An Altar of Alexander Now Standing at Delhi [EXPANDED VERSION]

by Ranajit Pal

Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute,

Pune, India.

January, 2006

© University of Otago, 2006

That the history of Asoka matches that of Diodotus I line by line can only imply that they were one and the same person....

The Parthian Prince An-shih-kao, who dedicated his life to the spread of Buddhism, is clearly Diodotus...

Asoka does not refer to Diodotus because he was Diodotus himself...

Historians have denied Diodotus his true place in world history.

-- An Altar of Alexander Now Standing at Delhi [EXPANDED VERSION], by Ranajit Pal

Diodotus was born between 315-300 BC, likely to parents established as nobles in Bactria. His father (also Diodotus) was believed to have been a dignitary and Diadochi of Alexander the Great, awarded land in Bactria.

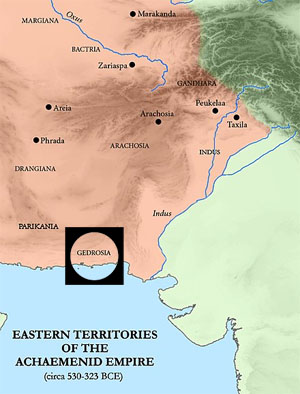

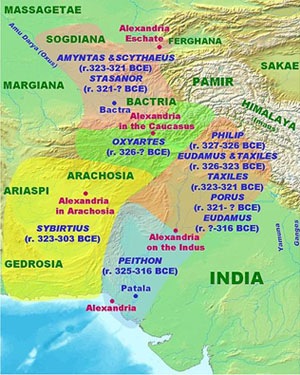

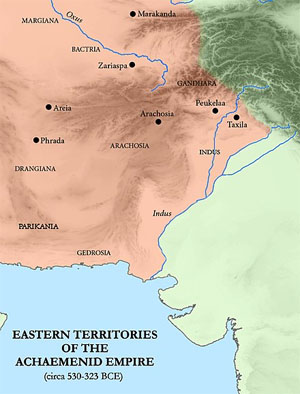

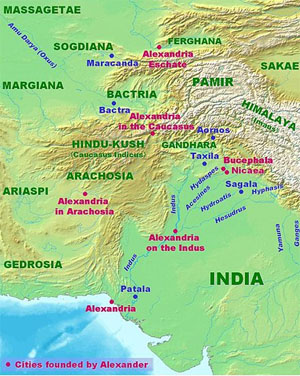

The region of Bactria, which encompassed the Oxus river Valley in modern Afghanistan and Tajikistan, was conquered by Alexander between 329 and 327 BC and he settled a number of his veterans in the region. In the wars which followed Alexander's death in 323 BC, the region was largely left to its own devices, but it was incorporated in the Seleucid empire by Seleucus I between 308 and 305 BC, along with the rest of the territories that Alexander had conquered in Iran and Central Asia. Seleucus entrusted the region to his son and co-regent, Antiochus I, around 295 BC. Between 295 and 281 BC, Antiochus I established firm Seleucid control over the region. The region was divided into a number of satrapies (provinces), of which Bactria was one. Antiochus founded or refounded a number of cities on the Greek model in the region and he opened a number of mints to produce coinage on the Attic weight standard. After Antiochus I succeeded his father as ruler of the Seleucid empire in 281 BC, he entrusted the east to his own son, Antiochus II who remained in this position until he in turn succeeded to the throne in 261 BC.[8]

Diodotus became Seleucid satrap (governor) of Bactria during Antiochus II's reign, thus about a generation after the original establishment of Seleucid control over the region .... Archaeological evidence for the period comes largely from excavations of the city of Ai-Khanoum, where this period saw the expansion of irrigation networks, the construction and expansion of civic buildings, and some military activity...

At some point, Diodotus seceded from the Seleucid empire, establishing his realm as an independent kingdom, known in modern scholarship as the Graeco-Bactrian kingdom. The event is mentioned briefly by the Roman historian Justin:Diodotus, the governor of the thousand cities of Bactria, defected and proclaimed himself king; all the other people of the Orient followed his example and seceded from the Macedonians [i.e. the Seleucids].

— Justin Epitome of Pompeius Trogus 41.4...

The limited archaeological evidence reveals no signs of discontinuity or destruction in this period. The transition from Seleucid rule to independence thus seems to have been accomplished peacefully....

The literary sources stress the prosperity of the new kingdom. Justin calls it "the extremely prosperous empire of the thousand cities of Bactria.", while the geographer Strabo says:The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander... Their cities were Bactra (also called Zariaspa, through which flows a river bearing the same name and emptying into the Oxus), and Darapsa, and several others.

