Part 2 of 2

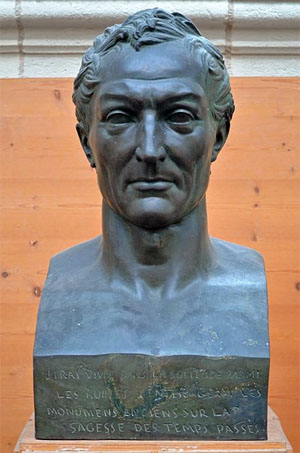

Influence on Western thinkersAn exchange of ideas has been taking place between the western world and Asia since the late 18th century as a result of colonization of parts of Asia by Western powers. This also influenced western religiosity. The first translation of Upanishads, published in two parts in 1801 and 1802, significantly influenced

Arthur Schopenhauer, who called them the consolation of his life.[183] He drew explicit parallels between his philosophy, as set out in The World as Will and Representation,[184] and that of the Vedanta philosophy as described in the work of Sir William Jones.[185] Early translations also appeared in other European languages.[186] Influenced by Śaṅkara's concepts of Brahman (God) and māyā (illusion), Lucian Blaga often used the concepts marele anonim (the Great Anonymous) and cenzura transcendentă (the transcendental censorship) in his philosophy.[187]

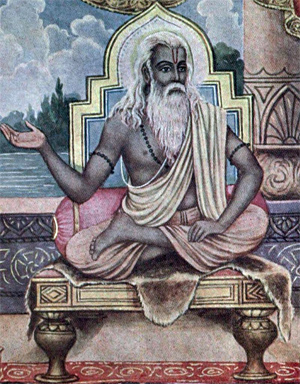

Similarities with Spinoza's philosophyGerman Sanskritist Theodore Goldstücker was among the early scholars to notice similarities between the religious conceptions of the Vedanta and those of the Dutch Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza, writing that Spinoza's thought was... so exact a representation of the ideas of the Vedanta, that we might have suspected its founder to have borrowed the fundamental principles of his system from the Hindus, did his biography not satisfy us that he was wholly unacquainted with their doctrines [...] comparing the fundamental ideas of both we should have no difficulty in proving that, had Spinoza been a Hindu, his system would in all probability mark a last phase of the Vedanta philosophy.[188]

Max Müller noted the striking similarities between Vedanta and the system of Spinoza, saying,The Brahman, as conceived in the Upanishads and defined by Sankara, is clearly the same as Spinoza's 'Substantia'."[189]

Helena Blavatsky, a founder of the Theosophical Society, also compared Spinoza's religious thought to Vedanta, writing in an unfinished essay,As to Spinoza's Deity – natura naturans – conceived in his attributes simply and alone; and the same Deity – as natura naturata or as conceived in the endless series of modifications or correlations, the direct outflowing results from the properties of these attributes, it is the Vedantic Deity pure and simple.[190]

See also• Badarayana

• Monistic idealism

• List of teachers of Vedanta

• Self-consciousness (Vedanta)

• Śāstra pramāṇam in Hinduism

Notes1. Historically, Vedanta has been called by various names. The early names were the Upanishadic ones (Aupanisada), the doctrine of the end of the Vedas (Vedanta-vada), the doctrine of Brahman(Brahma-vada), and the doctrine that Brahma is the cause (Brahma-karana-vada).[28]

2. The Upanishads were many in number and developed in the different schools at different times and places, some in the Vedic period and others in the medieval or modern era (the names of up to 112 Upanishads have been recorded).[34] All major commentators have considered twelve to thirteen oldest of these texts as the Principal Upanishads and as the foundation of Vedanta.

3. A few Indian scholars such as Vedvyasa discuss ten; Krtakoti discusses eight; six is most widely accepted: see Nicholson (2010, pp. 149–150)

4. Anantanand Rambachan (1991, pp. xii–xiii) states, "According to these [widely represented contemporary] studies, Shankara only accorded a provisional validity to the knowledge gained by inquiry into the words of the Śruti (Vedas) and did not see the latter as the unique source (pramana) of Brahmajnana. The affirmations of the Śruti, it is argued, need to be verified and confirmed by the knowledge gained through direct experience (anubhava) and the authority of the Śruti, therefore, is only secondary." Sengaku Mayeda (2006, pp. 46–47) concurs, adding Shankara maintained the need for objectivity in the process of gaining knowledge (vastutantra), and considered subjective opinions (purushatantra) and injunctions in Śruti (codanatantra) as secondary. Mayeda cites Shankara's explicit statements emphasizing epistemology (pramana–janya) in section 1.18.133 of Upadesasahasri and section 1.1.4 of Brahmasutra–bhasya.

5. Nicholson (2010, p. 27) writes of Advaita Vedantin position of cause and effect - Although Brahman seems to undergo a transformation, in fact no real change takes place. The myriad of beings are essentially unreal, as the only real being is Brahman, that ultimate reality which is unborn, unchanging, and entirely without parts.

6. Sivananda also mentions Meykandar and the Shaiva Siddhanta philosophy.[65]

7. Proponents of other Vedantic schools continue to write and develop their ideas as well, although their works are not widely known outside of smaller circles of followers in India.

