Giordano Bruno

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/22/20

11. The Manipulator of Erotic Love:

In this chapter we want to introduce the reader to a spectacular European parallel to the fundamental tantric idea that erotic love and sexuality can be translated into material and spiritual power. It concerns several until now rarely considered theses of Giordano Bruno (1548-1600).

At the age of fifteen, Bruno, born in Nola, Italy, joined the Dominican order. However, his interest in the newest scientific discoveries and his fascination with the late Hellenistic esotericism very soon led him to leave his order, a for the times most courageous undertaking. From this point on he began a hectic life on the road which took him all over Europe. Nonetheless, the restless and ingenious ex-monk wrote and published numerous “revolutionary” works in which he took a critical stance toward the dogmata of the church on all manner of topics. The fact that Bruno championed many ideas from the modern view of the world that was emerging at the time, especially the Copernican system, made him a hero of the new during his own lifetime. After he was found guilty of heresy by the Inquisition in 1600 and burned at the stake at the Campo dei Fiori in Rome, the European intelligentsia proclaimed him to be the greatest “martyr of modern science”. This image has stayed with him up until the present day. Yet this is not entirely justified, then Bruno was far more interested in the esoteric ideas of antiquity and the occultism of his day than in modern scientific research. Nearly all of his works concern magic/mystic/mythological themes.

Like the Indian Tantrics, this eccentric and dynamic Renaissance philosopher was convinced that the entire universe was held together by erotic love. Love in all its variations ruled the world, from physical nature to the metaphysical heavens, from sexuality to heartfelt love of the mystics: it “led either to the animals [sexuality] or to the intelligible and is then called the divine [mysticism]" (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 174).

Bruno extended the term Eros (erotic love) to encompass in the final instance all human emotions and described it in general terms as the primal force which bonded, or rather—as he put it—"chained”, through affect. “The most powerful shackle of all is ... love” (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 224). The lover is “chained” to the individual loved. But there is no need for the reverse to apply, then the beloved does not themselves have to love. This definition of love as a “chain” made it possible for Bruno to see even hate as a way of expressing erotic love, since he or she who hates is just as “chained” to the hated by his feelings as the lover is to the beloved. (To more graphically illustrate the parallels between Bruno’s philosophy and Tantrism, we will in the following speak of the lover as feminine rather than masculine. Bruno used the term completely generically for both women and men.

According to Bruno, “the ability to enchain” is also the main characteristic of magic, then a magician behaves like an escapologist when he binds his “victim” (whether human or spirit) to him with love. “There where we have spoken of natural magic, we have described to what extent all chains can be related to the chain of love, are dependent upon the chain of love or arise in the chain of love” (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 213). More than anything else, love binds people, and this gives it something of the demonic, especially when it is exploited by one partner to the disadvantage of the other. “As regards all those who are dedicated to philosophy or magic, it is fully apparent that the highest bond, the most important and the most general belongs to erotic love: and that is why the Platonists called love the Great Demon, daemon magnus” (quoted by Couliano, 1987, p. 91).

Now how does this erotic magic work? According to Bruno an erotic/magic involvement arises between the lovers, a fabric of affect, feelings, and moods. He refers to this as rete (net or fabric). It is woven from subtle “threads of affect”, but is thus all the more binding. (Let us recall that the Sanskrit word “tantra” translates as “fabric” or “net”.) The rete (the erotic net) can be expressed in a sexual relationship (through sexual dependency), but in the majority of cases it is of a psychological nature which nonetheless further strengthens its power to bind. Every form of love chains in its own way: “This love”, Bruno says, “is unique, and is a fetter which makes everything one” (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 180).

If they wish, a person can control the one whom they bind to themselves with love, since “through this chain [the] lover is enraptured, so that they want to be transferred to the beloved” as Bruno writes (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 181). Accordingly, the real magician is the beloved, who exploits the erotic energy of the lover in the accumulation of his own power. He transforms love into power, he is a manipulator of erotic love. [1] As we shall soon see, even if Bruno’s manipulator is not literally a Tantric, the second part of the definition with which we prefaced our study still seems to fit:The mystery of Tantric Buddhism consists in ...

the manipulation of erotic love

so as to attain universal androcentric power.

