by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/30/20

The move to a bigger property at Dalhousie also allowed for some modest expansion of the school, requiring more volunteers and a gearing up of the administration. Cherry Armstrong, an eighteen-year-old whose mother was active in the Buddhist Society in London, arrived towards the end of the school's first summer in the hills.

Her role was a loosely defined mix of administrative and secretarial, particularly helping with the correspondence generated by the Tibetan Friendship Group and Freda's scheme for pen friends for young Tibetan refugees.The western friend would include a small monetary gift, usually in the form of money orders ... In return the Tibetan pen friend would send a little photograph or a prayer written in Tibetan ... My job initially was to keep this scheme working and it was often a life-saver for individuals with no financial aid. It was a system that needed no overheads -- once the connection was established the money went directly to the person for whom it was intended and usually continued for years.

Freda was good at delegating, and at multitasking. Every morning she 'held court' with a pile of papers (the morning post) on her lap. Tibetan matters were handed over to Trungpa Tulku who acted as her interpreter and scribe (as well as doing his own religious and language studies). Indian matters were handed to the Indian administrator of the school, Attar Singh; English letters were handed to me, while Freda herself would be simultaneously writing her own more important letters. During this time there would be frequent Tibetan or Indian visitors asking for help or for Freda to use her influence on their behalf and everyone was attended to with care and foresight. Sitting beside her whilst all this was going on I could see that her method of coping was to give her undivided attention to the specific matter in hand; a kind of purposeful concentration to the exclusion of all other matters. When one matter was dealt with, the next had her exclusive attention .... She had an immense capacity for work.19

Cherry learnt to type, often with an old typewriter balanced on her lap or on her bed. It was rudimentary but it worked. Alongside the daily grind, Freda was also adept at maintaining connections with those of influence. When a couple of months after the move to Dalhousie Anita Morris headed home to England, she carried a package for Christmas Humphreys, the judge and doyen of the Buddhist Society in London, and for the renowned violinist Yehudi Menuhin.

-- 14: The Young Lamas' Home School, Excerpt from The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

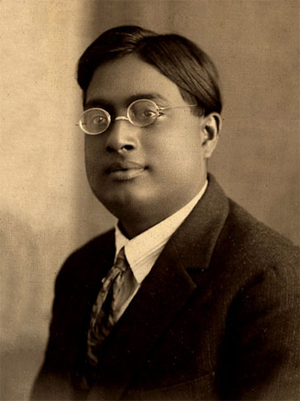

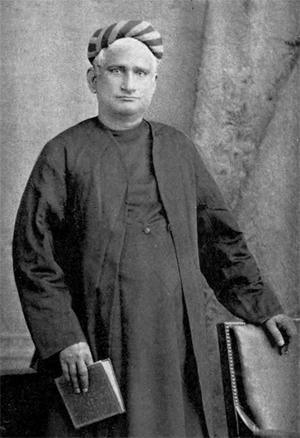

Menuhin in 1937

Yehudi Menuhin, Baron Menuhin, OM KBE (22 April 1916 – 12 March 1999) was an American-born violinist and conductor who spent most of his performing career in Britain. He is widely considered one of the great violinists of the 20th century. He played the Soil Stradivarius, considered one of the finest violins made by Italian luthier Antonio Stradivari.

Early life and career

Menuhin with Bruno Walter (1931)

Yehudi Menuhin was born in New York City to a family of Lithuanian Jews. Through his father Moshe, a former rabbinical student and anti-Zionist,[1] he was descended from a distinguished rabbinical dynasty. In late 1919, Moshe and his wife Marutha (née Sher) became American citizens, and changed the family name from Mnuchin to Menuhin.[2] Menuhin's sisters were concert pianist and human rights activist Hephzibah, and pianist, painter and poet Yaltah.

Menuhin's first violin instruction was at age four by Sigmund Anker (1891–1958);[3] his parents had wanted Louis Persinger to teach him, but Persinger refused. Menuhin displayed exceptional musical talent at an early age. His first public appearance, when he was seven years old, was as solo violinist with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in 1923. Persinger then agreed to teach him and accompanied him on the piano for his first few solo recordings in 1928–29.

Julia Boyd records:

On 12 April 1929 it [the Semperoper] cancelled its advertised programme to make way for a performance by the twelve-year-old Yehudi Menuhin. That night he played the Bach, Beethoven and Brahms violin concertos to an ecstatic audience... The week before, Yehudi had played in Berlin with the Philharmonic under Bruno Walter to an equally rapturous response.[4]

It was said of his Berlin performance: "There steps a fat little blond boy on the podium, and wins at once all hearts as in an irresistibly ludicrous way, like a penguin, he alternately places one foot down, then the other. But wait: you will stop laughing when he puts his bow to the violin to play Bach's violin concerto in E major no.2."[5]

The city of Basel: place of study under the guidance of Adolf Busch

When the Menuhins moved to Paris, Persinger suggested Menuhin go to Persinger's old teacher, Belgian virtuoso and pedagogue Eugène Ysaÿe. Menuhin did have one lesson with Ysaÿe, but he disliked Ysaÿe's teaching method and his advanced age. Instead, he went to Romanian composer and violinist George Enescu, under whose tutelage he made recordings with several piano accompanists, including his sister Hephzibah. He was also a student of Adolf Busch in Basel. He stayed in the Swiss city for a bit more than a year, where he started to take lessons in German and Italian as well.

