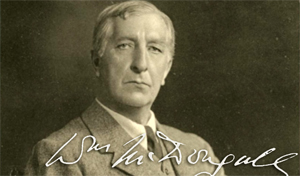

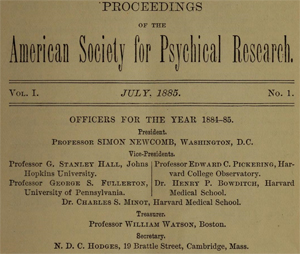

Henry Sidgwick

by Barton Schultz

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

First published Tue Oct 5, 2004; substantive revision Tue Jul 9, 2019

Copyright © 2019 by Barton Schultz <[email protected]>

Henry Sidgwick was one of the most influential ethical philosophers of the Victorian era, and his work continues to exert a powerful influence on Anglo-American ethical and political theory, with an increasing global impact as well. His masterpiece, The Methods of Ethics was first published in 1874 (seventh edition: 1907) and in many ways marked the culmination of the classical utilitarian tradition—the tradition of Jeremy Bentham and James and John Stuart Mill—with its emphasis on “the greatest happiness of the greatest number” as the fundamental normative demand. Sidgwick’s treatment of that position was more comprehensive and scholarly than any previous one, and he set the agenda for most of the twentieth-century debates between utilitarians and their critics. Utilitarians and consequentialists from G. E. Moore and Bertrand Russell to J. J. C. Smart and R. M. Hare down to Derek Parfit, Peter Singer and Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek have acknowledged Sidgwick’s Methods as a vital source for their arguments. But in addition to authoritatively formulating utilitarianism and inspiring utilitarians and their sympathizers, the Methods has also served as a general model for how to do ethical theory, since it provides a series of systematic, historically informed comparisons between utilitarianism and its leading alternatives.

Even such influential critics of utilitarianism as William Frankena, Marcus Singer, and John Rawls have looked to Sidgwick’s work for guidance. C. D. Broad, a later successor to Sidgwick’s Cambridge chair, famously went so far as to say “Sidgwick’s Methods of Ethics seems to me to be on the whole the best treatise on moral theory that has ever been written, and to be one of the English philosophical classics” (Broad 1930: 143). In recent years, Broad’s assessment has been endorsed by an increasing number of prominent philosophers (Parfit 2011; de Lazari-Radek & Singer 2014; and Crisp 2015). Engaging with Sidgwick’s work remains an excellent way to cultivate a serious philosophical interest in ethics, metaethics, and practical ethics, not to mention the history of these subjects. Moreover, he made important contributions to many other fields, including economics, political theory, classics, educational theory, and parapsychology. His significance as an intellectual and cultural figure has yet to be fully appreciated, but recent years have witnessed an impressive expansion of Sidgwick studies, and he has even been featured in popular novels (Cohen 2010; Entwistle 2014).

1. Life and Background

Sidgwick was born on May 31, 1838, in the small Yorkshire town of Skipton. The extended Sidgwick family was well-known in the area and quite prosperous, with their cotton-spinning mills representing the oldest manufacturing firms in the town (Dawson 1882, Schultz 2017). But Henry was the second surviving son of Mary Crofts and the Reverend William Sidgwick, the headmaster of the grammar school in Skipton, who died when Henry was only three. Henry’s older brother William went on to become an Oxford don, as did his younger brother Arthur. His sister Mary, known as Minnie, ended up marrying a second cousin, Edward White Benson, who in addition to being an early mentor of Henry’s (and Rugby master) went on to become the archbishop of Canterbury. The Sidgwick and Benson families would contribute much to English letters and science over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, though their legacies have also been controversial on some counts (Askwith 1971; Schultz 2004, 2017; Bolt 2011; and Goldhill 2016).

Henry was educated at Rugby and at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he took his degree in 1859. As an undergraduate, he excelled at both mathematics and, especially, classics, in due course becoming Craven Scholar, 33rd Wrangler, and Senior Classic, also winning the Chancellor’s Medal. He wound up staying at Cambridge his entire life, first, beginning in October of 1859, as a Fellow of Trinity and a lecturer in classics—a position that in the later sixties evolved into a lectureship in the moral sciences—then, from 1875, as praelector in moral and political philosophy, and finally, from 1883, as Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy. He resigned his Fellowship in 1869 because he could no longer subscribe in good conscience to the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England, as the position required. This act helped inspire the successful opposition to such requirements. In 1881 he was elected an honorary Fellow, and in 1885, he regained a full Fellowship, remarking on the changing times: “Last time I swore that I would drive away strange doctrine; this time I only pledged myself to restore any College property that might be in my possession when I ceased to be a Fellow” (Sidgwick and Sidgwick, 1906: 400).

