Greek letters, and the devices of those who reigned after Alexander, Apollodorus and Menander. [Librarian's Comment: A significant and presumably knowing omission from the Wikipedia article on the Periplus is paragraph 47, missing along with everything from 42-48, this extraordinary piece of testimony that cuts against the general trend of Indian pseudo-history that contends Alexander never reached the Ganges. Indeed, never crossed the Indus, spooked by Sandrocottus' herd of war elephants.]

-- The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: Travel and Trade in the Indian Ocean by a Merchant of the First Century, Translated & edited by W.H. Schoff (London, Bombay & Calcutta 1912).

Maurya ... it seems that Chandragupta went by that name, particularly in the west; for he is known to Arabian writers by the name of Mur, according to the Nubian geographer, who says that he was defeated and killed by Alexander; for these authors supposed that this conqueror crossed the Ganges; and it is also the opinion of some ancient historians in the west.

-- Essay III. Of the Kings of Magadha; their Chronology, by Captain Wilford, Asiatic Researches, Volume 9, 1809. pgs. 94-100.

Most contentious issues in the reign of Alexander have a distinctly cyclical aspect. Long ago Ernst Badian.1 [E. Badian, in Ancient Society and Institutions: Studies Presented to Victor Ehrenberg 65-6 n. 56.] criticized Schachermeyr's claim that 'today we know' that the Greeks of Asia were not in the League of Corinth. 'Yesterday, presumably, we "knew" that they were; and who knows what we shall "know" tomorrow?" Eternal verities are beyond our grasp when there is little or no evidence at our disposal, as is the case with the Asiatic Greeks and the Corinthian League.2 [Schachermeyr at least absorbed the lesson. In the 2nd edn. of his work on Alexander he weakened his confident assertion. 'Heute wir wissen' [Google translate: Today we know.] became 'Heute glauben wir zu wissen' [Google translate: Today we think we know] (Al.2 177), and in a subsequent fn. he added that the data was insufficient for stringent proof and that his views should be regarded as hypothetical and provisional (Al.2 258 n. 295).] Interpretation and speculation have free rein. However, even where explicit evidence exists, we may find a comparable cycle of acceptance and scepticism. One school accepts the source testimony at face value and builds upon it; another dismisses the evidence as distorted or tainted and excludes it from any historical reconstruction. Such exclusion can be justified if the source material is in conflict with other evidence adjudged more incontrovertible, or transcends the bounds of possibility. However, what transcends the bounds of possibility often coincides with what is uncomfortable to believe. One sets one's own limits upon what Alexander may have thought, planned, and done, and accepts or rejects the source material by that criterion. Credo, ergo est [Google translate: Therefore it is] becomes the unstated methodological rule.