— Strabo Geography 11.11.1

[A]rchaeological evidence makes clear that goods and people continued to move between Bactria and the Seleucid realm.

Diodotus died during the reign of Seleucus II, sometime around 235 BC, probably of natural causes. He was succeeded by his son Diodotus II. The new king concluded a peace with the Parthians and supported Arsaces when Seleucus II attacked him around 228 BC. Diodotus II was subsequently killed by an usurper, Euthydemus [a Greco-Bactrian king], who founded the Euthydemid dynasty....

Diodotus appears also on coins struck in his memory by the later Graeco-Bactrian kings Agathocles and Antimachus. These coins imitate the original design of the tetradrachms issued by Diodotus I, but with a legend on the obverse identifying the king as Ancient Greek: ΔΙΟΔΟΤΟΥ ΣΩΤΗΡΟΣ ('Of Diodotus Soter' [saviour]).

-- Diodotus I, by Wikipedia

In my ten months journey between Aleppo and this court, I spent just three pounds sterling, yet fared reasonably every day; victuals being so cheap in some of the countries through which I travelled, that I often lived competently for one penny a-day. Of that three pounds, I was actually cozened out of ten shillings, by certain evil Christians of the Armenian nation; so that in reality I only expended fifty shillings in all that time. I have been in a city of this country called Delee, where Alexander the Great joined battle, with Porus king of India, and defeated him; and where, in memory of his victory, he caused erect a brazen pillar, which remains there to this day. At this time I have many irons in the fire, as I am learning the Persian, Turkish, and Arabic languages, having already acquired the Italian. I have been already three months at the court of the Great Mogul, and propose, God willing, to remain here five months longer, till I have got these three languages; after which I propose to visit the river Ganges, and then to return to the court of Persia.

-- A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Arranged in Systematic Order: Forming a Complete History of the Origin and Progress of Navigation, Discovery, and Commerce, by Sea and Land, From the Earliest Ages to the Present Time, by Robert Kerry, F.R.S. & F.A.S. Edin., Illustrated by Maps and Charts, Vol. IX, 1824

Asoka’s Lat. —

The next object of interest in the palace of Firoz Shah is the pillar on which Asoka, king of Magadha, published his tolerant edicts to the world. It was put up here by Firoz Shah, in the year 757 A.H. (1356 A D.) It stands on a pyramidal building of rubble stone, with domes of rubble stone irregularly set in mortar of admirable quality, and arches with ribs. [Beglar.]

The pyramid consists of terraces standing on an exterior platform, on the top-most of which the pillar stands; these terraces have cells with arches all round. [Muhammad Anim Razi in his Haft-i-Kalim, describes the pillar, as it was in the time of Akbar, as standing on a house three-storeyed high, being “a monolith of red-stone tapering upwards.” “The three storeys,” says Franklin, “were partly a menagerie, and partly an aviary.” From where this idea was got hold of, I am unable to say.] I agree with Mr. Beglar that there was not another storey over the highest storey now in existence; the presence of two stumps of pillars near the edge of the upper-most storey does not argue, as a matter of even strong probability, that they were parts of pillar- supports, but I am of opinion, that the addition of another storey which would serve to dwarf the size of the pillar would be an ill advised addition for men who were setting up a lofty monument to the glory of their king. The fact that the domes over the four corner towers of the third storey are on a level with the present main roof, is decidedly in favour of the theory that the building was never higher than it is now. “Vertically beneath the base of the pillar, a gallery has been broken through in the top-most storey, disclosing a sort of rough chamber, covered by a rubble dome 4 feet in diameter, on which consequently, the entire weight of the pillar rests. [ Beglar.]

Asoka, king of Magadha, subsequently known as Dhammasoka, was the son of Bindusara, and grandson of Chandra Gupta, “the king of Hindusthan, from Kashmir to Kanauj.” He was born in the orthodox faith, and was a worshipper of Shiva, but became a convert to Bhuddism, and a powerful propagandist of his new faith. He commemorated his conversion and his desire that his new faith should be spread over his empire, by the promulgation of edicts which still stand as undying memorials of his faith, on granite pillars which were erected from Kabul to Orissa. Asoka is the Piyadasi of the pillar inscriptions and Pali records; the contemporary of Antiochus Theos, and his age may be placed between 325-200 B.C.

