Notes to Arrian's Indica. [See translation of the Indica in the Indian Antiquary, ante, pp. 85-108. The main object of the Notes is to show how the localities, &c. mentioned m the text have been identified. In drawing them up I have derived great assistance from C. Muller's Geographi Graeci Minores, -- a work which contains the text of the Indica with notes, -- Dr. Smith's Dictionary of Classical Geography, and General Cunningham's Geography of Ancient India.]

by J.W. McCrindle, M.A., Patna College

December, 1876

Arrian, distinguished as a philosopher, a statesman, a soldier, and an historian, was born in Nicomedia, in Bithynia, towards the end of the first century. He was a pupil of the philosopher Epictetus, whose lectures he published. His talents recommended him to the favour of Antoninus Pius, by whom, he was raised to the consulship (A.D. 146). In his later years he retired to his native town, where he applied his, leisure to the composition of works on history. He died at an advanced age, in the reign of the emperor Marcus Aurelius. The work by which he is best known is his account of the Asiatic expedition of Alexander the Great, which is remarkable alike for accuracy, and the Xenophontic ease and clearness of its style. His work on India ([x] or [x]) may be regarded as a continuation of his Anabasis. It is not written, however, like the Anabasis, in the Attic dialect, but in the Ionic. The reason may have been that he wished his work to supersede the old and less accurate account of India written in Ionic by Ktesias of Knidos.

The Indica consists of three parts: -- the first gives a general description of India based chiefly on the accounts of the country given by Megasthenes and Eratosthenes (chaps. i.—xvii.); the second gives an account of the voyage made by Nearchus the Cretan from the Indus to the Pasitigris, based entirely on the narrative of the voyage written by Nearchus himself (chaps. xviii.—xlii.); the third contains a collections of proofs to show that the southern parts of the world are uninhabitable on account of the great heat (chap. xlii. to the end).

Chap. I. The river Kophen. -- Another form of the name, used by Strabo, Pliny, &c., is Kophes, -etis. It is now the Kabul river. In chap. iv. Arrian gives the names of its tributaries as the Malantos (Malamantos), Soastos, and Garroias. In the 6th book of the Mahabharata three rivers are named which probably correspond to them—the Suvastu, Gauri,, and Kamana. The Soastos is no doubt the Suvastu, and the Garaea the Gauri. Curtius and Strabo call the Suastus the Choaspes. According to Mannert the Suastus and the Garaea or Guraeus were identical. Lassen [Ind. Alterthums. (2nd ed.). II.673ff.] would, however, identify the Suastos with the modern Suwad or Svat, and the Garaeus with its tributary the Panjkora; and this this is the view adopted by General Cunningham. The Malamantos some would identify with the Choes (mentioned by Arrian, Anabasis IV. 25), which is probably represented by the modern Kameh or Khonar, the largest of the tributaries of the Kabul; others, however, with the Panjkora. General Cunningham, on the other hand, takes it to be the Bara, a tributary which joins the Kabul from the south. With regard to the name Kophes he remarks: -- "The name of Kophes is as old as the time of the Vedas in which the Kubha river is mentioned [Roth first pointed this out; -- conf. Lassen, ut sup. -- Ed.] as an affluent of the Indus; and, as it is not an Aryan word, I infer that the name must have been applied to the Kabul river before the Aryan occupation, or at least as early as B.C. 2500. In the classical writers we find the Choes, Kophes, and Choaspes rivers to the west of the Indus; and at the present day we have the kunar, the Kuram, and the Gomal rivers to the west, and the Kunihar river to the east of the Indus, -- all of which are derived from the Scythian ku, 'water.' It is the guttural form of the Assyrian hu in 'Euphrates,' and 'Eulaeus,' and of the Turki suand the Tibetan chu, all of which mean 'water' or 'river.'" Ptolemy the Geographer mentions a city called Kabara situated on the banks of the Kophen, and a people called Kabolitae.

Astakenoi and Assakenoi. -- It is doubtful whether these were the same or different tribes. It has been conjectured, from some slight resemblance in the name, that they may have been the ancestors of the Afghans. Their territory lay between the Indus and the Kophen, extending from their junction as far westward as the valley of the Guraios or Panjkora. Other tribes in these parts were the Masiani, Nysaei, and Hippasii.

Nysa, being the birth-place of Bacchus, was, as is well known, bestowed as a name on various places noted for the cultivation of the vine. General Cunningham refers its site to a point on the Kophes above its junction with the Choes. The city may, however, have existed only in fable. [Lassen, u. s. 141, 681.]

Massaka (other forms are Massaga, Masaga, and Mazaga.)—The Sanskrit Masaka, near the Gauri, already mentioned. Curtius states that it was defended by a rapid river on its eastern side. When attacked by Alexander, it held out for four days against all his assaults.

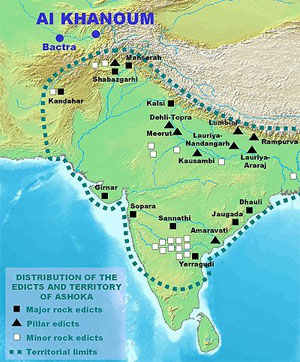

Peukelaitis (other forms—Peukelaetis, Peukolitae, Peukelaotis): —'‘The Greek name,” says General Cunningham, “of Peukelaotis or Peukolaitis was immediately derived from Pukkalaoti, which is the Pali or spoken form of the Sanskrit Pushkalavati. It is also called Peukelas by Arrian, and the people are named Peukalei by Dionysius Periegetes, which are both close transcripts of the Pali Pukkala. The form of Proklois, which is found in Arrian’s Periplus of the Erythroean Sea and also in Ptolemy’s Geography, is perhaps only an attempt to give the Hindi name of Pokhar, instead of the Sanskrit Pushkara." The same authority fixes its position at “the two large towns Parang and Charsada, which form part of the well-known Hashtnagar, or ‘eight cities,’ that are seated close together on the eastern bank of the lower Swat river.” The position indicated is nearly seventeen miles to the north-east of Peshawar. Pushkala, according to Prof. Wilson, is still represented by the modern Pekhely or Pakholi, in the neighhourhood of Peshawar. The distance of Peukelaitis from Taxila (now represented by the vast ruins of Manikyala) is given by Pliny at sixty miles.

CHAP. II.-- Parapamisos (other forms— Paropamisos, Paropamissos, Paropanisos). This denotes the great mountain range now called Hindu Kush, supposed to be a corrupted form of “Indicus Caucasus,” the name given to the range by the Macedonians, either to flatter Alexander, or because they regarded it as a continuation of Caucasus. Arrian, however, and others held it to be a continuation of Taurus. The mountains belonging to the range which lie to the north of the Kabul river are called Nishadha, a Sanskrit word which appears perhaps in the form Paropanisus, which is that given by Ptolemy. According to Pliny, the Scythians called Mount Caucasus Graucasis, a word which represents the Indian name of Paropamisos, Gravakshas, which Ritter translates "splendentes rupium montes." According to General Cunningham, the Mount Paresh or Aparasin of the Zendavesta corresponds with the Paropamisos of the Greeks. In modern maps Hindu Kush generally designates the eastern part of the range, and Paropamisos the western. According to Sir Alexander Burnes, the name Hindu Kush is unknown to the Afghans, but there is a particular peak and also a pass bearing that name between Afghanistan and Turkestan.

Emodos (other forms—Emoda, Emodon, Hemodes).—The name generally designated that part of the Himalayan range which extended along Nepal and Bhutan and onward towards the ocean. Lassen derives the word from the Sanskrit haimavata, in Prakrit haimota, 'snowy.’ If this be so, ‘Hemodos” is the more correct form. Another derivation refers the word to “hemadri" (hema, gold, and adri, mountain), 'the golden mountains,’—so called either because they were thought to contain gold mines, or because of the aspect they presented when their snowy peaks reflected the golden effulgence of sunset.

Imaus.—Related to the Sanskrit himavata, 'snowy.’ The name was applied at first by the Greeks to the Hindu Kush and the Himalayas, but was in course of time transferred to the Bolor range. This chain, which runs north and south, was regarded by the ancients as dividing Northern Asia into “Scythia intra Imaum’’ and “Scythia extra Imaum,” and it has formed for ages the boundary between China and Turkestan. Pliny calls Imaus a 'promontorium' of the Montes Emodi, stating at the same time that in the language of the inhabitants the name means 'snowy.’

Pattala.—The name of the Delta was properly Patalene, and Patala was its capital. This was situated at the head of the Delta, where the western stream of the Indus bifurcated. Thatha has generally been regarded as its modern representative, but General Cunningham would "almost certainly" identify it with Nirankol or Haidarabad, of which Patalpur and Patasila ('flat rock’) were old appellations. With regard to the name Patala he suggests that “it may have been derived from Patalam, the trumpet flower’’ (Bignonia syaveolens), in allusion to the trumpet shape of the province included between the eastern and western branches of the mouth of the Indus, as the two branches as they approach the sea curve outward like the mouth of a trumpet.” Ritter, however, says: -- "Patala is the designation bestowed by the Brahmans on all the provinces in the west towards sunset, in antithesis to Prasiaka (the eastern realm) in Ganges-land: for Patala is the mythological name in Sanskrit of the under-world, and consequently of the land of the west.” Arrian’s estimate of the magnitude of the Delta is somewhat excessive. The length of its base, from the Pitti to the Kori mouth, was less than 1000 stadia, while that of the Egyptian Delta was 1300.

CHAP. III. 1300 stadia.—The Olympic stadium, which was in general use throughout Greece, contained 600 Greek feet = 625 Roman feet, or 606-3/4 English feet. The Roman mile contained eight stadia, being about half a stadium less than an English mile. Not a few of the measurements given by Arrian are excessive, and it has therefore been conjectured that he may have used some standard different from the Olympic,—which, however, is hardly probable. With regard to the dimensions of India as stated in this chapter, General Cunningham observes that their close agreement with the actual size of the country is very remarkable, and shows that the Indians, even at that early date in their history, had a very accurate knowledge of the form and extent of their native land.

Schoeni.—The schoenus was ==2 Persian parasangs = 60 stadia, but was generally taken at half that length.

