by the Hon'ble George Turnour, Esq. of the Ceylon Civil Service*

[*We consider it a duty to insert this paper, just received, in the same volume with our version of the inscription, adding a note or two in defence of the latter where we consider it still capable of holding its ground against such superior odds!— Ed. [J. Prinsep]]

The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. VI, Part II

Jul-Dec, 1837

George Turnour pulls a Dipavamsa rabbit out of his hat!

I have read with great interest, in the Asiatic Journal of July last, your application of your own invaluable discovery of the Lat alphabet, to the celebrated inscriptions on Feroz's column, at Delhi.

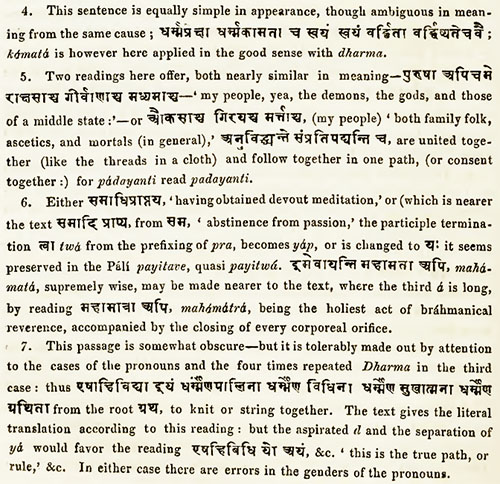

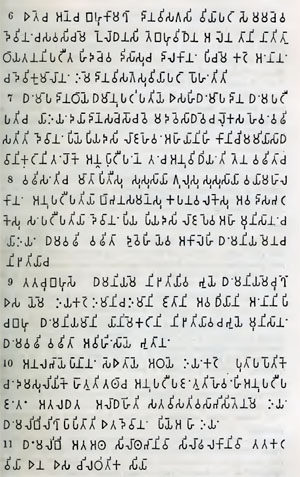

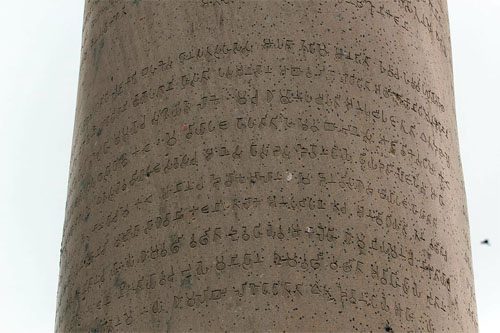

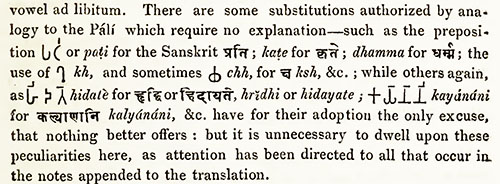

When we consider that these inscriptions were recorded upwards of two thousand years ago, and that the several columns on which they are engraven have been exposed to atmospheric influences for the whole of that period, apparently wholly neglected; when we consider also, that almost all the inflections of the language in which these inscriptions are composed, occur in the ultimate and penultimate syllables, and that these inflections are chiefly formed by minute vowel symbols, or a small anuswara dot; and when we further find that the Pali orthography of that period, as shewn by these inscriptions was very imperfectly defined — using single for double, and promiscuously, aspirated and unaspirated consonants; and also, without discrimination, as to the class each belonged, the four descriptions of n — the surprise which every reasonable investigator of this subject must feel will be occasioned rather by the extent of the agreement than of the disagreement between our respective readings of these ancient records.

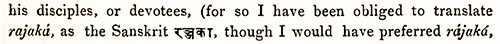

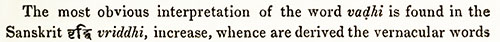

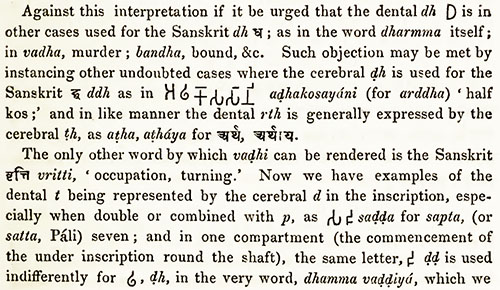

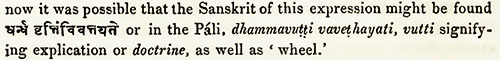

Another very effective cause has, also, been in operation to produce a difference in our readings. You have analysed these inscriptions through a Brahmanized Sanskrit medium, while I have adopted a Buddhistical Pali medium. With all my unfeigned predisposition to defer to your practised judgment and established reputation in oriental research, it would be uncandid in me if I did not avow, that I retain the opinion that the medium of analysis employed by me has been (imperfect as that analysis is) the more appropriate and legitimate one.

The thorough investigation of this subject is of such paramount importance and deep interest, and as (if I have rightly read the concluding sentence of "the fifth inscription round the shaft of Feroz's pillar," which appears for the first time in the July journal,) we have yet five* [We know of five, therefore three remain — the Bhittri may be a fragment of one; that at Bakrabad, and one near Ghazeepore are without inscriptions.— Ed. [J. Prinsep]] more similar columns to discover in India, I venture to suggest that you should publish my translation also, together with the text in the ancient character, transposed literatim from my romanized version. [To this we must demur: we have examined the greater part from perfect facsimiles, and cannot therefore consent to publish a version which we know to deviate materially from the original text.—ED. [J. Prinsep]] Future examiners of these monuments of antiquity will thus have the two versions to collate with the originals, and be able to decide which of the two admits of the closest approximation to the text.

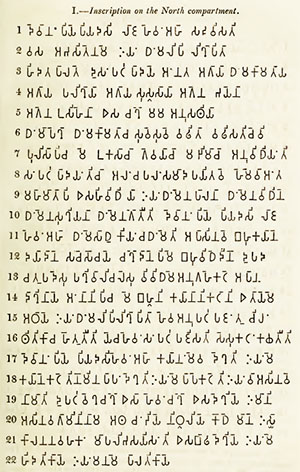

In the present note I shall confine myself to a critical examination of the first sentence only of the northern inscription, which will serve to show how rigidly I have designed to adhere to the rules of the Pali grammar in my translation of these inscriptions; and then proceed to explain the historical authority I have recently discovered for identifying Piyadasi, the recorder of these inscriptions, with Dhammasoko, the supreme monarch of India, the convert to, and great patron of, Buddhism, in the fourth century before our era.

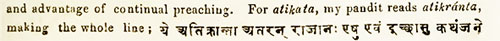

The first sentence of the northern inscription, after the name of the recorder and the specification of the year of his reign, I read thus:

Hidatapalite dusapatipadaye, ananta agaya dhanmakamataya, agaya parikhaya, agaya sasanaya, agena bhayena, agena usahena; esachakho mama anusathiya.

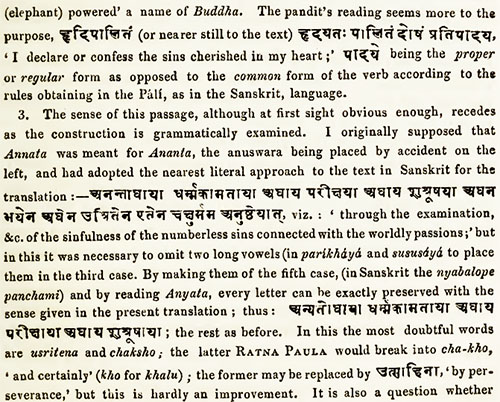

Although the orthography as well as syntax, of your reading, viz. hidatapalite dusan, and which you construe "the faults that have been cherished in my heart," are both defective, a slight and admissible alteration into "hadayapalite dose" would remove those objections, if other difficulties did not present themselves, which will be presently explained, and which, I fear, are insuperable.

