Indo-Scythians

by JatLand.com

Accessed: 9/22/21

For specific research-work on the Scythian origin of the Jats, please visit: Indo-Scythian origin of the Jats.

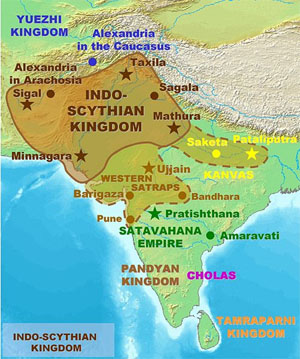

Territories (full line) and expansion (dotted line) of the Indo-Scythians Kingdom at its greatest extent

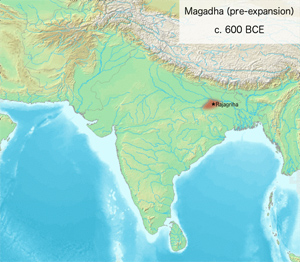

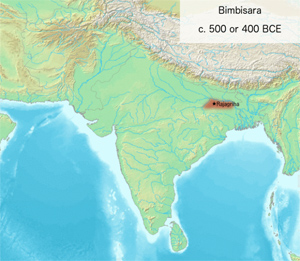

The Indo-Scythians are a branch of the Indo-Iranian Sakas (Scythians) were rulers in Central Asia. [1] They migrated from southern Siberia into Bactria, Sogdiana, Arachosia, Gandhara, Kashmir, Punjab, and into parts of Western and Central India, Gujarat and Rajasthan, from the middle of the 2nd century BCE [200 to 101 BCE] to the 4th century CE. The first Saka King in India was Maues or Moga who established Saka power in Gandhara and gradually extended supremacy over north-western India. Indo-Scythian rule in India ended with the last Western Satrap Rudrasimha III in 395 CE.

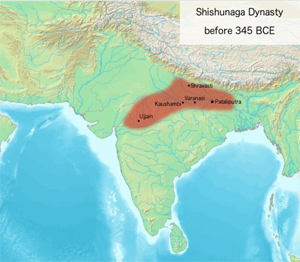

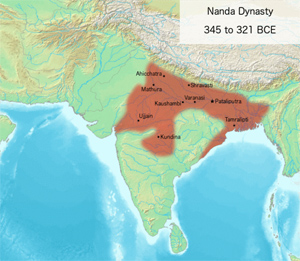

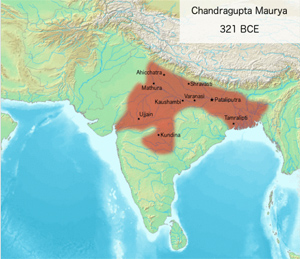

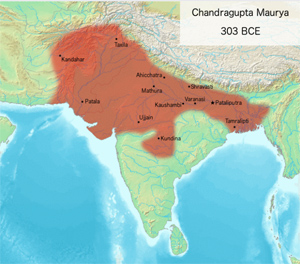

Herodotus reveals that the Scythians as far back as the 5th century B.C. had political control over Central Asia and the northern subcontinent up to the river Ganges. Later Indo-Scythic clans and dynasties (e.g. Mauryas, Rajputs) extended their control to other tracts of the northern subcontinent. The largest Saka imperial dynasties of Sakasthan include the Satraps (204 BC to 78 AD), Kushanas (50 AD - 380), Virkas (420 AD - 640) while others like the Mauryas (324 - 232 BC) and Dharan-Guptas (320 AD - 515) expanded their empires towards the east.[2]

According to Ethnographers and historians like Cunningham, Todd, Ibbetson, Elliot, Ephilstone, Dahiya, Dhillon, Banerjea, etc., the agrarian and artisan communities (e.g. Jats, Gujars, Ahirs, Rajputs, Lohars, Tarkhans etc.) of the entire west are derived from the war-like Scythians;[2] who settled north-western and western South Asia in successive waves between 500 BC to 500 AD.

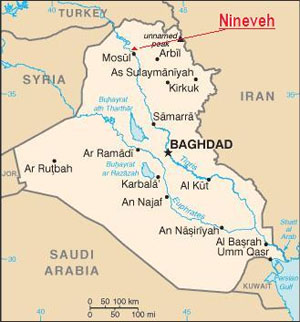

Trevaskis put the date of Scythian migrations into India approximately from 600 BC to 600 AD. Trevaskis wrote, "Their (Scythians') successive onslaughts proved the ruin of Assyria, and soon after the fall of Nineveh, BC 606, a vast horde of them burst into Punjab."[3]

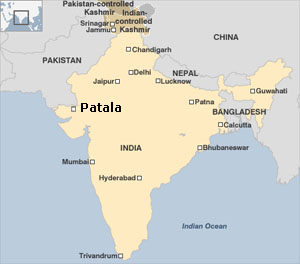

The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica says that a Scythian horde was seated at Pattala on the Indus, in 625 BC; this may have been the Sibi.

It is worth noticing that as early as Pāṇini's (पाणिनि) era, the places in-and-around Sialkot are known to have Sakian etymology i.e. ending in "kantha" — Chihankantha, Madarakantha, etc. Even the Archaeological Survey Report of India unearths the fact that the ancient name for Sialkot was Sakala.[4][5] Also, Sakala is thought to be "Saka" town by Przyluski and Tarn.[6][7]

Saka clan is found in Afghanistan. Saka, usually associated with the Ladi, represents the Sakai (Sacae) of the Persians and Greeks, after whom Sistan was named Sakastan[8]

H. W. Bellew writes that Ishak, the Musalman disguise of Saka or Sak, represents the Persian Saka and Greek Sakai, the Skythian conquerors who gave their name to Sistan, the Sagistan of Arab writers, and Sakasthan of Indians. Another branch of Saka Skythians is found in the Sagpae and Sagpue Hazara clans, before noticed. [9]

The invasion of India by Scythian tribes from Central Asia, often referred to as the Indo-Scythian invasion, played a significant part in the history of India as well as nearby countries. In fact, the Indo-Scythian war is just one chapter in the events triggered by the nomadic flight of Central Asians from conflict with Chinese tribes which had lasting effects on Bactria, Kabol, Parthia and India as well as far off as Rome in the west.

The Scythian groups that invaded India and set up various kingdoms, may have included besides the Sakas other allied tribes, such as the Parama Kambojas, Bahlikas, Rishikas and Paradas.

Origins

The ancestors of the Indo-Scythians are thought to be Sakas (Scythian) tribes, originally settled in southern Siberia, in the Ili river area.

