Chapter 1: India – Diplomacy and Ethnography at the Mauryan Empire

Excerpt from "The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire"

by Paul J. Kosmin

© 2014 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

In the year 305 BC, Seleucus I Nicator went to India and apparently occupied territory as far as the Indus, and eventually waged war with the Maurya Emperor Chandragupta Maurya.[citation needed]

Only a few sources mention his activities in India. Chandragupta (known in Greek sources as Sandrokottos), founder of the Mauryan empire, had conquered the Indus valley and several other parts of the easternmost regions of Alexander's empire. Seleucus began a campaign against Chandragupta and crossed the Indus.[39] Most western historians note that it appears to have fared poorly as he did not achieve his goals[citation needed], even though what exactly happened is unknown. The two leaders ultimately reached an agreement,[40] [Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire. P. 98.] and through a treaty sealed in 305 BC,[41] [John Keay (2001). India: A History. Grove Press. pp. 85–86.] Seleucus abandoned the territories he could never securely hold in exchange for stabilizing the East and obtaining elephants, with which he could turn his attention against his great western rival, Antigonus Monophthalmus.[40] The 500 war elephants Seleucus obtained from Chandragupta were to play a key role in the forthcoming battles, particularly at Ipsus [42] against Antigonus and Demetrius. The Maurya king might have married the daughter of Seleucus.[43] [Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (2003) [1952]. Ancient India. P. 105.]

-- Seleucus I Nicator, by Wikipedia

Chapter 1: India – Diplomacy and Ethnography at the Mauryan Empire

From Alexander the Great's death at Babylon in 323 until the first decades of the third century the lands over which he had ruled were convulsed by the ambitions, assassinations, and alliances of his greatest generals. With almost forty years of warfare and betrayal, vertiginous collapse and unexpected rise, it is no surprise that Tyche, capricious Fate, achieves new causal prominence in the historiography of this period.1 [ ] But if we stand at a distance from what Braudel called history's "crests of foam," we can understand the playing out of the succession crisis as the birth pangs of a new, but not unfamiliar, world order: the peer-kingdom international system.

Alexander's kingdom, like the Achaemenid imperial structure he conquered and reelaborated, was a hegemonic world empire characterized by an emphasis on totality and exclusivity.2 [ ] The Persian Great King and Alexander monopolized legitimate sovereignty and recognized no entity as external and equivalent. The fragmentation of this all-embracing imperial formation after Alexander's death and the stabilization of independent kingdoms multiplied the royal persona and state. A diachronic succession of world-empires (Achaemenids to Alexander) was replaced with the synchronic coexistence of bounded kingdoms. The emergence of a few "Great Powers" (Antigonid Macedonia, Ptolemaic Egypt, Seleucid Asia, as well as Attalid Pergamum, Mauryan India, the Anatolian kingdoms, and Rome) gradually developed into a system of peer states with semiformalized procedures of interaction. In other words, the east Mediterranean-west Asian region settled back into the multipolarity that had characterized it in the Neo-Babylonian period, immediately before Cyrus' conquests and the foundation of the Persian empire, and in the famous Late Bronze Age of Amarna.3 [ ]

This historical process of division and multiplication can be traced throughout the Wars of Succession that followed Alexander's death.4 [ ] By the third century, a developed and unquestioned international order was operating within the broader Hellenistic world; multipolarity was the assumed framework for everything from asylia (recognition of a city's inviolability)5 [ ] and festival requests6 [ ] to benefactions following natural disasters.7 [ ] Of paramount importance to such a system was the "border," both in its technical definition and its ideological implications. Kingdoms had to be recognized as spatially limited units, as bounded territories with shared frontiers. In this first part of The Land of the Elephant Kings I investigate the construction of the Seleucid empire's political boundary in the east.

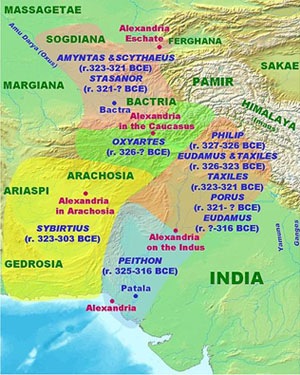

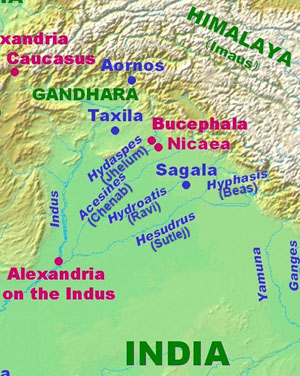

In 305 or 304, Macedonian forces once again issued out of the Hindu Kush, more than two decades after they had first entered the Indus valley behind Alexander the Great:8 [ ] for Seleucus I Nicator, who over the previous half decade had extended his authority from Babylonia to Bactria, now led his army in a second Indian invasion. This campaign and the diplomatic agreement that concluded it formed the foundational moment of Seleucid imperial space. For the first time, Seleucus I's rule was formally bounded and thereby territorialized, fixing the empire's southeastern border for at least a century. Furthermore, the encoding of this new political situation in Seleucid court ethnography -- specifically, the Indica of Megasthenes, Seleucus' ambassador to the Indian court -- demonstrates the profound impact of this historical moment on traditional geographical and ethnological ideas.

The Treaty of the Indus

In contrast to the untidy patchwork of rival principalities and gana-sangha oligarchies encountered by Alexander, the land Seleucus entered had recently been annexed and united by Chandragupta Maurya, the new ruler of the first pan-north Indian imperial entity.9 [ ]

Chandragupta had defeated the remaining Macedonian satrapies in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent by 317 BCE.

-- Chandragupta Maurya, by Wikipedia

Seleucus apparently minted coins during his stay in India, as several coins in his name are in the Indian standard and have been excavated in India. These coins describe him as "Basileus" ("King"), which implies a date later than 306 BC. Some of them also mention Seleucus in association with his son Antiochus as king, which would also imply a date as late as 293 BC.

-- Seleucus I Nicator, by Wikipedia

Chandragupta, appearing in classical sources as (S)androcottus,10 [ ] was a peer of the Macedonian Successors and integrated into their world and its struggles.11 [ ] Like them, the new Indian potentate is shown emphasizing his links to Alexander: Plutarch records that king Sandrocottus claimed to have met Alexander as a youth,12 [ ] compared himself to the great Macedonian,13 [ ] and sacrificed on the altars erected by Alexander on the bank of the Hyphasis (mod. Beas) whenever he crossed the river.14 [ ]

Through the mist of vague reports and geographical misconceptions, it is difficult to probe into the Hyphasis revolt, which came as a serious jolt to Alexander. After this, even though there were safer routes, Alexander chose to return to Iran through the desert of Gedrosia, suffering heavy losses in soldiers and civilians from lack of water, food and the extreme heat. That the motive behind this voyage has appeared so perplexing is due to two crucial lapses—the false location of Palibothra, capital of the Prasii, and the concomitant failure to recognise the mysterious Moeris of Pattala who played a determinant role.