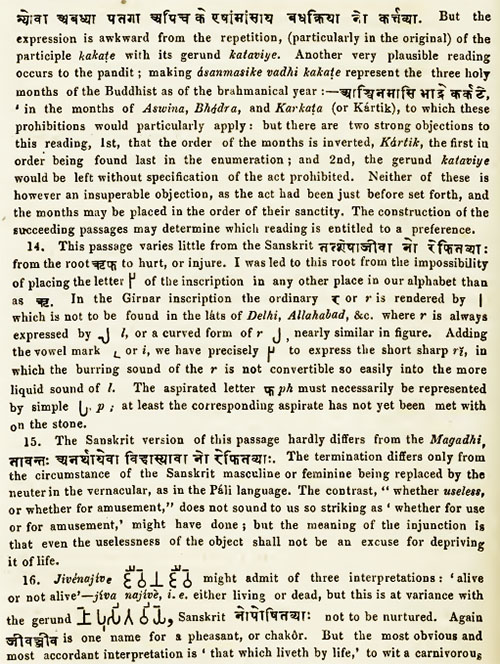

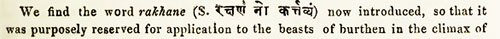

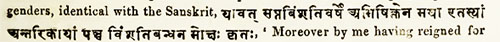

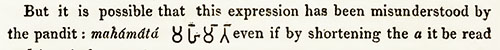

The substantive "patipadaye," [The objection to consider patipadaye as a verb does not seem very consistent with the three examples given, all of which are verbs — patipajjamati (the double jj of which represents the Sanskrit dy not d) S. pratipadyama iti or in atmani pada amahe; — and twice, patipajjitubanti (S. Pratipadyatavyam iti). Pada is certainly the root of all; which with the prefix pati (S. prati) takes the neuter sense of 'to follow after (or observe);' while by lengthening the a, pada, it has the active or causal sense of to make observance, to declare, ('padyate, he goes, padayati or padayate, he makes to go,) the only alteration I bespoke was palate to palatam, to agree with dosam — but as the anuswara is very doubtful in the Allahabad copy, I incline to read (Sanskritice hidayatapalatah dosahpatipadaye, 'I declare (what was) the sin cherished in my heart' — with a view of course to renunciation. The substitution of u for o has many examples: — but I never pretended that the reading of this passage was satisfactory. — Ed. [J. Prinsep]] however, which you convert into a verb, does not, I am confident, in the Pali language, admit of the rendering "I acknowledge and confess" in the sense of renunciation. This word is derived from the root "pada" to proceed in, as in a journey;" and with the intensitive prefix "pati" invariably signifies "steadfast observance or adherence." With the prefix of collective signification "sam" the verb signifies "to acquire" or "to earn." I gave an instance in the July journal (p. 523), as the last words uttered by Buddho on his deathbed.

"Handadane", bhikkhawe", amantiyami wo: wayadhamma sankhara, appamadena sampadetha."

"Now, O Bhikkhus! I am about to conjure you (for the last time): perishable things are transitory; without procrastination earn (nibbanan.")

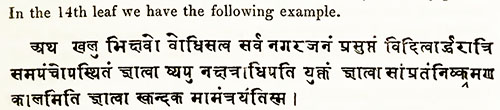

With the intensitive prefix 'pati,' the verb is to be found very frequently in the Buddhistical scriptures. The following example is also taken from the Parinibbanan sutan in the Dighanikayo, containing the discourses of Buddho delivered while reclining on his deathbed, under the sal trees at Kusinara. The interrogator Anando was his first cousin, and favorite disciple.

Kathan Mayan, Bhante, Matugame patipajjamati*? [By permutation d becomes jj, (rather dy. — Ed.) [J. Prinsep] Adassan, Anandati, Dassane, Bhagawa, kothan patipajjitabbanti? Analapo, Anandati, Alapantera, Bhante kathan patipajjitabbanti? Sati Ananda Upattha petabbati.

"Lord, how should we comfort ourselves in our intercourse with the fair sex? Anando! do not look at them. Bhagawa! having looked at them, what course should be pursued then? Anando! abstain from entering into conversation with them? In the course of (religious) communion (with them), Lord, what line of conduct ought to be observed? Under those circumstances, Anando! thou shouldst keep thyself guardedly composed."

It is evident, therefore, that the substantive "patipadaye" signifies "observance and adherence" and cannot be admitted to bear any signification which implies "renunciation."

It is almost immaterial whether the next word be the adjective "annata" or the adjective "ananta" — I prefer the latter. But "agaya," cannot possibly be the substantive "aghan" "sin," in the accusative case plural.

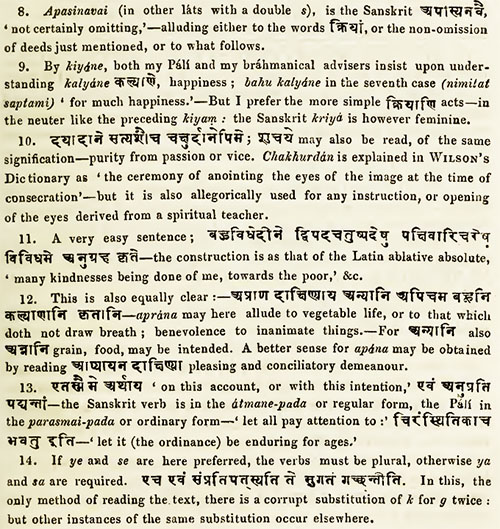

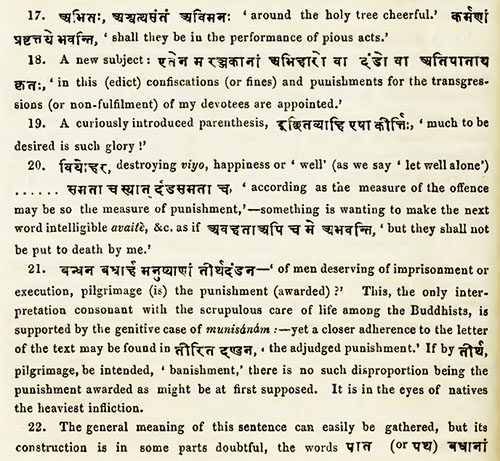

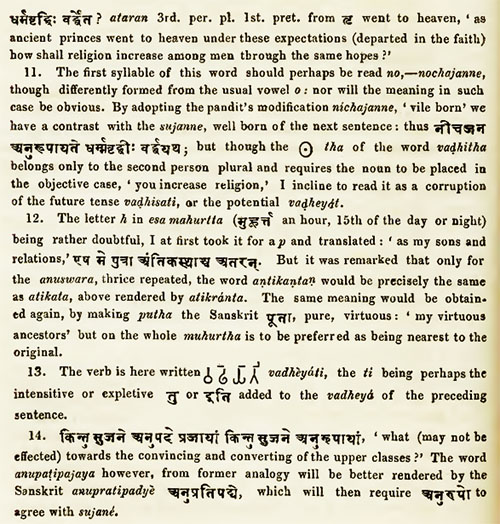

[Editor's FN:

My critic has here been misled by my looseness of translation— had he followed my Sanskrit, he would have seen that aghaya was never intended as an accusative plural of agham: I must parse and construe the whole, premising that the texts differ in regard to the final a of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th words, which in some copies of the Delhi inscription are long, while on the Allahabad facsimile they are all short. In the former case (the one I previously adopted) the reading is (Sanskritice.)adj. fem. s. 5.

Anyata-aghaya

subs. fem. s. 5.

dharmakamataya,

sub. nt. s. 4

aghaya,

sub. fem. s. 5.

parikshaya,

ditto

aghaya

ditto,

susrusaya

3rd case

aghena

sub. s. 3

bhayena,

sub. s. 3

aghena utsahena,

pro. 1

esa —

sub. s. 1

chakshuh,

pro. 6

mama

verb pot. s. 3.

anustheyat

"from the all-else-sinful religion-desire, from examination to sin, from desire to listen to sin (sc. to hear it preached of) by sin-fear, by sin-enormity, — thus may the eye of me be confirmed."

In this translation I have preserved every case as in the Sanskrit, and I think it will be found that the same meaning is expressed in my first translation.

If the short a be preferred, the 5th case, kamataya and parikshaya, both feminine substantives must be changed to the 3rd, Sans. kamatayai and parikshayai (in Pali, kamataya and parikhaya) — and the sense will be only changed to "by the all-else-sinful desire of religion, — by the scrutiny into the nature of sin, &c. That kamata (not kama) is the feminine noun employed (formed like devata from deva) is certain: because the nominative case is afterwards introduced 'dharma-preksha, dharma kamata cha, &c. Mr. Turnour converts these into plural personal nouns, "the observers of dharma, the delighters in dharma" — but such an interpretation is both inconsistent with the singular verb (varddhisati), and with the expression suve suve (svayam svayam) 'each of itself '— I therefore see no reason to give up any part of my interpretation of the opening sentence of the inscription. — Ed. [J. Prinsep]]

End FN]