Legendary Origins of the Scythians

N. S. Gill writes:

"A rightly skeptical Herodotus says the Scythians claimed the first man to exist in the region -- at a time when it was desert and about a millennium before Darius of Persia -- was named Targitaos. He was the son of Zeus and the daughter of the river Borysthenes. Targitaos had three sons from whom the tribes of the Scythians sprang. Another legend Herodotus reports connects the Scythians with Hercules and Echidna."[10]

Etymology

N. S. Gill writes:

"The Greek epic poet Hesiod called the northern tribes hippemolgi 'mare milkers'. The Greek historian Herodotus refers to the European Scythians as Scythians and the eastern ones as Sacae. The name Scythians and Sacae applied to themselves was Skudat 'archer'. Later, the Scythians were sometimes called Getae. The Persians also called the Scythians, Sakai. Scythians, who attacked the kingdom of Urartu in Armenia, were called Ashguzai or Ishguzai by the Assyrians. The Scythians may have been the Biblical Ashkenaz."[11]

"The first to describe the life style of these tribes was a Greek researcher, Herodotus, who lived in the fifth century BCE. Although he concentrates on the tribes living in modern Ukraine, which he calls Scythians, we may extrapolate his description to people in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and possibly Mongolia, even though Herodotus usually calls these eastern nomads 'Sacae'. In fact, just as the Scythians and the Sacae shared the same life style, they had the same name: in their own language, which belonged to the Indo-Iranian family, they called themselves Skudat ('archers'?). The Persians rendered this name as Sakâ and the Greeks as Skythai. The Chinese called them, at a later stage in history, Sai."[12][13]

Yuezhi expansion

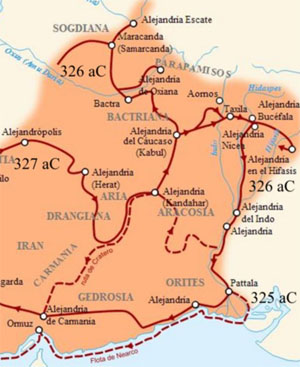

In the second century BCE, a fresh nomadic movement started among the Central Asian tribes, producing lasting effects on the history of Rome in Europe and Bactria, Kabol, Parthia and India in the east. Recorded in the annals of the Han dynasty and other Chinese records, this great tribal movement began after the Yuezhi Chinese tribe fled westwards after their defeat by the neighbouring Hiung-nu, creating a domino effect as the Yuezhi displaced other central Asian tribes in their path.

According to these ancient sources Mao-tun of the Hsiung-nu tribe of Mongolia attacked the Yue-chi and evicted them from their homeland Kansu (Nan-shan).[14] Leaving behind a remnant of their number, most of the population moved westwards, and following the route north of Takla Makan, entered the lands of the Haumavarka Sakas of Issyk-kul Lake through the passes of Tien-shan. Unable to withstand the assault, the Haumavarka Sakas allowed the Yue-chi to settle in their lands. In the years to come, the Haumavarka Sakas (Sakas of Wu-sun?) sought the help of the Hsiung-nu people and evicted the Yue-chi.

Even so, the initial clash with the invading Yue-chi caused a large group of the Haumavarka Shakas to leave their ancestral home. These Sakas journeyed through Tashkent and Ferghana (Sogdiana) (inhabited by the Sugud or Shulik tribe of the Iranians) and occupied the Doab of Oxus and Jaxartes, also overrunning the Greek kingdom of Bactria, occupying most of its western parts.[15] Others suggest Tukhara (India and Central Asia, 1955, p 125, Dr P. C. Bagch). Dr D. C. Sircar reconciles the difference by suggesting that Ta-hia referred to Tukhara and the eastern parts of Bactria.[16]

After being defeated and evicted by the joint forces of the Wu-sun and Hsiung-nu people, the Ta Yue-chis also moved southwards, overrunning in their path the Rishikas, Parama-Kambojas, Lohas and other allied Scythian clans living in the Transoxian regions as far Fargana. Many fled in a southwesterly direction and joined the Haumavarka Sakas in Bactria. The Yue-chi followed behind. Once again under extreme pressure, the Sakas and other allied Scythian groups including the Kambojas were forced to leave Bactria.

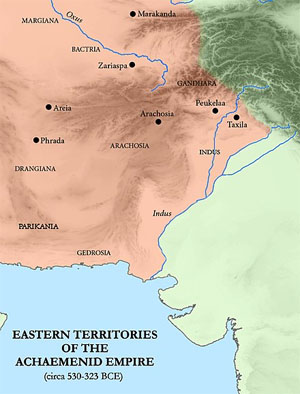

They first tried to enter India via the Kabol valley but were vigorously opposed by the Greek powers there. Rebuffed, the clans turned westwards to Herat and then took a southerly direction, reaching Helmund valley (Sigal) in south-west Afghanistan, the region later called Sakasthan or Seistan. Scholars believe that this Scythian migration through Herat to Drangiana was accompanied by groups of Kambojas (Parama-Kambojas), Rishikas and other allied tribes from Transoxiana that were also displaced by the Yue-chi.[17][18]

Around 175 BCE, the Yuezhi tribes (probable related to the Tocharians) who lived in eastern Tarim Basin area, were defeated by the Hiung-nu (Huns) tribes, and had to migrate towards the West into the Ili river area. There, they displaced the Sakas, who had to migrate south into Ferghana and Sogdiana. According to the Chinese historical chronicles (who call the Sakas, "Sai" 塞):

"The Yuezhi attacked the king of the Sai who moved a considerable distance to the south and the Yuezhi then occupied his lands" (Han Shu 61 4B).

Sometime after 155 BCE, the Yuezhi were again defeated by an alliance of the Wusun and the Hiung-nu, and were forced to move south, again displacing the Scythians, who migrated south towards Bactria, and south-west towards Parthia and Afghanistan.

The Sakas seem to have entered the territory of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom around 145 BCE, where they burnt to the ground the Greek city of Alexandria on the Oxus. The Yuezhi remained in Sogdiana on the northern bank of the Oxus, but they became suzerains of the Sakas in Bactrian territory, as described by the Chinese ambassador Zhang Qian who visited the region around 126 BCE.

In Parthia, between 138 BCE-124 BCE, the Sakas tribes of the Massagetae and Sacaraucae came into conflict with the Parthian Empire, winning several battles, and killing successively king Phraates II and king Artabanus I of Parthia.

The Parthian king Mithridates II of Parthia finally retook control of Central Asia, first by defeating the Yuezhi in Sogdiana in 115 BCE, and then defeating the Scythians in Parthia and Seistan around 100 BCE.

After their defeat, the Yuezhi tribes migrated into Bactria, which they were to control for several centuries, and from which they later conquered northern India to found the Kushan Empire. The area of Bactria they settled came to be known as Tokharistan, since the Yuezhi were called Tocharians by the Greeks.

DNA study on Y-STR Haplogroup Diversity in the Jat Population

David G. Mahal and Ianis G. Matsoukas[19] conducted a scientific study on Y-STR Haplogroup Diversity in the Jat Population of which brief Conclusion is as under:

The Jats represent a large ethnic community that has inhabited the northwest region of India and Pakistan for several thousand years. It is estimated the community has a population of over 123 million people. Many historians and academics have asserted that the Jats are descendants of Aryans, Scythians, or other ancient people that arrived and lived in northern India at one time. Essentially, the specific origin of these people has remained a matter of contention for a long time. This study demonstrated that the origins of Jats can be clarified by identifying their Y-chromosome haplogroups and tracing their genetic markers on the Y-DNA haplogroup tree. A sample of 302 Y-chromosome haplotypes of Jats in India and Pakistan was analyzed. The results showed that the sample population had several different lines of ancestry and emerged from at least nine different geographical regions of the world. It also became evident that the Jats did not have a unique set of genes, but shared an underlying genetic unity with several other ethnic communities in the Indian subcontinent. A startling new assessment of the genetic ancient origins of these people was revealed with DNA science.

