by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/29/20

Germaine Luise Krull (20 November 1897 – 31 July 1985) was a photographer, political activist, and hotel owner.[1] Her nationality has been categorized as German,[2] French,[3] and Dutch,[4] but she spent years in Brazil, Republic of the Congo, Thailand, and India.[1] Described as "an especially outspoken example" of a group of early 20th-century female photographers who "could lead lives free from convention", she is best known for photographically-illustrated books such as her 1928 portfolio Métal.[5]

Biography

Krull was born in Posen-Wilda, a district of Posen (then in Germany; now Poznań, Poland), of an affluent German family.[1]:5–6 In her early years, the family moved around Europe frequently; she did not receive a formal education, but instead received homeschooling from her father, an accomplished engineer and a free thinker (whom some characterized as a "ne'er-do-well").[1]:6–7 Her father let her dress as a boy when she was young, which may have contributed to her ideas about women's roles later in her life.[6] In addition, her father's views on social justice "seem to have predisposed her to involvement with radical politics."[6]

Between 1915 and 1917 or 1918 she attended the Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie, a photography school in Munich, Germany, at which Frank Eugene's teaching of pictorialism in 1907–1913 had been influential.[1]:9–13 She opened a studio in Munich in approximately 1918, took portraits of Kurt Eisner and others, and befriended prominent people such as Rainer Maria Rilke, Friedrich Pollock, and Max Horkheimer.[1]:13–16

Krull was politically active between 1918 and 1921. In 1919 she switched from the Independent Socialist Party of Bavaria to the Communist Party of Germany, and was arrested and imprisoned for assisting a Bolshevik emissary's attempted escape to Austria.[1]:18–22 She was expelled from Bavaria in 1920 for her Communist activities, and traveled to Russia with lover Samuel Levit.[1]:24–25 After Levit abandoned her in 1921, Krull was imprisoned as an "anti-Bolshevik" and expelled from Russia.[1]:26–27

She lived in Berlin between 1922 and 1925 where she resumed her photographic career.[1]:29–43 She and Kurt Hübschmann (later to be known as Kurt Hutton) worked together in a Berlin studio between 1922 and 1924. Among other photographs Krull produced in Berlin were a series of nudes (recently disparaged by an unimpressed 21st-century critic as "almost like satires of lesbian pornography"[6]).

Having met Dutch filmmaker and communist Joris Ivens in 1923, she moved to Amsterdam in 1925.[1]:40–43 After Krull returned to Paris in 1926, Ivens and Krull entered into a marriage of convenience between 1927 and 1943 so that Krull could hold a Dutch passport and could have a "veneer of married respectability without sacrificing her autonomy."[1]:67–70[7]

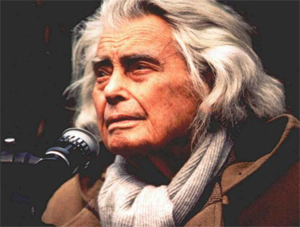

Georg Henri Anton "Joris" Ivens (18 November 1898 – 28 June 1989) was a Dutch documentary filmmaker and propagandist. Among the notable films he directed or co-directed are A Tale of the Wind,...A Tale of the Wind is a 1988 French film directed by Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan. It is also known as A Wind Story. It stars Ivens as he travels in China and tries to capture winds on film, while he reflects on his life and career. The film blends real and fictional elements; it ranges from documentary footage to fantastical dream sequences and Peking opera. It was Ivens' last film.

-- A Tale of the Wind, by Wikipedia

The Spanish Earth,...The Spanish Earth is a 1937 propaganda film made during the Spanish Civil War in support of the democratically elected Republicans, whose forces included a wide range from the political left like communists, socialists, anarchists, to moderates like centrists, and liberalist elements. The film was directed by Joris Ivens, written by John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway, narrated by Orson Welles and re-recorded by Hemingway (with Jean Renoir doing the narration in the French release), with music composed by Marc Blitzstein and arranged by Virgil Thomson.

-- The Spanish Earth, by Wikipedia

Rain, ...A Valparaiso, Misère au Borinage (Borinage),...Misère au Borinage (French, literally "Poverty in the Borinage"), also known as Borinage, was a 1934 Belgian documentary film directed by Henri Storck and Joris Ivens. Produced during the Great Depression, the film's theme was intensely socialist, covering the poor living conditions of the workers and coal miners of Belgium's industrialised Borinage region. It is considered a classic work of political cinema and has been described as "one of the most important references in the documentary genre".

Misère au Borinage was shot in black and white and is a silent film. Its intertitles are in French and Dutch languages. It opens with a title card, bearing the slogan: "Crisis in the Capitalist World. Factories are closed down, abandoned. Millions of proletarians are hungry!" and shows footage of the repression of a 1933 strike in Ambridge, Pennsylvania in the United States. The film then shifts to the Borinage, an industrial region in Belgium's Province of Hainaut, during and after the general strike of 1932. The majority of the film focuses on the plight of Borinage coal miners who have been evicted from their houses and made unemployed following their participation in the strike. It also shows the poor living conditions of the miners and their families. The film makes the argument that strike action could be justified by the poor conditions in which Belgian workers lived.