Chip. IV. Tributaries of the Ganges.—Seventeen are here enumerated, the Jamna being omitted, which, however, is afterwards mentioned (chap, viii.) as the Jobares. Pliny calls it the Jomanes, and Ptolemy the Diamounas. In Sanskrit it is the Jamuna (sister of Yama).

Kainas.—Some would identify this with the Kan or Kane, a tributary of the Jamna. Kan is, however, in Sanskrit Sena, and of this Kainas cannot be the Greek representative.

Erannoboas.—As Arrian informs us (chap. x.) that Palimbothra (Pataliputra, Patna) was situated at the confluence of this river with the Ganges, it must be identified with the river Son, which formerly joined the Ganges a little above Patna, where traces of its old channel are still discernible. The word no doubt represents the Sanskrit Hiranyavaha ('carrying gold’) or Hiranyabahu ('having golden arms'), which are both poetical names of the Son. It is said to be still called Hiranyavaha by the people on its banks. Megasthenes, however, and Arrian, both make the Erannoboas and the Son to be distinct rivers, and hence some would identify the former with the Gandak (Sanskrit Gandaki), which, according to Lassen, was called by the Buddhists Hiranyavati, or 'the golden.’ It is, however, too small a stream to suit the description of the Erannoboas, that it was the largest river in India after the Ganges and Indus. The Son may perhaps in the time of Megasthenes have joined the Ganges by two channels, which he may have mistaken for separate rivers.

Kosoanos.—Cosoagus is the form of the name in Pliny, and hence it has been taken to be the representative of the Sanskrit Kaushiki, the river now called the Kosi. Schwanbeck, however, thinks it represents the Sanskrit Kosavaha (= 'treasure-bearing’), and that it is therefore an epithet of the Son, like Hiranyavaha, which has the same meaning. It seems somewhat to favour this view that Arrian in his enumeration places the Kosoanos between the Erannoboas and the Son.

Sonos.—The Son, which now joins the Ganges ten miles above Dinapur. The word is considered to he a contraction of the Sanskrit Suvarna (Suvanna), 'golden,’ and may have been given as a name to the river either because its sands were yellow, or because they contained gold dust.

Sittokatis and Solomatis.—It has not been ascertained what rivers were denoted by these names. General Cunningham in one of his maps gives the Solomatis as a name of the Saranju or Sarju, a tributary of the Ghagra, while Benfey would identify it with the famous Sarasvati or Sarsuti, which, according to the legends, after disappearing underground, joined the Ganges at Allahabad.

Kondochates.—Now the Bandak,—in Sanskrit, Gandaki or Gandakavati ([x]), — because of its abounding in a kind of alligator having a horn-like projection on its nose.

Sambos.—Probably the Sarabos of Ptolemy. It may be the Sambal, a tributary of the Jamna.

Magon.—According to Mannert the Ramganga.

Agoranis.—According to Rennel the Ghagra -- a word derived from the Sanskrit Gharghara ('of gurgling sound’).

Omalis has not been identified, but Schwanbeck remarks that the word closely agrees with the Sanskrit Vimala ('stainless’), a common epithet of rivers.

Kommenases.—Rennel and Lassen identify this with the Karmanasa (bonorum operum destructriae), a small river which joins the Ganges above Baxar. According to a Hindu legend, whoever touches the water of this river loses all the merit of his good works, this being transferred to the nymph of the stream.

Kakouthis. -- Mannert takes this to be the Gumti.

Andomatis. -- Thought by Lassen to be connected with the Sanskrit Andhamati (tenebricosus) which he would identify, therefore, with the Tamasa, the two names being identical in meaning.

Madyandini may represent, Lassen thinks, the Sanskrit Madhyandina (meridionalis).

Amystis has not been identified, nor Katadupa, the city which it passes. The latter part of this word, dupa, may stand, Schwanbeck suggests, for the Sanskrit dvipa, 'an island.’

Oxymagis.—The Pazalae or Passalae, called in Sanskrit Pankala, inhabited the Doab, —through which, or the region adjacent to it, flowed the Ikshumati (‘abounding in sugar-cane’). Oxymagis very probably represented this name.

Errenysis closely corresponds to Varanasi, the name of Banaras in Sanskrit,—so called from the rivers Varana and Asi, which join the Ganges in its neighbourhood. The Mathae may be the people of Magadha. V. de Saint-Martin would fix their position in the country between the lower part of the Gumti and the Ganges, adding that “the Journal of Hiouen Thsang places their capital, Matipura, at a little distance to the east of the upper Ganges near Gangadvara, now Hardwar.”

Tributaries of the Indus: —Hydraotes.— Other forms are Rhouadis and Hyarotis. It is now called the Ravi, the name being a contraction of the Sanskrit Iravati, which means ‘abounding in water,’ or ‘ the daughter of Iravat,’ the elephant of Indra, who is said to have generated the river by striking his tusk against the rock whence it issues. His name has reference to his ‘ocean’ origin.

The name of the Kambistholae does not occur elsewhere. Schwanbeck conjectures that it may represent the Sanskrit Kapisthola, 'ape-land,’ the letter m being inserted, as in ' Palimbothra.’ Arrian errs in making the Hyphasis a tributary of the Hydraotes, for it falls into the Akesines below its junction with that river.

Hyphasis (other forms are Bibasis, Hypasis, and Hypanis.) -- In Sanskrit the Vipasa, and now the Byasa or Bias. It lost its name on being joined by the Satadru, 'the hundred- channelled,’ the Zaradros of Ptolemy, now the Satlej. The Astrobae are not mentioned by any writer except Arrian.

Saranges.—According to Schwanbeck, this word represents the Sanskrit Saranga, 'six-limbed.’ It is not known what river it designated. The Kekians, through whose country it flowed, were called in Sanskrit, according to Lassen, Sekaya.

Neudros is not known. The Attakeni are likewise unknown, unless their name is another form of Assakeni.

Hydaspes.—Bidaspes is the form in Ptolemy. In Sanskrit Vitasta, now the Behutor Jhelam; called also by the inhabitants on its banks the Bedusta, ‘widely spread.’ It is the “fabulosus Hydaspes” of Horace, and the "Medus Hydaspes” of Virgil. It formed the western boundary of the dominions of Porus.

Oxydrakai.—This name represents, according to Lassen, the Sanskrit Kshudraka. It is variously written,—Sydrakae, Syrakusae (probably a corrupt reading for Sudrakae), Sabagrae, and Sygambri, According to some accounts, this was the people among whom Alexander was severely wounded when his life was saved by Ptolemy, who in consequence received the name of Sotor. Arrian, however, refers this incident to the country of the Malli.

Akesines.—Now the Chenab: in Sanskrit Asikni, ‘dark-coloured,’—called afterwards Chandrabhaga. “This would have been hellenized into Sandrophagos,—a word so like to Androphagos or Alexandrophagos that the followers of Alexander changed the name to avoid the evil omen,—the more so, perhaps, on account of the disaster which befell the Macedonian fleet at the turbulent junction of the river with the Hydaspes.”—Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography.

Malli.—They occupied the country between the Akesines and the Hydraotes or Iravati. The name represents the Sanskrit Malava, Multan being its modern representative.

Toutapos. Probably the lower part of the Satadru or Satlej.

Parenos.—Probably the modern Burindu.

Saparnos.—-Probably the Abbasin.

Soanus represents the Sanskrit Suvana, 'the sun,’ or ‘fire’—now the Svan.

The Abissareans.—The name may represent the Sanskrit Abisara. [Lassen, Ind. Alt. II. 163.] A king called Abisares is mentioned by Arrian in his Anabasis (iv. 7). It may be here remarked that the names of the Indian kings, as given by the Greek writers, were in general the names slightly modified of the people over whom they ruled.

Taurunum.—The modern Semlin.

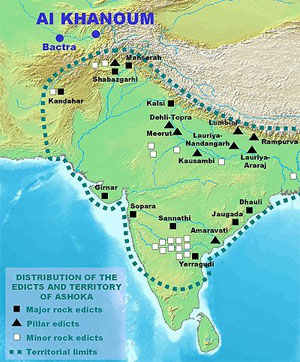

Chap. V. Megasthenes.—The date of his mission to India is uncertain. Clinton assigns it to the year 303 B.C., since about that time an alliance was formed between Seleucus and Sandrakottus (Chandragupta). It is also a disputed point whether he was sent on more than one embassy, as the words of Arrian (Anab. V. 6.), [x], may mean either that he went on several missions to Sandrakottus, or merely that he had frequent interviews with him. From Arrian we further learn regarding Megasthenes that he lived with Tyburtius the satrap of Arachosia, who obtained the satrapies of Arachosia and Gedrosia 323 B.C. Sandrakottus died about B.C. 288.

Sesostris has been identified with Ramses, the third king of the nineteenth dynasty as given in the History of Manetho.

Idanthyrsos.—Strabo mentions an irruption of Skythians into Asia under a leader of this name, and Herodotos mentions an invasion which was led by Madyas. As Idanthyrsos may have been a common appellative of all the Skythian kings, it may be one and the same invasion to which both writers refer. It was made when Kyaxares reigned in Media and Psammitichus in Egypt.

Mount Meros. -- Mount Meru, the Olympus of Indian mythology. As a geographical term it designated the highland of Tartary north of the Himalaya. Siva was the Indian deity whom the Greeks identified with Bacchus, as they identified Krishna with Hercules.

The rock Aornos.—The much-vexed question of the position of this celebrated rock has been settled by General Cunningham, who has identified it with the ruined fortress of Ranigat, situated immediately above the small village of Nogram, which lies about sixteen miles north by west from Ohind, which he takes to be the Embolima of the ancients. “Ranigat,” he says, or the Queen’s rock, is a large upright block on the north edge of the fort, on which Raja Vara’s rani is said to have seated herself daily. The fort itself is attributed to Raja Vara, and some ruins at the foot of the hill are called Raja Vara’s stables . . . I think, therefore, that the hill-fort of Aornos most probably derived its name from Raja Vara, and that the mined fortress of Ranigat has a better claim to be identified with the Aomos of Alexander than either the Mahaban hill of General Abbott, or the castle of Raja Hodi proposed by General Court and Mr. Loewenthal.”

The Cave of Promethess.—Probably one of the vast caves in the neighbourhood of Bamian.