The human Y-chromosome provides a powerful molecular tool for analyzing Y-STR haplotypes and determining their haplogroups which lead to the ancient geographic origins of individuals. For this study, the Jats and 38 other ethnic groups in the Indian subcontinent were analyzed, and their haplogroups were compared. Using genetic markers and available descriptions of haplogroups from the Y-DNA phylogenetic tree, the geographic origins and migratory paths of their ancestors were traced.

The study demonstrated that based on their genetic makeup, the Jats belonged to at least nine specific haplogroups, with nine different lines of ancestry and geographic origins. About 90% of the Jats in our sample belonged to only four different lines of ancestry and geographic origins:

1. Haplogroup L (36.8%)- The origins of this haplogroup can be traced to the rugged and mountainous Pamir Knot region in Tajikistan.

2. Haplogroup R (28.5%): From somewhere in Central Asia, some descendants of the man carrying the M207 mutation on the Y chromosome headed south to arrive in India about 10,000 years ago (Wells, 2007). This is one of the largest haplogroups in India and Pakistan. Of its key subclades, R2 is observed especially in India and central Asia.

3. Haplogroup Q (15.6%): With its origins in central Asia, descendants of this group are linked to the Huns, Mongols, and Turkic people. In Europe it is found in southern Sweden, among Ashkenazi Jews, and in central and Eastern Europe such as, the Rhône-Alpes region of France, southern Sicily, southern Croatia, northern Serbia, parts of Poland and Ukraine.

4. Haplogroup J (9.6%): The ancestor of this haplogroup was born in the Middle East area known as the Fertile Crescent, comprising Israel, the West Bank, Jordon, Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. Middle Eastern traders brought this genetic marker to the Indian subcontinent (Kerchner, 2013).

5.-9. Haplogroups E, G, H, I, T (9.5%): The ancestors of the remaining five haplogroups E, G, H, I, and T can be traced to different parts of Africa, Middle East, South Central Asia, and Europe (ISOGG, 2016).

Therefore, attributing the origins of this entire ethnic group to loosely defined ancient populations such as, Indo-Aryans or Indo-Scythians represents very broad generalities and cannot be supported. The study also revealed that even with their different languages, religions, nationalities, customs, cuisines, and physical differences, the Jats shared their haplogroups with several other ethnic groups of the Indian subcontinent, and had the same common ancestors and geographic origins in the distant past. Based on recent developments in DNA science, this study provided new insights into the ancient geographic origins of this major ethnic group in the Indian subcontinent. A larger dataset, particularly with more representation of Muslim Jats, is likely to reveal some additional haplogroups and geographical origins for this ethnic group.

Jat clans from Sakas

Hukum Singh Panwar [20] writes:

The next source at our disposal is "The Political and social Movements in Ancient Panjab" written by Dr. Buddha Prakash who has meticulously sorted out the Saka tribes which were assimilated in our society. However, with a few exceptions, he does not declare them Jats whereas our experience and a perusal of the names or Gotras of the Jat tribes unerringly attest that they also are included in the Jats. According to him, the Saka Tigarkhauda are the Massagetae (Maha Jats) and the Soma or Haumavarka Sakas or the Amyrgians of the Greek writers (V.S. Aggarwal, 1963: 443,467) or the Sakaraucae of Wessendonk or the Sakarucae of Marquart are the Baltis or Ladakhis Somas of Afghanistan and the Virkas of the Panjab, the last two of whom are undoubtedly Jats.

The Srnjayas or the Parthians of the Mahabharata and of Shafer (1954: 138.) or the Sarangai of Herodotus or the Zranke of the Achaemenian Inscriptions or the Sir-re-anke of the Elamite records or the Saragoi of Arrian or the Dragiane of Strabo (in Seistan) or the descendents of Narishyanta, the progenitor of the Sakas, (are the Jats), known in the Mahabharata and the Rigveds as Srnjayas, the sons of the Sickle (Hewitt, 1972: 481) (survived by the Siringi or Singar or Singhar or Singhal or Sangar or Sanghar tribes in the Jats).

The Neuris (Nur or Nuri Jats), Salva (Salu Jats), Arjunayan or the Kathoi and Kathoi and Kathroi (Kshatriyas or Khatri Jats) are the Jun and Rajayan tribes in the Jats. The Karaskaras (Upadhyaya, 1973: 84-Guptas or Karaskara Jats) are modern Khokhars. The Thakurs or Thakaras or Thakran or Thagora or Taugara or Tokhi are from the Tukharas (Yueh-Chih) and the Soi and Sikkas, Kajal or Kuzul or Khosla, Kanka, now Kangs; Sulikas or Solgi or Solkah or Solanki or Sulki; Lampaka or Lambaka or Lamba; Kirata (or Kira or Kirah) are mostly from the Sakas of Sogdiana. The Mehra and Moga or Mogha are from the Megas (the Saka Brahmans). Chaul (or Chol or Cholak), Jaula, Tomar, Khatri, Khan or Khanua and Sahi, Wusun or Wasan or

The Jats: Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations: End of page 325

Wassan are from the White Ephthalites or Huns. Hun or Hoon is also a tribe of the Jats and Khatris. The Her Jats are the descendants of the Heraios Kushanas from the Sakas.

According to Vishwa Mitra Mohan (1976: 84f), the Gakhar Jats are a fierce Scythian tribe spread over Sindh, eastern and western Panjab up to Khyber pass in the Frontier Province. The Khar or Kher or Kharata or Khareta and possibly the Kharb Jats are the descendants of the Saka Ksharatas mentioned in the Indian Epigraphs or the Karatai Scythians. In the end, it may be said that B.S. Dahiya has done a good job and his book is a compendium of the Jat tribes living in India and abroad. But lack of space does not allow us to repeat what he has laboured to bring before us from the misty lap of time and space.

Settlement in Sakastan

Map of Sakastan around 100 BCE

The Sakas settled in areas of southern Afghanistan, still called after them Sakastan. From there, they progressively expanded into the Indian subcontinent, where they established various kingdoms, and where they are known as "Indo-Scythians".

The Arsacid emperor Mithridates II (c 123-88/87 BCE) had scored many successes against the Scythians and added many provinces to the Parthian empire,[21] and apparently the Bactrian Scythian hordes were also conquered by him. A section of these people moved from Bactria to Lake Helmond in the wake of Yue-chi pressure and settled about Drangiana (Sigal), a region which later came to be called "Sakistana of the Skythian (Scythian) Sakai",[22] towards the end of first century BCE.[23] The region is still known as Seistan.