-- Misère au Borinage, by Wikipedia

17th Parallel: Vietnam in War,...17th Parallel: Vietnam in War is a 1968 French documentary film directed by Joris Ivens. The film sets out to show the effects of the American bombing campaign on the Vietnamese people, who were mainly peasant farmers.

In 1968, between South Vietnam under the control of the US Army and North Vietnam struggling for independence, a demilitarized zone was created around the 17th parallel. Joris Ivens and his wife, Marceline Loridan, went to this area around the village of Vinh Linh for two months to live among the peasants who had taken refuge in cellars in an attempt to survive the incessant bombing of the American artillery.

-- 17th Parallel: Vietnam in War, by Wikipedia

The Seine Meets Paris, Far from Vietnam,...In seven different segments, Godard, Klein, Lelouch, Marker, Resnais and Varda show their sympathy and support for the North Vietnamese army during the Vietnam war.

-- Far from Vietnam, by imdb

Pour le Mistral and How Yukong Moved the Mountains.How Yukong Moved the Mountains is a series of 12 documentary films about China directed by Joris Ivens. This film, whose title references the old Chinese story of an old man who moved the mountains (Yugong Yishan), deals with the last days of the Cultural Revolution.

-- How Yukong Moved the Mountains, by Wikipedia

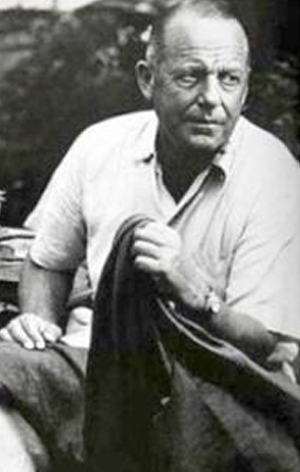

Born Georg Henri Anton Ivens into a wealthy family, Ivens went to work in one of his father's photo supply shops and from there developed an interest in film. Under the direction of his father, he completed his first film at 13; in college he studied economics with the goal of continuing his father's business, but an interest in class issues distracted him from that path. He met photographer Germaine Krull in Berlin in 1923, and entered into a marriage of convenience with her between 1927 and 1943...

In 1929, Ivens went to the Soviet Union and was invited to direct a film on a topic of his own choosing which was the new industrial city of Magnitogorsk. Before commencing work, he returned to the Netherlands to make Industrial Symphony for Philips Electric which is considered to be a film of great technical beauty. He returned to the Soviet Union to make the film about Magnitogorsk, Song of Heroes in 1931 with music composed by Hanns Eisler. This was the first film on which Ivens and Eisler worked together. It was a propaganda film about this new industrial city where masses of forced laborers and communist youth worked for Stalin's Five Year Plan. With Henri Storck, Ivens made Misère au Borinage (Borinage, 1933), a documentary on life in a coal mining region. In 1943, he also directed two Allied propaganda films for the National Film Board of Canada, including Action Stations, about the Royal Canadian Navy's escorting of convoys in the Battle of the Atlantic.The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the Naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade of Germany, announced the day after the declaration of war, and Germany's subsequent counter-blockade. The campaign peaked from mid-1940 through to the end of 1943.

The Battle of the Atlantic pitted U-boats and other warships of the German Kriegsmarine (Navy) and aircraft of the Luftwaffe (Air Force) against the Royal Navy, Royal Canadian Navy, United States Navy, and Allied merchant shipping. Convoys, coming mainly from North America and predominantly going to the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, were protected for the most part by the British and Canadian navies and air forces. These forces were aided by ships and aircraft of the United States beginning September 13, 1941. The Germans were joined by submarines of the Italian Regia Marina (Royal Navy) after Germany's Axis ally Italy entered the war on June 10, 1940....

It involved thousands of ships in more than 100 convoy battles and perhaps 1,000 single-ship encounters, in a theatre covering millions of square miles of ocean. The situation changed constantly, with one side or the other gaining advantage, as participating countries surrendered, joined and even changed sides in the war, and as new weapons, tactics, counter-measures and equipment were developed by both sides. The Allies gradually gained the upper hand, overcoming German surface-raiders by the end of 1942 and defeating the U-boats by mid-1943, though losses due to U-boats continued until the war's end. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill later wrote "The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril. I was even more anxious about this battle than I had been about the glorious air fight called the 'Battle of Britain'."

-- Battle of the Atlantic, by Wikipedia

From 1936 to 1945, Ivens was based in the United States. For Pare Lorentz's U.S. Film Service, in the year 1940, he made a documentary film on rural electrification called Power and the Land. It focused on a family, the Parkinsons, who ran a business providing milk for their community. The film showed the problem in the lack of electricity and the way the problem was fixed.Pare Lorentz (December 11, 1905 – March 4, 1992) was an American filmmaker known for his film work about the New Deal...

As the most influential documentary filmmaker of the Great Depression, Lorentz was the leading American advocate for government-sponsored documentary films. His service as a filmmaker for the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II was formidable, including technical films, documentation of bombing raids, and synthesizing raw footage of Nazi atrocities for an educational film on the Nuremberg Trials. Nonetheless, Lorentz perennially will be known best as "FDR′s filmmaker."...

Roosevelt was impressed ... and in 1936, as president of the United States, invited Lorentz to make a government-sponsored film about the Oklahoma Dust Bowl.

