Scythians

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/16/21

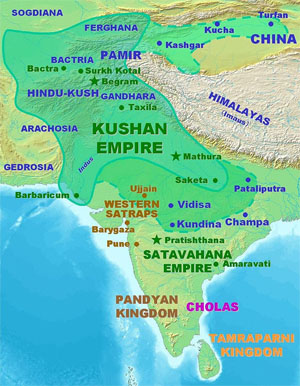

1. India, which is in shape quadrilateral, has its eastern as well as its western side bounded by the great sea, but on the northern side it is divided by Mount Hemodos from that part of Skythia which is inhabited by those Skythians who are called the Sakai, while the fourth or western side is bounded by the river called the Indus, which is perhaps the largest of all rivers in the world after the Nile.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A.

In the eighth century BC, Scythian warriors pursuing the Cimmerians rode south out of the steppes into the Near East in the area of northern Iran. They defeated the Cimmerians in the 630s and in the process conquered the powerful nation of the Medes, their Iranic ethnolinguistic relatives…. When they were defeated by the Medes in about 585 BC, they withdrew to the north and established themselves in the North Caucasus Steppe and the Pontic Steppe north of the Black Sea. They and their relatives built a huge empire stretching across Central Eurasia as far as China, including most of urbanized Central Asia, and grew fabulously rich on trade.

The Scythians and other North Iranic speakers thus dominated Central Eurasia at the same time that their southern relatives, the Medes and Persians, formed a vast empire based in the area of what is now western Iran and Iraq… they and other North Iranic-speaking relatives -- including their eastern branch, the Sakas -- continued to rule much of Central Eurasia for many centuries…

We know of not one but two great Scythian philosophers…

Anacharsis was the brother of Caduida, king of the Scythians. He spoke Greek because his mother was a Greek.

In about the forty-seventh Olympiad (592-589 BC), the age of Solon, he travelled to Greece and became well known for his astute, pithy remarks and wise sayings…. For example, "He said he wondered why among the Greeks the experts contend, but the non-experts decide."

The Greeks regularly quoted this and other pithy sayings of Anacharsis, which taken together are unlike those of any other known figure, Greek or foreign, in ancient Greek literature. Though he was considered to be a Scythian, the Greeks liked him, and he was counted as one of the Seven Sages of Antiquity in Greek philosophy. His own literary works are lost, but his fame was such that other writers used him as a stock character in their own compositions.

Sextus Empiricus, in his Against the Logicians, quotes an otherwise unknown work attributed to Anacharsis, on the Problem of the Criterion:

Who judges something skillfully? Is it the ordinary person or the skilled person?...

The argument is also strikingly close to the second part of the argument about the Problem of the Criterion in the Chuangtzu. Exactly as in the genuine saying of Anacharsis and in the argument attributed to him by Sextus Empiricus, the Chinese argument specifically concerns the ability to decide which of two contending individuals is right:

If you defeat me, I do not defeat you, are you then right, and I am not? If I defeat you, you do not defeat me, am I then right, you are not?...

The explanation for the similarity of these two passages could well be that the author of the "Anacharsis" quotation given by Sextus Empiricus had heard just such an argument, directly or indirectly, from a Scythian. This would have been a simple matter during the Classical Age because many Scythians then lived in Athens, where a number of them even served as the city's police force. If it was a stock Scythian story, an eastern Scythian -- a Saka -- could have transmitted a version of it to the Chinese, so that it ended up in the Chuangtzu, which is full of stories and arguments of a similar character.

Whatever the explanation, the explicit Greek connection of this story with a Scythian philosopher known for pithy sayings having a clever argument structure clearly indicates that it is the kind of thing Scythians were expected to say. In view of the Chinese testimony, it seems likely that it was something that some Scythians actually did say.

GAUTAMA BUDDHA, THE SCYTHIAN SAGE

The dates of Gautama Buddha are not recorded in any reliable historical source, and the traditional dates are calculated on unbelievable lineages…

[Scholars' continued insistence on following such dates anyway led to a 1988 conference devoted specifically to reconsideration of the dates of the Buddha, which however largely continued to take the fanciful, ahistorical, traditional accounts as if they were actual historical accounts]…

His personal name, Gautama, is evidently earliest recorded in the Chuangtzu, a Chinese work from the late fourth to third centuries BC….

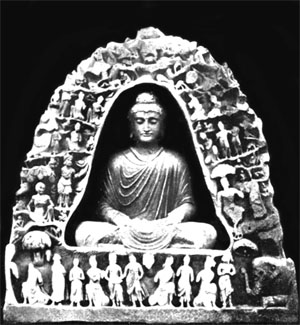

His epithet Sakamuni (later Sanskritized as Sakyamuni), 'Sage of the Scythians ("Sakas")', is unattested in the genuine Mauryan inscriptions or the Pali Canon.

[However, it has been demonstrated that the caretakers of the Pali tradition systematically expunged references to various ideas and practices to which they objected, especially things thought to be non-Indian.]

It is earliest attested, as Sakamuni, in the Gandhari Prakrit texts, which date to the first centuries AD (or possibly even the late first century BC)….

[It also occurs in Sanskrit in much later texts from Gandhara, as well as once, in a fifth-century AD Bactrian Buddhist text, as [x], without the characteristic -y- of the Sanskritized form of the name.]

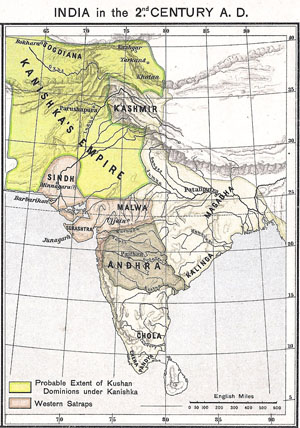

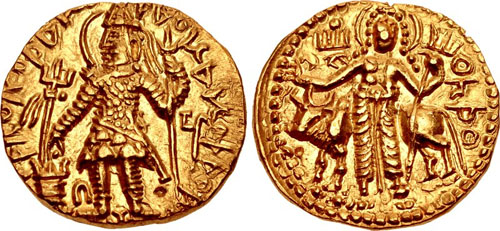

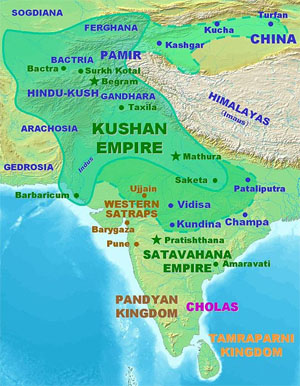

It is thus arguable that the epithet could have been applied to the Buddha during the Saka (Saka or "Indo-Scythian") Dynasty -- which dominated northwestern India on and off from approximately the first century BC, continuing into the early centuries AD as satraps or "vassals" under the Kushans -- and that the reason for it was strong support for Buddhism by the Sakas, Indo-Parthians, and Kushans.

However, it must be noted that the Buddha is the only Indian holy man before early modern times who bears an epithet explicitly identifying him as a non-Indian, a foreigner. It would have been unthinkably odd for an Indian saint to be given a foreign epithet if he was not actually a foreigner…. There are also very strong arguments -- including basic "doctrinal" ones -- indicating that Buddhism had fundamental foreign connections from the very beginning, as shown below. It is at any rate certain that Buddha has been identified as Sakamuni ~ Sakyamuni "Sage of the Scythians" in all varieties of Buddhism from the beginning of the recorded Buddhist tradition to the present, and that much of what is thought to be known about him can be identified specifically with things Scythian.

