by T.W. Rhys Davids

Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

pp. 397-410

1901

-- The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1901

-- The Piprahwa Deceptions: Set-ups and Showdown, by T.A. Phelps

-- Lumbini On Trial: The Untold Story. Lumbini Is An Astonishing Fraud Begun in 1896, by T. A. Phelps

-- William Claxton Peppe: Persons of Indian Studies, by Prof. Dr. Klaus Karttunen

-- William Peppe, by The RAI Organization, UK

-- Piprahwa, by Wikipedia

Our oldest authority, the Maha-parinibbana suttanta, which can be dated approximately in the fifth century B.C., (1) [That is substantially, as to not only ideas, but words. There was dotting of i's and crossing of t's afterwards. It was naturally when they came to write these documents that the regulation of orthography [the conventional spelling system of a language] and dialect arose. At the time when the Suttanta was first put together out of older material, it was arranged for recitation, not for reading, and writing was used only for notes. See the Introduction to my "Dialogues of the Buddha," vol. i.] states that after the cremation of the Buddha's body at Kusinara, the fragments that remained were divided into eight portions.

-- Dialogues of the Buddha, In 3 vols. Bound in 2., Vol. 1, translated from the Pali of the Digha Nikaya by T.W. Rhys Davids

Dialogues of the Buddha

In 3 vols. Bound in 2. Vol. 1

translated from the Pali of the Digha Nikaya by T.W. Rhys Davids

1899

PREFACE.

NOTE ON THE PROBABLE AGE OF THE DIALOGUES.

The Dialogues of the Buddha, constituting, in the Pali text, the Digha and Magghima Nikayas, contain a full exposition of what the early Buddhists considered the teaching of the Buddha, to have been. Incidentally they contain a large number of references to the social, political, and religious condition of India at the time when they were put together. We do not know for certain what that time exactly was. But every day is adding to the number of facts on which an approximate estimate of the date may be based. And the ascertained facts are already sufficient to give us a fair working hypothesis.

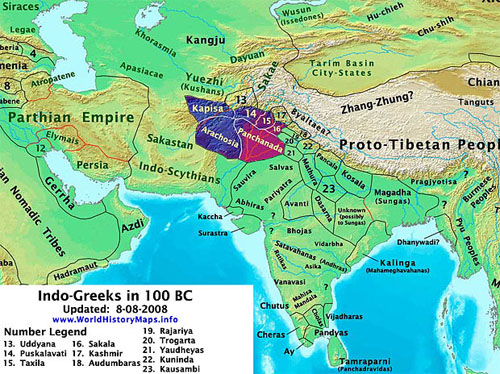

In the first place the numerous details and comparative tables given in the Introduction to my translation of the Milinda show without a doubt that practically the whole of the Pali Pitakas were known, and regarded as final authority, at the time and place when that work was composed. The geographical details given on pp. xliii, xliv tend to show that the work was composed in the extreme North-West of India. There are two Chinese works, translations of Indian books taken to China from the North of India, which contain, in different recensions, the introduction and the opening chapters of the Milinda1 [See the authors quoted in the Introduction to voi. ii of my translation. Professor Takakusu, in an article in the J.R.A.S. for 1896, has added important details.]. For the reasons adduced (loco citato) it is evident that the work must have been composed at or about the time of the Christian era. Whether (as M. Sylvain Levy thinks) it is an enlarged work built up on the foundation of the Indian original of the Chinese books; or whether (as I am inclined to think) that original is derived from our Milinda, there is still one conclusion that must be drawn — the Nikayas, nearly if not quite as we now have them in the Pali, were known at a very early date in the North of India.

Then again, the Katha Vatthu (according to the views prevalent, at the end of the fourth century A.D., at Kankipura in South India, and at Anuradhapura in Ceylon; and recorded, therefore, in their commentaries, by Dhammapala and Buddhaghosa) was composed, in the form in which we now have it, by Tissa, the son of Moggali, in the middle of the third century B.C., at the court of Asoka, at Pataliputta, the modern Patna, in the North of India.

It is a recognised rule of evidence in the courts of law that, if an entry be found in the books kept by a man in the ordinary course of his trade, which entry speaks against himself, then that entry is especially worthy of credence. Now at the time when they made this entry about Tissa’s authorship of the Katha Vatthu the commentators believed, and it was an accepted tenet of those among whom they mixed — just as it was, mutatis mutandis, among the theologians in Europe, at the corresponding date in the history of their faith — that the whole of the canon was the word of the Buddha. They also held that it had been actually recited, at the Council of Ragagaha, immediately after his decease. It is, I venture to submit, absolutely impossible, under these circumstances, that the commentators can have invented this information about Tissa and the Katha Vatthu. They found it in the records on which their works are based. They dared not alter it. The best they could do was to try to explain it away. And this they did by a story, evidently legendary, attributing the first scheming out of the book to the Buddha. But they felt compelled to hand on, as they found it, the record of Tissa's authorship. And this deserves, on the ground that it is evidence against themselves, to have great weight attached to it.

The text of the Katha Vatthu now lies before us in a scholarly edition, prepared for the Pali Text Society by Mr. Arnold C. Taylor. It purports to be a refutation by Tissa of 250 erroneous opinions held by Buddhists belonging to schools of thought different from his own. We have, from other sources, a considerable number of data as regards the different schools of thought among Buddhists — often erroneously called ‘the Eighteen Sects.'1 [They are not ‘sects' at all, in the modem European sense of the word. Some of the more important of these data are collected in two articles by the present writer in the ‘Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society' for 1891 and 1892.] We are beginning to know something about the historical development of Buddhism, and to be familiar with what sort of questions are likely to have arisen. We are beginning to know something of the growth of the language, of the different Pali styles. In all these respects the Katha Vatthu fits in with what we should expect as possible, and probable, in the time of Asoka, and in the North of India.

Now the discussions as carried on in the Katha Vatthu are for the most part, and on both sides, an appeal to authority. And to what authority? Without any exception as yet discovered, to the Pitakas, and as we now have them, in Pali. Thus on p. 339 the appeal is to the passage translated below, on p. 278, § 6; and it is quite evident that the quotation is from our Suttanta, and not from any other passage where the same words might occur, as the very name of the Suttanta, the Kevaddha (with a difference of reading found also in our MSS.), is given. The following are other instances of quotations: —Katha Vatthu / The Nikayas

p. 344 = A. II, 50.

345 = S. I, 33.

345 = A. II, 54.

347 = Kh. P.VII, 6, 7.

348 = A. III, 43.