8. According to Nakamura and Dasgupta, the Brahmasutras reflect a Bhedabheda point of view,[5]the most influential tradition of Vedanta before Shankara. Numerous Indologists, including Surendranath Dasgupta, Paul hacker, Hajime Nakamura, and Mysore Hiriyanna, have described Bhedabheda as the most influential school of Vedanta before Shankara.[5]

9. Doniger (1986, p. 119) says "that to say that the universe is an illusion (māyā) is not to say that it is unreal; it is to say, instead, that it is not what it seems to be, that it is something constantly being made. Maya not only deceives people about the things they think they know; more basically, it limits their knowledge."

10. The concept of Brahman in Dvaita Vedanta is so similar to the monotheistic eternal God, that some early colonial–era Indologists such as George Abraham Grierson suggested Madhva was influenced by early Christians who migrated to India, [90] but later scholarship has rejected this theory.[91]

11. Nicholson (2010, p. 26) considers the Brahma Sutras as a group of sutras composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years. The precise date is disputed.[98] Nicholson (2010, p. 26) estimates that the book was composed in its current form between 400 and 450 CE. The reference shows BCE, but it´s a typo in Nicholson´s book

12. The Vedanta–sūtra are known by a variety of names, including (1) Brahma–sūtra, (2) Śārīraka–sutra, (3) Bādarāyaṇa–sūtra and (4) Uttara–mīmāṁsā.

13. Estimates of the date of Bādarāyana's lifetime differ. Pandey 2000, p. 4

14. Nicholson 2013, p. 26 Quote: "From a historical perspective, the Brahmasutras are best understood as a group of sutras composed by multiple authors over the course of hundreds of years, most likely composed in its current form between 400 and 450 BCE." This dating has a typo in Nicholson's book, it should be read "between 400 and 450 CE"

15. Bhartŗhari (c. 450–500), Upavarsa (c. 450–500), Bodhāyana (c. 500), Tanka (Brahmānandin) (c. 500–550), Dravida (c. 550), Bhartŗprapañca (c. 550), Śabarasvāmin (c. 550), Bhartŗmitra (c. 550–600), Śrivatsānka (c. 600), Sundarapāndya (c. 600), Brahmadatta (c. 600–700), Gaudapada (c. 640–690), Govinda (c. 670–720), Mandanamiśra (c. 670–750)[96]

16. There is ample evidence, however, to suggest that Advaita was a thriving tradition by the start of the common era or even before that. Shankara mentions 99 different predecessors of his Sampradaya.[112] Scholarship since 1950 suggests that almost all Sannyasa Upanishads have a strong Advaita Vedanta outlook.[116] Six Sannyasa Upanishads – Aruni, Kundika, Kathashruti, Paramahamsa, Jabala and Brahma – were composed before the 3rd Century CE, likely in the centuries before or after the start of the common era; the Asrama Upanishad is dated to the 3rd Century.[117] The strong Advaita Vedanta views in these ancient Sannyasa Upanishads may be, states Patrick Olivelle, because major Hindu monasteries of this period belonged to the Advaita Vedanta tradition.[118]

17. Scholars like Raju (1992, p. 177), following the lead of earlier scholars like Sengupta,[120] believe that Gaudapada co-opted the Buddhist doctrine that ultimate reality is pure consciousness (vijñapti-mātra). Raju (1992, pp. 177–178) states, "Gaudapada wove [both doctrines] into a philosophy of the Mandukaya Upanisad, which was further developed by Shankara." Nikhilananda (2008, pp. 203–206) states that the whole purpose of Gaudapada was to present and demonstrate the ultimate reality of Atman, an idea denied by Buddhism. According to Murti (1955, pp. 114–115), Gaudapada's doctrines are unlike Buddhism. Gaudapada's influential text consists of four chapters: Chapters One, Two, and Three are entirely Vedantin and founded on the Upanishads, with little Buddhist flavor. Chapter Four uses Buddhist terminology and incorporates Buddhist doctrines but Vedanta scholars who followed Gaudapada through the 17th century, state that both Murti and Richard King never referenced nor used Chapter Four, they only quote from the first three.[10] While there is shared terminology, the doctrines of Gaudapada and Buddhism are fundamentally different, states Murti (1955, pp. 114–115)

18. Nicholson (2010, p. 27) writes: "The Brahmasutras themselves espouse the realist Parinamavada position, which appears to have been the view most common among early Vedantins."

19. Shankara synthesized the Advaita–vāda which had previously existed before him,[123] and, in this synthesis, became the restorer & defender of an ancient learning.[124] He was an unequaled commentator,[124] due to whose efforts and contributions,[123] Advaita Vedanta assumed a dominant position within Indian philosophy.[124]

20. According to Mishra, the sutras, beginning with the first sutra of Jaimini and ending with the last sutra of Badarayana, form one compact shastra.[125]

21. Many sources date him to 1238–1317 period,[141] but some place him over 1199–1278 CE.[142]

22. Vishishtadvaita roots:

* Supreme Court of India, 1966 AIR 1119, 1966 SCR (3) 242: "Philosophically, Swaminarayan was a follower of Ramanuja"[154]

* Hanna H. Kim: "The philosophical foundation for Swaminarayan devotionalism is the viśiṣṭādvaita, or qualified non-dualism, of Rāmānuja (1017–1137 ce)."[153]

23. "Professor Ashok Aklujkar said [...] Just as the Kashi Vidvat Parishad acknowledged Swaminarayan Bhagwan’s Akshar-Purushottam Darshan as a distinct darshan in the Vedanta tradition, we are honored to do the same from the platform of the World Sanskrit Conference [...] Professor George Cardona [said] "This is a very important classical Sanskrit commentary that very clearly and effectively explains that Akshar is distinct from Purushottam."[66]

24. Vivekananda, clarifies Richard King, stated, "I am not a Buddhist, as you have heard, and yet I am"; but thereafter Vivekananda explained that "he cannot accept the Buddhist rejection of a self, but nevertheless honors the Buddha's compassion and attitude towards others".[164]

25. The tendency of "a blurring of philosophical distinctions" has also been noted by Burley.[169]Lorenzen locates the origins of a distinct Hindu identity in the interaction between Muslims and Hindus,[170] and a process of "mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim other",[171] which started well before 1800.[172]

References1. Flood 1996, p. 239.