[The tradition by which Buddha was from a local Nepalese Sakya "clan" in the area of Lumbini is full of chronological and other insuperable problems, as shown by Bareau (1987); it is a very late development.]

Moreover, it must not be overlooked that we have no concrete datable evidence that any other wandering ascetics preceded the Buddha. The Scythians were nomads (from Greek [x]; 'wanderers in search of pasture, pastoralists') who lived in the wilderness, and it is thus quite likely that Gautama himself introduced wandering asceticism to India…

Buddha's teachings were unprecedented mainly because they opposed new foreign ideas -- the Early Zoroastrian ideas of good and bad karma, rebirth in Heaven (for those who were good), absolute Truth versus the Lie, and so on…

Buddha therefore must have lived after the introduction of Zoroastrianism in 519/518 BC, when the Achaemenid ruler Darius I invaded and conquered several Central Asian countries and then continued to the east, where he conquered Gandhara and Sindh, which were Indic-speaking, in about 517/516 BC.

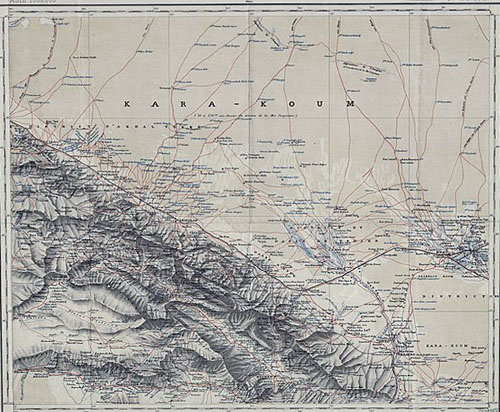

In the process of firming up his rule over the new territories, he stationed subordinate feudal lords, or satraps, over them, and some of the army was garrisoned there. Darius had come from conquering much of Central Asia proper, including Bactria and Arachosia, as well as the Saka Tigraxauda 'the Scythians wearing pointed hats', a nation of Scythians whose king, Skunkha, he captured…

From then on Scythians formed the backbone of the imperial forces together with the Medes and Persians, so some of the soldiers in the Indian campaign must have been Scythians, that is, Sakas…

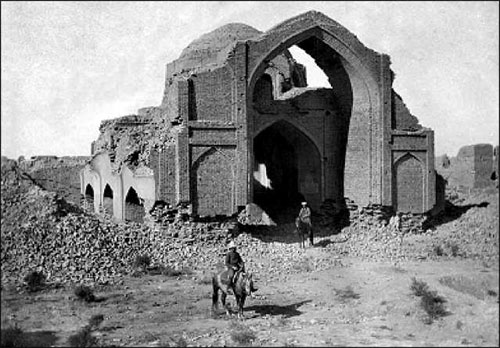

Gandhara became an important part of the empire. It is regularly included in the lists of provinces from the beginning of Darius's reign on to the end of the empire along with Bactria, Arachosia, the Sakas, and other neighboring realms.

There was a Persian satrap in Taxila, and official travellers went frequently between the Persian capital and one or another provincial locality in India, as attested by accounts preserved in the Persepolis Fortification Tablets, which detail the payments in kind to the travellers.

Moreover, "the Indians", one of the twenty financial districts of the Persian Empire recorded by Herodotus, paid by far the greatest sum in "tribute".

The Achaemenid influence in Gandhara was strong and long-lasting.

The conquest by Darius introduced the Persians' new religion, reformed Mazdaism, or Early Zoroastrianism, a strongly monotheistic faith with a creator God, Ahura Mazda, and with ideas of absolute Truth (Avestan asa, Old Persian arta) versus 'the Lie' (druj), and of an accumulation of Good and Bad deeds -- that is, "karma" -- which determined whether a person would be rewarded by "rebirth" in Heaven. These ideas are all found in the Gathas, the oldest part of the Avesta, which are attributed to Zoroaster himself, and all are expressed openly and repeatedly in the Old Persian royal inscriptions as well. Essentially the same ideas occur in the Major Inscriptions of the Mauryas in the third century BC in India.

The traditional view is that the Buddha reinterpreted existing Indian ideas found in the Upanishads, but the Upanishads in question cannot be dated to a period earlier than the Buddha…

Both Early Buddhism and Early Brahmanism are the direct outcome of the introduction of Zoroastrianism into eastern Gandhara by Darius I. Early Buddhism resulted from the Buddha's rejection of the basic principles of Early Zoroastrianism, while Early Brahmanism represents the acceptance of those principles. Over time, Buddhism would accept more and more of the rejected principles.

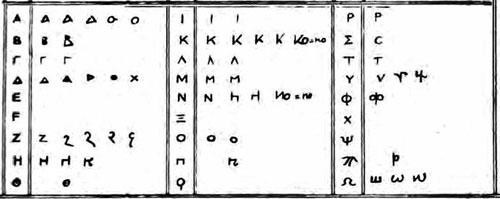

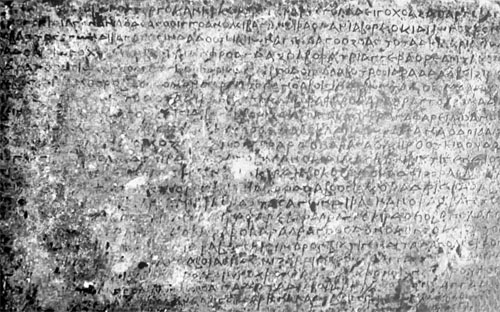

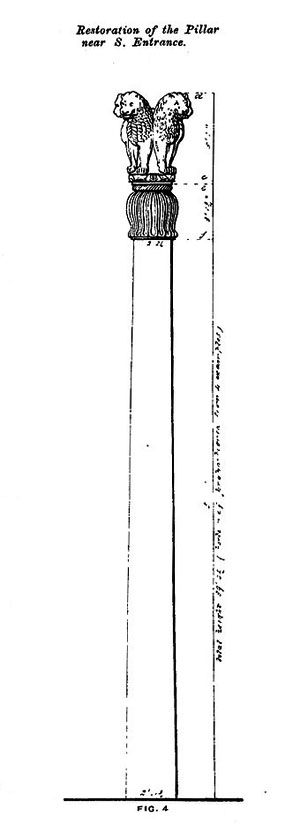

Darius also sponsored the creation of a completely new writing system -- Old Persian cuneiform script, which is partly modeled on Aramaic script, one of the main administrative scripts of the Persian Empire -- and the practice of erecting monumental inscriptions.

[In addition, he built imperial roads with rest houses provisioned for travellers.] ...

While, not surprisingly, the ordinary generic human contrast between truth and falsehood is found in the Vedas, the specifically Early Zoroastrian form of the ideas, including the result of following one or the other path, is completely alien to them. In the early Vedic religion, ritually correct performance of blood sacrifices was believed to be rewarded in this life, but the reward had nothing to do with one's virtuous actions or one's future in the afterlife….

[Bronkhorst (2007: 358), who remarks, "In the middle of the third century BC, it was Mazdaism, rather than Brahmanism, which predominated in the region between Kandahar and Taxila."] …

These specific "absolutist" or "perfectionist" ideas are firmly rejected by the Buddha in his earliest attested teachings, as shown in Chapter One. In short, the Buddha reacted primarily (if at all) not against Brahmanism, but against Early Zoroastrianism….