The manipulator, also referred to as a “soul hunter” by Bruno, can reach the heart of the lover through her sense of sight, through her hearing, through her spirit, and through her imagination, and thus chain her to him. He can look at her, smile at her, hold her hand, shower her with flattering compliments, sleep with her, or influence her through his power of imagination. “In enchaining”, Bruno says, “there are four movements. The first is the penetration or insertion, the second the attachment or the chain, the third the attraction, the fourth the connection, which is also known as enjoyment. ... Hence [the] lover wants to completely penetrate the beloved with his tongue, his mouth, with his eyes, etc.” (Samsonow, 1995, pp. 171, 200). That is, not only does the lover let herself be enchained, she must also experience the greatest desire for this bond. This lust has to increase to the point that she wants to offer herself with her entire being to the beloved manipulator and would like to “disappear in him”. This gives the latter absolute power over the enchained one.

The manipulator evokes all manner of illusions in the awareness of his love victim and arouses her emotions and desires. He opens the heart of the lover and can take possession of the one thus “wounded”. He is lord over foreign emotions and “has means at his disposal to forge all the chains he wants: hope, compassion, fear, love, hate, indignation, anger, joy, patience, disdain for life and death” writes Joan P. Couliano in her book, Eros and magic in the Renaissance (Couliano, 1987, p. 94). Yet the magically enacted enchainment may never occur against the manifest will of the enchanted one. In contrast, the manipulator must always awake the suggestion in his victim that everything is happening in her interests alone. He creates the total illusion that the lover is a chosen one, an independent individual following her own will.

Bruno also mentions an indirect method of gaining influence, in which the lover does not know at all that she is being manipulated. In this case, the manipulator makes use of “powerful invisible beings, demons and heroes”, whom he conjures up with magic incantations (mantras) so as to achieve the desired result with their help (Couliano, 1987, p. 88). We learn from the following quotation how these invoked spirits work for the manipulator: They need “neither ears nor a voice nor a whisper, rather they penetrate the inner senses [of the lover] as described. Thus they do not just produce dreams and cause voices to be heard and all kinds of things to be seen, but they also force certain thoughts upon the waking as the truth, which they can hardly recognize as deriving from another” (Samsonow, 1995, p. 140). The lover thus believes she is acting in her own interests and according to her own will, whilst she is in fact being steered and controlled through magic blandishments.

The manipulator himself may not surrender to any emotional inclinations. Like a tantric yogi he must keep his own feelings completely under control from start to finish. For this reason well-developed egocentricity is a necessary characteristic for a good manipulator. He is permitted only one love: narcissism (philautia), and according to Bruno only a tiny elite possesses the ability needed, because the majority of people surrender to uncontrolled emotions. The manipulator has to completely bridle and control his fantasy: “Be careful,” Bruno warns him, “not to change yourself from manipulator into the tool of phantasms” (quoted by Couliano, 1987, p. 92). The real European magician must, like his oriental colleague (the Siddha), be able “to arrange, to correct and to provide phantasy, to create the different kinds at will” (Couliano, 1987, p. 92).

He must not develop any reciprocal feelings for the lover, but he has to pretend to have these, since, as Bruno says, “the chains of love, friendship, goodwill, favor, lust, charity, compassion, desire, passion, avarice, craving, and longing disappear easily if they are not based upon mutuality. From this stems the saying: love dies without love” (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 181). This statement is of thoroughly cynical intent, then the manipulator is not interested in reciprocating the erotic love of the lover, but rather in simulating such a reciprocity.

But for the deception to succeed the manipulator may not remain completely cold. He has to know from his own experience the feelings that he evokes in the lover, but he may never surrender himself to these: “He is even supposed to kindle in his phantasmic mechanism [his imagination] formidable passions, provided these be sterile and that he be detached from them. For there is no way to bewitch others than by experimenting in himself with what he wishes to produce in his victim” (Couliano, 1987, p. 102). The evocation of passions without falling prey to them is, as we know, almost a tantric leitmotif.

Yet the most astonishing aspect of Bruno’s manipulation thesis is that, as in Vajrayana, he mentions the retention of semen as a powerful instrument of control which the magician should command, since “through the expulsion of the seed the chains [of love] are loosened, through the retention tightened” (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 175). In a further passage we can read: “If this [the semen virile] is expelled by an appropriate part, the force of the chain is reduced correspondingly (quoted by Samsonow, 1995, p. 175). Or the reverse: a person who retains their semen, can thereby strengthen the erotic bondage of the lover.

Bruno’s idea that there is a correspondence between erotic love and power is thus in accord with tantric dogma on the issue of sperm gnosis as well. His theory of the manipulability of love offers us valuable psychological insights into the soul of the lover and the beloved manipulator. They also help us to understand why women surrender themselves to the Buddhist yogis and what is played out in their emotional worlds during the rites. As we have already indicated, this topic is completely suppressed in the tantric discussion. But Bruno addresses it openly and cynically — it is the heart of the lover which is manipulated. The effect for the manipulator (or yogi) is thus all the greater the more his karma mudra surrenders herself to him.