According to Henry A. Murray, Menuhin wrote:

Actually, I was gazing in my usual state of being half absent in my own world and half in the present. I have usually been able to "retire" in this way. I was also thinking that my life was tied up with the instrument and would I do it justice?

— Yehudi Menuhin, personal communication, 31 October 1993[6]

His first concerto recording was made in 1931, Bruch's G minor, under Sir Landon Ronald in London, the labels calling him "Master Yehudi Menuhin". In 1932 he recorded Edward Elgar's Violin Concerto in B minor for HMV in London, with the composer himself conducting; in 1934, uncut, Paganini's D major Concerto with Emile Sauret's cadenza in Paris under Pierre Monteux. Between 1934 and 1936, he made the first integral recording of Johann Sebastian Bach's sonatas and partitas for solo violin, although his Sonata No. 2, in A minor, was not released until all six were transferred to CD.

His interest in the music of Béla Bartók prompted him to commission a work from him – the Sonata for Solo Violin, which, completed in 1943 and first performed by Menuhin in New York in 1944, was the composer's penultimate work.

World War II musician

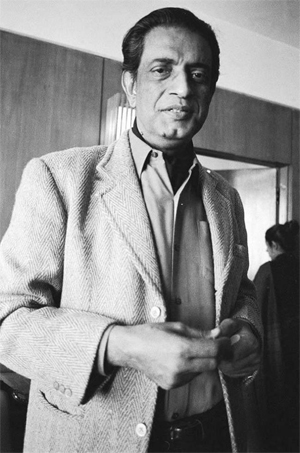

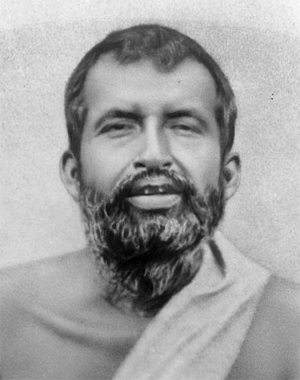

Menuhin in 1943

He performed for Allied soldiers during World War II [over 500 concerts for wounded servicemen and Allied troops] and, accompanied on the piano by English composer Benjamin Britten, for the surviving inmates of a number of concentration camps in July 1945 after their liberation in April of the same year, most famously the Bergen-Belsen. He returned to Germany in 1947 to play concerto concerts with the Berlin Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwängler as an act of reconciliation, the first Jewish musician to do so in the wake of the Holocaust, saying to Jewish critics that he wanted to rehabilitate Germany's music and spirit.

He and Louis Kentner (brother-in-law of his wife, Diana) gave the first performance of William Walton's Violin Sonata, in Zürich on 30 September 1949. He continued performing, and conducting (such as Bach orchestral works with the Bath Chamber Orchestra), to an advanced age, including some nonclassical music in his repertory.

World interactions

For Menuhin's notable students, see List of music students by teacher: K to M § Yehudi Menuhin.

Menuhin credited German philosopher Constantin Brunner with providing him with "a theoretical framework within which I could fit the events and experiences of life".[7]

Following his role as a member of the awards jury at the 1955 Queen Elisabeth Music Competition, Menuhin secured a Rockefeller Foundation grant for the financially strapped Grand Prize winner at the event, Argentine violinist Alberto Lysy. Menuhin made Lysy his only personal student, and the two toured extensively throughout the concert halls of Europe. The young protégé later established the International Menuhin Music Academy (IMMA)[8] in Gstaad, in his honor.[9]

Menuhin made several recordings with the German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, who had been criticized for conducting in Germany during the Nazi era. Menuhin defended Furtwängler, noting that the conductor had helped a number of Jewish musicians to flee Nazi Germany.

Furtwängler made his London debut in 1924, and continued to appear there before the outbreak of World War II as late as 1938, when he conducted Richard Wagner's Ring [Die Nibelungen]...

On 10 April 1933, Furtwängler wrote a public letter to Goebbels ...

"If the fight against Judaism concentrates on those artists who are themselves rootless and destructive and who seek to succeed in kitsch, sterile virtuosity and the like, then it is quite acceptable; the fight against these people and the attitude they embody (as, unfortunately, do many non-Jews) cannot be pursued thoroughly or systematically enough. If, however, this campaign is also directed at truly great artists, then it ceases to be in the interests of Germany's cultural life [...] It must therefore be stated that men such as Walter, Klemperer, Reinhardt etc. must be allowed to exercise their talents in Germany in the future as well, in exactly the same way as Kreisler, Huberman, Schnabel and other great instrumentalists of the Jewish race"...

