by W. H. Siddiqi

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress

Vol. 36 (1975), pp. 338-344 (7 pages)

1975

Table of Contents

• Preface

• Firozabad, the town

• Kotla Firoz Shah, the Citadel

• The Lat Pyramid

• The connecting bridge

• The Mosque

• The river front and Royal palaces

• Interior courts and Gates

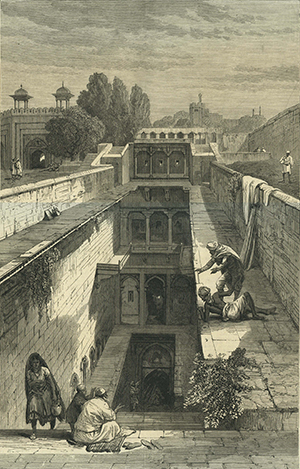

• The Baoli

• Water Tanks and Ducts

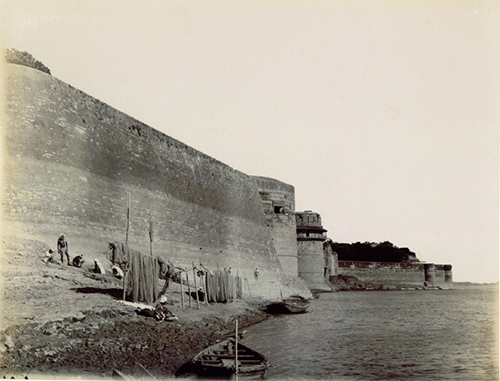

• The Citadel Walls; Main entrance bay

• Defence of the walls

• Contemporary accounts of the Citadel

• Firozabad the Royal retreat

• Features of the Palaces

• The Corps of the Palace Slaves

• The Sultan emerges in State

• Events at the Citadel

• The Sultan’s Gardens

• The Sultan’s buildings

• His Chief Architect

• The Royal establishments and domestic arrangements

• Subsequent History of the Kotla

• The Sultan retires in favour of his son Muhammad Khan

• Flight of Muhammad Khan and his supersession by Sultan Firoz’s grandson, Tughlaq Shah

• Death of Firoz Shah

• Death of his successor Tughlaq Shah and enthronement of Muhammad Khan at Samana

• Death of Sultan Muhammad

• Succession of Prince Mahmud at Jahanpanah

• Rebellion and rival sovereignty of his cousin Nasrat Shah at Firozabad

• Timur’s invasion

• Subsequent History

• Appendix

• Index

• Translation of the extracts from Sirat-i-Firozshahi [Folios 91 (b) to 105 (b)]

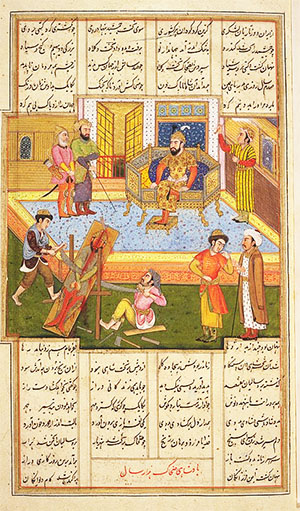

• Transcript of Sirat-i-Firozshahi [Folios 91 (b) to 105 (6)] with illustrations

• LIST OF PLATES.

o Plate I. — Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi. Bara gateway. General view. (South-west).

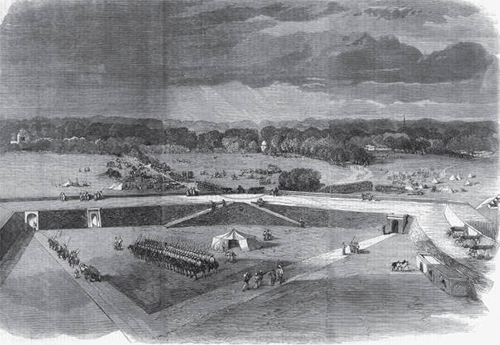

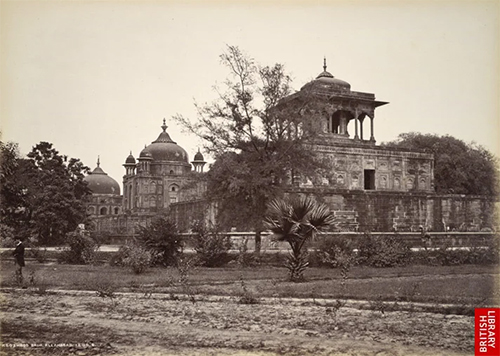

o Plate II. — Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi; Vue D'oiseau of a conjectural reconstruction of the ruined citadel.

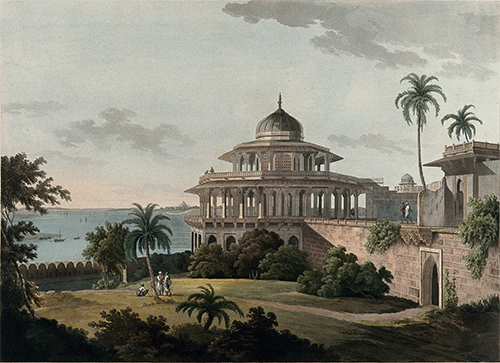

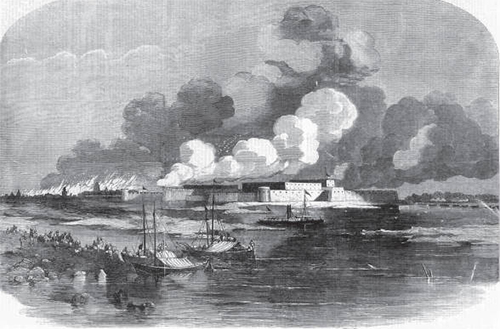

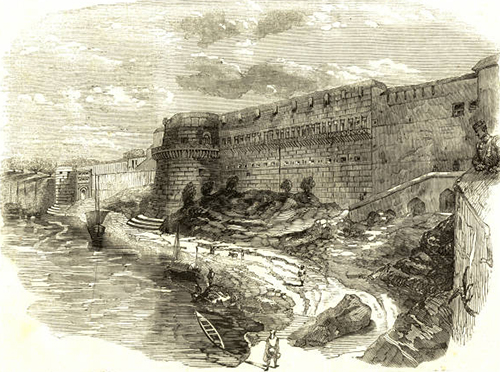

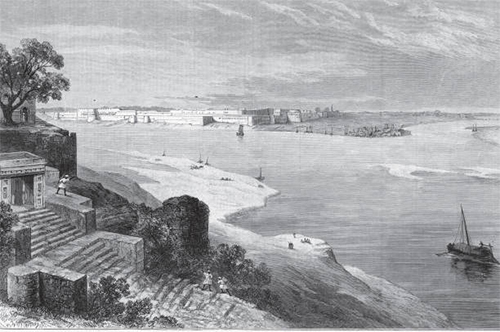

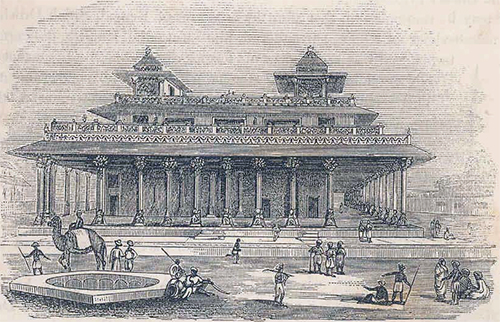

o Plate III. — Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi; Perspective view of river front.

o Plate IV. — Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi; General view of the mosque. (North-west).

o Plate V. — Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi; view of the Lat Pyramid.