The pillar under notice is a sand-stone monolith, 42 feet 7 inches high, of which the upper portion of 35 feet is polished and the rest is left rough; the buried portion of the pillar is 4 feet 1 inch long. [Beglar.] Its upper diameter is 25-3 inches and its lower diameter 38-8 inches, the diminution being -39 inches per foot. [Cunningham.] The pillar is supposed to weigh 27 tons. The colour of the stone is pale pink, having black spots outside, something like dark quartz. The usual amount of inaccuracies has found its way in the measurements of this pillar: Major Burt, who examined it in 1837, gives its length as about 35 feet, and diameter as 3-1/4 feet; Franklin gives 50 feet as its length; Von Orlich, 42 feet; William Finch, 24 feet; Shams-i-Siraj, 24 gaz or 34 feet, and its circumference 10 feet. As regards the material of the monolith and the inscriptions it bears, some very curious mistakes have also been made: the Danish Councillor, de Laet, describes it as “a very high obelisk (as some affirm) with Greek characters and placed here (as it is believed) by Alexander the Great;" the eccentric Tom Coryat also ascribes the pillar to Alexander and describes it as “brazen;" the confiding Chaplain Edward Terry, who was so charmed with Coryat’s improbable stories, improves on his informant and calls it a "very great pillar of marble” of Alexander the Great; but strange to say, that the observant Bishop Heber describes it as a pillar of “cast metal,” and, that the description was not an ordinary slip of the pen, is evident from the fact that the Bishop refers to it, to explain the material of the Iron Pillar, both being, in his lordship’s opinion, of “cast metal."

-- Archaeology and Monumental Remains of Delhi, by Carr Stephen, 1876

Delhi is situated in a fine plain; and about two coss [3.6 miles] from thence are the ruins of a hunting seat, or mole, built by Sultan Bemsa, a great Indian sovereign [NOT "Togall Shah"]. It still contains much curious stone-work; and above all the rest is seen a stone pillar, which, after passing through three several stories, rises twenty-four feet above them all, having on the top a globe, surmounted by a crescent. It is said that this stone stands as much below in the earth as it rises above, and is placed below in water, being all one stone. Some say Naserdengady, a Patan king, wanted to take it up, but was prevented by a multitude of scorpions. It has inscriptions.6 [Purchas alleges that these inscriptions are in Greek and Hebrew; and that some affirm it was erected by Alexander the Great.—E.] In divers parts of India the like are to be seen....

From Sirhind, in five stages, making forty-eight coss [86.4 miles], I came to a serai called Fetipoor, built by the present king Shah Selim, in memory of the overthrow of his eldest son, Sultan Cussero, on the following occasion. On some disgust, Shah Selim took up arms in the life of his father Akbar, and fled into Purrop, where he kept the strong castle of Alobasse7 [Purrop, or Porub, has been formerly supposed the ancient kingdom of Porus in the Punjab, and Attobass, here called Alobasse, to have been Attock Benares. — E.] but came in and submitted about three months before his father’s death.

-- A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Arranged in Systematic Order: Forming a Complete History of the Origin and Progress of Navigation, Discovery, and Commerce, By Sea and Land, From the Earliest Ages to the Present Time, by Robert Kerr, F.R.S. & F.A.S. Edin., Vol. VIII, 1824

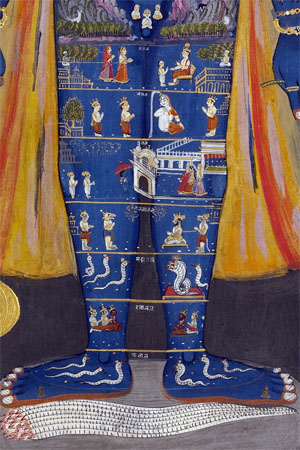

Abstract. The vanishing of the twelve magnificent altars set up by Alexander the Great has intrigued many scholars. This article shows that one of the Altars was reinscribed by Emperor ASHOKA, WHO WAS THE FAMOUS INDO-GREEK KING DIODOTUS I. There is an indication that Alexander may have tried to promote brotherhood in these altars. It is just possible that the four-lion emblem of India may be linked to Alexander.