Sibae.—A fierce mountain tribe called Siapul or Siapush still exists, inhabiting the Hindu Kush, who use to this day the club, and wear the skins of goats for clothing. According to Curtius, however, the Sivae, whom he calls Sobii, occupied the country between the Hydaspes and Akesines. They may have derived their name from the god Siva. In the neighbourhood of Hardwar there is a district called Siba.

Chap. VI. The Silas.-—Other forms are Sillas and Silias. Demokritos and Aristotle doubted the story told of this river, but Lassen states that mention is made in Indian writings of a river in the northern part of India whose waters have the power of turning everything cast into them into stone, the Sanskrit word for which is sila.

Tala.—The fan-palm, the Borassus flabelli-formis of botany.

Chap. VIII.—Spatembas and his successors were the kings of Magadha, which in these early times was the most powerful kingdom in India: Palimbothra was its capital.

Boudyas.—This is no doubt, the name of Buddha hellenized.

Souraseni.—This name represents the Sanskrit Surasena, which designated the country about Methora, now Mathura, famous as the birthplace and scene of the adventures of Krishna, whom the Greeks identified with Hercules. Methora is mentioned by Pliny, who says, Amnis Jomanes in Gangem per Palibothros decurrit inter oppida Methora et Charisobora." Chrysobora and Kyrisobora are various readings for Charisobora, which is doubtless another form of Arrian’s Kleisobora. This word may represent, perhaps, the Sanskrit Krishnaputra. Jobares is the Jamuna. The Palibothri, in the passage quoted, must be taken to denote the subjects of the realm of which Palibothra was the capital, and not merely the inhabitants of that city, as some have supposed.

Pandaea.—Pliny mentions a tribe called Pandae, who alone of the Indians were in the habit of having female sovereigns. Th, name undoubtedly points to the famous dynasty of the Pandavas, which extended so widely over India. In the south there was a district called Pandavi regio, while another of the same name is placed by Ptolemy in the Panjab on the Bidaspes (Bias).

Margarita.—This word cannot be traced to Sanskrit. Murvarid is, said to be a name in Persian for the pearl.

Palimbothra.—The Sanskrit Pataliputra, now Patna, sometimes still called Pataliputra. The name means ‘the son of the Patali, or trumpet flower (Bignonia suaveolens).' Its earliest name was Kausambi, so called as having been founded by Kusa, the father of the celebrated sage Visvamitra. It was subsequently called also Pushpapura or Kusumapura, 'the city of flowers.’ Megasthenes and Eratosthenes give its distance from the mouth of the Ganges at 6000 stadia.

The Prasians.—“Strabo and Pliny,” says General Cunningham, agree with Arrian in calling the people of Palibothra by the name of Prasii which modern writers have unanimously referred to the Sanskrit Prachya or 'eastern.’ But it seems to me that Prasii is only the Greek form of Palasa or Parasa, which is an actual and well-known name of Magadha, of which Palibothra was the capital. It obtained this name from the Palasa, or Butea frondosa, which still grows as luxuriantly in the province as in the time of Hiwen Thsang. The common form of the name is Paras, or when quickly pronounced Pras, which I take to be the true original of the Greek Prasii. This derivation is supported by the spelling of the name given by Curtius, who calls the people Pharrasii, which is an almost exact transcript of the Indian name Parasiya. The Praxiakos of AElian is only the derivative from Palasaka.

Chap. XXI. --According to Vincent, the expedition started on the 23rd of October 327 B.C.; the text indicates the year 326, but the correct date is 325. The lacuna marked by the asterisks has been supplied by inserting the name of the Macedonian month Dius. The Ephesians adopted the names of the months used by the Macedonians, and so began their year with the month Dius, the first day of which corresponds to the 24th of September. The harbour from which the expedition sailed was distant from the sea 150 stadia. It was probably in the island called by Arrian, in the Anabasis (vi. 19) Killuta, in the western arm of the Indus,—that now called the Pitti mouth.

Kaumara may perhaps be represented by the modern Khau, the name of one of the mouths of the Indus in the part through which the expedition passed.

Koreestis. —This name does not occur elsewhere. Regarding the sunken reef encountered by the fleet after leaving this place, Sir Alexander Burnes says: "Near the mouth of the river we passed a rock stretching across the stream, which is particularly mentioned by Nearchus, who calls it a dangerous rock, and is the more remarkable since there is not even a stone below Tatta, in any other part of the Indus." The rock, he adds, is at a distance of six miles up the Pitti. ‘‘It is vain," says Captain Wood in the narrative of his Journey to the Source of the Oxus, in the delta of such a river (as the Indus), to identify existing localities with descriptions handed down to us by the historians of Alexander the Great .... (but) Burnes has, I think, shown that the mouth by which the Grecian fleet left the Indus was the modern Piti. The ‘dangerous rock’ of Nearchus completely identifies the spot, and as it is still in existence, without any other within a circle of many miles, we can wish for no stronger evidence.” With regard to the canal dug through this rock, Burnes remarks: "The Greek admiral only availed himself of the experience of the people, for it is yet customary among the natives of Sind to dig shallow canals and leave the tides or river to deepen them; and a distance of five stadia, or half a mile, would call for not great labour. It is not to be that sandbanks will continue unaltered for centuries, but I may observe that there was a large bank contiguous to the island, between it and which a passage like that of Nearchus might have been dug with the greatest advantage.” The same author thus describes the mouth of the Piti: -- "Beginning from the westward we have the Pitti month, an embouchure of the Buggaur, that falls into what may be called the Bay of Karachi. It has no bar, but a large sandbank together with an island outside prevent a direct passage into it from the sea, and narrow the chamnel to about half a mile at its mouth.”

Krokala.—"Karachi,” says General Cunningham, must have been on the eastern frontier of the Arabitae,—a deduction which is admitted by the common consent of all inquirers, who have agreed in identifying the Kolaka of Ptolemy, and the sandy island of Krokola where Nearchus tarried with his fleet for one day, with a small island in the bay of Karachi. Krokala is further described as lying off the mainland of the Arabii. It was 150 stadia, or 17-1/4 miles, from the western mouth of the Indus,—which agrees exactly with the relative positions of Karachi and the mouth of the Ghara river, if, as we may fairly assume, the present coast-line has advanced five or six miles during the twenty-one centuries that have elapsed since the death of Alexander. The identification is confirmed by the fact that the district in which Karachi is situated is called Karkalla to this day. On leaving Krokala, Nearchus had Mount Eiros (Manora) on his right hand, and a low flat island on his left, -- which is a very accurate description of the entrance to Karachi harbour.”

Arabii.— The name is variously written, -- Arabitae, Arbii, Arabies, Arbies, Aribes, Arbiti. The name of their river has also several forms,— Arabis, Arabius, Artabis, Artabius. It is now called the Purali, the river which flows through the present district of Las into the bay of Sonmiyani.

Oritae. The name in Curtius is Horitae. General Cunningham identifies them with the people on the Aghor river, whom he says the Greeks would have named Agoritae or Aoritae, by the suppression of the guttural, of which a trace still remains in the initial aspirate of 'Horitae.' Some would connect the name with Haur, a town which lay on the route to Firabaz, in Mekran.

Bibakta.—The form of the name is Bibaga in Pliny, who gives its distance from Krokala at twelve miles. Vincent would refer it to the island now called Chilney,—which, however, is too distant.

Sangada. This name D’Anville thought survived in that of a race of noted pirates who infested the stores of the gulf of Kachh, called the Sangadians or Sangarians.

Chap. XXII. —The coast from Karachi to the Purali has undergone considerable changes, so that the position of the places mentioned in this chapter cannot be precisely determined. ‘'From Cape Monze to Sonmiyani,” says Blair, ‘the coast bears evident marks of having suffered considerable alterations from the encroachments of the sea. We found trees which had been washed down, and which afforded us a supply of fuel. In some parts I saw imperfect creeks in a parallel direction with the coast. These might probably be the vestiges of that narrow channel through which the Greek galleys passed.”

Domae.—This island is not known, but it probably lay near the rocky headland of Irus, now called Manora, which protects the port of Karachi from the sea and bad weather.

Morontobari.—‘*The name of Morontobara,” says General Cunningham, “I would identify with Muari, which is now applied to the headland of Ras Muari or Cape Monze, the last point of the Pab range of motmtains. Bara, or Bari means a roadstead or haven; and Moranta is evidently connected with the Persian Mard, a man, of which the feminine is still preserved in Kasmiri, as Mahrin, a woman. From the distances given by Arrian, I am inclined to fix it at the month of the Bahar rivulet, a small stream which falls into the sea about midway between Cape Monze and Sonmiyani." Women's Haven is mentioned by Ptolemy and Ammianus Marcellinus. There is in the neighbourhood a mountain now called Mor, which may be a remnant of the name Morontobari. The channel through which the fleet passed after leaving this place no longer exists, and the island has of course disappeared.

Haven at the mouth of the Arabis. —The Purali discharges its waters into the bay of Sonmiyani, as has been already mentioned. "Sonmiyani,” says Kempthorne, "is a small town or fishing village situated at the mouth of a creek which runs up some distance inland. It is governed by a sheikh, and the inhabitants appear to be very poor, chiefly subsisting on dried fish and rice. A very extensive bar or sandbank runs across the month of this inlet, and none but vessels of small burden can get over it even at high water, but inside the water is deep.” The inhabitants of the present day are as badly off for water as their predecessors of old. Everything,” says one who visited the place, "is scarce, even water, which is procured by digging a hole five or six feet deep, and as many in diameter, in a place which was formerly a swamp; and if the water oozes, which sometimes it does not, it serves them that day, and perhaps the next, when it turns quite brackish, owing to the nitrous quality of the earth.”

CHAP. XXIII. Pagali.—Another form is Pegadae, met with in Philostratus. who wrote a work on India.

Kabana.—To judge from the distances given, this place should be near the stream now called Agbor, on which is situated Harkana. It is probably the Kaeamba of Ptolemy.

Kokala must have been situated near the headland now called Ras Katchari.

CHAP. XXIV. Tomeros.—From the distances given, this must be identified with the Maklow or Hingal river; some would, however, make it the Bhusal. The form of the name in Pliny is Tomberus, and in Mela—Tubero. These authors mention another river in connection with the Tomerus, -- the Arosapes or Arusaces.