The word bodhi 'enlightenment', literally 'awakening', is first attested in the Eighth Rock Edict of the … ruler Devanampriya Priyadarsi…

The inscription thus can only refer to the ruler's acceptance of a form of the Early Buddhist Dharma -- not the more familiar Normative Buddhism, which is attested several centuries later….

The dates of Darius's conquest of Gandhara and Sindh (ca. 517 BC), and the late fourth century -- marked by the visit of Alexander (330-325 BC) along with his courtier Pyrrho, followed by Megasthenes two decades later -- are the chronological limits bracketing the enlightenment-to-death career of Gautama Buddha…

The shock of the introduction of new, alien religious ideas in the traditionally non-Persian, non-Zoroastrian environment of Central Asia, eastern Gandhara, and Sindh must have happened fairly soon after Darius's conquest and the establishment of his satrapies, when the satraps were undoubtedly still ethnically Persian and strongly Zoroastrian, and would have needed the ministrations of their priests. That would place the most likely time for the Buddha's period of asceticism and enlightenment within the first fifty years or so of Persian rule, meaning ca. 515 to ca. 465 BC, and his death after another forty years or so… making the latest date for his death ca. 425 BC. This chronology would also leave enough time for Early Buddhism to spread from Magadha (the region where Sambodhi, or Bodhgaya, is located) -- assuming it was first preached there by the Buddha -- northwestward into western Gandhara, Bactria, and beyond, and (as shown in Chapter Three), for his name Gautama and some of his ideas and practices to travel all the way to China and become popular no later than the Guodian tomb's end date (terminus ante quem) of 278 BC. Among the things that the scenario presented here explains are the striking alienness of Buddhism in India proper, its earliness in Gandhara and Bactria, and the difficulty of showing that the Buddha was originally from Magadha.

This brings up the problem of the Buddha's birthplace. Not only are his dates only very generally definable, his specific homeland is unknown as well. Despite widespread popular belief in the story that he came from Lumbini in what is now Nepal, all of the evidence is very late and highly suspect from beginning to end. Bareau has carefully analyzed the Lumbini birth story and shown it to be a late fabrication…

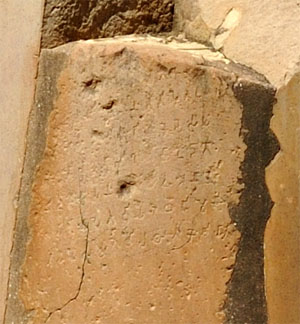

[The lone piece of evidence impelling scholars to accept the Lumbini story has been the Lumbini Inscription, which most scholars believe was erected by Asoka. However, the inscription itself actually reveals that it is not by Asoka, and all indications are that it is a late forgery, possibly even a modern one.] …

There are reasons to put the Buddha's teaching period -- most of his life, according to the traditional accounts -- somewhere in northern India, in a region affected by the monsoons…

the Buddha must have passed away well before 325 to 304 BC, the dates for the appearance of the earliest hard evidence on the existence of Buddhism or elements of Buddhism. This is still three centuries before even the earliest Gandhari texts and the traditional (high) date of the Pali Canon. Despite widespread belief that the latter collections of material, both of which are from the Saka-Kushan period or later, represent "Early Buddhism", the work of many scholars has shown that even by internal evidence alone it must be already quite far removed from the earliest Buddhism -- the teachings and practices of the followers of the Buddha himself and the next few generations after him, up to the mid-third century BC.

-- Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter With Early Buddhism in Central Asia, by Christopher I. Beckwith

Scythian comb from Solokha, early 4th century BC

The approximate extent of Eastern Iranian languages circa 170 BC.

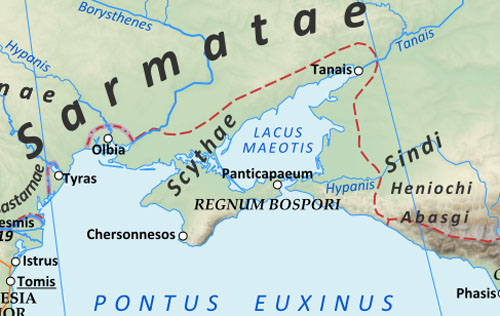

The Scythians (/ˈsɪθiənz, ˈsɪð-/; from Greek Σκύθης, Σκύθοι), also known as Scyths,[1] Saka, Sakae, Iskuzai, or Askuzai, were an ancient nomadic people of Eurasia, inhabiting the region Scythia. Classical Scythians dominated the Pontic steppe from approximately the 7th century BC until the 3rd century BC.[2] They can also be referred to as Pontic Scythians, European Scythians or Western Scythians.[3][4] They were part of the wider Scythian cultures, stretching across the Eurasian Steppe.[5][6] In a broader sense, Scythians has also been used to designate all early Eurasian nomads,[6] although the validity of such terminology is controversial.[5] According to Di Cosmo, other terms such as "Early nomadic" would be preferable.[7] Eastern members of the Scythian cultures are often specifically designated as Sakas.[8]

The Scythians are generally believed to have been of Iranian (or Iranic; an Indo-European ethno-linguistic group) origin;[9] they spoke a language of the Scythian branch of the Iranian languages,[10] and practiced a variant of ancient Iranian religion.[11] Among the earliest peoples to master mounted warfare,[12] the Scythians replaced the Cimmerians as the dominant power on the Pontic steppe in the 8th century BC.[13] During this time they and related peoples came to dominate the entire Eurasian Steppe from the Carpathian Mountains in the west to Ordos Plateau in the east,[14][15] creating what has been called the first Central Asian nomadic empire.[13][16] Based in what is modern-day Ukraine and southern Russia, they called themselves Scoloti and were led by a nomadic warrior aristocracy known as the Royal Scythians.

In the 7th century BC, the Scythians crossed the Caucasus and frequently raided the Middle East along with the Cimmerians, playing an important role in the political developments of the region.[13][16] Around 650–630 BC, Scythians briefly dominated the Medes of the western Iranian Plateau,[17][18] stretching their power to the borders of Egypt.[12] After losing control over Media, they continued intervening in Middle Eastern affairs, playing a leading role in the destruction of the Assyrian Empire in the Sack of Nineveh in 612 BC. The Scythians subsequently engaged in frequent conflicts with the Achaemenid Empire, and suffered a major defeat against Macedonia in the 4th century BC[12] and were subsequently gradually conquered by the Sarmatians, a related Iranian people living to their east.[19] In the late 2nd century BC, their capital at Scythian Neapolis in the Crimea was captured by Mithridates VI and their territories incorporated into the Bosporan Kingdom.[11] By this time they had been largely Hellenized. By the 3rd century AD, the Sarmatians and last remnants of the Scythians were dominated by the Alans, and were being overwhelmed by the Goths. By the early Middle Ages, the Scythians and the Sarmatians had been largely assimilated and absorbed by early Slavs.[20][21] The Scythians were instrumental in the ethnogenesis of the Ossetians, who are believed to be descended from the Alans.[22]

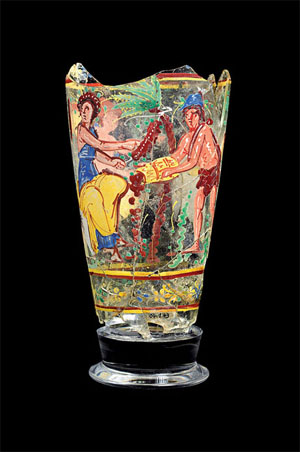

The Scythians played an important part in the Silk Road, a vast trade network connecting Greece, Persia, India and China, perhaps contributing to the prosperity of those civilisations.[23] Settled metalworkers made portable decorative objects for the Scythians, forming a history of Scythian metalworking. These objects survive mainly in metal, forming a distinctive Scythian art.[24]

The name of the Scythians survived in the region of Scythia. Early authors continued to use the term "Scythian", applying it to many groups unrelated to the original Scythians, such as Huns, Goths, Turkic peoples, Avars, Khazars, and other unnamed nomads.[11][25] The scientific study of the Scythians is called Scythology.