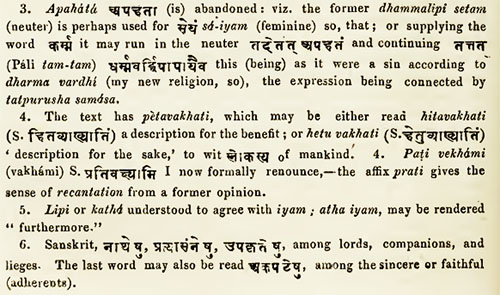

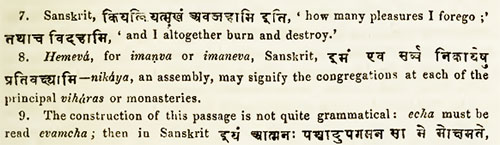

The absence of the aspirate would not be a serious objection, but "aghan*" [Aghan is said to be sometimes masculine, agho which makes aghe in the accusative plural. — Ed. [J. Prinsep]] is a neuter noun of the 12th declension. The accusative plural would be "agani or age" and not "agaya," which I read "agaya" the dative singular. In this sentence, this word occurs five times, varying in its inflections and gender to agree with the substantive with which it is connected in each instance; proving it therefore to be an adjective, and, I think, "aggo" "precious," which is here spelt with a single g in conformity with the principle on which all double consonants are represented by single ones in these inscriptions. "Dhanmakamataya" is a Samasa contraction of "dhammassa kamataya," and signifies "out of devotion to dhanmo" "kama" being a feminine noun of the seventh declension makes "kamataya" in the instrumental case, but "agaya-parikaya agaya sususaya," again though terminating in the same manner as kamataya, are in the dative case as sasusaya (which I read Sasanaya) is a neuter noun of the tenth, (?) declension; bhayena and usahena being, the one a neuter of the twelfth and the other a masculine noun of the first declension, both make their instrumental case in "ena." Without a precise knowledge of the Pali grammar, it is impossible to define when a case is dative and when instrumental. "Esachakho mama anusathiya," you translate, I find, "by these may my eyes be strengthened and confirmed (in rectitude)." The participial verb "anusathiya," could not, I imagine, be made to bear in Pali the signification you give it. The preposition "anu" signifies "following," "continuance," "in due order," when in composition with the root "sara" "to remember" (from which sathiya is derived), the compound term always means "to bear in remembrance" or "perpetuate the remembrance of." If there was any thing to be gained by preserving the "eyes" we might certainly with a trifling variation, read the passage "esa" chakhu mama anusathiya," hontu being understood, — "may my eyes perpetuate the remembrance of these (dhanma)." But I confess I prefer the reading of this passage as it appears in the inscription — "Esachakho mama anusathiya," — the verb "hessati" being understood, — and "esa" agreeing with "Dhanmalipi." "This (inscription on Dhanmo), moreover, will serve to perpetuate the remembrance of me." This rendering conveys a nobler sentiment, aspiring to more permanent fame, and is in close conformity also with the spirit of the last sentence in the fifth inscription.

I have still to dispose of the initial words "Hidatapalite dusan patipadayi." I acknowledge that I was at first entirely baffled by them. When I had completed the translation of all the four inscriptions, save these three words, I found that they were the edicts of an Indian monarch, a zealot in Buddhism? and from these columns being scattered over widely separated kingdoms of India, it appeared equally certain to me that a Rajadhiraja of India alone could be the author of them. As far as I was aware, two supreme monarchs alone of India had become converts to Buddhism, since the advent of Sakya. Dhanmasoko in the fourth century before Christ; and Pandu at the end of the third century of our era. I could hit upon no circumstance connected with the former ruler which availed me in interpreting these words. I then took up the Dhatadatuwanso, the history of the tooth relic, the only work, I believe, in Ceylon, which treats of Pandu. I there found, not only that his conversion had been brought about in consequence of the transfer of the tooth relic from Dantapura in the Northern Circars, then called Kalinga, to his capital Patilipura the modern Patna; but also met with several passages expressive of Pandu's sentiments strictly analagous with those contained in these inscriptions. This discovery, at the moment, entirely satisfied me, that these three hitherto undecipherable words should be read hi* [The alterations requisite to admit of that reading are trifling, and chiefly symbolic, in the ancient alphabet.] Dantapurato dasanan upadaye: the hi being an expletive of the preceding word, and the other words signifying "from Dantapura I have obtained the tooth relic."

Under this impression my former paper on these inscriptions was drawn up. My having subsequently ascertained that Piyadasi is Dhanmasoko does not necessarily vitiate this reading; for the tooth relic was at Dantapura during his reign also; and there is no reason why Dhanmasoko likewise should not have paid it the reverential honor of transferring it to his capital. But since I have read your translation, I have made out another solution of these words furnishing the signification you adopt, without incurring the apparent objections noticed above. The sentence written in extenso, divested of permutation of letters, and samasa contraction might be read; [This verb Hin is most frequently found in the participial form "hitwa."] Hin atana palite dusapatipadaye. "I have renounced the impious courses cherished by myself." "Hin" is derived from the root ha "to renounce," and is the Varassa form of the ajjatani tense. By the 35th rule of Clough's grammar, p. 13, when n precedes a vowel it is frequently suppressed, and m or d substituted in its place, as for "awan assa" is written "ewamassa" for "etan awocha," "etadawocha." By this rule, therefore, "Hin atana" would become "Hidatana." Again by the "Tapuriso" (Tatpurusya) rule (No. 19, p. 79) "atanapalite" would be contracted into "atapalite." The reading in extenso then becomes contracted into Hidatapalite." "Dosa'' from "du" signifies "impure or impious" and "patipadaye" as already explained are "observances or actions in life." My reading therefore of the entire sentence is now "I have renounced the impious observances cherished by myself — out of innumerable and inestimable motives of devotion to Dhanmo, and out of reverential awe and devout zeal for the precious religion which confers inestimable protection. This (inscription on Dhanmo), moreover, will serve to perpetuate the remembrance of me."

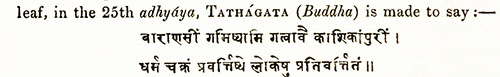

I proceed now to give my authority for pronouncing Piyadasi to be Dhanmasoko.

From a very early period, extending back certainly to 800 years, frequent religious missions have been mutually sent to each other's courts, by the monarchs of Ceylon and Siam, on which occasions an exchange of the Pali literature extant in either country appears to have taken place. In the several Solean and Pandian conquests of this island, the literary annals of Ceylon were extensively and intentionally destroyed. The savage Rajasingha in particular, who reigned between A.D. 1581 and 1592, and became a convert from the Buddhistical to the Brahmanical faith, industriously sought out every Buddhistical work he could find, and "delighted in burning them in heaps as high as a cocoanut tree." These losses were in great measure repaired by the embassy to Siam of Wilbagadere Mudiyanse, in the reign of Kirtisri Rajasingha in A.D. 1753, when he brought back Burmese versions of most of the Pali sacred books, a list of which is now lodged in the Dalada temple in Kandy.

The last mission of this character, undertaken however without any royal or official authority, was conducted by the chief priest of the Challia or cinnamon caste of the maritime provinces, then called Kapagama thero. He returned in 1812 with a valuable library, comprising also some historical and philological works. Some time after his return, under the instructions of the late Archdeacon of Ceylon, the Honorable Doctor Twisleton, and of the late Rev. G. Bisset, then senior colonial chaplain, Kapagama became a Convert to Christianity, and at his baptism assumed the name of George Nadoris de Silva, and he is now a modliar or chief of the cinnamon department at Colombo. He resigned his library to his senior pupil, who is the present chief priest of the Challias, and these books are chiefly kept at the wihare at Dadala near Galle. This conversion appears to have produced no estrangement or diminution of regard between the parties. It is from George Nadoris, modliar, that I received the Burmese version of the Tika of the Mahawanso, which enabled me to rectify extensive imperfections in the copy previously obtained from the ancient temple at Mulgirigalla, near Tangalle.

In the Journal of December last, I have mentioned the circumstances under which I obtained possession of a Pali copy of the Dipawanso, in a very imperfect state, written in the Burmese character.

-- An Analysis of the Dipawanso: An examination of the Pali Buddhistical Annals, No. 4, by the Honorable George Turnour, Esq., Ceylon Civil Service, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, November, 1838 (p. 930).

Some time ago the modliar suggested to me that I was wrong in supposing the Mahawanso and the Dipawanso to be the same work, as he thought he had brought the Dipawanso himself from Burmah. I was sceptical. In my last visit, however, to Colombo, he produced the book, with an air of triumph. His triumph could not exceed my delight when I found the work commenced with these lines quoted by the author of the Mahawanso* [Vide in the quarto edition the introduction to the Mahawanso, page xxxi.] as taken from the Mahawanso (another name for Dipawanso) compiled by the priests of the Utaru wihare at Anuradhapura, the ancient capital of Ceylon. "I will perspicuously set forth the visits of Buddho to Ceylon; the histories of the convocations and of the schisms of the theros; the introduction of the religion (of Buddho) into the island; and the settlement and pedigree of the sovereign Wijayo."

In cursorily running over the book, at the opening of the sixth Bhanawaro or chapter, which should contain the history of Dhammasoko, I found the lines quoted from my note to you in page 791.

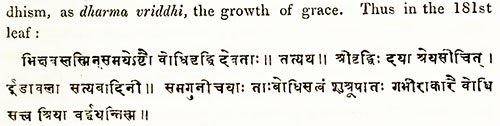

This Dipawanso extends to the end of the reign of Mahasino, which closed in A.D. 302. As the Mahawanso, which quotes from this work, was compiled between A.D. 459 and 477, the Dipawanso must have been written between those two epochs. I have only cursorily run over the early chapters to the period where the Indian history terminates without collecting from that perusal any new matter, not found embodied either in the Mahawanso or its Tika [commentary], excepting the valuable information above mentioned, and a series of dates defining the particular year of each sovereign's reign, in which the several hierarchs of the Buddhistical church died, down to Moggaliputtatisso the chief priest who presided at the third convocation in the reign of Dhammasoko. These dates may remove some of the incongruities touched upon in my second paper on Buddhistical annals.

This Burmese copy, however, of the Dipawanso is very imperfect. Each Bhanawaro ought to contain 250 verses. Several chapters fall short of this complement; and, in some, the same passage is repeated two and even three times.

It will be highly desirable to procure, if possible, a more perfect copy, together with its commentary, (either Tika or Atthakatha) from the Burmese empire.