Even in the heyday of Assyriology, when the lure of grand discoveries drew archaeologists to Sumer and Akkad, some eminent figures opted for India. Apart from the enigma of the Indus culture, a prime attraction was the undiscovered altars of Alexander cited in several ancient texts. Alexander was the greatest ambassador of the West, and the failure to locate the altars saddened eminent archaeologists like Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who writes:

And yet it is astonishing how very little actual trace we have of his passing... his material presence has eluded us. It is as though a disembodied idea had come and gone as a mighty spiritual force with little immediate tangibility. 2

The vanishing of the altars was seen by some as an index of the insignificance of Alexander’s legacy, and was at the root of much ignorant criticism levelled against him. However, survival of relics is often a matter of chance; to the layman the accounts of Arrian, Plutarch and others may appear trivial in contrast to the lustre of the Taj Mahal or the splendour of Tutenkhamun’s relics, but the historian must tread cautiously. Natural disasters like earthquakes and floods, wilful destruction by political or religious reactionaries, and at times plain misjudgment of historians, may accumulate in order to diminish a legitimate hero. Lastly one must consider the effects of misappropriation. Had it not been for the ballasting of more than one hundred miles of the Lahore-Multan railway with bricks from the monuments of Harappa, the task of reconstructing the glories of the Indus civilisation would have been far easier.

This background has other dimensions as well: only a little more than fifty years after the construction of the altars, all of which apparently disappeared, one encounters the majestic Asokan pillars. Since Asoka has a very strong presence in the northwest, it is natural to suspect a link between the vanishing of all the altars of Alexander and the simultaneous emergence of nearly the same number of his pillar edicts, many of which had lion-capitals. It can be recalled that when Philip wanted to commemorate the momentous victory at Chaeronea he set up the famous lion statue. It is more than likely that his illustrious son had also erected lion capitals in India.

Who Erected Pillars In India before Asoka?

The find-spots of relics are of great importance in the reconstruction of history; but one of the recurrent problems in Indian history is that pillars were often rewritten and re-erected at different locations. Unfortunately this has been totally ignored by gullible historians like H. C. Raychaudhuri and R. Thapar. Even though the weight of some of these pillars is about thirty tons, it is not safe to assume that they were erected in their present locations. Keay writes:

The question of how these pillars had originally been moved round India, and whether they were still in their ordained positions, was an intriguing subject by itself. It was now apparent that they were all of the same stone, all polished by the same unexplained process, and therefore all from the same quarry. 3 [J. Keay, India Discovered: The Achievement of the British Raj (London 1988) 55.]

Thanks largely to Hodgson's discoveries along the Nepalese frontier, Prinsep knew of five Ashoka columns. As he deciphered their messages a sixth came to light in Delhi (the second to be found there). Broken into three pieces and buried in the ground, it was thought to have been the casualty of an explosion in a nearby gunpowder factory sometime in the 17th century. The inscription was badly worn, though evidently the same as that on the other pillars. In due course the whole pillar was offered to the Asiatic Society for their new museum. They accepted it but found the difficulties and cost of transporting it to Calcutta to be prohibitive; eventually they settled for just the bit with the inscription on it.

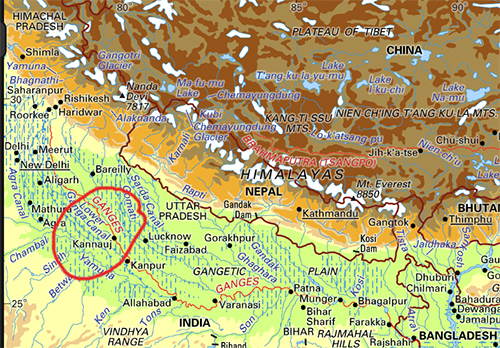

The question of how these pillars had originally been moved round India, and whether they were still in their ordained positions, was an intriguing subject in itself. It was now appreciated that they were all of the same stone, all polished by the same unexplained process, and therefore all from the same quarry. Prinsep thought this was somewhere in the Outer Himalayas, although we now know their source to have been Chunar on the Ganges near Benares. Either way, they had somehow been moved as much as 500 miles, no mean feat considering that the heaviest weighed over 40 tons.

-- India Discovered, by John Keay

Significantly, although most writers placed this quarry at Chunar near Benares, Prinsep located it somewhere in the outer Himalayas. The altars of Alexander were grand structures. Plutarch writes that in his day these were held in much veneration by the Prasiians, whose kings were in the habit of crossing the Ganges every year to offer sacrifices in the Grecian manner upon them (Plut. Alexander, 62). What happened thereafter? Was there a scramble among the later rulers to use these splendid monuments for their own purposes? The fame of Samudragupta as one of the greatest rulers of India rests on his famous Allahabad inscription which was rewritten on an old Asokan pillar. Kulke and Rothermund suggest that it was shifted from Kausambi. In the fourteenth4 century, Sultan Feroz Shah was so impressed by the Asokan pillars that he had two of them shifted to Delhi, one from Meerut and another from Topra in Ambala district, about 90 miles northwest of Delhi.

