by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/25/20

-- The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett, 1851-1904

-- London Missionary Society, by Wikipedia

-- Chapter I: India in 1795, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter II:Nathaniel Forsyth and Robert May, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter III: Pioneer Work in South India: 1804-1820, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter IV: Pioneer Work in North India, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

-- Chapter V: South Indian Missions: 1820-1895, Excerpt from The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895, by Richard Lovett [1851-1904]

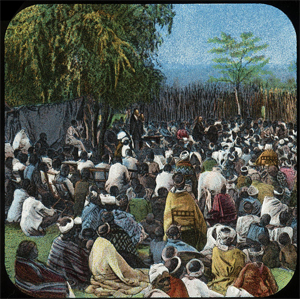

Around 1900, the London Missionary Society produced a series of glass magic lantern slides depicting the missionary efforts of David Livingstone such as this one.

The London Missionary Society was a predominantly Congregationalist missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Dr Edward Williams working with evangelical Anglicans and various nonconformists. It was largely Reformed in outlook, with Congregational missions in Oceania, Africa, and the Americas, although there were also Presbyterians (notable for their work in China), Methodists, Baptists and various other Protestants involved. It now forms part of the Council for World Mission (CWM).

Origins

In 1793, Edward Williams, then minister at Carr's Lane, Birmingham, wrote a letter to the churches of the Midlands, expressing the need for world evangelization and foreign missions.[1] It was effective and Williams began to play an active part in the plans for a missionary society. He left Birmingham in 1795, becoming pastor at Masbrough, Rotherham, and tutor of the newly formed Masbrough academy.[2] Also in 1793, the Anglican cleric John Eyre of Hackney founded the Evangelical Magazine. He had the support of the presbyterian John Love, and congregationalists Edward Parsons and John Townshend (1757–1826).[3]

Proposals for the Missionary Society began in 1794 after a Baptist minister, John Ryland, received word from William Carey, the pioneer British Baptist missionary who had recently moved to Calcutta, about the need to spread Christianity. Carey suggested that Ryland join forces with others along the non-denominational lines of the Anti-Slavery Society to design a society that could prevail against the difficulties that evangelicals often faced when spreading the Word. This aimed to overcome the difficulties that establishment of overseas missions had faced. It had frequently proved hard to raise the finance because evangelicals belonged to many denominations and churches; all too often their missions would only reach a small group of people and be hard to sustain. Edward Williams continued his involvement and, in July 1796, gave the charge to the first missionaries sent out by the Society.[1][4]

The society aimed to create a forum where evangelicals could work together, give overseas missions financial support and co-ordination. It also advocated against opponents who wanted unrestricted commercial and military relations with native peoples throughout the world.

After Ryland showed Carey's letter to Henry Overton Wills, an anti-slavery campaigner in Bristol, he quickly gained support. Scottish ministers in the London area, David Bogue and James Steven, as well as other evangelicals such as John Hey, joined forces to organize a new society. Bogue wrote an influential appeal in the Evangelical Magazine for September 1794:[5][6]

Ye were once Pagans, living in cruel and abominable idolatry. The servants of Jesus came from other lands, and preached His Gospel among you. Hence your knowledge of salvation. And ought ye not, as an equitable compensation for their kindness, to send messengers to the nations which are in like condition with yourselves of old, to entreat them that they turn from their dumb idol to the living God, and to wait for His Son from heaven? Verily their debtors ye are.

John Eyre responded by inviting a leading and influential evangelical, Rev. Thomas Haweis, to write a response to Bogue's appeal. The Cornishman sided firmly with Bogue, and immediately identified two donors, one of £500, and one of £100. From this start, a campaign developed to raise money for the proposed society, and its first meeting was organised at Baker's Coffee House on Change Alley in the City of London. Eighteen supporters showed up and helped agree to the aims of the proposed missionary society -– to spread the knowledge of Christ among heathen and other unenlightened nations. By Christmas over thirty men were committed to forming the society.

In the following year, 1795, Spa Fields Chapel was approached for permission to preach a sermon to the various ministers and others by now keenly associated with the plan to send missionaries abroad. This was organised for Tuesday 22 September 1795, the host chapel insisting that no collection for the proposed society must be made during the founding event which would be more solemn, and formally mark the origin of the Missionary Society. Hundreds of evangelicals attended, and the newly launched society quickly began receiving letters of financial support, and interest from prospective missionaries.

Early days

Joseph Hardcastle of Hatcham House, Deptford became the first Treasurer, and the Rev. John Eyre of Hackney (editor of the Evangelical Magazine ) became the first Secretary to the Missionary Society—the latter appointment providing it with an effective 'newspaper' to promote its cause. The Missionary Society's board quickly began interviewing prospective candidates. In 1800 the society placed missionaries with the Rev. David Bogue of Gosport for preparation for their ministries.[7]

The cession of the district of Matavai in the island of Tahiti to Captain James Wilson for the use of the missionaries.

