by Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/25/20

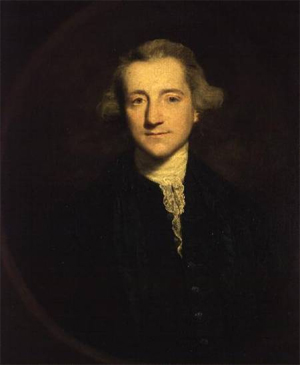

Henry Vansittart

Portrait, oil on canvas, of Henry Vansittart (1732–1770) by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Governor of the Presidency of Fort William

In office: 1762–1764

Preceded by: Robert Clive [John Zephaniah Holwell]

Succeeded by: Robert Clive

Personal details

Born: 3 June 1732, Bloomsbury, Middlesex, England

Died: 1770 (aged 37), Presumed to have died at sea in the Mozambique Channel

Nationality: British

Alma mater: Reading School; Winchester College

Henry Vansittart (3 June 1732 – 1770) was the English Governor of Bengal from 1759 to 1764.

Life

Vansittart was born in Bloomsbury in Middlesex, the third son of Arthur van Sittart (1691–1760), and his wife Martha, daughter of Sir John Stonhouse, 3rd Baronet.[1] His father and his grandfather, Peter van Sittart (1651–1705), were both wealthy merchants and directors of the Russia Company.

The Muscovy Company (also called the Russian Company or the Muscovy Trading Company Russian: Московская компания, romanized: Moskovskaya kompaniya) was an English trading company chartered in 1555. It was the first major chartered joint stock company, the precursor of the type of business that would soon flourish in England and finance its exploration of the world. The Muscovy Company had a monopoly on trade between England and Muscovy until 1698 and it survived as a trading company until the Russian Revolution of 1917. Since 1917 the company has operated as a charity, now working within Russia.

-- Muscovy Company, by Wikipedia

Peter, a merchant adventurer, who had migrated from Danzig to London about 1670, was also a director of the East India Company. The family name is taken from the town of Sittard in Limburg, the Netherlands. They settled at Shottesbrooke in Berkshire.

Educated at Reading School and at Winchester College, Henry Vansittart joined the society of the Franciscans, or the Hellfire Club, at Medmenham. His elder brothers, Arthur and Robert, were also members of this fraternity.[2]

Hellfire Club was a name for several exclusive clubs for high society rakes established in Britain and Ireland in the 18th century. The name is most commonly used to refer to Sir Francis Dashwood's Order of the Friars of St. Francis of Wycombe. Such clubs were rumoured to be the meeting places of "persons of quality" who wished to take part in socially perceived immoral acts, and the members were often involved in politics. Neither the activities nor membership of the club are easy to ascertain, for the clubs were rumoured to have distant ties to an elite society known only as The Order of the Second Circle....In the second circle of Hell are those overcome by lust. These "carnal malefactors" are condemned for allowing their appetites to sway their reason. These souls are buffeted back and forth by the terrible winds of a violent storm, without rest. This symbolizes the power of lust to blow needlessly and aimlessly: "as the lovers drifted into self-indulgence and were carried sway by their passions, so now they drift for ever. The bright, voluptuous sin is now seen as it is – a howling darkness of helpless discomfort." Since lust involves mutual indulgence and is not, therefore, completely self-centered, Dante deems it the least heinous of the sins and its punishment is the most benign within Hell proper.

-- Inferno (Dante), by Wikipedia

Lord Wharton, made a Duke by George I,[9] was a prominent politician with two separate lives: the first a "man of letters" and the second "a drunkard, a rioter, an infidel and a rake"...

At the time of the London gentlemen's club, where there was a meeting place for every interest, including poetry, philosophy and politics, Philip, Duke of Wharton's Hell-Fire Club was, according to Blackett-Ord, a satirical "gentleman's club" which was known to ridicule religion, catching onto the then-current trend in England of blasphemy...The supposed president of this club was the Devil...