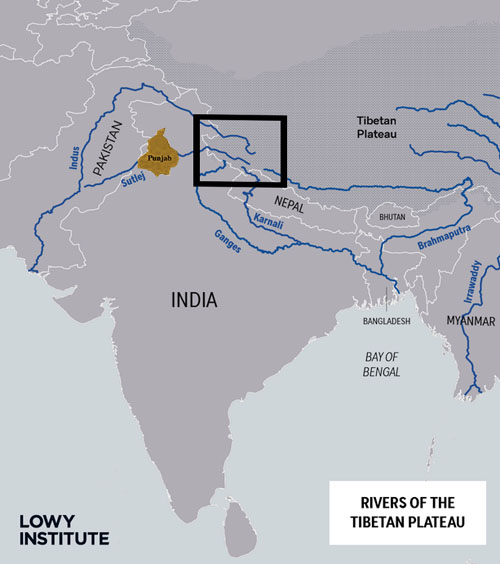

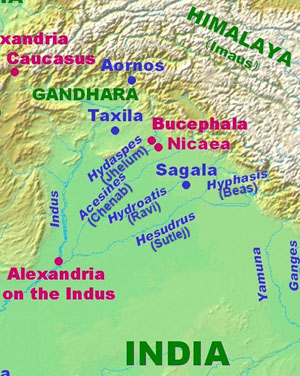

The issue which best exemplifies this dilemma is the famous Ganges question. Is it credible that Alexander had reasonably accurate information about the Ganges river system and planned to extend his conquests there? On a priori considerations it would seem highly probable. He spent a spring and a summer in the northern Punjab, penetrating as far east as the river Hyphasis (modern Beas). In the course of that campaign he carried out detailed topographical investigations as far as the Indus mouth (which refuted his rashly formed belief that the Indus and Nile were interconnected).3 [Arr. 6. I. 5; Strabo 15. I. 25 (696) = Nearchus, FGrR 133 F 20. On this strange episode see above, Ch. 3.] He was in close contact with the local native rulers and naturally questioned them about conditions on the march ahead. It is surely to be inferred that he received information about the river system of the Jumna and Ganges, no more than 250 km., as the crow flies, east of the Hyphasis. When three separate source traditions corroborate that probability it would seem perverse to question it, and it is fair to state that most modern authorities have accepted that Alexander had some knowledge of the Ganges.4 [That was the consensus of earlier scholars. The doyen of Indianologists, Christian Lassen stated categorically that Alexander intended to take his conquests to the mouth of the Ganges (Indische Altertumskunde ii.2 171- 3). Droysen i.2 2. 165, was more cautious about Alexander's aims, but took it as axiomatic that he knew of the Ganges. So too the influential monograph by A. E. Anspach, De Alexandri Magni expeditione Indica (Leipzig 1903) 77-9. In more recent times the most eloquent and systematic defender of what may be termed the traditional view has been Fritz Schachermeyr, 'Alexander und die Ganges-Lander', IBK 3 (1955) 123-35 (= G. T. Griffith (ed.), Alexander the Great: The Main Problems (Cambridge, 1966) 137-49). For a sample of obiter dicta see U. Wilcken, Alexander the Great 185-6; Green 407-8; N. G. L. Hammond, KCS2 218: Bosworth, Conquest and Empire 132-3.]

There is, however, a strong sceptical minority. The most eloquent and authoritative attack upon the ancient tradition came from Sir William Tarn, who in 1923 argued that Alexander 'never knew of the Ganges or of Magadha, any more than he knew of the vast Middle Country between the Sutlej and the Ganges',5 [Tarn, JHS 43 (1923) 93-101. He had a forerunner in Niese i. 138-9, 509.] and in 1948 he was to refine his case, noting but not addressing the criticisms made in the meantime by Ernst Meyer.6 [Tarn, Al. ii. 275-85. Meyer's criticism (Klio 21 (1927) 183-91) is noted in a single footnote (279 n. 2) with a contemptuous aside: the proposal to supplement the name Ganges at Diod. 18.6.2 'is indefensible and merely darkens counsel: I need not refute Ernst Meyer's attempts to defend it'.] In 1965 Dietmar Kienast came to the same conclusion by a somewhat different route,7 [D. Kienast, Historia 14 (1965) 180-8.] and most recently T. R. Robinson has attempted the demolition of a critical (but not decisive) branch of the source tradition.8 [T. R. Robinson, AHB 7 (1993) 84-99.] What these approaches have in common is an insistence that the only evidence which can be accepted without reservation is a single passage of Arrian (5. 25. 1), which describes Alexander's ambitions beyond the Hyphasis without reference to the Ganges and without apparent knowledge of the centralized Nanda kingdom in the lower Ganges valley.9 [Kienast's exposition (above, n. 7, 180-1) is typical: 'Dieser sehr detaillierte Bericht, der offen bar aus guter Quelle (wohl Aristobul) stammt, weiss also nichts vom Ganges, sondern nur von dem Lande unmittelbar jenseits des Hyphasis.' [Google translate: This very detailed one Report, which apparently comes from a good source (probably Aristobulus), does not know anything about it Ganges, but only from the land immediately beyond the Hyphasis.] The vulgate tradition, common to Diodorus, Curtius, and the Metz Epitome,10 [Diod. 17.93. 2-4; Curt. 9. 2. 2-9; Metz Epit. 68-9; cf. Plut. Al. 62. 2-3; Justin 12. 8. 9-10 (heavily abbreviated and garbled).] reports that Alexander did receive information about the Ganges and the eastern kingdom, and is necessarily dismissed as romantic embroidery, dating from the period when Megasthenes' embassy to Chandragupta had brought eyewitness information about the Ganges and the great eastern capital of Pataliputra.

Historiae survives in 123 codices, or bound manuscripts, all deriving from an original in the 9th century. As it was a partial text, already missing large pieces, they are partial as well. They vary in condition. Some are more partial than others, with lacunae that developed since the 9th century. The original contained ten libri, "books," equivalent to our chapters. Book I and II are missing, along with any Introduction that might have been expected according to ancient custom. There are gaps in V, VI, and X. Many loci, or "places," throughout are obscure, subject to interpretation or emendation in the name of restoration.

The work enjoyed popularity in the High Middle Ages. It is the main source for a genre of tales termed the Alexander Romance (some say romances); for example, Walter of Chatillon's epic poem Alexandreis, which was written in the style of Virgil's Aeneid. These romances spilled over into the Renaissance, especially of Italy, where Curtius was idolized. Painters, such as Paolo Veronese and Charles Le Brun, painted scenes from Curtius...

-- Quintus Curtius Rufus, by Wikipedia

11 [So Robinson (above, n. 8) 98-9. Tarn Al. ii. 282-3 considered that the 'legends' of Alexander and the Ganges dated to the second century BC and reflect the history of the Indo-Bactrian monarchy. Kienast (above, n. 7) 187-8 comes to a minimalist sceptical position: both Hieronymus and Cleitarchus knew of the Ganges, the former through the campaigns of Eumenes, but there is no conclusive evidence that Alexander planned to take his conquests beyond the Punjab.] We therefore have only one piece of 'reliable' evidence; the rest of the tradition is argued away. However, even if we accept the argumentation, it does not prove the sceptical case. The minuscule piece of 'reliable' evidence is silent about Alexander's knowledge of the Ganges. Even if we accept every word of Arrian, one could still argue that he had been informed of the existence of the great river.12 [As is honestly and candidly admitted by Kienast 181: 'Andererseits kann man auch nicht schlussig beweisen, dass Alexander vom Ganges keine Kenntnis hatte.' [Google translate: On the other hand, you can also not conclusively prove that Alexander had no knowledge of the Ganges.]] The intrinsic probability remains. No source contains or hints at the negative.