A Captain James Wilson offered to sail the missionaries to their destination unpaid. The society was able to afford the small ship Duff, of 267 tons (bm). It could carry 18 crew members and 30 missionaries. Seven months after the crew left port from the Woolwich docks in late 1796 they arrived in Tahiti, where seventeen missionaries departed. The missionaries were then instructed to become friendly with the natives, build a mission house for sleeping and worship, and learn the native language. The missionaries faced unforeseen problems. The natives had firearms and were anxious to gain possessions from the crew. The Tahitians also had faced difficulties with diseases spread from the crews of ships that had previously docked there. The natives saw this as retribution from the gods, and they were very suspicious of the crew. Of the seventeen missionaries that arrived in Tahiti, eight soon left on the first British ship to arrive in Tahiti.

When Duff returned to Britain it was immediately sent back to Tahiti with thirty more missionaries. Unfortunately this journey was disastrous. A French privateer captured Duff, landed its prisoners in Montevideo, and sold her. The expense of the journey cost 'The Missionary Society' ten thousand pounds, which was initially devastating to the society. Gradually it recovered, however, and in 1807 was able to establish a mission in Guangzhou (Canton), China under Robert Morrison.

Another missionary who served in China was John Kenneth Mackenzie. A native of Yarmouth in England, he served in Hankow and Tientsin.

Starting in 1815, they hired Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir as a translator, to work on many texts including the gospels.[8]

After attending Homerton College, then in Hampstead, William Ellis (missionary) was ordained in 1815. Soon after his marriage to Mary Mercy Moor on 9 November 1815 they were posted to the South Sea Islands returning in 1824. He later become Chief Foreign Secretary.[9]

In September 1816 Robert Moffat (1795–1883) was commissioned in the Surrey Chapel, on the same day as John Williams. Moffat served in South Africa until 1870. Mary Moffat joined him and they married in 1819. The LMS only employed male missionaries and it preferred them to be married. The Moffats were to have several children who also became and/or married missionaries.[10]

In 1817 Edward Stallybrass was sent out to Russia to start a mission among the Buryat people of Siberia. The mission received the blessing of Alexander I of Russia, but was suppressed in 1840 under his successor Nicholas I. Alongside Stallybrass worked Cornelius Rahmn [Wikidata] of Sweden, William Swan and Robert Yuille of Scotland.

Later work and notable missionaries

London Missionary Society, Sāmoa (1949)

In 1818, the society was renamed The London Missionary Society.

In 1822, John Philip was appointed superintendent of the London Missionary Society stations in South Africa where he fought for the rights of the indigenous people.

1823 - John Williams discovered the island of Aitutaki, in Rarotonga. It is here that the missionary work was first established. In later years John Williams visited Rarotonga, taking with him two Tahitians he picked up from Tahiti. One of the Tahitians, named Papehia, was used as intermediaries to convince local chiefs to join the new gospel.

1830 – John Williams sighted the coast of Savai'i in Samoa and landed on August 24, 1830 at Sapapali'i village in search of Malietoa Vai‘inupo, a paramount chief of Samoa. John Williams was greeted by his brother Taimalelagi. Upon meeting Malietoa at a large gathering in Sapapali'i, the LMS mission was accepted and grew rapidly throughout the Samoan Islands. The eastern end of the Samoan archipelago, was the kingdom of Manu'a. The paramount chief, Tui-Manu'a embraced Christianity and Manu'a also became a LMS island kingdom.

1832 – John Williams landed at Leone Bay in what was later to become American Samoa. (Tala faasolopito o le Ekalesia Samoa) He was informed that men of their village have accepted the 'lotu' brought by an Ioane Viliamu in Savai'i; not knowing John Williams now stood before them. A monument stands before the large Siona Chapel – now CCCAS in Leone, American Samoa – in honor of John Williams.

In 1839 John Williams's missionary work whilst visiting the New Hebrides came to an abrupt end, when he was killed and eaten by cannibals on the island of Erromango whilst he was preaching to them. He was traveling at the time in the Missionary ship Camden commanded by Captain Robert Clark Morgan (1798-1864). A memorial stone was erected on the island of Rarotonga in 1839 and is still there today. His widow is buried with their son, Samuel Tamatoa Williams, at the old Cedar Circle in London's Abney Park Cemetery, the name of her husband and the record of his death described first on the stone. John Williams' remains were sought by a group from Samoa and his bones were brought back to Samoa, where throngs of the LMS mission attended a funeral service attended by Samoan royalty, high-ranking chiefs and the LMS missionaries. His remains were interred at the native LMS church in Apia. A monument stands in his memory across from the Congregational Christian Church of Apia chapel.

Rev. Alexander MacDonald and his wife Selina Dorcas (née Blomfield) arrived in Rarotonga in May 1836, then Samoa in April 1837 and settled at Safune on the central north coast of Savai'i island in [Samoa in August 1837. He left the LMS in 1850 when he accepted a position with the Congregational church in Auckland, New Zealand.[11]

1839–1879 – Reverend George Pratt served as a missionary in Samoa for many years, at the station at Matautu on Savai'i island.[12] Pratt was a linguist and authored the first grammar and dictionary on the Samoan language, first published in 1862 at the Samoa Mission Press.