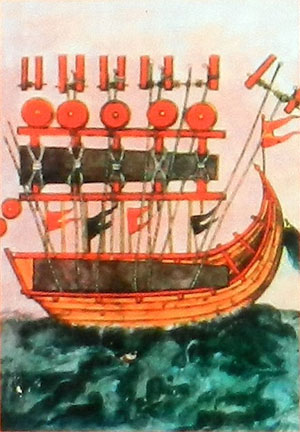

o Plate VI. — (Coloured.) Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi; Illustrations from Sirat-i-Firozshahi —

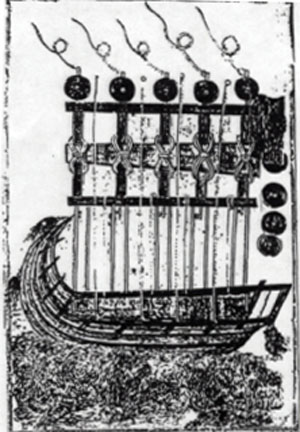

(а) Removing wheels of the cart from one side and tying ropes and pulling up the pillar to place it in the boat.

(b) Arrival of boat with pillar on the bank of the Jumna (near Delhi), tying ropes to the pillar to remove it from the boat and place it on the cart.

(c) The monolith being carried on the ladha (cart) towards the town of Firozabad (Delhi).

(d) Arrival of the cart with pillar in front of the mosque of Firozabad (Delhi).

• LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS APPEARING IN THE TRANSCRIPT OF SIRAT-I-FIROZSHAHI.

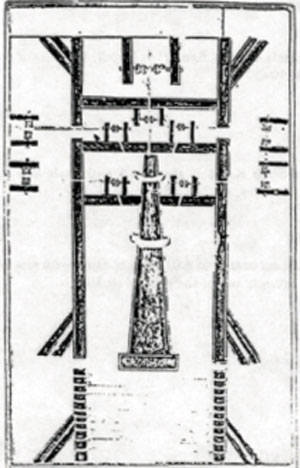

o Fig. 1. — Erection of piers and pulleys and tying of ropes, for taking down the stone pillar.

o Fig. 2 . — Pasheb on which the stone pillar would rest while taken down.

o Fig. 3. — Erection of pulleys and raising the pillar in order to place it on the ladha (cart).

o Fig. 4. — Arrival of the ladha with the stone pillar, at the bank of the Jamna river.

o Fig. 5. — Constructing the foundations of a structure, 61 yards square thereon to set up the pillar.

o Fig. 6. — Building of the first storey and raising the pillar on its top by means of ropes.

o Fig. 7. — Plan of the second storey.

o Fig. 8. — Raising the pillar two yards at a time, first at one end and then at the other.

o Fig. 9. — Third storey of the structure on which the pillar was set up.

PREFACE.

In the preparation of this memoir on the ruins of Kotla Firoz Shah at Delhi Mr. Page had in mind the desirability of attempting to retrieve for the reader the original "atmosphere" of the old fabric, with all its historical associations and charm: and to reveal the distinctive traits and outlook of those who founded and peopled it in the 14th Century A.D.

As a means to this, Mr. Page had recourse to the original narratives of the Mussalman historians of the time (as translated in Messrs. Elliott and Dowson's invaluable volumes) and has quoted in extenso from their writings. Verbose and redundant though these annals often are, they nevertheless reflect, as nothing else can, the mentality of their environment and period, and will, it is hoped, help the reader to visualise the life of the time, and repopulate for him the empty remains of what was once the royal retreat of a Turkish King of Delhi.

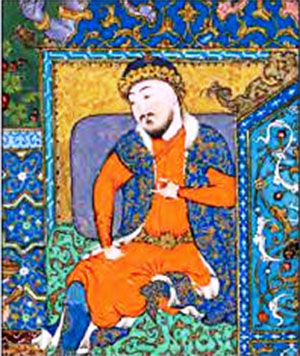

Besides the works, particularly by Muslim historians referred to by Mr. Page in his Memoir, there exists another trustworthy and contemporary account of Firoz Shah's reign as narrated in the pages of Sirat-i-Firozshahi, a Persian manuscript in Nastaliq characters deposited in the Oriental Public Library at Bankipore and enlisted in its Catalogue as No. 547. From the Catalogue it appears that nothing is known about the author of Sirat-i-Firozshahi but the verse at the end of the manuscript assigns the work to A.H. 772 (A.D. 1370). i.e., the twentieth year of the reign of Firoz Shah. Sirat-i-Firozshahi thus chronicles the events of the earlier part of Firoz Shah's reign.God said it, I believe it, That settles it.

It is divided into four chapters or babs; and the folios of the second chapter dealing with the removal of the Minarah-i-Zarrin (Golden Pillar) have been transcribed and translated by Mr. Mohammad Hamid Kuraishi, B.A., to form a supplement to Mr. Page's Memoir on Kotla Firoz Shah. The illustrations contained in the original not only add charm to the manuscript but portray the minutest details of the removal of the pillar — its carriage in boats and installation on the citadel at Firozabad, where it stands to the present day.

J. F. BLAKISTON.

Director General of Archaeology

New Delhi, March 1936.

-- Memoirs Of the Archaeological Survey of India, No. 52: A Memoir on Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi, by J.A. Page, A.R.I.B.A., Late Superintendent, Archaeological Survey of India, With a Translation of Sirat-i-Firozshahi by Mohammad Hamid Kuraishi, B.A., Superintendent, Archaeological Survey of India, 1937

The Asokan pillars forming the earliest sculptural monuments of India occupy a unique position for their valuable edicts containing information on political, religious and social life of the Mauryan period.1 But it is not popularly known that out of ten Asokan pillars at least five of them were discovered and re-erected by Sultan Firuz Shah Tughluq (A.D. 1351-1388). He took great interest in the preservation of ancient monuments and evinced particular interest in tracing and re-erecting these columns at different places in his empire. This fact is little known, not only to the general public but also to the experts and specialists. No attempt seems to have been made to study in a proper sequence the events connected with the discovery of the pillars by Firuz Shah. The number of Asokan pillars discovered and re-erected by the Sultan has not been ascertained. None has cared to trace the chronology of the re-setting of the various pillars at different places. Cunningham who took pains to give an account of the discoveries of the pillars had no access to authentic contemporary literature, therefore, most of his dates are incorrect.2

However, an extremely valuable account of Delhi-Topra pillar is contained in Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India on Kotla Firoz Shah, Delhi edited by J. A. Page with an English translation of Sirat-i-Firoz Shah by Mohammad Hamid Kuraishi which was published in 1937.3 [J. A. Page, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, No. 52, -- A Memoir on Kotla-Firoz Shah (Delhi-1937). It deals with history and archaeological remains of Firuzabad, Firuz Shah's New Delhi and contains second chapters of the Persian text of Sirat-i-Firuz Shahi with its English translation and illustration of original drawings of Delhi-Topra pillar being carried in boat and re-erected in stages on a specially built three storeyed edifice.]