Sakistan or Seistan of Drangiana may not only have been the habitat of the Saka alone but may also have contained population of the Pahlavas and the Kambojas.[24] The Rock Edicts of king Ashoka only refer to the Yavanas, Kambojas and the Gandharas in the northwest, but no mention is made of the Sakas, who immigrated in the region more than a century later. It is thus likely that the immigrant Saka populations who settled in Afghanistan did so among or near the Kambojas and nearby Greek cities.[25] Numerous scholars believe that during centuries immediately preceding Christian era, there had occurred extensive social and cultural admixture among the Kambojas and Yavanas; the Sakas and Pahlavas; and the Kambojas, Sakas, and Pahlavas etc.... such that their cultures and social customs had become almost identical.

The presence of the Sakas in Sakastan in the 1st century BCE is mentioned by Isidore of Charax in his "Parthian stations". He explained that they were bordered at that time by Greek cities to the east (Alexandria of the Caucasus and Alexandria of the Arachosians), and the Parthian-controlled territory of Arachosia to the south:

"Beyond is Sacastana of the Scythian Sacae, which is also Paraetacena, 63 schoeni. There are the city of Barda and the city of Min and the city of Palacenti and the city of Sigal; in that place is the royal residence of the Sacae; and nearby is the city of Alexandria (and nearby is the city of Alexandropolis), and six villages." Parthian stations, 18.[26]

Kantha Ending names

V. S. Agrawala[27] writes that Panini mentions village name in category ending Kanthā (IV.2.142) - Panini gives the interesting information that Kantha ending was in use in Ushinara (II.4.20)

[p.68]: and Varnu (Bannu (IV.2.103). He names the following places:

Chihaṇakantha, Maḍarakantha, Vaitulakantha, Paṭatkakantha, Vaiḍalikarṇakantha, Kukkuṭakantha, Chitakaṇakakantha.

Kanthā was a Saka word for a town as in the expression kadahvara= kanthāvara occurring in a Khroshthi inscription. "Here belongs Sogdian expression kanda- "city" and Saka kantha "city" earlier attested in Markantha". H W Bellew also points out that Persian word Kand, Khotanese Kanthā, Sogdian, Buddhist Sanskrit kndh Pasto Kandai, Asica (the dialect of Rishikas or Yuchi) kandā are all akin to Sanskrit Kanthā.

It may be noted that in the time of Panini and as stated by Darius I, in his Inscriptions, the Shakas were living beyond Oxus. That region naturally still abounds in Kanthā-ending place names, such as Samarkand, Khokand, Chimkand, Tashkent, Panjkand, Yarkand, all indicating Saka influence.

The Mahabharata speaks of the Sakas as living in this region, named by it as Sakadvipa, and particularly mentions places like Chakshu (=Oxus), Kumud (=Komedai of Herodotus, a mountain in the Shaka country), Himavat (=Hemodan mountain), Sita (=Yarkand River, Kaumara (=Komarai of Herodotus), Mashaka (=Masagetai of Strabo, Rishika (=Asioi, Tushara (=Tokarai).

Panini must also have known Shakas, not in Seistan but in their original home in Central Asia.

[p.69]: How a string of kanthā-ending place names was found in Ushinara country in the heart of Punjab, is an unexplained problem. It points to an event associated with Shaka history even before Panini, possibly an intrusion which left its relics in place names before the Saka contact with India in the second century BC. Katyayana mentions Shakandhu and Karkandhu, two kinds of wells of the Shakas and Karkas (Karkians), which may be identified as the stepped well (vāpī) and the Persian wheel (arghaṭṭa) well respectively.

Lastly we owe to the Kasika the following names ending in kanthā: Saushamikantha and Āhvarakantha both in Ushinara country in Vahika (II.4.20).

Indo-Scythian kingdoms

Abiria to Surastrene

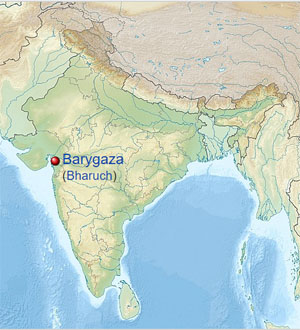

The first Indo-Scythian kingdom in the Indian subcontinent occupied the southern part of Pakistan (which they accessed from southern Afghanistan), in the areas from Abiria (Sindh) to Surastrene (Gujarat), from around 110 to 80 BCE. They progressively further moved north into Indo-Greek territory until the conquests of Maues, circa 80 BCE.

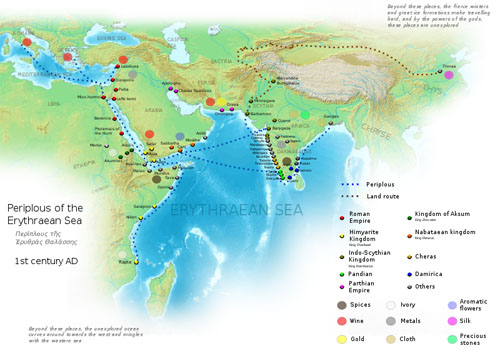

The 1st century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describes the Scythian territories there:

"Beyond this region (Gedrosia), the continent making a wide curve from the east across the depths of the bays, there follows the coast district of Scythia, which lies above toward the north; the whole marshy; from which flows down the river Sinthus, the greatest of all the rivers that flow into the Erythraean Sea, bringing down an enormous volume of water (...) This river has seven mouths, very shallow and marshy, so that they are not navigable, except the one in the middle; at which by the shore, is the market-town, Barbaricum. Before it there lies a small island, and inland behind it is the metropolis of Scythia, Minnagara."[28]

The Indo-Scythians ultimately established a kingdom in the northwest, based in Taxila, with two Great Satraps, one in Mathura in the east, and one in [Surastrene (Gujarat) in the southwest.

In the southeast, the Indo-Scythians invaded the area of Ujjain, but were subsequently repelled in 57 BCE by the Malwa king Vikramaditya. To commemorate the event Vikramaditya established the Vikrama era, a specific Indian calendar starting in 57 BCE. More than a century later, in 78 CE the Sakas would again invade Ujjain and establish the Saka era, marking the beginning of the long-lived Saka Western Satraps kingdom.[29]

Vikramaditya (IAST: Vikramāditya) was an emperor of ancient India. Often characterized as a legendary king, he is known for his generosity, courage, and patronage of scholars. Vikramaditya is featured in hundreds of traditional stories including those in Baital Pachisi and Singhasan Battisi. Many describe him as a universal ruler, with his capital at Ujjain (Pataliputra or Pratishthana in a few stories).

According to popular tradition, Vikramaditya began the Vikrama Samvat era in 57 BCE after defeating the Shakas, around the first century BCE. However, this era is identified as "Vikrama Samvat" after the ninth century CE....

Proponents of this theory say that Vikramaditya is mentioned in works dating to before the Gupta era, including Brihatkatha and Gatha Saptashati....

