The Maniktala secret society: An early Bengali terrorist group

by Peter Heehs

Sri Aurobindo Ashram Archives and Research Library

Pondicherry

Author’s Note: I am grateful to Dr Jacques Pouchepadass, Director of the French Institute of Pondicherry, for going through two drafts of this paper and offering many helpful suggestions.

Introduction

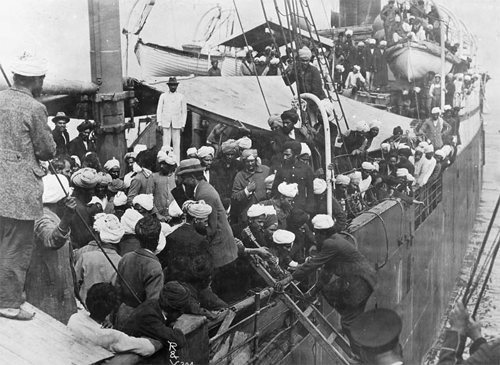

The subject of this study is the secret society (gupta samiti) that developed out of the Calcutta Anushilan Samiti around 1905 and engaged in terrorist acts under the direction of Barindrakumar (’Barin’) Ghose between 1906 and 1908. This society was closely connected with the Jugantar newspaper and that name was sometimes used to denominate its members.1 In later years the Government and former members as well referred to the group as the ’Jugantar Party’, which property speaking was the name of a loose grouping of revolutionaries that grew out of the remnants of Barin’s organisation after 1910.2 In fact between 1906 and 1908, the period of this study, the society in question had no particular name. In order to distinguish it from its descendant I will refer to it as the Maniktala secret society, after the Calcutta suburb where its headquarters was located during the most eventful phase of its brief life.

The Maniktala secret society was modern India’s first organised terrorist group with a clear political aim.3 It prefigured and influenced the development of similar societies that rose in Bengal and elsewhere after its extinction. In this study, after looking briefly at the group’s aim and ’ideology’, I will examine its structure, that is its theoretical and actual organisation, and its activities both in its preparatory and active stages. I will also point out similarities and contrasts between it and other terrorist groups in India and abroad. In concluding I will discuss the reasons for its inability to achieve its immediate aims, but show that its attempts were not altogether without effect.

Aim and Ideology

The Maniktala secret society aimed at the achievement of complete independence. The leaders of the Extremist party, one of whom, Aurobindo Ghose, was also one of the founders of the society, formulated this goal twenty-five years before it was taken up by the Indian National Congress and stated it with remarkable candour in their printed propaganda. Setting forth ’Our Political Ideal’ in the third issue of the Bengali weekly Jugantar on March 1906, Aurobindo wrote: ’independence [swadhinata] in our educational, commercial and political life has to be attained by any means possible.4 In subsequent issues other Jugantar writers laid stress on the fundamental need of independence. This was the primary thing, without which there could be no real social or economic progress.5 Aurobindo made the same point in his English newspaper Bande Mataram: ’Political freedom is the iife-breath of a nation. To attempt social reform, educational reform, industrial expansion, the moral improvement of the race without aiming first and foremost at political freedom is the height of ignorance and futility.’6 Bipin Chandra Pal had written earlier in the same journal: ’we desire to make it [India] autonomous and absolutely free from foreign control.7Aurobindo felt that Pal’s phrasing, unprecedented as it was, ’could have meant or even included the Moderate aim of colonial self-government’, and in his own writings he stressed that the independent government towards which his party aimed must be ’unhampered even in the least degree by foreign control’. 8

Such statements unquestionably influenced the members of the Maniktala society who, whatever their level of education, had a clear idea that the goal of their revolutionary efforts was to obtain political independence.9 Other ideology was of little use to them. Certainly they had no interest in European economic theory. One member of the society, Hem Chandra Das, went to Europe in 1907 because he wanted to learn about the organisation of secret societies and the manufacture of explosives.10 Believing that ’anarchist’ was synonymous with ’revolutionary’, he sought out the French anarchist ’Libertad’ (Joseph Albert, 1875-1908) and learned from him and his comrades something about anarchism, socialism communism, and so forth.11 Hem showed little interest in these competing theories and indeed stopped frequenting his anarchist acquaintances once he discovered what they believed in. Sister Nivedita, an intimate of several members of the Maniktala society, was a correspondent of Peter Kropotkin, but there is no evidence that the Russian anarchist’s ideas influenced society members.