Page did not study the other two pillars of Fatehabad and Hissar (now in Haryana) which were already noticed by Cunningham. It is, therefore, purposed to give an authentic account of the re-setting of all the five pillars by Firuz Shah in a proper sequence.

The discovery of the first two pillars:

XVI. Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi, of Shams-i Siraj 'Afif

This History of Firoz Shah is devoted exclusively to the reign of that monarch, and therefore has a better right to the title than Barni's history, which embraces only a small portion of the reign of Firoz, and bears the title simply because it was written or finished during his reign. Little is known of Shams-i Siraj beyond what is gleaned from his own work. He was descended from a family which dwelt at Abuhar, the country of Firoz Shah's Bhatti mother. His great grandfather, he says, was collector of the revenue of Abuhar, and was intimate with Ghiyasu-d din Tughlik before he became Sultan. He himself was attached to the court of Firoz, and accompanied him on his hunting expeditions.]

The work has met with scarcely any notice, whilst every historian who writes of the period quotes and refers to Ziau-d din Barni. The reason of this may be that Shams-i Siraj enters more than usual into administrative details, and devotes some chapters to the condition of the common people — a matter of the utmost indifference to Muhammadan authors in general. His untiring strain of eulogy could not have condemned him in their eyes, as they were accustomed to little else in all the other histories they consulted; so that we must either attribute the neglect of this work to the cause assigned, or to the fact of its having at a comparatively late period been rescued from some musty record room. The work, consisting of ninety chapters, contains an ample account of this Akbar of his time; and, making due allowance for the prevalent spirit of eulogium and exaggeration, it not only raises in us a respect for the virtues and munificence of Firoz, and for the benevolence of his character, as shown by his canals and structures for public accommodation, but gives us altogether a better view of the internal condition of India under a Muhammadan sovereign than is presented to us in any other work, except the A'yin-i Akbari.

[In style, this history has no pretensions to elegance, being, in general, very plain. The author is much given to reiterations and recapitulations, and he has certain pet phrases which he constantly uses. Sir H. Elliot desired to print a translation of the whole work, and he evidently held it in high estimation. A portion of the work had been translated for him by a munshi, but this has proved to be entirely useless. The work of translation has, consequently, fallen upon the editor, and he has endeavoured to carry out Sir H. Elliot's plan by making a close translation of the first three chapters, and by extracting from the rest of the work everything that seemed worthy of selection. The translation is close, without being servile; here and there exuberances of eloquence have been pruned out, and repetitions and tautologies have been passed over without notice, but other omissions have been marked by asterisks, or by brief descriptions in brackets of the passages omitted. Shams-i Siraj, with a better idea of method than has fallen to the lot of many of his brother historians, has divided his work into books and chapters with appropriate headings.

[Besides this history of Firoz Shah, the author often refers to his Manakib-i Sultan Tughlik, and he mentions his intention of writing similar memoirs of the reign of Sultan Muhammad, the son of Firoz Shah. Nothing more appears to be known of these works. Copies of the Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi are rare in India, and Colonel Lees, who has selected the work for publication in the Bibliotheca Indica, has heard only of "one copy in General Hamilton's library, and of another at Dehli, in the possession of Nawab Ziau-d din Loharu, of which General Hamilton's is perhaps a transcript."1 [Journ. R.A.S., New Series, iii., 446.] The editor has had the use of four copies. One belonging to Sir H. Elliot, and another belonging to Mr. Thomas, are of quite recent production. They are evidently taken from the same original, most probably the Dehli copy above mentioned. The other two copies belong to the library of the India Office, one having been lately purchased at the sale of the Marquis of Hastings's books. These are older productions; they are well and carefully written, and although they contain many obvious errors, they will be of the greatest service in the preparation of a correct text. None of these MSS. are perfect.The two modern copies terminate in the middle of the ninth chapter of the last book. The Hastings copy wants several chapters at the end of the first and the beginning of the second book; but it extends to the eleventh chapter of the last book, and has the final leaf of the work. The other MS. ends in the middle of the fifteenth chapter of the last book, and some leaves are missing from the fourteenth. Fortunately these missing chapters seem, from the headings given in the preface, to be of no importance.

[A considerable portion of the work was translated in abstract by Lieut. Henry Lewis, Bengal Artillery, and published in the Journal of the Archaeological Society of Dehli in 1849.]

-- XVI. Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi, of Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, Excerpt from The History of India As Told By Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, edited from the posthumous papers of the Late Sir H.M. Elliot, K.C.B., East India Company's Bengal Civil Service, by Professor John Dowson, M.R.A.S., Staff college, Sandhurst, Vol. III, P. 269-364, 1871

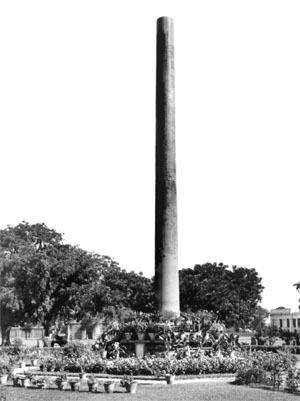

Delhi-Topra, Feroz Shah Kotla, Delhi (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII; moved in 1356 CE from Topra Kalan in Yamunanagar district of Haryana to Delhi by Firuz Shah Tughluq.

-- Pillars of Ashoka, by Wikipedia

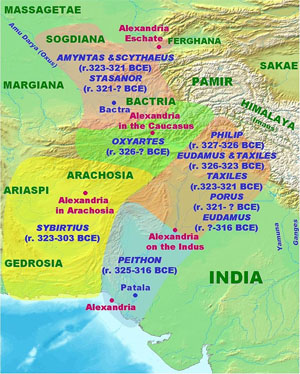

During his hunting expeditions in 1366 Firuz Shah discovered two remarkable pillars of stone -- one in the village of Topra (Tobra) situated in the hills of Salaura and Khizrabad, and the other in the vicinity of the town of Mirah.4 The village Tobra of Shams Siraj 'Afif' has been satisfactorily identified with Topra in Ambala district of Haryana.

