by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/30/21

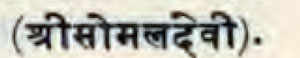

The Greek writers relate that the father of Sandrocottus was a man of low origin, being the son of a barber, whom the queen had married after putting her husband the king to death. He is called by Diodorus Siculus (16.93, 94) Xandrames, and by Q. Curtius (9.2) Aggrammes, the latter name being probably only a corruption of the former. This king sent his son Sandrocottus to Alexander the Great, who was then at the Hyphasis, and he is reported to have said that Alexander might easily have conquered the eastern parts of India, since the king was hated on account of his wickedness and the meanness of his birth. Justin likewise relates, that Sandrocottus saw Alexander, and that having offended him, he was ordered to be put to death, and escaped only by flight. Justin says nothing about his being the king's son, but simply relates that he was of obscure origin, and that after he escaped from Alexander he became the leader of a band of robbers, and finally obtained the supreme power...The name of Sandrocottus is written both by Plutarch and Appian Androcottus without the sibilant, and Athenaeus gives us the form Sandrocuptus (Σανδρόκυπτθς), which bears a much greater resemblance to the Hindu name than the common orthography. (Plut. Alex. 62 ; Justin, 15.4 ; Appian, Syr. 55 ; Strab. xv. pp. 702, 709, 724 ; Athen. 1.18e.; Arrian, Arr. Anab. 5.6.2; Plin. H. N. 6.17.)

-- Sandrocottus, by William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology

Recounting the scenario after the Hyphasis mutiny (Arr. 5.25, Diod. 17.93-5, Curt. 9.2.1-3.19), Badian writes with an air of definiteness:For the moment, he tried to use the weapon that had succeeded before. He withdrew to his tent, for three days. But this time it did not help. The men were determined, and as Coenus had made clear, they had the officers’ support. Alexander could not divide them. All that remained was to save face.

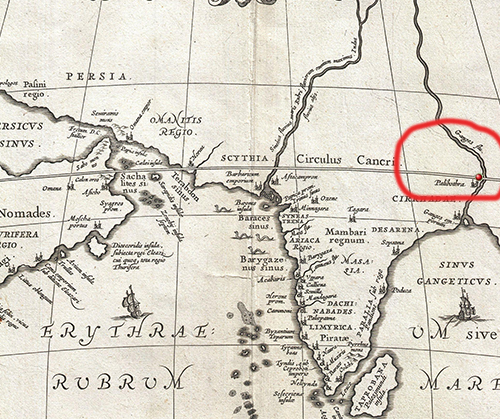

Badian not only finds Alexander in an awkward position, but also casually notes his subsequent declaration that he would go on nonetheless and his ordering of sacrifices for crossing the river. Alexander’s vow to fight against the Prasii in the face of stiff opposition from both the soldiers and officers does appear somewhat comical but here lies a trap—where was their capital Palibothra? Could it really have been at Patna, so far removed from the northwest—the centre of early India?...

Through the mist of vague reports and geographical misconceptions, it is difficult to probe into the Hyphasis revolt, which came as a serious jolt to Alexander. After this, even though there were safer routes, Alexander chose to return to Iran through the desert of Gedrosia, suffering heavy losses in soldiers and civilians from lack of water, food and the extreme heat. That the motive behind this voyage has appeared so perplexing is due to two crucial lapses—the false location of Palibothra, capital of the Prasii, and the concomitant failure to recognise the mysterious Moeris of Pattala who played a determinant role....

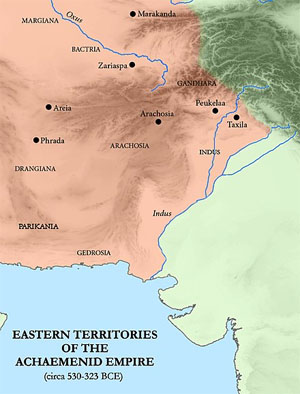

Territory of Gedrosia, among the eastern territories of the Achaemenid Empire.

The reports of Alexander’s historians clearly indicate that southeast Iran was within Greater India in the fourth century BC. As Prasii was in the Gedrosia area, the question arises—did the army refuse to fight the Prasii or only to march eastwards?... if the reluctance was to confront the Prasii, it appears sensible due to their formidable strength. As Moeris had fought beside Porus, the Prasiian army cannot have been left intact, though it could still have been a fighting force. It is probable that Moeris and his agents fomented discord among Alexander’s officers and soldiers... From this point onwards, if not earlier, Eumenes, Perdikkas and Seleucus may have been in touch with Moeris.

Only Justin (Just. xii, 8) reports that Alexander had defeated the Prasii. Palibothra, the Prasiian capital was famous for peacocks....

Curiously, Arrian writes that Alexander was so charmed by the beauty of peacocks that he decreed the severest penalties against anyone killing them (Arrian, Indica, xv.218). The picture of Alexander amidst peacocks appears puzzling: where did he come across the majestic bird? Does this fascination lead us to Palibothra? The height of absurdity is reached when we are told that eighteen months after the battle with Porus, Alexander suddenly remembered his ‘victory over the Indians’ in the wilderness of Carmania and set upon to celebrate it with fabulous mirth and abandon. Surprisingly it did not jar with the common sense of anyone why this was not celebrated in India. The ‘victory over the Indians’ in southeast Iran can lead to only one judicious conclusion—this was India in the fourth century BC. Moreover, if Alexander had indeed defeated the Indians, who could have been their leader but Moeris or Maurya? This clearly indicates that Alexander had indeed conquered the Prasii in Gedrosia.

Bosworth writes that the name of the place where the victory was celebrated was Kahnuj...As the winter deepened, Alexander approached the Carmanian capital, which Diodorus (xvii.106.4) names Salmus. It was, according to Nearchus (Arr. Ind. 33.7), five days' journey from the coast. The site remains a mystery, but it was probably at the western side of the valley of the Halil Rud, in the general vicinity of the modern town of Khanu. The army was in an area of relative plenty but close enough to the coast to receive news of the progress of Nearchus' fleet. There Alexander sacrificed to commemorate his Indian victory and the emergence from the Gedrosian desert, and he held a musical and athletic festival, a drunken and festive affair, notable for the general acclaim achieved by Alexander's favourite Bagoas when he entered the winning chorus.

-- A. B. Bosworth, Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great (Cambridge 1988), p. 150

Kahnuj (Persian: كهنوج, also Romanized as Kahnūj) is a city and capital of Kahnuj County, Kerman Province, Iran.

Patali (Persian: پاتلي, also Romanized as Pātalī; also known as Kheyrābād-e Pātelī) is a village in Jahadabad Rural District, in the Central District of Anbarabad County, Kerman Province, Iran.

It is therefore clear that Alexander did not run away from the Prasii, as Badian imagines, but had in fact pursued Moeris, their leader, through Gedrosia. The palace at Kahnuj where Alexander rejoiced must have been the fabled one which, according to Aelian, excelled those at Susa and Ekbatana (Aelian, xiii.18).

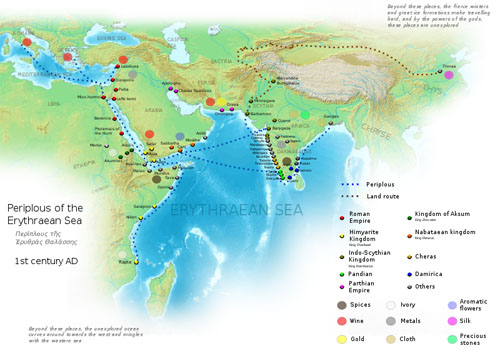

Nearchus certainly had other tasks than scientific fact-finding; the army was ordered to keep close to the shore and the navy moved in tandem. This orchestration and the large number of troops and horses on ships (quite unnecessary for a scientific mission) show that the navy was not only carrying provisions for the army which was engaged in a grim and protracted battle with a mighty adversary, but that the troops on the ships were also ready to support the army if needed. This is why the navy waited for twenty-four days near Karachi. The names Pataliputra and Pattala and Moeris and Maurya leave little to imagination.

Yet Badian fails to recognise that Moeris was Chandragupta Maurya of Prasii... Badian has no idea that the food crisis was due to the collusion of Alexander’s officers with Moeris. As a general, Alexander can hardly be blamed for imposing a levy in order to arrange for the supplies for his army; this is the reason why the people of Pattala had fled. In his unseemly haste to cast Alexander in a stereotype, Badian overturns the whole episode and goes on to compare him with Chengiz Khan.

-- An Altar of Alexander Now Standing at Delhi [EXPANDED VERSION], by Ranajit Pal

The first kings of the Dynasty of the Barhadrathas being omitted in the table, are given here from the Harivansa. The famous Uparichara was the sixth in lineal descent from Curu; and his son wasVrihadratha

Cushagra

Vrishabha

Pushpavan

Satyasahita

Urja

Sambhava

Jara-Sandha.

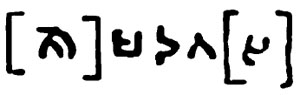

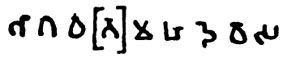

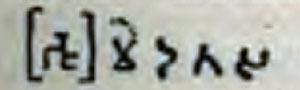

Jara-Sandha, literally old Sandha or Sandhas, was the lord paramount of India or Maha Raja, and in the spoken dialects Ma-Raj. This word was pronounced Morieis by the Greeks; for Hesychius says, that Morieis signifies king in India, and in another place, that Mai in the language of that country, signified great. Nonnus, in his Dionysiacs, calls the lord paramount of India, Morrheus, and says that his name was Sandes, with the title of Hercules. Old Sandha is considered as a hero to this day in India, and pilgrimages, I am told, are yearly performed to the place of his abode, to the cast of Gaya, in south Bahar, It is called Raja-Griha, or the royal mansion, in the low hills of Raja-giri, or the royal mountains; though their name I suspect to be derived from Raja-Griha The Dionysiacs of Nonnus are really the history of the Maha Bharata, or great war, as we shall see hereafter.

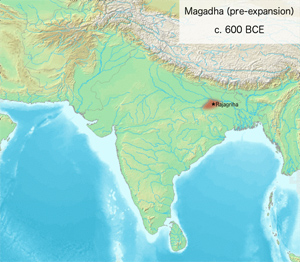

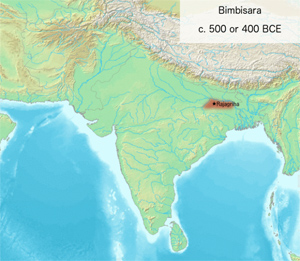

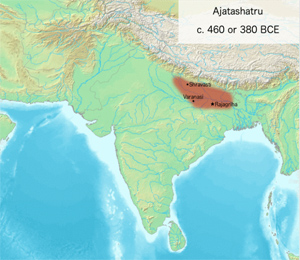

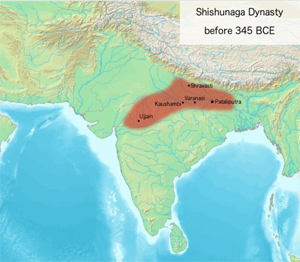

-- Essay III. Of the Kings of Magadha; their Chronology, by Captain Wilford, Asiatic Researches, Volume 9, 1809.

Shashigupta

Nationality: Paropamisadaen

Other names: Sisikottos; Sisocostus. Possibly Chandagupta.

Years active: 4th century BCE

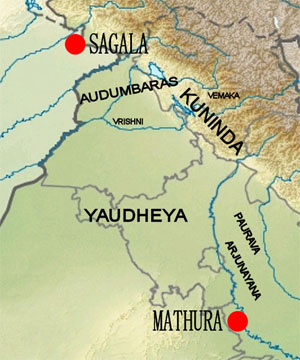

Shashigupta IAST: Śaśigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] was a ruler of Paropamisadae (modern north-west Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan), between the Hindu Kush mountains and Indus Valley during the 4th century BCE. The name Shashigupta is a reconstruction of a hypothetical Indo-Aryan name, based on a figure named in ancient Greek and Roman sources as Sisikottos (Arrian),[1] and Sisocostus (Curtius).

The root shashi is equivalent to chandra ("moon") in Indian languages. Consequently, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] is often linked to various figures known as Chandragupta in ancient Indian sources. Both names mean "moon-protected". However, there is no consensus amongst modern scholars as to which of the historical Chadraguptas, if any, may be identified with Shashigupta.

Identification with figures in Indian sources

Sisikottos/Sisocostus appears twice in Arrian's Anabasis and once in Historiae Alexendri Magni by Curtius. Many scholars suggest that Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] was a ruler of some frontier hill state south of Hindukush,[2] it is however, more appropriate to call him a military adventurer or a corporation leader coming from the warlike background of the fierce Kshatriya clan of the Ashvakas from Massaga or Aornos (Pir-Sir) or some other adjacent territory of the Ashvakas. No ancient evidence is available which attests Shashigupta's royal background prior to his appointment by Alexander as ruler of the Ashvakas of the Aornos country.

There are at least four schools of thought regarding any connection to one of the Chandraguptas. Some scholars identify him with Chandragupta Maurya, while others say that Chandragupta Maurya was a separate figure with origins in Eastern India and a third school sees Shashigupta and Chandragupta as separate Paropamisadaen figures, both of whom had ties to separate branches of the Ashvakas.[3][4][5]

Early life

Nothing is known about early life of Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus]. He was presumably a military adventurer, a leader of corporation of professional soldiers (band of mercenary soldiers) whose main goals were economic and military pursuits.[citation needed]

In all probability, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] was a professional soldier and led a corporation of mercenary soldier to help Persians especially Bessus, the Iranian Satrap of Bactria but once his case was lost, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus], along with band of warriors (obviously as mercenary soldiers), threw his lot with the invaders and thereafter, rendered a great help to Alexander during latter's campaigns of Sogdiana and later also of the Kunar and Swat valleys.[citation needed]

As the Satrap of the eastern Ashvakas

In May 327 BCE, when Alexander the Great invaded the republican territories of the Alishang/Kunar, Massaga and Aornos on the west of Indus, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] had rendered great service to the Macedonian invader in reducing several Kshatriya chiefs of the Ashvakas of the Alishang/Kunar and Swat valleys. He appears to have done this in an understanding with Alexander that after the reduction of this territory, he would be made the lord of the country. And Arrian definitively confirms that after the reduction of the fort of Aornos in Swat where the Ashvakas had put up a terrible resistance, Alexander entrusted the command of this extremely strategic fort of Aornos to Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] and made him the Satrap of the surrounding country of the eastern Ashvakas.[6]

Shashigupta vs Meroes, the friend of Porus

Porus himself, mounted on a tall elephant, not only directed the movements of his forces but fought on to the very end of the contest; he then received a wound on his right shoulder, the only unprotected part of his body, all the rest of his person being rendered shot-proof by a coat of mail remarkable for its strength and closeness of fit; he now turned his elephant and began to retire. Alexander who had observed and admired his valour in the field was anxious to save his life and sent Taxiles after him on horseback to summon him to surrender; but the sight of this old enemy and traitor roused the indignation of the Paurava, who gave him no hearing and would have killed him, had not Taxiles instantly put his horse to the gallop and got beyond the reach of Porus’. Even this Alexander did not resent; he sent other messengers till at last Meroes (Maurya ?), an old friend of Porus, persuaded him to hear the message of Alexander.

-- Chapter II: Alexander's Campaigns in India, Excerpt from "Age of the Nandas and Mauryas", by K.A. Nilakanta Sastri

Towards the end of battle of Hydaspes (Jhelum), Arrian mentions a certain Meroes and attests him to be an Indian and an old friend of Porus (or Poros). Arrian further attests that he was finally chosen by Alexander to bring the fleeing Porus back for concluding peace treaty with Macedonian invader.[7] It is notable that at the time of Porus's war with Alexander, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus], the satrap of the eastern Ashvakas had very cordial relations with Porus. In fact, he was on good terms both with Porus as well as Alexander and was finally chosen by Alexander to effect peace negotiations between him (Alexander) and Porus when Taxiles i.e. the ruler of Taxila had failed in this endeavour. It is more than likely, as several scholars have speculated, that Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] may have alternatively been known also as Meroes (equivalent to the Sanskrit Maurya) after his native-land Meros (Mor or Mer in Prakrit, perhaps Mt Meru of Sanskrit texts).[8][9] Another possibility is that name Meroes (Maurya?) may have been derived from "Mer" (hill or mountain) or "Mera" (hillman) on account of the fact that Sisicottos or Shashigupta was obviously a hilllman or mountaineer.[citation needed]

It is said that India, being of enormous size when taken as a whole, is peopled by races both numerous and diverse, of which not even one was originally of foreign descent, but all were evidently indigenous; and moreover that India neither received a colony from abroad, nor sent out a colony to any other nation. The legends further inform us that in primitive times the inhabitants subsisted on such fruits as the earth yielded spontaneously, and were clothed with the skins of the beasts found in the country, as was the case with the Greeks; and that, in like manner us with them, the arts and other appliances which improve human life were gradually invented, Necessity herself teaching them to an animal at once docile and furnished not only with hands ready to second all his efforts, but also with reason and a keen intelligence.

The men of greatest learning among the Indians tell certain legends, of which it may be proper to give a brief summary. They relate that in the most primitive times, when the people of the country were still living in villages, Dionusos made his appearance coming from the regions lying to the west, and at the head of a considerable army. He overran the whole of India, as there was no great city capable of resisting his arms. The heat, however, having become excessive, and the soldiers of Dionusos being afflicted with a pestilence, the leader, who was remarkable for his sagacity, carried his troops away from the plains up to the hills. There the army, recruited by the cool breezes and the waters that flowed fresh from the fountains, recovered from sickness. The place among the mountains where Dionusos restored his troops to health was called Meros; from which circumstance, no doubt, the Greeks have transmitted to posterity the legend concerning the god, that Dionusos was bred in his father's thigh.

Having after this turned his attention to the artificial propagation of useful plants, he communicated the secret to the Indians, and taught them the way to make wine, as well as other arts conducive to human well-being. He was, besides, the founder of large cities, which he formed by removing the villages to convenient sites, while he also showed the people how to worship the deity, and introduced laws and courts of justice. Having thus achieved altogether many great and noble works, he was regarded as a deity and gained immortal honours. It is related also of him that he led about with his army a great host of women, and employed, in marshalling his troops for battle, drums and cymbals, as the trumpet had not in his days been invented; and that after reigning over the whole of India for two and fifty years he died of old age, while his sons, succeeding to the government, transmitted the sceptre in unbroken succession to their posterity. At last, after many generations had come and gone, the sovereignty, it is said, was dissolved, and democratic governments were set up in the cities.

Such, then, are the traditions regarding Dionusos and his descendants current among the Indians who inhabit the hill-country [Librarian's Comment: Nysa, between the Cophen/Kabul and Indus rivers]. They further assert that Herakles also was born among them. They assign to him, like the Greeks, the club and the lion's skin. He far surpassed other men in personal strength, and prowess, and cleared sea and land of evil beasts. Marrying many wives he begot many sons, but one daughter only. The sons having reached man's estate, he divided all India into equal portions for his children, whom he made kings in different parts of his dominions. He provided similarly for his only daughter, whom he reared up and made a queen. He was the founder, also, of no small number of cities, the most renowned and greatest of which he called Palibothra. He built therein many sumptuous palaces, and settled within its walls a numerous population. The city he fortified with trenches of notable dimensions, which were filled with water introduced from the river. Herakles, accordingly, after his removal from among men, obtained immortal honour; and his descendants, having reigned for many generations and signalized themselves by great achievements, neither made any expedition beyond the confines of India, nor sent out any colony abroad. At last, however, after many years had gone, most of the cities adopted the democratic form of government, though some retained the kingly until the invasion of the country by Alexander.

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle

After the assassination of Nicanor

A few months later when Alexander was still in Punjab and was engaged in war with the Glausais of Ravi/Chenab, the Ashvakas had assassinated Nicanor, the Greek governor of lower Kabul valley and also issued a threat to kill Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] if he continued to cooperate with the invaders. While Phillipos was appointed to Nicanor's place, no further reference to Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] by this name exists in classical sources. It appears likely that as a shrewd politician & statesman cum military general, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] had sensed the pulse of time and therefore, after deserting Alexander’ camp, he had thrown his lot with the emerging powerful group of insurgents. Thence afterward, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] seems to appear under an alternative name----Moeres or Moeris of the classical chroniclers. It is notable that Moeres, Moeris, Meris and Meroes are all equivalent terms.[10] Arrian writes Meroes [11] while Curtius spells it as Moeres or Moeris.[12] Chieftain Moeris of lower Indus delta (Patala) referenced by Curtius seems precisely to be the same person as Meroes of north-west, attested to be old friend of Porus by Arrian.[11] Alexander was apparently annoyed at this development and pursued Shashigupta who appears to have fled with his followers to lower Indus. He probably appears there as Moeres of Curtius, a chief of Patala.[12] It is but natural that after joining the band of insurgents, Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] alias Meroes or Moeres became a leader of the group of rebels and started his struggle for realizing his bigger goals for bigger regal power.[citation needed]

Shashigupta vs Chandragupta

Scholars like Dr H. C. Seth and Dr H. R. Gupta theorize that Shashigupta was another name for Chandragupta, although other scholars appear to have taken this theory lightly.[13][14]

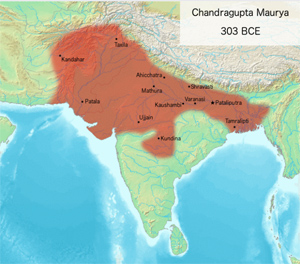

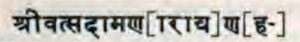

According to these scholars, it is very conspicuous that Shashigupta (Sisikottos) and Chandragupta (Sandrokotos) both names literally mean "moon-protected". "Shashi" part of Shashigupta has exactly the same meaning in Sanskrit as the "Chandra" part of Chandragupta—both mean "the moon". Thus, the two names are exact synonyms.[15] Scholars say that it is not an uncommon practice in India to substitute one's given name with a synonym.[16] Thus, it appears very likely, as many[citation needed] scholars believe, that Chandragupta may have been an alternative name for Shashigupta and both names essentially refer to same individual. This view is further reinforced if we compare the early lives of Shashigupta and Chandragupta. Both men are equally remarkable, both are military adventurers par excellence, both are rebellious and opportunists, both are equally ambitious, both are far-sighted and shrewd statesmen, and lastly but more importantly, both emerge in history precisely at the same time and at the same place in north-west India. Plutarch's classic statement that Andrakottos had met Alexander in his youth days [17] probably alludes to the years when Sisikottos had gone to help Iranians against Alexander at Bactria in 329 BCE. J. W. McCrindle concludes from Plutarch's statement that Chandragupta was native of Punjab rather than Magadha.[18] Appian's statement: "And having crossed Indus, Seleucus warred with Androkottos, the king of the Indians, who dwelt about that river (the Indus)" [19] clearly shows that Chandragupta was initially a ruler of Indus country.[13] It was only after Chandragupta's war with Seleucus which took place in 305 BCE [20] and the defeat of the latter that Chandragupta appears to have shifted his capital and residence from north-west to Pataliputra—which was also the political headquarters of the regime he had succeeded to.

Dr Seth concludes: "If Chandragupta is identical to Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus], then we find no difficulty in assuming that he indeed belonged to the Kshatriya clan of the Ashvakas whose influence extended from the Hindukush to eastern Punjab at the time of Alexander's invasion. With Mauryan conquest of other parts of India, these Ashvakas settled in other parts of India as well. From Buddhist literature, we also read of southern Ashvakas (or Assakas or Asmakas) on the bank of river Godavary in Trans-Vindhya country. The Ashvakas are said to have belonged the great Lunar dynasty..... In the region lying between Hindukush and Indus, Alexander received terrible resistance from the Kshatriya tribe called Ashvakas".[21]

Some scholars believe that the insurgency against the Greek rule in north-west had first started probably in lower Indus.[22] If this is true, then Moeris of Patala may indeed have been the pioneer in this revolution and he may be assumed to be the same person as Meroes of north-west i.e. Chandragupta Maurya,[23] alternatively known also as Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus][24] originally a native of the Swat/Kunar valleys west of Indus. Other scholars like Dr B. M. Barua, Dr H. C. Seth etc. also identify Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] with Chandragupta. As noted above, Dr J. W. McCrindle calls Chandragupta a native of Panjab.[25] American archaeologist David B. Spooner thinks that Chandragupta was an Iranian who had established a dynasty in Magadha.[26] Based on the classical evidence, Dr H. R. Gupta thinks that Chandragupta as well as Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] both belonged to northwest frontiers and both, perhaps belonged to two different sections of the Ashvaka Kshatriyas.[27][28][29] Dr Chandra Chakravarti also relates Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] and Chandragupta to northwest frontiers and states that Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] belonged to Malkand whereas Chandragupta Maurya was a ruler of Ujjanaka or Uddyana (Swat) territory of the Ashvakas.[30]

Notes

1. Daniélou 2003, p. 79.

2. Cambridge History of Ancient India, ed . E.J. Rapson, p.314.

3. Proceedings, Volume 1, Punjabi University. Dept. of Punjab Historical Studies, 1968, p - Page 33.

4. Punjab past and present: essays in honour of Dr. Ganda Singh, 1976, p 28, Harbans Singh, Norman Gerald Barrier - History.

5. Punjab revisited: an anthology of 70 research documents on the history and culture of undivided Punjab,1995, Ahmad Saleem - History.

6. Arrian's Anabasis, 1893, Book 4b, Ch xxx, and Book 5b, ch xx, E. J. Chinnock; The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great, 1896, p 112, Dr John Watson M'Crindle; The History and Culture of the Indian People, 1969, p 49, Dr Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti; Historiae Alexandri Magni, Book 8, Ch XI, Curtius.

7. Arrian Anabasis, 1893, Book 5b, Ch xviii,, E. J. Chinnock; The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great, 1896, pp 108, 109, Dr John Watson M'Crindle; Political and Social Movements in Ancient Panjab, 1964, p 172, Dr Buddha Prakash.

8. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, 1936, p 164, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute - Indo-Aryan philology, Dr H. C. Seth; The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 673, India; Punjab History Conference, Second Session, 28–30 October 1966, Punjabi University Patiala, pp 32-35, Dr H. R. Gupta; The Indian Review, 1937, p 814, edited by G.A. Natesan - India.

9. IMPORTANT NOTE: Shashigupta [Sisikottos; Sisocostus] is called an Indian by Arrian. Arrian also calls the Ashvakas as an Indian. Arrian further calls Meroes also as an Indian and an old friend of Porus. In this context, it is worth remembering that while the Kamboja sections in Trans-Hindukush region were purely Iranians, those lying in the cis-Hindukush region are known to have been partly Iranian and partly under Indian culture. Thus, whereas the Kunar (Choaspes = river of good horses) section of the Ashvaka branch is known in classical writings as "Aspasioi" (from Iranian Aspa = horse), those living in the Swat (Suastos) valley were known as Assakenoi i.e. Ashvakas (from Sanskrit Asva = horse). The dividing line between Iran and India was approximately Panjkora (or Guraeus) river (See: The Pathans, 1958, p 55/56, Olaf Caroe). According to Paul Goukowsky, Iranian language was spoken on the north of Kunar whereas Pracrit on its south (Essai sur les origines du mythe d'Alexandre: 336-270 av. J. C., 1978, p 152, n 12, Paul Goukowsky). Thus, there should be no objection if Arrian calls the Assakenoi people as well as Sisicottos & Meroes, all as Indians (See: Arrain Anabasis, Book 4b, Ch xxx; Book 5b, Ch xviii, Book 5b, Ch xx).

But more important is the meaning at this time of the words 'India' and 'Indians' to Greeks of the East like Apollodorus and 'Trogus' source'. There is no direct evidence, but the evidence from analogy is too strong to be set aside. In Alexander's day the word 'Asia' was habitually used in the sense of the Persian empire,1 [By Alexander himself: Arr. Anab. I, 16, 7 (dedication in 334), 11, 14, 8 (political manifesto in 333, 'King of Asia'), Lindian Chronicle c. 103 (dedication in 330, 'Lord of Asia'), Arr. Anab. IV, 15 ,6 (in speaking, 329-8). By Nearchus: Arr. Ind. 35, 8 ('in possession of all Asia', 325). By others: Arr. Anab. III, 9, 6; 18, 11; 25, 3; Plut. Alex. 34; Ditt.3 303. Officially in 311: Diod. XIX, 105, I. In common parlance in 307-6: Ditt.3 326, I. 23.] that is, it was used as a political term and not merely as a geographical one. Some indeed knew that there were bits of the Asiatic continent, like the spice-land of Arabia, which were not within the Persian bounds; but such lands were shadowy things, outside the range of the politics of the day. When the Seleucid empire replaced the Persian, the word 'Asia' was transferred to signify that empire, though it was now well known that considerable sections of the continent were outside the Seleucid bounds: Seleucus was 'King of Asia',2 [App. Syr. [x].] and the term 'Stations of Asia'3 [Strabo xv, 723, [x]; see p. 55 n. 1.] applied to the Seleucid survey of their empire, and the title 'Saviour of Asia' given to Antiochus IV,1 [OGIS 253; see p. 195.] are sufficient proof. To Alexander, when he crossed the Hindu Kush, 'India' meant only the Indus country which Darius had ruled;2 [Tarn in CAH vi p. 402.] but since then Greek knowledge of India had been enormously enlarged by Megasthenes. But Megasthenes, though he knew of the existence of peninsular India, had only described the Mauryan empire of Chandragupta, and the only part of India with which Greeks had been in contact since Alexander's death was the Mauryan empire, just as the only part of Asia with which they had been in contact before Alexander's birth was the Persian empire; Southern India was as shadowy a land as Southern Arabia had been. It is therefore inconceivable that 'India' should not also have had a political meaning, just as 'Asia' had always had; as 'Asia' was used in the sense first of the Persian and then of the Seleucid empires, so 'India' must have been used in the sense of the Mauryan empire. Consequently when Trogus' well-informed source called Demetrius (the Greek equivalent of) Rex Indorum,3 [Justin XLI, 6, 4, Demetrii regis Indorum. Cf. Apollodorus' phrase (Strabo XI, 516), [x].] 'King of the Indians', he meant exactly what Alexander meant when in 330 he called himself 'Lord of Asia':4 [Lindian Chronicle c. 103.] Demetrius was monarch of the Mauryan empire. Alexander in 330 had not completed the conquest of the Persian empire, but he held the great centres, and after Gaugamela what was to come seemed a foregone conclusion. Similarly, Demetrius had not yet completed the conquest of the Mauryan empire, but with the three great centres in his hand what was to come might well seem a foregone conclusion also; the one statement was as true as the other.

-- Chapter IV: Demetrius and the Invasion of India, Excerpt from The Greeks in Bactria and India, by William Woodthorpe Tarn, 2010

10. Age of Nandas, and Mauryas, 1967, p 427, K. A. Nilakanta Sastri; Maurajya Samarajya Samsakrik Itihasa, 1972, B. P. Panthar; Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahminabad, 1975, p 26, Pierre Herman Leonard Eggermont; Indological Studies, 1977, p 100, University of Sindh, Institute of Sindhology.

11. Arrian's Anabasis, Book 5b, Ch xx.

12. Historiae Alexandri Magni, ix,8,29.

13. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona,1936, Vol xviii, part 2, pp 161, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Dr H. C. Seth.

14. Dr Seth writes: "The scholars have not treated the evidence from Appian with the attention it deserved. Appian (Syriakê, c. 55) was Syrian historian, whose references to Chandragupta (Androkottos) are worthy of greatest consideration because of the very intimate relations between Seleucus Nicator, the founder of Syrian empire and Chandragupta Maurya the founder of Indian empire. Speaking of Seleucus, Appian says: 'And having crossed Indus, he warred with Androkottos, the king of the Indians, who dwelt about that river (the Indus), until he entered into an alliance and marriage affinity with him'. This statement from Appian clearly shows that Chandragupta was initially a ruler of Indus country" (H. C. Seth, 1937, p. 161).

15. Chandragupta Maurya, 1969, p 8, Lallanji Gopal; The Indian Historical Quarterly, v.13, 1937, p 361; The Indian Review, 1937, p 814, edited by G.A. Natesan.

16. Did Candragupta Maurya belong to North-Western India?, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, 1936, p 163, Dr S. C. Seth; Was Chandragupta Maurya a Punjabi?, Punjab History Conference, Second Session, 28-30 October 1966, Punjabi University Patiala, p 32, Dr H. R. Gupta

17. Plutarch's Life of Alexander, Chapter LXII; The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great, 1896, p 311, John Watson M'Crindle.

18. The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great, 1896, p 405, John Watson M'Crindle .

19. Appian's Roman History, XI.55 .

20. The Cambridge History of India, 1962, p 424, Edward James Rapson, Wolseley Haig, Richard Burn, Sir Robert Eric Mortimer Wheeler, Henry Dodwell; The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, 1910, p 839, Edited by Hugh Chisholm; A History of Asia, 1964, p 149, Woodbridge Bingham - Asia History; Chronology of World History, 1975, p 69, G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville.

21. Did Candragupta Maurya belong to North-Western India?, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, 1936, Vol xviii, part 2, pp 158-164, Dr S. C. Seth.

22. Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 236, Dr H. C. Raychaudhury.

23. Studies in Indian History and Civilization, 1962, p 133, D Buddha Prakash; Studies in Alexander's Campaigns, 1973, p 40, Binod Chandra Sinha.

24. Poisoning of Alexander ( part 2 ), Newsfinder, History section, Dr Ratanjit Pal.

25. The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great, 1896, p 405, John Watson M'Crindle

26. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 1915, Part I, p 406, Part II, pp 416-17.

27. Was Chandragupta Maurya a Punjabi?, Punjab History Conference, Second Session, October 28-30, 1966, Punjabi University Patiala, p 32-35, Dr H. R. Gupta.

28. Punjab revisited: an anthology of 70 research documents on the history and culture of undivided Punjab, 1995, Ahmad Saleem - History.

29. Punjab past and present: essays in honour of Dr. Ganda Singh, 1976, p 28, Ganda Singh - History.

30. The Racial History of Ancient India, 1944, p 814, Chandra Chakraberty.

References

• Daniélou, Alain (2003) [1971], A Brief History of India, Inner Traditions, ISBN 978-1-59477-794-3

• Indian Historical Quarterly, vol.8 (1932), B. M. Barua

• Indian Culture, vol. X, p. 34, B. M. Barua

• The Zoroastrian period of Indian history, (Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1915, 1915, (Pt. II), pp 406, 416-17, D.B. Spooner

• Invasion India by Alexander the Great, 1896, p 112, 405/408 J. W. McCrindle

• Did Candragupta Maurya belong to North-Western India?, Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, 1936, Vol xviii, part 2, p 158-165, Dr S. C. Seth

• Was Chandragupta Maurya a Punjabi?, Punjab History Conference, Second Session, October 28-30, 1966, Punjabi University Patiala, p 32-35, Dr H. R. Gupta

• They Taught Lessons to Kings, Gur Rattan Pal Singh; Article in Sunday Tribune, January 10, 1999

• The Indian Review, 1937, p 814, edited by G. A. Natesan

• The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 361, India

• Indian Culture, 1934, p 305, Indian Research Institute- India

• Note on Saśigupta and Candragupta, The Indian Historical Quarterly/edited by Narendra Nath Law, Vol. XIII. Articles:, Miscellany,. Reprint. Delhi, Caxton, 1998, 39 Volumes

• Ashoka and His Inscriptions, 1968, p 51, Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa

• Paradise of Gods, 1966, p 312, Qamarud Din Ahmed - West Pakistan (Pakistan)

• Poisoning of Alexander ( Part 2 ), Newsfinder, 2008, History Section, Dr Ratanjit Pal

• Age of Nandas, and Mauryas, 1967, p 427, K. A. Nilakanta Sastri

• Maurajya Samarajya Samsakrik Itihasa, 1972, B. P. Panthar

• Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan and the Siege of the Brahminabad, 1975, p 26, Pierre Herman Leonard Eggermont

• Indological Studies, 1977, p 100, University of Sindh, Institute of Sindology

See also

• Sophagasenus