Names

Etymology

Linguist Oswald Szemerényi studied synonyms of various origins for Scythian and differentiated the following terms: Skuthes Σκύθης, Skudra, Sug(u)da and Saka.[26]

• Skuthes Σκύθης, Skudra, Sug(u)da descended from the Indo-European root (s)kewd-, meaning "propel, shoot" (cognate with English shoot). *skud- is the zero-grade form of the same root. Szemerényi restores the Scythians' self-name as *skuda (roughly "archer"). This yields the Ancient Greek Skuthēs Σκύθης (plural Skuthai Σκύθαι) and the Assyrian Aškuz. The Old Armenian: սկիւթ skiwtʰ is based on itacistic Greek. A late Scythian sound change from /d/ to /l/ established the Greek word Skolotoi (Σκώλοτοι), from the Scythian *skula which, according to Herodotus, was the self-designation of the Royal Scythians.[27] Other sound changes have produced Sogdia.

• The term Saka reflected in Old Persian: Sakā, Greek: Σάκαι; Latin: Sacae, Sanskrit: शक Śaka comes from an Iranian verbal root sak-, "go, roam" and thus means "nomad". Although closely related, the Saka people are nomadic Iranians, that are to be distinguished from the European Scythians and inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin.[8][better source needed][28][29]

Exonyms

The name Scythian is derived from the name used for them by the ancient Greeks.[30] Iskuzai or Askuzai was the name given them by the Assyrians. The ancient Persians used the term Saka for all nomads of the Eurasian Steppe, including the Scythians.[31]

Ethnonyms

Herodotus said the ruling class of the Scythians, whom he referred to as the Royal Scythians, called themselves Skolotoi.[5]

Modern terminology

See also: Scythian cultures

In scholarship, the term Scythians generally refers to the nomadic Iranian people who dominated the Pontic steppe from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC.[2]

The Scythians share several cultural similarities with other populations living to their east, in particular similar weapons, horse gear and Scythian art, which has been referred to as the Scythian triad.[5][7] Cultures sharing these characteristics have often been referred to as Scythian cultures, and its peoples called Scythians.[6][32] Peoples associated with Scythian cultures include not only the Scythians themselves, who were a distinct ethnic group,[33] but also Cimmerians, Massagetae, Saka, Sarmatians and various obscure peoples of the forest steppe,[5][6] such as early Slavs, Balts and Finnic peoples.[31][34] Within this broad definition of the term Scythian, the actual Scythians have often been distinguished from other groups through the terms Classical Scythians, Western Scythians, European Scythians or Pontic Scythians.[6]

Scythologist Askold Ivantchik notes with dismay that the term "Scythian" has been used within both a broad and a narrow context, leading to a good deal of confusion. He reserves the term "Scythian" for the Iranian people dominating the Pontic steppe from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC.[5] Nicola Di Cosmo writes that the broad concept of "Scythian" is "too broad to be viable", and that the term "early nomadic" is preferable.[7]

History

Origins

Literary evidence

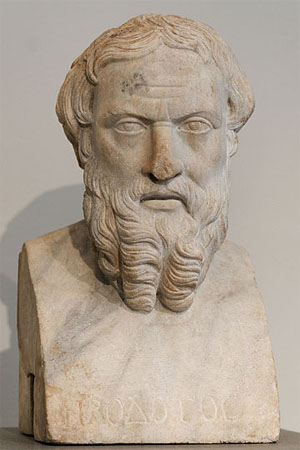

The 5th-century BC Greek historian Herodotus is the most important literary source on the origins of the Scythians

The Scythians first appeared in the historical record in the 8th century BC.[26] Herodotus reported three contradictory versions as to the origins of the Scythians, but placed greatest faith in this version:[35]

There is also another different story, now to be related, in which I am more inclined to put faith than in any other. It is that the wandering Scythians once dwelt in Asia, and there warred with the Massagetae, but with ill success; they therefore quitted their homes, crossed the Araxes, and entered the land of Cimmeria.

Herodotus presented four different versions of Scythian origins:

1. Firstly (4.7), the Scythians' legend about themselves, which portrays the first Scythian king, Targitaus, as the child of the sky-god and of a daughter of the Dnieper. Targitaus allegedly lived a thousand years before the failed Persian invasion of Scythia, or around 1500 BC. He had three sons, before whom fell from the sky a set of four golden implements—a plough, a yoke, a cup and a battle-axe. Only the youngest son succeeded in touching the golden implements without them bursting with fire, and this son's descendants, called by Herodotus the "Royal Scythians", continued to guard them.

2. Secondly (4.8), a legend told by the Pontic Greeks featuring Scythes, the first king of the Scythians, as a child of Hercules and Echidna.

3. Thirdly (4.11), in the version which Herodotus said he believed most, the Scythians came from a more southern part of Central Asia, until a war with the Massagetae (a powerful tribe of steppe nomads who lived just northeast of Persia) forced them westward.

4. Finally (4.13), a legend which Herodotus attributed to the Greek bard Aristeas, who claimed to have got himself into such a Bachanalian fury that he ran all the way northeast across Scythia and further. According to this, the Scythians originally lived south of the Rhipaean mountains, until they got into a conflict with a tribe called the Issedones, pressed in their turn by the "one-eyed Arimaspians"; and so the Scythians decided to migrate westwards.

Accounts by Herodotus of Scythian origins has been discounted recently; although his accounts of Scythian raiding activities contemporary to his writings have been deemed more reliable.[36]

Archaeological evidence

Modern interpretation of historical, archaeological and anthropological evidence has proposed two broad hypotheses on Scythian origins.[37]

The first hypothesis, formerly more espoused by Soviet and then Russian researchers, roughly followed Herodotus' (third) account, holding that the Scythians were an Eastern Iranian-speaking group who arrived from Inner Asia, i.e. from the area of Turkestan and western Siberia.[37]

The second hypothesis, according to Roman Ghirshman and others, proposes that the Scythian cultural complex emerged from local groups of the Srubna culture at the Black Sea coast,[37] although this is also associated with the Cimmerians. According to Pavel Dolukhanov this proposal is supported by anthropological evidence which has found that Scythian skulls are similar to preceding findings from the Srubna culture, and distinct from those of the Central Asian Saka.[38] Yet, according to J. P. Mallory, the archaeological evidence is poor, and the Andronovo culture and "at least the eastern outliers of the Timber-grave culture" may be identified as Indo-Iranian.[37]

Genetic evidence

In 2017, a genetic study of the Scythians suggested that they can best be described as a mixture of European-related ancestry from the Yamna culture and an East Asian/Siberian ancestry, and emerged on the Pontic steppe. The authors concluded that there is evidence for significant geneflow from East-Eurasia to West-Eurasia, from various migrations during the early Iron Age.[6] Based on the analysis of mithocondrial lineages, another later 2017 study suggested that the Scythians were directly descended from the Srubnaya culture.[39] A later analysis of paternal lineages, published in 2018, found significant genetic differences between the Srubnaya and the Scythians. They further found that the nomadic population of Central Asia, e.g. the Scythians, were genetically heterogeneous and carried genetic affinities with populations from several other regions including the Far East and the southern Urals.[40] Another 2019 study also concluded that migrations must have played a part in the emergence of the Scythians as the dominant power of the Pontic steppe.[41]

Early history

Gold Scythian belt title, Mingachevir (ancient Scythian kingdom), Azerbaijan, 7th century BC

Herodotus provides the first detailed description of the Scythians. He classifies the Cimmerians as a distinct autochthonous tribe, expelled by the Scythians from the northern Black Sea coast (Hist. 4.11–12). Herodotus also states (4.6) that they consisted of the Auchatae, Catiaroi, Traspians, and Paralatae or "Royal Scythians".