XXV. Malana.—Its modern representative is doubtless Ras Malin or Malen.

The Length of the Voyage, 1600 stadia. -- In reality the length is only between 1000 and 1100 stadia, even when allowance is made for the winding of the coast. Probably the difficulty of the navigation made the distances appear much greater than the reality.

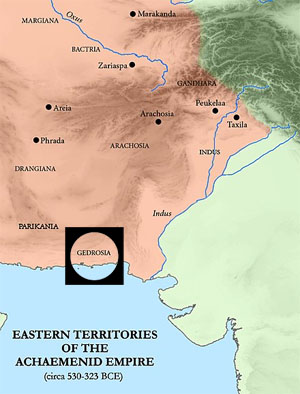

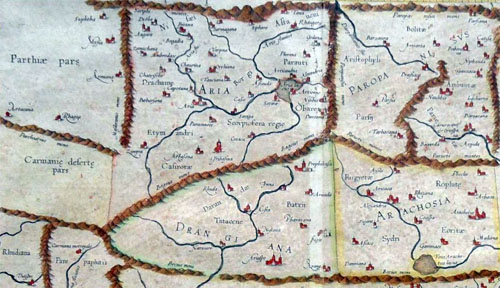

Chap. XXVI. The Gedrosians.—Their country, which corresponds generally to Mekran, was called Gedrosia, Kedrosia, Gadrosia, or Gadrusia. The people were an Arianian race akin to the Arachosii, Arii, and Drangiani.

Bagisara.— ‘‘This place,” says Kempthorne, ‘‘is now known by the name of Arabah or Hormarah Bay, and is deep and commodious with good anchorage, sheltered from all winds but those from the southward and eastward. The point which forms this bay is very high and precipitous, and runs out some distance into the sea.... Rather a large fishing village is situated on a low sandy isthmus about one mile across, which divides the bay from another. .... The only articles of provision we could obtain from the inhabitants were a few fowls, some dried fish, and goats. They grow no kind of vegetable or corn, a few water-melons being the only thing these desolate regions bring forth. Sandy deserts extend into the interior as far as the eye can reach, and at the back of these rise high mountains.”

The Rhapua of Ptolemy corresponds to the Bagisara or Pasira of Arrian, and evidently survives in the present name of the bay and the headland of Araba.

Kolta. —A place unknown. It was situated on the other side of the isthmus which connects Ras Araba with the mainland.

Kalybi.—A different form is Kalami or Kalamae. Situated on the river now called Kalami, or Kumra, or Kurmut.

Karnine (other forms—Karbine, Karmina). The coast was probably called Karmin, if Karmis is represented in Kurmat. The island lying twelve miles off the month of the Kalami is now called Astola or Sanga-dip, which Kempthorne thus describes: -- "Ashtola is a small desolate island about four or five miles in circumference, situated twelve miles from the coast of Mekran. Its cliffs rise rather abruptly from the sea to the height of about 300 feet, and it is inaccessible except in one place, which is a sandy beach about one mile in extent on the northern side. Great quantities of turtle frequent this island for the purpose of depositing their eggs. Nearchus anchored off it and called it Karnine. He says also that he received hospitable entertainment from its inhabitants, their presents being cattle and fish; but not a vestige of any habitation now remains. The Arabs come to this island and kill immense numbers of these turtles,—not for the purpose of food, but they traffic with the shell to China, where it is made into a kind of paste and then into combs, ornaments, &c., in imitation of tortoise-shell. The carcasses caused a stench almost unbearable. The only land animals we could see on the island were rats, and they were swarming. They feed chiefly on the dead turtle. The island was once famous as the rendezvous of the Jowassimee pirates.” Vincent quotes Blair to this effect regarding the island:—“We were warned by the natives at Passara that it would be dangerous to approach the island of Asthola, as it was enchanted, and that a ship had been turned into a rock. The superstitious story did not deter us; we visited the island, found plenty of excellent turtle, and saw the rock alluded to, which at a distance had the appearance of a ship under sail. The story was probably told to prevent our disturbing the turtle. It has, however, some affinity to the tale of Nearchus’s transport.” As the enchanted island mentioned afterwards (chap, xxxi.), under the name of Nosala, was 100 stadia distant from the coast, it was probably the same as Karnine.

Kissa.—Another form is Kysa.

Mosarna.—The place according to Ptolemy is 900 stadia distant from the Kalami river, but according to Marcianus 1300 stadia. It must have been situated in the neighbourhood of Cape Passence. The distances here are so greatly exaggerated that the text is suspected to be corrupt or disturbed. From Mosarna to Kophas the distance is represented as 1750 stadia, and yet the distance from Cape Passence to Ras Koppa (the Kephas of the text) is barely 500 stadia.

Chap. XXVII. Balomon.— The name does not occur elsewhere.

Barna.—This place is called in Ptolemy and Marcianus Badera or Bodera, and may have been situated near the cape now called Chemaul Bunder.

Dendrobosa—In Ptolemy a place is mentioned called Derenoibila, which may be the same as this. The old name perhaps survives in the modern Daram or Duram, the name of a highland on part of the coast between Cape Passence and Guadel.

Kyiza.—According to Ptolemy and Marcianus this place lay 400 stadia to the west of the promontory of Alambator (now Ras Guadel). Some trace of the word may be recognized in Ras Ghunse, which now designates a point of land situated about those parts.

The little town attacked by Nearchus.—The promontory in its neighbourhood called Bagia is mentioned by Ptolemy and Marcianus, the latter of whom gives its distance from Kyiza at 260 stadia, which is but half the distance as given by Arrian. To the west of this was the river Kaudryaces or Hydriaces, the modern Baghwar Dasti or Muhani river, which falls into the Bay of Gwattar.

Chap. XXIX. Talmena.—A name not found elsewhere. To judge by the distance assigned, it must be placed on what is now called Chaubar Bay, on the shores of which are three towns, one being called Tiz,—perhaps the modern representative of Tisa, a place in those parts mentioned by Ptolemy, and which may have been the Talmena of Arrian.

Kanasis.—The name is not found elsewhere. It must have been situated on a bay enclosed within the two headlands Ras Fuggem and Ras Godem.

Kanate probably stood on the site of the modern Kungoun, which is near Ras Kalat, and not far from the river Bunth.

Troes.—Erratum for Troi; another form is Tai.

Dagasira.—The place in Ptolemy is called Agris polis,—in Marcianus -- Agrisa. The modern name is Girishk.

10,000 stadia.—The length of the coast line of the Ichthyophagi is given by Strabo at 7300 stadia only. “This description of the natives, with that of their mode of living and the country they inhabit, is strictly correct even to the present day.” (Kempthome.)

Chap. XXX.— In illustration of the statements in the text regarding whales may be compared Strabo, XV. ii. 12, 13.

Chap. XXXII.— Karmania extended from Cape Jask to Ras Nabend, and comprehended the districts now called Moghostan, Kirman, and Laristan, Its metropolis, according to Ptolemy, was Karmana, now Kirman, which gives its name to the whole province. The first port in Karmania reached by the expedition was in the neighbourhood of Cape Jask, where the coast is described as being very rocky, and dangerous to mariners on account of shoals and rocks under water. Kempthorne says: "The cliffs along this part of the coast are very high, and in many places almost perpendicular. Some have a singular appearance, one near Jask being exactly of the shape of a quoin or wedge; and another is a very remarkable peak, being formed by three stones, as if placed by human hands, one on the top of the other. It is very high, and has the resemblance of a chimney.”

Bados.—Erratum for Badis. It is near Jask, beyond which was the promontory now called Raj Keragi or Cape Bombarak, which marks the entrance to the Straits of Ormus.

Maketa.——How Ras Mussendum, in Oman -- about fifty miles, according to Pliny, from the opposite coast of Karmania. It figures in Lalla Rookh as “Selama's sainted cape.”

Chap. XXXIII. Neoptana.—This place is not mentioned elsewhere, but must have been situated somewhere in the neighbourhood of the village of Karun.

The Anamis (other forms—Ananis, Andanis, Andamis).—It is now called the Nurab.

Harmozia (other forms—Hormazia, Armizia regio). -- The name was transferred from the mainland to the island now called Ormus when the inhabitants fled thither to escape from the Moghals. It is called by Arrian Organa (chap. xxxvii.). The Arabians called it Djerun, a name which it continued to bear up to the 12th century. Pliny mentions an island called Oguris, of which perhaps Djerun is a corruption. He ascribes to it the honour of having been the birthplace of Erythres. The description, however, which, he gives of it is more applicable to the island called by Arrian (chap, xxxvii.) Oarakta (now Kishm) than to Ormus. Arrian’s description of Harmozia is still applicable to the region adjacent to the Minab. “It is termed,” says Kempthorne, “ the Paradise of Persia. It is certainly most beautifully fertile, and abounds in orange groves, orchards containing apples, pears, peaches, and apricots, with vineyards producing a delicious grape, from which was made at one time a wine called Amber rosolia, generally considered the white wine of Kishma; but no wine is made here now.” The old name of Kishma—Oarakta—is preserved in one of its modern names, Vrokt or Brokt.

Chap. XXXVII. The island sacred to Poseidon. —The island now called Angar, or Hanjam, to the south of Kishm.It is described as being nearly destitute of vegetation and uninhabited. Its hills, of volcanic origin, rise to a height of 300 feet. The other island, distant from the mainland about 300 stadia, is now called the Great Tombo, near which is a smaller island called Little Tombo. They are low, flat, and uninhabited. They are 25 miles distant from the western extremity of Kishm.

Pylora.—How Polior.

Sisidone (other forms—Prosidodone, pro-Sidodone, pros Sidone, pros Dodone). Kempthorne thought this was the small fishing village now called Mogos, situated in a bay of the same name. The name may perhaps be preserved in the name of a village in the same neighbourhood, called Dnan Tarsia—now Rasel Djard —described as high and rugged, and of a reddish colour.

Kataka.—Now the island called Kaes or Kenn. Its character has altered, as it is now covered with dwarf trees, and grows wheat and tobacco. It supplies ships with refreshment, chiefly goats and sheep and a few vegetables.