On my return to Kandy, and production of the Dipawanso to the Buddhist priests, who are my coadjutors in these researches, they reminded me that there was a Pali work on my own shelves, which also gave to Dhanmasoko, the appellation of Piyadaso. The work is chiefly in prose, and held in great estimation for the elegance of its style: hence called "Rasawahini" — "sweetly flowing" or the "harmonious stream."

The Singhalese version, of which this Pali work is a translation, was of great antiquity, and is no longer extant. The present copies in that language are merely translations of this Pali edition. I am not able to fix the date of this Pali version, as the author does not give the name of the sovereign in whose reign he flourished — but the period is certainly subsequent to A.D. 477, as he quotes frequently from the Mahawanso. The author only states, that this work is compiled by Koratthapalo, the pious and virtuous incumbent of the Tanguttawankapariweno attached to the Mahawiharo (at Anuradhapura); and that he translates it from an ancient Singhalese work, avoiding only the defects of tautology and its want of perspicuity.

In one of the narratives of this book, containing the history of Dhanmasoko, of Asandhimitta his first consort after his accession to the Indian empire, of his nephew Nigrodho, by whom he was converted to Buddhism, and of his contemporary and ally Dewananpiyatisso, the sovereign of Ceylon, — Dhanmasoko is more than once called Piyadaso, viz.:

"Madhudayako pana wanijo Dewalokato chawitwa, Pupphapure rajakule uppajitwa Piyadaso kumaro hutwa chhattan ussapetwa sakala-jambadipa eka-rajjan akasi*." [Vide page 24 of the Mahawanso for an explanation of this passage.]

"The honey-dealer who was the donor thereof (to the Pache Buddho) descending by his demise from the Dewaloko heavens; being born in the royal dynasty at Pupphapura (or Patilipura, Patna); becoming the prince Piyadaso and raising the chhatta, [Parasol of dominion.] established his undivided sovereignty over the whole of Jambudipo'' — and again —

"Anagate Piyadaso, nama kumaro chhattan ussapetwa Asoka nama Dhanma Raja bhawissati."

"Hereafter the prince Piyadaso having raised the chhatta, will assume the title of Asoka the Dhanma Raja, or righteous monarch."

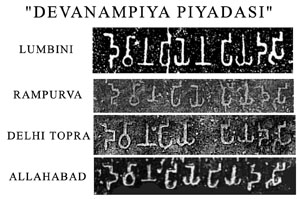

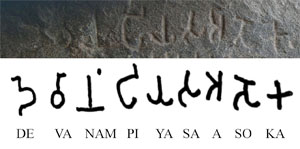

It would be unreasonable to multiply quotations which I could readily do, for pronouncing that Piyadaso, Piyadasino [Piyadassino is the genitive case of Piyadasi, [x]: — Ed. [J. Prinsep]] or Piyadasi, according as metrical exigencies required the appellation to be written, was the name of Dhanmasoko before he usurped the Indian empire; and it is of this monarch that the amplest details are found in Pali annals. The 5th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th chapters of the Mahawanso contain exclusively the history of this celebrated ruler, and there are occasional notices of him in the Tika of that work, which also I have touched upon in my introduction to that publication. He occupies also a conspicuous place in my article No. 2, on Buddhistical annals. His history may be thus summed up.

He was the grandson of Chandagutto (Sandracottus) and son of Bindusaro who had a numerous progeny, the issue of no less than sixteen consorts. Dhanmasoko, who had but one uterine brother, named Tisso, appears to have been of a turbulent and ambitious character; Bindusaro consigned him to an honorable banishment by conferring on him the government of Ujjeni (Oujein)* [Introduction to the Mahawanso, p. xlii.] "in his apprehension arising from a rumour which had prevailed that he (Asoko) would murder his own father; and being therefore desirous of employing him at a distance, established him at Ujjeni, conferring the government of that kingdom on him."

While administering that government he formed a connection with Chetiya Dewi a princess of Chetiyagiri, and had by her a son and daughter, Mahindo and Sanghamitta, who followed their father to Patilipura, subsequently entered into the sacerdotal order, and were the missionaries who converted Ceylon to Buddhism. Chetiya Dewi herself returned to her native city. On his death-bed, Bindusaro sent a "letter" recalling him to his capital, Patilipura. He hastened thither, and as soon as his parent expired, put all his brothers, excepting Tisso, to death, and usurped the empire. He raised Tisso to the dignity of Uparaja, — which would appear to be the recognition of the succession to the throne.

In the 4th year after his accession, being the year of Buddho 218, and before Christ 325, [The second paper on "Buddhistical Annals" notices the discrepancy of about 60 years between this date, and that deduced from the date of European classical authors connected with Alexander's invasion.] he was inaugurated, or anointed king. In the 3rd year of his inauguration, he was converted to Buddhism by the priest Nigrodho the son of his eldest murdered brother, Sumano. In the 4th year Tisso resigned his succession to the empire, and became a priest. In the 6th, Mahindo and Sanghamitta also entered into the sacerdotal order. In the 17th the third convocation was held, and missionaries were dispatched all over Asia to propagate Buddhism. In the 18th, Mahindo arrived in Ceylon, and effected the conversion of the Ceylonese monarch Dewananpiyatisso and the inhabitants of this island. In the same year Sanghamitta, the bo-tree and relics were sent by him to Ceylon. In the 30th, his first consort espoused after his accession, Asandhimitta, who was zealously devoted to Buddhism, died; and three years thereafter he married his second wife. He reigned 37 years.

The five short insulated lines at the foot of the Allahabad pillar, having reference to this second empress, is, by its position in the column, a signal evidence of the authenticity, and mutual corroboration of these inscriptions and the Pali annals. As Dhanmasoko married her in the 34th year of his reign, she could not have been noticed in the body of the inscriptions which were recorded on the 27th. I fear we do not yet possess a correct transcript of these five lines*. [See page 966 which had not reached the author when the above was written. — Ed. [J. Prinsep]]

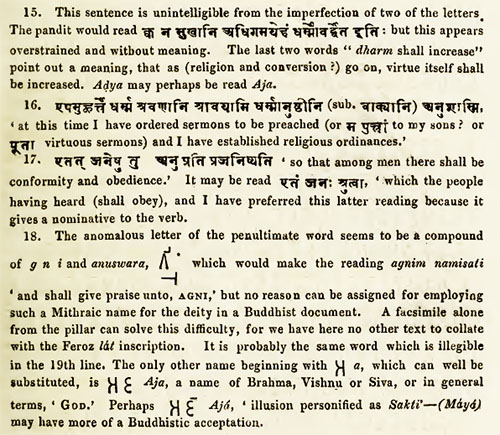

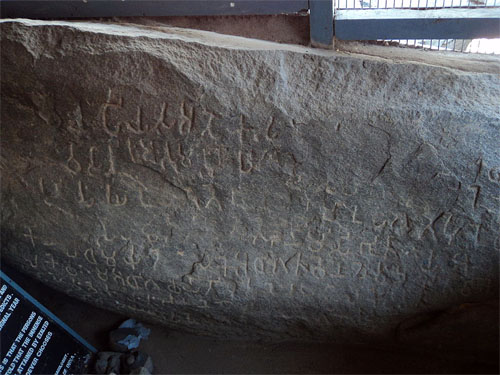

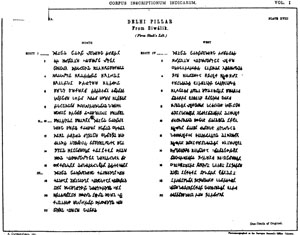

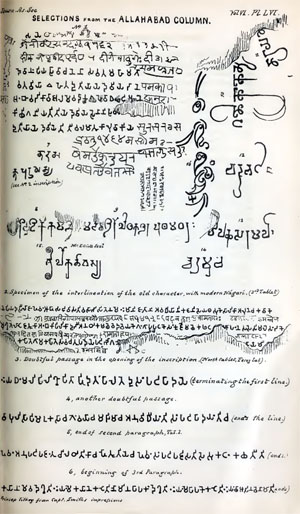

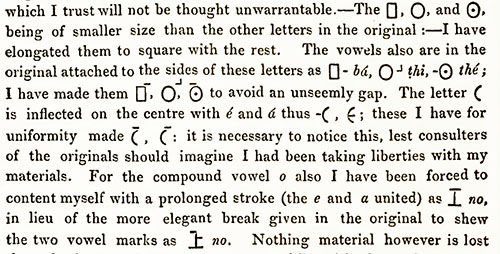

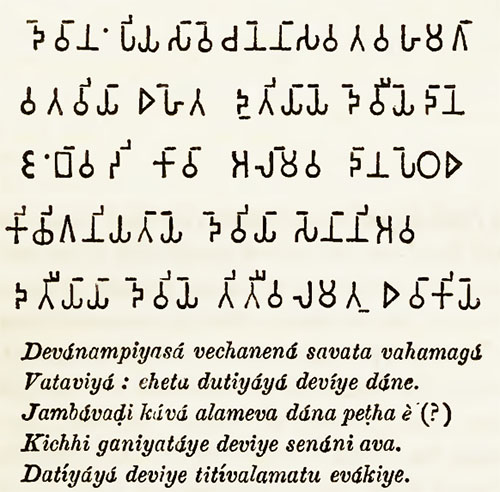

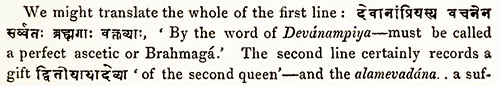

The five short lines in the old character that follow the Dharmalipi at a short distance below (see Capt. Burt's lithograph) were the next object of my inspection, I have represented what remains of them faithfully in fig. 1, of PI. LVI. which will be seen to differ considerably from Lieut. Burt's copy of the same. The reading is now complete and satisfactory in lines 1, 2, and 5. The 3rd and 4th lines are slightly effaced on the right hand. We can also now construe them intelligibly, though in truth the subject seems of a trivial nature to be so gravely set forth.Devanampiyasa vachanena savata mahamata

Vataviya: Eheta dutiyaye deviye rane

Ambavadika va alameva danam: Ehevapati. . .

Kichhiganiya titiye deviye senani sava. . .

Dutiyaye deviyeti ti valamatu karuvakiye

'By the mandate of Devanampiya, at all times the great truth (Mahamata* [See page 574. In Sanskrit [x] (or perhaps rather [x] by his desiring, wishing) [x] (fit or proper to be said,) meaning perhaps that this object had been provided for by pecuniary endowment.]) is appointed to be spoken. These also, (namely) mango-trees and other things are the gift of the second princess (his) queen. [[x].] And these for. . . of Kichhigani the third princess, the general (daughter's . . . ?) Of the second lady thus let the act redound with triple force [[x], corresponding as nearly as the construction of the two languages will allow.].

Unable to complete the sentence regarding the third queen, it is impossible to guess why the second was to enjoy so engrossing a share of the credit of their joint munificence, unless she did the whole in the name and on the behalf of them all! — It will be interesting to inquire whether by any good chance the name of queen Kichhigani is to be found in the preserved records of Asoka's reign, which are so circumstantial in many particulars. It is evident the Buddhist monarch enjoyed a plurality of wives after his conversion, and that they shared in his religious zeal.THE QUEEN’S EDICT AT ALLAHABAD.

Prinsep, p. 966 and ff.

TEXT.

1 Dêvânampiyasa vachanêna savata mahâmatâ

2 vataviyâ [ . ] ê hêta dutîyâyê dêviye dâ[?]nê

3 ambâvadikâ vâ âlamê va dâna ê hêvâ êtasi amnê

4 kichhi ganîyati tâyê dêviyê sê nâni sava

5 dutiyâyê dêviyê ti tîvalamâta kâluvâniyê

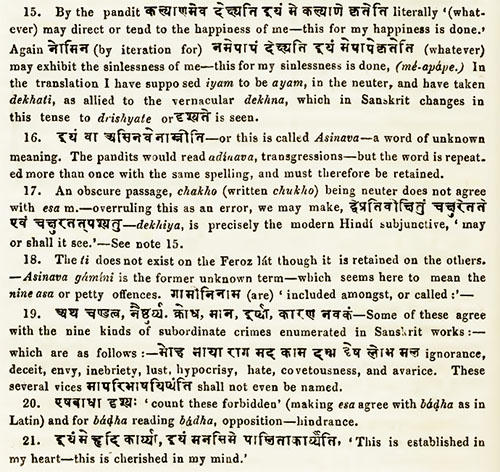

NOTES.

Although General Cunningham does not express himself on this point with all the clearness which one would desire, it appears to me to be certain, as Prinsep practically admitted, that these five lines preserve for us the commencement only of an inscription which the detrition of the stone interrupts from the sixth line. Has this detrition made itself felt in the fifth line? We shall at least see that, according to my opinion, and so far as one can judge from a single portion of a sentence, the reading of the last few words require much more correction than the rest of the fragment. On the other hand, I see no necessity for assuming that the lines which have come down to us are themselves incomplete, as Prinsep supposed with regard to the fourth. In any case, there can be no hope here of a really certain translation, but there are at least some details which can be rectified with confidence, and the Queen Kichhigani, for example, re-enters into that non-existence, from which she should never have emerged....

TRANSLATION.

Here followeth the order directed by command of the [king] dear unto the Devas to the Mahâmâtras of all localities: — For every gift made by the second queen, a gift of a mango-orchard, of a garden, as well as of every article of value found therein, [it is right to do honour] to the queen, whose religious zeal and charitable spirit will be recognised, while one says, — ‘all this comes from the second queen * * *.

-- The inscriptions of Piyadasi: The Columnar Edicts; The Separate Edicts; The Author and Languages of the Edicts, by Emile Senart, Translated by G.A. Grierson, B.C.S., and revised by the author, 1892

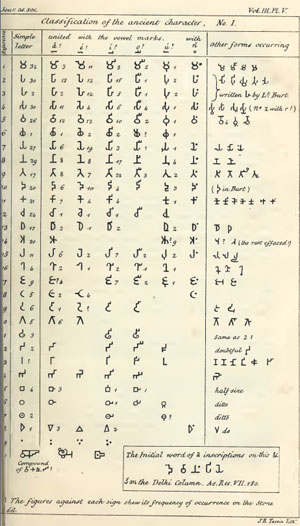

As for the interlineation, it may be dismissed with a very few words. Instead of being a paraphrase or translation of the ancient text as from its situation had been conjectured, it is merely a series of unconnected scribblings of various dates, cut in most likely by the attendants on the pillar as a pretext for exacting a few rupees from visitors,—and while it was in a recumbent position. In the specimen of a line or two in plate LVI. the date Samvat 1413 is seen along with the names of Gopala putra, Dhanara Singh and others undecipherable. In plate LV. also may be seen a Bengali name with Nagari date 1464 and a bottle-looking symbol; and another below [x] Samvat 1661 Dhamaraja. These may be taken as samples of the rest which it would be quite waste of time to examine.

It is a singular fact that the periods at which the pillar has been overthrown can be thus determined with nearly as much certainty from this desultory writing, as can the epochs of its being re-erected from the more formal inscriptions recording the latter event. Thus, that it was overthrown, sometime after its first erection as a Silasthambha or religious monument by order of the great Asoka in the third century before Christ, is proved by the longitudinal or random insertion of several names (of visitors ?) in a character intermediate between No. 1. and No. 2. in which the m, b, &c. retain the old form, as in the Gujerat grants dated in the third century of the Samvat. Of these I have selected all I can find on the pillar:—they are easily read as far as they go. Thus No. 7, under the old inscription in Plate LVI. is [x] narasa. It was read as Baku tate in the former copy. No. 8 is nearly effaced: No. 9 may be Malavadi ro lithakandar (?) prathama dharah. The first depositor of something ? No. 10, is a name of little repute: [x] ganikakasya, 'of the patron of harlots.' No. 11 is clearly [x] Narayana. No. 12,[x] Chandra Bhat. No. 13 appears to be halachha seramal. And No. 14 is not legible though decidedly in the same type.

Now it would have been exceedingly inconvenient if not impossible to have cut the name, No. 10, up and down at right angles to the other writing while the pillar was erect, to say nothing of the place being out of reach, unless a scaffold were erected on purpose, which would hardly be the case since the object of an ambitious visitor would be defeated by placing his name out of sight and in an unreadable position.

This epoch seems to have been prolific of such brief records: it had become the fashion apparently to use seals and mottos; for almost all (certainly all the most perfect) yet discovered have legends in this very character. One in possession of Mr. B. Elliott of Patna, has the legend lithographed as fig. 15, which may be read [x] Sri Lokanavasya, quasi 'the boatman of the world.' General Ventura has also brought down with him some beautiful specimens of seals of the same age, which I shall take an early opportunity of engraving and describing.

Selections From the Allahabad Column

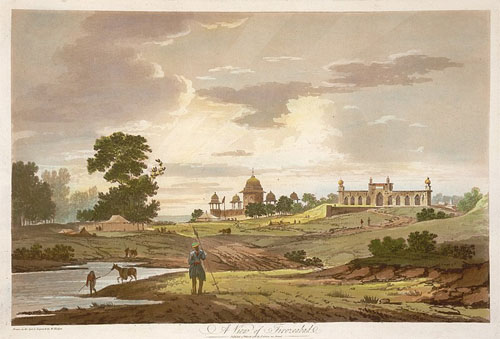

But to return from this digression. The pillar was re-erected as 'Samudra gupta's arm' in the fourth or fifth century, and there it probably remained until overthrown again by the idol-breaking zeal of the Musalmans: for we find no writings on it of the Pala or Sarnath type, (i.e. the tenth century), but a quantity appear with plain legible dates from the Samvat year 1420, (A.D. 1363) down to 1660, odd: and it is remarkable that these occupy one side of the shaft, or that which was uppermost when the pillar was in a prostrate position. There it lay, then, until the death of the Emperor Akber; immediately after which it was once more set up to commemorate the accession (and the genealogical descent) of his son Jehangir.

A few detached and ill executed Nagari names, with Samvat dates of 1800, odd, shew that even since it was laid on the ground again by general Garstin, the passion for recording visits of piety or curiosity has been at work, and will only end with the approaching re-establishment of the pillar in its perpendicular pride under the auspices of the British government.

-- VII. Note on the Facsimiles of the various Inscriptions on the ancient column at Allahabad, retaken by Captain Edward Smith, Engineers, by James Prinsep, Sec. As. Soc. &c. &c., The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. VI, Part II, July to December, 1837.

The passage in the Mahawanso which refers to this queen is curious, and may hereafter assist the correct translation of these five lines. I therefore insert it.

1 Attharasahi wassamhi Dhammasokassa Rajino Mahamegha-wanarame mahabodhi patitthahi.

2 Tato dwadasame wasse mahesi tassa rajino piya Asandhimitta sa mata Sambuddhamamika.

3 Tato chatutthawassamhi, Dhammasoko mahipati tassarakkhan mahesitte thapesi wosama sayan,

4 Tatotu totiye wasse sabalarupamanini "mayapicha ayan raja mahabodhin mamayati,"

5 Iti kodhawasan gantwa, attanotattha karika mandukantakayogena mahabodhimaghatayi.

6 Tato chatutthe wassamhi Dhammasoko mahayaso anichchatawasampatto: sattatinsosama ima.

"In the eighteenth year of the reign of Dhammasoko, the bo-tree was planted in the Mahamegawano's pleasure garden, (at Anuradhapura). In the twelfth year from that period, the beloved wife of that monarch, Asandhimitta, who had identified herself with the faith of Buddho, died. In the fourth year (from her demise), the raja Dhammasoko, under the influence of carnal passions, raised to the dignity of queen consort, an attendant of her's (his former wife's). In the third year from that date, this malicious and vain creature who thought only of the charms of her own person, saying, "this king, neglecting me, lavishes his devotion exclusively on the bo-tree," — in her rage (attempted to) destroy the great bo with the poisoned fang of a toad. In the fourth year from that occurrence, this highly gifted monarch, Dhammasoko, fulfilled the lot of mortality. These years collectively amount to thirty-seven."

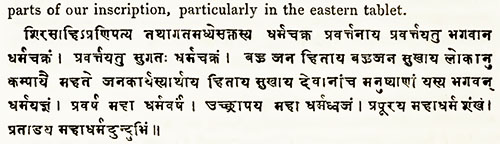

I have not had time to examine the fifth inscription round the Delhi column carefully, and I apprehend that the transcript is not altogether perfect yet. The last line and half of this inscription, I should be disposed to read thus:

"Etan Dawananpiya aha; iyan dhanmalibi ata ahasilathambani, Wisalittha-lekhaniwa tata kantawiya: ena esa chirathikasiya." In the Pali considered the most classical in Ceylon, the sentence would be written as follows: Etan Dewananpiya aha: iyan dhanmalipi atha atthasilathambani Wesalittha-lekhaniwa tatha (tatha) kata; tena esa chiratthitika siya.

"Dewananpiya delivered this (injunction). Thereafter eight stone columns have been erected in different quarters like the inscriptions on Dhanmo established at Wesali. By this means this (inscription) will be perpetuated forever."

If this reading be correct*, [This reading involves so many alterations of the text that I must demur to it, especially as on re-examination I find it possible to improve my own reading so as to render it (in my own opinion at least) quite unobjectionable. The correction I allude to is in the reading of atha, which from the greater experience I have now gained of the equivalents of particular letters, I am inclined to read as the Sanskrit verb astat (Pial atha). — The whole sentence Sanskritized will be found to differ in nothing from the Pali — except in that stambha is masculine in the former and neuter in the latter: — and that the verb kataviya is required to agree with it. Iyam dharmalipi ata astat, sila-stambha (ni)va siladharika(ni)va tatah kartaviya (ni), ena (or yena) esha chirasthiti syat. "In order that this religious edict may stand (remain), stone pillars and stone slabs (or receptacles) shall be accordingly prepared;— by which the same may endure unto remote ages." Atha might certainly be read as ashto eight, but the construction of the sentence is thereby much impaired, and further it is unlikely that any definite number should be fixed upon, without a parallel specification of the places where they should be erected. — Ed. [J. Prinsep]] as I have said before, we have still five more of these columns to discover in India.

I would wish to notice here that there are several errata in the Pali quotations in the July journal occasioned, probably, by the indistinction of the writing of my copyist. I mention this merely to prevent Pali scholars from inferring that those errata are peculiarities in the orthography of that language as known in Ceylon. For instance in page 586, you quote me as translating Viyodhanma "perishable things," whereas the words ought to have been "Waya-dhanma."

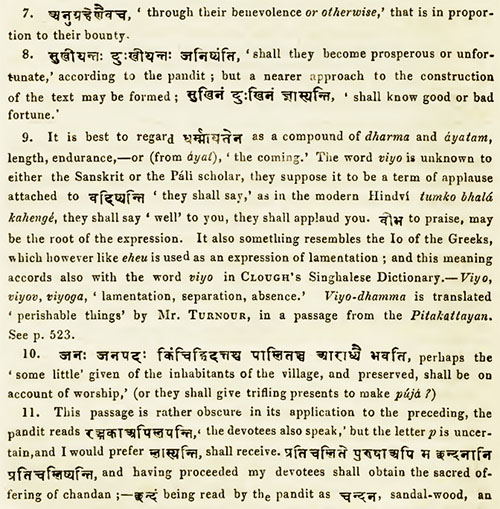

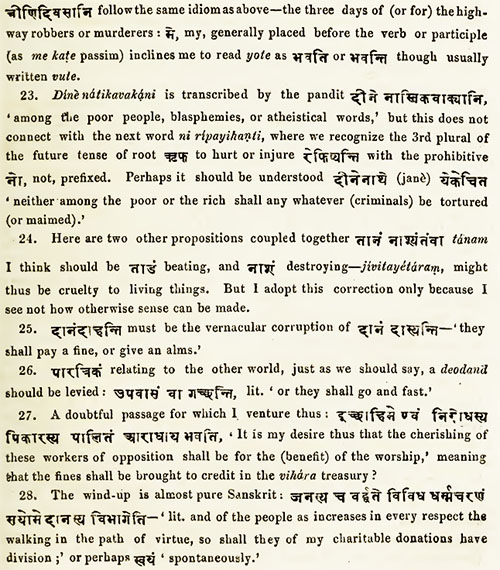

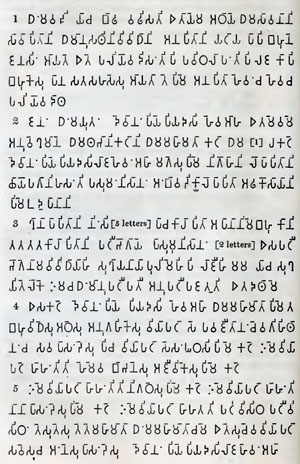

The inscription fronting north (as corrected by Mr. Turnour.)

1. Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewanaha Sattawisati

2. wasa abhisitena me iyan danmalipi likhapita-

3. hi. Dantapurato Dasanan upadayin, ananta agaya danmakamataya

4. agayaparikhaya, agayasasanaya, agena bhayena,

5. agenanusahena; esachakho mama amisathiya.

6. Dhanmapekha, dhanmakamatacha, suwe suwe, wadhita. wadhisantichewa.

7. Purisapicha me, rakusacha, gawayacha matimacha anuwidhiyantu

8. sanpatipadayantucha, aparanchaparancha samadayitwa hemewa anta

9. mahamatapi. E'sahiwidhi ya iyan, dhanmena palita, dhanmena widhins

10. dhanmena sikhayata, dhanmena galili." Dewananpiya Pandu so raja

11. hewan aha: "Dhanmo sadhukiyancha dhanmeti. Apasananwa bahukan yani

12. dayadani sache sochaye chakhudanepi me bahuwidhadinno? Dipada-

13. chatupadesa pariwaracharesu wiwidheme anugahe kate; A pane

14. dakhineye ananipicha me bahuni kayanani katani. Etaya me

15. athaya iyan dhanmalipi likhapita hewan anupatipajatu; chiran

16. thitakache hotiti. Yocha hewan sanpatipajisati, sesakatan karontiti!"

17. Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewan aha: "'Kayananmewa dakhati iyan me

18. 'kayanokatoti' no papan dakhati: iyan me 'papokatoti' iyanwa 'adinawa'

19. namati. Dupachawekhochakho esa, ewanchakho esa dakhiye; ima na

20. adinawagamininama. Athacha dine, nithuliye, kodhamane, isu-

21. ke, lenanawhake, maralabhasayase, esabadhadikha, iyan me-

22. pi dinakaye, iyan manan me paratikaye.