According to at least one source, their activities included mock religious ceremonies and partaking in meals containing dishes like "Holy Ghost Pie", "Breast of Venus", and "Devil's Loin", while drinking "Hell-fire punch". Members of the Club supposedly came to meetings dressed as characters from the Bible...

After his Club was disbanded, Wharton became a Freemason, and in 1722 he became the Grand Master of England...

Dashwood founded the Order of the Knights of St Francis in 1746, originally meeting at the George & Vulture.

The club motto was Fais ce que tu voudras (Do what thou wilt), a philosophy of life associated with François Rabelais' fictional abbey at Thélème and later used by Aleister Crowley...

The first meeting at Sir Francis's family home in West Wycombe was held on Walpurgis Night, 1752...

According to Horace Walpole, the members' "practice was rigorously pagan: Bacchus and Venus were the deities to whom they almost publicly sacrificed; and the nymphs and the hogsheads that were laid in against the festivals of this new church, sufficiently informed the neighborhood of the complexion of those hermits." Dashwood's garden at West Wycombe contained numerous statues and shrines to different gods; Daphne and Flora, Priapus and the previously mentioned Venus and Dionysus...

Legends of Black Masses and Satan or demon worship have subsequently become attached to the club, beginning in the late Nineteenth Century. Rumours saw female "guests" (a euphemism for prostitutes) referred to as "Nuns". Dashwood's Club meetings often included mock rituals, items of a pornographic nature, much drinking, wenching and banqueting...

The Phoenix was established in honour of Sir Francis, who died in 1781, as a symbolic rising from the ashes of Dashwood's earlier institution. To this day, the dining society abides by many of its predecessor's tenets. Its motto uno avulso non deficit alter (when one is torn away another succeeds) is from the sixth book of Virgil's Aeneid and refers to the practice of establishing the continuity of the society through a process of constant renewal of its graduate and undergraduate members.

-- Hellfire Club, by Wikipedia

In 1745, at the age of thirteen, he entered service of the East India Company as a writer and sailed for Fort St David in Madras.[3] Here he showed himself very industrious, made the acquaintance of Robert Clive and rose rapidly from one position to another, although he spent three years back in England from 1751.

He returned to India in 1754 and became a member of the Council of Madras in 1757. He helped to defend the city against the French in 1759,[2] and was appointed to replace Clive, on Clive's recommendation, as President of the Council and Governor of Fort William in Bengal in November 1760.[3]

Governor Clive departing for Europe the 8th of February, 1760, Mr. Holwell succeeded by his rank to the government; the established committee entrusted with the conduct of all political occurrences, with the country government, consisted of the President, Peter Amyatt, Esq; Major Caillaud, W. B. Sumner, Esq; and W. Macguire, Esq. The Major and Mr. Amyatt absent, the one in the field, the other chief at Patna...

To the Honorable J. Z. Holwell, Esq; President and Governor of Fort William

Camp Sbabsadapore, Feb. 27, 1760. H

Sir,

I been honored with your obliging favor of the 15th instant; you may be assured of finding in me a punctual correspondent, both from inclination and duty. T

The part of your letter, Sir, with regard to Roy Doolub, I have answered fully in the general letter which accompanies this. -- I should have first wrote on the subject, had you not prevented me; and am almost convinced, that, on further examination, we shall find that both your suspicions and mine are true and just: indeed the Letter to the Shaw Zadda, of which I send the copy, would be quite sufficient to condemn him, were it not that there is a possibility of its being formed by the Nabob on purpose; who is, from principle, very capable of doing that, or any other infamous action to gain his ends. -- I shall, however, suspend my judgment, until your examination is over. -- The precautions you have taken were highly judicious; for though the proofs against him may not, on trial, appear so clear as we could with for our satisfaction; yet he is still a person to be suspected, and of consequence cannot be too narrowly or strictly watched.