Of the various pieces of source material buttressing the case for Alexander's knowledge of the Ganges by far the most important (and problematic) is a tradition represented in two passages of Diodorus.13 [Diod. 2.37. 2-3; 18. 6. 1-2.] In Book 2 he grafts on to his digest of Megasthenes' account of India a description of the Ganges which patently comes from another source.14 [The width of the Ganges is totally at odds with Megasthenes' well-attested statement that its median (or minimum) breadth was 100 stades (Arr. Ind. 4. 7; Strabo 15. I. 35 (702) = Megasthenes FGrH 715 F 9).] The river is described as 30 stades wide, flowing from north to south (as the Ganges does in its western reaches) and dividing off to the east the Gandaridae, who had the largest and most numerous elephants in India. No foreign king had ever conquered them because of the number and ferocity of these beasts.15 [The statement is restricted to the Gandaridae. It is hardly a sentence of Megasthenes grafted into an alien context, as is argued by Robinson (above: n. 8) 93- 5. Megasthenes claimed that all India had been immune from invasion until the time of Alexander (Arr. Ind. 5. 4-7; Strabo 15. 1. 6 (686-7) = FGrH 715 F II; cf. Diod. 2. 39.4; Arr. Ind. 9. 10-11 = FGrH 715 F 14). The uniqueness of Megasthenes was to deny the Achaemenid conquest of western India. Any source might have claimed that the eastern land had been immune from invasion.] Alexander himself came to the Ganges after subjugating the rest of the Indians but gave up the expedition on learning that his adversaries possessed 4,000 elephants. This information is neatly paralleled in the context of the so-called Gazetteer of Empire in Book 18.16 [Diod. 18. 6. 1-2. On the Gazeteeer in general see Hornblower, Hieronymus 80-7. 'Geographical review' is a better label than 'Gazetteer', but the term is now sanctioned by use.]

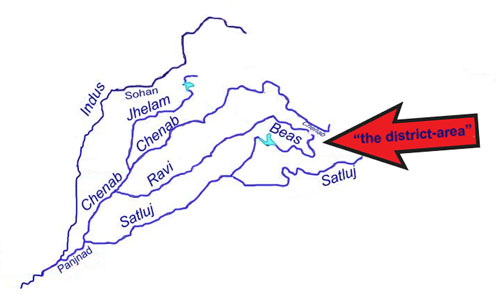

When Alexander turned back at the Hyphasis (Beas), how much did he know about what lay before him? And why, in the vulgate tradition, does he know of the distant Ganges and the distant kingdom of Magadha, but not of the next great river to the Beas, the Sutlej (a question often asked), or of anything else between the Beas and the Ganges?...

We possess one contemporary document bearing on the matter which has escaped notice, a satrapy-list or gazetteer of ‘Asia,' i.e. Alexander's empire, [‘Asia’ or ’all Asia’ means, in the later part of the fourth century, the Persian Empire which Alexander claimed to rule...]... We can date this document with certainty. It includes the Indian provinces, and so is later than Alexander's return from India. The ‘Hyrcanian sea’ (not Caspian) is still a lake, so it is earlier than Patrocles. Chandragupta is unknown, so it is certainly earlier than Megasthenes and probably earlier than circ. 302. Porus is still alive, so it is earlier than 317. Susiana ‘happens to be' part of Persis, i.e. it was under the same satrap, which can only have happened at one point in the story: the satrap is Peucestas... Media is still undivided; so the document is earlier than the partition of Babylon in 323, when Media was divided between Peithon and Atropates. Lastly, Armenia still appears as a satrapy of the empire, whereas the fiction of an Armenian satrapy was abandoned at the partition of Babylon, and this is decisive. The gazetteer then dates between spring 324 and June-July 323...