Monahan writes:

The fact that ten of the pillars bear inscriptions of Ashoka is proof they were erected not later than his reign; it does not prove that none of them was erected earlier.5

In the Sanskrit drama Mudrarakshasa, Chandragupta is called Piadamsana.6 From this, Raychaudhuri concludes that it is not always safe to ascribe all epigraphs that mention Priyadarsana to Ashoka the Great. The intriguing fact7 is that Asoka says that pillars bearing edicts had been in existence in India before his time; he was not the first to use pillars for the propagation of Dhamma (Eusebia). In the seventh Pillar Edict, after recording that he has erected ‘pillars of the Sacred Law’ (dhammathambani), Asoka writes:

Etaṃ devānaṃpiye āhā: iyaṃ dhaṃma-libi ata athi silā-thaṃbānii vā, silā phalakāni vā tata kaṭaviyā ena esa cila-ṭhitike siyā.

The Devānamṃpiya said: wherever there are either stone pillars or stone slabs, thereon this Dharma rescript is to be engraved, so that it may long endure.8

This shows that there were already pillars in India before the Asokan era and also implies that, like Samudragupta, Asoka also had engraved his own message on at least some of them. To realise that no one other than Alexander could have erected these pre-Asokan pillars, one has to take a close look into an age-old blunder in Indology that has greatly falsified world history.

The Location of Palibothra

Alexander historians have often been baffled by the scarcity of new sources, archaeological or textual, and new writers are usually content with reinterpretation of old documents. Unfortunately this is due to a faulty9 perspective; too much stress has been laid on the Greek and Roman sources at the expense of crucial data from Sanskrit and Pali documents. Moreover, the value of the Indian sources has been impaired by one fatal error—Jones’s location of Palibothra at Patna. This has not only blurred the identity of major10 conspirators in the history of Alexander, but has also left room for much injudicious criticism against him. Once Jones’s idea is rejected and the scenario is shifted to the northwest, important clarifications emerge in the history not only of India but also that of Iran and Afghanistan. It turns out that Alexander11 was chasing through Gedrosia a very powerful adversary, and that he was not quite the villain that he has been made out to be.

Gedrosia is a dry, mountainous country along the northwestern shores of the Indian Ocean. It was occupied in the Bronze Age by people who settled in the few oases in the region. Other people settled on the coast and became known in Greek as Ichthyophagi.

The country was conquered by the Persian king Cyrus the Great (559-530 BCE), although information about his campaign is comparatively late. The capital of Gedrosia was Pura, which is probably identical to modern Bampûr, forty kilometers west of Irânshahr.

Gedrosia became famous in Europe when the Macedonian king Alexander the Great tried to cross the Gedrosian desert and lost one third of his men.

-- Gedrosia (satrapy), by Wikipedia

Recounting the scenario after the Hyphasis mutiny (Arr. 5.25, Diod. 17.93-5, Curt. 9.2.1-3.19), Badian writes with an air of definiteness:

For the moment, he tried to use the weapon that had succeeded before. He withdrew to his tent, for three days. But this time it did not help. The men were determined, and as Coenus had made clear, they had the officers’ support. Alexander could not divide them. All that remained was to save face.12

Badian not only finds Alexander in an awkward position, but also casually notes his subsequent declaration that he would go on nonetheless and his ordering of sacrifices for crossing the river. Alexander’s vow to fight against the Prasii in13 the face of stiff opposition from both the soldiers and officers does appear somewhat comical but here lies a trap—where was their capital Palibothra? Could it really have been at Patna, so far removed from the northwest—the centre of early India?

The significance of this question has been glossed over by all. Only Hammond, discoverer of Aegai, recognises the crucial role of geography in history, and states that ‘Patna is too far east’ to be a Palibothra. Renowned14 archaeologists like A. Ghosh also point out that Jones’s discovery has no archaeological basis. Kulke and Rothermund likewise doubt the Jonesian15,16 story. It is well known that the Maurya empire extended to the west as far as Aria, Seistan and Makran and this makes it likely that Palibothra was in this17 region. Elisseeff remarks that from the archaeological viewpoint, eastern Iran18 was closer to India. Bivar is unaware of Jones’ error or the appalling frauds in19 Nepalese archaeology and his view about the Persepolis tablets is heedless and 20 empty:

So far as India is concerned, the Fortification Tablets attest an active and substantial traffic, though they shed no light on the geography of that province. 21

The tablets not only throw invaluable light on the geography of greater India but provide data that revolutionise Indology. Sedda Saramana of the tablets appears to be Siddhartha (Sedda-Arta) Gotama and the ubiquitous Suddayauda Saramana seems to be his father Suddo-dhana. Al-beruni writes that Gotama’s real name was Buddho-dana which puts him in the same bracket as Daniel.22 Nunudda of the tablets may be Nanda, a relative of Gotama.

Alexander’s Return Through Gedrosia After the Hyphasis Mutiny

Through the mist of vague reports and geographical misconceptions, it is difficult to probe into the Hyphasis revolt, which came as a serious jolt to Alexander. After this, even though there were safer routes, Alexander chose to return to Iran through the desert of Gedrosia, suffering heavy losses in soldiers and civilians from lack of water, food and the extreme heat. That the motive behind this voyage has appeared so perplexing is due to two crucial lapses—the false location of Palibothra, capital of the Prasii, and the concomitant failure to recognise the mysterious Moeris of Pattala who played a determinant role.

‘Alexander, of course, had read Herodotus’, writes Badian, but misses23 the purport of his reference to Indians in the Gedrosia area. Toynbee writes on world history and makes no mistake to note the shifting nature of India’s boundary:

... and we can already see the beginnings of this progressive extension of the name ‘Indian’ in Herodotus’s usage.24

The reports of Alexander’s historians clearly indicate that southeast Iran was within Greater India in the fourth century BC. As Prasii was in the Gedrosia area, the question arises—did the army refuse to fight the Prasii or only to march eastwards? If Alexander wanted to move eastward it was not to defeat the Prasii. Tarn writes that he had nothing to do with Magadha on the Ganges. If25 he had learnt that the fertile Gangetic plains were only a few days’ march away, and wanted to be there for mere expansion of empire, he would have met little resistance. Reluctance of the army could be due to the lack of any tangible gain, not fear of the mighty Easterners. If this was the case, then Alexander bowed down to the wishes of his men. However, if the reluctance was to confront the Prasii, it appears sensible due to their formidable strength. As Moeris had fought beside Porus, the Prasiian army cannot have been left intact, though it could still have been a fighting force. It is probable that Moeris and his agents fomented discord among Alexander’s officers and soldiers. The magicians and26 other secret agents of Moeris probably overblew the might of the Prasii in order to frighten the invaders. From this point onwards, if not earlier, Eumenes, Perdikkas and Seleucus may have been in touch with Moeris.

Porus himself, mounted on a tall elephant, not only directed the movements of his forces but fought on to the very end of the contest; he then received a wound on his right shoulder, the only unprotected part of his body, all the rest of his person being rendered shot-proof by a coat of mail remarkable for its strength and closeness of fit; he now turned his elephant and began to retire. Alexander who had observed and admired his valour in the field was anxious to save his life and sent Taxiles after him on horseback to summon him to surrender; but the sight of this old enemy and traitor roused the indignation of the Paurava, who gave him no hearing and would have killed him, had not Taxiles instantly put his horse to the gallop and got beyond the reach of Porus’. Even this Alexander did not resent; he sent other messengers till at last Meroes (Maurya ?), an old friend of Porus, persuaded him to hear the message of Alexander.

-- Chapter II: Alexander's Campaigns in India, Excerpt from "Age of the Nandas and Mauryas", by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri

Victory Over Moeris At Palibothra

Only Justin (Just. xii, 8) reports that Alexander had defeated the Prasii.

There was one of the kings of India, named Porus, equally distinguished for strength of body and vigour of mind, who, hearing of the fame of Alexander, had been for some time before preparing for war against his arrival. Coming to battle with him, accordingly, he directed his soldiers to attack the rest of the Macedonians, but desired that their king should be reserved as an antagonist for himself. Nor did Alexander decline the contest; but his horse being wounded in the first shock, he fell headlong to the ground, and was saved by his guards gathering round him. Porus, covered with a number of wounds, was made prisoner, and was so grieved at being defeated, that when his life was granted him by the enemy, he would neither take food nor suffer his wounds to be dressed, and was scarcely at last prevailed upon to consent to live. Alexander, from respect to his valour, sent him back in safety to his kingdom. Here he founded two cities, one called Nicaea, and the other, from the name of his horse, Bucephale.

He then overthrew the Adrestae, the Gesteani, the Presidae, and the Gangaridae, with great slaughter among their troops. When he had reached the Cuphites, where the enemy awaited him with two thousand cavalry, the whole army, wearied not less with the number of their victories than with their toils in the field, besought him with tears that “he would at length make an end of war, and think on his country and his return; considering the years of his soldiers, whose remainder of life would scarcely suffice for their journey home.” One pointed to his hoary hairs, another to his wounds, another to his body worn out with an age, another to his person disfigured with scars,6 saying “that they were the only men who had endured unintermitted service under two kings, Philip and Alexander;” and conjuring him in conclusion that “he should restore their remains at least to the sepulchres of their fathers, since they failed not in zeal but in age; and that, if he would not spare his soldiers, he should yet spare himself, and not wear out his good fortune by pressing it too far.” Moved with these reasonable supplications, he ordered a camp to be formed, as if to mark the termination of his conquests, of greater size than usual, by the works of which the enemy might be astonished, and an admiration of himself be left to posterity. No task did the soldiers execute with more alacrity. After great slaughter of the enemy, they returned to this camp with mutual congratulations.

-- Just. xii, 8

Delu is said to have been a prince of uncommon bravery and generosity; benevolent towards men, and devoted to the service of God. The most remarkable transaction of his reign is the building of the city of Delhi, which derives its name from its founder, Delu. In the fortieth year of his reign, Phoor, a prince of his own family, who was governor of Cumaoon, rebelled against the Emperor, and marched to Kinoge, the capital. Delu was defeated, taken, and confined in the impregnable fort of Rhotas.

Phoor immediately mounted the throne of India, reduced Bengal, extended his power from sea to sea, and restored the empire to its pristine dignity. He died after a long reign, and left the kingdom to his son, who was also called Phoor, and was the same with the famous Porus, who fought against Alexander.

The second Phoor, taking advantage of the disturbances in Persia, occasioned by the Greek invasion of that empire under Alexander, neglected to remit the customary tribute, which drew upon him the arms of that conqueror. The approach of Alexander did not intimidate Phoor. He, with a numerous army, met him at Sirhind, about one hundred and sixty miles to the north-west of Delhi, and in a furious battle, say the Indian historians, lost many thousands of his subjects, the victory, and his life. The most powerful prince of the Decan, who paid an unwilling homage to Phoor, or Porus, hearing of that monarch's overthrow, submitted himself to Alexander, and sent him rich presents by his son. Soon after, upon a mutiny arising in the Macedonian army, Alexander returned by the way of Persia.

Sinsarchund, the same whom the Greeks call Sandrocottus, assumed the imperial dignity after the death of Phoor, and in a short time regulated the discomposed concerns of the empire. He neglected not, in the mean time, to remit the customary tribute to the Grecian captains, who possessed Persia under, and after the death of, Alexander. Sinsarchund, and his son after him, possessed the empire of India seventy years. When the grandson of Sinsarchund acceded to the throne, a prince named Jona, who is said to have been a grand-nephew of Phoor, though that circumstance is not well attested, aspiring to the throne, rose in arms against the reigning prince, and deposed him.

-- The History of Hindostan, In Three Volumes, Volume I, by Alexander Dow, Esq., Lieutenant-Colonel in the Company's Service, 1812

Palibothra, the Prasiian capital was famous for peacocks. Lane Fox writes:

... Dhana Nanda's kingdom could have been set against itself and Alexander might yet have walked among Palimbothra's peacocks.27

Curiously, Arrian writes that Alexander was so charmed by the beauty of peacocks that he decreed the severest penalties against anyone killing them (Arrian, Indica, xv.218). The picture of Alexander amidst peacocks appears28 puzzling: where did he come across the majestic bird? Does this fascination lead us to Palibothra? The height of absurdity is reached when we are told that eighteen months after the battle with Porus, Alexander suddenly remembered his ‘victory over the Indians’ in the wilderness of Carmania and set upon to celebrate it with fabulous mirth and abandon. Surprisingly it did not jar with the common sense of anyone why this was not celebrated in India. The ‘victory over the Indians’ in southeast Iran can lead to only one judicious conclusion—this was India in the fourth century BC. Moreover, if Alexander had indeed defeated the Indians, who could have been their leader but Moeris or Maurya? This clearly indicates that Alexander had indeed conquered the Prasii in Gedrosia.

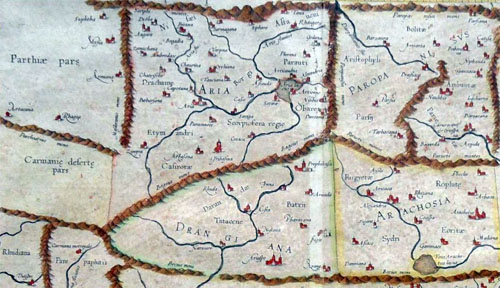

Excerpt from Ptolemy's 9th Asian Map, depicting the lands just west of the Indus River during classical antiquity.

Carmania (Greek: Καρμανία, Karmanía, Old Persian: [x] Karmanā, Middle Persian: Kirmān) is a historical region that approximately corresponds to the modern Iranian province of Kerman, and was a province of the Achaemenid, Seleucid, Arsacid, and Sasanian Empire. The region bordered Persia in the west, Gedrosia in the south-east, Parthia in the north (later known as Abarshahr), and Aria to the north-east. Carmania was considered part of Ariana.

-- Carmania (region), by Wikipedia

Bosworth writes that the name of the place where the victory was celebrated was Kahnuj. The name tells all, for Kanauj was the chief city of the29 Indians, the name of which is echoed in the famous city in eastern India which later became most important.

[29. A. B. Bosworth, Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great (Cambridge 1988) 150, who gives the name Khanu (maps usually give the name Kohnouj or Kahnuj). Nearby Patali may have been Palibothra.]

As the winter deepened, Alexander approached the Carmanian capital, which Diodorus (xvii.106.4) names Salmus. It was, according to Nearchus (Arr. Ind. 33.7), five days' journey from the coast. The site remains a mystery,386 but it was probably at the western side of the valley of the Halil Rud, in the general vicinity of the modern town of Khanu. The army was in an area of relative plenty but close enough to the coast to receive news of the progress of Nearchus' fleet. There Alexander sacrificed to commemorate his Indian victory and the emergence from the Gedrosian desert, and he held a musical and athletic festival, a drunken and festive affair, notable for the general acclaim achieved by Alexander's favourite Bagoas when he entered the winning chorus.387 During the celebrations, if not before, news came of Nearchus' safe arrival at Harmozeia, the principal seaport of Carmania. The details are supplied for us by Nearchus, and they are open to justifiable suspicion. Nearchus has a rich story, full of dramatic peripeteia, in which he unexpectedly learns of the king's presence in the near vicinity, marches up county with a small escort, strangely missing the search parties sent out by his anxious king, and is finally retrieved, unrecognisable from brine and fatigue, to give the glad news of the fleet's survival to Alexander in person. The details of this Odyssey are beyond verification and there is very probably a good deal of imaginative embellishment.388 What is certain is that the fleet arrived at Harmozeia without serious loss and that its arrival was announced to Alexander by Nearchus in person. It was a moment of general exaltation, and, if we may believe Nearchus (Arr. Ind. 36.3), Alexander renewed the sacrifices and prolonged the games. The celebrations which had begun commemorating the delivery of the army from Gedrosia ended with thanks-offerings for the safe arrival of the fleet.

-- A. B. Bosworth, Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great (Cambridge 1988), p. 150

Kahnuj (Persian: كهنوج, also Romanized as Kahnūj) is a city and capital of Kahnuj County, Kerman Province, Iran.

-- Kahnuj, by Wikipedia

***

Patali (Persian: پاتلي, also Romanized as Pātalī; also known as Kheyrābād-e Pātelī) is a village in Jahadabad Rural District, in the Central District of Anbarabad County, Kerman Province, Iran.

-- Patali, Anbarabad, by Wikipedia

Pataligram to Patna -- The Historical Journey Of The 'City of Flowers'

The cities, towns or villages that once occupied the site of modern Patna had carried quite a large number of names in different periods of history and most of them were in the name of 'FLOWERS.' The earliest to exist at the site seems to have been a small sprawling village with the name of Patali, Pataligrama, Padali or Padalipura as mentioned in Buddhist and Jain traditions.

Vayupurana mentions the name of Pataliputra as Kusumapura. In Tattvarthasutra of Umasvati, a celebrated Jain Author who lived here in the first-second centuries A.D., the place is described as Kusumapura. It literally means a 'city of flowers.' Gargi-Samhita names Pataliputra as Kusum-Dhvaja or Pushpapura -- variant of Kusumapura. The modern name of Phulwarisharif of a small hamlet near Patna is obviously a survival of the ancient name. One tradition says that in the time of Nandas, the name was Padmawati. It is under the Mauryans that the name of Pataliputra came in common use. Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador, at the court of Chandragupta Maurya, mentioned Pataliputra with the Greek utterance of 'Palibothra.' The celebrated Buddhist monk, Hiuen-Tsang who came to India in the seventh century A.D., also knew it by the name of Pataliputra.

-- The Wonder That Was Pataliputra, by brandingbihar.com

"Karavira, Jati, Champaka, Lotus, and Patali, are the five flowers (275)."

-- Mahanirvana Tantra: Tantra of the Great Liberation, Translated by Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe)