Google Translate of Italian Original

The Bronze Laminetta Of Drusus Minor Preserved At The Provincial Museum Of Torcello: A False Unmasked (* [In addition to the numerous people thanked in the individual footnotes, I am grateful to my colleagues Alfredo Buonopane, Giovannella Cresci and Franco Luciani for reading the final drafting of this contribution and helping me with their advice.])

by Lorenzo Calvelli

Epigraphic

LXXVII, 1-2, p. 133

2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Abstract

This article examines in detail a small bronze tablet belonging to the collection of the Museo Provinciale di Torcello, near Venice. The tablet is inscribed on both sides and bears a dedication to Drusus the Younger, emperor Tiberius’ son who died in AD 23, plus some abbreviations that are difficult to expand. The object has long been considered to be genuine, however in more recent times its authenticity has been questioned. Internal analysis, which reveals some anomalous characteristics, supports these doubts, but the most convincing arguments are offered by comparison with other artefacts. In fact, previous editors failed to remark that several objects bearing the same text had already been registered and considered false by the curators of the Corpus inscriptionum Latinarum. A vast survey conducted through a network of European museums demonstrates that nearly identical tablets are kept today in Arezzo, Madrid and Basel. It is likely that these counterfeit antiquities, whose inscribed words and letters reproduce with slight variations the texts that were readable on authentic inscriptions and coins, were actually created in Tuscany in the mid 18th century.

Key words: bronze inscriptions; epigraphic forgeries; Drusus the Younger; Museo Provinciale di Torcello; Museo Archeologico Nazionale Gaio Cilnio Mecenate di Arezzo; Museo Arqueológico Nacional de Madrid; Antikenmuseum Basel; Accademia Colombaria.

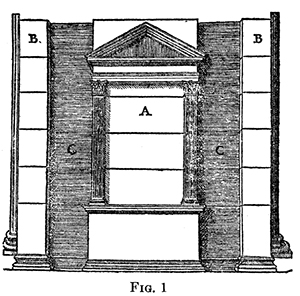

1. The laminetta of Torcello

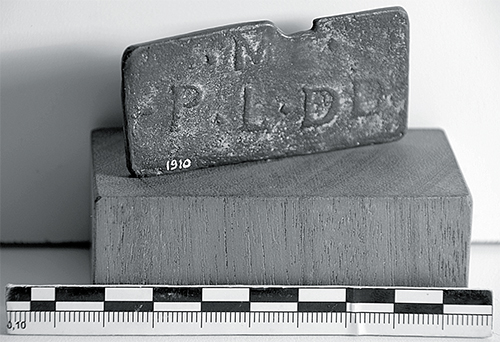

In the archaeological collection of the Provincial Museum of Torcello there is a rectangular opistograph bronze sheet which has repeatedly attracted the attention of scholars (Figs. 1-2) (1). Its first mention is due to Luigi Conton, director of the museum collection in the early decades of the twentieth century: in an article published in 1909, the scholar presented a detailed analysis of the find, reporting that it had been found "recently near Torcello " (2); in another contemporary publication he specified: "This bronze plate was found a short distance from the cathedral at a depth of one meter, in the year 1908" (3).

Fig. 1. TORCELLO (VE), Provincial Archaeological Museum, inv. 1910a-b, recto (Photo: Province of Venice).

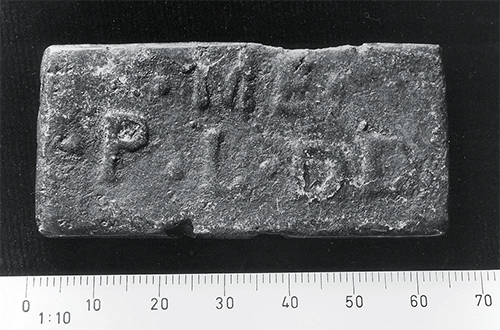

Fig. 2. TORCELLO (VE), Provincial Archaeological Museum, inv. 1910a-b, verso (Photo: Province of Venice).

The exhibit measures 2.9 × 6.5 × 0.3 cm, weighs 44.5 grams and is currently exhibited in a showcase on the upper floor of the ancient Palazzo dell'Archivio, together with other metal artifacts, mostly dating back to the Roman times. The edges of the object are intact and slightly rounded on the corners; in the central part of the upper margin there is a conspicuous trapezoidal chipping. The two faces of the blade are engraved with an inscription in relief, obtained by casting (and not typing) from a negative bivalve matrix. The text follows an approximate alignment and is spread over four lines in the recto and two lines in the back (4). The letters have a variable height that varies between 0.6 and 0.4 cm on the front and 1.3 and 1 cm on the reverse. The transcription proposed following an autopsy check (September 2014) is the following:

Drusus Caisari,

Aug(usti) to you, god

Aug(usti) n(epoti),

s(aged) c(raised).//

I(- - -)

p(- - -) l(- - -) d(- - -) d(- - -).

From Drusus Caesar, son of Tiberius Augustus, nephew of the divine Augustus, by decree of the senate. -).

Both sides of the inscription adopt a centered and symmetrically well-set layout. In the text there are several circular punctuation marks, arranged at variable heights, often out of height and at the foot of the letter, both between the individual words, as well as at the beginning and at the end of some lines. The groove of the letters is on the whole well marked. From the palaeographical point of view, the G with a very pronounced pillar can be seen in the rr. 2 and 3 of the recto and the P with open eyelet at the beginning of the r. 2 of the reverse. The autopsy of the artifact, carried out with the aid of grazing light and binocular glasses, made it possible to identify between the two terms of r 1 of the front a punctuation mark, placed just above the ideal guideline on which the inscription runs; it is followed by the remains of a semicircular letter with the curve turned to the left, identifiable with the lower half of a C: this has led to a preference for the CAISARI reading instead of KAISARI, for which all the previous publishers had opted instead.

The content analysis of the document, conducted by Ezio Buchi in a short essay published in 1994, identified without hesitation in the text engraved on the front of the flap a dedication to Drusus Caesar, also known as Drusus Minor, son of Tiberius and Vipsania Agrippina, born between 15 and 12 BC and died in 23 A.D., perhaps poisoned by his wife Livilla in complicity with the praetorian prefect Seiano (5). According to the Tacitian testimony, on the occasion of the untimely death of his son, the emperor bestowed even greater honors on him than those decreed four years earlier to the designated Germanic heir (6). As for the two lines on the reverse of the artefact, they are characterized by a sequence of abbreviated terms that are difficult to dissolve. The only exegetical proposals so far advanced are devoid of reliable comparisons and little or not at all convincing (7).

A careful autopsy examination of the find, however, raises serious doubts as to its authenticity. By resorting to diplomatic terminology, it can be observed in particular that among the intrinsic characters the punctuation marks placed at the beginning or at the end of a line and at variable height are unusual in Latin epigraphs on bronze of the high-imperial era (8 ), as well as the sequences of litterae singulares [GT: individual letters ] present on the reverse of the artefact. As regards extrinsic characters, the peculiarity of the support on which the text of the inscription is engraved stands out above all (9). Specifically, it does not find comparisons with other well-known categories of the so-called instrumentum inscriptum [GT: written instrument]: in fact it is neither a tabula lusoria [game board], nor a hospitalis [hospitality token] or nummularia card [a bronze tag for money changers], nor a label to affix (as an opisthographer) or from hang (as it has no hole or ring socket). The possible use of this type of artefact therefore remains to be explained. Finally, it should be noted that the dimensions of the find are in no way comparable to ancient units of measurement.

Some of the considerations set out here were already advanced a few years ago by Antonio Sartori, who was the first to suggest the possibility that the bronze plate was actually a fake of the modern era (10). The hypothesis expressed by the scholar followed the appearance on the Parisian antiques market of three small bronze opisthograph finds, similar in type to the one preserved in Torcello, on one of which a substantially identical text was engraved (11). The other two small plates also had inscriptions of dubious authenticity, one of which reproduced with gross errors the text of a genuine epigraph (12), containing a dedication to Germanicus and two of his sons, engraved on a marble slab of non-urban origin, but already attested in Rome in the sixteenth century (13).

2. The flails of the pigeons

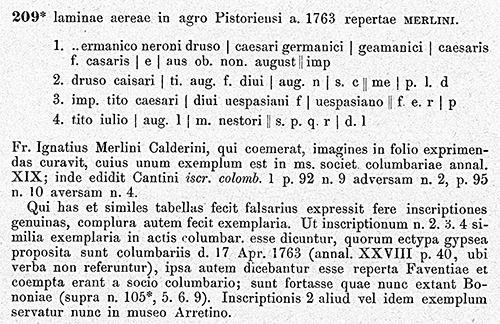

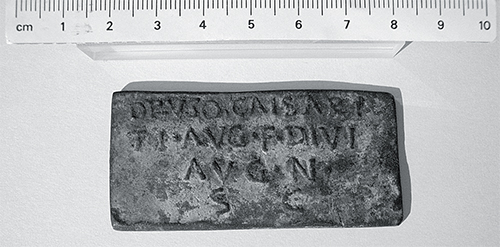

A new bibliographic investigation has now been the starting point for a further advancement of the research. The first tome of the eleventh volume of the Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum [GT: A body of Latin inscriptions], published in 1888, in fact contains an entry dedicated to a group of four epigraphs engraved on bronze objects, which Eugen Bormann, curator of this section of the CIL, relegated without hesitation to the category of falsae (Fig. 3) (14). Among these artifacts, defined as "laminae aeriale in agro Pistoriensi a. 1763 repertae" [GT: aerial plates in the field of Pistorius a. 1763 found](15), first of all shows an example of the dedication to Germanicus and his sons mentioned earlier, perhaps the very same one that has recently reappeared on the Paris antiques market (16). However, it is the second of the epigraphic documents transcribed to us by Bormann that most draws our attention (17):

Drusus Caisari,

Aug(usti) to you, god

Aug(usti) n(epoti),

s(aged) c(raised).//

I(- - -)

p(- - -) l(- - -) d(- - -).

209* brass plates in the Pistorian field a. 1763 discovered by Merlin.

1. ..germanico neroni druso / caesar germanici / gemamanici / caesaris f. casaris / e / aus ob. no august // imp

2. Drusus caisari / ti Aug. f. long / Aug. n / s.c. // me / p. l. d

3. imp. titus caesari / diui vespasian f / vespasiano // f. e. r / p

4. Titus July / Aug. / m. nestor // s. p. Q. r / d. l

Fr. Ignatius Merlini Calderini, who had bought it, took care to print the images on the folio, one example of which is in ms. associates annals of pigeons 19; from there he published Cantini's inscr. dove 1 p. 92 n. 9 contrary to n. 2, p. 95 n. 10 reversed n. 4.

He who made these and similar letters has forged almost all the genuine inscriptions, but he has made several copies. As the number of addresses 2. 3. 4 similar patterns in the records of the dove. they are said to be, whose plaster casts were proposed for colonnades d. 17 April 1763 (annal. 28 p. 40, where the words are not mentioned), but they were said to have been found in Favente and had been bought by a dovecote associate; they are perhaps those which now exist in Bononia (above n. 105*, 5. 6. 9). Another or the same copy of inscription 2 is now preserved in the museum of Arretino.

Fig. 3. CIL XI, 209*.

Already at first sight it can be seen that the text is substantially identical to that which can be read on the bronze sheet preserved in the Provincial Museum of Torcello. The only significant difference is the presence of only one D in the final line of the reverse of the epigraphic document transcribed by Bormann. The object on which this inscription was engraved, as well as the other three reviewed in the same CIL entry, belonged in the eighteenth century to Abbot Francesco Ignazio Merlini Calderini, a Pistoian scholar and member of the Columbian Academy of Florence (18).

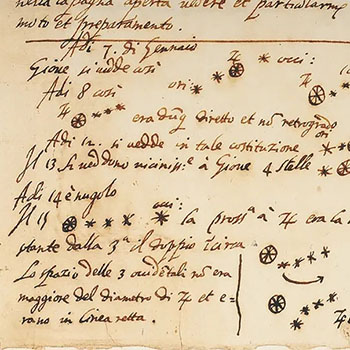

As can be seen from the bibliographic indications cited in the apparatus, Bormann had learned this news by consulting the manuscript Annals of the Florentine cultural institution (19). The original of the document consulted by the scholar is transcribed in full below, who fortunately escaped the destruction that the ancient headquarters of the Academy suffered during the Second World War (20):

On September 11 [1763]. Gather to the usual lair. Verecondo brought a printed copy of some inscriptions that can be read in relief on four copper sheets, recently found in the Pistoia area and purchased by Francesco Ignazio Merlini Calderini, our foreign partner. It has been observed that the last three laminae are quite similar to three others of those that our Wanderer communicated to us, as in the year preceding f. 40 (21).

The text summarizes the topics addressed by the members of Colombaria during a session held on Sunday 11 September 1763. On this occasion, the Florentine patrician scholar Giuseppe Pelli Bencivenni, known with the academic name of "Verecondo" (22), had provided others present a printed reproduction of some bronze artefacts purchased from their Pistoian partner Merlini Calderini. Unfortunately, this graphic documentation, initially attached to the Annual and viewed by Bormann, is no longer available today (23).

During the meeting in question, the Pigeons remarked on the close affinities that existed between three of the small plates owned by Merlini Calderini and other similar finds, mentioned in a passage from the previous volume of the Annals, which is transcribed below:

On April 17, 1763. Gathered at the usual den etc. Six plaster tablets were donated to our Society, which are placed in a small picture, with very ancient Roman inscriptions. They were formed on the bronze tablets, purchased by the Vagante, who came from Faenza, where they were found underground by a worker in making some pits on his farm (24).

From the document it is clear that another columbarium partner, Giovanni Baldovinetti known as the "Vagante" (25), was in possession of six bronze plates, which a marginal annotation places in relation to those subsequently reported by Merlini Calderini (26). The plaster casts of these finds were donated to the Academy itself, but even today they are no longer available.

Summarizing, therefore, on two separate occasions during 1763 two members of the Colombarian Academy communicated to their associates that they had come into possession of two different groups of bronze laminas: the first, coming from the Faenza countryside and bought by Giovanni Baldovinetti, included six inscribed finds; the second, found in the Pistoia countryside and acquired by Francesco Ignazio Merlini Calderini, numbered only four. Of the latter there was a printed reproduction, currently dispersed, from which Bormann obtained the transcripts he reproposed in the eleventh volume of the CIL (27). As the Colombi had already remarked, three of the laminas purchased by Merlini Calderini were identical to as many in the possession of Baldovinetti. In the first place, therefore, it was the existence of several examples of these artifacts that led the publisher of the Corpus to include them in the falsae section, while acknowledging the expertise with which they were made (28).

In addition to Bormann's considerations, the vagueness of the information relating to the discovery of the two allegedly antiquated nuclei is suspected (note above all the topos of the discovery made "by a worker in making some graves on his farm"):

in this perspective, a further investigation of archival documentation could prove to be a harbinger of new information. In particular, the existence, in the State Archives of Florence, of the correspondence between Francesco Ignazio Merlini Calderini and Giuseppe Pelli Bencivenni, which includes 29 letters sent by the Pistoian abbot to the Florentine scholar during the 1763 (29). Similarly, an investigation into the relations between Giovanni Baldovinetti and his relative Margherita Baldovinetti Gambereschi, wife of Count Vincenzo Gabellotti of Faenza (30) could be profitable.

3. Laminette and more laminette

In addition to the bronze finds known through the manuscript deeds of the Accademia Colombaria, Bormann was also able to see some of them in person. Among these, a group of nine small blades was distinguished, preserved in Bologna and described as "complures tablee ariae inscriptae exemplis falsis titulorum genuinorum" (31). One of them again reported the same text engraved on the front of the artefact kept in Torcello (32):

Druso Caisari,

Ti (beri) Aug (usti) f (ilio), divi

Aug (usti) n (epoti),

s (enatus) c (onsulto).

The transcription provided by Bormann does not indicate the presence of letters on the back of the laminetta. According to the German epigraph, this find, as well as all the others belonging to the same collection nucleus, was formerly kept in the University Museum of the city of Bologna and from here it passed into the public museum (33). A comparison made at the Archaeological Civic Museum of Bologna, however, gave a negative result: it is perhaps possible that, once recognized as fake, the bronze finds were discarded from the collection or that they were lost during the last war period or after the war. immediately following (34). In addition to the eleventh volume of the CIL, the Bolognese laminetta with a dedication to Drusus Minor is also registered in the section of the Corpus relating to falsae of urban origin, with the indication "aerial table in the Bononiensi museum. […] Descripsit et damnavit Bormann »(35).

Albeit incidentally, Bormann himself also indicated that he had seen another example of the same artifact, kept "in the Arretino museum" (36). After extensive research, it was possible to identify this find at the National Archaeological Museum Gaio Cilnio Mecenate in Arezzo (Figs. 4-5) (37). The affinities with the laminetta kept in Torcello appear compelling, both in relation to the support and to the text engraved on its two sides:

Druso Caisari,

Ti (beri) Aug (usti) f (ilio), divi

Aug (usti) n (epoti),

s (enatus) c (onsulto) .//

Myself(- - -)

p (- - -) l (- - -) d (- - -) d (- - -).

Fig. 4. AREZZO, National Archaeological Museum Gaius Cilnio Mecenate, inv. 12229, recto (Photo: courtesy of the Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage of Tuscany, Florence).

Fig. 5. AREZZO, National Archaeological Museum Gaius Cilnio Mecenate, inv. 12229, verso (Photo: courtesy of the Superintendence for Archaeological Heritage of Tuscany, Florence).

Towards the middle of the upper edge the artefact is crossed by a small circular through hole, which affects the first line of the text both in the recto and in the verso, without however compromising its reading. The laminetta appears to have belonged to the Museum of the Fraternity of the laity, the main welfare congregation in Arezzo, whose collections form the founding nucleus of the current Archaeological Museum (38). A file from the Fraternity archive, drawn up by Angelo Pasqui in 1882, indicates that the find was found in Arezzo in Piazza Guido Monaco in 1865 (39). The indication, followed by a question mark, seems to be aimed at accrediting the authenticity of the artifact thanks to the expedient of an evidently fictitious discovery. Although in the immediate post-unification period the works for the construction of Piazza Guido Monaco actually resulted in numerous important archaeological discoveries (40), it is unlikely that among them there were also false finds, already attested in the Tuscan collecting circuits over a century earlier. It seems much more plausible that the laminetta preserved in Arezzo is one of those previously belonging to the members of the Accademia Colombaria, but it cannot be excluded that it is a further copy, perhaps acquired through some local antiquarian collection (41). An investigation into the Arezzo archival collections may perhaps allow us to determine more precisely the collection vicissitudes of the artefact in the future.

The presence of the inscribed bronze plates dedicated to Drusus Minor is not limited to the Italian territory alone. In recent times a specimen of the same object has been reported by Helena Gimeno Pascual (42): it is located in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional in Madrid and where it entered in 1876, together with the collection of antiquities of Don Tomás de Asensi (Figs. 6-7 ) (43). Also in this case the dimensions of the find are in all similar to those of the porcelain laminetta, just as the text that is engraved on it is analogous (44):

Druso Caisari,

Ti (beri) Aug (usti) f (ilio), divi

Aug (usti) n (epoti),

s (enatus) c (onsulto) .//

Myself(- - -)

p (- - -) l (- - -) d (- - -) d (- - -).

Fig. 6. MADRID, Museo Arqueológico Nacional, inv. 10104, recto. (Photo: Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid).

Fig. 7. MADRID, Museo Arqueológico Nacional, inv. 10104, verso. (Photo: Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid).

Tomás de Asensi, a knight of the Royal Order of Isabella the Catholic, was vice consul of Spain in Nice and commercial director for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ministerio de Estado) around the middle of the 19th century (45). It is possible that he had purchased the laminetta at the time of his residence in Nice or during the many trips he took to Italian territory. In the autograph catalog of his collection, the bronze artefact is described as follows:

Pieza n. 684 (sin fi cha). Tesera de bronce, ó sea permiso para asistir a las diversiones públicas, ó de la liberalidad, llamadas congiari, de los emperadores ú otros personajes del imperio; with inscripciones en el derecho y en el revés. The del derecho says: Druso - Caesari - Ti. - Aug. T. Divi - Aug. N. - S. C. (To Druso César, hijo de Tiberio Augusto, nieto of the divine Augustus - Senatus Consultum). La del revés says: ME - P.L.D.D. De this leyenda no es fácil la explicación. Las últimas cuatro letras pueden explicarse así: Publicus Ludus Dedit, ó sea dió juegos públicos; but no así las dos primeras letras ME, que no pudieron ser explicadas ni aún por el doctor profesor de Arquelogía Sr. Henzen, secretary of the Instituto de Correspondencia Arqueológica de Rome (46).

The entry in the catalog is distinguished by the attempt to classify the bronze sheet as an object of the Roman era, which would have been used on the occasion of games, holidays or public distributions organized by the emperors; according to its owner it would therefore fall into the category of metal artifacts known as tesserae spectaculis (47), well attested by the archaeological documentation and similar to those used for the collection of foodstuffs, which literary sources call tesserae nummariae or frumentariae (48) . The most common types of these objects, however, are made of lead and their features differ considerably from those of the laminette examined in this study. The tesserae are in fact almost always circular in shape and have the effigy of a prince or a member of the imperial domus on the front, while on the reverse their legend usually indicates the name of the magistrate in charge of setting up the shows or celebrations ( 49).

From the form drawn up by Asensi it is also clear that he had consulted Wilhelm Henzen, secretary of the Institute of Archaeological Correspondence in Rome, in an attempt to give meaning to the initials engraved on the reverse of the bronze artefact (50). In the correspondence of the German scholar, however, there is no trace of letters sent by the Spanish collector (51): it is therefore possible that Asensi had recourse to an intermediary or that, during a stay in Italy, he had contacted Henzen in person.

Henzen himself, on the other hand, got to know, albeit indirectly, another batch of finds similar to those examined so far. In fact, during a meeting of the Institute of Archaeological Correspondence held on 24 February 1860, he reported to his associates that he had received the "paper impressions of five bronze plates with letters detected, recently passed into the Basel Museum and recognized as false by mr. prof. Guglielmo Vischer, who had sent them to the Institute to find out, if this were possible, their provenance "(52). A check carried out at the Antikenmuseum in Basel made it possible to locate this nucleus of registered artifacts again (53). One of them (Figs. 8-9), as already pointed out by Henzen (54), once again reports the text of the now well-known dedication to Drusus Minor:

Druso Caisari,

Ti (beri) Aug (usti) f (ilio), divi

Aug (usti) n (epoti),

s (enatus) c (onsulto) .//

Myself(---)

p (---) l (---) d (---).

As in the case of the laminetta owned by Francesco Ignazio Merlini Calderini, the only difference between the text of the epigraph preserved in Torcello is the presence of only one D in the final line of the verso. The ways in which the Antikenmuseum of Basel acquired this find and the other four belonging to the same lot have yet to be precisely determined (55). The terminus ante quem consists precisely of the report sent by Vischer to Henzen (56).

Fig. 8. BASEL, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, Alter Bestand o. n. 26, recto. (Photo: R. Habegger).

Fig. 9. BASEL, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, Alter Bestand o. n. 26, verso. (Photo: R. Habegger).

In the aforementioned meeting of the Instituto Henzen he again reported that, in addition to the bronze artifacts preserved in Basel, others were also known, in the possession of Heinrich Schreiber, senior professor of History at the University of Freiburg in Breisgau (57). On his death, which occurred in 1872, he bequeathed his collections to the city where he had taught (58). Indeed, in a coeval handwritten inventory the presence of at least two inscribed laminas appears, one of which is undoubtedly identifiable as an example of CIL XI, 209 *, 1 (59). During the twentieth century, however, the collection was dispersed and divided between various Friborg institutions, such as the Augustinermuseum, the Prehistoric Museum (Museum für Urgeschichte, which was in turn suppressed and partially merged into the Archäologisches Museum Colombischlössle) and the City Archive (Stadtarchiv) (60). So far it has not been possible to identify the location of the flaps that belonged to Schreiber, given that they are still available.

4. Concluding remarks

The study of the bronze sheet preserved in the Provincial Museum of Torcello has brought to light an unexpected scenario. The doubts about the authenticity of the small inscribed artefact, already expressed in the past, were supported by a new autopsy examination and confirmed by the identification of numerous other laminates of similar manufacture. These findings have been unanimously judged false by epigraphic criticism, also due to the serial nature that distinguishes them. In fact, as has been found in the course of this essay, only eight or perhaps nine specimens of the small plate with a dedication to Drusus Minor are documented, of which a short summary list is provided for convenience, structured according to the order of presentation adopted in the previous pages:

1. laminetta belonging to the Provincial Museum of Torcello, apparently found in Torcello in 1908;

2. laminetta reported to a Parisian antiquarian in the nineties of the last century, of which Antonio Sartori has published the reproduction of a cast in relief in aluminum foil;

3. laminetta that belonged to Francesco Ignazio Merlini Calderini, of which he provided a printed reproduction to the colombari members in September 1763;

4. laminetta that belonged to Giovanni Baldovinetti, of whom he provided a plaster cast to the Colombarian Academy in April 1763;

5. laminetta reported by Eugen Bormann at the Archaeological Civic Museum of Bologna and formerly belonging to the University Museum of the same city;

6. laminetta kept at the National Archaeological Museum Gaio Cilnio Mecenate of Arezzo, already reported by Eugen Bormann and apparently found in Arezzo in 1865;

7. laminetta preserved in the Museo Arqueológico Nacional in Madrid, from which it was acquired in 1876 together with the collection of Don Tomás de Asensi;

8. flap kept at the Antikenmuseum in Basel, already reported by Wilhelm Vischer in February 1860;

9. flap owned by Heinrich Schreiber in Friborg, reported by Vischer himself in February 1860 (it is not certain, however, that it bore the same text engraved on the Torcello flap).

At the current state of research, only four of these laminas can be located with certainty: these are those preserved in the museums of Torcello, Arezzo, Madrid and Basel, of which photographic reproductions have been provided approx. It is possible that other specimens will be identified in the future, just as it is not excluded that some of those listed here actually correspond to the same find, which would be documented in different phases of its collecting history (61).

From this point of view, the results of the research conducted so far can only be considered partial. It remains to be determined, first of all, the identity of the character who produced the series of laminette, as well as the time and place in which he acted. With regard to this latter aspect, it seems plausible to attribute the genesis of the bronze finds to the Tuscan context and not to the Roman one, as instead implicitly suggested by the inclusion of the Bolognese specimen in the sixth volume of the CIL dedicated to the inscriptiones falsae ( 62). The presence of the first laminates known to us in the collections of the members of the Colombarian Academy shortly after the mid-eighteenth century suggests that their creation is due to a forger active at that time in the Medici city (63).

Also with regard to the aims of the creation of the flaps there are many points that remain to be clarified. Lately, the topic of epigraphic falsification has been dealt with several times by sector bibliographies, which not only examined numerous specific cases, but also focused on the various reasons underlying this phenomenon (64). In this regard, in a very recent contribution, Alfredo Buonopane has convincingly proposed to recognize the existence of three distinct categories: that of forgeries in the strict sense (i.e. of deliberately counterfeited inscriptions and for malicious purposes), that of copies and that of reworkings or pastiches (65). In our specific case, however, the intentions of the counterfeiter are not yet determinable with precision: if on the one hand the initial conviction that the flails flaunted by the colombari partners were authentic would lead to the presumption of the existence of a fraud devised against them (or with their involvement). possible trade, not antiques, but collectibles or tourism end of the eighteenth century "(66). In any case, the recognition of the non-authenticity of the laminetta kept in Torcello necessarily leads to reject the news of its alleged discovery near the cathedral of the island and to seek new information on its acquisition by the Provincial Museum.

In the future, therefore, a number of questions will have to be addressed which still remain unanswered. Specifically, it will be necessary to try to understand: whether all the foils attested together with those with a dedication to Drusus Minor are the result of a conscious counterfeiting; whether their mass production dates back to the same period or can be ascribed to different circumstances and locations; whether or not their various owners were aware of owning fake items; whether the epigraphic texts usually engraved on the recto of small bronze artifacts more or less faithfully reflect the content of authentic inscriptions and whether the initials on the reverse have a specific meaning that has not been deciphered up to now; whether other ancient sources can also be included among the models of inspiration, such as legends of coins or literary testimonies.

In relation to the single exhibit to which this essay is dedicated, the opinion of the editors of the sixth volume of the CIL is noted, according to which the text of the laminetta would have been reproduced starting from the central lines of a genuine honorary plate of the Tiberian era, found in Rome in 1665 and now kept in Palazzo del Drago in Via delle Quattro Fontane (67). The epigraph was actually already well known in the eighteenth century, as it was included in the printed syllogs of Spon and Fabretti, published respectively in 1685 and 1702 (68). Another written document that could have served as a model for the text engraved on the recto of the small bronze artifact is a dedication to Drusus Minor from Segobriga in Hispania Tarraconensis (69), already published in Gruter's Corpus absolutissimum, printed in Heidelberg at the beginning of the seventeenth century (70). This last collection enjoyed, as is well known, a very wide circulation in the following centuries and also served in other cases as a repertoire of archetypes which, for the most varied reasons, were then copied onto a stone support (71). Finally, it cannot be excluded that the flap was exemplified starting from the legends of some coins of the Tiberian or Fl avian era, which are distinguished not only by the same title attributed to the son of Tiberius, but also by the explicit dedication on a resolution of the Senate (an aspect that is absent in the epigraphic testimonies) (72). These coins were widely known in the eighteenth century, as evidenced by their presence in the main numismatic repertoires of the time (73). An examination of the archival documentation certifies, for example, that some specimens were also owned by the first members of the Accademia Colombaria (74).

In the face of a still very wide range of possibilities, the research work must temporarily stop. Only an investigation extended to all the other bronze inscribed plates reported from time to time together with the one with a dedication to Drusus Minor can perhaps provide a definitive clarification on the events relating to the creation and dissemination of these artifacts, which appear repeatedly in the volumes of the CIL and which often lie, as we have seen, hidden or set aside in various Italian and European museums. In other words, as Henzen already warned in 1860, of these finds, hitherto substantially neglected, "it would be important to bring together all the specimens known to exist, with exact information on their provenance" (75). This proposal certainly deserves to be the subject of future in-depth study.