This document divides the empire into north and south of the Taurus-'Caucasus‘ line.8 [Eratosthenes took his similar division from this document, and not vice versa; apart from the date, which is certain, it contains no trace of the real characteristic of his geographical scheme, the [x].] After dealing with the northern provinces, it begins in 18, 6. 1 on the southern provinces, working from east to west; India therefore comes first. What it says about India, in Diodorus’ version, is this: India lies along ([x]) the Caucasus, and is a large kingdom of several peoples, the greatest of them being the Tyndaridae (or Gandaridae), whom Alexander did not attack because of their elephants. A river, the greatest in that district ([x]), 30 stades broad, divides ([x]) this country ([x]) — I think this means the India already described, but it might mean the Tyndaridae — from the India that comes next, i.e. further westward ([x]). Bordering on this country ([x]) — i.e. either on the India already described or on the Tyndaridae — is the rest of India which Alexander conquered ([x] above), through the middle of which runs the Indus. That is to say, Alexander's conquests are divided from the rest of India by an unnamed river: independent India beyond this river is a single kingdom, associated with a name. Note especially that the gazetteer, like the sources used by Arrian in his narrative, does not mention the two names which play such a part in the vulgate tradition, the Ganges and the Prasii: and, looking at what the gazetteer does say about India, this shows conclusively that neither was known to its author, that is, to those about Alexander in 324/3. Alexander then can have known nothing of the Ganges or of Magadha, but it remains to see how the vulgate tradition arose...

The first Greek to visit and describe the Ganges and the Prasii was Megasthenes...The Prasii are his name for Magadha, as is shown by Pataliputra being their capital...Magadha in actual fact lay on this side of (i.e. south and west of) the Ganges, and its empire (before Chandragupta) lay further west still...

Cleitarchus, who fixed the vulgate tradition about Alexander, did not accompany Alexander to Asia and was not with him in India; he was not one of the contemporary historians of the expedition, and is not a primary source, but was a literary compiler belonging to a later generation. It is certain now that he cannot have written earlier than the decade 280-270; and there are grounds, though not conclusive grounds, for putting his book even later, after 260....The points proven are that Cleitarchus used Berossos, Patrocles, and Timaeus, and had never himself seen Babylon...he wrote much later than Megasthenes....

in the vulgate, Alexander, when he reaches the Beas, hears of the Ganges and the Prasii, whom he desires to conquer; the story is given by both Diodorus and Curtius, and is our only professed account of what he knew when he turned back, though the good tradition, as we shall see, has a very different account of what the army believed....Diodorus, Book 17, primarily represents Cleitarchus... Diodorus and Curtius agree here, among other things, in one most extraordinary perversion, which therefore goes back to Cleitarchus also, and which is the key of the whole matter; the Prasii are beyond the Ganges. This strange mistake also occurs in Plut. Alex. 62, where the Prasii hold the further bank...

Cleitarchus must have had before him, among the other documents which we know he used, the two we have here noticed, the gazetteer of 324/3, and Megasthenes.... In the first he found an unnamed river, called the greatest in the district, and a named kingdom beyond it. In the second he found the greatest river in India, the Ganges, and a kingdom whose capital stood on its bank, though in fact the kingdom stretched out westward. Like Fischer in his edition of Diodorus, he identified the two rivers and called the unnamed river the Ganges; and the kingdom of the Tyndaridae or Gandaridae, beyond the unnamed river, he then naturally identified with that of the Prasii, which he then necessarily placed beyond the Ganges; hence in the Cleitarchean vulgate this kingdom regularly appears as ‘the Gandaridae (or Gangaridae) and Prasii.' Starting from this identification, he then wrote up Alexander in his usual fashion, not knowing that he had left out most of Northern India....he was a very bad geographer in any case, and the man who could confuse two such well-known rivers as the Hydaspes and the Acesines would have had no difficulty in confusing the unnamed river and the Ganges....

Fortunately he left untouched an easy means of checking his mistake: the breadths of the rivers. The unnamed river of the gazetteer is 30 stades broad. Megasthenes' Ganges is not less than 100 stades broad.... The breadth alone then is sufficient proof that the ‘Ganges’ of Cleitarchus-Diodorus is only the unnamed river of the gazetteer....

On the other hand, Diod. 17, 108, 3 — the Macedonians refuse to cross the Ganges — has nothing directly to do with this identification: it is a reference, not part of the narrative, and is therefore not Cleitarchus; it belongs to a later legend...As 2, 37, 2 represents the gazetteer, it is interesting to note that it gives one detail not given in 18, 6, 1: the river in question, the unnamed river, runs from north to south. It was well enough known since Megasthenes that all the middle Ganges, above Pataliputra, ran roughly west and east....

Before leaving Cleitarchus, one other point may be noticed. His story about the Ganges and the Prasii is told to Alexander by a rajah on the Beas named Phegeus, who begins by saying that across the river is a desert of eleven (Curtius) or twelve (Diodorus) days’ journey. No Indian living on the upper Beas could have said this. If Phegeus, who is unknown to the good tradition, ever existed, he lived much further south, near the Rajputana desert; but he may be as mythical as some other characters in the vulgate. That Cleitarchus put his Ganges story in the mouth of a man who begins by placing the great desert on the east bank of the upper Beas is itself a good test of what that story is worth...

The statement that Alexander turned back from fear of the elephants is a late legend inserted by Diodorus himself...