Chap. XXXVIII.—The boundary between Karmania and Persis was formed by a range of mountains opposite the island of Kataka. Ptolemy, however, makes Karmania extend much further, to the river Bagradas, now called the Naban or Nabend.

Kaekander (other forms—Kekander, Kikander, Kaskandrus, Karkundrus, Karskandrus, Sasaekander). This island, which is now called Inderabia or Andaravia, is about four or five miles from the mainland, having a small town on the north side, where is a safe and commodious harbour. The other island mentioned immediately after is probably that now called Busheab. It is, according to Kempthorne, a low, flat island about eleven miles from the mainland, containing a small town principally inhabited by Arabs, who live on fish and dates. The harbour has good anchorage even for large vessels.

Apostana.—Near a place now called Schevar. It is thought that the name may he traced in Dahr Asban, an adjacent mountain ridge of which Ochus was probably the southern extremity.

The bay with numerous villages on its shores is that on which Naban or Nabend is now situated. It is not far from the river called by Ptolemy the Bagradas. The place abounds with palm-trees, as of old.

Grogana.—How Konkan or Konaun. The bay lacks depth of water, still a stream falls into it—the Areon of the text. To the northwest of this place in the interior lay Pasargada, the ancient capital of Persia and the burial-place of Cyrus.

Sitakus.—The Sitiogagus of Pliny, who, states that from its mouth an ascent could be made to Pasargada in seven days; but this is manifestly an error. It is now represented by a stream called Sita-Khegian.

Chap. XXXIX. Hieratis.—The changes which have taken place along the coast have been so considerable that it is difficult to explain this part of the narrative consistently with the now existing state of things.

Mesambria.—The peninsula lies so low that at times of high tide it is all but submerged. The modern Abu-Shahr or Bushir is situated on it.

Taoke, on the river Granis.—Nearchus, it is probable, put into the mouth of the river now called the Kisht. A town exists in the neighbourhood called Gra or Gran, which may have received its name from the Granis. The | royal city (or rather palace) 200 stadia distant from this river is mentioned by Strabo, XV. 3, 3, as being situate on the coast.

Rogonis.—It is written Rhogomanis by Ammianus Marcellinus, who mentions it as one of the four largest rivers in Persia, the other three being the Vatrachitis; Brisoana, and Bagrada.

Brizana.—Its position cannot be fixed with certainty.

Oroatis.—Another form is Arosis. It answers to the Zarotis of Pliny, who states that the navigation at its mouth was difficult, except to those well acquainted with it. It formed the boundary between Persis and Susiana. The form Oroatis corresponds to the Zend word aurwat, ‘swift.’ It is now called the Tab.

Chap. XL. Uxii.—They are mentioned by the author in the Anabasis, bk. vii. 15, 3.

Persis has three different climates.—On this point compare Strabo, bk. xv. 3, 1.

Ambassadors from the Euxine Sea.-- It has been conjectured that the text here is imperfect; Schmieder opines that the story about the ambassadors is a fiction.

Chap. XLI. Kataderbis.—This is the bay which receives the streams of the Mensureh and Dorak; at its entrance lie two islands, Bunah and Deri, one of which is the Margastana of Arrian.

Diridotis.—This is called by other writers Teredon, and is said to have been founded by Nabuchodonosor. Mannert places it on the island now called Bubian; Colonel Chesney, however, fixes its position at Jebel Sanam, a gigantic mound near the Pallacopas branch of the Euphrates, considerably to the north of the embouchure of the present Euphrates. Nearchus had evidently passed unawares the main stream formed by the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris (called by some the Pasitigris), and sailed too far westward. Hence he had to retrace his course, as mentioned in the next chapter.

Chap. XLII. Pasitigris.—The Eulaeus, now called the Karun, one arm of which united with the Tigris, while the other fell into the sea by an independent mouth. It is the Ulai of the prophet Daniel. Pas is said to be an old Persian word meaning small. By some writers the name Pasitigris was applied to the united stream of the Tigris and Euphrates, now called the Shat-el-Arab.

The distance from where they entered the lake to where they entered the river was 600 stadia.— A reconsideration of this passage has led me to adopt the view of those who place Aginis on the Tigris, and not on the Pasitigris. I would therefore now translate thus:—“The ascent from the southern (end of the) lake to where the river Tigris falls into it is 600 stadia." The fleet, therefore, could not have visited Aginis. The courses of the rivers and the conformation of the country have all undergone great changes, and hence the identification of localities is a matter of difficulty and uncertainty. The distance from Aginis to Susa appears to me to be much under-estimated.

The following extract from Strabo will illustrate this part of the narrative:—

Polycletus says that the Choaspes, and the Eulaeus, and the Tigris also enter a lake, and thence discharge themselves into the sea; that on the side of the lake is a mart, as the rivers do not receive the merchandize from the sea, nor convey it down to the sea, on account of dams in the river, purposely constructed; and that the goods are transported by land, a distance of 800 stadia, to Susis: according to others, the rivers which flow through Susis discharge themselves by the intermediate canals of the Euphrates into the single stream of the Tigris, which on this account has at its mouth the name of Pasitigris. According to Nearchus, the sea-coast of Susis is swampy and terminates at the river Euphrates; at its mouth is a village which receives the merchandize from Arabia, for the coast of Arabia approaches close to the mouths of the Euphrates and the Pasitigris; the whole intermediate space is occupied by a lake which receives the Tigris. On sailing up the Pasitigris 150 stadia is a bridge of rafts leading to Susa from Persia, and is distant from Susa 60 (600?) stadia; the Pasitigris is distant from the Oroatis about 2000 stadia; the ascent through the lake to the mouth of the Tigris is 600 stadia; near the mouth stands the Susian village Aginis, distant from Susa 500 stadia; the journey by water from the mouth of the Euphrates up to Babylon, through a well-inhabited tract of country, is a distance of more than 3000 stadia."—Book xv. 3, Bohn’s translation.

The Bridge.—This according to Ritter and Rawlinson, was formed at a point near the modern village of Ahwaz. Arrowsmith places Aginis at Ahwaz.

Chap. XLIII.—The 3rd part of the Indica, the purport of which is to prove that the southern parts of the world are uninhabitable, begins, with this chapter.

The troops sent by Ptolemy. —It is not known when or wherefore Ptolemy sent troops on this expedition.

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Kanishka

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/3/21

Kanishka I

Kushan emperor

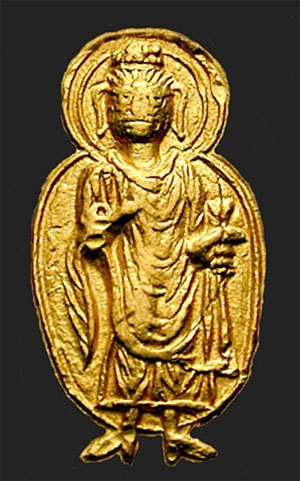

Gold coin of Kanishka. Greco-Bactrian legend: [x] Shaonanoshao Kanishki Koshano "King of Kings, Kanishka the Kushan". British Museum.

Reign: 2nd century (120-144)

Predecessor: Vima Kadphises

Successor: Huvishka

Born: c. 70, Kapisi

Died: 144 (aged 73-74)

Dynasty: Kushan dynasty

Religion: Buddhism

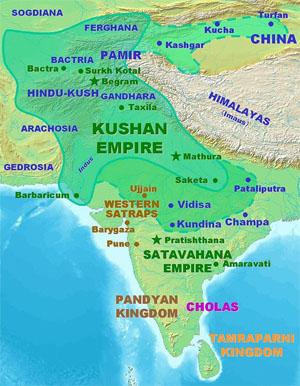

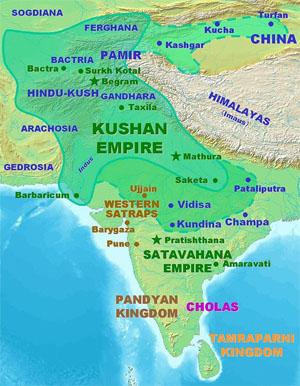

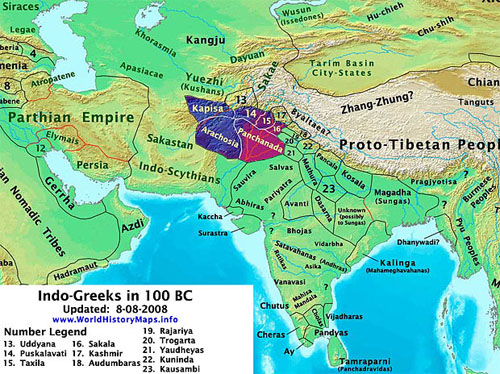

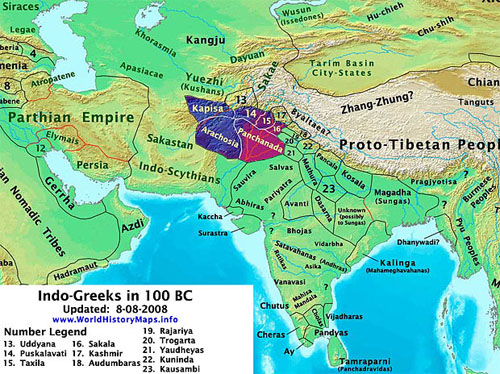

Kanishka I (Sanskrit: [x]; Greco-Bactrian: [x] Kanēške; Kharosthi: [x] Ka-ṇi-ṣka, Kaṇiṣka;[1] Brahmi: Kā-ṇi-ṣka), or Kanishka the Great, an emperor of the Kushan dynasty in the second century (c. 127–150 CE),[2] is famous for his military, political, and spiritual achievements. A descendant of Kujula Kadphises, founder of the Kushan empire, Kanishka came to rule an empire in Gandhara extending to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain. The main capital of his empire was located at Puruṣapura (Peshawar) in Gandhara, with another major capital at Kapisa. Coins of Kanishka were found in Tripuri (jabalpur madhya pradesh)