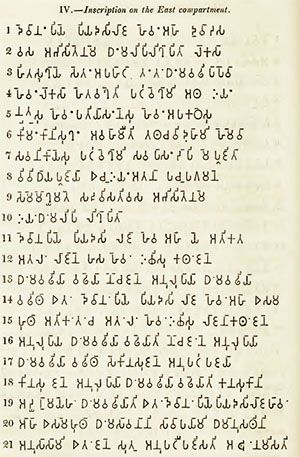

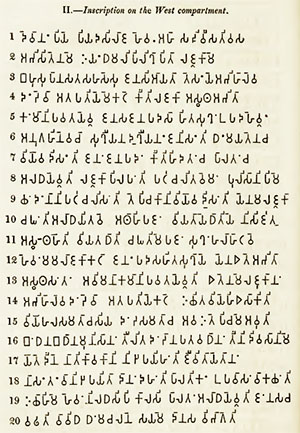

The inscription fronting East.

1. Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewan aha. "Sattawisati

2. wasa abhisitena me iyan dhanmalipi likhapita. Lokasa

3. hitasukhaya satan apahatatta dhanmawudhi. Papowa

4. hewan lokasa hitan wakhati. Pachawekhama athan iyan.

5. Nitesu hewan patiya santesu, hewan apikathesu,

6. kamakani sukha awhamiti. Tathachewan dahami hemewa-

7. sewanikayesu pachuwekhami. Sewa Pasandhapi me pujanti

8. wiwidhaya pujaya. Ichin iyan atana pachupagamane

9. samamokhiyamate. Sattawisati wasa abhisitena me

10. iyan dhanmalipi likhapita."

11. Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewan aha. "Yo atikanta-

12. antare rajane posehewa irisa kathan jane.

13. Dhanmawadhiye wadheya; nocha jane anurupaya dhanmawadhiya

14. wadhitha" Etan Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewan aha. "Esama-

15. puthan atikantecha antare hewan irisa rajane, kathan jane?

16. anurupaya dhanmawadhiya wadhayeti? Rochojano anurupaya

17. dhanmawadhiya wadhetha sekinapujane anupatipajaye.

18. Karasujana anurupaya dhanmawadhiya, wadhiyanti; kanasukani

19. atthamayehi ramawadhiyanti. Etan Dewananpiya Pandu so hewan

20. aha "esame" puthan dhanmasewanena sewaye. Me dhanmanusatane

21. anusesemi. Etan jana sutan anupattipajipata achan namasata."

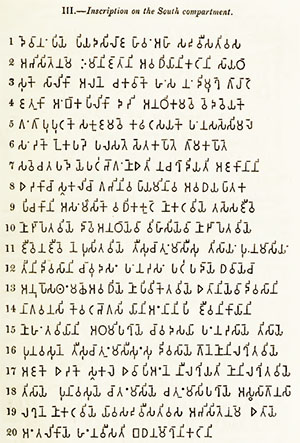

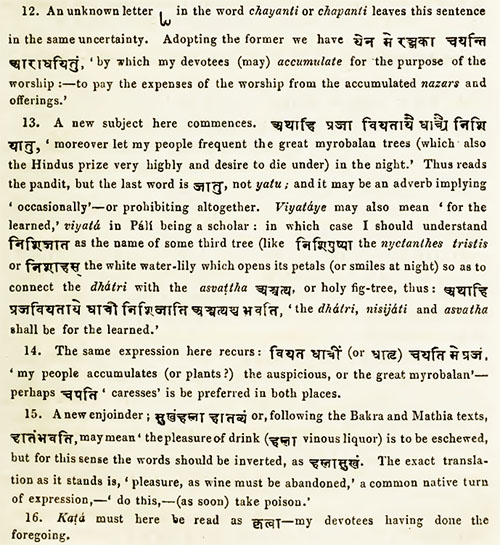

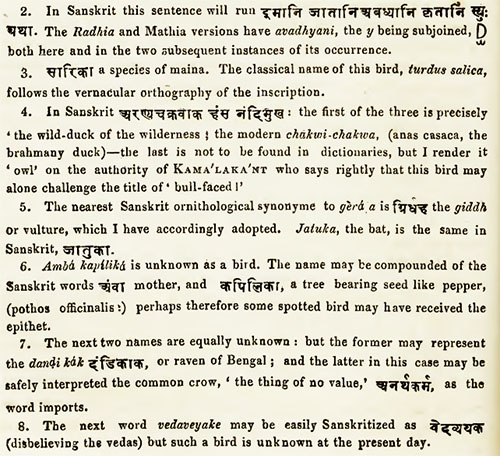

The Inscription fronting South.

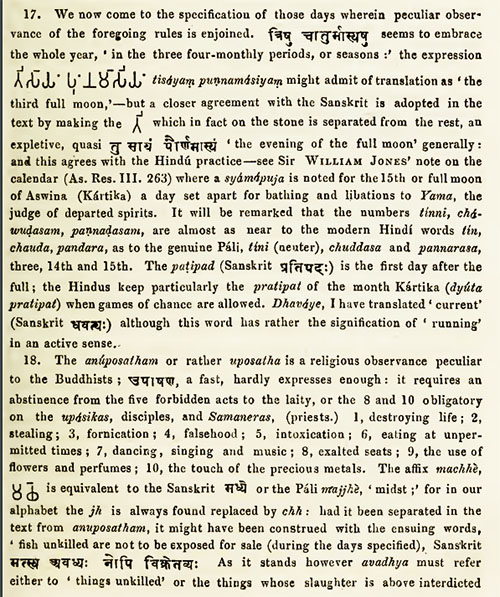

1. Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewan aha. "Sattawisati wasa

2. abbisitena me, imani satani awadhiyani kathani-seyatha-

3. suke, sirika, arane, chakawake, hansa, nandimukha, gorathe,

4. jatuka, aba, kapareka, datti, anthikamawe, wedaweyaka,

5. gangapuputhaka, sankajamawe, kadhathasagaka, panarase, simare,

6. sandike, rokapada, parasate, setskapote, gamakapote,

7. save, chatupade, yepi; luddagano ete nachakkadiyatu.

8. Elakacha, sukarecha, gabbaniwapayiminawa, awadhiyapentu ke-

9. pichakena; ansamansike wadhikakathe no kathawiye: tase sajiwe

10. nottipatawiye: dawe anatayewa wihasiyewa, nottipatawiye,

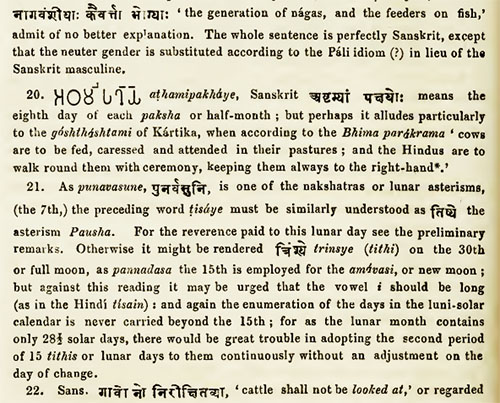

11. jiwenajiwene positawiye. Tisu chatumasisu tisayan punamasiyan,

12. tinidiwasani, chuddasan, pannarasan patipadiye, dhuweyecha

13. Anuposatte, mare awadhiye nopi, wiketawiye. Etaniyewa diwasani

14. nagawanepi, kwatha, dugasiani, annanipi jiwanikayani

15. no hantawiyani. Atthamipakhaye, chawudasiye panarasiye tasaye

16. punawasane tisu chatumasisu, sudiwasaye, gonanuna rakhitawiye

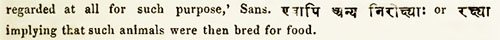

17. ajake, elake, sukare ewanpi anne nirakhiyatane, nirakhitawiye.

18. Tisaye punawasaye chatumasiye chatumasapakhaye apawasa gonasan-

19. rakhate no kathawiye. Yawa sattawisati wasa abhisitena me, etaye

20. antarikaye pana wisati bandhanamokhani katani."

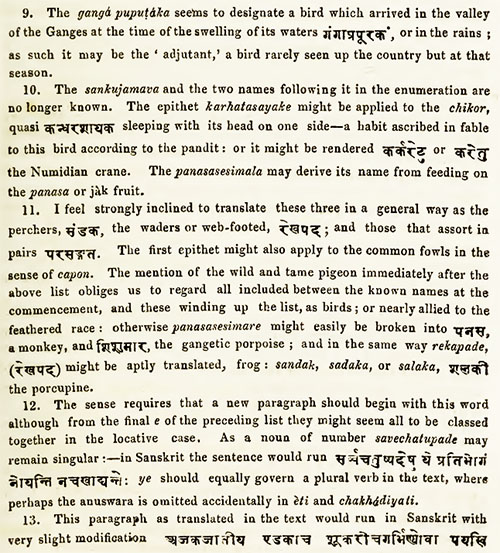

The Inscription fronting West.

1. Dewananpiya Pandu so raja hewan aha. "Sattawisati wasa

2. abhisitena me, iyan dhanmalipi likhapita. Rajjaka me

3. bahusu panasatasahasesu janesuayanti. Tesan yo abhipare

4. dandawe atapati, ye me kathi kin? Te rajjaka aswata abhita

5. kinmani, pawatayewun janasa janapadasa hitasukan rupadahewun;

6. anugahenewacha, sukhiyana dukhiyana janisanti; dhanmaya te nacha-

7. wiyewa disanti janan janapadan. Kin tehi attancha paratancha

8. aradhayewun? Te rajjaka parusata patacharitawe man purisanipime

9. * [The letter chh is read as r throughout; and the letter u as ru.— Ed. [J. Prinsep]] rodhanani paticharisanti; tepi chakkena wiyowadisanti ye na me rajjaka

10. charanta arundhayitawe, athahi pajanwiya taye dhatiya nisijita;

11. aswatheratiwiya ta dhati, charanta me pajan sukhan parihathawe.