Strictly construed, the gazetteer imports that Alexander claimed India up to the Sutlej; and it is possible enough that he did. Across the Beas, says Arr. 5, 25, 1, was a people aristocratically governed (i.e. an Aratta people) with many elephants. [Amplified in Strabo, 15, 702: a ruling oligarchy of 5000, each of whom gave an elephant to the State!] This can hardly go back to the Journal, from its form; probably it is Aristobulas repeating camp gossip, for the Aratta known to us had no elephants... we get some support for the suggestion that the rule of Darius I. had ended at the Beas, where Alexander's men refused to go on...

The conclusion then is that Alexander, when he turned back, knew of the Sutlej, and vaguely of some kingdom beyond it, with which the name Gandaridae or Tyndaridae was connected. He never knew of the Ganges or of Magadha, any more than he ever knew of the vast Middle Country between the Sutlej and the Ganges. What he did know was not of a nature to shake his conviction, based primarily on the Aristotelian geography, that Ocean lay at quite a short distance in front of him, as is proved by his desire still to advance in spite of the great reduction in his small striking force by troops left on communications... The story that he knew of the Ganges and Magadha, which is unknown to the good tradition, has been written into the vulgate from Megasthenes through a mistake which I have traced; and by means of this story the vulgate has attributed to Alexander a scheme of conquest [The vulgate's idea that Alexander meant to cross the Ganges, involving a conflict with Magadha, would almost arise naturally from its substitution of the Ganges for the Sutlej] which has no basis in fact, because he knew nothing of the existence of the place whose conquest was the object of the scheme. The legend of the plan to conquer Magadha, however, matured much faster than the parallel legend of the plan to conquer Carthage and the Mediterranean, whose growth I have previously traced... The first step was that someone forged a letter from Craterus to his mother (Strabo 15, 702) in which Alexander reaches the Ganges. Then follow two stories; in the one, preserved by Diodorus, 2, 37, 3, Alexander reaches the Ganges but dare not attack the Gandaridae (sic) because of their 4000 elephants; in the other, given in Plut. Alex. 62 and alluded to in Diodorus 17, 108, 3, he reaches the Ganges and desires to cross, but the army refuses. (As in Plutarch the ‘Gandaritae and Prasii hold the further bank, which represents the blunder made by Cleitarchus which this paper has been tracing, we have here an excellent instance of later legend springing from the Cleitarchean vulgate; it is illuminating for Plutarch's indiscriminate use of material.) Finally, in Justin 12, 8, 9, Alexander does conquer Magadha: Praesios, Gangaridas, caesis eorum exercitibus expugnat. [Google translate: To preside over Gangaridae, and cut off their end to its armies.] The statement in Diodorus' version of the gazetteer, 18, 6, 1, that Alexander did not attack the Gandaridae because of their elephants, is then a mere remark of Diodorus' own, quoted from his own version of the legend in 2, 37, 3. Like many legends, it possesses a minute substratum of fact; the report about the elephants across the Beas. Arr. 5, 25, 1, was one of the causes which decided Alexander's army to go no further.

-- Alexander and the Ganges, by William Woodthorpe Tarn

There Diodorus reviews the various components of the eastern Empire of Alexander's successors and begins his enumeration of the southern lands from the far east. First is India, a large and populous kingdom, boasting several nations, the largest of which is the 'Tyndaridae' against whom Alexander did not campaign because of the number of their elephants. That country is divided from the next portion of India by a river which is not named in the text but is described as the greatest in those parts, with a width of 30 stades.

The similarities of these passages is such that one naturally assumes that they are derived from a single source: the 'Tyndaridae' of the second passage are simply a corruption of the Gandaridae of the first,17 [This to my knowledge has never been questioned. Gandaridae to Tyndaridae is an easy scribal error, imposing a recognizable Greek name upon an unfamiliar foreign term. The corruption incidentally supports the traditional correction [x] at 18. 6. I; in the Bude Goukowsky restored [x], which coheres with the Latin spellings of the name (see below, n. 29) and supports the interpretation that it is a general ethnic derived from the river ('people of the Ganges': cf. Goukowsky ad Diod. 17. 93. 2). However, such a spelling would lend itself less to corruption than [x], the invariable form given by the manuscripts at Diod. 17. 93. 2-4.] and the unnamed river of the second passage must be the Ganges. If both passages have a common original, the most likely source is Hieronymus of Cardia, who provided the narrative core for Diodorus in Book 18. The material would be anticipated in Book 2, and engrafted on the body of material from Megasthenes. There is a clear parallel in the anticipatory citation of Cleitarchus which Diodorus imposes upon the surrounding context, from Ctesias.18 [Diod. 2. 7. 3 = FGrH 137 F 10; cf. Curt. 5. 1. 26 with Hamilton, in Greece & the E. Med. 126-46, esp. 138-40; Bosworth, From Arrian to Alexander 10.] As for Hieronymus, he was much in Diodorus' mind in Book 2. The account of the Nabataean Arabs is patently part recapitulation, part repetition of a long excursus in Book 19, which was derived from Hieronymus, an eyewitness of the area.19 [Diod. 2. 48. 1-5 resumes the more extended description at 19.94. 2-10, while 2. 48. 6-10 is a virtual copy of 19.98. In its turn Diod. 2. I. 5 epitomizes the exposition at 2. 48. 2-5 (cf. P. Krumbholz, Rh. Mus. 44 (1889) 286-98, esp. 291-3). On Hieronymus' excursus in general see Hornblower, Hieronymus 144-53.] Part of this secondary draft is in turn extracted from its context and added to Ctesias' account of the campaign of Ninus. In exactly the same way a section from the Gazetteer in Book 18 is re-used in the context of Megasthenes' geography of India. In that case Alexander's plans for an invasion of the Ganges valley are attested by the near-contemporary Hieronymus, and Hieronymus is a formidable cachet of authenticity.