Sidgwick’s Cambridge career was rich in reformist activity (Rothblatt 1968; Harvie 1976; and Todd 1999). As an undergraduate, he had been elected to the “Apostles,” the secret Cambridge discussion society that did much to shape the intellectual direction of modern Cambridge; Sidgwick’s allegiance to this group was a very significant feature of his life and work (Lubenow 1998). The 1860s, which he described as his years of “Storm and Stress” over his religious views and commitments, were also the years in which his identity as an academic liberal took shape, and he got caught up in a range of causes emphasizing better and broader educational opportunities, increased professionalism, and greater religious freedom. He evolved into an educational reformer committed to downplaying the influence of classics, introducing modern subjects, and opening up higher education to women. Much influenced by the writings of F. D. Maurice and J. S. Mill, he would become one of the leading proponents of higher education for women and play a guiding role in the foundation of Newnham College, Cambridge, one of the first colleges for women in England (Tullberg [1975], 1998, and Sutherland 2006). He was also active in the cause of university reorganization generally, in due course serving on the General Board of Studies, the Special Board for Moral Sciences, and the Indian Civil Service Board, and he worked tirelessly to expand educational opportunities and professionalize educational efforts through such vehicles as correspondence courses, extension lectures, the Cambridge Working Men’s College, and the University Day Training College for teachers (initiated by Oscar Browning). Such educational reforms were, he held, also of political value in overcoming class conflict and social strife. But Sidgwick’s broader political commitments, which ranged from academic liberal to Liberal Unionist—he joined the breakaway faction of the Liberal Party opposing Gladstone’s policy of Home Rule for Ireland—to independent, were complex and shifting; he was not, alas, always able to rise above the marked imperialistic and orientalist tendencies of the late Victorian era (Schultz 2004, 2007; and Bell 2007, 2016).

In 1876 Sidgwick married Eleanor Mildred Balfour, the sister of his former student, Arthur Balfour, the future prime minister. An accomplished and independent woman with serious scientific interests—she collaborated with her brother-in-law Lord Rayleigh on many scientific papers—Eleanor Sidgwick worked as an equal partner with her husband on many fronts, particularly higher education for women and parapsychology. She eventually took over as Principal of Newnham in 1892, and was for many decades a mainstay of the Society for Psychical Research, an organization that Henry had helped to found (in 1882) and several times headed, though his interest in the paranormal had been evident long before. The Sidgwicks hoped that their psychical research might ultimately support some core religious claims, particularly concerning the personal survival of physical death, which they deemed a vital support for morality. Their extensive and often quite methodologically sophisticated investigations were not as conclusive as they had hoped, but following Henry’s death from cancer on August 28, 1900, Eleanor did become persuaded that he had succeeded in communicating from “the other world.” The Sidgwicks’ work in this field continues to this day to be debated by academic parapsychologists (Gauld 1968, and Braude 2003).

Although Sidgwick published extensively in his lifetime, he is best known for his first major book, The Methods of Ethics, which first appeared in 1874 and went through five editions during his lifetime. His second most widely read book would be his Outlines of the History of Ethics for English Readers, which appeared in 1886 as an expanded version of the article on the subject that he had contributed to the famous ninth edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. But he also published The Principles of Political Economy (1883), The Elements of Politics (1891), and Practical Ethics, A Collection of Addresses and Essays (1898), and after his death, Eleanor Sidgwick worked with various of his former colleagues to bring out Lectures on the Ethics of T. H. Green, H. Spencer, and J. Martineau (1902), Philosophy, Its Scope and Relations (1902), The Development of European Polity (1903), Miscellaneous Essays and Addresses (1904), Lectures on the Philosophy of Kant and Other Philosophical Lectures and Essays (1905), and Henry Sidgwick, A Memoir (1906), which Eleanor and Arthur Sidgwick assembled largely from his correspondence and journal. These posthumous works are typically quite polished and shed a great deal of light on the works that Sidgwick himself saw through publication (Schneewind 1977).