‘Alexander, of course, had read Herodotus’, writes Badian, but misses the purport of his reference to Indians in the Gedrosia area.

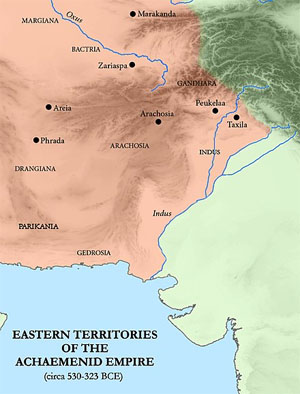

Territory of Gedrosia, among the eastern territories of the Achaemenid Empire.

-- Gedrosia, by Wikipedia

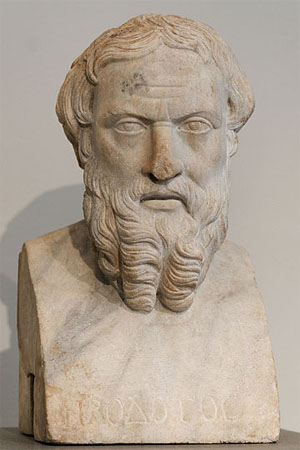

Toynbee writes on world history and makes no mistake to note the shifting nature of India’s boundary:... and we can already see the beginnings of this progressive extension of the name ‘Indian’ in Herodotus’s usage.

The reports of Alexander’s historians clearly indicate that southeast Iran was within Greater India in the fourth century BC. As Prasii was in the Gedrosia area, the question arises—did the army refuse to fight the Prasii or only to march eastwards? If Alexander wanted to move eastward it was not to defeat the Prasii. Tarn writes that he had nothing to do with Magadha on the Ganges. If he had learnt that the fertile Gangetic plains were only a few days’ march away, and wanted to be there for mere expansion of empire, he would have met little resistance. Reluctance of the army could be due to the lack of any tangible gain, not fear of the mighty Easterners. If this was the case, then Alexander bowed down to the wishes of his men. However, if the reluctance was to confront the Prasii, it appears sensible due to their formidable strength. As Moeris had fought beside Porus, the Prasiian army cannot have been left intact, though it could still have been a fighting force. It is probable that Moeris and his agents fomented discord among Alexander’s officers and soldiers. The magicians and other secret agents of Moeris probably overblew the might of the Prasii in order to frighten the invaders. From this point onwards, if not earlier, Eumenes, Perdikkas and Seleucus may have been in touch with Moeris.

Victory Over Moeris At Palibothra

Only Justin (Just. xii, 8) reports that Alexander had defeated the Prasii. Palibothra, the Prasiian capital was famous for peacocks....

Curiously, Arrian writes that Alexander was so charmed by the beauty of peacocks that he decreed the severest penalties against anyone killing them (Arrian, Indica, xv.218). The picture of Alexander amidst peacocks appears puzzling: where did he come across the majestic bird? Does this fascination lead us to Palibothra? The height of absurdity is reached when we are told that eighteen months after the battle with Porus, Alexander suddenly remembered his ‘victory over the Indians’ in the wilderness of Carmania and set upon to celebrate it with fabulous mirth and abandon. Surprisingly it did not jar with the common sense of anyone why this was not celebrated in India. The ‘victory over the Indians’ in southeast Iran can lead to only one judicious conclusion—this was India in the fourth century BC. Moreover, if Alexander had indeed defeated the Indians, who could have been their leader but Moeris or Maurya? This clearly indicates that Alexander had indeed conquered the Prasii in Gedrosia.

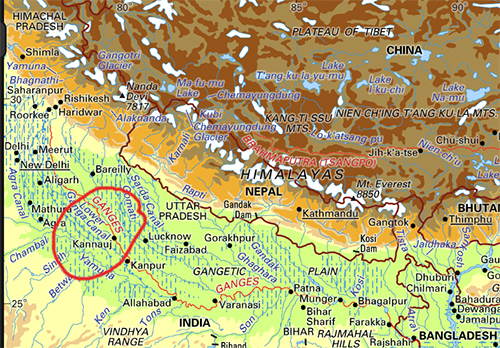

Bosworth writes that the name of the place where the victory was celebrated was Kahnuj. The name tells all, for Kanauj was the chief city of the Indians, the name of which is echoed in the famous city in eastern India which later became most important.

Smith is aware that Kanauj in eastern India was not the city mentioned in the ancient texts [??]; yet he does not suspect that the same could be true of Jones’ Palibothra. Dow identifies Sandrocottos with Sinsarchund who, according to Firista, ruled from Kanauj [Kinoge].

Nearchus certainly had other tasks than scientific fact-finding; the army was ordered to keep close to the shore and the navy moved in tandem. This orchestration and the large number of troops and horses on ships (quite unnecessary for a scientific mission) show that the navy was not only carrying provisions for the army which was engaged in a grim and protracted battle with a mighty adversary, but that the troops on the ships were also ready to support the army if needed. This is why the navy waited for twenty-four days near Karachi. The names Pataliputra and Pattala and Moeris and Maurya leave little to imagination.

Yet Badian fails to recognise that Moeris was Chandragupta Maurya of Prasii.

-- An Altar of Alexander Now Standing at Delhi [EXPANDED VERSION], by Ranajit Pal

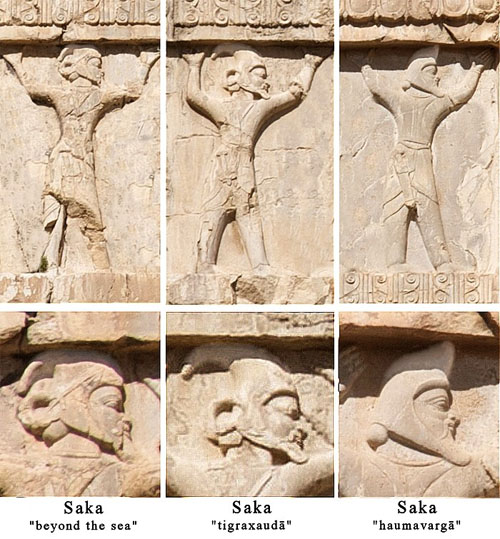

Greek scholars often mentioned that Sandrocottus was the king of the country called as Prasii (Prachi or Prachya). Pracha or Prachi means eastern country. During the Nanda and Mauryan era, Magadha kings were ruling almost entire India. Mauryan Empire was never referred in Indian sources as only Prachya desa or eastern country. Prachya desa was generally referred to Gupta Empire because Northern Saka Ksatrapas and Western Saka Ksatrapas were well established in North and West India. Megasthenes mentioned that Sandrocottus is the greatest king of the Indians and Poros is still greater than Sandrocottus which means a kingdom in the North-western region is still independent and enjoying at least equal status with the kingdom of Sandrocottus...

-- Who was Sandrocottus: Samudragupta or Chandragupta Maurya?, The Chronology of Ancient India, Victim of Concoctions and Distortions, by Vedveer Arya

Megasthenes says that he often visited Sandrokottos, the greatest king (maharaja: v. Bohlen, Alte Indian, I. p. 19) of the Indians, and Poros, still greater than he: — Arrian, Lid. c. 5 (Fragm. 24).

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle

The course of Seleucus’ campaign against this Indian emperor is not known in detail – an obscurity that has tempted modern historians to political allegory and forgery.15 [ ] Certainly, Seleucus crossed his forces over the river Indus, so invading India proper,16 [ ] but whether Seleucid and Mauryan armies fought a pitched battle is still debated. Whatever happened, at some point, in a momentous and foundational act of the new world order, Seleucus and Chandragupta decided to make peace. The ancient historians Justin, Appian, and Strabo ...

Justinus (XV. 4) says of Seleukos Nikator,"He carried on many wars in the East after the division of the Makedonian kingdom between himself and the other successors of Alexander, first seizing Babylonia, and then reducing Baktriane, his power being increased by the first success. Thereafter he passed into India, which had, since Alexander's death, killed its governors, thinking thereby to shake off from its neck the yoke of slavery. Sandrokottos had made it free: but when victory was gained he changed the name of freedom to that of bondage, for he himself oppressed with servitude the very people which he had rescued from foreign dominion. Sandrokottos, having thus gained the crown, held India at the time when Seleukos was laying the foundations of his future greatness. Seleukos came to an agreement with him, and, after settling affairs in the East, engaged in the war against Antigonos (302 B.C.).'

Besides Justinus, Appianus [c. 95 – c. AD 165)] (Syr. c. 55) makes mention of the war which Seleukos had with Sandrocottos or Chandragupta king of the Prasii, or, as they are called in the Indian language, Prachyas: [The adjective [x] in Aelianus On the Nature of Animals, xvii. 39 (Megasthen. Fragm. 13. init.) bears a very close resemblance to the Indian word Prachyas (that is 'dwellers in the East'). The substantive would be [x], and Schwanbeck (Megasthenis Indica, p. 82) thinks that this reading should probably be restored in Stephanus of Byzantium, where the MSS. exhibit [x], a form intermediate between [x] and [x]. But they are called [x] by Strabo, Arrianus, and Plinius; [x] in Plutarch (Alex. chap. 62), and frequently in Aeliauna; [x] by Nicolaiis of Damascus, and in the Florilegium of Stobaeus, 37, 38; [x] and [x] are the MS. readings in Diodorus, xvii. 93; Pharranii in Curtius, IX. ii. 3; Praesidae in Justinus, XII. viii. 9. See note on Fragm. 13.]—'He (Seleukos) crossed the Indus and waged war on Sandrokottos, king of the Indians who dwelt about it, until he made friends and entered into relations of marriage with him.'

So also Strabo (xv. p. 724): —'Seleukos Nikator gave to Sandrokottos' (sc. a large part of Ariane). Conf. p. 689: — 'The Indians afterwards held a large part of Ariane, (which they had received from the Makedonians), 'entering into marriage relations with him, and receiving in return five hundred elephants' (of which Sandrakottos had nine thousand— Plinius, vi. 22-5);

and Plutarch, Alex. 62:—'For not long after, Androkottos, being king, presented Seleukos with five hundred elephants, and with six hundred thousand [600,000] men attacked and subdued all India.

Phylarchos (Fragm. 28) in Athenaeus, p. 18 D., refers to some other wonderful enough presents as being sent to Seleukos by Sandrokottos.

"Diodorus [90 B.C.-30 B.C.] (lib. xx.), in setting forth the affairs of Seleukos, has not said a single word about the Indian war. But it would be strange that that expedition should be mentioned so incidentally by other historians, if it were true, as many recent writers have contended, that Seleukos in this war reached the middle of India as far as the Ganges and the town Palimbothra, — nay, even advanced as far as the mouths of the Ganges, and therefore left Alexander far behind him. This baseless theory has been well refuted by Lassen (De Pentap. Ind. 61), by A. G. Schlegel (Berliner Calendar, 1829, p. 31 yet see see Benfey, Ersch. n. Gruber. Encycl. v. Indien, p. 67), and quite recently by Schwanbeck, in a work of great learning and value entitled Megasthenis Indica (Bonn 1846). In the first place, Schwanbeck (p. 13) mentions the passage of Justinus (I. ii. 10) where it is said that no one had entered India but Semiramis and Alexander; whence it would appear that the expedition of Seleukos was considered so insignificant by Trogus as not even to be on a par with the Indian war of Alexander. [Moreover, Schwanbeck calls attention (p. 14) to the words of Appianus (i. 1), whom when he says, somewhat inaccurately, that Sandrakottos was king of the Indians around the Indus([x]) he seems to mean that the war was carried on on the boundaries of India. But this is of no importance, for Appianus has [x], 'of the Indians around it,' as Schwanbeck himself has written it (p. 13).] Then he says that Arrianus, if he had known of that remote expedition of Seleukos, would doubtless have spoken differently in his Indika (c. 5. 4), where he says that Megasthenes did not travel over much of India, 'but yet more than those who invaded it along with Alexander the son or Philip.' Now in this passage the author could have compared Megasthenes much more suitably and easily with Seleukos. [The following passage of the Indian comedy Mudrarakshasa seems to favour the Indian expedition: — "Meanwhile Kusmuapura (i.e. Pataliputra, Palimbothra) the city of Chandragupta and the king of the mountain regions, was invested on every side, by the Kiratas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Persians, Baktrians, and the rest." But "that drama" (Schwanbeck, p. 18), "to follow the authority of Wilson, was written in the tenth century after Christ,— certainly ten centuries after Seleukos. When even the Indian historians have no authority in history, what proof can dramas give written after many centuries? Yavanas, which was also in later times the Indian name for the Greeks, was very anciently the name given to a certain nation which the Indians say dwelt on the north-western boundaries of India; and the same nation (Manu, x. 44) is also numbered with the Kambojas, the Sakas, the Paradas, the Pallavas, and the Kiratas as being corrupted among the Kshatriyas. (Conf. Lassen, Zeitschrift fur d. Kunde des Morgentandes, III p. 245). These Yavanas are to be understood in this passage also, where they are mentioned along with those tribes with which they are usually classed.] I pass over other proofs of less moment, nor indeed is it expedient to set forth in detail here all the reasons from which it is improbable of itself that the arms of Seleukos ever reached the region of the Ganges.