Bruno’s treatise, De vinculis in genere [On the binding forces in general] (1591), can in terms of its cynicism and directness only be compared with Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513). But his work goes further. Couliano correctly points out that Machiavelli examines political, Bruno however, psychological manipulation. Then it is less the love of a consort and rather the erotic love of the masses which should — this she claims is Bruno’s intention — serve the manipulator as a “chain”. The former monk from Nola recognized manipulated “love” as a powerful instrument of control for the seduction of the masses. His theory thus contributes much to an understanding of the ecstatic attractiveness that dictators and pontiffs exercise over the people who love them. This makes Bruno’s work up to date despite its cynical content.

Bruno’s observations on “erotic love as a chain” are essentially tantric. Like Vajrayana, they concern the manipulation of the erotic in order to produce spiritual and worldly power. Bruno recognized that love in the broadest sense is the “elixir of life”, which first makes possible the establishment and maintenance of institutions of power headed by a person (such as the Pope, the Dalai Lama, or a “beloved” dictator for example). As strong as love may be, it is, if it remains one-sided, manipulable in the person of the “lover”. Indeed, the stronger it becomes, the more easily it can be used or “misused” for the purposes of power (by the “beloved”).

The fact that Tantrism focuses more upon sexuality than on the more sublime forms of erotic love, does not change anything about this principle of “erotic exploitation”. The manipulation of more subtle forms of love like the look (Carya Tantra), the smile (Kriya Tantra), and the touch (Yoga Tantra) are also known in Vajrayana. Likewise, in Tantric Buddhism as in every religious institution, the “spiritual love” of its believers is a life energy without which it could not exist. In the second part of our study we shall have to demonstrate how the Tibetan leader of the Buddhists, the Dalai Lama, succeeds in binding ever more Western believers to him with the “chains of love”.

Incidentally, in her book which we have quoted (Eros and Magic in the Renaissance) Couliano is of the opinion that via the mass media the West has already been woven into such a manipulable “erotic net” (rete). At the end of her analysis of Bruno’s treatise on power she concludes: “And since the relations between individuals are controlled by ‘erotic’ criteria in the widest sense of that adjective, human society at all levels is itself only magic at work. Without even being conscious of it, all beings who, by reason of the way the world is constructed, find themselves in an intersubjective intermediate place, participate in a magic process. The manipulator is the only one who, having understood the ensemble of that mechanism, is first an observer of intersubjective relations while simultaneously gaining knowledge from which he means subsequently to profit” (Couliano, 1987, p. 103).

-- The Shadow of the Dalai Lama: Sexuality, Magic and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, by Victor and Victoria Trimondi

Giordano Bruno

Modern portrait based on a woodcut from "Livre du recteur", 1578

Born: Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548, Nola, Kingdom of Naples

Died: 17 February 1600 (aged 51–52), Rome, Papal States

Cause of death: Execution by burning

Era: Renaissance philosophy

Region: Western philosophy

School: Renaissance humanism; Neoplatonism; Neopythagoreanism

Main interests: Philosophy, cosmology, and mathematics

Notable ideas: Cosmic pluralism

Influences: Averroes,[1] Nicolaus Copernicus, Nicolaus Cusanus

Influenced: Galileo Galilei, James Joyce, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Molière,[2] Arthur Schopenhauer, Baruch Spinoza

Giordano Bruno (/dʒɔːrˈdɑːnoʊ ˈbruːnoʊ/, Italian: [dʒorˈdaːno ˈbruːno]; Latin: Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, mathematician, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist.[3][4] He is known for his cosmological theories, which conceptually extended the then-novel Copernican model. He proposed that the stars were distant suns surrounded by their own planets, and he raised the possibility that these planets might foster life of their own, a philosophical position known as cosmic pluralism. He also insisted that the universe is infinite and could have no "centre".