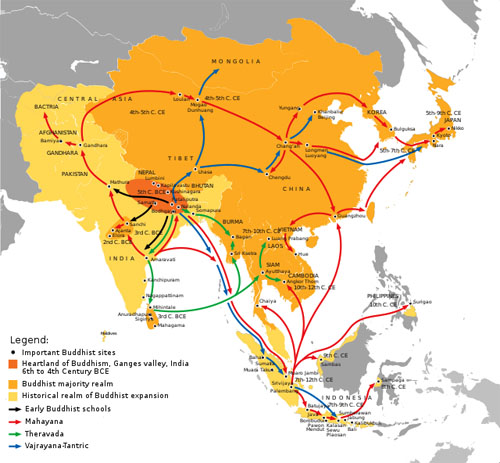

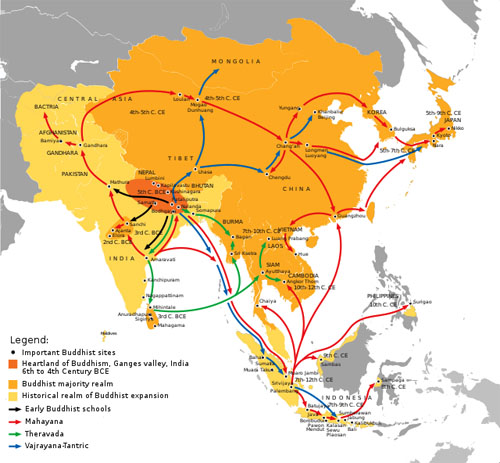

His conquests and patronage of Buddhism played an important role in the development of the Silk Road, and in the transmission of Mahayana Buddhism from Gandhara across the Karakoram range to China. Around 127 CE, he replaced Greek by Bactrian as the official language of administration in the empire.[3]

Earlier scholars believed that Kanishka ascended the Kushan throne in 78 CE, and that this date was used as the beginning of the Saka calendar era. However, historians no longer regard this date as that of Kanishka's accession. Falk estimates that Kanishka came to the throne in 127 CE.[4]

Genealogy

Mathura statue of Kanishka. The Kanishka statue in the Mathura Museum. There is a dedicatory inscription along the bottom of the coat.

The inscription is in middle Brahmi script:

Mahārāja Rājadhirāja Devaputra Kāṇiṣka

"The Great King, King of Kings, Son of God, Kanishka".[5]

Mathura art, Mathura Museum

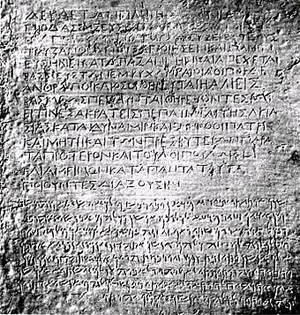

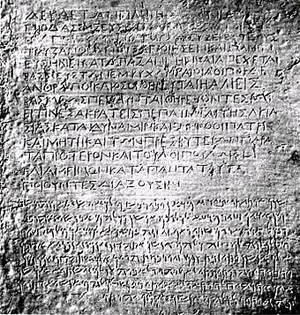

Kanishka was a Kushan of probable Yuezhi ethnicity.[6] His native language is unknown. The Rabatak inscription uses a Greek script, to write a language described as Arya (αρια) – most likely a form of Bactrian native to Ariana, which was an Eastern Iranian language of the Middle Iranian period.[7] However, this was likely adopted by the Kushans to facilitate communication with local subjects. It is not certain, what language the Kushan elite spoke among themselves.

Kanishka was the successor of Vima Kadphises, as demonstrated by an impressive genealogy of the Kushan kings, known as the Rabatak inscription.[8][9] The connection of Kanishka with other Kushan rulers is described in the Rabatak inscription as Kanishka makes the list of the kings who ruled up to his time: Kujula Kadphises as his great-grandfather, Vima Taktu as his grandfather, Vima Kadphises as his father, and himself Kanishka: "for King Kujula Kadphises (his) great grandfather, and for King Vima Taktu (his) grandfather, and for King Vima Kadphises (his) father, and *also for himself, King Kanishka".[10]

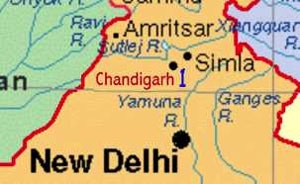

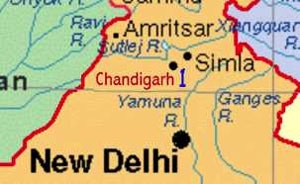

Conquests in South and Central Asia

Kanishka's empire was certainly vast. It extended from southern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, north of the Amu Darya (Oxus) in the north west to Northern India, as far as Mathura in the south east (the Rabatak inscription even claims he held Pataliputra and Sri Champa), and his territory also included Kashmir, where there was a town Kanishkapur (modern day Kanispora), named after him not far from the Baramula Pass and which still contains the base of a large stupa.

Knowledge of his hold over Central Asia is less well established. The Book of the Later Han, Hou Hanshu, states that general Ban Chao fought battles near Khotan with a Kushan army of 70,000 men led by an otherwise unknown Kushan viceroy named Xie (Chinese:[x]) in 90 AD. Ban Chao claimed to be victorious, forcing the Kushans to retreat by use of a scorched-earth policy. The territories of Kashgar, Khotan and Yarkand were Chinese dependencies in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang. Several coins of Kanishka have been found in the Tarim Basin.[11]

Controlling both the land (the Silk Road) and sea trade routes between South Asia and Rome seems to have been one of Kanishka's chief imperial goals.

Kushan territories (full line) and maximum extent of Kushan dominions under Kanishka (dotted line), according to the Rabatak inscription.[12]

Probable statue of Kanishka, Surkh Kotal, 2nd century CE. Kabul Museum.[13]

Bronze coin of Kanishka, found in Khotan, modern China.

Samatata coinage of king Vira Jadamarah, in imitation of the Kushan coinage of Kanishka I. Bengal, circa 2nd-3rd century CE.[14]

Kanishka's coins

Kanishka's coins portray images of Indian, Greek, Iranian and even Sumero-Elamite divinities, demonstrating the religious syncretism in his beliefs. Kanishka's coins from the beginning of his reign bear legends in Greek language and script and depict Greek divinities. Later coins bear legends in Bactrian, the Iranian language that the Kushans evidently spoke, and Greek divinities were replaced by corresponding Iranian ones. All of Kanishka's coins – even ones with a legend in the Bactrian language – were written in a modified Greek script that had one additional glyph ([x]) to represent /[x]/ (sh), as in the word 'Kushan' and 'Kanishka'.

On his coins, the king is typically depicted as a bearded man in a long coat and trousers gathered at the ankle, with flames emanating from his shoulders. He wears large rounded boots, and is armed with a long sword as well as a lance. He is frequently seen to be making a sacrifice on a small altar. The lower halfIranian and Indic of a lifesize limestone relief of Kanishka similarly attired, with a stiff embroidered surplice beneath his coat and spurs attached to his boots under the light gathered folds of his trousers, survived in the Kabul Museum until it was destroyed by the Taliban.[15]

Hellenistic phase

Gold coin of Kanishka I with Greek legend and Hellenistic divinity Helios. (c. 120 AD).

Obverse: Kanishka standing, clad in heavy Kushan coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding a standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar. Greek legend [x]"[coin] of Kanishka, king of kings".

Reverse: Standing Helios in Hellenistic style, forming a benediction gesture with the right hand. Legend in Greek script: [x] Helios. Kanishka monogram (tamgha) to the left.

A few coins at the beginning of his reign have a legend in the Greek language and script: [x], basileus basileon kaneshkou "[coin] of Kanishka, king of kings."

Greek deities, with Greek names are represented on these early coins:

• [x] (ēlios, Hēlios), [x] (ēphaēstos, Hephaistos), [x] (salēnē, Selene), [x] (anēmos, Anemos)

The inscriptions in Greek are full of spelling and syntactical errors.

Iranian / Indic phase

Following the transition to the Bactrian language on coins, Iranian and Indic divinities replace the Greek ones:

• [x] (ardoxsho, Ashi Vanghuhi)

• [x] (lrooaspo, Drvaspa)

• [x] (adsho, Atar)

• [x] (pharro, personified khwarenah)

• ΜΑΟ (mao, Mah)

• [x], (mithro, miiro, mioro, miuro, variants of Mithra)

• [x] (mozdaooano, "Mazda the victorious?")

• ΝΑΝΑ, ΝΑΝΑΙΑ, [x] (variants of pan-Asiatic Nana, Sogdian nny, in a Zoroastrian context Aredvi Sura Anahita)

• [x] (manaobago, Vohu Manah )

• [x] (oado, Vata)

• [x] (orlagno, Verethragna)

Only a few Buddhist divinities were used as well:

• [x] (boddo, Buddha),

• [x] (shakamano boddho, Shakyamuni Buddha)

• [x] (metrago boddo, the bodhisattava Maitreya)

Only a few Hindu divinities were used as well:

[x] (oesho, Shiva). A recent study indicate that oesho may be Avestan Vayu conflated with Shiva.[16][17]

Kanishka and Buddhism

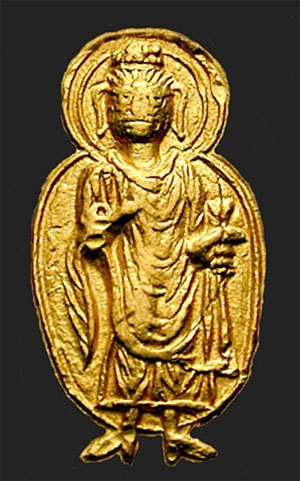

Gold coin of Kanishka I with a representation of the Buddha (c.120 AD).

Obv: Kanishka standing.., clad in heavy Kushan coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar. Kushan-language legend in Greek script (with the addition of the Kushan [x] "sh" letter): [x] ("Shaonanoshao Kanishki Koshano"): "King of Kings, Kanishka the Kushan".

Rev: Standing Buddha in Hellenistic style, forming the gesture of "no fear" (abhaya mudra) with his right hand, and holding a pleat of his robe in his left hand. Legend in Greek script: [x] "Boddo", for the Buddha. Kanishka monogram (tamgha) to the right.