Despite not having any film credits, Lorentz was appointed to the Resettlement Administration as a film consultant. He was given US$6,000 to make a film, which became The Plow That Broke the Plains, a film that showed the natural and man–made devastation caused by the Dust Bowl. Though the tight budget and his inexperience occasionally showed through in the film, Lorentz's script, combined with Thomas Hardie Chalmers′s narration and Virgil Thomson′s score, made the 30-minute movie powerful and moving. The film, which had its first public showing on May 10, 1936 at Washington, D.C′s Mayflower Hotel, had a preview screening in March at the White House. Roosevelt was impressed and, after his re-election in 1936, gave Lorentz the opportunity to make a film about one of the president's favorite subjects: conservation. Lorentz made The River, a film celebrating the exploits of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The TVA mitigated flooding but, more importantly to Lorentz and to Roosevelt, it put a stop to the prodigious pillaging of the forests by providing cheap, readily available hydro–electric power to a wide area. This film won the Best Documentary at the Venice International Film Festival. The text of The River appeared in book form, and was nominated for the Pulitzer Prize in poetry the same year. It generally is considered his most masterful work...

Lorentz served in the U.S. Army Air Corps, more specifically the Air Transport Command (ATC), accompanied by Floyd Crosby, who became an outstanding cinematographer during World War II. He was promoted to the rank of colonel. While serving, he made 275 pilot navigational films and minor documentaries for the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) and the U.S. Information Agency (USIA), and filmed over 2,500 hours of bombing raids. (Note: Lorentz's name is not associated with any OWI or USIA films; his son Pare Lorentz, Jr., may have worked on a USIA film though most of his work was for USAID.) In 1946, Lorentz made a federally funded movie about the Nuremberg trials, intended to help educate the German people as to what had happened during the war. In the process of compiling material, Lorentz reviewed over 1 million hours of footage about the Nazis and their atrocities. Nuremberg, the film that resulted, played to "capacity audiences" in Germany for two years. However, it was not released in the United States until 1979. This film was produced for the Civil Affairs Division of the Government of Military Occupation (OMGUS). Lorentz's role and contributions to this production are not entirely clear because he prematurely resigned and the Hollywood director Budd Schulberg is given credit for completing it.

-- Pare Lorentz, by Wikipedia

In 1938 he traveled to China. The 400 Million (1939) depicted the history of modern China and the Chinese resistance during the Second Sino-Japanese War, including dramatic shots of the Battle of Taierzhuang. Robert Capa did camerawork, Sidney Lumet worked on the film as a reader, Hanns Eisler wrote the musical score, and Fredric March provided the narration. It, too, had been financed by the same people as those of Spanish Earth. Its chief fundraiser was Luise Rainer, recipient of the best actress Oscar two years in a row; and the entire group called themselves this time, History Today, Inc . The Guomindang government censored the film, fearing that it would give too much credit to left-wing forces. Ivens was also suspected of being a friend of Mao Zedong and especially Zhou Enlai.

In early 1943, Frank Capra hired Ivens to supervise the production of Know Your Enemy: Japan for his U.S. War Department film series Why We Fight. The film's commentary was written largely by Carl Foreman. Capra fired Ivens from the project because he felt that his approach was too sympathetic toward the Japanese. The film's release was held up because there were concerns that Emperor Hirohito was being depicted as a war criminal, and there was a policy shift to portray the Emperor more favorably after the war as a means of maintaining order in post-war Japan.

With the emerging "Red Scare" of the late 1940s, Ivens was forced to leave the country in the early months of the Truman administration. Ivens' leftist politics also put the kibosh on his first feature film project which was to have starred Greta Garbo. In fact, Walter Wanger, the film's producer, was adamant about "running [Ivens] out of town."

In 1946, commissioned to make a Dutch film about Indonesian 'independence', Ivens resigned in protest over what he considered ongoing imperialism; the Dutch were in his view resisting decolonization. Instead, Ivens filmed Indonesia Calling in secret, for which he received funding from the International Workers Order.Indonesia Calling is a 1946 Australian short documentary film directed by Joris Ivens and produced by the then Waterside Workers' Federation. The film gives a glimpse of immediate post-World War II Sydney as trade union seamen and waterside workers refuse to service Dutch ships (known as the "Black Armada") containing arms and ammunition destined for Indonesia to suppress the country's independence movement.

-- Indonesia Calling, by Wikipedia

For around a decade Ivens lived in Eastern Europe, working for several studios there. His position concerning Indonesia and his taking sides for the Eastern Bloc in the Cold War annoyed the Dutch government. Over a period of many years, he was obliged to renew his passport every three or four months....

From 1965 to 1970 he filmed two propaganda films about North Vietnam during the war: he made 17e parallèle: La guerre du peuple (17th Parallel: Vietnam in War) and he participated in the collective work Loin du Vietnam (Far from Vietnam). He was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize for the year 1967.

From 1971 to 1977, he shot How Yukong Moved the Mountains, a 763-minute propaganda documentary about the Cultural Revolution in China. He was given unprecedented access because of his pro-communist views and his old personal friendships with Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong.