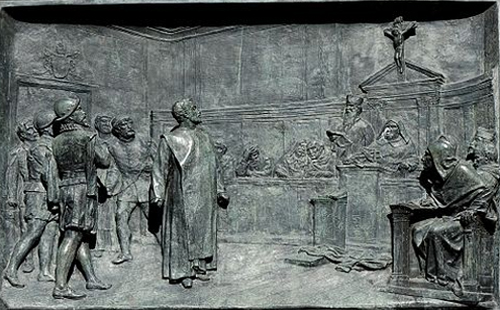

Starting in 1593, Bruno was tried for heresy by the Roman Inquisition on charges of denial of several core Catholic doctrines, including eternal damnation, the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, the virginity of Mary, and transubstantiation. Bruno's pantheism was not taken lightly by the church,[5] as was his teaching of the transmigration of the soul/reincarnation. The Inquisition found him guilty, and he was burned at the stake in Rome's Campo de' Fiori in 1600. After his death, he gained considerable fame, being particularly celebrated by 19th- and early 20th-century commentators who regarded him as a martyr for science,[6] although historians agree that his heresy trial was not a response to his astronomical views but rather a response to his philosophical and religious views.[7][8][9][10][11] Bruno's case is still considered a landmark in the history of free thought and the emerging sciences.[12][13]

In addition to cosmology, Bruno also wrote extensively on the art of memory, a loosely organised group of mnemonic techniques and principles. Historian Frances Yates argues that Bruno was deeply influenced by Arab astrology (particularly the philosophy of Averroes[14]), Neoplatonism, Renaissance Hermeticism, and Genesis-like legends surrounding the Egyptian god Thoth.[15] Other studies of Bruno have focused on his qualitative approach to mathematics and his application of the spatial concepts of geometry to language.[16]

Life

Early years, 1548–1576

Born Filippo Bruno in Nola (a comune in the modern-day province of Naples, in the Southern Italian region of Campania, then part of the Kingdom of Naples) in 1548, he was the son of Giovanni Bruno, a soldier, and Fraulissa Savolino. In his youth he was sent to Naples to be educated. He was tutored privately at the Augustinian monastery there, and attended public lectures at the Studium Generale.[17] At the age of 17, he entered the Dominican Order at the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore in Naples, taking the name Giordano, after Giordano Crispo, his metaphysics tutor. He continued his studies there, completing his novitiate, and became an ordained priest in 1572 at age 24. During his time in Naples he became known for his skill with the art of memory and on one occasion travelled to Rome to demonstrate his mnemonic system before Pope Pius V and Cardinal Rebiba. In his later years Bruno claimed that the Pope accepted his dedication to him of the lost work On The Ark of Noah at this time.[18]

While Bruno was distinguished for outstanding ability, his taste for free thinking and forbidden books soon caused him difficulties. Given the controversy he caused in later life it is surprising that he was able to remain within the monastic system for eleven years. In his testimony to Venetian inquisitors during his trial, many years later, he says that proceedings were twice taken against him for having cast away images of the saints, retaining only a crucifix, and for having recommended controversial texts to a novice.[19] Such behaviour could perhaps be overlooked, but Bruno's situation became much more serious when he was reported to have defended the Arian heresy, and when a copy of the banned writings of Erasmus, annotated by him, was discovered hidden in the convent privy. When he learned that an indictment was being prepared against him in Naples he fled, shedding his religious habit, at least for a time.[20]

First years of wandering, 1576–1583

Bruno first went to the Genoese port of Noli, then to Savona, Turin and finally to Venice, where he published his lost work On the Signs of the Times with the permission (so he claimed at his trial) of the Dominican Remigio Nannini Fiorentino. From Venice he went to Padua, where he met fellow Dominicans who convinced him to wear his religious habit again. From Padua he went to Bergamo and then across the Alps to Chambéry and Lyon. His movements after this time are obscure.[21]

The earliest depiction of Bruno is an engraving published in 1715 in Germany, presumed based on a lost contemporary portrait.[22]

In 1579 he arrived in Geneva. As D.W. Singer, a Bruno biographer, notes, "The question has sometimes been raised as to whether Bruno became a Protestant, but it is intrinsically most unlikely that he accepted membership in Calvin's communion"[23] During his Venetian trial he told inquisitors that while in Geneva he told the Marchese de Vico of Naples, who was notable for helping Italian refugees in Geneva, "I did not intend to adopt the religion of the city. I desired to stay there only that I might live at liberty and in security."[This quote needs a citation] Bruno had a pair of breeches made for himself, and the Marchese and others apparently made Bruno a gift of a sword, hat, cape and other necessities for dressing himself; in such clothing Bruno could no longer be recognised as a priest. Things apparently went well for Bruno for a time, as he entered his name in the Rector's Book of the University of Geneva in May 1579.[citation needed] But in keeping with his personality he could not long remain silent. In August he published an attack on the work of Antoine de la Faye [fr], a distinguished professor. He and the printer were promptly arrested. Rather than apologising, Bruno insisted on continuing to defend his publication. He was refused the right to take sacrament. Though this right was eventually restored, he left Geneva.[citation needed]

He went to France, arriving first in Lyon, and thereafter settling for a time (1580–1581) in Toulouse, where he took his doctorate in theology and was elected by students to lecture in philosophy. It seems he also attempted at this time to return to Catholicism, but was denied absolution by the Jesuit priest he approached.[citation needed] When religious strife broke out in the summer of 1581, he moved to Paris. There he held a cycle of thirty lectures on theological topics and also began to gain fame for his prodigious memory. Bruno's feats of memory were based, at least in part, on his elaborate system of mnemonics, but some of his contemporaries found it easier to attribute them to magical powers.[citation needed] His talents attracted the benevolent attention of the king Henry III. The king summoned him to the court. Bruno subsequently reported

"I got me such a name that King Henry III summoned me one day to discover from me if the memory which I possessed was natural or acquired by magic art. I satisfied him that it did not come from sorcery but from organised knowledge; and, following this, I got a book on memory printed, entitled The Shadows of Ideas, which I dedicated to His Majesty. Forthwith he gave me an Extraordinary Lectureship with a salary."[24]

In Paris, Bruno enjoyed the protection of his powerful French patrons. During this period, he published several works on mnemonics, including De umbris idearum (On the Shadows of Ideas, 1582), Ars Memoriae (The Art of Memory, 1582), and Cantus Circaeus (Circe's Song, 1582). All of these were based on his mnemonic models of organised knowledge and experience, as opposed to the simplistic logic-based mnemonic techniques of Petrus Ramus then becoming popular.[citation needed] Bruno also published a comedy summarizing some of his philosophical positions, titled Il Candelaio (The Torchbearer, 1582). In the 16th century dedications were, as a rule, approved beforehand, and hence were a way of placing a work under the protection of an individual. Given that Bruno dedicated various works to the likes of King Henry III, Sir Philip Sidney, Michel de Castelnau (French Ambassador to England), and possibly Pope Pius V, it is apparent that this wanderer had risen sharply in status and moved in powerful circles.[citation needed]

England, 1583–1585

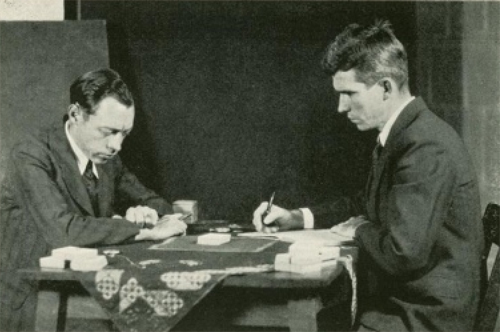

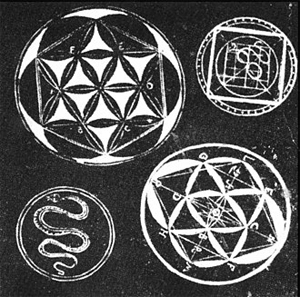

Woodcut illustration of one of Giordano Bruno's less complex mnemonic devices

In April 1583, Bruno went to England with letters of recommendation from Henry III as a guest of the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau. There he became acquainted with the poet Philip Sidney (to whom he dedicated two books) and other members of the Hermetic circle around John Dee, though there is no evidence that Bruno ever met Dee himself. He also lectured at Oxford, and unsuccessfully sought a teaching position there. His views were controversial, notably with John Underhill, Rector of Lincoln College and subsequently bishop of Oxford, and George Abbot, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. Abbot mocked Bruno for supporting "the opinion of Copernicus that the earth did go round, and the heavens did stand still; whereas in truth it was his own head which rather did run round, and his brains did not stand still",[25] and found Bruno had both plagiarised and misrepresented Ficino's work, leading Bruno to return to the continent.[26]

Nevertheless, his stay in England was fruitful. During that time Bruno completed and published some of his most important works, the six "Italian Dialogues", including the cosmological tracts La Cena de le Ceneri (The Ash Wednesday Supper, 1584), De la Causa, Principio et Uno (On Cause, Principle and Unity, 1584), De l'Infinito, Universo e Mondi (On the Infinite, Universe and Worlds, 1584) as well as Lo Spaccio de la Bestia Trionfante (The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast, 1584) and De gl' Heroici Furori (On the Heroic Frenzies, 1585). Some of these were printed by John Charlewood. Some of the works that Bruno published in London, notably The Ash Wednesday Supper, appear to have given offense. Once again, Bruno's controversial views and tactless language lost him the support of his friends. John Bossy has advanced the theory that, while staying in the French Embassy in London, Bruno was also spying on Catholic conspirators, under the pseudonym "Henry Fagot", for Sir Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth's Secretary of State.[27]

Bruno is sometimes cited as being the first to propose that the universe is infinite, which he did during his time in England, but an English scientist, Thomas Digges, put forth this idea in a published work in 1576, some eight years earlier than Bruno.[28] An infinite universe and the possibility of alien life had also been earlier suggested by German Catholic Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa in "On Learned Ignorance" published in 1440.

