by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/25/21

Whether Menu or Menus in the nominative and Meno's in an oblique case, was the same personage with Minos [Minos was a mythical king in the island of Crete, the son of Zeus and Europa. He was famous for creating a successful code of laws; in fact, it was so grand that after his death, Minos became one of the three judges of the dead in the underworld. Minos, by Wikipedia], let others determine; but he must indubitably have been far older than the work, which contains his laws, and though perhaps he was never in Crete, yet some of his institutions may well have been adopted in that island, whence Lycurgus, a century or two afterwards, may have imported them to Sparta.

There is certainly a strong resemblance, though obscured and faded by time, between our Menu with his divine Bull, whom he names as Dherma himself, or the genius of abstract justice, and the Mneues of Egypt with his companion or symbol Apis; and, though we should be constantly on our guard against the delusion of etymological conjecture, yet we cannot but admit that Minos and Mneues, or Mneuis, have only Greek terminations, but that the crude noun is composed of the same radical letters both in Greek and in Sanscrit.'That Apis and Mneuis,' says the Analyst of ancient Mythology, ‘were both representations of some personage, appears from the testimony of Lycophron and his scholiast; and that personage was the same, who in Crete was styled Minos, and who was also represented under the emblem of the Minotaur; Diodorus, who confines him to Egypt, speaks of him by the title of the bull Mneuis, as the first lawgiver, and says, "That he lived after the age of the gods and heroes, when a change was made in the manner of life among men; that he was a man of a most exalted soul, and a great promoter of civil society, which he benefited by his laws; that those laws were unwritten, and received by him from the chief Egyptian deity Hermes, who conferred them on the world as a gift of the highest importance.” He was the same, adds my learned friend, with Menes, whom the Egyptians represented as their first king and principal benefactor, who first sacrificed to the gods, and brought about a great change in diet.’

If Minos, the son of Jupiter, whom the Cretans, from national vanity, might have made a native of their own island, was really the same person with Menu, the son of Brahma, we have the good fortune to restore, by means of Indian literature, the most celebrated system of heathen jurisprudence, and this work might have been entitled The Laws of Minos; but the paradox is too singular to be confidently asserted, and the geographical part of the book, with most of the allusions to natural history, must indubitably have been written after the Hindu race had settled to the south of Himalaya.

-- Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Menu, According to the Gloss of Culluca. Comprising the Indian System of Duties, Religious and Civil, Verbally translated from the original Sanscrit, With a Preface, by Sir William Jones

The Hindus themselves believe their own country, to which they give the vain epithets of Medhyama or Central, and Punyabhúmi, or the Land of Virtues, to have been the portion of Bharat, one of nine brothers, whose father had the dominion of the whole earth; and they represent the mountains of Himálaya as lying to the north, and, to the west, those of Vindhya, called also Vindian by the Greeks; beyond which the Sindhu runs in several branches to the sea, and meets it nearly opposite to the point of Dwáracà, the celebrated seat of their Shepherd God: in the south-east they place the great river Saravatya; by which they probably mean that of Ava, called also Airávati in parts of its course, and giving perhaps its ancient name to the gulf of Sabara. This domain of Bharat they consider as the middle of the Jambudwípa, which the Tibetians also call the Land of Zambu; and the appellation is extremely remarkable; for Jambu is the Sanskrit name of a delicate fruit called Jáman by the Muselmans, and by us rose-apple; but the largest and richest sort is named Amrita, or Immortal; and the Mythologists of Tibet apply the same word to a celestial tree bearing ambrosial fruit, and adjoining to four vast rocks, from which as many sacred rivers derive their several streams.

The inhabitants of this extensive tract are described by Mr. Lord with great exactness, and with a picturesque elegance peculiar to our ancient language: "A people, says he, presented themselves to mine eyes, clothed in linen garments somewhat low descending, of a gesture and garb, as I may say, maidenly and well nigh effeminate, or a countenance shy and somewhat estranged, yet smiling out a glozed and bashful familiarity. " Mr. Orme, the Historian of India, who unites an exquisite taste for every fine art with an accurate knowledge of Asiatic manners, observes, in his elegant preliminary Dissertation, that this "country has been inhabited from the earliest antiquity by a people, who have no resemblance, either in their figure or manners, with any of the nations contiguous to them," and that, "although conquerors have established themselves at different times in different parts of India, yet the original inhabitants have lost very little of their original character." The ancients, in fact, give a description of them, which our early travellers confirmed, and our own personal knowledge of them nearly verifies; as you will perceive from a passage in the Geographical Poem of Dionysius, which the Analyst of Ancient Mythology has translated with great spirit:To th' east a lovely country wide extends,

India, whose borders the wide ocean bounds;

On this the sun, new rising from the main,

Smiles pleas'd, and sheds his early orient beam.

Th' inhabitants are swart, and in their locks

Betray the tints of the dark hyacinth.

Various their functions; some the rock explore,

And from the mine extract the latent gold;

Some labor at the woof with cunning skill,

And manufacture linen; others shape

And polish iv'ry with the nicest care:

Many retire to rivers shoal, and plunge

To seek the beryl flaming in its bed,

Or glitt'ring diamond. Oft the jasper's found

Green, but diaphanous; the topaz too

Of ray serene and pleasing; last of all

The lovely amethyst, in which combine

All the mild shades of purple. The rich soil,

Wash'd by a thousand rivers, from all sides

Pours on the natives wealth without control.

Their sources of wealth are still abundant even after so many revolutions and conquests; in their manufactures of cotton they still surpass all the world; and their features have, most probably, remained unaltered since the time of Dionysius; nor can we reasonably doubt, how degenerate and abased so ever the Hindus may now appear, that in some early age they were splendid in art and arms, happy in government, wise in legislation, and eminent in various knowledge: but, since their civil history beyond the middle of the nineteenth century from the present time, is involved in a cloud of fables, we seem to possess only four general media of satisfying our curiosity concerning it; namely, first their Languages and Letters; secondly, their Philosophy and Religion; thirdly, the actual remains of their old Sculpture and Architecture; and fourthly, the written memorials of their Sciences and Arts.