As Sidgwick’s publications attest, he was not only a pre-eminent moral philosopher, with sophisticated views on both going controversies in ethics and metaethics and the history of these subjects, but also an accomplished epistemologist, classicist, economist, political theorist, political historian, literary critic, parapsychologist, and educational theorist. If he was a founder of the Cambridge school of philosophy, he was also a founder of the Cambridge school of economics (along with his colleague and sometimes nemesis Alfred Marshall) and of the Cambridge school of political theory (along with such colleagues as Browning and Sir John Seeley). If such students as Moore and Russell owed him much, so too did such students and admirers as Balfour, J. N. Keynes, F. W. Maitland, F. Y. Edgeworth, James Ward, Frank Podmore, and E. E. Constance Jones. He had serious interests in many areas of philosophy and theology, and also wrote insightfully about poetry and literature, two of his great loves (at Newnham, he lectured on Shakespeare, along with such subjects as philosophy and economics). Indeed, Sidgwick was a force in the larger cultural developments of his age, active in such influential discussion societies as the Metaphysical Society and the Synthetic Society. His friends included George Eliot, T. H. Green, James Bryce, H. G. Dakyns, Roden Noel, and, of special importance, John Addington Symonds, the erudite cultural historian, poet, and man of letters who was a pioneer in the serious historical study of same sex love (Schultz 2004). Sidgwick’s versatile and many-sided intellect—not to mention his keen wit—are typically better displayed in his essays and letters than in his best-known academic books. He was in fact much loved for his gentle humor (or “Sidgwickedness”) and sympathetic conversation, and his philosophical students prized him for his candor. As Balfour put it: “Of all the men I have known he was the readiest to consider every controversy and every controversialist on their merits. He never claimed authority; he never sought to impose his views; he never argued for victory; he never evaded an issue.” (Sidgwick and Sidgwick, 1906: 311).

2. The Methods Of Ethics And Philosophy

2.1 Preliminaries

Sidgwick’s Methods was long in the making. His correspondence with his close friend H. G. Dakyns, a Clifton master who had been a private tutor for the Tennyson family, reveals how long and volatile the development of his ethical views was, particularly during the 1860s when he was working himself free of Anglican orthodoxy. As early as 1862, he wrote to Dakyns that he was “revolving a Theory of Ethics” and working on “a reconciliation between the moral sense and utilitarian theories” (Sidgwick and Sidgwick, 1906: 75). He started telling people that he was “engaged on a Great Work,” which would indeed turn out to be the case. By 1867, much of the basic intellectual structure of the Methods was clearly in place; according to Marshall, at the faculty discussion group known as the “Grote Club,” Sidgwick “read a long & general sketch of the various systems of morality: I. Absolute right II. Make yourself noble III. Make yourself happy IV Increase the general happiness. In the course of it he committed himself to the statement that without appreciating the effect of our action on the happiness of ourselves or of others we could have no idea of right & wrong” (quoted in Schultz 2004: 142).

It was also in 1867 that Sidgwick sent a draft of his pamphlet on “The Ethics of Conformity and Subscription” to J. S. Mill, inviting comments. This work, part of his efforts with the Free Christian Union (an organization for promoting free and open religious inquiry), reflected his casuistical struggles over whether he had a right to keep his Fellowship, given his increasingly Theistic views. He had been increasingly drawn to Theism, which then, as now, stressed that “God’s will and purpose, and God’s assurance of an ultimate fulfilment, are behind all that is happening” (Polkinghorne 1998: 114), but without the orthodox commitments to belief in the Trinity, miracles, eternal punishment, etc.. As Sidgwick explained to his sister: “I have written a pamphlet … on the text ‘Let every man be fully persuaded in his own mind.’ That is really the gist of the pamphlet—that if the preachers of religion wish to retain their hold over educated men they must show in their utterances on sacred occasions the same sincerity, exactness, unreserve, that men of science show in expounding the laws of nature. I do not think that much good is to be done by saying this, but I want to liberate my soul, and then ever after hold my peace” (Sidgwick and Sidgwick, 1906: 226). As he put it in the pamphlet, which appeared in 1870:

What theology has to learn from the predominant studies of the age is something very different from advice as to its method or estimates of its utility; it is the imperative necessity of accepting unreservedly the conditions of life under which these studies live and flourish. It is sometimes said that we live in an age that rejects authority. The statement, thus qualified, seems misleading; probably there never was a time when the number of beliefs held by each individual, undemonstrated and unverified by himself, was greater. But it is true that we only accept authority of a particular sort; the authority, namely, that is formed and maintained by the unconstrained agreement of individual thinkers, each of whom we believe to be seeking truth with single-mindedness and sincerity, and declaring what he has found with scrupulous veracity, and the greatest attainable exactness and precision. (Sidgwick 1870: 14–15).