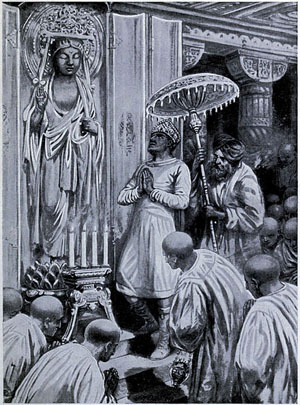

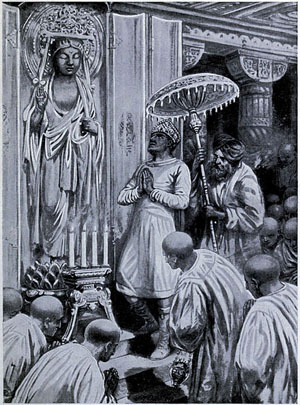

Kanishka's reputation in Buddhist tradition regarded with utmost importance as he not only believed in Buddhism but also encouraged its teachings as well. As a proof of it, he administered the 4th Buddhist Council in Kashmir as the head of the council. It was presided by Vasumitra and Ashwaghosha. Images of the Buddha based on 32 physical signs were made during his time.

He encouraged both Gandhara school of Greco-Buddhist Art and the Mathura school of Hindu art (an inescapable religious syncretism pervades Kushana rule). Kanishka personally seems to have embraced both Buddhism and the Persian attributes but he favored Buddhism more as it can be proven by his devotion to the Buddhist teachings and prayer styles depicted in various books related to kushan empire.

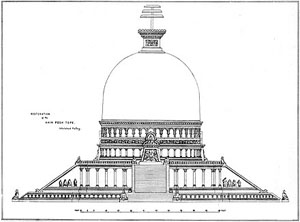

His greatest contribution to Buddhist architecture was the Kanishka stupa at Purushapura, modern day Peshawar. Archaeologists who rediscovered the base of it in 1908–1909 estimated that this stupa had a diameter of 286 feet (87 metres). Reports of Chinese pilgrims such as Xuanzang indicate that its height was 600 to 700 (Chinese) "feet" (= roughly 180–210 metres or 591–689 ft.) and was covered with jewels.[18] Certainly this immense multi-storied building ranks among the wonders of the ancient world.

Kanishka is said to have been particularly close to the Buddhist scholar Ashvaghosha, who became his religious advisor in his later years.

Buddhist coinage

The Buddhist coins of Kanishka are comparatively rare (well under one percent of all known coins of Kanishka). Several show Kanishka on the obverse and the Buddha standing on the reverse. A few also show the Shakyamuni Buddha and Maitreya. Like all coins of Kanishka, the design is rather rough and proportions tend to be imprecise; the image of the Buddha is often slightly overdone, with oversize ears and feet spread apart in the same fashion as the Kushan king.

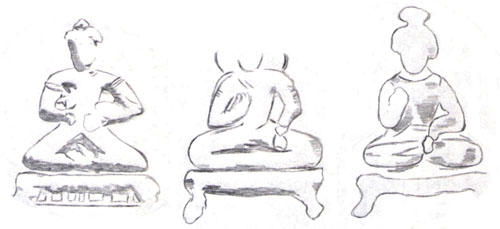

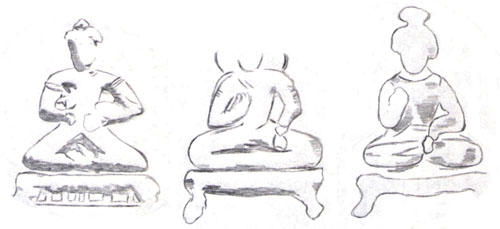

Three types of Kanishka's Buddhist coins are known:

Standing Buddha

Depiction of the Buddha enveloped in a mandala in Kanishka's coinage. The mandorla is normally considered as a late evolution in Gandhara art.[19]

Only six Kushan coins of the Buddha are known in gold (the sixth one is the centerpiece of an ancient piece of jewellery, consisting of a Kanishka Buddha coin decorated with a ring of heart-shaped ruby stones). All these coins were minted in gold under Kanishka I, and are in two different denominations: a dinar of about 8 gm, roughly similar to a Roman aureus, and a quarter dinar of about 2 gm. (about the size of an obol).

The Buddha is represented wearing the monastic robe, the antaravasaka, the uttarasanga, and the overcoat sanghati.

The ears are extremely large and long, a symbolic exaggeration possibly rendered necessary by the small size of the coins, but otherwise visible in some later Gandharan statues of the Buddha typically dated to the 3rd–4th century CE (illustration, left). He has an abundant topknot covering the usnisha, often highly stylised in a curly or often globular manner, also visible on later Buddha statues of Gandhara.

In general, the representation of the Buddha on these coins is already highly symbolic, and quite distinct from the more naturalistic and Hellenistic images seen in early Gandhara sculptures. On several designs a mustache is apparent. The palm of his right hand bears the Chakra mark, and his brow bear the urna. An aureola, formed by one, two or three lines, surrounds him.

The full gown worn by the Buddha on the coins, covering both shoulders, suggests a Gandharan model rather than a Mathuran one.

"Shakyamuni Buddha"

Depictions of the "Shakyamuni Buddha" (with legend [x] "Shakamano Boddo") in Kanishka's coinage.

The Shakyamuni Buddha (with the legend "Sakamano Boudo", i.e. Shakamuni Buddha, another name for the historic Buddha Siddharta Gautama), standing to front, with left hand on hip and forming the abhaya mudra with the right hand. All these coins are in copper only, and usually rather worn.

The gown of the Shakyamuni Buddha is quite light compared to that on the coins in the name of Buddha, clearly showing the outline of the body, in a nearly transparent way. These are probably the first two layers of monastic clothing the antaravasaka and the uttarasanga. Also, his gown is folded over the left arm (rather than being held in the left hand as above), a feature only otherwise known in the Bimaran casket and suggestive of a scarf-like uttariya. He has an abundant topknot covering the ushnisha, and a simple or double halo, sometimes radiating, surrounds his head.

"Maitreya Buddha"

Depictions of "Maitreya" (with legend [x] "Metrago Boddo") in Kanishka's coinage.

The Bodhisattva Maitreya (with the legend "Metrago Boudo") cross-legged on a throne, holding a water pot, and also forming the Abhaya mudra. These coins are only known in copper and are quite worn out . On the clearest coins, Maitreya seems to be wearing the armbands of an Indian prince, a feature often seen on the statuary of Maitreya. The throne is decorated with small columns, suggesting that the coin representation of Maitreya was directly copied from pre-existing statuary with such well-known features.

The qualification of "Buddha" for Maitreya is inaccurate, as he is instead a Bodhisattva (he is the Buddha of the future).

The iconography of these three types is very different from that of the other deities depicted in Kanishka's coinage. Whether Kanishka's deities are all shown from the side, the Buddhas only are shown frontally, indicating that they were copied from contemporary frontal representations of the standing and seated Buddhas in statuary.[20] Both representations of the Buddha and Shakyamuni have both shoulders covered by their monastic gown, indicating that the statues used as models were from the Gandhara school of art, rather than Mathura.

Buddhist statuary under Kanishka

See also: Kushan art

Several Buddhist statues are directly connected to the reign of Kanishka, such as several Bodhisattva statues from the Art of Mathura, while a few other from Gandhara are inscribed with a date in an era which is now thought to be the Yavana era, starting in 186 to 175 BCE.[21]

Dated statuary under Kanishka

Kosambi Bodhisattva, inscribed "Year 2 of Kanishka".[22]

Bala Bodhisattva, Sarnath, inscribed "Year 3 of Kanishka".[23]

"Kimbell seated Buddha", with inscription "year 4 of Kanishka" (131 CE).[24][25] Another similar statue has "Year 32 of Kanishka".[26]

Gandhara Buddhist Triad from Sahr-i-Bahlol, circa 132 CE, similar to the dated Brussels Buddha.[27] Peshawar Museum.[28][29]

Image of a Nāga between two Nāgīs, inscribed in "the year 8 of Emperor Kanishka". 135 CE.[30][31][32]

Buddha from Loriyan Tangai with inscription mentionning the "year 318", thought to be 143 CE.[21]

A Buddha from Loriyan Tangai from the same period.[21]

Kanishka stupa

Main articles: Kanishka stupa and Kanishka casket

Kanishka casket

Remnants of the Kanishka stupa.

Kanishka, surrounded by the Iranian Sun-God and Moon-God (detail)

Relics from Kanishka's stupa in Peshawar, sent by the British to Mandalay, Burma in 1910.

The "Kanishka casket", dated to 127 CE, with the Buddha surrounded by Brahma and Indra, and Kanishka standing at the center of the lower part, British Museum.

The "Kanishka casket" or "Kanishka reliquary", dated to the first year of Kanishka's reign in 127 CE, was discovered in a deposit chamber under Kanishka stupa, during the archaeological excavations in 1908–1909 in Shah-Ji-Ki-Dheri, just outside the present-day Ganj Gate of the old city of Peshawar.[33][34] It is today at the Peshawar Museum, and a copy is in the British Museum. It is said to have contained three bone fragments of the Buddha, which are now housed in Mandalay, Burma.

The casket is dedicated in Kharoshthi. The inscription reads:

The text is signed by the maker, a Greek artist named Agesilas, who oversaw work at Kanishka's stupas (caitya), confirming the direct involvement of Greeks with Buddhist realisations at such a late date: "The servant Agisalaos, the superintendent of works at the vihara of Kanishka in the monastery of Mahasena" ("dasa agisala nava-karmi ana*kaniskasa vihara mahasenasa sangharame").

The lid of the casket shows the Buddha on a lotus pedestal, and worshipped by Brahma and Indra. The edge of the lid is decorated by a frieze of flying geese. The body of the casket represents a Kushan monarch, probably Kanishka in person, with the Iranian sun and moon gods on his side. On the sides are two images of a seated Buddha, worshiped by royal figures, can be assumed as Kanishka. A garland, supported by cherubs goes around the scene in typical Hellenistic style.

The attribution of the casket to Kanishka has been recently disputed, essentially on stylistic ground (for example the ruler shown on the casket is not bearded, to the contrary of Kanishka). Instead, the casket is often attributed to Kanishka's successor Huvishka.