In the early 7th century BC, the Scythians and Cimmerians are recorded in Assyrian texts as having conquered Urartu. In the 670s, the Scythians under their king Bartatua raided the territories of the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrian king Esarhaddon managed to make peace with the Scythians by marrying off his daughter to Bartatua and by paying a large amount of tribute.[5] Bartatua was succeeded by his son Madius ca. 645 BC, after which they launched a great raid on Palestine and Egypt. Madius subsequently subjugated the Median Empire. During this time, Herodotus notes that the Scythians raided and exacted tribute from "the whole of Asia". In the 620s, Cyaxares, leader of the Medes, treacherously killed a large number of Scythian chieftains at a feast. The Scythians were subsequently driven back to the steppe. In 612 BC, the Medes and Scythians participated in the destruction of the Assyrian Empire at the Battle of Nineveh. During this period of incursions into the Middle East, the Scythians became heavily influenced by the local civilizations.[42]

In the 6th century BC, the Greeks had begun establishing settlements along the coasts and rivers of the Pontic steppe, coming in contact with the Scythians. Relations between the Greeks and the Scythians appear to have been peaceful, with the Scythians being substantially influenced by the Greeks, although the city of the Panticapaeum might have been destroyed by the Scythians in the mid-century BC. During this time, the Scythian philosopher Anacharsis traveled to Athens, where he made a great impression on the local people with his "barbarian wisdom".[5]

War with Persia

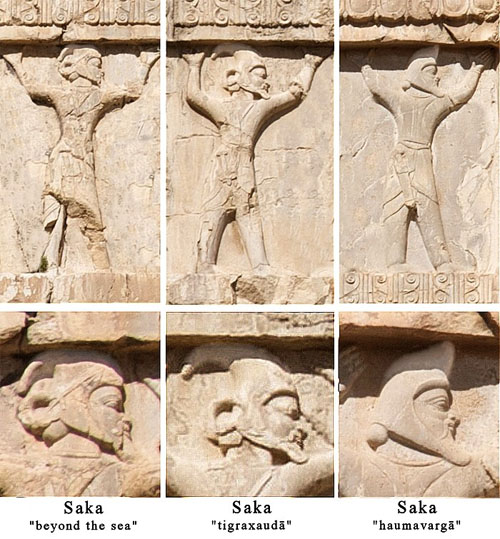

Reliefs depicting the soldiers of the Achaemenid army, Xerxes I tomb, circa 480 BCE. The Achaemenids referred to all nomads to their north as Saka,[31] and divided them into three categories: The Sakā tayai paradraya ("beyond the sea", presumably the Scythians), the Sakā tigraxaudā ("with pointed caps"), and the Sakā haumavargā ("Hauma drinkers", furthest East).[43]

By the late 6th century BC, the Archaemenid king Darius the Great had built Persia into becoming the most powerful empire in the world, stretching from Egypt to India. Planning an invasion of Greece, Darius first sought to secure his northern flank against Scythian introads. Thus, Darius declared war on the Scythians.[42] At first, Darius sent his Cappadocian satrap Ariamnes with a vast fleet (estimated at 600 ships by Herodotus) into Scythian territory, where several Scythian nobles were captured. He then built a bridge across the Bosporus and easily defeated the Thracians, crossing the Danube into Scythian territory with a large army (700,000 men if one is to believe Herodotus) in 512 BC.[44] At this time Scythians were separated into three major kingdoms, with the leader of the largest tribe, King Idanthyrsus, being the supreme ruler, and his subordinate kings being Scopasis and Taxacis.[citation needed]

Unable to receive support from neighboring nomadic peoples against the Persians, the Scythians evacuated their civilians and livestock to the north and adopted a scorched earth strategy, while simultaneously harassing the extensive Persian supply lines. Suffering heavy losses, the Persians reached as far as the Sea of Azov, until Darius was compelled to enter into negotiations with Idanthyrsus, which, however, broke down. Darius and his army eventually reatreated across the Danube back into Persia, and the Scythians thereafter earned a reputation of invincibility among neighboring peoples.[5][44]

Golden Age

In the aftermath of their defeat of the Persian invasion, Scythian power grew considerably, and they launched campaigns against their Thracian neighbors in the west.[45] In 496 BC, the Scythians launched an great expedition into Thrace, reaching as far as Chersonesos.[5] During this time they negotiated an alliance with the Achaemenid Empire against the Spartan king Cleomenes I. A prominent king of the Scythians in the 5th century BC was Scyles.[42]

The Scythian offensive against the Thracians was checked by the Odrysian kingdom. The border between the Scythians and the Odrysian kingdom was thereafter set at the Danube, and relations between the two dynasties were good, with dynastic marriages frequently occurring.[5] The Scythians also expanded towards the north-west, where they destroyed numerous fortified settlements and probably subjucated numerous settled populations. A similar fate was suffered by the Greek cities of the northwestern Black Sea coast and parts of the Crimea, over which the Scythians established political control.[5] Greek settlements along the Don River also came under the control of the Scythians.[5]

A division of responsibility developed, with the Scythians holding the political and military power, the urban population carrying out trade, and the local sedentary population carrying out manual labor.[5] Their territories grew grain, and shipped wheat, flocks, and cheese to Greece. The Scythians apparently obtained much of their wealth from their control over the slave trade from the north to Greece through the Greek Black Sea colonial ports of Olbia, Chersonesos, Cimmerian Bosporus, and Gorgippia.[citation needed]

When Herodotus wrote his Histories in the 5th century BC, Greeks distinguished Scythia Minor, in present-day Romania and Bulgaria, from a Greater Scythia that extended eastwards for a 20-day ride from the Danube River, across the steppes of today's East Ukraine to the lower Don basin.[citation needed]

Scythian offensives against the Greek colonies of the northeastern Black Sea coast were largely unsuccessful, as the Greeks united under the leadership of the city of Panticapaeum and put up a vigorous defence. These Greek cities developed into the Bosporan Kingdom. Meanwhile, several Greek colonies formerly under Scythian control began to reassert their independence. It is possible that the Scythians were suffering from internal troubles during this time.[5] By the mid-4th century BC, the Sarmatians, a related Iranian people living to the east of the Scythians, began expanding into Scythian territory.[42]

