Part 4 of 4

Sir William Jones says, the only difficulty in deciding the situation of Palibothra to be the same as Patali-putra, to which the names and most circumstances nearly correspond, arose from hence, that the latter place extended from the confluence of the Sone and the Ganges to the site of Patna, whereas Palibothra stood at the junction of the Ganges and the Erannoboas; but this difficulty has been removed, by finding in a classical Sanscrit book, near two thousand years old, that Hiranyabahhee, or golden armed, which the Greeks changed into Erannoboas, or the river with a lovely murmur, was, in in fact, another name for the Sona itself, though Megasthenes, from ignorance or inattention, has named them separately.”

Vide Asiatic Researches, vol. IV. p. 11.

But this explanation will not be found sufficient to solve the difficulty, if Hiranyabaha be, as I conceive it is not, the proper name of a river; but an appellative, from an accident common to many rivers.Patali-putra was certainly the capital, and the residence of the kings of Magadha or south Behar.

In the Mudra Racshasa, of which I have related the argument, the capital city of Chandra-Gupta is called Cusumapoor throughout the piece,

except in one passage, where it seems to be confounded with Patali-putra, as if they were different names for the same place. In the passage alluded to, Racshasa asks one of his messengers, “If he had been at Cusumapoor?” the man replies, “Yes, I have been at Patali-putra.” But Sumapon, or

Phulwaree, to call it by its modern name, was, as the word imports, a pleasure or flower garden, belonging to the kings of Patna, and situate, indeed, about ten miles W.S.W, from that city,

but, certainly, never surrounded with fortifications, which Annanta, the author of the Mudra Racshasa says, the abode of Chandra-Gupta was.

It may be offered in excuse, for such blunders as these, that the authors of this, and the other poems and plays I have mentioned, written on the subject of Chandra-Gupta, which are certainly modern productions, were foreigners; inhabitants, if not natives, of the Deccan; at least Annanta was, for he declares that he lived on the banks of the Godaveri.

But though the foregoing considerations must place the authority of these writers far below the ancients, whom I have cited for the purpose of determining the situation of Palibothra; yet, if we consider the scene of action, in connexion with the incidents of the story, in the Mudra Racshasa, it will afford us clear evidence, that the city of Chandra-Gupta could not have stood on the site of Patna; and, a pretty strong presumption also, that

its real situation was where I have placed it, that is to say, at no great distance from where Raje-mehal now stands. For, first, the city was in the neighbourhood of some hills which lay to the southward of it.

Their situation is expressly mentioned; and for their contiguity, it may be inferred, though the precise distance be not set down from hence, that king Nanda's going out to hunt, his retiring to the reservoir, among the hills near Patalcandara, to quench his thirst, his murder there, and the subsequent return of the assassin to the city with his master's horse, are all occurrences related, as having happened on the same day. The messengers also who were sent by the young king after the discovery of the murder to fetch the body, executed their commission and returned to the city the same day.

These events are natural and probable, if the city of Chandra-gupta was on the site of Raje-mehal, or in the neighbourhood of that place,

but are utterly incredible, if applied to the situation of Patna, from which the hills recede at least thirty miles in any direction.

Again, Patalcandara in Sanscrit, signifies the crater of a volcano; and in fact,

the hills that form the glen, in which is situated the place now called Mootijarna, or the pearl dropping spring, agreeing perfectly in the circumstances of distance and direction from Raje-mehal with the reservoir of Patalcandara, as described in the poem, have very much the appearance of a crater of an old volcano. I cannot say I have ever been on the very spot, but I have observed in the neighbourhood, substances that bore undoubted marks of their being volcanic productions;

no such appearances are to be seen at Patna, nor any trace of there having ever been a volcano there, or near it.

Mr. Davis has given a curious description of Mootijarna, illustrated with elegant drawings.

He informs us there is a tradition, that the reservoir was built by Sultan Suja: perhaps he only repaired it.

The confusion Ananta and the other authors above alluded to, have made in the names of Patali-putra and Bali-putra, appears to me not difficult to be accounted for. While the sovereignty of the kings of Maghadha, or south Bahar, was exercised within the limits of their hereditary dominions, the seat of their government was Patali-putra, or Patya: but Janasandha, one of the ancestors of Chandra-Gupta, having subdued the whole of Prachi, as we read in the puranas, fixed his residence at Bali-putra, and there he suffered a most cruel death from Crishna and Bala Rama, who caused him to be split asunder.

Bala restored the son, Sahadeva, to his hereditary dominions; and from that time the kings of Maghadha, for twenty-four generations, reigned peaceably at Patna, until Nanda ascended the throne, who, proving an active and enterprising prince, subdued the whole of Prachi; and having thus recovered the conquests, that had been wrested from his ancestor, probably re-established the seat of empire at Bali-putra; the historians of Alexander positively assert, that he did.[???]

Thus while the kings of Palibothra, as Diodorus tells us, sunk into oblivion, through their sloth and inactivity, (a reproach which seems warranted by the utter absence observed of the posterity of Bala Rama in the puranas, not even their names being mentioned;) the princes of Patali-putra, by a contrary conduct, acquired a reputation that spread over all India: it was, therefore, natural for foreign authors, (for such, at lead, Ananta was,) especially in competitions of the dramatic kind, where the effect is oftentimes best produced by a neglect of historical precision, of two titles, to which their hero had an equal right to distinguish him by the most illustrious. The author of Sacontala has committed as great a mistake, in making Hastinapoor the residence of Dushmanta, which was not then in existence, having been built by Hasti, the fifth in descent from Dushmanta; before his time there was, indeed, a place of worship on the same spot, but no town.