This was a vision of inquiry and even culture that Sidgwick would promote throughout his life (Schultz 2004, 2011, 2017), though after this point he no longer openly directed his criticisms at the church. Mill had replied to his effort to address the question of subscription on “objective” and “utilitarian” grounds: “What ought to be the exceptions … to the general duty of truth? This large question has never yet been treated in a way at once rational and comprehensive, partly because people have been afraid to meddle with it, and partly because mankind have never yet generally admitted that the effect which actions tend to produce on human happiness is what constitutes them right or wrong” (quoted in Schultz 2004: 134). Mill urged Sidgwick to turn his “thoughts to this more comprehensive subject,” and apparently when the latter did, he concluded that it would not be conducive to the general happiness to continue his open attacks on organized religion. The reasons for this larger conclusion are only partly evident from the Methods itself.

Sidgwick did always explicitly claim, however, that his struggles with the ethics of subscription shaped the views set forth in the Methods. These struggles had led him “back to philosophy” from his more theological and philological investigations—for which he had learned German and Hebrew and struggled with biblical hermeneutics. He found the problem of whether he ought to resign his Fellowship very “difficult, and I may say that it was while struggling with the difficulty thence arising that I went through a good deal of the thought that was ultimately systematised in the The Methods of Ethics” (Sidgwick and Sidgwick, 1906: 38). One of the ways in which this is evident has been highlighted in the work of J. B. Schneewind, whose Sidgwick’s Ethics and Victorian Moral Philosophy (1977) was the most comprehensive and sophisticated commentary on Sidgwick’s ethics produced in the twentieth century. As part of an extensive account of the historical context of the Methods, underscoring how Sidgwick’s work was shaped by both the utilitarian tradition and its intuitionist and religious opposition (represented in part by the “Cambridge Moralists” William Whewell, Julius Hare, F. D. Maurice, and John Grote), Schneewind argued that

it is a mistake to view the book as primarily a defence of utilitarianism. It is true, of course, that a way of supporting utilitarianism is worked out in detail in the Methods, and that there are places in it where Sidgwick seems to be saying quite plainly that utilitarianism is the best available ethical theory. From his other writings we know also that he thinks of himself as committed to utilitarianism, and that he assumes it in analysing specific moral and political issues. Yet it does not follow that the Methods itself should be taken simply as an argument for that position. We must try to understand it in a way that makes sense of its author’s own explicit account of it. (Schneewind 1977: 192).

That account, as both Schneewind and Rawls have stressed, repeatedly affirms that the aim of the book is less practice than knowledge, “to expound as clearly and as fully as my limits will allow the different methods of Ethics that I find implicit in our common moral reasoning; to point out their mutual relations; and where they seem to conflict, to define the issue as much as possible.” That is, echoing his views on theological inquiry, he confesses that:

I have thought that the predominance in the minds of moralists of a desire to edify has impeded the real progress of ethical science: and that this would be benefited by an application to it of the same disinterested curiosity to which we chiefly owe the great discoveries of physics. It is in this spirit that I have endeavoured to compose the present work: and with this view I have desired to concentrate the reader’s attention, from first to last, not on the practical results to which our methods lead, but on the methods themselves. I have wished to put aside temporarily the urgent need which we all feel of finding and adopting the true method of determining what we ought to do; and to consider simply what conclusions will be rationally reached if we start with certain ethical premises, and with what degree of certainty and precision (Sidgwick 1874 [1907: vi]),

The model for such an approach is not Bentham or even J. S. Mill, but Aristotle, whose Ethics gave us “the Common Sense Morality of Greece, reduced to consistency by careful comparison: given not as something external to him but as what ‘we’—he and others—think, ascertained by reflection.” This was really, in effect, “the Socratic induction, elicited by interrogation” (Sidgwick 1874 [1907: xix]).