Scythian king Skilurus, relief from Scythian Neapolis, Crimea, 2nd century BC

The 4th century BC was a flowering of Scythian culture. The Scythian king Ateas managed to unite under his power the Scythian tribes living between the Maeotian marshes and the Danube, while simultaneously enroaching upon the Thracians.[45] He conquered territories along the Danube as far the Sava river and established a trade route from the Black Sea to the Adriatic, which enabled a flourishing of trade in the Scythian kingdom. The westward expansion of Ateas brought him into conflict with Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 BC), with whom he had previously been allied,[5] who took military action against the Scythians in 339 BC. Ateas died in battle, and his empire disintegrated.[42] Philip's son, Alexander the Great, continued the conflict with the Scythians. In 331 BC, his general Zopyrion invaded Scythian territory with a force of 30,000 men, but was routed and killed by the Scythians near Olbia.[5][45]

Decline

In the aftermath of conflict between Macedon and the Scythians, the Celts seem to have displaced the Scythians from the Balkans; while in south Russia, a kindred tribe, the Sarmatians, gradually overwhelmed them. In 310–309 BC, as noted by Diodorus Siculus, the Scythians, in alliance with the Bosporan Kingdom, defeated the Siraces in a great battle at the river Thatis.[45]

By the early 3rd century BC, the Scythian culture of the Pontic steppe suddenly disappears. The reasons for this are controversial, but the expansion of the Sarmatians certainly played a role. The Scythians in turn shifted their focus towards the Greek cities of the Crimea.[5]

The territory of the Scythae Basilaei ("Royal Scyths") along the north shore of the Black Sea around 125 AD

By around 200 BC, the Scythians had largely withdrawn into the Crimea. By the time of Strabo's account (the first decades AD), the Crimean Scythians had created a new kingdom extending from the lower Dnieper to the Crimea, centered at Scythian Neapolis near modern Simferopol. They had become more settled and were intermingling with the local populations, in particular the Tauri, and were also subjected to Hellenization. They maintained close relations with the Bosporan Kingdom, with whose dynasty they were linked by marriage. A separate Scythian territory, known as Scythia Minor, existed in modern-day Dobruja, but was of little significance.[5]

In the 2nd century BC, the Scythian kings Skilurus and Palakus sought to extend their control over the Greek cities north of the Black Sea. The Greek cities of Chersonesus and Olbia in turn requested the aid of Mithridates the Great, king of Pontus, whose general Diophantus defeated their armies in battle, took their capital and annexed their territory to the Bosporan Kingdom.[11][42][45] After this time, the Scythians practically disappeared from history.[45] Scythia Minor was also defeated by Mithridates.[5]

In the years after the death of Mithridates, the Scythians had transitioned to a settled way of life and were assimilating into neighboring populations. They made a resurgence in the 1st century AD and laid siege to Chersonesos, who were obliged to seek help from the Roman Empire. The Scythians were in turn defeated by Roman commander Tiberius Plautius Silvanus Aelianus.[5] By the 2nd century AD, archaeological evidence show that the Scythians had been largely assimilated by the Sarmatians and Alans.[5] The capital city of the Scythians, Scythian Neapolis, was destroyed by migrating Goths in the mid-3rd century AD. In subsequent centuries, remaining Scythians and Sarmatians were largely assimilated by early Slavs.[20][21] The Scythians and Sarmatians played an instrumental role in the ethnogenesis of the Ossetians, who are considered direct descendants of the Alans.[22]

Archaeology

Scythian defence line 339 BC reconstruction in Polgár, Hungary

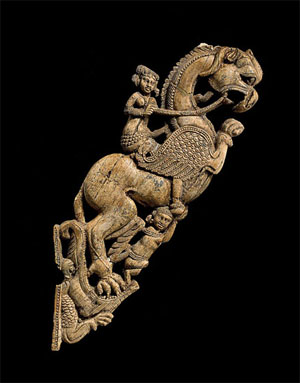

Archaeological remains of the Scythians include kurgan tombs (ranging from simple exemplars to elaborate "Royal kurgans" containing the "Scythian triad" of weapons, horse-harness, and Scythian-style wild-animal art), gold, silk, and animal sacrifices, in places also with suspected human sacrifices.[46] Mummification techniques and permafrost have aided in the relative preservation of some remains. Scythian archaeology also examines the remains of cities and fortifications.[47][48][49]

Scythian archaeology can be divided into three stages:[5]

• Early Scythian – from the mid-8th or the late 7th century BC to about 500 BC

• Classical Scythian or Mid-Scythian – from about 500 BC to about 300 BC

• Late Scythian – from about 200 BC to the mid-3rd century CE, in the Crimea and the Lower Dnieper, by which time the population was settled.

Early Scythian

In the south of Eastern Europe, Early Scythian culture replaced sites of the so-called Novocherkassk culture. The date of this transition is disputed among archaeologists. Dates ranging from the mid-8th century to the late 7th century BC have been proposed. A transition in the late 8th century BC has gained the most scholarly support. The origins of the Early Scythian culture is controversial. Many of its elements are of Central Asian origin, but the culture appears to have reached its ultimate form on the Pontic steppe, partially through the influence of North Caucasian elements and to a smaller extent the influence of Near Eastern elements.[5]

The period in the 8th and 7th centuries BC when the Cimmerians and Scythians raided the Near East are ascribed to the later stages of the Early Scythian culture. Examples of Early Scythian burials in the Near East include those of Norşuntepe and İmirler. Objects of Early Scythian type have been found in Urartian fortresses such as Teishebaini, Bastam and Ayanis-kale. Near Eastern influences are probably explained through objects made by Near Eastern craftsmen on behalf of Scythian chieftains.[5]

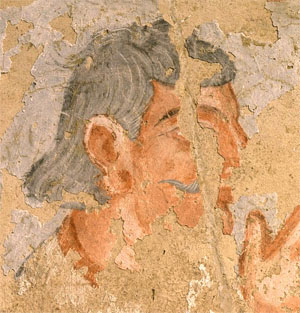

An arm from the throne of a Scythian king, 7th century BC. Found at the Kerkemess kurgan, Krasnodar Krai in 1905. On exhibit at the Hermitage Museum

Early Scythian culture is known primarily from its funerary sites, because the Scythians at this time were nomads without permanent settlements. The most important sites are located in the northwestern parts of Scythian territories in the forest steppes of the Dnieper, and the southeastern parts of Scythian territories in the North Caucasus. At this time it was common for the Scythians to be buried in the edges of their territories. Early Scythian sites are characterized by similar artifacts with minor local variations.[5]

Kurgans from the Early Scythian culture have been discovered in the North Caucasus. Some if these are characterized by great wealth, and probably belonged royals of aristocrats. They contain not only the deceased, but also horses and even chariots. The burial rituals carried out in these kurgans correspond closely with those described by Herodotus. The greatest kurgans from the Early Scythian culture in the North Caucasus are found at Kelermesskaya, Novozavedennoe II (Ulsky Kurgans) and Kostromskaya. One kurgan at Ulsky was found measured at 15 metres in height and contained more than 400 horses. Kurgans from the 7th century BC, when the Scythians were raiding the Near East, typically contain objects of Near Eastern origin. Kurgans from the late 7th century BC, however, contain few Middle Eastern objects, but, rather, objects of Greek origin, pointing to increased contacts between the Scythians and Greek colonists.[5]

Important Early Scythian sites have also been found in the forest steppes of the Dnieper. The most important of these finds is the Melgunov Kurgan. This kurgan contains several objects of Near Eastern origin so similar to those found at the kurgan in Kelermesskaya that they were probably made in the same workshop. Most of the Early Scythian sites in this area are situated along the banks of the Dnieper and its tributaries. The funerary rites of these sites are similar but not identical to those of the kurgans in the North Caucasus.[5]