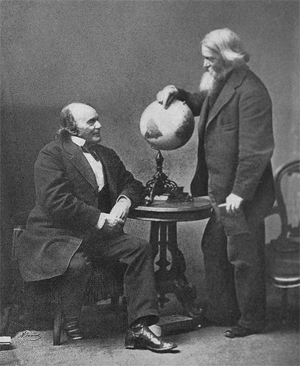

In 1840 the medical missionary and explorer David Livingstone (1813-1873) departed for South Africa, arriving in 1841, and serving with the LMS until 1857. Moffat and Livingstone met circa 1841. In 1845 Livingstone married Robert and Mary Moffat's daughter Mary (1821-1862).

1844 – London Missionary Society established Malua Theological College at the village of Malua on Upolu to educate local men to become village clergy for the rapidly growing mission with over 250 villages and 25,000 membership.

1844 – London Missionary Society sent Samoan missionaries to surrounding islands; Rotuma, Niue, Tokelau, Ellice Islands, Papua, Vanuatu. Over 300 served in Papua alone.

The society soon sent missionaries all over the world, notably to India, China, Australia, Madagascar and Africa. Famous LMS missionaries included

• Robert Morrison (1782–1834) who went to China in 1807;

• John Smith (1790–1824) was a LMS missionary whose experiences in the West Indies, beginning in 1817, attracted the attention of the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce. As a result of his actions in the Demerara rebellion of 1823, trial by court martial and subsequent death in 1824, whilst under imprisonment, Smith became known as the "Demerara Martyr";[13]

• John Abbs (1810–1888) who went to India in 1837. he spent twenty-two years in Travancore, Southern India.[14]

• James Legge (1815–1897), Sinologist;

• David Livingstone (1813–1873) who went to South Africa in 1840;

• Griffith John 楊格非 (1831-1912) from 1855 in Hubei [Hupeh], Hunan, [Szechwan], China;

• John Mackenzie (1835–99) who went to South Africa in 1858, argued for the rights of the Africans and against the racism of the Boers, and was instrumental in the creation of the Bechuanaland Protectorate (modern Botswana);

• Fred C. Roberts (1862-1894) went to Tientsin, China in 1887, taught at the first Western medical school in China and brought famine relief to rural villagers [15]

• Ernest Cromwell Peake (1899-1922) who brought 'western medicine' to Hengchow, China;

• Ernest Black Struthers (1886-1977) who travelled to Hong Kong in 1913;

• Eric Liddell, 1924 Olympic gold medalist in the 400 metres race, served as an LMS missionary to China.

Merger

The London Missionary Society merged with the Commonwealth Missionary Society (formerly the Colonial Missionary Society) in 1966 to form the Congregational Council for World Mission (CCWM). At the formation of the United Reformed Church in 1972 it underwent another name change, becoming the Council for World Mission (Congregational and Reformed). The CWM (Congregational and Reformed) was again restructured in 1977 to create a more internationalist and global body, the Council for World Mission.

The records of the London Missionary Society are held at the library of the School of Oriental and African Studies in London.

See also

• List of London Missionary Society missionaries in China

• Protestant missionary societies in China during the 19th Century

• School of Oriental and African Studies in London

• The Historical Background to Church Activities in Zambia

• List of ships named John Williams, seven LMS missionary ships

• SS Ellengowan, a missionary ship

• Missionary Day, French Polynesian holiday celebrating the arrival of the Duff in 1797

Publications

• Rev. C.W Abel, 'Savage Life in New Guine'

• Rev. George Pratt, 'A Grammar and Dictionary of the Samoan Language'

• Dr. M. Christhudhas, 'Christianity and Health & Educational Development in South Travancore : The Work of the London Missionary Society from 1890-1947'

References

1. Wadsworth KW, Yorkshire United Independent College -Two Hundred Years of Training for Christian Ministry by the Congregational Churches of Yorkshire Independent Press, London, 1954

2. The LMS and the academy at Masbrough both date from the year 1795.

3. Porter, Andrew (2004). "Founders of the London Missionary Society (act. 1795), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/42118. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

4. Morison, John Fathers and Founders of the London Missionary Society - a Jubilee Memorial pages 427-443 chapter titled Memoir of the Late Edward Williams London: Fisher 1844. This publication may be viewed online at https://archive.org/stream/fathersfound ... 6/mode/2up

5. Laird, Michael. "Bogue, David". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2766. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

6. James Hay; Henry Belfrage (1831). A memoir of the Reverend Alexander Waugh: with selections from his ... correspondence, pulpit recollections, &c. ... Hamilton, Adams, & Co. p. 203.

7. Parker, Irene (1914). Dissenting academies in England: their rise and progress, and their place among the educational systems of the country. Cambridge University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-521-74864-3.

8. Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 23. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

9. Jane Holloway (2019). Wisbech's Forgotten Hero. AuthorHouse.

10. "Moffat, Robert (1795–1883), missionary in Africa and linguist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18874. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

11. Lovett, Richard (1899). The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895. London : Henry Frowde.

12. Marjorie Crocombe & Ron Crocombe (1968). Works of ta'unga: records of a Polynesian traveller in the south seas, 1833-1896. University of the South Pacific. p. 19. ISBN 982-02-0232-9.

13. "Wallbridge's 'The Demerara Martyr'"

14. Charles Sylvester: The Story of the L. M. S., 1795-1895, 1895, p. 298. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

15. Bryson, Mary (1895). Fred C. Roberts of Tientsin. London: H.R. Allenson.

Bibliography

• Ellis, William (1844), 'History of the London Missionary Society', London: John Snow Volume One

• Lovett, Richard (1899), 'History of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895', London: Henry Frowde Volume One, Volume Two

• Goodall, Norman (1954), 'History of the London Missionary Society 1895-1945', London: O.U.P.

• Hiney, Thomas (2000), 'On the Missionary Trail', New York: Atlantic Monthly Press

• Chamberlain, David (1924), 'Smith of Demerara', London: Simpkin, Marshall &co

• Northcott, Cecil (1945), 'Glorious Company; 150 Years Life and Work of the London Missionary Society 1795–1945', London:Livingstone Press

• The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle

• Spa Fields Chapel Minutes, British History Online: Spa Fields Chapel Minutes: 1784-1811 | British History Online

External links

• The Council for World Mission (which incorporated the former LMS)

• Pilots website Youth organisation originally established to support the LMS

• Works by London Missionary Society at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about London Missionary Society at Internet Archive

• Griqua Coinage

• The papers of the London Missionary Society, and the Council for World Mission are held at SOAS Archives

************************************

The history of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895 [Excerpt]

by Richard Lovett, 1851-1904

'This is the word of the Lord unto Zerubbabel, saying, Not by might nor by power, but by my Spirit, saith the Lord of Hosts.

'Who art thou, O great mountain? before Zerubbabel thou shalt become a plain.' — Zech. iv. 6, 7.

'When in London Carey had asked John Newton, "What if the Company should send us home on our arrival in Bengal?" "Then conclude," was the reply, "that your Lord has nothing there for you to accomplish. But if He have, no power on earth can hinder you."' — Smith's Life of William Carey (1887), p. 55.

.'A Hindu may choose to have a faith and a creed, if he wants a creed, or to do without one. He may be an atheist, a deist, a monotheist, or a polytheist, a believer in the Vedas or Shastras, or a sceptic as regards their authority, and his position as a Hindu cannot be questioned by anybody because of his belief or unbelief, so long as he conforms to social rules.' — Guru Prosad Sen

'It is not unreasonable to suppose that the last conquests of Christianity may be achieved with incomparably greater rapidity than has marked its earlier progress and signalized its first success; and that in the instance of India the ploughman may overtake the reaper, the treader of grapes him that soweth the seed," and the type of the prophet realized, that "a nation shall be born in a day."' — SIR J. E. Tennant's Christianity in Ceylon, p. 327

CHAPTER I: INDIA IN 1795

In the last decade of the eighteenth century the vast majority of the inhabitants of Great Britain knew less about India than those of to-day know about Patagonia, and their interest in the welfare of its myriad peoples was slighter far than their knowledge of the country. The shareholders in the East India Company, and that limited section of the mercantile community which was awakening to the importance of India as a field for commercial and military enterprise, valued it as a means of rapid fortune-making. The only people who were beginning to devote serious and earnest attention to the nation's responsibilities in India were the despised evangelical section — voices crying in the wilderness — represented by such men as Carey and Bogue among the Nonconformists of England, and by men like Charles Grant of the East India Company. India then was more remote from the currents of common life and thought than Thibet is to-day. The fire of love to Christ, of faith in God, of quenchless desire to heal the sorrows of men, burning in humble yet consecrated hearts, supplied the motive power which has brought about the wonderful progress in India during the last century.

To reach India in 1795 was a serious undertaking, involving a voyage of long and uncertain duration. So little was known of the country that when, in 1804, Cran and Des Granges were sent to South India, their instructions indicated that they were expected to superintend churches in Tinnevelly, and also initiate a mission among the Northern Circars; that is, they were to carry on mission work in two centres, differing in every possible respect, and separated by at least 500 miles! And this ignorance is not marvellous when it is borne in mind that with all the information which has been circulated among missionary circles during the century, not one in ten of even the intelligent supporters of missionary enterprise can name the chief languages spoken in India, or indicate with any completeness the most powerful hindrances, due to native custom and thought, to the spread of the Gospel in the different parts of that vast land.

India is really a continent; as large as Europe less half of European Russia, and more varied in its different portions than Europe itself. In 1795 the population was about 150,000,000, one-fifth of the whole human race. By these myriads at least thirteen distinct, historic, literary languages were spoken, and no less than 100 minor languages and dialects are found in different parts. India, moreover, was the home of an ancient if simple civilization, the people were dominated by hoary and powerful religions, they were self-contained, self-satisfied, and conscious of no need of enlightenment such as Christianity brings, and in the world's history no enterprise has seemed so forlorn as Carey's when he sailed up the Hugli to 'attempt great things for God' among the teeming millions of Bengal.