-- Joris Ivens, by Wikipedia

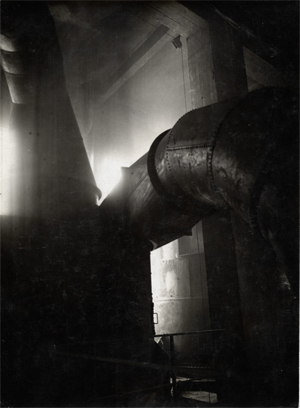

In Paris between 1926 and 1928, Krull became friends with Sonia Delaunay, Robert Delaunay, Eli Lotar, André Malraux, Colette, Jean Cocteau, André Gide and others; her commercial work consisted of fashion photography, nudes, and portraits.[1]:83–89 During this period she published the portfolio Métal (1928) which concerned "the essentially masculine subject of the industrial landscape."[5] Krull shot the portfolio's 64 black-and-white photographs in Paris, Marseille, and Holland during approximately the same period as Ivens was creating his film De Brug ("The Bridge") in Rotterdam, and the two artists may have influenced each other.[1]:70–77 The portfolio's subjects range from bridges, buildings (e.g., the Eiffel Tower), and ships to bicycle wheels; it can be read as either a celebration of machines or a criticism of them.[1]:77–82 Many of the photographs were taken from dramatic angles, and overall the work has been compared to that of László Moholy-Nagy and Alexander Rodchenko.[6] In 1999–2004 the portfolio was selected as one of the most important photobooks in history.[8][9][10][11]

By 1928 Krull was considered one of the best photographers in Paris, along with André Kertész and Man Ray.[1]:90 Between 1928 and 1933, her photographic work consisted primarily of photojournalism, such as her photographs for Vu, a French magazine.;[1]:97–112[5] also in the early 1930s,she also made a pioneering study of employment black spots in Britain for Weekly Illustrated (most of her ground-breaking reportage work from this period remains immured in press archives and she has never received the credit which is her due for this work).[12] Her book Études de Nu ("Studies of Nudes") published in 1930 is still well-known today.[5][10] Between 1930 and 1935 she contributed photographs for a number of travel and detective fiction books.[1]:113–125

In 1935–1940, Krull lived in Monte Carlo where she had a photographic studio.[13] Among her subjects during this period were buildings (such as casinos and palaces), automobiles, celebrities, and common people.[13] She may have been a member of the Black Star photojournalism agency which had been founded in 1935, but "no trace of her work appears in the press with that label."[1]:127

Black Star, also known as Black Star Publishing Company, was started by refugees from Germany who had established photographic agencies there in the 1930s. Today it is a New York City-based photographic agency with offices in London and in White Plains, New York. It is known for photojournalism, corporate assignment photography and stock photography services worldwide. It is noted for its contribution to the history of photojournalism in the United States. It was the first privately owned picture agency in the United States, and introduced numerous new techniques in photography and illustrated journalism. The agency was closely identified with Henry Luce's magazines Life and Time.

Black Star was formed in December 1935. The three founders were Kurt Safranski, Ernest Mayer and Kurt Kornfeld. In 1964, the company was sold to Howard Chapnick. The three founders; Safranski, Mayer and Kornfeld were German Jews who fled Berlin during the Nazi regime. They brought with them a wealth of knowledge and some new ideas for the American press.

Safranski was a graphic designer and editor for the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (BIZ), which was part of the Ullstein publishing house. During the early 1930s, Ullstein Verlag was Germany's largest publisher of books, newspapers and magazines. BIZ's circulation was over one million. While an editor at BIZ, Safranski was using two or more photos placed together to create a story which surpassed the need for text. Not only was this visually appealing, but it attracted more readers as well.

This drew the attention of the top American mass media publishers. William Randolph Hearst, a powerful media mogul of the day, was intrigued by the European advances in photography and printing. Hearst invited Safranski over to the United States to produce a dummy magazine using photos to tell the stories. Hearst liked the proposed idea but initially didn't move forward on it. Mayer then brought to idea to the experimental editorial department of Henry Luce, the largest publisher of the day, with periodicals such as Time and Fortune. Luce collaborated with Black Star to produce a new weekly magazine called Life. Life would use artistic photos in a new format. These pictures would be large and take up the majority of the page. They could capture not only a moment in time, but an emotion and story that would be paramount to the text. Prior to this, photojournalism in the U.S. was relegated to regional newspapers where text was more important than photos. Photos would sometimes be staged or posed or re-created to help a news article. But this all changed with the advent of the 35mm camera. The Leica, which was developed in Germany in 1925, was a small and easier to use camera. Advances in half-tone printing made using photographs in periodicals easier. Safranski and Mayer were already familiar with photographers who used this new technology to capture more candid moments.

Mayer owned the publishing company and photo agency, Mauritius, in Berlin. Forced by the Nazis to sell his business, he brought negatives, and connections to European photographers with him to the United States. The contacts included the notable photographers Dr. Paul Wolff and Fritz Goro. These contacts with European-based photographers, and the photographic negatives he brought with him, became the foundation for the new business.

Kornfeld was a literary agent back in his native Germany where he had a talent for bringing together authors and editors. Originally the idea for the company was to be a publishing house and a photo agency just like Mayer's Mauritius. However, the publishing business never took off and more profit was to be found in selling photos. Even though he had no experience with photography, Kornfeld became Black Star's best picture agent. He had a talent for creating rapport between client and artist. Therefore, Kornfeld handled their most important client, Life magazine, providing up to 200 photos a week.

Although Life was the agency's most high-profile client, Black Star also served other periodicals, newspapers, advertisers and publishers. Its stock of iconic photography represents a pictorial history of the 20th century beginning in the 1930s. This archive was anonymously donated to Ryerson University in 2005.

Noted Black Star photographers include Robert Capa, Andreas Feininger, Germaine Krull, Philippe Halsman, Martin Munkácsi, Kurt Severin, W. Eugene Smith, Marion Post-Wolcott, Bill Brandt, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Charles Moore, James Nachtwey, Lee Lockwood, Mario Giacomelli and Spider Martin.

-- Black Star (photo agency), by Wikipedia

In World War II, she became disenchanted with the Vichy France government, and sought to join the Free French Forces in Africa.[6] Due to her Dutch passport and her need to obtain proper visas, her journey to Africa included over a year (1941–1942) in Brazil where she photographed the city of Ouro Preto.[1]:227–231 Between 1942 and 1944 she was in Brazzaville in French Equatorial Africa, after which she spent several months in Algiers and then returned to France.[1]:231–243

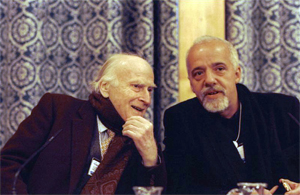

After World War II, she traveled to Southeast Asia as a war correspondent, but by 1946 had become a co-owner of the Oriental Hotel in Bangkok, Thailand, a role that she undertook until 1966.[1]:245–252[6] She published three books with photographs during this period, and also collaborated with Malraux on a project concerning the sculpture and architecture of Southeast Asia.[1]:252–255

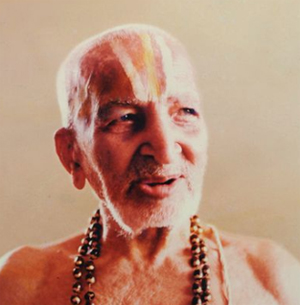

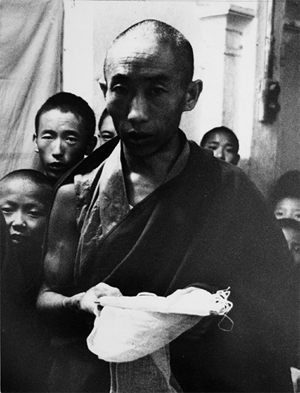

After retiring from the hotel business in 1966, she briefly lived near Paris, then moved to Northern India and converted to the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism.[1]:257–260 Her final major photographic project was the publication of a 1968 book Tibetans in India that included a portrait of the Dalai Lama.[1]:257–263 After a stroke, she moved to a nursing home in Wetzlar, Germany, where she died in 1985.[1]:265

Selected works

• Krull's archives are kept at the Museum Folkwang in Essen, Germany.

• Detroit Public Library Digital Collection houses a portrait of singer Adelaide Hall by Germaine Krull dated 1929, photographed during Blackbirds residency at the Moulin Rouge, Paris.[14]

Books

• Krull, Germaine. Métal. Paris: Librairie des arts décoratifs, 1928. (New facsimile edition published in 2003 by Ann and Jürgen Wilde, Köln.)

• Krull, Germaine. 100 x Paris. Berlin-Westend: Verlag der Reihe, 1929.

• Bucovich, Mario von. Paris. New York: Random House, 1930. (With photographs by Krull.)

• Colette. La Chatte. Paris: B. Grasset, 1930. (With photographs by Krull.)

• Krull, Germaine. Études de Nu. Paris: Librairie des Arts Décoratifs, 1930.

• Nerval, Gérard de, and Germaine Krull. Le Valois. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1930.

• Warnod, André. Visages de Paris. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1930. (With photographs by Krull.)

• Krull, Germaine, and Claude Farrère. La Route Paris-Biarritz. Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1931.

• Morand, Paul, and Germaine Krull. Route de Paris à la Méditerranée. Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1931.

• Simenon, Georges, and Germaine Krull. La Folle d'Itteville. Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1931.

• Krull, Germaine, and André Suarès. Marseille. Paris: Librairie Plon, 1935.

• Krull, Germaine, Raúl Lino, and Ruy Ribeiro Couto. Uma Cidade Antiga do Brasil, Ouro Preto. Lisboa: Edições Atlântico, 1943.

• Vailland, Roger. La Bataille d'Alsace (Novembre-Décembre 1944). Paris: Jacques Haumont, 1945. (With photographs by Krull.)

• Krull, Germaine. Chiengmai. Bangkok: Assumption Printing Press, 1950–1959?

• Krull, Germaine, and Dorothea Melchers. Bangkok: Siam's City of Angels. London: R. Hale, 1964.

• Krull, Germaine, and Dorothea Melchers. Tales from Siam. London: R. Hale, 1966.

• Krull, Germaine. Tibetans in India. Bombay: Allied Publishers, 1968.

• Krull, Germaine. La Vita Conduce la Danza. Firenze: Filippo Giunti, 1992. ISBN 88-09-20219-8. (Unpublished autobiography of Krull in French, La Vie Mène la Danse or "Life Leads the Dance", translated into Italian by Giovanna Chiti.)

Films

• Six pour Dix Francs (France, 1930)

• Il Partit pour un Long Voyage (France, 1932)

Further reading

• MacOrlan, Pierre. Germaine Krull: Photographes Nouveaux. Paris: Gallimard, 1931.

• Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn. Germaine Krull: Fotografien 1922–1966. Köln: Rheinland-Verlag, 1977. ISBN 3-7927-0364-5.

• Bouqueret, Christian, and Michèle Moutashar. Germaine Krull: Photographie 1924–1936. Arles: Musée Réattu, 1988.

• Sichel, Kim. From Icon to Irony: German and American Industrial Photography. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1995. ISBN 1-881450-06-6.

• Kosta, Barbara. "She was a Camera." Women's Review of Books, volume 17, issue 7, pages 9–10, April 2000.

• Sichel, Kim. "Germaine Krull and L'Amitié Noire: World War II and French Colonialist Film." In Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place, edited by Eleanor M. Hight and Gary D. Sampson. London: Routledge, 2002. ISBN 0-415-27495-8.

• Sichel, Kim. Germaine Krull: Photographer of Modernity, The MIT Press, 1999; ISBN 0262194015; ISBN 978-0262194013

• Specker, Heidi. Bangkok - Heidi Specker Germaine Krull im Sprengel-Museum Hannover, 9. Oktober 2005 bis 25. Juni 2006. Zülpich: Albert-Renger-Patzsch-Archiv, 2005. ISBN 3-00-017658-6.

• Sichel, Kim. Germaine Krull à Monte-Carlo = Germaine Krull: the Monte Carlo Years. Montréal: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal, 2006. ISBN 2-89192-306-5.

• Bertolotti, Alessandro. Books of Nudes. New York: Abrams, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8109-9444-7.

• Dumas, Marie Hélène. "Lumières d'Exil". Paris: Gallimard and Éditions Joëlle Losfeld, 2009. ISBN 978-2-07-078770-8. (A novel in French about Krull's life.)

References

1. Sichel, Kim. Germaine Krull: Photographer of Modernity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1999. ISBN 0-262-19401-5.

2. "New National Museum of Monaco Exhibition: Three Questions to Jean-Michel Bouhours, Chief Curator". Government of Monaco. 3 August 2007. Archived from the original on February 24, 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

3. Union List of Artist Names. "Krull, Germaine (French Photographer, 1897–1985)". J. Paul Getty Trust. Retrieved 16 April2010.

4. "Maker List" (PDF). J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs. December 2006. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

5. Rosenblum, Naomi. A History of Women Photographers, 2nd edition. New York: Abbeville Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7892-0658-7.

6. Baker, Kenneth. "Germaine Krull's Radical Vision / Photographer's Work Featured at SFMOMA." San Francisco Chronicle, 15 April 2000. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

7. Schoots, Hans. Living Dangerously: a Biography of Joris Ivens. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2000. ISBN 90-5356-433-0.

8. Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print 1919–1939. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 1999. ISBN 84-8026-125-0.

9. Roth, Andrew, editor. The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the 20th Century. New York: PPP Editions in association with Roth Horowitz LLC, 2001. ISBN 0-9670774-4-3.

10. Parr, Martin, and Gerry Badger. The Photobook: a History. Volume I. London & New York: Phaidon, 2004. ISBN 0-7148-4285-0.

11. Roth, Andrew, editor. The Open Book: a History of the Photographic Book from 1878 to the Present. Göteborg, Sweden: Hasselblad Center, 2004.

12. Ian Jeffrey,text written by.The Photo Book. London: Phaidon, 2000. p.255.

13. "Portrait of Hedonism with Glasses Half Empty." The Gazette (Montreal), 30 December 2006.

14. Portrait of singer Adelaide Hall by Germaine Krull, Paris, 1929":https://digitalcollections.detroitpubliclibrary.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A198931

External links

• Germaine Krull: Jeu de Paume exhibition, 2015

• O'Hagan, Sean Germaine Krull: the woman Man Ray named his equal

• "Germaine Krull, German Photographer" (slide show with 42 images).

• "In plain sight: Germaine Krull in Paris, The work of the maverick photographer gains new exposure in an exhibition in the French capital," by Claire Holland, The Financial Times, June 13-14, 2015

• "Contortions of Technique: Germaine Krull’s Experimental Photography," by Kim Sichel. In Mitra Abbaspour, Lee Ann Daffner, and Maria Morris Hambourg, eds. Object:Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909–1949. An Online Project of The Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2014.

********************************

Germaine Krull: 1897 — POZNAŃ, POLAND | 1985 — WETZLAR, GERMANY

German naturalised French photographer

by AwareWomenArtists.com

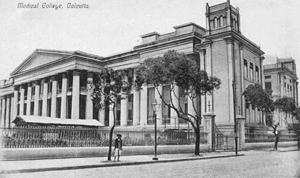

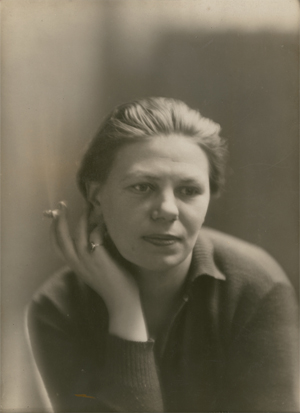

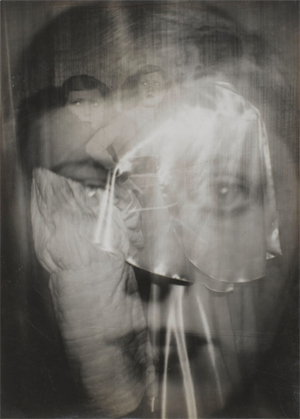

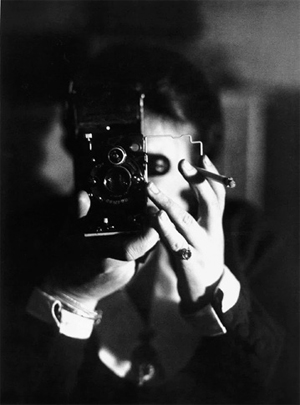

Germaine Krull, Autoportrait, Paris, 1927, gelatin silver print, 23.9 x 17.9 cm, Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

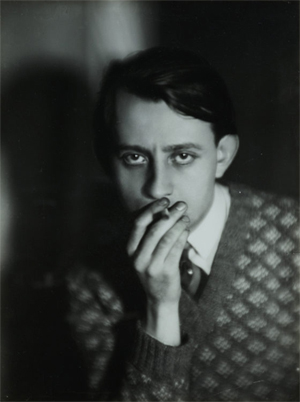

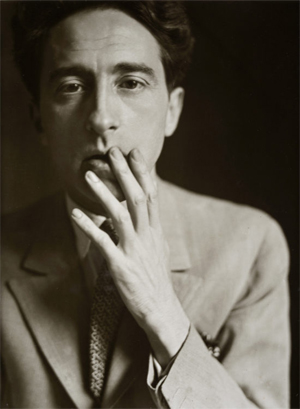

Germaine Krull, André Malraux, 1930, gelatin silver print, 23 x 17.3 cm, Museum Folkwang, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang, Essen

Germaine Krull, Assia, de profil, ca. 1930, gelatin silver print, 22.2 x 15.8 cm, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

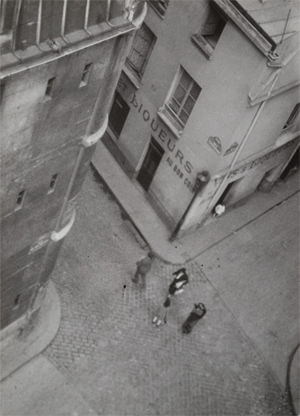

Germaine Krull, Au bon coin, Paris, 1929, gelatin silver print, 14.2 x 10.5 cm, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

Germaine Krull, Étude publicitaire pour Paul Poiret, 1926, Centre Pompidou, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

Germaine Krull, Jean Cocteau, 1929, gelatin silver print, 23.7 x 17,2 cm, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

Germaine Krull, Nu féminin, 1928, gelatin silver print, 21.6 x 14.4 cm, Centre Pompidou, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

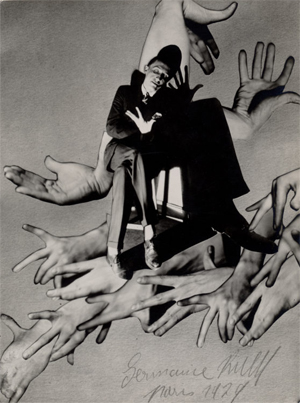

Germaine Krull, Pol Rab (illustrateur), 1930, photomontage, gelatin silver print, 19.5 x 14.5 cm, Amsab-Institut d’Histoire Sociale, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

Germaine Krull, Pont roulant, Rotterdam, ca. 1928, gelatin silver print, 21.9 x 15.3 cm, Stiftung Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Pinakothek der Moderne, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

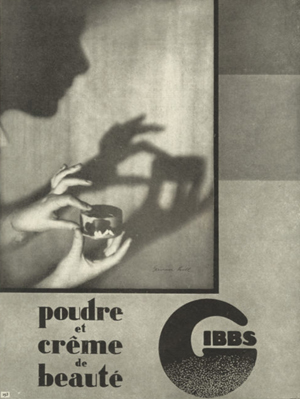

Germaine Krull, Publicité Gibbs L’Illustration, N 4533, 18 janvier 1930, 1930, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

Germaine Krull, Rue Auber à Paris, ca. 1928, gelatin silver print, MoMA, © Estate Germaine Krull, Museum Folkwang, Essen

Germaine Krull, Usine électrique Issy les Moulineaux, 1928, gelatin silver print, 22.6 x 16.6 cm, Amsab-Institut d’Histoire Sociale, © Estate Germaine Krull/ Museum Folkwang

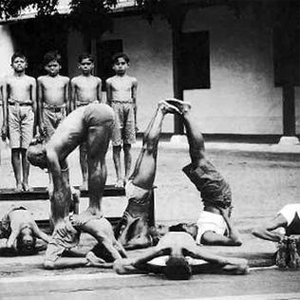

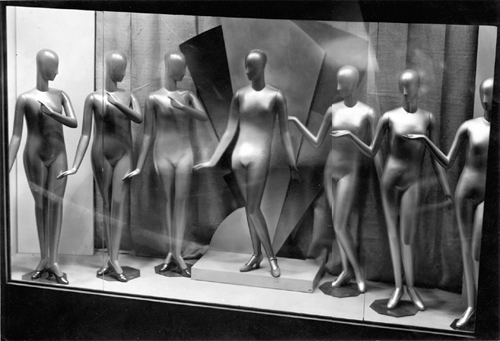

Considered in France as the representative of (New Objectivity), a German realist movement that introduced geometric motifs to photography, Germaine Krull remains known as the woman of Métal, named after one of her prestigious series. Born in Germany she had a hectic youth: expelled from Munich in 1918 thanks to her revolutionary activities, she moved to Berlin and began specialising in portraiture. Well integrated in the Berlin art scene, she published in literary magazines and photographed buildings and train tracks from new angles, focusing predominantly on the geometry of the city. From 1921 she lived in the Netherlands, where from 1924 to 1925 she and her future husband, filmmaker Joris Ivens, used industrial architecture as their main subject. She arrived in Paris in 1926, connecting with the Parisian artistic scene, working in fashion with Sonia Delaunay, and in commercial and industrial photography for Peugeot and Shell. With the help of Robert Delaunay she exhibited her series Métal – comprised of Dutch bridges, low-angle shots of the Eiffel Tower and images of automobiles – at the Salon d’automne. The 64 plates were published under the same name by the publisher Calavas in 1927. Despite the mediocre printing quality, Métal was a success and appeared to be the manifesto of a new vision. These reversed photographs reveal an interplay of volumes, abstract details and geometric motifs, and through their unusual cropping constitute a “manifesto of the modern perspective”, according to Christian Bouqueret, and symbolise the new aesthetic awareness of industrial beauty.

During the same period, her nude photographs of the young model Assia show fragments of the body that slip into abstraction (1930). At the end of the 1920s she had gained recognition and Walter Benjamin included her in A Short History of Photography (1931). She appeared thus as the leader of the Nouvelle Vision (New vision), a movement that considered photography, with its technical and artistic possibilities, as giving a new perspective of the world. Her portrait of filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein (1930) is emblematic of the style: tight framing, low-angle lighting and theatricality. In 1928 she exhibited at the first Salon des indépendants de la photographie, known as the Salon de l’escalier, in Paris, at Film und Foto in Stuttgart in 1929, and later in Munich and Brussels. She spent time with Berenice Abbott, André Kertész and Man Ray, and worked in close collaboration with Eli Lotar with whom she realised photomontages and exchanged negatives. During the same period, she worked for illustrated magazines (Vu, Voilà, Détective, Jazz) at the height of their golden years. She realised series on diverse subjects, such as the banks of the Seine, the Spanish Revolution and Javanese dancers. Her preference was for the Paris of Francis Carco and Pierre Mac Orlan – a marginal, working-class Paris. She photographed the zone and created a reportage on the homeless. She also participated in a series of books on the capital (Paris by Mario von Bucovich, 1928, 100 x Paris, 1929). In 1931 a monograph titled Germaine Krull was published in the collection “Photographes nouveaux” with texts by Pierre Mac Orlan was a “true consecration”, of her, as C. Bouqueret wrote. She then travelled throughout Europe and moved to the South of France where she conducted local reports. A discreet activist and friend of André Malraux, she emigrated to the United States in 1940, then to Brazil, and joining the Resistance. She directed the photographic service of Free France and photographed General De Gaulle in Algiers. After 1945 she become a war reporter in Germany, Italy and Indochina for various newspapers and illustrated magazines. She then left for Thailand and India, returning to Germany just before her death. Thanks to A. Malraux, a retrospective of her work was presented at the Cinémathèque Française in 1967, and some of her photographs were exhibited at Documenta 6 in Kassel in 1977. During her lifetime, she did not receive recognition as a photographer, probably because of the loss of her old negatives, recently found, and the dispersion of her production during the interwar years. However, internationally known for her engagement and personality, she has influenced entire generations of photographers.

Anne Reverseau

Translated from French by Katia Porro.

From the Dictionnaire universel des créatrices

© 2013 Des femmes – Antoinette Fouque

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

*********************************

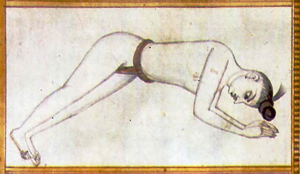

Artist: Germaine Krull (German, 1897–1985)Title: Two nude studies from der akt , ca. 1925Medium:

photogravures; size: 10.2 x 8.3 cm. (4 x 3.3 in.)

Nus, 1924, Collection Dietmar Siegert

Autoportrait à l’Icarette, vers 1925; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle; Achat grâce au mécénat de Yves Rocher, 2011. Ancienne collection Christian Bouqueret; Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI

Architecture ancienne : imprimerie de l’Horloge, 1928; Amsab-Institut d’Histoire Sociale, Gand

Étalage : les mannequins, 1928; Amsab-Institut d’Histoire Sociale, Gand

Marseille, juin 1930; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Thomas Walther Collection; Gift of Thomas Walther; Photo © 2015. Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence

Étude pour La Folle d’Itteville, 1931; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle; Achat grâce au mécénat de Yves Rocher, 2011 Ancienne collection Christian Bouqueret; Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, ;Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Guy Carrard

Cérémonie religieuse tibétaine, offrande; de l’écharpe blanche, vers 1960; Museum Folkwang, Essen