-- Discourse III. On the Hindus, Discourses Delivered Before the Asiatic Society: And Miscellaneous Papers, on The Religion, Poetry, Literature, Etc. of the Nations of India, Delivered February 2, 1786, by Sir William Jones

P. 20-21: The AEtolians are said to have lived on the omphalos or umbilicus of Greece. [Liv. Hist. lib xxv. C. 18.] There was a place in Crete called omphalium, from an omphalos. [Callim. Hymn. In Jov. V. 42.] Sicily affords instances of such places. [Jacob Bryant. Myth. Vol. i. p. 11.] Many others also of ancient celebrity are noticed by different authors. The prists of the temple of Apollo at Delphi maintained farther, that their Mount Parnassus was not only the omphalos of Greece, but the Mesomphalso, the Meru of all the world. Such is the title given to it by the tragic poet Sophocles. [Oedip. Tyrann. V. 487.] In accordance with him, Pindar relates, in his fourth Pythian ode, that the oracle which obliged Jason to undertake the Argonautic expedition was uttered by the laurel-crowned priestess of Delphi, from the Mesomphalos of Mount Parnassus. [Pyth. Od. Iv. 129. ] Pausanias cites the authority of this poet, in confirmation of the assertion of the citizens of Delphi, that the omphalos, a figure of white stone, placed within the limits of their temple, and kept covered by a veil, was the exact mesomphalos, the middle of all the earth. [Pausan. Lib. X. c. 16, s. 2. Strab. Lib. Ix. P. 420. A. ] The stone thus covered in reverence, as it was pretended, clearly intimates the claim vindicated for these mesomphali. It was doubtless the same as the Phenician cone, sacred to Venus, and exhibited in the Sastra under the name of bhaga or yoni, as the sign of one of the lunar mansions. This emblem of fertility and production belongs to the ancient phallic worship, and is aptly placed in a spot which claims the title of the first birthplace of the human race. The same inference may be drawn from Ilium, the name of the citadel of Troy. The hero of the Aeneis conveyed Ilium and the conquered Penates into Italy. [ ] Ilium was the abode of the Penates, gods of Troy. Ila signifies the earth, in the Sanscrit. There are several circumstances which shew that the title of having been the birthplace of the first of mankind was asserted by the votaries of Mount Parnassus. The high and precipitous peaks of that mountain, the mysterious caves and the ceaseless streams, the mephitic vapours issuing from numerous cavities, all marked the place extraordinary. The numerous sacred structures comprised within the wide bounds of its heights gave to the whole of the place a close resemblance to the fabled features of Meru, the mesomphalos of India.

The learned analyst of ancient mythology, availing himself of his convertible radicals, has thought proper to maintain that sacred umbilical eminences derived their name from the oracular uses to which they served; that omphalos was a word compounded of the Greek ([x]) omphi, signifiying an oracular response, and el, a Hebrew word, signifying that the response was from a god. This might have been probable were it true that all these omphali were oracular. But it does not appear that all these eminences were so. This fact overturns his argument, and invites a farther enquiry concerning the derivation of the word….

P. 36: The god Horus of the Egyptian mythology was a personification of the sun, as some are pleased to affirm, but more properly of the earth, produced by Osiris, the active cause, on Isis, the passive agent in productive nature. According to Jamblichus, Horus was often represented by the figure of a man seated on the lotus. Other Egyptian symbols exhibit a frog, an amphibious creature, sitting on the flower, as though newly emerging from the water. In another, a beautiful young woman, a symbol of productive earth, is seated on the flower. The late traveler Belzoni, and others, have seen the like symbols still extant in several temples of the country. [Jacob Bryant. Myth. Vol. iii. P. 256. Belzoni’s Travels, p. 57.]

There have been various opinions concerning the true import of these symbols. The philosophers Jamblichus, Plutarch, and Porphyry, agree that they allude to the elements of earth and water, but wandering into refined disquisitions concerning nature moist and nature dry, they involve themselves in perplexing subtleties, and lose the plain truth while in pursuit of it. The same may be said of the English analyst of ancient mythology. He regards the symbols of Horus as referring to the general deluge and the ark of Noah: he regards the infant Horus seated on the calyx of the lotus as significant of the aged patriarch shut up in the ark. The improbability, if not the impossibility of this opinion, will perhaps appear when it is known, that the name of Noah, and of the miraculous assemblage of every kind of animal in the ark is never noticed in the records left by the heathen mythologists or historians. The true history of the general deluge is merged and lost in the heathen theories of the alternate destruction of the world by water and by fire, and of the restoration of his inhabiters from a few that escaped. Leaving therefore these fables as not meriting attention, the symbol of Horus on the calyx or flower of the lotus is again offered to notice….

P. 94: The learned analyst of ancient mythology affirms that the word Asia, [Jacob Bryant, vol. i. p. 31.] the name of a most important quarter of the globe, signifies the land of fire, for that it is compounded of the radicals [x] or is, and [x], [Etym. Magn. Ad voc.] aia, earth. The former of these radicals is the same as the Hebrew [x] aish, fire. The name was evidently given because fire and the sun were worshipped in all the regions of that continent known to the ancients. This element was a symbol of the male or generative power of Nature, adopted in opposition to the worship of Egypt, Europe, and the western regions, whose inhabitants pertinaciously adhered to their worship of water and the moon, symbols of the female or productive powers of Nature. The history of the Asiatic nations confirms this position. The Canaanites made their sons and their daughters pass through the fire unto Moloch. The Chaldees of Ur were especially distinguished by the same worship. The Persians of ancient ages, and the Parsis of modern, the disciples of Zoroaster, are eminently distinguished by the observance of rites performed in worship of the same element. The ancient Hyrcania received its name from the same worship, for which even the modern Balk and Bamian have long been noted. Even Hindosthan had her Suryavansa worshipping the sun and fire, in opposition to the Chandravansa worshipper of the moon and water. Such differences subsisted between the shepherd kings of Egypt, who built the pyramids, and the Egyptians, whom they compelled, with victorious insolence to labour as slaves at the mighty works. The purport of the name of the continent from whence they came proves that they were worshippers of the sun and fire, and that the pyramids were built for the worship of that element….