Your opinion, with regard to the Nabob's return to the Capital, agreed perfectly with mine; I had advised him to that step before the receipt of your letter, and have since enforced it on your judgment: -- he may easily, if he pleases, put an end to this beginning of trouble, if he will pursue the proper methods, and pay them their chout; but indeed, so dilatory is his conduct in every respect, and particularly where payments of money are to be made, that I suppose he will put it off, until they come with such a force as will oblige him to it, but that not until they have done as much damage to the country as will amount to double their tribute regularly paid.

The more I see of the Nabob, the more I am convinced, that he must be ruined in spite of all our endeavors, if he doth not alter his present measures. -- He is neither loved nor feared by his troops or his people; he neglects securing the one by the badness of his payments, and he wants spirit and steadiness to command the other. -- As no one knows him better than you, Sir, no one is more proper to give him the necessary advice on the occasion; nor can you too forcibly or frequently represent to him, the fatal consequences, if he persists in his folly. Believe me, Sir, with truth and respect,

Your obedient and obliged humble Servant,

J.C....

To the Honorable John Z. Holwell, Esq; President and Governor of Fort William.

Camp at Burpore, 6th April, 1760.

Sir,

My last was dated the 24th Inst. Yesterday we marched about five corse, and this day three; which brought us so near the enemy as to expect they would come and give us battle; but finding about noon they did not advance, I desired the Nabob to march on towards them, but he said the day was too far spent, and his people too much fatigued. The Prince is encamped near the Damoudah river, about three corse from us and I hope tomorrow we shall bring him to an engagement. The Maharattas are encamped very near him. I have the honor to subscribe myself, with the most perfect respect and esteem, Sir,

Your most obedient and most humble servant,

J. C....

To the Honorable J. Z. Holwell, Esq; President and Governor of Fort William.

Camp at Dignagur, April 15, 1760.

Sir,

In order to come at the truth, with regard to the Nabob's Arzgee to the Prince, Mr. Hastings had recourse to the Nabob's Persian writer; a man who hath, on many occasions, given him proofs of attachment and fidelity. The moment he set his eyes on the paper, he declared it to be a forgery. May I beg leave to refer you to Mr. Hastings for the reasons he gave for it; as that Gentleman's knowledge in the language will enable him to give you a clearer idea of these distinctions in address and style of their letters, than I can pretend to. For my part, I own, after Mr. Hastings had repeated them to me, they were so satisfactory as to convince me the probability of its being a forgery was greatly in the Nabob's favor.

Two days before I received your letter, Sir, the Nabob and his son were with me, and I found the old man big with something that he did not know well how to begin breaking to me. I helped him forward all I could by those kind of assurances which often open the hearts of men; and he then told me he had wrote to the Prince, and had received an answer, such a one as gave him hopes, with other circumstances, that the Prince might be inclinable to treat and put himself perhaps in his power; but that he knew he (the Prince) would not do this, without I would be security for his safety. The Nabob was desirous to know, in such a case, how I would act; but the main drift of the discourse was, to find out how far I would be consenting to give him an opportunity of displaying the true eastern system of politics, by cutting him off. You may easily, Sir, guess my answer, that I was ready to do every thing for his service consistent with the honor of my country, and the sacred regard we gave to our word; and besides, if the Prince made any address to me on this subject of security, I must first have your orders and instructions in this affair. And thus the conversation ended.

I made it my business afterwards to enquire among some of the Nabob's people, on what grounds he founded these hopes of getting the Prince in his power? but they all assured me, as I suspected, that they were no more than the idle reports of some of his minions, who knew such stories would be well received and credited, and so found advantage in flattering his foolish hopes.