2. Flood 1996, p. 133.

3. Dandekar 1987.

4. Nicholson.

5. Nicholson 2010, p. 26.

6. Pahlajrai, Prem. "Vedanta: A Comparative Analysis of Diverse Schools" (PDF). Asian Languages and Literature. University of Washington.

7. Malkovsky 2001, p. 118.

8. Ramnarace 2014, p. 180.

9. Sivananda 1993, p. 248.

10. Jagannathan 2011.

11. Comans 2000, p. 163.

12. King 1999, p. 135.

13. Flood 1996, p. 258.

14. King 2002, p. 93.

15. Williams 2018.

16. Sharma 2008, p. 2–10.

17. Cornille 2019.

18. Flood 1996, pp. 238, 246.

19. Chatterjee & Dutta 2007, pp. 317–318.

20. Flood 1996, pp. 231–232, 238.

21. Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 19, 21–25, 150–152.

22. Koller 2013, pp. 100–106; Sharma 1994, p. 211

23. Raju 1992, pp. 176–177; Isaeva 1992, p. 35 with footnote 30

24. Raju 1992, pp. 176–177.

25. Scharfe 2002, pp. 58–59, 115–120, 282–283.

26. Clooney 2000, pp. 147–158.

27. Jaimini 1999, p. 16, Sutra 30.

28. King 1995, p. 268 with note 2.

29. Fowler 2002, pp. 34, 66; Flood 1996, pp. 238–239

30. Fowler 2002, pp. 34, 66.

31. Das 1952; Doniger & Stefon 2015; Lochtefeld 2000, p. 122; Sheridan 1991, p. 136

32. Doniger & Stefon 2015.

33. Ranganathan; Grimes 1990, pp. 6–7

34. Dasgupta 2012, pp. 28.

35. Pasricha 2008, p. 95.

36. Raju 1992, pp. 176–177, 505–506; Fowler 2002, pp. 49–59, 254, 269, 294–295, 345

37. Das 1952; Puligandla 1997, p. 222

38. Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 51; Johnson 2009, p. 'see entry for Atman(self)'

39. Lipner 1986, pp. 40–41, 51–56, 144; Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 23, 78, 158–162

40. Chari 1988, pp. 2, 383.

41. Fowler 2002, p. 317; Chari 1988, pp. 2, 383

42. "Dvaita". Britannica. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

43. Stoker 2011.

44. Vitsaxis 2009, pp. 100–101.

45. Raju 1992, p. 177.

46. Raju 1992, p. 177; Stoker 2011

47. Ādidevānanda 2014, pp. 9-10.

48. Betty 2010, pp. 215–224; Stoker 2011; Chari 1988, pp. 2, 383

49. Craig 2000, pp. 517–18; Stoker 2011; Bryant 2007, pp. 361–363

50. Bryant 2007, pp. 479–481.

51. Lochtefeld 2000, pp. 520–521; Chari 1988, pp. 73–76

52. Lochtefeld 2000, pp. 520–521.

53. Potter 2002, pp. 25–26; Bhawuk 2011, p. 172

54. Bhawuk 2011, p. 172; Chari 1988, pp. 73–76; Flood 1996, pp. 225

55. Grimes 2006, p. 238; Puligandla 1997, p. 228; Clayton 2006, pp. 53–54

56. Grimes 2006, p. 238.

57. Indich 1995, pp. 65; Gupta 1995, pp. 137–166

58. Fowler 2002, p. 304; Puligandla 1997, pp. 208–211, 237–239; Sharma 2000, pp. 147–151

59. Nicholson 2010, p. 27.

60. Balasubramanian 2000, pp. xxx–xxxiiii.

61. Deutsch & Dalvi 2004, pp. 95–96.

62. Flood 1996, p. 246.

63. Flood 1996, p. 238.

64. Sivananda 1993, p. 216.

65. Sivananda 1993, p. 217.

66. "HH Mahant Swami Maharaj Inaugurates the Svāminārāyaṇasiddhāntasudhā and Announces Parabrahman Svāminārāyaṇa's Darśana as the Akṣara-Puruṣottama Darśana". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. 17 September 2017.

67. "Acclamation by th Sri Kasi Vidvat Parisad". BAPS Swaminarayan Sanstha. 31 July 2017.

68. Paramtattvadas 2019, p. 40.

69. Williams 2018, p. 38.

70. Nicholson; Sivananda 1993, p. 247

71. "Nimbarka". Encyclopedia Britannica.

72. Sharma 1994, p. 376.

73. Sivananda 1993, p. 247.

74. Bryant 2007, p. 407; Gupta 2007, pp. 47–52

75. Bryant 2007, pp. 378–380.

76. Gupta 2016, pp. 44–45.

77. Das 1952; Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 160–161; Doniger 1986, p. 119

78. Das 1952.

79. Sharma 2007, pp. 19–40, 53–58, 79–86.

80. Indich 1995, pp. 1–2, 97–102; Etter 2006, pp. 57–60, 63–65; Perrett 2013, pp. 247–248

81. "Similarity to Brahman". The Hindu. 6 January 2020. Retrieved 2020-01-11 – via

http://www.pressreader.com.

82. Betty 2010, pp. 215–224; Craig 2000, pp. 517–518

83. Bartley 2013, pp. 1–2, 9–10, 76–79, 87–98; Sullivan 2001, p. 239; Doyle 2006, pp. 59–62

84. Etter 2006, pp. 57–60, 63–65; van Buitenin 2010

85. Schultz 1981, pp. 81–84.

86. van Buitenin 2010.

87. Schultz 1981, pp. 81–84; van Buitenin 2010; Sydnor 2012, pp. 84–87

88. Stoker 2011; von Dehsen 1999, p. 118

89. Sharma 1962, pp. 353–354.

90. Kulandran & Hendrik 2004, pp. 177–179.

91. Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 266; Sarma 2000, pp. 19–21

92. Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 266; Sharma 1962, pp. 417–424; Sharma 1994, p. 373

93. Sharma 1994, pp. 374–375; Bryant 2007, pp. 361–362

94. Sharma 1994, p. 374.

95. Bryant 2007, pp. 479-481.

96. Nakamura 2004, p. 3.

97. Nakamura 1989, p. 436. "... we can take it that 400-450 is the period during which the Brahma-sūtra was compiled in its extant form."

98. Lochtefeld 2000, p. 746; Nakamura 1949, p. 436

99. Balasubramanian 2000, p. xxxiii.

100. Sharma 1996, pp. 124–125.

101. Nakamura 2004, p. 3; Sharma 1996, pp. 124–125

102. Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 19, 21–25, 151–152; Sharma 1994, pp. 239–241; Nicholson 2010, p. 26

103. Chatterjee & Dutta 2007, p. 317.

104. Sharma 2009, pp. 239–241.

105. "Historical Development of Indian Philosophy". Britannica.

106. Lochtefeld 2000, p. 746.

107. Nakamura 1949, p. 436.

108. Isaeva 1992, p. 36.

109. Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 151–152.

110. Nicholson 2010, pp. 26–27; Mohanty & Wharton 2011

111. Nakamura 2004, p. 426.

112. Roodurmum 2002, p. [page needed].

113. Comans 2000, p. 163; Jagannathan 2011

114. Comans 2000, pp. 2, 163.

115. Sharma 1994, p. 239.

116. Olivelle 1992, pp. 17–18; Rigopoulos 1998, pp. 62–63; Phillips 1995, p. 332 with note 68

117. Olivelle 1992, pp. x–xi, 8–18; Sprockhoff 1976, pp. 277–294, 319–377

118. Olivelle 1992, pp. 17–18.

119. Sharma 1994, p. 239; Nikhilananda 2008, pp. 203–206; Nakamura 2004, p. 308; Sharma 1994, p. 239

120. Nikhilananda 2008, pp. 203–206.

121. Sharma 2000, p. 64.

122. Nakamura 2004; Sharma 2000, p. 64

123. Nakamura 2004, p. 678.

124. Nakamura 2004, p. 679.

125. Sharma 1994, pp. 239–241, 372–375.

126. Raju 1992, p. 175-176.

127. Sharma 1994, p. 340.

128. Mohanty & Wharton 2011.

129. Smith 1976, pp. 143–156.

130. Schomer & McLeod 1987, pp. 1–5.

131. Gupta & Valpey 2013, pp. 2–10.

132. Bartley 2013, pp. 1–4, 52–53, 79.

133. Beck 2012, p. 6.

134. Jackson 1992; Jackson 1991; Hawley 2015, pp. 304–310.

135. Bartley 2013, p. 1-4.

136. Sullivan 2001, p. 239; Schultz 1981, pp. 81–84; Bartley 2013, pp. 1–2; Carman 1974, p. 24

137. Olivelle 1992, pp. 10–11, 17–18; Bartley 2013, pp. 1–4, 52–53, 79

138. Carman 1994, pp. 82–87 with footnotes.

139. Bernard 1947, pp. 9–12; Sydnor 2012, pp. 0–11, 20–22

140. Fowler 2002, p. 288.

141. Bryant 2007, pp. 12–13, 359–361; Sharma 2000, pp. 77–78

142. Jones & Ryan 2006, p. 266.

143. Bernard 1947, pp. 9–12.

144. Hiriyanna 2008, p. 187.

145. Sheridan 1991, p. 117.

146. von Dehsen 1999, p. 118.

147. Sharma 2000, pp. 79-80.

148. Sharma 1962, pp. 128–129, 180–181; Sharma 1994, pp. 150–151, 372, 433–434; Sharma 2000, pp. 80–81

149. Sharma 1994, pp. 372–375.

150. Hiriyanna 2008, pp. 188–189.

151. Lochtefeld 2000, p. 396; Stoker 2011

152. Delmonico, Neal (4 April 2004). "Caitanya Vais.n. avism and the Holy Names" (PDF). Bhajan Kutir. Retrieved 2017-05-29.