Long years passed before the Church at home began to comprehend the mighty forces arrayed against the Gospel in India. Some of these sprung from the Hindus themselves, their manners, customs, laws, and beliefs; while others were due also in no small degree to the East India Company. To realize what the task attempted by the Christian Church in India from 1792 to 1825 really was, it is needful to glance at these in turn. The Rev. E. P. Rice, B.A., of the London Mission, Bangalore, has very ably set forth the chief of these:1 —

'1. First, there is the institution of caste, by which Hindu society is divided up into several thousands of sections, between which all intermarriage and exchange of hospitality is forbidden by the heaviest penalties. It has really no parallel in any other nation, and is generally recognized to be a more formidable barrier than any usage Christianity in the whole course of its history has had to contend against.

'2. Connected with this is the absence of all religious and social liberty, which makes the adoption of any other than the traditional customs the reason for relentless persecution by the whole community, and (until recently) for the forfeiture, not only of property, but of all civil and social and family privileges.

'3. The utterly perverted standard of conduct, which places Custom in the room of Conscience, and above all the laws of the Decalogue, demanding external conformity, and caring little for motive or character. There is no punishment in Hindu society for real wickedness, nor any encouragement for pure virtue. It lays supreme stress only upon such things as meats, and drinks, and sect-marks.

'4. The overweening arrogance and oppressive supremacy of the Brahman class, who by the gross abuse of their high intellectual gifts have made themselves to be regarded as "gods upon earth," moulded of superior clay to the rest of mankind, to whom all gifts are due by virtue of their mere birth, in whose interests all Hindu legislation has been made, and who have got into their hands all the positions of influence, and the control of all the wealth in the land, and who treat the remaining 95 per cent of the population as if called into being solely for their benefit.

'5. The gigantic system of Polytheistic idolatry — strong chiefly on account of its enormous endowments, the number of persons who make their living by it, and its power of deadening the conscience; a system which is served by a dissolute priesthood, popularized by festivals, processions, ritual, and legends; and stained by licensed prostitution and other forms of immorality.

'6. The fear of malignant demons (called euphemistically in Government returns "Animism"), which forms the worship of well-nigh half the population, who present their bloody offerings to the spirits whom they suppose to be the authors of cholera, small-pox, and cattle disease.

'7. The belief in religions merit to be obtained by acts of idol-ritual, pilgrimages to supposed sacred spots, and bathing in supposed sacred waters, by self-mortification, by almsgiving, and by the service of the Brahmans.

'8. The seductive Pantheistic teaching, which wipes out the distinction between right and wrong, denies the authority of conscience, the personality of God and the responsibility of man, and makes universal apathy the highest ideal of life, utterly paralyzing the will for any good, divorcing morality from religion and conduct from conviction.

'9. The degradation of woman, who is decreed to be mistress of herself at no period from birth to death, and showing itself in infant marriages, the immolation or cruel treatment of widows, the seclusion of vast multitudes in the zenana, and the withholding from her of education.

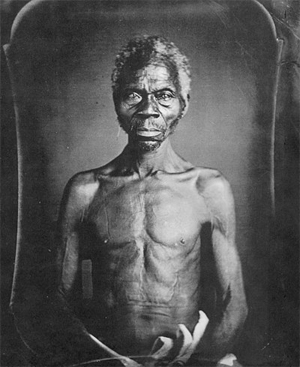

'10. The sad and immemorial degradation of the low castes (Panchamas), numbering some 50,000,000, who are treated as the lepers and offscouring of the earth, whose touch is pollution, denied the right to live in the villages, to draw water from the wells, to attend the schools, and sometimes even the use of the public roads.

'11. Add to these a whole jungle of superstitions beliefs and corrupt practices, which have been allowed to grow and multiply, rank and unchecked, for ages: astrology, belief in omens, obscene tantric rites, human sacrifices, Thuggism, infanticide, false-swearing, forgery, cunning exalted to the place of a virtue, policy to that of righteousness, unscrupulous usury, the prohibition of foreign travel, and the spirit of compromise, which takes under its sanction every form of superstition, as well as of vice and lust and cruelty. All these have to be replaced by the light of knowledge, and by the sweet atmosphere of Christian love, purity, justice, trust, and godliness.

'By these great evils had the natural charm and graces of the Indian character been overborne. A frugal, home-loving, docile, courteous, and religious people, with a simple civilization, with many gracious traits and beautiful customs, and with much power of subtle thought, had been misled by the ignorance or unscrupulousness of their leaders. No kinder act could be done for them than to deliver the Hindus from Hinduism, and the Brahmans from Brahmanism, and to bring them into the glorious liberty and joy of the sons of God, and into the high privilege of discipleship to Him who has shown Himself the world's great Redeemer, the sinless Friend of sinners. Such was the task which the Church set before itself in the missionary enterprise.

'To all this must be added the conversion to Christ of the great Muhammadan population, numbering 58,000,000, more numerous in India than in any other country, inheriting many true conceptions respecting God and man, together with a chastely simple form of worship, and yet unable to reap the advantages of this inheritance, because of the pure externality in which they have made the essentials of religion to consist, their bigoted resistance to all new truth, and the finality they attribute to the traditional teaching and practices of Muhammad.'