Goebbels and Göring ordered their administration to listen to Furtwängler's requests...

The violinist Yehudi Menuhin was, with Arnold Schoenberg, Bronisław Huberman, and Nathan Milstein, among the Jewish musicians who had a positive view of Furtwängler. In February 1946, he sent a wire to General Robert A. McClure in February 1946:

"Unless you have secret incriminating evidence against Furtwängler supporting your accusation that he was a tool of Nazi Party, I beg to take violent issue with your decision to ban him. The man never was a Party member. Upon numerous occasions, he risked his own safety and reputation to protect friends and colleagues. Do not believe that the fact of remaining in one's own country is alone sufficient to condemn a man. On the contrary, as a military man, you would know that remaining at one's post often requires greater courage than running away. He saved, and for that we are deeply his debtors, the best part of his own German culture... I believe it patently unjust and most cowardly for us to make of Furtwängler a scapegoat for our own crimes."...

At the end of his life, Yehudi Menuhin said of Furtwängler, "It was his greatness that attracted hatred".

-- Wilhelm Furtwängler, by Wikipedia

In 1957, he founded the Menuhin Festival Gstaad in Gstaad, Switzerland. In 1962, he established the Yehudi Menuhin School in Stoke d'Abernon, Surrey. He also established the music program at The Nueva School in Hillsborough, California, sometime around then. In 1965 he received an honorary knighthood from the British monarchy. In the same year, Australian composer Malcolm Williamson wrote a violin concerto for Menuhin. He performed the concerto many times and recorded it at its premiere at the Bath Festival in 1965. Originally known as the Bath Assembly,[10] the festival was first directed by the impresario Ian Hunter in 1948. After the first year the city tried to run the festival itself, but in 1955 asked Hunter back. In 1959 Hunter invited Menuhin to become artistic director of the festival. Menuhin accepted, and retained the post until 1968.[11]

Menuhin also had a long association with Ravi Shankar, beginning in 1966 with their joint performance at the Bath Festival and the recording of their Grammy Award-winning album West Meets East (1967). During this time, he commissioned composer Alan Hovhaness to write a concerto for violin, sitar, and orchestra to be performed by himself and Shankar. The resulting work, entitled Shambala (c. 1970), with a fully composed violin part and space for improvisation from the sitarist, is the earliest known work for sitar with western symphony orchestra, predating Shankar's own sitar concertos, but Menuhin and Shankar never recorded it. Menuhin also worked with famous jazz violinist Stéphane Grappelli in the 1970s on Jalousie, an album of 1930s classics led by duetting violins backed by the Alan Claire Trio.

In 1975, in his role as president of the International Music Council, he declared October 1 as International Music Day. The first International Music Day, organised by the International Music Council, was held that same year, in accordance with the resolution taken at the 15th IMC General Assembly in Lausanne in 1973.[12]

In 1977, Menuhin and Ian Stoutzker founded the charity Live Music Now, the largest outreach music project in the UK. Live Music Now pays and trains professional musicians to work in the community, bringing the experience to those who rarely get an opportunity to hear or see live music performance. At the Edinburgh Festival Menuhin premiered Priaulx Rainier's violin concerto Due Canti e Finale, which he had commissioned Rainier to write. He also commissioned her last work, Wildlife Celebration, which he performed in aid of Gerald Durrell's Wildlife Conservation Trust.

In 1983, Menuhin and Robert Masters founded the Yehudi Menuhin International Competition for Young Violinists, today one of the world's leading forums for young talent. Many of its prizewinners have gone on to become prominent violinists, including Tasmin Little, Nikolaj Znaider, Ilya Gringolts, Julia Fischer, Daishin Kashimoto and Ray Chen.

In the 1980s, Menuhin wrote and oversaw the creation of a "Music Guides" series of books; each covered a musical instrument, with one on the human voice. Menuhin wrote some, while others were edited by different authors.

