Part 1 of 2

Chapter 9: Caravanserais Along the Grand Trunk Road in Pakistan: A Central Asian Legacy

by Saifur Rayman Dar

from The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce

Edited by Vadime Elisseeff

Published in association with UNESCO

©2000

Originally published Paris UNESCO, 1998

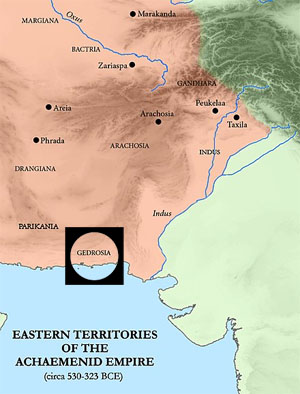

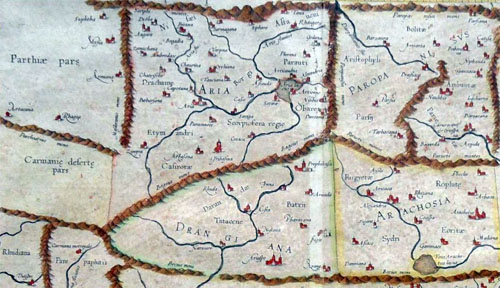

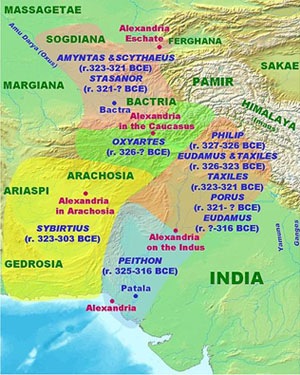

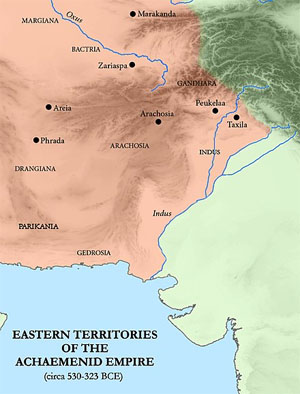

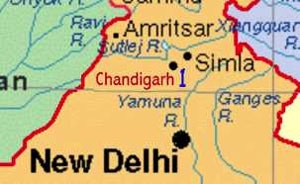

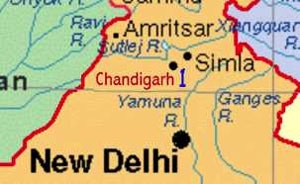

The famous Grand Trunk Road or Shahrah-i-'Azim connecting Calcutta (India) with Peshawar (Pakistan) has been in existence for the last 2,500 years. It has been variously described as "the muse of history,"1 or "a broad scratch across the shoulders of India and Pakistan."2 As the greatest highway in the world,3 it has been compared with the Pilgrim's Way in England, the Appian Way in Rome, and Jada-i-Shah of the Achaemenians.4 The strategic value of this grand highway and the correctness of its alignment have stood the test of time for more than 2,500 years. The rising British power withstood the ferocious war of independence -- the so-called Mutiny of 1857 -- thanks to this well-planned and well-maintained Grand Trunk Road (GTR).5

All along this highway, there once stood forts (qila), fortified towns (qila band shehr), army halting posts (parrao or chhaoni), caravanserais, dak-posts (chowki), milestones (kos minars), stepped wells (baoli) and, of course, shady trees for the convenience of travelers and passers-by. The present chapter deals briefly with a survey of existing remains of these facilities along the part of the GTR which runs through present-day Pakistan. This survey was carried out by the author during the years 1987-1989. The area interested me for three reasons:

(i) It covered one fifth of the total length of the GTR.

(ii) Part of the Silk Road passing through Pakistan also corresponds to the GTR,6 and

(iii) The portion of the GTR passing through Pakistan certainly comprises the most varied and difficult geographical and geological land mass ever encountered by a road builder7 or a merchant, or even a soldier.

History

No one knows when the GTR [Grand Trunk Road] started. Presumably, it came into existence as soon as vehicular traffic started developing as a complement to river communication. There were numerous such major roads connecting different parts of the vast country. Panini, the famous grammarian (500 B.C.), mentions the existence of an Uttarpatha (Northern Road) as well as Dakshinapatha (Southern Road).8 There was also Vannupatha: The Road from Bannu from the Middle Country passing through a desert. Uttarpatha probably was the same as Kautilya’s Haimavatapath running from Vallika (Balkh or Bactria) to Taxila. Kautilya also gives detailed advice as to different types of roads which a king should build. These include the roads linking different national or provincial centers, those leading to military camps and forts, and roads for chariots, elephants, and other animals together with their respective widths and how to maintain them.9 There is a mention of trade routes (water routes and land routes) and it was the duty of the emperor to maintain them and keep them free from harassment by the king’s favorites, robbers, and herds of cattle.10 The width of a royal highway and those within a droonamukna and a sthaniya or a harbor town were fixed at eight dandas or forty-eight feet.11 The Royal Road of the Mauryans at the beginning of the 3rd century B.C., according to Megasthenes, used to run in eight stages from Purushupura (Peshawar) in the northeast to Pataluputra, the Mauryan capital, in the extreme east.12 Sarkar has given details of these eight stages, three of which fell within today’s Pakistan, namely Purushupura to Takshasila, Takshasila to Jhelum, and Jhelum to Alexander’s Altars on the Beas River.13 To help travelers on this Road, directions and distances were indicated with the help of stone pillars fixed every 10 stadia or one kos.14 These correspond to the medieval kos minar or modern milestone. It is quite possible that Chandra Gupta took this idea of a Royal Road from the Jada-i-Shah of the Achaemenians and this, along with other facts, became instrumental in bringing in the Persian influence which we encounter in Mauryan art. There were charitable lodging houses (dharma vasatha) inside the cities for heretical travelers, ascetics, and Brahmins15 but there is no mention of similar facilities alongside the highways. Chandra Gupta’s grandson Asoka improved upon this road system, as he proudly claims in one of his edicts, by planting trees, digging wells every half kos, and building nimisdhayas all along the Royal Road.16 The word nimisdhayas has been variously interpreted17 but is usually translated as rest-house. Sirkar has accepted it to mean a sarai or hostelry.18 If so, this is the earliest reference to halting stations provided on high roads. Still, Asoka was certainly not the originator of such facilities on the highways because he admits that such comforts were provided by previous kings as well. Earlier Kautilya had advised kings to provide sources of water (setu), land routes and waterways (varisthalapatha), groves (arama), and the like.19 Besides, from various jataka stories, we learn that each caravan was led by a caravan leader, the Sarthavaha, who would decide where to make halts for the night showing thereby that there were no fixed and permanent halting stations on the way.20

The introduction of baolis (or vapis) – stepped walls along the high roads in the subcontinent of Pakistan and India – is attributed to Central Asian people. It is believed that in the second century B.C., the Sakas, in their second wave, introduced here two types of wells – Sakandu and Karkandhu – the former being the stepped well whereas the latter was the Persian wheel.21

Kanishka definitely had control over the Uttarapatha which then formed a part of the Silk Road which now, thanks to the Roman Empire, turned towards the sea coast near Barbaricon or Barygaza. The presence of numerous Indian carved ivories and other works of art from western marts discovered at Begram22 near Hadda testify to this. Various Chinese pilgrims from the fifth to the seventh centuries A.D. also used various land routes to enter northern Pakistan – Fa Hien (c. A.D. 400) and Sung Yun (c. A.D. 521) through Udyana (modern Swat), and Hieun Tsang (seventh century A.D.) through Balkh-Taxlia.23 This also shows that these roads must have been quite busy in those times. It was along these routes that Buddhism and the influence of Gandhara art in particular and art of India in general penetrated Central Asia and far into mainland China.24 These Chinese travelers did not mention the existence of proper inns anywhere on this high road though such facilities had existed within the limits of cities since the time of Kautilya.25 Perhaps they never needed to stay in such places, as they normally stayed in Buddhist monasteries which they found on their way.

Even during early Muslim rule in the subcontinent we have very little knowledge as to how the ancient highways worked and what roadside facilities existed for the comforts of travelers prior to the coming of the Mughals. The first specific reference to roadside inns or sarais is found during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq (A.D. 1324-1351) who contracted sarais, one at each stage, between Delhi and his new capital Daultabad.26 From Shams Siraj Afeef, author of Tarikh-li-Firoze Shahi, we also learn that his successor, Firoze Shah Tughlaq (A.D. 1351-1387), built several buildings including 120 hospices and inns, all in Delhi, for the comfort of travelers.27 In these sarais, travelers were allowed to stay and eat free of charge for three days. After this fashion, Mahmud Baiqara (A.D. 1458-1511) built numerous beautiful sarais in Gujrat for the comfort and convenience of travelers.28 Almost simultaneously, Sikander Lodhi (A.D. 1488-1517) of Delhi also built sarais, mosques, madrassahs, and bazaars at all such places where Hindus had their ritual bathing sites.29

But it was Sher Shah Suri who revived the glory of the Royal Road of Chandra Gupta Maurya and at the same time excelled in providing roadside facilities to the travelers to such an extent that today the Grand Trunk Road and Sher Shah Suri have become synonyms. He ensured that the road journeys between all important centers in his empire, particularly between Sonargaon in Bengal and Attock Banares on the Indus River, were safe and comfortable. He realigned the Grand Trunk Road and Sonargaon at Rhotas, widened it, planted fruit-bearing and shady trees at the sides, constructed sarais every 2 kos,30 and introduced kos minars and baolis at more frequent intervals in between two sarais. Along some other roads, Gaur to Oudh and one from Benaras, for example, besides sarais and fruit-bearing trees, he also planted gardens.31 It has been recorded that, in all Sher Shah built 1,700 sarais throughout the length and breadth of his empire. In some history books the total number is exaggerated to 2,500.32 Nadvi has estimated that there were 1,500 sarais between Bengal and the Indus alone. From some history books, we get a fair idea as to how these Suti sarais looked and how they were maintained. Briefly, these were state-run establishments used both as dak-posts and as resting places for travelers. In these sarais, free food and lodging were provided to all, irrespective of their status, creed, or faith.