The strategy of the sceptics has necessarily been to distance the report of the Ganges from Hieronymus. Tarn in his most sophistical vein excised everything he disapproved of in the Gazetteer as an interpolation by Diodorus and failed to address the detailed correspondence with the parallel passage of Book 2.20 [The fullest exposition is Tarn, Al. ii. 277-9; the earlier discussion (JHS 43 (1923) 93-5) is less convoluted and involves only one interpolation (98: 'the part of the gazetteer given in Diod. 18.6. I seems to be given with substantial accuracy, subject, of course, to this, that the statement that Alexander turned back from fear of the elephants is a late legend inserted by Diodorus himself').] The more recent approach of Robinson is more coherent. It accepts that the second passage is unitary, but claims that the river there described is not the Ganges but the Hyphasis (Beas) and that the Gandaridae should be located not on the Ganges but immediately east of the Hyphasis (see Fig. 8 above).21 [Robinson (above, n. 8), esp. 84-5. Both hypotheses were foreshadowed by Tarn, who considered that the river of the Gazetteer could be the Sutlej, immediately east of the Hyphasis (JHS 43 (1923) 97-8; 25 years later (at Al. ii. 279) the 'unnamed river' becomes an interpolation by Diodorus), and argued repeatedly that the Gandaridae were displaced (see below).] This report Diodorus misinterpreted and combined incompetently with other material from Megasthenes (used in Book 2) and Cleitarchus (used in Book 17). Hieronymus, then, did not mention the Ganges, and it is only Diodorus' proverbial stupidity which gives the impression that he did.

Robinson's argument is undoubtedly ingenious, but its premisses are flawed, and unfortunately much of the material is taken directly from Tarn without any probing of the supporting evidence. Most illuminating is the key assertion that in Diodorus there is an eastward displacement of the Gandaridae. 'For the Gandaridae are generally associated with the eastern Punjab and the Indus system, not with the Gangetic plain.'22 [Robinson (above, n. 8) 89 with n. 13. Tarn in 1923 (above, n. 5, 98) suggested that the Gandaridae of the Gazetteer were somehow distinct from the Gandaridae of the vulgate and were located east of the Sutlej. In 1948 he was more radical and claimed that the Gandaridae were in fact the Indians of Gandhara, the old Achaemenid satrapy of the Kabul valley (Al. ii. 277-8).] This categorical assertion is documented by a reference to Kiessling's Pauly articles on 'Gandaris' and 'Gandaridae', which unequivocally locate the Gandaridae in the Ganges plain.23 [Kiessling, RE vii. 694-5 ('Gandaridai'), 695-6 ('Gandaris'); cf. 703-7 ('Ganges'). Kiessling was categorical that there were three separate areas: Achaemenid Gandhara, Gandaris in the Punjab, and the land of the Gandaridae in the lower Ganges, and considered the similarity of name an important indicator of the progress of Aryan migration (695, lines 49-58).] As Kiessling makes plain, there is no reference to Gandaridae west of the Ganges. We hear in passing that the princedom of the 'bad' Porus, which lay between the rivers Acesines and Hydraotes, was named Gandaris.24 [Strabo 15. 1. 30 (699). For the general location of the realm of the 'bad' Porus see Arr. 5. 21. 1-4.] That may or may not indicate some association with the people named Gandaridae, and in any case the location does not help Robinson. The 'bad' Porus ruled an area well to the west of the Hyphasis, not to the east of the river, where Robinson would locate the Gandaridae. Now this Porus fled in the face of Alexander's advance across the Punjab, in the early summer of 326, and we are informed that he fled to the land of the Gandaridae.25 [Diod. 17. 91. I (cf. Arr. 5. 21. 3 -- destination unnamed).] All that proves is that these Gandaridae were located somewhere east of the Hydraotes; it provides no information as to how far east they were found. Robinson suggests that they were directly beyond the Hyphasis, but it might also be argued that any Indian rajah who cared to flee rather than submit to Alexander would put the greatest distance possible between himself and the invader and seek sanctuary in the Ganges kingdom,26 [That was the automatic and plausible assumption of Lassen, Indische Altertumskunde ii.2 163 n. 3 (so Droysen i.2 2. 148 n. I). Why Anspach (above, n. 4) 64 n. 199 commented 'iam veri dissimile est trans Gangem tum fugisse Porum' [Google translate: Porus had fled to the other side of the Ganges as well as of the truth, but is differently now] I do not understand. There was the instructive object lesson of the regicide Barsaentes, who fled from his satrapy in central Iran to the Indians of Gandhara (cf. Berve ii. 102, no. 205). If we may believe Curtius (8. 13. 4), both Barsaentes and his Indian collaborator had been delivered to Alexander's justice shortly before the battle of the Hydaspes and the flight of the 'bad' Porus. It gave a defector every encouragement to fly as far as possible and choose the strongest possible protector.] as far away as possible.