P. 155-156: The word obelisk signifies a spit; and, according to Herodotus, the name was given to the column because of the resemblance it had to that culinary instrument. A reference to such an ordinary object cannot be supposed to have been applied to a sacred structure, nor was it, for Pliny expressly declares that the word obelisk signifies a dedication to the sun. [‘Ita significatur nomine Aegyptio.’ Hist. Nat. lib. Xxxvi. C. 8.] How the name might bear this signification, the naturalist does not show. The Analyst of Ancient Mythology may by an use of his radicals supply the defect.

He affirms that the word obelisk is compounded of the radical monosyllables oph, alias ob, a serpent, and el, a designation of the Deity, and that the word indicated that the structure was dedicated to the serpent divine, which, he says, was the sun. [Jacob Bryant, Radicals, vol. i.] The grammarian Horapollo will guide to a better conclusion. When the Egyptians intend to signify the world, they draw the figure of a serpent taking into his mouth his own tail. Thus it appears that the serpent, ob, is the world, and consequently ob-el means the world divine, the world god. [Horapoll. Hiero. Lib. i. c. I. ] Hence it appears that the import of the word obelisk is the world sustained by the Deity. When two obelisks are placed on the two sides of the doors or entrances of temples, they are the same symbols as the Icin and Boaz of the temple of Solomon; when singly standing alone, the obelisk has the same general import, it signifies the power of the god to whom it is dedicated….

P. 286: The zealous Advocate for the religion of the Gospel seems to have known well the usual contents of these sacred arks; for the Christians, not being awed by the pretended sanctity of those fabrics intended to be secret mysteries, would not hesitate to look into them whenever an opportunity occurred. The Advocate, regarding the indignant scorn the contents of these arks, recites them in terms as follow: "Are they not," says he, "sprigs of sesamis, and little pyramids, and wool elaborately wrought, a cake with many knobs, handfuls of salt, together with a snake, used in the orgies of Bacchus? Are they not pomegranates? Are they not little hearts, little rods, sprigs of ivy, sweet cakes, and heads of poppies? These," says the scornful Advocate, "are their sacred things." [Clem. Alexand. Admon. ad Gent. p. 14. A.] The Analyst of Ancient Mythology admits that such things as these here recited, were the usual garniture of the sacred arks; but he shows, that every article had its peculiar symbolical meaning, and might have been available to good effects: but it is evident that much study must have been pratised, before such effects could have wrought upon the minds of the pagan votaries; the excess of meaning rendered, as it ever must, the import of the many symbols utterly inefficient. The study of the symbols was never undertaken; their use was unknown, and they appeared to be really useless and even ridiculous; the banter of the Christian Advocate became irresistible, and the pagan, ashamed of his old mythology, gave heed to the evidences of truth, and became a convert to the Christian faith.

This effect ensuing from the argument of the Christian Advocate, affords a useful warning in regard to the use of symbols; it shews that when the symbols are numerous they become uninstructive, and even injurious to the interests of truth. Of the articles, the usual furniture of the sacred arks of the pagans, it must be observed, that every one of them had a symbolical meaning calculated to afford the most valuable instruction; the whole rightly understood would have formed a most excellent lecture in natural religion -- would have taught the same truths as man is invited to seek and secure by a pious attention given to the works of the Creator. This will be sufficiently evident from the authorities and observations of the learned and ingenious Bryant, who shews that idolatory depended entirely on the symbolical use of natural objects. Had idolaters confined themselves within that limit, they had not been transgressors of the divine law; but when they bowed before the symbol, it soon became a god; they they trod the paths of error. The Reformers of the sixteenth century, aware of this tendency of the use of symbols, proscribed them altogether; destroying that which might be valuably useful, because it had been abused. True religion is most assuredly spiritual; but there are few who can become spiritual without the aid of objects of sense, and therefore the use of symbols, when confined within proper bounds, will ever be approved the true friend of man. The same may be said of the application of heathen structures to the purposes of Christian worship. All of them were symbolical: but when it is shewn that they all received their symbolical forms by a regular descent from the primal and patriarchal altar, in form most probably the same as the altar raised by the Deity for the use of many when he planted the Garden of Eden, the forms of the sacred structures of even the heathen may be said to have had a divine origin. This fully justifies the adoption of the forms of heathen sacred structures, and the application of even heathen symbols, to purposes altogether and purely Christian. After these remarks, digressive perhaps, but not altogether foreign to the subject, the attention is again invited to the history of the sacred arks of heathenism.

The religion of the Celts, better known as the religion of the Druids, was, during the ages which preceded the age of recorded history, the form which idolatry bore in almost all, if not actually in all parts of the world. Rites performed in caves formed a part of the religious duties of that mode of religion; and the use of the kist-vaen or sacred ark was inseparable from, and indispensably necessary to, the performance of some of the most solemn mysteries.

-- Naology: or, A Treatise on the Origin, Progress, and Symbolical Import of The Sacred Structures of the Most Eminent Nations and Ages of the World, by John Dudley, M.A., Vicar of Humberston and of Sileby, Leicestershire, sometime Fellow and Tutor of Clare Hall, Cambridge, and Author of an Essay on the Identity of the River Niger and the Nile, 1846

RADICALS.

Πειθους δ' εστι κελευθος, αληθειη γαρ οπηδει.——PARMENIDES.

The materials, of which I purpose to make use in the following inquiries, are comparatively few, and will be contained within a small compass. They are such as are to be found in the composition of most names, which occur in antient mythology: whether they relate to Deities then reverenced; or to the places, where their worship was introduced. But they appear no where so plainly, as in the names of those places, which were situated in Babylonia and Egypt. From these parts they were, in process of time, transferred to countries far remote; beyond the Ganges eastward, and to the utmost bounds of the Mediterranean west; wherever the sons of Ham under their various denominations either settled or traded. For I have mentioned that this people were great adventurers; and began an extensive commerce in very early times. They got footing in many parts; where they founded cities, which were famous in their day. They likewise erected towers and temples: and upon headlands and promontories they raised pillars for sea-marks to direct them in their perilous expeditions. All these were denominated from circumstances, that had some reference to the religion, which this people professed; and to the ancestors, whence they sprung. The Deity, which they originally worshipped, was the Sun. But they soon conferred his titles upon some of their ancestors: whence arose a mixed worship. They particularly deified the great Patriarch, who was the head of their line; and worshipped him as the fountain of light: making the Sun only an emblem of his influence and power. They called him Bal, and Baal: and there were others of their ancestry joined with him, whom they styled the Baalim. Chus was one of these: and this idolatry began among his sons. In respect then to the names, which this people, in process of time, conferred either upon the Deities they worshipped, or upon the cities, which they founded; we shall find them to be generally made up of some original terms for a basis, such as Ham, Cham, and Chus: or else of the titles, with which those personages were, in process of time, honoured. These were Thoth, Men or Menes, Ab, El, Aur, Ait, Ees or Ish, On, Bel, Cohen, Keren, Ad, Adon, Ob, Oph, Apha, Uch, Melech, Anac, Sar, Sama, Samaïm. We must likewise take notice of those common names, by which places are distinguished, such as Kir, Caer, Kiriath, Carta, Air, Col, Cala, Beth, Ai, Ain, Caph, and Cephas. Lastly are to be inserted the particles Al and Pi; which were in use among the antient Egyptians.

Of these terms I shall first treat; which I look upon as so many elements, whence most names in antient mythology have been compounded; and into which they may be easily resolved: and the history, with which they are attended, will, at all times, plainly point out, and warrant the etymology.

-- A New System; or, an Analysis of Ancient Mythology. Volume I., by Jacob Bryant

Maurya ... it seems that Chandragupta went by that name, particularly in the west; for he is known to Arabian writers by the name of Mur, according to the Nubian geographer, who says that he was defeated and killed by Alexander; for these authors supposed that this conqueror crossed the Ganges; and it is also the opinion of some ancient historians in the west.

-- Essay III. Of the Kings of Magadha; their Chronology, by Captain Wilford, Asiatic Researches, Volume 9, 1809. pgs. 94-100.

In "A Descent Into the Malestrom," before the old mariner's confrontation with the whirlpool, the uninitiated narrator remarks on the prospect: "I looked dizzily, and beheld a wide expanse of ocean, whose waters were so inky a hue as to bring to mind the Nubian geographer's account of the Mare Tenebrarum."1 [The Complete Works of Edgar Allan Poe, ed. James A. Harrison (New York, 1902/1965), II, 226-227. All other references to this edition will be noted in the text by volume and page number.] In Burton Pollin's Dictionary of Names and Titles in Poe's Collected Works, the identity of this geographical authority is left open to question. Hanna, Claudius Ptolemy, and Idrisi have been mentioned as possibilities.2 [Pollin mentions Idrisi and Claudius Ptolemy in Dictionary (New York, 1968), p. 68. Admitting uncertainty, T.O. Mabbott mentions Hanno and Idresi in Selected Poetry and Prose of Edgar Allan Poe (New York, 1951), p. 421.] The allusion is of more than trifling importance, since Poe recast it in "Eleonora," the preface to "Mellonta Tauta," and Eureka. These four references indicate a singular fascination with the geographer and his descriptive account. In each case, Poe's source was Jacob Bryant's A New System; or, An Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1807).3 [London, 1807.] The treatment of the Nubian geographer in Bryant's work clarifies a significant allusion, invites a re-evaluation of the sources of "A Descent into the Maelstrom," and adds to an understanding of the image patterns in the tale.

While the sources of "A Descent into the Maelstrom" have received fairly rigorous attention4 [See Adolph B. Benson, "Scandinavian References in the Works of Edgar Allan Poe," Journal of English and Germanic Philology, XL (Jan., 1941), 73-90; Arlin Turner, "Sources of Poe's 'A Descent into the Maelstrom,'" Journal of English and Germanic Philology, XLVI (July, 1947), 298-301; William T. Bandy, "New Light on a Source of Poe's 'A Descent into the Maelstrom,'" American Literature, XXIV (Jan, 1953), 534-537; Margaret J. Yonce, "The Spiritual Descent into the Maelstrom: A Debt to "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,'" Poe Newsletter, II (April, 1969), 26-29; and Carroll D. Laverty, "Science and Pseudo-Science in the Writings of Edgar Allan Poe" (Unpublished dissertation, Duke University, 1951), pp. 178-179.] allowance must be made for Bryant's in-

-- Notes: Poe's Nubian Geographer, by Kent Ljungquist, Bluefield College, American Literature, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Mar., 1976), pp. 73-75 (3 pages), Published By: Duke University Press

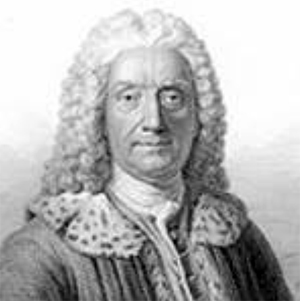

Jacob Bryant

Born: 1715, Plymouth, Devon

Died: 14 November 1804 (aged 88–89)

Nationality: British

Occupation: scholar, mythographer

Jacob Bryant (1715–1804) was an English scholar and mythographer, who has been described as "the outstanding figure among the mythagogues who flourished in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries."[1]

Life

Bryant was born at Plymouth. His father worked in the customs there, but was afterwards moved to Chatham. Bryant was first sent to a school near Rochester, and then to Eton College. In 1736 he was elected to a scholarship at King's College, Cambridge, where he took his degrees of B.A. (1740) and M.A. (1744), later being elected a fellow.[2] He returned to Eton as private tutor to the Duke of Marlborough. In 1756 he accompanied the duke, who was master-general of ordnance and commander-in-chief of the forces in Germany, to the Continent as private secretary. He was rewarded by a lucrative appointment in the Board of Ordnance, which allowed him time to indulge his literary tastes.

The Duke of Marlborough, by George Romney.

George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough, KG, PC, FRS (26 January 1739 – 29 January 1817), styled Marquess of Blandford until 1758, was a British courtier, nobleman, and politician from the Spencer family. He served as Lord Chamberlain between 1762 and 1763 and as Lord Privy Seal between 1763 and 1765. He is the great-great-great grandfather of Sir Winston Churchill....

Marlborough entered the Coldstream Guards in 1755 as an Ensign, becoming a Captain with the 20th Regiment of Foot the following year. After inheriting the dukedom in 1758, Marlborough took his seat in the House of Lords in 1760, becoming Lord-Lieutenant of Oxfordshire in that same year. The following year, he bore the sceptre with the cross at the coronation of George III. In 1762, he was made Lord Chamberlain as well as a Privy Counsellor, and after a year resigned this appointment to become Lord Privy Seal, a post he held until 1765. An amateur astronomer, he built a private observatory at his residence, Blenheim Palace. He kept up a lively scientific correspondence with Hans Count von Brühl, another aristocratic dilettante in astronomy.

The Duke was made a Knight of the Garter in 1768, and was elected to the Royal Society in 1786.

-- George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough, by Wikipedia

He was twice offered the mastership of Charterhouse school, but turned it down.

Bryant died on 14 November 1804 at Cippenham near Windsor. He left his library to King's College, having previously made some valuable presents from it to the king and the Duke of Marlborough. He bequeathed £2000 to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, and £1000 for the use of the retired collegers of Eton.

United Society Partners in the Gospel (USPG) is a United Kingdom-based charitable organization (registered charity no. 234518).

It was first incorporated under Royal Charter in 1701 as the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) as a high church missionary organization of the Church of England and was active in the Thirteen Colonies of North America....

Foundation and mission work in North America

In 1700, Henry Compton, Bishop of London (1675–1713), requested the Revd Thomas Bray to report on the state of the Church of England in the American Colonies. Bray, after extended travels in the region, reported that the Anglican church in America had "little spiritual vitality" and was "in a poor organizational condition". Under Bray's initiative, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts was authorised by convocation and incorporated by Royal Charter on 16 June 1701. King William III issued a charter establishing the SPG as "an organisation able to send priests and schoolteachers to America to help provide the Church's ministry to the colonists". The new society had two main aims: Christian ministry to British people overseas; and evangelization of the non-Christian races of the world.

The society's first two missionaries, graduates of the University of Aberdeen, George Keith and Patrick Gordon, sailed from England for North America on 24 April 1702. By 1710 the Society's charter had expanded to include work among enslaved Africans in the West Indies and Native Americans in North America. The SPG funded clergy and schoolmasters, dispatched books, and supported catechists through annual fundraising sermons in London that publicized the work of the mission society. Queen Anne was a noted early supporter, contributing her own funds and authorizing in 1711 the first of many annual Royal Letters requiring local parishes in England to raise a "liberal contribution" for the Society's work overseas...

The SPG clergy were ordained, university-educated men, described at one time by Thomas Jefferson as "Anglican Jesuits." They were recruited from across the British Isles and further afield; only one third of the missionaries employed by the Society in the 18th century were English. Included in their number such notable individuals as George Keith, and John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, originally a movement within the Anglican Church.

West Indies

Through a charitable bequest received in 1710, aimed at establishing Codrington College, the SPG became a significant slave owner in Barbados in the 18th and early 19th centuries. With the aim of supplying funding for the college, the Society was the beneficiary of the forced labour of thousands of enslaved Africans on the Codrington Plantations. Many of the slaves died in captivity from such diseases as dysentery and typhoid, after being weakened by overwork.

Although many educational institutions of the period, such as All Souls College, Oxford and Harvard University in Massachusetts benefitted from charitable bequests made by slave owners and slave traders, the ownership of the Codrington Plantations by the SPG and the Church of England generated considerable adverse controversy. In 1783, Bishop Beilby Porteus, an early proponent of abolitionism, used the occasion of the SPG's annual anniversary sermon to highlight the conditions at the Codrington Plantations and called for the SPG to end its connection with slave trade. The SPG did not relinquish its slave holdings in Barbados for decades, not until after the introduction in Parliament of the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

At the February 2006 meeting of the General Synod of the Church of England, attendees commemorated the church's role in helping to pass the Slave Trade Act of 1807 to abolish the Atlantic trade. Delegates also voted unanimously to apologise to the descendants of slaves for the church's long involvement in and support of the slave trade and the institution. Tom Butler, Bishop of Southwark, confirmed in a speech before the vote, that the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts had owned the Codrington Plantations...

Global expansion

The Society established mission outposts in Canada in 1759, Australia in 1793, and India in 1820. It later expanded outside the British Empire to China in 1863, Japan in 1873, and Korea in 1890. By the middle of the 19th century, the Society's work was focused more on the promotion and support of indigenous Anglican churches and the training of local church leadership, than on the supervision and care of colonial and expatriate church congregations

-- United Society Partners in the Gospel, by Wikipedia

Works

His chief works were A New System or Analysis of Ancient Mythology[3] (1774–76, and later editions), Observations on the Plain of Troy (1795), and Dissertation concerning the Wars of Troy (1796). He also wrote on theological, political and literary subjects.