It has sometimes been asserted that Aurobindo and others replaced legitimate politico-economic ideology with religious belief, and that their movement failed for this reason.12 I will examine the reasons for the movement’s failure before concluding. Here I will look briefly at the complex question of the presence of religion in the politics and action of the 1905-10 period. It certainly is true that writers in Bande Mataram, Jugantar and other Extremist organs made use of Hindu terminology and symbolism. What is more doubtful is the assertion, advanced by certain writers, that by so doing the Extremists prepared the way for the development of communalism.13 As is often the case when scholars take up popular controversies, some at least of these claims are based on a rather superficial reading of the sources. A passage from one of Aurobindo’s speeches-’What is Nationalism? Nationalism is a religion that has come from God’-is frequently held up as an example of pre-communalistic Hindu religiosity, Aurobindo’s statement being interpreted, roughly: national politics in India is part and parcel of (the Hindu) religion.14 A .careful reading of the text shows several deficiencies in this interpretation. First, by ’Nationalism’ Aurobindo meant primarily the Nationalist Party, which (as all specialists in the period know) was one of the names that he and Tilak applied to the party now generally known as the Extremists. He certainly was not referring to nationalism in general. Second, Aurobindo was not a Hindu properly speaking. For a few years he used this label for himself, but with the qualification that he did not mean ’the ignorant customary Hinduism of today’, but ’the purer fprm of Vedanta’.15 Finally and most importantly, Aurobindo was not using ’religion’ here in the sense of ’a set of beliefs, ritual practices, etc.’, but in the extended sense of ’a high and noble calling under the direction of a higher power’. The sentence following the quoted one, which often is replaced by ellipsis points by those who quote,’16 runs: ’Nationalism is a creed which you will have to live.’ This sentence, and the speech as a whole, make it clear that what Aurobindo meant was that ’Nationalism’ itself was a ’religion’, one made up, as he explained, of faith, selflessness and courage. While certainly himself a religious, or, as he would have preferred to say, a ’spiritual’ man, Aurobindo never asserted that politics ought to be infused with the spirit of any formal religion, Hindu or other.

It is true that Hindu-Muslim relations worsened during the Swadeshi agitation, but this does not seem to have been caused by a pronounced Hindu slant in Extremist propaganda. The writers of the two most influential Extremist pamphlets of the period, Sonar Bangla and Raja Ke?, both addressed themselves to Muslims as well as Hindus. Sonar Bangla proclaimed: ’This is the time for the Bengali to show the people of the world that [sic] he can do.... Brothers, Hindus, Mussalmans, gird up your loins for the honour of your mother. Since all must one day die, why fear?’ Raja Ke? accused the ruling power of destroying the country’s commerce and industry by unfair practices and ruining both cultivators and landowners by overtaxation. The people therefore had no true ’king’ and should rise against the foreign usurpers. The writer urged his readers to ’circulate from village to village that we Hindus and Mohammedans jointly worship the feet of the mother native country.’17 The emblem of Jugantar combined Hindu and Muslim symbols, and its editors made efforts to be non-sectarian. Writing about the ideal of the ’kingdom of righteousness’ (dharma rajya), which generally is associated with the Hindu tradition, Jugantar declared: ’Each man has his own dharma and it is by the cultivation of this dharma that he becomes fit for the path of emancipation. Therefore the kingdom of righteousness is as indispensible to the Muslim or Christian as it is to the Hindu.’ The first step for everyone was to establish ’a distinct independent [political] aggregate.’18 Here, as always, the ’one thing needful’ (as Aurobindo called it) was the attainment of political independence. If the Extremists and their activist followers had any ideology, this was it.19

The reasons for the falling out between Hindus and Muslims during the swadeshi period are too complex to be discussed here.20 As the two communities became polarised over such issues as partition and boycott, the ecumenism of Sonar Bangla and Raja Ke? was replaced by the sectarianism of the Lal Ishtahar (’Red Pamphlet’) and threatening statements in Jugantar such as the following: ’Favoured sons of independence, Musalmans, be warned!... The Hindus are certain to be independent. Will Musalmans then allow themselves to remain without that nectar?’ In 1907 relations between the two communities were poisoned by serious riots in Comilla and Jamalpur. Contemporary Hindus believed that the British government instigated or gave its support to Muslim rioters.21 Partly as a result of this, Hindus began lumping the Muslims and British together. In the aftermath of the riots at least one society barred Muslims from membership.22 This deprived the terrorist movement of a potential source of strength.

Activities-Period of Preparation

During the preparatory period of the Maniktala society, roughly between 1902 and 1907, its members were concerned chiefly with the collection of men, arms and money. Each of these requisites will be considered in turn.

Collection and Organisation of Men

Direct Recruitment

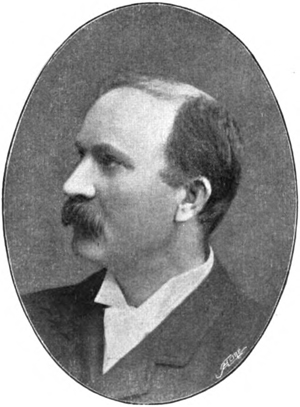

The Calcutta Anushilan Samiti, from which the Maniktala group developed, was founded in 1902 to promote physical, mental and moral culture among Calcutta students. Its organisers, P. Mitra and later Jatindranath Banerji and Aurobindo Ghose, regarded the promotion of healthy physical and mental activities as a means to cultivate pro-nationalist attitudes in young Bengalis. In addition they viewed Anushilan and similar samitis as training grounds for men who would take part in a future military uprising against the British. 23 When Jatin Banerji began to recruit men for the society in 1902 he used the legitimate activities of a branch of the Calcutta Anushilan as a cover for his revolutionary training. 24

Jatin Banerji’s method was to invite young men to learn physical skills such as lathi-play, drill, cycling and horseback riding at his North Calcutta akhara (gymnasium). In 1903 he was joined by Aurobindo’s brother Barindrakumar, who used to go to places in Calcutta frequented by students to try to win them over. Barin, Jatin and Bhupendranath Dutt also made tours of the districts for this purpose.25 In a statement given to the police after his arrest in 1908, Barin said:

After being there [Baroda, where his brother Aurobindo was posted] for a year I came back to Bengal with the idea of preaching the cause of independence as a Political Missionary. I muvrd about from District to District and started gymnasiums. There young men were brought together to learn physical exercises and study politics. 26

It should be noted that Barin, did not preach ’the cause of independence’ until he was sure the prospective recruit was interested. Before 1905 very few were. After a feud with Jatin in 1904 that resulted in the practical disappearance of the Calcutta society Barin went back to Baroda were he remained until the start of the Swadeshi movement (August 1905) made it seem worthwhile to try again.

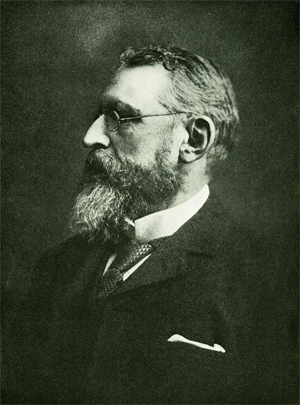

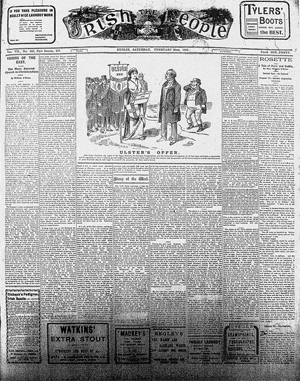

Printed Propaganda

The Swadeshi movement galvanised the students of Bengal but also provided them with an outlet for their new-found political enthusiasm in the form of organisations such as the National Volunteers, which enforced the boycott of British goods, and the Anti-Circular Society, which opposed certain official ’circulars’ directed against students. Those interested in revolutionary change had to divert the students’ enthusiasm from passive to active resistance. Such a general change of attitude could not be accomplished by word-of-mouth promotion, which between 1902 and 1905 had reached only a few hundred students. A printed organ was needed and in March 1906 Barin and others started Jugantar. This Bengali weekly was characterised by James Campbell Ker, author of the official history Political Trouble in India 1907-1917, as ’the first and most pernicious of the revolutionary papers of Calcutta’.27 It unquestionably was the most important single factor in the development of revolutionary thinking in Bengal between 1906 and 1908. Fifteen months after its founding its circulation was still only 200; but a year later, after four sedition prosecutions, it had reached the ’hitherto unknown’ figure of 50,000.28 Of the ten members of the Maniktala society who gave statements to the police after their arrest, eight spoke of the importance of Jugantar in their conversion. Only two said they were convinced by verbal arguments.29 Most if not all of the other three dozen men directly connected with the Maniktala society were influenced by what they read in Jugantar, as were many others who joined other societies. Birendranath Dutta Gupta, who assassinated the detective Shamsul Alam in January 1910, said in his confession: ’On reading the Jugantar I got a very strong wish to do brave and violent works.’30

Probably in 1907 a selection of articles from Jugantar was published under the title Mukti Kon Pathe? (Which Way Freedom?). This became one of the best known revolutionary publications in India, circulating widely in Bengal and reaching other provinces as well. (A Gujarati translation was issued before 1911.) As late as 1933 it was used for recruitment purposes in Bengal, years after the party that had issued it had disappeared.31 All the points discussed in the present study-the building up of public opinion through newspapers, the collection of money and arms, etc.--were discussed quite openly in this book.32 Another popular revolutionary publication issued by the Maniktala society was Bartaman Rananiti or ’The Modern Art of War’, which was essentially an adaptation in Bengali of an English military text.33 But the book contained some original material directed specifically towards Bengali readers. The last chapter took up the question, ’How can a weak and disarmed nation fight against armed and trained soldiers?’ The writer answered that nothing was impossible if the people were determined to attain liberty even at the cost of death. When conditions were right native troops would desert, the hill tribes would rise, young men would engage in irregular warfare and all this together with pressure from abroad would eventually wear the enemy down. 34

Internal Organisation of the Society

The men who responded to this propaganda and became members of the Maniktala society or others like it were, with few exceptions, young Bengali Hindus. Most of them were from the ’respectable’ (bhadralok) castes and most of them fairly well educated. The leaders, all well-read and intelligent, provided the society with a well-thought-out theoretical structure, which however may never have been put into practice. Certain documents discovered by the police during searches in Bengal around 1908 set forth a complex group hierarchy based on the Russian model.35 A diagram discovered at the headquarters of the Maniktala society outlined something that must have resembled the group’s actual structure more closely, though it too may have been more theoretical than practical. According to the diagram the primary division was between the leadership, consisting of Barin Ghose and Upendra Nath Banerjee, and the rank-and-file, consisting (at the time the document was drawn up) of fourteen members. Each member was assigned to one or more of three ’circles’, which dealt with (a) ’band work’, said to mean collection of funds (by solicitation or perhaps by dacoity); (b) ’exp., mech., and an.’, apparently ’explosives, mechanics and anarchy’, i.e., practical terrorist work; and (c) missionary, training and intelligence work. Each of the circles was under the supervision of one or more leaders, namely: (a) Barin Ghose, (b) Ullaskar Dutt and Upendranath Bannerjee, and (c) Barin and Upendranath.36

These divisions seem to correspond fairly closely to those actually reported by society members in their confessions and reminiscences. Barin and Upendranath were certainly the active leaders of the society, though they thought of themselves as subordinate to Aurobindo Ghose, who exercised some control over the society’s operations. Barin and Upendranath, with Aurobindo and others above them, constituted what might be called the society’s ’central command’. Such a command is said by Walter Laqueur to be a characteristic feature of all terrorist movements.37 The Maniktala society had a relatively weak central command due to the free-and- easy personality of its leaders. In contrast the rigid command structure of the Dacca Anushilan was a reflection of the personality of its leader Pulin Behari Das.38

In their reminiscences society members Upen Banerjee and Nolini Kanta Gupta speak of an actual functional division into two sections rather than three ’circles’. According to Nolini there was a ~military’ side and a ’civil’ side, the former concerned with terrorist actions, the latter with propaganda and recruitment. According to Upendranath the senior members busied themselves with ’works’ while the younger ones were occupied with ‘studies’.39 In both cases the first section corresponds to circles one and two of the diagram, the second to circle three.40 All the recruits did in fact spend much of their time in study. But it was of course not true (as the group’s lawyers attempted to convince the Courts) that the ’students’ knew nothing about ’works’. Bomb-making formed part of the general curriculum and even one of the youngest was asked to copy out the bomb-manual brought from Paris by Hem Chandra Das.41

Interconnection and Factionalism

The Maniktala society was loosely connected with a number of other samitis in Bengal such as the Calcutta Anushilan, of which it was an outgrowth, the Atmonnati Samiti, with whom it shared members and undertook joint actions, and more remotely the Dacca Anushilan and other East Bengal groups such as the Sadhana Samaj of Mymensingh. Members of different samitis were drawn together by a common dedication to ’the idea’ and a shared respect for leaders like P. Mitra and Aurobindo Ghose. But the forces tending to keep them apart were stronger than those drawing them together. Factionalism has always been a characteristic of terrorist societies.42 To be sure terrorist groups often deliberately divide themselves into small, manageable cells for strategic and protective purposes. There is some evidence that Indian groups were aware of foreign groups having this kind of structure.43 But the abundant evidence of quarrelling among Bengali groups (despite efforts by the leaders to keep them together) suggest that the actual reason for the fragmentation in Bengal was the inability of the groups to cooperate. Indeed the leaders seem to have contributed to rather than reduced the fragmentation. The general rule that active heads of terrorist groups tend to be authoritarian is borne out by the examples of Jatin Banerjee, Pulin Das and Barin Ghose. Revolutionary leaders of genius like Lenin or on a smaller scale Pulin Das can weld masses of men into a powerful union. More commonly however, as Laqueur has pointed out, strong leadership tends to produce rivalry and opposition and even small groups have built in centrifugal tendencies.44

The Maniktala society was itself the product of three acts of division. Jatin Banerji broke first with P. Mitra and then with Barin Ghose; Barin later broke with the Jugantar group led by Nikhileshwar Roy Maulik.45 Some memorialists have tried to smooth over these breaches, but it is clear from statements by the participants themselves that there was a good deal of bad blood involved. Barin Ghose alluded to this on two occasions in the 1930s:’ ’No one knows better than the terrorists themselves how mean personal jealousies and senseless feuds among leaders of small units are working towards disintegration in their ranks.’ ‘A cult of violence is always the mother of bitter jealousies and personal animosities.’46 Aurobindo Ghose spoke of the same tendencies to a young man desirous of taking part in revolutionary activities:

Young men come forward to join the movement being goaded by idealism and enthusiasm. But these elements do not last long. It becomes very difficult to observe and extract discipline. Small groups begin to form within the organization, rivalries grow -between groups and even between individuals. There is competition for leadership.... Sometimes they sink so low as to quarrel even for money.47

Similar statements were made by Upendranath Banerjee and others.48 Even the judge who tried the members of the society after their arrest remarked that the documents exhibited in the case gave evidence of ’much jealousy’.49 At the moment the police broke up the society a fissure had opened between Hem Das on the one side and Barin on the other that would probably have led to the formation of yet another splinter group.50

In the light of this pervasive factionalism we can examine claims that the Maniktala society had connections with similar groups all over India and indeed was part of a vast and unified revolutionary confederation. Terrorist supporter and organiser C.C. Dutt once spoke of a country-wide organisation with men like Aurobindo Ghose and Lala Lajpat Rai in charge of their respective provinces. 51 There is no evidence at all to support Dutt’s story. Barin Ghose made inflated claims of the extent of the revolutionary organisation when he went on recruitment and fund-raising drives. Such misrepresentation was also practised by Jatin Banerji, Devabrata Bose, Hem Chandra Das and other members of the Maniktala society. 52 It was in fact common practice among leaders of Bengali terrorist groups and has been noticed in other groups in Europe and elsewhere.53 Barin seems to have picked up the habit of exaggeration from others and may at first have actually believed what he was saying. While in Maharashtra in 1902-3 he had been told that every province except Bengal was ready for the uprising. It was only when he returned to Western India at the time of the Surat Conference (1907) and reported that Bengal was now ready that he learned that no country-wide organisation existed.54

Certain members of the Anglo-Indian community, with memories of 1857 to haunt them, also made more of the ’revolutionary conspiracy’ than it was worth. After the Maniktala arrests the Europeans of Calcutta became ’hysterical’ and even the Viceroy Lord Minto spoke of the possibility of organised terrorist outrages ’throughout India’.55 Sir Harold Stuart, former head of the Criminal Investigation Department, came closer to the truth when he wrote after the arrests: ’My experience is that this society had no branches outside Calcutta or in other provinces, but there may be similar societies elsewhere, having a loose sort of connection with the Calcutta society.56 The first part of Stuart’s statement was not strictly correct, since the Maniktala society did have at least one ’branch’ in Midnapore and was closely allied to societies in Nadia, Chandernagore and elsewhere. But the phrase ’a loose sort of connection’ describes well the relationship existing between the Maniktala society and others. Its connection with other Bengal groups has been indicated above. It also had ties with groups in Baroda, Bombay and the Central Provinces and was in contact with like-minded individuals in Madras and Punjab. The Baroda link was due to Aurobindo Ghose, who had served in that Native State before coming to Bengal. Correspondence with and documents mentioning Madhavrao Jadhav and K.G. Deshpande, Baroda men who were interested in revolutionary action, were found during the Maniktala searches.57 Sisir Ghose, one of the Maniktala revolutionaries, visited Jadhav, an officer in the Baroda army, to speak to him about military training for Bengalis.58 Balkrishna Hari Kane, a Maharashtrian arrested in Calcutta with the Maniktala men, had been sent there for training by G.S. Khaparde, an associate of Tilak’s in the Central Provinces.59 Hem Das met a number of revolutionaries from western India during his stay in London and Paris. P.M. Bapat, who studied chemistry and politics with Hem, was a Maratha having ties with the Mitra Mela group of Nasik.60 On his return to India Hem Das met several men in Bombay whose names he had been given by friends in Paris and London.61 Aurobindo Ghose was in correspondence with Chidambaram Pillai during 1908 and later entered into contact with other Madras revolutionary leaders.62 After leaving Bengal Jatin Banerji transmitted the ’idea’ to Kissan Singh, the father of Bhagat Singh. Later stronger links between Bengal and Punjab were forged by Sarala Devi Chaudhurani and Rash Behari Bose.63 But for all this there was never a national terrorist organisation in India. Factionalism was always stronger than association and even in Bengal (as Barin Ghose perhaps too graphically put it) the terrorists were ’honeycombed into small bands each ready to cut the throats of the other.64

Collection of Arms

The Arms Act of 1878 made it illegal for natives of India (certain dignitaries excepted) to possess swords, firearms and most other weapons. By incorporating these forbidden items in their ceremonies of initiation the Bengali secret societies ritualised law-breaking. But the importance of firearms to the society was more than symbolic. Rifles and guns were needed for the future uprising, handguns essential for carrying out terrorist acts. To obtain them was one of the society’s chief concerns during the preparatory period; to transport them became a practical rite of passage, allowing recruits to demonstrate their manliness and mettle.65 Two principal methods were used to obtain arms: theft and misuse of legal channels. Two of the revolvers carried by members of the Maniktala group had been snatched from Calcutta policemen.66 The revolvers that killed Narendranath Goswami and other handguns used by the Maniktala society came from French Chandernagore, where no arms act was in force. Chandernagore soon became the principal centre of arms traffic in Bengal if not in India.67

Persons exempted from the operations of the Arms Act included large landowners, the nobility, and government servants. Terrorists made use of contacts with persons in each of these classes to obtain weapons. Satyen Bose’s brother Jnan Bose possessed a licence for the rifle found in his house. Members of another group purchased seven guns and three revolvers in the name of a Rani of Putia.68 Indra Nandi made good use of the exemption of his father, a member of the Indian Medical Services.69 By means of such haphazard methods the Maniktala society managed to build up an ’arsenal’ consisting of three sporting rifles, two double-barrelled shotguns, and nine revolvers over the course of three years.70

Even the boldest band of revolutionaries could do little to overthrow the government with fourteen miscellaneous firearms. Aware of this, at an early stage Barin Ghose became interested in explosives. Bombs are more powerful and also more stimulating than revolvers. The publicity generated by terrorist acts has always been considered as important as the act itself.71 In the first years of the twentieth century nothing could grab more headlines than a successful bombing. After the invention of nitroglycerine and gelignite in the 1860s and 1870s the bomb became the weapon of choice of the European terrorist and the symbol of the ’anarchist’ movement.72 Barin began bomb-making experiments shortly after the refounding of the society in the latter part of 1905. By mid-1906 he was going around East Bengal demonstrating a crude bomb to prospective donors.73 Publicists wrote rashly about bombs in nationalist organs and more than one young man resolved to acquire a sufficient knowledge of chemistry to produce them. One of the first to succeed was Ullaskar Dutt. His first dynamite mine was a dud; but the one he made to derail the train of the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal near Kharagpur almost did the job. The dynamite in this device was supplied by Manoranjan Guha Thakurta, an Extremist politician and terrorist sympathiser who owned a mica mine.74 Society members also purchased acids and other bomb-ingredients openly and in bulk and began ’the actual manufacture of high explosives on a large scale’. Eight finished bombs were discovered when the headquarters of the society was raided in May 1908.75

The society’s main explosives expert received his training in Europe.76 Hem Chandra Das returned from Paris early in 1908 with an excellent knowledge of chemistry and a 70-page manual on bombs and demolition given to him by his teacher. This manual was, a British expert later testified, ’The best work on explosives I have ever seen.’ Written in simple nontechnical language, it permitted a layman to ’use the contents of a Chemist’s shop for the manufacture of explosives’. Its general purpose was described in its opening sentence: ’The aim of the present work is to place in the hands of a revolutionary people such a powerful weapon as explosive matter is.77 The first fruit of Hem’s studies was a book-bomb delivered to an unpopular magistrate in January 1908. This was quite an up-to-date device: the world’s first parcel-bomb had been tried out in Berlin only thirteen years earlier.78 Hem’s bomb was well-made and failed in its purpose only because the magistrate neglected to open it.79 Later working together with Ullaskar Hem produced a picric-acid bomb used in Chandernagore and a gelignite bomb used in Mazaffarpur in April. The first did not go off (Ullaskar blamed the inferior picric acid); the second killed two women and led to the arrest of most of the members of the society.80

Collection of Funds

The German anarchist Johann Most ’maintained that in money-even more than in dynamite-the key was to be found.’81 Terrorist movements are expensive to run. Arms and explosives are costly and the printing of propaganda a constant drain; but probably the greatest expense is the feeding and lodging of members. The ’General Principles’ manuscript lists three sources of income: (a) profit-making enterprises; (b) contributions from men of wealth; and (c) robbery, euphemistically referred to as ’imposing taxes on rich people with the aid of the terroristic department’.82 The Bengal Extremist-terrorist party made use of all three of these methods. Early on they made an attempt at self-sufficiency by setting up the Chhatra Bhandar or student’s store. This enterprise was intended to earn money legitimately as well as to launder funds acquired illegally. It was-never a great success. Bande Mataram, Jugantar and other newspapers brought in a certain amount of money, but owing to bad management almost all of this had to be used to keep the papers afloat. As the papers flirted ever more dangerously with sedition they began to attract undue attention from the police, causing Barin Ghose to sever his connection with them. As the chief fund-raiser of the terrorist party he came to depend on donations from ’people of great wealth’.83 These included Subodh and Nirode Mullick, heirs of an established shipbuilding business; Rajendranath Mukherjee, son of the zamindar of Uttarpara; Surendranath Tagore, a scion of Bengal’s most prominent zamindari family; mine owner Manoranjan Guha Thakurta; and government servants C.C. Dutt and Abinash Chakravarty.84 Professional men such as C.R. Das and P. Mitra, both lawyers, and Aurobindo Ghose, a professor before his retirement, also contributed money when they could.85 Barin managed to get enough from such men to keep the society going. But the donations were not unconditional. Barin latter claimed that he was forced to undertake assassinations by contributors who wanted spectacular results. Some ’donations’ were earmarked for the killing of specified officials. 86

Even more than the turn to assassination, the turn to dacoity was prompted by the need for money. As early as 1906 Narendra Nath Goswami was told: ’Money would be got by looting which was to be used to buy arms and ammunition.’ C.C. Dutt referred to this as the ’Mahratta’ method, an allusion to the plundering raids of the eighteenth-century Maratha freebooters.87 This gave a romantic aura to what well-bred bhadralok boys might otherwise have considered immoral behaviour. Another way to justify robbery was to refer to it as ’levying taxes’ (as in the document cited above) or ’collecting loans’ that would be repaid when independence had been achieved. One victim of a Calcutta dacoity received an ’official’ letter (complete with seal) from the ’Finance Secretary to the Bengal Branch of the Independent Kingdom of United India’ which began:

’Six honorary officers of our Calcutta Finance Department have taken a loan of Rs 9,891-1-5 from you and have deposited the amount in the office noted above on your account to fulfil our great aim. The sum has been entered in our cash book on your name at 5 per cent per annum.’ When the ’great aim’ had been attained ’the whole amount with interest’ would be repaid. The victim also was politely warned that if he cooperated with the police, the Finance Department would ’not leave anyone in your family to enjoy your enormous wealth’. It would be better if ’the rich men of the country’ would ’subscribe monthly, quarterly and half-yearly amounts’ to the Finance Secretariat.88 The terrorists no doubt enjoyed the joke; the victim presumably took the threat seriously.

Activities-Period of Action

It will be apparent from the above that the Maniktala terrorists undertook two types of operations or ’actions’: assassinations and dacoities. Both were continued by the group’s successors in Bengal. They in fact are the most frequently attempted operations by terrorist groups everywhere.89 The assassination of representatives of the adversary government has been the classic terrorist tactic since the time of the Assassins.90 It appealed to the Maniktala group for the usual reasons: the political effect of the blow, the publicity it would generate, and simple revenge. There was also, as mentioned above, a financial incentive.

Robbery is a more direct means of acquiring funds and it has been engaged in by many terrorist groups. Russian terrorists began to rob banks in 1879; in 1906 there were 362 ’expropriations’ of this sort in Russia.91 A Bengali document on Russian revolutionary methods found along with ’General Principles’ declares: ’The major portion of the money [for the Russian revolutionary parties] is obtained by dacoity and by an imposition of a cess on zamindars and (other) rich people. 92

The Bengali press, including even organs published by the Extremists, expressed horror over attempted and successful assassinations, but demonstrations of sympathy for assassins like Khudiram Bose and Kanailal Dutt show that the Bengali public were not opposed in principle to the murder of officials. The public attitude towards dacoities was of course different, since many of the victims were ordinary Bengalis. Citing an account of a 1907 train-station robbery, in which the station staff attempted to subdue the dacoits, Gordon comments, ’it seemed to them that dacoits were dacoits and robbery was robbery’.93 So it seemed to the Bengali villagers who cooperated with the police during the 1915 dacoity in which Sushil Sen was killed and the Oriya villagers who cooperated with the police in 1916 when they were hunting down Jatin Mukherjee.94 The villagers, even if supporters of the terrorists’ ’great aim’, may be said to have been justified in so far as the line between political dacoity and ordinary theft was not clearly drawn. The Government’s claim that the terrorist movement gave birth to a ’bhadralok loafer criminal class and an anarchical condition of things in which, although the revolutionary idea existed, there was undoubtedly a very big element of ordinary crime’ is supported by statements of Hem Chandra Das and Barin Ghose.95 Moreover, as Gordon has pointed out, the violent acts committed by Bengali terrorists (particularly in the period after 1910) ’were often only vaguely related to the goals of India’s independence’. Gordon made reference to a suggestion by Nirad Chaudhuri that the revolutionary murders and dacoities grew out of a tradition among well-to-do Bengalis to make use of hooligans (goondas) or even private armies to carry out murders for revenge.96 The police believed that Rajendranath Mukherjee, a zamindar’s son who was an important terrorist supporter, instigated a murder of this sort.97 One could find a parallel to this nexus between influential men and criminals in the so-called ’criminalization’ of political parties in post-independence India.

The Maniktala terrorists seem to have been relatively humane. Both Hem Chandra Das and Nolini Kanta Gupta felt relieved when dacoities they had been assigned to were called off.98 Later however, as dacoities became more common and more lucrative, Bengali dacoits became more ruthless. Up to the Muzaffarpur incident no innocent person was killed during a terrorist act. But starting from June 1908, when four persons were killed and one wounded during a dacoity that Petted Rs 26,837, civilian casualties became frequent.99

A remarkable feature of the policy of assassination in Bengal was the lack of success in killing European officials as compared to the high success rate in killing Bengali policemen, informers, etc. Between the shooting of the missionary Hickenbotham in March 1908 and the assassination of police inspector Shamsul Alam in January 1910 Bengali terrorists tried to kill four Europeans and failed each time. (At Muzaffarpur they succeeded in killing two innocent European women.) During the same period they carried out six successful assassinations of Bengalis with no failures. Western Indian terrorists chalked up a better record during these months: three attempts against Europeans, two of them successful, no known attempts against Indian. 100