153. Kim 2005.

154. Gajendragadkar 1966.

155. Aksharananddas & Bhadreshdas 2016, p. [page needed].

156. Paramtattvadas 2017, p. 3.

157. Swaminarayan's teachings, p. 40.[full citation needed]

158. King 1999, p. 135; Flood 1996, p. 258; King 2002, p. 93

159. King 1999, pp. 187, 135–142.

160. King 2002, p. 118.

161. King 1999, p. 137.

162. Halbfass 2007, p. 307.

163. King 2002, p. 135.

164. King 1999, p. 138.

165. King 1999, pp. 133–136.

166. King 2002, pp. 135–142.

167. von Dense 1999, p. 191.

168. Mukerji 1983.

169. Burley 2007, p. 34.

170. Lorenzen 2006, p. 24–33.

171. Lorenzen 2006, p. 27.

172. Lorenzen 2006, p. 26–27.

173. Witz 1998, p. 11; Schuon 1975, p. 91

174. Clooney 2000, pp. 96–107.

175. Brooks 1990, pp. 20–22, 77–79; Nakamura 2004, p. 3

176. Carman & Narayanan 1989, pp. 3–4.

177. Neog 1980, pp. 243–244.

178. Smith 2003, pp. 126–128; Klostermaier 1984, pp. 177–178

179. Davis 2014, p. 167 note 21; Dyczkowski 1989, pp. 43–44

180. Vasugupta 2012, pp. 252, 259; Flood 1996, pp. 162–167

181. Manninezhath 1993, pp. xv, 31.

182. McDaniel 2004, pp. 89–91; Brooks 1990, pp. 35–39; Mahony 1997, p. 274 with note 73

183. Renard 2010, pp. 177–178.

184. Schopenhauer 1966, p. [page needed].

185. Jones 1801, p. 164.

186. Renard 2010, p. 183-184.

187. Iţu 2007.

188. Goldstucker 1879, p. 32.

189. Muller 2003, p. 123.

190. Blavatsky 1982, pp. 308–310.

Sources

Printed sources• Ādidevānanda, Swami (2014). Śrī Rāmānuja GĪTĀ Bhāșya, with Text and English translation. Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math, Mylapore, Chennai. ISBN 9788178235189.

• Aksharananddas, Sadhu; Bhadreshdas, Sadhu (2016). Swaminarayan's Brahmajnana as Aksarabrahma-Parabrahma-Darsanam. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199463749.003.0011. ISBN 9780199086573.

• Balasubramanian, R. (2000). "Introduction". In Chattopadhyana (ed.). History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. Volume II Part 2: Advaita Vedanta". Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations.

• Bartley, C.J. (2013). The Theology of Ramanuja : Realism and Religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-85306-7.

• Beck, Guy L. (2005), "Krishna as Loving Husband of God", Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1

• Beck, Guy L. (2012), Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-8341-1

• Bernard, Theos (1947). Hindu Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-1373-1.

• Betty, Stafford (2010). "Dvaita, Advaita, and Viśiṣṭādvaita: Contrasting Views of Mokṣa". Asian Philosophy. 20 (2): 215–224. doi:10.1080/09552367.2010.484955. S2CID 144372321.

• Bhawuk, D.P.S. (2011). Anthony Marsella (ed.). Spirituality and Indian Psychology. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-8109-7.

• Blavatsky, H.P. (1982). Collected Writings. 13. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publ. House. ISBN 978-0835602297.

• Brahmbhatt, Arun (2016), "The Swaminarayan Commentarial Tradition", in Williams, Raymond Brady; Yogi Trivedi (eds.), Swaminarayan Hinduism: Tradition, Adaptation, and Identity, Oxford University Press

• Brooks, Douglas Renfrew (1990). The Secret of the Three Cities. State University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-22607-569-3.

• Bryant, Edwin (2007). Krishna : A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195148923.

• Burley, Mikel (2007). Classical Samkhya and Yoga: An Indian Metaphysics of Experience. Taylor & Francis.

• Carman, John B. (1994). Majesty and Meekness: A Comparative Study of Contrast and Harmony in the Concept of God. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0802806932.

• Carman, John B. (1974). The Theology of Rāmānuja: An essay in inter-religious understanding. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300015218.

• Carman, John; Narayanan, Vasudha (1989). The Tamil Veda: Pillan's Interpretation of the Tiruvaymoli. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-09306-2.

• Chari, S. M. Srinivasa (2004) [1988]. Fundamentals of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta (Corr. ed.). Motilal Banarasidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0266-7.

o Chari, S. M. Srinivasa (1988). Fundamentals of Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedanta. Motilal Banarasidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0266-7. OCLC 463617682.

• Chatterjee, Satischandra; Dutta, Shirendramohan (2007) [1939]. An Introduction to Indian Philosophy(Reprint ed.). Rupa Publications India Pvt. Limited. ISBN 978-81-291-1195-1.

• Clayton, John (2006). Religions, Reasons and Gods: Essays in Cross-cultural Philosophy of Religion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45926-6.

• Clooney, Francis X. (2000). Ultimate Realities: A Volume in the Comparative Religious Ideas Project. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-79144-775-8.

• Comans, Michael (1996). "Śankara and the Prasankhyanavada". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 24 (1). doi:10.1007/bf00219276. S2CID 170656129.

• Comans, Michael (2000). The Method of Early Advaita Vedānta: A Study of Gauḍapāda, Śaṅkara, Sureśvara, and Padmapāda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1722-7.

• Cornille, Catherine (2019). "Is all Hindu theology comparative theology?". Harvard Theological Review. 112 (1): 126–132. doi:10.1017/S0017816018000378. ISSN 0017-8160.

• Craig, Edward (2000). Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415223645.

• Dandekar, R. (1987), "Vedanta", MacMillan Encyclopedia of religion

• Das, A.C. (1952). "Brahman and Māyā in Advaita Metaphysics". Philosophy East and West. 2 (2): 144–154. doi:10.2307/1397304. JSTOR 1397304.

• Dasgupta, Surendranath (2012) [1922]. A History of Indian Philosophy. Vol. 1, Philosophy of Buddhist, Jaina and Six Systems of indian thought (7th Reprint ed.). Motilal Banarasidas Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-0412-8.

• Davis, Richard (2014). Ritual in an Oscillating Universe: Worshipping Siva in Medieval India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691603087.

• von Dehsen, Christian (1999). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Routledge. ISBN 978-1573561525.

• von Dense, Christian D. (1999). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Greenwood Publishing Group.

• Deutsch, Eliot; Dalvi, Rohit (2004). The Essential Vedanta: A New Source Book of Advaita Vedanta. World Wisdom, Inc. ISBN 9780941532525.

• Doniger, Doniger (1986). Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226618555.

• Doyle, Sean (2006). Synthesizing the Vedanta: The Theology of Pierre Johanns, S.J. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03910-708-7.

• Dyczkowski, Mark (1989). The Canon of the Śaivāgama. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120805958.

• Etter, Christopher (2006). A Study of Qualitative Non-Pluralism. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-39312-1.

• Flood, Gavin Dennis (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press.

• Fowler, Jeaneane D. (2002). Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-898723-94-3.

• Gajendragadkar, P. (1966), Supreme Court of India: Sastri Yagnapurushadji And ... vs Muldas Brudardas Vaishya And ... on 14 January, 1966. 1966 AIR 1119, 1966 SCR (3) 242

• Gier, Nicholas F. (2000). Spiritual Titanism: Indian, Chinese, and Western Perspectives. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4528-0.

• Gier, Nicholas F. (2012). "Overreaching to be different: A critique of Rajiv Malhotra's Being Different". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 16 (3): 259–285. doi:10.1007/s11407-012-9127-x. ISSN 1022-4556. S2CID 144711827.

• Goldstucker, Theodore (1879). Literary Remains of the Late Professor Theodore Goldstucker. London: W. H. Allen & Co.

• Goswāmi, S.D. (1976). Readings in Vedic Literature: The Tradition Speaks for Itself. ISBN 978-0-912776-88-0.

• Grimes, John A. (2006). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791430675.

• Grimes, John A. (1990). The Seven Great Untenables: Sapta-vidhā Anupapatti. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0682-5.

• Gupta, Bina (1995). Perceiving in Advaita Vedānta: Epistemological Analysis and Interpretation. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 137–166. ISBN 978-81-208-1296-3.

• Gupta, Ravi M. (2016). Caitanya Vaisnava Philosophy: Tradition, Reason and Devotion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-17017-4.

• Gupta, Ravi M. (2007). Caitanya Vaisnava Vedanta of Jiva Gosvami's Catursutri tika. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-40548-5.

• Gupta, Ravi; Valpey, Kenneth (2013). The Bhagavata Purana: Sacred Text and Living Tradition. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14999-0.

• Halbfass, Wilhelm (2007). "Research and reflection: Responses to my respondents. V. Developments and attitudes in Neo-Hinduism; Indian religion, past and present (Responses to Chapters 4 and 5)". In Franco, Eli; Preisendanz, Karin (eds.). Beyond Orientalism: the work of Wilhelm Halbfass and its impact on Indian and cross-cultural studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-8120831100.

• Hawley, John Stratton (2015). A Storm of Songs: India and the Idea of the Bhakti Movement. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674187467.

• Hiriyanna, M. (2008) [1948]. The Essentials of Indian Philosophy (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-81-208-1330-4. OCLC 889316366.[verification needed]

—OR—

Raju, P. T. (1972). The Philosophical Traditions of India. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-1105-0. OCLC 482322.

• Indich, William M. (1995). Consciousness in Advaita Vedanta. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1251-2.

• Isaeva, N.V. (1992). Shankara and Indian Philosophy. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1281-7.

• Isaeva, N.V. (1995). From Early Vedanta to Kashmir Shaivism: Gaudapada, Bhartrhari, and Abhinavagupta. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2449-0.

• Iţu, Mircia (2007). "Marele Anonim şi cenzura transcendentă la Blaga. Brahman şi māyā la Śaṅkara" [The Great Anonymous and the transcendent censorship at Blaga. Brahman and māyā at Śaṅkara]. Caiete critice (in Romanian). Bucharest. 6–7 (236–237): 75–83. ISSN 1220-6350..

• Jackson, W.J. (1992), "A Life Becomes a Legend: Sri Tyagaraja as Exemplar", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 60 (4): 717–736, doi:10.1093/jaarel/lx.4.717, JSTOR 1465591

• Jackson, W.J. (1991), Tyagaraja: Life and Lyrics, Oxford University Press, USA

• Jaimini (1999). Mīmāṃsā Sūtras of Jaimini. Translated by Mohan Lal Sandal (Reprint ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1129-4.

• Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing.