Mythographer

Bryant saw all mythology as derived from the Hebrew Scriptures, with Greek mythology arising via the Egyptians.[4] The New System attempted to link the mythologies of the world to the stories recorded in Genesis. Bryant argued that the descendants of Ham had been the most energetic, but also the most rebellious peoples of the world and had given rise to the great ancient and classical civilisations. He called these people "Amonians", because he believed that the Egyptian god Amon was a deified form of Ham. He argued that Ham had been identified with the sun, and that much of pagan European religion derived from Amonian sun worship.

John Richardson was Bryant's chief opponent, in the preface to his Persian Dictionary. In an anonymous pamphlet, An Apology, Bryant defended and reaffirmed his opinions. Richardson then revised the dissertation on languages prefixed to the dictionary, and added a second part: Further Remarks on the New Analysis of Ancient Mythology (1778). Bryant also wrote a pamphlet in answer to Daniel Wyttenbach of Amsterdam, about the same time.[5] Sir William Jones frequently mentions Bryant's model, accepting parts of it and criticising others, particularly his highly conjectural etymologies. He referred to the New System as "a profound and agreeable work", adding that he had read it through three times "with increased attention and pleasure, though not with perfect acquiescence in some other less important parts of his plausible system".[6]

Bryant in the New System acknowledges help from William Barford.[7]

A Latin dissertation of Barford's on the 'First Pythian' is published in Henry Huntingford's edition of Pindar's works, to which is appended a short life of the author, a list of his works, and a eulogium of his learning. The list consists of poems on various political events in Latin and Greek, written in his capacity of public orator, a Latin oration at the funeral of William George, provost of King's College, 1756, and a Concio ad Clerum, 1784, written after his installation as canon of Canterbury.

-- William Barford, by Wikipedia

His theories are widely credited as an influence on the mythological system of William Blake, who had worked in his capacity as an engraver on the illustrations to Bryant's New System.

Classical scholar

In his books on Troy, Bryant endeavoured to show that the existence of Troy and the Greek expedition were purely mythological, with no basis in real history. In 1791, Andrew Dalzel translated a work of Jean Baptiste LeChevalier as Description of the Plain of Troy.[8] It provoked Bryant's Observations upon a Treatise ... (on) the Plain of Troy (1795) and A Dissertation concerning the War of Troy (1796?). A fierce controversy resulted, with Bryant attacked by Thomas Falconer, John Morritt, William Vincent, and Gilbert Wakefield.[5]

Other works

• Bryant's first work was Observations and Enquiries relating to various parts of Ancient History, ... the Wind Euroclydon, the island Melite, the Shepherd Kings, (Cambridge, 1767). Bryant attacked the opinions of Bochart, Beza, Grotius, and Bentley.[5]

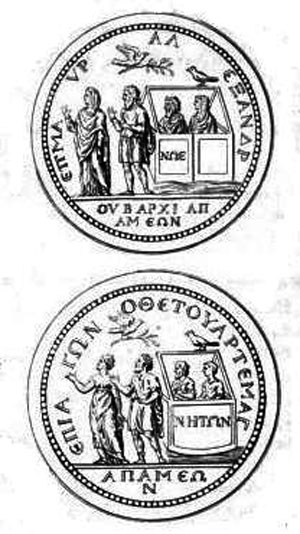

• When his account of the Apamean medal was disputed in the Gentleman's Magazine, Bryant defended himself in Apamean Medal and of the Inscription ΝΩΕ, London, 1775. Joseph Hilarius Eckhel upheld his views, but Daines Barrington and others opposed him in the Society of Antiquaries of London.[5]

The Apamean medal

• After his friend Robert Wood died in 1771, Bryant edited one of his works as An Essay on the Original Genius and Writings of Homer, with a Comparative View of the Troade (1775).

• Vindiciæ Flavianæ: a Vindication of the Testimony of Josephus concerning Jesus Christ (1777) was anonymous; the second edition, with Bryant's name, was in 1780. The sequel was A Farther Illustration of the Analysis (1778). This work influenced Joseph Priestley.[5]

Joseph Priestley FRS (24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist who published over 150 works. He has historically been credited with the independent discovery of oxygen in 1774 by the thermal decomposition of mercuric oxide, having isolated it. Although Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele also has strong claims to the discovery, Priestley published his findings first. Scheele discovered it by heating potassium nitrate, mercuric oxide, and many other substances about 1772.

During his lifetime, Priestley's considerable scientific reputation rested on his invention of carbonated water, his writings on electricity, and his discovery of several "airs" (gases), the most famous being what Priestley dubbed "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen). Priestley's determination to defend phlogiston theory and to reject what would become the chemical revolution eventually left him isolated within the scientific community.

Priestley's science was integral to his theology, and he consistently tried to fuse Enlightenment rationalism with Christian theism. In his metaphysical texts, Priestley attempted to combine theism, materialism, and determinism, a project that has been called "audacious and original". He believed that a proper understanding of the natural world would promote human progress and eventually bring about the Christian millennium. Priestley, who strongly believed in the free and open exchange of ideas, advocated toleration and equal rights for religious Dissenters, which also led him to help found Unitarianism in England. The controversial nature of Priestley's publications, combined with his outspoken support of the French Revolution, aroused public and governmental suspicion; he was eventually forced to flee in 1791, first to London and then to the United States, after a mob burned down his Birmingham home and church. He spent his last ten years in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania.

A scholar and teacher throughout his life, Priestley also made significant contributions to pedagogy, including the publication of a seminal work on English grammar and books on history, and he prepared some of the most influential early timelines. These educational writings were among Priestley's most popular works. It was his metaphysical works, however, that had the most lasting influence, being considered primary sources for utilitarianism by philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and Herbert Spencer.

-- Joseph Priestley, by Wikipedia

• An Address to Dr. Priestley ... upon Philosophical Necessity (1780); Priestley printed a reply the same year.[5]

• Bryant was a believer in the authenticity of Thomas Chatterton's fabrications. Chatterton had created poems written in mock Middle English and had attributed them to Thomas Rowley, an imaginary monk of the 15th century. When Thomas Tyrwhitt issued his work The Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others,' Bryant with Robert Glynn followed with his Observations on the Poems of Thomas Rowley in which the Authenticity of those Poems is ascertained (2 vols., 1781).[5]

• Gemmarum Antiquarum Delectus (1783) was privately printed at the expense of the Duke of Marlborough, with engravings by Francesco Bartolozzi. The first volume was written in Latin by Bryant, and translated into French by Matthew Maty; the second by William Cole, with the French by Louis Dutens.[5]

• On the Zingara or Gypsey Language (1785) was read by Bryant to the Royal Society, and printed in the seventh volume of Archæologia.[5]

• A disquisition On the Land of Goshen, written about 1767, was published in William Bowyer's Miscellaneous Tracts, 1785.[5]

• A Treatise on the Authenticity of the Scriptures (1791) was anonymous; second edition, with author's name, 1793; third edition, 1810. This work was written at the instigation of the Dowager Countess Pembroke, daughter of his patron, and the profits were given to the hospital for smallpox and inoculation.[5]

• Observations on a controverted passage in Justyn Martyr; also upon the "Worship of Angels", London, 1793.[5]

• Observations upon the Plagues inflicted upon the Egyptians, with maps, London, 1794.[5]

• The Sentiments of Philo-Judæus concerning the Logos or Word of God (1797).

• A treatise against Tom Paine.[5]

• 'Observations upon some Passages in Scripture' (relating to Balaam, Joshua, Samson, and Jonah), London, 1803.[5]

A projected work on the Gods of Greece and Rome was not produced by his executors. Some of his humorous verse in Latin and Greek was published.[5]

References

1. S. Foster Damon, A Blake Dictionary (1965), article on Bryant.

2. "Bryant, Jacob (BRNT736J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

3. Foster: Opinionated and peppery, unhampered by modern standards of scholarship, and indulging in a fantastic philology, Bryant was of the Age of Reason in that he sought to reduce all fables to common sense.

4. John Charles Whale; Stephen Copley (1992). Beyond Romanticism: New Approaches to Texts and Contexts, 1780–1832. Routledge, Chapman & Hall, Incorporated. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-415-05201-6. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

5. Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). "Bryant, Jacob" . Dictionary of National Biography. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

6. Young, Brian, "Christianity, histopry and India, 1790-1820", Collini, et al, History, Religion, and Culture: British Intellectual History 1750-1950, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p.98.

7. Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1885). "Barford, William" . Dictionary of National Biography. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

8. Jean Baptiste LeChevalier (1791). Description of the plain of Troy, tr., with notes and illustr. by A. Dalzel. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

Attribution

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1886). "Bryant, Jacob". Dictionary of National Biography. 7. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons – via Wikisource.

External links

• Works by Jacob Bryant at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Jacob Bryant at Internet Archive