Islam Shah (Saleem Shah) succeeded his father, Sher Shah Suri, and ruled from A.D. l1545 to 1552. Along the road to Bengal, he added one more sarai in between every two built by his father. Following traditions established by his father, he continued to serve food, both cooked and uncooked, to travelers.33 In Pakistan, the Kachi Sarai at Gujranwala (now demolished except for its mosque) and the so-called Akbari Sarai, adjacent to Jangir’s Mausoleum are attributable to the Suri period, the latter to Islam Shah Suri.34 During the reign of Akbar the Great (A.D. 1558-1605) the system of having halting places (sarais, dak-cowkis, and baolis) along important roads was further developed and perfected. Not only did the emperor himself build numerous new sarais at different locations, but his courtiers followed suit.35

Jahangir (A.D. 1605-1628), in particular, issued orders that the property of all such persons who die without issue be spent on the construction of mosques and sarais, the digging of wells and tanks, and the repairing of bridges. Simultaneously he ordered the landlords of all such far-off places where roads were not safe, to construct sarais and mosques and dig wells so that people were encouraged to settle near these places. Jahangiri sarais are said to have existed eight kos apart from one another. Jahangir ordered these sarais to be built of stone and burnt brick (pakkalpukhta sarais) and not of mud (kacha sarais). In each of his sarais there were proper baths and tanks of fresh water and regular attendants. Mulberry and other broad-leaved trees were planted at various halting stations between Lahore and Agra.36 Jahangiri kos minars -- such as one each at Manhiala near Jallo and at Shahu Garhi in Lahore -- were between twenty and thirty feet high. The emperor's courtiers too built rabats.37 Besides repairing the old bridges, Jahangir also constructed several new ones over all such rivers and nullahs which came in the way of his highways.38 On the highway leading to Kashmir, he built permanent houses at different stages so that he need not carry tentage with them.39

Shah Jahan's period (1628-1658) is renowned for its building activities. The emperor busied himself with constructing and embellishing royal buildings in Agra, Delhi, and Lahore. His courtiers followed suit.4o Several of his nobles, such as Wazir Khan, are renowned for patronizing building activities. The construction of roads and sarais did not lag behind, though these never had the same attention they received from Jahangir. The bridge of Shah Daula on Nullah Deg on the way from Lahore to Eminabad is definitely a construction from Shah Jahan's period.41 Wazir Khan sarai (now extinct) was built near his grand public hamam inside Delhi Gate. Lahore was also constructed during this period.

Despite this increased activity, the road between Lahore and Kabulthe most important of all highways in ancient India-never had enough sarais at the desired places. Consequently, travelers had to contend with many difficulties while traveling on this section. It was Aurangzeb Alamgir (1659-1707) who realized this. He ordered that, in all parts where there were no sarais and rabats, permanent (pukhta) and commodious sarais should be constructed at government expense. Each new sarai was required to comprise a bazar, a mosque, a well, and a hamam. Older sarais were equally properly attended to and were soon repaired whenever necessary. 42 Some of his noblemen, such as Shaista Khan also built new sarais.43 Khan-i-Khanan, a Wazir of Shah Alam Bahadur (1707-1712) had ordered that each city must have a sarai, a mosque, and a hospice constructed in his name.44 He even despatched funds for that purpose. Amirud Din Sambhli, a courtier of Muhammad Shah (1719-1748), built a beautiful sarai in Sambhal.45 Nawab Asif Jah, during the reign of the same king, built a caravanserai and bridge in Deccan.46 Hussain Ali Khan of Barha built a sarai and a bridge in his locality.47

After the death of Muhammad Shah in A.D. 1748, the Punjab suffered a severe political setback. Central power declined and provincial Subedars of Lahore fought incessantly against invading Durranies and Marathas and the rising power of the Sikhs. Roadways were no longer safe and sarais were unattended to. In A.D. 1799, the Punjab was entirely taken over by the Sikhs. Their rule is a story of inverse development as far as architectural activities are concerned. In a state of political anarchy that characterized most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the highways became the wounded arteries of national life which drained the blood from the economic body of the country. I do not know if ever during this anarchical period a new sarai was constructed or orders were given to repair the old ones.

When the British occupied the Punjab in 1849, they did not fail to realize that it had always been the gateway to the whole of the subcontinent, and that the Grand Trunk Road was of special significance to this area in particular and to the whole subcontinent in genera1.48 If the danger from the northwest was to be checked and local reserves of fighting men were to be tapped properly to reinforce the British army, this highway must be kept in first-rate condition and further improved. The first twenty-seven years of their reign, therefore, were spent in realigning this highway, making it metaled, constructing bridges, causeways and culverts wherever needed, and building their own sarais. It has been said that the terrain as followed by this highway in the Punjab is perhaps the most difficult and varied ever met by a road-builder. The story of the reconstruction of this highway has been graphically told by K.M. Sarkar in the work quoted above. The new road thus reconstructed hardly differed from the original alignment of the Mughal Highway. More often than not, it followed the former alignment, while at other places it ran parallel to it. Almost all old stations on the GTR such as Sarai Kachi (Gujranwala), Gakharr Cheema, Wazirabad, Gujrat, Kharian, Sarai Alamgir, Rewat, Margalla, Sarai Kala, Sarai Hasanabdal, Begum-ki-Sarai, and Peshawar, still occupy strategic positions on the new GTR. A few others such as Sarai Sheikhan, Eminabad, Khawaspura, Rohtas, Sarai Sultan, Sir Jalal, and Sarai Pukka are not far from it. One has to read the account of the Mughal Highway as given by William Finch49 and compare it with the British Highway as rebuilt from 1849 to 188650 and see how, right from the beginning, the route from Kabul to Peshawar and from Peshawar to Lahore, from most ancient to modern times, has practically never changed. The neywork of the routes in medieval India and Pakistan and the Mughal period and even today passed the cities built during the Sultanate period, bearing in mind the course of ancient routes. If something has changed, it is the institutions of sarais. Better roads, improved means of communications, better transport facilities, lack of time available to individuals, and fast-moving life obliterated the need for caravans to move in groups, the necessity of having night stopovers on the way, short halts for shade under fruit-bearing trees or beside stepped wells, and for taking direction and distances from huge kos minars on the way. The course of the modern GTR has shifted slightly towards the south here and there because traveling in the cool shade of the Himalayan foothills is no longer necessary.

This is the reason why all old sarais, baolis, kos minars, and even ancient bridges have become derelict and are vanishing quickly. It is time for the department concerned to step forward and save these historical landmarks.

Features and Functions of Mughal Sarais

Thus, although the initial alignment of the present-day GTR in Pakistan may date back to a very remote age, provision of various kinds of facilities for travelers on this highway started quite late. We have seen how our information on the subject prior to the coming of the Mughals in the sixteenth century AD. is scanty and incomplete. However, with the coming of the Mughals, the vista of our information, visual and literary, broadens considerably. We now have a well-established empire, with emperors eager to provide their empire with a solid foundation based on a well-organized road system, safe and quick communication, and safe and comfortable road journeys for armies, caravans, and individuals. We now have sufficient, though still not ample, information on how the system worked. Besides, we still have sufficient structural remains scattered allover the country to assist us in visualizing the entire system and interpreting its various functions. Here is a brief account of the system from A.D. 1526 to 1886.

Transport system

To begin with, it should be clear that from the Mauryan to the Mughal periods, traveling within the country, both for local people as well as foreigners, was regulated and controlled through a system of passports (mudra) duly issued and sealed by the Superintendent of Passports (Mudradhyaksha). At various points, there were inspection houses manned by the Superintendent of Meadows (Vivitadhyaksha) who would examine the traveling document of each party passing through that post. What these Inspection Houses looked like, we have no idea. 51

Suri sarais

The first clear picture of a sarai-as an institution and a building -- emerges during the reign of Sher Shah Suri and his son Salim (Islam) Shah Suri (A.D. 1539-1552). Suri sarais were built a distance of two kos apart with stepped wells (baolis, vapis, van or vao) and kos minars at more frequent intervals between every two sarais. Structurally, a sarai comprises a space, invariably a square space, enclosed by a rampart with one gateway called darwazah. As these ramparts were built with sun-dried bricks, they were referred to in later years as kacha sarais and compared to pakka or pukhta sarais of the Mughal period which were built of burnt bricks or stone blocks. Each sarai had rows of cells (khanaha) on all four sides. There were special rooms, one in each corner, and invariably in the center of each wall as well. These were called Khanaha-i-Padshahi, i.e., King's House or Government House reserved for state personnel on the move. There were separate khanaha or cells for Muslims and non-Muslims -- each served by attendants of their respective faiths. Inside each sarai there was a mosque and a well. Revenue-free land (madad-i-maash) was attached to each sarai to meet the salaries of the staff and other contingent expenditure. 52

The sarai acted both as a wayside inn for travelers and an official dak-chowki. Each sarai was run by an official called Shahna or Shiqdar with a number of caretakers (nigehban or chaukidar) to assist him. There was an imam of the mosque and a muezzin to call to prayer. Hot and cold water, together with bed-steads (charpai), edibles (khurdanz), and grain and fodder for the horses (dana-i-asp) were provided by the Government (Sarkar) free of charge. A physician was stationed at every sarai to look after the health of the people of the locality. Bakers were also settled in the sarais.53

Although there are many sarais attributed to the Suri period, only one definite Suri sarai of the type described above is reported in Pakistan. It was in Gujranwala and was called Kachi Sarai. It was extant until the 1950s but has since vanished except for its mosque. The model laid down by the Suri kings was never forgotten by later rulers. What we can observe in later period sarais is only an improved reflection of the prototype of Suri sarais.

Rabats, sarais, and dak-chowkis

According to Arthur Upham Pope, rabats were fortified frontier posts which, during the early Islamic period, were set up as a necessary defense against hostile non-Muslim peoples.54

While discussing the recently discovered Ghaurid period Mausoleum of Khaliq Wali at Khati Chour, Holy Edwards, an American scholar, pronounced this unique fortress-like mausoleum as being a rabat in its original conception. She has described a rabat as a small military outpost on the frontier of a kingdom or state that also accommodates small groups of travelers. If we accept this definition, we have this exceptional example in Pakistan.

Many scholars, on the other hand, regard rabat and sarai as one and the same thing. But there is a minute difference between the two. In Ma'sr-ul-Umara, we learn that Shaikh Farid Murtaza Khan Bukhari, a courtier of Jahangir, built several rabats and sarais. 56 Maulana Nadvi57 has made it clear that sarais were built alongside the highways for temporary stopovers by travelers whereas rabats and khanqahs (hospices) were built inside cities where people could stay for a longer period. These can be considered as guesthouses (mehman khana) or some type of hostelry-although they have never been mentioned under this title.

The Sarais of Sher Shah served both as sarais and dak-chowki and for that purpose two horses were kept in every sarai to convey news to the next station. 58 However, some scholars regard caravanserais as distinct from sarais-cum-dak-chowkis. The former concept developed in Pakistan, northern India, and Gujrat only in the fifteenth century. Caravanserais were invariably private establishments or created by endowments, whereas dak-chowkis were state properties. The dak-post-cum-sarai were usually smaller in size than the sarais. Postal messengers and noblemen (Mirzas) were not supposed to stay in caravanserais which were usually reserved for middle-class people, businessmen, and merchants. In caravanserais, again, the clients were charged moderately but not so in sarais-cum-dak-posts. Caravanserais in cities were usually established by endowments by individuals, organizations, and even by governments but gradually these tended to become rent-yielding properties.

Purpose

The Mughal rulers took upon themselves the responsibility of building roads and bridges and providing halting stations along the way because such arrangements were beneficial militarily, economically, and socially. An efficient road system, with well-supplied halting stations, secure highways, and well-protected fortified places -- as these sarais always were-guaranteed easy passage for armies to guard their frontiers. It also encouraged the caravans and merchants to move along with their valuable merchandise from one place to another with a feeling of security. Establishment of sarais also provided people of the area with ample opportunities for employment and services. Major cities and towns subsequently developed around many sarais built in isolated places. Of course, in times of war and invasion, the villages and cities located on more frequented routes suffered a lot too. Sarais and dak-chowkis helped develop an efficient system of postal communication. Buildings which were just dak-chowkis were also constructed at certain places. One such dak-post, recently repaired under the supervision of the author, can be seen next to the roadside near Wazirbad. The sarais with their monumental gateways, baolis with their towering pavilions, and kos minars with cylindrical masonry columns, 20-30 feet high, guided travelers and caravans to their destinations and helped them cover long distances. Resting places and road-markers such as sarais, kos minars, and baolis were actually an outcome of the development of a centralized state.

Types

A cursory classification of existing remains of known caravanserais along the GTR from Peshawar to Delhi reveal at least five types according to their architectural features and functions:

The Fort-cum-Sarai

Every sarai was basically fortified in a sense that its gates or gate were closed at night and that its four wells usually had no other outlets except the main gate or gates. The earliest type we come across had only one gateway and four solid cornered bastions. Sarai Damdama, Mathura, of the sixteenth century but of pre-Mughal days, with solid pentagonal bastions, is one such example. No such example has survived in Pakistan. The Gakhar period Sarai Rewat, usually called Reway Fort near Rawalpindi can perhaps be classified in this category because it has merlons on the walls, high enough to conceal a soldier behind each, and rows of single cells below without having a veranda in front of each cell as is usual in all sarais. But it is unique in that it has three gates instead of one as in the pre-Mughal era.

The Wayside Sarai

This was perhaps the most common type seen along the roadsides running between big cities or urban centres. It differs from the fort-cum-sarai in two respects. It always had two gateways and usually a few larger rooms (Khanaha-i-Padshahi) in the four corners with side walls. The Akbar period sarai at Chapperghat, south of Kanauj,59 Sarai Nur Mahal in India, Begum-ki-Sarai (of the Akbar or Jahangir period, though with a single gateway), and Sarai Kharbuza Qahangir period) near Rawalpindi, in Pakistan, are good examples. In such sarais, there was usually a bazar, a mosque, and a well-all within the four walls of the sarai.

The town-sarai or rabat

This type of sarai was built as an integral part of an urban center. The Agra Gate Sarai at Fatehpur Sikri and Sarai Ekdilabad, District of Etawa (Shah Jahan period) in India are perhaps good examples. The Sarai Wazir Khan adjoining Delhi Gate in Lahore60 with its colossal public hamam is one example in Pakistan. But its full plan is difficult to exhume today owing to the erection of modern buildings on the site. At least one scholar has interpreted the original building of Khaliq Wali Tomb at Khati Chaur as a rabat with the meaning of a military border post-cumsarai (see above: rabat-sarai and dak-chowkis).

The custom-clearing sarai/sarai with double compound

The Badarpur Sarai near Delhi, with its two compounds, joined together through a common gateway, is unique. Here, entry to the bigger sarai would be through its northern gate, where the traveler waited before being allowed to pass into the adjoining smaller sarai through the connecting door and went out through the southern gate of the smaller sarai after his documents had been checked and clearance obtained. No such type has ever survived in Pakistan.

The mausoleum-cum-garden sarai

This type comprises sarais attached to a garden or mausoleum. The Arab sarai attached to Humayan's tomb in Delhi and the so-called Akbari Sarai attached to Dilamiz Garden (later the Jahangir's Mausoleum) at Shahdara near Lahore are such examples. The mosque of Sarai Akbari certainly belongs to the Suri period, though its rows of cells and three gates belong to the Shah Jahan period. One of the gates provides access to the mausoleum-garden of Jahangir.

The farood gah or royal halting station

Though this is not a typical caravanserai, it belongs to that category because it also served as a temporary halting station, though only for royalty. A typical example of such a halting station is the Wah Garden together with its hamam and an attached forood gah or resting-house. The Hiran Minar near Shaikhupura together with its royal residence, a vast tank and double story pavilion61 can also be regarded as such though it provided a temporary halt for the emperor and his entourage but for an altogether different purpose, namely hunting, shooting, and recreation.

Gateways

The earliest sarai of the Suri period, or even earlier, had only one gateway in one of its four walls. This type continued during the Akbar period as shown by the Arab Sarai at Delhi and Begum-i-Sarai at Attock with only one entrance gate. Normally, Mughal period sarais had two monumental gateways-one located in front of the other in two walls facing each other. Akbari Sarai at Shahdara, Sarai Kharbuza near Rawalpindi, and Pakka Sarai near Gujar Khan are such examples. Two nearer examples in the Indian Punjab are the Jahangir period sarai at Fatehbad62 and another at Doraha.63 A gateway seldom had a fixed size in relation to the size of the sarai itself. It was usually built high and monumental so that it was visible even at a distance, thereby serving the same purpose as that of a kos minar. As seen in the case of Fatehabad and Ooraha Sarais, the gateways were invariably decorated with variegated designs set in a mosaic of glazed tiles. Unfortunately, no such decoration has survived in any of the sarais recorded in Pakistan. These gateways were often two stories with enough rooms to accommodate the shiqdar or shahna and nigehbanl chowkidar. See for example the gateways of Akbari Sarai, Sarai Pakka, and Sarai Sheikhan. The main gateway of Sarai Rewat in its eastern wall looks as if it has two storeys but actually it is a single-storey structure without an elaborate system of attached rooms.

Shapes.

As a rule, all sarais were square in shape. However, in certain cases and depending on the lie of the ground, one side was slightly larger than the other. In Pakistan, Sarai Kharbuza (420' x 420'), Begum-ki-Sarai (323' x 323'), and Sarai Pakka (300 x 300 paces) are examples of perfect squares. The Gakkhar period sarai at Rewat (323.6' x 321.6') and Sarai Sultan (560' x 540') are almost square. Sarai Akbari at Shahdara (797' x 610') is oblongish, whereas Sarai Kala near Taxila is a perfect rectangle (137.5' x 375') with a single (?) gate in its eastern wall. This shape was by choice and not dictated by the terrain. The only other example of a perfect rectangle that has come to my knowledge so far is Raja-ki-Sarai (Agra) with its two gateways set in two shorter walls and one in a longer wall. The gateway of Sarai Kala has been set in one of the long walls. On the Ferozepur Road, near the Central Jail, there used to be a Jahangir period sarai called Sarai Gola Wala,64 which is reported to have been octagonal in layout like some Persian sarais.65 The Sarai Agra Oarwaza ar Fatehput Sikri is irregular in shape.