Kanishka in Buddhist tradition

Kanishka inaugurates Mahayana Buddhism

In Buddhist tradition, Kanishka is often described as an aggressive, hot tempered, rigid, strict, and a bit harsh kind of King before he got converted to Buddhism of which he was very fond, and after his conversion to Buddhism, he became an openhearted, benevolent, and faithful ruler. As in the Sri-dharma-pitaka-nidana sutra:

"At this time the King of Ngan-si (Pahlava) was very aggressive and of a violent nature....There was a bhikshu (monk) arhat who seeing the harsh deeds done by the king wished to make him repent. So by his supernatural force he caused the king to see the torments of hell. The king was terrified and repented and cried terribly and hence dissolved all his negatives within him and got self realised for the first time in life ." Śri-dharma-piṭaka-nidāna sūtra[35]

Additionally, the arrival of Kanishka was reportedly foretold or was predicted by the Buddha, as well as the construction of his stupa:

Coin of Kanishka with the Bodhisattva Maitreya "Metrago Boudo".

The Ahin Posh stupa was dedicated in the 2nd century CE and contained coins of Kaniska

The same story is repeated in a Khotanese scroll found at Dunhuang, which first described how Kanishka would arrive 400 years after the death of the Buddha. The account also describes how Kanishka came to raise his stupa:

Chinese pilgrims to India, such as Xuanzang, who travelled there around 630 CE also relays the story:

King Kanishka because of his deeds was highly respected, regarded, honored by all the people he ruled and governed and was regarded the greatest king who ever lived because of his kindness, humbleness and sense of equality and self-righteousness among all aspects. Thus such great deeds and character of the king Kanishka made his name immortal and thus he was regarded "THE KING OF KINGS"[38]

Transmission of Buddhism to China

Main article: Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

Buddhist monks from the region of Gandhara played a key role in the development and the transmission of Buddhist ideas in the direction of northern Asia from the middle of the 2nd century CE. The Kushan monk, Lokaksema (c. 178 CE), became the first translator of Mahayana Buddhist scriptures into Chinese and established a translation bureau at the Chinese capital Loyang. Central Asian and East Asian Buddhist monks appear to have maintained strong exchanges for the following centuries.

Kanishka was probably succeeded by Huvishka. How and when this came about is still uncertain. It is a fact that there was only one king named Kanishka in the whole Kushan legacy. The inscription on The Sacred Rock of Hunza also shows the signs of Kanishka.

See also

• Menander I

• Greco-Buddhism

Footnotes

1. B.N. Mukhjerjee, Shāh-jī-kī-ḍherī Casket Inscription, The British Museum Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1/2 (Summer, 1964), pp. 39-46

2. Bracey, Robert (2017). "The Date of Kanishka since 1960 (Indian Historical Review, 2017, 44(1), 1-41)". Indian Historical Review. 44: 1–41.

3. The Kushans at first retained the Greek language for administrative purposes but soon began to use Bactrian. The Bactrian Rabatak inscription (discovered in 1993 and deciphered in 2000) records that the Kushan king Kanishka the Great (c. 127 AD), discarded Greek (Ionian) as the language of administration and adopted Bactrian ("Arya language"), from Falk (2001): "The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣâṇas." Harry Falk. Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII, p. 133.

4. Falk (2001), pp. 121–136. Falk (2004), pp. 167–176.

5. Puri, Baij Nath (1965). India under the Kushāṇas. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

6. Findeisen, Raoul David; Isay, Gad C.; Katz-Goehr, Amira (2009). At Home in Many Worlds: Reading, Writing and Translating from Chinese and Jewish Cultures : Essays in Honour of Irene Eber. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 138. ISBN 9783447061353.

7. Gnoli (2002), pp. 84–90.

8. Sims-Williams and Cribb (1995/6), pp.75–142.

9. Sims-Williams (1998), pp. 79–83.

10. Sims-Williams and Cribb (1995/6), p. 80.

11. Hill (2009), p. 11.

12. "The Rabatak inscription claims that in the year 1 Kanishka I's authority was proclaimed in India, in all the satrapies and in different cities like Koonadeano (Kundina), Ozeno (Ujjain), Kozambo (Kausambi), Zagedo (Saketa), Palabotro (Pataliputra) and Ziri-Tambo (Janjgir-Champa). These cities lay to the east and south of Mathura, up to which locality Wima had already carried his victorious arm. Therefore they must have been captured or subdued by Kanishka I himself." Ancient Indian Inscriptions, S. R. Goyal, p. 93. See also the analysis of Sims-Williams and J. Cribb, who had a central role in the decipherment: "A new Bactrian inscription of Kanishka the Great", in Silk Road Art and Archaeology No. 4, 1995–1996. Also see, Mukherjee, B. N. "The Great Kushanan Testament", Indian Museum Bulletin.

13. Lo Muzio, Ciro (2012). "Remarks on the Paintings from the Buddhist Monastery of Fayaz Tepe (Southern Uzbekistan)". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 22: 189–206.

14. "Samatata coin". British Museum.

15. Wood (2002), illus. p. 39.

16. Sims-Williams (online) Encyclopedia Iranica.

17. H. Humbach, 1975, p.402-408. K. Tanabe, 1997, p.277, M. Carter, 1995, p. 152. J. Cribb, 1997, p. 40. References cited in De l'Indus à l'Oxus.

18. Dobbins (1971).

19. "In Gandhara the appearance of a halo surrounding an entire figure occurs only in the latest phases of artistic production, in the fifth and sixth centuries. By this time in Afghanistan the halo/mandorla had become quite common and is the format that took hold at Central Asian Buddhist sites." in "Metropolitan Museum of Art". http://www.metmuseum.org.

20. The Crossroads of Asia, p. 201. (Full[citation needed] here.)

21. Rhi, Juhyung (2017). Problems of Chronology in Gandharan. Positionning Gandharan Buddhas in Chronology (PDF). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. pp. 35–51.

22. Early History of Kausambi p.xxi

23. Epigraphia Indica 8 p.179

24. Seated Buddha with inscription starting with [x] Maharajasya Kanishkasya Sam 4 "Year 4 of the Great King Kanishka" in "Seated Buddha with Two Attendants". http://www.kimbellart.org. Kimbell Art Museum.

25. "The Buddhist Triad, from Haryana or Mathura, Year 4 of Kaniska (ad 82). Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth." in Museum (Singapore), Asian Civilisations; Krishnan, Gauri Parimoo (2007). The Divine Within: Art & Living Culture of India & South Asia. World Scientific Pub. p. 113. ISBN 9789810567057.

26. Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007). The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 48, Fig. 18. ISBN 9781588392244.

27. FUSSMAN, Gérard (1974). "Documents Epigraphiques Kouchans". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 61: 54–57. doi:10.3406/befeo.1974.5193. ISSN 0336-1519. JSTOR 43732476.

28. Rhi, Juhyung. Identifying Several Visual Types of Gandharan Buddha Images. Archives of Asian Art 58 (2008). pp. 53–56.

29. The Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford (2018). Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017. Archaeopress. p. 45, notes 28, 29.

30. Sircar, Dineschandra (1971). Studies in the Religious Life of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2790-5.

31. Sastri, H. krishna (1923). Epigraphia Indica Vol-17. pp. 11–15.

32. Luders, Heinrich (1961). Mathura Inscriptions. pp. 148–149.

33. Hargreaves (1910–11), pp. 25–32.

34. Spooner, (1908–9), pp. 38–59.

35. Kumar (1973), p. 95.

36. Kumar (1973), p. 91.

37. Kumar (1973). p. 89.

38. Xuanzang, quoted in: Kumar (1973), p. 93.

References

• Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (in French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 978-2-9516679-2-1.

• Chavannes, Édouard. (1906) "Trois Généraux Chinois de la dynastie des Han Orientaux. Pan Tch'ao (32–102 p. C.); – son fils Pan Yong; – Leang K'in (112 p. C.). Chapitre LXXVII du Heou Han chou." T'oung pao 7, (1906) p. 232 and note 3.

• Dobbins, K. Walton. (1971). The Stūpa and Vihāra of Kanishka I. The Asiatic Society of Bengal Monograph Series, Vol. XVIII. Calcutta.

• Falk, Harry (2001): "The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣâṇas." In: Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII, pp. 121–136.

• Falk, Harry (2004): "The Kaniṣka era in Gupta records." In: Silk Road Art and Archaeology X (2004), pp. 167–176.

• Foucher, M. A. 1901. "Notes sur la geographie ancienne du Gandhâra (commentaire à un chapitre de Hiuen-Tsang)." BEFEO No. 4, Oct. 1901, pp. 322–369.

• Gnoli, Gherardo (2002). "The "Aryan" Language." JSAI 26 (2002).

• Hargreaves, H. (1910–11): "Excavations at Shāh-jī-kī Dhērī"; Archaeological Survey of India, 1910–11.

• Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

• Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (1998). A history of India. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15481-9.

• Kumar, Baldev. 1973. The Early Kuṣāṇas. New Delhi, Sterling Publishers.

• Sims-Williams, Nicholas and Joe Cribb (1995/6): "A New Bactrian Inscription of Kanishka the Great." Silk Road Art and Archaeology 4 (1996), pp. 75–142.

• Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1998): "Further notes on the Bactrian inscription of Rabatak, with an Appendix on the names of Kujula Kadphises and Vima Taktu in Chinese." Proceedings of the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies Part 1: Old and Middle Iranian Studies. Edited by Nicholas Sims-Williams. Wiesbaden. 1998, pp. 79–93.

• Sims-Williams, Nicholas. Sims-Williams, Nicolas. "Bactrian Language". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 3. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Accessed: 20/12/2010

• Spooner, D. B. (1908–9): "Excavations at Shāh-jī-kī Dhērī."; Archaeological Survey of India, 1908-9.

• Wood, Frances (2003). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. University of California Press. Hbk (2003), ISBN 978-0-520-23786-5; pbk. (2004) ISBN 978-0-520-24340-8

External links

• Media related to Kanishka I at Wikimedia Commons

• A rough guide to Kushana history.

• Online Catalogue of Kanishka's Coins

• Coins of Kanishka

• Controversy regarding the beginning of the Kanishka Era.

• Kanishka Buddhist coins

• Photograph of the Kanishka casket

1. From the dated inscription on the Rukhana reliquary

2. Richard Salomon (July–September 1996). "An Inscribed Silver Buddhist Reliquary of the Time of King Kharaosta and Prince Indravarman". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 116 (3): 418–452 [442]. JSTOR 605147.