Critics of this theory say that Gatha Saptashati shows clear signs of Gupta-era interpolation [an entry or passage in a text that was not written by the original author.]. According to A. K. Warder, Brihatkathamanjari and Kathasaritsagara are "enormously inflated and deformed" recensions of the original Brihatkatha. The early Jain works do not mention Vikramaditya and the navaratnas have no historical basis as the nine scholars do not appear to have been contemporary figures. Legends surrounding Vikramaditya are contradictory, border on the fantastic and are inconsistent with historical facts; no epigraphic, numismatic or literary evidence suggests the existence of a king with the name (or title) of Vikramaditya around the first century BCE. Although the Puranas contain genealogies of significant Indian kings, they do not mention a Vikramaditya ruling from Ujjain or Pataliputra before the Gupta era. There is little possibility of an historically-unattested, powerful emperor ruling from Ujjain around the first century BCE among the Shungas (187–78 BCE), the Kanvas (75–30), the Satavahanas (230 BCE–220 CE), the Shakas (c. 200 BCE – c. 400 CE) and the Indo-Greeks (180 BCE–10 CE)....

Max Müller believed that the Vikramaditya legends were based on the sixth-century Aulikara king Yashodharman. The Aulikaras used the Malava era (later known as Vikrama Samvat) in their inscriptions. According to Rudolf Hoernlé, the name of the Malava era was changed to Vikramaditya by Yashodharman. Hoernlé also believed that Yashodharman conquered Kashmir and is the Harsha Vikramaditya mentioned in Kalhana's Rajatarangini. Although Yashodharman defeated the Hunas (who were led by Mihirakula), the Hunas were not the Shakas; Yashodharman's capital was at Dasapura (modern Mandsaur), not Ujjain. There is no other evidence that he inspired the Vikramaditya legends....

Some legends describe him as a liberator of India from mlechchha invaders; the invaders are identified as Shakas in most, and the king is known by the epithet Shakari (IAST: Śakāri; "enemy of the Shakas")....

Kshemendra's Brihatkathamanjari and Somadeva's 11th-century Kathasaritsagara, both adaptations of Brihatkatha, contain a number of legends about Vikramaditya. Each legend has several fantasy stories within a story, illustrating his power.

The first legend mentions Vikramaditya's rivalry with the king of Pratishthana. In this version, that king is named Narasimha (not Shalivahana) and Vikramaditya's capital is Pataliputra (not Ujjain). According to the legend, Vikramaditya was an adversary of Narasimha who invaded Dakshinapatha and besieged Pratishthana; he was defeated and forced to retreat. He then entered Pratishthana in disguise and won over a courtesan. Vikramaditya was her lover for some time before secretly returning to Pataliputra. Before his return, he left five golden statues which he had received from Kubera at the courtesan's house. If a limb of one of these miraculous statues was broken off and gifted to someone, the golden limb would grow back....

Paramara-era legends associate the Paramara rulers with legendary kings, in order to enhance the Paramara imperial claims. The Bhavishya Purana, an ancient Hindu text which has been edited till as late as 19th century, connects Vikramaditya to the Paramaras. According to the text (3.1.6.45-7.4), the first Paramara king was Pramara (born from a fire pit at Mount Abu, thus an Agnivansha). Vikramaditya, Shalivahana and Bhoja are described as Pramara's descendants and members of the Paramara dynasty....

Few references to Vikramaditya exist in Jain literature before the mid-12th century, although Ujjain appears frequently. After the Jain king Kumarapala (r. 1143–1172), Jain writers started to compare Kumarapala to Vikramaditya. By the end of the 13th century, legends featuring Vikramaditya as a Jain emperor began surfacing. A major theme in Jain tradition is that the Jain acharya Siddhasena Divakara converted Vikramaditya to Jainism.....

Many legends, particularly Jain legends, associate Vikramaditya with Shalivahana of Pratishthana (another legendary king). In some he is defeated by Shalivahana, who begins the Shalivahana era; in others, he is an ancestor of Shalivahana. A few legends call the king of Pratishthana "Vikramaditya". Political rivalry between the kings is sometimes extended to language, with Vikramaditya supporting Sanskrit and Shalivahana supporting Prakrit....

In a medieval Tamil legend Vikramaditya has 32 marks on his body, a characteristic of universal emperors. A Brahmin in need of Alchemic quicksilver tells him that it can be obtained if the emperor offers his head to the goddess Kamakshi of Kanchipuram. Although Vikramaditya agrees to sacrifice himself, the goddess fulfills his wish without the sacrifice....

In Jyotirvidabharana (22.10), a treatise attributed to Kalidasa, nine noted scholars (the Navaratnas) were at Vikramaditya's court...

However, many scholars consider Jyotirvidabharana a literary forgery written after Kalidasa's death. According to V. V. Mirashi, who dates the work to the 12th century, it could not have been composed by Kalidasa because it contains grammatical errors. There is no mention of such Navaratnas in earlier literature, and D. C. Sircar calls Jyotirvidabharana "absolutely worthless for historical purposes".

-- Vikramaditya, by Wikipedia

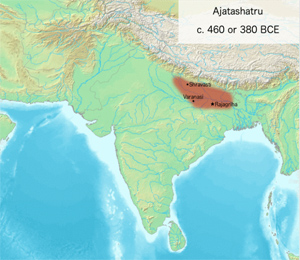

Gandhara and Punjab

The presence of the Scythians in north-western India during the 1st century BCE was contemporary with that of the Indo-Greek Kingdoms there, and it seems they initially recognized the power of the local Greek rulers.

Maues first conquered Gandhara and Taxila around 80 BCE, but his kingdom disintegrated after his death. In the east, the Indian king Vikrama retook Ujjain from the Indo-Scythians, celebrating his victory by the creation of the Vikrama Era (starting 58 BCE). Indo-Greek kings again ruled after Maues, and prospered, as indicated by the profusion of coins from kings Apollodotus II and Hippostratos. Not until Azes I, in 55 BCE, did the Indo-Scythians take final control of northwestern India, with his victory over Hippostratos.

Mathura area ("Northern Satraps")

In central India, the Indo-Scythians conquered the area of Mathura over Indian kings around 60 BCE. Some of their satraps were Hagamasha and Hagana, who were in turn followed by the Saca Great Satrap Rajuvula.