In 1991, Menuhin was awarded the prestigious Wolf Prize by the Israeli Government. In the Israeli Knesset he gave an acceptance speech in which he criticised Israel's continued occupation of the West Bank:

This wasteful governing by fear, by contempt for the basic dignities of life, this steady asphyxiation of a dependent people, should be the very last means to be adopted by those who themselves know too well the awful significance, the unforgettable suffering of such an existence. It is unworthy of my great people, the Jews, who have striven to abide by a code of moral rectitude for some 5,000 years, who can create and achieve a society for themselves such as we see around us but can yet deny the sharing of its great qualities and benefits to those dwelling amongst them.[13]

Later career

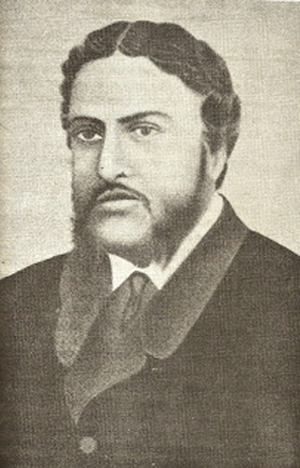

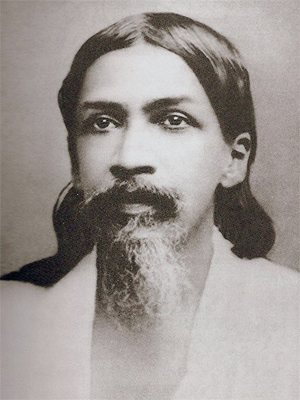

Stéphane Grappelli (left) with Menuhin in 1976

Menuhin regularly returned to the San Francisco Bay Area, sometimes performing with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. One of the more memorable later performances was of Edward Elgar's Violin Concerto, which Menuhin had recorded with the composer in 1932.

On 22 April 1978, along with Stéphane Grappelli, Yehudi played Pick Yourself Up, taken from the Menuhin & Grappelli Play Berlin, Kern, Porter and Rodgers & Hart album as the interval act at the 23rd Eurovision Song Contest for TF1. The performance came direct from the studios of TF1 and not that of the venue (Palais des Congrès), where the contest was being held.

Menuhin hosted the PBS telecast of the gala opening concert of the San Francisco Symphony from Davies Symphony Hall in September 1980.

His recording contract with EMI lasted almost 70 years and is the longest in the history of the music industry. He made his first recording at age 13 in November 1929, and his last in 1999, when he was nearly 83 years old. He recorded over 300 works for EMI, both as a violinist and as a conductor. In 2009 EMI released a 51-CD retrospective of Menuhin's recording career, titled Yehudi Menuhin: The Great EMI Recordings. In 2016, the Menuhin centenary year, Warner Classics (formerly EMI Classics) issued a milestone collection of 80 CDs entitled The Menuhin Century, curated by his long-time friend and protégé Bruno Monsaingeon, who selected the recordings and sourced rare archival materials to tell Menuhin's story.

In 1990 Menuhin was the first conductor for the Asian Youth Orchestra which toured around Asia, including Japan, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong with Julian Lloyd Webber and a group of young talented musicians from all over Asia.

Personal life

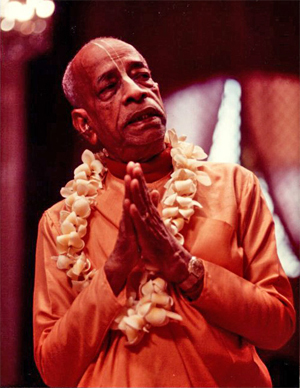

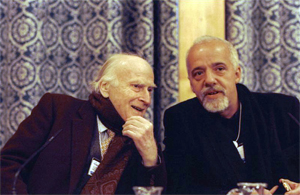

Menuhin and author Paulo Coelho in 1999 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland

Menuhin was married twice, first to Nola Nicholas, daughter of an Australian industrialist and sister of Hephzibah Menuhin's first husband Lindsay Nicholas. They had two children, Krov and Zamira (who married pianist Fou Ts'ong). Following their 1947 divorce he married the British ballerina and actress Diana Gould, whose mother was the pianist Evelyn Suart and stepfather was Admiral Sir Cecil Harcourt.

Admiral Sir Cecil Halliday Jepson Harcourt GBE KCB (11 April 1892 – 19 December 1959) was a British naval officer. He was the de facto governor of Hong Kong as commander-in-chief and head of the military administration from September 1945 to June 1946. He was called by the Chinese name "Ha Kok", a reference to the fourth-century Chinese nobleman Chung Kok... On 18 December 1945, he was made a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB). In 1946, he was promoted to vice-admiral.

-- Cecil Harcourt, by Wikipedia

The couple had two sons, Gerard, notable as a Holocaust denier and far right activist, and Jeremy, a pianist. A third child died shortly after birth.

Gerard Menuhin (born 1948 in Scotland) is a Holocaust denier and far-right activist, associated with the neo-Nazi movement in Germany.

His book Tell the Truth and Shame the Devil, published in 2015, argues that the Holocaust is "the biggest lie in history", that Jews are an "alien, demonic force which seeks to dominate the world", that Jews are flooding Europe with non-white races, to create a "society of racial mongrels, under the rule of a “new Jewish nobility”", and plan to create a one-world government. Menuhin argues that "the world owes Adolf Hitler an apology".

He is the son of the violinist Yehudi Menuhin and dancer Diana Gould, and brother of pianist Jeremy Menuhin.