**************************

Jacob Bryant

by Dictionary of National Biography

1885-1900

BRYANT, JACOB (1715–1804), antiquary, was born in 1715 at Plymouth, where his father was an officer in the customs, but before his seventh year was removed to Chatham. The Rev. Samuel Thornton of Luddesdon, near Rochester, was his first schoolmaster, and in 1730 he was at Eton. Elected to King's College, Cambridge, in 1736, he took his degrees, B.A. in 1740, M.A. in 1744, and he became a fellow of his college. He was first private tutor to Sir Thomas Stapylton, and then to the Marquis of Blandford, afterwards duke of Marlborough, and his brother, Lord Charles Spencer. In 1756 he was appointed secretary to the Duke of Marlborough, master-general of ordnance, and went with him to Germany, where the latter died while commander-in-chief. At the same time Bryant held an office in the ordnance department worth 1,400l. a year. Mr. Hetherington made him his executor with a legacy of 3,000l., and the Marlborough family allowed him 1,000l. a year, gave him rooms at Blenheim, and the use of the famous library. He twice refused the mastership of the Charterhouse, although once actually elected. His first work was 'Observations and Enquiries relating to various parts of Ancient History, ... the Wind Euroclydon, the island Melite, the Shepherd Kings,' &c. (Cambridge, 1767, 4to), in which he attacked the opinions of Bochart, Beza, Grotius, and Bentley. He next published the work with which his name is chiefly associated, 'A New System or an Analysis of Ancient Mythology,' with plates, London, 1774, two vols. 4to; second edition, 1775, 4to; and vol. iii. 1776, 4to. His research is remarkable, but he had no knowledge of oriental languages, and his system of etymology was puerile and misleading. The third edition, in six vols. 8vo, was published in 1807. John Wesley published an abbreviation of the first two vols, of the 4to edition. Richardson, assisted by Sir William Jones, was Bryant's chief opponent in the preface to his 'Persian Dictionary.' In an anonymous pamphlet, 'An Apology,' &c., of which only a few copies were printed for literary friends, Bryant sustained his opinions, whereupon Richardson revised the dissertation on languages prefixed to the dictionary, and added a second part: 'Further Remarks on the New Analysis of Ancient Mythology,' &c., Oxford, 1778, 8vo. Bryant also wrote a pamphlet in answer to Wyttenbach, his Amsterdam antagonist, about the same time. His account of the Apamean medal being disputed in the 'Gentleman's Magazine,' he defended himself by publishing 'A Vindication of the Apamsean Medal, and of the Inscription Nωη,' London, 1775, 4to. Eckhel, the great medallist, upheld his views, but Daines Barrington and others strongly opposed him at the Society of Antiquaries (Archæologia, ii.) In 1775, four years after the death of his friend, Mr. Robert Wood, he edited, 'with his improved thoughts,' 'An Essay on the Original Genius and Writings of Homer, with a Comparative View of the Troade,' London, 4to. The first edition, of seven copies only, was a superb folio, privately printed in 1769. Bryant published in 1777, without his name, 'Vindiciæ Flavianæ: a Vindication of the Testimony of Josephus concerning Jesus Christ,' London, 8vo; second edition, with author's name, London, 1780, 8vo. This work converted even Dr. Priestley to his opinions. In 1778 he published 'A Farther Illustration of the Analysis ... ,' pp. 100, 8vo (no place). He next published 'An Address to Dr. Priestley ... upon Philosophical Necessity,' London, 1780, 8vo, to which Priestley printed a rejoinder the same year. When Tyrwhitt issued his work 'The Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others,' Bryant, assisted by Dr. Glynn of King's College, Cambridge, followed with his 'Observations on the Poems of Thomas Rowley in which the Authenticity of those Poems is ascertained,' 2 vols., London, 1781, 8vo, a work that did not add to his reputation. In 1783, at the expense of the Duke of Marlborough, the splendid folio work on the Marlborough gems, 'Gemmarum Antiquarum Delectus,' was privately printed, with exquisite engravings by Bartolozzi. The first volume was written in Latin by Bryant, and translated into French by Dr. Maty; the second by Dr. Cole, prebendary of Westminster, and the French by Dr. Dutens. In 1785 a paper 'On the Zingara or Gypsey Language' was read by Bryant to the Royal Society, and printed in the seventh volume of 'Archæologia.' He next published, without his name, 'A Treatise on the Authenticity of the Scriptures,' London, 1791, 8vo; second edition, with author's name, Cambridge, 1793, 8vo; third edition, Cambridge, 1810, 8vo. This work was written at the instigation of the Dowager Countess Pembroke, daughter of his patron, and the profits were given to the hospital for smallpox and inoculation. Then followed 'Observations on a controverted passage in Justyn Martyr; also upon the 'Worship of Angels,' London, 1793, 4to; 'Observations upon the Plagues inflicted upon the Egyptians,' with maps, London, 1794, 8vo, pp. 440. Professor Dalzel's publication in 1794 of M. Chevalier's 'Description of the Plain of Troy' elicited Bryant's fearless work, 'Observations upon a Treatise ... (on) the Plain of Troy,' Eton, 1795, 4to, and 'A Dissertation concerning the War of Troy' (? 1796), 4to, pp. 196; second edition, corrected, with his name, London, 1799, 4to. Bryant contended that no such war was ever undertaken, and no such city as the Phrygian Troy ever existed; but he won no converts, and was attacked on all sides by such men as Dr. Vincent, Gilbert Wakefield, Falconer, and Morritt. In 1799 he published 'An Expostulation addressed to the British Critic,' Eton, 4to, mistaking his antagonist Vincent for Wakefield, and for the first time losing his temper and using strong and unjustifiable language. His next work, 'The Sentiments of Philo-Judæus concerning the Logos or Word of God,' Cambridge, 1797, 8vo, pp. 290, is full of fanciful speculation which detracted from his fame. In addition to these numerous works he published a treatise against the doctrines of Thomas Paine, and a disquisition 'On the Land of Goshen,' written about 1767, was published in Mr. Bowyer's 'Miscellaneous Tracts,' 1785, 4to; and his literary labours closed with 'Observations upon some Passages in Scripture' (relating to Balaam, Joshua, Samson, and Jonah), London, 1803, 4to. It is apparent, however, from the preface to Faber's 'Mysteries of the Cabiri,' 1803, 8vo, that Bryant had written a kind of supplement to his 'Analysis of Ancient Mythology,' a work on the Gods of Greece and Rome, which, in a letter to Faber, he said, 'may possibly be published after his death,' but his executors have never produced the work. Some of his humorous poems are found in periodicals of his time, but are of little interest except as examples of elegant Latin and Greek verse.

Bryant, who was never married, had resided a long time before his death at Cypenham, in Farnham Royal, near Windsor. There the king and queen often visited him, and the former passed hours alone with him enjoying his conversation. A few months before his end came he said to his nephew, 'All I have written was with one view to the promulgation of truth, and all I have contended for I myself have believed.' While reaching a book from a shelf he hurt his leg, mortification set in, and he died 14 Nov. 1804. His remains were interred in his own parish church, beneath the seat he had occupied there, and a monument was erected to his memory near the same.

In person he was a delicately formed man of low stature; late in life he was of sedentary habits, but in his younger days he was very agile and fond of field sports, and once by swimming saved the life of Barnard, afterwards provost of Eton. To the last he was attached to his dogs, and kept thirteen spaniels at a time. He was temperate, courteous, and generous. His conversation was very pleasing and instructive, with a vein of quiet humour. There are many pleasant anecdotes of him in Madame d'Arblay's 'Diary and Letters.' In his lifetime his curious collection of Caxtons went to the Marquis of Blandford, and many valuable books were sent from his library to King George III. The classical part of his library was bequeathed to King's College, Cambridge; 2,000l. to the Society for Propagating the Gospel, 1,000l. to superannuated collegers of Eton School, 500l. to the poor of Farnham Royal, &c.

The English portrait prefixed to the octavo edition of his work on ancient mythology is from a drawing by the Rev. J. Bearblock, taken in 1801. All literary authorities, and his monument, give the year of his birth as above, but in the Eton register-book he is entered as '12 years old in 1730.'

[Bryant's Works; Nichols's Lit. Anecd. i. 672, iii. 7, 42, 84, 148, 515, iv. 348, 608, 667, v. 231, viii. 112, 129, 218, 249, 427, 505, 531, 540, 552, 614, 635, ix. 198, 290, 577, 714; Nichols's Lit. Illust. ii. 651, iii. 132, 218, 772, vi. 36, 249, 670, vii. 401, 404, 469; Gent. Mag. xlviii. 210, 625; New Monthly Mag. i. 327; Archæologia, iv. 315, 331, 347, vii. 387; Cole's MSS., Brit. Mus. vols. xx. xxiii.; Martin's Privately Printed Books, 85; Mme. d'Arblay's Diary, 1846, iii. 117, 228, 323, 375, 401.]