Disposition of Cells

Inside a sarai, living quarters comprised cells which were invariably of uniform size in all four walls. In front of each cell there was usually a veranda to provide protection from sun and rain as well as to admit indirect light into the cells. No window or ventilator was allowed inside the cell. Sarai Rewat is the exception where there is no veranda in front of the cells. The corner rooms (octagonal or round) were usually set inside the corner bastions and were always larger than the normal cells. These were used by dignitaries or even used as stores. Like ordinary cells, corner rooms too were not provided with a window or ventilator. However, the corner rooms of the Begum-ki-Sarai are exceptions to this rule. Here, all four corner rooms have openings. The openings in two octagonal corner bastions along the western wall provide a beautiful view of the mighty Indus river. The corner rooms of this sarai are the most elaborate. Each is a suite of one large elliptical hall with a veranda in front, an octagonal room at the back, two side rooms, and a set of two staircases leading to the roof We see the comparable arrangement at Sarai Rewat and Sarai Kharbuza. Only Sarai Sultan near Rohtas has a set of larger rooms in the center of the eastern and western walls like the ones in Ooraha Sarai already quoted. Sometimes, in one of the corner rooms, a Turkish hamam was installed such as in Ooraha Sarai just referred to. These hamams inside a sarai were first introduced by Jahangir and copied by some later rulers. But no sarai with a hamam has been reported in Pakistan. Only Oamdama Sarai, Mathura, had solid pentagonal corner towers. All others are either octagonal or circular and are always hollow. The corner tower rooms at Akbari Sarai are square with chambered corners from within and each has a set of two small adjoining oblong rooms. Sarai Kharbuza near Taxila, on the other hand, has two octagonal rooms one set behind the other in each corner. The back room is actually a corner bastion protruding outside the walls of the sarai.

Mosque, bazar, and well inside a Sarai

If there were two gates to a sarai, there was often a bazar in the center of each sarai running from gate to gate.66 It probably comprised of shops of makeshift materials as no permanent structure has ever been discovered inside a sarai. In Pakistan, probably, the Sarai Rewat, Serai Kharbuze, Akbari Sarai at Shahdara, and Sarai Sultan, Rohtas had this arrangement. Elsewhere only at Agra Gate Sarai, Fatehpur Sikri was there a row of permanent shops, but then these were along the outer facade of the sarai and not inside it.67

Somewhere in the open courtyard, a mosque was provided for the faithful such as in Pakka Sarai, Begum-ki-Sarai,68 Sultan Sarai, and Sarai Kharbuza. At times, such a mosque was constructed in the middle of the western wall of the Sarai-as in Akbari Sarai, Sarai Rewat, and Sarai Kala. At the last site, it is slightly off-center. The mosques inside the sarais ranged from a single-domed chamber (as in Sarai Pakka and Sarai Kharbuza) to imposing three-domed structures as seen in Sarai Akbari and Sarai Rewat. Sarai Pakka is unique in that it originally contained two mosques, one for men in the courtyard (it was intact until 1968 when I studied it for the first time but has now been rebuilt completely) and another for women in the western wall (now in complete ruins). Except in the case of sarais close to urban centers, mosques were excluded from the four walls of a sarai such as Chapperghat Sarai.

Invariably, close to the mosques inside the sarai was a burnt-brick well such as in Pakka Sarai, Sarai Sheikhan, Sarai Kharbuza, and Sultan Sarai. Wells catering for the needs of Begum-ki-Sarai, Akbari Sarai, and Sarai Rewat can be found outside the four walls of the sarais proper. The well inside Sarai Kharbuza was in the form of a baoli or vao. As in case of Sarai Sultan and Sarai Pakka, baolis are sometimes found immediately outside a sarai.

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Part 2 of 2

Staircases

At the main gateways, staircases of two stories were usually provided on either side. Usually staircases were also provided at one or both sides of the special rooms (Khanaha-i-Padshah) or the corner bastions such as at Pakka Sarai and Begum-ki-Sarai.

Parapets

Parapets were usually in the form of medium-sized battlements such as in Begum-ki-Sarai or Sarai Rewat. The merions in the case of Rewat give it the appearance of a fortress. But at other places, such as Sarai Kharbuza and Sarai Pakka, the parapets are simple and plain.

Inscriptions

No proper inscription has been found in any of the surviving sarais in Pakistan. Only some scribbling belonging to different periods has been reported from Begum-ki-Sarai at Attock.69 Outside Pakistan, two Persian inscriptions are known from Sarai Ekdilbad, near Etawa, commemorating the simultaneous construction of a mauza (villageltown), a sarai, and a garden by Shah Jahan.70 Sarai Amanat Khan, built in 1640-1641 by Ahmanat Khan himself, the famous calligrapher of the Taj Mahal, also bears a dedicatory inscription on the west gate71 Sarai Nur Mahal near Phillour (East Punjab, India), the most impressive of all sarais in the Punjab built by Empress Nur Jahan, also bears a dedicatory inscription with two dates A.H. 1028 (A.D. 1618) and A.H. 1030 (A.D. 1620).72

Hamams

Turkish hamams of the Roman thermae type were a speciality of the Mughals and were introduced by them into the subcontinent. Their palaces (Lahore Fort), gardens (Shalamar, Lahore, and Wah Gardens at Hasanabdal), and even some of their sarais (Sarai Itamadud Daula at Doraha), were provided with elaborate hamams. It was Jahangir (A.D. 1605-1628) who introduced hamam into sarais. This practice was continued by others. In none of the sarais in Pakistan is such a hamam known to have survived. However, we have a beautiful and colossal public hamam, attached to, though structurally detached from, Sarai Wazir Khan, inside Delhi Gate, Lahore. It has now been renovated. Wah Gardens, a place officially known as Farood Gah-i-Shahinshah-i-Mughalia or the Resting Place of the Mughal Emperors and therefore to be considered as a category of sarai or temporary residence, has an elaborate hamam of which only the foundations have survived.73

Distances

There is some confusion as regards the exact distance between two sarais, baolis, and kos minars of the Mughal period. The difficulty is due to the conversion of a kos or krohlkrosa into English miles. The former appears to have been measured differently at various times. We know from Sarwani that Sher Shah built his sarais at a distance of two kos.74 His son Salim Shah added one more sarai in between every two built by his father. Thus making the distance between two sarais equal to one koso Sarkar, on the other hand, states that Suri sarais were situated 10 kos apart75 whereas sarais of Jahangir's period according to his own decree were 8 kos apart on the road from Agra to Lahore?6 Following this, the East India Company established Dak bungalows on the highways at 10 mile intervals.77 But, on the other hand, we know from Akbar Nama that the distance between Sarai Hasanabdal and Sarai Zainuddin Ali on the way to Attock was 4.25 kroh and 5 mans (app. 5 krohs as usually accepted) which is usually estimated to equal 10.5 English miles.78 Now, the Akbari kroh has been estimated to equal 5,000 ilahi gaz (of 30" length) or 4,250 English yards.79 As the distance between Peshawar and Lahore is about 264 miles, there must have been at least 26 sarais between these two stations, of which 20 can easily be recognized or presumed to have existed.

Attendants

Nicholas Withington (1612-1616) while writing about a sarai between Ajmer and Agra talks about "hostesses to dress our victuals if we please."8o Peter Mundy also talks about female attendants in sarais.81 However, no such reference has ever been made by a native writer. Perhaps they refer to female attendants, who together with their males were appointed to cook food for travelers in these sarais and about whom Khafi Khan has written that all Bhatiaras and Bhatiarnain of India are the descendants of these very cooks (nan-bais).82

Charges

We know that in the early days of the sarais, both accommodation and food were free. During the Mauryan period, there used to be charitable lodging houses under government control wherein free accommodation was granted to heretical travelers and to ascetics and Brahmins, whereas artisans, artists, and traders were required to lodge with their co-professionals in what can be called as guest-houses attached to their places of work.83 During Feroze Shah Tughlaq's reign, travelers were provided with free board and lodging for three days. However, some of the sarais, especially those created out of endowments, tended to become rent-earning establishments. Sarai Wazir Khan, inside Delhi Gate, Lahore was certainly one such example whose income, together with that of the grand hamam nearby, supported Wazir Khan's Mosque.84 We also learn from some early western travelers that the charge per room around 1634 was about 1 to 3 pice and 3 dams per day inclusive of stabling for horses and cooking space.85

Caravanserais Remains

Our knowledge of caravanserais along the Grand Trunk Road between Calcutta and Agra-Oelhi is perfunctory. However, under Mughal rule -- particularly from Jahangir onward-we are not that poor as regards written information and even actual remains, particularly for the part of ancient GTR that stretched from Agra to Lahore and onward to Peshawar. We have an almost perfect alignment of the road from Agra to Lahore as it existed in 1611 and described by William Finch. He lists the following important stations on this section: Agra, Rankata, Bad-ki Sarai, Akbarpur, Hodal, Palwal, Faridabad, Delhi, Narela, Ganaur, Panipat, Karnal, Thanesar, Shahabad, Ambala, Aluwa Sarai, Sirhind, Ooraha (Sarai), Phillaur-kiSarai, Nakodar, Sultanpur, Fatehpur (Vairowal), Hogee Moheed (Taran Taran?), Cancanna Sarai (Khan-i-Sarai), and Lahore.86

Ruins of some interesting sarais are still traceable in that part of the GTR which once passed through Haryana and the East Punjab in India. These include Nur Mahal Sarai near Phillaur built by Empress Nur Jahan; the Sarai at Ghauranda between Panipat and Kamal; Sarai Amanat Khan on the Taran Taran-Attari Road built by Amanat Khan, the calligrapher of the Taj Mahal; Ohakhini Sarai south of the village of Mahlian Kalan on the Nakodar-Kapurthala Road; Ooraha Sarai at Ooraha south of the Ludhiana-Khanna Road; and Sarai Lashkari Khan twelve kilometers west of Khanna on the GTR in the Ludhiana district.87

Sarai Amanat Khan is probably the last existing stretch of the GTR, before the latter enters into present-day Pakistan via Burj and Raja Tall in India to Purani Bhaini in Pakistan and then straight to Manhala Khan-i-Khanan after the name of Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khan, the famous general of Akbar and Jahangir. Our journey along the GTR in Pakistan begins here. Here once stood the Sarai Khan-i-Khan, most probably the Cancanna Sarai already mentioned by William Finch. This sarai is no more. But, outside the village, a Mughal period kos minar, one of a pair in the locality, still provides positive evidence of the ancient GTR. One of the two kos minars at Manhala has recently disappeared. The other is also not safe as it has a big hole whereby it could collapse without the slightest malevolent human interference.

From Manhala of Khan-i-Khana, the road used to go to Brahmanabad where an interesting baoli with a small pavilion is now in very poor state and will soon be filled in if no remedial action is taken. From here, the road goes to Mahfuzpura Cantonment where an elegant baoli with a double-ringed well and an imposing two-story domed pavilion has given the site its present name of Baoli Camp. It has been recently repaired by army personnel. Then the road goes to Shahu Garhi where the best-preserved kos minar near the railway line is being encroached upon by modern dwellings. Shahu Garhi is only a few minutes away from Chowk Dara Shikoh and then to the Delhi Gate for entry into the Walled City of Lahore. Here just beside the gate was Sarai Wazir Khan next to a grand public hamam also built by Wazir Khan.

Retracing our steps to mainland India, from Sarai Amanat Khan there was a shorter route which bypassed Lahore and directly reached Eminabad passing through Amritsar in India and Pull Shah Daula in Pakistan. At the latter site we have one of the best-preserved of all Mughal period bridges. This bridge was built on Nala Dek by the famous saint, Shah Jahan. We shall come back to this bridge later.

The Walled City of Lahore marked the starting point of three routes: the road to Delhi and Agra from Delhi Gate on the eastern side, the road to Multan to the south side from the Lahori Gate, and the road to Peshawar from the north side through the Khizri or Kashmiri Gate.

The ancient route to Multan has not so far been studied properly. A hurried survey by the author brought to light a number of remains of ancient sarai along this road, one each at Sarai Chheamba, Sarai Mughal, Sarai Harappa, Sarai Siddhu, and Sarai Khatti Chaur-the last named sarai is different from the rabat at the same site as mentioned above. The Mughal-period sarai at this site was partially excavated by the author during the conservation of the Mughal-period mosque which is probably part of the sarai.

The present study is confined to the GTR going towards the north. For this purpose, the ferry passage over the River Ravi was from the Khizri Gate over to Shahdara-the King's way to Lahore. The precise course of the ancient GTR between Shahdara and Gujranwala is not clear at all points, but it was certainly a little north of the present course. At Shahdara, we have the best-preserved sarais in all Pakistan. Originally built during the Suri period as its mosque still testifies, the present edifice with its three magnificent gateways dates back to Shah Jahan's period. As it was sandwiched between two great monuments -- the Mausoleum-garden ofJahangir and the Mausoleum-garden of Asif Khan -- it served both and hence was saved for posterity.

From Shahdara, the road moves northward passing through Rana Town where, until they were both filled in in 1987, there were two baolis next to the present GTR. From Rana Town, it takes a turn to cross Nullah Deg at Bahmanwali/Chak 46. The crossing is still marked by an ancient bridge and the ruins of a sarai nearby. From here it went straight to Sarai Shaikhan (also called Pukhta Sarai), where a magnificent paneled gateway and an ancient well stand in ruinous condition. From Sarai Shaikhan the road goes to Tapiala Dost Muhammad via Kot Bashir (Chhaoni site and a baoli) to Dera Kharaba (baoli), Tapiala Dost Muhammad (mausoleum) for the onward journey to Pull Shah Daula with an ancient bridge on Nallah Deg, and monuments at Baba Jamna. It continues on to Gunaur, Wahndoki (ancient mound), and Eminabad, where a number of monuments-ancient bridge, baoli, mosque, and tank-give the area some sanctity. Finally, it reaches Kachi Sarai at Gujranwala.88 This sarai, built of mud brick in the characteristic Suri fashion, was intact until about half a century ago. Today, it has totally vanished, leaving behind its central mosque. The baoli of the sarai has also been filled in. The huge vacant area nearby for army encampments (parao) has also been covered with modern constructions. From Eminabad to Gujranwala, I examined a few baolis and a portion of the ancient GTR, with brick-paved berms during my survey in 1987. From Gujranwala, it passes through Gakkhar Gheema, Dhaunkal (baoli, ancient mosque), and Wazirbad (dak-chowki), crosses Nullah Palkhow and the River Chenab, and reaches Gujrat. The dak-chowki at Wazirbad has recently been repaired by the author, but the Akbar-period fort and baoli and a public hamam inside the fort at Gujrat, are seriously threatened. Gujrat was an important station on the ancient GTR as it is on the present-day national highway. From here emanate four roads to Kashmir via Bhimber (where there is a sarai still today), to Lahore via Eminbad just described, and to Lahore by a loop road via Shaikhupura (with a hunting ground at Hiran Minar and an elegant baoli at Jandiala Sher Khan), Hafizabad, and then to Rasul Nagar. The fourth road goes to Peshawar via Khawaspura on Bhimber Nullah, passes through a village called Baoli Sharif (baoli), Kharian with two baolis, a British-period sarai (now partially filled in), on to Sarai Alamgir (sarai and mosque), and crosses the Jhelum River to reach Jhelum city with the Mangla Fort some miles north of it. From here the ancient road deviates a little to the south and goes to the Rohtas Fort with two baolis and an ancient mosque within the fort. Sarai Sultan with a small baoli on the opposite bank of the River Kahan is fully occupied by a modern village -- its main gate and the baoli are also endangered. Midway between Sarai Sultan and Domeli still stand the remains of a huge baoli but without a pavilion -- it is called Khoji baoli.

From Sarai Sultan to Sar Jalal or Jalal Khurd, the path of the ancient road is not clear. It certainly passed through Khojki (baoli) and Domeli where there are hot water springs and another baoli (reported) nearby. But where did the ancient road cross the hot water springs mountain? We are not sure. In historical accounts, at least four stations have been mentioned, namely Rohtas Khurd, Saeed Khan, Naurangabad, and Chokuha between Rohtas and Jalal Khurd. Rohtas Khurd may correspond to Sultan Sarai, but identification of the others remains uncertain. At Jalal Khurd (modern Sar Jalal) we come across the ruins of a sarai (?), an ancient pakka tank, and a T ughlaq-period mosque. From here, the ancient road led to Rewat passing on the way through Dhamyak (grave of Sultan Muhammad Ghori), Hattiya, Mahsa, and Pakka Sarai off Gujar Khan. The Pakka Sarai has survived on the high bank of a hilly torrent.89 It has a well and two mosques inside it and a small baoli outside. At Kallar Sayyidan too, two bao/is have been reported. From here the road reaches Rewat Fort which actually marks the site of a preMughal Sarai with a grand mosque inside it. At Rewat, the modern GTR joins up with the ancient road again.

The course of the ancient road from Rewat to Sarai Kharbuza, once again, is not clear. We once had two square stone bao/is within the fork of the Islamabad-Rawalpindi Road near Rewat, now filled in, and that is all. There are usually two stations in European accounts, namely Lashkari and Rawalpindi. The ancient road probably bypassed presentday Rawalpindi to the north and went straight first to the Pharwala fort and then across the Soan River to Golra Sharif. Two kos minars once stood near Golra railway station. These are still on the record of the Department of Archaeology as protected monuments but are there no more. Onward at Sarai Kharbuza near Tarnol and Sangjani we meet the remains of a saraiwith a baoli and mosque inside it.90 From Sarai Kharbuza, an off-shoot of the GTR went north through Shah Allah Ditta over the mountain to Kainthala for the onward journey to Dhamtaur near Abbotabad as a short cut to Kashmir. At Kainthala we still have a baoli with fresh drinking water and the remains of an ancient road and an ancient site called Rajdhani, a seat of government.

From Sarai Kharbuza, the main GTR goes to Margala Pass where the modern GTR meets it and Attock. At the Margala Pass and under the shadow of the towering Nicholson monument, we still have a considerable stretch of stone-paved road with a Persian inscription from the period of the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir (1658-1705). The stone slab has now been removed and preserved in the Lahore Fort. The historic Giri Fort is not far from the Margalla Pass. From Margalla, the modern GTR joins the ancient one at least as far as Hasanabdal. On the way there are the dilapidated remains of a sarai at Sarai Kala of which only the gateway and mosque remain. At Sarai Kala we meet the remains of an ancient bridge on Kalapani. From this bridge onward, the alignment of the ancient road is marked by the magnificent Laoser Baoli within the Wah Cantonment, the remains of the beautiful Wah Gardens with a Farood Gah-i-Shahinshah-i-Mughalia -- that is to say, the Resting Place of the Mughal Emperors built by Jahangir (1605-1628)-and then another square sarai at Hasanabdal with a sacred tank and two mausoleums. From Hasanabdal onward the road goes to Burhan where once stood to be Sarai Zainud Din Ali (not yet located), to Hattian (Saidan Baoli), to Kamra (Chitti Baoli), Behram Baradari (small walled garden), Begum-ki-Sarai (sarai, mosque, and a square kos minar), and finally Attock where there is still an impressive fort from the Akbar period (1556-1605) with a Persian inscription and an ancient well, a baoli on the bank of Dakhnir Nullah south of Rumain, and the pillars of a boat-bridge from the Akbar period on the Indus River.

Beyond Attock, the ancient road probably used to run northward as does the modern GTR, although the path of the ancient GTR between Attock and Peshawar is not very clear. Very few historical landmarks have so far been recorded between these two historic cities. I know of only one ancient stepped well or baoli just beside the modern GTR near Aza Khe! Payan (Pir Payai railway station), between Nowsherhra and Peshawar. Khushhal Khan Khattack's garden-pavilion at Vallai near Akora Khattack was also probably not far from the path of the ancient GTR. Otherwise, a few more baolis have recently been located between Peshawar and Attock by a team from Peshawar University but they are mostly modern. No report has so far been published. The only definite landmark in this region is the famous Sarai Jahan Aura Begum at Peshawar built by Princess Jahan Aura, daughter of Shah Jahan (1627- 1658), who after the death of her mother became the First Lady of the Empire. Her sarai is popularly known as Gop Khatri as it was built on top of an ancient site of the same name which dated from the second century B.C. The gateway to this sarai is currently being repaired. Very few original cells have been preserved. Qila Bala Hisar in the same city also provides a landmark and fixes a point on the GTR for the onward journey to Kabul. Beyond that point, there are only three more landmarks: Jamrud (Fort), Ali Masjid (famous for its Buddhist Stupa), and Landikotal (Shapoola Stupa). Whether there are remains of any sarai, baoli, kos minar, or dak-chowki between Peshawar and Jalalabad, I am not sure. No published information is available, but the author is hopeful that a survey may reveal some interesting information.

This section is a brief account of the ancient course of the Grand Trunk Road (and its halting stations) which has marked the history of the whole of Northern India as it is today. Along this road marched not only the mighty armies of conquerors, but also the caravans of traders, scholars, artists, and common folk. Together with people, moved ideas, languages, customs, and cultures, not just in one, but in both directions. At different meeting places -- permanent as well as temporary -- people of different origins and from different cultural backgrounds, professing different faiths and creeds, eating different food, wearing different clothes, and speaking different languages and dialects would meet one another peacefully. They would understand one another's food, dress, manners and etiquette, and even borrow words, phrases, idioms and, at times, whole languages from others. As a result of this exchange of people and ideas along this ancient road and in its caravanserais, beside the cooling waters of the stepped wells and in the cool shade of their pavilions, waiting at the crossroads and under the shadows of the mighty kos minars, the seeds of new ways of life, new cultures, and new peoples took root. This was the role of this mighty highway that connected Central Asia with the subcontinent of Pakistan and India. The devastation wrought by invading armies has been forgotten. Merchandise bought and sold has been lost. But the seeds of cultural exchange sown along this road have taken root and given shape to new cultural phenomena that have determined the course of life today along these routes. Here lies the value of the ancient Grand Trunk Road and the halting stations on it.

_______________

Notes:

1. K.M. Sarkar, The Grand Trunk Road in the Punjab: 1849-1886 (Lahore: Punjab Government Record Office Publications, 1926), p. 8, (Monograph No. I).

2. John Wiles, The Grand Trunk Road in the Punjab: Kyber to Calcutta (London: 1972), pp. 7-16. Rudyard Kipling, as quoted by Wiles (p. 8), described this road as a mighty way "bearing, without crowding India's traffic for 1,500 miles such a River of life as nowhere else exists in the world. "

3. Sir James Douie, North West Frontier Province, Punjab and Kashimir, p. 126, see Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 7.

4. H.L.O. Garret in Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, Prefatory Note.

5. John Wiles, Grand Trunk Road, p. 7.

6. The part of the Silk Road which passed through Pakistan corresponds to the Grand Trunk Road from Peshawar to Lahore. However, at Lahore, instead of going straight to Delhi, it bent southward and, while embracing the present-day National Highway, it used to terminate at Barbaricon near Karachi and joined the Sea Route. Alexander the Great also followed the same road up to the River Beas. Later invaders, almost without exception, followed the same road to reach the coveted throne of Delhi.

7. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, pp. 7-8.

8. See Preface by VS. Agrawala in Moti Chandra, Trade and Routes in Ancient India (New Delhi, 1977), p. vi.

9. Ibid., p. 78; Also see R.P. Kangle, The Kantiliya's Arthasastra, reprinted with Urdu translation by Shan-ul-Haq Haqqi, and Muqadama by Muhammad Ismail (Zabeeh Karachi, 1991), bk. 4, sec. 116, pp. 17-26 (Hamavata Path), and bk. 2. See 22.31 for width of roads.

10. Kangle, Kantiliya's Arthasastra, bk. 2, sec. 19.19 and 38.

11. Ibid., sec. 22, pp. 1-3. Asthaniya was located at the center of800 villages, whereas a dronamukha was at the center of 400 villages (sec. 19.

12. It was on account of and along this Royal Road that Megasthenes could travel to lands never before beheld by Greek eyes. It was maintained by a Board of Works (See Megasthenes' Indika, Fragments 3, 4 and 34, in J.W McCrindle, Ancient India as described by Megasthenes and Arrian (London, 1877), pp. 50, 86. XV I. II. According to Megasthenes, this Royal Road was measured by scheoni (1 scheonus = 40 stadia = one Indian yojana = 4 krosas or kos) and its total length was 10,000 stadia, i.e., about 1,000 koso He also states that there was an authoritative register of the stages on the Royal Road from which Erastothenes derived his estimates of distances between various places in India.

13. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 2.

14. Megasthenes' Indika. Ten stadia are usually regarded as equal to 2,022.5 yards or one kos of 4,000 haths--according to some, 8,000 haths. These pillars were meant to show the by-roads and distances. There is great difference of opinion as to what the correct measure of one kos or krosa is-some regard it as less than 3 miles while others regard it as equal to 1.75 miles (2.8 kilometers). Traditionally and within our own memory, a koswas about 2.5 English miles (4 kilometers). For details see Radha Kumud Mookerjee Asoka, 3d ed. (Delhi, 1962), p. 188 wherein he regards 8 kosas equal to 14 miles i.e., I kos = 1.75 miles. Also see Moti Chandra, Trade and Trade Routes in Ancient India (New Delhi, 1977), p. 78.

15. Kangle, The Kautiliya Arthashastra, bk. 2, sec. 56.5.

16. "On the high roads, too, banyan trees were caused to be planted by me that they might give shade to cattle and men, mango-gardens (amba-vadikya) were caused to be planted and wells to be dug by me, at each half kos (adhakosikyam) nimisdhaya were caused to be built, many watering stations (aparani) were caused to be established by me, here and there, for the comfort of cattle and men." See the Seven Pillar Edicts, part 7, as on Dehli-Topra Pillar in Radha Kumud Mookerji, Asoka, pp. 186-93. Also see Dr. R. Bhandarkar, Asoka, 2d ed. (Calcutta, 1932), p. 353.

17. "Nimisdhaya" (Skt. nisdya) has often been translated as "rest-house." Luder, however, translates it as "Steps down to water." Hultzseh also follows Luder. But Woolner and some others do not accept this meaning and are probably right. See also discussion on this word in E. Hultzseh, Corpus Inscription Indicarum, vol. I.

18. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 2.

19. Mookerji, Asoka, p. 189, note 3.

20. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. ix. He talks about wells and trees but not the "rest houses" built by Asoka, p. 79. He probably agrees with Luder as regards the meaning of "nimisdhaya" as "stepped well," i.e., baoli.

21. V.S. Agrawala, suggests that, as Kangs were the originators of a canal system in Central Asia in the seventh centuty B.C., Sakas (Scythians) from the same region introduced stepped wells or baolis in the second century B. C.

22. B. Rowland, Art in Ajghanistan. Objects from the Kabul Museum (London: Allen Lane the Penguin Press, 1971), p. 21.

23. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. 19.

24. Saifur Rahman Dar, "The Silk Road and Buddhism in Pakistani Contexts," Lahore Museum Bulletin, vol. I, no. 2 (July-December 1988): pp. 29-53.

25. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. 84. The silence of these travelers about these facilities can be easily explained. As devout Buddhists, they always preferred to stay in Buddhist monasteries which were numerous in those days. Their doors were always open to travelers-pious and lay alike.

26. Muhammad Qasim Farishta, Tarikh-i-Farishta, trans. Abdul Hayee Khawaja (Lahore, 1974), pan I, p. 136. See also MaulanaAbdul Salam Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, Darul Musanafeen, series no. 93 (Azim Garh: n.a.), p. 40. In Briggs' translation of Farishta's history, however, there is no mention of a sarai on the DelhiDaulatabad toad or elsewhere. Instead, Muhammad Tughlaq is reported to have planted shady trees in rows along this road to provide travelers with shade, while poor travelers were fed on this road at public expense. He is also said to have established hospitals for the sick and almshouses for widows and orphans; see Muhammad Qasim Farishta, History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India till the Year 1612, English translation by John Briggs, 4 volumes (1829; reprint Delhi: Low Price Publications, 1990), vol. I, pp. 236 and 242.

27. Shams Siraj Afeef, Tarikh-i-Feroze Shahi, Urdu trans. by Maulvi Muhammad Fida Ali Talib (Karachi: Nafees Academy, 1%5), p. 23. See also R. Nath, History of Sultanate Architecture (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1978), p. 59. From Muhammad Qasim Farishta we learn that Firoze Tughlaq not only repaired the caravanserais built by his predecessors but also built 100 sarais of his own; see Muhammad Qasim Farishta, History of the Rise of the Mohamedan Power in India, vol. 1, pp. 267-70. He also built several other public amenities such as dams, bridges, reservoirs, public wells, public baths and monumental pillars. He set aside lands for the maintenance of these public buildings.

28. Abdul Salam Nadvi, Rafi-i-Ama ke kam, p. 40 quotes Mirat-i-Sikandari, p. 75, for this information.

29. Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, p. 40. Also Qasim Farishta, History of the Rise of the Mohamedan Power in India, vol. 1, p. 186.

30. Abbas Khan Serwani, "Tarikh-i-Sher Shah" in History of India as told by its Historians, edited by H.M. Elliot and John Dowson, vol. 4 (London, 1872), pp. 417-18. See also Rizqullah Mushtaki, Waqiat-i-Mushtaki, in the same volume; Zulfiqar Ali Khan, Sher Shah Suri: Emperor of India (Lahore, 1925); and Hashim Ali Khan (alias Khaft Khan), Mutakhabut-Tawarikh, Urdu translation by Muhmud Ahmad Faruqui, vol. 1 (Karachi: Nafees Academy, 1963), pp. 127-28. The more important roads include the Grand Trunk Road from Sonargaon to the Nilab (Indus River) and those from Lahore to Multan via Harappa and from Agra to Mandu. On the Multan-Lahore Road, there still exist two sarais, namely Sarai Chheemba close to Bhai Pheru (Phul Nagar) and Sarai Mughal near Baloki Headworks. Another Pakka Sarai attributed to Sher Shah Suti was standing as late as 1964, almost in front of the present-day Harappa Museum. A considerable length of an ancient road, still shaded by old trees and called Safon Wali Sarrak, extends on either side of this sarai. This sarai has now been excavated and reported briefly. See Richard H. Meadow and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Harappa, 1994-95: Reprints of Reports of the Harappa Archaeological Research Project (December 1995), sec.: "Harappa Excavation 1994," p. 13, fig. 13. Though usually these sarais are attributed to Sher Shah Suri, on the authority of the author of Miasrul Umara, we learn that Khan Dautan Nusrat Jang and Qaleej Khan Torani built several sarais on the road from Lahore to Multan (see note 40 below). Another road linked Lahore with Khushab and onward to the Kurram Valley on the way to Afghanistan. Two beautiful baolis or stepped wells still exist on this road, one each at Gunjial near Quaid Abad and Van Bachran near Mianwali; both are attributed to Sher Shah Suri. See Saifur Rahman Dar, "Khushab-Monuments and Antiquities," Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, vol. 15, no. 3, part 2 (Lahore, August 1978). There are three interesting baolis in the picturesque Son Valley marking some ancient routes linking Khushab with the Salt Range.

31. Shaikh Rizqullah Mushtaki, "Wakiat-i-Mushtaki," in Elliot and Dowson, History of India, vol. 4, appendix G, p. 550.

32. Elliot and Dowson, History of India, p. 417, footnote 2. This figure occurs in one of the manuscripts of Serwani, whereas Sher Shah is reported as having constructed 2,500 rather than 1,700 sarais. This they attribute to ignorance on two fronts, namely that the total distance between Bengal and the Indus is 2,500 kos, and there was a sarai at each instead of every second koso This tradition can be considered as partly true if it refers to the reign of Salim Shah Suri (A.D. 1545-1552), who is said to have added one more sarai between every two sarais built by his father. Shaikh Rizqullah Mushtaki, "Wakiat-i-Mushtaki," appendix G, p. 550, also puts Suri sarais after one rather than two koso See also Farishta, Tarikh-i-Farishta, vol. I, p. 228, as quoted by Maulana Abdul Salam Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, p. 41.

33. Nadvi, Rafo-i-Ama ke kam, p. 41. Also Qasim Farishta, Tarikh-i-Farishta, vol. 1, p. 332; and Khaft Khan, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab, translated by Muhammad Ahmad Faruqi (Karachi: Nafees Academy, 1963), part 1, p. 135.

34. Dr. M.A. Chaghatai, Tarikhi Masajid-i-Lahore (Lahore, 1976), pp. 29-31.

35. Abul Fazl, Ain-i-Akhbari, vol. 1, p. 115. Among such philanthropists were the widow of Shaikh Abdul Rahim Lukhnavi and Sadiq Muhammad Khan Harvi, who built sarais at Lukhnau and Dhaulpur respectively.

36. The Tuzk-i-Jahangiri or Memoirs of Jahangir, translated by Alexander Rogers, edited by Henry Beveridge (Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 1974), vol. 1, pp. 7-8, 75, and vol. 2, pp. 63-64, 98, 103, 220, 249; see also Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 49.

37. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 43. Also see Tuzk-i-Jahangiri (Lahore: Nawal Kishore Press, n.d.), p. 5. Such courtiers include Halal Khan, Khawajasara, Saeed Khan Chagatta, the Subedar of Punjab, Shaikh Farid Murtaza Khan Bokhari, and Arnir Ullah Vardi Khan. See Samsamud Daula Shahnawaz Khan, Ma'asrul Umara, Urdu translation by Muhammad Ayub Qadri (Lahore: Urdu Markzi Board, 1%8), pp. 205,407,408,639 under names quoted here: vol. I, p. 205 (Amir Ullah); p. 407 (Halal Khan); vol. 2, p. 408 (Saeed Khan Chagatta); and p. 639 (Farid Murtaza Khan Bukhari). Sarais were built along the roadside whereas rabats were located inside the cities.

38. Rogers and Beveridge, Tuzk-i-jahangiri, p. 77 (Azim Khan). Beside sarais, Jahangir also ordered the preparation of bulghur-khana (free eating houses) where cooked food was served both ro the poor residents as well as travelers; see also A. Rogers and H. Beveridge, Tuzk-i-Jahangiri, vol. 1, p. 75.

39. Ibid, p. 406 and Khafi Khan, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab, p. 302. Jahangir also mentions the existence of several other sarais in his empire, mostly in the Punjab such as Sarai Qazi Ali near Sultanpur, Sarai Pakka near Rewat, Sarai Kharbuza near Tarnaul (also marked on Elphinston's map), Sarai Bara, Sarai Halalabad, Sarai Nur (Mahal) near Sirhind, Sarai Alwatur or Aluwa, and a grand baoli built by his mother at a cost of Rs. 20,000 at Barah. See Rogers and Beveridge, Tuzk-i-Jahangir, vol. 1, pp. 63, 98, and vol. 2, pp. 64, 103, 219, 220,2 49.

40. For example, Azim Khan built a sarai in Islamabad (Mathura) whereas Khan Dauran Nusrat Jang and Qaleeg Khan Torani built sarais every 10 kos on the road from Suraj to Burhanpur and several sarais on the road from Lahore to Multan respectively. See Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. I, p. 179 (Azim Khan), p. 758. See too previous note.

41. Tariq Masud, "Pull Shah Daula," Lahore Museum Bulletin, vol. 3, no. 2 (July-December 1990).

42. Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 44

43. Shaista Khan, the Emir Umara of Aurangzeb, also built several rabats, mosques and bridges (Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 2, p. 705).

44. Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 44.

45. Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 1, p. 358.

46. Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 3, p. 882. Also see Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 45.

47. Kahn, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 1, p. 358, and Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, pp. 44-45.

48. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. vii.

49. William Foster, ed., Early Travels in India, 1583-1619 (London, 1921; Lahore, 1978), pp. 167-68.

50. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, chap. 3-4, pp. 13-45.

51. Moti Chandra, Trade, p. 81, and Abul Fazl, Ain-i-Akbari, vol. 1 (Nawal Kishore Edition), p. 197 (under Ain-i-Kotwal).

52. Shaikh Rizqullah Mushtaki, "Wakiat-i-Mushtaki," in Elliot and Dowson, History of India, vol. 4, appendix G, p. 550; Ishwari Prasad, The Life and Times of Humayun (Bombay: Oriental Longmans, 1955), pp. 168-69; and Dr. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri (Lahore: Ferozsons Ltd., 1987), pp. 332-40. Also see note 32 above.