To those who ponder this colossal system of religious beliefs and practices, and who remember the vast populations concerned, it will be obvious that victory over it can be won by no brief, spasmodic attacks, but only by a careful, many-sided propaganda, patiently and steadily maintained for a prolonged period. In previous centuries the Christian Church has never realized these facts, and has attempted the conversion of India by puny and inadequate efforts foredoomed to failure. During the nineteenth century it selected the most appropriate methods, and on a larger scale, which in due time will accomplish its purpose, and replace Hinduism by a fairer Christianity.

In addition to these tremendous obstacles, the early missionaries had to face bitter opposition where they might have reasonably expected, if not active co-operation, at least sympathy and toleration — at the hands of the East India Company. By the close of the eighteenth century the Company had become practically, though not yet absolutely, masters of India. Actually the Company held sway over only the Bengal, Behar, and Benares districts of the Ganges Valley, together with some stations on the Madras and Malabar coasts and Seringapatam. But the condition of the rest of India was such as to render the subsequent progress of conquest inevitable. In the earlier stages of its history the Company was not unmindful of its duties towards its employes, and endeavoured to secure for the main stations suitable chaplains. But at no period of its history does it ever seem to have considered the instruction of the natives in Christianity to be any part of its duty. From time to time among the officials and chaplains there were individuals who felt and who tried to discharge this responsibility; but it was done always in spite of, not with, official sanction. The ablest man of this class, and one to whom India owes an incalculable and yet largely unacknowledged debt, was Charles Grant. After thirty years' service he went home, became Chairman of the Directors, and in 1797 presented to the Board his Observations on the State of Society among the Asiatic Subjects of Great Britain. This treatise, so full of information and suggestions of the highest value, was kept back by his colleagues, and was not generally circulated until the year1813.

Public opinion at home, especially in those circles influenced by the 'Clapham Sect,' was becoming strongly aroused to the necessity of ending the complacent paganism of the East India Company's policy. In 1793, when the renewal of the charter came before Parliament, Wilberforce succeeded in passing a resolution 'that it is the peculiar and bounden duty of the British Legislature to promote, by all just and prudent means, the interest and happiness of the inhabitants of the British dominions in India; and that for these ends such measures ought to be adopted as may gradually tend to their advancement in useful knowledge, and to their religious and moral improvement.' But this resolution, tame and commonplace as it reads to-day, aroused such an angry storm that the Government threw over both it and its author, and for another twenty years the misdirected bigotry and short-sightedness of the East India House had their way. Not until 1813 was the victory won for religious freedom. 'The charter of 1813 was the foundation not only of the ecclesiastical establishment, but, what is of far more importance for the civilization and the Christianization of its people, of the educational system of India.'2

The result was immediate, and was also progressively satisfactory. Prior to 1813 missionaries had to be smuggled into the country, and could be expelled by the arbitrary dictum of the local governor. Not only was nothing done to teach the Hindus the folly and error of their religious systems, but in many ways British influence was used to protect and maintain them. As late as 1819 a Sepoy was expelled from the army for the crime of becoming a Christian, and Sir Peregrine Maitland, Commander-in-Chief of the Madras army, resigned rather than submit to the degradation of saluting idols. Even after 1813, Christian officials were not allowed in their private capacity the privilege of attempting to show Hindus 'the more excellent way' they followed themselves. But from the moment the charter passed, India entered upon a new path of political, social, and religious progress.

'At no period in the history of the Christian Church, not even in the brilliant century of legislation from Constantine's edict of toleration to the Theodosian code, has Christianity been the means of abolishing so many inhuman customs and crimes as were suppressed in India by the Company's Regulations and Acts in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Christ-like work kept rapid step with the progress of Christian opinion and beneficent reforms in Great Britain, but it was due in the first instance to the missionaries in India. In the teeth of the supporters of Hinduism, European as well as Brahmanical, and contrary to the custom of centuries, it ceased to be lawful, it became penal, even in the name of religion: (1) to murder parents by suttee, by exposure on the banks of rivers, or by burial alive; (2) to murder children by dedication to the Ganges, to be devoured by crocodiles, or daughters by the Rajpoot modes of infanticide; (3) to offer up human sacrifices in a temple, or to propitiate the earth-goddess; (4) to encourage suicide under the wheels of idol-cars, or wells, or otherwise; (5) to promote voluntary torment by hook-swinging, thigh-piercing, tongue-extraction, &c.; or (6) involuntary torment by mutilation, trampling to death, ordeals, and barbarous executions. Slavery and the slave-trade were made illegal. Caste was no longer supported by law, nor recognized in appointments to office. The long compromise with idolatry during the previous two centuries ceased, so that the Government no more called its Christian soldiers to salute idols, or its civil officers to recognize gods in official documents, or manage the affairs of idol-temples, and extort a revenue from idol-pilgrimages. A long step was taken by legislative Acts to protect the civil rights of converts to Christianity as to any other religion, and to leave Hindu widows free to marry.' 3

As Dr. George Smith points out in his Short History of Missions,4 'the real missionary influence of the East India Company, exercised by Providence through it in spite of its frequent intolerance and continued professions of neutrality till it was swept away in the blood of the Mutiny, was like that of the Roman Empire: (1) the Company rescued all Southern Asia from anarchy and made possible the growth of law, order, property, and peace as a sort of moral police; (2) the Company introduced roads, commerce, wealth, and the physical preparation for the Gospel during a time of transition; (3) the Company quickened the conscience of Great Britain and its churches as they awoke to their duty after the close of the eighteenth century, partly by its extreme opposition to missions, partly by the earnest civilians and officers, and in a very few cases merchants and chaplains, whom it sent home with knowledge and experience. The East India Company has hardly any higher praise than that of the pagan Roman Empire, but it is entitled to that — it did for the southern nations of Asia what Rome had done for the northern nations of Europe.'