351 = Kh. P. VIII, 9.

369 = M. I, 85, 92, &c,

404 = M. I, 4.

413 = S. IV, 362.

426 = D. I, 70.

440 = S. I, 33.

457 = D. (M. P. S. 23).

457 = A. II, 172.

459 = M. I, 94.

481 = D. I, 83, 84.

483 = D. I, 84.

484 = A. II, 126.

494 = S. I, 206 = J. IV, 496.

p. 505 = M. I, 490.

506 = M. I, 485 = S. IV, 393 (nearly).

513 = A. I, 197.

522 = M. I, 389.

525 = Dhp. 164.

528 = M. I, 447.

549 = S. N. 227 = Kh. P. VI, 6.

554 = S. I, 233.

554 = Vim. V. XXXIV, 25-27.

565 = D. I, 156.

588, 9= P. P. pp. 71, 72.

591 = M. I, 169.

597, 8 = A. I, 141, 2.

602 = Dh. C. P. Sutta, §§ 9-23.

There are many more quotations from the older Pitaka books in the Katha Vatthu, about three or four times as many as are contained in this list. But this is enough to show that, at the time when the Katha Vatthu was composed, all the Five Nikayas were extant; and were considered to be final authorities in any question that was being discussed. They must themselves, therefore, be considerably older.

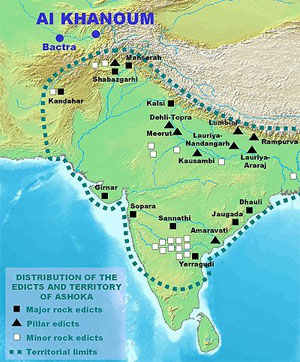

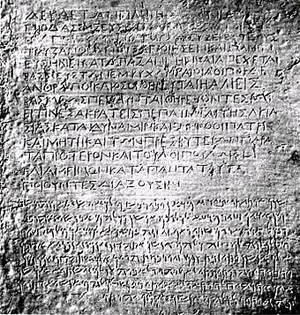

Thirdly, Hofrath Buhler and Dr. Hultsch have called attention1 ['Epigr. Ind.,' II, 93, and 'Z.D.M.G.,’ xl, p. 58.] to the fact that in inscriptions of the third century B.C. we find, as descriptions of donors to the dagabas,, the expressions dhammakathika, petaki, suttantika, suttantakini, and panka-neka-yika. The Dhamma, the Pitakas, the Suttantas, and the five Nikayas must have existed for some time before the brethren and sisters could be described as preachers of the Dhamma, as reciters of the Pitaka, and as guardians of the Suttantas or of the Nikayas (which were not yet written, and were only kept alive in the memory of living men and women).

Simple as they seem, the exact force of these technical designations is not, as yet, determined. Dr. K. Neumann thinks that Petaki does not mean ‘knowing the Pitakas,' but ‘knowing the Pitaka,’ that is, the Nikayas — a single Pitaka, in the sense of the Dhamma, having been known before the expression ‘the Pitakas’ came into use.1 ['Reden des Gotamo,' pp. x, xi.] As he points out, the title of the old work Petakopadesa, which is an exposition, not of the three Pitakas, but only of the Nikayas, supports his view. So again the Dialogues are the only parts or passages of the canonical books called, in our MSS., suttantas. Was then a suttantika one who knew precisely the Dialogues by heart? This was no doubt the earliest use of the term. But it should be recollected that the Katha Vatthu, of about the same date, uses the word suttanta also for passages from other parts of the scriptures.

However this may be, the terms are conclusive proof of the existence, some considerable time before the date of the inscriptions, of a Buddhist literature called either a Pitaka or the Pitakas, containing Suttantas, and divided into Five Nikayas.

Fourthly, on Asoka's Bhabra Edict he recommends to the communities of the brethren and sisters of the Order, and to the lay disciples of either sex, frequently to hear and to meditate upon seven selected passages. These are as follows: —1. Vinaya-samukkamsa.

2. Ariya-vasini from the Digha (Samgiti Suttanta).

3. Anagata-bhayani from the Anguttara III, 105-108.

4. Muni-gatha from the Sutta Nipata 206-220.

5. Moneyya Sutta from the Iti Vuttaka 67 = A. 1, 272.

6. Upatissa-pasina.

7. Rahulovada = Rahulovada Suttanta (M. I, 414-420).

Of these passages Nos. 1 and 6 have not yet been satisfactorily identified. The others may be regarded as certain, for the reasons I have set out elsewhere.1 [‘Journal of the Pali Text Society,' 1896; ‘Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society,’ 1898, p. 639. Compare ‘Milinda' (S.B.E., vol. xxxv), pp. xxxvii foll.]The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1898

11. Asoka's Bhadra Edict

by T.W. Rhys Davids

1898

p. 639

As the seven passages (pariyaya) mentioned by name on this Edict have now been (with various degrees of certainly) identified, it may be of use to record the result: —Asoka / Pali / Where Found

1. Vinaya-samukkamsa / (? Patimokkha) / J.R.A.S., 1876

2. Ariya-vasani / Ariya-vasa / Digha (Sangiti Sutta)

3. Anagata-bhayani / Anagata-bhayani / Anguttara, iii, 105-108

4. Muni-gatha / Muni-sutta / Sutta Nipata, 206-220

5. Moneyya-sutta / Moneyya-sutta / It., No. 67 = A., i, 272

6. Upatissa-pasina / (Upatissa-panho / Vin., i, 39-41)

7. Rahulovada / Rahulovada-sutta / Majjhima, i, 414-420

Nos. 1 and 6 are the most doubtful. The Patimokkha can scarcely be rightly called a dhamma-pariyaya, and it does not correspond to the meaning of the title used by Asoka. The noun samukkamsa has not been found in the Pitakas. The verb always means 'to exalt.' (S.N., 132 = 438; M., i, 498; Th., i, 632.) 'The Exaltation of Vinaya' or 'of the Vinaya ' is much more probably meant, as the title of some short sutta or passage in praise of Vinaya in one or other of its two senses, ethical or legal. And I quite agree, therefore, with M. Senart (p. 204) in regarding this identification as unsatisfactory.

As to No. 6, short edifying passages of the Vinaya are distinguished by titles. Vin., i, pp. 13, 14, §§ 38-47 (=S., iii, 66-68), is the Anatta-lakkhana-sutta; Vin., i, pp. 34, 35 ( = S., iv, 19, 20), is the Aditta-pariyaya, etc. And the passage identified with No. 6 might have been called Sariputta- or Upatissa-panho. But no mention of the title has yet been found in the Pitakas, and the identification, though otherwise suitable, is therefore at least uncertain.