It is a very unfortunate circumstance that we have to do with a weak man, who neither from principle nor merit deserves the dignity of the station in which we have put him, and in which he would not remain twenty-four hours, if we were to withdraw our protection from him, and on which he so much depends, that I am obliged to give him a guard of Seapoys for the safety of his person. It doth not appear to me, however, in justice or in reason, that we ought to support him in the pursuit of unjustifiable measures; such as he follows in regard to not discharging the vast arrears due to his troops, who to a man have publicly declared, they will not draw their swords in his cause, and that only their fears of us prevent their using them against him. The consequence will be, as to his part, that while he is not afraid of his head he never will satisfy them; and to us, that though we may protect him from immediate danger to his person, we must relinquish the hopes of seeing the country free from troubles, while he keeps a body of troops that he will not pay regularly, and over whom he consequently hath no command. This rotten system still we might in some measure support, were we always assured none but the country powers would disturb us: but it is more than probable that the French or Dutch, if not both, may some time or other renew their attempts to be concerned, and with how much the more probability of success from the distracted state of the country while the Nabob continues to govern it so ill.

The first opportunity I propose representing all this to him in the strongest light I possibly can; and should our opinions agree, I should take it as a favor if you would enclose a letter from yourself to him, on the subject; I will deliver it, and take that opportunity as the best to try what can be done by working on his fears, the only way indeed I am convinced of managing him to our own advantage and his good. In particular, Sir, you will be pleased to enforce the payment of his troops, by hinting, that if he delays it, I have your orders not to prevent them taking their own measures.

To-morrow Captain Knox's detachment marches. The Prince is certainly gone back, and we talk of nothing but the pleasures of the great Rumnah first, and then of an expedition against the Purnea Nabob to conclude the campaign. As this last step is absolutely necessary, I shall do all in my power to prevent the former obstructing it; with what success, we shall soon know. I am, Sir,

Your most obedient and most humble servant,

J. C....

To the Honorable J. Z. Holwell, Esq; President and Governor of Fort William.

Camp at Balkissens Gardens, 29th May, 1760.

Sir,

I am honored this day with your favor of the 24th instant. My last letters of the 24th, and those of yesterday, of the 28th, contain all I can urge in favor of our return to Patna with the young Nabob -- you seem also convinced of the necessity of it, since the receipt of Mr. Amyatt's letters: I shall be glad to find it further confirmed by the sentiments of the Select Committee.

I am not master enough of the subject, to know how the Company's investment of Salt-petre will be so much hurt this year; and that you fear succors will arrive too late, to prevent much mischief; but this I am very confident of, that if we do not send succors, the whole province may be lost, and many years investments to come.

I will endeavor now, Sir, to reply as fully as I can to the subject on which you desire so earnestly to know my sentiments; and hope what I have to say will so fully satisfy you, that I need not at least leave the army, until the campaign is quite concluded, as I think it cannot be done without prejudice to our affairs.

Bad as the man may be, whose cause we now support, I cannot be of opinion that we can get rid of him for a better, without running the risk of much greater inconveniencies attending on such a change, than those we now labor under. -- I presume, the establishing tranquility in these provinces would restore to us all the advantages of trade we could wish, for the profit and honor of our employers; and I think we bid fairer to bring that tranquility about, by our present influence over the Suba, and by supporting him, than by any change which can be made. -- No new revolution can take place without a certainty of troubles; and a revolution will certainly be the consequence, whenever we withdraw our protection from the Suba: -- we cannot in prudence neither, I believe, leave this revolution to chance -- we must in some degree be instrumental to bringing it about. -- In such a case, it is very possible we may raise a man to the dignity, just as unfit to govern, as little to be depended upon, and in short, as great a rogue as our Nabob, but perhaps not so great a coward, nor so great a fool, and of consequence much more difficult to manage. -- As to the injustice of supporting this man, on account of his cruelties, oppressions, and his being detested in his government, I see so little chance, in this blessed country, of finding a man endued with the opposite virtues, that I think we may put up with these vices, with which we have no concern, if in other matters we find him fittest for our purpose.