Firuz was so much excited and impressed that he decided to take the pillar from Topra across a distance of over 150 miles to his newly built city Firuzabad. It is interesting to know the details and see illustration in line drawings how this pillar was dislodged, transported by boat and re-erected in stages on a three storied pyramidal pavilion in front of the Jami Mosque of Firuzabad in A.D. 1367.5

After the pillar was finally set up the top was ornamented with black and white stone railings5 and was crowned by a gilded copper cupola. The gold pinnacle of the pillars was intact in A.D. 1611 when William Finch visited Delhi. Firoz Shah was very keen to know the purport of the Mauryan inscription. Many reputed Brahmin scholars of the age are reported to have tried but according to Afif, they could not completely decipher the epigraph except giving its traditional accounts. The pillar is now standing on the above mentioned pyramidal structure in Kotala Firoz Shah, New Delhi. It bears the longest of the pillar edicts of Asoka, giving summary of what Asoka did for "the progress of men by an adequate promotion of Dharma".7

Delhi-Meerut, Delhi ridge, Delhi (Pillar Edicts I, II, III, IV, V, VI; moved from Meerut to Delhi by Firuz Shah Tughluq in 1356, broken in pieces during transportation.

-- Pillars of Ashoka, by Wikipedia

Ashoka's Pillar at Kamla Nehru Ridge, near Hindu Rao hospital, is one of the two brought in by Firoz Shah Tughlaq in the mid-13th century. Brought from Meerut after one of his campaigns, the pillar was transported meticulously through the Yamuna river on barges and then hauled up on a 42 wheel cart from the bank to the ridge. Another of its counterparts can be found in the urban village of Firoz Shah Kotla.

The construction is mostly made of sandstone, quarried from Chunar town in Mirzapur, Uttar Pradesh, presently another small town (known for its pottery) on the Indo-Gangetic belt but historically a very important destination, finding mention in the ancient Hindu Puranas (scriptures). Huge rock slabs were chiseled at the quarry and then sent across the country. The pillar suffered an accident during the tumultuous reign of the Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar during the first half of the 17th century. The top of the pillar which got blown off as a consequence still remains in-state as a result. [???] The pieces of the pillar were transported for safekeeping to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Calcutta in 1866, but were brought back and restored in its original place in 1887, where it still stands today.

The pillar is about 10 feet in height with a diameter of about three quarters of a metre and features inscriptions in Brahmi Script; mostly focusing on Ashoka’s major propaganda, viz, his conversion to and propagation of Buddhism and social and animal welfare. Further studies have revealed later inscriptions in Sanskrit around Ashoka’s texts, assumed to date back to the rule of the Chauhan King Visala around the 11th century AD. Firoz Shah himself added some bits of decoration to the pillars later.

The pillar is located at one end of the Kamla Nehru Ridge in North Delhi, with Mutiny Memorial situated nearby.

-- Surviving As A Historical Relic Since The 13th Century, Here's All About The Ashokan Pillar, by Delhi Dwell, 21 Aug 2017

The next Asokan pillar at Delhi can be seen between the Chauburji-Masjid and Hindu Rao Hospital on the town of Mirath and set up by Firuz over the top of the three storeyed imposing Hunting Palace better known as Kushk-i-Shikar (now mass of ruins). According to Afif this pillar was removed by Sultan Firuz with similar skill and labour, and was re-erected on a hill on the Kushk-i-Shikr. After the erection of the pillar a large town sprang up and the nobles of the court erected their houses there. The hunting palace (Kushk-i-Shikar) was built by Firuz Shah Tughluq in A.H. 755 (A. D. 1354) and was originally a lofty rubble built structure in three storeys, having circular bastions at the corners, The apartments had many entrances of pointed arches on all sides. The bastions as well as top pavilions were covered with low domes of the Khalfi-Tughluq variety. The stone column was fixed on the top of the central structure which was flanked by two square pavilions of similar height.

Afif informs us that the day Firuz successfully raised the second pillar to its proper height he ordered state rejoicing. The whole day was observed as a state festival and all people were entertained; and passers-by irrespective of all distinctions enjoyed sharbat (cold sweet drink). The pillar of Kushk-i-Shikar, remained intact until it was damaged, and broken into five pieces on account of an explosion of the neighbouring powder magazine during the reign of Farrukhsiyar (A.D. 1713-19.) Its inscribed surface was later sawed off and sent to the Asiatic Society of Bengal at Calcutta wherefrom all the pieces were received back and re-set in 1867 by the British on the site of the dismantled palace on the bridge where it can be seen at present. The pillar now measures 10 m. in length.

Thanks largely to Hodgson's discoveries along the Nepalese frontier, Prinsep knew of five Ashoka columns. As he deciphered their messages a sixth came to light in Delhi (the second to be found there). Broken into three pieces and buried in the ground, it was thought to have been the casualty of an explosion in a nearby gunpowder factory sometime in the 17th century. The inscription was badly worn, though evidently the same as that on the other pillars. In due course the whole pillar was offered to the Asiatic Society for their new museum. They accepted it but found the difficulties and cost of transporting it to Calcutta to be prohibitive; eventually they settled for just the bit with the inscription on it.

The question of how these pillars had originally been moved round India, and whether they were still in their ordained positions, was an intriguing subject in itself. It was now appreciated that they were all of the same stone, all polished by the same unexplained process, and therefore all from the same quarry. Prinsep thought this was somewhere in the Outer Himalayas, although we now know their source to have been Chunar on the Ganges near Benares. Either way, they had somehow been moved as much as 500 miles, no mean feat considering that the heaviest weighed over 40 tons.

-- India Discovered, by John Keay

It is possible that after the discovery and re-erection of the two Asokan columns at Delhi, Firuz Shah searched for other such relics in the region. His explorations may have resulted in the discovery of the Hissar pillars which was certainly found later than the Delhi pillars. Had this been discovered earlier it should have been mentioned in the contemporary chronicles and it may have received the same royal attention which was given to the Delhi pillars. Hissar, where another Asokan pillar was re-erected, was a village which was raised to the status of a town by Firuz Shah after his dramatic marriage with the sister of a Gujar named Saharan who later became a nobleman and was favoured with the title of Wajih-ul-Mulk.8 According to Afif, the city of Hissar Firuza was founded by Firuz after his Bengal campaign (1356) earlier than Firuzabad in Delhi. The city was made the headquarter of a newly constructed shiq (district) at the cost of the shiq of Hansi.9

Firuz built a magnificent palace at Hissar, the notable remains of which are still extant and are named after the Gujar queen of the Sultan (Gujari-Mahal). Afif has given interesting description of the palace and underground chambers (Takhana) which formed a complicated irregular structure with many zigzag passages which made it extremely difficult for persons walking through them to find their way out unless they knew the scheme.10

Hisar Ashokan pillar

The mosque got its name from Lat, a column located on the North-East of its courtyard. The Lat was once a part of an Ashokan pillar, one of the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka dating to 250–232 BCE. This has been proved by the inscriptions in Brahmi script on the pillar, deciphered in 1837 by James Prinsep, an archaeologist, philologist, and official of the East India Company. The Ashokan pillar, likely taken from its nearby original location at Agroha Mound, was cut for the ease of transportation and rejoined in four portions here. The remaining bottom portions are at the Fatehabad mosque. The four upper portions of the Ashokan pillar here are tapering registers with a finial topped by an iron rod.

-- Firoz Shah palace complex, by Wikipedia

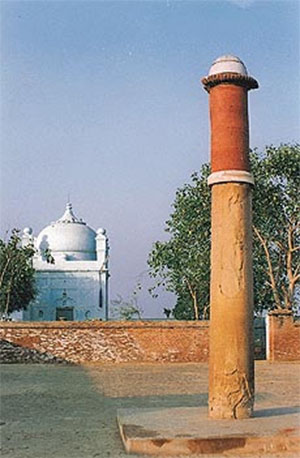

The Hissar pillar is standing in the courtyard of the mosque of the ruined fort of Hissar. The mosque is locally known as Lat-ki-Masjid, apparently named after the lofty stone tower of its courtyard. The original findspot of this pillar is not known. The contemporary chroniclers are silent about it. It may be presumed that this column was found at a later date at least not before the compilation of Tarikh-i-Firuz Shahi which mentioned the palace complex of Hissar in details. It may have been found from certain ancient ruins in the region not very far from Hissar. Cunningham suspected it to be a relic of Buddhist monument shifted from Hansi, a town of considerable antiquity.11

XV. Tarikhi Firoz Shahi of Ziaud Din Barni [Ziauddin Barani]

This History is very much quoted by subsequent authors, and is the chief source from which Firishta draws his account of the period. Barni takes up the History of India just where the Tabakat'i Nasiri leaves it; nearly a century having elapsed without any historian having recorded the events of that interval. In his Preface, after extolling the value of history, he gives the following account of his own work. ["Having derived great benefit and pleasure from the study of history, I was desirous of writing a history myself, beginning with Adam and his two sons. * * * But while I was intent upon this design, I called to mind the Tabakat-i Nasiri, written with such marvellous ability by the Sadar-i Jahan, Minhaju-d din Jauzjani. * * * I then said to myself, if I copy what this venerable and illustrious author has written, those who have read his history will derive no advantage from reading mine; and if I state any thing contradictory of that master's writings, or abridge or amplify his statements, it will be considered disrespectful and rash. In addition to which I should raise doubts and difficulties in the minds of his readers. I therefore deemed it advisable to exclude from this history everything which is included in the Tabakat-i Nasiri, * * * and to confine myself to the history of the later kings of Dehli. * * * It is ninety-five years since the Tabakat-i Nasiri, and during that time eight kings have sat upon the throne of Dehli. Three other persons, rightly or wrongfully, occupied the throne for three or four months each; but in this history I have recorded only the reigns of eight kings, beginning with Sultan Ghiyasu-d din Balban, who appears in the Tabakat-i Nasiri under the name of Ulugh Khan.]

"First. — Sultan Ghiyasu-d din Balban, who reigned twenty years.

"Second. — Sultan M'uizzu-d din Kai-kubad, son of Sultan Balban, who reigned three years.

"Third. — Sultan Jalalu-d din Firoz Khilji, who reigned seven years.

"Fourth. — Sultan Alau-d din Khilji, who reigned twenty years.

"Fifth.— Sultan Kutbu-d din, son of Sultan 'Alau-d din, who reigned four years and four days.

"Sixth. — Sultan Ghiyasu-d din Tughlik, who reigned four years and a few months.

"Seventh. — Sultan Muhammad, the son of Tughlik Shah, who reigned twenty years.

"Eighth. — Sultan Firoz Shah, the present king, whom may God preserve.

"I have not taken any notice of three kings, who reigned only three or four months. I have written in this book, which I have named Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, whatever I have seen during the six years of the reign of the present king, Firoz Shah, and after this, if God spares my life, I hope to give an account of subsequent occurrences in the concluding part of this volume. I have taken much trouble on myself in writing this history, and hope it will be approved. If readers peruse this compilation as a mere history, they will find recorded in it the actions of great kings and conquerors; if they search in it the rules of administration and the means of enforcing obedience, even in that respect it will not be found deficient; if they look into it for warnings and admonitions to kings and governors, that also they will find nowhere else in such perfection. To conclude, whatever I have written is right and true, and worthy of all confidence.''

Ziau-d din Barni, like many others, who have written under the eye and at the dictation of contemporary princes, is an unfair narrator. Several of the most important events of the reigns he celebrated have been altogether omitted, or slurred over as of no consequence. Thus many of the inroads of the Mughals in the time of Alau-d din are not noticed, and he omits all mention of the atrocious means of perfidy and murder, by which Muhammad Tughlik obtained the throne, to which concealment he was no doubt induced by the near relationship which that tyrant bore to the reigning monarch. With respect, however, to his concealment of the Mughal irruptions, it is to be remarked, as a curious fact, that the Western historians, both of Asia and Europe, make no mention of some of the most important. It is Firishta who notices them, and blames our author for his withholding the truth. Firishta's sources of information were no doubt excellent, and the general credit which his narrative inspires, combines with the eulogistic tone of Ziau-d din Barni's history in proving that the inroads were actually made, and that the author's concealment was intentional. The silence of the authorities quoted by De Guignes, D'Herbelot, and Price, may be ascribed to their defective information respecting the transactions of the Mughal leaders to the eastward of the Persian boundary.

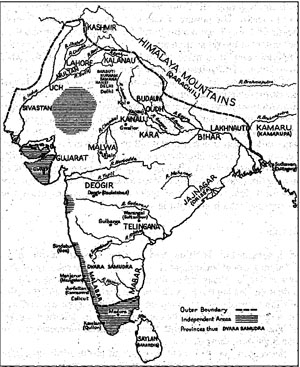

The author did not live to complete his account of Firoz Shah, but towards the close of his work lavishes every kind of encomium, not altogether undeserved, upon that excellent prince. Notwithstanding that Firishta has extracted the best part of the Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, it will continue to be consulted, as the reigns which it comprises are of some consequence in the history of India. The constant recurrence of Mughal invasions, the expeditions to the Dekkin and Telingana, the establishment of fixed prices for provisions, and the abortive means adopted to avert the effects of famine, the issue of copper money of arbitrary value, the attempted removal of the capital to Deogir, the wanton massacres of defenceless subjects, the disastrous results of the scheme to penetrate across the Himalaya to China, the public buildings, and the mild administration of Firoz; all these measures, and many more, invest the period with an interest which cannot be satisfied from the mere abstract given by Firishta.

[Barni is very sparing and inaccurate in his dates. He is also wanting in method and arrangement. He occasionally introduces divisions into his work, but in such a fitful irregular way that they are useless. In his latter days "he retired to a village in the suburbs of Dehli, which was afterwards the burial place of many saints and distinguished men. He was reduced to such extreme poverty that no more costly shroud than a piece of coarse matting could be furnished for the funeral obsequies." His tomb is not far from that of his friend, the poet Amir Khusru.1 [Col. Lees. Jour., R.A.S., vol. iii., new series, p. 445.]

[Sir H. Elliot had marked the whole of Barni's history for translation, intending probably to peruse it and expunge all trivial and uninteresting passages. The translation had been undertaken by a distinguished member of the Bengal Civil Service, but when required it was not forthcoming. After waiting for some time, the editor, anxious to avoid further delay, set to work himself, and the whole of the translation is from his pen.2 [When a portion of the translation was already in type, and the editor was at work on the last reign, a letter arrived from India with translations of the histories of the second and sixth of the eight kings — too late to be of any service.] It is somewhat freer in style than many of the others, for although the text has been very closely followed, the sense has always been preferred to the letter, and a discretion has been exercised of omitting reiterated and redundant epithets. All passages of little or no importance or interest have been omitted, and their places are marked with asterisks. The Extracts, therefore, contain the whole pith and marrow of the work, all that is likely to prove in any degree valuable for historical purposes. Barni's history of the eighth king, Firoz Shah, is incomplete, and is of less interest than the other portions. In the weakness of old age, or in the desire to please the reigning monarch, he has indulged in a strain of adulation which spoils his narrative. The Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi of Shams-i Siraj, which will follow this work, is specially devoted to the reign of that king. Shams-i Siraj has therefore been left to tell the history of that monarch. But the two writers have been compared, and one or two interesting passages have been extracted from Barni's work.

[The translation has been made from the text printed in the Bibliotheca Indica, and during the latter half of the work two MSS., borrowed by Sir H. Elliot, have been also constantly used,1 [These MSS. being carefully secured by Lady Elliot, could not be obtained while she was absent from home. They have since been examined in respect of several passages in the earlier parts of the translation.] These MSS. prove the print, or the MSS. on which it was based, to be very faulty. A collation would furnish a long list of errata and addenda. One of the two MSS. gives the original text apparently unaltered;2 [This is said to be "a perfect copy, and the autograph of the author. It belongs to the Nawwab of Tonk, by whose father it was plundered from Boolandshahr." It is a good MS., but, so far from being an autograph, the colophon gives the name of the scribe and the date of the transcription, 1019 (1610 A.D.)] but the other has been revised with some judgment. It sometimes omits and sometimes simplifies obscure and difficult passages, and it occasionally leaves out reiterations; but it is a valuable MS., and would have been of great assistance to the editor of the text.]

-- XV. Tarikhi Firoz Shahi of Ziaud Din Barni [[Ziauddin Barani]], Excerpt from The History of India As Told By Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, edited from the posthumous papers of the Late Sir H.M. Elliot, K.C.B., East India Company's Bengal Civil Service, by Professor John Dowson, M.R.A.S., Staff college, Sandhurst, Vol. III, 1871, P. 93.

Cunningham does not give any further details of its artistic appearance. He quotes the statement of Captain Brown in 1838: "The stone appears of the same (i.e., Buddhist) description, but has suffered much from exposure to climate. It has also the appearance of having been partially worked by Firoz's order, and probably some inscription was cut upon it by his workmen, but of which there is now no trace owing to the peeling off of the exterior surface. I, however, observed near the upper part of the stone some of the ancient letters which apparently have been saved by accident. The ancient stone is of one piece and is 10 ft. 10 inches high."12 Standing on the height of the inner side of the main entrance in the courtyard of the mosque the lowest portion of this solid tower is a part of a monolithic pillar, evidently of Mauryan origin. To give a proper shape and height it has been designed in the form of a solid minaret by providing red sand stone shafts interrupted by circular stone discs, the top crowned by an Amalaka marble. The lowest part is badly damaged, but the Mauryan polish and remnants of Brahmi inscription and fragmentary epigraphs of North Indian Script of about 4th/5th Century are still extant.13 The total height of the composite pillar is 10.00 m., the remaining parts from the base being 3.50, 3.00, 2.00, 1.50 ms., respectively. The diameter at the base is 0.75 m. Such tapering solid minarets of stone are found in early mosques of Gujarat, indicating Tughluq influence on regional style.

On the uppermost part of the fort, there is an Idgah. In the precinct of this Idgah, there is a thick lofty pillar in the centre. Constructed with the mixture of Balua soil, red marble, white marble and iron, the pillar is 15.6 feet in height, and six feet in circumference. Verses from the Koran and some brief information about the Tughlaq dynasty have been carved out on 36 slabs of the pillar. Some historians claim this pillar to be the "Kirti Stambha" of Ashoka the Great. The Hisar gazetteer also mentions that the pillar seemed to have been constructed by some Hindu king as words from Sanskrit language have also been found on the slabs. Besides this, the artistic work on the two mosques in this fort also resemble the work on the ancient Hindu temples. These historians believe that the pillar was constructed during the Ashoka period and was given touches of Muslim art by Firoz Shah Tughlaq during 14th century. In the same Idgah, on the west side of the pillar, there is an inscription. On this has been engraved in Arabian language that the Mughal emperor Humanyun came here and constructed a mosque at this place.

-- Fatehabad: A town steeped deep in history, by Sushil Manav, 1999

This mosque known as Humayun’s mosque was built by the Mughal emperor Humayun (1529-1556 AD) at a place where the Lat erected by the Delhi Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq was already standing. The mosque consists of an oblong open courtyard. To the west of this mosque is a screen made of Lakhauri bricks. The screen contains a mihrab flanked by two arched recesses on either side. An inscription praising emperor Humayun was found here.

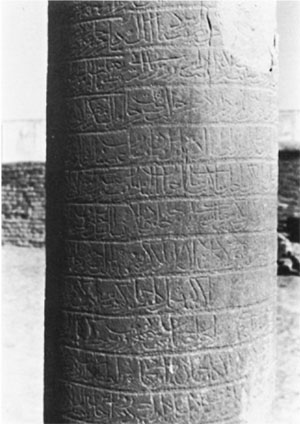

History and description: Standing at a height of over 6 metres, the Lat appears to be a portion of one of the pillars erected by Emperor Ashoka possibly at Agroha or Hansi. The Ashokan epigraph that was once engraved on the pillar was apparently very systematically chiseled off for writing the Tughlaq inscription, recording the genealogy of Firoz Shah in beautiful Tughra-Arabic characters carved in high relief. This Lat (the pillar) stands in the centre of what now looks like an ancient walled Idgah.

-- Lat of Feroz Shah, by fatehabad.nic.in

Figure 4. Pillar, Fatehabad. Photo: author.

The third lat (fig. 4) is located in the town of Fathabad, or Fatehabad,16 Firuz Shah's earliest urban foundation, built in the first year of his reign, A.H. 752/A.D. 1351-52, and located on the road connecting the important sites of Delhi, Hansi, and Multan. The lat may date from this time, although no firm evidence supports this claim. Today it stands in the center of the courtyard of a modern 'idgah, but its original context is not known, and whether the pillar was free-standing or associated with a prior architectural structure remains a mystery. Fatehabad continued to be an important site into Mughal times, when a Humayun-period mosque was built on the site. Mughal patronage of the pillar is unlikely, and there is no evidence of any other builder at the site after the Tughluq period.17

The Fatehabad lat consists of a single column of beige stone standing 3.1 meters above the foundation. This piece is surmounted by a drum of white stone and four sections of red stone. The column is crowned by a red stone amalaka, a round fluted element of Indian origin,18 and a white stone cap raising the height of the column to 4.8 meters above the foundation. There is an estimated 1 to 1.5 meters below the ground. The diameter of the lat is 59 centimeters at its base and 52 centimeters at its top.

Fig. 5. Detail of pillar inscription, Fatehabad. Photo: author.

The most remarkable feature of the Fatehabad lat is its inscription (fig. 5), one of the longest Indo-Islamic epigraphs of the Delhi sultanate; it is historical in content and specific to the Tughluq dynasty.19 [[Mehrdad] Shookoohy, Haryana I, 15-22 and pls. 1-70. [Haryana I. The Colum of Firuz Shah and Other Islamic Inscriptions from the District of Hisar. Plates i-xc. Shokoohy, Mehrdad. School of Oriental and African Studies, London 1988. 42 pp. + 90 plates. Publisher's cloth. 33,5x28,5 cm. Library stamps and bookplate. Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum. Part I IV Persian Inscriptions down to the early Safavid Period. Vol. XLVII India: State of Haryana.]] The date of the lat's installation is not known or given in the epigraph, but specific historical events referred to in the epigraph support attribution to Firuz Shah. The bottom section of the lat appears to be part of an ancient pillar brought to the site during the Tughluq period. Although a Mauryan origin is unlikely, it is nevertheless reused.20 [John Irwin expresses doubt about an Asokan origin for the Fatehabad lat in pt. 4, p. 744, n. 47 of John Irwin, "'Asokan' Pillars: A Reassessment of the Evidence," pts. 1-4, The Burlington Magazine 115 (Nov. 1973): 706-20; 116 (Dec. 1974): 712-27; 117 (Oct. 1975): 631-43; 118 (Nov. 1976): 734-53.] Citing similarities in stone type and column diameters, Cunningham believed that the pillar at Fatehabad and the pillar in nearby Hissar were originally parts of the same piece of stone. If his supposition is correct, then these columns were probably installed simultaneously.

-- The Monumental Pillars of Fīrūz Shāh Tughluq, by William Jeffrey McKibben, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 24 (1994), pp. 105-118 (14 pages), Published by: Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan

1. Lat, Fathabad, Hissar district, ca. 752/1351

Inside the precinct of the Idgah is a remnant of a lat, possibly Asokan in origin. The lat has been associated, in other cases, with a mosque and probably functioned as a type of minar, a concept which is examined in depth in the following chapter. The lat of Fathabad bears a Tughra Arabic inscription which is said to trace the genealogy of the Tughluq line.22 [The Fathabad column epigraph is long, consisting of 36 concentric bands of inscription. It is not known how much of the inscription is lost but, judging from the height of the column, it probably survives in almost its entirety. The lat inscription is published in Subhash Parihar, Muslim Inscriptions in the Punjab, Harayana, and Himachal Pradesh, 1985, p. 18 (No. 3.6) and illustration 7. A translation of it was allegedly done by Maulvi Ziyauddin Khan but it has not surfaced. See P. Horn "Muhammadan Inscriptions from the Suba of Delhi," Epigraphica Indica 2 (Delhi 1970), pp. 130-159 and 424-437; and H. B. W. Garrick, "Report of a tour in the Punjab and Rajputana, in 1883-84," A.S.J. Reports v. 23, Varanasi, n.d. Not all authors accept an Asokan origin for the Fathabad lat.]

-- The Architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq, Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University, by William Jeffrey McKibben, B.A., M.A., 1988

The fourth pillar of this class is found in Fatehabad in District Hissar of Haryana. The town of Fatehabad was founded by Firuz Shah earlier than Firuzabad, Delhi and Hissar. It was named after his favourite son Fath Khan who is said to have been at that place. The column is standing in the spacious courtyard of a mosque which was erected by Firuz Shah himself. The mosque is now represented by its four brick walls and the mihrabs in the western wall. This pillar consists of two parts, the lower one being the original part of monolithic Mauryan pillar in grey sandstone of the Chunar variety while the upper part of red sandstone of the Tughluq period is separated by an abacus in white marble. The top of this tower is ornamented by an amalaka of red sandstone and crowned by a marble solid cap. The total height of the pillar is about 5 mts. The portion below the projecting disc which forms part of the grey monolithic pillar bears the circular bands of Persian inscription in beautiful Naskh characters of Firuz Shah Tughluq and gives the brief account of the Tughluq dynasty.

On close observation I noticed a line of Brahmi letters on the top of the Persian inscription immediately below the circular disc. This fragmentary Brahmi writing was not noticed by Cunningham or any other scholar. It is curious to note that these inscriptions have not been studied and published so far. The lower portion column is subjected to damaging weather effect.

Cunningham suspected that the Fatehabad pillar was the part of Hissar pillar which is not based on any evidence, since the diameter of both fragmentary columns substantially differ from each other.

In Allahabad there is a pillar with inscriptions from Ashoka and later inscriptions attributed to Samudragupta and Jehangir. It is clear from the inscription that the pillar was first erected at Kaushambi, an ancient town some 30 kilometres west of Allahabad that was the capital of the Koshala kingdom, and moved to Allahabad, presumably under Muslim rule.

The pillar is now located inside the Allahabad Fort, also the royal palace, built during the 16th century by Akbar at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers. As the fort is occupied by the Indian Army it is essentially closed to the public and special permission is required to see the pillar. The Ashokan inscription is in Brahmi and is dated around 232 BC. A later inscription attributed to the second king of the Gupta empire, Samudragupta, is in the more refined Gupta script, a later version of Brahmi, and is dated to around 375 AD. This inscription lists the extent of the empire that Samudragupta built during his long reign. He had already been king for forty years at that time and would rule for another five. A still later inscription in Persian is from the Mughal emperor Jahangir. The Akbar Fort also houses the Akshay Vat, an Indian fig tree of great antiquity. The Ramayana refers to this tree under which Lord Rama is supposed to have prayed while on exile.

-- Pillars of Ashoka, by Wikipedia

The fifth and the last Asokan pillar of this class is now standing in the historic fort of Allahabad. According to Fuhrer it was brought by Firuz Shah Tughluq from the ancient town of Kausambi and was re-erected at Prayaga.14 The pillar bears the famous inscriptions of Asoka, Samudragutpa and Jahangir. According to Cunningham the pillar may have been dislodged many a time before it was finally set up by Akbar or by Jahangir whose date of accession is inscribed on it. There are many visitors' name carved on the pillar when it was lying on the ground. Among dated epigraphs there is one date which falls in the reign of Firuz Shah Tughluq.

Conclusion:

Firuz Shah should be given all credit for the discovery and preservation of five Mauryan pillars. It is recorded that the scholars of his time had failed to decipher the Asokan edicts. But it is nowhere mentioned why Firuz attached so much importance to these, otherwise simple monolithic stone pillars. It is also not known why he decided to re-erect these columns inside or in front of mosques. It seems that after the re-erection of the Delhi-Topra pillar some Indian scholar of his time had informed him about some of the purports of the inscriptions.

On the base of the obelisk there were engraved several lines of writing in Hindi characters. Many Brahmans and Hindu devotees were invited to read them, but no one was able. It is said that certain infidel Hindus interpreted them as stating that no one should be able to remove the obelisk from its place till there should arise in the latter days a Muhammadan king, named Sultan Firoz, etc., etc.

-- XVI. Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, of Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, Excerpt from The History of India As Told By Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, edited from the posthumous papers of the Late Sir H.M. Elliot, K.C.B., East India Company's Bengal Civil Service, by Professor John Dowson, M.R.A.S., Staff college, Sandhurst, Vol. III, P. 269-364, 1871

This becomes more probable when we consider that Firuz Shah caused to be inscribed memories (Futuhat-i-Firuz Shahi), i.e. records of his achievements or regulations to be inscribed on the eight sides of the octagonal cupola in the Jami Mosque of Firuzabad, next to the pyramidal structure of the Delhi-Topra pillar. It is also not understood why Firuz erected his inscribed cupola before the Asokan pillar. Moreover one can find many parallels in the Asokan pillar edict of Kotla-Firuz Shah and in the Futuhat which recorded Firuz's regulations, public works love of people, abolition of inhuman punishments. and harsh taxes, foundations of hospitals, colleges, towns, gardens, public baths, minarets, excavation of tanks, wells, construction of bridges, canals, preservation of ancient monuments and books (some of them translated from Sanskrit), extension of cultivation; and attempts of raising the morals of the people.15

[This little work, the production of the Sultan Firoz Shah, contains a brief summary of the res gestae [achievements] of his reign, or, as he designates them, his "Victories." Sir H. Elliot was unable to obtain a copy of it, but considered its recovery very desirable, "as everything relating to the noble character of Firoz is calculated to excite attention." Colonel Lees also speaks of it, but he had never seen it, and was not well informed as to its extent.1 [Journal Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. IV., New Series, p. 446. See also Briggs' Ferishta, I., 462.] Mr. Thomas was more fortunate, for he possesses a copy which purports to have been written in 1139 H. (1726 A.D.), but it is quite modern; the date therefore must be that of the MS. from which it was copied. The work is a mere brochure of thirty-two pages, and the editor has translated the whole of it, with the exception of a few lines in the preface laudatory of the prophet. It exhibits the humane and generous spirit of Firoz in a very pleasing unostentatious light, recording his earnest endeavours to discharge the duties of his station with clemency, and to act up to the teaching of his religion with reverence and earnestness.]

-- XVII. Futuhat-i Firoz Shahi of Sultan Firoz Shah, Excerpt from The History of India As Told By Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, edited from the posthumous papers of the Late Sir H.M. Elliot, K.C.B., East India Company's Bengal Civil Service, by Professor John Dowson, M.R.A.S., Staff college, Sandhurst, Vol. III, P. 374-, 1871

REFERENCES

(1) John Irwin, 'Asokan pillars: A reassessment of the evidence' part-I-III, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. CXVII, CXVII (London, 1975) where a purely subjective hypothesis is built up for tracing the origin of the celebrated pillars to the pre-Mauryan period without giving due consideration to archaeological and epigraphical evidences.

(2) Even in recent works these mistakes have not been corrected.

(3) J. A. Page, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, No. 52, -- A Memoir on Kotla-Firoz Shah (Delhi-1937). It deals with history and archaeological remains of Firuzabad, Firuz Shah's New Delhi and contains second chapters of the Persian text of Sirat-i-Firuz Shahi with its English translation and illustration of original drawings of Delhi-Topra pillar being carried in boat and re-erected in stages on a specially built three storeyed edifice.

(4) Shams Siraj 'Afif, Tarikh-i-Firoz Shahi (Persian Text) pp. 305-314; Sirat-i-Firoz Shahi page, op. cit (Persian) p. 4, where the name of village is given as Maqbulabad alias Topra, which was most probably renamed after the discovery of the Asokan pillar after the name of Malik Maqbul Sullani who was the Minister of Firuz Shah.

(5) See the details in Page, op. cit. pp. 4-5, Alff. op. cit.; Cunningham, Archaeological Survey of India Reports: Vol. I (Reprinted Delhi, 1972) pp. 161-168. Also pl. note that the year of re-erection has not been correctly given elsewhere.

(6) Firuz provided stone railings of Mauryan pattern before the entrance or his Madrasa (college) at Hauz Khas, New Delhi which is still extant. Sikandar Lodi also erected the same type of railings on the platform in front of his tomb at New Delhi.

(7) K. A. Nizami, "The Futuhat i-Firuz as a Medieval Inscription, Proceedings of the Seminar on Medieval Inscriptions (Aligarh, 7974), pp, 28-33, where he compares the text of the Futuhat with the Delhi-Topra Pillar Edicts of Asoka and observes many striking similarities in both the texts.

See Nizami, Khaliq Ahmad (1974). "The Futuhat-i-Firuz Shahi as a medieval inscription". Proceedings of the Seminar on Medieval Inscriptions (6–8th Feb. 1970). Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh: Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University. pp. 28–33. OCLC 3870911. and Nizami, Khaliq Ahmad (1983). On History and Historians of Medieval India. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. pp. 205–210. OCLC 10349790.

(8) Afif op. cit. 124. Also see Sikandar, Mirat-i-Sikandari (Baroda, 1961).

(9) Afif, op. cit.

(10) Afif, op. cit.

(11) Cunningham. op. cit., Vol. V., v. p. 140-142.

(12) Cunningham, op. cit., Vol. V., pp, 140-141.

(13) B. Ch. Chhabra, 'Asokan Pillar at Hissar Punjab,' Vishveshvaranand Indological Journal, (Hoshiapur, 1964 ), e. s.

(14) A. Fuhrer, The Monumental Antiquities and Inscriptions in the North-Western Provinces and Oudh., Arch. Sur. India, New Series, Vol. II. (Allahabad, 1891), p. 128, Cunningham, Arch. Sur. Ind., Four Reports. 1862-63-64-65, Vol. I (Delhi. 1972. ), p. 298.

(15) Nizamud-Din Ahmad, Tabaqat-i-Akbari, (Lucknow, 1875), pp. 150-121; Firishta, Tarikh-i-Firishta (Lucknow, 1905), pp. 150-151, Nizami, op. cit.