-- Gerard Menuhin, by Wikipedia

The name Yehudi means "Jew" in Hebrew. In an interview republished in October 2004, he recounted to New Internationalist magazine the story of his name:

Obliged to find an apartment of their own, my parents searched the neighbourhood and chose one within walking distance of the park. Showing them out after they had viewed it, the landlady said: "And you'll be glad to know I don't take Jews." Her mistake made clear to her, the antisemitic landlady was renounced, and another apartment found. But her blunder left its mark. Back on the street my mother made a vow. Her unborn baby would have a label proclaiming his race to the world. He would be called "The Jew".[14]

Menuhin died in Martin Luther Hospital[15] in Berlin, Germany, from complications of bronchitis. Soon after his death, the Royal Academy of Music acquired the Yehudi Menuhin Archive, which includes sheet music marked up for performance, correspondence, news articles and photographs relating to Menuhin, autograph musical manuscripts, and several portraits of Paganini.[16]

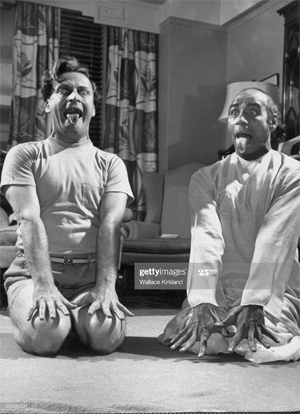

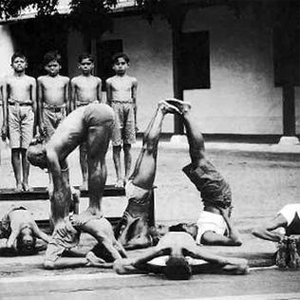

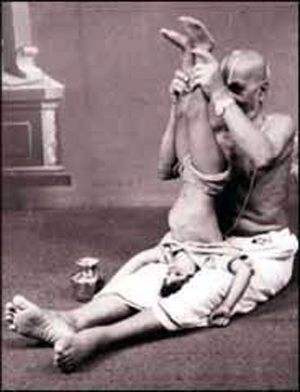

Interest in yoga

Collection: The LIFE Picture Collection

Date created: January 01, 1953

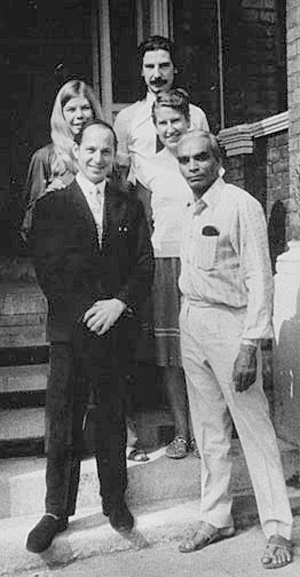

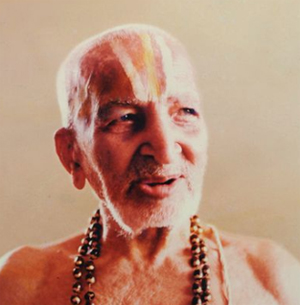

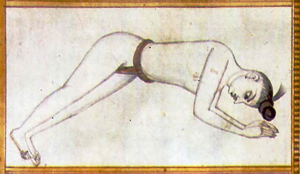

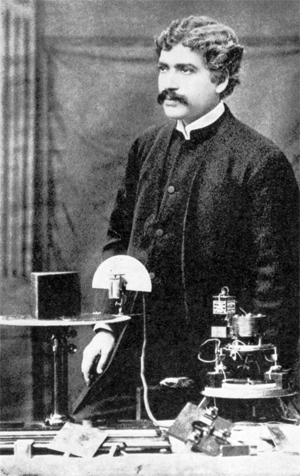

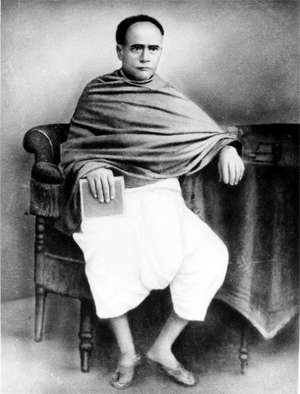

In 1953, Life published photos of him in various esoteric yoga positions.[17] In 1952, Menuhin was in India, where Nehru, the new nation's first Prime Minister, introduced him to an influential yogi B. K. S. Iyengar, who was largely unknown outside the country.[17] Menuhin arranged for Iyengar to teach abroad in London, Switzerland, Paris, and elsewhere. He became one of the first prominent yoga masters teaching in the West.

Menuhin also took lessons from Indra Devi, who opened the first yoga studio in the U.S. in Los Angeles in 1948.[18]

Her first spiritual awakening happened while attending a gathering of Theosophists in Ommen in the Netherlands in 1926, to listen to Jiddu Krishnamurti. Devi was moved, became a vegetarian, and traveled to the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar, India.

-- Indra Devi, by Theosophy Wiki

Krishna[murti] visited Aldous Huxley, who was glad to see him. Huxley described him as looking well, but curiously different from former times, for he was now "a small bright old man, with a bald head ringed by white hair." Huxley made plans to hear Krishna's talks in Gstaad, Krishna's destination after London. Vanda Scaravelli met Krishna in Geneva and from there they went on to a chalet she rented at Gstaad, near Saanen. He gave talks in the Saanen Town Hall to about 350 people at gatherings which would become an annual event.

Krishna's process was ongoing in Saanen. In his Notebook on 13 July 1961 he wrote sagely that the urge for repetition of a pleasant experience was the soil in which sorrow grew, and the brain had to stop making its own ways and become passive. On 16 July he described a sacredness or power that filled the room, which Vanda also felt. This was what everyone craved -- monk, priest, sannyasi -- and because they craved it, it eluded them. Vanda also wrote about her experience of Krishna's 'process.' He fainted and there was a change in his face, his eyes becoming larger. Then she felt a powerful "presence" of another dimension -- simultaneously empty and full. Krishna did allow Vanda to touch him during the experience, she said, but no one else. Again, the next day, Vanda took notes to explain to Krishna what happened when he "went off."

Aldous Huxley and his second wife, Laura, visited Gstaad to hear Krishna speak several times at the end of July 1961, along with Huxley's friend, Yehudi Menuhin. Huxley said the talks were among the most impressive things he'd ever listened to. He likened the experience to that of listening to a discourse by the Buddha: "such power, such intrinsic authority, such an uncompromising refusal to allow the homme moyen sensual any escapes or surrogates, any gurus, saviours, fuhrers, churches." Krishna showed one how to end sorrow but if one didn't choose to fulfil these conditions, sorrow would continue indefinitely.

-- Jiddu Krishnamurti: World Philosopher (1895-1986): His Life and Thoughts, by C. V. Williams

Precisely because Huxley was plugged into the transcendental, his prose had power to liberate. You have to know that there actually is a transcendental something, if you are going to free anybody from anything -- if there is no beyond-the-given, there is no freedom from the given, and liberation is futile. Today's postmodern writers, who hug the given, stick to the obvious, cling to the shadows, celebrate the surface, have nowhere else to go, and so emancipation is the last of what they offer ... or you get.

No wonder that one of Aldous's best friends for several decades was Krishnamurti (the sage on whom I cut my spiritual teeth). Krishnamurti was a supreme liberator, at least on occasion, and in books such as "Freedom from the Known," this extraordinary sage pointed to the power of nondual choiceless awareness to liberate one from the binding tortures of space, time, death, and duality. When Huxley's house (and library) burned down, the first books he asked to be replaced were Krishnamurti's "Commentaries on Living."

Yehudi Menuhin wrote of Aldous: "He was scientist and artist in one -- standing for all we most need in a fragmented world where each of us carries a distorting splinter out of some great shattered universal mirror. He made it his mission to restore these fragments and, at least in his presence, men were whole again. To know where each splinter might belong one must have some conception of the whole, and only a mind such as Aldous's, cleansed of personal vanity, noticing and recording everything, and exploiting nothing, could achieve so broad a purpose."

-- One Taste: Daily Reflections on Integral Spirituality, by Ken Wilber, Shambhala Publications

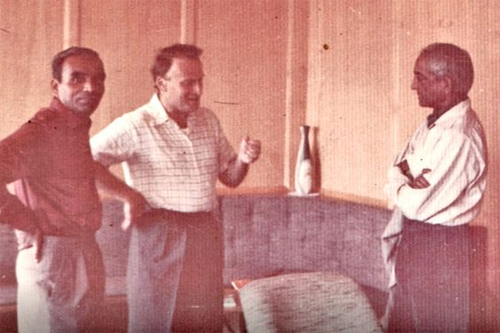

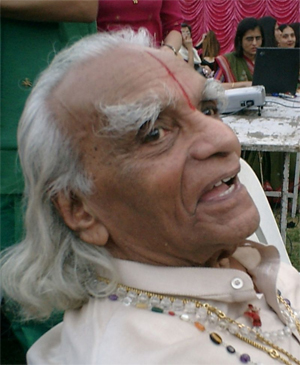

1940s BKS Iyengar, Jiddu Krishnamurti and Yehudi Menuhin

Both Devi and Iyengar were students of Krishnamacharya, a famous yoga master in India.

Violins

Menuhin used a number of famous violins, arguably the most renowned of which is the Lord Wilton Guarnerius 1742. Others included the Giovanni Bussetto 1680, Giovanni Grancino 1695, Guarneri filius Andrea 1703, Soil Stradivarius, Prince Khevenhüller 1733 Stradivari, and Guarneri del Gesù 1739.