As to his breach of his treaty, by introducing the Dutch last year, that was never so clearly proved, I believe, but as to admit of some doubt; -- Colonel Clive, before he left the country, seemed satisfied that what was suspicious in his conduct in that affair, proceeded not from actual guilt, but from the timidity of his nature. -- But if we still suspect him from further circumstances, we always have it in our power to put it to the test at once, by making him act as he ought, whether he will or no.

With regard to drawing our swords against the lawful Prince of the country; no man can more pity his misfortunes than I have done, nor would any one be more willing and happy to be instrumental in assisting him to recover his just right; -- but such a plan is not the thought of a day, nor the execution of it the work of a few months; -- there is a powerful party still remains; -- the Vizier, with the Maharattas and Jutes, who, notwithstanding the constant success of Abdallah against them, still make head against him; and such are their resources and their numbers, that I believe they will at last oblige the Patans to leave the country; for though they cannot beat them fairly out of the field, they bid fair to starve them out of the country.

You have, no doubt, received advice from Mr. Hastings, that Abdallah hath sent orders to the several powers, to acknowledge the Prince King of Indostan, by the name of Shaw Allum; -- rupees are struck by his order at Bannarras and Lucknow, in that name; -- orders are also given to Sujah Dowlatt, to accept the post of Vizier; and our Nabob hath got, it is said, instructions to acknowledge him, and pay him the obeisance due to the King of Kings, as he is styled.

If we were perfectly sure Abdallah would remain, as he says, until he saw the Prince well fixed on the throne, and the peace and tranquility of the country restored, we might, I think, all joined together, be a match for the Maharattas; -- but we must be well assured that Abdallah will heartily enter, and when entered, will firmly support the cause: -- for should this appointment of his be no more (as it is possible) than a finishing stroke, to end his expedition with the eclat of having given us a Mogul, and when a certain number of the country powers had entered into the alliance, he should think of a return to his own country, and leave us to fight it out with the other contending party, I fear the Vizier and the Maharattas would be too strong for those who remained of the alliance, supposing them to be the Ruellahs, and Sujah Dowlatt, and the Nabob of Bengal. -- However, supposing all this should take place, why may it not be done with our Nabob in our hand, still his friends and his protectors?

I am this instant favored with yours of the 25th; and I find by your postscript, that your opinion and mine, with regard to the Prince, do not differ much. I have no objections to follow the plan you propose: -- let Mr. Hastings sound the old Nabob, and I will go to work with the young one, who joins me this day.

We may continue our march on to Patna. -- The rains will give us time to negotiate, to see we go on sure grounds, and make such a plan of the alliance, as will do us honor, and be an advantage to our country and our employers; -- but let us not abandon the Nabob. -- Besides the reasons I have urged above, one more still remains, which I believe will have some weight, and make us cautious how we attempt, without very strong and urgent reasons, any change in the present system.

You are well acquainted, Sir, with the cause which first gave rise to the present share of influence which we enjoy in this part of the Mogul's empire: -- a just resentment for injuries received, was the first motive which induced us to make a trial of our strength; -- the case with which we succeeded enlarged our views, and made us cheerfully embrace all opportunities of increasing that interest and influence, both on account of the advantages which accrued from it to the Honorable Company, as likewise the hopes that it might in time prove a source of benefit and riches to our country. -- Such were, 1 believe, the motives of Colonel Clive's actions during his administration; such, I believe, were the views of the Honorable Company, when they solicited and obtained Colonel Coote's regiment from the Government; and such, I am certain, is the plan which the Colonel proposes, on his return, to pursue and to support, in hopes to convince the Ministry and the Company, as he is convinced himself, that if they please to support his project, it will prove of the greatest advantage to the public.

If I have stated our situation right, it follows, I believe, of course, that we are bound with vigor to work on the same plan, to act on the same principles, and to keep up the system as perfect and entire as it was left in our hands; that whatever resolutions the Nation or the Company may come to, on Col. Clive's representations, they may not be disappointed, by finding here (at least through our faults) any very material change in our situation, power, or credit.