• Johnson, W.J. (2009). A Dictionary of Hinduism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198610250.

• Jones, Sir William (1801). "On the Philosophy of the Asiatics". Asiatic Researches. 4. pp. 157–173.

• Kim, Hanna H. (2005), "Swaminarayan movement", MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religion

• King, Richard (1995). Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: The Mahāyāna Context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā. SUNY Press.

• King, Richard (1999). Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East". Routledge.

• King, Richard (2002). Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East". Taylor & Francis e-Library.

• Klostermaier, Klaus K. (1984). Mythologies and Philosophies of Salvation in the Theistic Traditions of India. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-158-3.

• Koller, John M. (2013). "Shankara". In Meister, Chad; Copan, Paul (eds.). Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Routledge.

• Kulandran, Sabapathy; Hendrik, Kraemer (2004). Grace in Christianity and Hinduism. ISBN 978-0227172360.

• Lochtefeld, James (2000). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931798.

• Lipner, Julius J. (1986). The Face of Truth: A Study of Meaning and Metaphysics in the Vedantic Theology of Ramanuja. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-038-0.

• Lorenzen, David N. (2006). Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History. Yoda Press. ISBN 9788190227261.

• Mahony, William (1997). The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791435809.

• Malkovsky, B. (2001), The Role of Divine Grace in the Soteriology of Śaṁkarācārya, BRILL

• Manninezhath, Thomas (1993). Harmony of Religions: Vedānta Siddhānta Samarasam of Tāyumānavar. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1001-3.

• Matilal, Bimal Krishna (2015) [2002]. Ganeri, Jonardon (ed.). The Collected Essays of Bimal Krishna Matilal. 1 (Reprint ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-946094-6.

o Matilal, Bimal Krishna (2002). Ganeri, Jonardon (ed.). The Collected Essays of Bimal Krishna Matilal. 1. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-564436-4.

• Mayeda, Sengaku (2006). A thousand teachings : the Upadeśasāhasrī of Śaṅkara. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2771-4.

• McDaniel, June (2004). Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534713-5.

• Mukerji, Mādhava Bithika (1983). Neo-Vedanta and Modernity. Ashutosh Prakashan Sansthan.

• Muller, F. Max (2003). Three Lectures on the Vedanta Philosophy. Kessinger Publishing.

• Murti, T.R.V. (2008) [1955]. The central philosophy of Buddhism (Reprint ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-46118-4.

o Murti, T.R.V. (1955). The central philosophy of Buddhism. London: Allen & Unwin. OCLC 1070871178.

• Nakamura, Hajime (1990) [1949]. A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Part 1 (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. ISBN 978-81-208-0651-1.

o Nakamura, Hajime (1989). A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy, Part 1. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0651-1. OCLC 963971598.

o Nakamura, Hajime (1949). A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy. ,[full citation needed]

• Nakamura, Hajime (2004) [1950]. A History of Early Vedānta Philosophy. Part 2 (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. ISBN 978-8120819634.

• Nicholson, Andrew J. (2010). Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14987-7.

• Nicholson, Andrew J. (2013). Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14987-7.

• Neog, Maheswar (1980). Early History of the Vaiṣṇava Faith and Movement in Assam: Śaṅkaradeva and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0007-6.

• Nikhilananda, Swami (2008). The Upanishads, A New Translation. 2. Kolkata: Advaita Ashrama. ISBN 978-81-7505-302-1.

• Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7.

• Pandey, S. L. (2000). "Pre-Sankara Advaita". In Chattopadhyana (ed.). History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. Volume II Part 2: Advaita Vedanta. Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations.

• Paramtattvadas, Sadhu (2017). An introduction to Swaminarayan Hindu theology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-15867-2. OCLC 964861190.

• Paramtattvadas, Swami (October–December 2019). "Akshar-Purushottam School of Vedanta". Hinduism Today. Himalayan Academy. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

• Pasricha, Ashu (2008). "The Political Thought of C. Rajagopalachari". Encyclopaedia of Eminent Thinkers. 15. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788180694950.

• Patel, Iva (2018), "Swaminarayan", in Jain, P.; Sherma, R.; Khanna, M. (eds.), Hinduism and Tribal Religions. Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, Springer, Dordrecht, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1007/978-94-024-1036-5_541-1, ISBN 978-94-024-1036-5

• Perrett, Roy W. (2013). Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-70322-6.

• Phillips, Stephen H. (1995). Classical Indian Metaphysics. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0812692983.

• Phillips, Stephen (2000). Perrett, Roy W. (ed.). Epistemology: Indian Philosophy. 1. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-3609-9.

• Potter, Karl (2002). Presuppositions of India's Philosophies. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0779-2.

• Puligandla, Ramakrishna (1997). Fundamentals of Indian Philosophy. New Delhi: D. K. Printworld (P) Ltd.

• Raju, P.T. (1992) [1972]. The Philosophical Traditions of India (Reprint ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited.

• Rambachan, A. (1991). Accomplishing the Accomplished: Vedas as a Source of Valid Knowledge in Sankara. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1358-1.

• Ramnarace, Vijay (2014), Rādhā-Kṛṣṇa's Vedāntic Debut: Chronology & Rationalisation in the Nimbārka Sampradāya (PDF)

• Renard, Philip (2010). Non-Dualisme. De directe bevrijdingsweg. Cothen: Uitgeverij Juwelenschip.

• Rigopoulos, Antonio (1998). Dattatreya: The Immortal Guru, Yogin, and Avatara. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791436967.

• Roodurmum, Pulasth Soobah (2002). Bhāmatī and Vivaraṇa Schools of Advaita Vedānta: A Critical Approach. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers.

• Sarma, Deepak (2005). Epistemologies and the Limitations of Philosophical Enquiry: Doctrine in Madhva Vedanta. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415308052.

• Sarma, Deepak (2000). "Is Jesus a Hindu? S.C. Vasu and Multiple Madhva Misrepresentations". Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies. 13. doi:10.7825/2164-6279.1228.

• Scharfe, Hartmut (2002). Handbook of Oriental Studies. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12556-8.

• Schomer, Karine; McLeod, W. H., eds. (1987). The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120802773.

• Schopenhauer, Arthur (1966). The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 1. Translated by Payne, E.F.J. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486217611.

• Schultz, Joseph P. (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-1707-6.

• Schuon, Frithjof (1975). "One of the Great Lights of the World". In Mahadevan, T.M.P. (ed.). Spiritual Perspectives, Essays in Mysticism and Metaphysics. Arnold Heinemann. ISBN 978-0892530212.

• Sharma, Arvind (2007). Advaita Vedānta: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120820272.

• Sharma, Arvind (2008). Philosophy of religion and Advaita Vedanta: a comparative study in religion and reason. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271028323. OCLC 759574543.

• Sharma, Chandradhar (2009) [1960]. A Critical Summary of Indian Philosophy. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0365-7. OCLC 884357528.

• Sharma, Chandradhar (1994) [1960]. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy (Reprint ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0365-7.

• Sharma, Chandradhar (2007) [1996]. The Advaita Tradition in Indian Philosophy: A Study of Advaita in Buddhism, Vedānta and Kāshmīra Shaivism (Rev. ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120813120. OCLC 190763026.

o Sharma, Chandradhar (1996). The Advaita Tradition in Indian Philosophy: A Study of Advaita in Buddhism, Vedānta and Kāshmīra Shaivism. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120813120. OCLC 1041414621.

• Sharma, B.N. Krishnamurti (2014) [1962]. Philosophy of Śrī Madhvācārya (Reprint ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120800687.

o Sharma, B.N. Krishnamurti (1962). Philosophy of Śrī Madhvācārya. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan March. OCLC 1075020345.

• Sharma, B. N. Krishnamurti (2000). A History of the Dvaita School of Vedānta and its Literature(Reprint, 3rd ed.). Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120815759. OCLC 53463855.

• Sheridan, Daniel (1991). Timm, Jeffrey (ed.). Texts in Context: Traditional Hermeneutics in South Asia. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791407967.

• Sivananda, Swami (1993). All About Hinduism. The Divine Life Society. ISBN 81-7052-047-9.

• Smith, Bardwell L. (1976). Hinduism: New Essays in the History of Religions. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-04495-1.

• Smith, David (2003). The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52865-8.

• Sprockhoff, Joachim F. (1976). Samnyasa: Quellenstudien zur Askese im Hinduismus (in German). Wiesbaden: Kommissionsverlag Franz Steiner. ISBN 978-3515019057.

• Sullivan, Bruce M. (2001). The A to Z of Hinduism. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-4070-6.

• Sydnor, Jon Paul (2012). Ramanuja and Schleiermacher: Toward a Constructive Comparative Theology. Casemate. ISBN 978-0227680247.

• Vasugupta, J.S. (2012). Śiva Sūtras, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120804074.

• Vitsaxis, Vassilis (2009). Thought and Faith: Comparative Philosophical and Religious Concepts in Ancient Greece, India, and Christianity: The Concept of Divinity: 2. Somerset Hall Press. ISBN 978-1-935244-05-9.

• Williams, Raymond Brady (2018), Introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism, Cambridge University Press

• Witz, Klaus G. (1998). The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniśads: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120815735.

Web sources• Mohanty, Jitendra N.; Wharton, Michael (2011). "Indian philosophy - Historical development of Indian philosophy". Britannica. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

• van Buitenin, J.A.B. (2010). "Ramanuja - Hindu theologian and philosopher". Britannica. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

• Doniger, Wendy; Stefon, Matt (2015). "Vedanta, Hindu Philosophy". Britannica. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

• Jagannathan, Devanathan (2011). "Gaudapada". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2016-08-29.

• Stoker, Valerie (2011). "Madhva (1238-1317)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

• Ranganathan, Shyam. "Hindu Philosophy". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

• Nicholson, Andrew J. "Bhedabheda Vedanta". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

Further reading• Parthasarathy, Swami. "The Eternities". Vedanta Treatise.

• Deussen, Paul (2007) [1912]. The System of Vedanta (Reprint ed.).

• Smith, Huston (1993). Forgotten Truth: The Primordial Tradition.

• Potter, Karl; Bhattachārya, Sibajiban. "Vedanta Sutras of Nārāyana Guru". Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies.

• Comparative analysis of commentaries on Vedanta Sutras.

https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.d ... edanta.pdf• Aurobindo, Sri (1972). "The Upanishads". Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram. Archived from the original on 2007-01-04.

• Parthasarathy, Swami. Choice Upanishads.

• Vrajaprana, Pravrajika. "A Simple Introduction". Vedanta.

• "VedantaHub.org". - Resources to help with the Study and Practice of Vedanta.