Important Early Scythian sites have also been discovered in the areas separating the North Caucasus and the forest steppes. These include the Krivorozhskiĭ kurgan on the eastern banks of the Donets, and the Temir-gora kurgan in the Crimea. Both date to the 7th century BC and contain Greek imports. The Krivorozhskiĭ also display Near Eastern influences.[5]

The famous gold stag of Kostromskaya, Russia

Apart from funerary sites, numerous settlements from the Early Scythian period have been discovered. Most of these settlements are located in the forest steppe zone and are non-fortified. The most important of these sites in the Dnieper area are Trakhtemirovo, Motroninskoe and Pastyrskoe. East of these, at the banks of the Vorskla River, a tributary of the Dnieper, lies the Bilsk settlement. Occupying an area of 4,400 hectares with an outer rampart at over 30 km, Bilsk is the largest settlement in the forest steppe zone.[5] It has been tentatively identified by a team of archaeologists led by Boris Shramko as the site of Gelonus, the purported capital of Scythia.

Another important large settlement can be found at Myriv. Dating from the 7th and 6th centuries BC, Myriv contains a significant amount of imported Greek objects, testifying to lively contacts with Borysthenes, the first Greek colony established on the Pontic steppe (ca. 625 BC). Within the ramparts in these settlements there were areas without buildings, which were probably occupied by nomadic Scythians seasonally visiting the sites.[5]

The Early Scythian culture came to an end in the latter part of the 6th century BC.[5]

Classical Scythian

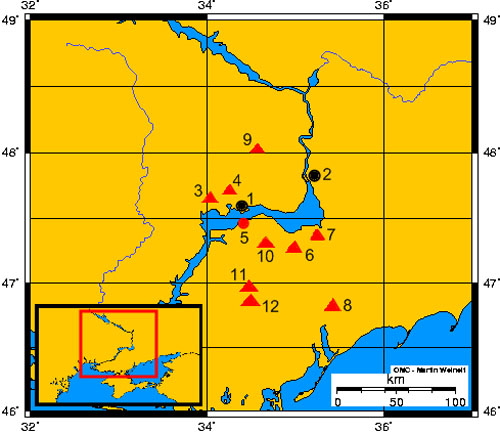

Distribution of Scythian kurgans and other sites along the Dnieper Rapids during the Classical Scythian period

By the end of the 6th century BC, a new period begins in the material culture of the Scythians. Certain scholars consider this a new stage in the Scythian culture, while others consider it an entirely new archaeological culture. It is possible that this new culture arose through the settlement of a new wave of nomads from the east, who intermingled with the local Scythians. The Classical Scythian period saw major changes in Scythian material culture, both with regards to weapons and art style. This was largely through Greek influence. Other elements had probably been brought from the east.[5]

Like in Early Scythian culture, the Classical Scythian culture is primarily represented through funerary sites. The area of distribution of these sites has, however, changed. Most of them, including the richest, are located on the Pontic steppe, in particular the area around the Dnieper Rapids.[5]

At the end of the 6th century BC, new funerary rites appeared, characterized by more complex kurgans. This new style was rapidly adopted throughout Scythian territory. Like before, elite burials usually contained horses. A buried king was usually accompanied with multiple people from his entourage. Burials containing both males and females are quite common both in elite burials and in the burials of the common people.[5]

The most important Scythian kurgans of the Classical Scythian culture in the 6th and 5th centuries BC are Ostraya Tomakovskaya Mogila, Zavadskaya Mogila 1, Novogrigor'evka 5, Baby and Raskopana Mogila in the Dnieper Rapids, and the Zolotoi and Kulakovskiĭ kurgans in the Crimea.[5]

The greatest, so-called "royal" kurgans of the Classical Scythian culture are dated to the 4th century BC. These include Solokha, Bol'shaya Cymbalka, Chertomlyk, Oguz, Alexandropol and Kozel. The second greatest, so-called "aristocratic" kurgans, include Berdyanskiĭ, Tovsta Mohyla, Chmyreva Mogila, Five Brothers 8, Melitopolsky, Zheltokamenka and Krasnokutskiĭ.[5]

West side of the Kozel Kurgans

Excavation at kurgan Sengileevskoe-2 found gold bowls with coatings indicating a strong opium beverage was used while cannabis was burning nearby. The gold bowls depicted scenes showing clothing and weapons.[50]

By the time of Classical Scythian culture, the North Caucasus appears to no longer be under Scythian control. Rich kurgans in the North Caucasus have been found at the Seven Brothers Hillfort, Elizavetovka and Ulyap, but although they contain elements of Scythian culture, these probably belonged to an unrelated local population. Rich kurgans of the forest steppe zone from the 5th and 4th centuries BC have been discovered at places such as Ryzhanovka, but these are not as grand as the kurgans of the steppe further south.[5]

Funerary sites with Scythian characteristics have also been discovered in several Greek cities. These include several unusually rich burials such as Kul-Oba (near Panticapaeum in the Crimea) and the necropolis of Nymphaion. The sites probably represent Scythian aristocrats who had close ties, if not family ties, with the elite of Nymphaion and aristocrats, perhaps even royals, of the Bosporan Kingdom.[5]

In total, more than 3,000 Scythian funerary sites from the 4th century BC have been discovered on the Pontic steppe. This number far exceeds the number of all funerary sites from previous centuries.[5]

Apart from funerary sites, remains of Scythian cities from this period have been discovered. These include both continuations from the Early Scythian period and newly founded settlements. The most important of these is the settlement of Kamenskoe on the Dniepr, which existed from the 5th century to the beginning of the 3rd century BC. It was a fortified settlement occupying an area of 12 square km. The chief occupation of its inhabitants appears to have been metalworking, and the city was probably an important supplier of metalwork for the nomadic Scythians. Part of the population was probably composed of agriculturalists. It is likely that Kamenskoe also served as a political center in Scythia. A significant part of Kamenskoe was not built up, perhaps to set it aside for the Scythian king and his entourage during their seasonal visits to the city.[5] János Harmatta suggests that Kamenskoe served as a residence for the Scythian king Ateas.[11]

By the 4th century BC, it appears that some of the Scythians were adopting an agricultural way of life similar to the peoples of the forest steppes. As a result, a number of fortified and non-fortified settlements spring up in the areas of the lower Dnieper. Part of the settled inhabitants of Olbia were also of Scythian origin.[5]

Classical Scythian culture lasts until the late 4th century or early 3rd century BC.[5]

Late Scythian

Remains of Scythian Neapolis near modern-day Simferopol, Crimea. It served as a political center of the Scythians in the Late Scythian period.