Let us now examine the passage in Plinius which causes man to adopt contrary opinions. Plinius (Hist. Nat. vi. 21), after finding from Diognetos and Baeto the distances of the places from Portae Caspiae to the Huphasis, the end of Alexander's march, thus proceeds: — 'The other journeys made for Seleukos Nikator are as follows: One hundred and sixty-eight miles to the Hesidrus, and to the river Jomanes as many (some copies add five miles); from thence to the Ganges one hundred arid twelve miles. One hundred and nineteen miles to the Rhodophas (others give three hundred and twenty-five miles for this distance). To the town Kalinipaxa one hundred and sixty-seven. Five hundred (others give two hundred and sixty-five miles), and from thence to the confluence of the Jomanes and Ganges six hundred and twenty-five miles (several add thirteen miles), and to the town Palimbothra four hundred and twenty-five. To the mouth of the Ganges six hundred and thirty-eight' (or seven hundred and thirty-eight, to follow Schwanbeck's correction), — that is, six thousand stadia, as Megasthenes puts it.

"The ambiguous expression reliqua Seleuco Nicatori peragrata suat, translated above as 'the other journeys made, for Seleukos Nikator,' according to Schwanbeck's opinion, contain a dative 'of advantage,' and therefore can bear no other meaning. The reference is to the journeys of Megasthenes, Deimachos, and Patrokles, whom Seleukos had sent to explore the more remote regions of Asia. Nor is the statement of Plinius in a passage before this more distinct. ('India,') he says, 'was thrown open not only by the arms of Alexander the Great, and the kings who were his successors, of whom Seleucus and Antiochus even travelled to the Hyrcanian and Caspian seas, Patrocles being commander of their fleet, but all the Greek writers who stayed behind with the Indian kings (for instance, Megasthenes, and Dionysius, sent by Philadelphus for that purpose) have given accounts of the military force of each nation.' Schwanbeck thinks that the words circumsectis etiam ... Seleuco et Antiocho et Patrocle are properly meant to convey nothing but additional confirmation, and also an explanation how India was opened up by the arms of the kings who succeeded Alexander."

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle

preserve the three main terms of what I will call the Treaty of the Indus:17 [ ]

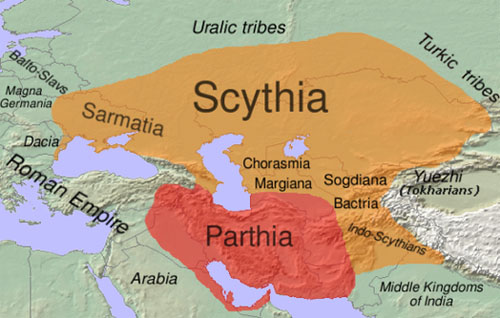

(i) Seleucus transferred to Chandragupta’s kingdom the easternmost satrapies of his empire, certainly Gandhara, Parapamisadae, and the eastern parts of Gedrosia,18 [ ] and possibly also Arachosia and Aria as far as Herat.19 [ ]

Some authors say that the argument relating to Seleucus handing over more of what is now southern Afghanistan is an exaggeration originating in a statement by Pliny the Elder referring not specifically to the lands received by Chandragupta, but rather to the various opinions of geographers regarding the definition of the word "India":Most geographers, in fact, do not look upon India as bounded by the river Indus, but add to it the four satrapies of the Gedrose, the Arachotë, the Aria, and the Paropamisadë, the River Cophes thus forming the extreme boundary of India. According to other writers, however, all these territories, are reckoned as belonging to the country of the Aria. — Pliny, Natural History VI, 23

Nevertheless, it is usually considered today that Arachosia and the other three regions did become dominions of the Mauryan Empire.[citation needed]

(ii) Chandragupta gave Seleucus 500 Indian war elephants.20 [ ]

(iii) The two kings were joined by some kind of marriage alliance ([x] or [x]); most likely Chandragupta wed a female relative of Seleucus.21 [ ]

The alliance between Chandragupta[??] and Seleucus was affirmed with a marriage (Epigamia). Chandragupta[??] or his son may have married a daughter of Seleucus, or perhaps there was diplomatic recognition of intermarriage between Indians and Greeks.

-- Seleucus I Nicator, by Wikipedia

Having punished with a stern hand the misrule of his satraps, Macedonian and Persian alike, Alexander began to carry out schemes which he had formed. He had unbarred and unveiled the Orient to the knowledge and commerce of the Mediterranean peoples, but his aim was to do much more than this; it was no less than to fuse Asia and Europe into a homogeneous unity. He devised various means for compassing this object. He proposed to transplant Greeks and Macedonians into Asia, and Asiatics into Europe, as permanent settlers. This plan had indeed been partly realised by the foundation of his numerous mixed cities in the Far East. The second means was the promotion of intermarriages between Persians and Macedonians, and this policy was inaugurated in magnificent fashion at Susa. The king himself espoused Statira, the daughter of Darius; his friend Hephaestion took her sister; and a large number of Macedonian officers wedded the daughters of Persian grandees. Of the general mass of the Macedonians 10,000 are said to have followed the example of their officers and taken Asiatic wives; all those were liberally rewarded by Alexander. It is to be noticed that Alexander, already wedded to the princess of Sogdiana, adopted the polygamous custom of Persia; and he even married another royal lady, Parysatis, daughter of Ochus. These marriages were purely dictated by policy; for Alexander never came under the influence of women.

-- Chapter XVIII: The Conquest of the Far East, Excerpt from "History of Greece for Beginners", by J. B. Bury, M.A.

The Greek writers relate that the father of Sandrocottus was a man of low origin, being the son of a barber, whom the queen had married after putting her husband the king to death. He is called by Diodorus Siculus (16.93, 94) Xandrames, and by Q. Curtius (9.2) Aggrammes, the latter name being probably only a corruption of the former. This king sent his son Sandrocottus to Alexander the Great, who was then at the Hyphasis, and he is reported to have said that Alexander might easily have conquered the eastern parts of India, since the king was hated on account of his wickedness and the meanness of his birth. Justin likewise relates, that Sandrocottus saw Alexander, and that having offended him, he was ordered to be put to death, and escaped only by flight. Justin says nothing about his being the king's son, but simply relates that he was of obscure origin, and that after he escaped from Alexander he became the leader of a band of robbers, and finally obtained the supreme power...The name of Sandrocottus is written both by Plutarch and Appian Androcottus without the sibilant, and Athenaeus gives us the form Sandrocuptus (Σανδρόκυπτθς), which bears a much greater resemblance to the Hindu name than the common orthography. (Plut. Alex. 62 ; Justin, 15.4 ; Appian, Syr. 55 ; Strab. xv. pp. 702, 709, 724 ; Athen. 1.18e.; Arrian, Arr. Anab. 5.6.2; Plin. H. N. 6.17.)