12. Hewan mama rajjaka kate, janapadasa pitasukhaye; yena ete abhita

13. aswatha satan awamana, kamani pawateyewuti. Etena me rajjakanan

14. abhikarawadandawe atapatiye katke, iritawyehi esakiti

15. wiyoharasamuticha siya. Dandasamatacha, awaitepicha, me awute,

16. bandhana budhanan manusanan tiritadandinan patawadhanan,tinidiwasani, me

17. Yutte dinne, nitikarikani niripayihantu, Jiwitaye tanan

18. nasantanwa niripayantu: danan dahantu: pahitakan rupawapanwa karontu.

19. Irichime hewan nira dhasipi karipiparatan aradhayewapi: janasacha

20. wadhati: wiwidhadanmacharane; sayame danasan wibhagoti." [By comparing this version with that published in July, it will be seen to what extent the license of altering letters has been exercised. The author has however since relinquished the change of the Raja's name, in consequence of his happy discovery of Piyadasi's identity.— Ed. [J. Prinsep]]

Translation of the Inscription fronting North.

The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus said.

"This inscription on Dhanmo is recorded by me who have attained the twenty-seventh year of my inauguration. From Dantapura, I have obtained the tooth (relic of Buddho), out of innumerable and inestimable motives of devotion to Dhanmo, — with the reverential awe, and devout zeal (due) to the precious religion which confers inestimable protection. This (inscription), moreover, may serve to perpetuate the remembrance of me.

"Those who are observant of Dhanmo, and delight in Dhanmo, growing in grace, from day to day, will assuredly prosper. Let my courtiers, guards, herdsmen, and learned men, duly comprehend, and fully conform to (the same) uniting (to themselves) all classes, the rich and the poor, as well as the grandees of the land. A course such as this, sustained by Dhanmo, inculcated by Dhanmo, and sanctified by Dhanmo, is the path (prescribed) by Dhanmo."

The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus said.

"Thus this Dhanmo is most excellent in its righteousness."

Wherefore should I who have been a charitable donor, in various ways, grieve (to bestow) charitable gifts, whether it be a little food, or a great offering, or even the sacrifice of my eyes? To bipeds and quadrupeds, as well as those employed in my service, various acts of benevolence have been performed by me; and at the Apana (hall of offerings) to those worthy of offerings, by me, both food and other articles, involving great expenditure, have been provided.

"Let it be duly understood that this inscription has been recorded by me with this object, as well as that it should endure for ages. Would but one person fully conform thereto, what would (not) the rest do!"

The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus said.

"(It may be said) 'this (dispensation) appears to be prodigality itself;' or of me 'he is addicted to prodigality.' That would not appear to us to be an act of impiety; or this, of me, 'he is a sinner;' or this, 'he is a miscreant,' or any such reproaches. The evil designing man (may say) these things, and such a person may represent them so, but they are not the road to (do not inflict) degradation."

"Moreover, by my contemplating the distresses affecting the poor, the unfortunate, the resentful, the proud, the envious, those bent with age, and those on the eve of becoming a prey to death, — (that contemplation) would produce in me a due sense of commiseration towards the destitute."

The Inscription fronting East.

The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus said.

"This inscription on Dhanmo has been recorded by me who have attained the twenty-seventh year of my inauguration. Dhanmo prevails for the happiness and welfare of mankind; as well as to prevent the forfeiture of their salvation. Even the sinner would admit, that it (is essential for) the happiness of mankind. Let us, therefore, steadfastly contemplate this truth. While righteous men thereby become devoted to charity, and are bent on discoursing (thereon), let me encourage their benevolent proceedings. In like manner, let me extend my solicitude towards the wealthy; and let me be specially regardful of the multitudes under my sway. Even my Pasandhi subjects present me with various tributes. I formed this resolve, under the conviction of the supreme beatitude, (resulting) from an individual himself setting an example."

The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus said.

"This inscription on Dhanmo is recorded by me who have attained the twenty-seventh year of my inauguration — should any person, after the extinction of my regal authority, learn from my subjects themselves, such a precept as this, he would prosper by the grace of Dhanmo; should he not acquire that knowledge, he (cannot) prosper by the orthodox Dhanmo." The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus asked this (query). "He, who after the extinction of my authority, would not acquire this knowledge, how should he learn these royal mandates? how can he prosper by the orthodox Dhanmo? The well disposed person, (who) has prospered by the orthodox Dhanmo, would evince gratitude for the benevolence of his benefactors. (All) conforming, good men prosper by the orthodox Dhanmo, and realize the bliss of the eight heavens." The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has declared this also. "He who attends to this precept of mine, would by the observance of Dhanmo lead a righteous life. Let me also, by the observance of Dhanmo, attain an exalted station (of righteousness). The inhabitants at large, who conform to this edict, (will) eschew evil."

Translation of the Inscription fronting South.

The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus said.

"By me, who have attained the twenty-seventh year of my inauguration, these animals have been forbid to be killed, — namely, parrots and mainas (gracula religiosa) in the wilderness; the brahmany duck (anas casaca); the goose (rather the mythological and fabulous "hansa''); the nandimuka (supposed to be the fabulous "kinnari"); the golden maina (turdus salica,); the bat, the crane, the blue pigeon, the gallinuli, the sankagamawe, wedaweyaka, the gangapuputhaka, the sankagamawe, the kadhathasayaka, the panarase, the simare, the sandike, the rokapada, the parasate, the white dove, and the village dove, as well as all quadrupeds. These, let not the tribe of huntsmen eat. For the same reason, let not 8heepand goats which are fed with stored provender, be slaughtered by any one; and those who are accustomed to receive a portion of the meat (of animals killed) should no longer enter into engagements to have them slaughtered on those terms; nor should ferocious animals either be destroyed; neither in sporting or in any other mode, nor even as a merriment, should they be killed: (on the contrary) by one living creature, other living creatures should be cherished. During (all) the three seasons of the year, on the full moon day of their (lunar months) as well as on these three days, the fourteenth, the fifteenth, and the first (of each moiety of the lunar months) (each of) these being days of religious observance, not only the agonies of slaughtering, but selling also should not be allowed. During these days, at least, on the mountain, in the wilderness, and everywhere, even the multitudes of the various species of animals which may be found disabled, should not be killed. During the three seasons, on the eighth, the fourteenth and the fifteenth (of each moiety of the lunar month) being the holy days devoted to deeds of piety, oxen, goats, sheep and pigs, which are ordinarily kept confined, as also the other species which are not kept confined, should not be restrained. Nor should it even be hinted, on the holydays of the four months of each of the seasons, that the stalled oxen even should be kept confined. By me, who have attained the twenty-seventh year of my inauguration, during the course of that period, living creatures have been released from the twenty evils (literally restraints) to which they were subjected."

The Inscription fronting West.

The raja Pandu, who is the delight of the dewos, has thus said.

"This inscription on Dhanmo is recorded by me in the twenty-seventh year of my inauguration. My public functionaries intermingle among many hundred thousands of living creatures, as well as human beings. If any one of them, should inflict injuries on the most alien of these beings, what advantage would there be in this my edict? (On the other hand) should these functionaries follow a line of conduct tending to allay alarm, they would confer prosperity and happiness on the people as well as on the country; and by such a benevolent procedure, they will acquire a knowledge of the condition both of the prosperous and of the wretched; and will, at the same time, prove to the people and the country that they have not departed from Dhanmo. Why should they inflict an injury either on a countryman of their own or on an alien? Should my functionaries act tyrannically, my people, loudly lamenting, will be appealing to me; and will appear also to have become alienated, (from the effects of orders enforced) by royal authority. Those ministers of mine, who proceed on circuit, so far from inflicting oppressions, should henceforth cherish them, as the infant in arms is cherished by the wet-nurse; and those experienced circuit ministers, moreover, like unto the wet-nurse, should watch over the welfare of my child (the people). In such a procedure, my ministers would ensure perfect happiness to my realm."

"By such a course, these (the people) released from all disquietudes, and most fully conscious of their security, would devote themselves to their avocations. By the same procedure, on its being proclaimed that the grievous power of my ministers to inflict tortures is abolished, it would prove a worthy subject of joy, and be the established compact (law of the laud). Let the criminal judges and executioners of sentences, (in the instances) of persons committed to prison, or who are sentenced to undergo specific punishments, without my special sanction, continue their judicial investigation for three days, till my decision be given. Let them also as regards the welfare of living creatures, attend to what affects their conservation, as well as their destruction: let them establish offerings: let them set aside animosity.

Hence those who observe, and who act up to these precepts would abstain from afflicting another. To the people also many blessings will result by living in Dhanmo. The merit resulting from charity would spontaneously manifest itself."

the rest as here given.]

the rest as here given.]