As Marcus Singer and others have observed (Singer 1974), Sidgwick’s notion of a “method” of ethics is not the same as that of an ethical principle, ethical theory, or ethical decision-procedure. A “method” is a way of “obtaining reasoned convictions as to what ought to be done” and thus it might reflect a commitment to one or more ethical principles as the ultimate ground of one’s determination of what one has most reason to do, here and now, while allowing that one might ordinarily be reasoning from such principles either directly or indirectly. Thus, one might, on theological grounds, hold that the moral order of the universe is utilitarian, with God willing the greatest happiness of the greatest number, while also holding that the appropriate guide for practical reason is enlightened self-interest, since utilitarian calculations are God’s business and God has ordered the cosmos to insure that enlightened self-interest conduces to the greatest happiness. In this case, one’s “method of ethics” would be rational egoism, but the ultimate philosophical justification for this method would appeal to utilitarian principles. Still, despite this emphasis on the reasoning process between principles and practical conclusions—another reflection of his struggles with subscription—Sidgwick obviously had quite a bit to say in the Methods about the defense of the ultimate principles of practical reason (Crisp 2014, 2015).

Many have felt that, in setting up the systematic comparison between the main methods of ethics, Sidgwick was not nearly as neutral and impartial as he thought, and in various ways slanted the discussion against a wide range of alternatives, including Aristotelian and other forms of perfectionism, Whewellian rationalism, Idealism, and more (Donagan 1977, 1992; Irwin 1992, 2007, and 2011; Hurka 2014a, 2014b). He simply dismisses the traditional philosophical concern with the “moral faculty,” explaining that he is going to leave that matter to psychologists. For Sidgwick, in any given situation, there is something that it is right or that one ought to do, and this is the proper sphere of ethics. The basic concept of morality is this unique, highly general notion of “ought” or “right” that is irreducible to naturalistic terms, sui generis, though moral approbation is “inseparably bound up with the conviction, implicit or explicit, that the conduct approved is ‘really’ right—that is, that it cannot without error, be disapproved by any other mind” (Sidgwick 1874 [1907: 27]). On this count, at least, his student G. E. Moore was willing to declare the Methods untainted by the “naturalistic fallacy”—that is, the confusion of the “is” of attribution and the “is” of identity that supposedly infected much previous ethical theory, including that of Bentham and the Mills. And indeed, it is plain that Sidgwick parted company from classical utilitarianism in many ways, rejecting the empiricism, psychological egoism, and associationism (supposedly) characteristic of the earlier tradition. F.H. Hayward, who wrote one of the first books on Sidgwick’s ethics, famously complained that E. E. Constance Jones had missed just how original Sidgwick was: “Sidgwick’s identification of ‘Right’ with ‘Reasonable’ and ‘Objective’; his view of Rightness as an ‘ultimate and unanalysable notion’ (however connected subsequently with Hedonism); and his admission that Reason is, in a sense, a motive to the will, are due to the more or less ‘unconscious’ influence of Kant. Miss Jones appears to think that these are the common-places of every ethical system, and that real divergences only arise when we make the next step in advance. I should rather regard this Rationalistic terminology as somewhat foreign to Hedonism. I do not think that Miss Jones will find, in Sidgwick’s Hedonistic predecessors, any such emphasis on Reason (however interpreted)” (Hayward 1900–1: 361). Sidgwick himself allowed that Kant was one of his “masters,” and he was also quite familiar with the works of Hegel. Schneewind’s reading (Schneewind 1977) has stressed this influence, along with the influence of Joseph Butler, whose works persuaded Sidgwick of the falsity of psychological egoism and of the reality of other than self-interested actions (Frankena 1992). Indeed, the comparison between Sidgwick and Kant has proved to be a fertile and ongoing source of academic work on Sidgwick, and one of increasing significance (Parfit 2011; Paytas 2018)

However, despite the considerable influence Kant and Kantianism—and the Cambridge Moralists—exercised on Sidgwick, the Methods also deviated from some stock features of such views, among other things rejecting the issue of free will as largely irrelevant to ethical theory and failing to appreciate the Kantian arguments about expressing one’s autonomy and the incompatibility of the categorical imperative and rational egoism. As Schneewind allows, Sidgwick’s

basic aim is similar to Kant’s, but, as his many points of disagreement with Kant suggest, the Kantian aspect of his thinking needs to be defined with some care. He detaches the issue of how reason can be practical from the most distinctive aspects of Kantianism. He rejects the methodological apparatus of the ‘critical philosophy’, the Kantian distinction of noumenal and phenomenal standpoints, and the association of the issue with the problem of free will. He treats the question of the possibility of rationally motivated action as answerable largely in terms of commonplace facts; he does not attribute any special synthesizing powers to reason beyond those assumed in ordinary logic; and he does not take morality to provide us with support for religious beliefs.. In refusing to base morality on pure reason alone, moreover, he moves decisively away from Kant, as is shown by his very un-Kantian hedonistic and teleological conclusions.. These points make it clear that the Kantian strain in Sidgwick’s thought is most marked in his central idea about the rationality of first principles (Schneewind 1977: 419–20).

Naturally, a Sidgwickian position on the venerable free will issue is bound to be controversial, and recent work on the Sidgwick/Kant comparison has brought out how divided commentators continue to be on this matter (Crisp 2015; Skelton 2016; Paytas 2018). Moreover, there has also been significant controversy over just how internalist Sidgwick’s account of moral motivation actually was. On balance, he held that the dictates or imperatives of reason were “accompanied by a certain impulse to do the acts recognized as right,” while admitting that other impulses may conflict (Sidgwick 1874 [1907: 34]). Brink (1988, 1992) has urged that some of Sidgwick’s chief arguments make better sense if he is construed, in externalist fashion, as allowing the possibility that one may have good reasons not to be moral. But Sidgwick’s moderate, qualified internalism seems plain and plausible enough to most commentators (Schultz 2004; de Lazari-Radek & Singer 2014; and Crisp 2015).

There has been perhaps even more controversy surrounding Sidgwick’s account of the “good.” The Methods is at least fairly clear in arguing that the difference between “right” and “good” in part concerns the way in which judgments of ultimate good do not necessarily involve definite precepts to act or even the assumption that the good in question is attainable or the best attainable good under the circumstances. Rightness and goodness thus “represent differentiations of the demands of our own rationality as it applies to our sentient and our active powers” (Schneewind 1977: 493). But Sidgwick offers an intricate account of ultimate good that has struck some as highly naturalistic. In A Theory of Justice, Rawls famously explained that Sidgwick “characterizes a person’s future good on the whole as what he would now desire and seek if the consequences of all the various courses of conduct open to him were, at the present point of time, accurately foreseen by him and adequately realized in imagination. An individual’s good is the hypothetical composition of impulsive forces that results from deliberative reflection meeting certain conditions” (Rawls, [1971], 1999: 366). Many have followed the Rawlsian line in casting Sidgwick as a defender of a naturalistic “full-information” account of the “good” (for example, Sobel 1994, and Rosati 1995), but the balance of scholarly opinion has it that Sidgwick’s account adumbrates an “objective list” view that allows that some desires, however informed, may be rejected as irrational or unreasonable (see especially Schneewind 1977; de Lazari-Radek & Singer 2014; and Parfit 1984, 2011). Crisp (1990, 2015) and Shaver (1997) provide helpful reviews of the debates; although the former offers perhaps the best possible defense of the interpretation of Sidgwick’s view as a naturalistic full-information account (with an experience requirement), it also admits that the objective list reading is a more charitable one.

Some commentators have made much of the difference between Sidgwick and Moore on the notion of ultimate good, urging that whereas Sidgwick prioritizes an unanalysable notion of “right,” Moore prioritizes an unanalysable notion of “good,” while adding a suspect ontological claim about “goodness” involving a non-natural property (Moore 1903; and Shaver 2000). However, Hurka (2003) has offered some forceful arguments against most such accounts:

After defining the good as what we ought to desire, he [Sidgwick] added that ‘since irrational desires cannot always be dismissed at once by voluntary effort,’ the definition cannot use ‘ought’ in ‘the strictly ethical sense,’ but only in ‘the wider sense in which it merely connotes an ideal or standard.’ But this raises the question of what this ‘wider sense’ is, and in particular whether it is at all distinct from Moore’s ‘good.’ If the claim that we ‘ought’ to have a desire is only the claim that the desire is ‘an ideal,’ how does it differ from the claim that the desire is good? When ‘ought’ is stripped of its connection with choice, its distinctive meaning seems to slip away (Hurka 2003: 603–4).

Moreover, as Hurka has developed the point, the “initial reviewers of Principia did not see it as altering Sidgwick’s ontology but emphasized its continuity with Sidgwick, while Moore himself said little about his non-natural property and even tried to limit his metaphysical claims, saying that though goodness is an object and therefore ‘is somehow’, it does not ‘exist’, and in particular does not exist in a ‘supersensible reality’ ” (Hurka 2014: 90). For his part, Sidgwick goes on to argue that the best going account of ultimate goodness is a hedonistic one, and that this is an informative, non-tautological claim, though also a more controversial one than many of the others that he defends. As Irwin and Richardson have insightfully argued, Sidgwick’s hedonistic commitments, and his criticisms of such views as T. H. Green’s, often reflected the (problematic) conviction that practical reason simply must be fully clear and determinate in its conclusions (Irwin 1992: 288–90; Richardson 1997). Without some such metric as the hedonistic one, Sidgwick argued, how can one virtue be compared to another? And can one really recommend making people more virtuous at the expense of their happiness? What if the virtuous life were conjoined to extreme pain, with no compensating good to anyone? But here again, Sidgwick’s arguments are not as perspicuous as they at first seem. Admittedly, as Shaver points out, “Sidgwick works out what it is reasonable to desire, and so attaches moral to natural properties, by the ordinary gamut of philosopher’s strategies—appeals to logical coherence, plausibility, and judgment after reflection.” (Shaver 1997: 270). Even so, as Rawls noted, “Sidgwick denies that pleasure is a measurable quality of feeling independent of its relation from volition. This is the view of some writers, he says, but one he cannot accept. He defines pleasure ‘as a feeling which, when experienced by intelligent beings, is at least apprehended as desirable or—in cases of comparison—preferable.’ It would seem that the view he here rejects is the one he relies upon later as the final criterion to introduce coherence among ends.” (Rawls [1971], 1999: 488). Sumner, in an important treatment, has also urged that Sidgwick and Mill, by contrast with Bentham,

seemed to recognize that the mental states we call pleasures are a mixed bag as far as their phenomenal properties are concerned. On their view what pleasures have in common is not something internal to them—their peculiar feeling tone, or whatever—but something about us—the fact that we like them, enjoy them, value them, find them satisfying, seek them, wish to prolong them, and so on (Sumner 1996: 86).

Although the last few years have seen a remarkable rehabilitation of ethical hedonism, particularly in the works of Crisp (2006, 2007, and 2015), Feldman (2004, 2010), and de Lazari-Radek and Singer (2017), the forms of hedonism being defended usually reconfigure or qualify the Sidgwickian approach in important ways. Crisp, who defends an internalist account of pleasure, even urges that Sidgwick’s writings did not express his better inclinations on the subject “Sidgwick is at heart an internalist about pleasure who was mislead by the heterogeneity argument into offering an externalist view which is open to serious objections” (Crisp 2007: 134). Indeed, on this count, Sidgwick might appear to be defending a position that is “intermediate between internalism and externalism,” as de Lazari-Radek and Singer note in their recent and very informed defenses of Sidgwickian hedonism against all the other alternatives, including the desire satisfaction view that Singer had previously adopted (de Lazari-Radek & Singer 2014: 254, 2016). However, Shaver (2016) has offered a subtle account and defense of Sidgwick’s notion of pleasure as feeling apprehended, perhaps wrongly, as desirable qua feeling, rather than as feeling manifesting a special tone of pleasantness.

This rehabilitation of Sidgwickian hedonism has also involved a recognition of the importance of the hedonimetrics of F. Y. Edgeworth, the brilliant economist who was a slightly junior contemporary of Sidgwick’s and one of his most enthusiastic philosophical disciples, though one whose work has until recently been largely ignored in philosophical commentary on Sidgwick (Edgeworth 1877 and 1881 [2003]). Edgeworth’s approach has been revived in economics by such figures as Kahneman (2011), and the convergence of economic and philosophical (and neurobiological) interests on this point suggests that Sidgwickian hedonism represents a new growth area in ethics. But it does seem that in key respects Sidgwick’s account remains superior to these more recent developments, which rely on a rather crude claim about pleasurable consciousness as a state that a subject wishes to prolong.