One word more. All we can wish to do is, not to suffer the Nabob to impose on us, and to check every beginning of an independence he may endeavor to assume: -- let us consult and improve on every occasion that offers, the honor and advantage of our employers, and the increase of their trade and credit; and not let them suffer any additional expense, on account of pursuing any plan, or supporting any system whatever. -- By acting thus, I think we cannot err; we run at least no risk; and I believe the Company's affairs may be conducted by us under this Suba, as much to their advantage and credit, as any other whom a revolution may place in the government.

Enclosed, I have the honor to send Mr. Amyatt's last letter, received this morning. We have had, as you will see, another brush with the Prince's troops, and with great success: however, if the other plan goes on, we must put an end to this fighting system, and talk coolly on affairs. -- I shall expect the favor of your opinion with great impatience; and have the honor to assure you that I am, with perfect respect and esteem,

Sir, your most obedient and most humble servant,

JOHN CAILLAUD

-- India Tracts, by Mr. J. Z. Holwell, and Friends.

After the departure of Colonel Clive, the delicacy that he had used towards him was entirely thrown aside. His successor in the government [John Zephaniah Holwell], who had been particularly instrumental in bringing down Sou Rajah Dowla, and consequently in occasioning the first revolution in Bengal, had arrived at his new dignity contrary to the intention of his constituents, and entirely through the accident of a number of his seniors going home at this time in disgust. Being blessed with a genius uncommonly fertile in expedients for raising money, and further unclogged by those silly notions of punctilio [a fine or petty point of conduct or procedure], which often stand in the way betwixt some people and fortune, he had projected and put in practice several inferior maneuvers; but this Chef d'Ouevre [Masterpiece], this master scheme, though formed almost as soon as he came to power, time did not allow him to have the honor of executing. Being formed, however, we may imagine, that under such a governor, daily mortifications, and in various shapes, were not wanting to this ill-starred Nabob. The prince who depends on the will of a superior, ungenerous and incapable of humane or delicate sentiments, is in a more mean and wretched state, than he who depends on a common prostitute for his daily food. Our Nabob quickly found himself reduced to less than the name of prince, insulted by the most contemptuous flights of those whom he called his allies, and who, to pave the way to the projected change, embroiled his affairs, and used all other means in their power to render him odious; despised, reviled, and cursed even to his face by his own subjects, who laid to his charge all the miseries they suffered by war, all the hardships and injuries to which they had been subjected by foreigners, into whose hands he had resigned the substance, on condition he might enjoy the shadow of government; his very domestics treated him with contempt and neglect. His son, who had acted as his general, was suddenly taken from him. This active young prince in the midst of his own, and the English camp, was most singularly struck by lightening. [!!!]

About four months after the departure of colonel Clive, a gentleman from Madrass arrived at Calcutta, to take upon him, by order of the directors, the government of their affairs in Bengal. It must here again be acknowledged, that the gentlemen in the direction, showed they had so little intention, that the accidental governor [John Zephaniah Holwell] should have ever come to that trust, that they now removed him to be the seventh in council. Being endued however in a very high degree with what in some is called address, enforced by a great share of plausibility in argument, he found these talents of singular use to him on this occasion. His grand plan being now almost ripe for execution, could not be concealed from his successor [Henry Vansittart]. He wavered some days about continuing in the service of his masters in that degraded rank. During this space it may be imagined, that he was employed in using his influence to prevail on the new governor, who was a stranger there, to adopt his views. At last this person [John Zephaniah Holwell], who had been hitherto but slightly esteemed by his successor, was by him taken into the most intimate favor and confidence, and admitted into the secret committee, which is composed of a few select members of the council there. This was but a bad omen for the unfortunate Nabob, as from this very symptom we may conclude, that the scheme and measures of the former, were now embraced by the present governor. But it does not redound much to the honor of this degraded governor [John Zephaniah Holwell], nor plead greatly in favor of the disinterestedness of his views, that after such a stigma, such a mark put upon him by his superiors, he could, (though during his short government he had acquired a handsome fortune) submit to serve them in the seventh place, after having been in the first. However, he had the spirit to remain in it no longer, than till he had fairly packed off the then governor on the execution of his plan, and on that very day he resigned.