The last period in the Scythian archaeological culture is the Late Scythian culture, which existed in the Crimea and the Lower Dnieper from the 3rd century BC. This area was at the time mostly settled by Scythians.[5]

Archaeologically the Late Scythian culture has little in common with its predecessors. It represents a fusion of Scythian traditions with those of the Greek colonists and the Tauri, who inhabited the mountains of the Crimea. The population of the Late Scythian culture was mainly settled, and were engaged in stockbreeding and agriculture. They were also important traders, serving as intermediaries between the classical world and the barbarian world.[5]

Recent excavations at Ak-Kaya/Vishennoe implies that this site was the political center of the Scythians in the 3rd century BC and the early part of the 2nd century BC. It was a well-protected fortress constructed in accordance with Greek principles.[5]

The most important site of the Late Crimean culture is Scythian Neaoplis, which was located in Crimea and served as the capital of the Late Scythian kingdom from the early 2nd century BC to the beginning of the 3rd century AD. Scythian Neapolis was largely constructed in accordance with Greek principles. Its royal palace was destroyed by Diophantus, a general of the Pontic king Mithridates VI, at the end of the 2nd century BC, and was not rebuilt. The city nevertheless continued to exist as a major urban center. It underwent significant change from the 1st century to the 2nd century AD, eventually being left with virtually no buildings except from its fortifications. New funerary rites and material features also appear. It is probable that these changes represent the assimilation of the Scythians by the Sarmatians. A certain continuity is, however, observable. From the end of the 2nd century to the middle of the 3rd century AD, Scythian Neapolis transforms into a non-fortified settlement containing only a few buildings.[5]

Apart from Scythian Neapolis and Ak-Kaya/Vishennoe, more than 100 fortified and non-fortified settlements from the Late Scythian culture have been discovered. They are often accompanied by a necropolis. Late Scythian sites are mostly found in areas around the foothills of the Crimean mountains and along the western coast of the Crimea. Some of these settlements had earlier been Greek settlements, such as Kalos Limen and Kerkinitis. Many of these coastal settlements served as trading ports.[5]

The largest Scythian settlements after Neapolis and Ak-Kaya-Vishennoe were Bulganak, Ust-Alma and Kermen-Kyr. Like Neapolis and Ak-Kaya, these are characterized by a combination of Greek architectural principles and local ones.[5]

A unique group of Late Scythian settlements were city-states located on the banks of the Lower Dnieper. The material culture of these settlements was even more Hellenized than those on the Crimea, and they were probably closely connected to Olbia, if not dependent it.[5]

Burials of the Late Scythian culture can be divided into two kurgans and necropolises, with necropolises becoming more and more common as time progresses. The largest such necropolis has been found at Ust-Alma.[5]

Because of close similarities between the material culture of the Late Scythians and that of neighbouring Greek cities, many scholars have suggested that Late Scythian cites, particularly those of the Lower Dnieper, were populated at last partly by Greeks. Influences of Sarmatian elements and the La Tène culture have been pointed out.[5]

The Late Scythian culture ends in the 3rd century AD.[5]

Culture and society

Kurgan stelae of a Scythian at Khortytsia, Ukraine

Since the Scythians did not have a written language, their non-material culture can only be pieced together through writings by non-Scythian authors, parallels found among other Iranian peoples, and archaeological evidence.[5]

Tribal divisions

See also: Trifunctional hypothesis

Scythians lived in confederated tribes, a political form of voluntary association which regulated pastures and organised a common defence against encroaching neighbours for the pastoral tribes of mostly equestrian herdsmen. While the productivity of domesticated animal-breeding greatly exceeded that of the settled agricultural societies, the pastoral economy also needed supplemental agricultural produce, and stable nomadic confederations developed either symbiotic or forced alliances with sedentary peoples—in exchange for animal produce and military protection.

Herodotus relates that three main tribes of the Scythians descended from three sons of Targitaus: Lipoxais, Arpoxais, and Colaxais. They called themselves Scoloti, after one of their kings.[51] Herodotus writes that the Auchatae tribe descended from Lipoxais, the Catiari and Traspians from Arpoxais, and the Paralatae (Royal Scythians) from Colaxais, who was the youngest brother.[52] According to Herodotus the Royal Scythians were the largest and most powerful Scythian tribe, and looked "upon all the other tribes in the light of slaves."[53]

Although scholars have traditionally treated the three tribes as geographically distinct, Georges Dumézil interpreted the divine gifts as the symbols of social occupations, illustrating his trifunctional vision of early Indo-European societies: the plough and yoke symbolised the farmers, the axe—the warriors, the bowl—the priests. The first scholar to compare the three strata of Scythian society to the Indian castes was Arthur Christensen. According to Dumézil, "the fruitless attempts of Arpoxais and Lipoxais, in contrast to the success of Colaxais, may explain why the highest strata was not that of farmers or magicians, but, rather, that of warriors."[54]

Warfare

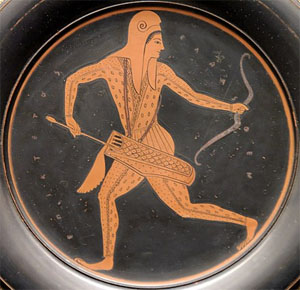

Scythian archers using the Scythian bow, Kerch (ancient Panticapeum), Crimea, 4th century BC. The Scythians were skilled archers whose style of archery influenced that of the Persians and subsequently other nations, including the Greeks.[55]

The Scythians were a warlike people. When engaged at war, almost the entire adult population, including a large number of women, participated in battle.[56] The Athenian historian Thucydides noted that no people in either Europe or Asia could resist the Scythians without outside aid.[56]

Scythians were particularly known for their equestrian skills, and their early use of composite bows shot from horseback. With great mobility, the Scythians could absorb the attacks of more cumbersome footsoldiers and cavalry, just retreating into the steppes. Such tactics wore down their enemies, making them easier to defeat. The Scythians were notoriously aggressive warriors. Ruled by small numbers of closely allied elites, Scythians had a reputation for their archers, and many gained employment as mercenaries. Scythian elites had kurgan tombs: high barrows heaped over chamber-tombs of larch wood, a deciduous conifer that may have had special significance as a tree of life-renewal, for it stands bare in winter.[citation needed]

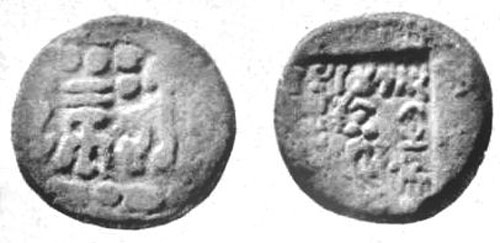

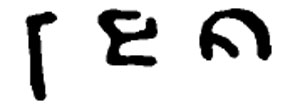

The Ziwiye hoard, a treasure of gold and silver metalwork and ivory found near the town of Sakiz south of Lake Urmia and dated to between 680 and 625 BC, includes objects with Scythian "animal style" features. One silver dish from this find bears some inscriptions, as yet undeciphered and so possibly representing a form of Scythian writing.[citation needed]

Scythians also had a reputation for the use of barbed and poisoned arrows of several types, for a nomadic life centred on horses—"fed from horse-blood" according to Herodotus—and for skill in guerrilla warfare.[citation needed]

Some Scythian-Sarmatian cultures may have given rise to Greek stories of Amazons. Graves of armed females have been found in southern Ukraine and Russia. David Anthony notes, "About 20% of Scythian-Sarmatian 'warrior graves' on the lower Don and lower Volga contained females dressed for battle as if they were men, a style that may have inspired the Greek tales about the Amazons."[57]

Metallurgy

Main article: Scythian metallurgy

Though a predominantly nomadic people for much of their history, the Scythians were skilled metalworkers. Knowledge of bronze working was present when the Scythian people formed, by the 8th century BC Scythian mercenaries fighting in the Near East had begun to spread knowledge of iron working to their homeland. Archeological sites attributed to the Scythians have been found to contain the remnants of workshops, slag piles, and discarded tools, all of which imply some Scythian settlements were the site of organized industry.[58][59]