53. Dr. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri, p. 333.

54. Arthur Upham Pope, Persian Architecture: The Triumph of Form and Colour (New York: George Braziller, 1965), p. 238.

55. Khan, Ma'asrul Umara, vol. 2, p. 639 (see Farid Murtaza Khan Bukhari).

56. Nadvi, Rafa-i-Ama ke kam, p. 45.

57. Dr. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri, p. 333.

58. Ebba Koch, Mughal Architecture: An Outline of Its History and Development (1576- 1858) (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1991), p. 67, fig. 65.

59. Catherine B. Asher, "Architecture of Mughal India," in The New Cambridge History of India, vol. 14 (Cambridge, 1992), p. 225.

60. Rogers and Beveridge, Tuzk-i-Jahangiri, vol. 2, p. 182.

61. Subash Parihar, "Two Little-known Mughal Monuments at Fatehbad in East Punjab," Journal of Research Society of Pakistan, vol. 38, no. 2 (Lahore) (April 1991): pp. 57- 62.

62. Subash Parihar, "The Mughal Sarai at Doraha-Architectural Study," East and West, vol. 37 (Rome, December 1987): pp. 309-25.

63. Nur Ahmad Chishti, Tehqiqat-i-Chishti (Lahore: Al-Faisal Printers, 1993), pp. 764-66.

64. Arthur Upham Pope, Persian Architecture, p. 238.

65. Ebba Koch, Mughal Architecture, p. 238.

66. Indian Archaeology, 1980-81, A review (1983): p. 67.

67. There is some controversy as regards the vaulted roof structure in the courtyard of Begum-ki-Sarai. For some it is a mosque, while for others it is not. On either side of the double row of chambers, there are two open platforms, both accessible from within the chamber. Thus, in the western wall, there are three openings in place of a mehrab. This has led some to believe that this structure is a baradari or pavilion rather than a mosque. See Lt. Col. K.A. Rashid, "An Old Serai Near Arrock Fort," reprinted from Pakistan Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 3 (Summer 1964): Plate 4. Bur this is certainly not true. In such deserted places, such as at Begum-ki-Sarai, a mosque was a must. The platform to the west of the Prayer Chamber and three openings in the western walls appear to have been a British-period innovation. Misuse of mosques by British residents for some mundane purpose is not an unknown phenomenon. The use of the famous Dai Anga Mosque, Lahore, as a residence by Mr. Henry Cope, and use of the verandahs of the Badshahi Mosque, Lahore, as a residence for British soldiers, are well-known examples.

68. Lt. Col. K.A. Rashid, "The Inscriptions of Begum Sarai (Arrock)," Journal of Research Society of Pakistan, vol. 1 (Lahore, October 1964): pp. 15-24.

69. Epigraphica India (1953 and 1954), pp. 44-45.

70. Wayne E. Begley, "Four Mughal Caravanserais Built During the Reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan," Muqarnas, vol. 1 (1983): p. 173.

71. Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments in the Punjab and Haryana (New Delhi: Inter-India Publications, 1985), p. 19.

72. Bahadur Khan, "Mughal Garden Wah," Journal of Central Asia, vol. 11, no. 2 (December 1988): p. 154, illust. p. 158.

73. "Tarikh-i-Sher Shah," in Elliot and Dowson, The History of India, p. 140.

74. Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 48-49.

75. Memoirs of Emperor Jahangir, trans. by Major David Price (Delhi, n.d.), p. 157.

76. Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments, p. 19 and Sarkar, Grand Trunk Road, p. 48-49.

77. Akbar Nama, vol. 3, p. 378, as quoted by Manzul Haque Siddiqui, Tarikh-i-Hasan Abdal (Lahore), pp. 64-65.

78. Manzar-ul-Haque Siddiqui, Tarikhai-i-Hasan Abdal, p. 65.

79. William Foster, ed., Early Travels, p. 255 and footnote.

80. R.C. Temple, ed., The Travels of Peter Mundy, vol. 2 (London: Hakluyt Society, 1914), p. 121; as quoted by William Foster, Early Travels, p. 225 (footnote).

81. Hussain Khan, Sher Shah Suri, p. 33, and Khafi Khan, Muntakhab-ul-Lubab, vol. I, p.127.

82. R.P. Kangle, Kautiliya Arthashatra, bk. 2. sec. 56, paras. 5-6.

83. Catherine B. Asher, Architecture of Mughal India, p. 225.

84. Foster, Early Travels, p. 225, and Temple, ed., The Travels of Peter Mundy, vol. 2.

85. Foster, Early Travels, pp. 155-60, and Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments, pp. 19- 26 (footnote 16).

86. Subash Parihar, Mughal Monuments, pp. 19-26. Hugel clearly refers to the road Filor-Nakodar-Sooltanpur-Fatehbad-Noorooddeen Suraee (near Taran Taran), Khyroodden Suraee (near Rajah Ku) -- Manihala-Taihar (baoli nearby) -- Lahore as the "old Badshahee Road." See Baron Charles Hugel, Travels in Kashmir and the Punjab (1845; reprint Lahore: Qausain, 1976), Pocket Map.

87. Waheed Quraishi, "Gujranwala: Past and Present," Oriental College Magazine (Lahore, February-May 1958), p. 20. The first to mention this sarai in 1608 was William Finch under the name "Coojes Sarai." Present-day Gujranwala city actually encompasses the sites of the three ancient sarais and a settlement namely Sarai Kacha, Sarai Kamboh, Sarai Gujran, and a village called Thatta; see Waheed Quraishi, p. 21.

88. In 1607, Jahangir visited this sarai and described the site as "strangely full of dust and earth. The carts reached it with great difficulty owing to the badness of the road. They had brought from Kabul to this place riwaj (rhubarb), which was mostly spoiled" (Tuzk-i-Jahangiri, translated by A. Rogers, vol. 1, p. 99).

89. Sarai Kharbuza is marked on Elphinston's map. Jahangir visited it in 1607 and described it in these words: "On Monday the 10th, the village of Kharbuza was our stage. The Ghakhars in earlier times had built a dome here and taken a toll from travellers. As the dome is shaped like a melon it became known by that name" (Tuzk-i- Jahangiri, translated by A. Rogers, vol. 1, p. 98).

Staircases

At the main gateways, staircases of two stories were usually provided on either side. Usually staircases were also provided at one or both sides of the special rooms (Khanaha-i-Padshah) or the corner bastions such as at Pakka Sarai and Begum-ki-Sarai.

Parapets

Parapets were usually in the form of medium-sized battlements such as in Begum-ki-Sarai or Sarai Rewat. The merions in the case of Rewat give it the appearance of a fortress. But at other places, such as Sarai Kharbuza and Sarai Pakka, the parapets are simple and plain.

Inscriptions

No proper inscription has been found in any of the surviving sarais in Pakistan. Only some scribbling belonging to different periods has been reported from Begum-ki-Sarai at Attock.69 Outside Pakistan, two Persian inscriptions are known from Sarai Ekdilbad, near Etawa, commemorating the simultaneous construction of a mauza (villageltown), a sarai, and a garden by Shah Jahan.70 Sarai Amanat Khan, built in 1640-1641 by Ahmanat Khan himself, the famous calligrapher of the Taj Mahal, also bears a dedicatory inscription on the west gate71 Sarai Nur Mahal near Phillour (East Punjab, India), the most impressive of all sarais in the Punjab built by Empress Nur Jahan, also bears a dedicatory inscription with two dates A.H. 1028 (A.D. 1618) and A.H. 1030 (A.D. 1620).72

Hamams

Turkish hamams of the Roman thermae type were a speciality of the Mughals and were introduced by them into the subcontinent. Their palaces (Lahore Fort), gardens (Shalamar, Lahore, and Wah Gardens at Hasanabdal), and even some of their sarais (Sarai Itamadud Daula at Doraha), were provided with elaborate hamams. It was Jahangir (A.D. 1605-1628) who introduced hamam into sarais. This practice was continued by others. In none of the sarais in Pakistan is such a hamam known to have survived. However, we have a beautiful and colossal public hamam, attached to, though structurally detached from, Sarai Wazir Khan, inside Delhi Gate, Lahore. It has now been renovated. Wah Gardens, a place officially known as Farood Gah-i-Shahinshah-i-Mughalia or the Resting Place of the Mughal Emperors and therefore to be considered as a category of sarai or temporary residence, has an elaborate hamam of which only the foundations have survived.73

Distances

There is some confusion as regards the exact distance between two sarais, baolis, and kos minars of the Mughal period. The difficulty is due to the conversion of a kos or krohlkrosa into English miles. The former appears to have been measured differently at various times. We know from Sarwani that Sher Shah built his sarais at a distance of two kos.74 His son Salim Shah added one more sarai in between every two built by his father. Thus making the distance between two sarais equal to one koso Sarkar, on the other hand, states that Suri sarais were situated 10 kos apart75 whereas sarais of Jahangir's period according to his own decree were 8 kos apart on the road from Agra to Lahore?6 Following this, the East India Company established Dak bungalows on the highways at 10 mile intervals.77 But, on the other hand, we know from Akbar Nama that the distance between Sarai Hasanabdal and Sarai Zainuddin Ali on the way to Attock was 4.25 kroh and 5 mans (app. 5 krohs as usually accepted) which is usually estimated to equal 10.5 English miles.78 Now, the Akbari kroh has been estimated to equal 5,000 ilahi gaz (of 30" length) or 4,250 English yards.79 As the distance between Peshawar and Lahore is about 264 miles, there must have been at least 26 sarais between these two stations, of which 20 can easily be recognized or presumed to have existed.

Attendants