-- Reflections on the Present State of our East-India Affairs; With Many Interesting Anecdotes Never Before Made Public, by Gentleman Long Resident in India

He arrived in Bengal in July 1760, finding himself in a difficult political position, including a serious lack of funds. He deposed the Nawab of Bengal, Mir Jafar, and replaced the Nawab with the Nawab's son-in-law, Mir Kasim, which increased the influence of England in the province. Vansittart was, however, less successful in another direction. Practically all the company's servants were traders in their private capacity, and as they claimed various privileges and exemptions this system was detrimental to the interests of the native princes and gave rise to an enormous amount of corruption. Vansittart sought to check this, and in 1762 he made a treaty with Mir Kasim, but the majority of Vansittart's council were against him and in the following year this was repudiated. Reprisals on the part of the subadar were followed by war and, annoyed at the failure of his pacific schemes, Vansittart resigned on 28 November 1764 and returned to England.[3]

To defend his conduct in Bengal, Vansittart published three volumes of papers as A Narrative of the Transactions in Bengal from 1760 to 1764 (London, 1766).[2] His conduct was attacked before the board of directors in London, but events seemed to prove that he was in the right, and in 1769 he became a director of the company. In 1768 he had been elected to a seat in Parliament for Reading.[3]

Clive had returned to India and exposed the rampant corruption. Vansittart, Luke Scrafton, and another official, Francis Forde, were sent to India to examine the administrative problems and reform the whole government in India. The mission left England in September 1769, visited Cape Town where they were last reported, embarking, on 27 December 1769, but the ship in which they sailed, the frigate Aurora, was lost at sea, apparently foundered with all hands.[2][3][4] The captain had decided to navigate the Mozambique Channel, despite bad weather.[5]

Sailing from Madagascar to South Africa is technically challenging. The Mozambique Channel separating them is famously dangerous, in particular for the effect of gales blowing up from the Southern Ocean against the south-setting Agulhas current. For a reference point that may translate better to sailors in North America, I’m told it’s comparable to experiencing a northerly gale in the Gulf Stream. There’s the very real possibility of some unpleasant weather, and big seas (20 meters!), and grief.

-- Passage Hindsight: Sailing From Madagascar To South Africa, by Sailingtotem.com

Family

Vansittart married Emilia Morse (died 1819), daughter of Nicholas Morse, Governor of Madras, in 1754. They had five sons (Henry, Arthur, Robert, George, and Nicholas), and two daughters, Emilia and Sophie.[1] They resided in England at Foxley's Manor in Bray, Berkshire.

Of the sons:

• Henry, the eldest (1756–1787), married Catherine Maria Powney.[4]

• Robert Vansittart, scored the first recorded cricket century in India, 102 for Old Etonians v. Rest of Calcutta in 1804.[6]

• The youngest, Nicholas Vansittart, 1st Baron Bexley, was Chancellor of the Exchequer from 12 May 1812 to 31 January 1823.

See also

• List of people who disappeared

References

1. Embree, Ainslie T. "Vansittart, Henry". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28103. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

2. Chisholm 1911.

3. Mason, Philip (1985). "4". The Men Who Ruled India. ISBN 81-7167-361-9.

4. Burke, Bernard (1866). A Genealogical History of the Dormant, Abeyant, Forfeited, and Extinct Peerages of the British Empire. Harrison. p. 546. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

5. Prior, D. L. (2004). "Scrafton, Luke". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 49 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 534. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/63538. ISBN 0-19-861399-7. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

6. Some dates in Indian cricket history, Wisden, 1967.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Vansittart, Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.