The same author has fallen into another error, in assigning a situation of this city not far from the river Malini, (he should rather have said the rivulet that takes its name from a village now called Malyani, to the westward of Lahore: it is joined by a new channel to the Ravy;)

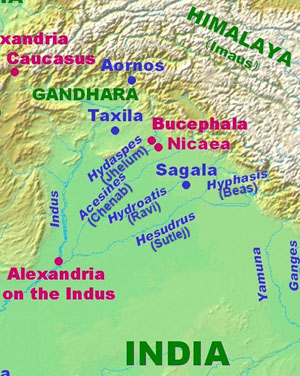

but this is a mistake; Hastinapoor lies on the banks of the old channel of the Ganges. The descendants of Peru resided at Sangala, whose extensive ruins are to be seen about fifty miles to the westward of Lahore, in a part of the country uninhabited.

I will take occasion to observe here, that Arrian has confounded Sangala with Salgada, or Salgana, or the mistake has been made by his copyists. Frontinus and Polyaenus have preserved the true name of this place, now called Calanore; and close to it is a deserted village, to this day called Salgheda;

its situation answers exactly to the description given of it by Alexander's historians. The kings of Sangala are known in the Persian history by the name of Schangal, one of them assisted Asrasiab against the famous Caicosru;

but to return from this digression to Patali-putra. Greek scholars often mentioned that Sandrocottus was the king of the country called as Prasii (Prachi or Prachya). Pracha or Prachi means eastern country. During the Nanda and Mauryan era, Magadha kings were ruling almost entire India. Mauryan Empire was never referred in Indian sources as only Prachya desa or eastern country. Prachya desa was generally referred to Gupta Empire because Northern Saka Ksatrapas and Western Saka Ksatrapas were well established in North and West India. Megasthenes mentioned that Sandrocottus is the greatest king of the Indians and Poros is still greater than Sandrocottus which means a kingdom in the North-western region is still independent and enjoying at least equal status with the kingdom of Sandrocottus.

-- Who was Sandrocottus: Samudragupta or Chandragupta Maurya?, The Chronology of Ancient India, Victim of Concoctions and Distortions, by Vedveer Arya]

The true name of this famous place is, Patali-pura, which means the town of Patali, a form of Devi worshipped there.

It was the residence of an adopted son of the goddess Patali, hence called Patali-putra, or the son of Patali. Patali-putra and Bali-putra are absolutely inadmissable, as Sanscrit names of towns and places; they are used in that sense, only in the spoken dialects; and this, of itself, is a proof, that the poems in question are modern productions. Patali-pura, or the town of Patali, was called simply Patali, or corruptly Pattiali, on the invasion of the Musulmans: it is mentioned under that name in Mr. Dow's translation of Ferishta's history.  Location of Sirhind in between Delhi and Lahore

Location of Sirhind in between Delhi and LahoreDelu is said to have been a prince of uncommon bravery and generosity; benevolent towards men, and devoted to the service of God. The most remarkable transaction of his reign is the building of the city of Delhi, which derives its name from its founder, Delu.

In the fortieth year of his reign, Phoor, a prince of his own family, who was governor of Cumaoon, rebelled against the Emperor, and marched to Kinoge, the capital. Delu was defeated, taken, and confined in the impregnable fort of Rhotas.

Phoor immediately mounted the throne of India, reduced Bengal, extended his power from sea to sea, and restored the empire to its pristine dignity. He died after a long reign, and left the kingdom to his son, who was also called Phoor, and was the same with the famous Porus, who fought against Alexander.

The second Phoor, taking advantage of the disturbances in Persia, occasioned by the Greek invasion of that empire under Alexander, neglected to remit the customary tribute, which drew upon him the arms of that conqueror. The approach of Alexander did not intimidate Phoor. He, with a numerous army, met him at Sirhind, about one hundred and sixty miles to the north-west of Delhi, and in a furious battle, say the Indian historians, lost many thousands of his subjects, the victory, and his life. The most powerful prince of the Decan, who paid an unwilling homage to Phoor, or Porus, hearing of that monarch's overthrow, submitted himself to Alexander, and sent him rich presents by his son. Soon after, upon a mutiny arising in the Macedonian army, Alexander returned by the way of Persia.

Sinsarchund, the same whom the Greeks call Sandrocottus, assumed the imperial dignity after the death of Phoor, and in a short time regulated the discomposed concerns of the empire. He neglected not, in the mean time, to remit the customary tribute to the Grecian captains, who possessed Persia under, and after the death of, Alexander. Sinsarchund, and his son after him, possessed the empire of India seventy years. When the grandson of Sinsarchund acceded to the throne, a prince named Jona, who is said to have been a grand-nephew of Phoor, though that circumstance is not well attested, aspiring to the throne, rose in arms against the reigning prince, and deposed him.

-- The History of Hindostan, In Three Volumes, Volume I, by Alexander Dow, Esq., Lieutenant-Colonel in the Company's Service, 1812

It is, I believe, the Patali of Pliny. From a passage in this author compared with others from Ptolemy, Marcianus, Heracleota, and Arrian in his Periplus, we learn that the merchants, who carried on the trade from the Gangetic Gulph, or Bay of Bengal, to Perimula, or Malacca, and to Bengal, took their departure from some place of rendezvous in the neighbourhood of Point Godavery, near the mouth of the Ganga Godavery. The ships used in this navigation, of a larger construction than common, were called by the Greek and Arabian sailors, colandrophonta, or in the Hindustani dialect, coilan-di-pota, coilan boats or ships; for pota in Sanscrit, signifies a boat or a ship; and di or da, in the western parts of India, is either an adjective form, or the mark of the genitive case.