Apart from the single reference to the princedom of 'Gandaris' there is only an oblique reference in Dionysius Periegetes to 'Gargaridae' near the 'gold-bearing Hypanis' (another name for the Hyphasis/Beas).27 [Dion. Per. 1143-8. Kiessling also adduced Peripl. M. Rubr. 47, in which a people named 'Tanthragoi' are attested inland from Barygaza (by the Rann of Kutch) and associated with Bucephala. But, even if the traditional correction 'Gandaraioi' is accepted, the passage is extraordinarily imprecise (cf. L. Casson, The Periplus Maris Erythraei 204-5) and contains the egregious error that Alexander penetrated to the Ganges. It cannot be used as evidence for Gandaridae in the Punjab.] Before we are transported by excitement at this, we should look at the context in Dionysius, which is a farrago of nonsense. The 'Hypanis' is associated with another mysterious river, the Magarsus, and both are said to flow down from the northern mountains into the Gangetic plain.28 [Dion. Per. 1146-7: [x]. It may be added that Dionysius (1152-60) also places Nysa (see below, p. 199) in the Gangetic plain. His view of Indian geography can only be termed chaotic. If the Gargaridae of Dionysius are in fact the Gandaridae of Diodorus, they are as much associated with the Ganges as they are with the Hyphasis. ]

[/quote]The Roman god Bacchus and his Greek counterpart Dionysos have long been associated with Nysa. The names Dionysos and Nysa are said to be etymologically related, though the exact connection is unclear.

Bacchus / Dionysos was the son of Jupiter and Semele. The pregnant Semele unwisely asked to see Jupiter in his flaming form, the sight causing her to burn to death. Jupiter rescued the embryonic Bacchus by placing him in his thigh to develop until birth. When Bacchus was born, Jupiter turned him over to the Nysiads, Oceanic nymphs, to raise. The Nysiads were associated with the mythic mount Nysa.

In the Iliad, Homer refers to Dionysos and associates him with this mountain. The speaker is Diomedes, stating his refusal to fight against any of the gods, as any victory against them is Pyrrhic:[x] (6.130–134)

In Stanley Lombardo's translation:Not even mighty Lycurgus lived long

After he tangled with the immortals,

Driving the nurses of Dionysus

Down over the Mountain of Nysa

And making them drop their wands

As he beat them with an ox-goad. (p. 116)

Since the worship of Dionysos entered Greece from either Asia Minor or neighboring Thrace, the god was associated with the east. Different mythographers located Nysa in different parts of Asia: Turkey, Arabia, or India. For ancient geographers, India meant the entire subcontinent east of the Hindu Kush and south of the Himalayas; this includes part of present-day Afghanistan as well as all of Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri Lanka.

Mythopoeic impulses during the time of Alexander the Great (356 BCE–323 BCE) associated the conqueror with Hercules, but W. J. Woodhouse observes that as his army moved eastward he began to be equated with Bacchus as well. Alexander made it as far as northwest India, leading to the belief that Bacchus was the conqueror of that land:The triumphant irresistible bursting of Alexander the Great into the secrets of the Far East naturally appealed to the imagination of his generation as a sort of fabled progress of Bacchus through those same regions. The exploits of Alexander it was that give birth to the legend of the conquest of India and the East by Dionysus, rather than the converse; and the imagination of court flatterers was exercised to provide divine prototypes of Alexander's achievements. Being himself reputed son of Zeus-Ammon, and Dionysos also being, in some stories, a son of Ammon, it was altogether suitable that Alexander should tread literally in the footsteps of his divine predecessor, and at last come upon that very city of Nysa which had existed in the imagination of so many generations as built by Dionysos for his wearied Bacchanals, and upon that same Mt. Mēros on which his troops had refreshed themselves amid its ivy and laurels. (p. 428, internal citation omitted, emphasis added)