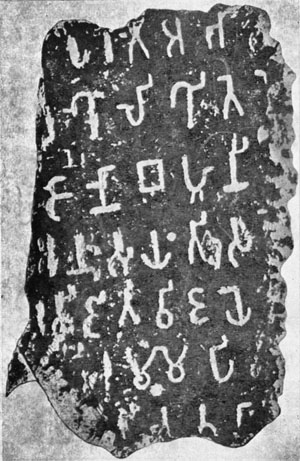

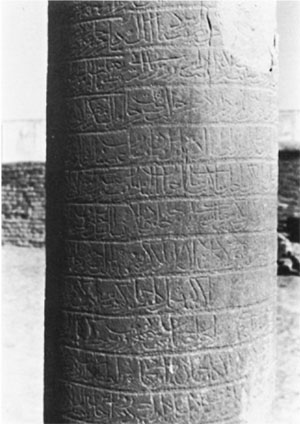

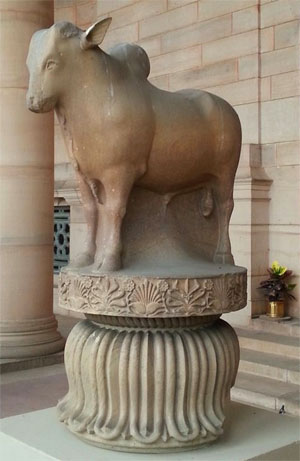

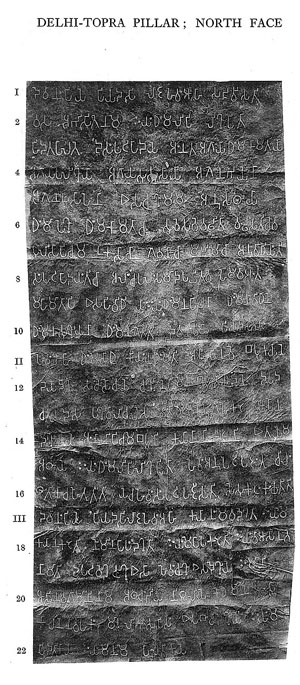

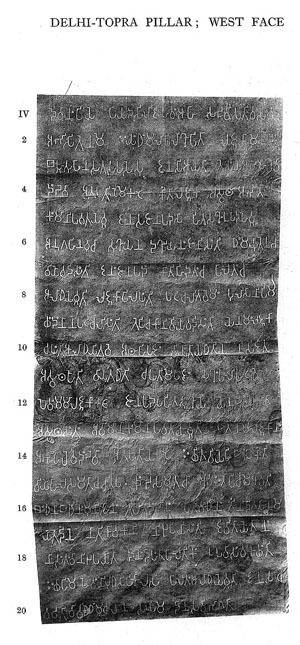

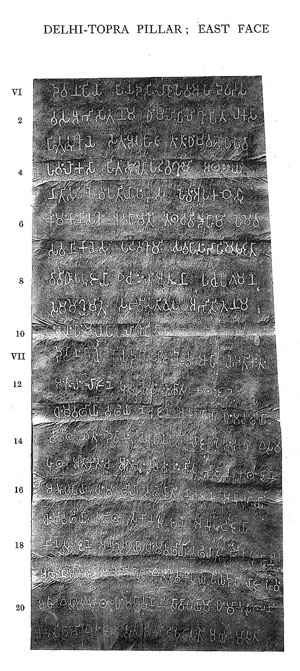

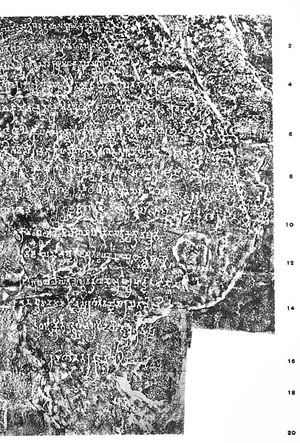

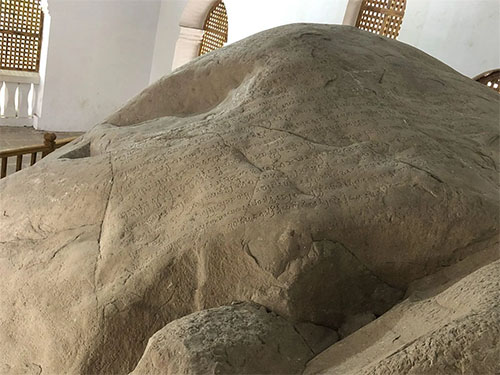

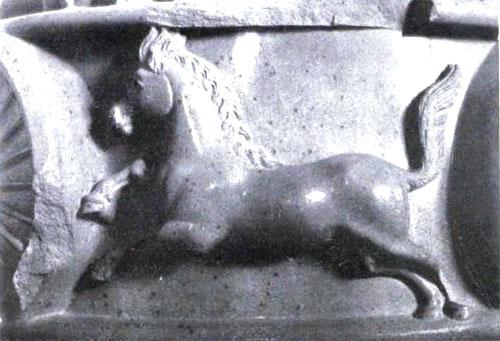

The Mathura lion capital, an Indo-Scythian sandstone capital in crude style, from Mathura in Central India, and dated to the 1st century CE, describes in kharoshthi the gift of a stupa with a relic of the Buddha, by Queen Nadasi Kasa, the wife of the Indo-Scythian ruler of Mathura, Rajuvula. The capital also mentions the genealogy of several Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura.

Rajuvula apparently eliminated the last of the Indo-Greek kings Strato II around 10 CE, and took his capital city, Sagala.

The coinage of the period, such as that of Rajuvula, tends to become very crude and barbarized in style. It is also very much debased, the silver content becoming lower and lower, in exchange for a higher proportion of bronze, an alloying technique (billon) suggesting less than wealthy finances.

The Mathura Lion Capital inscriptions attest that Mathura fell under the control of the Sakas. The inscriptions contain references to Kharaosta Kamuio and Aiyasi Kamuia. Yuvaraja Kharostes (Kshatrapa) was the son of Arta as is attested by his own coins.[30] Arta is stated to be brother of king Moga or Maues.[31] Princess Aiyasi Kambojaka, also called Kambojika, was the chief queen of Shaka Mahakshatrapa Rajuvula. Kamboja presence in Mathura is also verified from some verses of epic Mahabharata which are believed to have been composed around this period.[32] This may suggest that Sakas and Kambojas may have jointly ruled over Mathura/Uttara Pradesh. It is revealing that Mahabharata verses only attest the Kambojas and Yavanas as the inhabitants of Mathura, but do not make any reference to the Sakas.[33] Probably, the epic has reckoned the Sakas of Mathura among the Kambojas (Dr J. L. Kamboj) or else have addressed them as Yavanas, unless the Mahabharata verses refer to the previous period of invasion occupation by the Yavanas around 150 BCE.

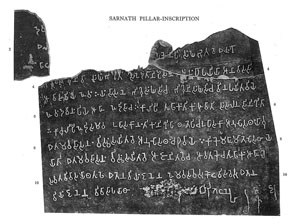

The Indo-Scythian satraps of Mathura are sometimes called the "Northern Satraps", in opposition to the "Western Satraps" ruling in Gujarat and Malwa. After Rajuvula, several successors are known to have ruled as vassals to the Kushans, such as the "Great Satrap" Kharapallana and the "Satrap" Vanaspara, who are known from an inscription discovered in Sarnath, and dated to the 3rd year of Kanishka (circa 130 CE), in which they were paying allegiance to the Kushans.[34]

Pataliputra

The text of the Yuga Purana describes an invasion of Pataliputra by the Scythians sometimes during the 1st century BCE, after seven greats kings had ruled in succession in Saketa following the retreat of the Yavanas. The Yuga Purana explains that the king of the Sakas killed one fourth of the population, before he was himself slain by the Kalinga king Shata and a group of Sabalas (Sabaras).[35]

Kushan and Indo-Parthian conquests

After the death of Azes II, the rule of the Indo-Scythians in northwestern India finally crumbled with the conquest of the Kushans, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi who had lived in Bactria for more than a century, and were now expanding into India to create a Kushan Empire. Soon after, the Parthians invaded from the west. Their leader Gondophares temporarily displaced the Kushans and founded the Indo-Parthian Kingdom that was to last towards the middle of the 1st century CE.

The Kushans ultimately regained northwestern India from around 75 CE, and the area of Mathura from around 100 CE, where they were to prosper for several centuries.

Western Kshatrapas legacy

The Indo-Scythians continued to hold the area of Seistan until the reign of Bahram II (276-293 CE), and held several areas of India well into the 1st millennium: Kathiawar and Gujarat were under their rule until the 5th century under the designation of Western Kshatrapas, until they were eventually conquered by the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II (also called Vikramaditya).

The Brihat-Katha-Manjari of the Kshmendra (10/1/285-86) informs us that around 400 CE the Gupta king Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II) had unburdened the sacred earth of the Barbarians like the Shakas, Mlecchas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Tusharas, Parasikas, Hunas, etc. by annihilating these sinners completely.

The 10th century CE Kavyamimamsa of Raj Shekhar (Ch 17) still lists the Shakas, Tusharas, Vokanas, Hunas, Kambojas, Bahlikas, Pahlavas, Tangana, Turukshas, etc. together and states them as the tribes located in the Uttarapatha division.

Indo-Scythian coinage

Silver tetradrachm of the Indo-Scythian King Maues (85-60 BCE).

Indo-Scythian coinage is generally of a high artistic quality, although it clearly deteriorates towards the desintegration of Indo-Scythian rule around 20 CE (coins of Rajuvula). A fairly qualitative but rather stereotypes coinage would continue with the Western Satraps until the 4th century CE.

Indo-Scythian coinage is generally quite realistic, artistically somewhere between Indo-Greek and Kushan coinage. It is often suggested Indo-Scythian coinage benefited from the help of Greek celators (Boppearachchi).

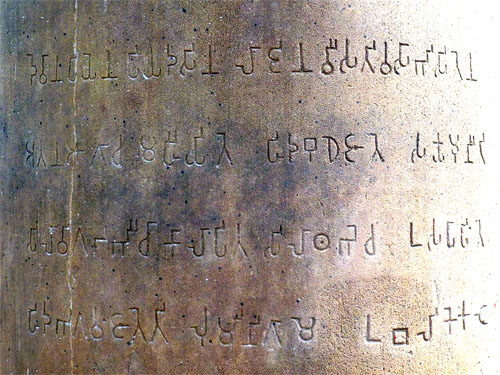

Indo-Scythian coins essentially continue the Indo-Greek tradition, bu using the Greek language on the obverse and the Kharoshthi language on the reverse. The portrait of the king is never shown however, and is replaced by depictions of the king on horse (and sometimes on camel), or sometimes sitting cross-legged on a cushion. The reverse of their coins typically show Greek divinities.

Buddhist symbolism is present throughout Indo-Scythian coinage. In particular, they adopted the Indo-Greek practice since Menander I of showing divinities forming the vitarka mudra with their right hand (as for the mudra-forming Zeus on the coins of Maues or Azes II), or the presence of the Buddhist lion on the coins of the same two kings, or the triratana symbol on the coins of Zeionises.

Depiction of Indo-Scythians

Azilises on horse, wearing a tunic.

Besides coinage, few works of art are known to indisputably represent Indo-Scythians. Indo-Scythians rulers are usually depicted on horseback in armour, but the coins of Azilises show the king in a simple, undecorated, tunic.

Several Gandharan sculptures also show foreigner in soft tunics, sometimes wearing the typical Scythian cap. They stand in contrast to representations of Kushan men, who seem to wear thicks, rigid, tunics, and who are generally represented in a much more simplistic manner[36]

Buner reliefs

Indo-Scythian soldiers in military attire are sometimes represented in Buddhist friezes in the art of Gandhara (particularly in Buner reliefs). They are depicted in ample tunics with trousers, and have heavy straight sword as a weapon. They wear a pointed hood (the Scythian cap or bashlyk), which distinguishes them from the Indo-Parthians who only wore a simple fillet over their bushy hair,[37] and which is also systematically worn by Indo-Scythian rulers on their coins. With the right hand, some of them are forming the Karana mudra against evil spirits. In Gandhara, such friezes were used as decorations on the pedestals of Buddhist stupas. They are contemporary with other friezes representing people in purely Greek attire, hinting at an intermixing of Indo-Scythians (holding military power) and Indo-Greeks (confined, under Indo-Scythian rule, to civilian life).

Another relief is known where the same type of soldiers are playing musical instruments and dancing, activities which are widely represented elsewhere in Gandharan art: Indo-Scythians are typically shown as reveling devotees.

Indo-Scythians pushing along the Greek god Dyonisos with Ariadne.[38]

Hunting scene.

Hunting scene.

Hunting scene.

Stone palettes

Main article: Stone palette

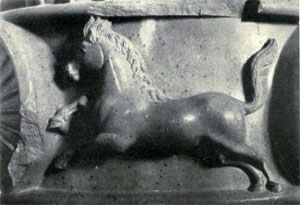

[x] File:ScythianStonePalette.jpg

Indo-Scythian stone palette, found in Sirkap, New-Delhi Museum. The lion with protruding tongue is highly reminiscent of those on the Mathura Lion Capital.

Numerous stone palettes found in Gandhara are considered as good representatives of Indo-Scythian art. These palettes combine Greek and Iranian influences, and are often realized in a simple, archaic style. Stone palettes have only been found in archaeological layers corresponding to Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian rule, and are essentially unknown the preceding Mauryan layers or the succeeding Kushan layers.[39]

Very often these palettes represent people in Greek dress in mythological scenes, a few in Parthian dress (head-bands over bushy hair, crossed-over jacket on a bare chest, jewelry, belt, baggy trousers), and even fewer in Indo-Scythian dress (Phrygian hat, tunic and comparatively straight trousers). A palette found in Sirkap and now in the New Delhi Museum shows a winged Indo-Scythian horseman riding winged deer, and being attacked by a lion.

The Indo-Scythians and Buddhism

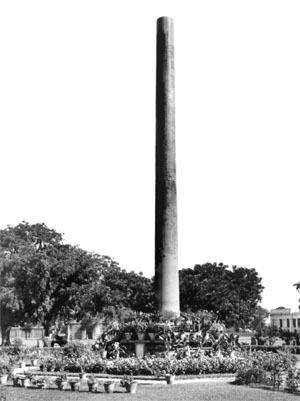

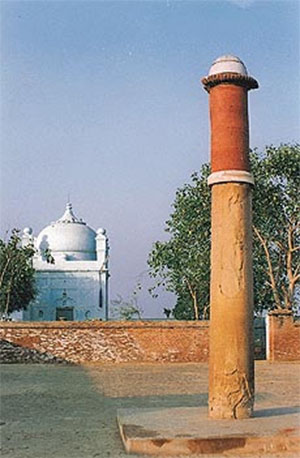

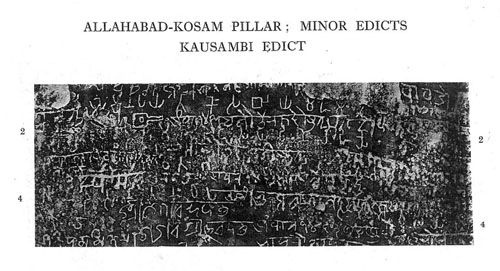

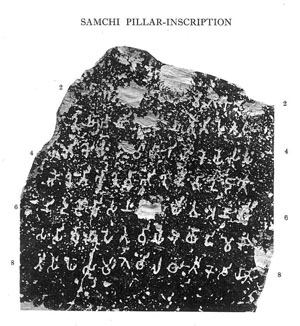

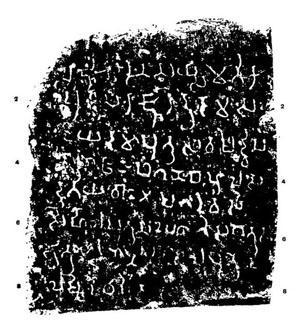

The Taxila copper plate records Buddhist dedications by Indo-Scythian rulers (British Museum).

The Indo-Scythians seem to have been followers of Buddhism, and many of their practices apparently continued those of the Indo-Greeks. They are known for their numerous Buddhist dedications, recorded through such epigraphic material as the Taxila copper plate inscription or the Mathura lion capital inscription.

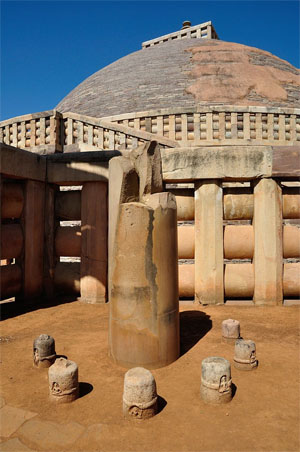

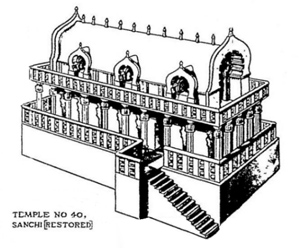

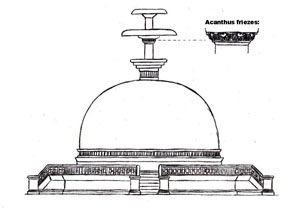

Butkara Stupa

Buddhist stupas during the late Indo-Greek/Indo-Scythian period were highly decorated structures with columns, flights of stairs, and decorative Acanthus leave friezes. Butkara stupa, Swat, 1st century BCE.[40]

Possible Scythian devotee couple (extreme left and right, often described as "Scytho-Parthian"[41]), around the Buddha, Brahma and Indra.

Excavation at the Butkara Stupa in Swat by an Italian archaeological team have yielded various Buddhist sculptures thought to belong to the Indo-Scythian period. In particular, an Indo-Corinthian capital representing a Buddhist devotee within foliage has been found which had a reliquary and a coins of Azes II buried at its base, securely dating the sculpture to around 20 BCE.[42] A contemporary pilaster with the image of a Buddhist devotee in Greek dress has also been found at the same spot, again suggesting a mingling of the two populations.[43] Various reliefs at the same location show Indo-Scythians with their characteristics tunics and pointed hoods within a Buddhist context, and side-by-side with reliefs of standing Buddhas.[44]

Gandharan sculptures

Other reliefs have been found, which show Indo-Scythian men with their characteristic pointed cap pushing a cart on which is reclining the Greek god Dyonisos with his consort Ariadne.

Mathura lion capital

The Mathura lion capital, which associates many of the Indo-Scythian rulers from Maues to Rajuvula, mentions a dedication of a relic of the Buddha in a stupa. It also bears centrally the Buddhist symbol of the triratana, and is also filled with mentions of the bhagavat Buddha Sakyamuni, and characteristically Buddhist phrases such as:

"sarvabudhana puya dhamasa puya saghasa puya"

"Revere all the Buddhas, revere the dharma, revere the sangha"

(Mathura lion capital, inscription O1/O2)

[x]PilarImage4.jpg

Indo-Corinthian capital from Butkara Stupa, dated to 20 BCE, during the reign of Azes II. Turin City Museum of Ancient Art.

[x]DancingIndoScythians.jpg

Dancing Indo-Scythians (top) and hunting scene (bottom). Buddhist relief from Swat, Gandhara.

[x]ButkaraDoorJamb.jpg

Butkara door jamb, with Indo-Scythians dancing and reveling. On the back side is a relief of a standing Buddha[45]

[x]IndoScythiansAndBuddha.jpg

Devotees of the Buddha in Indo-Scythian clothes (top), and erotical scene (bottom), Butkara stupa.

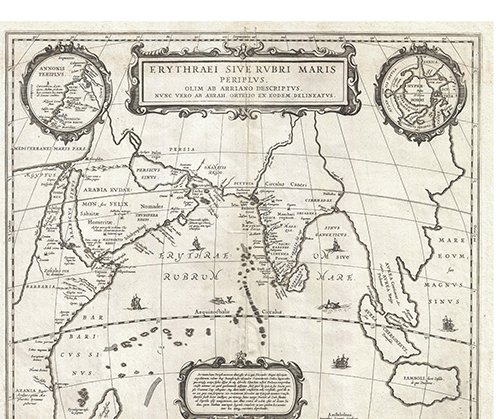

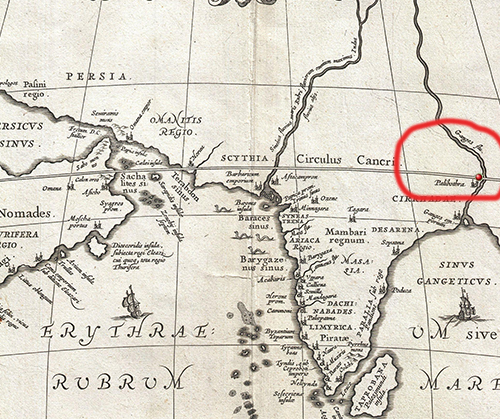

Indo-Scythians in Western sources

[x]File:TabulaPeutingerianaIndo-Scythia.jpg

"Scythia" appears around the mouth of the river Indus and along the western coast of India, in the Roman period Tabula Peutingeriana.

The presence of Scythian territory in northwestern India, and especially around the mouth of the Indus is mentioned extensively in Western maps and travel descriptions of the period. The Ptolemy world map, as well as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea mention prominently Scythia in the Indus area, as well as Roman Tabula Peutingeriana. The Periplus states that Minnagara was the capital of Scythia, and that Parthian king were fighting for it during the 1st century CE. It also distinguishes Scythia with Ariaca further east (centered in Gujarat and Malwa), over which ruled the Western Satrap king Nahapana.