Pliny has preserved to us the track of the merchants who traded to Bengal from Point Godavery. They went to Cape Colinga, now Palmira; thence to Dandagula, now Tentu-gully, almost opposite to

Fultati* [This is the only place in this essay not to be found in Rennell's Atlas.]; thence to Tropina, or Triveni and Trebeni, called Tripina by the Portuguese, in the last century;

and, lastly, to Patale, called Patali, Patiali as late as the twelfth century, and now Patna. Pliny who mistook this Patale for another town of the same name, situate at the summit of the Delta of the Indus, where a form of Devi, under the appellation of Patali is equally worshipped to this day, candidly acknowledges, that he could by no means reconcile the various accounts he had seen about Patale, and the other places mentioned before.

The account transmitted to us of Chandra-Gupta [No, Sandrocottus!], by the historians of Alexander, agrees remarkably well with the abstract I have given in this paper of the Mudra Racshasa. By Athenaeus, he is called Sandracoptos, by the others Sandracottos, and sometimes Androcottos. He was also called Chandra simply; and, accordingly, Diodorus Siculus calls him Xandrames from Chandra, or Chandram in the accusative case; for in the western parts of India, the spoken dialects from the Sanscrit do always affect that case. According to Plutarch, in his life of Alexander, Chandra-Gupta had been in that prince’s camp, and had been heard to say afterwards, that Alexander would have found no difficulty in the conquest of Prachi, or the country of the Prasians had he attempted it, as the king was despised, and hated too, on account of his cruelty.

In the Mudra Racshasa it is said, that king Nanda, after a severe fit of illness, fell into a state of imbecility, which betrayed itself in his discourse and actions; and that his wicked minister, Sacatara, ruled with despotic sway in his name.

Diodorus Siculas and Curtius relate, that Chandram was of a low tribe, his father being a barber.

That he, and his father Nanda too, were of a low tribe, is declared in the Vishnu purana and in the Bhagavat Chandram, as well as his brothers, was called Maurya from his mother Mura; and as that word*

[See the Jutiviveca, where it is said, the offspring of a barber, begot by stealth, of a female of the Sudra tribe, is called Maurya: the offspring of a barber and a slave woman is called Maurya.] in Sanscrit signifies a barber, it furnished occasion to his enemies to asperse him as the spurious offspring of one.

The Greek historians say, the king of the Prasu was assassinated by his wife’s paramour, the mother of Chandra; and that the murderer got possession of the sovereign authority, under the specious title of regent and guardian to his mother’s children, but with a view to destroy them.

The puranas and other Hindu books, agree in the same facts, except as to the amours of Sacatara with Mura, the mother of Chandra-Gupta, on which head they are silent.

Nanda or Mahapadma Nanda... He had by one wife eight sons, who with their father were known as the nine Nandas; and, according to the popular tradition, he had by a wife of low extraction, called Mura, another son named Chandragupta. This last circumstance is not stated in the Puranas nor Vrihat Katha, and rests therefore on rather questionable authority...

It also appears from the play, that Chandragupta was a member of the same family as Nanda, although it is not there stated that he was Nanda’s son.

-- The Mudra Rakshasa, or The Signet of the Minister. A Drama, Translated from the Original Sanscrit, Select Specimens of the Theatre of the Hindus, Translated from Original Sanskrit, in Two Volumes, Vol. II, by Horace Hayman Wilson, 1835

Diodorus and Curtius are mistaken in saying, that Chandram reigned over the Prasu, at the time of Alexander's invasion: he was contemporary with Sileucus Nicator. Diodorus and Curtius are mistaken in saying, that Chandram reigned over the Prasu, at the time of Alexander's invasion: [as a king] he was contemporary with Sileucus Nicator.

I have inserted the words in brackets under a persuasion that Major Wilford intended to convey the idea supplied, and that only. He had already stated, after Plutarch, that Chandra-Gupta was in Alexander's camp, and therefore is not to be construed as here denying that he was contemporary with Alexander as a subject of Nanda. From the death of Alexander to the first transactions between Seleucus and Sandracottos, there intervened about twenty years.

-- On the Site of Palibothra: To the Editor of the Asiatic Journal(by Lieutenant-Colonel William Francklin, 1815?) (See Vol. v, p. 439)

I suspect Chandra-Gupta kept his faith with the Greeks or Yavans no better than he had done with his ally, the king of Nepal;

and this may be the motive for Seleucus crossing the Indus at the head of a numerous army; but finding Sandro-coptos prepared, he thought it expedient to conclude a treaty with him, by which he yielded up the conquest he had made; and, to cement the alliance,

gave him one of his daughters in marriage[???]* [Strabo, B. 45, p. 721.].

The geographical position of the tribes is as follows: along the Indus are the Paropamisadae, above whom lies the Paropamisus mountain: then, towards the south, the Arachoti: then next, towards the south, the Gedroseni, with the other tribes that occupy the seaboard; and the Indus lies, latitudinally, alongside all these places; and of

these places, in part, some that lie along the Indus are held by Indians, although they formerly belonged to the Persians. Alexander [III 'the Great' of Macedon] took these away from the Arians and established settlements of his own, but

Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus, upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange five hundred elephants. — Strabo 15.2.9

-- Seleucus I Nicator, by Wikipedia

Chandra-Gupta [No, Sandrocottus!] appears to have agreed on his part to furnish Seleucus annually with fifty elephants[???]; for

we read of Antiochus the Great going to India, to renew the alliance with king Sophagasemus, and of his receiving fifty elephants from him.

Sophagasemus, I conceive, to be a corruption of Shivaca-Sena, the grandson of Chandra-Gupta. In the puranas this grandson is called Asecavard-dhana or full of mercy, a word of nearly the same import as Aseca-sena or Shivaca-sena; the latter signifying he whose armies are merciful do not ravage and plunder the country.

The son of Chandra-Gupta [No, Sandrokottos!] is called Allitrochates [No, Bindusara!] and

Amitrocates by the Greek historian.

"Strabo (p. 70) says, 'Generally speaking, the men who have hitherto written on the affairs of India were a set of liars, — Deimachos holds the first place in the list, Megasthenes comes next; while Onesikritos and Nearchos, with others of the same class, manage to stammer out a few words (of truth). Of this we became the more convinced whilst writing the history of Alexander. No faith whatever can be placed in Deimachos and Megasthenes. They coined the fables concerning men with ears large enough to sleep in, men without any mouths, without noses, with only one eye, with spider legs, and with fingers bent backward. They renewed Homer's fables concerning the battles of the cranes and pygmies, and asserted the latter to be three spans high. They told of ants digging for gold, and Pans with wedge-shaped heads, of serpents swallowing down oxen and stags, horns and all, — meantime, as Eratosthenes has observed, accusing each other of falsehood. Both of these men were sent as ambassadors to Palimbothra, — Megasthenes to Sandrokottos, Deimachos to Amitrochados his son, — and such are the notes of their residence abroad, which I know not why, they thought fit to leave.-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle, M.A.

... called by Strabo Allitrochades, and by Athenaios (xiv. 67), Amitrochates, [The passage states that Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochos asking that king to buy and send him sweet wine, dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antioches replied: We shall send you the figs and the wine, but in Greece the laws forbid a sophist to be sold. Athenaios quotes Hegesander as his authority.]-- The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great as described by Arrian Q. Curtius Diodorus Plutarch and Justin: Being Translations of Such Portions of the Works of These and Other Classical Authors as Describe Alexander's Campaigns in Afghanistan the Panjab Sindh Gedrosia and Karmania With An Introduction Containing a Life of Alexander Copious Notes Illustrations Maps and Indices, by J.W. McCrindle M.A., Late Principal of the Government College Patna and Fellow of the Calcutta University Member of the General Council of the University of Edinburgh

In the course of determining the exact date of Buddha's death, Dr. Fleet [JRAS., 1909, p. 24.]

has adopted as the Sanskrit equivalent of Amitrochates or Amitrochades, the Greek version of the name or title by which they knew Candragupta's [Sandrocottus's !!!] son, Amitrakhada, rather than the conventional Amitraghata, [For the variants of the name, cf. Vincent Smith, Early History of India, 2, p. 138; the identification with Amitraghata was made by Lassen. See also Franke, Pali und Sanskrit, p. 71.]

on the ground that this word has not yet been established as a personal name by any Indian or Ceylonese books or inscriptions, while Amitrakhada is found as an epithet of Indra.-- "Amitrochates," Excerpt from Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 41, Issue 2, pp. 423-426, April 1909

The name "Bindusara", with slight variations, is attested by the Buddhist texts such as Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa ("Bindusaro"); the Jain texts such as Parishishta-Parvan; as well as the Hindu texts such as Vishnu Purana ("Vindusara"). Other Puranas give different names for Chandragupta's successor; these appear to be clerical errors. For example, the various recensions of Bhagavata Purana mention him as Varisara or Varikara. The different versions of Vayu Purana call him Bhadrasara or Nandasara.The Mahabhashya...The Mahābhāṣya, "great commentary"), attributed to

Patañjali, is a commentary on selected rules of Sanskrit grammar from Pāṇini's treatise, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, as well as Kātyāyana's Vārttika-sūtra, an elaboration of Pāṇini's grammar....The dating of Patanjali and his Mahabhasya is established by...evidence...from the Maurya Empire period, the historical events mentioned in the examples he used to explain his ideas.

-- Patanjali, by Wikipedia

names Chandragupta's successor as Amitra-ghata (Sanskrit for "slayer of enemies"). The Greek writers Strabo and Athenaeus call him Allitrochades and Amitrochates respectively; these names are probably derived from the Sanskrit title. In addition, Bindusara was given the title Devanampriya ("The Beloved of the Gods"), which was also applied to his successor Ashoka. The Jain work Rajavali-Katha states that his birth name was Simhasena.

-- Bindusara, by Wikipedia

Strabo refers to Deimachus being sent by Antiochus I as his ambassador to Amitrochates the son of Sandrocottus. Pliny speaks of another envoy who was sent by the king of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus (185-247 B.C.). [Hist. Nat., Book IV, c. 17, (21).]

-- Asoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, by Romila Thapar

Seleucus sent an ambassador to him; and after his death the same good intelligence was maintained by Antiochus the son or the grandson of Seleucus.

This son of Chandra-Gupta is called Varisara in the puranas; according to Parasara, his name was Dasaratha; but neither the one nor the other bear any affinity to Amitrocates: this name appears, however, to be derived from the Sanscrit Mitra-Gupta, which signifies saved by Mitra or the Sun, and therefore probably was only a surname. It may be objected to the foregoing account, the improbability of a Hindu marrying the daughter of a Yavana, or, indeed, of any foreigner. On this difficulty I consulted the Pundits of Benares, and they all gave me the same answer; namely, that in the time of Chandra-Gupta the Yavanas were much respected, and were even considered as a sort of Hindus though they afterwards brought upon themselves the hatred of that nation by their cruelty, avarice, rapacity, and treachery in every transaction while they ruled over the western parts of India; but that

at any rate the objection did not apply to the case, as Chandra-Gupta himself was a Sudra, that is to say, of the lowest class.[!!!] In the Vishnu-Purana, and in the Bhagawat, it is recorded, that eight Grecian kings reigned over part of India. They are better known to us by the title of

the Grecian kings of Bactriana. Arrian in his Periplus, enumerating the exports from Europe to India, sets down as one article beautiful virgins, who were generally sent to the market of Baroche. The Hindus acknowledged that, formerly, they were not so strict as they are at this day; and this appears from their books to have been the case.

Strabo does not positively say that Chandra-Gupta married a daughter of Seleucus, but that Seleucus cemented the alliance he had made with him by connubial affinity, from which expression it might equally be inferred that Seleucus married a daughter of Chandra-Gupta[!!!]; but this is not so likely as the other[!!!]; and it is probable the daughter of Seleucus was an illegitimate child, born in Persia after Alexander's conquest of that country.[???!!!]Before I conclude, it is incumbent on me to account for the extraordinary difference between the line of the Surya Varsas or children of the sun, from Ichswacu to Dasaratha-Rama, as exhibited in

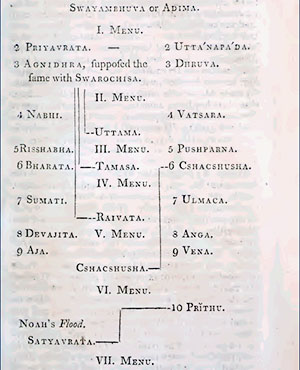

the second volume of the Asiatick Researches, from the Vishnu-purana and the Bhagawat, and that set down in the Table I have given with this Essay.

The line of the Surya Varsas, from the Bhagawat being absolutely irreconcileable with the ancestry of Arjuna and Chrishna, I had at first rejected it, but, after a long search, I found it in the Ramayen, such as I have represented it in the table, where it perfectly agrees with the other genealogies.[???] Dasaratha-Rama was contemporary with Parasu-Rama, who was, however the eldest; and

as the Ramayen is the history of Dasaratha-Rama, we may reasonably suppose, his ancestry was carefully set down and not wantonly abridged. According to R.P. Tripathi, professor of ancient history at Allahabad University, "History requires concrete evidence in the form of coins, inscriptions, etc. to prove the existence of a character. Even if we take into account places mentioned in the Ramayana like Chitrakoot, Ayodhya, which still exist, the fact is that Ramayana is not a historical text."...

"In Ramayana's case, there is no evidence to prove that it is anything else except a myth. There is also no evidence -- either historical or archaeological -- which proves that Ram ever existed or that he ruled Ayodhya" claims S. Settar [former chairman of the Indian Council of Historical Research.

-- For Historians, Ram Remains a Myth, by Atul Sethi, Times of India, 9/14/07

Dasharatha was the king of Kosala kingdom and the descendent of Ikshavaku Dynasty and

father of the Lord Rama. His capital was Ayodhya. Dasharatha was the son of Aja and Indumati. He had three main throne queens: Kausalya, Kaikeyi and Sumitra, and from these unions were born Rama, Bharata, Lakshmana and Shatrughna. He is mentioned [in the]

Ramayana and Vishnu Purana.

King Dasharatha was an incarnation of Svayambhuva Manu, the son of the Hindu creator god, Brahma.Dasharatha was the son of King Aja of Kosala and Indumati of Vidarbha. His birth name was Nemi, but

he acquired the name Dasharatha as his chariot could move in all ten directions, fly, as well as come down to earth, and he could fight with ease in all of these directions.-- Dasharatha, by Wikipedia

I shall now conclude this Essay with the following remarks:

Parashara was a maharshi and the author of many ancient Indian texts. He is accredited as the author of the first Purana, the Vishnu Purana, before his son

Vyasa wrote it in its present form.

He was the grandson of Vasishtha, the son of Śakti Maharṣi....

When Parashara's father, Sakti Maharishi died after being devoured by the king Kalmashapada [In Hindu mythology,

Kalmashapada, also known as Saudasa, Mitrasaha, Amitrasaha and Kalmashanghri (Kalmasanghri), was a king of the Ikshvaku dynasty (the Solar dynasty), who

was cursed to be a rakshasa (demon) by the sage Vashishtha. He is described as an ancestor of Rama, the avatar of the god Vishnu and the hero of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Many texts narrate how Kalmashapada was cursed to die if he had intercourse with his queen, so he obtained a son from Vashishtha by niyoga, an ancient tradition whereby a husband can nominate another man to impregnate his wife.] along with Vashistha's other sons,

Vashistha resorted to ending his life by suicide. Hence he

jumped from Mount Meru but landed on soft cotton, he

entered a forest fire only to remain unharmed, then he jumped into the ocean who saved him by casting him ashore. Then he

jumped in the overflowing river Vipasa, which also left him ashore. Then he

jumped into the river Haimavat, which fled in several directions from his fear and was named Satadru. Then when he returned to his asylum,

he saw his daughter-in-law pregnant. When a son was born he acted as his father and hence forgot completely about destroying his life. Hence, the child was named Parashara which meant enlivener of the dead.

According to the Vedas, Brahma created Vasishtha, who, with his wife Arundhati, had a son named Śakti Mahariṣhi who sired Parashara. With Satyavati, Parashara is father of

Vyasa. Vyāsa sired Dhritarashtra and Pandu through his deceased step brother's wives, Ambika and Ambalika and Vidura through a hand-maiden of Ambika and Ambalika. Vyāsa also sired Shuka through his wife, Jābāli's daughter Pinjalā.

Thus Parashara was the biological great-grandfather of both the warring parties of the Mahābhārata, the Kauravas and the Pandavas. Parashara is used as a gotra [lineage] for the ancestors and their offsprings thereon.

-- Parashara, by Wikipedia

I. It has been asserted in the second volume of the Asiatick Researches, that Parasara lived about 1180 years before Christ[???], in consequence of an observation of the places of the colures [either of two great circles intersecting at right angles at the celestial poles and passing through the ecliptic at either the equinoxes or the solstices.].

We come now to the commentary, which contains information of the greatest importance. By former Sastras are meant, says Battotpala [Utpala], the books of Parasara and of other Munis; and he then cites from the Parasari Sanhita the following passage, which is in modulated prose, and in a style much resembling that of the Vedas:

"The season of Sisira is from the first of Dhanishtha to the middle of Revati; that of Vasanta from the middle of Revati to the end of Rohini; that of Grishma from the beginning of Mrigasiras to the middle of Aslesha; that of Versha from the middle of Aslesha to the end of Hasta; that of Sanad from the first of Chitra to the middle of Jyeshtha; that of Hemanta from the middle of Jyeshtha to the end of Sravana."

This account of the six Indian seasons, each of which is co-extensive with two signs, or four lunar stations and a half, places the solstitial points, as Varaha has asserted, in the first degree of Dhanishtha, and the middle, or 6°40', of Aslesha, while the equinoctial points were in the tenth degree of Bharani and 3°20' of Visacha; but in the time of Varaha, the solstitial colure passed through the 10th degree of Punarvasu and 3°20' of Uttarashara, while the equinoctial colure cut the Hindu ecliptic in the first of Aswini and 6°40' of Chitra, or the Yoga and only star of that mansion, which, by the way, is indubitably the Spike of the Virgin, from the known longitude of which all other points in the Indian Zodiac may be computed. It cannot escape notice, that Parasara does not use in this passage the phrase at present, which occurs in the text of Varaha; so that the places of the colures might have been ascertained before his time, and a considerable change might have happened in their true position without any change in the phrases by which the seasons were distinguished; as our popular language in astronomy remains unaltered, though the Zodiacal asterisms are now removed a whole sign from the places where they have left their names. It is manifest, nevertheless, that Parasara must have written within twelve centuries before the beginning of our era, and that single fact, as we shall presently show, leads to very momentous consequences in regard to the system of Indian history and literature.

-- XXVII. A Supplement to the Essay on Indian Chronology, by the President (Sir William Jones), Asiatic Researches, Volume 2, 1788

But Mr. Davis having considered this subject with the minutest attention, authorizes me to say, that this observation must have been made 1391 years before the Christian aera. This is also confirmed by a passage from the Parasara Sanhita in which it is declared, that the Udaya or heliacal rising of campus, (when at the distance of thirteen degrees from the sun, according to the Hindu astronomers,) happened in the time of Parasara, on the 10th of Cartica; the difference now amounts to twenty-three days.

Having communicated this passage to Mr. Davis, he informed me, that it coincided with the observation of the places of the colures in the time of Parasara.

Another synchronism still more interesting, is that of the flood of Deucalion which, according to the best chronologers, happened 1390 years before Christ.[!!!] Deucalion is derived from Deo-Calyun or Deo Caljun: the true Sanscrit name is Deva-Cala-Yavana. The word Cala-Yavana is always pronounced in conversation, and in the vulgar dialects Ca-lyun or Calijun: literally, it signifies the devouring Yavana. He is represented in the puranas, as a most powerful prince, who lived in the western parts of India, and generally resided in the country of Camboja, now Gazni, the ancient name of which, is Safin or Safna. It is true, they never bestow upon him the title of Deva; on the contrary,

they call him an incarnate demon: because he presumed to oppose Crishna; and was very near defeating his ambitious projects; indeed Crishna was nearly overcome and subdued, after seventeen bloody battles; and, according to the express words of the puranas, he was forced to have recourse to treachery; by which means Calyun was totally defeated in the eighteenth engagement. That his followers and descendants should bestow on him the title of Deva, or Deo, is very probable; and the numerous tribes of Hindus, who, to this day, call Chrishna, an impious wretch, a merciless tyrant, an implacable and most rancorous enemy. In short, these Hindus, who consider Crishna as an incarnate demon, now expiating his crimes in the fiery dungeons of the lowest hell, consider Calyun in a very different light, and, certainly, would have no objection to his being called Deo-Calyun.

Be it as it may, Deucalion was considered as a Deva or Deity in the west, and had altars erected to his honour.

The Greek mythologists are not agreed about him, nor the country, in which the flood, that goes by his name, happened: some make him a Syrian; others say, that his flood happened in the countries, either round mount Etna, or mount Athos; the common opinion is, that it happened in the country adjacent to Parnasus; whilst

others seem to intimate, that he was a native of India, when they assert that he was the son of Prometheus, who lived near Cabul, and whose cave was visited by Alexander, and his Macedonians. It is called in the puranas Garnda-sihan, or the place of the Eagle, and is situated near the place called Shibi, in Major Rennell's map of the western parts of India; indeed, Pramathasi[???] is better known in Sudia by the appellation of Sheba* [Bamian (in Sanscrit Vamiyan) and Shibr lay to the N.S. of Cabul.].

Deo-Calyun, who lived at Gazni, was obliged on the arrival of Chrishna, to fly to the adjacent mountains, according to the puranas; and the name of these mountains was formerly Parnasa, from which the Greeks made Parnasus; they are situated between Gazni and Peshower. Crishna, after the defeat of Calyun, desolated his country with fire and sword. This is called in Sanscrit Pralaya; and may be effected by water, fire, famine, pestilence, and war:

but in the vulgar dialects, the word Pralaya, signifies only a flood or inundation. The legends relating to Deo-Calyun, Prometheus and his cave, will appear in the next dissertation I shall have the honour to lay before the Society.

In Greek mythology, Deucalion was the son of Prometheus...

The flood in the time of Deucalion was caused by the anger of Zeus, ignited by the hubris of Lycaon and his sons, descendants of Pelasgus. According to this story,

Lycaon, the king of Arcadia, had sacrificed a boy to Zeus, who, appalled by this offering, decided to put an end to the Bronze Age by unleashing a deluge. During this deluge, the rivers ran in torrents and the sea flooded the coastal plain, engulfing the foothills with spray, and washing everything clean.

Deucalion, with the aid of his father Prometheus, was saved from this deluge by building a chest. Like the biblical Noah and the Mesopotamian counterpart Utnapishtim, he uses this device to survive the deluge with his wife, Pyrrha.The fullest accounts are provided in

Ovid's Metamorphoses (late 1 BCE to early 1 CE) and in the Library of Pseudo-Apollodorus.

Deucalion, who reigned over the region of Phthia, had been forewarned of the flood by his father, Prometheus. Deucalion was to build a chest and provision it carefully (no animals are rescued in this version of the flood myth), so that when the waters receded after nine days, he and his wife Pyrrha, daughter of Epimetheus, were the one surviving pair of humans. Their chest touched solid ground on Mount Parnassus or Mount Etna in Sicily, or Mount Athos in Chalkidiki, or Mount Othrys in Thessaly.-- Deucalion, by Wikipedia

II. Megasthenes was a native of Persia, and enjoyed the confidence of Sibyrtius* [Arrian, B. 5., p. 203.], governor of Arachosia, (now the country of Candahar and Gazni,) on the part of Seleucus. Sibyrtius sent him frequently on the embassies to Sandrocuptos. When Seleucus invaded India, Megasthenes enjoyed also the confidence of that monarch, who sent him, in the character of ambassador, to the court of the king of Prachi.

We may safely conclude, that Megasthenes was a man of no ordinary abilities, and as he spent the greatest part of his life in India, either at Candahar or in the more interior parts of it; and,

as from his public character, he must have been daily conversing with the most distinguished persons in India,

I conceive, that if the Hindus, of that day, had laid claim to so high an antiquity, as those of the present,

he certainly would have been acquainted with their pretensions, as well as with those of the Egyptians and Chaldaeans; but, on the contrary,

he was astonished to find a singular conformity between the Hebrews and them in the notions about the beginning of things, that is to say, of ancient history.[???] At the same time,

I believe, that the Hindus, at that early period, and, perhaps, long before, had contrived various astronomical periods and cycles, though they had not then thought of framing a civil history, adapted to them.

Astrology may have led them to suppose so important and momentous an event as the creation must have been connected with particular conjunctions of the heavenly bodies; nor have the learned in Europe been entirely free from such notions.

Again, in the context of the war, it is natural for writers, especially of epics, to describe portents as happening to presage evil. The Samhitas devote chapters to describe these portents. The Ketucara, on the appearance of comets, is full of portents, as also separate chapters devoted to portents like rare or unnatural, impossible or terrible phenomena. These have been included in the work.11 [See, e.g., Udyoga, 143; Bhisma, 2, 3; Karna, 94, 100; S'alya, 11, 27; Mausala, 2.] But most investigators have not interpreted these portions properly, for which a detailed study of the chapters on Ketucara and Utpatas in the Brhatsamhita of Varahamihira would be advantageous. For example,

the mention of the new moon together with solar eclipse occurring on Trayodasi, the sun and the moon being eclipsed on the same day (the same month), and that on Trayodasi, Mercury moving across the sky, (i.e., north-south), the dark patch on the moon being inverted, the lunar eclipse at Karttika full moon, the solar eclipse at Karttika new moon, and again the solar eclipse at the time of the mace-fight, are all intended by the writer to be impossible things occurring. The mention of the red moon indistinguishable from the red sky (digdaha), eagles falling on the flag, appearances of comets of different colours and in groups are all portents. Ignorance of the fact that the ‘grahas’ of different colours mentioned in Bhismaparva, chapter 3, are not planets but comets, has added to the confusion, because these scholars do not realise that, in the Samhitas, the word ‘graha’ means primarily comets, (vide the chapter on Ketucara in the Brhatsamhita).

It would be clear from the above, that all the skill shown in distorting the meanings of words and trying to show when these impossible or rare phenomena and contradictory planetary combinations would actually occur, has been wasted. Excepting the time of the year when the war might have happened, there is nothing in the Mahabharata to fix the year definitely. We do not have adequate data to fix either the happenings or when the work, even part by part, was written.-- Determination of the Date of the Mahabharata: The Possibility Thereof, [Reprinted from Vishveshvaramand Indological Journal, Vol. XIV (1976) pp. 48-56.], Excerpt, from Collected Papers on Jyotisha, by T.S. Kuppanna Sastry

Having once laid down this position, they did not know where to stop; but the whole was conducted in a most clumsy manner, and their new chronology abounds with the most gross absurdities; of this, they themselves are conscious, for, though willing to give me general ideas of their chronology, they absolutely forsook me, when they perceived my drift in a stricter investigation of the subject.

The loss of Megathenes' works is much to be lamented. From the few scattered fragments, preserved by the ancients, we learn that the history of the Hindus did not go back above 5042 years. The MSS. differ; in some we read 6042 years; in others 5042 and three months, to the invasion of India by Alexander. Megasthenes certainly made very particular enquiries, since he noticed even the months. Which is the true reading, I cannot pretend to determine; however,

I [am] inclined [to] believe, it is 5042, because it agrees best with the number of years assigned by Albumazar, as cited by Mr. Bailly, from the creation to the flood. This famous astronomer, whom I mentioned before, had derived his ideas about the time of the creation and of the flood, from the learned Hindus he had consulted; and

He assigns 2226 years, between what the Hindus call the last renovation of the world, and the flood. This account from Megasthenes and Albumazar, agrees remarkably well with the computation of the Septuagint [The Greek Old Testament is the earliest extant Koine Greek translation of books from the Hebrew Bible and deuterocanonical books.]. I have adopted that of the Samaritan Pentateuch, as more conformable to such particulars as I have found in the puranas; I must confess, however, that some particular circumstances, if admitted, seem to agree best with the computations of the Septuagint:

besides, it is very probable, that the Hindus, as well as ourselves,

had various computations of the times we are speaking of.Megasthenes informs us also, that the Hindus had a list of kings, from Dionysius to Sandrocuptos, to the number of 153. Perhaps, this is not to be understood of successions in a direct line; if so, it agrees well enough with the present list of the descendants of Nausha, or Deo-Naush.

This is what they call the genealogies simply, or the great genealogy, and which they consider as the basis of their history. They reckon these successions in this manner: from Nausha to Crishna, and collaterally from Naush to Paricshita; and afterwards from Jarasandha, who was contemporary with Crishna. Accordingly the number of kings amounts to more than 153; but, as I wanted to give the full extent of the Hindu chronology,

I have introduced eight or nine kings, which, in the opinion of several learned men, should be omitted, particularly six, among the ancestry of Crishna.

Megasthenes, according to Pliny and Arrian, seems to say, that 5042 years are to be reckoned between Dionysius, or Deo-Nausha, and Alexander, and that 153 kings reigned during that period;

but, I believe, it is a mistake of Pliny and Arrian; for 153 reigns, or even generations, could never give so many years.

Megasthenes reckons also fifteen generations between and Dionysius and Hercules,

by whom we are to understand, Chrisna and his brother Bala-Rama.

To render this intelligible, we must consider Naush in two different points of view: Naush was at first a mere mortal, but on mount Meru he became a Deva or God, hence called Deva-Naush or Deo-Naush, in the vulgar dialects. This happened about fifteen generations before Crishna. It appears that like the spiritual rulers of Tartary and Tibet (which countries include the holy mountains of Meru). Deo-Naush did not, properly speaking, die, but his soul shifted its habitation, and got into a new body whenever the old one was worn out, either through age or sickness. The names of three of the successors of Nausha have been preserved by Arrian; they are Spartembas, Budyas, and Cradevas. The first seems derived from the Sanscrit Prachinvau, generally pronounced Prachinbau, from which the Greeks made Spartembau in the accusative case; the two others are undoubted Sanscrit, though much distorted, but I suspect them to be titles, rather than proper names.

III.

This would be a proper place to mention the posterity of Noah or Satyavrata, under the names of Sharma or Shana (for both are used,) Charma and Jyapti. They are mentioned in five or six puranas, but no farther particulars concerning them are related, besides which is found in a former essay on Egypt. In the list of the thousand names of Vishnu, a sort of Litany, which Brahmens are obliged to repeat on certain days, Vishnu is called Sharma, because, according to the learned, Sharma or Shama, was an incarnation if that deity. In a list of the thousand names of Siva, as extracted from the Padma-purana, the 371st name is Shama-Jaya, which is in the fourth case, answering to our dative, the word praise being understood: Praise to Sharmaja, or to him who was incarnated in the house of Sharma.

The 998th name is Sharma-putradaya, in the fourth case also, praise to him who gave offspring to Sharma.

My learned friends here inform me, that it is declared in some of the puranas, that Sharma, having no children, applied to Siva, and made Tapasya, to his honour. Iswara was so pleased, that he granted his request and condescended to be incarnated in the womb of Sharma's wife, and was born a son of Sharma, under the name of Baleswara, or Iswara the infant.

Baleswara, or simply Iswara, we mentioned in a former essay on Semiramis; and he is obviously the Assur of Scripture.

In another list of the thousand names of Siva (for there are five or six of them extracted from so many puranas) we read, as one of his names, Balesa Isa or Iswara the infant. In the same list Siva is said to be Varahi-Palaca, or he who fostered and cherished Varahi, the consort of Vishnu, who was incarnated in the character of Sharma.

From the above passages the learned here believe that Siva, in a human shape, was legally appointed to raise seed to Sharma during an illness thought incurable. In this sense Japhet certainly dwelt in the tents of Shem. My chief pandit has repeatedly, and most positively, assured me, that the posterity of Sharma to the tenth or twelfth generation, is mentioned in some of the puranas. His search after it has hitherto proved fruitless, but it is true, that we have been able to procure only a few sections of some of the more scarce and valuable puranas. The field is immense, and the powers of a single individual too limited. V. The ancient statues of the gods having been destroyed by the Mussulmans, except a few which were concealed during the various persecutions of these unmerciful zealots, others have been erected occasionally, but they are generally represented in a modern dress. The statue of Bala-Rama at Mutra has very little resemblance to the Theban Hercules, and, of course, does not answer exactly to

the description of Megasthenes[??????]. There is, however,

a very ancient statue of Bala-Rama at a place called Baladeva, or Baldeo in the vulgar dialects, which answers minutely to his description. It was visited some years ago by the late Lieutenant Stewart, and I shall describe it in his own words: "Bala-Rama or Bala-deva is represented there with a ploughshare in his left hand with which he hooked his enemies, and in his right hand a thick cudgel, with which he cleft their sculls; his shoulders are covered with the skin of a tyger. The village of Baldeo is thirteen miles E. by S. from Muttra.”

Here I shall observe, that the ploughshare is always represented very small [and] sometimes omitted; and that it looks exactly like a harpoon, with a strong hook, or a gaff, as it is usually called by fishermen[???]. My pandits inform me also, that Bala-Rama is sometimes represented with his shoulders covered with the skin of a lion.