To the India thus prepared for the Gospel went the missionaries of the London Missionary Society, the first to follow where Carey, with quenchless faith, indomitable energy, and sound common sense, had so bravely led the way.

[Authorities. — Letters and Official Reports ; Dr. George Smith's Conversion of India, and Short History of Missions; A Primer of Modern Missions, edited by R. Lovett, M.A.; A History of Protestant Missions in India, 1706-1882, by M. A, Sherring, revised by E. Storrow, 1884]

_______________

Notes:

1 Primer of Modern Missions, p. 34.

2 The Conversion of India, by Dr. George Smith, p. 109.

3 The Conversion of India, p. 110

4 p. 145.

CHAPTER II: NATHANIEL FORSYTH AND ROBERT MAY

The Report for 1798 contains the earliest reference in the Society's annals to definite work in India. There we read: 'A pleasing expectation is entertained of the Rev. Nathaniel Forsyth, who is a well-informed man, and appears to be animated by a truly missionary spirit. He has been set apart for his work, and has lately embarked for the Cape of Good Hope.' To this man belongs the abiding honour of having been the first, and for some years the sole, missionary sent out by the Society to the vast field of India. The Reports for the years 1800 to 1803 continue his story: —

'Since the last General Meeting, the Directors have received several letters from Mr. Forsyth, the Society's missionary in the East Indies. It is expected that before this time he has fixed on a favourable spot (in the vicinity of Calcutta) for the commencement of his missionary labours, as it does not appear that he has met with any material impediment in his design of prosecuting this important service. He complains of, and feelingly laments, the extreme depravity and deeply rooted superstitions of the Hindoos, which render them very inimical to the simplicity and purity of the Gospel. He requests that additional missionaries may be sent to his assistance, and points out such means for their introduction and patronage as the Directors trust will prove a providential opening, for the increase of missionary labour and success in that populous but dreadfully depraved country. This mission must therefore be considered as in its infancy: very little as yet can have been done, but much useful information has been acquired, and the Directors will, no doubt, avail themselves of every assistance that has been, or may be, given to send out more labourers into this eastern part of our Lord's vineyard.'1

'A letter, dated August 5, 1800, has lately been received from Mr. Forsyth, the Society's missionary in India. At that time he was well in health, had made considerable proficiency in the language of the country, and was about to begin a school for the instruction of the children of the natives. Mr. Forsyth appears to possess a true missionary spirit, and he exhibits fidelity and disinterestedness of character and conduct. The Directors have long since been authorized to increase the mission to that part of the world, but circumstances have occurred to frustrate their desires and intentions.'2

'The Directors, on referring to the solitary labours of Mr. Forsyth in the East Indies, cannot help lamenting that a region so extensive, with a population proportionably great, and also deplorably superstitious and idolatrous, should not have shared more largely in the benevolent exertions of this Society. The resolutions of general meetings have so frequently authorized and recommended missions to several parts of the East Indies, that these objects could not possibly be forgotten, and they have not been, nor will they be neglected, whenever missionary zeal and ability shall combine and present means to accomplish them; but the Directors have not yet been favoured with offers from persons whose qualifications are suited, in their opinion, to strengthen, enlarge, and establish efficient missionary exertions in the East Indies. By letters which have been received from Mr. Forsyth, it appears that he continues to labour with diligence and zeal: and, it is hoped, not without attestation of divine approbation and influence. It is both right and necessary to add that Mr. Forsyth has acted in a very disinterested manner towards this Society, having subjected it to no expense on his account since his arrival in India.'3 'They trust that their solitary missionary in India (Forsyth), who has long expressed his ardent desire for assistance in that extensive field of action, will have this desire gratified; and that the many millions of heathens in those idolatrous regions will be continually receiving fresh accessions of Christian missionaries from this Society and others, who, like friendly allies, will afford their mutual aid in the cause of their common Lord.'4

Thus in the first eight years of its existence the Society was able to send and to maintain in India only one solitary missionary. But the reasons for this were many, and readily account for seeming slackness on the part of the Directors. The India of 1800 was further away from London than the heart of Darkest Africa is to-day. The East India Company was so bitterly hostile to all efforts for carrying to the Hindus a knowledge of the Gospel that missionaries were expressly forbidden to land, and even if they succeeded in landing were deported by force. Carey, who had preceded Forsyth by only five years, owed his gaining a foothold to the providential fact that Denmark held a small patch of Indian territory around Serampore, and threw over him and his colleagues the mantle of her protection. It is one of the ironies of history that while Great Britain, one of the most powerful of European nations, from whom Carey sprang, exerted her power to frustrate his benevolent aims, Denmark, one of the least influential of European peoples, was able to hold open the door of blessing through which Carey and his colleagues, and also Nathaniel Forsyth, entered to begin their beneficent labours for the millions of India.