Mēros is the ancient Greek for thigh. Mythopoeists of Alexander's time equated Meros with Meru, a mythical mountain that is considered the center of the universe in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain cosmology. The connection between Bacchus' birth from Jupiter's thigh and the name of this mountain proved irresistible. In The Anabasis of Alexander, the 2nd C CE historian Arrian relates the how Alexander reached Nysa and was greeted by its citizens. Arrian is rather skeptical that the Dionysos referred to is the god:In this country, lying between the rivers Cophen [Kabul] and Indus, which was traversed by Alexander, the city of Nysa is said to be situated. The report is, that its foundation was the work of Dionysus, who built it after he had subjugated the Indians. But it is impossible to determine who this Dionysus was, and at what time, or from what quarter he led an army against the Indians. For I am unable to decide whether the Theban Dionysus, starting from Thebes or from the Lydian Tmolus came into India at the head of an army, and after traversing the territories of so many warlike nations, unknown to the Greeks of that time, forcibly subjugated none of them except that of the Indians. But I do not think we ought to make a minute examination of the legends which were promulgated in ancient times about the divinity; for things which are not credible to the man who examines them according to the rule of probability, do not appear to be wholly incredible, if one adds the divine agency to the story. When Alexander came to Nysa the citizens sent out to him their president, whose name was Acuphis, accompanied by thirty of their most distinguished men as envoys, to entreat Alexander to leave their city free for the sake of the god. The envoys entered Alexander's tent and found him seated in his armour still covered with dust from the journey, with his helmet on his head, and holding his spear in his hand. When they beheld the sight they were struck with astonishment, and falling to the earth remained silent a long time. But when Alexander caused them to rise, and bade them be of good courage, then at length Acuphis began thus to speak: "The Nysaeans beseech thee, king, out of respect for Dionysus, to allow them to remain free and independent; for when Dionysus had subjugated the nation of the Indians, and was returning to the Grecian sea, he founded this city from the soldiers who had become unfit for military service, and were under his inspiration as Bacchanals, so that it might be a monument both of his wandering and of his victory, to men of after times; just as thou also hast founded Alexandria near mount Caucasus, and another Alexandria in the country of the Egyptians. Many other cities thou hast already founded, and others thou wilt found hereafter, in the course of time, inasmuch as thou hast achieved more exploits than Dionysus. The god indeed called the city Nysa, and the land Nysaea after his nurse Nysa. The mountain also which is near the city he named Meros (i.e. thigh), because, according to the legend, he grew in the thigh of Zeus. From that time we inhabit Nysa, a free city, and we ourselves are independent, conducting our government with constitutional order. And let this be to thee a proof that our city owes its foundation to Dionysus; for ivy, which does not grow in the rest of the country of India, grows among us." (V.1)

Pleased that he had reached as far as Dionysos, Alexander granted the Nysians their wish and allowed their city to remain "free and independent." He then took his army on a picnic to the fabled mountain:He was now seized with a strong desire of seeing the place where the Nysaeans boasted to have certain memorials of Dionysus. So he went to Mount Merus with the Companion cavalry and the foot guard, and saw the mountain, which was quite covered with ivy and laurel and groves thickly shaded with all sorts of timber, and on it were chases of all kinds of wild animals. The Macedonians were delighted at seeing the ivy, as they had not seen any for a long time; for in the land of the Indians there was no ivy, even where they had vines. They eagerly made garlands of it, and crowned themselves with them, as they were, singing hymns in honour of Dionysus, and invoking the deity by his various names. Alexander there offered sacrifice to Dionysus, and feasted in company with his companions. (V.2)

This city of Nysa has been identified with a couple of sites in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Ptolemy mentions a city named Nagara, also known as Dionysopolis; both this name and Nagara's location between the Cophen [Kabul] and Indus rivers make it a strong candidate. The exact location of Nagara is not known, but it is associated with an archaeological site known as Nagara Ghundi, about four miles from Jalalabad in Afghanistan. The present-day city of Nisatta in Pakistan, some 100 miles away from Jalalabad, is another viable candidate.

Some 300 years after Arrian (and 800 years after Alexander's time), the Hellenistic poet Nonnus wrote an epic poem, the Dionysiaca, which narrates the life of Dionysos, his conquest of India, and his return to the West. Nonnus, however, situates Nysa in Arabia.

References (except Wikipedia)

• Arrian. The Anabasis of Alexander. Trans. E. J. Chinnock. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1884. Wikisource. Accessed 27 March 2021.

• Ball, Warwick. "Nagara Ghundi." Archaeological Gazetteer of Afghanistan, n. 756. 1982. Cultural Property Training Institute, Afghanistan. aiamilitarypanel.org. Accessed 27 March 2021.

• Black, John. "Mount Meru: Hell and Paradise on One Mountain." 3 April 2013. ancient-origins.net. Accessed 27 March 2021.

• Homer. Iliad. Trans. Stanley Lombardo. Intro. Sheila Murnaghan. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997.

• ———. The Iliad. The Chicago Homer. Accessed 27 March 2021.

• "Nisatta." Jatland.com. Accessed 27 March 2021.

• Nonnus. Dionysiaca. Trans. W. H. D. Rowse. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1940–1942. 3 vols: one two three. Archive.org. Accessed 27 March 2021.

• Woodhouse, W. J. "Nysa". pp. 427–428. Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, ed. James Hastings. Vol. IX, Mundas–Phrygians. pp. 427–428. Google Books. Accessed 27 March 2021.

-- What is meant by “Nysa” in the Lusiads?, by literature.stackexchange.com

There is no other trace of the supposed western Gandaridae.