-- Sandrocottus, by William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology

The discovery that the Sandrokottos of the Greeks was identical with the Chandragupta who figures in the Sanskrit annals and the Sanskrit drama was one of great moment, as it was the means of connecting Greek with Sanskrit literature, and of thereby supplying for the first time a date to early Indian history, which had not a single chronological landmark of its own. Diodoros distorts the name into Xandrames, and this again is distorted by Curtius into Agrarimes...

According to Eratosthenes, and Megasthenes who lived with Siburtios the satrap of Arachosia, and who, as he himself tells us, often visited Sandrakottos, the king of the Indians...

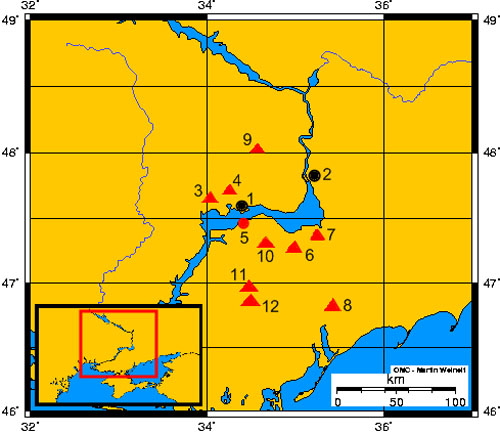

According to Megasthenes the mean breadth (of the Ganges) is 100 stadia, and its least depth 20 fathoms. At the meeting of this river and another is situated Palibothra, a city eighty stadia in length and fifteen in breadth. It is of the shape of a parallelogram, and is girded with a wooden wall, pierced with loopholes for the discharge of arrows. It has a ditch in front for defence and for receiving the sewage of the city. The people in whose country this city is situated is the most distinguished in all India, and is called the Prasii. The king, in addition to his family name, must adopt the surname of Palibothros, as Sandrakottos, for instance, did, to whom Megasthenes was sent on an embassy....

The Indians all live frugally, especially when in camp. They dislike a great undisciplined multitude, and consequently they observe good order. Theft is of very rare occurrence. Megasthenes says that those who were in the camp of Sandrakottos, wherein lay 400,000 men, found that the thefts reported on any one day did not exceed the value of two hundred drachmae, and this among a people who have no written laws, but are ignorant of writing, and must therefore in all the business of life trust to memory. They live, nevertheless, happily enough, being simple in their manners and frugal. They never drink wine except at sacrifices. [This wine was probably Soma juice.] Their beverage is a liquor composed from rice instead of barley, and their food is principally a rice-pottage. [Curry and rice, no doubt.] The simplicity of their laws and their contracts is proved by the fact that they seldom go to law. They have no suits about pledges or deposits, nor do they require either seals or witnesses, but make their deposits and confide in each other. Their houses and property they generally leave unguarded. These things indicate that they possess good, sober sense; but other things they do which one cannot approve: for instance, that they eat always alone, and that they have no fixed hours when meals are to be taken by all in common, but each one eats when he fools inclined. The contrary custom would be better for the ends of social and civil life....

The wild men could not be brought to Sandrakottos, for they refused to take food and died. Their heels are in front, and the instep and toes are turned backwards. [These wild men are mentioned both by Ketesias and Baeto. They were called Antipodes on account of the peculiar structure of their foot, and were reckoned among Aethiopian races, though they are often referred to in the Indian epics under the name Paschadangulajas, of which the [x] of Megasthenes is an exact translation. Vide Schwanb. 68.]

Some were brought to the court who had no mouths and were tame. They dwell near the sources of the Ganges, and subsist on the savour of roasted flesh and the perfumes of fruits and flowers, having instead of mouths orifices through which they breathe. They are distressed with things of evil smell, and 6 hence it is with difficulty they keep their hold on life, especially in a camp.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle

Sir William Jones (1746-1794) deliberately identified 'Sandrocottus" mentioned by the Greeks as #ChandraguptaMaurya and declared that he was the contemporary of Alexander in 327-326 BCE...

Puranas tell us that Chandragupta Maurya ascended the throne by defeating the last Nanda king around 1500 BCE....

Therefore, #Samudragupta was the contemporary of Alexander in 327-326 BCE not Chandragupta Maurya...

The Greek scholars recorded the names of kings of India as Xandrames, and Sandrocottus. Western historians deliberately identified these names with those of Mahapadmananda or Dhanananda and Chandragupta Maurya. Xandrames was said to be the father of Sandrocottus. According to John W. McCrindle, Diodorus distorted the name "Sandrocottus" into Xandrames and this again is distorted by Curtius into Agrammes...

Seleucus Nikator also sent Deimachos on an embassy to Allitrocades or Amitrocades, the son of Sandrocottus. Western historians identified Allitrocades or Amitrocades to be Bindusara, the son of Chandragupta and concocted that Bindusara was also known as "Amitraghata". None of the Indian sources ever referred Bindusara as Amitraghata. Western historians deliberately created the word "Amitraghata" with some sort of resemblance...

Megasthenes described the system of city administration of Pataliputra but there is no similarity between the system described by Megasthenes and the system of city administration given in Kautilya Arthasastra. Megasthenes also stated that there was no slavery in India but Kautilya Arthasastra's Chapter 65 named "Dasakalpa" is solely devoted to the status of slaves among the Aryans and the Mlecchas. Probably, the slavery system that existed during Mauryan era has gradually declined by Gupta era. Thus, Megasthenes cannot be contemporary to Chandragupta Maurya.

Megasthenes not only often visited Palibothra but also stayed in the court of Sandrocottus for a few years. But he did not even mention about Kautilya or Chanakya who was the real kingmaker and also the patron of Chandragupta. No Greek scholar ever mentioned about Kautilya. Therefore, Megasthenes cannot be the contemporary to Chandragupta Maurya.

Greek scholars often mentioned that Sandrocottus was the king of the country called as Prasii (Prachi or Prachya). Pracha or Prachi means eastern country. During the Nanda and Mauryan era, Magadha kings were ruling almost entire India. Mauryan Empire was never referred in Indian sources as only Prachya desa or eastern country. Prachya desa was generally referred to Gupta Empire because Northern Saka Ksatrapas and Western Saka Ksatrapas were well established in North and West India. Megasthenes mentioned that Sandrocottus is the greatest king of the Indians and Poros is still greater than Sandrocottus which means a kingdom in the North-western region is still independent and enjoying at least equal status with the kingdom of Sandrocottus...