All the original records of Forsyth's work in India seem unhappily to have disappeared, and he is a man of whom we would have gladly known more. In 1812 he was joined at Chinsurah by Mr. and Mrs. May. The former was an ardent and skilful educationalist, and carried on a most successful system of school-work. About the same time Forsyth ceased to be directly connected with the Society, and he died at Chandernagore on Feb. 14, 1816. G. Gogerly, one of his immediate successors in the Bengal Mission, gives the following sketch5 of him: —

'Mr. Forsyth is described as being a man of most singular self-denial and large-heartedness, and as generous to an extreme. His whole time, talents, and property he devoted most conscientiously to his missionary work, and to the relief of suffering humanity. From the funds of the London Missionary Society he never received anything, with the exception of a few dollars when he embarked for India. His private resources were exceedingly limited, and, in consequence, his mode of living was most simple and inexpensive. "For a time," said his friend Mr. Edmond, whom everybody in Calcutta knew and loved, "he had no stated dwelling-place, but lived in a small boat, in which he went up and down to preach at the different towns on the banks of the river."

'By the Dutch Local Government Mr. Forsyth was appointed minister of the Church at Chinsurah; and, after frequently refusing any remuneration for his services, consented at last to accept fifty rupees a month. The Hon. Mr. Harrington, a firm friend of missions, placed at his disposal a small bungalow at Bandel, about three miles above Chinsurah, from which spot he regularly walked every Sunday morning to discharge his duties; afterwards, not unfrequently, he would proceed to Calcutta to preach at the General Hospital, by permission of the Rev. David Brown, then senior presidency and garrison chaplain.

'This injudicious mode of living in a country like Bengal, denying himself almost the common necessaries of life, refusing to travel either by carriage or palankeen, but always walking where he could not be conveyed by boat, produced, as might be expected, the prostration of a naturally strong constitution; and after eighteen years of labour Mr. Forsyth died in 1816, aged forty-seven years. Thus fell the first pioneer connected with the London Missionary Society in Bengal; not, however, until he had given an impetus to that glorious work which will go on until the whole of India is brought into subjection to the Lord Jesus Christ.'

Robert May was an educationalist of no mean power. He was spared to labour for only five years, but during that time he accomplished some remarkable results.

'How eminently successful he was in this branch of labour may be gathered from the fact, that at the end of 1815 he had twenty schools under his charge, in which instruction was imparted to 1651 children, of whom as many as 258 were the sons of Brahmans, a remarkable circumstance in those times. The scheme of education was highly approved by Mr. Gordon Forbes, the Commissioner of Chinsurah, and was by him recommended to the Supreme Government. The Marquis of Hastings readily complied with the request of Mr. Forbes, that the scheme should be aided from the imperial funds, and with great liberality appropriated a monthly grant of 600 rupees (about £60) for the purpose. By the aid of the grant, in the course of the next year, the schools and scholars were still further multiplied, so that at its close Mr. May had under his superintendence as many as thirty schools, in which 2,600 children received instruction. The Government, on hearing these rapid results, forthwith increased its grant to 800 rupees monthly. Mr. May found himself unable to attend to this great work alone, and was soon joined by the Rev. J. D. Pearson, sent out from England, and by Mr. Hasle, a European who had resided for several years in India.' 6

The mission continued in the hands of the London Society for a long period. It was prosecuted with much zeal, and conveyed much useful knowledge to tens of thousands of the people. One of the most diligent missionaries of the Society was the Rev. G. Mundy, who took up the work in Chinsurah in 1820. He suffered much in his family and in himself from ill health, and ceased to have any direct connection with Chinsurah in 1844. He was succeeded by James Bradbury, who had joined the mission in 1842, and who laboured there until the station was, in 1849, transferred to the Free Church of Scotland. The last reference to Chinsurah in the Reports occurs in 1849. 'The Directors are gratified to state that, having been led to relinquish this station in consequence of the inadequate resources of the Society, arrangements have been made for its transfer to the Free Church of Scotland.' Mr. Bradbury in 1849 removed to Berhampur, and the Society's direct association with the scene of the labours of Nathaniel Forsyth thus came to a close.

[Authorities. — Official Reports; Transactions of the Society, vols i-iv; History of Protestant Missions in India, Sherring; The Pioneers: A Narrative of Facts connected with Early Christian Missions in Bengal, chiefly relating to the operations of the London Missionary Society, George Gogerly, London, 1871.]

_______________

Notes:

1 Report, 1800.

2 Ibid. 1801.

3 Report, 1S02.

4 Ibid. 1803.

5 Pioneers of the Bengal Mission, p. 60.

6 Protestant Missions in India (1884), M. A. Sherring, p. 80.