In his autobiography Unfinished Journey Mehunin wrote: "A great violin is alive; its very shape embodies its maker's intentions, and its wood stores the history, or the soul, of its successive owners. I never play without feeling that I have released or, alas, violated spirits."[19]

Awards and honours

• Freedom of the City (Edinburgh, Scotland, 1965).

• Appointed to the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1965. At the time of his appointment, he was an American citizen. As a result, his knighthood was honorary and he was not entitled to use the style 'Sir'. In 1993, he became The Right Honourable The Lord Menuhin, OM, KBE (see below).[20][21]

• The Jawaharlal Nehru Award for International Understanding (1968).[22]

• Became President of the International Music Council (1969–1975)[23]

• Became President of Trinity College of Music (now Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance), 1970.[24]

• The Léonie Sonning Music Prize (Denmark, 1972).

• Nominated as president of the Elgar Society (1983).

• The Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (1984).

• The Kennedy Center Honors (1986).

• Appointed as a member of the Order of Merit (1987).[25]

• His recording of Edward Elgar's Cello Concerto in E minor with Julian Lloyd Webber won the 1987 BRIT Award for Best British Classical Recording (BBC Music Magazine named this recording "the finest version ever recorded").

• The Glenn Gould Prize (1990), in recognition of his lifetime of contributions.

• Wolf Prize in Arts (1991).

• Ambassador of Goodwill (UNESCO, 1992).

• On 19 July 1993, Menuhin was made a life peer, as Baron Menuhin, of Stoke d'Abernon in the County of Surrey.[26][27]

• Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship the highest honour conferred by Sangeet Natak Akademi, India's National Academy for Music, Dance and Drama (1994).[28]

• The Konex Decoration (Konex Foundation, Argentina, 1994).

• The Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold of the United Nations Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin (1997).

• Honorary Doctorates from 20 universities, including Oxford, Cambridge, St Andrews, Vrije Universiteit Brussel and the University of Bath (1969).[29]

• The room in which concerts and performances are held at the European Parliament in Brussels is named the "Yehudi Menuhin Space".

• Menuhin was honored as a "Freeman" of the cities of Edinburgh, Bath, Reims and Warsaw.

• He held the Gold Medals of the cities of Paris, New York and Jerusalem.

• Honorary degree from Kalamazoo College.[30]

• Elected an Honorary Fellow of Fitzwilliam College in 1991.

• He received the 1997 Prince of Asturias Award in the Concord category along with Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich.

• In 1997, he received the Grand Cross 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

• On 15 May 1998, Menuhin received the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint James of the Sword (Portugal).[31]

Coat of arms of Yehudi Menuhin

Crest

Out of an eastern crown Or inscribed on either side with a crotchet rest a sharp semi-quaver a flat and semi-quaver rest Sable a pair of cubit arms Proper supporting a terrestrial globe the land Vert fimbriated Or the sea Azure.

Escutcheon

Azure four bendlets between as many violin bridges Gold.

Supporters

On either side a representation of a firebird à la Benois wings elevated and addorsed Gules beaked and membered with wings tipped Or the tail Bleu Celeste that to the dexter Gorged with a chain Or pendent therefrom a hurt fimbriated and charged with a menorah Or the candles Argent enflamed Proper that to the sinister gorged with a like chain pendent therefore a bezant charged with a representation of the gypsy flag mon Proper the compartment a grassy mound with bluebells and blue poppies growing therefrom all Proper with at the centre thereof a plough Gold.[32]

Cultural references

• The catchphrase "Who's Yehoodi?" popular in the 1930s and 1940s was inspired by Menuhin's guest appearance on a radio show, where Jerry Colonna turned "Yehoodi" into a widely recognized slang term for a mysteriously absent person. It eventually lost all of its original connection with Menuhin.

• Menuhin was also "meant" to appear on The 1971 Morecambe and Wise Christmas Show but could not do so as he was "opening at the Argyle Theatre, Birkenhead in Old King Cole". He was replaced by Eric Morecambe in the famous "Grieg's Piano Concerto by Grieg" sketch featuring the conductor André Previn; he was also invited to appear on their 1973 Christmas Show to play his "banjo" as they said playing his violin would not be any good; he ruefully said that "I can't help you".

• A picture of Menuhin as a child is sometimes used as part of a Thematic Apperception Test.[33]

Bibliography

• Rolfe, Lionel Menuhin (2014). The Menuhins: A Family Odyssey. Los Angeles: Createspace. ISBN 978-1-4414-9399-6.

• Menuhin, Diana (1984). Fiddler's Moll. Life With Yehudi. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-28819-0.

• Menuhin, Yehudi (1977). Unfinished Journey. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-41051-3.

• Menuhin, Yehudi (1997). Unfinished Journey: Twenty Years Later. New York: Fromm Intl. ISBN 0-88064-179-7.

• L. Subramaniam, Y. Menuhin; Directed by Jean Henri Meunier (1999). Violin From the Heart (DVD).

• Bailey, Philip (2008). Yehudiana – Reliving the Menuhin Odyssey|Book One. Australia: Fountaindale Press. ISBN 978-0-9804499-0-7.

• Bailey, Philip (2010). Yehudiana – Reliving the Menuhin Odyssey Book Two. Australia: Fountaindale Press. ISBN 978-0-9804499-1-4.

• Burton, Humphrey (2000). Yehudi Menuhin: a life. Northeastern. ISBN 978-1-55553-465-3.

Films

• 1943 – Menuhin was a featured performer in the 1943 film, Stage Door Canteen. Introduced only as "Mr. Menuhin," he performed two violin solos, "Ave Maria" and "Flight of the Bumble Bee" for an audience of servicemen, volunteer hostesses and celebrities from stage and screen.

• 1946 – Menuhin supplied the violin solos in the film The Magic Bow.

• 1979 – The Music of Man (television series)

• The Mind of Music

References

1. Jacqueline Kent, An Exacting Heart: The Story of Hephzibah Menuhin, pp. 11, 158, 190

2. Jacqueline Kent, An Exacting Heart: The Story of Hephzibah Menuhin, p. 18

3. "Sigmund Anker". Find a Grave. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

4. Julia Boyd, Travellers in the Third Reich, Elliott and Thompson Limited, London, 2018, ISBN 978-1-78396-381-2, page 73, paraphrasing Edward Sackville-West

5. Unnamed critic in the Berliner Zeitung, 12 April 1929, quoted in translation in Boyd, page 73

6. Hindle, Kevin; Klyver, Kim (1 January 2011). Handbook of Research on New Venture Creation. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-85793-306-5.

7. Conversations with Menuhin: 32–34

8. "International Menuhin Music Academy". menuhinacademy.ch. Gstaad. 2019. Retrieved 18 November2019.

9. "Alberto Lysy: maestro busca talentos". lanacion.com.ar. 18 July 2004. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

10. "The Third Bath Assembly – Festival of the Arts". The Canberra Times. 18 April 1950. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

11. Bullamore, Tim (1999). Fifty Festivals. Mushroom Books. ISBN 978-1-899142-29-3. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

12. "International Music Day". International Music Council.

13. "Wolf Prize winner raps government". Jerusalem Post, 6 May 1991.

14. "Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999)". New Internationalist. 2 October 2004. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

15. Kozinn, Allan (13 March 1999). "Sir Yehudi Menuhin, Violinist, Conductor and Supporter of Charities, Is Dead at 82". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

16. Yehudi Menuhin Archive Saved For The Nation Archived27 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine 26 February 2004, TourDates.Co.UK, retrieved 28 September 2013.

17. Rolfe, Lionel (17 April 2015). "Indra Devi Was Not Just a Nice Old Lady". Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

18. Martin, Douglas (30 April 2002). "Indra Devi, 102, Dies; Taught Yoga to Stars and Leaders". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

19. Faber, Tony (2004). Stradivari's Genius: Five Violins, One Cello, and Three Centuries of Enduring Perfection. Random House. ISBN 1588362140. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

20. "No. 53332". The London Gazette (Supplement). 11 June 1993. p. 1.

21. Velde, François. "British and Other Honours in Music". Heraldica. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

22. "List of the recipients of the Jawaharlal Nehru Award". ICCRwebsite. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

23. "Current and Past Presidents". International Music Council. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

24. "History of Trinity Laban". Trinity Laban website. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

25. "No. 50849". The London Gazette. 3 March 1987. p. 2855.

26. "No. 53379". The London Gazette. 22 July 1993. p. 12287.

27. "Sir Yehudi Menuhin, Baron Menuhin". thepeerage.com. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

28. "SNA: List of Sangeet Natak Akademi Ratna Puraskarwinners (Akademi Fellows)". Official website. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

29. "Corporate Information". bath.ac.uk.

30. "History – Kalamazoo College".

31. "Cidadãos Estrangeiros Agraciados com Ordens Portuguesas" [Foreign Citizens Granted with Portuguese Orders] (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Presidência da República Portuguesa. Retrieved 19 March 2017. Search result for "Yehudi Menuhin".

32. Debrett's Peerage. 2000.

33. "A young boy is contemplating a violin..." University of Tennessee. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

External links

• Official website

• Yehudi Menuhin performing works by Bach, Bartók, Lalo, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Paganini and Tchaikovsky on Archive.org

• Yehudi Menuhin interview, 31 January 1987

• Text and pictures from Yehudi Menuhin by french film director Bruno Monsaingeon

• Yehudi Menuhin's life in Alma

• Yehudi Menuhin Collection (ARS.0040), Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound