"Sandrocottus", Excerpt from "History of Classical Sanskrit Literature"

by Kavyavinoda, Sahityaratnakara M. Krishnamachariar, M.A., M.I., Ph.D., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of London (Of the Madras Judicial Service), Assisted by His Son M. Srinivasachariar, B.A., B.L., Advocate, Madras

1937

...

The Introduction deals with several topics of general interest allied to the study of Classical Sanskrit Literature… Of foremost importance, there is the subject of Indian Chronology. India has its well written history, and the Puranas exhibit that history and chronology. To the devout Hindu, and to a Hindu who will strive to be honest in the literary and historical way, Puranas are not 'pious frauds.' In the hands of many Orientalists, India has lost (or has been cheated out of) a period of 10-12 centuries in its political and literary life, by the assumption of a faulty Synchronism of Candragupta Maurya and Sandrocottus of the Greek works, and all that can be said against that "Anchor-Sheet of Indian Chronology" has been said in this Introduction…[for] our "Professors of Indian History," that have given a longevity and a garb of truth to it by repetition, there is to my mind no excuse or expiation, if at all it be a confession of neglect and a recognition of India's glorious past in its entire truth…

Of the several kingdoms and dynasties of which Puranas have recorded political history, there is the kingdom of Magadha. For our present purposes of sifting and settling the chronology of India up to the Christian era, the history of Magadha is particularly relevant, for it is at Magadha, 'Chandragupta' and 'Asoka' ruled, and it is on these names that the modern computation of dates has been based for everything relating to India's literary history, and it is those two names that make the heroes of the theory of Anchor Sheet of Indian Chronology.

The Kingdom of Magadha was founded by Brhadratha, son of Uparicara Vasu, the 6th in descent from Kuru of the Candra Vamsa. That happened 161 years before Mahabharata war. Tenth in descent from Brhadratha was Jarasandha. Jarasandha perished at the hand of Kamsa, and in his place Sahadeva was installed on the throne. Sahadeva was an ally of Pandavas and was killed in the war, that is in 3139 BC. His son Marjari (or Somadhi or Somavit) was his successor and the first king of Magadha after the war. From him 22 kings of this Barhadratha dynasty ruled over Magadha for 1006 years, or roughly stated, for 1000 years…

The following is the description of the Nanda Dynasty as given in the Kaliyuga Rajavrttanta: —...

"It will be clear from these numerous extracts quoted in full from the various important Puranas, which are practically identical with one another, that the Founder of this Dynasty was Mahapadma, well known otherwise as Dhana Nanda, that he was the son of Mahanandin, the last of the Saisunaga Dynasty, that he was born to that king from a Sudra wife, that he was most avaricious and powerful, that he extirpated the Kshattriya rulers of his time like a second Parasurama, the destroyer of the Kshattriyas in the olden times, that he subjugated the different lines of Kings of the Solar and Lunar dynasties who began to rule in the various parts of Northern India from the time of the Mahabharata War commencing from the Coronation of Yudhishthira in the year 3139 BC, that he became a paramount King and Emperor of the whole of India between the Himalaya and the Vindhya mountains by putting an end to the ancient families of Kings, such as Aikshvakus, Panchalas, Kauravyas, Haihayas, Kalakas, Ekalingas, Surasenas, Maithilas etc., who ceased to rule as separate dynasties ever since that time, that he ruled the kingdom under one umbrella for a period of 88 years, that his 8 sons jointly ruled the kingdom for a short period of 12 years, that these Nine Nandas, including the father and his eight sons ruled Magadha altogether for a total period of 100 years from 1635 to 1535 BC, that these Nandas were extirpated by the Brahman Chanakya, well known as Kautilya, on account of his crooked and Machiavellian policy, and that he replaced his protege Chandragupta, an illegitimate son of Mahapadma Nanda by his Sudra wife Mura on the throne of his father."

But Vincent A. Smith chooses to assign to these nine Nandas a total period of only 45 years for their reigns.

Candragupta came to the throne as the son of Mura, so he was a Maurya, and the dynasty which he started was Maurya dynasty. Candragupta's son was Bindusara, and Bindusara's son was Asoka or Asokavardhana…

Thus Candragupta reigned from 1535 to 1501 BC, for 34 years, Bindusara from 1501 to 1473, for 28 years, and Asoka from 1473 to 1437 BC, for 36 years. And in all there were twelve Kings of Maurya dynasty, the last of whom was Brhadratha.

Regarding this dynasty the readings and versions of the Puranas are hopelessly confused and incorrect but the passages quoted, of which the authenticity is doubtless, show that the Maurya dynasty lasted for 316 years from 1535 to 1219 BC.

Pusyamitra was the commander-in-chief of Brhadratha. He removed his master and ascended the throne. Thus he started the Sunga dynasty. According to Matsya Purana, there were ten kings of this dynasty who ruled in all for 30 years from 1219 BC to 919 BC…

Thus, these 32 kings of the Andhra Dynasty reigned for a total period of 506 years, although in summing up their total period of reigns, it states in round figures that they ruled for full 500 years (instead of 506 years); and their kingdom passed into the hands of Candragupta, son of Ghatotkaca Gupta and grandson of Sri Gupta, who appears to have come from Sri Parvata or Nepal and originally entered the service of Vijayasri Satakarni as one of his generals and with whose help he managed to maintain his tottering kingdom….

Sandrocottus.

It was Sir William Jones, the Founder and President of the Society instituted in Bengal for inquiry into the History and Antiquities, the Arts, Sciences and Literature of Asia, who died on 27th April 1794, that suggested for the first time an identification to the notice of scholars. In his 'Tenth Anniversary Discourse,' delivered by him on 28th February 1793, on "Asiatic History, Civil and Natural," referred to the so-called discovery by him of the identity of Candragupta, the Founder of the Maurya Dynasty of the Kings Magadha, with Sandrocottus of the Greek writers of Alexander's adventures, thus:

"The Jurisprudence of the Hindus and Arabs being the field, which I have chosen for my peculiar toil, you cannot expect, that I should greatly enlarge your collection of historical knowledge, but I may be able to offer you some occasional tribute, and I cannot help mentioning a discovery which accident threw in my way, though my proofs must be reserved for an essay, which I have destined for the fourth volume of your Transactions. To fix the situation of that Palibothra, (for there may have been several of the name) which was visited and described by Megasthenes, had always appeared a very difficult problem, for, though it could not have been Prayaga where no ancient metropolis ever stood, nor Canyacubja which has no epithet at all resembling the word used by the Greeks, nor Gaur, otherwise called Lacshmanavati, which all know to be a town comparatively modern, yet we could not confidently decide that it was Pataliputra, though names and most circumstances nearly correspond, because that renowned capital extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, while Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and Erranaboas, which the accurate M. D'Anville had pronounced to be "Yamuna", but this only difficulty was removed when I found in a Classical Sanskrit book near two thousand years old, that Hiranyabahu or golden-armed, which the Greeks changed to Erranaboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was in fact another name for the Sona itself, though Megasthenes from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately.1 [Asiatic Researches, IV. 10-11.] This discovery led to another of greater moment, for Chandragupta, who, from a military adventurer, became like Sandracottus, the sovereign of Upper Hindustan, actually fixed the seat of his empire at Pataliputra, where he received ambassadors from foreign princes, and was no other than that very Sandracottus who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator, so that we have solved another problem to which we before alluded, and may in round numbers consider the twelve and three hundredth years before Christ as two certain epochs between Rama who conquered Silan a few centuries after the flood, and Vicramaditya who died at Ujjayini fifty-seven years before the beginning of our era."…

Earlier in the same discourse Sir William had mentioned his authorities for the statement that Candragupta became sovereign of upper Hindusthan, with his Capital at Pataliputra. "A most beautiful poem," said he "by Somadeva, comprising a long chain of instructive and agreeable stories, begins with the famed revolution at Pataliputra by the murder of king Nanda with his eight sons, and the usurpation of Chandragupta, and the same revolution is the subject of a tragedy in Sanskrit entitled 'The Coronation of Chandra.'"1 [Ibid 6.] Thus he claimed to have identified Palibothra with Pataliputra and Sandrokottus with Candragupta, and to have determined 300 BC "in round numbers" as a certain epoch between two others which he called the conquest of Silan by Rama: "1200 BC," and the death of Vikramaditya at Ujjain in 57 BC.

In the Discourse referred to, Sir William barely stated his discovery, adding "that his proofs must be reserved" for a subsequent essay, but he died before that essay could appear.

The theme was taken immediately by Col. [Captain Francis] Wilford in Volume V of the Asiatic Researches. Wilford entered into a long and fanciful disquisition on Palibothra, and rejected Sir William's identification of it with Pataliputra, but he accepted the identification of Sandrocottus with Candragupta in the following words: —"Sir William Jones from a poem written by Somadeva and a tragedy called the Coronation of Chandra or Chandragupta discovered that he really was the Indian king mentioned by the historians of Alexander under the name of Sandrocottus. These poems I have not been able to procure, but I have found another dramatic piece entitled Mudra-Rachasa,1 [This spelling shows that Wilford saw not the Sanskrit drama but some vernacular visions of it.] which is divided into two parts, the first may be called the Coronation of Chandra."2 [Asiatic Researches, V, 262. Wilford wrongly names the author of the drama as Amanta (or Ananta).]

P. 262: Chandra-Gupta, or he who was saved by the interposition of Lunus or the Moon, is called also Chandra in a poem quoted by Sir William Jones. The Greeks call him Sandracuptos, Sandracottos, and Androcottos. Sandrocottos is generally used by the historians of Alexander; and Sandracuptos is found in the works of Athenaeas. Sir William Jones, from a poem written by Somadeva, and a tragedy called the coronation of Chandra or Chandra-Gupta [Asiatick Researches, vol. IV, p. 6, 11.], discovered that he really was the Indian king mentioned by the historians of Alexander, under the name of Sandracottos. These two poems I have not been able to procure; but, I have found another dramatic piece, intitled Mudra-Racshasa, or the Seal of Racshasa, which is divided into two parts: the first may be called the coronation of Chandra-Gupta, and the second the reconciliation of Chandra-Gupta with Mantri-Racshasa, the prime minister of his father.

The history of Chandra-Gupta is related, though in few words, in the Vishnu-purana, the Bhagawat, and two other books, one of which is called Brahatcatha, and the other is a lexicon called Camandaca: the two last are supposed to be about six or seven hundred years old. In the Vishnu-purana we read, "Unto Nanda shall be born nine sons; Cotilya, his minister shall destroy them, and place Chandra-Gupta on the throne."

In the Bhagawat we read, "from the womb of Sudri, Nanda shall be born. His eldest son will be called Sumalva, and he shall have eight sons more; these, a Brahmen (called Cotilya, Vatsayana, and Chanacya in the commentary) shall destroy, after them a Maurya shall reign in the Cali-yug. This Brahmen will place Chandra-Gupta on the throne." In the Brahatcatha it is said, that this revolution was effected in seven days, and the nine children of Nanda put to death. In the Camandaca, Chanacyas is called Vishnu-Gupta. The following is an abstract of the history of Chandra-Gupta from the Mudra-Racshasa:

Nanda, king of Prachi, was the son of Maha Nandi, by a female slave of the Sudra tribe: hence Nanda was called a Sudra. He was a good king, just and equitable, and paid due respect to the Brahmens: he was avaricious, but he respected his subjects. He was originally king of Magada, now called South-Bahar, which had been in the possession of his ancestors since the days of Crishna; by the strength of his arm he subdued all the kings of the country, and like another Parasu-Rama destroyed the remnants of the Cshettris. He had two wives, Ratnavati and Mura. By the first he had nine sons, called the Sumalyadicas, from the eldest, whose name was Sumalya (though in the dramas, he is called Sarvarthasidd'hi); by Mura he had Chandra-Gupta, and many others, who were known by the general appellation of Mauryas, because they were born of Mura...

-- XVII. On the Chronology of the Hindus, by Captain Francis Wilford, Asiatic Researches; or, Transactions of the Society Instituted in Bengal, For Inquiring Into the History and Antiquities, The Arts, Sciences, and Literature, Of Asia, Volume the Fifth, 1799

[Horace Hayman] Wilson further amended the incorrect authorities relied on by Sir William Jones, and said in his Preface to Mudra-Rakshasa3 [Theatre of the Hindus, Vol. II.] that by Sir William's "a beautiful poem by Somadeva" was "doubtless meant the large collection of tales by Somabhatta the Vrihat-katha."4 [Wilson again is not quite correct in his Bibiography. Somadeva's large collection of tales is entitled Kathasarit sagara and is an adaptation into Sanskrit verse of an original work in the Paisaci language called Brihat, Katha, composed by one Gunadhya.]

It may not here be out of place to offer a few observations on the identification of Chandragupta and Sandrocottus. It is the only point on which we can rest with anything like confidence in the history of the Hindus, and is therefore of vital importance in all our attempts to reduce the reigns of their kings to a rational and consistent chronology. It is well worthy, therefore, of careful examination; and it is the more deserving of scrutiny, as it has been discredited by rather hasty verification and very erroneous details.

Sir William Jones first discovered the resemblance of the names, and concluded Chandragupta to be one with Sandrocottus (As. Res. vol. iv. p. 11). He was, however, imperfectly acquainted with his authorities, as he cites "a beautiful poem” by Somadeva, and a tragedy called the coronation of Chandra, for the history of this prince. By the first is no doubt intended the large collection of tales by Somabhatta, the Vrihat-Katha, in which the story of Nanda's murder occurs: the second is, in all probability, the play that follows, and which begins after Chandragupta’s elevation to the throne. In the fifth volume of the Researches the subject was resumed by the late Colonel Wilford, and the story of Chandragupta is there told at considerable length, and with some accessions which can scarcely be considered authentic. He states also that the Mudra-Rakshasa consists of two parts, of which one may be called the coronation of Chandragupta, and the second his reconciliation with Rakshasa, the minister of his father. The latter is accurately enough described, but it may be doubted whether the former exists.

Colonel Wilford was right also in observing that the story is briefly related in the Vishnu-Puranaa and Bhagavata, and in the Vrihat-Katha; but when he adds, that it is told also in a lexicon called the Kamandaki he has been led into error. The Kamandaki is a work on Niti, or Polity, and does not contain the story of Nanda and Chandragupta. The author merely alludes to it in an honorific verse, which he addresses to Chanakya as the founder of political science, the Machiavel of India.

The birth of Nanda and of Chandragupta, and the circumstances of Nanda’s death, as given in Colonel Wilford’s account, are not alluded to in the play, the Mudra-Rakshasa, from which the whole is professedly taken, but they agree generally with the Vrihat-Katha and with popular versions of the story. From some of these, perhaps, the king of Vikatpalli, Chandra-Dasa, may have been derived, but he looks very like an amplification of Justin's account of the youthful adventures of Sandrocottus. The proceedings of Chandragupta and Chanakya upon Nanda's death correspond tolerably well with what we learn from the drama, but the manner in which the catastrophe is brought about (p. 268), is strangely misrepresented. The account was no doubt compiled for the translator by his pandit, and it is, therefore, but indifferent authority.

It does not appear that Colonel Wilford had investigated the drama himself, even when he published his second account of the story of Chandragupta (As. Res. vol. ix. p. 93), for he continues to quote the Mudra-Rakshasa for various matters which it does not contain. Of these, the adventures of the king of Vikatpalli, and the employment of the Greek troops, are alone of any consequence, as they would mislead us into a supposition, that a much greater resemblance exists between the Grecian and Hindu histories than is actually the case.

Discarding, therefore, these accounts, and laying aside the marvellous part of the story, I shall endeavour, from the Vishnu and Bhagavata-Puranas, from a popular version of the narrative as it runs in the south of India, from the Vrihat-Katha, [For the gratification of those who may wish to see the story as it occurs in these original sources, translations are subjoined; and it is rather important to add, that in no other Purana has the story been found, although most of the principal works of this class have been carefully examined.] and from the play, to give what appear to be the genuine circumstances of Chandragupta's elevation to the throne of Palibothra.

-- Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus, Translated from Original Sanskrit in Two Volumes, by Horace Hayman Wilson, Volume II, 1871

Max Muller then elaborated the discovery of this identity in his Ancient Sanskrit Literature. To him this identity was a settled incontrovertible fact. On the path of further research, he examined the chronology of the Buddhists according to the Northern or the Chinese and the Southern or the Ceylonese traditions, and summed this up:

"Everything in Indian Chronology depends upon the date of Chandragupta. Chandragupta was the grand-father of Asoka, and the contemporary of Selukus Nikator. Now, according to the Chinese chronology, Asoka would have lived, to waive the minor differences, 850 or 750 BC, according to Ceylonese Chronology, 315 BC. Either of these dates is impossible because it does not agree with the chronology of Greece."

'Everything in Indian Chronology depends upon the date of Chandragupta' is the declaration. How is that date to be fixed? The Puranic accounts were of course beneath notice. The Buddhist chronologies were conflicting, and must be ignored. The Greek synchronism comes to his rescue:

"There is but one means by which the history of India can be connected with that of Greece, and its chronology must be reduced to its proper limits, [that is, by the clue afforded by] ...the name of Sandrocottus or Sandrocyptus, the Sanskrit Chandragupta."

From classical writers — Justin, Arrian, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, Quintus Curtius, and Plutarch — a formidable array, all of whom however borrowed their account from practically the same sources — he puts together the various statements concerning Sandrocottus, and tries to show that they all tally with the statements made by Indian writers about the Maurya king Candragupta.

"The resemblance of this name [says he] with the name of Sandrocottus or Sandrocyptus was first, I believe, pointed out by Sir William Jones. [Captain Francis] Wilford, [Horace Hayman] Wilson, and Professor [Christian] Lassen have afterwards added further evidence in confirmation of Sir W. Jones's conjecture, and although other scholars, and particularly M. Troyer in his edition of the Rajatarangini, have raised objections, we shall see that the evidence in favour of the identity of Chandragupta and Sandrocottus or Sandrocyptus is such as to admit of no reasonable doubt."

Max Muller only repeats that the Greek accounts of Sandrocottus and the Indian accounts of Chandragupta agree in the main, both speaking of a usurper who either was base-born himself or else overthrew a base-born predecessor, and that this essential agreement would hold whether the various names used by Greek writers — Xandrames, Andramas, Aggraman, Sandrocottus and Sandrocyptus — should be made to refer to two kings, the overthrown and the overthrower, or all to one, namely the overthrower himself, though personally he is inclined to the view that the first three variations refer to the overthrown, and the last two to the overthrower. He explains away the difficulty in identifying the sites of Palibothra and Pataliputra geographically by "a change in the bed of the river Sone." He passes over the apparent differences in detail between the Greek statements on the one hand and the Hindu and Buddhist versions on the other quite summarily, declaring that Buddhist fables were invented to exalt, and the Brahmanic fables to lower Chandragupta's descent! Lastly with respect to chronology the Brahmanic is altogether ignored, and the Buddhist is "reduced to its proper limits," that is, pulled down to fit in with Greek chronology.

Priyadasi.

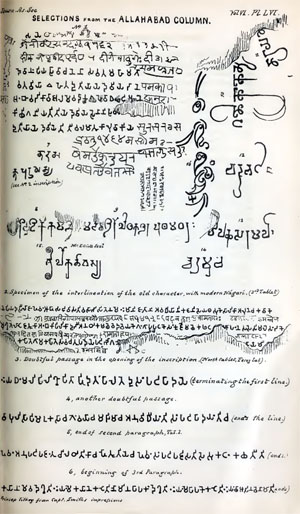

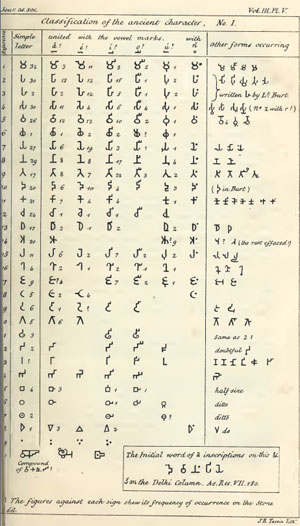

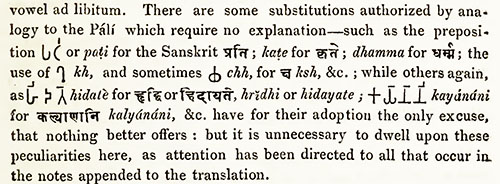

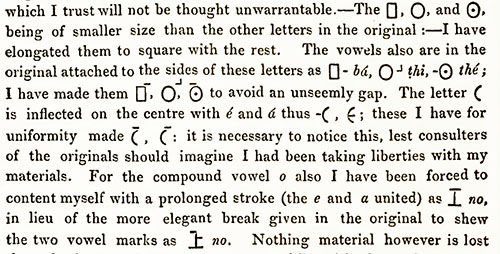

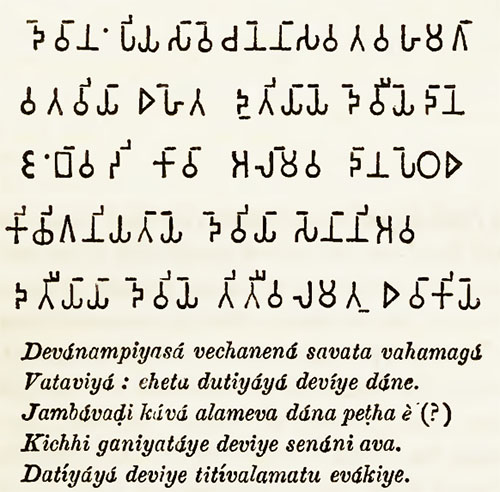

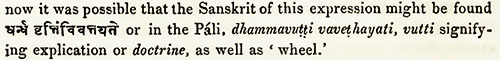

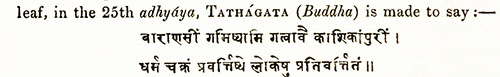

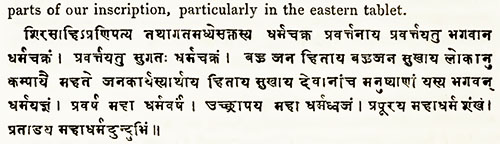

Next came inscriptions of Priyadasi1 [The Edicts are edited in IA, 6, 10, 14, 17, 18, 19, 22, 34, 37, 38. On the Edicts, see IA, XIII 804, XX 1, 85, 229, XXXV 220 XXXIV 246, XXXVIII 151, XLVII, 48. Also, D. R. Bhandarkar, Asoka, Calcutta, V. A. Smith, Asoka, Oxford, F. W. Thomas, Les Vivasti de Asoka, JA, (1910), E. Hultzsch, Date of Asoka, JRAS, (1914) 943. H. H. Wilson, Identity of Asoka, JRAS, (o s), XXII, 177 243, (1901) 827 858, V. A. Smith, Authorship of Piyadasi inscriptions, JRAS, (1901), 485; Asokavadana, JRAS, [1901) 545, Bindusara, JRAS, (1901), 334.] These edicts published in the tenth and twelfth years of Asoka's reign (253 and 251 BC) are found in distinct places in the extreme East and West of India. As revealed in these engraved records, the spoken dialect was essentially the same throughout the wide and fertile regions lying between the Vindhya and Himalayas, and between the mouths of the Indus and the Ganges. The language appears in three varieties, which may be named the Punjabi, the Ujjaini and the Magadhi. These may point to a transitional stage between Sanskrit and Pali. "The language of the inscriptions," says Prinsep, "although necessarily that of their date and probably that in which the first propagators of Buddhism expounded their doctrines, seems to have been the spoken language of the people of Upper India than a form of speech peculiar to a class of religionists or a sacred language, and its use in the edicts of Piyadasi, although incompatible with their Buddhistic origin, cannot be accepted as a conclusive proof that they originated from a peculiar form of religious belief."

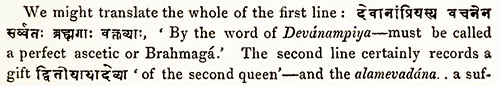

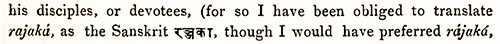

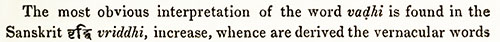

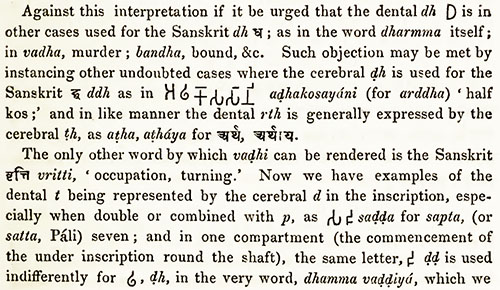

Asoka's name does not occur in these inscriptions, but that these purport to emanate from a king who gives his formal title in various Prakrit forms of which the Sanskrit would be Devanampriyah Priyadarsi raja. It was James Prinsep that first ascribed Asoka's edicts to Devanampiya-Tissa of Ceylon.1 [E. Hultzsch, Date of Asoka, JRAS, (1914), 948.] The discovery of the Nagarjuna Hill cave-inscriptions of Sashalata Devanampiya [Barabar Caves], whom he at once identified with Dasaratha, the grandson of the Maurya king Asoka, and the fact that Turnour had found Piyadassi or Piyadassana used as a surname of Asoka in the Dipavamsa, induced Prinsep to abandon his original view, and to identify Devanampriya Priyadarsan with Asoka himself.[/b][/size]

In February 1838, Prinsep published the text and a translation of the second rock edict, Girnar version of it (1 3) the words Amtiyako Yonaraja and in the Dhauli version (1, 1) Amtiyoke nama Yona-laja, and identified the Yona king Antiyaka or Antiyoka with Antiochus III of Syria.2 [JASB, VII 156.] In March 1838, he discovered in the Girnar edict xiii (1, 8), the names of Turamaya, Amtikona,3 [In reality Girnar and Kalsi read Amtekina, Shahbazgarhi Amtikini. Buhler (ZDMG, 40 137) justly remarked that these two forms would rather correspond to Antigenes than to Antigonus. But no king named Antigenes is known to us, though it was the name of one of the officers of Alexander the Great, who was executed, together with Eumenes in BC 316, being then satrap of Suslana.] and Maga, whom he most ingeniously identified with Ptolemy II Philadelphos of Egypt, Antigonus Gonatas of Macedonia (?) and Magas of Cyrine. At the same time he modified his earlier theory and now referred the name Antiyoka to Antiochus I or II of Syria, preferably the former.

On the Girnar rock the name of a fifth king who was mentioned after Maga is lost. The Shahbazgarhi version calls him Alikasundara. E. Norris recognized that this name corresponds to the Greek [x], and suggested hesitatingly that Alexander of Epirus, the son of Pyrihus, might be meant by it.4 [JRAS (o s), 205.] This identification was endorsed by Westerguard,5 [Zwei Abhandlungen, translated from the Danish into German by Stenzlet (Breslau, 1862), p 120 f.] Lassen,6 [Ind. Alt., 253 ff.] and Senart.7 [IA, XX, 242.] But Professor Beloch thinks that Alexander of Corinth, the son of Craterus, had a better claim.8 [Griech, Gesch., 3, 2, 105.]

"The mention of these five contemporaries in the inscriptions of Devanampriya Priyadarshi," says E. Hultzsch, "confirms in a general way the corrections of Prinsep's identification of the latter with Asoka, the grandson of Chandragupta, whose approximate time we know from Greek and Roman records. Antiochus I Soter of Syria reigned BC 280-261, his son Antiochus II Theos 261-246, Ptolemy II Philadelphos of Egypt 285-247, Antigonus Gonates of Macedonia 276-239, Magas of Cyrene c 300- c. 250, Alexander of Epirus 272-c 255, and Alexander of Corinth 252-c 244."

This identification of Sandrocottus with Candragupta Maurya furnished a very certain starting point in investigating what appeared to be such a huge field of uncertainties as Indian Chronology. Thus, according to Buddhist traditions, it is said, Buddha died 162 years before Candragupta. Max Muller supposes that "Chandragupta became king about 315 BC, and so he places the death of Buddha 162 plus 315 or 477 BC. Or again, 32 years after Chandragupta, Asoka is said to have become king, that is 315-52 or 263 BC, and his "inauguration" is said to have taken place in 259 BC. At the time of Asoka's inauguration, 218 years had elapsed since the conventional date of Buddha's death." Hence Buddha must have also died in 477 BC.

Thus came in the Anchor Sheet of Indian Chronology. It fell to the glorious lot of Vincent A. Smith to sponsor this hypothesis and instal it on a firmer pedestal. Glory is god-made and V. A. Smith was destined for it.1 [The reader may well be reminded of the facetious address of Gopi to Sri Krsna: [x]] He took the chronological identity so premised by the predecessors in this historical hierarchy as the basis of further calculation of the exact dates of the different dynasties that ruled over Magadha before and after the Mauryas. He was able to invoke the aid of numismatics in addition to epigraphy. He could interpret the eras, particularly the Gupta era of the inscriptions, and the legends on the coins, and discover a confirmation of the earlier opinions. He could not however get over, as if by compunction, the need to follow the Puranas in the enumeration of the kings and then dynasties, he took the dynasties and the succession of kings as they were, he did not call them fictitious. He had objection to the long periods of years that these Puranas sometimes assigned to particular kings or dynasties. They were improbable and fanciful and so on their face unreliable. So he set out to sift the intervals of time and adjust the dates and periods on a rational basis, a basis that would quite convince the modern mind of a reasonable probability. The device of reduction of time is in short this:

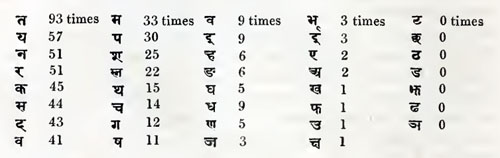

Where the Puranas have different readings the shortest number of years is adopted, where the Puranas give a long period to any reign, it is reduced to 20 years as the average ascertainable in royal histories elsewhere, where the Puranas give only brief terms of a few years or a few months, that is adopted as correct. The result of these reductions will be seen below —

Dynasty / Puranas / V. Smith

Nandas / 100 (1635-1535 BC) / 45

Mauryas / 316 (1535-1219 BC ) / 137

Sungas / 300 (1219-919 BC) / 112

Kanvas / 85 ( 919-834 BC) / 45

Andhras / 506 (834-328 BC) / 289

Guptas / 245 (328-83 BC) / 149

Thus, according to Vincent Smith, Candragupta became king in 322 BC, and Buddha died in 487 BC, this allows 50 years for the Nandas before Candragupta, and 250 years for the Saisunagas before the Nandas. And so he begins his Early History from about 602 BC. Likewise, starting from 322 BC, V. Smith allows 137 years for the Maurya Dynasty, and places Sunga kings in 185-73 BC, and Kanva kings in 73 to 28 BC, and so on bringing the list down to Andhras and Guptas. I extract the passage:

"Although the discrepant traditionary materials available do not permit the determination with accuracy of the chronology of the Saisunaga and Nanda dynasties, it is, I venture to think, possible to attain a tolerably close approximation to the truth, and to reconcile some of the traditions. The fixed point from which to reckon backwards is the year 322 BC, the date for the succession of Chandragupta Maurya, which is certainly correct, with a possible error not exceeding three years. The second principal datum is the list of ten kings of the Saisunaga dynasty as given in the oldest historical entries in the Puranas, namely those in the Matsya and the Vayu, the general correctness of which is confirmed by several lines of evidence, and the third is the probable date of the death of Buddha.

Although the fact that the Saisunaga dynasty consisted of ten kings may be admitted, neither the duration assigned by the Puranas to the dynasty as a whole, nor that allotted to certain reigns, can be accepted. Experience proves that in a long series an average of twenty-five years to a generation is rarely attained, and that this average is still more rarely exceeded in a series of reigns as distinguished from generations.

The English series of ten reigns from Charles II to Victoria, inclusive, 16+9-1901 (reckoning the accession of Charles II from the death of his father in 1649), occupied 252 years, and included the two exceptionally long reigns of George III and Victoria, aggregating 124 years. The resultant average, 252 years per reign, may be taken as the maximum possible, and consequently 232 years are the maximum allowable for the ten Saisunaga reigns. The Puranic figures of 321 (Matsya) and 332 (Vayu) years, obtained by adding together the durations of the several reigns may be rejected without hesitation as being incredible. The Matsya account concludes with the statement, 'These will be the ten Saisunaga kings. The Saisunagas will endure 360 years, being kings with Kshatriya kinsfolk.' Mr. Pargiter suggests that the figures '360' should be interpreted as '163'. If that interpretation be accepted the average length of reign would be only 16.3. and it would be difficult to make Buddha (died cir 487) contemporary with Bimbisara and Ajatasatru. It is more probable that the dynasty lasted for more than two centuries.

As stated in the text, the traditional periods assigned to the Nanda dynasty of either 100 or 150 years for two generations cannot be accepted. A more reasonable period of fifty years may be provisionally assumed. We thus get the 302 (252 plus 50) as the maximum admissible period for the Saisunaga and Nanda dynasties combined, and, reckoning backwards from the fixed point, 322 BC. The Year 624 BC is found to be the earliest possible date for Sisunaga, the first king. But of course the true date may be, and probably is, somewhat later, because it is extremely unlikely that twelve reigns (ten Saisunaga and two Nanda) should have attained an average of 25.16 years.

The reigns of the fifth and sixth kings, Bimbisara or Srenika, and Ajatasatru or Kunika, were well remembered owing to the wars and events in religious history which marked them. We may therefore assume that the lengths of those reigns were known more or less accurately, and are justified in accepting the concurrent testimony of the Vayu and Matsya Puranas, that Bimbisara reigned for twenty-eight years.

Ajatasatru is assigned twenty-five or twenty-seven years by different Puranas, and thirty-two years by Tibetan and Ceylonese Buddhist tradition. I assume the correctness of the oldest Puranic list, that of the Matsya, and take his reign to have been twenty-seven years. The real existence of Darsaka (erroneously called Vamsaka by the Matsya) having been established by Bhasa's Vasavadatta [Svapnavasavadattam: The dream of Vasavadatta is a Sanskrit play in six acts written by the ancient Indian poet Bhāsa. The plot of the drama is drawn from the romantic narratives about the Vatsa king Udayana and Vasavadatta, the daughter of Pradyota, the ruler of Avanti, which were current in the poet's time and which seem to have captivated popular imagination. The main theme of the drama is the sorrow of Udayana for his queen Vasavadatta, believed by him to have perished in a fire, which was actually a rumour spread by Yaugandharayana, a minister of Udayana to compel his king to marry Padmavati, the daughter of the king of Magadha.], his reign may be assigned twenty-four years, as in the Matsya Udaya, who is mentioned in the Buddhist books, and is said to have built Pataliputra, is assigned thirty-three years by the Puranas, which may pass.

The Vayu and Matsya Puranas respectively assign eighty-five and eighty-three years to the sum of the reigns of kings numbers 9 and 10 together. These figures are improbably high, and it is unlikely that the two reigns actually occupied more than fifty years. The figure 46 is assumed.

The evidence as far as it goes, and at best it does not amount to much, indicates that the average length of the later reigns was in excess of the normal figure. We may assume, therefore, that the first four reigns, about which nothing is known, must have been comparatively short, and did not exceed some seventy or eighty years collectively. An assumption that these reigns were longer would unduly prolong the total duration of the dynasty, the beginning of which must be dated about 600 BC, or a little earlier.

The existence of a great body of detailed traditions, which are not mere mythological legends, sufficiently establishes the facts that both Mahavira, the Jain leader, and Gautama Buddha, were contemporary to a considerable extent with one another and with the kings Bimbisara and Ajatasatru.

Tradition also indicates that Mahavira predeceased Buddha. The death of these saints form well-marked epochs in the history of Indian religion, and are constantly referred to by ecclesiastical writers for chronological purposes. It might therefore be expected that the traditional dates of the two events would supply at once the desired clue to the dynastic chronology. But close examination of conflicting traditions raises difficulties. The year 527 (528-7) BC, the most commonly quoted date for the death of Mahavira, is merely one of several traditionary dates, and it seems to be impossible to reconcile the Jain traditions either among themselves or with the known approximate date of Chandragupta."