The Greek historian Plutarch mentioned that Androkottus (Sandrocottus) marched over the whole of India with an army of 600 thousand men. Chandragupta Maurya defeated Nandas under the leadership of Chanakya. There was no need for him to go on such expedition to conquer the whole of India because he has already inherited the Magadha kingdom of Nandas covering entire India. Actually, it was Samudragupta who overran the whole of India as details given in Allahabad pillar inscription.

According to Greek historians like Justinus, Appianus etc., Seleukos made friendship with Sandrocottus and entered into relations of marriage with him. Allahabad pillar inscription tells us that Samudragupta was offered their daughters in marriage (Kanyopayanadana ... ) by the kings in the North-west region. There is nothing in Indian sources to prove this fact with reference to Chandragupta Maurya...

The Jain work "Harivamsa" written by Jinasena gives the names of dynasties and kings and the duration of their rule after the nirvana of Mahavira. Jinasena mentions nothing about Mauryas but he tells us that Gupta kings ruled for 231 years. Western historians fixed the date of Mahavira-nirvana in 527 BCE which means Mauryas ruled after Mahavira-nirvana but Jaina Puranas and Jaina Pattavalis had no knowledge of Mauryas after Mahavira-nirvana. Thus, Mauryas ruled prior to Mahavira-nirvana. Therefore, Sandrocottus can only be identified with Samudragupta.

If Sandrocottus was indeed Chandragupta Maurya, why do none of the Greek sources mentioned about Asoka, the most illustrious and greatest of Mauryan kings? It is evident that Greek sources had no knowledge of Asoka. Therefore, the ancient Greeks were contemporaries to Gupta kings not Mauryas...

Interestingly, there is no reference of Alexander's invasion in Indian literary sources because it was actually a non-event for Indians...

Strabo once stated:"Generally speaking, the men who have hitherto written on the affairs of India were a set of liars. Deimachos holds the first place in the list; Megasthenes comes next; while Onesikritos and Nearchos with others of the same class, manage to stammer out a few words of truth."...

If Samudragupta is accepted as Sandrocottus the contemporary Indian king of Alexander and the epoch of Saka coronation era in 583 BCE, there will be no conflict in the traditional Indian records and epigraphic records.

-- Who was Sandrocottus: Samudragupta or Chandragupta Maurya?, The Chronology of Ancient India, Victim of Concoctions and Distortions, by Vedveer Arya

I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw in my way, though my proofs must be reserved for an essay which I have destined for the fourth volume of your Transactions. To fix the situation of that Palibothra (for there may have been several of the name) which was visited and described by Megasthenes, had always appeared a very difficult problem, for though it could not have been Prayaga, where no ancient metropolis ever stood, nor Canyacubja, which has no epithet at all resembling the word used by the Greeks; nor Gaur, otherwise called Lacshmanavati, which all know to be a town comparatively modern, yet we could not confidently decide that it was Pataliputra, though names and most circumstances nearly correspond, because that renowned capital extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, while Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and Erannoboas, which the accurate M. D'Anville had pronounced to be the Yamuna; but this only difficulty was removed, when I found in a classical Sanscrit book, near 2000 years old, that Hiranyabahu, or golden armed, which the Greeks changed into Erannoboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was in fact another name for the Sona itself; though Megasthenes, from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately. This discovery led to another of greater moment, for Chandragupta, who, from a military adventurer, became like Sandracottus the sovereign of Upper Hindustan, actually fixed the seat of his empire at Pataliputra, where he received ambassadors from foreign princes; and was no other than that very Sandracottus who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator; so that we have solved another problem, to which we before alluded, and may in round numbers consider the twelve and three hundredth years before Christ, as two certain epochs between Rama, who conquered Silan a few centuries after the flood, and Vicramaditya, who died at Ujjayini fifty-seven years before the beginning of our era.

-- Discourse X. Delivered February 28, 1793, P. 192, Excerpt from "Discourses Delivered Before the Asiatic Society: And Miscellaneous Papers, on The Religion, Poetry, Literature, Etc. of the Nations of India", by Sir William Jones

The terms are interrelated: Seleucus’ receipt of elephants is framed as an exchange (Strabo’s verb is [x], “I take in return”) for the territory or the marriage, and the marriage itself may have functioned as the security and guarantee of the treaty, with the ceded land considered a dowry.22 [ ]

In ancient Greek, diadochos is a noun (substantive or adjective) formed from the verb, diadechesthai, "succeed to," a compound of dia- and dechesthai, "receive." The word-set descends straightforwardly from Indo-European *dek-, "receive", the substantive forms being from the o-grade, *dok-. Some important English reflexes are dogma, "a received teaching," decent, "fit to be received," paradox, "against that which is received." The prefix dia- changes the meaning slightly to add a social expectation to the received. The diadochos expects to receive it, hence a successor in command or any other office.

-- Diadochi, by Wikipedia

Seleucus I Nicator was a Greek general and one of the Diadochi, the rival generals, relatives, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death.

-- Seleucus I Nicator, by Wikipedia

This territory-for-elephants was mutually beneficial. Geopolitically, Seleucus abandoned territories he could never securely hold in favor of peace and security in the east: the treaty and elephants allowed him to turn his attention to his rival, Antigonus Monophthalmus, Syria and the Mediterranean.23 [ ] Chandragupta gained unchallenged expansion into India’s northwest corridor.24 [ ] His gift of elephants may have alleviated the burden of fodder and the return march. Ambassadors and caravans, not conquering armies, would now pass through the intermediate zone. Moreover, the fact and terms of the treaty were a recognition of equal, royal status for kings who lacked the legitimacy of appointment or inheritance. It is even possible that Seleucus used the occasion of this treaty – a wedding on the Indus? – for formally completing his long march from satrap to king.25 [ ]