No. 2 is no doubt the passage on the ten Ariya-vasa, not yet published, but contained in the Sangiti Sutta of the Digha. A similar passage may also be looked for in the Nipata of the Anguttara dealing with the Tens. The difference of gender is no objection. So pariyayani = pariyaya.

With regard to No. 7, it is not without reason that a special qualification is introduced in the Edict. There are so many 'Exhortations to Rahula' in the Pitakas that it was necessary to specify the one meant. The ones excluded, or some of them, will be found at S.N., 325-342 (dated in the 14th year after the Nirvana}; M.. i, 420 foll. (dated in the 12th year of the Nirvana); S., ii, 244 foll.; and S., iii, 135 and 136. All these are spoken by the Buddha. The expression in the Edict would seem also to imply that there is at least one other, not yet published, spoken by some one else.

No. 4, the Muni-gatha, called Muni Sutta in the Pali, is called Muni-gatha (exactly as in the Edict) in the Divyavadana. Other instances of such slight variations in titles are given in my article on this Edict in the Journal of the Pali Text Society, 1896.

Nos. 2 and 5 are, I believe, identified here for the first time.

T.W. Rhys Davids

No. 2 also occurs in the tenth book of the Anguttara. It is clear that in Asoka’s time there was acknowledged to be an authoritative literature, probably a collection of books, containing what was then believed to be the words of the Buddha: and that it comprised passages already known by the titles given in his Edict. Five out of the seven having been found in the published portions of what we now call the Pitakas, and in the portion of them called the Five Nikayas, raises the presumption that when the now unpublished portions are printed the other two will also, probably, be identified. We have no evidence that any other Buddhist literature was in existence at that date.

What is perhaps still more important is the point to which M. Senart2 ['Inscriptions de Piyadasi,' II, 314-322.] has called attention, and supported by numerous details: — the very clear analogy between the general tone and the principal points of the moral teaching, on the one hand of the Asoka edicts as a whole, and on the other of the Dhammapada, an anthology of edifying verses taken, in great part, from the Five Nikayas The particular verses selected by M. Senart, as being especially characteristic of Asoka’s ideas, include extracts from each of the Five.

Fifthly, the four great Nikayas contain a number of stock passages, which are constantly recurring, and in which some ethical state is set out or described. Many of these are also found in the prose passages of the various books collected together in the Fifth, the Khuddaka Nikaya. A number of them are found in each of the thirteen Suttantas translated in this volume. There is great probability that such passages already existed, as ethical sayings or teachings, not only before the Nikayas were put together, but even before the Suttantas were put together.

There are also entire episodes, containing not only ethical teaching, but names of persons and places and accounts of events, which are found, in identical terms, at two or more places. These should be distinguished from the last. But they are also probably older than our existing texts. Most of the parallel passages, found in both Pali and Sanskrit Buddhist texts, come under one or other of these two divisions.

Sixthly, the Samyutta Nikaya (III, 13) quotes one Suttanta in the Dialogues by name; and both the Samyutta and the Anguttara Nikayas quote, by name and chapter, certain poems now found only in a particular chapter of the Sutta Nipata. This Suttanta, and these poems, must therefore be older, and older in their present arrangement, than the final settlement of the text of these two Nikayas.

Seventhly, several of the Dialogues purport to relate conversations that took place between people, cotemporaries with the Buddha, but after the Buddha's death: One Sutta in the Anguttara is based on the death of the wife of Munda, king of Magadha, who began to reign about forty years after the death of the Buddha. There is no reason at all to suspect an interpolation. It follows that, not only the Sutta itself, but the date of the compilation of the Anguttara, must be subsequent to that event.

There is a story in Peta Vatthu IV, 3, 1 about a King Pingalaka. Dhammapala, in his commentary, informs us that this king, of whom nothing is otherwise known, lived two hundred years after the Buddha. It follows that this poem, and also the Peta Vatthu in which it is found, and also the Vimana Vatthu, with which the Peta Vatthu really forms one whole work, are later than the date of Pingalaka. And there is no reason to believe that the commentator’s date, although it is evidently only a round number, is very far wrong. These books are evidently, from their contents, the very latest compositions in all the Five Nikayas.

There is also included among the Thera Gatha, another book in the Fifth Nikaya, verses said, by Dhammapala the commentator,1 [Quoted by Prof. Oldenberg at p. 46 of his edition.] to have been composed by a thera of the time of King Bindusara, the father of Asoka, and to have been added to the collection at the time of Asoka's Council.

Eighthly, several Sanskrit Buddhist texts have now been made accessible to scholars. We know the real titles, given in the MSS. themselves, of nearly 200 more.2 [Miss C. Hughes is preparing a complete alphabetical list of all these works for the 'Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society,’ 1899.] And the catalogues in which the names occur give us a considerable amount of detailed information as to their contents. No one of them is a translation, or even a recension, of any one of the twenty-seven canonical books. They are independent works; and seem to bear to the canonical books a relation similar, in many respects, to that borne by the works of the Christian Fathers to the Bible. But though they do not reproduce any complete texts, they contain numerous verses, some whole poems, numerous sentences in prose, and some complete episodes, found in the Pali books. And about half a dozen instances have been already found in which such passages are stated, or inferred, to be from older texts, and are quoted as authorities. Most fortunately we may hope, owing to the enlightened liberality of the Academy of St. Petersburg, and the zeal and scholarship of Professor d’Oldenbourg and his co-workers, to have a considerable number of Buddhist Sanskrit Texts in the near future. And this is just what, in the present state of our knowledge of the history of Buddhist writings, is so great a desideratum.

It is possible to construct, in accordance with these facts, a working hypothesis as to the history of the literature. It is also possible to object that the evidence drawn from the Milinda may be disregarded on the ground that there is nothing to show that that work, excepting only the elaborate and stately introduction and a few of the opening chapters, is not an impudent forgery, and a late one, concocted by some Buddhist in Ceylon. So the evidence drawn from the Katha Vatthu may be disregarded on the ground that there is nothing to show that that work is not an impudent forgery, and a late one, concocted by some Buddhist in Ceylon. The evidence drawn from the inscriptions may be put aside on the ground that they do not explicitly state that the Suttantas and Nikayas to which they refer, and the passages they mention, are the same as those we now have. And the fact that the commentators point out, as peculiar, that certain passages are nearly as late, and one whole book quite as late, as Asoka, is no proof that the rest are older. It may even be maintained that the Pali Pitakas are not therefore Indian books at all: that they are all Ceylon forgeries, and should be rightly called ‘the Southern Recension’ or ‘the Simhalese Canon.'

Each of these propositions, taken by itself, has the appearance of careful scruple. And a healthy and reasonable scepticism is a valuable aid to historical criticism. But can that be said of a scepticism that involves belief in things far more incredible than those it rejects.? In one breath we are reminded of the scholastic dulness, the sectarian narrowness, the literary incapacity, even the senile imbecility of the Ceylon Buddhists. In the next we are asked to accept propositions implying that they were capable of forging extensive documents so well, with such historical accuracy, with so delicate a discrimination between ideas current among themselves and those held centuries before, with so great a literary skill in expressing the ancient views, that not only did they deceive their contemporaries and opponents, but European scholars have not been able to point out a single discrepancy in their work.1 [As is well known, the single instance of such a discrepancy, which Prof. Minayeff made so much of, is a mare's nest. The blunder is on the pert of the European professor, not of the Ceylon pandits. No critical scholar will accept the proposition that because the commentary on the Katha Vatthu mentions the Vetulyaka, therefore the Katha Vatthu itself must be later than the rise of that school.] It is not unreasonable to hesitate in adopting a scepticism which involves belief in so unique, and therefore so incredible, a performance.

The hesitation will seem the more reasonable if we consider that to accept this literature for what it purports to be — that is, as North Indian,2 [North Indian, that is, from the modern European point of view. In the books themselves the reference is to the Middle Country (Magghima Desa). To them the country to the south of the Vindhyas simply did not come into the calculation. How suggestive this is as to the real place of origin of these documents!] and for the most part pre-Asokan — not only involves no such absurdity, but is really just what one would a priori expect, just what the history of similar literatures elsewhere would lead one to suppose likely.

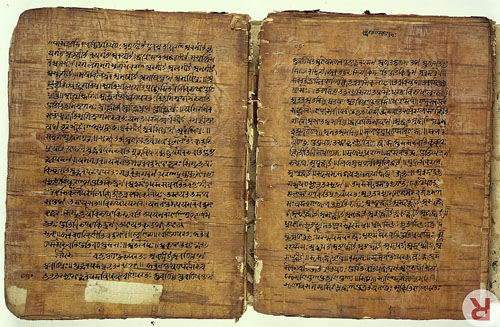

The Buddha, like other Indian teachers of his time, taught by conversation. A highly educated man (according to the education current at the time), speaking constantly to men of similar education, he followed the literary habit of his time by embodying his doctrines in set phrases, sutras, on which he enlarged on different occasions in different ways. In the absence of books — for though writing was widely known, the lack of writing materials made any lengthy written books impossible3 [Very probably memoranda were used. But the earliest records of any extent were the Asoka Edicts, and they had to be written on stone.] — such sutras were the recognised form of preserving and communicating opinion. These particular ones were not in Sanskrit, but in the ordinary conversational idiom of the day, that is to say, in a sort of Pali.

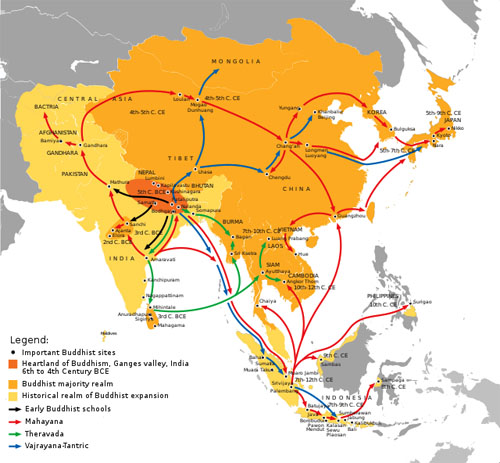

When the Buddha died these sayings were collected together by his disciples into the Four Great Nikayas. They cannot have reached their final form till about fifty years afterwards. Other sayings and verses, most of them ascribed not to the Buddha himself, but to the disciples, were put into a supplementary Nikaya. We know of slight additions made to this Nikaya as late as the time of Asoka. And the developed doctrine found in certain short books in it — notably in the Buddhavamsa and Kariya Pitaka, and in the Peta- and Vimana-Vatthus — show that these are later than the four old Nikayas.

For a generation or two the books as originally put together were handed down by memory. And they were doubtless accompanied from the first, as they were being taught, by a running commentary. About 100 years after the Buddha’s death there was a schism in the community. Each of the two schools kept an arrangement of the canon — still in Pali (or possibly some allied dialect). Sanskrit was not used for any Buddhist works till long afterwards, and never used at all, so far as we know, for the canonical books. Each of these two schools broke up, in the following centuries, into others; and several of them had their different arrangements of the canonical books, differing also no doubt in minor details. Even as late as the first century after the Christian Era, at the Council of Kanishka, these books, among many others then extant, remained the only authorities.1 [On the often repeated error that a Sanskrit canon was established at Kanishka’s Council, see my 'Milinda,' vol. ii, pp. xv, xvi.] But they all, except only our present Pali Nikayas, have been lost in India. Of the stock passages of ethical statement, and of early episodes, used in the composition of them, and of the Suttas now extant, numerous fragments have been preserved in the Hinayana Sanskrit texts. And some of the Suttas, and of the separate books, as used in other schools, are represented in Chinese translations of the fourth and fifth centuries A.D. A careful and detailed comparison of these remains with the Pali Nikayas, after the method adopted in Windisch’s 'Mara und Buddha,' cannot fail to throw much light on the history, and on the method of composition, of the canonical books, which in style and method, in language and contents and tone, bear all the marks of so considerable an antiquity.

Hofrath Dr. Buhler, in the last work he published, expressed the opinion that these books, as we have them in the Pali, are good evidence, certainly for the fifth, probably for the sixth, century B.C. Subject to what has been said above, that will probably become, more and more, the accepted opinion. And it is this which gives to all they tell us, either directly or by implication, of the social, political, and religious life of India, so great a value.1 [No reference has been made, in these slight and imperfect remarks, to the history of the Vinaya. There is nothing to add, on that point, to the able and lucid exposition of Prof. Oldenberg in the Introduction to his edition of the text.]

It is necessary, in spite of the limitations of our space, to add a few words on the method followed in this version. We talk of Pali books. They are not books in the modern sense. They are memorial sentences intended to be learnt by heart; and the whole style, and method of arrangement, is entirely subordinated to this primary necessity. The leading ideas in any one of our Suttantas, for instance, are expressed in short phrases not intended to convey to a European reader the argument underlying them. These are often repeated with slight variations. But neither the repetitions nor the variations — introduced, and necessarily introduced, as aids to memory — help the modern reader very much. That of course was not their object. For the object they were intended to serve they are singularly well chosen, and aptly introduced.

Other expedients were adopted with a similar aim. Ideas were formulated, not in logically co-ordinated sentences, but in numbered groups; and lists were drawn up such as those found in the tract called the Silas, and in the passage on the rejected forms of asceticism, both translated below. These groups and lists, again, must have been accompanied from the first by a running verbal commentary, given, in his own words, by the teacher to his pupils. Without such a comment they are often quite unintelligible, and always difficult.

The inclusion of such memoria technica [memory technique] makes the Four Nikayas strikingly different from modern treatises on ethics or psychology. As they stand they were never intended to be read. And a version in English, repeating all the repetitions, rendering each item in the lists and groups as they stand, by a single English word, without commentary, would quite fail to convey the meaning, often intrinsically interesting, always historically valuable, of these curious old documents.

It is no doubt partly the result of the burden of such memoria technica, but partly also owing to the methods of exposition then current in North India, that the leading theses of each Suttanta are not worked out in the way in which we should expect to find similar theses worked out now in Europe. A proposition or two or three, are put forward, re-stated with slight additions or variations, and placed as it were in contrast with the contrary proposition (often at first put forward by the interlocutor). There the matter is usually left. There is no elaborate logical argument. The choice is offered to the hearer; and, of course, he usually accepts the proposition as maintained by the Buddha. The statement of this is often so curt, enigmatic, and even —owing not seldom simply to our ignorance, as yet, of the exact force of the technical terms used — so ambiguous, that a knowledge of the state of opinion on the particular point, in North India, at the time, or a comparison of other Nikaya passages on the subject, is necessary to remove the uncertainty.

It would seem therefore most desirable that a scholar attempting to render these Suttantas into a European language — evolved in the process of expressing a very different, and often contradictory, set of conceptions — should give the reasons of the faith that is in him. He should state why he holds such and such an expression to be the least inappropriate rendering: and quote parallel passages from other Nikaya texts in support of his reasons. He should explain the real significance of the thesis put forward by a statement of what, in his opinion, was the point of view from which it was put forward, the stage of opinion into which it fits, the current views it supports or controverts. In regard to technical terms, for which there can be no exact equivalent, he should give the Pali. And in regard to the mnemonic lists and groups, each word in which is usually a crux, he should give cross-references, and wherever he ventures to differ from the Buddhist explanations, as handed down in the schools, should state the fact, and give his reasons. It is only by such discussions that we can hope to make progress in the interpretation of the history of Buddhist and Indian thought. Bare versions are of no use to scholars, and even to the general reader they can only convey loose, inadequate, and inaccurate ideas.

These considerations will, I trust, meet with the approval of my fellow workers. Each scholar would of course, in considering the limitations of his space, make a different choice as to the points he regarded most pressing to dwell upon in his commentary, as to the points he would leave to explain themselves. It may, I am afraid, be considered that my choice in these respects has not been happy, and especially that too many words or phrases have been left without comment, where reasons were necessary. But I have endeavoured, in the notes and introductions, to emphasise those points on which further elucidation is desirable; and to raise some of the most important of those historical questions which will have to be settled before these Suttantas can finally be considered as having been rightly understood.

T.W. Rhys Davids

'Nalanda,' April, 1899.

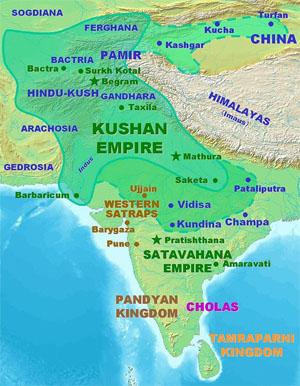

These eight portions were allotted as follows:--

1. To Ajatasattu, king of Magadha.

2. To the Licchavis of Vesali.

3. To the Sakyas of Kapilavastu.

4. To the Bulis of Allakappa.

5. To the Koliyas of Ramagama.

6. To the brahmin of Vethadipa.

7. To the Mallas of Pava.

8. To the Mallas of Kusinara.

Drona, the brahmin who made the division, received the vessel in which the body had been cremated. And the Moriyas of Pipphalivana, whose embassy claiming a share of the relics only arrived after the division had been made, received the ashes of the funeral pyre.

Of the above, all except the Sakyas and the two brahmins based their claim to a share on the fact that they also, like the deceased teacher, were Kshatriyas. The brahmin of Vethadipa claimed his because he was a brahmin; and the Sakyas claimed theirs on the ground of their relationship. All ten promised to put up a cairn over their portion, and to establish a festival in its honour.

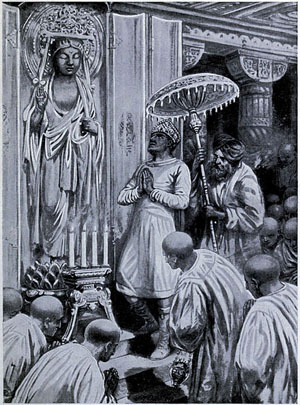

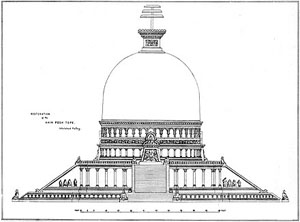

Of these ten cairns, or stupas, only one has been discovered -- that of the Sakyas. The careful excavation of Mr. Peppe makes it certain that this stupa had never been opened until he opened it. The inscription on the casket states that "This deposit of the remains of the Exalted One is that of the Sakyas, the brethren of the Illustrious One." It behoves those who would maintain that it is not, to advance some explanation of the facts showing how they are consistent with any other theory. We are bound in these matters to accept, as a working hypothesis, the most reasonable of various possibilities. The hypothesis of forgery is in this case simply unthinkable. And we are fairly entitled to ask: "If this stupa and these remains are not what they purport to be, then what are they?" As it stands the inscription, short as it is, is worded in just the manner most consistent with the details given in the Suttanta. And it advances the very same claim (to relationship) which the Sakyas alone are stated in the Suttanta to have advanced. It does not throw much light on the question to attribute these coincidences to mere chance, and so far no one has ventured to put forward any explanation except the simple one that the stupa is the Sakya tope.

Though the sceptics -- only sceptics, no doubt, because they think it is too good to be true -- have not been able to advance any other explanation, they might have brought forward an objection which has so far escaped notice. It is alleged, namely, in quite a number of Indian books, that Asoka broke open all the eight stupas except one, and took the relics away. This is a remarkable statement. That the great Buddhist emperor should have done this is just as unlikely as that his counterpart, Constantine the Great, should have rifled, even with the best intentions, the tombs most sacred in the eyes of Christians. The legend deserves, therefore, investigation, quite apart from its reference to the Sakya tope. And in looking further into the matter I have come across some curious points which will probably be interesting to the readers of this Journal.

The legend might be given in my own words, filling out the older versions of it by details drawn from the later ones. We might thus obtain an easy narrative, with literary unity and logical sequence. But we should at the same time lose all historical accuracy. We should only have a new version -- one that had not been current anywhere, at any time, among Buddhists in India. The only right method is to adhere strictly to the historical sequence, taking each account in order of time, and letting it speak for itself.

Now it is curious that there is no mention of the breaking open of stupas in any one of the twenty-nine canonical Buddhist writings, though they include documents of all ages from the time of the Buddha down to the time of Asoka. Nor, with one doubtful exception, is such an act referred to in any book which is good evidence for the time before Asoka. But in the canonical books there is frequent reference to the man who breaks up the Order, the schismatic, the sangha-bhedako. And in the passages in later books, which enlarge on this thesis, we find an addition -- side by side with the sangha-bhedako is mentioned the stupa-bhedako, the man who breaks open the stupas. The oldest of the passages is the exception referred to. It is in the Mahavastu, certainly the oldest Buddhist Sanskrit text as yet edited, and most probably in its oldest portions older than Asoka. Whether this isolated verse belongs to the oldest portions of the work is doubtful. It says (i, 101):

Sanghan ca te na bhindanti na ca te stupa-bhedaka

Na te Tathagate cittam dusayanti kathancana.

We find these gentlemen, therefore -- the violators of tombs, tomb-riflers -- first mentioned in a way that may or may not, and probably does not, refer to Asoka. In the same connection, that is with the schismatics, they are also mentioned in the Netti Pakarana, p. 93. The editor of this work, Professor Edmond Hardy, dates it about, or shortly after, the beginning of our era. And he was the first to call attention to the mention in these passages of the `tomb-violators' as a test of age.

The next passage will seem more to the point, inasmuch as it mentions both Asoka and the Eight Topes. It is in the Asokavadana, a long legend, or historical romance, about Asoka and his doings, included in the collection of stories called the Divyavadana. These stories are by different authors, and of different dates. The particular one in question mentions kings of the Sunga dynasty, and cannot therefore be much older than the Christian era.(1) [See J.P.T.S., 1899, p. 89] The passage is printed at p. 380 of Professor Cowell and Mr. Neil's edition. The paragraph is unfortunately very corrupt and obscure; but the sense of those clauses most important for our present purpose is clear enough. It begins, in strange fashion, to say, a propos of nothing:--

"Then the King [Asoka], saying, 'I will distribute the relics of the Exalted One,' marched with an armed force in fourfold array, opened the Drona Stupa put up by Ajatasattu, and took the relics."

There must be something wrong here. Ajatasattu's stupa was at Rajagaha, a few miles from Asoka's capital. The Drona Stupa, the one put up over the vessel, was also quite close by.(1) [See Yuan Thsang, chap. vii; Beal, ii, 65.] Whichever is the one referred to, it was easily accessible, and the time given was one of profound peace. Asoka's object in distributing the relics, in the countless stupas he himself was about to build, is represented as being highly approved of by the leaders of the Buddhist order. What, then, was the mighty force to do?

Then the expression Drona Stupa is remarkable. What is probably meant is a stupa over the bushel (drona) of fragments (from the pyre) supposed to have been Ajatasattu's share. But it is extremely forced to call this a Drona Stupa; and Ajatasattu's stupa is nowhere else so called. Burnouf thinks(2) ["Introduction, etc., p. 372.] this is probably a confusion between the name of the measure and the name of the brahmin, Drona, who made the division. The story goes on:

"Having given back the relics, putting them distributively in the place [or the places] whence they had been taken, he restored the stupa. He did the same to the second, and so on till he had taken the seventh bushel [drona];(3) [Bhaktimato is omitted. The discussion of its meaning, irrelevant to the question in hand, is here unnecessary. It is of value for the very important history of bhakti in India.] and restoring the stupas, he then went on to Ramagama."

Here again the story-teller must have misunderstood some phrase in the tradition (probably in some Prakrit or other) which he is reproducing. Asoka did not want to get these relics in order to put them back into the place, or places, they had come from. He wanted, according to the Divya-vadana itself, to put them in his own stupas. We shall see below a possible explanation. The story goes on:--

"Then the king was led down by the Nagas into their abode, and was given to understand that they would pay worship [puja] to it [that is, to the stupa or the portion of relics] there. As soon as that had been grasped by the king, then the king was led up again by the Nagas from their abode."

Their abode, of course, was under the sacred pool at Ramagama, the stupa being on the land above. After stating how Asoka then built 84,000 stupas (in one day!) and distributed the relics among them, the episode closes with the statement that this was the reason why his name was changed from Candasoka to Dharmasoka. Burnouf adds to the confusion with which this part of the story is told through translating (throughout) dharmarajika by 'edicts of the law.' It evidently is an epithet of the stupas. Can we gather from this any hint as to a possible origin of this extraordinary legend?

There is namely a very ancient traditional statistical statement -- so ancient that it is already found in the Thera Gatha. (verse 1022) among the verses attributed to Ananda -- that the number of the sections of the Dhamma (here meaning apparently the Four Nikayas) was 84,000, of which 82,000 were attributed to the master and 2,000 to a disciple.

Dvasiti Buddhato ganhim dve sahassani bhikkhuto

Caturasiti sahassani ye 'me dhamma pavattino.(1) [Quoted Sumangala, i, 24.]

Could it have happened that after the knowledge of the real contents of the Asoka Edicts had passed away, and only the memory of such edicts having been published remained alive, they were supposed to contain or to record the 84,000 traditional sections of the Dhamma? And then that by some confusion, such as that made by Burnouf, between epithets applicable equally to stupas and 'edicts of the law,' the edicts grew into stupas? We cannot tell without other and earlier documents. But this we know, that the funniest mistakes have occurred through the telling in one dialect of traditions received in another; and that the oldest form of the legend of Asoka's stupas is in so late a work that such a transformation had had ample time in which to be brought gradually about.

Such a solution of the mystery how this amazing proposition could have become matter of belief is confirmed by our next authority, the Dipavamsa (vi, 94-vii, 18), which says distinctly that the number of Asoka's buildings was determined by the number of the sections of the Dhamma. But the legend here is quite different. There is no mention of breaking open the eight old stupas. The 84,000 viharas -- they are no longer stupas -- are not built in one day; they take three years to build. It is the dedication festival of each of them that takes place on the same day, and on that day Asoka sees them all at once, and the festivals being celebrated at each. This was the form of the story as believed at Anuradhapura in the early part of the fourth century A.D.

The next book, in point of date, which mentions Asoka in connection with the eight original stupas is Fa Hian (ch. xxiii). The passage runs, in Legge's translation, as follows:--

"When King Asoka came forth into the world he wished to destroy the Eight Topes, and to build instead of them 84,000 topes. After he had thrown down the seven others he wished next to destroy this tope (at Ramagama). But then the dragon (1) [Chinese-English for Naga.] showed itself, and took the king into his palace. And when he had seen all the things provided for offerings, it said to him: 'If you are able with your offerings to exceed these, you can destroy the tope, and take it (2) ["It" must be wrong. What he wanted to take away was the relics. Beal translates, "Let me tale you out," a more likely rendering, and one that would harmonize with the Divyavadana legend as given above.] all away. I will not contend with you.' The king, knowing that such offerings were not to be had anywhere in the world, thereupon returned.

"Afterwards the ground all about became overgrown with vegetation; and there was nobody to sweep and sprinkle about the tope. But a herd of elephants came regularly, which brought water with their trunks to water the ground, and various kinds of flowers and incense which they presented at the tope."

A group of elephants behaving precisely in this way is sculptured on one of the bas-reliefs in the Bharhut Tope (plates xv and xxx in Cunningham).

The pilgrim goes on to say that in recent times a devotee, seeing this, had taken possession of the deserted site.

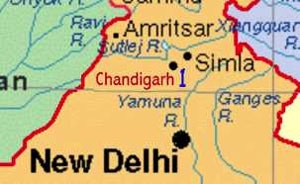

This will probably represent the tradition at the place itself about 400 A.D., or a few years earlier. For Fa Hian left China in 399 A.D., and when he heard this tale at Ramagama it was no doubt already current there. It is good evidence of Ramagama having been very early deserted. Incidentally, its distance east of the Lumbini pillar is given as five yojanas, say thirty-eight miles.

Only twenty or thirty years later is Buddhaghosa's version of the story in the introduction to the Samanta Pasadika, his commentary on the Vinaya, in the portion edited for us by Professor Oldenberg.(1) [Oldenberg's Vinaya iii, 304 foll.] The story is well told, but we need not repeat it, as it reproduces the Dipavamsa version. In both versions the story is used merely as an explanation of the way in which Asoka's son, Mahinda, came to enter the Order. For it is on seeing the glory of the 84,000 festivals that Asoka boasts of his gift. But he is told that the real benefactor is one who gives his son to the Order; and then he, too, has both his son and his daughter initiated. All this is said to have happened after the ninth year of Asoka's reign had expired. We see there is nothing at all in this version about the original eight stupas, or rather seven of them, having been broken open.

But Buddhaghosa has another account in the Sumangala Vilasini, a little later than the last, and in that he introduces an entirely new factor. Here it is not Asoka, but Ajatasattu who gets the relics out of all the eight stupas (except that at Ramagama, which is protected by the Nagas). This he does (twenty years after the Buddha's death, according to Bigandet, ii, 97) on the advice of Maha-kassapa, who was afraid -- it is not stated why -- for their safety. The king agrees to build a shrine for them, but says it is not his business to get relics. The thera then brings them all, and the king buries them in a wonderful subterranean chamber. In the construction of this underground shrine Sakka, the king of the gods, or rather Vissakamma, on his order, assists. And it is there that Asoka, after breaking into all the seven stupas in vain (the Nagas protecting the eighth), finds the relics.(1) [Is it possible that this idea can lie behind the enigmatic expressions given above, p. 401, from the Divyavadana?] These he takes, and restoring the place where he had found them, establishes them in his own 84,000, not stupas, but viharas. It is incidentally mentioned that Rajagaha is 25 yojanas, say 190 miles, from Kusinara.(2) [This harmonizes with the distances given in the Jataka. See my "Buddhist Birth Stories," p. 87.]

The text of this part of the Sumangala has not yet been published. It will appear in the forthcoming edition for the Pali Text Society; and meanwhile an English version of a very late Burmese adaptation of the Pali can be consulted in Bigandet, ii, 131 foll. The legend is here very well and clearly told, and suggests possible explanations of several of the obscurities and inconsistencies in the oldest version in the Divyavadana.

The Mahavamsa (chap. v), which is again a very little later, gives the episode of the 84,000 viharas on the same lines as the Dipavamsa, omitting all reference to the breaking open of the stupas. But it agrees with the Divyavadana in stating (p. 35 of Turnour's edition) that this building of the 84,000 viharas was the reason why the king's name was changed from Asoka(3) [So the text. We ought perhaps to read Candasoka.] to Dhammasoka.

The form of the legend, as thus given in almost identical terms by the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa, is no doubt derived by both from the older Mahavamsa, in Simhalese, then handed down in the Maha Vihara at Anuradhapura, and now lost.

About the same age (412-454 A.D.) is the Chinese work which Mr. Beal translated in vol. xix of the "Sacred Books of the East," and which he calls a translation of Asvaghosa's Buddha-Carita. Were this so, it would be of the first importance for our point. But it is nothing of the kind. There are resemblances, just as there would be if two Christian poets had, in different times and countries, turned the Gospels into rhyme with poetical embellishments. There are still closer resemblances, as if a later poet had borrowed phrases and figures from a previous writer. But there are greater differences. Taking the first chapter as a specimen, the Chinese has 126, the Sanskrit 94 verses. Of these, only about 40 express the same thought, and this is often merely a thought similar because derived from the same old tradition. More than half the verses in the Sanskrit have no corresponding verse in the Chinese, More than two- thirds of the verses in the Chinese have no corresponding verse in the Sanskrit. And even when the verses do, in the main, correspond, there are constant differences in the details and in the wording. It is uncritical, even absurd, to call this a translation.

The blunder of dating the Lalita Vistara in the first century on the ground of a 'translation' into Chinese of that date, rests on a similar misleading use of the word. We know of no such translation in the exact and critical sense. Twenty years ago (Hibbert Lectures, 198 foll.) I called attention to this. But Foucaux's conclusion still sometimes repeated as though it were valid. We must seek for the date of the Lalita Vistara on other and better grounds. Beal's so-called Dhammapada is also a quite different and much later work than the canonical book of which he calls it a version. See the detailed comparative tables ibid., p. 202. Mr. Rockhill, "Life of Buddha," p. 222, says that Beal's Chinese text "could not have been made from the same original" as the Tibetan version of the Buddha-Carita.

It was necessary to point this out as the Chinese book has two verses, of interest in the present discussion, which are not in the Sanskrit. If Beal were right we should have to ascribe them to Asvaghosa.(1) [There are six Asvaghosas mentioned in Chinese works quoted by Mr. Suzuki in his translation of the " Awakening of Faith," p.7.] As it is we are in complete ignorance of the real name and author and date of the original of Beal's Chinese book. We must, therefore, take the opinions expressed in the verses referred to as being good evidence only for the date of the Chinese book itself, only noting the fact that they are taken from some Sanskrit work of unknown date. The verses run, in Beal's words:--

"Opening the dagabas raised by those seven kings to take the Sariras thence, he spread them everywhere, and raised in one day 84,000 towers. (2,297.)

"Only with regard to the eighth pagoda in Ramagrama, which the Naga spirit protected, the king was unable to obtain those relics." (2,298.)

We see from Yuan Thsang's Travels, Book vi (Beal, ii, 26), that this curious story still survived in the seventh century of our era. It is interesting to notice how the legend had, by that time, become rounded off and filled in. Thsang naturally has nothing of the second Ajatasattu episode. He was never in Ceylon, and we have no evidence that this part of the legend was ever current in North India. But he also drops the absurd detail of the 84,000 stupas built in one day; and he fills out the Naga episode, making a very pretty story of it, turning the Naga, when he comes out to talk to the king, into a brahmin, and giving much fuller details of the conversation. He mentions also the interesting fact that in his time there was an inscription at the spot "to the above effect."

Finally, when we come to the Tibetan texts, which are considerably later,(2) [About 850 A.D.: see Rockhill, pp. 218 and 223.] we find an altogether unexpected state of things. We have long abstracts of the account, in the Dulva, of the death and cremation of the Buddha and of the distribution of his relics, from two scholars whose work can be thoroughly relied on, Csoma Korosi(3) ["Asiatic Researches," xx, 309-317.] and W.W. Rockhill.(1) ["Life of Buddha," pp. 122-148, and especially 141-148.] According to both these authorities the Tibetan works follow very closely, not any Sanskrit work known to us, but the Maha-parinibbana Suttanta. Where they deviate from it, it is usually by way of addition; and of addition, oddly enough, again not from any Sanskrit work, but on the lines of the Sumangala Vilasini.

However we try to explain this it is equally puzzling. Could they possibly, in Tibet, and at that time (in the ninth century A.D.), have had Pali books, and have understood them? In discussing another point, Mr. Rockhill (p. ix) thinks that the Tibetan author had access to Pali documents. M. Leon Feer has a similar remark ("Annales," vol. v, PP. xi, 133), and talks at pp. 133, 139, 143, 221, 224, 229, 408, 414 of a Tibetan text as though it were a translation from a Pali one. And the translations he gives, in support of his proposition, certainly, for the most part, show that the texts are the same.(2) [M. Leon Feer has not been able always to give volume and page of the originals of these Tibetan texts, often because they had not been edited. It may be useful, therefore, to point out that his page 145 = Anguttara, 5. 108. " 222 = Ang.5. 342, Jat. 6.14. " 231 = Ang. 4. 55 (which gives better readings), comp. 2. 61. " 293 = Divy. 193, Itiv. 76.] Strange as it may seem, therefore, it is by no means impossible that in our case also the Tibetan depends on a Pali original, or originals. We have at least good authority for a similar conclusion as to other Tibetan writings. And we now know, thanks to Professor Bendall, that a similar conclusion would be possible in Nepal.(3) [J.R.A.S., 1899, p. 422.]

If, on the other hand, our Tibetan texts are based on Sanskrit originals, the difficulty arises whence, at that date, could the Tibetans have procured Sanskrit books adhering so closely to the ancient standpoint.

Rockhill has not even a word about Asoka; Csoma Korosi has only a line, added like a note, at the end of the whole narrative, and saying:--

"The King Mya-nan-met (Asoka), residing at Pataliputta, has much increased the number of Chaityas of the seven kinds."(1) ["Asiatic Researches," xx, 317.]

What, then, are the conclusions to be drawn from our little enquiry?

1. That the breaking open of stupas is not mentioned at all in the most ancient Buddhist literature.

2. That Asoka's doing so is first mentioned in a passage long after his time. This passage is also so curt, self-contradictory: and enigmatic, that we probably have to suppose a confusion arising from difference of dialect. It is of little or no value as evidence that Asoka did actually break open seven of the eight ancient topes.

3. The number of the stupas he is supposed to have built -- 84,000 -- is derived from the traditional number (which is about correct) of the number of sections in the Four Nikayas, that is, in Buddhist phraseology, in the Dhamma. This suggests a possible origin of the whole of the legend.

4. In any case the eighth, that at Ramagama, was untouched. The site of it can be determined within a few miles, as we know, from the passages quoted above, its distance from Rajagaha on the one hand and the Lumbini pillar on the other; and we have, besides, the details as to distance given by the Chinese pilgrims. There was an inscription there, presumably put up by Asoka's orders. It will be most interesting to see if it lends support to, or could have given rise to, the legend.

5. The greatest circumspection must be used in dating any Indian work by the date of an alleged translation into Chinese. Even when a Chinese book is said to have the same title, and even similar chapter-titles, as a Sanskrit or Pali one, it does not follow it is really the same.

6. The Indian pandits who assisted in the ninth century in the translation of Indian books into Tibetan knew not only classical Sanskrit as well as Buddhist Sanskrit, but also Pali. It would be a great service if Tibetan scholars would ascertain exactly which Pali MSS. they had. They certainly had the Paritta; and certain Suttantas from, if not the whole of, the Digha; and certain Suttas from, if not the whole of, the Anguttara and the Samyutta. These books must have been handed down all the time in India; for we know enough of the journey of the emissaries from Tibet to be certain they did not go to Ceylon.

But we must stop. We are here brought face to face with some of the most debated of those larger questions on the solution of which the solution of the problem of the history of Indian thought and literature must ultimately depend. We can only hope in an enquiry like the present to lay one or two very unpolished stones on the foundation of the Dhamma Pasada of history, in which the scholars of a future generation will, we hope, have the good fortune to dwell.