Last years of wandering, 1585–1592

In October 1585, after the French embassy in London was attacked by a mob, Bruno returned to Paris with Castelnau, finding a tense political situation. Moreover, his 120 theses against Aristotelian natural science and his pamphlets against the mathematician Fabrizio Mordente soon put him in ill favour. In 1586, following a violent quarrel about Mordente's invention, the differential compass, he left France for Germany.[citation needed]

Woodcut from "Articuli centum et sexaginta adversus huius tempestatis mathematicos atque philosophos", Prague 1588

In Germany he failed to obtain a teaching position at Marburg, but was granted permission to teach at Wittenberg, where he lectured on Aristotle for two years. However, with a change of intellectual climate there, he was no longer welcome, and went in 1588 to Prague, where he obtained 300 taler from Rudolf II, but no teaching position. He went on to serve briefly as a professor in Helmstedt, but had to flee again when he was excommunicated by the Lutherans.[citation needed]

During this period he produced several Latin works, dictated to his friend and secretary Girolamo Besler, including De Magia (On Magic), Theses De Magia (Theses on Magic) and De Vinculis in Genere (A General Account of Bonding). All these were apparently transcribed or recorded by Besler (or Bisler) between 1589 and 1590.[29] He also published De Imaginum, Signorum, Et Idearum Compositione (On the Composition of Images, Signs and Ideas, 1591).

In 1591 he was in Frankfurt. Apparently, during the Frankfurt Book Fair,[30] he received an invitation to Venice from the local patrician Giovanni Mocenigo, who wished to be instructed in the art of memory, and also heard of a vacant chair in mathematics at the University of Padua. At the time the Inquisition seemed to be losing some of its strictness, and because the Republic of Venice was the most liberal state in the Italian Peninsula, Bruno was lulled into making the fatal mistake of returning to Italy.[31]

He went first to Padua, where he taught briefly, and applied unsuccessfully for the chair of mathematics, which was given instead to Galileo Galilei one year later. Bruno accepted Mocenigo's invitation and moved to Venice in March 1592. For about two months he served as an in-house tutor to Mocenigo. When Bruno announced his plan to leave Venice to his host, the latter, who was unhappy with the teachings he had received and had apparently come to dislike Bruno, denounced him to the Venetian Inquisition, which had Bruno arrested on 22 May 1592. Among the numerous charges of blasphemy and heresy brought against him in Venice, based on Mocenigo's denunciation, was his belief in the plurality of worlds, as well as accusations of personal misconduct. Bruno defended himself skilfully, stressing the philosophical character of some of his positions, denying others and admitting that he had had doubts on some matters of dogma. The Roman Inquisition, however, asked for his transfer to Rome. After several months of argument, the Venetian authorities reluctantly consented and Bruno was sent to Rome in February 1593.[citation needed]

Imprisonment, trial and execution, 1593–1600

During the seven years of his trial in Rome, Bruno was held in confinement, lastly in the Tower of Nona. Some important documents about the trial are lost, but others have been preserved, among them a summary of the proceedings that was rediscovered in 1940.[32] The numerous charges against Bruno, based on some of his books as well as on witness accounts, included blasphemy, immoral conduct, and heresy in matters of dogmatic theology, and involved some of the basic doctrines of his philosophy and cosmology. Luigi Firpo speculates the charges made against Bruno by the Roman Inquisition were:[33]

• holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith and speaking against it and its ministers;

• holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about the Trinity, divinity of Christ, and Incarnation;

• holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith pertaining to Jesus as Christ;

• holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith regarding the virginity of Mary, mother of Jesus;

• holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about both Transubstantiation and Mass;

• claiming the existence of a plurality of worlds and their eternity;

• believing in metempsychosis and in the transmigration of the human soul into brutes;

• dealing in magics and divination.

The trial of Giordano Bruno by the Roman Inquisition. Bronze relief by Ettore Ferrari, Campo de' Fiori, Rome.

Bruno defended himself as he had in Venice, insisting that he accepted the Church's dogmatic teachings, but

trying to preserve the basis of his philosophy. In particular, he held firm to his belief in the plurality of worlds, although he was admonished to abandon it. His trial was overseen by the Inquisitor Cardinal Bellarmine, who demanded a full recantation, which Bruno eventually refused. On 20 January 1600, Pope Clement VIII declared Bruno a heretic, and the Inquisition issued a sentence of death. According to the correspondence of Gaspar Schopp of Breslau, he is said to have made a threatening gesture towards his judges and to have replied: Maiori forsan cum timore sententiam in me fertis quam ego accipiam ("Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it").[34]

He was turned over to the secular authorities. On Ash Wednesday, 17 February 1600, in the Campo de' Fiori (a central Roman market square), with his "tongue imprisoned because of his wicked words", he was hung upside down naked before finally being burned at the stake.[35][36] His ashes were thrown into the Tiber river. All of Bruno's works were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1603. The inquisition cardinals who judged Giordano Bruno were Cardinal Bellarmino (Bellarmine), Cardinal Madruzzo (Madruzzi), Camillo Cardinal Borghese (later Pope Paul V), Domenico Cardinal Pinelli, Pompeio Cardinal Arrigoni, Cardinal Sfondrati, Pedro Cardinal De Deza Manuel and Cardinal Santorio (Archbishop of Santa Severina, Cardinal-Bishop of Palestrina).

The measures taken to prevent Bruno continuing to speak have resulted in his becoming a symbol for free thought and speech in present-day Rome, where an annual memorial service takes place close to the spot where he was executed.[37]

Physical appearance

The earliest likeness of Bruno is an engraving published in 1715[38] and cited by Salvestrini as "the only known portrait of Bruno". Salvestrini suggests that it is a re-engraving made from a now lost original.[22] This engraving has provided the source for later images.

The records of Bruno's imprisonment by the Venetian inquisition in May 1592 describe him as a man "of average height, with a hazel-coloured beard and the appearance of being about forty years of age". Alternately, a passage in a work by George Abbot indicates that Bruno was of diminutive stature: "When that Italian Didapper, who intituled himselfe Philotheus Iordanus Brunus Nolanus, magis elaboratae Theologiae Doctor, &c. with a name longer than his body...".[39] The word "didapper" used by Abbot is the derisive term which at the time meant "a small diving waterfowl".[40]

Cosmology

Contemporary cosmological beliefs

See also: Celestial spheres § History

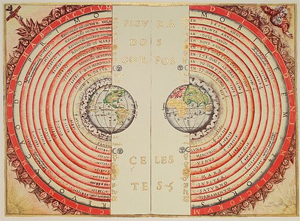

Illuminated illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric conception of the universe. The outermost text reads "The heavenly empire, dwelling of God and all the selected"

In the first half of the 15th century, Nicholas of Cusa challenged the then widely accepted philosophies of Aristotelianism, envisioning instead an infinite universe whose centre was everywhere and circumference nowhere, and moreover teeming with countless stars.[41] He also predicted that neither were the rotational orbits circular nor were their movements uniform.[42]

In the second half of the 16th century, the theories of Copernicus (1473–1543) began diffusing through Europe. Copernicus conserved the idea of planets fixed to solid spheres, but considered the apparent motion of the stars to be an illusion caused by the rotation of the Earth on its axis; he also preserved the notion of an immobile centre, but it was the Sun rather than the Earth. Copernicus also argued the Earth was a planet orbiting the Sun once every year. However he maintained the Ptolemaic hypothesis that the orbits of the planets were composed of perfect circles—deferents and epicycles—and that the stars were fixed on a stationary outer sphere.[43]

Despite the widespread publication of Copernicus' work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, during Bruno's time most educated Catholics subscribed to the Aristotelian geocentric view that the Earth was the centre of the universe, and that all heavenly bodies revolved around it.[44] The ultimate limit of the universe was the primum mobile, whose diurnal rotation was conferred upon it by a transcendental God, not part of the universe (although, as the kingdom of heaven, adjacent to it[45]), a motionless prime mover and first cause. The fixed stars were part of this celestial sphere, all at the same fixed distance from the immobile Earth at the center of the sphere. Ptolemy had numbered these at 1,022, grouped into 48 constellations. The planets were each fixed to a transparent sphere.[46]

Few astronomers of Bruno's time accepted Copernicus's heliocentric model. Among those who did were the Germans Michael Maestlin (1550–1631), Christoph Rothmann, Johannes Kepler (1571–1630); the Englishman Thomas Digges, author of A Perfit Description of the Caelestial Orbes; and the Italian Galileo Galilei (1564–1642).

Bruno's cosmological claims

In 1584, Bruno published two important philosophical dialogues (La Cena de le Ceneri and De l'infinito universo et mondi) in which he argued against the planetary spheres (Christoph Rothmann did the same in 1586 as did Tycho Brahe in 1587) and affirmed the Copernican principle.

In particular, to support the Copernican view and oppose the objection according to which the motion of the Earth would be perceived by means of the motion of winds, clouds etc., in La Cena de le Ceneri Bruno anticipates some of the arguments of Galilei on the relativity principle.[47] Note that he also uses the example now known as Galileo's ship.

Theophilus – [...] air through which the clouds and winds move are parts of the Earth, [...] to mean under the name of Earth the whole machinery and the entire animated part, which consists of dissimilar parts; so that the rivers, the rocks, the seas, the whole vaporous and turbulent air, which is enclosed within the highest mountains, should belong to the Earth as its members, just as the air [does] in the lungs and in other cavities of animals by which they breathe, widen their arteries, and other similar effects necessary for life are performed. The clouds, too, move through accidents in the body of the Earth and are in its bowels as are the waters. [...] With the Earth move [...] all things that are on the Earth. If, therefore, from a point outside the Earth something were thrown upon the Earth, it would lose, because of the latter's motion, its straightness as would be seen on the ship [...] moving along a river, if someone on point C of the riverbank were to throw a stone along a straight line, and would see the stone miss its target by the amount of the velocity of the ship's motion. But if someone were placed high on the mast of that ship, move as it may however fast, he would not miss his target at all, so that the stone or some other heavy thing thrown downward would not come along a straight line from the point E which is at the top of the mast, or cage, to the point D which is at the bottom of the mast, or at some point in the bowels and body of the ship. Thus, if from the point D to the point E someone who is inside the ship would throw a stone straight up, it would return to the bottom along the same line however far the ship moved, provided it was not subject to any pitch and roll."[48]

Bruno's infinite universe was filled with a substance—a "pure air", aether, or spiritus—that offered no resistance to the heavenly bodies which, in Bruno's view, rather than being fixed, moved under their own impetus (momentum). Most dramatically, he completely abandoned the idea of a hierarchical universe.

The universe is then one, infinite, immobile.... It is not capable of comprehension and therefore is endless and limitless, and to that extent infinite and indeterminable, and consequently immobile.[49]

Bruno's cosmology distinguishes between "suns" which produce their own light and heat, and have other bodies moving around them; and "earths" which move around suns and receive light and heat from them.[50] Bruno suggested that some, if not all, of the objects classically known as fixed stars are in fact suns.[50] According to astrophysicist Steven Soter, he was the first person to grasp that "stars are other suns with their own planets."[51]

Bruno wrote that other worlds "have no less virtue nor a nature different from that of our Earth" and, like Earth, "contain animals and inhabitants".[52]

During the late 16th century, and throughout the 17th century, Bruno's ideas were held up for ridicule, debate, or inspiration. Margaret Cavendish, for example, wrote an entire series of poems against "atoms" and "infinite worlds" in Poems and Fancies in 1664. Bruno's true, if partial, vindication would have to wait for the implications and impact of Newtonian cosmology.[53] Bruno's overall contribution to the birth of modern science is still controversial. Some scholars follow Frances Yates stressing the importance of Bruno's ideas about the universe being infinite and lacking geocentric structure as a crucial crossing point between the old and the new. Others see in Bruno's idea of multiple worlds instantiating the infinite possibilities of a pristine, indivisible One,[54] a forerunner of Everett's many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.[55]

While many academics note Bruno's theological position as pantheism, several have described it as pandeism, and some also as panentheism.[56][57] Physicist and philosopher Max Bernhard Weinstein in his Welt- und Lebensanschauungen, Hervorgegangen aus Religion, Philosophie und Naturerkenntnis ("World and Life Views, Emerging From Religion, Philosophy and Nature"), wrote that the theological model of pandeism was strongly expressed in the teachings of Bruno, especially with respect to the vision of a deity for which "the concept of God is not separated from that of the universe."[58] However, Otto Kern takes exception to what he considers Weinstein's overbroad assertions that Bruno, as well as other historical philosophers such as John Scotus Eriugena, Anselm of Canterbury, Nicholas of Cusa, Mendelssohn, and Lessing, were pandeists or leaned towards pandeism.[59] Discover editor Corey S. Powell also described Bruno's cosmology as pandeistic, writing that it was "a tool for advancing an animist or Pandeist theology",[60] and this assessment of Bruno as a pandeist was agreed with by science writer Michael Newton Keas,[61] and The Daily Beast writer David Sessions.[62]

Retrospective views of Bruno

The monument to Bruno in the place he was executed, Campo de' Fiori in Rome

Monument to Giordano Bruno at Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, Germany, referencing his burning at the stake while tied upside down.