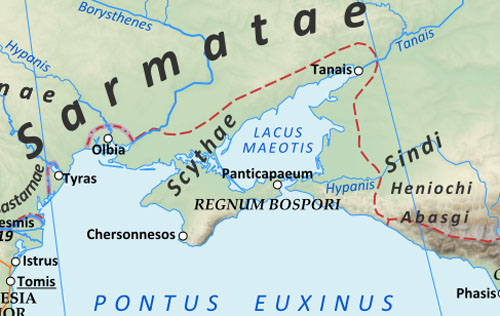

The Treaty of the Indus was a constitutive act of the Hellenistic state system, creating the Seleucid empire’s eastern frontier by transferring land out of Seleucus’ control. This act of delimitation marked the boundary of Seleucid power and sovereign claims. As such, it was a radical departure from two centuries of Achaemenid and Alexandrian universalist pretensions. Persian kings had recognized no independent, equal monarchy to its east, and in Achaemenid geography, as far as it can be grasped through its Herodotean and Ctesian refractions, the world simply faded into nothingness beyond Persia’s imperial possessions in India. The eastern boundary of Alexander’s conquests was more problematic. From its outset, his anabasis had been a relentless march toward the eastern edge of the world; he was halted only at the Hyphasis river by an army mutiny, a form of internal historical agent entirely consistent with his empire’s effacement of external powers. By contrast, the termination of Seleucus’ eastern conquest was externally motivated. Seleucus, like Alexander, crossed the river Indus (a metonymy for royal invasion),26 [ ] but he met his equal, Chandragupta. In other words, diplomacy is to bounded political space what mutiny is to universal political space. The new world order’s multicentrism results in a historical narrative of multiple agency.

The terms of the treaty, no doubt much negotiated, indicate an economy of exchange. Space is convertible. Seleucid power was not yet embedded in a defined territory: its eastern lands function, like Chandragupta’s elephants, as one resource of the kingdom. The very fact of the treaty’s territorial clause indicates that land was still a possession to be negotiated over and divided up unproblematically. Moreover, the treaty created new spatial units, ignoring the boundaries of ethnic communities and the historical precedents of Achaemenid and Alexandrian imperialism.

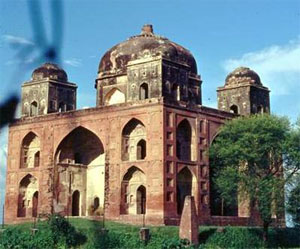

The Treaty of the Indus satisfactorily secured the eastern periphery of the Seleucid empire and the western periphery of the Mauryan empire. The Seleucid frontier with the Indian kingdom, settled once and for all, never became an important location for the legitimating of monarchic identity through territorial claims or military aggression: there was no attempt to reconquer the ceded territories or to redraw the border, a clear contrast to the ping-pong regions of Coele Syria and Asia Minor. Likewise, the Mauryan kingdom, satisfied with its territorial gains in the northwest, appears to have turned its attentions eastward and southward.27 [ ] Friendly contacts were maintained by Seleucid diplomats resident in the Mauryan capital. Pataliputra (Gr. Palimbothra, mod. Patna), including, as we will see, Seleucus I’s envoy Megasthenes, and it is very probable that Chandragupta’s representatives were attached to the Seleucid court; his grandson Ashoka certainly sent them.28 [ ] Relations continued into the kingdoms’ second generation: Strabo reports that Megasthenes was replaced by Deimachus, ambassador of Seleucus’ successor, Antiochus I, to Chandragupta’s successor, Amitrochates (Bindusara).29 [ ]

In the new context of permanent, amicable diplomacy opened by the Treaty of the Indus, the land-for-elephants agreement was reperformed as regular, ceremonial gift-giving, exchanges that generated solidarity and renewed equality of rank, as in the Bronze Age “Great Powers” system of Amarna diplomacy,30 [ ] rather than functioning as unidirectional signs of subservience, as in Persepolitan imperialism.31 [ ] The Hellenistic historian Phylarchus, in a passage preserved by Athenaeus, indicates that Chandragupta sent Seleucus a gift package, including Indian aphrodisiacs.32 [ ] The incense trees that Seleucus attempted to import by sea from India33 [ ] and the tigers he sent to the Athenians (see Chapter 4) may well have originated as Chandragupta’s diplomatic gifts. Athenaeus repeats Hegesander’s report that Chandragupta’s son, Amitrochates (Bindusara), requested from Antiochus I wine, figs, and a sophist. Antiochus responded, [x], “The figs and sweet wine we will send you, but it is not lawful among the Greeks for a sophist to be sold.”34 [ ] This delightful passage demonstrates not only that the diplomatic gift exchange between the Seleucid and Mauryan kings was well known and recorded by contemporary authors but also that it was imagined to be open to curiosity, request, negotiation, and refusal: giving is complemented by keeping.35 [ ] The frequency with which the exchanged gifts appear to be of an ethnographic character may be a consequence of our sources’ paradographical preferences, but the sending of figs eastward or tigers westward could only reinforce the new world order’s assertion of independent, essentially external territories.

After Alexander’s conquest of Bactria and Sogdiana, the Indian satrapy was the only province of the Persian empire into which he had not carried his arms.Satraps were the governors of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires. The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with considerable autonomy. The word came to suggest tyranny or ostentatious splendour. A satrapy is the territory governed by a satrap.

-- Satrap, by Wikipedia

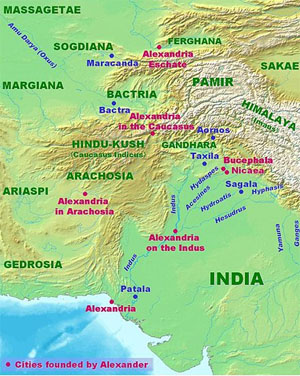

Of this province he must have gained some valuable knowledge from Sisikottos (Sasigupta), the Indian mercenary leader who transferred his services from Bactria to her conqueror. Alexander also received an embassy in Sogdiana from Omphis (Ambhi) of Takshasila (Taxila) which offered him the alliance of the Indian prince and sought the foreigner’s aid against his powerful neighbour Porus, the first recorded instance of an Indian seeking foreign aid against fellow Indians....

Alexander then proceeded to Nikaia (Greek for ‘city of victory’), a place that lay most likely on his route to the river Kabul. Here he offered a sacrifice to the goddess Athena, and met an Indian embassy headed by the king of Takshasila which ‘brought him such presents as are most esteemed by the Indians’ and gave him also all the elephants they had with them, twenty-five in number....

After the subjugation of the Aspasians, Alexander moved, according to Curtius, to the city of Nysa; Arrian records the visit in detail, but gives no indication of the position of Nysa, and is openly sceptical not only of the legendary details, but of the existence of the city itself. The inhabitants of Nysa offered no resistance, but sent an embassy with presents and claimed kinship with the Greeks on the score that their city had been founded by Dionysus and named after his nurse, Nysa, and that the Nysans were the descendants of his followers; the mountain near the city also bore the name Meros (thigh) because Dionysus grew, before his birth, in the thigh of Zeus. Nysa had remained a free city with its own laws ever since, and Alexander should permit them to continue as they were. ‘It gratified Alexander to hear all this' from Akuphis, the leader of the Nysan deputation, and he was not inclined to be too critical of legends that were pleasing to the ears of his soldiers, and promised him the glory of excelling the achievements of Dionysus. So he offered a sacrifice to his divine predecessor and confirmed his colony in the enjoyment of its ancient laws and liberty as an aristocratic republic....

Alexander now appointed Nicanor satrap of the country west of the Indus, and received the submission of Peucelaotis (Pushkalavati), the ancient capital of Gandhara, stationing a garrison of Macedonian soldiers in the city under the command of Philip....

When Alexander reached the bridge at Ohind, at the end of sixteen marches, he gave his army a rest of thirty days, entertaining them with games and contests. Here he was met by an embassy from Ambhi of Takshasila who had recently succeeded to his father’s throne, but was awaiting the arrival of Alexander to assume sovereignty. The embassy brought presents consisting of 200 talents of silver, 3,000 fat oxen, 10,000 sheep or more and 30 elephants; a force of 700 horsemen also came to the assistance of Alexander from the same prince and brought word that Ambhi surrendered into Alexander’s hands his capital Takshasila, ‘the greatest of all the cities between the river Indus and Kydaspes’....

As the invader approached Takshasila a strange incident occurred. When he was at a distance of some four miles from the city, he was met by a whole army drawn in battle order and elephants ranged in a line; Alexander suspected treachery and instructed his troops to prepare for a battle; but Ambhi seeing the mistake made by the Macedonians, left his army with a few friends and contrived to explain to Alexander, with the aid of an interpreter, that he meant not to fight, but to honour his foreign ally whose protection he had been soliciting for so long and with so much persistence. He surrendered himself, his army and kingdom into the hands of Alexander, and got them back as his favoured protege....

Alexander was entertained in Takshasila for three days with lavish hospitality, and on the fourth day he and his friends received presents of golden crowns and eighty talents of coined silver (Curtius). In his turn Alexander showed his gratification by sending to Ambhi a thousand talents from his spoils of war ‘along with many banqueting vessels of gold and silver, a vast quantity of Persian drapery, and thirty chargers from his own stalls, caparisoned as when ridden by himself'. Thus did a fraction of the loot from the store-houses of the old Persian kings find its lodgement in the palace of Takshasila....it secured for him an additional force of five thousand men and the unfailing loyalty of a most useful ally. Embassies from Indian princes met Alexander here with presents and declared their submission to him; even Abhisares of the hill country sent his brother....

He posted Philip, the son of Machatus, at the head of a garrison, as satrap of Takshasila and its neighbourhood, and began his march to the Jhelum with his own army and the Taxilan contingent of 5,000 men commanded by their king in person....

The generals soon developed a stout opposition to further advance into India, and Seleucus, who had seen something of the Indian elephants in the battle of the Jhelum, when he became king, was ready to cede whole provinces in order to secure an adequate number of these noble animals for his army....

Porus himself, mounted on a tall elephant, not only directed the movements of his forces but fought on to the very end of the contest; he then received a wound on his right shoulder, the only unprotected part of his body, all the rest of his person being rendered shot-proof by a coat of mail remarkable for its strength and closeness of fit; he now turned his elephant and began to retire....at last Meroes (Maurya?), an old friend of Porus, persuaded him to hear the message of Alexander....Alexander, who was the first to speak, requested Porus to say how he wished to be treated. ‘Treat me, O Alexander! as befits a king’ was the answer of Porus. Pleased with it, Alexander replied; ‘For mine own sake, O Porus! thou shalt be so treated, but do thou, in thine own behalf, ask for whatever boon thou pleasest' to which Porus said that everything was included in what he had asked. Alexander not only reinstated Porus in his kingdom, but added to it territory of still greater extent. Thus the Paurava took his place in the world-empire of Alexander for a time by the side of his old enemy, the king of Takshasila. Possibly Alexander meant that they should be a check on each other....

When Alexander took the field again with a select division of horse and foot, he invaded the land of the Glausai or Glauganikai (Glauchukayanas) as they were called, a free tribe on the western bank of the Akesines (Chenab) living in thirty-seven cities of between five and ten thousand inhabitants each and a multitude of villages. These people were now placed under the rule of the Paurava against whom they had maintained their independence for so long. From here Taxiles, now reconciled to Porus, was sent back to his capital. The Raja of Abhisara, who could not join the Paurava before the battle of the Jhelum, now sent his brother with forty elephants and a money present to renew the protestations of his friendship to Alexander and offer the surrender of himself and his kingdom into his hands; Alexander demanded the presence of Abhisares in person, adding that if he failed to come Alexander might go himself with his army to look for him. Envoys came also from another Porus across the Chenab, perhaps a relative, but no friend, of the great Paurava....

Alexander now pressed on to the next river, Hydraotes (Ravi), ‘not less in breadth than the Akesines, but not so rapid', leaving garrisons at suitable places along his route to secure his communications. From the banks of that river he despatched Hephaestion with enough troops into the territory of the younger Porus, who had abandoned his country with a handful of followers when he learned of the esteem of Alexander for the other Paurava. Hephaestion was to reduce the territory of the fugitive Porus and of all the independent tribes on the banks of the Ravi, and add it to the kingdom of the great Paurava...

Within two days of his crossing the Ravi, Alexander had received the submission of Pimprama (unidentified), the city of the Adraistai (Adhrshtas or, according to Jayaswal, Arishtas), But the Kathaians of Sangala camped under shelter of a low hill outside the city and offered a determined resistance from behind a triple barricade of wagons. Finding his cavalry of no avail against the enemy, Alexander led the infantry on foot and after much hard fighting, compelled the Indians to seek refuge behind the city walls. Alexander now closely invested the city, and Porus joined him with a force, of 5,000 Indians and several elephants...

While he was encamped on the Beas, Alexander was told by a chieftain named Bhagala (Panini knew the name) about the extent and power of the Nanda empire, and Porus confirmed his statements. Such information whetted Alexander’s eagerness to advance further; but his troops, especially the Macedonians, had begun to lose heart at the thought of the distance they had travelled from their homes and the hardships and dangers they had been called upon to face after their entry into India. And at the Beas the army mutinied and refused to march further....

The country west of the Beas was committed to the charge of Porus—‘Seven nations in all, containing more than 2,000 cities’. While he was making preparations on the Chenab for his voyage to the sea, he received another embassy from Abhisares accompanied by Arsakes, ruler of the neighbouring country of Urasa; Abhisares himself was ill and could not come, as the ambassadors Alexander had sent to him attested. Abhisares was now made satrap of his own dominions and Arsakes placed under him.

-- Chapter II: Alexander's Campaigns in India, Excerpt from "Age of the Nandas and Mauryas", by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri